Abstract

Experimental exposure of early life stage bivalves has documented negative effects of elevated pCO2 on survival and growth, but the population consequences of these effects are unknown. Following standard practices from population viability analysis and wildlife risk assessment, we substituted laboratory-derived stress-response relationships into baseline population models of Mercenaria mercenaria and Argopecten irradians. The models were constructed using inverse demographic analyses with time series of size-structured field data in NY, USA, whereas the stress-response relationships were developed using data from a series of previously published laboratory studies. We used stochastic projection methods and diffusion approximations of extinction probability to estimate cumulative risk of 50% population decline during ten-year population projections at 1, 1.5 and 2 times ambient pCO2 levels. Although the A. irradians population exhibited higher growth in the field data (12% per year) than the declining M. mercenaria population (−8% per year), cumulative risk was high for A. irradians in the first ten years due to high variance in the stochastic growth rate estimate (log λs = −0.02, σ2 = 0.24). This ten-year cumulative risk increased from 69% to 94% and >99% at 1.5 and 2 times ambient scenarios. For M. mercenaria (log λs = −0.09, σ2 = 0.01), ten-year risk was 81%, 96% and >99% at 1, 1.5 and 2 times ambient pCO2, respectively. These estimates of risk could be improved with detailed consideration of harvest effects, disease, restocking, compensatory responses, other ecological complexities, and the nature of interactions between these and other effects that are beyond the scope of available data. However, results clearly indicate that early life stage responses to plausible levels of pCO2 enrichment have the potential to cause significant increases in risk to these marine bivalve populations.

Keywords: ocean acidification, coastal acidification, bivalves, matrix model, inverse demography, population

1. Introduction

Atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions have risen to over 400 μatm, exceeding levels occurring in the past one million years. Current emission scenarios predict that CO2 concentrations may rise above 1000 μatm by the end of the century (IPCC 2013). The absorption of this rising CO2 by the oceans has caused ocean acidification and associated shifts in marine carbonate chemistry, including a decrease in pH, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) saturation state (Ω), and carbonate ion concentration (CO32-) (Cao and Caldeira 2008). While atmospheric loading of CO2 drives open ocean acidification, acidification in coastal zones is often controlled by additional processes, including eutrophication (Feely et al. 2010, Cai et al. 2011, Mucci et al. 2011, Wallace et al. 2014). Specifically, excessive nutrient loading into coastal ecosystems results in the accumulation of algal biomass followed by microbial degradation. Especially when coupled with seasonal stratification, this can create regions of low oxygen, high CO2, and acidification (Borges and Gypens 2010, Wallace et al. 2014). During the past decade, there have been numerous studies documenting the negative effects of altered carbonate chemistry on calcium carbonate-producing marine organisms (Orr et al. 2005, Kroeker et al. 2010, Doney et al. 2009). Some of the most sensitive of these organisms are early life stage bivalves (Green et al. 2009, Talmage and Gobler 2009, Gazeau et al. 2013; Waldbusser et al. 2013).

Laboratory studies have demonstrated that low pH and high pCO2 (partial pressure of carbon dioxide) reduce the survival and growth of the early life stages of filter feeding bivalves that are of commercial importance on the east coast of North America. Two of these are the hard clam, Mercenaria mercenaria, and the bay scallop, Arogopecten irradians (Green et al. 2009, Gobler and Talmage 2013, Talmage and Gobler 2009, 2010, 2011). Talmage and Gobler (2009, 2010, 2011) measured the survival of larval M. mercenaria and A. irradians in laboratory experiments under CO2 levels expected in surface oceans later this century and beyond (1500 μatm), although these shellfish often experience CO2 levels already this high in estuaries during the summer (Wallace et al. 2014). Throughout the summer, many temperate coastal systems are at the peak of their net heterotrophy and thus water can be supersaturated with CO2 (Blight et al. 1995, Talmage and Gobler 2009, Melzner et al. 2013). This is also the period during which larval M. mercenaria and A. irradians are spawned (Kennedy and Krantz 1982, Bricelj et al.1987). Miller and Waldbusser (2016) found that high variability in calcium carbonate mineral saturation state such as those experienced by these two bivalves can affect post-larval stage duration and therefore increase mortality rates. They did not estimate population level growth rates presumably because a suitable population model into which the impairment could be substituted was not available. Thus, although high mortality rates in the larval stage likely result in decreases in population fitness, further scrutiny within the context of whole life cycles is clearly needed.

A. irradians and M. mercenaria populations co-occur along the east coast of North America but have distinctly different life history strategies and habitat use. A. irradians is typically found among eelgrass beds and sandy substrates, reaches maturity at age one, spawns during summer and fall when seawater temperatures range from 20–24°C, and has a lifespan of 20–26 months (Shumway and Parsons 2011, Tettelbach et al. 1999). A. irradians is also one of the few bivalve species that does not live buried in the sand or attached to rocks but instead moves freely along benthic habitats. In contrast, M. mercenaria buries itself just below the surface of the sediment, typically reaches physiological maturity after two years and peak reproductive output at 7 – 12 years (Hofmann et al. 2006), can spawn multiple times per year when water reaches the optimal temperature (20 – 24°C), and may live up to forty years (Kraeuter and Castagna 2001). Both bivalves are commercially important. Despite the extirpation of many populations, M. mercenaria landings in the US were ~$57M in 2016, while A. irradians annual landings were ~$3M (Commercial Fisheries Statistics 2016). Beyond their direct harvest value, both species are considered ecosystem engineers in coastal waters due to their putative ability to mitigate eutrophication through filter feeding (Officer et al. 1982, Newell 2004, Pomeroy et al. 2006).

While it is known that high levels of CO2 affect individuals or same-aged cohorts of early life stage marine bivalves in the laboratory (Gazaeu et al. 2013), the population-level and ecological consequences of acidification are poorly understood. This is primarily because the magnitude of an organismal response is rarely predictive of effects at the population level. Since knowledge about the full life cycle in the form of vital demographic statistics is required to address this problem, common practice is to glean or derive those vital rates from disparate biological studies and then assemble them into a synthetic model. For a variety of reasons, this can produce extremely unrealistic life history models without the trade-offs and correlations that typically exist among vital rates in natural populations. For example, it would be problematic to combine a fertility estimate from a high-latitude population and a survival estimate from a low latitude population into a single model. We address this problem by estimating all the parameters for each model simultaneously from a single set of observations of an intact wild population. The approach is described by Grear et al. (2011) and others (reviewed in Caswell 2001) and involves an inverse demographic method requiring only stage- or age-structured time series of population abundance and sufficient natural history knowledge to formulate a basic model structure. In brief, our application treats the observed age/stage abundances as a multivariate time series to which a set of linear equations in the form of a demographic transition matrix are fitted using maximum likelihood.

Knowledge about biological responses to increased pCO2 usually comes from controlled laboratory studies of isolated life stages. This is mainly because impairments of a specific vital rate (e.g., survival of a specific life stage) are often impossible to measure directly in mixed-age populations. Thus, age cohorts are typically isolated and exposed, and then responses are tracked. These responses are then substituted into demographic population models such as those discussed above to assess higher-level effects. This approach has problems resulting from the effects of cohort isolation on biological response (Grear et al. 2011), but it is standard practice in assessments of population viability (Morris and Doak 2002; Beissinger and Westpahl 1998; Caswell 2001). Although not yet common in the study of ocean and coastal acidification, this was the approach we used for incorporating pCO2 effects on bivalve early life stages into population models of A. irradians and M. mercenaria.

The overarching goal of this study was to scale the impacts of elevated pCO2 (800 and 1200 μatm) on early life stages to population response, which we de fined as the probability of 50% decline in total population size. No pCO2 impairment of juveniles or adults was considered in the scenarios. As described below, our analysis required the use of stochastic modeling techniques and diffusion approximations of population trajectories (Dennis et al. 1991, Caswell 2001, Morris & Doak 2002, Lande et al. 2003). Our combination of field population data, inverse demographic estimation, substitution of stress-response relationships developed from previous laboratory experiments, and conventional population-level risk analysis allowed us to estimate changes in risk to northeast marine bivalve populations associated with the effects of future increases in pCO2 on early life stage survival.

2. Methods

2.1. Bivalve Population Data

Although abundance data exist for M. mercenaria and A. irradians in many ecosystems, the data for our study had to meet several criteria to be suitable for inverse demographic models (IDMs; Grear et al. 2011, Caswell 2001, Wood 1994). First, abundance for age or size classes was needed for a minimum of three consecutive surveys evenly spaced in time. For time series with transient departures from the expected stable age/stage distribution, longer time series are needed. In addition, the method treats the survey period as a window of time during which a single set of stochastically varying survival and reproductive rates is sufficient to capture the population dynamics.

For the M. mercenaria analysis, we used data from the Town of Islip, NY, which conducted an annual fishery-independent grab-sampling survey in Great South Bay (GSB) NY from 1977 – 2011 (Table 1; Joseph 1989, Hofmann et al. 2006, Kraeuter et al. 2008). GSB is a small (383 km2), shallow lagoonal estuary (mean depth ~2m) located on the south shore of Long Island, NY (Schubel et al. 1991), that varies greatly in its physiochemical properties (pHNBS range= 6.7 – 9.4 mean = 8.03 ± 0.27 sd, dissolved oxygen range = 0.3–13.4 mg/L, mean = 8.17 ± 2.47 mg/L, salinity range = 7.1 – 32.2 mean = 28.32 ± 2.87; SCDHS 2015). GSB is reported to have an overall moderately high eutrophication condition with high levels of chlorophyll-a, macroalgae, and recurrent harmful algal blooms caused by Aureococcus anophagefferens (Bricker et al. 2007, Kinney and Valiela 2011, Gobler and Sunda 2012). M. mercenaria in GSB were classified into four size classes based on commercial harvesting sizes of shell width (seed = 2 – 25mm, little neck = 26 – 37mm, cherrystone = 38 – 42mm, chowder ≥ 43mm) from which matrix parameters could be estimated with inverse demography (Fig. 1). Counts were reported as individuals m-2.

