Key Points

Question

Does an association exist between tinnitus (and its interference with daily life) and mental health problems?

Findings

This cohort study involving 5418 participants found that bothersome tinnitus was associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and poorer sleep quality than nonbothersome tinnitus. At the end of a 4-year follow-up of 975 of these participants, baseline tinnitus appeared to be associated with mental health problems, but this association was not statistically significant.

Meaning

Tinnitus was associated with experiencing more mental health problems, even over time and among individuals who reported that their tinnitus was not interfering with daily life.

Abstract

Importance

Tinnitus is a common disorder, but its impact on daily life varies widely in population-based samples. It is unclear whether this interference in daily life is associated with mental health problems that are commonly detected in clinical populations.

Objective

To investigate the association of tinnitus and its interference in daily life with symptoms of depression and anxiety and poor sleep quality in a population-based sample of middle-aged and elderly persons in a cross-sectional analysis and during a 4-year follow-up.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study evaluated data from the population-based Rotterdam Study of individuals 40 years or older living in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Between 2011 and 2016, data on tinnitus were obtained during a home interview at least once for 6128 participants. Participants with information on depressive and anxiety symptoms and self-rated sleep quality, with Mini-Mental State Examination scores indicating unimpaired cognition, and with repeatedly obtained tinnitus and mental health outcome data were included. Data analyses were conducted between September 2019 and April 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The presence of tinnitus and its interference with daily life were assessed during a home interview. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression, anxiety symptoms with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and sleep quality with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Linear regression analyses and linear mixed models adjusted for relevant confounders were used to assess the cross-sectional and longitudinal association of tinnitus with mental health.

Results

Of 5418 complete-case participants (mean [SD] age, 69.0 [9.8] years; 3131 [57.8%] women), 975 (mean [SD] age, 71.7 [4.5] years; 519 [53.2%] women) had repeated measurements available for follow-up analyses. Compared with participants without tinnitus and participants with nonbothersome tinnitus, participants with tinnitus interfering with daily life reported more depressive (difference, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.11-0.28) and anxiety (difference, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.08-0.22) symptoms and poorer sleep quality (difference, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.03-0.16). Compared with participants without tinnitus, participants with nonbothersome tinnitus also reported more depressive (difference, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.03-0.09) and anxiety (difference, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.02-0.07) symptoms and poorer sleep quality (difference, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.03-0.08). Individuals indicating more interference with daily life reported having more mental health problems. During a mean follow-up of 4.4 years (range, 3.5-5.1 years), participants with tinnitus reported more anxiety symptoms and poorer sleep quality than those without tinnitus.

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings of this population-based cohort study indicate that tinnitus was associated with more mental health problems in middle-aged and elderly persons in the general population, in particular when tinnitus interfered with daily life but not solely. Over time, more severe tinnitus was associated with an increase in anxiety symptoms and poor sleep quality. This outcome suggests that mental health problems may be part of the burden of tinnitus, even among individuals who do not report their tinnitus interfering with daily life.

This cohort study with cross-sectional analyses and 4-year follow-up assesses whether the presence of tinnitus that interferes or does not interfere with daily life is associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, or poor sleep quality in a population-based sample of individuals 40 years or older who reside in the Netherlands.

Introduction

Tinnitus, commonly defined as a sound that is heard in the absence of an objective sound source, is a common condition in the general population, with a prevalence between 9% and 40%.1 For most individuals, tinnitus is not bothersome, but for about 5% to 20% of people experiencing tinnitus, the condition significantly impairs their daily life and is regarded as severe tinnitus.1

Tinnitus has been frequently associated with a range of psychological conditions, such as depression, anxiety, irritability, sleep disturbances, subjective distress, and intense worrying.2 These associations have been extensively researched in clinical studies,3,4 including highly selected populations containing individuals with the highest tinnitus-associated burden of disease. More recently, cross-sectional epidemiological studies in population-based cohorts have confirmed associations of the prevalence of tinnitus with depression and anxiety5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 as well as associations between tinnitus and sleep disorders.14,15 Because most of those studies did not take into account the interference of tinnitus with daily life, it remains unclear whether the associations are mainly observed in the high-severity tinnitus group, with high resemblance to clinical tinnitus populations, or are also applicable to the subclinical tinnitus population.

The association between tinnitus and mental health is potentially affected by grade of hearing loss. Hearing loss commonly co-occurs with tinnitus (43.2%16), is known as an accelerating factor for tinnitus,17 and has also been suggested to be associated with mental health.18 To date, clinical studies suggest that tinnitus, hearing loss, and mental health problems coexist,19 but no population-based studies of tinnitus have taken hearing loss into account. Lastly, due to the lack of longitudinal studies, the temporality of the association of tinnitus with mental health is still under debate. For example, tinnitus may precede mental health problems, mental health problems may precede tinnitus, or there may be a bidirectional association between mental health problems and tinnitus. In addition, the current recommended therapy for tinnitus is cognitive behavioral therapy, which is a psychological treatment that also entails components that may benefit mental health.20,21,22

To gain more insight into the association between tinnitus and mental health problems and the possible underlying mechanisms, we investigated the association between tinnitus and depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and self-rated sleep quality in a relatively large population of middle-aged and older adults, focusing on the interference of tinnitus with daily life and the presence of hearing loss. Furthermore, we aimed to gain insight into the association of tinnitus with the development of mental health problems over time by analyzing longitudinal data across 4 years.

