Abstract

Background

Theragnostic management, treatment according to precise pathological molecular targets, requests to unravel patients’ genotypes. We used targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) or digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) to screen for somatic PIK3CA mutations on DNA extracted from resected lesional tissue or lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) isolated from lesions. Our cohort (n = 143) was composed of unrelated patients suffering from a common lymphatic malformation (LM), a combined lymphatic malformation [lymphatico-venous malformation (LVM), capillaro-lymphatic malformation (CLM), capillaro-lymphatico-venous malformation (CLVM)], or a syndrome [CLVM with hypertrophy (Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome, KTS), congenital lipomatous overgrowth-vascular malformations-epidermal nevi -syndrome (CLOVES), unclassified PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome (PROS) or unclassified vascular (lymphatic) anomaly syndrome (UVA)].

Results

We identified a somatic PIK3CA mutation in resected lesions of 108 out of 143 patients (75.5%). The frequency of the variant allele ranged from 0.54 to 25.33% in tissues, and up to 47% in isolated endothelial cells. We detected a statistically significant difference in the distribution of mutations between patients with common and combined LM compared to the syndromes, but not with KTS. Moreover, the variant allele frequency was higher in the syndromes.

Conclusions

Most patients with an common or combined lymphatic malformation with or without overgrowth harbour a somatic PIK3CA mutation. However, in about a quarter of patients, no such mutation was detected, suggesting the existence of (an)other cause(s). We detected a hotspot mutation more frequently in common and combined LMs compared to syndromic cases (CLOVES and PROS). Diagnostic genotyping should thus not be limited to PIK3CA hotspot mutations. Moreover, the higher mutant allele frequency in syndromes suggests a wider distribution in patients’ tissues, facilitating detection. Clinical trials have demonstrated efficacy of Sirolimus and Alpelisib in treating patients with an LM or PROS. Genotyping might lead to an increase in efficacy, as treatments could be more targeted, and responses could vary depending on presence and type of PIK3CA-mutation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13023-021-01898-y.

Keywords: Lymphatic malformation, Isolated, Gene, Mutation, Somatic, PI3K, Epidemiology, Theragnostic, Allele, Frequency

Background

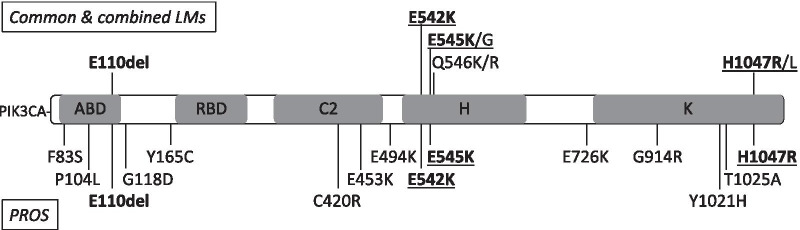

Vascular malformations are usually congenital and localized. They slowly develop with the growth of the child. Treatments are mostly limited to laser, sclerotherapy, embolization and surgical resection. A malformation can affect any part of the lympho-vascular system (Fig. 1). A pure malformation affects only one compartment, e.g. a common lymphatic malformation (LM), whereas combined vascular malformations associate at least two components in the same lesion, e.g. a capillaro-lymphatic malformation [1]. Patients with isolated lesions have no other associated signs, whereas syndromic-forms affect at least one other organ.

Fig. 1.

Clinical characteristics of representative patients. a Mixed LM of left thorax (mutation p.Glu545Lys at 5% by NGS). b CLVM of left thorax with visible lymphatic vesicles (mutation p.His1047Arg at 5% by NGS and 5% by ddPCR). c Unclassified PROS (mutation p.Cys420Arg at 2% by NGS). d Macrodactyly and syndactyly 2–3 with small sandal gap and CM of right foot of a CLOVES syndrome patient

In the princeps study in 2009, it was demonstrated that somatic genetic mutations are associated with sporadically occurring vascular anomalies: isolated venous malformations (VM) were discovered to have somatic TIE2/TEK mutations [2]. Since then, the etiopathogenesis of various isolated and combined vascular malformations has been unravelled [3, 4]. One of the genes identified to be mutated in vascular malformations encodes the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA, also known as p110α). Mutations were first identified in rare syndromic patients with Congenital Lipomatous Overgrowth, Vascular malformations, Epidermal nevi, and Skeletal/spinal abnormalities and/or scoliosis (CLOVES) [5]. Subsequently, PIK3CA mutations were implicated in common LM (43 out of 47 lesions) [6–8], and isolated VM without a TIE2/TEK mutation (27 out of 50 lesions) [9]. Somatic/mosaic PIK3CA mutations have also been implicated in variable syndromic phenotypes that can associate vascular anomalies with hypertrophy, leading to name this spectrum “PIK3CA-Related Overgrowth Syndrome” or PROS [10]. It includes CLOVES, Fibroadipose Hyperplasia (FH), Fibroadipose infiltrating lipomatosis, Hemihyperplasia multiple lipomatosis (HHML), Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), Megalencephaly-Capillary Malformation-Polymicrogyria syndrome (MCAP), Macrodactyly, Hemimegalencephaly, and Muscle hemihyperplasia [10].

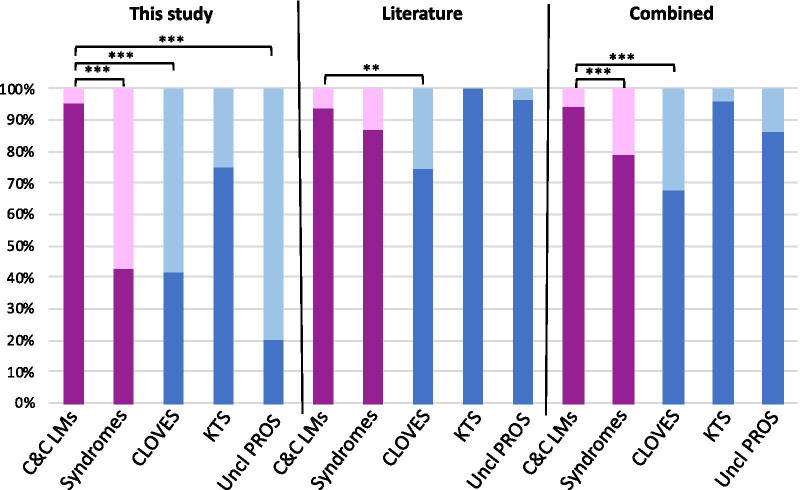

PIK3CA is considered as an oncogene [11]. The encoded p110α subunit contains the adapter-binding domain (ABD), the Ras-binding domain (RBD), the C2-PI3K-type domain (C2), the helical domain (H) and the kinase domain (K) (Fig. 2) [12]. Mutations that spread over the five functional domains have been implicated in many cancers, with positions c.1624G (p.E542), c.1633G (p.E545) and c.3140A (p.H1047) as hotspots. Similar mutations have been found in small series of lymphatic and vascular malformations.

