Abstract

Aim: Clinical evidence on cardiovascular health metrics of couples, as defined by the American Heart Association (AHA), remains to be scarce. This study aims to explore the correlation of the AHA-defined cardiovascular health metrics within couples using a nationwide epidemiological database.

Methods: We examined the modified cardiovascular health metrics among 87,160 heterosexual couples using the health claims database from the Japan Medical Data Center. The ideal cardiovascular health metrics is comprised of (1) nonsmoking, (2) body mass index <25 kg/m 2 , (3) physical activity at goal, (4) untreated blood pressure <120/80 mm Hg, (5) untreated fasting glucose <100 mg/dL, and (6) untreated total cholesterol <200 mg/dL.

Results: A correlation was noted on the ideal modified cardiovascular health metrics between couples. The prevalence of meeting ≥ 5 ideal components in the female partners increased from 32 % in the male partners meeting 0–1 ideal component to 56 % in those meeting 6 ideal components. The same trend has been observed in all generations (20–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, ≥ 60 years). The association between couples is found to be better in terms of smoking status, blood pressure, and fasting glucose level.

Conclusion: There was an intracouple correlation of the ideal modified cardiovascular health metrics, suggesting the importance of couple-based intervention to improve cardiovascular health status.

Keywords: Couples, Cardiovascular health metrics, Preventive cardiology, Epidemiology

Introduction

Preventing the development of cardiovascular disease through the management of risk factors and lifestyle is always essential. To promote primary prevention, the American Heart Association (AHA) has defined cardiovascular health (CVH) based on seven risk factors and behaviors including smoking status, body mass index, physical activity, dietary habits, blood pressure, fasting glucose level, and total cholesterol level 1 , 2) . A number of clinical evidence have supported the validity of these CVH metrics. Yang et al. 3) have reported that higher values of CVH metrics were associated with a lower all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Therefore, measuring CVH metrics is a simple way to assess the risk of cardiovascular disease in each individual, which leads to establishing an effective prevention of subsequent cardiovascular disease. From this point of view, it is important to understand the determinants of CVH metrics.

Couples have common environmental and lifestyle habits, which can affect their individual health status. Therefore, if there is a significant intra-couple concordance in CVH metrics, it supports the concept of couple-based interventions for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. However, clinical data on the correlation of the CVH metrics among couples remain to be limited 4 , 5) . In this study, we sought to examine the relationship of CVH metrics in 87,160 couples using the nationwide epidemiological database.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This study is a retrospective observational cross-sectional analysis using the health claims database of the Japan Medical Data Center (JMDC; Tokyo, Japan), Tokyo, between January 2005 and December 2016 6 - 9) . The JMDC contracts with more than 60 insurers, and this includes data for health insurance claims on insured individuals, with more than 5 million individuals registered in it. Most insured individuals in the JMDC database are identified to be employees of relatively large Japanese companies 10) . The JMDC database is comprised of 1,529,893 individuals. Among these individuals, we extracted 253,001 couples based on the family identification number. We excluded 228 couples whose husband and/or wife were under the age of 20 at the first heath check-up, 129,985 couples that did not have enough data to calculate CVH metrics, and 35,628 couples whose intervals of the first health checkups between husband and wife were longer than 1 year. In total, we examined 87,160 couples in this study.

Ethics

We conducted this study in accordance with the ethical guidelines set by our institution (approval by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tokyo: 2018-10862) as well as with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived, as all data in the JMDC database were de-identified.

Definition

We modified the AHA definitions of ideal, intermediate, and poor CVH to fit our database. Table 1 presents these modified and original AHA definitions, which were used in this study. In the JMDC database, all CVH metrics data were found to be available, except for the diet metrics. The health check-up data used to assess CVH metrics were uniform and readily available as performing a regular health check-up is mandatory for most Japanese employees using a prescribed format and protocol.

