Abstract

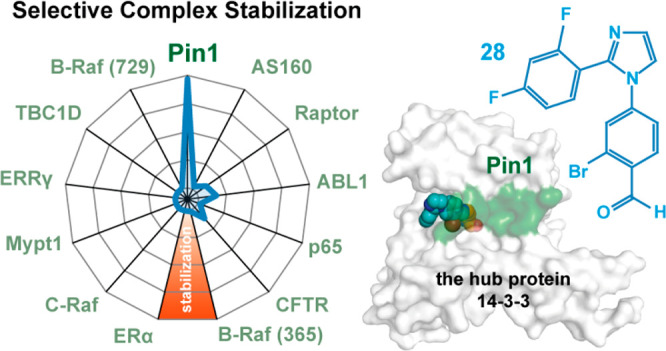

The stabilization of protein complexes has emerged as a promising modality, expanding the number of entry points for novel therapeutic intervention. Targeting proteins that mediate protein–protein interactions (PPIs), such as hub proteins, is equally challenging and rewarding as they offer an intervention platform for a variety of diseases, due to their large interactome. 14-3-3 hub proteins bind phosphorylated motifs of their interaction partners in a conserved binding channel. The 14-3-3 PPI interface is consequently only diversified by its different interaction partners. Therefore, it is essential to consider, additionally to the potency, also the selectivity of stabilizer molecules. Targeting a lysine residue at the interface of the composite 14-3-3 complex, which can be targeted explicitly via aldimine-forming fragments, we studied the de novo design of PPI stabilizers under consideration of potential selectivity. By applying cooperativity analysis of ternary complex formation, we developed a reversible covalent molecular glue for the 14-3-3/Pin1 interaction. This small fragment led to a more than 250-fold stabilization of the 14-3-3/Pin1 interaction by selective interfacing with a unique tryptophan in Pin1. This study illustrates how cooperative complex formation drives selective PPI stabilization. Further, it highlights how specific interactions within a hub proteins interactome can be stabilized over other interactions with a common binding motif.

Introduction

The emergence of small-molecule modulation of protein–protein interactions (PPIs) has vastly expanded the druggable proteome for therapeutic intervention.1 In combination with the rise of fragment-based drug discovery as an established approach for drug design,2−6 the development of PPI inhibitors has rapidly matured.7,8 The orthogonal approach of PPI stabilization has also emerged as a promising therapeutic approach,9,10 illustrated by the development of cooperative proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), such as lenalidomide.11−13 Given that proteins typically engage in multiple protein interactions, via a common interface, it is essential when developing small-molecule PPI modulators to consider selectivity. This is of particular relevance in the field of PPI stabilizers as illustrated with the development of a cooperative PROTAC, AT1,14 inducing non-native PPIs and IMiD research which has expanded to a range of protein targets.15

Covalent tethering approaches are a valuable tool for drug discovery,16−18 particularly for targeting challenging drug targets, such as K-Ras.19 One of the most compelling applications of covalent tethering is the ability to detect weakly binding hit fragments, a result of out of equilibrium bond formation between the fragment and the protein.2,20−22 Such site-directed fragment identification has broad applications to PPI stabilization, as we have shown previously using a disulfide tethering approach for hub protein 14-3-3 in complex with estrogen receptor α (ERα)23 and estrogen related receptor γ (ERRγ).24 Further, we have also shown the application of dynamic covalent imine tethering for the stabilization of the 14-3-3/NF-κB complex.25

Stabilization of hub proteins with partner proteins, for instance 14-3-3 with any of its multiple cellular interaction partners,26 including c-Myc,27 p53,28 Raf kinases,29,30 p65,31 and CFTR,32 has promising therapeutic potential for the treatment of numerous diseases including cancer and neurological diseases. The extensive 14-3-3 interactome presents an excellent platform for investigating the development of PPI stabilizers. However, this interactome comes with a significant challenge for developing chemical probes that are selective for a specific interaction. 14-3-3 modulates cellular function by binding phosphorylated partner proteins via a conserved binding groove that recognizes a phosphorylated serine or threonine.33 The highly conserved nature of the 14-3-3 binding groove calls for diverse approaches to develop selective chemical probes that stabilize specific 14-3-3 complexes. We have previously shown that chemical probes that target 14-3-3 proteins have generalized selectivity for extended, bent, and truncated partner proteins.34 However, the level of promiscuity of such stabilizers toward partner proteins sharing a common binding epitope remains to be addressed.

We selected the interaction between 14-3-3 and the peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (Pin1) protein, which is closely involved in many disease states, as a relevant case study. The formation of the 14-3-3/Pin1/Myc complex is reported to drive the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of oncogenic Myc.27,35

Here, we show that the unique topologies and functionalities of various binding interfaces shaped by the complexes of 14-3-3 will direct specific molecular fragments that selectively stabilize a specific 14-3-3 PPI (Figure 1A). Utilizing an imine-tethering approach,34 we demonstrate how selectivity can be engineered in the early stages of the drug discovery process. We exploit a privileged anchor point of Lys122 that lies at the interface of the composite binding pocket formed by the protein complex (Figure 1B,C). This binding pocket is situated adjacent to the phospho-accepting pocket. Fragment binding is only compatible with bent partner protein epitopes. Further selectivity is driven by templating effects of the amino acid in the plus one position relative to the phosphorylated residue of the interaction partner.

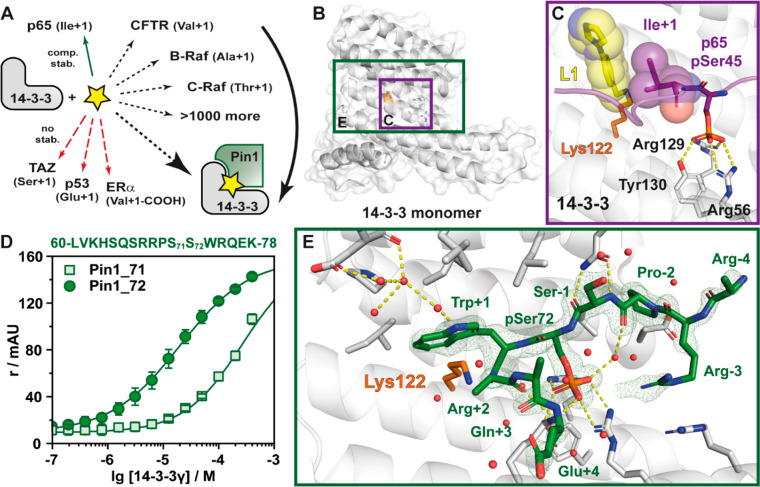

Figure 1.

Imine-based tethering for selective targeting of the Pin1/14-3-3 interaction. (A) Schematic representation of selective small molecule (yellow star) stabilization of the Pin1/14-3-3 complex formation and the effect on other 14-3-3 mediated PPI interactions. Previous studies identified complex stabilization (comp. stab.) of the p65/14-3-3 interaction by imine-forming fragments. The 14-3-3 complex with TAZ, p53, or ERα was not affected by those fragments (no stab.).34 (B) Crystal structure of a 14-3-3σ monomer (cartoon representation with transparent surface; PDB code 7AOG; for clarity the Pin1 partner peptide is hidden). Highlighted is Lys122 (orange sticks) and the phospho-accepting pocket (white sticks). The purple box indicates the region depicted in panel C. The green box indicates the region depicted in panel E. (C) Crystal structure of 4-imidazole-benzaldehyde (fragment L1, yellow sticks) binding to the interface of the p65-derived peptide (pS45) (purple sticks) and 14-3-3σ (white cartoon and sticks) complex revealed imine bond formation of L1 with Lys122 of 14-3-3σ (orange sticks) and L1 makes hydrophobic contacts with Ile+1 of p65 (hydrophobic contacts indicated by transparent spheres) (PDB code 6YP2).34 (D) Fluorescence anisotropy (r in mAU) depicting the binding of phosphorylated Pin1-peptides to 14-3-3γ. Shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). (E) Cocrystal structure of Pin1 (phosphorylated S72, green sticks) in complex with 14-3-3σ (cartoon and stick representation). The 2Fo – Fc electron density map (green mesh) is contoured at 1σ. Polar interactions are shown with yellow dashes (PDB code 7AOG).