Methods

Setting and Study Population

This cohort study was embedded in the Rotterdam Study, a prospective population-based cohort of middle-aged and older persons. The Rotterdam Study was initiated in 1990 and investigates determinants and consequences of aging and age-related disease. The study population consists of individuals 40 years or older living in the well-defined Ommoord district of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. All participants were invited to undergo extensive examinations at study entry and subsequently every 3 to 6 years. Further details of the study have been described elsewhere.23 The Rotterdam Study has been entered into the Netherlands National Trial Register24 and into the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform25 under the shared catalog number NTR6831. The Rotterdam Study has been approved by the medical ethics committee of the Erasmus MC and by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study, which was obtained in a manner consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki,26 and to have their information obtained from treating physicians. No one received compensation or was offered any incentive for participating in this study.

Tinnitus and hearing assessments were introduced into the core study protocol in 2011. Between 2011 and 2016, data on tinnitus were obtained during a home interview at least once for 6128 participants. Of those, we excluded 158 participants who had no information on depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, or self-rated sleep quality available from the same home interview. In addition, because poor cognitive status may impair the ability to complete questionnaires validly, participants were also excluded if their Mini-Mental State Examination score was lower than 23 (n = 143) or if these data were missing (n = 409). Of the remaining 5418 participants, repeatedly obtained data on tinnitus and mental health outcomes were obtained for 1140 participants, with a mean follow-up time of 4.4 years (range, 3.5-5.1 years). Participants were excluded from the longitudinal analysis when there was incident tinnitus (n = 96) or when they no longer reported tinnitus (n = 69) at follow-up. Thus, 5418 complete-case participants were included in the cross-sectional analyses, and 975 complete-case eligible participants were included in the longitudinal analysis.

Measurements

Tinnitus

Tinnitus presence was assessed during the home interview. Participants were asked if they experienced sounds in their head or in (one of) their ears, such as whizzing, beeping, or humming, without an objective external sound source being present. Possible answers to this question were “no, never,” “yes, less than once a week,” “yes, more than once a week but not daily,” and “yes, daily.” Participants who reported having symptoms at least once a week were considered to have tinnitus. Because of the heterogeneity and often temporary character of tinnitus, experiencing symptoms less than once a week was not considered having tinnitus. Participants who indicated experiencing tinnitus were additionally asked whether the tinnitus interfered with their daily life (yes or no). If participants reported daily tinnitus independent of whether they reported interference with daily life, they were asked to complete the simplified Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI-s), a validated questionnaire to assess impairments in daily life caused by tinnitus. This 10-item inventory uses possible scores of 0 (no), 2 (sometimes), or 4 (yes) per item, and a score of 16 or higher represents a moderate to severe impairment.27

Based on the questions described above, we identified 3 groups at baseline: (1) participants without tinnitus, (2) participants with tinnitus but not interfering with daily life (nonbothersome tinnitus), and (3) participants with tinnitus interfering with daily life (bothersome tinnitus). The THI-s scores were assessed separately for anyone experiencing daily tinnitus.

Depressive Symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale was used to assess depressive symptoms. The CES-D is a validated instrument that is widely used to estimate self-reported depressive symptoms.28 The CES-D is a 20-item questionnaire, with each item scored on a 4-point scale from 0 (low) to 3 (high). The cutoff value for clinically relevant depressive symptoms was set at 16 points.28,29 If not all but more than 75% of the items were completed, a weighted total score was calculated; if less than 75% of the questions were answered, the CES-D was set to missing.

Anxiety Symptoms

The anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A)30 was used to assess anxiety symptoms. The HADS-A is a 7-item questionnaire, with each item scored on a 4-point scale from 0 (never) to 3 (usually). A weighted global score was calculated by multiplying by 7/6 when 6 components were available. If less than 6 component scores were available, the HADS-A was set to missing. The total score ranged between 0 and 21, with the cutoff value for clinically relevant anxiety symptoms set at 8 points.30

Sleep Outcomes

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to measure self-rated sleep quality. The PSQI is a 19-item questionnaire covering sleep-associated problems. The PSQI covers 7 components, reported on a 4-point scale from 0 (never) to 3 (daily).31 A weighted global score was calculated by multiplying by 7/6 when 6 components were available. If less than 6 components were available, the PSQI was set to missing. The final global score ranged between 0 and 21. The cutoff value for clinically relevant poor sleeping quality was 5 points.31

