Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Surgery is a common gateway to opioid-related morbidity. Ambulatory anorectal cases are common, with opioids widely prescribed, but limited data on their role in this crisis. We sought to determine prescribing trends, new persistent opioid use (NPOU) rates, and factors associated with NPOU after ambulatory anorectal procedures.

METHODS:

The Optum Clinformatics® claims database was analyzed for opioid-naïve adults undergoing outpatient hemorrhoid, fissure, or fistula procedures from 1/1/2010–6/30/2017. The main outcome measure was the rate of NPOU after anorectal cases. Secondary outcomes were annual rates of perioperative opioid fills and the prescription size over time (oral morphine equivalents [OMEs]).

RESULTS:

23,426 cases were evaluated- 69.09%(n=16,185) hemorrhoids, 24.29%(n=5,690) fissures, and 6.45%(n=1,512) fistulas. The annual rate of perioperative opioid fills decreased on average 1.2%/year, from 72% in 2010 to 66% in 2017(p<0.001). Prescribing rates were consistently highest for fistulas, followed by hemorrhoids, then fissures(p<0.001). There was a significant reduction in prescription size(OME) over the study period, with a median OME(IQR) of 280(250–400) in 2010 and 225(150–375) in 2017(p<0.0001). Overall, 2.1%(n=499) developed NPOU. Logistic regression found NPOU was associated with additional perioperative opioid fills(OR 3.92; 95% CI:2.92–5.27; p<0.0001), increased comorbidity(OR 1.15; CI:1.09–1.20; p<.00001), tobacco use(OR 1.79; CI:1.37–2.36; p<0.0001), and pain disorders(OR, 1.49; CI, 1.23–1.82); there was no significant association with procedure performed.

CONCLUSIONS:

Over 2% of ambulatory anorectal procedures develop NPOU. Despite small annual reductions in opioid prescriptions, there has been little change in the amount prescribed. This demonstrates a need to develop and disseminate best practices for anorectal surgery, focusing on eliminating unnecessary opioid prescribing.

Keywords: Opioids, Opioid-naïve, Opioid prescribing, Anorectal Surgery, Ambulatory Surgery, New Persistent Opioid Use, Hemorrhoid, Fissure, Fistula

Article Summary:

Analysis from a national claims database of opioid-naïve adults undergoing outpatient hemorrhoid, fissure, or fistula procedures was performed for rates of opioid prescribing, new persistent opioid use (NPOU), and prescription size over time. The importance is the prevalence of opioid prescribing and NPOU after seemingly “low risk” anorectal cases, and the need to extend opioid-sparing pain management to these common procedures.

Introduction

There is an opioid epidemic in the United States, with cases of misuse, dependence, diversion, and overdose deaths continually rising1–3. The epidemic has a staggering economic burden on the healthcare system, with prescription opioid misuse alone estimated to cost at $78.5 billion per year and the total economic impact of the opioid crisis estimated at $504 billion annually4, 5. Opioid use, even in opioid-naïve patients, during a surgical episode can be a gateway to chronic use, abuse and overdose fatalities1, 2, 6. Furthermore, previously opioid-naïve patients may convert to new persistent opioid use after surgery, which is associated with substantial morbidity, mortality and healthcare utilization7–11.

Ambulatory surgery cases are studied less often in the context of this crisis, but may be a major contributor to the opioid epidemic. In the United States, an estimated 48.3 million ambulatory surgical procedures are performed annually12. For minor ambulatory procedures, opioids are prescribed in quantities several times more than what is needed or taken by patients13–19. The subsequent rates of new persistent opioid use (NPOU) after minor ambulatory surgery are comparable to rates after major surgery of 5–10%; (5.9% to 6.5%)14, 20–23. There is little work to date on the rates and outcomes from opioids prescribed after ambulatory colorectal surgery procedures. In colorectal surgery, ambulatory anorectal procedures are common and opioids are assumed widely prescribed13. Thus, there is potential to impact a large number of patients with further study on the trends and contribution of ambulatory anorectal procedures to opioid use.

Our goal was to determine the prescribing trends, rate of new persistent opioid use (NPOU) and factors associated with NPOU after ambulatory anorectal procedures. Our hypothesis was that there are high rates of perioperative opioid prescribing, which would be independently associated with the development of NPOU after ambulatory anorectal procedures.