Results and Discussion

Elucidation of 14-3-3/Pin1 Interaction

Previously, we have reported the development of an aldehyde fragment screening approach, which targeted the p65/14-3-3σ PPI.34 This site-directed fragment screening approach forms an aldimine bond between the aldehyde fragment and Lys122 of 14-3-3σ. Lysine presents an attractive anchoring point for covalent drug discovery owing to the large representation of lysine in the proteome.36−38 Lys122 is located within the binding groove of 14-3-3, adjacent to the p65/14-3-3 interface (Figure 1B,C).39 This privileged location of imine bond formation offers the unique opportunity to evaluate the efficacy and selectivity of aldehydes stabilizing complex formation with the hub protein 14-3-3.

Research by Wen et al. has suggested that 14-3-3 binds the Pin1 protein in a disordered loop region (Val6 −Thr81).35 Screening of the protein sequence with a 14-3-3 prediction server40 further supported the proposed binding site being within the loop region of Pin1. Amino acids Ser71 and Ser72 were identified as potential 14-3-3 recognition sites. Computational screening predicted that the pSer72 site was the more likely binding motif (Table S1). Considering the proximity of the two amino acids in the binding motif, we tested both phosphorylation sites. We screened 17-mer phosphopeptides representing the loop region of Pin1 whereby either Ser71 or Ser72 was phosphorylated. The elucidation of binding affinities was done using a fluorescence anisotropy (FA) assay with 14-3-3γ. The pSer72 (Pin1_72) peptide elicited a KD of 22.2 ± 1.20 μM (Figure 1D). In contrast, a KD of ∼270 μM was observed for the pSer71 peptide. Next, the Pin1_72 peptide was crystallized in complex with 14-3-3σ at 1.5 Å resolution (Table S2). Notably, we were unable to crystallize the pSer71 site. Analysis of the complex showed that Pin1_72 occupied two-thirds of the amphiphilic phospho-binding groove of 14-3-3 (Figure 1E). Of particular interest was the orientation of Trp73 of Pin1_72 due to its hydrophobic interactions with the 14-3-3 surface. Further, the C-terminus of the peptide veers out of the binding groove, generating a composite pocket for small molecule binding.

Site-Directed Aldimine Fragment Screening

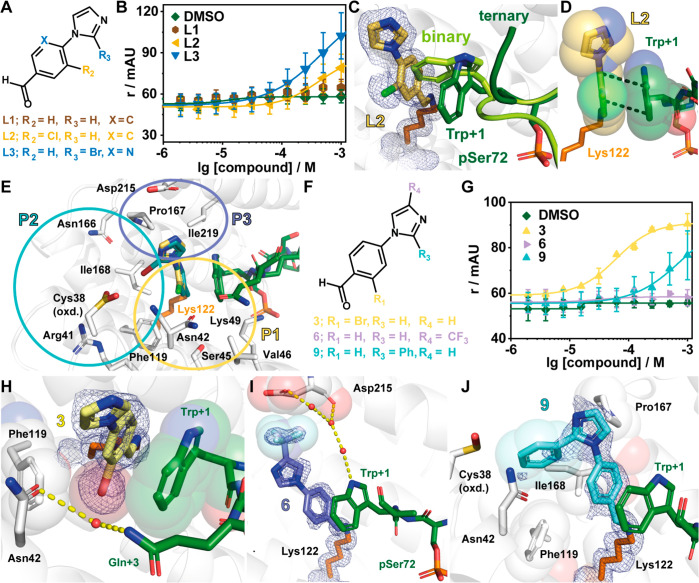

Given the solvent exposure of Lys122 of 14-3-3 in the complex with Pin1_72, we selected 42 covalent fragments from an in-house aldehyde fragment library for fragment screening with the Pin1_72/14-3-3γ complex using a FA assay.34 Critical to this selection was the knowledge that several fragments bound in the p65/14-3-3σ complex, observed by X-ray,34 but did not elicit a stabilizing effect in FA assays, herein termed silent binders. Fragments were screened by titration to a fixed concentration of 14-3-3γ (10 μM) and Pin1_72 (50 nM). As a measure of activity, the inflection point of the curve was determined, representing the half-maximum ternary complex formation (CC50), where the ternary complex consists of the 14-3-3 protein, Pin1_72 peptide, and a ligand. From the fragment screen, 11 compounds were found to stabilize the Pin1_72/14-3-3γ complex (Figure S1). Of these fragments, L2 and L3 were shown to exhibit significant complex formation, albeit that a lack of upper plateau limited accurate assignment of the CC50 values (Figure 2A,B, Table 1). Notably, fragment L1, which did not contain a halogen, was not active (Figure 2B). Inquisitive regarding the binding of L1, we also soaked this fragment with the 14-3-3σΔC/Pin1_72 complex. X-ray crystal structures of L1, L2, and L3 in complex with 14-3-3σΔC/Pin1_72 confirmed that all fragments formed a covalent imine bond with Lys122 (Figure 2C,D, Figure S2). The binding of L1–L3 induced a conformational change in Pin1_72 when compared with the binary complex (Figure 2C), where the binary complex is defined as the 14-3-3 protein in complex with the interacting Pin1_72 peptide. Specifically, Trp73 of Pin1, herein denoted Trp+1, describing its position relative to pSer72, was flipped ∼90° forming a π–π interaction with the fragment (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

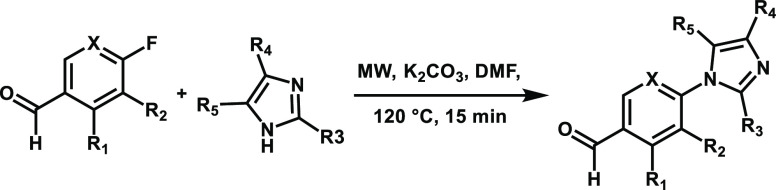

Imine-based tethering revealed L2 and L3 as promising starting points for the development of Pin1/14-3-3 stabilizers. (A) Chemical structures of L1, L2, and L3. (B) Fluorescence anisotropy (r in mAU) assay of fragments L1–L3 where the compound was titrated to 10 μM 14-3-3γ and 50 nM fluorescently labeled Pin1. Shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). (C) Ternary structure of 14-3-3/Pin1_72/L2 complex (PDB code 7AXN) overlaid with the binary structure of 14-3-3/Pin1_72 (PDB code 7AOG). Shown is the rearrangement of Trp+1 of Pin1 (binary, light green; ternary, dark green) upon binding of L2 (yellow sticks). 2Fo – Fc electron density map (blue mesh) is contoured at 1σ. (D) The benzaldehyde core of L2 (yellow sticks) forms π–π stacks with the indole moiety of Trp+1 of Pin1 (green sticks). (E) Overlay of L2 and L3 showing three pockets that can be probed during fragment optimization (PDB codes 7AXN and 7AYF). (F) Chemical structures of 3, 6, and 9. (G) Compounds were titrated to 10 μM 14-3-3γ and 50 nM Pin1_72 in FA (r, mAU). Shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). (H–J) Crystal structures of 3 (PDB code 7NIG), 6 (PDB code 7NJ6), and 9 (PDB code 7NJA) bound to 14-3-3σ in complex with Pin1_72. Shown are hydrogen bonds (yellow dashes) and potential hydrophobic contacts (indicated by sphere representation) between 3 (H), 6 (I), and 9 (J) and 14-3-3σΔC (white cartoon and sticks). The 2Fo – Fc electron density map (blue mesh) is contoured at 1σ.