Fig. 2.

PIK3CA protein (Human, 1068 aa) and mutations. Top, mutations found in common and combined lymphatic malformations (LM, LVM, CLVM). Bottom, mutations found in patients with PROS (KTS, CLOVES, unclassified PROS). See distribution in Table 1. Shared mutations in bold. Hotspot mutations underlined. ABD, p85α-binding domain; RBD, Ras-binding domain; C2, C2-PIK3C-type domain; H, helical domain; K, kinase domain

In this study, we analysed for the presence of a PIK3CA mutation in a large cohort of lymphatic malformations, including common LM, lymphatico-venous malformation (LVM), capillaro-lymphatic malformation (CLM), capillaro-lymphatico-venous malformation (CLVM), unilateral capillaro-lymphatico-venous malformation with hypertrophy (KTS), CLOVES syndrome, unclassified PROS and unclassified vascular anomaly syndrome (UVA). This study contains the largest cohort studied so far for isolated lymphatic malformations. We analysed the prevalence, distribution and allele frequency of PIK3CA mutations in these phenotypes and evaluated for any genotype–phenotype correlation. This study provides firm epidemiological data, essential for the design of diagnostic testing, prospective clinical trials and drug development.

Results

To assess the contribution of PIK3CA mutations in common, combined and syndromic LM (Table 1), we screened DNA extracted from frozen tissues or isolated cells from 143 patients: 105 common LM, 3 LVM, 1 CLM, 7 CLVM, 4 KTS, 14 CLOVES, 7 PROS and 2 UVA. Within the mutated lesions, the variant allele frequency (VAF) varied strongly: from 0.54 to 25.33% for NGS-based analyses, and from 0.28% (14 SPD) to 22.7% for ddPCR-based analyses. The median VAF was 4.04% (STDEV = 4.57%), with 60% of patients having ≤ 5% VAF. In addition, we had 8 common LMs inconclusive for the presence of hotspot mutations (5 to 9 mutant reads, but only 0.24–0.52% VAF, not confirmed by ddPCR due to lack of DNA).

Table 1.

Patients cohort and PIK3CA mutations per pathology

| Pathology | LM | LVM | CLM | CLVM | KTS | CLOVES | PROS | UVA | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | 105 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 14 | 7 | 2 | 143 |

| Mutation | 78 | 3 | – | 6 | 4 | 12 | 5 | – | 108 |

| No mutation | 19 | – | 1 | 1 | – | 2 | 2 | 2 | 27 |

| Inconclusive | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8 |

| % with a mutation | 74.3% | 100% | 0% | 85.7% | 100% | 85.7% | 71.4% | 0% | 75.5% |

| VAF median | 3.71 | 4.59 | – | 7.34 | 8.12 | 12.90 | 11.09 | – | 4.05 |

| Standard deviation | 4.49 | 2.52 | – | 6.53 | 6.27 | 7.30 | 5.65 | – | 4.85 |

| VAF range | 0.54–11.34 | 3.43–8.25 | – | 4.71–22.19 | 1.15–13.17 | 2.00–25.33 | 1.00–13.00 | – | 0.54–25.33 |

| Hotspot mutations | 74 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 92 |

| Non-hotspot mutations | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 16 |

| PIK3CA Domain | Mutation | LM | LVM | CLM | CLVM | KTS | CLOVES | PROS | UVA | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABD | F83S | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| ABD | P104L | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| E110del | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| G118D | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Y165C | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| C2 | C420R | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| C2 | E453K | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| E494K | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Helical | E542K | 26 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 31 | ||||

| Helical | E545K | 27 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 34 | ||||

| Helical | E545G | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Helical | Q546K | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Helical | Q546R | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| E76K | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Kinase | G914R | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Kinase | Y1021H | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Kinase | T1025A | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Kinase | H1047R | 17 | 3 | 3 | 23 | |||||

| Kinase | H1047L | 3 | 3 |

Bold: hotspot mutations. Protein domains based on https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P42336: ABD, p85α-binding domain (amino acids 16–105); C2, C2-PIK3C-type domain (330–487); Helical, Helical domain (517–694); Kinase, Kinase domain (797–1068). See also Fig. 2

PIK3CA mutations were found in 78/105 common LM (74.3%), 3/3 LVM (100%), 6/7 CLVM (85.7%), 4/4 KTS (100%), 12/14 CLOVES (85.7%) and 5/7 PROS (71.4%) (Table 1). No PIK3CA mutation was detected in the unique CLM and the two UVA tested. Out of the 108 mutations detected, 92 (85.1%) were at hotspot positions: 31 p.E542K (c.1624G > A), 34 p.E545K (c.1633G > A), 1 p.E545G (c.1634A > G), 23 p.H1047R (c.3140A > G) and 3 p.H1047L (c.3140A > T). The rest was covered by 14 distinct non-hotspot mutations in 16 samples (Table 1). We also isolated primary cells from two resected tissues (one LM and one CLVM), to locate the population harbouring the mutation (Table 2). Strong enrichment of the somatic mutation was observed within the isolated endothelial cells (ECs) and especially lymphatic ECs.

Table 2.