Other Variables

The highest achieved educational level was scored using the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) classification.32 To determine body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), participant height and weight were assessed without heavy clothing and shoes using calibrated scales at the research center. Smoking data were collected through self-report and categorized into never, former, or current smoking. Alcohol consumption (glasses per day) was assessed through self-report. Pure-tone audiometry was performed in a soundproof booth by a trained health care professional. Air conduction thresholds for both ears were obtained at frequencies of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 kHz.23 Pure-tone average hearing thresholds (PTAs), calculated for 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz, were determined from the best-hearing ear as proposed by the World Health Organization.33 Hearing loss was defined as PTA 25 dB hearing level (dB HL) or higher.33 The Mini-Mental State Examination was administered during the home interview to screen for cognitive status.34

Statistical Analysis

Demographic Analyses

The demographic characteristics of the population were described. Descriptive statistics were used to assess and compare differences in characteristics among participants with or without tinnitus. For continuous variables with a normal distribution, we described the mean (SD) value and used a t test for statistical testing. For continuous variables with a nonnormal distribution, we described the median value and the interquartile range and used a Mann-Whitney test to compare groups. For categorical variables, we described the number (%) and used the χ2 test to compare the groups. Depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and sleep quality scores were all log transformed (score +1) to achieve a normal distribution of the residuals.

Cross-sectional Analyses

To estimate the cross-sectional association of tinnitus with depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and sleep quality at baseline, we used linear and logistic regression analyses. Participants with bothersome tinnitus and participants with nonbothersome tinnitus were compared with participants without tinnitus (reference group) and with each other (nonbothersome tinnitus as the reference group). To account for confounding, 2 models were used: model 1 was adjusted for sex and age, and model 2 was additionally adjusted for the highest achieved educational level, BMI, alcohol use, smoking, and hearing threshold.

In addition, all cross-sectional regression analyses were repeated with the entire data set stratified for hearing loss (PTA≥25 dB HL) because this variable is the most important risk factor for tinnitus. In a subgroup of 625 participants with daily tinnitus symptoms and an available THI-s score, we also assessed the associations of tinnitus impairment with mental health, comparing participants with a relevant tinnitus impairment (THI-s score ≥16) to those with no tinnitus impairment (THI-s score <16).

Longitudinal Analyses

We used linear mixed models with random intercepts and slopes to explore the longitudinal association between tinnitus and depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and sleep quality over time. In each model, we entered follow-up time in years after baseline measurement to use as a time variable and added an interaction term of tinnitus and follow-up time in all models to allow for slope differences in the association between mental health outcomes and time explained by the presence of tinnitus. The linear tinnitus term (intercept difference) and the interaction term between tinnitus and follow-up time (slope difference) are the main outcomes in this longitudinal analysis. Confounder adjustment was performed per model 1 and model 2 as fixed effects. The control variables were included as fixed effects.

Data analyses were conducted between September 2019 and April 2020 using SPSS statistics, version 24.0 (IBM Corp) for data handling and cross-sectional analyses and R statistical software, version 4.0.4 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with the lme package for longitudinal analyses. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cross-sectional Association of Tinnitus With Mental Health

For the cross-sectional analyses, 5418 participants were included, with a mean (SD) age of 69.0 (9.8) years, and 3131 (57.8%) were women. In total, 4245 participants (78.4%) reported no prevalent tinnitus, 1063 participants (19.6%) reported nonbothersome tinnitus, and 110 participants (2.0%) reported bothersome tinnitus (Table 1). Of 110 participants with bothersome tinnitus, 94 experienced tinnitus daily, and 16 experienced tinnitus less frequently.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | Participants without tinnitus | Participants with tinnitus | |||

| Bothersome | Nonbothersome | ||||

| No. | 5418 | 4245 | 110 | 1063 | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 69.0 (9.8) | 69.0 (9.8) | 68.6 (8.7) | 69.3 (9.7) | .66 |

| Female | 3131 (57.8) | 2476 (58.3) | 59 (53.6) | 561 (52.8) | .004 |

| Male | 2287 (42.2) | 1769 (41.7) | 51 (46.4) | 502 (47.2) | |

| Educational level | |||||

| Primary | 394 (7.3) | 297 (7.0) | 12 (10.9) | 85 (8.0) | .29 |

| Lower | 2103 (38.8) | 1625 (38.3) | 44 (40.0) | 434 (40.8) | |

| Middle | 1619 (29.9) | 1282 (30.2) | 33 (30.0) | 304 (28.6) | |

| Higher | 1251 (23.1) | 999 (23.5) | 21 (19.1) | 231 (21.7) | |

| Missing | 51 (1.0) | 42 (1.0) | 0 | 9 (1.0) | |

| THI-s ≥16b | 88 (13.4) | NA | 41 (51.3) | 47 (8.6) | <.001 |

| Hearing threshold, mean (SD), dB HLc,d | 23.6 (13.4) | 22.6 (12.9) | 30.8 (14.9) | 26.8 (14.5) | <.001 |

| Hearing loss | 1742 (32.2) | 1245 (29.3) | 56 (50.9) | 441 (41.5) | <.001 |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Depressivee | |||||