Table 1. Focused Library Investigating Potency and Stabilization Factors for the Pin1/14-3-3 Interaction.

| compd | R1 | R2 | R3 | R3 | R4 | Xa | CC50 (μM)b | apparent KD (μM)b | SFc | PDB coded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 22 ± 1e | 7AOG | ||||||||

| L1 | H | H | H | H | H | C | >1000 | 7NIF | ||

| L2 | H | Cl | H | H | H | C | 423 ± 130f | 18 ± 1 | 1.3 | 7AXN |

| L3a | H | H | Br | H | H | N | 480 ± 74f | 9 ± 5 | 2.4 | 7AYF |

| 1 | H | Br | H | H | H | >1000 | nd | |||

| 2 | Cl | H | H | H | H | 153 ± 42 | 8 ± 7 | 2.6 | nd | |

| 3 | Br | H | H | H | H | 61 ± 7 | 6 ± 1 | 3.5 | 7NIG | |

| 4 | H | H | H | Me | H | >1000 | 7NRK | |||

| 5 | H | H | H | H | Me | >1000 | nd | |||

| 6 | H | H | H | CF3 | H | >1000 | 7NJ6 | |||

| 7 | H | H | H | benzyl | >1000 | 7NJ8 | ||||

| 8 | H | H | COOH | H | H | >1000 | nd | |||

| 9 | H | H | phenyl | H | H | >500 | 7NJA | |||

| 10 | Cl | H | phenyl | H | H | 166 ± 31 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 3.6 | 7BDP | |

| 11 | H | Cl | phenyl | H | H | >500 | nd | |||

| 12 | H | Br | phenyl | H | H | >500 | nd | |||

| 13 | Br | H | phenyl | H | H | 101 ± 6 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 10.8 | 7BDT | |

| 14 | CF3 | H | phenyl | H | H | 306 ± 42 | 9 ± 2 | 1.2 | 7AZ1 | |

| 15 | H | CF3 | phenyl | H | H | >500 | 7AZ2 | |||

| 16 | OMe | H | phenyl | H | H | g | 7BGQ | |||

| 17 | H | OMe | phenyl | H | H | g | 7BGV | |||

| 18 | Me | H | phenyl | H | H | g | 7BGR | |||

| 19 | OH | H | phenyl | H | H | 19 ± 15 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 4.9 | 7NRL | |

| 20 | OCF3 | H | phenyl | H | H | >500 | n. bind. | |||

| 21 | OPh | H | phenyl | H | H | g | n. bind. | |||

| 22 | naphth | phenyl | H | H | g | 7BGW | ||||

| 23 | Br | H | 2-Br phenyl | H | H | 24 ± 3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 18.9 | 7BG3 | |

| 24 | Br | H | 4-Br phenyl | H | H | 106 ± 17 | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 3.3 | n. bind. | |

| 25 | Br | H | 4-OH phenyl | H | H | >500 | nd | |||

| 26 | Br | H | 3-pyridinyl | H | H | 92 ± 8 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 2.3 | nd | |

| 27 | Br | H | 2-F, 5-Br phenyl | H | H | 118 ± 7 | 0.78 ± 0.02 | 56.6 | 7BDY | |

| 28 | Br | H | 2,4-diF phenyl | H | H | 79 ± 3 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 96.8 | 7BFW |

X is only applicable to L1–L3. Fragments 1–28 contain a carbon atom in the 5 position of the aromatic ring.

Measurements were taken after overnight incubation and in the presence of 100 μM fragment. Values are given as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three separate experiments (n = 3).

Fold stabilization was measured based on the internal DMSO control and 100 μM fragment.

nd: not determined. n. bind.: no extra electron density due to compound binding.

Value is a representative measurement and not specifically the value used to calculate the stabilization factor (SF), which was dependent on the internal DMSO reference.

A lack of upper-plateau limits accurate determination of the fragments CC5o value.

Compound showed autofluorescence within the FP assay (Figure S3).

Fragment Extension and SAR Analysis

Having identified L2 and L3 as hit fragments for optimization, we sought to extend the fragments, with a focus on enhancing potency for the Pin1_72/14-3-3 complex. Three key subpockets were identified (P1, P2, and P3) as potential points for fragment extension (Figure 2E). A focused library was constructed utilizing a nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction, with substituted imidazoles or benzimidazole and substituted 4-fluorobenzaldehydes (Table 1). Initial library development focused on halogen substitution and shifting the position of the halogen to probe pocket P1. Further, we investigated the effect of substituted imidazoles to explore pockets P2 and P3. Analysis using the FA assay showed that an exchange of the chloride of L2 for bromine (1) resulted in a loss of activity. In contrast, 2-substituted chlorine (2) and bromine analogues (3) resulted in improved affinity to the complex, with CC50 of 153 ± 42 μM and 61 ± 7 μM, respectively (Table 1, Figure 2F,G). Decorations on the imidazole ring (4–9) did induce minor to no complex stabilization.

Analysis of X-ray crystal structures of these fragments provided valuable insight into their activity profile (Figure 2H–J, Figure S2, Table S3). All measured fragments, 1–9, bound to Lys122 and induced a similar shift of the Trp+1 residue of Pin1_72, forming a π–π stack between the indole side chain and the benzaldehyde ring of the fragment. Further, a shift of the halogen to the 2-position probes the P1 subpocket formed by residues Asn42, Val46, Phe119, and Lys122 of 14-3-3 (Figure 2E,H). Fragments 4, 5, and 7 probe the P3 pocked comprising Asp215, Leu218, Ile219, and Leu222 (Figure 2E,I, Figure S2). The occupancy of the electron density map for fragment 4 is low and prevents accurate positioning of the imidazole decorations. However, the trifluoro of 6 reaches Asp215 of 14-3-3 (Figure 2I) and the benzimidazole of 7 engages in hydrophobic contacts with Leu218 and Ile219 in the roof of 14-3-3 (Figure S2). Lastly, the installation of a carboxylic acid (8) or a phenyl ring in the 2-position of the imidazole ring (9) probed subpocket P2 formed by Ile168, Asn42, and Phe119 (Figure 2E,J, Figure S2).