Table 1. Definitions of ideal, intermediate, and poor cardiovascular health metrics.

| Cardiovascular health metrics | Definition of the AHA | Definition in our study |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | ||

| Ideal | Never or quit > 12 months ago | Never or Prior smoking |

| Intermediate | Former or quit ≤ 12 months | Not available |

| Poor | Current smoking | Current smoking |

| Body mass index | ||

| Ideal | <25 kg/m 2 | <25 kg/m 2 |

| Intermediate | 25 – 29.9 kg/m 2 | 25 – 29.9 kg/m 2 |

| Poor | ≥ 30.0 kg/m 2 | ≥ 30.0 kg/m 2 |

| Physical activity | ||

| Ideal | ≥ 150 min/week moderate or ≥ 75 min/week vigorous or ≥150 min/week moderate + vigorous | 30 minutes exercise equal or more than twice a week or Equal or more than one hour walk per day |

| Intermediate | 1 – 149 min/week moderate or 1 – 74 min/week vigorous or 1 – 149 min/week moderate + vigorous | Not available |

| Poor | None | None |

| Healthy diet score | ||

| Ideal | 4 - 5 components | Not available |

| Intermediate | 2 - 3 components | Not available |

| Poor | 0 - 1 components | Not available |

| Blood pressure | ||

| Ideal | SBP <120 and DBP<80 mmHg | SBP <120 and DBP<80 mmHg |

| Intermediate | SBP 120 – 139 or DBP 80 – 89mmHg or treated to goal | SBP 120 – 139 or DBP 80 – 89mmHg or treated to goal |

| Poor | SBP ≥ 140 or DBP ≥ 90mmHg | SBP ≥ 140 or DBP ≥ 90mmHg |

| Fasting plasma glucose | ||

| Ideal | <100 mg/dL | <100 mg/dL |

| Intermediate | 100 – 125 mg/dL or treated to goal | 100 – 125 mg/dL or treated to goal |

| Poor | ≥ 126 mg/dL | ≥ 126 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol | ||

| Ideal | <200 mg/dL | <200 mg/dL |

| Intermediate | 200 – 239 mg/dL or treated to goal | 200 – 239 mg/dL or treated to goal |

| Poor | ≥ 240 mg/dL | ≥ 240 mg/dL |

AHA, American Heart Association.

Ideal metrics were set as follows: ideal body weight was defined as BMI <25 kg/m 2 , ideal smoking was defined as not smoking (never smoked or prior smoker), and current smoker was defined as smoking ≥ 100 cigarettes or smoking duration ≥ 6 months. Physical activity was measured using a standardized questionnaire. Ideal physical activity was defined as 30 minutes exercise ≥ twice a week or ≥ 1 hour walk per day. Ideal blood pressure has been defined as untreated blood pressure of <120/80 mmHg. Ideal fasting plasma glucose was defined as untreated values of <100 mg/dL. Total cholesterol level was calculated using the low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride measurements. We defined the ideal total cholesterol as untreated values of <200 mg/dL. We calculated CVH metrics of each individual based on the data of their first health check-up.

Statistical Procedures

Categorical and continuous data of the baseline characteristics are presented as percentages (%) and means±standard deviation. The chi-square test was used to compare the categorical variables between men and women. Meanwhile, the unpaired t -test was used in comparing continuous variables between men and women. To evaluate the degree of concordance in ideal CVH variables between couples, we analyzed the percentage of concordant and discordant couples in four categories including man/woman both ideal, man/woman both not ideal, man ideal and woman not ideal, and man not ideal and woman ideal for each variable. We assessed the intra-couple association for each variable using the phi coefficient. We analyzed the difference in the percentage of ideal index between woman and man using ideal metrics of disagreement among couples. We calculated the odds ratios (ORs) using the logistic regression analysis. We then performed subgroup analysis in each generation (men aged 20–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, and ≥ 60 years). A probability value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We performed all statistical analyses using SPSS version 25 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Characteristics of Study Population

We analyzed 87,160 heterosexual couples in this study. The average age of participants was determined to be 51.5±9.5 years in men and 49.5±9.0 years in women. Distribution of the CVH metrics is shown in Table 2 . Women have reported to show better CVH status than men in all components.