Materials and Methods

The Data Source

A cohort study was performed for opioid-naïve patients who underwent an outpatient hemorrhoid, fissure, or fistula procedure from 1/1/2010–6/30/2017 using Optum’s de-identifed Clinformatics® Data Mart Database. Optum Clinformatics™ Data Mart is an administrative health claims database from a large national managed care insurer that includes the enrollment records, medical, hospital, and prescription claims for more than 200 million individuals. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the exempt status of this study as all data was de-identified. This project was registered with OptumInsight Data.

Patient Population

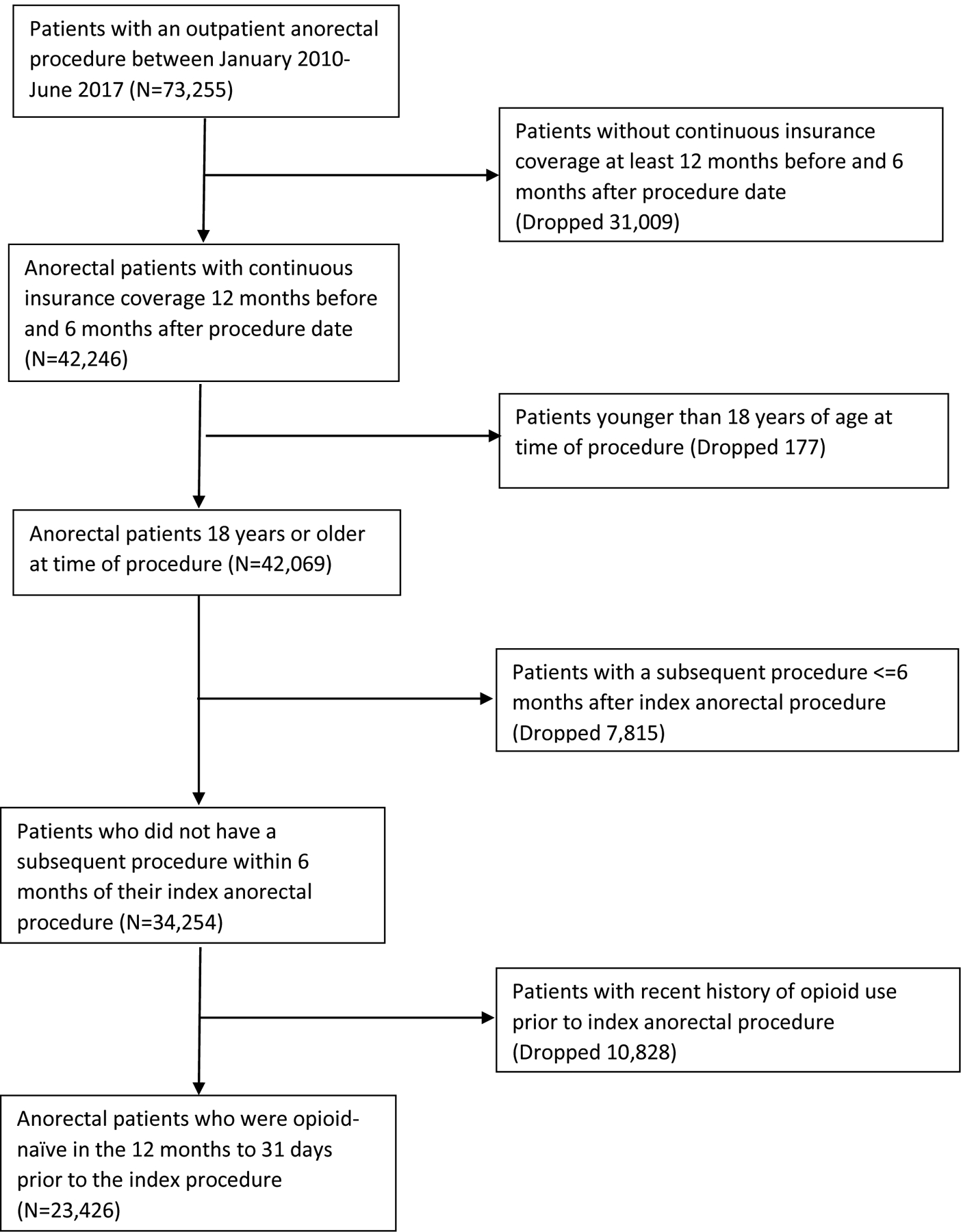

Patients were included in the analysis if over 18 years of age, if the procedure was performed on an ambulatory/ outpatient basis, performed through an anorectal approach, fell under the diagnosis of hemorrhoids, fissure, or fistula by International Classification of Disease 10th edition (ICD-10) diagnosis codes K60.2, L98.8, K60.3, K50.913, K50.10, K50.911, K50.913, K50.914, K64.1, K64.2, K64.3, K64.4, K64.5, K64.6, K64.7, K64.8, K64.9, and had a procedure to address a hemorrhoid, fissure, or fistula, per Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes (Appendix 1). If an individual had more than one qualifying procedure during the study period, the earliest procedure was selected to create a unique cohort. The cohort was further limited to those with continuous insurance and prescription coverage for at least one year before their procedure and 6 months after. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years old on the day of their procedure, if the case was performed in the inpatient setting, or with a planned same-day admission. Patients who had additional procedures in the 6 months following their index anorectal procedure were further excluded to mitigate the confounding of prescription opioid use not related to the index anorectal procedure. Lastly, patients were excluded who filled an opioid prescription from 12 months to 1 month prior to the procedure to produce an opioid-naïve cohort14. Patients who only filled opioids in the month prior to surgery were included to account for the common practice of providing opioid prescriptions intended for postoperative use prior to surgery for patient convenience. The inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the final analytical cohort are summarized in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Patient inclusion/exclusion.