Table 1.

Site names and locations for the Mercenaria mercenaria and Argopecten irradians data sets. M. mercenaria data were collected by the Town of Islip, NY, using grab samples (1977–2001) and reported as clams m–2 (Hofmann et al. 2006, Kraeuter et al. 2008). A. irradians data were from multiple 1 × 50 m scuba transects per year collected in spring (2005–2014) as described by Tettelbach et al. (2015)

| Location | Coordinates (°N, °W) |

|---|---|

| M. mercenaria | |

| Great South Bay, Islip, NY | |

| A. irradians | |

| Flanders Bay | |

| S of Red Cedar Pt | 40°54.783’, 72° 34.023’ |

| Cow Yard | 40°55.026’, 72° 35.118’ |

| North Side | 40°55.719’ 72° 36.325’ |

| Hallock Bay | |

| Narrow River | 41°08.197’, 72° 16.840’ |

| Bulkhead | 41°08.251’, 72° 16.396’ |

| Central Flats | 41°07.951’, 72° 16.389’ |

| South Channel | 41°07.766’, 72° 16.273’ |

| Other | 41°06.301’, 72° 19.552’ |

| Northwest Harbor | |

| Sag Harbor | 41°00.410’, 72° 17.419’ |

| Barcelona Neck | 41°00.873’, 72° 15.389’ |

| SWG | 41°01.806’, 72° 14.596’ |

| Inshore Cedar Point | 41°02.251’, 72° 15.416’ |

| Orient Harbor | |

| East Marion | 41°07.714’, 72° 19.641’ |

| Peter’s Neck | 41°07.697’, 72° 17.521’ |

| Inside Long Beach | 41°07.352’, 72° 17.532’ |

| Outside Long Beach | 41°06.766’, 72° 17.682’ |

| Hay Beach | 41°06.308’, 72° 19.555’ |

| Greenport Jetty | 41°06.347’, 72° 20.892’ |

| Great Peconic Bay | |

| Robins Island North | 40°58.989’, 72° 27.811’ |

| Robins Island West | 40°57.704’, 72° 28.190’ |

| Mattituck | 40°57.609’, 72° 31.924’ |

| Southold Bay | 41°03.966’, 72° 24.203’ |

| Hog Neck Bay | 41°01.610’, 72° 24.110’ |

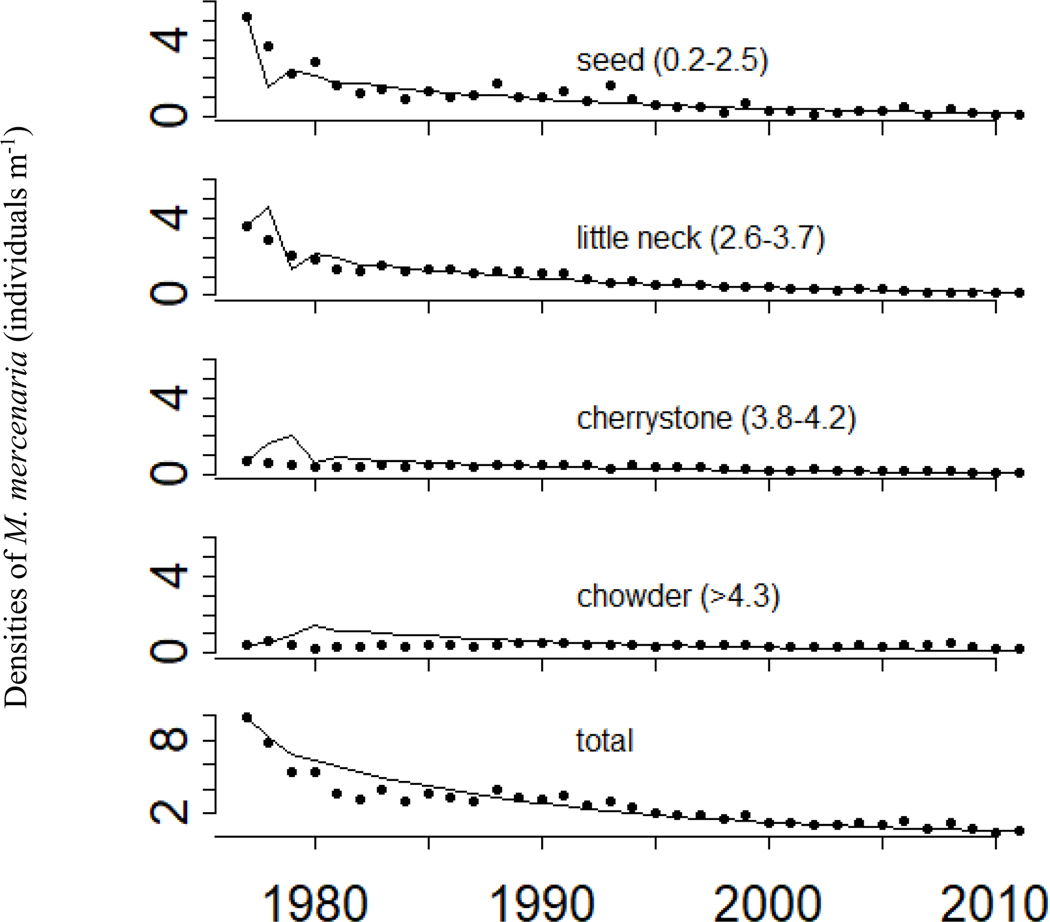

Figure 1.

Observed (points) and projected (lines) densities by stage for the Islip, NY, Mercenaria mercenaria population of Great South Bay. Projections are matrix projections from the initial population state

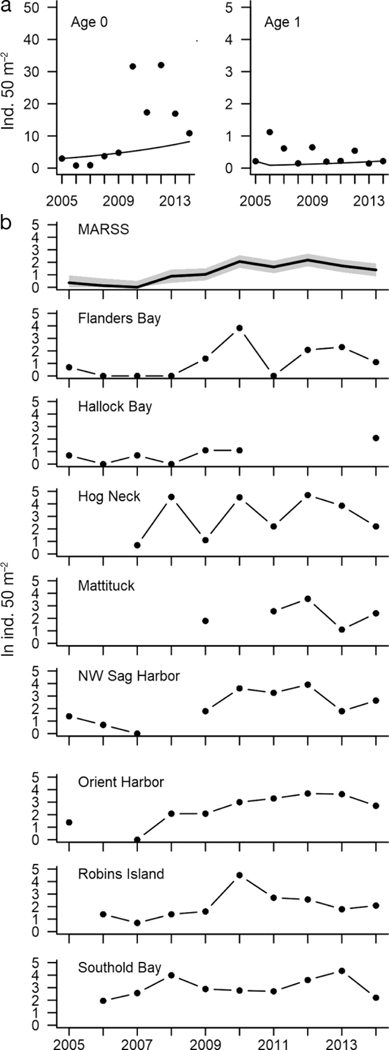

A. irradians irradians data were obtained from surveys conducted during spring of each year at several locations in the Peconic Estuary on the east end of Long Island, NY (Table 1; Tettelbach et al. 2015) from 2005 to 2014. Sites included in the analysis in this study were Flanders Bay, Hallock Bay, Northwest Harbor, Sag Harbor, Orient Harbor, Southold Bay, Hog Neck Bay and Great Peconic Bay. The Peconic Estuary is a tidally well-mixed estuary with conditions typical of a mesotrophic estuary (pHNBS range= 7.8–8.2 mean = 8.0 ± 0.16, dissolved oxygen range = 170 – 380 μM, mean = 250 ± 60 μM, salinity range = 24.6–30.8 mean = 28.1 ± 1.34; SCDHS 2017). Its depth ranges from 2 m on the west to 25 m on the east. Data were collected in an age-based survey throughout the spring (March to June) where multiple 1 m x 50 m transects were completed at each site for each year (Table 1). Data for this short-lived bivalve species (two years) were divided into age class 0 (offspring produced the summer or fall before the survey) and age class one (individuals alive during the previous year’s survey) and were reported in the original data as individuals m-2. After testing for site-specific dynamics (see below), the analysis focused on rates at the landscape level (rather than individual sites), so we did not attempt to account for immigration and emigration at individual sites.

2.2. Baseline Demographic Matrix Models

We used inverse demography to estimate population matrix models from field data. Demographic matrix models are commonly used by population ecologists, but we summarize them briefly here. Typically, the individuals are classified into discrete age, stage, or size intervals. Here, size-based models were used, with the abundances within each size or age class forming the population state vector. The matrix contains the vital rates that describe the transitions between these classes (e.g. survival, growth, birth) during 1 annual interval.