| Weighted score, median (IQR)f | 3 (1-8) | 3 (1-7) | 6 (2-12) | 4 (1-9) | <.001 |

| Clinically relevant | 500 (9.2) | 371 (8.7) | 17 (15.5) | 112 (10.5) | .01 |

| Anxietyg | |||||

| Weighted score, median (IQR)f | 2 (0-4) | 2 (0-4) | 3 (1-6) | 2 (0-5) | <.001 |

| Clinically relevant | 453 (8.4) | 328 (7.7) | 14 (12.7) | 111 (10.4) | .004 |

| Sleep qualityh | |||||

| Weighted score, median (IQR)f | 3 (1-6) | 3 (1-5) | 4 (2-7) | 3 (2-6) | <.001 |

| Clinically relevant | 1361 (25.1) | 1013 (23.9) | 38 (34.5) | 310 (29.2) | <.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD)d | 27.5 (4.4) | 27.4 (4.4) | 27.8 (3.9) | 27.7 (4.2) | .30 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 1728 (31.9) | 1398 (32.9) | 34 (30.9) | 296 (27.8) | .02 |

| Past | 2809 (51.8) | 2156 (50.8) | 60 (54.5) | 593 (55.8) | |

| Current | 798 (14.7) | 622 (14.7) | 14 (12.7) | 162 (15.2) | |

| Alcohol, U/d | |||||

| Never | 792 (14.6) | 631 (14.9) | 16 (14.5) | 145 (13.6) | .60 |

| 1-2 | 3526 (65.1) | 2766 (65.2) | 70 (63.6) | 690 (64.9) | |

| 3-4 | 862 (15.9) | 665 (15.7) | 22 (20.0) | 175 (16.5) | |

| >5 | 229 (4.2) | 177 (4.2) | 2 (1.8) | 50 (4.7) | |

| MMSE, median (IQR)f | 28 (27-29) | 28 (27-29) | 28 (27-29) | 29 (27-29) | .93 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression; dB HL, decibel hearing level; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IQR, interquartile range; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NA, not applicable; THI-s, simplified Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.

No. (%) is shown for categorical variables, and a χ2 test was used to compare groups.

Percentage of participants who filled out the THIS-s.

Mean hearing loss was determined for 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz frequencies in the best ear.

Values are mean (SD) for normally distributed continuous variables, and a t test was used to compare groups.

Depressive symptoms were measured with the CES-D list; a score of 16 or higher was considered clinically relevant.

Median (IQR) for nonnormally distributed continuous variables, and a Mann-Whitney test was used to compare groups.

Anxiety symptoms were measured with the HADS-A anxiety subscale; a score of 8 or higher was considered clinically relevant.

Sleep quality was self-reported with the PSQI; a score of 6 or higher was considered as clinically relevant lower sleep quality.

Participants with bothersome tinnitus scored significantly higher on depressive symptoms (all differences are log transformed [score +1]) (difference, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.11-0.28), anxiety symptoms (difference, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.08-0.22), and sleep quality (difference, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.03-0.16) compared with participants without tinnitus as well as compared with participants with nonbothersome tinnitus when adjusted for confounders (Table 2). Participants with nonbothersome tinnitus also scored significantly higher on depressive symptoms (difference, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.03-0.09), anxiety symptoms (difference, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.02-0.07), and sleep quality (difference, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.03-0.08) compared with participants without tinnitus (Table 2). When using cutoffs to indicate clinically relevant symptoms for these mental health outcomes, we found effect sizes indicating similar associations (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Associations Between Participants With Tinnitus With or Without Interference in Daily Life and Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms and Self-reported Sleep Quality.

| Tinnitus | Difference (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Sleep quality | ||

| Depressive | Anxiety | ||

| No tinnitus | |||

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Bothersome | |||

| Model 1b | 0.21 (0.11-0.28)d | 0.16 (0.09-0.23)d | 0.09 (0.02-0.15)d |

| Model 2c | 0.20 (0.11-0.28)d | 0.15 (0.08-0.22)d | 0.10 (0.03-0.16)d |

| Nonbothersome | |||

| Model 1b | 0.07 (0.04-0.10)d | 0.05 (0.02-0.07)d | 0.05 (0.03-0.07)d |

| Model 2c | 0.06 (0.03-0.09)d | 0.05 (0.02-0.07)d | 0.05 (0.03-0.08)d |

Difference represents the difference in the log-transformed scores (raw score +1) of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression scale, the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, or the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in participants with nonbothersome or bothersome tinnitus.

Adjusted for sex and age.

Further adjusted for highest achieved educational level, hearing loss, body mass index, alcohol use, and smoking status.

Significant effect estimates (P < .05).