PIK3CA variants allele frequencies in tissues and isolated cells

| Disease | Sample type | Mutation | VAF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLVM | Tissue | p.His1047Arg | 5 |

| CD31-positive cells (EC) | p.His1047Arg | 47 | |

| CD31-negative cells | p.His1047Arg | 0 | |

| LM | Tissue | p.Glu542Lys | 11 |

| Unselected cells | p.Glu542Lys | 4 | |

| CD34-positive cells (BEC) | p.Glu542Lys | 17 | |

| CD31-positive and CD34-negative cells (LEC) | p.Glu542Lys | 32 | |

| CD31- and CD34-negative cells | p.Glu542Lys | 0 | |

| Fibroblasts | p.Glu542Lys | 0 |

VAF, variant allele frequency; EC, endothelial cell; BEC, blood endothelial cell; LEC, lymphatic endothelial cell

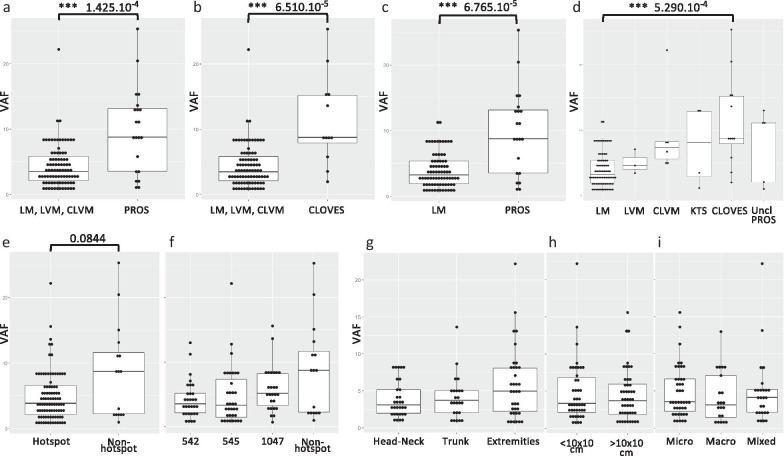

We detected a statistically significant difference in the distribution of hotspot mutations and non-hotspot mutations between common and combined LM compared to the syndromes (p value = 1.329 × 10–7), to CLOVES (p value = 1.441 × 10–5) or to unclassified PROS (p value = 1.207 × 10–4), but not to KTS (Fig. 3 and Table 3). Our meta-analysis of data collected from published reports detected a similar but weaker difference for CLOVES (p value = 0.0023) [6–8, 10, 13, 14]. When combining our data with the literature, the mutation distribution difference was significant between common and combined LMs versus PROS (p value = 7.742 × 10–5) and versus CLOVES (p value = 5.575 × 10–7). All p values adjusted for multiple testing remained significant (Table 3). As earlier reports focussed on hotspot screenings, it probably explains the weaker association in the literature data. Out of the altogether 367 patients reported by us and others, 54 (14.7%) are PIK3CA-negative: 38 LM, 1 CLM, 3 CLVM, 1 KTS, 4 CLOVES, 5 PROS and 2 UVA. Some of these could just be under the threshold of detection.

Fig. 3.

Genotype distribution of PIK3CA mutations between patients with common and combined LMs or PROS. Distribution of hotspot mutations (dark colours, affecting amino acid positions 542, 545 or 1047) and non-hotspot mutations (light colours, all other amino acid positions) in patient cohorts. C&C LMs (Common and combined LMs) includes LM, LVM and CLVM. PROS, includes CLOVES, KTS and unclassified (Uncl) PROS (shown separately in blue). Literature: from references [6–8, 10, 13, 14]. Combined: this study and the literature. See Table 3 for values. ***p value < 0.001. **p value < 0.01

Table 3.

Comparison of the mutation types between the different cohorts

| Number of patients | Pathology | Hotspot | Non-hotspot | Fisher's Exact Test | p value | Adjusted p value | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | n = 87 | C&C LMs | 83 | 4 | ||||

| n = 21 | PROS | 9 | 12 | C&C LMs vs PROS | 1.329e-07 | 1.5948e-06 | *** | |

| 12 | CLOVES | 5 | 7 | C&C LMs vs CLOVES | 1.441e-05 | 5.764e-05 | *** | |

| 4 | KTS | 3 | 1 | C&C LMs vs KTS | 0.2055 | 0.274 | ||

| 5 | Uncl PROS | 1 | 4 | C&C LMs vs Uncl PROS | 0.0001207 | 0.0002896 | *** | |

| Literature | n = 107 | C&C LMs | 100 | 7 | ||||

| n = 98 | PROS | 85 | 13 | C&C LMs vs PROS | 0.1562 | 0.2343 | ||

| 47 | CLOVES | 35 | 12 | C&C LMs vs CLOVES | 0.002331 | 0.004662 | ** | |

| 20 | KTS | 20 | 0 | C&C LMs vs KTS | 0.5955 | 0.7146 | ||

| 31 | Uncl PROS | 30 | 1 | C&C LMs vs Uncl PROS | 0.6832 | 0.7453 | ||

| Combined | n = 194 | C&C LMs | 183 | 11 | ||||

| n = 119 | PROS | 94 | 25 | C&C LMs vs PROS | 7.742e-05 | 2.232e-04 | *** | |

| 59 | CLOVES | 40 | 19 | C&C LMs vs CLOVES | 5.575e-07 | 3.345e-06 | *** | |

| 24 | KTS | 23 | 1 | C&C LMs vs KTS | 1 | 1 | ||

| 36 | Uncl PROS | 31 | 5 | C&C LMs vs Uncl PROS | 0.1434 | 0.2343 |

C&C (common and combined) LMs: LM, LVM, CLVM. PROS: includes CLOVES, KTS and unclassified (Uncl) PROS. Detailed values of PROS subgroups are given in italic. Literature: from references [6–8, 10, 13, 14]. Combined: this study and the literature. **p value < 0.01; ***p value < 0.001. The distributions between hotspot and non-hotspot are shown in Fig. 3

We also studied variability of VAF in different samples of the same patient. We had 16 patients for which 2, 3 or 4 samples were analysed (Table 4). A mutation was found in 14. The detected allele frequencies had a mean average of 5.17%, with an SD of 2.36%. For each patient, the same mutation was identified in all tissues. The two patients without an identified somatic mutation, were each negative in 3 different samples.

Table 4.

