Abstract

Dracorhodin can be isolated from the exudates of the fruit of Daemonorops draco. Previous studies suggested that dracorhodin perchlorate can promote fibroblast proliferation and enhance angiogenesis during wound healing. In the present study, the potential bioactivity of dracorhodin perchlorate in human HaCaT keratinocytes, were investigated in vitro, with specific focus on HaCaT wound healing. The results of in vitro scratch assay demonstrated the progressive closure of the wound after treatment with dracorhodin perchlorate in a time-dependent manner. An MTT assay and propidium iodide exclusion detected using flow cytometry were used to detect cell viability of HaCaT cells. Potential signaling pathways underlying the effects mediated by dracorhodin perchlorate in HaCaT cells were clarified by western blot analysis and kinase activity assays. Dracorhodin perchlorate significantly increased the protein expression levels of β-catenin and activation of AKT, ERK and p38 in HaCaT cells. In addition, dracorhodin perchlorate did not induce HaCaT cell proliferation but promoted cell migration. Other mechanisms may yet be involved in the dracorhodin perchlorate-induced wound healing process of human keratinocytes. In summary, dracorhodin perchlorate may serve to be a potential molecularly-targeted phytochemical that can improve skin wound healing.

Keywords: dracorhodin perchlorate. β-catenin, ERK/p38/AKT signaling, HaCaT keratinocytes, wound healing

Introduction

Dragon blood is a type of deep-red resin that has been used as a form of traditional medicine worldwide since ancient times (1). Families of plants with the ability to produce dragon blood can be classified into four different categories: Asparagaceae, Arecaceae, Chamaesyce and Fabaceae (Table I) (2-4). The earliest record of dragon blood being used for medicine was performed using the plant genus Dracaena in Socotra Island in Yemen (5). Due to being situated in ideal location and the rapid growth rate of the palm tree species Daemonorops draco, dragon blood extracted from this tree became the mainstream product in the traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) market after the Ming Dynasty in China (6). Therefore, red resin from Daemonorops draco is recognized as authentic dragon blood in the official documents of China, Hong Kong and Taiwan (7-9). In particular, dracorhodin has become the reference standard of dragon blood from the palm tree D. draco (10), where the content of dracorhodin in dragon blood for medical use is recommended to be >1% (9).

Table I.

Plant species that contain dragon blood and their respective geographical origins (4).

| Plant family | Plant species | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Asparagaceae | Dracaena cinnabari | Socotra Island, Yemen |

| Dracaena draco | Canary Islands, Spain | |

| Dracaena cochinchinensis | Yunnan Province, China | |

| Arecaceae | Daemonorops draco | Indonesia and Malaysia |

| Chamaesyce | Croton salutaris | |

| C. lechleri | Amazon basin | |

| C. draconoides | ||

| Fabaceae | Pterocarpus draco | India |

| P. marsupium |

Dragon blood has been included in recipes for wound treatment in various ancient traditional Chinese medical guides of the 14-18th century (6). Accumulating evidence has also indicated that dragon blood possesses wound healing activities both in vivo and in vitro (1,11-13). Accordingly, a previous study showed that the herbal complex ‘Jinchuang Ointment’ can successfully treat non-healing wounds on patients with diabetes, where dragon blood from D. draco is one of the components (2.1%) in this ointment (14).

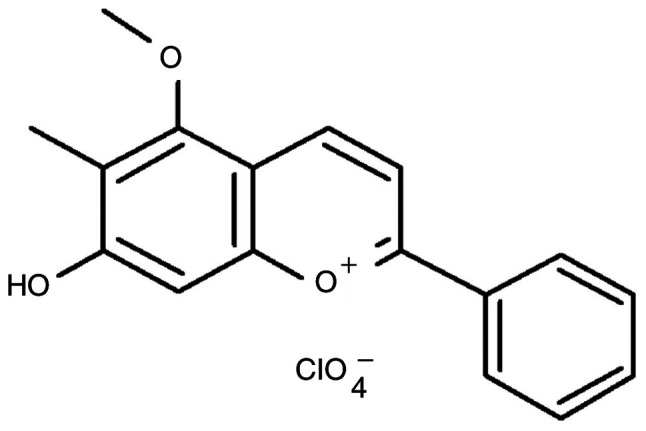

Dracorhodin perchlorate is a synthetic chemical analog of dracorhodin (Fig. 1) (10,15-18) that has been shown to exhibit angiogenic activity on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (10,19). Recently, both dracorhodin perchlorate and methanol extracts of crude dragon blood have demonstrated in vivo pro-angiogenic activity in zebrafish embryos (10). Additionally, previous studies have revealed bioactivities of dracorhodin perchlorate in human cancer cells, where it can induce apoptotic cell death in different types of cancer cells, including U87MG and T98G glioma cells (20), SK-MES-1 human lung squamous carcinoma cells (21), MCF-7 human breast cancer cells (22), SGC-7901 human gastric tumor cells (23), PC-3 human prostate cancer cells (18), HL-60 leukemia cells (16), A375-S2 human melanoma cells (24) and HeLa human cervical cancer cells (15,25). Furthermore, dracorhodin perchlorate was reported to promote NIH-3T3 fibroblast cell proliferation in vitro and induce rat wound healing in vivo (26). Dracorhodin perchlorate has also been shown to accelerate skin wound healing in Wistar rats in vivo (27). However, the effects of dracorhodin perchlorate on wound healing in human HaCaT keratinocytes remain poorly understood. Therefore, in the present study the underlying mechanism of the wounding healing regulation and associated signaling pathways mediated by dracorhodin perchlorate in HaCaT keratinocytes was investigated in vitro.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of dracorhodin perchlorate.

