Abstract

Background: The use of intra-fractional monitoring and correction of prostate position with the Image Guided Radio Therapy (IGRT) system can increase the spatial accuracy of dose delivery. Clarity is a system used for intrafraction prostate-motion management, it provides a real-time visualization of prostate with a trans-perineal ultrasound. The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of Clarity-IGRT on proper intrafraction alignment and monitoring, its impact on Planning Tumor Volume margin and on urinary and rectal toxicity in elderly patients not eligible for surgery. Patients and Methods: Twenty-five elderly prostate cancer patients, median age=75 years (range=75-90 years) were treated with Volumetric Radiotherapy and Clarity-IGRT using 3 different schemes: A) 64.5/72 Gray (Gy) in 30 fractions on prostate and seminal vesicles (6 patients); B) 35 Gy in 5 fractions on prostate and seminal vesicles (12 patients); C): 35 Gy in 5 fractions on prostate (7 patients). Ultrasound identification of the overlapped structures to the detected ones during simulation has been used in each session. A specific software calculates direction and entity of necessary shift to obtain the perfect match. The average misalignment in the three-dimensional space has been determined and shown in a box-plot. Results: All patients completed treatment with mild-moderate toxicity. During treatment, genitourinary toxicity was 32% Grade 1; 4% Grade 2, rectal was 4% Grade 1. At follow-up of 3 months, genitourinary toxicity was 20% Grade 1; 4% Grade 2, rectal toxicity was 4% Grade 2. At follow-up of 6 months, genitourinary toxicity was 4% Grade 1; 4% Grade 2. Rectal toxicity was 4% Grade 2. Conclusion: Radiotherapy with the Clarity System allows a reduction of PTV margins, the amount of fractions can be reduced increasing the total dose, not exacerbating urinary and rectal toxicity with greater patient’s compliance.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, radiotherapy, tracking, ultrasound, hypofractionated radiotherapy

In recent years, several clinical and experimental data have suggested an α/β ratio of 1.5 Gy for prostate cancer and this has encouraged the introduction of hypofractionation in its treatment (1). Prostate cancer α/β ratio seems lower than dose-limiting surrounding tissue of rectum and urinary bladder. The safe dose/fraction escalation improves the therapeutic ratio of prostate cancer radiotherapy, increasing cure rate with reducted toxicity. The α/β ratio for the rectum and bladder is generally assumed to be 3 Gy and 5-10 Gy, respectively. Moderate (dose 2.4-4 Gy) and extreme (dose 6.7-10 Gy) hypofractionation has been investigated in PC over the last decade (2-4). In many reviews and meta-analyzes, the ratio α/β is reported between 1.4 Gy and 1.93 Gy (1,5-8).

Recently completed randomized trials; CHHiP trial (9) and HYPRO trial (10) employ moderate hypofractionation confirmed low α/β (1.8 Gy in the CHHiP study). Hypofractionation is also important for logistical aspects because the short overall treatment time can reduce treatment costs and improve patient quality of life, convenience and compliance. Therefore, introduction of hypofractionation which requires an initial high technology investment for image-guidance, should lead to a reduction in the cost of long-term healthcare.

The guided image allows to verify target volume location or tumor before and/or during treatment delivery. This consents daily verification of patient setup and target position, considering setup error and organ movement (11,12). The variable volumes of stool and gas in the rectum, the bladder filling and the respiratory motion can contribute to prostate gland and seminal vescicles displacement from the bony pelvis. The study of target positioning with imaging or electromagnetic fiducials, in and pre-treatment set-up, aims to clarify target and critical structures position related to the radiation isocenter. The reduction of the PTV margin required for target dose coverage is an important benefit. This entails lower dose to critical structures and possibility to deliver higher biologically effective doses.

Prostate placement is usually done with skin marks, radiographic bony pelvis alignment and, more recently, alignment of fiducial markers implanted prior to the treatment fraction in prostatic SBRT (13). The guided image results in better biochemical control of the tumor and reduced rectal toxicity in treatment by conventional fractionation (14). A single imaging procedure used to position the prostate before dose administration may be insufficient. Intra-fractional monitoring and correction of prostate position may be necessary, thus the spatial accuracy of dose delivery is extremely relevant.

In this article, we describe our experience using the Elekta Clarity Autoscan Ultrasound System, a tracking system that can provide real-time monitoring of prostate position during dose delivery, in hypofractionated radiation treatment. We evaluated the use of Clarity-IGRT in the correct alignment and intrafraction monitoring, its impact on Planning Tumor Volume margin, and on urinary and rectal toxicity in elderly patients (age >75 years) not eligible for surgery.