Patients with multiple samples analysed

| Sequenced samples | Common code | Pathology | Mutation | VAF (%) | Average VAF (%) | SD VAF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA-10 | VA-10 | LM | E545G | 10.01 | 8.28 | 2.45 |

| VA-47.pKPT | E545G | 6.55 | ||||

| VA-1124.pKPT | VA-1124 | CLOVES | E453K | 13.51 | 8.64 | 6.89 |

| VA-1133.pKPT | E453K | 3.76 | ||||

| VA-1126.pKPT | VA-1126 | CLOVES | – | – | – | – |

| VA-1126.pRASO2 | – | – | ||||

| VA-1126-T.pCMAVM | – | – | ||||

| VA-1158-T.pKPT | VA-1158-T | CLOVES | E545K | 12.16 | 8.66 | 4.17 |

| VA-1158-T-1.pTVPP | E545K | 9.77 | ||||

| VA-1158-T-2.pTVPP | E545K | 4.05 | ||||

| VA-230.pKPT | VA-230 | LM | H1047L | 2.52 | 2.50 | 0.04 |

| VA-298.pKPT | H1047L | 2.47 | ||||

| VA-24.pKPT | VA-24 | LM | – | – | – | – |

| VA-240.pKPT | – | – | ||||

| VA-986.pKPT | – | – | ||||

| VA-312.pKPT | VA-312 | LM | E110delE | 1.06 | 1.90 | 0.82 |

| VA-339.pKPT | E110delE | 1.95 | ||||

| VA-403.pKPT | E110delE | 2.70 | ||||

| VA-364.pKPT | VA-364 | LM | E542K | 1.11 | 2.74 | 2.30 |

| VA-421.pKPT | E542K | 4.36 | ||||

| VA-50.pKPT | VA-50 | LM | E542K | 4.95 | 6.56 | 2.28 |

| VA-790.pKPT | E542K | 8.17 | ||||

| VA-528.pKPT | VA-528 | LM | E545K | 4.3 | 4.93 | 2.39 |

| VA-714.pKPT | E545K | 6.24 | ||||

| VA-830.pKPT | E545K | 7.32 | ||||

| VA-913.pKPT | E545K | 1.87 | ||||

| VA-711.pKPT | VA-711 | LM | H1047R | 5.66 | 8.33 | 3.77 |

| VA-829.pKPT | H1047R | 10.99 | ||||

| VA-756.pKPT | VA-756 | LVM | E542K | 8.25 | 7.07 | 1.67 |

| VA-979.pKPT | E542K | 5.89 | ||||

| VA-1037.pKPT | VA-886 | LM | Q546R | 2.16 | 3.06 | 1.27 |

| VA-886.pKPT | Q546R | 3.96 | ||||

| VA-868-T.pRASO2 | VA-868 | LM | E542K | 2.11 | 3.78 | 2.36 |

| VA-1245.pKPT | E542K | 5.45 | ||||

| VA-869-T.pRASO2 | VA-869 | LM | E545K | 4.0 | 2.87 | 1.61 |

| VA-1243.pKPT | E545K | 1.73 | ||||

| VA-1041.pKPT | VA-916 | LM | H1047R | 3.86 | 3.10 | 1.08 |

| VA-916.pKPT | H1047R | 2.33 |

VAF, variant allele frequency; SD, standard deviation; mean of averages = 5.17%; mean of SDs = 2.36%

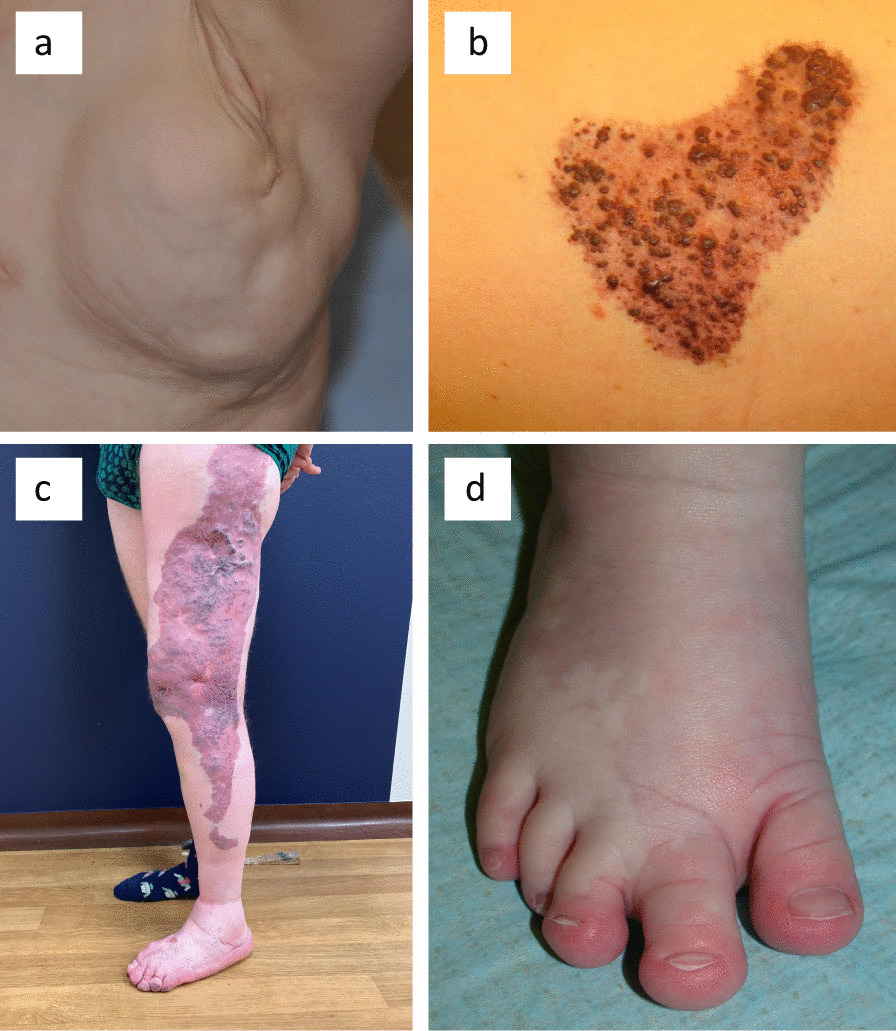

Overall, VAF varied from 0.54 to 25.33% between different phenotypes (Table 1). There was a statistically highly significant difference in VAF between common and combined LMs versus syndromes (PROS) (p value = 1.425 × 10–4, Fig. 4a) and versus CLOVES (p value = 6.510 × 10–5, Fig. 4b), as well as between common LMs versus syndromes (PROS) (p value = 6.765 × 10–5, Fig. 4c) and versus CLOVES (p value = 5.290 × 10–4, Fig. 4d). There was no statistically significant difference between the other entities (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Fig. 4.