Field-based matrix models for the 2 study species were estimated from existing bivalve field surveys using IDMs, which treat the age- or size-abundance for each year as a stochastic realization of a multivariate process (Dennis et al. 1995, Grear et al. 2011). The estimation method represents this multivariate process as a set of linear algebraic equations (i.e. the rows in the matrix model) and seeks to identify the set of matrix parameters that maximizes the fit between the predicted and observed stage abundances using likelihood methods (joint probability of the observed data given the model; Dennis et al. 1995). The method eliminates the ‘synthetic matrix’ problem discussed above but does have limitations. Conceivably, there are multiple model solutions that could accurately describe the observed data, but most are eliminated when biologically plausible constraints are imposed (e.g. all transitions must be non-negative, survival rates cannot exceed 1.00, terms below row 1 but above the diagonal must be 0 since large individuals cannot transition into small ones).

We treated the fitted matrix models as baseline cases into which we would substitute biological responses from Talmage and Gobler (2009, 2010, 2011) and Gobler and Talmage (2013). For M. mercenaria, the baseline model represents the dynamics of a depleted population (Kraeuter et al. 2008), whereas the model for A. irradians is for a recovering population (Tettelbach et al. 2013, 2015). Female M. mercenaria in the little neck size class and above produce eggs (Bricelj and Malouf 1980), so the model took the following form:

| (Equation 1) |

| (Equation 2) |

where Fi is per capita fertility for size i individuals, which can be decomposed into a product of the number of offspring (spat) produced by adults right after the census and their probability of survival to the next annual census (P0). Pi is the probability of survival from size i to size i+1 in one census interval, PA is the survival probability for adults of size 4 and above, and nt is the population vector (size abundances) at time t. We reduced the number of free parameters in the model by relying on the study of M. mercenaria fecundity in Great South Bay by Bricelj and Malouf (1980), which found that fecundity of little necks was ~40% of the mean of cherrystone and chowder clams and that the fecundity of cherrystone and chowder clams were statistically indistinguishable. These relationships were used as optimization constraints in the model fitting process described below (F2 <= 0.4 × F3; F3 = F4) but the magnitudes of the fertilities were only constrained to be > 0. This approach assumes similar fertilization success and larval survival among the three parental size classes.

Although A. irradians irradians can live for two years or more (Tettelbach et al. 1999), two-year-olds were rare in the Peconic Estuary surveys that we used to construct the model. Also, there is evidence of fall spawning events in NY for A. irradians irradians (Tettelbach et al. 1999), but the fall set is smaller and presumably less important in Peconic Bay than in other populations (e.g., Hall et al. 2015). New cohort numbers were low in most fall surveys at the study sites (Tettelbach unpublished data). During the spring surveys used, there were two generations present (0 and 1 year-olds), but this overlap did not span an entire annual cycle. Since the age 0 class replaces the age 1 class by the next annual survey, the observed population can be modeled with non-overlapping generations. In this case, population growth is simply the replacement rate of the age 0 class. This leads to the following formulation for A. irradians:

| (Equation 3) |

to be substituted into Eq. (2) along with the 2-element population vector n. F is the contribution of offspring to the next survey by offspring counted at the current survey and p0 is the survival of age 0 individuals at the present survey to age 1 in the next survey. In this formulation, the fertility term (F ) is also equal to the population growth rate (λ) and is the product of spat produced after the survey (m) and their annual survival to the next survey, which we assume to be equal to age 0 survival (p0). The estimate for maternity rate (m) thus becomes m = F / p0. The parameters in this matrix for A. irradians (Eq. 3) were estimated in the same manner as described for M. mercenaria using inverse demography.

In the fitting process for the IDMs, the bivalve populations were projected forward in time from the observed population state at time t (Equations 2 and 4) and the residual in log space was calculated between the projected and observed values at t+1 to determine the likelihood of the data given the set of candidate parameters in matrix A. The candidate values where this likelihood is largest (i.e., the maximum likelihood estimates) and their standard errors were computed using likelihood profile methods (Pawitan 2013). Further details of this IDM approach are given in Grear et al. (2011); an application to marine crustaceans is described in Grear (2016). After estimating the matrix model, we computed population growth rate (λ), defined as the dominant right eigenvalue and, for the more complex M. mercenaria model, performed elasticity analysis to assess the effect of small proportional perturbations of each matrix parameter on λ (Caswell 2001).

To assess whether the multi-site data for A. irradians should be aggregated and treated as a single population time series in our risk projections, we conducted an additional analysis using multivariate autoregressive state-space models (MARSS), as developed and implemented in the R package MARSS by Holmes et al. (2012, 2013). In state-space models, the process of interest x (t), population growth in this case, is obscured from the observer, such that the observations y (t) incorporate a hidden process and an observation process, both of which have their own Gaussian errors (i.e., MVN = multivariate normal). The hidden and observational processes can be summarized on the natural log scale as:

| (Equation 4) |

| (Equation 5) |

where x and y are vectors with the elements representing each size class. The hidden process x (i.e., bivalve scalar abundance trend) is affected by u (e.g., population growth) and process error w, which can result from environmental and/or demographic stochasticity and has mean = 0 and variance-covariance matrix Q among the multiple time series. Layered on top of this is the observational process y, which may have a consistent offset (not shown) plus observation error v with mean = 0 and variance-covariance structure R. The MARSS package uses recursive time series methods (i.e., the Kalman filter) to separate these processes and allows the user to compare evidence for differing processes and error structures R and Q using information-theoretic methods via AIC (Akaike Information Criterion; Burnham and Anderson 2004). A MARSS model using the T = 10-yr time series from each of n = 8 sites (transects were averaged within each of the 8 sites, Table 1) was fit to the A. irradians data from Peconic Estuary (details for sites in Tettelbach et al. 2015). Of the n x T = 80 possible abundance estimates, there were 9 missing values and 5 zero values. As is typical in population time series analysis, the log transformation of the counts served to normalize the error distribution but resulted in the conversion of the 5 zero counts to missing values.

Our primary question concerning population growth in the MARSS analysis was whether there was support for using a single A. irradians population growth rate across all sites. Four different MARSS models were fitted to these multivariate data (Table 2). Differences between models included constant vs. site-specific variance in observation error and constant vs site-specific population growth rate and process error variance. We compared the population growth rate from the most parsimonious of these models (based on AIC) to the growth rate estimated from the same data using IDM. We did not perform this analysis for the M. mercenaria data, which consisted of a single time series of size-abundance.

Table 2.

Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) results for multivariate auto regressive state-space models fitted with the ‘MARSS’ package (R Core Team 2017, Holmes et al. 2012, 2013). Candidate models differ in terms of constraints on the population growth process and ob servation error. k: number of parameters in each model; ΔAICc: AIC corrected for small sample size and rescaled to the smallest AICc value

| Model | Process trend and variance | Observational error variance | ln Likelihood | k | ΔAICc | AICc weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | constant | constant | −88.34 | 11 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | constant | site-specific | −84.02 | 18 | 15.03 | 0.00 |

| 3 | site-specific | constant | −90.02 | 25 | 58.97 | 0.00 |

| 4 | site-specific | site-specific | −83.15 | 32 | 90.73 | 0.00 |

We tested for density dependence in both populations using methods described by Dennis & Taper (1994). Specifically, we fitted their Model 1 (stochastic exponential) and Model 2 (stochastic-logistic) to the time series of annual totals and then compared them via corrected AIC (AICc; Burnham & Anderson 2002):

| (6) |

| (7) |

where Xt is the log of the total abundance at time t (Nt), σ is the SD of the transitions in Xt, and Zt is a normally distributed random variate with zero mean and unit variance. Exponential growth is captured by a (on the log scale); the effect of density on growth is captured by b (<0 in the case of negative density dependence). AICc was computed from the likelihood formulation given as Eq. (15) in Dennis & Taper (1994; also see applications in Morris & Doak 2002 and Grear et al. 2009). Based on these analyses (see Section 3), we determined that neither of the bivalve matrix population models should incorporate density dependence.

2.3. Assessing Impairment of Wild Populations due to pCO2

Following the estimation of wild population matrices, the next step was to determine what levels of pCO2 impairment to substitute into the models. This was done using results from laboratory response experiments with early life stages (larval and in some cases early post-larval up to 40 d in total age since hatching) of M. mercenaria and A. irradians, as described by Talmage & Gobler (2009, 2010, 2011, 2012), Gobler & Talmage (2013), and Gobler et al. (2014). These experiments involved varying sample sizes and durations (usually <40 d). Among the various studies, there were 16 pCO2 treatment levels for M. mercenaria and 15 for A. irradians. Rounding to the nearest 50 μatm, the levels for M. mercenaria (and the number of experiments that used them) can be grouped as 200 (1), 250 (1), 350 (1), 400 (4), 500 (1), 600 (1), 650 (1), 700 (1), 750 (2), and 1500 μatm (3) (note that the raw treatment levels were used in the regressions described below). For A. irradians, these values were 250 (3), 350 (2), 400 (2), 450 (1), 700 (1), 750 (2), 850 (1), 1400 (1), 1550 (1), and 1600 (1) μatm. All experiments were initiated with larvae spawned from broodstock local to the field survey areas. Survival responses were determined from the proportion of total individuals surviving at each time point.

We fitted logistic regressions of survival against both pCO2 and day of observation during the survival trials to determine the impairment as a function of pCO2 for both species. Replicate responses at each pCO2 level within each experiment, as well as sample sizes (i.e., the number of individuals in binomial trial replicates) were pooled into mean survival and total sample size per treatment, respectively, for each experiment. This allowed weighting of the logistic regression according to the size of each experiment.