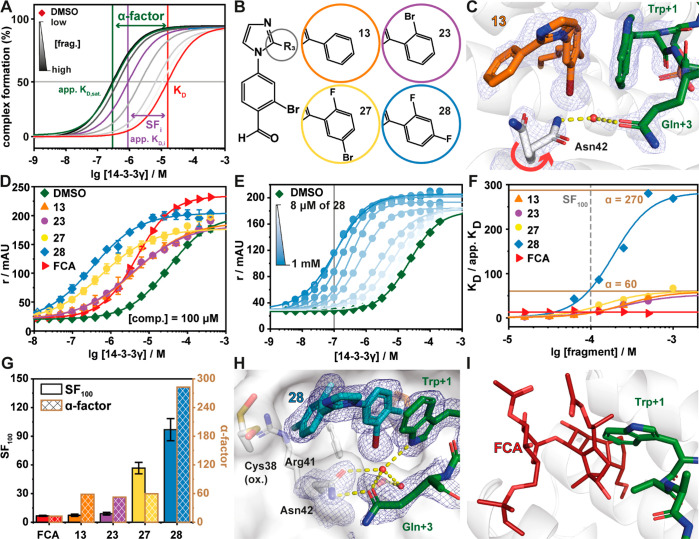

Inspired by the binding poses of 3 and 9, we combined their structural features to improve stabilization. Synthesis and screening of compounds 10–22 identified that a 2-bromo (13) or 2-hydroxy (19) substituted phenylimidazole provided CC50 values of 101 ± 6 and 19 ± 15 μM, respectively (Table 1, Figure S2B, Table S3). The CC50 values were further complemented by protein titration assays in the presence of a constant concentration of compound (100 μM). In the case of complex stabilization, a left shift of apparent KD values is observed, here described as stabilization factor (SF) (Figure 3A). Protein titration assay showed that fragment 13 (apparent KD = 2.16 ± 0.123 μM, SF = 10.8) elicited improved stabilization of the ternary complex formation relative to 19 (apparent KD = 3.92 ± 0.247 μM, SF = 4.9).

Figure 3.

Fragment 28 is the most potent stabilizer of the Pin1_72/14-3-3 complex. (A) Schematic representation of the difference between dissociation constant of the binary complex (KD, red line), concentration specific stabilization of the ternary complex (SFi, purple line), and α-factor of the ternary complex (dark green line). Gray lines directly relate to panel E, where the apparent KD at a specific concentration of fragment is represented (light to dark gray indicates fragment concentration as per the legend). The stabilization factor shows the shift in the apparent KD relative to the binary complex at a set concentration of compound. The α-factor is a measure of the maximum stabilizing response at saturation of the compound and measures the maximal cooperativity of the ternary complex. This schematic illustrates the limitation of only using a stabilization factor as different compounds have differing cooperativity with the complex. (B) Chemical structures of 13, 23, 27, and 28. (C) Crystal structure of the 13/Pin1_72/14-3-3σΔC complex (PDB code 7BDT). Hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dashes, and the electron density map is shown as a blue mesh (contoured at 1σ). (D) FA protein titrations in the presence of 100 μM fragment as indicated or DMSO control (n = 3). (E) 2D protein titrations in the presence of increasing concentrations of 28 (n = 1). (F) Ratio of KD/apparent KD plotted against the fragment concentrations. The data are derived from 2D titrations (see panel E and Figure S5). The saturation of the ratio represents the α-factor. (G) Comparison of stabilization factors in the presence of 100 μM compound (SF100) and the α-factor. (H) Crystal structure of the 28/Pin1_72/14-3-3σΔC complex (PDB code 7BFW). Hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dashes, and the electron density map is shown as a blue mesh (contoured at 1σ). (I) Overlay of FCA (PDB code 4JDD; ERα-peptide and 14-3-3σ hidden for clarity) and the Pin1_72/14-3-3 complex shows a steric clash of Trp+1 of Pin1_72 and FCA.

Analysis of the ternary crystal structure showed that 13 bound in a similar conformation to fragments 3 and 9 (Figure 3B,C). Interestingly, a conformational change is observed in Asn42 of 14-3-3 and the C-terminus of Pin1_72. This induces a water-mediated hydrogen bond interaction between Gln+3 of Pin1_72 and Asn42. This conformational change is highly advantageous as this enhances the polar contact between Pin1 and 14-3-3. Inspection of the electron density of 13 suggested that its 2-phenyl freely rotated. Further, Asn42 of 14-3-3 occupied two different conformations indicating either a low occupancy of the fragment or high conformational freedom. We therefore investigated the introduction of bulky side groups and/or hydrogen bonding groups to the 2-phenylimidazole to impair free rotation (23–28, Table 1, Figure S2, Table S3). The introduction of a hydrogen bonding group proved to have limited effect (25 and 26) with 26 only showing weak stabilization (SF = 2.3). Increasing the bulk of the 2-phenyl ring proved highly effective in improving potency and stabilization with 2-bromo (23), 2-fluoro-5-bromo (27), and 2,4-difluoro (28) eliciting CC50 values of 24 ± 3, 118 ± 7, and 79 ± 3 μM, respectively. To place this in context, the natural product fusicoccin A (FCA) binds to the 14-3-3σ/ERα complex with CC50 = 0.22 μM.23 Further, 23, 27, and 28 showed a significant shift in apparent KD ranging from low to submicromolar activity (1.15–0.27 μM) (Figure 3D). This translated to SFs ranging from 13- to 97-fold stabilization (Figure 3G).

A thermal shift assay was used as an orthogonal method to validate fragment induced 14-3-3/Pin1 complex stabilization (Figure S4). Initially, we investigated the effect of the addition of acetylated Pin1 peptide at 5 and 50 equiv on 14-3-3γ melting temperature. The addition of 5 equivalents of Pin1 showed no significant increase in melting temperature, while, 50 equiv resulted in an ∼1 °C increase in melting temperature. The addition of 27 or 28 to 14-3-3γ alone elicited no significant effect on 14-3-3 melting temperature, indicating weak to absent binding of the fragment to 14-3-3 alone. Notably, the addition of 27 or 28 to the complex of 14-3-3/Pin1, in the presence of 5 eq of Pin1, resulted in a 1.1 and 2.1 °C increase in melting temperature, respectively. The increase of melting temperature observed with the 14-3-3/Pin1/27 complex or with the treatment of 50 equiv of Pin1 shows how complex stabilization can significantly enhance 14-3-3 complex avidity. These results show how cooperativity between the three interaction partners leads to increased complex stability.

To benchmark the activity of fragment 28, we also screened the known 14-3-3 stabilizer fusicoccin A (FCA) against Pin1. FCA preferentially stabilizes 14-3-3 interaction partners with C-terminal phosphorylation sites (pSer/pThr-X-COOH, X = hydrophobic residue), like those present in the estrogen receptor α (ERα). Protein titrations with FCA afforded an apparent KD of 3.32 ± 0.251 μM, an order of magnitude less potent than 28 (Figure 3D).

Cooperativity in Ternary Complex Formation

In contrast to PPI inhibition, where affinity to one of the protein pockets is the driving force for drug development, the design of molecular glues is driven by cooperative ternary complex formation. Both CC50 and SF values are concentration dependent values and might differ based on assay design. Hence, we were aiming to determine the cooperativity factor (α) as a concentration independent measure of cooperativity.39,41,42 Cooperative complex formation is often accompanied by structural changes to the interface of a complex which translates to increased stability of the ternary complex.41,43 To assess cooperativity of the ternary complex, fragments 13, 23, 27, and 28 were selected for cooperativity analysis. The α-factor of the fragments were determined using 14-3-3 titrations in the presence of a varied but constant concentration of fragment in a dose-dependent manner. The α-factor also describes the SF of a saturated system, where higher compound concentrations do not further decrease the apparent KD. Further, the interval of change in stabilization describes the system’s cooperative behavior (Figure 3A).