VAF distributions. a Highly significant difference in VAF between common and combined LMs (LM, LVM,CLM) versus syndromes (PROS), and b versus CLOVES. No statistically significant difference between common and combined LMs versus unclassified PROS or KTS, nor between LVM or CLVM versus syndromes. c Significant difference between common LM versus syndromes (PROS), and d versus CLOVES. There was no statistically significant difference between any other entities (Additional file 1: Table S1). e, f, no statistically significant difference between VAF and hostpot/non-hotspot or each of the hotspots individually (Additional file 1: Table S1). g–i no statistically significant differences between VAF and LM localization (g) (Additional file 1: Table S1), size (h) (Additional file 1: Table S1) or cystic structure (i) (Additional file 1: Table S1). ***p value < 0.001

The VAF for hotspot mutations varied between 0.54 and 22.19% (n = 92, median: 3.88%, SD = 3.72), whereas for the non-hotspot mutations it varied between 1 and 25.33% (n = 16, median = 8.71%, SD = 7.27). There was no statistically significant difference between these two groups (p value = 0.0844) (Fig. 4e) or with individual hotspots (Fig. 4f, Additional file 1: Table S1). Finally, we analysed associations between VAF (Fig. 4g–i and Additional file 1: Table S1) or mutations (hotspot vs non-hotspot or presence vs absence) in regard to LM localization (Table 5), size (Table 6) or cystic structure (Table 7). There was no statistically significant difference identified in adjusted p values, except that a mutation is less often detected in small lesions (p value = 0.0129) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Comparison of mutations versus localisation

| Localisation | Mutation | Hotspot | Non-hotspot | No mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input data | ||||

| Head & Neck | 32 | 31 | 1 | 12 |

| Trunk | 25 | 23 | 2 | 11 |

| Extremities | 40 | 37 | 4 | 8 |

| group_1 | group_2 | p value | Adjusted p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher's exact test Mutation/no mutation | ||||

| Head & Neck | Trunk | 0.8068 | 0.8068 | |

| Head & Neck | Extremities | 0.3118 | 0.4677 | |

| Trunk | Extremities | 0.1877 | 0.4677 | |

| Fisher's exact test Hotspot/non-hotspot | ||||

| Head & Neck | Trunk | 0.5762 | 0.8643 | |

| Head & Neck | Extremities | 0.3732 | 0.8643 | |

| Trunk | Extremities | 1 | 1 |

Table 6.

Comparison of mutations versus lesional size

| Size | Mutation | Hotspot | Non-hotspot | No mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input data | ||||

| < 10 × 10 cm | 46 | 45 | 1 | 23 |

| > 10 × 10 cm | 50 | 44 | 6 | 8 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| group_1 | group_2 | p value | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher's exact test Mutation/no mutation | ||||

| < 10 × 10 cm | > 10 × 10 cm | 0.01285 | * |

| group_1 | group_2 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher's exact test Hotspot/non-hotspot | ||||

| < 10 × 10 cm | > 10 × 10 cm | 0.1134 |

*p value < 0.05

Table 7.

Comparison of mutations versus cystic structure

| Cystic structure | Mutation | Hotspot | Non-hotspot | No mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input data | ||||

| Microcystic | 48 | 43 | 5 | 14 |

| Macrocystic | 21 | 21 | 0 | 13 |

| Mixed | 28 | 26 | 2 | 4 |

| Unknown | 11 | 2 | 9 | 4 |

| group_1 | group_2 | p value | Adjusted p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher's exact test Mutation/no mutation | ||||

| Microcystic | Macrocystic | 0.1536 | 0.2304 | |

| Microcystic | Mixed | 0.2815 | 0.2815 | |

| Macrocystic | Mixed | 0.0241 | 0.0722 |

| group_1 | group_2 | p value | Adjusted p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher's exact test Hotspot/non-hotspot | ||||

| Microcystic | Macrocystic | 0.3132 | 0.7500 | |

| Microcystic | Mixed | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Macrocystic | Mixed | 0.5000 | 0.7500 |

Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 5.906, df = 3, p value = 0.1163

Discussion

We used deep sequencing and ddPCR to study a series of lymphatic malformations. Variant allele frequency ranged from 0.54 to 25.33%, suggesting that the most clonal surgical resections contained up to 50% of heterozygous mutant cells. In contrast, in the least clonal lesion detected, the frequency was as low as 1% of cells. VAF in common and combined LMs had a median of 3.50% (SD = 3.24); it was more than double in PROS samples (median = 8.78%, SD = 6.47). These are similar to the ranges previously reported [13, 14]. The higher mutant allele frequency detected in PROS patients suggests broader mosaicism.

We identified a statistically significant association between mutation types and phenotypes. The non-hotspot mutations had a higher frequency in CLOVES and unclassified PROS compared to common and combined LMs (Fig. 3). Similar has been noted for macrocephaly-capillary malformation (M-CM) in which PIK3CA mutations are more often non-hotspot mutations [15]. Moreover, M-CM patients tend to be more mosaic for the mutation, which is sometimes detectable in their blood [15]. The level of mosaicism in human tissues may reflect the potential pathogenicity (the strength of downstream gain-of-function effects) of a given mutation. This suggests that the non-hotspot mutations that are more frequently seen in widespread PROS (such as CLOVES and M-CM) may have weaker downstream effects and thus could occur earlier during fetal development, thereby affecting more extensive body parts. Interestingly, when KTS is defined as unilateral capillaro-lymphatico-venous malformation with hypertrophy, like in this study, it seems to have more hotspot mutations, like common and combined LMs which are usually localized.

The same amino acid substitutions are found in cancers resulting in activation of p110α [11]. As vascular anomalies do not transform into malignancy, the activating p110α mutations in ECs are not able to induce oncogenesis. Nevertheless, a study on 122 patients with CLOVES syndrome demonstrated a higher risk of developing a Wilms tumour (WT) [16]. This underscores the likely presence of CLOVES-associated mutations in cell types other than EC. Interestingly, two studies on patients with KTS reported that the risk of cancers in children and adults was not higher than in the general population [17, 18]. These reports fit with our notion that especially CLOVES patients tend to have non-hotspot mutations with higher allelic frequencies. A similar risk may also be true for other PROS patients that have a wider (bilateral) phenotype.