Substitution of these laboratory-derived responses into the field-based population models required some important assumptions. First, we assumed that early life stage responses to a proportional increase above ambient pCO2 in the experiments (i.e., proportion = elevated pCO2 treatment / control pCO2) would be indicative of responses to a similarly proportional increase in pCO2 above diurnally varying and occasionally supersaturated in situ pCO2 conditions. Secondly, we assumed mean in situ pCO2 levels were 350 μatm for M. mercenaria and 400 μatm for A. irradians due to the timing of the surveys and the approximate associated pCO2 levels for the late 1900s and 2005–2014, respectively. We then defined early life stage duration as 40 days. The proportional change in survival to this age per unit pCO2 change from baseline pCO2 became the value from the laboratory studies we integrated as an impairment factor into the population models. In cases where the duration of an experiment was not exactly 40 days, this approach necessitated extrapolation to 40 days using the assumption that daily mortality from the end of the experiment to 40 days was constant. The effect of this assumption on the estimation of population growth rate is proportional to the curvature (second order derivative) of the actual lifetime survivorship curve (Grear and Elderd 2008) and is expected to be small when applied to such a short portion of the life cycle (i.e., 40 days).

The time step in our bivalve matrix models was annual, meaning that the vital rates for early life stages that are days to weeks in length are factors within the longer process of annual reproduction. Thus, the fertility term (F ) is a multiplicative product of sub-annual vital processes, including brood size, larval survival, the probability of metamorphosis, and survival of post-metamorphic individuals to the next annual census. The effect of a proportional decrease in any one of these rates can be computed as a proportional decrease in F. We calculated the expected early life stage survival (S) from the laboratory models at 3 pCO2 scenarios (400, 800, and 1200 μatm) and then divided these by S338 and S355 for M. mercenaria and A. irradians, respectively, to standardize them to proportional impairments (relative to survey con ditions) that could be substituted as factors affecting fertility in the population models (i.e. at pCO2 = 800 μatm, F = Fbaseline. S800/S338). For M. mercenaria, this substitution was performed for F1, F2, and F3.

The final step was to incorporate variance in the model parameter estimates for projections of population risk. Following standard practice, this involved estimation of a stochastic population growth rate on the log scale (log λs) and its variance (see detailed descriptions in Caswell 2001 and Morris and Doak 2002). These were computed by first constructing distributions for each population model parameter. At each of T time steps, random variates were drawn from these distributions and substituted into the population model, which was then used to project the population vector forward one time step (Eqn 2). Following Caswell (2001, section 14.3.6), the stochastic growth rate was calculated from the results of these simulations as

| (8) |

where Nt is total population size at time t. The variance (σ2) was computed from the term shown after the summation operator. Estimates of log λs and σ2 were then used to calculate the cumulative probability of population abundance dropping by 50% over time (Dennis et al. 1991). This method exploits the tendency for geometric population growth to be well-approximated as a diffusion process with Gaussian errors when the real or simulated abundances are transformed to the log scale (Dennis et al. 1991, Caswell 2001, Lande et al. 2003).

The above-mentioned statistical distributions for the survival and fertility rates were modeled as beta and lognormal distributions, respectively (Morris & Doak 2002). The beta distributions for survival were constructed using the means and standard errors from the IDMs. Means for the lognormal fertility distributions were the F400, F800, and F1200 values for each species. We had no direct estimates of standard errors (SE) for the predictions of F at future pCO2 levels, so we assumed they would be the same proportion of the mean as computed for the baseline population model fitted from the field data (e.g. SE800 = SEbaseline x F800 / Fbaseline)

3. Results

3.1. Mercenaria mercenaria

The 1977–2011 surveys of the Islip M. mercenaria population in GSB indicated a steady decline in all 4 stages (Fig. 1). The difference in AICc between the stochastic-logistic and stochastic-exponential population model of total abundance was small (ΔAICc < 1), meaning the uncertainty introduced by adding a density-dependent parameter was too large relative to any gain in fit. Thus, we did not incorporate density dependence into the Mercenaria matrix model.

Maximum likelihood estimates using IDM produced the following density-independent transition matrix for the wild population of M. mercenaria (standard errors from the profile likelihoods are in parentheses; none of these profiles exhibited multiple local maxima):

| (9) |

The fertilities in the top row could be decomposed into maternity (m) and p0 if either of these values were known from other sources. For example, if GSB females produce 5.7 × 106 eggs (cherrystones; Bricelj & Malouf 1980), 0.1% of these survive to the larval stage (arbitrary assumption), and roughly 20% of these larvae survive to the spat stage (based on lab results analyzed here, see below), then m = 11 400 and p0 = F/m = 5 ×10−4.

The largest standard error in the matrix model is in the stage 3 transition and survival (P3). Large errors at the beginning of the time series (Fig. 1) are due to the difference of the initial population state vector (i.e. size abundances at t = 0) from the stable size class distribution in the fitted matrix A (i.e. the right eigenvector associated with the dominant eigenvalue). The fitted model appears to capture the general trends in abundance data (Fig. 1).

The computed population growth rate from the M. mercenaria model was λ = 0.92. The sensitivity of this value to small proportional perturbations of the nonzero parameters (i.e. elasticity) was:

| (10) |

The fertility values in A would have to be increased by 38% to produce a population growth rate of λ = 1, if no other rates were changed. Alternatively, a 15% increase in survival of the upper 3 stages would also give rise to λ = 1.

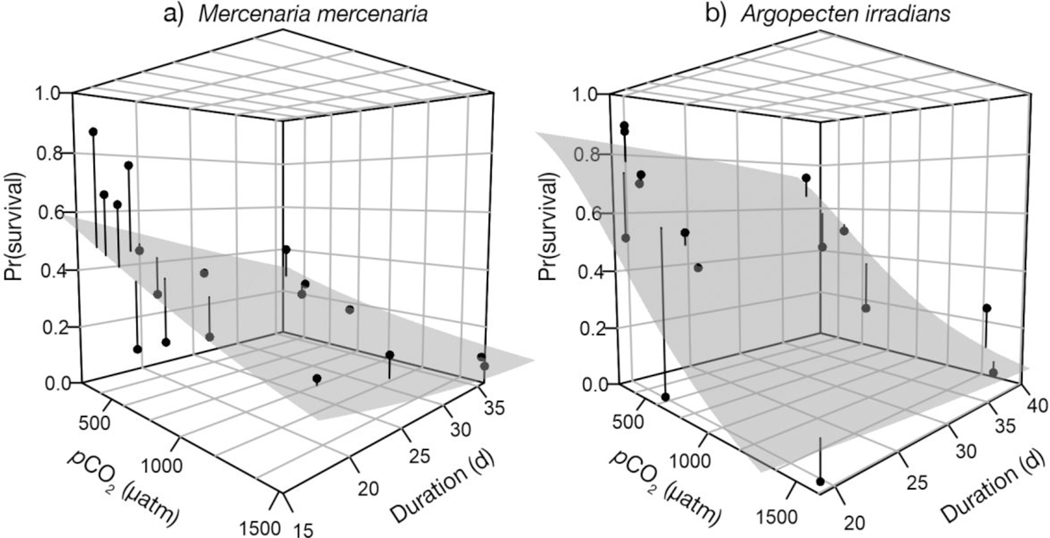

The general linear model (GLM) fit of early life stage survival in previous laboratory studies as a function of their pCO2 treatment levels and days of exposure produced the following logit-linear model of early life stage survival (S) for M. mercenaria (Fig. 2):

| (11) |

| (12) |

Figure 2.

Laboratory responses of early life stage survival of (a) Mercenaria mercenaria and (b) Argopecten irradians to manipulated pCO2. Points are compiled from previous studies (Talmage & Gobler 2009, 2010, 2011, Gobler & Talmage 2013, Gobler et al. 2014). Shaded surfaces are the fitted logistic regressions

The first equation is the linear function on the logittransformed variable θ; the second equation backtransforms θ to the natural scale. Analysis of deviance of the logistic regression indicated a significant pCO2 effect (Δ deviance = 688, df = 1, p = Pr [> x2] < 0.0001). Substitution of pCO2 (μatm) and day (up to Day 40) into these equations allows computation of early life-stage impairment based on the combined laboratory studies. In the 800 and 1200 μatm scenarios, these fitted functions produce 40 d survival rates that are 67 and 48% of the 400 μatm estimate, respectively (S400 = 0.21, S800 = 0.14, and S1200 = 0.10). The survival model can be reformulated to compute 40 d survival as a product of daily survival rates using:

| (13) |

with the S terms computed using Eqs. (11 & 12). By sub stituting day- specific pCO2 values, this would allow computation of 40 d survival under varying or decreasing daily pCO2 scenarios. However, 40 d survival estimates produced in this way give virtually the same result as computing the mean pCO2 during the season and then using it in the above equations. This is simply because in any function that assumes a constant geometric process (i.e. survival from day t to day t +1 is nearly constant for all t in Eqs. 11 & 15), as we were forced to do given available data, the mean of the function over varying levels of the predictor (pCO2) will be identical to applying the function directly to the mean of the predictor.