Table 2. Distribution of the Cardiovascular Health Metrics.

| Cardiovascular health metrics | Total Sample ( N = 174,320) | Men ( n = 87,160) | Women ( n = 87,160) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | <0.001 | |||

| Ideal | 143,032 (82) | 61,003 (70) | 82,029 (94) | |

| Intermediate | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | |

| Poor | 31,288 (18) | 26,157 (30) | 5,131 (6) | |

| Body mass index | <0.001 | |||

| Ideal | 137,745 (79) | 63,004 (72) | 74,741 (86) | |

| Intermediate | 31,753 (18) | 21,490 (25) | 10,263 (12) | |

| Poor | 4,822 (3) | 2,666 (3) | 2,156 (2) | |

| Physical activity | <0.001 | |||

| Ideal | 83,000 (48) | 39,810 (46) | 43,190 (50) | |

| Intermediate | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | |

| Poor | 91,320 (52) | 47,350 (54) | 43,970 (50) | |

| Healthy diet score | ||||

| Ideal | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | |

| Intermediate | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | |

| Poor | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | |

| Blood pressure | <0.001 | |||

| Ideal | 83,263 (48) | 31,560 (36) | 51,703 (59) | |

| Intermediate | 67,903 (39) | 41,076 (47) | 26,827 (31) | |

| Poor | 23,154 (13) | 14,524 (17) | 8,630 (10) | |

| Fasting plasma glucose | <0.001 | |||

| Ideal | 130,064 (75) | 57,245 (66) | 72,819 (84) | |

| Intermediate | 37,697 (22) | 24,937 (29) | 12,760 (15) | |

| Poor | 6,559 (4) | 4,978 (6) | 1,581 (2) | |

| Total cholesterol | <0.001 | |||

| Ideal | 65,934 (38) | 32,313 (37) | 33,621 (39) | |

| Intermediate | 77,323 (44) | 40,494 (46) | 36,829 (42) | |

| Poor | 31,063 (18) | 14,353 (16) | 16,710 (19) | |

| Number of Ideal Cardiovascular Health Metrics | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 1,261 (1) | 1,163 (1) | 98 (0) | |

| 1 | 8,231 (5) | 6,428 (7) | 1,803 (2) | |

| 2 | 23,182 (13) | 16,468 (19) | 6,714 (8) | |

| 3 | 40,864 (23) | 24,821 (28) | 16,043 (18) | |

| 4 | 50,205 (29) | 23,137 (27) | 27,068 (31) | |

| 5 | 38,431 (22) | 12,298 (14) | 26,133 (30) | |

| 6 | 12,146 (7) | 2,845 (3) | 9,301 (11) |

Data are expressed as number (percentage).

Number of Ideal Cardiovascular Health Metrics

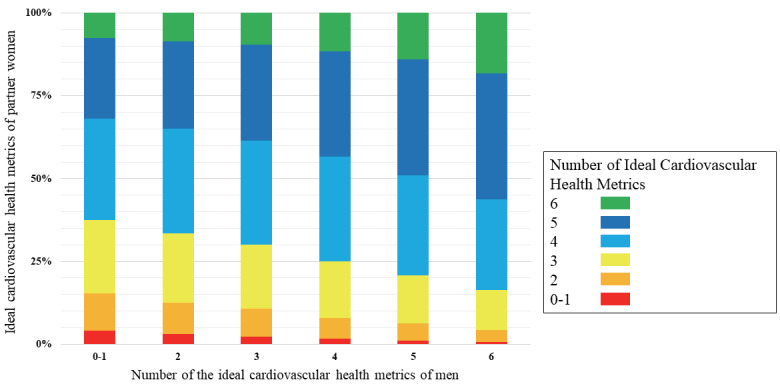

Fig.1 presents an intra-couple concordance in the number of ideal CVH metrics. The prevalence of meeting ≥ 5 ideal components of women increased from 32 % in spousal men meeting 0–1 ideal component to 56 % in those meeting 6 ideal components. The proportion of persons meeting ≥ 5 ideal components is shown in Table 3 . A man who meets ≥ 5 ideal components probably had a partner who meets ≥ 5 ideal components (odds ratio (OR) 1.6, 95 % CI 1.6–1.7, p <0.001).