Cooperativity analysis of 13 showed that the compound induced an order of magnitude decrease of the apparent KD of the 14-3-3/Pin_72 complex at 250 μM (Figure S5). However, at higher concentration regimes significant assay interference was observed, probably due to compound aggregation. Fragments 23, 27, and 28 all reached saturation or approached saturation enabling accurate determination of the α-factor. The largest cooperativity value was observed for 28, with 2 orders of magnitude increase in Pin1 stabilization (Figure 3E,F). Fragments 13, 23, and 27 showed α-factors of approximately 60 (Figure 3F). Notably, 27 reached saturation at a significantly lower concentration, compared to 23, resulting in the previously observed difference of SFs (Figure 3G). The 14-3-3/Pin1/28 complex showed the highest cooperativity with an α-factor = 270 and with only 1 μM of 28 necessary to induce a 2-fold increase in PPI stabilization. Interestingly, while FCA elicits stabilization for the 14-3-3/Pin1 complex at concentrations of 8 μM (SF8μM ≈ 10), the observed shift of apparent KD remains constant also at higher concentrations of FCA (Figure 3F). This weaker cooperative profile may be a function of the bulky hydrophobic properties of FCA, having a higher intrinsic affinity to 14-3-3 but being less compatible with the size of Trp+1 for optimal stabilization (Figure 3I).41

To better understand how structural changes in 13, 23, 27, and 28 translated to different cooperativity, the compounds were soaked into 14-3-3/Pin1 crystals. Analysis of the crystal structures shows conformational changes at the composite interface that potentially drive cooperative behavior. The 14-3-3/Pin1/28 complex showed a conformational change in Asn42 side chain of 14-3-3 induced by the presence of the 2,4-difluorophenyl ring of 28. Specifically, this induces a conformational change in Asn42 of 14-3-3 facilitating a direct hydrogen bond with Gln+3 of Pin1 (Figure 3H). Notably, this interaction is absent in the crystal structures of 13 and 27 (Figure 3C, Figure S6). Additionally, we observed that the 4-fluoro occupies a deep pocket formed by Cys38, Arg41, and Phe119, thereby locking the orientation of the 2,4-difluorophenyl ring. It was also observed that the indole side chain of Trp+1 has an inverted conformation compared to 13 and 27 (Figure 3C,H, Figure S6). Notably, the 14-3-3/Pin1/23 complex shows two conformations for Trp+1, suggesting that the side chain is not in the lowest energy state (Figure S5). Furthermore, the alternative Trp+1 conformation induced by 28 allows the formation of water-mediated hydrogen bonds between the indole moiety of Trp+1 and Gln+3 of Pin1 and Asn42 and Ser45 of 14-3-3 (Figure 3H). These additional contacts at the interface of the complex potentially explain the improved cooperative behavior. We further hypothesize that these Pin1 specific interactions will result in high selectivity of these fragments toward the Pin1/14-3-3 complex.

Selectivity Screening of Covalent Fragments

Drugging the hub protein 14-3-3 raises the challenge of selectivity. We hypothesized that the high level of cooperative behavior for the 14-3-3/Pin1_72/28 complex is a function of the unique functionality and topology of the interface, specifically the +1 and +3 amino acid of Pin1_72 with the covalent fragment (Figure 3H). We further rationalized that this cooperativity would likely translate to high selectivity. To test this, fragments 13, 27, and 28 were screened against a panel of 13 peptides as diverse representatives of 14-3-3 client proteins, differing in size and hydrophobicity of the +1 amino acid (Figure 4A). First, 14-3-3 interaction partners with polar amino acids in the +1 position were investigated. C-Raf has a threonine in the +1 position, whereby the hydroxyl group sufficiently abolishes any stabilizing effect of 13, 27, and 28. Glutamic acid, glutamine, cysteine, or serine, in this position, as offered by the B-Raf_729, TBC1D237, ERRγ_179, and Mypt1_ 472 peptides, showed no significant stabilization with 13, 27, and 28. A polar amino acid in the +1 position is not compatible with these imine forming fragments. This is likely due to the direct hydrogen bond possible between Lys122 of 14-3-3 and the polar side chain of the +1 amino acid, coupled with the repulsive behavior of a polar amino acid perpendicular to the aromatic ring of benzaldehyde. Similar to polar +1 amino acids, a C-terminal phosphorylation motif, as prototypical for ERα, was also not responsive to fragment stabilization with 13, 27, and 28. Again, salt bridge formation between Lys122 and the carboxylic acid terminus of ERα is the most logical rationale.44 This is in contrast to the natural compound FCA which elicits a 160-fold stabilization of the 14-3-3/ERα complex.

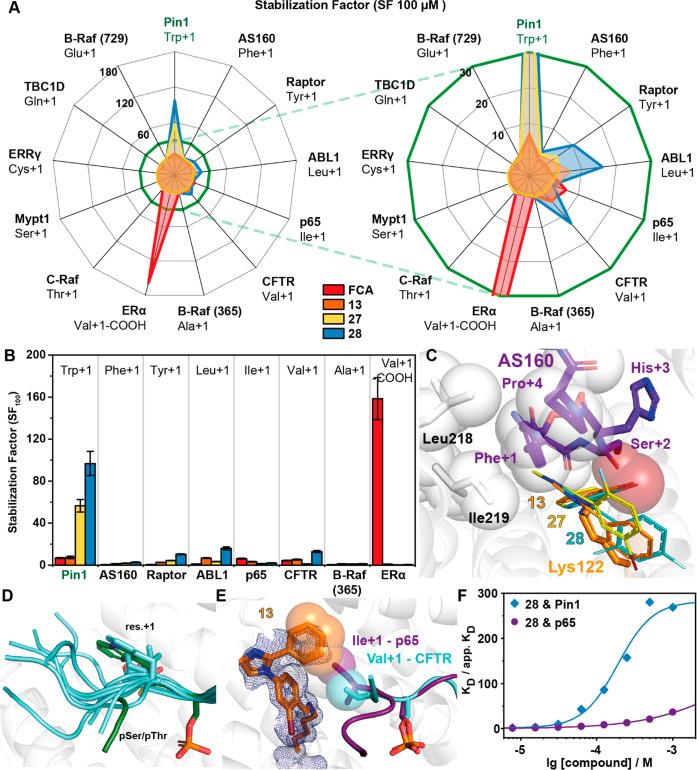

Figure 4.

Investigation of 13 representative 14-3-3/peptide interactions reveals selective stabilization of the 14-3-3/Pin1_72 complex by 28. (A) Radar plot of the SFs determined by FA protein titrations in the presence of 100 μM fragment. Fragment 28 shows preferential binding for the Pin1_72/14-3-3γ comparable to the effect of FCA on the ERα/14-3-3γ interaction. Right: close-up. (B) SF values determined with 14-3-3γ titrations in the presence of 100 μM 13, 27, or 28 in FA assays (n = 2). (C) Overlay of the binding pose of 13, 27, and 28 (line representation) with the AS160 binding epitope (violet sticks; PDB code 7NIX). (D) Structural overlay of the known 14-3-3 binding epitopes used in this study. (E) Overlay of crystal structures of 13 (orange sticks, 2Fo – Fc map at 1σ as blue mesh) binding to the p65_45 (violet sticks, carton)/14-3-3γ complex (PDB code 7NQP) and the CFTR (cyan sticks, cartoon)/14-3-3 complex (PDB code 5D3F, FC-A hidden for clarity). Hydrophobic contacts between 13 and Ile+1 of p65 and Val+1 of CFTR are indicated by transparent spheres. (F) Cooperative analysis of ternary complex formation using 28 with Pin1 and p65 peptides shows that stabilization of the ternary complex is driven by the unique environment created by the partner peptide binding.