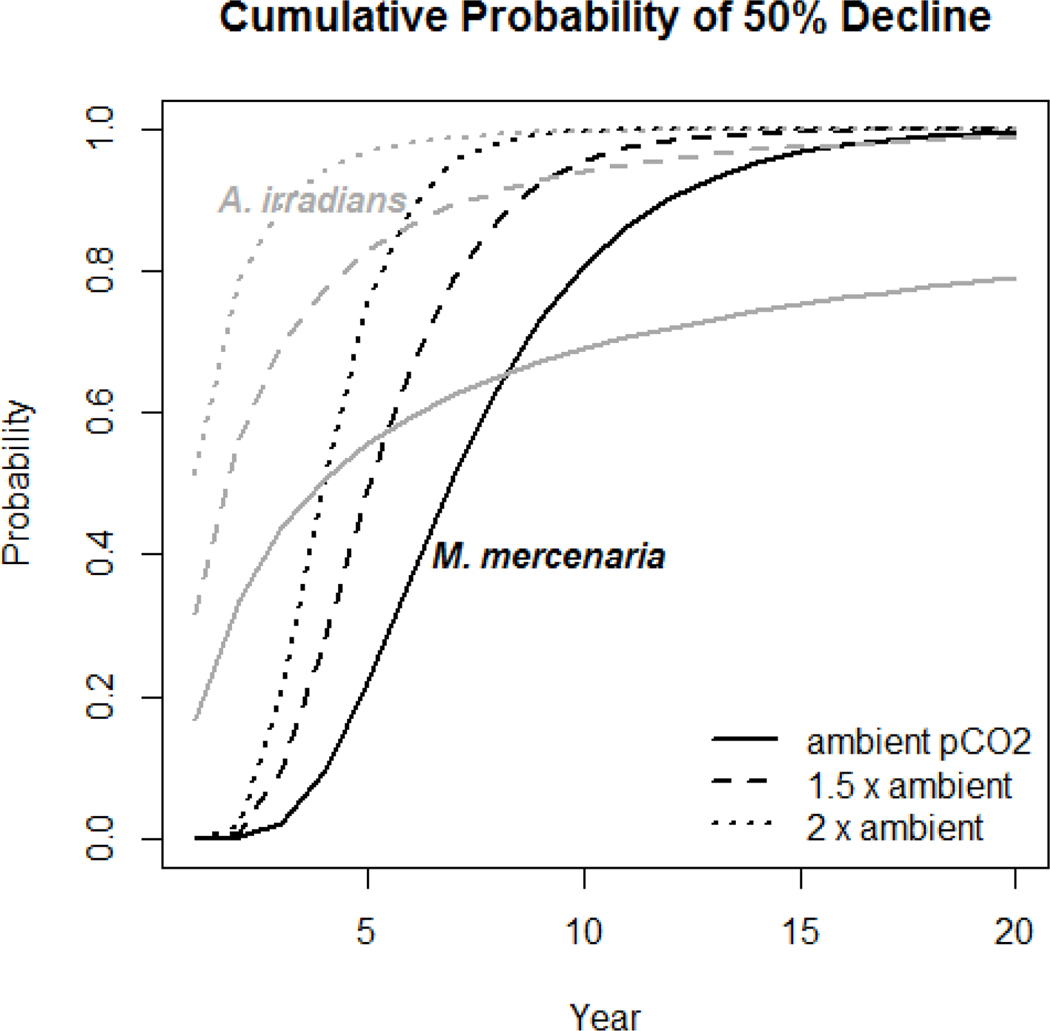

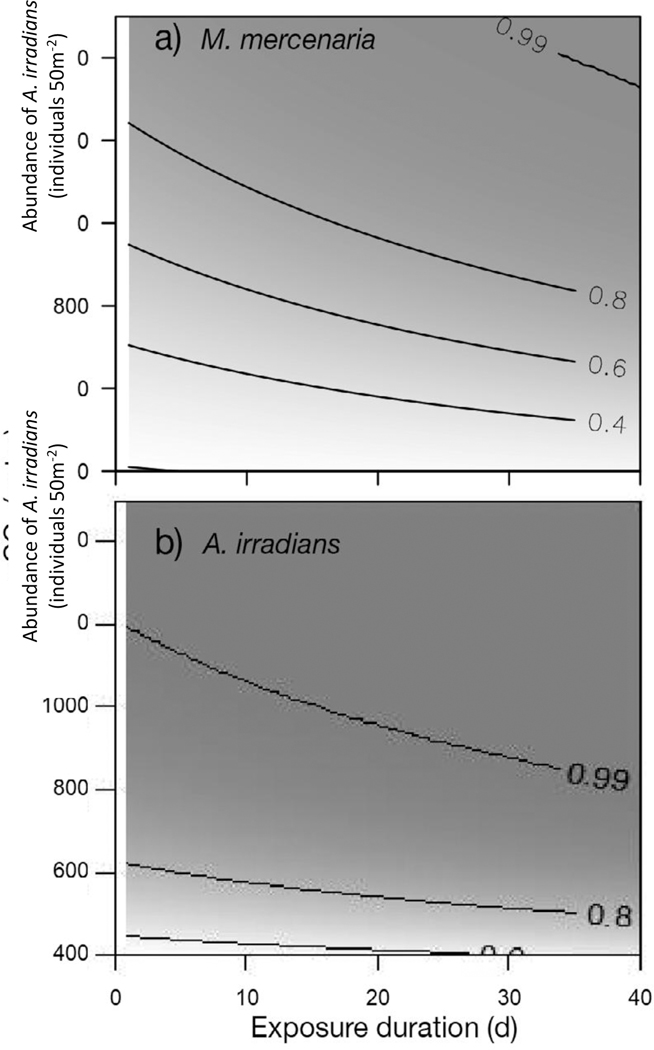

Substitutions of the impaired fertility values into the stochastic matrix models produced stochastic pop ulation growth rates for M. mercenaria of log λs,400 = −0.10 (σ2 = 0.01), log λs,800 = −0.17 (σ2 = 0.01), and log λs,1200 = −0.23 (σ2 = 0.02). As theoretically expected, the stochastic growth rate of the baseline model is lower than the growth rate from its deterministic equivalent (ln [λ] = −0.08) due to Jensen’s inequality (Ross 2010). The cumulative probability of the population declining by 50% within 5 yr in creases from 25% percent at 400 μatm to 79 and 97% in the 800 and 1200 μatm daytime pCO2 scenarios (Fig. 3). Estimated risk of 50% decline within 5 years exceeds 80% if daytime pCO2 exceeds 1200 μatm for several days during the early life stage (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Cumulative probabilities of 50% population decline computed from log stochastic population growth rates and variances for Mercenaria mercenaria and Argopecten irradians. The projections included impairment of early life stage survival; no other impairments were included. Exposure scenarios are based on daytime pCO2 and assume no additional effect of night time increases in pCO2

Figure 4.

Cumulative probabilities of 50% population decline within 5 yr at varying magnitudes and durations of exposure during the 40 d early life stage for (a) Mercenaria mercenaria and (b) Argopecten irradians. Probability is indicated by shade and contour lines. Exposure scenarios are based on daytime pCO2 and assume no additional effect of night time increases in pCO2

3.2. Argopecten. irradians

In the MARSS analysis of multi-site data, the best model based on AICc was the one with no site-specific effects on growth rate or error structures (Table 2). This indicated that it was most appropriate to fit the IDM for A. irradians using the sum of abundances across all sites. The estimated growth rate for the MARSS model was λ = 1.12.

As was the case for M. mercenaria, addition of a density dependence parameter was not justified. AICc was smaller (better) for the stochasticexponential model than for the stochastic-logistic model (ΔAICc = 2.2). Thus, we did not incorporate density dependence into the A. irradians matrix model.

Inverse demography calculations from the aggregated data resulted in the following annual time step transition matrix (with standard errors) for the wild A. irradians population:

| (14) |

Projections of total abundances showed good fit to the data at the start of the time series (Fig. 4). The A. irradians counts showed a large degree of variability halfway through the time series that the deterministic projection of the model failed to capture, but the MARSS analysis suggests some of this variability could be due to observation uncertainty. We did not perform elasticity analysis on the A. irradians model since it is essentially a scalar process governed by F = 1.12. Retention of the matrix formulation served to facilitate fitting via IDM and predicting the stable age distribution at census time (97% and 3% for age 0 and age 1, respectively).

Decomposition of F into its maternity (spat production) and spat survival factors (F = m × p0) gives m = F / p0 = 37.3 spat produced per age 0 A. irradians alive just before the spawning event. According to the model, 3% of these spat survive one year to be counted as age 1 individuals in the next annual survey.

The GLM model fit of early life stage survival in previous laboratory produced the following logit-linear model for A. irradians (Fig. 2):

| (15) |

which can be transfored to as in Eq. (12).

Analysis of deviance of the logistic regression indicated a significant pCO2 effect (Δ deviance = 2626, df = 1, p = Pr [> x2] < 0.0001). Substitution of impaired fertility rates into the stochastic version of the matrix produced stochastic population growth rates for A. irradians of log λs,400 = −0.02 (σ2 = 0.24), log λs,800 = −0.61 (σ2 = 0.37), and log λs,1200 = −1.48 (σ2 = 0.58). The cumulative probability of 50% de cline in abundance occurring within 5 yr increases from 56% percent at 400 μatm to 99% and >99% in the 800 and 1200 μatm daytime pCO2 scenarios (Fig. 3). Estimated risk of 50% decline within 5 yr approaches 100% if daytime pCO2 exceeds 1200 μatm for several days during the early life stage (Fig. 4b).