Because the presence of hearing loss may affect the association between tinnitus and mental health outcomes, we repeated the analyses in a data set stratified on hearing loss (≥25 dB HL). These analyses suggested that associations of tinnitus with mental health were found in both groups of participants with or without hearing loss (Table 3). Yet, when using a cutoff to distinguish between clinically relevant mental health outcomes, the results were mixed and apparently more pronounced for the group without hearing loss (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Associations Between Participants With Tinnitus With or Without Interference in Daily Life and Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms and Self-reported Sleep Quality, Stratified by Hearing Impairment.

| Tinnitus | Difference (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Sleep quality | ||

| Depressive | Anxiety | ||

| No hearing loss, <25 dB HL (n = 3676) | |||

| No tinnitus | |||

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Bothersome | |||

| Model 1b | 0.21 (0.07 to 0.35)d | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.24)d | 0.06 (−0.04 to 0.16) |

| Model 2c | 0.20 (0.05 to 0.34)d | 0.12 (0.01 to 0.24)d | 0.06 (−0.04 to 0.16) |

| Nonbothersome | |||

| Model 1b | 0.05 (0.00 to 0.09)d | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.06) | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.09)d |

| Model 2c | 0.04 (−0.00 to 0.09) | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) | 0.06 0.03 to 0.09)d |

| Hearing loss, ≥25 dB HL (n = 1742) | |||

| No tinnitus | |||

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Bothersome | |||

| Model 1b | 0.23 (0.12 to 0.34)d | 0.19 (0.09 to 0.28)d | 0.12 (0.03 to 0.21)d |

| Model 2c | 0.22 (0.11 to 0.33)d | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.28)d | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.21)d |

| Nonbothersome | |||

| Model 1b | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.13)d | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.11)d | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.08)d |

| Model 2c | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.13)d | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.11)d | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.08)d |

Abbreviation: dB HL, decibel hearing level.

Difference represents the difference in the log-transformed score (raw score +1) of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression scale, the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, or the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in participants with nonbothersome or bothersome tinnitus, stratified by hearing loss.

Adjusted for sex and age.

Further adjusted for highest achieved educational level, hearing loss, body mass index, alcohol use, and smoking status.

Significant estimates (P < .05).

Information on tinnitus impairment was available for 625 participants with daily tinnitus. Of those, 88 participants (14.1%) reported relevant tinnitus impairment. Participants with relevant tinnitus impairment had higher scores on all 3 mental health outcomes compared with participants with daily tinnitus but no tinnitus impairment (Table 4; eTable 3 in the Supplement). Median scores on all 3 mental health outcomes were higher per more severe tinnitus impairment category (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Table 4. Associations Between Participants With Daily Tinnitus and a Relevant Tinnitus Impairment (vs Daily Tinnitus and Low Tinnitus Impairment) and Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms, and Self-reported Sleep Qualitya.

| Tinnitus impairment | Difference (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | Sleep quality | |

| No relevant impairment | |||

| Model 1c | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Model 2d | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Relevant impairment | |||

| Model 1c | 0.22 (0.12-0.33)e | 0.15 (0.07-0.23)e | 0.12 (0.05-0.19)e |

| Model 2d | 0.21 (0.11-0.31)e | 0.15 (0.06-0.23)e | 0.12 (0.05-0.20)e |

For 662 participants with daily tinnitus, tinnitus impairment was assessed by the simplified Tinnitus Handicap Inventory, with a relevant impairment defined as a score of 16 or higher.

Difference represents the difference in the log-transformed score (raw score +1) of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression scale, the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, or the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in participants with tinnitus with or without interference with daily life.

Adjusted for sex and age.

Additionally adjusted for highest achieved educational level, hearing loss, body mass index, alcohol use, and smoking status.

Significant effect estimates (P < .05).

Associations of Tinnitus With Mental Health Over Time

Repeated data were available for 975 participants (mean [SD] age, 71.7 [4.5] years; 519 [53.2%] women), with a mean (SD) follow-up of 4.4 (0.2) years (range, 3.5-5.1 years). At baseline, no tinnitus was reported by 792 participants (81.2%), nonbothersome tinnitus by 163 participants (16.7%), and bothersome tinnitus by 20 participants (2.1%).