Following the importance of the tryptophan for complex stabilization of Pin1_72/14-3-3γ with the benzaldehydes, the influence of phenylalanine (AS160) and tyrosine (Raptor) was investigated (Figure 4A,B). No appreciable stabilization of the AS160/14-3-3γ complex was observed with any of the fragments (13, 27, and 28), with SFs ranging from 1.2 to 2.7. The crystal structure of AS160 shows that the phenyl side chain employs similar hydrophobic contacts with the roof of 14-3-3 as Trp+1 of Pin1_72 (Figure 4C). Unlike Pin1_72, the C-terminus of AS160 engages Phe+1 in intramolecular hydrophobic contacts with Pro+4 and Pro+5. The +1 phenylalanine likely cannot rearrange to allow fragment binding. The Raptor/14-3-3γ binary complex proved to be more responsive to fragment stabilization with 28 showing a 9.5-fold stabilization of the binary complex. No structural data are available for the Raptor/14-3-3 interface.

The aldimine formation with Lys122 was first identified for the p65/14-3-3 interaction, with p65, which contains an isoleucine at the +1 position.34 Hence, small hydrophobic residues could potentially form hydrophobic contacts with the benzaldehyde scaffold. This was investigated by comparing the effect of 13, 27, and 28 on 14-3-3 interaction partners with a leucine (Abl1pT735), isoleucine (p65pS45), or valine (CFTRpS753) at the +1 position. Fragments 13 and 28 elicited some stabilizing activity for all three interaction partners with SF values ranging from 4.7 for 13 with p65 to 12.5 for 27 with CFTR. Fragment 27 induced no significant complex stabilization. The B-Raf_365 peptide with an alanine in the +1 position was not responsive to complex stabilization by any of the imine-forming aldehydes. This is likely a result of the topology formed by the C-terminus of B-Raf_365, which creates a smaller binding pocket occluding the fragments.29 This demonstrates not only the functionality of the C-terminus of the partner protein is important, but the topology of the binding pocket formed by the interaction partner also dictates binding (Figure 4D).

Remarkably, none of the fragments showed any significant inhibiting effects on binary complex formation, indicating a very low intrinsic affinity of the aldehyde fragments toward 14-3-3 alone. This is exemplified by peptides B-Raf_365 (Ala+1), ERRγ (Cys+1) and C-terminally truncated ERα (Val+1-COOH) where the addition of 100 μM fragment resulted in no change in KD value of the binary complex formation (Figure S7A). We further investigated whether these fragments elicited competitive behavior against non-stabilized interactions in a dose-dependent manner, by titrating the fragment to a fixed concentration of 14-3-3 and partner peptide (Figure S7B). B-Raf_365, which has a hydrophobic residue in the +1 position and is not stabilized by the fragments, showed no inhibition of 14-3-3/partner peptide complex formation at concentration of ≤1.5 mM of 27 or 28 (Figure S7C). Titration of 27 or 28 to a complex of 14-3-3/ERRγ or 14-3-3/ERα, which forms hydrogen bonds with Lys122, showed no competitive behavior at concentration of ≤750 μM. Notably, 28 and 27 showed moderate to low inhibition of ERα at a high micromolar concentration (750–1500 μM), respectively. In regard to ERRγ, inhibition of peptide binding was only observed at a concentration of 1.5 mM for 28. This suggests that the aldehyde fragments have a low intrinsic affinity toward 14-3-3 alone. This leads to a desirable, noncompetitive binding mode.

Soakings of 13 and 23 into p65/14-3-3σΔC complexes provided an explanation of selectivity. The ternary complex with p65/14-3-3σΔC/13 showed a distinct binding pose to the fragments in comparison with Pin1_72/14-3-3σΔC. Specifically, the 2-phenyl ring of 13 and 23 points toward Ile+1 of p65_45 (Figure 4E, Table S4). In this orientation, the Ile+1 makes hydrophobic contacts with both benzene rings of 13 and 23, providing a rationale for the correlation of the size of the hydrophobic residue and the observed complex stabilization. With the increasing size of the +1 amino acid, the residue fills more of the physical space between the two ring systems. The additional bromine of 23 pushes the 2-phenyl ring away from the roof of 14-3-3σΔC, explaining the lower activity toward Abl1, p65, and CFTR (Figure S6). While a crystal structure of 28 with p65 was not obtained, given the structural similarities of the fragments, it can be assumed that 28 adopts a similar binding pose. The conformational change of 13 and 23 within the p65/14-3-3 complex illustrates how the functionality and topology of the binding partner influence ligand binding. While direct hydrophobic contacts were observed with the fragments 13 and 23, compared with the Pin1_72/14-3-3 complex, there are significantly fewer interactions occurring at the composite interface within the p65/14-3-3 complex.

Finally, we performed a cooperativity analysis of the 14-3-3/p65/28 complex to investigate how these structural observations translate to cooperativity. For the 14-3-3/p65/28 complex, saturation of the system was not achieved at concentration of ≤1 mM with SF1mM = 37 (Figure 4F). This stabilization effect remains relatively small compared to the 270-fold stabilization of the Pin1/14-3-3 complex by 28 already achieved at lower concentrations. This lower cooperativity profile suggests that hydrophobic contacts of the phenyl and benzaldehyde rings of 28 with Ile+1 of p65 do not contribute significantly to the stabilization of the ternary complex. More importantly, the lack of induced additional 14-3-3/p65 contacts upon binding of 28, as seen with Pin1, likely accounts for the disparity in cooperativity. The cooperative interactions within the 14-3-3/Pin1/28 complex are thus significant driving factors for selective stabilization.

A recent screening campaign mapping the effect of PROTACS on cellular interaction networks suggests that a disturbance of the E3-ligase interactome is predominately responsible for the cellular activities of the tested compounds.45 The high affinity of the compounds toward the E3-ligases, which were supposed to label target proteins for degradation, hijacked their natural interactome. A lower intrinsic affinity of molecular glues toward hub proteins, like the E3-ligases or 14-3-3 proteins, reduces the risk of a general disturbance of the related interactome. This aligns with our findings that the cooperative ternary complex formation with a low intrinsic affinity of the fragment toward the hub protein is beneficial for selective PPI stabilization.

Conclusions

Targeting hub proteins, such as 14-3-3, via PPI modulation raises the challenge of achieving selectivity. Here we demonstrate a covalent imine-based tethering approach for de novo development of highly selective stabilizer fragments for the hub protein 14-3-3, within only a few focused library iterations. Critical to the development of selective stabilizers is the location of the covalent anchor at the interface of the composite pocket. In contrast to anchor points peripheral to the interface, this approach biases fragments that are selective for a specific PPI interaction by exploiting templating effects of the partner protein. We show that by harnessing unique topologies and functionalities within a composite binding pocket, unique fragments specific for the complex can be identified. Building upon these fragments to engage with the partner protein enabled the rapid identification of fragment based molecular glues which elicit submicromolar stabilizing activity. Further, we show how the 14-3-3/Pin1 complex can selectively be stabilized over other 14-3-3/complexes and demonstrate that the use of aldehydes as reversible covalent chemical probes does not lead to the inhibition of other 14-3-3 complexes formation. This highlights the advantage of dynamic covalent tethering over nonreversible covalent bonds. Utilizing cooperative analysis and X-ray crystallography, we elucidate the cooperativity of this series of fragments and the mechanism of action. Selectivity screening using a panel of 14-3-3 partner peptides identifies fragment 28 as highly selective for the Pin1 interaction. This is an important step forward in PPI stabilization of specifically hub proteins, such as 14-3-3, showing that a specific interaction can be stabilized over other interactions with a common binding motif. Finally, we show that by exploiting cooperative behavior, we can drive selective complex formation. Specifically, we observed that direct communication through ligand–peptide interactions is critical to cooperativity, inducing additional interactions between the two protein partners that are relevant for the 14-3-3/Pin1/28 complex stability. The research shown here is relevant to the ongoing growth of molecular glues as drug candidates. Further, observations seen here are, for example, laterally translatable to the field of cooperative PROTACS and to the further understanding of biochemical cooperativity.46

Acknowledgments

We kindly acknowledge the team at Taros Chemicals GmbH & Co. KG for providing the fragment aldehyde library for initial testing. We also thank Joost L. J. van Dongen for performing HRMS measurements and Bente A. Somsen for assistance with TSA measurements and the development of the protocol.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.1c03035.