4. Discussion

We substituted laboratory pCO2 response relationships for early life stage bivalves into fieldparameterized matrix population models and then performed stochastic simulations of these substitution models to estimate population-level risk under scenarios of increased pCO2. Our results show that the levels of impairment observed in laboratory experiments have the potential to cause increased risk to marine bivalves in the northeastern USA. These findings are contingent upon several assumptions, the most important of which are that pCO2 affects only early life stage survival and that the impairments observed in the laboratory would also occur in situ. In addition, we assume that pCO2 effects combine additively with other forms of environmental stress (e.g. harvest, disease, harmful algal blooms), that the increases in mortality from pCO2 would not lead to compensatory changes in other vital rates due to changes in competition or predation, and that adaptive evolution (e.g. Thomsen et al. 2017) would not occur within the time frame we explored.

The Mercenaria mercenaria population in GSB is declining, as indicated in the growth rate estimated fromthe survey data (0.92).Thepotential causes of this decline during the surveys are complex, non- singular, and probably include overharvesting (Kraeuter et al. 2005, 2008), recurrent harmful algal blooms (Gobler & Sunda 2012), and other factors (e.g. low dissolved oxygen, acidification, predation, recruitment limitation due to low spawner density). For example, our results showed that a population growth rate of λ = 1 could be achieved in the model by increasing the baseline fertilities by 38%. This sheds light on the magnitude of the fertility deficit that would be required, if acting alone, to explain the observed population trend. However, the same effect was produced when survival of the little neck, cherrystone, and chowder stages was increased by only 15%, as might occur if harvest pressure were re duced. In other words, a small change in upper life stage survival produced the same growth rate estimate as a large change in fertility. This is consistent with theoretical life history predictions for long-lived species (Stearns 1992) and with the elasticity matrix (E), in which the sum of survival elasticities (0.77) is larger than the sum for fertilities (0.23).

Although a direct comparison of M. mercenaria and Argopecten irradians is not possible, their differing life history strategies and population growth rates (and the variance of those rate estimates) combine to produce differing estimates of risk. As ex pected for populations with stochastic growth rates that are both high and variable (Dennis et al. 1991), baseline risk accumulates more quickly and then levels off for A. irradians (Fig. 3). In addition, the elevated pCO2 scenarios caused a larger increase in risk for A. irradians than for M. mercenaria. This is a mathematical consequence of the stronger effects of pCO2 on early life stage survival observed in the laboratory and reflected in the fertility rates that were substituted into the model. The difference in risk is also affected by the greater adult longevity of M. mercenaria captured in the matrix model. An interpretation consistent with life history theory (e.g. Stearns 1992) is that the low elasticity for fertility relative to survival indicates lower selective pressure on offspring survival and lower population sensitivity to offspring mortality than would be the case for shorter-lived species.

The levels of pCO2 used in the laboratory experiments and in our population models have already been observed seasonally in field studies in estuaries near where the field data used in our population models were collected (Melzner et al. 2013, Hunt et al. 2014, Wallace et al. 2014), suggesting that M. mercenaria and A. irradians may already be exposed to levels of coastal acidification that could negatively affect these populations. Estuarine pCO2 levels can be highly dynamic, however, and values higher and lower than the critical levels we present may be experienced throughout the larval cycle (Wootton et al. 2008, Waldbusser & Salisbury 2014, Baumann et al. 2015). We showed that there is no reason to simulate time-varying pCO2 within a single season, given the simple survival model we were able to develop from available data. A more sophisticated survival model would capture carryover effects, delayed response (e.g. White et al. 2014), acclimation, or age-dependent effects of acidification on daily survival (e.g. accelerating or decelerating curves, sensu Deevey 1947, Grear & Elderd 2008, Miller & Waldbusser 2016) and would allow risk estimates to go beyond the non-varying pCO2 scenarios we used. Based on data from Wallace et al. (2014), pCO2 in bottom waters of the enriched western end of Long Island Sound exceed 1800 μatm at the onset of the spawning season and increase by 100–150 μatm by mid-summer. The timing of spawning in relation to this pattern would affect mean pCO2, and therefore, would affect risk estimates in our analysis. The ampli tude of this seasonal cycle is smaller in surface waters and in eastern Long Island Sound, but may be larger in shallow productive areas. In these areas, diurnal variation is likely a more significant omission from our analysis, since it has been shown to affect bivalve growth characteristics (Clark & Gobler 2016, Miller & Waldbusser 2016). However, data necessary to formulate this effect in a quantitative risk analysis were not available. This necessitated our assumption that diurnally varying pCO2 around a particular mean daytime level is suitably represented by constant exposure to that same level in the laboratory experiments.

Beyond acidification, the bivalves found in estuaries such as Great South Bay and the Peconic Estuary are subject to multiple stressors including harmful algal blooms and overfishing that need to be considered in population models when assessing impacts on population size and restoration potential (Grall & Chauvaud 2002). Overharvesting of M. mercenaria has already resulted in recent declines in this population and has inhibited its capacity to recover under multiple stressors (Kraeuter et al. 2008, Casey et al. 2014). However, other modeling work on population level processes governing M. mercenaria abundances indicate that overfishing cannot entirely explain the decrease in population numbers in GSB (Kraeuter et al. 2008). Should M. mercenaria and A. irradians continue to experience increasing acidification, our results can be interpreted as an indication that reductions in fertility could limit recovery of both bivalve populations regardless of other stressors. Hofmann et al. (2006) also examined M. mercenaria population dynamics in GSB using a model that accounted for food availability and environmental conditions, amongst other parameters. Consistent with our results, their study determined that cohort biomass and recruitment declined over time and indicated that the inclusion of impairments beyond harvesting would exacerbate M. mercenaria population declines (Hofmann et al. 2006).

Synergistic effects of multiple stressors may be the most common drivers of population decline (Portner et al. 2005, Rosa & Seibel 2008, Kirby et al. 2009, Hidalgo et al. 2011). Recent meta-analyses suggest that nonadditive effects are more common than additive effects in the ecological literature (Crain et al. 2008, Darling & Cote 2008, Allgeier et al. 2011). Indeed, Keppel et al. (2016) observed synergisms be tween hypoxia and low pH in the eastern oyster Crassostrea virginica, but these were often positive. For the species studied here, pCO2 and low dissolved oxygen can have synergistic negative effects (Gobler et al. 2014, Clark & Gobler 2016). Although we were unable to incorporate synergisms with pCO2 into our analysis, the impacts of coastal acidification may be more detrimental than our results indicate. Alternatively, for the impairment expected from ocean acidification to occur in these bivalves, there may be a pCO2 threshold above which conditions must remain throughout the larval stage (Clark & Gobler 2016). Given that pCO2 levels can fluctuate dramatically on a diurnal basis and on other time scales in coastal systems (Wootton et al. 2008, Waldbusser & Salisbury 2014, Baumann et al. 2015, Baumann & Smith 2018, Pacella et al. 2018), the impairment wrought by these cycles on wild populations is not totally clear. However, as already noted, recent laboratory studies of larval bivalves (Clark & Gobler 2016) and mechanistic computer simulations with post set juvenile bi valves suggest that severe diurnal cycling of acidification (Miller & Waldbusser 2016) can yield more drastic declines in survival than steady exposure to similarly low levels of acidification. Demographic modeling with explicit treatment of stochasticity and estimation uncertainty provides a powerful tool for understanding how these stage-specific responses affect bivalve populations.

Although there are alternatives to the methods we used, one strength of inverse demography is its application to data from intact populations when other methods for tracking stage-specific vital rates are not feasible (e.g. mark–resight methods). In addition, when data from multiple independent populations are available, the maximum likelihood framework that underlies this method has been shown in crustacean experiments to be suitable for discriminating among multiple possible life history mechanisms (e.g. trade-offs) governing population responses to pCO2 (Grear 2016). Such an approach would help to address the assumed lack of compensatory mechanisms in our analysis if manipulative multi-generational studies of replicate intact bivalve populations could be performed.

It is critical that ocean and coastal acidification research evaluates the extent to which shifts in vital rates alter the growth rates and stability of populations and ecosystems (Gaylord et al. 2015). Here, we have attempted to scale laboratory results to populations, but our analysis required sufficient population data for estimating a population model into which early life stage impairments could be substituted. As previously discussed, inverse demographic methods such as the one we used can introduce problems with identifiability, but these diminish when natural history is known well enough to constrain solutions in the fitting process. Important alternatives include the more physiological approach used by Guy et al. (2014), the synthetic matrix approach used by Cooley et al. (2015), and the integral projection model (IPM) suggested by Ellner & Rees (2006) and discussed by Gaylord et al. (2015). In the case of IPMs, the requirement for individual-based observations (or simulations thereof) was not suitable for our study. In any case, these methods and ours provide insight into effects of acidification or other stressors on populations, which are the endpoint upon which management is often focused (Conrad 1982).

Evolutionary theory predicts that environmental variation can select for a variety of life history strategies, some of which can diminish the effects of sensitive biological traits on population fitness and magnify the role of other less sensitive traits (Pfister 1998). In long-lived species, for example, upper life stage impairments small enough to be virtually un detectable by conventional methods may be as im portant to population dynamics as large and easily detected impairments of early life stages (e.g. Crouse et al. 1987, Mitro et al. 2008). This is consistent with the behavior of the fitted baseline M. mercenaria model, where computed growth rate (λ) in this long-lived species was more strongly affected by impairments of adult survival than by proportionately identical impairments of larval survival. Although we can only speculate about the factors leading to this particular life history, it is clear that biological sensitivity alone may not be a sufficient basis for prioritizing early life stages in studies concerned with effects of acidification at the population, community, or ecosystem level. This by no means implies that larval impairment is unimportant, but it does suggest that seemingly subtle biological effects on upper life stages can be amplified by demographic processes and therefore should be considered. Thus, future studies of biological responses to pCO2 should include mid and upper life stages as well as effects on egg size or quality. Also, further study is needed to assess (1) the relative and concurrent effects of other stressors such as high temperatures, harmful algal blooms, and hypoxia and (2) the temporal dynamics of pCO2 in estuaries during periods when shellfish larvae, the stage most biologically sensitive to acidification (Talmage & Gobler 2011, Gazeau et al. 2013, Waldbusser et al. 2013), are present in the water column. In addition, future studies should attempt to incorporate more field data to improve upon and/or verify growth and fertility parameter estimates, and should focus on populations where the estimation of the full life history specific to the local study population is feasible.