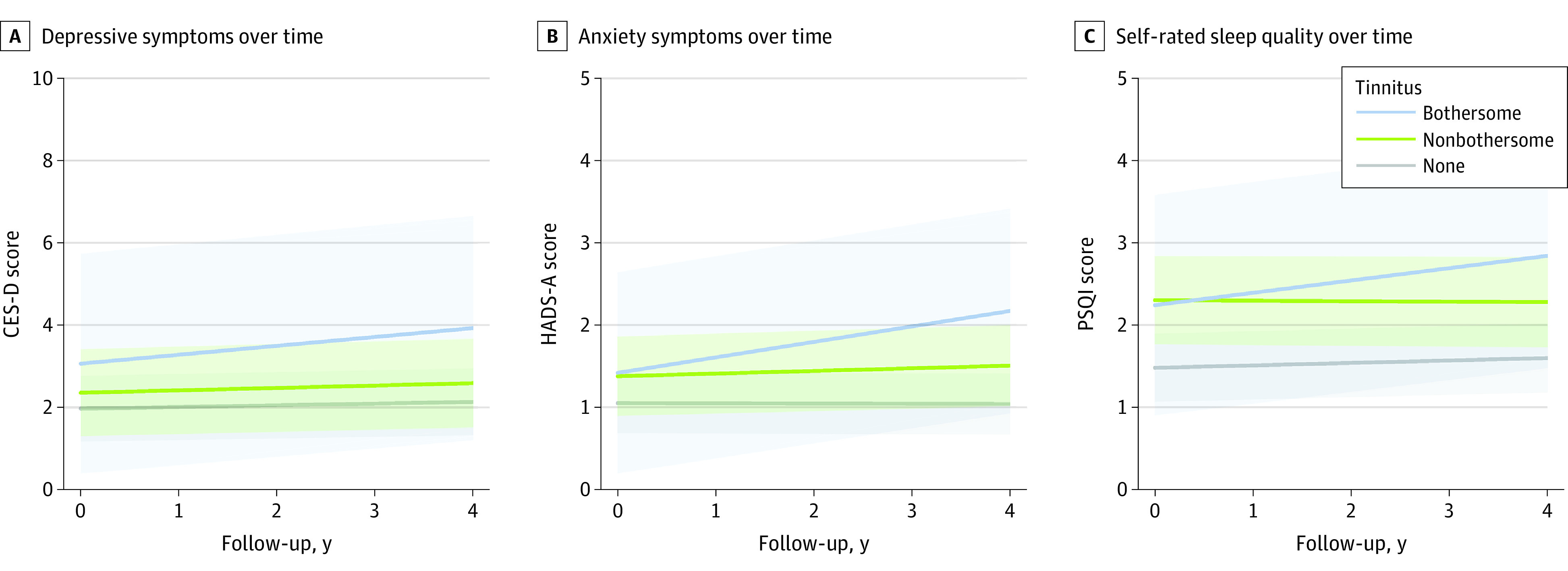

Participants with any tinnitus (ie, bothersome or nonbothersome) had higher scores on all 3 mental health outcomes compared with participants with no tinnitus (Figure; eFigure and eTable 5 in the Supplement). The change in mental health symptoms during follow-up was not significantly different for participants with tinnitus, nor was the change different for bothersome vs nonbothersome tinnitus, compared with participants without tinnitus.

Figure. Association Between Participants With Bothersome or Nonbothersome Tinnitus and Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms, and Self-reported Sleep Quality Over Time.

Results of linear mixed models showing the mean change in log values (raw score +1) over time for Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale scores (A), the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A) scores (B), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) self-reported sleep quality scores (C).

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed that both bothersome and nonbothersome tinnitus were associated with having more depressive and anxiety symptoms and poorer sleep quality in participants with vs without tinnitus, although associations were stronger in those indicating bothersome tinnitus. Associations were present in individuals with or without hearing loss. Furthermore, longitudinal analyses were suggestive (although not statistically significant) of more depressive and anxiety symptoms and poorer sleep quality after 4 years of follow-up in participants with bothersome tinnitus.

The association of tinnitus with psychopathology is in line with previous cross-sectional studies reporting tinnitus to be associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms and poorer sleep quality.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,35,36 We found that the effect size of the association for bothersome tinnitus over nonbothersome tinnitus was nearly 3 times as large for depressive and anxiety symptoms and twice as large for sleep quality compared with no tinnitus. However, the absolute values for the differences in effect size cannot be determined from the reported values because they represented a transformed value. Moreover, we found that the group with daily tinnitus and severe tinnitus impairment (high THI-s score) had a 2 to 4 times higher likelihood for psychopathology than the group with daily tinnitus and mild tinnitus impairment (low or moderate THI-s score). This outcome is in line with the results reported by Bhatt et al,11 who found even higher odds ratios but who compared participants with tinnitus vs those without tinnitus. Yet, the association between tinnitus and mental health outcomes was not detected only in a small group with severe tinnitus. We also observed a similar association in the subgroup of participants with nonbothersome tinnitus. Although the effect sizes were smaller than in the bothersome tinnitus group, the associations were consistently found for each of the 3 investigated mental health outcomes. Mental health problems can thus also be observed in milder manifestations of tinnitus. A plausible explanation for the consistent association between tinnitus and mental health outcomes, even for nonbothersome tinnitus, could be that people with tinnitus generally develop negative thoughts about their tinnitus, stress arousal, and hyperawareness.37 Those negative thoughts and hyperawareness have been suggested to be a mechanism for developing mental health problems.38,39 Yet, equally, it could be speculated that mental health problems lead to a negative focus that worsens the experience of tinnitus40 or that a tendency toward negative thoughts, stress, and hyperawareness may be a shared common cause. Further research is needed to determine the exact pathways.