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the rate of new persistent opioid use (NPOU) following common ambulatory anorectal cases. Patients developing new persistent use were defined by fulfillment of an opioid a prescription both in the first 90 day period after surgery (excluding the perioperative prescription) and 91–180 days period following surgery10, 14. In the event that a patient filled a prescription in the perioperative period, as defined below, and filled another prescription following surgery, the second prescription counted towards the first 90 day period for the NPOU definition. The secondary outcomes were the perioperative opioid prescribing patterns and trends over time for common anorectal cases. These outcomes were measured in terms of unadjusted annual rates of opioid fills and the annual distribution in prescription size during the perioperative window, respectively.

The key exposure variable was an opioid prescription fill during the perioperative period 30 days before the procedure and up to 3 days after surgery. We adjusted for patient- and procedure-level characteristics including age, gender, race, geographic region, highest level of education, comorbidities (by Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI]), and history of tobacco use, mental health conditions, pain disorders, procedure type, and year of procedure. Mental health conditions were identified using the Clinical Classification Software (CCS) from the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality, then categorized as substance use (alcohol and other substance-related), mood (adjustment, anxiety, and mood), disruptive behavior (attention deficit/hyperactivity, conduct and disruptive behavior, and impulse control), and other disorder (personality, psychosis, suicidal/self-harm and miscellaneous). Pain disorders were captured using ICD-9 or 10 codes for arthritis, back, neck, and other pain, which was then converted into a dichotomous variable to represent any pain disorder (Appendix 2).

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests were used to assess unadjusted associations between covariates and new persistent use. Rates of perioperative opioid prescribing by year were calculated for all anorectal procedures. The Cochran-Armitage test was used to detect a linear trend across the annual rates of prescribing. The annual spread of perioperative prescription size was calculated after converting all opioid prescriptions into oral morphine equivalents (OME). Due to the non-parametric distribution of the data regarding opioid prescription size, the Kruskal-Wallis was used to determine whether differences occurred throughout the study years. Lastly, we utilized logistic regression to evaluate the association of NPOU with opioid prescription fill during the perioperative period, adjusting for patient- and procedure-level characteristics. Statistical analyses were performed using 2-sided tests and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