5. Conclusion

The assumption that organismal responses are predictive of effects on populations and ecosystems has been identified as common practice in assessments of ecological and social risk from ocean and coastal acidification (Mathis et al. 2015). Our methods are a step forward from this approach, although they require a variety of assumptions and caveats familiar to practitioners in quantitative population ecology and conservation. By substituting laboratory-derived responses of early life stage survival into field parameterized models of intact populations, we illustrated that a doubling of daytime pCO2 levels from 400 to 800 μatm could increase the risk of 50% population decline within 5 yr from 25 to >79% for Mercenaria mercenaria and from 56 to 99% for Argopecten irradians. Such a doubling of pCO2 levels through the seasonal period of early life stage development is easily conceivable in the near future through either eutrophication alone or its negative effects on buffering against atmospheric CO2.

Figure 5.

(a) Observed (points) and projected (lines) Argopecten irradians densities for Peconic Estuary, NY, by stage (summed across sites). Projections are matrix projections from the initial population state using the ambient transition matrix. (b) Observed log densities by site and the combined log density estimated from the multivariate autoregressive state-space model (MARSS). Shading indicates 95% confidence interval on the estimated states

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program through award NA12NOS 4780148 from the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, New York Sea Grant Award R-CMB-41, and the Chicago Community Trust. J.S.G.’s contribution was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the EPA. The manuscript was submitted with EPA tracking number ORD-017554. Robert Cerrato, Stephen Shivers, and Brenda Rashleigh provided helpful comments on an earlier version.

Literature Cited

- Allgeier JE, Rosemond AD, Layman CA (2011) The frequency and magnitude of non additive responses to multiple nutrient enrichment. J Appl Ecol 48: 96–101 [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H, Smith EM (2018) Quantifying metabolically driven pH and oxygen fluctuations in US nearshore habitats at diel to interannual time scales. Estuaries Coasts 41: 1102–1117 [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H, Wallace RB, Tagliaferri T, Gobler CJ (2015) Large natural pH, CO2 and O2 fluctuations in a temperate tidal salt marsh on diel, seasonal, and interannual time scales. Estuaries Coasts 38: 220–231 [Google Scholar]

- Beissinger SR, Westphal MI (1998) On the use of demographic models of population viability in endangered species management. J Wildl Manag 62: 821–841 [Google Scholar]

- Belding DL (1910) The scallop fishery of Massachusetts. Mar Fish Ser No. 3, Vol 1910. Division of Fisheries and Game, Department of Conservation, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- Blight SP, Bentley TL, Lefevre D, Robinson C, Rodrigues R, Rowlands J, Williams PJleB (1995) Phasing of autotrophic and heterotrophic plankton metabolism in a temperate coastal ecosystem. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 128: 61–75 [Google Scholar]

- Borges AV, Gypens N (2010) Carbonate chemistry in the coastal zone responds more strongly to eutrophication than to ocean acidification. Limnol Oceanogr 55: 346–353 [Google Scholar]

- Bricelj VM, Malouf RE (1980) Aspects of reproduction of hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria) in Great South Bay, New York. Proc Natl Shellfish Assoc 70: 216–229 [Google Scholar]

- Bricelj VM, Epp J, Malouf RE (1987) Comparative physiology of young and old cohorts of bay scallop Argopecten irradians irradians (Lamarck): mortality, growth, and oxygen consumption. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 112: 73–91 [Google Scholar]

- Bricker S, Longstaff B, Dennison W, Jones A, Boicourt K, Wicks C, Woerner J (2007) Effects of nutrient enrichment in the nation’s estuaries: a decade of change. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Silver Spring, MD [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2002) Model selection and multimodel inference. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- Cai WJ, Hu X, Huang WJ, Murrell MC and others (2011) Acidification of subsurface coastal waters enhanced by eutrophication. Nat Geosci 4: 766–770 [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Caldeira K (2008) Atmospheric CO2 stabilization and ocean acidification. Geophys Res Lett 35: L19609 [Google Scholar]

- Casey MM, Dietl GP, Post DM, Briggs DE (2014) The impact of eutrophication and commercial fishing on molluscan communities in Long Island Sound, USA. Biol Conserv 170: 137–144 [Google Scholar]

- Caswell H (2001) Matrix population models: construction, analysis and interpretation. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- Clark HR, Gobler CJ (2016) Diurnal fluctuations in CO2 and dissolved oxygen concentrations do not provide a refuge from hypoxia and acidification for early-life-stage bivalves. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 558: 1–14 [Google Scholar]

- Conrad JM (1982) Management of a multiple cohort fishery: the hard clam in Great South Bay. Am J Agric Econ 64: 463–474 [Google Scholar]

- Cooley SR, Rheuban JE, Hart DR, Luu V, Glover DM, Hare JA, Doney SC (2015) An integrated assessment model for helping the United States sea scallop (Placopecten magellanicus) fishery plan ahead for ocean acidification and warming. PLOS ONE 10: e0124145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain CM, Kroeker K, Halpern BS (2008) Interactive and cumulative effects of multiple stressors in marine systems. Ecol Lett 11: 1304–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouse D, Crowder L, Caswell H (1987) A stage-based population model for loggerhead sea turtles and implications for conservation. Ecology 68: 1412–1423 [Google Scholar]

- Darling ES, Cote IM (2008) Quantifying the evidence for ecological synergies. Ecol Lett 11: 1278–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deevey ES Jr (1947) Life tables for natural populations of animals. Q Rev Biol 22: 283–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis B, Taper ML (1994) Density dependence in time series observations of natural populations: estimation and testing. Ecol Monogr 64: 205–224 [Google Scholar]

- Dennis B, Munholland P, Scott JM (1991) Estimation of growth and extinction parameters for endangered species. Ecol Monogr 61: 115–143 [Google Scholar]

- Dennis B, Desharnais RA, Cushing JM, Constantino RF (1995) Nonlinear demographic dynamics: mathematical models, statistical methods, and biological experiments. Ecol Monogr 65: 261–281 [Google Scholar]

- Doney SC, Fabry VJ, Feely RA, Kleypas JA (2009) Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Annu Rev Mar Sci 1: 169–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellner SP, Rees M (2006) Integral projection models for species with complex demography. Am Nat 167: 410–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feely RA, Alin SR, Newton J, Sabine CL and others (2010) The combined effects of ocean acidification, mixing, and respiration on pH and carbonate saturation in an urbanized estuary. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 88: 442–449 [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord B, Kroeker KJ, Sunday JM, Anderson KM and others (2015) Ocean acidification through the lens of ecological theory. Ecology 96: 3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazeau F, Parker LM, Comeau S, Gattuso JP and others (2013) Impacts of ocean acidification on marine shelled molluscs. Mar Biol 160: 2207–2245 [Google Scholar]

- Gobler CJ, Sunda WG (2012) Ecosystem disruptive algal blooms of the brown tide species, Aureococcus anophagefferens and Aureoumbra lagunensis. Harmful Algae 14: 36–45 [Google Scholar]

- Gobler CJ, Talmage SC (2013) Short- and long-term consequences of larval stage exposure to constantly and ephemerally elevated carbon dioxide for marine bivalve populations. Biogeosciences 10: 2241–2253 [Google Scholar]

- Gobler CJ, Talmage SC (2014) Physiological response and resilience of early life-stage Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) to past, present and future ocean acidification. Conserv Physiol 2:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobler CJ, DePasquale EL, Griffith AW, Baumann H (2014) Hypoxia and acidification have additive and synergistic negative effects on the growth, survival, and metamorphosis of early life stage bivalves. PLOS ONE 9: e83648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grall J, Chauvaud L (2002) Marine eutrophication and benthos: the need for new approaches and concepts. Glob Change Biol 8: 813–830 [Google Scholar]

- Grear JS (2016) Translating crustacean biological responses from CO2 bubbling experiments into population-level predictions. Popul Ecol 58: 515–524 [Google Scholar]

- Grear JS, Elderd BD (2008) Bias in population growth rate estimation: sparse data, partial life cycle analysis and Jensen’s inequality. Oikos 117: 1587–1593 [Google Scholar]

- Grear JS, Meyer MW, Cooley JH Jr, Kuhn A and others (2009) Population growth and demography of common loons in the northern United States. J Wildl Manag 73: 1108–1115 [Google Scholar]

- Grear JS, Borsay Horowitz D, Gutjahr-Gobell R (2011) Mysid population responses to resource limitation differ from those predicted by cohort studies. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 432: 115–123 [Google Scholar]

- Green MA, Waldbusser GG, Reilly SL, Emerson K (2009) Death by dissolution: sediment saturation state as a mortality factor for juvenile bivalves. Limnol Oceanogr 54: 1037–1047 [Google Scholar]

- Guy CI, Cummings VJ, Lohrer AM, Gamito S, Thrush SF (2014) Population trajectories for the Antarctic bivalve Laternula elliptica: identifying demographic bottlenecks in differing environmental futures. Polar Biol 37: 541–553 [Google Scholar]