Patients and Methods

Trial approval. We conducted this study within the CLARO Trial (Clarity System in Radiation Oncology), approved by the Ethics Committee on 06.05.2020 (D. n. 497 of 20.05.2020), Prot.19/20 OSS. We present data about the retrospective Claro Trial, only for patients with an age >75 years.

Patients. This study evaluated 25 elderly prostate cancer patients (median age=75 years; range=75-90 years) treated with Volumetric Radiotherapy and Clarity-IGRT. Six patients were treated with moderate hypofractionation in 30 fractions; 19 patients were treated with extreme hypofractionation in 5 fractions every other day. The type of fractionation has been established in relation with the risk of rectal and urinary toxicity caused by pre-existing comorbidities or high prostate volume. Patients enrolled in the study by risk class or comorbidities had no indication for radiation therapy of whole pelvis.

The target was the prostate gland in 7 patients, prostate plus seminal vesicles in 18 patients. 17 patients underwent hormonal therapy.

Clarity ultrasound system. All patients went through CT simulation with Clarity ultrasound. The Clarity system has two mobile units, the first in the CT room, the second in the treatment room, and are connected to a workstation/server. The workstation has been used for target delineation and prostate monitoring. A ceiling-mounted infrared (IR) camera recognizes the US probe by detecting IR-reflectors. It allows to define the geographical position of reconstructed anatomical structures.

The system has been adjusted to the same coordinate as the CT simulation and treatment rooms: doing so it can overlap the reconstructed US images with the 4D autoscan on the CT images. The calibration procedure was accomplished by means of an alignment phantom (15).

Ultrasound is a non-invasive modality for imaging soft tissue, it is an important guidance of radiation treatment, and furthermore it can minimize the risk of mis-targeting. It can be used for both simulation and treatment with no additional imaging dose (16,17). The transperineal imaging system (Clarity®, Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden) enables the acquisition of volumetric ultrasound images for pre-treatment target localization (daily image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT) or for intra-fractional monitoring of the prostate. Many groups have reported their initial clinical experience for ultrasound imaging system (18-23).

A 3D reference ultrasound image can be acquired and combined with computed tomography (CT) planning using the Automated Fusion and Contouring Workstation (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden) at the time of simulation. The contours of the prostate are subjected to a smoothing process to better represent the edges in ultrasound images. The contours of the prostate are subjected to a smoothing process to better represent the edges in ultrasound images. Before treatment delivery, for each session a 3D guidance ultrasound image had been acquired. The prostate had been manually identified based on the predefined reference ultrasound images and the image guidance volume.

The Clarity® system calculates a 3D vector of displacement between the treatment isocenter and the prostate center reflected in the reference ultrasound image. After applying the 3D shift vector, the system is able to monitor all subsequent 3D displacements of the prostate with respect to the reference image captured as a guide image. This procedure allows to reduce the margins of Planning Target Volume. According to our experience the margins of Planning Target Volume to 5 millimeters in all directions and to 3 millimeters in posterior have been reduced.

Bladder and rectal preparations. To increase the daily reproducibility of the configuration in terms of filling the bladder and rectum, all patients were instructed to drink 500 ml of water 30 minutes before planning the CT scan and before each treatment fraction, and to perform an enema from 2 days. We prescribed Simethicone 40 mg, twice a day to patients.

Treatment planning. A computed tomography simul-CT (Aquilon CT system) and a 3D-US reference scan (Clarity System, Elekta) have been acquired to treatment-planning. Both scans were perfomed using the supine patient position, with kneefix, foot support and the transperineal ultrasound (TPUS) probe in place. Treatment has been scheduled for an Elekta VERSA HD, and for the treatment planning of a volumetric modulated arc technique has been used raystation System, with a simultaneous integrated boost (SIB).

Thereafter, the CT images, contours and treatment plan are transferred to the Clarity planning workstation and recorded in the US reference scan. The target was delineated based on the TPUS images and is defined as Positioning Reference Volume (PRV). The PRV served as a frame of reference for verifying the configuration of the patient’s position.