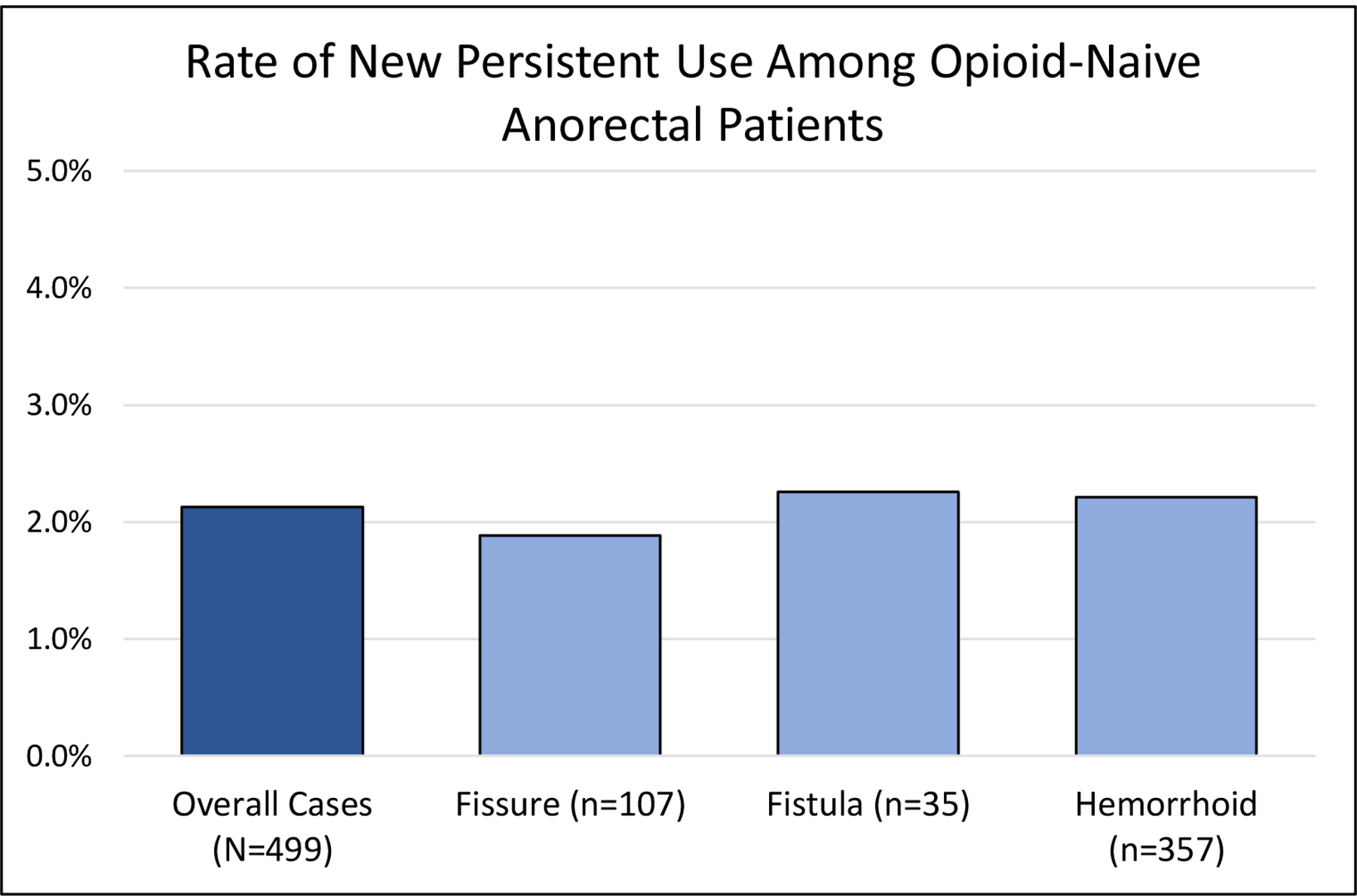

A total of 23,426 opioid-naïve anorectal outpatients met our inclusion criteria to be considered in the analytical cohort, among whom 499 (2.1%) were classified as new persistent users (Figure 2). The cohort included 10,249 (43.8%) female patients, and the median age (IQR) was 50 (40–61) years. Hemorrhoid procedures represented the most common subtype of anorectal procedure in the cohort 16,185 (69.1%), while fissure and fistula made up 5,690 (24.3%) and 1,512 (6.5%), respectively. There were a number of differences in preoperative characteristics between patients that developed new persistent opioid use and those that did not. Mood disorders were more common among new persistent opioid users, 138 (27.7%) compared to patients without persistent use, 4047 (17.7%), as well as those with comorbidities (41.1% vs 29.7%; p<0.001), history of tobacco use (66.5% vs 55.4%; p<0.001), or pain disorders (66.5% vs 54.4%; p<0.001). These data and additional preoperative characteristics between patients that developed NPOU and those that did not are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Rates of NPOU among opioid-naïve anorectal patients

Table 1-.