Fig. 1. Correlation of the ideal modified cardiovascular health metrics between couples .

Fig. 1 shows an intra-couple concordance in the number of ideal cardiovascular health metrics between couples.

Table 3. Proportion of Subjects Meeting ≥ 5 Ideal Components.

| Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Women | No | 44,204 (50.7%) | 7,522 (8.6%) |

| Yes | 27,813 (31.9%) | 7,621 (8.7%) | |

Subgroup Analysis

A similar trend of intra-couple concordance in the number of ideal CVH metrics is observed in all generations including men aged 20–39 years ( n = 7,471) (Fig.2A) , 40–49 years ( n =31,791) (Fig.2B) , 50–59 years ( n =26,426) (Fig.2C) , and ≥ 60 years ( n =21,472) (Fig.2D) . A man who meets ≥ 5 ideal components probably had a partner who meets ≥ 5 ideal components in men aged 20–39 years (OR 1.4, 95 % CI 1.3–1.6, p <0.001), 40–49 years (OR 1.3, 95 % CI 1.3–1.4, p <0.001), 50–59 years (OR 1.4, 95 % CI 1.3–1.5, p <0.001), and ≥ 60 years (OR 1.3, 95 % CI 1.2–1.5, p <0.001).

Fig. 2. Subgroup analysis on correlation of the ideal modified cardiovascular health metrics between couples .

Fig. 2 presents an intra-couple concordance in the number of ideal cardiovascular health metrics between couples among all generations including men aged 20–39 years (Fig. 2A), 40–49 years (Fig. 2B), 50–59 years (Fig. 2C), and ≥ 60 years (Fig. 2D).

Association of each Cardiovascular Health Metrics Component Between Couples

Fig.3 presents the association of each CVH metrics component between couples. The phi coefficient showed that intracouple association was better in terms of smoking status, blood pressure, and fasting glucose level. Women have met ideal metrics of disagreement between couples.

Fig. 3. Intra-couple association of each cardiovascular health metrics component .

Fig. 3 indicates the association between couples for each cardiovascular health metrics component.

Discussion

There are three major findings in this study. First, there was an intra-couple association of the ideal modified CVH metrics. Second, the prevalence of meeting ≥ 5 ideal components of the woman partners increased from 32% in the man partners meeting 0–1 ideal component to 56% in those meeting 6 ideal components. Third, the phi coefficient indicated that the intracouple association was better in terms of smoking status, blood pressure, and fasting glucose level.

CVH metrics are seen to aid in the risk stratification of subsequent cardiovascular diseases. Previous studies have shown an association between CVH metrics and the risk of cardiovascular event 3 , 11 , 12) . Folsom et al. 11) have examined the data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study cohort and showed that persons with the highest values of CVH metrics experienced few cardiovascular events including stroke, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and fatal coronary disease. Further, Kim et al. 13) recently reported that a higher ideal CVH metrics score was associated with a lower prevalence of calcification in the coronary artery, accompanied with slower progression of coronary artery calcification in apparently healthy adults, suggesting the importance of CVH metrics in preventive cardiology.

Previous studies examining couples (spousal and cohabitating) support our findings 14 - 17) . For instance, Knuiman et al. 14) have identified statistically significant positive correlations in terms of blood pressure, body mass index, and cholesterol between couples. Di Castelnuovo et al. 17) also studied the spousal concordance for major coronary risk factors and reported that the most strongly correlated intra-couple risk factors were smoking and body mass index. Statistically significant correlations were also found for diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides, and total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. After comparing with the previous reports, we reasoned that CVH metrics were concordant between couples.

