Abstract

Background:

Immunization is an important strategy for controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 vaccination was recently launched in Uganda, with prioritization to healthcare workers and high-risk individuals. In this study, we aimed to determine the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine among persons at high risk of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in Uganda.

Methods:

Between 29 March and 14 April 2021, we conducted a cross-sectional survey consecutively recruiting persons at high risk of severe COVID-19 (diabetes mellitus, HIV and cardiovascular disease) attending Kiruddu National Referral Hospital outpatient clinics. A trained research nurse administered a semi-structured questionnaire assessing demographics, COVID-19 vaccine related attitudes and acceptability. Descriptive statistics, bivariate and multivariable analyses were performed using STATA 16.

Results:

A total of 317 participants with a mean age 51.5 ± 14.1 years were recruited. Of this, 184 (60.5%) were female. Overall, 216 (70.1%) participants were willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. The odds of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination were four times greater if a participant was male compared with if a participant was female [adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 4.1, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.8–9.4, p = 0.00]. Participants who agreed (AOR: 0.04, 95% CI: 0.01–0.38, p = 0.003) or strongly agreed (AOR: 0.04, 95% CI: 0.01–0.59, p = 0.005) that they have some immunity against COVID-19 were also significantly less likely to accept the vaccine. Participants who had a history of vaccination hesitancy for their children were also significantly less likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine (AOR: 0.1, 95% CI: 0.01–0.58, p = 0.016).

Conclusion:

The willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine in this group of high-risk individuals was comparable to the global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate. Increased sensitization, myth busting and utilization of opinion leaders to encourage vaccine acceptability is recommended.

Keywords: COVID-19, high-risk population, Uganda, vaccines

Introduction

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a major global health crisis of the 21st century. 1 Approximately 2.3% of the world’s population has now been infected by the severe acute respiratory coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2), the novel coronavirus and etiologic agent of COVID-19, and more than 3.3 million people have died. 2 In addition, thousands of individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 illness have been left with long-term complications – dubbed “long COVID-19” – and other chronic COVID-19 syndromes. 3

COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality in high-risk individuals, such as those with diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases, is substantial and current treatment options are limited.4–6 Fortunately, with the global rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines, there is emerging evidence that the COVID-19 vaccines can reduce the severity of infection and prevent deaths. 7 Real world data emanating from a nationwide mass vaccination program in Israel, in an uncontrolled setting, have recently shown that the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine was effective for preventing symptomatic COVID-19, COVID-19-related hospitalization, severe illness and death. 8

Globally, over 1.3 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccines have been administered with about 4.1% of the population being fully vaccinated as of 10 May 2021. 9 However, a recent survey has shown that the potential acceptance of these vaccines varies from country to country, with over 80% acceptance in China, Singapore and South Korea to less than 55% in Russia. 10 Some of the main reasons for reporting non-intent to receive vaccine were concerns about vaccine side effects and safety and lack of trust in the vaccine development process.11,12

In Uganda, COVID-19 vaccination with the AstraZeneca vaccine was launched on 10 March 2021, with priority being given to healthcare workers and individuals at risk of severe COVID-19 and death. However, little is known about acceptance of receiving the vaccine among Ugandans, especially in the priority groups. Reports from the government of Uganda also indicate there is a slow uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine in the country, with only about 400,000 people vaccinated by 10 May 2021. 13 Therefore, in this study, we assessed the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines and associated factors among persons at high risk of severe COVID-19 attending a large tertiary health facility in Uganda.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive, cross-sectional study employing quantitative techniques was conducted between 29 March and 14 April 2021.

Study setting

The study was carried out at Kiruddu National Referral Hospital (KNRH). KNRH is a public tertiary referral hospital that offers a wide array of inpatient and outpatient healthcare services mainly in internal medicine, radiology, plastic and reconstructive surgery and radiology. There are established outpatient clinics that run from Monday to Friday every week. The cardiovascular disease clinics run on Monday and Tuesday, diabetes clinic on Wednesday and HIV clinic on Friday. The clinic has an average attendance of 100–150 adults. KNRH is one of the sites offering COVID-19 vaccines to healthcare workers and high-risk individuals. At the time of data collection, vaccination was on going at the study site.