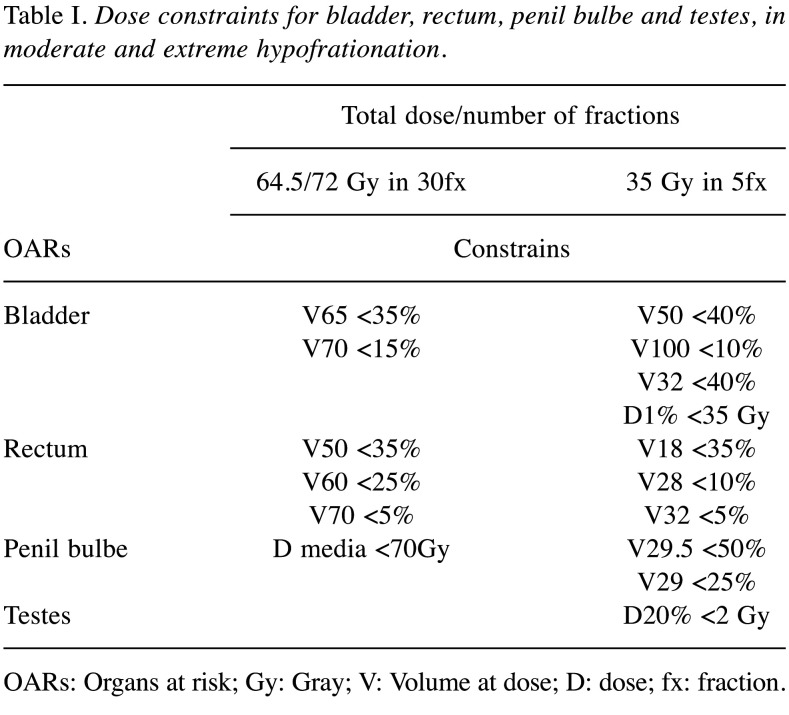

Three different schemes were used: A) 64.5/72 Gy in 30 fractions on prostate and seminal vesicles for 6 patients; B) 35 Gy in 5 fractions on prostate and seminal vesicles for 12 patients; C) 35 Gy in 5 fractions on prostate for 7 patients. The dose has been prescribed following the International Commission of Radiation Units (ICRU 83) reccomandations that dose distribution was optimized to achieve 98% of all PTV receiving at least 95% of the prescription dose, with concurrent hot spot minimization (D2% <107% of prescribed dose). Dose constraints for OARs are summarized in Table I.

Table I. Dose constraints for bladder, rectum, penil bulbe and testes, in moderate and extreme hypofrationation.

OARs: Organs at risk; Gy: Gray; V: Volume at dose; D: dose; fx: fraction.

Image registration and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) analysis. Prior to the radiotherapy session, patient positioning was verified with TPUS imaging followed by CBCT imaging. Configuration error was recorded for both imaging systems for retrospective analysis. Compensation for setup error and verification of treatment location relied on CBCT imaging. CBCT imaging was performed daily for the first 5 fractions, then every five fractions thereafter. TPUS imaging, on the other hand, was performed for each fraction.

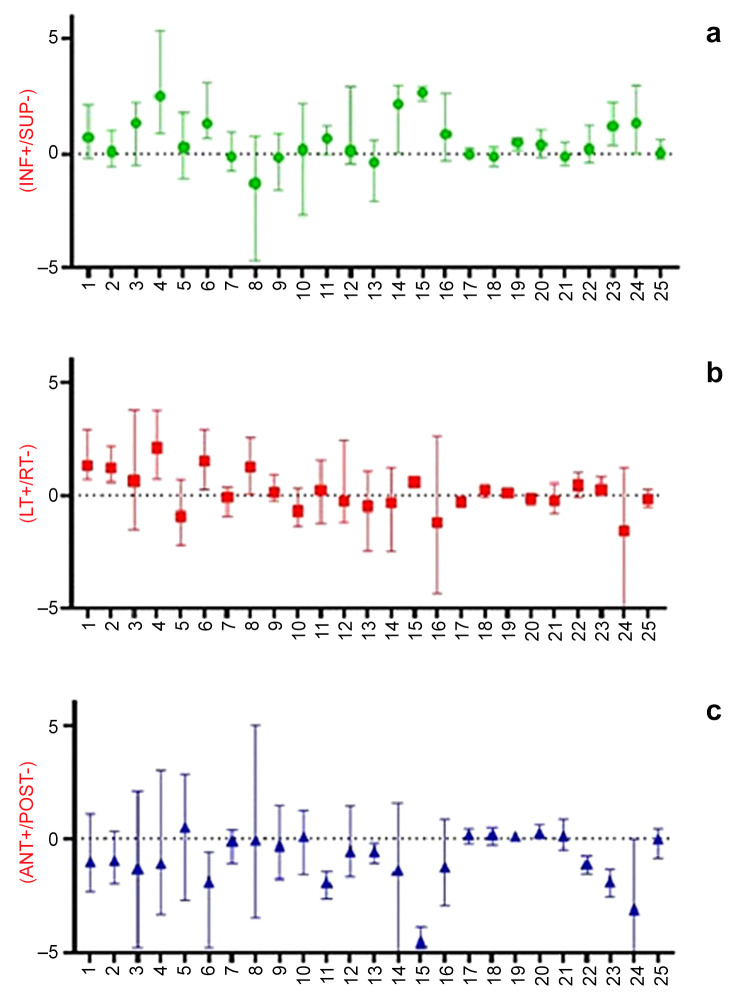

Misalineament daily measurement. For each patient, we calculated misalignments average in three-dimensional space and for each session of treatment, then we elaborated dataset with box-plot.