Two studies focusing on intra-couple concordance of CVH metrics were reported previously 4 , 5) . First was the study of O’ Flynn et al. 4) , who examined 181 couples in a single center in Ireland and presented an intra-couple concordance in ideal CVH metrics. Second was the study of Erqou et al. 5) , who studied 231 couples using a community-based cohort in western Pennsylvania and also reported the same findings. The results of our study were found to be concordant with these studies, and intra-couple association of CVH metrics was confirmed in our study as well.

The strength of our study is its large sample size. As described above, two preceding studies are based on single center or local community data and, therefore, had small sample sizes. However, considering the variety and heterogeneity of lifestyles and behaviors, we believe that examining the intra-couple concordance of CVH metrics using a nationwide large-scale database is resourceful. In this study, we also conducted a subgroup analysis and found out that a correlation of CVH metrics between couples may exist irrespective of age. The effect of age on the association of CVH metrics between couples is seemingly not so large.

The association between couples is better in the component of smoking, blood pressure, and fasting glucose level. Regarding smoking habits, it should be noted that the disagreement ratio is at 29%. These couples should be aware of the risk of passive smoking. Given that blood pressure and fasting glucose level are strongly affected by dietary habits, it is also reasonable that there was a good association between couples for these components. Our findings confirm that couple-based lifestyle assessment and interventional strategy have potentials for application in preventive cardiology. In addition, the number of ideal CVH metrics of men was lower than that of women. This may contribute to the gender difference in cardiovascular risks. Preventive interventions targeting couples may contribute to the reduction of the higher cardiovascular risk in men.

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, the data of the JMDC database were mainly obtained from an employed, working-age population. Therefore, “healthy worker” bias should be recognized. Second, as noted above, the JMDC database did not have any records of diet information. Diet is thought to be the most frequently shared between cohabitating couples, and maintaining optimal diet habit is important for preventing metabolic disorders and cardiovascular disease 18 , 19) . However, analysis of the effects of dietary habits was impossible due to the unavailability of data. Further research is required to assess the influence of dietary habits on CVH metrics scores. Third, we did not have the information on the duration of marriage and whether couples live together. These can affect intra-couple association of the CVH metrics. As described in the Methods section, we identified couples in the JMDC database using family identification number which was given to all individuals enrolled in the JMDC database. Therefore, if husband and wife joined different health insurance, such couple was not identified as couples and not included in this study. Intra-couple association of the CVH metrics would change if we could include couples joining different health insurance. The number of couples in men aged 20–39 years is relatively small. It may reflect the current social situation in Japan, such as late marriage and rising unmarried rate among young people. Further data on younger age couples are needed.

Conclusion

Our analysis of a nationwide epidemiological data showed an association of CVH metrics between 87,160 heterosexual couples. The results of this study may support the concept of couple-based intervention for improving CVH status.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (19AA2007 and H30-Policy-Designated-004) and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (17H04141).

Disclosures

Research funding and scholarship funds (Hidehiro Kaneko and Katsuhito Fujiu) from Medtronic Japan CO., LTD, Abbott Medical Japan CO., LTD, Boston Scientific Japan CO., LTD, and Fukuda Denshi, Central Tokyo CO., LTD. All authors have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1).Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J, American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2010; 121: 948-954 [Google Scholar]