Study population

Patients attending outpatient clinics at KNRH constituted the study population. Eligible participants were those aged 18 years or older, living with diabetes, HIV, or any cardiovascular diseases who provided an informed written consent to participate in the study. Patients aged 50 years or older with or without any co-morbidity were included in the study. Patients who presented with severe, acute complications of diabetes mellitus, hypertensive crisis and HIV complications requiring inpatient care were excluded from the study.

Sampling size

The sample size was calculated using Epi Info 7 StatCalc (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, United States) for population surveys. About 250 outpatients are seen on a daily basis at KNRH; however, numbers may be lower due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected over a period of 2 weeks (10 working days), giving an attendance of 2500 patients. Using an expected attendance of 2500, expected acceptability of 50% since no studies in similar settings exist, design effect of 1.0 and margin of error of 5%, the calculated required sample size was 333 patients.

Study procedure

Eligible participants were enrolled by consecutive sampling until the required sample size was reached. Two trained research nurses and two medical doctors recruited the patients in the study, obtained written informed consent and administered the questionnaires. Independent variables were: demographic details, which included sex, age, profession, highest level of education, religion, residence, marital status and estimated monthly income. Dependent variables were: primary outcome variable – acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine, which was assessed using a closed ended question with a Yes/No response. Secondary outcome variable was vaccine hesitancy – evaluated as trust and attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine based on two closed ended questions with a Yes/No response. We validated this questionnaire in a population of medical students in Uganda. 14

The COVID-19 standard operating procedures set by the Ministry of Health, Uganda, were strictly adhered to throughout the study. Study staffs were equipped with personal protective equipment such as a facemask and a hand sanitizer.

Data management and analyses

Fully completed questionnaires were entered into EpiCollect 5® and exported as a spreadsheet. The data were then exported to STATA version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC., College Station, Texas, USA) for formal analysis. Categorical variables were first described as frequencies and percentages, numerical variables as mean or median as appropriate. To evaluate the association of independent variables, that is, demographics with the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine, a bivariate analysis (chi-square or Fisher’s exact test) was performed. All factors with a p < 0.2 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model to adjust for confounders. Associations with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Results are presented in tables, charts and graphs, as appropriate.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Mulago Hospital Research Ethics Committee (MHREC), approval number MHREC2014. Administrative clearance was sought from the KNRH Institutional Review Board. The study was conducted in accordance to the ethical codes outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and all participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Characteristics of participants

A total of 317 patients (response rate = 95%) at high risk of severe COVID-19 participated in this study. The mean age of the participants was 51.5 years (standard deviation = 14.1) and about two-thirds (n = 184, 60.5%) of the patients were female. Some 36.4% of the patients were unemployed and 67.4% were living in urban settlements. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the participants. Cardiovascular diseases (n = 188, 61.4%) were the most common comorbidities (Figure 1), followed by diabetes mellitus (n = 102, 33.3%) and HIV (n = 46, 15.0%).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Demographics (N = 308) | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years and standard deviation) | 51.5 | 14.1 |

| <50 years | 126 | 40.9 |

| 50+ years | 182 | 59.1 |

| Sex (n = 304) | ||

| Male | 120 | 39.5 |

| Female | 184 | 60.5 |

| Marital status (N = 305) | ||

| Never married | 18 | 5.9 |

| Married | 172 | 56.4 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 115 | 37.7 |

| Religion | ||

| Anglican | 104 | 33.8 |

| Roman Catholic | 99 | 32.1 |

| Muslim | 53 | 17.2 |

| Pentecostal | 42 | 13.6 |

| SDA | 1 | 0.3 |

| Atheist | 9 | 2.9 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| None | 23 | 7.5 |

| Primary | 127 | 41.2 |

| Secondary | 101 | 32.8 |

| Tertiary | 57 | 18.5 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 112 | 36.4 |

| Employee | 64 | 20.8 |

| Self employed | 132 | 42.9 |

| Residence (N= 291) | ||

| Rural | 95 | 32.6 |

| Urban | 196 | 67.4 |

| Estimated monthly income (UGX; N = 179) | 300,000 | 100,000–600,000 |

SDA, Seventh Day Adventist.

Figure 1.