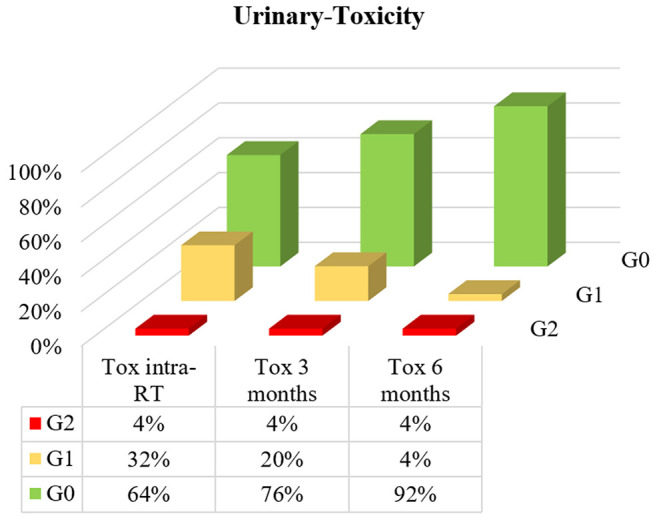

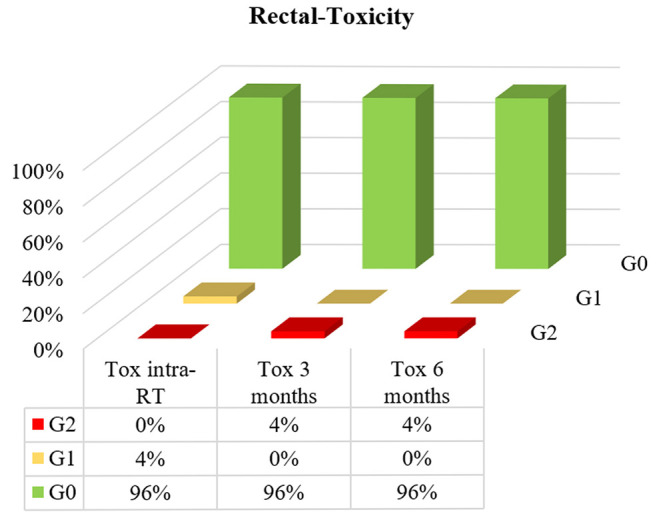

Acute toxicity. We evaluated urinary and rectal toxicity at the beginning of radiotherapy, intra-treatment and every three months until the end of treatment. We evaluated acute urinary and rectal toxicity according to RTOG scale, and we represented the percentages of toxicity with histograms.

Results

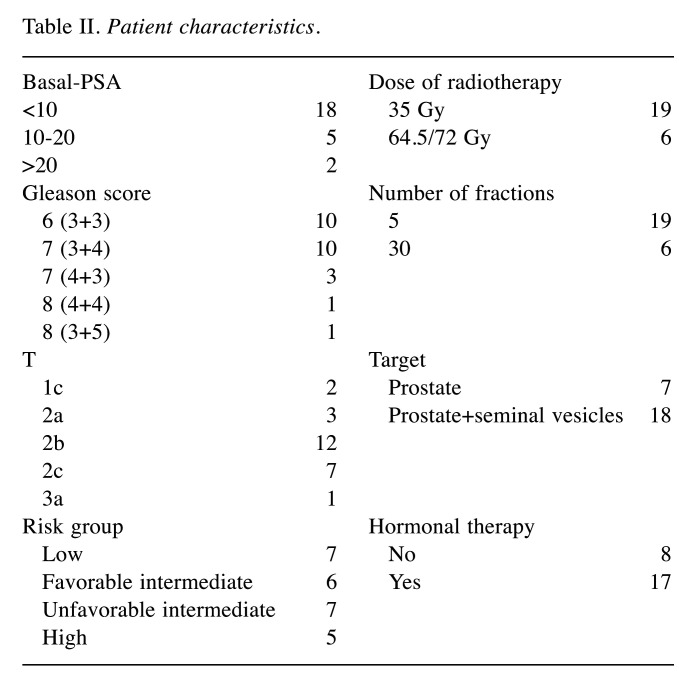

Table II summarizes the characteristics of patients, their risk class and therapies performed. All patients completed radiation treatment with mild to moderate toxicity. During treatment there was no grade 3 or higher of urinary toxicity. Acute G2 urinary toxicity was never greater than 4%. Patients with no urinary toxicity were 64% during treatment, but reached 76% at 3 months and 92% at 6 months (Figure 1).