The implication of the same PIK3CA mutation in common LM and common VM reinforces the idea that the cell type in which mutations occur influences directly the pathology [9]. LMs would be due to somatic mutations in lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC), whereas VMs would be due to a mutation in blood endothelial cells (BEC). The cell-type specificity of mutations was underscored by the undetectable presence of the somatic PIK3CA mutation in our LM-derived fibroblasts and our CD-31 negative cells derived from a CLVM. Moreover, there was an increased detection rate of the tissular mutation (11%) in the LM-derived LECs (32%) (Table 2). This reinforces the idea that the somatic mutations occur in ECs or their precursors, determining the phenotype, and contrasts with CLOVES in which fibroblasts also harbour the mutation [19].

Intercellular signalling (mutant and wild-type) and cell–matrix interactions are also likely to play an essential role in the development of vascular malformations. This is highlighted by the single mutant cell type being at very low frequency (< 1%) in the lesion. Moreover, murine modelling demonstrated that the same somatic PIK3CA mutation activated in LECs can lead to macro- or microcystic lesions, depending on the time-point of induction of expression during development and growth [20]. Intra-uterine activation led to macrocystic LMs, whereas early post-natal induction led to microcystic LMs. This fits well with the concept of cell-type and time-dependent occurrence of somatic (hotspot)/mosaic (non-hotspot) mutations explaining variability in phenotype [21].

Our results indicate that PI3K-pathway inhibition could work in at least 75.5% of patients with a lymphatic malformation. In the three published prospective clinical trials using Rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, on patients affected by various vascular malformations, response rates were high [22–25]. In one study, all 6 patients had a somatic mutation activating PI3K signalling and the response rate was 100%. In the other two studies, somatic genotyping had been performed only for a minority of the patients, yet > 85% had at least a partial response after 12 months of treatment. A PIK3CA inhibitor, BYL719 or Alpelisib, was tested on 19 patient with PROS, also showing good outcomes [26]. Similarly, the Pan-ALK inhibitor ARQ 092 (Miransertib) showed promising results on a cohort of 6 patients with PIK3CA-Related Overgrowth Syndrome [27]. These results demonstrate the positive impact of repurposing oncology drugs to patients suffering from benign vascular anomalies with a proven or likely somatic mutation that activates PI3K.

Genotyping is likely crucial in future clinical trials to increase efficacy. The high frequency of mutations identified in this study (75.5%) suggests that LMs are mostly caused by a somatic PIK3CA mutation. However, one fourth does not seem to have a PIK3CA mutation. This could be due to low representativeness of mutant ECs in the studied tissue sample. Analysis of multiple lesional samples may increase rate of molecular diagnosis [14]. Yet, we confirmed negativity in additional samples when available (n = 2 patients), and in the other 14 patients that were sequenced two, three, or four times, the mutation was found in all samples, albeit with variability in VAFs (Table 4).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our systematic data on a large cohort of patients with lymphatic malformations demonstrate that 75.5% of LMs, whether common, combined, or syndromic, are caused by somatic activating PIK3CA mutations. There is a statistically significant difference in mutation types between common and combined LM versus syndromic LMs (CLOVES and unclassified PROS), suggesting differential effects of the mutations. Non-hotspot mutations need to be looked for especially in the more wide-spread PROS phenotypes. Based on these and earlier data, repurposing of PI3K signalling pathway inhibitors for the treatment of LMs, whether isolated, combined or syndromic, have a sound epidemiological and pathophysiological basis.

Methods

Aim

Identification of prevalence of PIK3CA mutations and genotype–phenotype correlations in pure and combined lymphatic malformations.

Design

Tissues were collected from the leftover of programmed surgeries and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Clinical data in regard to the phenotype (Table 1), and localization (head & neck, trunk and extremities), size (smaller or larger than 10 × 10 cm) and cystic structure (micro, macro, mixed) of the lesions were collected (Table 8). Nine of the patients have been included in earlier reports: one KTS as patient #5 in (9) and the associated E545K mutation in (11); five common LMs with H1047R with histology as patients #1–5 in (22), and two LMs (patients #2 and #6) as well as one KTS (patient #18) in a clinical trial (25).

Table 8.

Summary of samples per cystic structure, size and localisation

| Cystic structure | Mutation | Hotspot | Non-hotspot | No mutation | Total | % mutation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size* | 542K | 545K | 1047 | ||||||

| Microcystic | 48 | 43 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 5 | 14 | 62 | 77% |

| < 10 × 10 cm | 20 (7/4/9) | 19 (7/3/9) | 10 | 4 | 5 | 1 (0/1/0) | 9 (3/3/3) | 29 | 69% |

| > 10 × 10 cm | 27 (6/10/11) | 23 (5/9/9) | 4 | 11 | 8 | 4 (1/1/2) | 5 (0/2/3) | 32 | 84% |

| Unknown | 1 (0/1/0) | 1 (0/1/0) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% |

| Macrocystic | 21 | 21 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 13 | 34 | 62% |

| < 10 × 10 cm | 16 (7/2/7) | 16 (7/2/7) | 6 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 12 (5/6/1) | 28 | 57% |

| > 10 × 10 cm | 5 (2/1/2) | 5 (2/1/2) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 (1/0/0) | 6 | 83% |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Mixed | 28 | 26 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 88% |

| < 10 × 10 cm | 10 (4/3/3) | 10 (4/3/3) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 (2/0/0) | 12 | 83% |

| > 10 × 10 cm | 18 (6/4/8) | 16 (6/4/6) | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 (0/0/2) | 2 (1/0/1) | 20 | 90% |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Unknown | 11 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 15 | 73% |

| Total | 108 | 92 | 31 | 35 | 26 | 16 | 35 | 143 | 76% |

Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) or ddPCR to screen for somatic PIK3CA mutations on DNA extracted from resected lesional tissue or lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) isolated from lesions.