Materials and methods

Reagents and chemicals

DMEM, FBS, penicillin/streptomycin and L-glutamine were purchased from HyClone, Cytiva. All primary antibodies and anti-mouse/-rabbit immunoglobulin IgG HRP-linked secondary antibodies were procured from GeneTex International Corporation. Reagent grade DMSO, thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT), PBS, propidium iodide (PI), wortmannin (an AKT inhibitor), U0126 (an ERK inhibitor) and SB203580 (a p38 inhibitor), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA unless otherwise specified. Dracorhodin perchlorate (batch no. 110811-201506; purity, 98.6%) was purchased from the National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products (Beijing, China), which was dissolved in DMSO and stored at -20˚C freezer before use. The vehicle control was kept below 0.1% DMSO in culture medium.

Cell culture

Human skin HaCaT keratinocytes were obtained from CLS Cell Lines Service GmbH and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine in a humidified atmosphere at 37˚C in 5% CO2/95% air as previously described (28,29). HaCaT cells were cultured until passage 40 (20 weeks) and did not exceed 40 generations.

Dynamic cell migration assay

HaCaT cells (1x104 cells/well) were seeded into a 96-well plate overnight before the wound area (700-800-µm wide) was created using Incucyte 96-Well Woundmaker Tool (cat. no. 4563; Essen BioScience). The scratched cells were then exposed to 0, 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate in serum-free DMEM (HyClone; Cytiva). The cell migration experiment was conducted over 24 h with data collection every 3 h at 37˚C. The cell images and wound width were monitored using the IncuCyte ZOOM System instrument by light microscopy (magnification, x100) [(Incucyte S3 Live-Cell Analysis System and Incucyte Scratch Wound Analysis Software Module (cat. no. 9600-0012; Essen BioScience)] as previously described (30,31).

Cell viability assay

HaCaT cells (2.5x105 cells/well) were plated into 24-well plates and treated with or without 0.5, 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate for 24 h at 37˚C. Cell viability was determined using MTT assay as previously described (32-34). In brief, MTT solution (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well for 2 h at 37˚C before the blue formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO (500 µl/well) by constant shaking for 10 min. The absorbance of each well was measured using an ELISA plate reader at a test wavelength of 570 nm with a reference wavelength of 620 nm.

For the PI exclusion assay, 2.5x105 cells/well were harvested and plated into 24-well plates and resuspended in 500 µl of 5 µg/ml PI for 5 min at 4˚C. The numbers of viable cells and dead cells were determined using a BD FACSCalibur™ Flow Cytometry System and BD CellQuest Pro Software version 6.0 (both BD Biosciences), where the PI dye solution was applied to specifically stain dead cells. Cell viability was calculated as follows: % Cell viability = (PIem of test)/(PIem of control) x100%. Where, PIem = gated cells of PI fluorescence emission (<102 fluorescence).

Western blot analysis

HaCaT cells (5x106 cells per 75T flask) were incubated with or without 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate for 12 h at 37˚C. Cell samples were lysed in Trident RIPA Lysis Buffer (GeneTex International Corporation) and collected as previously described (35,36). Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of the protein sample (40 µg) were prepared, and 10-12% SDS-PAGE was performed. Proteins were transferred onto an Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membrane prior to blocking with Trident Universal Protein Blocking Reagent (GeneTex International Corporation) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was subsequently incubated with primary antibodies against β-catenin (cat. no. GTX101435), phosphorylated (p)-AKT (Ser473) (cat. no. GTX28932), AKT (cat. no. GTX121937), p-ERK (cat. no. GTX59568), ERK (cat. no. GTX59618), p38 (cat. no. GTX110720), p-p38 (cat. no. GTX48614) and β-actin (cat. no. GTX109639) at a dilution of 1:1,000 at 4˚C overnight. The membranes were then incubated with the appropriate anti-mouse (cat. no. GTX213111-01) and anti-rabbit (cat. no. GTX213110-01) IgG HRP-linked secondary antibodies at a dilution of 1:10,000 for 1 h at room temperature. Blot visualization was performed using the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Merck KGaA) and all bands of immunoblots were normalized to the densitometric value of β-actin. These experiments were conducted in duplicate. The bands were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software version 1.41 (National Institutes of Health) as previously described (33,37-39).

