Abstract

This cross-sectional survey study evaluates the specific concerns of and high hesitancy rate toward COVID-19 vaccination among women with breast cancer in Mexico.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a substantial effect on cancer care.1 The recent widespread availability of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 is a promising strategy to prevent COVID-19–associated mortality. However, previous reports have shown a high hesitancy rate to receive a COVID-19 vaccine among oncologic patients.2,3 Because breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignant neoplasm,4 it is imperative to evaluate the specific concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccination among patients with this disease.

Methods

From March 12 to March 26, 2021, any woman with breast cancer residing in Mexico who visited the social media channels of nongovernmental organizations dedicated to improving breast cancer care were invited to complete a web-based survey. To assess COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy rates, participants were dichotomized into a vaccine-acceptant group (ie, willing to be vaccinated immediately) and a vaccine-hesitant group (ie, prefer to wait, only if vaccine is mandatory, or refuse). Respondents who previously had been vaccinated against COVID-19 were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Data analyses were performed using SPSS, version 27 (IBM Inc). Significance was defined as 2-tailed P < .05. The Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of the Instituto Tecnologico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey approved the study. Informed consent was waived because the research was deemed to be of minimal risk and no identifiable data were collected.

Results

In all, 619 women with breast cancer residing in Mexico who visited the social media channels dedicated to improving breast cancer care responded to the survey; of these, 79 (13%) were excluded for prior COVID-19 vaccination. The remaining 540 women (median [range], 49 [23-85] years) were included. Of these 540 participants, 357 (66%) were willing to be vaccinated immediately and 183 (34%) were hesitant to be vaccinated—142 (26%) would wait to see the vaccine’s adverse effects in others, 23 (4%) would only be vaccinated if it became mandatory, and 18 (3%) would refuse to be vaccinated.

The most common reasons motivating vaccine-acceptant patients were: to prevent COVID-19 (n = 301; 84%), to take care of their relatives (n = 227; 64%), an autoperceived social responsibility (n = 227; 64%), a fear of getting seriously ill (n = 217; 61%), and/or a desire for “getting back to normal” (n = 186; 52%). The reasons motivating vaccine hesitancy and the factors that might influence hesitant patients to accept immunization are shown in the Table. Regarding misconceptions, participants believed that the COVID-19 vaccines may contain a virus capable of causing infection (n = 115; 21%), are contraindicated in patients with breast cancer (n = 29; 5%), are not effective (n = 19; 4%), carry a computer chip to surveil the population (n = 10; 2%), and/or could cause infertility (n = 6; 1%).

Table. Concerns and Motivations Regarding COVID-19 Vaccination Among Patients With Breast Cancer.

| Concerns and motivations | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptant group (n = 357) | Hesitant group (n = 183) | |

| What concerns make you not want to receive a COVID-19 vaccine? | ||

| Fear of adverse reactions | 39 (10.9) | 100 (54.6) |

| Distrust of the health care system | 10 (2.8) | 37 (20.2) |

| Belief that vaccination is not indicated for patients with breast cancer | 6 (1.7) | 23 (12.6) |

| Treating physician has not recommended it | 8 (2.2) | 18 (9.8) |

| Belief that vaccination is not effective | 2 (0.6) | 17 (9.3) |

| Belief that vaccination can cause COVID-19 | 2 (0.6) | 14 (7.7) |

| Belief that vaccine is not necessary because I already had COVID-19 | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.6) |

| What would motivate you to be vaccinated against COVID-19? | ||

| Vaccination being recommended by my oncologist | 127 (35.6) | 118 (64.5) |

| More information about its effectiveness | 66 (18.5) | 85 (46.4) |

| More information about its safety | 69 (19.3) | 78 (42.6) |

| If someone close to me receives it and does not experience adverse reactions | 29 (8.1) | 61 (33.3) |

| Vaccination being recommended by my primary care physician | 35 (9.8) | 32 (17.5) |