Comorbidities among the participants.

COVID-19 risk perceptions and tests

More than half of the patients felt very likely to or extremely at risk of getting COVID-19 in the future (Table 2). In addition, up to 40.8% (n = 124) and 59.2% (n = 181) of the patients felt very worried about COVID-19 and at a major risk, respectively. Of note, only a few patients (n = 8, 2.6%), any of their friends (n = 17, 5.6%) or a member of their family (n = 15, 5.0%) had tested positive for COVID-19. Up to 62.5% of the patients disagreed that they had some immunity against COVID-19.

Table 2.

COVID-19 risk perceptions among patients at high risk of COVID-19 disease.

| Perception | N | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| How likely do you think you will get COVID-19 in future? | 301 | ||

| Extremely likely | 27 | 9.0 | |

| Very likely | 160 | 53.2 | |

| Moderate | 26 | 8.6 | |

| Slightly | 47 | 15.6 | |

| Not at all | 41 | 13.6 | |

| Overall, how worried are you about coronavirus? | |||

| Extremely worried | 304 | 124 | 40.8 |

| Very worried | 107 | 35.2 | |

| Not very worried | 23 | 7.6 | |

| Somewhat worried | 27 | 8.9 | |

| Not at all worried | 23 | 7.6 | |

| To what extent do you think coronavirus poses a risk to you personally? | |||

| Major risk | 306 | 181 | 59.2 |

| Moderate risk | 64 | 20.9 | |

| Minor risk | 35 | 11.4 | |

| No risk at all | 26 | 8.5 | |

| Do you think coronavirus poses a risk to people in Uganda? | |||

| Major risk | 304 | 168 | 55.3 |

| Moderate risk | 95 | 31.3 | |

| Minor risk | 31 | 10.2 | |

| No risk at all | 10 | 3.3 | |

| Do you know if you have had, or currently have, coronavirus? | |||

| I have definitely had it | 306 | 9 | 2.9 |

| I think I have probably had it | 5 | 1.6 | |

| I think I have probably not had it | 135 | 44.1 | |

| I have definitely not had it | 157 | 51.3 | |

| Have you been tested for coronavirus? | |||

| No | 305 | 269 | 88.2 |

| Yes – positive | 8 | 2.6 | |

| Yes – negative | 28 | 9.2 | |

| Has any of your family members tested for COVID-19? | |||

| No | 303 | 270 | 89.1 |

| Yes – positive | 15 | 5.0 | |

| Yes – negative | 18 | 5.9 | |

| Has any of your friends tested positive for COVID-19? | |||

| No | 306 | 278 | 90.9 |

| Yes – positive | 17 | 5.6 | |

| Yes – negative | 11 | 3.6 | |

| I think I have some immunity to coronavirus | |||

| Strongly agree | 299 | 11 | 3.7 |

| Agree | 40 | 13.4 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 61 | 20.4 | |

| Disagree | 164 | 54.9 | |

| Strongly disagree | 23 | 7.7 | |

Vaccine hesitancy

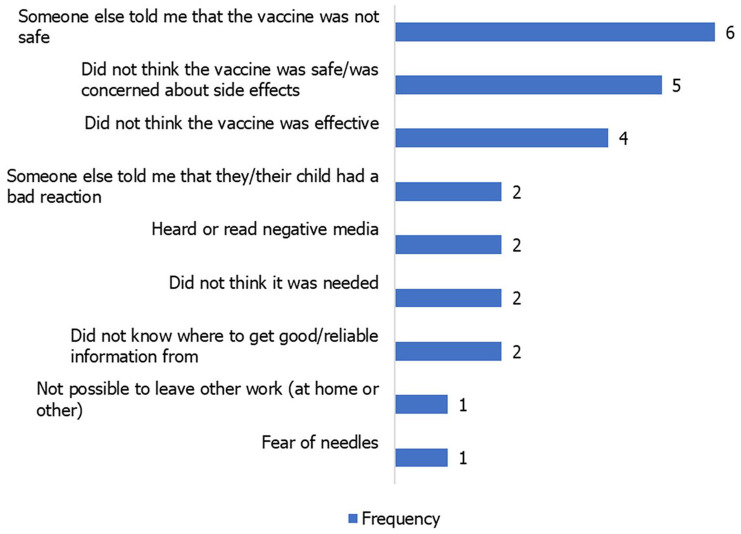

Hesitancy towards previous vaccines among patients who had children was relatively very low. Only 5.7% (n = 17) and 3.8% (n = 11) had been hesitant or had refused to have their children vaccinated, respectively (Figure 2). Among these, the issues of vaccine safety and efficacy were the most common reasons for hesitancy (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Reasons for refusing children access to vaccinations.