Supplementary tables and figures, general materials and methods, and compound characterization (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ P.J.C. and M.W. contributed equally. The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors.

The research was supported by funding from the European Union through the Eurotech Postdoctoral Fellow program (Marie Skłodowska-Curie Co. funded, Grant 754462) and the TASPPI project (H2020-MSCA-ITN-2015, Grant 675179) and through The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) via VICI Grant 016.150.366 and Gravity Program 024.001.035.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): L.B. and C.O. are scientific founders of Ambagon Therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

References

- Arkin M. R.; Tang Y.; Wells J. A. Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Protein-Protein Interactions: Progressing toward the Reality. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21 (9), 1102–1114. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick E.; Bradley A.; Gan J.; Douangamath A.; Krojer T.; Sethi R.; Geurink P. P.; Aimon A.; Amitai G.; Bellini D.; Bennett J.; Fairhead M.; Fedorov O.; Gabizon R.; Gan J.; Guo J.; Plotnikov A.; Reznik N.; Ruda G. F.; Díaz-Sáez L.; Straub V. M.; Szommer T.; Velupillai S.; Zaidman D.; Zhang Y.; Coker A. R.; Dowson C. G.; Barr H. M.; Wang C.; Huber K. V. M.; Brennan P. E.; Ovaa H.; Von Delft F.; London N. Rapid Covalent-Probe Discovery by Electrophile-Fragment Screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (22), 8951–8968. 10.1021/jacs.9b02822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A.; Fesik S. W.; Hubbard R. E.; Jahnke W.; Jhoti H. Twenty Years on: The Impact of Fragments on Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15 (9), 605–619. 10.1038/nrd.2016.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A.; Davis B. J.; Jahnke W. Fragment-Based Drug Discovery: Advancing Fragments in the Absence of Crystal Structures. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26 (1), 9–15. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton S. E.; Campos S. Covalent Small Molecules as Enabling Platforms for Drug Discovery. ChemBioChem 2020, 21 (8), 1080–1100. 10.1002/cbic.201900674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson P. N.; Erlanson D. A.; De Esch I. J. P.; Jahnke W.; Johnson C. N. Fragment-to-Lead Medicinal Chemistry Publications in 2017. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62 (8), 3857–3872. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milroy L. G.; Grossmann T. N.; Hennig S.; Brunsveld L.; Ottmann C. Modulators of Protein-Protein Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (9), 4695–4748. 10.1021/cr400698c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong M.; Lee G. M.; Sijbesma E.; Ottmann C.; Arkin M. R. Modulating Protein-Protein Interaction Networks in Protein Homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 50, 55–65. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S. L. The Rise of Molecular Glues. Cell 2021, 184 (1), 3–9. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerry C. J.; Schreiber S. L. Unifying Principles of Bi-functional, Proximity-Inducing Small Molecules. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16 (4), 369–378. 10.1038/s41589-020-0469-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira M.; Calabrese M. F.; Bullock A. N.; Crews C. M. Targeted Protein Degradation: Expanding the Toolbox. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2019, 18 (12), 949–963. 10.1038/s41573-019-0047-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamshon S.; Ruan J. IMiDs New and Old. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2019, 14 (5), 414–425. 10.1007/s11899-019-00536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Gao H.; Yang Y.; He M.; Wu Y.; Song Y.; Tong Y.; Rao Y. Protacs: Great Opportunities for Academia and Industry. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 64. 10.1038/s41392-019-0101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadd M. S.; Testa A.; Lucas X.; Chan K. H.; Chen W.; Lamont D. J.; Zengerle M.; Ciulli A. Structural Basis of PROTAC Cooperative Recognition for Selective Protein Degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13 (5), 514–521. 10.1038/nchembio.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S. J.; Ciulli A. Molecular Recognition of Ternary Complexes: A New Dimension in the Structure-Guided Design of Chemical Degraders. Essays Biochem. 2017, 61 (5), 505–516. 10.1042/EBC20170041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashore C.; Jaishankar P.; Skelton N. J.; Fuhrmann J.; Hearn B. R.; Liu P. S.; Renslo A. R.; Dueber E. C. Cyano-pyrrolidine Inhibitors of Ubiquitin Specific Protease 7 Mediate Desulfhydration of the Active-Site Cysteine. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15 (6), 1392–1400. 10.1021/acschembio.0c00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenbeck K.; Turner D.; Renslo A.; Arkin M. Targeting Non-Catalytic Cysteine Residues Through Structure-Guided Drug Discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 17 (1), 4–15. 10.2174/1568026616666160719163839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowsky J. D.; Burlingame M. A.; Wolan D. W.; McClendon C. L.; Jacobson M. P.; Wells J. A. Turning a Protein Kinase on or off from a Single Allosteric Site via Disulfide Trapping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108 (15), 6056–6061. 10.1073/pnas.1102376108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrem J. M.; Peters U.; Sos M. L.; Wells J. A.; Shokat K. M. K-Ras(G12C) Inhibitors Allosterically Control GTP Affinity and Effector Interactions. Nature 2013, 503 (7477), 548–551. 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London N.; Miller R. M.; Krishnan S.; Uchida K.; Irwin J. J.; Eidam O.; Gibold L.; Cimermančič P.; Bonnet R.; Shoichet B. K.; Taunton J. Covalent Docking of Large Libraries for the Discovery of Chemical Probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10 (12), 1066–1072. 10.1038/nchembio.1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabizon R.; Shraga A.; Gehrtz P.; Livnah E.; Shorer Y.; Gurwicz N.; Avram L.; Unger T.; Aharoni H.; Albeck S.; Brandis A.; Shulman Z.; Katz B.-Z.; Herishanu Y.; London N. Efficient Targeted Degradation via Reversible and Irreversible Covalent PROTACs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (27), 11734–11742. 10.1021/jacs.9b13907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond M. J.; Chu L.; Nalawansha D. A.; Li K.; Crews C. M. Targeted Degradation of Oncogenic KRASG12C by VHL-Recruiting PROTACs. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6 (8), 1367–1375. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijbesma E.; Hallenbeck K. K.; Leysen S.; De Vink P. J.; Skóra L.; Jahnke W.; Brunsveld L.; Arkin M. R.; Ottmann C. Site-Directed Fragment-Based Screening for the Discovery of Protein-Protein Interaction Stabilizers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (8), 3524–3531. 10.1021/jacs.8b11658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijbesma E.; Somsen B. A.; Miley G. P.; Leijten-Van De Gevel I. A.; Brunsveld L.; Arkin M. R.; Ottmann C. Fluorescence Anisotropy-Based Tethering for Discovery of Protein-Protein Interaction Stabilizers. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15 (12), 3143–3148. 10.1021/acschembio.0c00646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter M.; Valenti D.; Cossar P. J.; Levy L. M.; Hristeva S.; Genski T.; Hoffmann T.; Brunsveld L.; Tzalis D.; Ottmann C. Fragment-Based Stabilizers of Protein-Protein Interactions through Imine-Based Tethering. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (48), 21520–21524. 10.1002/anie.202008585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluchanko N. N.; Bustos D. M.. Intrinsic Disorder Associated with 14-3-3 Proteins and Their Partners. In Dancing Protein Clouds: Intrinsically Disordered Proteins in Health and Disease, Part A; Uversky V. N., Ed.; Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, Vol. 166; Academic Press, 2019; Chapter 2, pp 19–61, 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan L.; Chou P. C.; Velazquez-Torres G.; Samudio I.; Parreno K.; Huang Y.; Tseng C.; Vu T.; Gully C.; Su C. H.; Wang E.; Chen J.; Choi H. H.; Fuentes-Mattei E.; Shin J. H.; Shiang C.; Grabiner B.; Blonska M.; Skerl S.; Shao Y.; Cody D.; Delacerda J.; Kingsley C.; Webb D.; Carlock C.; Zhou Z.; Hsieh Y. C.; Lee J.; Elliott A.; Ramirez M.; Bankson J.; Hazle J.; Wang Y.; Li L.; Weng S.; Rizk N.; Wen Y. Y.; Lin X.; Wang H.; Wang H.; Zhang A.; Xia X.; Wu Y.; Habra M.; Yang W.; Pusztai L.; Yeung S. C.; Lee M. H. The Cell Cycle Regulator 14-3-3σ Opposes and Reverses Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7530. 10.1038/ncomms8530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doveston R. G.; Kuusk A.; Andrei S. A.; Leysen S.; Cao Q.; Castaldi M. P.; Hendricks A.; Brunsveld L.; Chen H.; Boyd H.; Ottmann C. Small-Molecule Stabilization of the P53 - 14-3-3 Protein-Protein Interaction. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591 (16), 2449–2457. 10.1002/1873-3468.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y.; Ognjenović J.; Banerjee S.; Karandur D.; Merk A.; Kulhanek K.; Wong K.; Roose J. P.; Subramaniam S.; Kuriyan J. Cryo-EM Structure of a Dimeric B-Raf:14-3-3 Complex Reveals Asymmetry in the Active Sites of B-Raf Kinases. Science 2019, 366 (6461), 109–115. 10.1126/science.aay0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molzan M.; Ottmann C. Synergistic Binding of the Phosphorylated S233- and S259-Binding Sites of C-RAF to One 14-3-3ζ Dimer. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 423 (4), 486–495. 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera C.; Fernández-Majada V.; Inglés-Esteve J.; Rodilla V.; Bigas A.; Espinosa L. Efficient Nuclear Export of P65-IκBα Complexes Requires 14-3-3 Proteins. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129 (12), 2472–2472. 10.1242/jcs.192641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevers L. M.; Lam C. V.; Leysen S. F. R.; Meijer F. A.; van Scheppingen D. S.; de Vries R. M. J. M.; Carlile G. W.; Milroy L. G.; Thomas D. Y.; Brunsveld L.; Ottmann C. Characterization and Small-Molecule Stabilization of the Multisite Tandem Binding between 14-3-3 and the R Domain of CFTR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113 (9), E1152–E1161. 10.1073/pnas.1516631113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obsil T.; Obsilova V. Structural Basis of 14-3-3 Protein Functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 22 (7), 663–672. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter M.; Valenti D.; Cossar P. J.; Levy L. M.; Hristeva S.; Genski T.; Hoffmann T.; Brunsveld L.; Tzalis D.; Ottmann C. Fragment-Based Stabilizers of Protein-Protein Interactions through Imine-Based Tethering. Angew. Chem. 2020, 132 (48), 21704–21708. 10.1002/ange.202008585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y.-Y.; Chou P.-C.; Phan L.; Su C.-H.; Chen J.; Hsieh Y.-C.; Xue Y.-W.; Qu C.-J.; Gully C.; Parreno K.; Teng C.; Hsu S.-L.; Yeung S.-C.; Wang H.; Lee M.-H. DNA Damage-Mediated c-Myc Degradation Requires 14-3-3 Sigma. Cancer Hallm. 2013, 1 (1), 3–17. 10.1166/ch.2013.1002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinger J.; Jones K.; Cheeseman M. D. Lysine-Targeting Covalent Inhibitors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (48), 15200–15209. 10.1002/anie.201707630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinger J.; Carter M.; Jones K.; Cheeseman M. D. Kinetic Optimization of Lysine-Targeting Covalent Inhibitors of HSP72. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62 (24), 11383–11398. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinger J.; Le Bihan Y.-V.; Widya M.; van Montfort R. L. M.; Jones K.; Cheeseman M. D. An Irreversible Inhibitor of HSP72 That Unexpectedly Targets Lysine-56. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (13), 3536–3540. 10.1002/anie.201611907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter M.; de Vink P.; Neves J. F.; Srdanovic S.; Hi-Guchi Y.; Kato N.; Wilson A. J.; Landrieu I.; Brunsveld L.; Ottmann C. Selectivity via Cooperativity: Preferential Stabilization of the P65/14-3-3 Interaction with Semi-Synthetic Natural Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (27), 11772–11783. 10.1021/jacs.0c02151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira F.; Tinti M.; Murugesan G.; Berrett E.; Stafford M.; Toth R.; Cole C.; MacKintosh C.; Barton G. J. 14-3-3-Pred: Improved Methods to Predict 14-3-3-Binding Phosphopeptides. Bioinformatics 2015, 31 (14), 2276–2283. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vink P. J.; Andrei S. A.; Higuchi Y.; Ottmann C.; Milroy L.-G.; Brunsveld L. Cooperativity Basis for Small-Molecule Stabilization of Protein-Protein Interactions. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (10), 2869–2874. 10.1039/C8SC05242E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson J. R. Cooperativity in Macromolecular Assembly. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4 (8), 458–465. 10.1038/nchembio.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T.; Williams M. Defining and Characterizing Drug/Compound Function. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 87 (1), 40–63. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries-Van Leeuwen I. J.; da Costa Pereira D.; Flach K. D.; Piersma S. R.; Haase C.; Bier D.; Yalcin Z.; Michalides R.; Feenstra K. A.; Jimenez C. R.; de Greef T. F. A.; Brunsveld L.; Ottmann C.; Zwart W.; de Boer A. H. Interaction of 14-3-3 Proteins with the Estrogen Receptor Alpha F Domain Provides a Drug Target Interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110 (22), 8894–8899. 10.1073/pnas.1220809110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor-Ruiz C.; Jaeger M. G.; Bauer S.; Brand M.; Sin C.; Hanzl A.; Mueller A. C.; Menche J.; Winter G. E. Plasticity of the Cullin-RING Ligase Repertoire Shapes Sensitivity to Ligand-Induced Protein Degradation. Mol. Cell 2019, 75 (4), 849–858. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson M.; Crews C. M. PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) — Past, Present and Future. Drug Discovery Today: Technol. 2019, 31, 15–27. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.