- Hall VA, Liu C, Cadrin SX (2015) The impact of the second seasonal spawn on the Nantucket population of the northern bay scallop. Mar Coast Fish 7: 419–433 [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M, Rouyer T, Molinero JC, Massuti E, Moranta J, Guijarro B, Stenseth NC (2011) Synergistic effects of fishing-induced demographic changes and climate variation on fish population dynamics. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 426: 1–12 [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann EE, Klinck JM, Kraeuter JN, Powell EN, Grizzle RE, Buckner SC, Bricelj VM (2006) A population dynamics model of the hard clam, Mercenaria mercenaria: development of the age- and length-frequency structure of the population. J Shellfish Res 25: 417–444 [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EE, Ward EJ, Wills K (2012) Marss: Multivariate autoregressive state-space models for analyzing timeseries data. R J 4: 11–19 [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E, Ward E, Wills K (2013) Marss: Multivariate autoregressive state-space modeling. R package version 3.9 https://cran.r-project.org/package=MARSS [Google Scholar]

- Hunt CW, Salisbury JE, Vandemark D (2014) CO2 input dynamics and air–sea exchange in a large New England estuary. Estuaries Coasts 37: 1078–1091 [Google Scholar]

- Keppel AG, Breitburg DL, Burrell RB (2016) Effects of covarying diel-cycling hypoxia and pH on growth in the juvenile eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica. PLOS ONE 11: e0161088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney EL, Valiela I (2011) Nitrogen loading to Great South Bay: land use, sources, retention, and transport from land to bay. J Coast Res 27: 672–686 [Google Scholar]

- Kirby RR, Beaugrand G, Lindley JA (2009) Synergistic effects of climate and fishing in a marine ecosystem. Ecosystems 12: 548–561 [Google Scholar]

- Kraeuter JN, Castagna M (eds) (2001) Biology of the hard clam, Vol 31. Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- Kraeuter JN, Buckner S, Powell EN (2005) A note on a spawner-recruit relationship for a heavily exploited bivalve: the case of northern quahogs (hard clams), Mercenaria mercenaria in Great South Bay New York. J Shellfish Res 24: 1043–1052 [Google Scholar]

- Kraeuter JN, Klinck JM, Powell EN, Hofmann EE, Buckner SC, Grizzle RE, Bricelj VM (2008) Effects of the fishery on the northern quahog (hard clam, Mercenaria mercenariaL.) population in Great South Bay, New York: a modeling study. J Shellfish Res 27: 653–666 [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker KJ, Kordas RL, Crim RN, Singh GG (2010) Metaanalysis reveals negative yet variable effects of ocean acidification on marine organisms. Ecol Lett 13: 1419–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande R, Engen S, Saether BE (2003) Stochastic population dynamics in ecology and conservation, Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Mathis JT, Cooley SR, Lucey N, Colt S and others (2015) Ocean acidification risk assessment for Alaska’s fishery sector. Prog Oceanogr 136: 71–91 [Google Scholar]

- Melzner F, Thomsen J, Koeve W, Oschlies A, Gutowska MA, Bange HW, Kortzinger A (2013) Future ocean acidification will be amplified by hypoxia in coastal habitats. Mar Biol 160: 1875–1888 [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Waldbusser GG (2016) A post-larval stage-based model of hard clam Mercenaria mercenaria development in response to multiple stressors: temperature and acidification severity. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 558: 35–49 [Google Scholar]

- Mitro MG, Evers DC, Meyer MW, Piper WH (2008) Common loon survival rates and mercury in New England and Wisconsin. J Wildl Manag 72: 665–673 [Google Scholar]

- Morris WF, Doak DF (2002) Quantitative conservation biology: theory and practice of population viability analysis. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- Mucci A, Starr M, Gilbert D, Sundby B (2011) Acidification of lower St. Lawrence estuary bottom waters. Atmos-Ocean 49: 206–218 [Google Scholar]

- Newell RIE (2004) Ecosystem influences of natural and cultivated populations of suspension-feeding bivalve molluscs: a review. J Shellfish Res 23: 51–61 [Google Scholar]

- NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service) (2017) Commercial fisheries statistics. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Ad min istration. https://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/commercialfisheries/commercial-landings/index (accessed 17 July 2018)

- Officer CB, Smayda TJ, Mann R (1982) Benthic filter feeding: a natural eutrophication control. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 9: 203–210 [Google Scholar]

- Orr JC, Fabry VJ, Aumont O, Bopp L, Doney SC, Feely RA, Key RM (2005) Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 437: 681–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacella SR, Brown CA, Waldbusser GG, Labiosa RG, Hales B (2018) Seagrass habitat metabolism increases short-term extremes and long-term offset of CO2 under future ocean acidification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: 3870–3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawitan Y (2001) In all likelihood: statistical modelling and inference using likelihood. Oxford University Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- Pfister CA (1998) Patterns of variance in stage-structured populations: evolutionary predictions and ecological im plications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 213–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy LR, D’Elia CF, Schaffner LC (2006) Limits to topdown control of phytoplankton by oysters in Chesapeake bay. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 325: 301–309 [Google Scholar]

- Portner HO, Langenbuch M, Michaelidis B (2005) Synergistic effects of temperature extremes, hypoxia, and increases in CO2 on marine animals: from earth history to global change. J Geophys Res 110: C09S10 [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing, version 3.3.0. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna [Google Scholar]

- Rosa R, Seibel BA (2008) Synergistic effects of climaterelated variables suggest future physiological impairment in a top oceanic predator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20776–20780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S (2010) A first course in probability. Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River, NJ [Google Scholar]

- Ruesink JL, Sarich A, Trimble AC, Browman H (2018) Similar oyster reproduction across estuarine regions differing in carbonate chemistry. ICES J Mar Sci 75: 340–350 [Google Scholar]

- SCDHS (Suffolk County Department of Health Services) (2017) Annual report of coastal water quality, 2015–2017. Suffolk County Department of Health Services, Yaphank, NY [Google Scholar]

- Schubel JR, Bell TM, Carter HH (eds) (1991) The Great South Bay. State University of New York Press, Albany, NY [Google Scholar]

- Shumway SE, Parsons GJ (eds) (2011) Scallops: biology, ecology and aquaculture, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- Stearns SC (1992) The evolution of life histories, Vol. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Sutherland SC, Wanninkhof R, Sweeney C and others (2009) Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea–air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep Sea Res II 56: 554–577 [Google Scholar]

- Talmage SC, Gobler CJ (2009) The effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentrations on the metamorphosis, size, and survival of larval hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria), bay scallops (Argopecten irradians), and eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica). Limnol Oceanogr 54: 2072–2080 [Google Scholar]

- Talmage SC, Gobler CJ (2010) Effects of past, present, and future ocean carbon dioxide concentrations on the growth and survival of larval shellfish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17246–17251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmage SC, Gobler CJ (2011) Effects of elevated temperature and carbon dioxide on the growth and survival of larvae and juveniles of three species of northwest Atlantic bivalves. PLOS ONE 6: e26941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmage SC, Gobler CJ (2012) Effects of CO2 and the harmful alga Aureococcus anophagefferens on growth and survival of oyster and scallop larvae. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 464: 121–134 [Google Scholar]

- Tettelbach ST, Smith CF, Smolowitz R, Tetrault K, Dumais S (1999) Evidence for fall spawning of northern bay scallops Argopecten irradians irradians (Lamarck 1819) in New York. J Shellfish Res 18: 47–58 [Google Scholar]

- Tettelbach ST, Peterson BJ, Carroll JM, Hughes SWT and others (2013) Priming the larval pump: resurgence of bay scallop recruitment following initiation of intensive restoration efforts. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 478: 153–172 [Google Scholar]

- Tettelbach ST Peterson BJ, Carroll JM, Furman BT and others (2015) Aspiring to an altered stable state: rebuilding of bay scallop populations and fisheries following intensive restoration. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 529: 121–136 [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen J, Stapp LS, Haynert K, Schade H and others (2017) Naturally acidified habitat selects for ocean acidification–tolerant mussels. Sci Adv 3: e1602411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vuuren DP, Edmonds J, Kainuma M, Riahi K and others (2011) The representative concentration pathways: an overview. Clim Change 109: 5–31 [Google Scholar]

- Waldbusser GG, Salisbury JE (2014) Ocean acidification in the coastal zone from an organism’s perspective: multiple system parameters, frequency domains, and habitats. Annu Rev Mar Sci 6: 221–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldbusser GG, Brunner EL, Haley BA, Hales B, Langdon CJ, Prahl FG (2013) A developmental and energetic basis linking larval oyster shell formation to acidification sensitivity. Geophys Res Lett 40: 2171–2176 [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RB, Baumann H, Grear JS, Aller RC, Gobler CJ (2014) Coastal ocean acidification: the other eutrophication problem. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 148: 1–13 [Google Scholar]

- White MM, Mullineaux LS, McCorkle DC, Cohen AL (2014) Elevated pCO2 exposure during fertilization of the bay scallop Argopecten irradians reduces larval survival but not subsequent shell size. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 498: 173–186 [Google Scholar]

- Wood SN (1994) Obtaining birth and mortality patterns from structured population trajectories. Ecol Monogr 64: 23–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton JT, Pfister CA, Forester JD (2008) Dynamic patterns and ecological impacts of declining ocean pH in a highresolution multi-year dataset. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 18848–18853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]