Sandwich ELISA assay for p-protein kinases

HaCaT cells (5x106 cells per T75 flask) were treated with or without 0.5, 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate for 12 h at 37˚C. The cells were harvested and total proteins were collected using Trident RIPA Lysis Buffer (GeneTex International Corporation). The samples were incubated in microwells coated with the appropriate antibody for 2 h at 37˚C (for p-ERK) or overnight at 4˚C (for p-Akt) according to the manufacturer's protocols of the PathScan Sandwich ELISA kits [p-Akt (Thr308; cat. no. 7252C) and p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204; cat. no. 7177C); Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.]. The secondary antibodies and the reagents used for the chemical reactions were provided in these kits. Absorbance was measured using an ELISA reader (Anthos 2001; Anthos Labtec Instruments GmbH) at a wavelength of 450 nm, as previously described (38-40).

Wound healing assay

HaCaT cells were placed in a six-well tissue culture plates for 24 h at 37˚C and cultured to 90% confluence. Individual wells were then scratched with a 200-µl micropipette tip to create a denuded zone of constant width (1 mm). Cells were then cultured in serum-free DMEM (HyClone; Cytiva) and incubated with or without dracorhodin perchlorate (1 µg/ml) or with specific protein kinase inhibitors [10 µM wortmannin (AKT inhibitor), 10 µM U0126 (ERK inhibitor) or 10 µM SB203580 (p38 inhibitor)] and 0.1% DMSO as a control for 24 h at 37˚C. To determine cell migration, cell images were captured after 24 h treatment under phase-contrast microscopy (magnification, x100; Leica DMIL microscope; type 090-135.001; Leica Microsystems GmbH), as previously described (38). Image analysis was performed by using AxioVision LE64 software (version 4.9.1.0; Carl Zeiss AG). The ability of cell migration was calculated as follows: Cell migration (% of control) = [Gw (0 h) of test-Gw (24 h) of test]/[Gw (0 h) of control-Gw (24 h) of control] x100%. Where, Gw (0 h) = gap width at 0 h, and Gw (24 h) = gap width at 24 h.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (three experimental repeats per assay). Differences among groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's or Dunnett's post hoc test with SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc.). P<0.05 or P<0.001 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

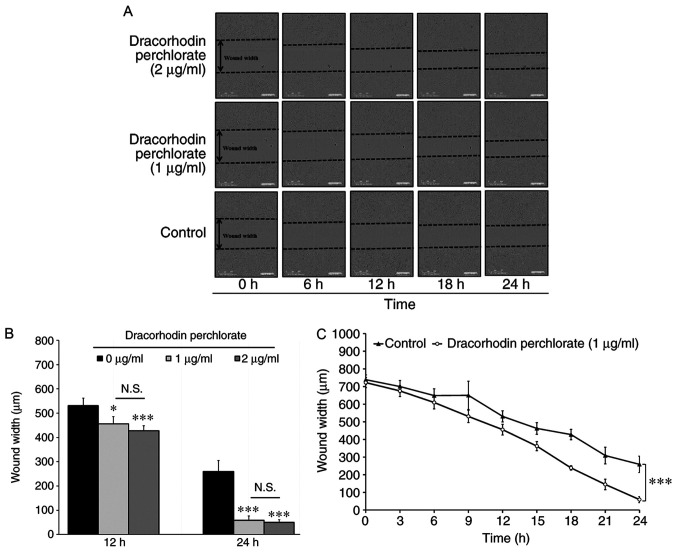

Dracorhodin perchlorate promotes cell migration in HaCaT keratinocytes

Wound healing activity was first investigated, which mimics the migration of keratinocytes toward wound margins in vitro. As shown in Fig. 2A, the wound was closing progressively following treatment with dracorhodin perchlorate in HaCaT cells. No significant difference was found between 1 and 2 µg/ml groups. Therefore, the optimal dracorhodin perchlorate concentration to monitor wound healing activity was found to be 1 µg/ml (Fig. 2B). Quantitative data indicated that dracorhodin perchlorate at 1 µg/ml significantly reduced the wound width at the time point of 24 h and markedly promoted HaCaT cell migration compared with those in control cells (Fig. 2C). Therefore, this suggests that dracorhodin perchlorate enhanced cell migration in HaCaT keratinocytes.

Figure 2.

Determination of cell migration in HaCaT keratinocytes. (A) Effects of dracorhodin perchlorate on wound healing of HaCaT keratinocytes. Cells (1x104 cells/well) in 96-well plates were scratched and incubated with or without 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate for indicated time. (B) Cells (1x104 cells/well) in a 96-well plate were scratched and treated with or without 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate for 12 and 24 h. The wound width of HaCaT keratinocytes was determined using the IncuCyte ZOOM System instrument and then quantified. (C) Time courses of the relative wound widths of HaCaT keratinocytes after wound generation. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, n=3. Tukey's post hoc test after ANOVA. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs. 0 µg/ml untreated control. N.S., not significant.