- 2).Gaye B, Tajeu GS, Offredo L, Vignac M, Johnson S, Thomas F, Jouven X. Temporal trends of cardiovascular health factors among 366,270 French adults. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Yang Q, Cogswell ME, Flanders WD, Hong Y, Zhang Z, Loustalot F, Gillespie C, Merritt R, Hu FB. Trends in cardiovascular health metrics and associations with all-cause and CVD mortality among US adults. JAMA, 2012; 307: 1273-1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).O’Flynn AM, McHugh SM, Madden JM, Harrington JM, Perry IJ, Kearney PM. Applying the ideal cardiovascular health metrics to couples: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Clin Cardiol, 2015; 38: 32-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Erqou S, Ajala O, Bambs CE, Althouse AD, Sharbaugh MS, Magnani J, Aiyer A, Reis SE. Ideal Cardiovascular Health Metrics in Couples: A Community-Based Study. J Am Heart Assoc, 2018; 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Goto A, Goto M, Terauchi Y, Yamaguchi N, Noda M. Association Between Severe Hypoglycemia and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Japanese Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. J Am Heart Assoc, 2016; 5: e002875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Wake M, Onishi Y, Guelfucci F, Oh A, Hiroi S, Shimasaki Y, Teramoto T. Treatment patterns in hyperlipidaemia patients based on administrative claim databases in Japan. Atherosclerosis, 2018; 272: 145-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Kawasaki R, Konta T, Nishida K. Lipid-lowering medication is associated with decreased risk of diabetic retinopathy and the need for treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes: A real-world observational analysis of a health claims database. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2018; 20: 2351-2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Davis KL, Meyers J, Zhao Z, McCollam PL, Murakami M. High-Risk Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in a Real-World Employed Japanese Population: Prevalence, Cardiovascular Event Rates, and Costs. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2015; 22: 1287-1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Michihata N, Shigemi D, Sasabuchi Y, Matsui H, Jo T, Yasunaga H. Safety and effectiveness of Japanese herbal Kampo medicines for treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2019; 145: 182-186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Rosamond WD, Investigators AS. Community prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, by the American Heart Association definition, and relationship with cardiovascular disease incidence. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2011; 57: 1690-1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Lachman S, Peters RJ, Lentjes MA, Mulligan AA, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT, Boekholdt SM. Ideal cardiovascular health and risk of cardiovascular events in the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2016; 23: 986-994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Kim S, Chang Y, Cho J, Hong YS, Zhao D, Kang J, Jung HS, Yun KE, Guallar E, Ryu S, Shin H. Life’s Simple 7 Cardiovascular Health Metrics and Progression of Coronary Artery Calcium in a Low-Risk Population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2019; 39: 826-833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Knuiman MW, Divitini ML, Bartholomew HC, Welborn TA. Spouse correlations in cardiovascular risk factors and the effect of marriage duration. Am J Epidemiol, 1996; 143: 48-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Meyler D, Stimpson JP, Peek MK. Health concordance within couples: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med, 2007; 64: 2297-2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Di Castelnuovo A, Quacquaruccio G, Arnout J, Cappuccio FP, de Lorgeril M, Dirckx C, Donati MB, Krogh V, Siani A, van Dongen MC, Zito F, de Gaetano G, Iacoviello L, European Collaborative Group of IP. Cardiovascular risk factors and global risk of fatal cardiovascular disease are positively correlated between partners of 802 married couples from different European countries. Report from the IMMIDIET project. Thromb Haemost, 2007; 98: 648-655 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Di Castelnuovo A, Quacquaruccio G, Donati MB, de Gaetano G, Iacoviello L. Spousal concordance for major coronary risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol, 2009; 169: 1-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Maruyama C, Nakano R, Shima M, Mae A, Shijo Y, Nakamura E, Okabe Y, Park S, Kameyama N, Hirai S, Nakanishi M, Uchida K, Nishiyama H. Effects of a Japan Diet Intake Program on Metabolic Parameters in Middle-Aged Men. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2017; 24: 393-401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Shijo Y, Maruyama C, Nakamura E, Nakano R, Shima M, Mae A, Okabe Y, Park S, Kameyama N, Hirai S. Japan Diet Intake Changes Serum Phospholipid Fatty Acid Compositions in Middle-Aged Men: A Pilot Study. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2019; 26: 3-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]