Another potential explanation for the association of tinnitus with mental health problems is the presence of hearing loss because it is a strong risk factor for tinnitus16 and also because it is associated with mental health problems,18 depression in particular.41 However, we observed associations between tinnitus and mental health outcomes in both subgroups, that is, with or without hearing loss, suggesting that hearing loss is not a common cause that explains these associations in full. We unexpectedly found a higher likelihood for clinically relevant mental health problems with severe tinnitus for the subgroup without hearing loss. Even though it is counterintuitive that absence of hearing loss appeared to strengthen the association of tinnitus with more psychopathology, it may be that in individuals without hearing loss, different neural pathways are involved in tinnitus generation, and that these neural pathways in turn have a stronger association with mental health problems.42 In the presence of hearing loss, tinnitus pathophysiology is more likely to be initiated by hearing-related factors, whereas in the absence of hearing loss, it is thought that changes in the brain are responsible for the occurrence of tinnitus.17

Several other causal pathways have been posed to explain the association between tinnitus and mental health.11 To gain more insight in the directionality of the association between tinnitus and mental health problems, we used longitudinal analyses to explore how mental health problems evolve over time in the presence or absence of tinnitus. Our results shown in the Figure appeared to suggest an increase in anxiety symptoms and poorer sleep quality during a period of 4 years for patients owing to more severe tinnitus, albeit the associations did not reach statistical significance because of limited power. In addition, because we were able to study only the association of tinnitus with mental health, we cannot infer that the temporality of the association is solely from tinnitus to mental health and not the other way around. The association may also be bidirectional, with more severe tinnitus increasing mental health problems and mental health problems inducing greater concern about tinnitus. To our knowledge, there are no other longitudinal epidemiological studies devoted to exploring the association between tinnitus and mental health over time. Future population-based studies with repeated measurements over time are therefore urgently needed.

Strengths and Limitations

Major strengths of this study are the presence of both cross-sectional and longitudinal data in a relatively large population-based sample and the large number of confounding variables taken into account, including hearing loss. Several limitations of this study should be noted. As with all tinnitus research, a lack of a uniform definition of this subjective disorder hampers the ability to compare our results with other studies. Nevertheless, we asked a frequently used question to assess tinnitus.1 In addition, we investigated tinnitus severity both by asking an additional question and through the use of the THI-s. Regarding our longitudinal analyses, a follow-up time of 4 years may be too long to investigate an association between the presence of tinnitus and mental health outcomes. It would also be interesting to investigate the longitudinal association between mental health problems and incident tinnitus; however, tinnitus incidence was too low in the present study to provide these results. We believe that the results of this study extend current knowledge and are valuable because we not only investigated cross-sectional associations between tinnitus and mental health in relevant subgroups of a large population-based sample of middle-aged and elderly individuals but also explored possible associations over time.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we showed that tinnitus was strongly associated with having more depressive and anxiety symptoms and having poorer sleep quality, even when tinnitus did not interfere with daily life (nonbothersome tinnitus). Hearing loss did not appear to play a primary role in these associations. Moreover, any tinnitus at baseline was associated with an increase in anxiety symptoms and poorer sleep quality over time. These results underline the importance of increasing awareness of the association of tinnitus with mental health problems among affected individuals. Primary health care professionals should monitor mental health in patients with tinnitus, even in patients who do not report significant impairments to their daily life.

eTable 1. Association Between Participants With (Non-) Bothersome Tinnitus and Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality

eTable 2. Association Between Participants With (Non-) Bothersome Tinnitus and Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality, Stratified Analyses for Hearing Impairment

eTable 3. Association Between Participants With Daily Tinnitus and a Relevant Tinnitus Handicap (vs Daily Tinnitus and Low Tinnitus Handicap) and Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality

eTable 4. Association Between Participants With (Non-) Bothersome Tinnitus at Baseline and Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality Over Time

eTable 5. Association Between Participants With (Non-) Bothersome Tinnitus at Baseline and Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality Over Time

eFigure. Association Between Participants With Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality Over Time