Figure 3.

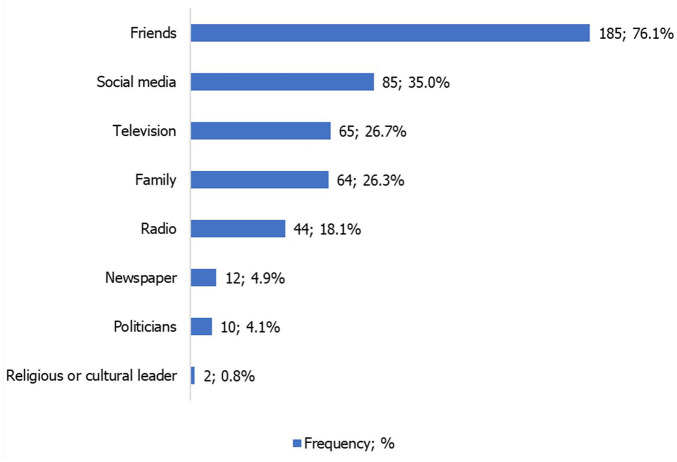

Sources of negative information on the COVID-19 vaccine among participants.

COVID-19 vaccine perceptions and acceptability

The vast majority (n = 295, 96.4%) were aware about the COVID-19 vaccine and over 50% of the patients agreed that the vaccine might be effective in protecting them against COVID-19. Up to 82.4% (n = 243) had ever heard negative information on the COVID-19 vaccine, and most of this was from friends (76.1%) and social media (35.0%).

Overall, 216 patients (70.1%) were willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccines. Self-protection, government recommendations and health-workers’ recommendations were the most frequent reasons for accepting the vaccine (Table 3). Of the 92 patients who were not willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine, negative information and safety concerns were the most frequent reasons (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among patients at high risk of severe COVID-19 disease.

| Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Reason for accepting the vaccine (N = 216) | ||

| To protect myself from getting COVID-19 | 203 | 94.0 |

| Government recommendations | 148 | 68.5 |

| Health workers’ recommendations | 101 | 46.8 |

| I am at high risk of severe disease | 79 | 36.6 |

| If it is available to me | 69 | 31.9 |

| If the vaccine is free of charge | 36 | 16.7 |

| The vaccines are safe | 33 | 15.3 |

| It is a social and moral responsibility | 32 | 14.8 |

| To protect others from getting COVID-19 | 22 | 10.2 |

| I believe in vaccines and immunization | 22 | 10.2 |

| The vaccines are effective | 22 | 10.2 |

| To be able to travel | 20 | 9.3 |

| To get rid of the virus and end the pandemic | 13 | 6.0 |

| Job requirement | 4 | 1.9 |

| Reason for refusing the COVID-19 vaccine (N = 92) | ||

| I have heard or read negative information on the vaccine | 59 | 64.1 |

| I don’t think the vaccine is safe | 53 | 57.6 |

| I don’t think the vaccine is effective | 45 | 48.9 |

| Someone else told me that the vaccine is not safe | 43 | 46.7 |

| I don’t think it is needed | 26 | 28.3 |

| I don’t know where to get good/reliable information | 21 | 22.8 |

| I trust my immunity | 8 | 8.7 |

| Had a bad experience with previous vaccinator/health clinic | 7 | 7.6 |

| I don’t know where to get vaccination | 4 | 4.3 |

| Had a bad experience or reaction with previous vaccination | 3 | 3.3 |

| The vaccine is costly for me | 3 | 3.3 |

| Fear of needles | 2 | 2.2 |

| Someone else told me they/their child had a bad reaction | 2 | 2.2 |

| Religious reasons | 1 | 1.1 |

| Not possible to leave other work | 1 | 1.1 |

Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptability

At bivariate analysis, sex (p = 0.005), perceived risk of future COVID-19 (p = 0.006), extent of worrying about the COVID-19 disease (p = 0.016), current perceived risk of COVID-19 (p < 0.001), perceived immunity to COVID-19 (p < 0.001), and perceived efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine (p < 0.001)) were significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptability (Table 4). A history of vaccine hesitancy (p < 0.001) or refusal (p = 0.013) were also significantly associated with acceptability (Table 4).