DNA extraction

DNA extraction from frozen tissues as previously described [9]. DNA was quantified using NanoDrop 8000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Qubit 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Isolation and culturing of primary endothelial cells (EC) and primary lymphatic ECs

Single-cell solutions were obtained from CLVM and LM tissues by digesting with 0.04% dispase (Gibco), 0.25% collagenase II (Roche) and 0.01% DNAse I (Roche) for 1 h at 37 °C. Separated cells (= mixed cells) were seeded on fibronectin-coated flasks (2 μg/cm2) (Millipore) and grown in ECGM2 (Bio-Connect life sciences) for CLVM isolated cells and ECGM-MV2 (Bio-Connect life sciences) for LM isolated cells, both supplemented with penicillin–streptomycin. When mixed cells reached a confluency of 80%, they were detached using Accutase (Sigma). Mixed CLVM cells were sorted for CD31-positive cells using Anti-CD31 MicroBeads (Miltenyi). To obtain LECs, we performed a fibroblast depletion using Anti-fibroblast MicroBeads (Miltenyi) as well as CD34-positive blood EC depletion using Anti-CD34 MicroBeads (Miltenyi), followed by a CD31-positive selection using Anti-CD31 MicroBeads. All different selected cells were plated on fibronectin-coated flasks (2 μg/cm2). Cell morphology was confirmed using a bright field microscope (Zeiss).

PIK3CA sequencing

We designed an Ion AmpliSeq panel for targeted sequencing of the 21 coding exons of PIK3CA and ten nucleotides of all flanking introns (NM_006218.2) (http://www.ampliseq.com). Theoretical horizontal coverage was 96.75%, with 16 bp in the 5’UTR (exon 1) and 32 bp in exon 20 not covered. The panel consisted of 2 pools of primers for multiplexed PCR-amplification with Ion Ampliseq Library kit, and sequencing on an Ion Personal Genome Machine (PGM) or an ion Proton (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reads were aligned to the human reference sequence hg19, using the Torrent Suite Server. Bam files were imported into Highlander software package (https://sites.uclouvain.be/highlander/) for analysis. We selected variants with at least 5 mutant reads representing at minimum 1% of all alleles by interrogating all positions reported with at least 4 changes in the COSMIC database (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic). Samples needed to have an average coverage above 500 × to be considered not to contain a mutation. Mutations with a VAF below 1% but confirmed by ddPCR when DNA was available, were considered to contain a mutation.

Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR)

Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) was used to study four known PIK3CA hotspot mutations: c.1624G > A (p.E542K), c.1633G > A (p.E545K), c.3140A > T (p.H1047L) and c.3140A > G (p.H1047R) (NM_006218.2). Probes were designed by Bio-Rad (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The ddPCR experiments were performed, as described by Hindson et al. [28]. DNA input was 30 ng. At most, 93 samples were run in parallel. For the analysis, we used QuantaSoft software (Version 1.7). Samples had to have at least 5 mutant single positive droplets (SPD) among a minimum of 10,000 droplets to be considered mutated. Nine patients with detection of mutation by ddPCR could not be tested by NGS. Their variant allele frequencies ranged from 1.6 to 15.6%.

Statistics

Data were analyzed to detect differences between groups using Fisher’s exact test for two categorical variables, Pairwise Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test for group comparisons of continuous variables, and the Kruskal–Wallis test for > 2 group comparisons of continuous variables. Nonparametric tests were used due to small sample size and non-normal distributions (tested with Shapiro test). Significance of p values: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001. In order to control type I errors, multiple testing corrections were performed using Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. All analyses were performed using R and graphs were generated with ggplot2. Descriptive statistics were computed using groupedstats R package. VAF values for statistics were based on NGS results (average VAF values for patients with multiple sequencing, Table 4) or ddPCR (for 10 samples tested only by ddPCR).

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Statistical comparisons of data shown in Fig. 4 d,f, g, h, i.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients for their invaluable participation. The authors thank Liliana Niculescu for secretarial help, and Audrey Debue and Fabrice Cahay for technical assistance. Five of the authors of this publication are members of the Vascular Anomalies Working Group (VASCA WG) of the European Reference Network for Rare Multisystemic Vascular Diseases (VASCERN)—Project ID: 769036.

Authors’ contributions

MJS, NHS and EF carried out the DNA extractions, ddPCR and NGS panel experiments. PB and MJS analysed the data. RH developed bioinformatic tools for the analysis of somatic mutations within Highlander. AQ carried out the cell biology experiments. SB performed the statistical analyses. SS, PC, FH, AD, AWT, JL, LP, CV and LMB collected medical information and blood samples. MV conceived and coordinated the study. MJS and PB drafted the manuscript. PB and MV helped to develop the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

These studies were financially supported by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique—FNRS Grants T.0026.14 (to MV) and T.0146.16 (to LB), the Fund Generet managed by the King Baudouin Foundation (to MV), and by la Région wallonne dans le cadre du financement de l’axe stratégique FRFS-WELBIO (to MV). P.B. is a Scientific Logistics Manager of the Genomics Platform of University of Louvain. The authors thank the Genomics Platform of University of Louvain for IonTorrent PGM Next Generation Sequencing. We also thank the National Lottery, Belgium and the Foundation against Cancer (2010–101), Belgium for their support to the Genomics Platform of University of Louvain and de Duve Institute, as well as the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique—FNRS Equipment Grant U.N035.17 for the «Big data analysis cluster for NGS at UCL». MS and EF were doctoral students supported by the Fonds pour la Formation à la Recherche dans l’Industrie et dans l’Agriculture (FRIA).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained for all patients, as approved by the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty at the University of Louvain, Brussels, Belgium (ref B403201629786) and the local committees of collaborators.

Consent for publication

All patients gave consent to publish the pictures shown in Fig. 1.

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Pascal Brouillard and Matthieu J. Schlögel have contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Pascal Brouillard, Email: pascal.brouillard@uclouvain.be.

Matthieu J. Schlögel, Email: matthieu.schlogel@uclouvain.be

Nassim Homayun Sepehr, Email: nassim.homayun@uclouvain.be.

Raphaël Helaers, Email: raphael.helaers@uclouvain.be.

Angela Queisser, Email: angela.queisser@uclouvain.be.

Elodie Fastré, Email: elodie.fastre@uclouvain.be.

Simon Boutry, Email: simon.boutry@uclouvain.be.

Sandra Schmitz, Email: sandra.schmitz@uclouvain.be.

Philippe Clapuyt, Email: philippe.clapuyt@uclouvain.be.

Frank Hammer, Email: frank.hammer@uclouvain.be.

Anne Dompmartin, Email: dompmartin-a@chu-caen.fr.