Table II. Patient characteristics.

Figure 1. Percentage of patients with acute urinary toxicity (RTOG) observed during treatment, at three and six months after radiation treatment.

About rectal acute toxicity, there was no G2 or higher toxicity during the treatment, then there was 4% of G2 at 3 and 6 months. Patients with no rectal toxicity during treatment were 96%, and the same value was registered at 3 and 6 months (Figure 2). For each patient, we calculated the average of misalignments in the three spacial directions and we elaborated the datasets with box-plot (Figure 3). Figure 3 shows in the inferior-superior and left-right directions a movement control within the margins of the Planning Target Volume. In the anterior-posterior direction showing a control in the anterior direction, but not in the posterior where the misalignment could not exceed 3 mm. This intra-treatment control allowed stop treatment and resume after realignment of the target, enabling greater toxicity control.

Figure 2. Percentage of patients with acute rectal toxicity (RTOG) observed during treatment, at three and six months after radiation treatment.

Figure 3. Boxplots of the intrafractional prostate average misalignments recorded for each patient in (a) inferior-superior direction; (b) left-right direction; (c) anterior-posterior direction.

Regarding the dosimetric evaluation, in all cases the dose constraints of the OARs has been respected and their average values are summarized in Table I.

Discussion

The Clarity Autoscan Ultrasound System is an innovative system that allows to follow prostate position during treatment delivery. The ability to fix prostate movement ensures a better accuracy especially in the posterior position where movement is greater. It allows to maintain target coverage and reduce the exposure of organs at risk (19).

There are many systems that monitor prostate position during treatment. CyberKnife (Accuray, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) uses radiopaque intraprostatic fiducial markers 3-dimensionally and stereoscopic kilovoltage x-ray imaging (24,25). Other systems such as Calypso (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA) or RayPilot (Micropos, Gothenburg, Sweden) use electromagnetic transponders independent of treatment platform. Calypso transponders are inserted in place of fiducial markers, so their position is identified by an external receiver (26,27).

In the RayPilot System a single catheter-based transponder is positioned through the urethra to the prostate, and it uses a 30-Hz update frequency (28,29). Finally, the MRIdian system (ViewRay, Bedford, OH) and MR-linac (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden) use magnetic resonance imaging with RT systems to pave the way for adaptive treatment and for motion management (30,31). The Clarity System uses transperineal ultrasound (TPUS) without the use of fiducial markers. This improves patient care by avoiding risk, discomfort and by improving intrafractional movement of the prostate (32). The accuracy and precision of the Clarity Autoscan system have been evaluated in a study on a male pelvic phantom (33).

Some papers analyzed the clinical utility of this system. Total frequency of intrafraction prostate dislocations by direction of different thresholds are mentionated by Richardson and Jacobs (19); the amount of fractions with displacements larger than 2 mm are reported by Baker et al. (15). Ballhausen et al. analyzed data of 6 prostate cancer patients (34). This data had been employed in order to verify the thesis that prostate intrafraction motion can be shaped as a time-dependent “random walk” (35). It was demonstrated that prostate during a fraction tends to get away from treatment isocenter and the deviation from the isocenter intensifies over time. Such results entail that a shorter dose delivery time could be advantageous. The reduction of the treatment time can be obtained using the volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) or the RapidArc radiotherapy technology. Baker et al. examined intrafractional movement of the prostate over a time interval corresponding to a beam activation time for RapidArc (120-150 s) (33).

They noted that the displacement grows over time, in line with the findings of Ballhausen et al. (35). Richardson et al. didn’t use the Clarity Autoscan system to assess the intrafraction prostate motion during intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) because it has longer treatment time (33).

Back prostate movement seems to be the most common. Richardson et al. considered the intrafraction prostate displacement duration as a part of the overall treatment time, and the duration varied considerably between patients (33). For movements greater than 3 mm in the back direction, a duration from 2% of the treatment time up to 92% of the treatment time was observed for individual patients. Guillet et al. estimated the dosimetric effect of intrafraction motion and it has been reported some prostate movement results (36).

In this study, the movements were more in the AP direction, with 18% of the short treatment sessions (140 s) and 31% of the treatment the longest (290 s) with further movements of 3 mm and the dosimetric impact of intrafractional movement increased with the duration of treatment.

Conclusion

Our experience confirms the importance of IGRT for dose delivery precision in prostate cancer (PCa) radiotherapy (37-40). The cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) remains an important IGRT system even if it involves additional radiation exposure, (40-42) which might contribute to the incremented morbidity of secondary malignancies after radiotherapy (43). Ultrasound (US) is a more suitable option that allows real-time monitoring of the target in a non-invasive and non-ionizing way (44).