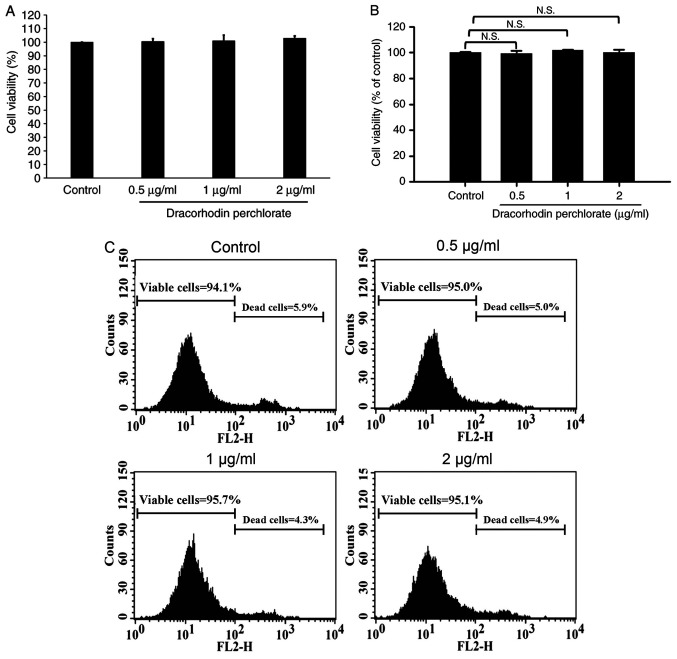

Dracorhodin perchlorate does not enhance cell viability in HaCaT keratinocytes

As previously reported, the cell viability of human primary fibroblast proliferation significantly increased by dracorhodin perchlorate treatment (41). Therefore, MTT assay and PI exclusion method were performed to investigate the cell viability and cytotoxicity of HaCaT keratinocytes after dracorhodin perchlorate exposure. Dracorhodin perchlorate did not affect the viability of HaCaT cells at the highest concentration tested in this study, which was 2 µg/ml (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B and C, viable cells were generally excluded from PI because of low emission fluorescence. No significant change was observed in dracorhodin perchlorate-treated HaCaT keratinocytes (Fig. 3B). Moreover, flow cytometry results showed that the total counts of dead and viable cells were <10 and >90%, respectively (Fig. 3C). Thus, the migration ability of HaCaT cells caused by dracorhodin perchlorate was not due to the cell viability of HaCaT keratinocytes.

Figure 3.

Effects of dracorhodin perchlorate on cell viability in HaCaT keratinocytes. Cells (2.5x105 cells/well) in 24-well plates were incubated with 0, 0.5, 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate for 24 h. The cell viability was determined by (A) MTT assay, (B) propidium iodide exclusion method, and (C) a representative histogram of the quantified flow cytometry plots. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, n=3. Dunnett's post hoc test after ANOVA. N.S., not significant.

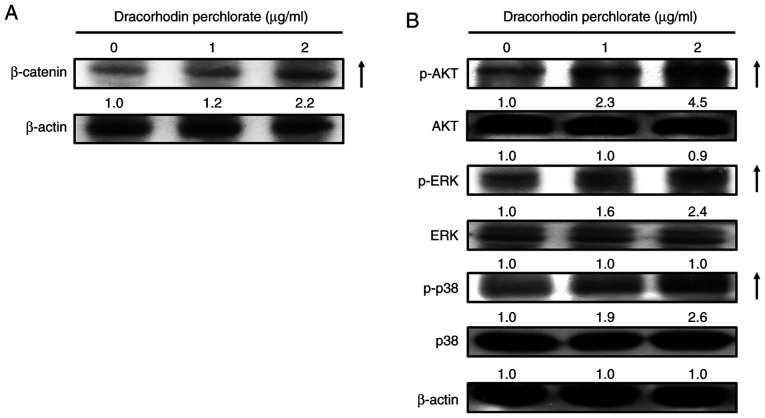

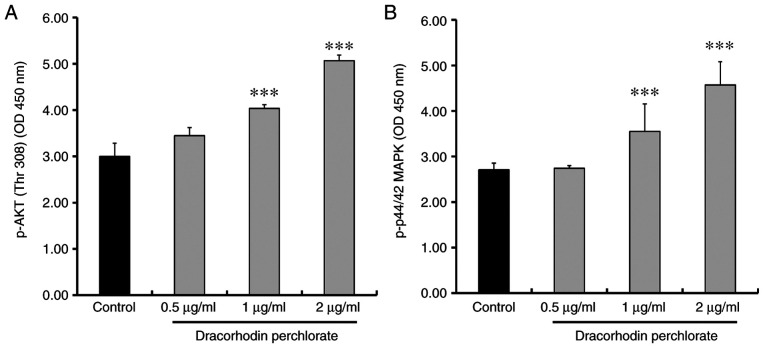

Dracorhodin perchlorate increases the protein expression of β-catenin and phosphorylation of Akt, p38 and ERK in HaCaT keratinocytes

Previous studies have suggested that wound healing is closely associated with β-catenin signaling (42,43), where keratinocyte mobility can be stimulated through the MAPK and AKT signaling pathways (44-46). Western blotting experiments were therefore performed to investigate the effects of dracorhodin perchlorate treatment on the protein expression of β-catenin and both phosphorylation of ERK and AKT. Dracorhodin perchlorate treatment (2 µg/ml for 12 h) markedly upregulated the protein levels of β-catenin, phosphorylated ERK, phosphorylated Akt and phosphorylated p38 in HaCaT keratinocytes compared with those in control cells (Fig. 4). This was subsequently verified using sandwich ELISA. The levels of both phosphorylated AKT and ERK significantly increased after dracorhodin perchlorate treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Effects of dracorhodin perchlorate on the protein expression levels of β-catenin, AKT, ERK and p38 proteins in HaCaT keratinocytes. Cells were incubated with 0, 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate for 12 h. Whole cell lysates were prepared before the levels of cell migration-related proteins were analyzed by western blot analysis. The protein levels of (A) β-catenin, (B) p-AKT, AKT, p-ERK, ERK, p-p38 and p38 were detected. All blots were normalized to β-actin to ensure equal loading.