Annamaria Weitz-Tuoretmaa, Email: annamaria.weitz@gmail.com.

Jussi Laranne, Email: jussilaranne@me.com.

Louise Pasquesoone, Email: louise.pasquesoone@chu-lille.fr.

Catheline Vilain, Email: catheline.vilain@erasme.ulb.ac.be.

Laurence M. Boon, Email: laurence.boon@uclouvain.be

Miikka Vikkula, Email: miikka.vikkula@uclouvain.be.

References

- 1.Wassef M, Blei F, Adams D, Alomari A, Baselga E, Berenstein A, et al. Vascular anomalies classification: recommendations from the international society for the study of vascular anomalies. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e203–e214. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limaye N, Boon LM, Vikkula M. From germline towards somatic mutations in the pathophysiology of vascular anomalies. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(R1):R65–74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dekeuleneer V, Seront E, Van Damme A, Boon LM, Vikkula M. Theranostic advances in vascular malformations. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(4):756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlögel M, Brouillard P, Boon L, Vikkula M. Molecular genetics of lymphatic and complex vascular malformations. In: Lee BB, Rockson SG, editors. Lymphedema: a concise compendium of theory and practice. 2. Berlin: Springer; 2018. pp. 753–764. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keppler-Noreuil KM, Sapp JC, Lindhurst MJ, Parker VE, Blumhorst C, Darling T, et al. Clinical delineation and natural history of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164(7):1713–1733. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boscolo E, Coma S, Luks VL, Greene AK, Klagsbrun M, Warman ML, et al. AKT hyper-phosphorylation associated with PI3K mutations in lymphatic endothelial cells from a patient with lymphatic malformation. Angiogenesis. 2015;18(2):151–162. doi: 10.1007/s10456-014-9453-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osborn AJ, Dickie P, Neilson DE, Glaser K, Lynch KA, Gupta A, et al. Activating PIK3CA alleles and lymphangiogenic phenotype of lymphatic endothelial cells isolated from lymphatic malformations. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(4):926–938. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luks VL, Kamitaki N, Vivero MP, Uller W, Rab R, Bovee JV, et al. Lymphatic and other vascular malformative/overgrowth disorders are caused by somatic mutations in PIK3CA. J Pediatr. 2015;166(4):1048–54 e1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Limaye N, Kangas J, Mendola A, Godfraind C, Schlogel MJ, Helaers R, et al. Somatic activating PIK3CA mutations cause venous malformation. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(6):914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keppler-Noreuil KM, Parker VE, Darling TN, Martinez-Agosto JA. Somatic overgrowth disorders of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway & therapeutic strategies. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2016;172(4):402–421. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304(5670):554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke JE, Perisic O, Masson GR, Vadas O, Williams RL. Oncogenic mutations mimic and enhance dynamic events in the natural activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110alpha (PIK3CA) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(38):15259–15264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205508109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurek KC, Luks VL, Ayturk UM, Alomari AI, Fishman SJ, Spencer SA, et al. Somatic mosaic activating mutations in PIK3CA cause CLOVES syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(6):1108–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zenner K, Cheng CV, Jensen DM, Timms AE, Shivaram G, Bly R, et al. Genotype correlates with clinical severity in PIK3CA-associated lymphatic malformations. JCI Insight. 2019;4(21):e129884. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.129884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riviere JB, Mirzaa GM, O'Roak BJ, Beddaoui M, Alcantara D, Conway RL, et al. De novo germline and postzygotic mutations in AKT3, PIK3R2 and PIK3CA cause a spectrum of related megalencephaly syndromes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):934–940. doi: 10.1038/ng.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterman CM, Fevurly RD, Alomari AI, Trenor CC, 3rd, Adams DM, Vadeboncoeur S, et al. Sonographic screening for Wilms tumor in children with CLOVES syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(12). 10.1002/pbc.26684. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Blatt J, Finger M, Price V, Crary SE, Pandya A, Adams DM. Cancer risk in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Lymphat Res Biol. 2019;17(6):630–636. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2018.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene AK, Kieran M, Burrows PE, Mulliken JB, Kasser J, Fishman SJ. Wilms tumor screening is unnecessary in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):e326–e329. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.e326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loconte DC, Grossi V, Bozzao C, Forte G, Bagnulo R, Stella A, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of three different postzygotic mutations in PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS) patients: effects on PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling and sensitivity to PIK3 inhibitors. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0123092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Corral I, Zhang Y, Petkova M, Ortsater H, Sjoberg S, Castillo SD, et al. Blockade of VEGF-C signaling inhibits lymphatic malformations driven by oncogenic PIK3CA mutation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2869. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16496-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Damme A, Seront E, Dekeuleneer V, Boon LM, Vikkula M. New and emerging targeted therapies for vascular malformations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(5):657–668. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00528-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boscolo E, Limaye N, Huang L, Kang KT, Soblet J, Uebelhoer M, et al. Rapamycin improves TIE2-mutated venous malformation in murine model and human subjects. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(9):3491–3504. doi: 10.1172/JCI76004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammer J, Seront E, Duez S, Dupont S, Van Damme A, Schmitz S, et al. Sirolimus is efficacious in treatment for extensive and/or complex slow-flow vascular malformations: a monocentric prospective phase II study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0934-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammill AM, Wentzel M, Gupta A, Nelson S, Lucky A, Elluru R, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(6):1018–1024. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seront E, Van Damme A, Boon LM, Vikkula M. Rapamycin and treatment of venous malformations. Curr Opin Hematol. 2019;26(3):185–192. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venot Q, Blanc T, Rabia SH, Berteloot L, Ladraa S, Duong JP, et al. Targeted therapy in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome. Nature. 2018;558(7711):540–546. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranieri C, Di Tommaso S, Loconte DC, Grossi V, Sanese P, Bagnulo R, et al. In vitro efficacy of ARQ 092, an allosteric AKT inhibitor, on primary fibroblast cells derived from patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS) Neurogenetics. 2018;19(2):77–91. doi: 10.1007/s10048-018-0540-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hindson BJ, Ness KD, Masquelier DA, Belgrader P, Heredia NJ, Makarewicz AJ, et al. High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem. 2011;83(22):8604–8610. doi: 10.1021/ac202028g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Statistical comparisons of data shown in Fig. 4 d,f, g, h, i.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.