Our data confirm that the Clarity System (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden), one the latest-generation US-based guidance systems, could be a new approach to ensuring accuracy while reducing target margins (45-50). Consequently, it allows to reduce the number of fractions, and increase the total dose without increasing urinary and rectal toxicity, which remains lower in incidence compared to common toxicities after prostate EBRT (51). Mild toxicity and shorter duration of treatment resulted in greater patient’s compliance, therefore this type of approach can be very useful in the elderly patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

RDF, PM, VB, SaP, SR, SiP conceived the study and led the protocol development; DA, GA, GQ, AI, LC, GG, RM, MS, GF, AC, IT, GI contributed to the development of the study protocol. AP, AC, IT and RDF (lead trial statistician) developed the study design and statistical analysis plan. All Authors provided feedback on drafts of this paper and read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The Authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Diana d’Alterio for the contribute in the manuscript editing.

References

- 1.Dasu A, Toma-Dasu I. Prostate alpha/beta revisited — an analysis of clinical results from 14 168 patients. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(8):963–974. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.719635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tree AC, Khoo VS, van As NJ, Partridge M. Is biochemical relapse-free survival after profoundly hypofractionated radiotherapy consistent with current radiobiological models. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2014;26(4):216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemente S, Nigro R, Oliviero C, Marchioni C, Esposito M, Giglioli FR, Mancosu P, Marino C, Russo S, Stasi M, Strigari L, Veronese I, Landoni V. Role of the technical aspects of hypofractionated radiation therapy treatment of prostate cancer: A review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(1):182–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koontz BF, Bossi A, Cozzarini C, Wiegel T, D’Amico A. A systematic review of hypofractionation for primary management of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68(4):683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Proust-Lima C, Taylor JM, Sécher S, Sandler H, Kestin L, Pickles T, Bae K, Allison R, Williams S. Confirmation of a low α/β ratio for prostate cancer treated by external beam radiation therapy alone using a post-treatment repeated-measures model for PSA dynamics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(1):195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miralbell R, Roberts SA, Zubizarreta E, Hendry JH. Dose-fractionation sensitivity of prostate cancer deduced from radiotherapy outcomes of 5,969 patients in seven international institutional datasets: α/β=1.4 (0.9-2.2) Gy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(1):e17–e24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koontz BF, Bossi A, Cozzarini C, Wiegel T, D’Amico A. A systematic review of hypofractionation for primary management of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68(4):683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogelius IR, Bentzen SM. Meta-analysis of the alpha/beta ratio for prostate cancer in the presence of an overall time factor: Bad news, good news, or no news. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85(1):89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, Khoo V, Birtle A, Bloomfield D, Graham J, Kirkbride P, Logue J, Malik Z, Money-Kyrle J, O’Sullivan JM, Panades M, Parker C, Patterson H, Scrase C, Staffurth J, Stockdale A, Tremlett J, Bidmead M, Mayles H, Naismith O, South C, Gao A, Cruickshank C, Hassan S, Pugh J, Griffin C, Hall E, CHHiP Investigators Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Incrocci L, Wortel RC, Alemayehu WG, Aluwini S, Schimmel E, Krol S, van der Toorn PP, Jager H, Heemsbergen W, Heijmen B, Pos F. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with localised prostate cancer (HYPRO): Final efficacy results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1061–1069. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Bari B, Arcangeli S, Ciardo D, Mazzola R, Alongi F, Russi EG, Santoni R, Magrini SM, Jereczek-Fossa BA, on the behalf of the Italian Association of Radiation Oncology (AIRO) Extreme hypofractionation for early prostate cancer: Biology meets technology. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;50:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Bari B, Fiorentino A, Arcangeli S, Franco P, D’Angelillo RM, Alongi F. From radiobiology to technology: What is changing in radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14(5):553–564. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2014.883282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelefsky MJ, Kollmeier M, McBride S, Varghese M, Mychalczak B, Gewanter R, Garg MK, Happersett L, Goldman DA, Pei I, Lin M, Zhang Z, Cox BW. Five-year outcomes of a phase 1 dose-escalation study using stereotactic body radiosurgery for patients with low-risk and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;104(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson DR, Tree AC, van As NJ. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2015;27(5):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker M, Behrens CF. Determining intrafractional prostate motion using four dimensional ultrasound system. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:484. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2533-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han B, Najafi M, Cooper DT, Lachaine M, von Eyben R, Hancock S, Hristov D. Evaluation of transperineal ultrasound imaging as a potential solution for target tracking during hypofractionated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13(1):151. doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-1097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cury FL, Shenouda G, Souhami L, Duclos M, Faria SL, David M, Verhaegen F, Corns R, Falco T. Ultrasound-based image guided radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Comparison of cross-modality and intramodality methods for daily localization during external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(5):1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.07.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trivedi A, Ashikaga T, Hard D, Archambault J, Lachaine M, Cooper DT, Wallace HJ 3rd. Development of 3-dimensional transperineal ultrasound for image guided radiation therapy of the prostate: Early evaluations of feasibility and use for inter- and intrafractional prostate localization. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7(1):e27–e33. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson AK, Jacobs P. Intrafraction monitoring of prostate motion during radiotherapy using the Clarity® Autoscan Transperineal Ultrasound (TPUS) system. Radiography (Lond) 2017;23(4):310–313. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, Ballhausen H, Hegemann NS, Reiner M, Tritschler S, Gratzke C, Manapov F, Corradini S, Ganswindt U, Belka C. Comparison of prostate positioning guided by three-dimensional transperineal ultrasound and cone beam CT. Strahlenther Onkol. 2017;193(3):221–228. doi: 10.1007/s00066-016-1084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilman S, Smith R, Masson S, Coomber H, Bahl A, Challapalli A, Jacobs P. Implementation of a daily transperineal ultrasound system as image-guided radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2017;29(1):e49. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fast MF, O’Shea TP, Nill S, Oelfke U, Harris EJ. First evaluation of the feasibility of MLC tracking using ultrasound motion estimation. Med Phys. 2016;43(8):4628. doi: 10.1118/1.4955440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fargier-Voiron M, Presles B, Pommier P, Munoz A, Rit S, Sarrut D, Biston MC. Evaluation of a new transperineal ultrasound probe for inter-fraction image-guidance for definitive and post-operative prostate cancer radiotherapy. Phys Med. 2016;32(3):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2016.01.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilby W, Dooley JR, Kuduvalli G, Sayeh S, Maurer CR Jr. The cyberknife robotic radiosurgery system in 2010. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2010;9(5):433–452. doi: 10.1177/153303461000900502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seisen T, Drouin SJ, Phé V, Parra J, Mozer P, Bitker MO, Cussenot O, Rouprêt M. Current role of image-guided robotic radiosurgery (Cyberknife(®)) for prostate cancer treatment. BJU Int. 2013;111(5):761–766. doi: 10.1111/bju.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keall PJ, Colvill E, O’Brien R, Caillet V, Eade T, Kneebone A, Hruby G, Poulsen PR, Zwan B, Greer PB, Booth J. Electromagnetic-guided MLC tracking radiation therapy for prostate cancer patients: Prospective clinical trial results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101(2):387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willoughby TR, Kupelian PA, Pouliot J, Shinohara K, Aubin M, Roach M 3rd, Skrumeda LL, Balter JM, Litzenberg DW, Hadley SW, Wei JT, Sandler HM. Target localization and real-time tracking using the Calypso 4D localization system in patients with localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(2):528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravkilde T, Keall PJ, Grau C, Høyer M, Poulsen PR. Time-resolved dose distributions to moving targets during volumetric modulated arc therapy with and without dynamic MLC tracking. Med Phys. 2013;40(11):111723. doi: 10.1118/1.4826161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kindblom J, Ekelund-Olvenmark AM, Syren H, Iustin R, Braide K, Frank-Lissbrant I, Lennernäs B. High precision transponder localization using a novel electromagnetic positioning system in patients with localized prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2009;90(3):307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mutic S, Dempsey JF. The ViewRay system: Magnetic resonance-guided and controlled radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2014;24(3):196–199. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pathmanathan AU, van As NJ, Kerkmeijer LGW, Christodouleas J, Lawton CAF, Vesprini D, van der Heide UA, Frank SJ, Nill S, Oelfke U, van Herk M, Li XA, Mittauer K, Ritter M, Choudhury A, Tree AC. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided adaptive radiation therapy: A “Game changer” for prostate treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100(2):361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fontanarosa D, van der Meer S, Bamber J, Harris E, O’Shea T, Verhaegen F. Review of ultrasound image guidance in external beam radiotherapy: I. Treatment planning and inter-fraction motion management. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60(3):R77–114. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/3/R77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu AS, Najafi M, Hristov DH, Phillips T. Intrafractional tracking accuracy of a transperineal ultrasound image guidance system for prostate radiotherapy. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017;16(6):1067–1078. doi: 10.1177/1533034617728643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballhausen H, Li M, Hegemann NS, Ganswindt U, Belka C. Intra-fraction motion of the prostate is a random walk. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60(2):549–563. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/2/549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ballhausen H, Reiner M, Kantz S, Belka C, Söhn M. The random walk model of intrafraction movement. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58(7):2413–2427. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/7/2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fargier-Voiron M, Presles B, Pommier P, Munoz A, Rit S, Sarrut D, Biston MC. Evaluation of a new transperineal ultrasound probe for inter-fraction image-guidance for definitive and post-operative prostate cancer radiotherapy. Phys Med. 2016;32(3):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2016.01.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korreman S, Rasch C, McNair H, Verellen D, Oelfke U, Maingon P, Mijnheer B, Khoo V. The European society of therapeutic radiology and oncology-european institute of radiotherapy (ESTRO-EIR) report on 3D CT-based in-room image guidance systems: A practical and technical review and guide. Radiother Oncol. 2010;94(2):129–144. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zelefsky MJ, Kollmeier M, Cox B, Fidaleo A, Sperling D, Pei X, Carver B, Coleman J, Lovelock M, Hunt M. Improved clinical outcomes with high-dose image guided radiotherapy compared with non-IGRT for the treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(1):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perrier L, Morelle M, Pommier P, Lagrange JL, Laplanche A, Dudouet P, Supiot S, Chauvet B, Nguyen TD, Crehange G, Beckendorf V, Pene F, Muracciole X, Bachaud JM, Le Prisé E, de Crevoisier R. Cost of prostate image-guided radiation therapy: Results of a randomized trial. Radiother Oncol. 2013;106(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ariyaratne H, Chesham H, Pettingell J, Alonzi R. Image-guided radiotherapy for prostate cancer with cone beam CT: Dosimetric effects of imaging frequency and PTV margin. Radiother Oncol. 2016;121(1):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walter C, Boda-Heggemann J, Wertz H, Loeb I, Rahn A, Lohr F, Wenz F. Phantom and in-vivo measurements of dose exposure by image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT): MV portal images vs. kV portal images vs. cone-beam CT. Radiother Oncol. 2007;85(3):418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perks JR, Lehmann J, Chen AM, Yang CC, Stern RL, Purdy JA. Comparison of peripheral dose from image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) using kV cone beam CT to intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) Radiother Oncol. 2008;89(3):304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Crevoisier R, Bayar MA, Pommier P, Muracciole X, Pêne F, Dudouet P, Latorzeff I, Beckendorf V, Bachaud JM, Laplanche A, Supiot S, Chauvet B, Nguyen TD, Bossi A, Créhange G, Lagrange JL. Daily versus weekly prostate cancer image guided radiation therapy: Phase 3 multicenter randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102(5):1420–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.07.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Western C, Hristov D, Schlosser J. Ultrasound imaging in radiation therapy: From interfractional to intrafractional guidance. Cureus. 2015;7(6):e280. doi: 10.7759/cureus.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNair HA, Mangar SA, Coffey J, Shoulders B, Hansen VN, Norman A, Staffurth J, Sohaib SA, Warrington AP, Dearnaley DP. A comparison of CT- and ultrasound-based imaging to localize the prostate for external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(3):678–687. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serago CF, Buskirk SJ, Igel TC, Gale AA, Serago NE, Earle JD. Comparison of daily megavoltage electronic portal imaging or kilovoltage imaging with marker seeds to ultrasound imaging or skin marks for prostate localization and treatment positioning in patients with prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(5):1585–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scarbrough TJ, Golden NM, Ting JY, Fuller CD, Wong A, Kupelian PA, Thomas CR Jr. Comparison of ultrasound and implanted seed marker prostate localization methods: Implications for image-guided radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(2):378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cury FL, Shenouda G, Souhami L, Duclos M, Faria SL, David M, Verhaegen F, Corns R, Falco T. Ultrasound-based image guided radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Comparison of cross-modality and intramodality methods for daily localization during external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(5):1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.07.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li M, Ballhausen H, Hegemann NS, Reiner M, Tritschler S, Gratzke C, Manapov F, Corradini S, Ganswindt U, Belka C. Comparison of prostate positioning guided by three-dimensional transperineal ultrasound and cone beam CT. Strahlenther Onkol. 2017;193(3):221–228. doi: 10.1007/s00066-016-1084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han B, Najafi M, Cooper DT, Lachaine M, von Eyben R, Hancock S, Hristov D. Evaluation of transperineal ultrasound imaging as a potential solution for target tracking during hypofractionated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13(1):151. doi: 10.1186/s13014-018-1097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meng K, Lim K, Lee CC, Chia D, Ooi KH, Soon YY, Tey J. clinical outcomes of dose-escalated radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: A single-institution experience. In Vivo. 2020;34(2):757–765. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]