Table 4.

A bivariate analysis showing factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptability among patients at high risk of severe COVID-19 disease.

| Variables | Acceptability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No n = 92 |

Yes n = 216 |

p | |

| Age | |||

| <50 years | 40 (31.7) | 86 (68.3) | 0.550 |

| 50+ years | 52 (28.6) | 130 (71.4) | |

| Sex, N = 304 | |||

| Male | 25 (20.8) | 95 (79.2) | 0.005 |

| Female | 66 (35.9) | 118 (64.1) | |

| Marital status, N = 305 | |||

| Never married | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | 0.109 |

| Married | 43 (25) | 129 (75) | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 42 (36.5) | 73 (63.5) | |

| Religion | |||

| Anglican | 33 (31.7) | 71 (68.3) | 0.101 |

| Roman Catholic | 28 (28.3) | 71 (71.7) | |

| Muslim | 10 (18.9) | 43 (81.1) | |

| Pentecostal | 15 (35.7) | 27 (64.3) | |

| SDA | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Atheist | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Highest level of education | |||

| None | 10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5) | 0.170 |

| Primary | 43 (33.9) | 84 (66.1) | |

| Secondary | 25 (24.8) | 76 (75.2) | |

| Tertiary | 14 (24.6) | 43 (75.4) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 30 (26.8) | 82 (73.2) | 0.247 |

| Employee | 16 (25) | 48 (75) | |

| Self employed | 46 (34.8) | 86 (65.2) | |

| Residence, N = 291 | |||

| Rural | 28 (29.5) | 67 (70.5) | 0.873 |

| Urban | 56 (28.6) | 140 (71.4) | |

| Number of comorbidities | |||

| One | 71 (27.8) | 184 (72.2) | 0.207 |

| Two | 19 (40.4) | 28 (59.6) | |

| Three | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | |

| How likely do you think you will get COVID-19 in future? | |||

| Extremely likely | 4 (14.8) | 23 (85.2) | 0.006 |

| Moderate | 5 (19.2) | 21 (80.8) | |

| Not at all | 22 (53.7) | 19 (46.3) | |

| Slightly | 13 (27.7) | 34 (72.3) | |

| Very likely | 47 (29.4) | 113 (70.6) | |

| Overall, how worried are you about coronavirus? | |||

| Extremely | 35 (28.2) | 89 (71.8) | 0.016 |

| Not at all | 10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5) | |

| Not very | 13 (56.5) | 10 (43.5) | |

| Somewhat | 9 (33.3) | 18 (66.7) | |

| Very | 25 (23.4) | 82 (76.6) | |

| To what extent do you think coronavirus poses a risk to you personally? | |||

| Major risk | 49 (27.1) | 132 (72.9) | <0.001 |

| Minor risk | 20 (57.1) | 15 (42.9) | |

| Moderate risk | 11 (17.2) | 53 (82.8) | |

| No risk at all | 11 (42.3) | 15 (57.7) | |

| Do you think coronavirus poses a risk to people in Uganda? | |||

| Major risk | 42 (25) | 126 (75) | 0.245 |

| Minor risk | 11 (35.5) | 20 (64.5) | |

| Moderate risk | 34 (35.8) | 61 (64.2) | |

| No risk at all | 3 (30) | 7 (70) | |

| Do you know if you have had, or currently have, coronavirus? | |||

| I have definitely had it | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | 0.497 |

| I have definitely not had it | 45 (28.7) | 112 (71.3) | |

| I think I have probably had it | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | |

| I think I have probably not had it | 39 (28.9) | 96 (71.1) | |

| Have you been tested positive for coronavirus? | |||

| Yes | 2 (25) | 6 (75) | 0.747 |

| No | 90 (30.3) | 207 (69.7) | |

| Has any of your family members positive tested for COVID-19? | |||

| Yes | 4 (26.7) | 11 (73.3) | 0.749 |

| No | 88 (30.6) | 200 (69.4) | |

| Has any of your friends tested positive for COVID-19? | |||

| Yes | 6 (35.3) | 11 (64.7) | 0.606 |

| No | 85 (29.4) | 204 (70.6) | |

| I think I have some immunity to coronavirus | |||

| Agree | 17 (42.5) | 23 (57.5) | <0.001 |

| Disagree | 28 (17.1) | 136 (82.9) | |

| Neutral | 33 (54.1) | 28 (45.9) | |

| Strongly agree | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | |

| Strongly disagree | 4 (17.4) | 19 (82.6) | |

| Have you been hesitant to have your children vaccinated? | |||

| Yes | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 73 (26.2) | 206 (73.8) | |

| Have you ever refused to have your children vaccinated? | |||

| Yes | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | 0.013 |

| No | 80 (28.6) | 200 (71.4) | |

| Are you aware of the COVID-19 vaccine? | |||

| Yes | 87 (29.5) | 208 (70.5) | 0.257 |

| No | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | |

| COVID-19 vaccine may be effective in protecting me from COVID-19 | |||

| Agree | 18 (13.2) | 118 (86.8) | <0.001 |

| Disagree | 13 (59.1) | 9 (40.9) | |

| Neutral | 50 (44.6) | 62 (55.4) | |

| Strongly agree | 5 (19.2) | 21 (80.8) | |

| Strongly disagree | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | |

| Have you ever received or heard negative information about COVID-19 vaccination? | |||

| No | 12 (23.1) | 40 (76.9) | 0.164 |

| Yes | 80 (32.9) | 163 (67.1) | |

SDA, Seventh Day Adventist.

At multivariable analysis (Table 5), the odds of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination were four times greater if a participant was male compared with if a participant was female [adjusted odds ratio (AOR): 4.1, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.8–9.4, p = 0.001]. Patients who agreed (AOR: 0.04, 95% CI: 0.01–0.38, p = 0.003) or strongly agreed (AOR: 0.04, 95% CI: 0.01–0.59, p = 0.005) that they had some immunity against COVID-19 were also significantly less likely to accept the vaccine. Finally, patients who had a history of vaccine hesitancy for their children were also significantly less likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine (AOR: 0.1, 95% CI: 0.01–0.58, p = 0.016). Perceived risks to COVID-19 and perceived efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine lost significance at multivariable analyses.

Table 5.

Multivariable analysis model showing associations with COVID-19 acceptability among patients at high risk of severe disease.

| Variables | AOR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, N = 304 | ||

| Female | Reference | |

| Male | 4.1 (1.8–9.4) | 0.001 |

| Marital status, N = 305 | ||

| Never married | Reference | |

| Married | 2.3 (0.2–21.3) | 0.468 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 1.6 (0.2–15.3) | 0.689 |

| Religion | ||

| Anglican | Reference | |

| Roman Catholic | 2.1 (0.9–5.0) | 0.094 |

| Muslim | 2.9 (0.9–9.6) | 0.087 |

| Pentecostal | 1.6 (0.5–4.9) | 0.441 |

| Atheist | 0.2 (0.0–2.4) | 0.227 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| None | Reference | |