Figure 5.

Effects of dracorhodin perchlorate on the AKT and ERK kinase activities in HaCaT keratinocytes. Cells were incubated with 0, 0.5, 1 and 2 µg/ml dracorhodin perchlorate for 12 h. Whole cell lysates were then prepared and the (A) AKT and (B) ERK kinase activities were analyzed by sandwich p-AKT and p-ERK ELISA. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, n=3. Dunnett's post hoc test after ANOVA. ***P<0.001 vs. Control. OD, optical density.

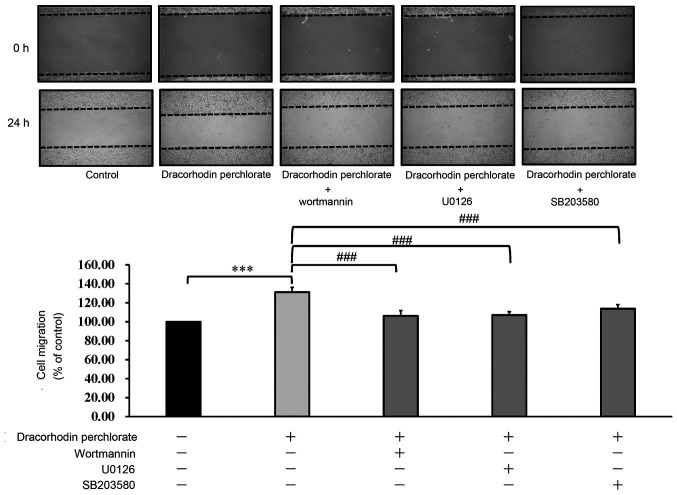

To confirm further that the mechanism of wound healing underlying the effects of dracorhodin perchlorate, wortmannin, U0126 and SB203580, inhibitors of AKT, ERK and p38 MAPK, respectively, were used. As shown in Fig. 6, inhibitors of AKT, ERK and p38 MAPK could all significantly inhibit the migration of dracorhodin perchlorate-treated keratocytes. Therefore, it could be concluded that dracorhodin perchlorate activated wound healing by upregulating the ERK, MAPK and AKT signaling pathways in human HaCaT keratinocytes in vitro.

Figure 6.

Effect of protein kinase inhibitors on the cell migration of dracorhodin perchlorate-treated keratinocytes. Cells were incubated with or without dracorhodin perchlorate (1 µg/ml) and three protein kinase inhibitors for 24 h. Wortmannin (10 µM), U0126 (10 µM) and SB203580 (10 µM) are AKT, ERK, and p38 inhibitors, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, n=3. Tukey's post hoc test after ANOVA. ***P<0.001 and ###P<0.001.

Discussion

Dracorhodin perchlorate is a new synthetic chemical analog of dracorhodin (10,15-18). Dracorhodin is originally the fruit extract of dragon blood, which can be used as a TCM (2,10). Dragon blood confers a number of bioactivities, including antibacterial, anti-diarrheal, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, antitumor, anti-ulcer, antiviral, immune-modulatory and wound healing functions (1). Previous studies have demonstrated that dragon blood can promote the proliferation of fibroblasts, increase the ratio of cells in the S-phase of the cell cycle and collagen formation, in addition to enhancing wound healing (1,11,12). In the present study, dracorhodin perchlorate was found to significantly promote wound healing in human HaCaT keratinocytes. However treatment with dracorhodin perchlorate (0.5-2 µg/ml) in HaCaT keratinocytes exerted no statistically significant effects on keratinocyte viability. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first time an in vitro scratch assay was utilized using dynamic analysis facilitated by the IncuCyte Kinetic Live Cell Imaging System to evaluate the effects on wound closure in dracorhodin perchlorate-treated HaCaT cells. Furthermore, visible gaps were observed in the monolayer of cells at the start of the assay. In accordance with this result, the cell number did not increase.

Previous studies have shown that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway serves an important role in the wound healing process of human keratinocytes (47). During the wound healing of keratinocytes, cell migration and invasion are regulated by the activation of the PI3K/AKT, ERK, p38/MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascades (48-51). Additionally, activation of the ERK and p38/MAPK pathways in cell migration is crucial for wound healing (52,53). In accordance with these previous findings aforementioned, results from the present study showed that dracorhodin perchlorate treatment markedly increased the phosphorylation of AKT, ERK and p38 and kinase activities in HaCaT cells. In addition, dracorhodin perchlorate-treated HaCaT cells were selectively incubated with the AKT inhibitor wortmannin, the ERK inhibitor U0126 or the p38 inhibitor SB203580 for 24 h. Cell migration was found to be inhibited by all three inhibitors, suggesting that the ERK, p38 MAPK and AKT signaling pathways were all involved. All these results indicated that AKT, ERK and p38 MAPK were activated by dracorhodin perchlorate treatment during the wound healing process in HaCaT cells in a dose-dependent manner within the concentration range of 0 and 2 µg/ml. However, the optimal dracorhodin perchlorate concentration for wound healing activity was found in the present study to be 1 µg/ml rather than 2 µg/ml. Therefore, other mechanisms may be involved in this dracorhodin perchlorate-induced wound healing process in HaCaT cells.