References

- 1.McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Somerset S, Hall D. A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hear Res. 2016;337:70-79. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langguth B, Landgrebe M, Kleinjung T, Sand GP, Hajak G. Tinnitus and depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(7):489-500. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.575178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salazar JW, Meisel K, Smith ER, Quiggle A, McCoy DB, Amans MR. Depression in patients with tinnitus: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161(1):28-35. doi: 10.1177/0194599819835178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pattyn T, Van Den Eede F, Vanneste S, et al. Tinnitus and anxiety disorders: a review. Hear Res. 2016;333:255-265. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.House L, Bishop CE, Spankovich C, Su D, Valle K, Schweinfurth J. Tinnitus and its risk factors in African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(7):1668-1675. doi: 10.1002/lary.26964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nondahl DM, Cruickshanks KJ, Huang GH, et al. Tinnitus and its risk factors in the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(5):313-320. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2010.551220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seo JH, Kang JM, Hwang SH, Han KD, Joo YH. Relationship between tinnitus and suicidal behaviour in Korean men and women: a cross-sectional study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2016;41(3):222-227. doi: 10.1111/coa.12500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med. 2010;123(8):711-718. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stohler NA, Reinau D, Jick SS, Bodmer D, Meier CR. A study on the epidemiology of tinnitus in the United Kingdom. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:855-871. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S213136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Fortnum H, et al. Investigating the association between tinnitus severity and symptoms of depression and anxiety, while controlling for neuroticism, in a large middle-aged UK population. Int J Audiol. 2015;54(9):599-604. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1014577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatt JM, Bhattacharyya N, Lin HW. Relationships between tinnitus and the prevalence of anxiety and depression. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(2):466-469. doi: 10.1002/lary.26107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Rochtchina E, Karpa MJ, Mitchell P. Incidence, persistence, and progression of tinnitus symptoms in older adults: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear Hear. 2010;31(3):407-412. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181cdb2a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krog NH, Engdahl B, Tambs K. The association between tinnitus and mental health in a general population sample: results from the HUNT Study. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(3):289-298. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Izuhara K, Wada K, Nakamura K, et al. Association between tinnitus and sleep disorders in the general Japanese population. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2013;122(11):701-706. doi: 10.1177/000348941312201107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatt JM, Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence, severity, exposures, and treatment patterns of tinnitus in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142(10):959-965. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oosterloo BC, Croll PH, de Jong RJB, Ikram MK, Goedegebure A. Prevalence of tinnitus in an aging population and its relation to age and hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(4):859-868. doi: 10.1177/0194599820957296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haider HF, Bojić T, Ribeiro SF, Paço J, Hall DA, Szczepek AJ. Pathophysiology of subjective tinnitus: triggers and maintenance. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:866. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blazer DG. Hearing loss: the silent risk for psychiatric disorders in late life. Clin Geriatr Med. 2020;36(2):201-209. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomaa MA, Elmagd MH, Elbadry MM, Kader RM. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale in patients with tinnitus and hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271(8):2177-2184. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2715-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landry EC, Sandoval XCR, Simeone CN, Tidball G, Lea J, Westerberg BD. Systematic review and network meta-analysis of cognitive and/or behavioral therapies (CBT) for tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2020;41(2):153-166. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rademaker MM, Stegeman I, Ho-Kang-You KE, Stokroos RJ, Smit AL. The effect of mindfulness-based interventions on tinnitus distress. a systematic review. Front Neurol. 2019;10:1135. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cima RFF, Mazurek B, Haider H, et al. A multidisciplinary European guideline for tinnitus: diagnostics, assessment, and treatment. Article in German. HNO. 2019;67(suppl 1):10-42. doi: 10.1007/s00106-019-0633-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikram MA, Brusselle G, Ghanbari M, et al. Objectives, design and main findings until 2020 from the Rotterdam Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(5):483-517. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00640-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Netherlands National Trial Register . Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.trialregister.nl

- 25.World Health Organization . International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform/the-ictrp-search-portal

- 26.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman CW, Sandridge SA, Bolek L. Development and psychometric adequacy of the screening version of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29(3):276-281. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31816569c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychological Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beekman ATF, van Limbeek J, Deeg DJ, Wouters L, van Tilburg W. [A screening tool for depression in the elderly in the general population: the usefulness of Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)]. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 1994;25(3):95-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193-213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.UNESCO Institute for Statistics . International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Published 2011. Accessed April 27, 2021. http://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced

- 33.World Health Organization . Deafness and hearing loss. Updated 2021. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.who.int/health-topics/hearing-loss#tab=tab_1

- 34.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teixeira LS, Granjeiro RC, Oliveira CAP, Bahamad Júnior F. Polysomnography applied to patients with tinnitus: a review. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;22(2):177-180. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loprinzi PD, Maskalick S, Brown K, Gilham B. Association between depression and tinnitus in a nationally representative sample of US older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(6):714-717. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.775640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eysenck MW, Fajkowska M. Anxiety and depression: toward overlapping and distinctive features. Cogn Emot. 2018;32(7):1391-1400. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2017.1330255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(8):869-893. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00061-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKenna L, Handscomb L, Hoare DJ, Hall DA. A scientific cognitive-behavioral model of tinnitus: novel conceptualizations of tinnitus distress. Front Neurol. 2014;5:196. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Natalini E, Fioretti A, Riedl D, Moschen R, Eibenstein A. Tinnitus and metacognitive beliefs-results of a cross-sectional observational study. Brain Sci. 2020;11(1):E3. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11010003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blazer DG, Tucci DL. Hearing loss and psychiatric disorders: a review. Psychol Med. 2019;49(6):891-897. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718003409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sedley W. Tinnitus: does gain explain? Neuroscience. 2019;407:213-228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Association Between Participants With (Non-) Bothersome Tinnitus and Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality

eTable 2. Association Between Participants With (Non-) Bothersome Tinnitus and Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality, Stratified Analyses for Hearing Impairment

eTable 3. Association Between Participants With Daily Tinnitus and a Relevant Tinnitus Handicap (vs Daily Tinnitus and Low Tinnitus Handicap) and Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality

eTable 4. Association Between Participants With (Non-) Bothersome Tinnitus at Baseline and Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality Over Time

eTable 5. Association Between Participants With (Non-) Bothersome Tinnitus at Baseline and Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality Over Time

eFigure. Association Between Participants With Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Self-Reported Sleep Quality Over Time