| Primary | 1.2 (0.3–4.9) | 0.794 |

| Secondary | 3.8 (0.8–17.0) | 0.086 |

| Tertiary | 1.5 (0.3–7.3) | 0.645 |

| How likely do you think you will get COVID-19 in future? | ||

| Not at all | Reference | |

| Slightly | 3.3 (0.7–15.5) | 0.131 |

| Moderate | 1.4 (0.2–9.7) | 0.729 |

| Very likely | 1.5 (0.3–6.7) | 0.612 |

| Extremely likely | 1.7 (0.2–13.8) | 0.608 |

| Overall, how worried are you about coronavirus? | ||

| Not at all | Reference | |

| Not very | 1.1 (0.1–10.3) | 0.935 |

| Somewhat | 2.6 (0.3–22.8) | 0.396 |

| Very | 1.7 (0.2–11.9) | 0.610 |

| To what extent do you think coronavirus poses a risk to you personally? | ||

| No risk at all | Reference | |

| Minor risk | 0.4 (0.1–2.8) | 0.381 |

| Moderate risk | 1.7 (0.2–11.8) | 0.586 |

| Major risk | 0.7 (0.1–5.1) | 0.707 |

| I think I have some immunity to coronavirus | ||

| Strongly disagree | Reference | |

| Disagree | 0.3 (0.0–2.1) | 0.232 |

| Neutral | 0.0 (0.0–0.3) | 0.003 |

| Agree | 0.0 (0.0–0.4) | 0.005 |

| Strongly agree | 0.0 (0.0–0.4) | 0.019 |

| Have you been hesitant to have your children vaccinated? | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.1 (0.0–0.6) | 0.016 |

| Have you ever refused to have your children vaccinated? | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.2 (0.1–13.0) | 0.902 |

| Have you ever received or heard negative information about COVID-19 vaccination? | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | 0.242 |

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed for the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine among persons at high risk of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in Uganda. About 70% of the study population was willing to receive the vaccine. Perceived risk of future COVID-19, extent of worrying about COVID-19, current perceived risk of COVID-19, perceived immunity to COVID-19 and perceived efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine were significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptability.

Interestingly, our recently concluded survey of over 600 medical students in Uganda showed that only 37.3% were willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. 14 This might be due to lack of correct information regarding the vaccine among medical students, which could have been consolidated by the current wave of speculations on the safety, especially the reported incidence of blood clots in AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson vaccines. 15 Medical students in our recent study also reported low perceived risk as a major factor for lack of willingness to accept the vaccine. 14 However, our finding is consistent with a global COVID-19 vaccine acceptability survey in which over 72% of over 13,000 individuals from 19 countries across the world were willing to receive a proven, safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine. 10

In our study, male patients were more likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. This corroborates with our findings in the medical student population, where male students were up to two times more likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. Among healthcare workers in Democratic Republic of Congo, males were also more likely to receive the vaccine. 16 This trend has been observed in Kuwait, 17 the general population in the United States, 18 and their health workers. 19 It is not yet clear as to why this gender difference has been continually reported in previous studies as well. 20 Men have been reported to generally take more risks in life than women. With the ongoing infodemic of antivax messages, we postulate that men may be willing to take a risk and receive the vaccine, hence the difference in acceptability.

Our study also demonstrated the impact of perceived immunity to the COVID-19 vaccine on its acceptability. Those who thought they had immunity towards COVID-19 were significantly less likely to accept the vaccine. This perception has been reported in the general population of Kuwait adults, 17 where self-perceived risks of contracting COVID-19, the self-perceived potential severity of their COVID-19 and perceptions on natural immunity towards COVID-19 affected acceptability in a similar trend. There is therefore need to provide clear information about development of immunity among patients who have previously had COVID-19, and intensifying risk communication to curb the reluctance observed in the general public in Uganda with regard to COVID-19 prevention.

Despite the proven efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines, breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection might still occur despite a complete vaccination. 21 Therefore, COVID-19 vaccine recipients should be reminded to continue other personal preventive measures to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission, such as masking and physical distancing when in public or around unvaccinated individuals who are at risk for severe COVID-19. 22

There is growing concern that vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination presence will dampen the uptake of the coronavirus vaccine. There are many cited reasons for vaccine hesitancy. Mercury content, autism association, concerns about vaccine side effects and safety, lack of trust in the process and vaccine danger have been commonly found in anti-vaccination messages. 23 In other studies, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy has been associated with younger age (e.g. <60 years old), self-identification as Black race, lower levels of education, lack of health insurance, sex, education, employment, income, having children at home, political affiliation and the perceived threat of getting infected with COVID-19 in the next 1 year.10–12,14 In the present study, we noted that individuals who perceived to have some immunity to COVID-19 were less likely to accept the vaccine.

Our study has some limitations. We had a small sample size and derived the study population from a single center. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to the general population of high-risk individuals in Uganda. However, our findings provide a useful information on potential strategies to optimize vaccine uptake among these high-risk populations. Future research work would be tailored at the actual uptake and completion of vaccination schedules in this population.