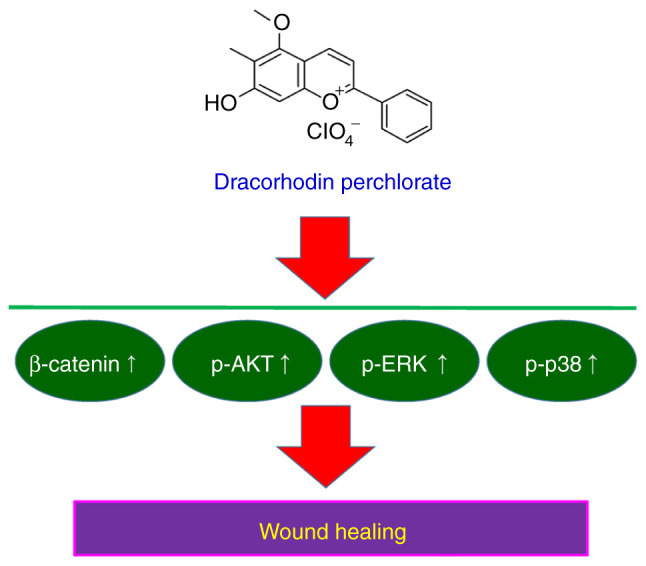

A proposed summary of the wound healing mechanism underlying the effects mediated by dracorhodin perchlorate in HaCaT cells is shown in Fig. 7. It was found that dracorhodin perchlorate promoted the wound healing activity of HaCaT keratinocytes through the β-catenin, ERK, p38 MAPK and AKT signaling pathways. These findings provide novel insights into the mechanistic information in the wound healing activity of dracorhodin perchlorate in human HaCaT keratinocytes.

Figure 7.

Summary of the possible mechanism underlying the wound healing of dracorhodin perchlorate in HaCaT keratinocytes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of Mr. Meng-Jou Liao and Mr. Chin-Chen Lin (Tekon Scientific Corporation, Taipei, Taiwan) for their assistance and equipment support on this study. The authors would also like to thank Mr. Chang-Wei Li (AllBio Science, Inc., Taichung, Taiwan) for his excellent technical support.