| Vaccination becoming mandatory | 10 (2.8) | 16 (8.7) |

| Endorsement of vaccination by national authorities | 17 (4.8) | 6 (3.3) |

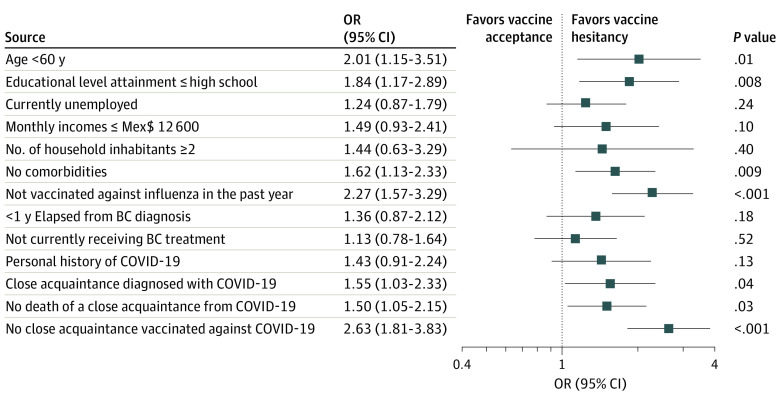

Univariate analyses showed that factors associated with vaccine hesitancy include mistrust in the health care system (odds ratio [OR], 8.79; 95% CI, 4.26-18.15), misconception that COVID-19 vaccination is contraindicated in patients with breast cancer (OR, 8.41; 95% CI, 3.36-21.05), not having a close acquaintance already vaccinated against COVID-19 (OR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.81-3.83), noncompliance with prior influenza immunization (OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.57-3.29), age younger than 60 years (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.15-3.51), low educational attainment (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.17-2.89), and not having a close acquaintance deceased from COVID-19 (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.05-2.15) (Figure). Significant variables were included in a multivariate model and remained independent predictors of vaccine hesitancy, except for being less than 60 years of age (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 0.87-3.50; P = .12) and not having a close acquaintance who died of COVID-19 (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.89-2.29; P = .14). In comparison with the vaccine-acceptant group, hesitant patients were more likely to state that having a close acquaintance who did not experience a vaccine-related adverse reaction (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 3.47-9.22), having more information about vaccine effectiveness (OR, 3.82; 95% CI, 2.58-5.68) and safety (OR, 3.10; 95% CI, 2.09-4.60), mandatory vaccination (OR, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.48-7.48), and being recommended by their oncologist to be vaccinated (OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 2.27-4.77) were needed to motivate them to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.

Figure. Univariate Logistic Regression Analysis to Identify Factors Associated With COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Patients With Breast Cancer.

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; Mex$, Mexican peso.

Boxes indicate odds ratios; whiskers show 95% CIs.

Discussion

The suboptimal acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine is a reason for concern,5 especially among individuals with a higher risk of severe illness. Strategies that focus on building vaccine literacy and confidence in the health care system are urgently needed to enhance vaccine acceptance. To achieve this, clear and credible communication that addresses patient misinformation and specific concerns must be encouraged.5 Moreover, the active participation of oncologists is essential to educate cancer patients on the benefits of COVID-19 immunization and to endorse vaccination.

Some limitations of this study include its cross-sectional nature, reliance on self-reported data, limited sample size, and lack of formal survey sampling. However, this study provides much needed data to elucidate the factors associated with vaccine hesitancy in patients with breast cancer.

Immunization remains the leading strategy for reducing the COVID-19 burden. Interventions directed toward raising awareness of the benefits of vaccination, especially among the most vulnerable, are a priority for increasing the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines.

References

- 1.Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, et al. ; International Research Network on COVID-19 Impact on Cancer Care . Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care: a global collaborative study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1428-1438. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutch Federation of Cancer Organizations . Kankerzorg in de anderhalvemeter-samenleving, wat is jouw ervaring? Accessed April 5, 2021. https://nfk.nl/nieuws/kankerzorg-in-de-anderhalvemeter-samenleving-wat-is-jouw-ervaring

- 3.Barrière J, Gal J, Hoch B, et al. Acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among French patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):673-674. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. Published online February 4, 2021. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225-228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]