In conclusion, among high-risk individuals in Uganda, willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine was high. Target health communications aimed at addressing barriers to vaccine uptake has to be prioritized in this population.

Acknowledgments

Sarah Apoto for assisting with data entry.

Footnotes

Author contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files. Data are available upon reasonable request from the first author

Ethics statement: The study protocol was approved by the Mulago Hospital Research Ethics Committee (MHREC), approval number MHREC2014. Administrative clearance was sought from the KNRH Institutional Review Board. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical codes outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and all participants provided written informed consent.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of State’s Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy (S/GAC), and President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) under Award Number 1R25TW011213. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iDs: Felix Bongomin  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4515-8517

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4515-8517

Ronald Olum  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1289-0111

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1289-0111

Contributor Information

Felix Bongomin, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, Gulu University, P.O. Box 166, Gulu, Uganda; Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda.

Ronald Olum, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda.

Irene Andia-Biraro, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda.

Frederick Nelson Nakwagala, Department of Medicine, Mulago National Referral Hospital, Kampala, Uganda.

Khalid Hudow Hassan, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda.

Dianah Rhoda Nassozi, Department of Dentistry, School of Health Sciences, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda.

Mark Kaddumukasa, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda.

Pauline Byakika-Kibwika, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda.

Sarah Kiguli, Department of Pediatrics & Child Health, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda.

Bruce J. Kirenga, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda Lung Institute Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda.

References

- 1. Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19 – navigating the uncharted. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1268–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Woldometer. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (2021, accessed 20 April 2021).

- 3. Halpin S, O’Connor R, Sivan M. Long COVID and chronic COVID syndromes. J Med Virol 2021; 93: 1242–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moon SJ, Rhee EJ, Jung JH, et al. Independent impact of diabetes on the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 in 5,307 patients in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Diabetes Metab J 2020; 44: 737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang J, Wang X, Jia X, et al. Risk factors for disease severity, unimprovement, and mortality in COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26: 767–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bongomin F, Asio LG, Ssebambulidde K, et al. Adjunctive intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) for moderate-severe COVID-19: emerging therapeutic roles. Curr Med Res Opin. Epub ahead of print 31 March 2021. DOI: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1903849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fauci AS. The story behind COVID-19 vaccines. Science 2021; 372: 109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1412–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johns Hopkins University. Understanding the vaccination progress, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/vaccines/international (2021, accessed 18 April 2021).

- 10. Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 2021; 27: 225–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, et al. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health 2021; 46: 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaplan AK, Sahin MK, Parildar H, et al. The willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine and affecting factors among healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional study in Turkey. Int J Clin Pract. Epub ahead of print 16 April 2021. DOI: 10.1111/ijcp.14226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ministry of Health, Republic of Uganda. Update on COVID-19 vaccination in Uganda, https://www.health.go.ug/cause/update-on-covid-19-vaccination-in-uganda/ (2021, accessed 10 May 2021).

- 14. Kanyike AM, Olum R, Kajjimu J, et al. Acceptability of the coronavirus disease-2019 vaccine among medical students in Uganda: a cross sectional study. Trop Med Health 2021; 49: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCrae KR. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia due to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Cleve Clin J Med. Epub ahead of print 6 May 2021. DOI: 10.3949/ccjm.88a.ccc078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kabamba Nzaji M, Ngombe LK, Mwamba GN, et al. Acceptability of vaccination against COVID-19 among healthcare workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pragmat Obs Res 2020; 11: 103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alqudeimat Y, Alenezi D, AlHajri B, et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and its related determinants among the general adult population in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract 2021; 10: 2052–2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 26: 100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shekhar R, Sheikh AB, Upadhyay S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines 2021; 9: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flanagan KL, Fink AL, Plebanski M, et al. Sex and gender differences in the outcomes of vaccination over the life course. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2017; 33: 577–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levine-Tiefenbrun M, Yelin I, Katz R, et al. Initial report of decreased SARS-CoV-2 viral load after inoculation with the BNT162b2 vaccine. Nat Med 2021; 27: 790–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (2020, accessed 11 November 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pullan S, Dey M. Vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination in the time of COVID-19: a Google trends analysis. Vaccine 2021; 39: 1877–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]