Funding Statement

Funding: Financial support was provided by the China Medical University Hospital (grant no. DMR-106-179) and the China Medical University Beigang Hospital (grant no. CMUBH R106-005).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: TJH and HPC. Cell migration, cell viability, western blotting and protein kinase activity: CCL, JSY and YJC. Protein kinase inhibition: CCL and YNJ. Wound healing assay and acquisition of data: YMH, MCY and FJT. Statistical analysis of all data and interpretation of results: FJT, TJH and HPC. CCL and HPC confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Pona A, Cline A, Kolli SS, Taylor SL, Feldman SR. Review of future insights of Dragon's Blood in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(e12786) doi: 10.1111/dth.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sousa MM, Melo MJ, Parola AJ, Seixas de Melo JS, Catarino F, Pina F, Cook FE, Simmonds MS, Lopes JA. Flavylium chromophores as species markers for dragon's blood resins from Dracaena and Daemonorops trees. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1209:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards HG, de Oliveira LF, Prendergast HD. Raman spectroscopic analysis of dragon's blood resins-basis for distinguishing between Dracaena (Convallariaceae), Daemonorops (Palmae) and Croton (Euphorbiaceae) Analyst. 2004;129:134–138. doi: 10.1039/b311072a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu C, Cai XQ, Chang Y, Chen CH, Ho TJ, Lai SC, Chen HP. Rapid identification of dragon blood samples from Daemonorops draco, Dracaena cinnabari and Dracaena cochinchinensis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Phytochem Anal. 2019;30:720–726. doi: 10.1002/pca.2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Okaishi A. Exploring the historical distribution of Dracaena cinnabari using ethnobotanical knowledge on Socotra Island, Yemen. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2021;17(22) doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu KC. Quality evaluation of herbal medicine Ercha, Xuejie, Ruxiang and Moyao. Master Thesis, China Medical University, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica strandards. The People's Republic of China: Department of Health, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 362-368, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8. State Pharmacopoeia Commission of the PRC: Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. 1 Beijing, People's Medical Publishing House, p142, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taiwan Herbal Pharmacopeia Editorial Panel Committee. Taiwan Herbal Pharmacopeia, version 2. Taipei: Ministry of Health and Welfare, Executive Yuan, pp102-103, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnaraj P, Chang Y, Ho TJ, Lu NC, Lin MD, Chen HP. In vivo pro-angiogenic effects of dracorhodin perchlorate in zebrafish embryos: A novel bioactivity evaluation platform for commercial dragon blood samples. J Food Drug Anal. 2019;27:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Namjoyan F, Kiashi F, Moosavi ZB, Saffari F, Makhmalzadeh BS. Efficacy of Dragon's blood cream on wound healing: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Tradit Complement Med. 2016;6:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li D, Hui R, Hu Y, Han Y, Guo S. Effects of extracts of Dragon's blood on fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix hyaluronic acid. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;31:53–57. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xin N, Yang FJ, Li Y, Li YJ, Dai RJ, Meng WW, Chen Y, Deng YL. Dragon's blood dropping pills have protective effects on focal cerebral ischemia Rats model. Phytomedicine. 2013;21:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho TJ, Jiang SJ, Lin GH, Li TS, Yiin LM, Yang JS, Hsieh MC, Wu CC, Lin JG, Chen HP. The in vitro and in vivo Wound Healing Properties of the Chinese Herbal medicine ‘Jinchuang Ointment’. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016(1654056) doi: 10.1155/2016/1654056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia M, Wang D, Wang M, Tashiro S, Onodera S, Minami M, Ikejima T. Dracorhodin perchlorate induces apoptosis via activation of caspases and generation of reactive oxygen species. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:273–283. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj03102x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia MY, Wang MW, Cui Z, Tashiro SI, Onodera S, Minami M, Ikejima T. Dracorhodin perchlorate induces apoptosis in HL-60 cells. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2006;8:335–343. doi: 10.1080/10286020500035300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Wang Q, Liu J, Zhang L, Zhang B. Dracorhodin perchlorate inhibit high glucose-induced connective tissue growth factor formation in human mesangial cells. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2009;34:896–899. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Y, Ju W, Hao H, Liu Q, Lv L, Zeng F. Dracorhodin perchlorate suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cell line PC-3. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2011;31(215) doi: 10.1007/s11596-011-0255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li F, Jiang T, Liu W, Hu Q, Yin H. The angiogenic effect of dracorhodin perchlorate on human umbilical vein endothelial cells and its potential mechanism of action. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:1667–1672. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Luo J, Meng L, Pan T, Zhao B, Tang ZG, Dai Y. Dracorhodin perchlorate induces the apoptosis of glioma cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:2364–2372. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang G, Sun M, Zhang Y, Hua P, Li X, Cui R, Zhang X. Dracorhodin perchlorate induces G1/G0 phase arrest and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in SK-MES-1 human lung squamous carcinoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:240–246. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu JH, Zheng GB, Liu CY, Zhang LY, Gao HM, Zhang YH, Dai CY, Huang L, Meng XY, Zhang WY, Yu XF. Dracorhodin perchlorate induced human breast cancer MCF-7 apoptosis through mitochondrial pathways. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:1149–1156. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasul A, Ding C, Li X, Khan M, Yi F, Ali M, Ma T. Dracorhodin perchlorate inhibits PI3K/Akt and NF-κB activation, up-regulates the expression of p53, and enhances apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2012;17:1104–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0742-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia M, Wang M, Tashiro S, Onodera S, Minami M, Ikejima T. Dracorhodin perchlorate induces A375-S2 cell apoptosis via accumulation of p53 and activation of caspases. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:226–232. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia MY, Wang MW, Wang HR, Tashiro S, Ikejima T. Mechanism of dracorhodin perchlorate-induced Hela cell apoptosis. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2004;39:966–970. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang X, Liu L, Qiao L, Zhang B, Wang X, Han Y, Yu W. Dracorhodin perchlorate regulates fibroblast proliferation to promote rat's wound healing. J Pharmacol Sci. 2018;136:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang XW, Qiao L, Liu L, Zhang BQ, Wang XW, Han YW, Yu WH. Dracorhodin Perchlorate Accelerates Cutaneous Wound Healing in Wistar Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017(8950516) doi: 10.1155/2017/8950516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boukamp P, Petrussevska RT, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig NE. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:761–771. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia Q, Chiang HM, Yin JJ, Chen S, Cai L, Yu H, Fu PP. UVA photoirradiation of benzo[a]pyrene metabolites: Induction of cytotoxicity, reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation. Toxicol Ind Health. 2015;31:898–910. doi: 10.1177/0748233713484648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelles JD, Chipuk JE. Robust high-throughput kinetic analysis of apoptosis with real-time high-content live-cell imaging. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(e2493) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee MR, Lin C, Lu CC, Kuo SC, Tsao JW, Juan YN, Chiu HY, Lee FY, Yang JS, Tsai FJ. YC-1 induces G0/G1 phase arrest and mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant human oral cancer CAR cells. Biomedicine (Taipei) 2017;7(12) doi: 10.1051/bmdcn/2017070205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan CH, Horng CT, Lee CF, Chiang NN, Tsai FJ, Lu CC, Chiang JH, Hsu YM, Yang JS, Chen FA. Epigallocatechin gallate sensitizes cisplatin-resistant oral cancer CAR cell apoptosis and autophagy through stimulating AKT/STAT3 pathway and suppressing multidrug resistance 1 signaling. Environ Toxicol. 2017;32:845–855. doi: 10.1002/tox.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang HP, Lu CC, Chiang JH, Tsai FJ, Juan YN, Tsao JW, Chiu HY, Yang JS. Pterostilbene modulates the suppression of multidrug resistance protein 1 and triggers autophagic and apoptotic mechanisms in cisplatin-resistant human oral cancer CAR cells via AKT signaling. Int J Oncol. 2018;52:1504–1514. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee HP, Chen PC, Wang SW, Fong YC, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ, Chung JG, Huang CY, Yang JS, Hsu YM, et al. Plumbagin suppresses endothelial progenitor cell-related angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J Funct Foods. 2019;52:537–544. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiang JH, Yang JS, Lu CC, Hour MJ, Chang SJ, Lee TH, Chung JG. Newly synthesized quinazolinone HMJ-38 suppresses angiogenetic responses and triggers human umbilical vein endothelial cell apoptosis through p53-modulated Fas/death receptor signaling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;269:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma YS, Weng SW, Lin MW, Lu CC, Chiang JH, Yang JS, Lai KC, Lin JP, Tang NY, Lin JG, Chung JG. Antitumor effects of emodin on LS1034 human colon cancer cells in vitro and in vivo: Roles of apoptotic cell death and LS1034 tumor xenografts model. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai YF, Chen YF, Hsiao CY, Huang CW, Lu CC, Tsai SC, Yang JS. Caspase dependent apoptotic death by gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) via reactive oxygen species production and MAPK signaling in rat C6 glioma cells. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:1324–1332. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu YJ, Hour MJ, Jin YA, Lu CC, Tsai FJ, Chen TL, Ma H, Juan YN, Yang JS. Disruption of IGF-1R signaling by a novel quinazoline derivative, HMJ-30, inhibits invasiveness and reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in osteosarcoma U-2 OS cells. Int J Oncol. 2018;52:1465–1478. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu CC, Chiang JH, Tsai FJ, Hsu YM, Juan YN, Yang JS, Chiu HY. Metformin triggers the intrinsic apoptotic response in human AGS gastric adenocarcinoma cells by activating AMPK and suppressing mTOR/AKT signaling. Int J Oncol. 2019;54:1271–1281. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han J, Lee JD, Bibbs L, Ulevitch RJ. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265:808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang P, Li J, Tang X, Zhang J, Liang J, Zeng G. Dracorhodin perchlorate induces apoptosis in primary fibroblasts from human skin hypertrophic scars via participation of caspase-3. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;728:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowley E, O'Gorman DB, Gan BS. Beta-catenin signaling in fibroproliferative disease. J Surg Res. 2007;138:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindley LE, Stojadinovic O, Pastar I, Tomic-Canic M. Biology and biomarkers for wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138 (Suppl 3):S18–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira Beserra F, Xue M, Maia GLA, Leite Rozza A, Helena Pellizzon C, Jackson CJ. Lupeol, a Pentacyclic Triterpene, promotes migration, wound closure, and contractile effect in vitro: Possible involvement of PI3K/Akt and p38/ERK/MAPK Pathways. Molecules. 2018;23(2819) doi: 10.3390/molecules23112819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patruno A, Pesce M, Grilli A, Speranza L, Franceschelli S, De Lutiis MA, Vianale G, Costantini E, Amerio P, Muraro R, et al. mTOR activation by PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling in short ELF-EMF exposed human keratinocytes. PLoS One. 2015;10(e0139644) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bui NT, Ho MT, Kim YM, Lim Y, Cho M. Flavonoids promoting HaCaT migration: II. Molecular mechanism of 4',6,7-trimethoxyisoflavone via NOX2 activation. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang HL, Tsai YC, Korivi M, Chang CT, Hseu YC. Lucidone promotes the Cutaneous Wound Healing process via activation of the PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017;1864:151–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee SH, Zahoor M, Hwang JK, Min do S, Choi KY. Valproic acid induces cutaneous wound healing in vivo and enhances keratinocyte motility. PLoS One. 2012;7(e48791) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeh CJ, Chen CC, Leu YL, Lin MW, Chiu MM, Wang SH. The effects of artocarpin on wound healing: In vitro and in vivo studies. Sci Rep. 2017;7(15599) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15876-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J, Chen Y, Chen Y, Yang Z, You B, Ruan YC, Peng Y. Epidermal CFTR Suppresses MAPK/NF-κB to Promote Cutaneous Wound Healing. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:2262–2274. doi: 10.1159/000447919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gazel A, Nijhawan RI, Walsh R, Blumenberg M. Transcriptional profiling defines the roles of ERK and p38 kinases in epidermal keratinocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:292–308. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saika S, Okada Y, Miyamoto T, Yamanaka O, Ohnishi Y, Ooshima A, Liu CY, Weng D, Kao WW. Role of p38 MAP kinase in regulation of cell migration and proliferation in healing corneal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:100–109. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma GD, He J, Bazan HE. p38 and ERK1/2 coordinate cellular migration and proliferation in epithelial wound healing: Evidence of cross-talk activation between MAP kinase cascades. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21989–21997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.