Patient Demographics, by New Persistent and No New Persistent Opioid Use

| Preoperative Characteristics | Persistent Opioid Use (N=499, 2.1%) | No Persistent Opioid Use (N=22,927, 97.9%) | Total (N=23,426) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 246 (49.3) | 10003 (43.6) | 10249 (43.8) | 0.039 |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–34 | 69 (13.8) | 3281 (14.3) | 3350 (14.3) | 0.065 |

| 35–49 | 150 (30.1) | 8024 (35) | 8174 (34.9) | |

| 50–64 | 176 (35.3) | 6995 (30.5) | 7171 (30.6) | |

| >=65 | 104 (20.8) | 4627 (20.2) | 4731 (20.2) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||

| 0 | 294 (58.9) | 16126 (70.3) | 16420 (70.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 94 (18.8) | 3606 (15.7) | 3700 (15.8) | |

| 2 | 45 (9) | 1445 (6.3) | 1490 (6.4) | |

| 3+ | 66 (13.2) | 1750 (7.6) | 1816 (7.8) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 303 (60.7) | 13395 (58.4) | 13698 (58.5) | 0.001 |

| Black | 42 (8.4) | 1447 (6.3) | 1489 (6.4) | |

| Hispanic | 48 (9.6) | 1963 (8.6) | 2011 (8.6) | |

| Asian | 10 (2) | 1126 (4.9) | 1136 (4.9) | |

| Unknown | 96 (19.2) | 4996 (21.8) | 5092 (21.7) | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than 12th grade | 4 (0.8) | 77 (0.3) | 81 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| High school diploma | 129 (25.9) | 4697 (20.5) | 4826 (20.6) | |

| Less than bachelor degree | 282 (56.5) | 12052 (52.6) | 12334 (52.7) | |

| Bachelor degree and greater | 78 (15.6) | 5516 (24.1) | 5594 (23.9) | |

| Unknown | 6 (1.2) | 585 (2.6) | 591 (2.5) | |

| Region | ||||

| Midwest | 109 (21.8) | 5649 (24.6) | 5758 (24.6) | <0.001 |

| North East | 30 (6) | 2646 (11.5) | 2676 (11.4) | |

| South | 244 (48.9) | 9678 (42.2) | 9922 (42.4) | |

| West | 114 (22.9) | 4872 (21.3) | 4986 (21.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.4) | 82 (0.4) | 84 (0.4) | |

| Procedure | ||||

| Fissure | 107 (21.4) | 5583 (24.4) | 5690 (24.3) | 0.322 |

| Fistula | 35 (7) | 1516 (6.6) | 1551 (6.6) | |

| Hemorrhoid | 357 (71.5) | 15828 (69) | 16185 (69.1) | |

| Procedure Year | ||||

| 2010 | 88 (17.6) | 3549 (15.5) | 3637 (15.5) | 0.022 |

| 2011 | 90 (18) | 3413 (14.9) | 3503 (15) | |

| 2012 | 82 (16.4) | 3271 (14.3) | 3353 (14.3) | |

| 2013 | 52 (10.4) | 3027 (13.2) | 3079 (13.1) | |

| 2014 | 56 (11.2) | 2701 (11.8) | 2757 (11.8) | |

| 2015 | 59 (11.8) | 2639 (11.5) | 2698 (11.5) | |

| 2016 | 53 (10.6) | 2806 (12.2) | 2859 (12.2) | |

| 2017 | 19 (3.8) | 1521 (6.6) | 1540 (6.6) | |

| Mental Health Disorders | ||||

| Mood | 138 (27.7) | 4047 (17.7) | 4185 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Disruptive | 12 (2.4) | 390 (1.7) | 402 (1.7) | 0.231 |

| Substance Abuse | 23 (4.6) | 514 (2.2) | 537 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Other | 28 (5.6) | 658 (2.9) | 686 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Tobacco Use | 76 (15.2) | 1653 (7.2) | 1729 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Pain Disorder | 332 (66.5) | 12479 (54.4) | 12811 (54.7) | <0.001 |

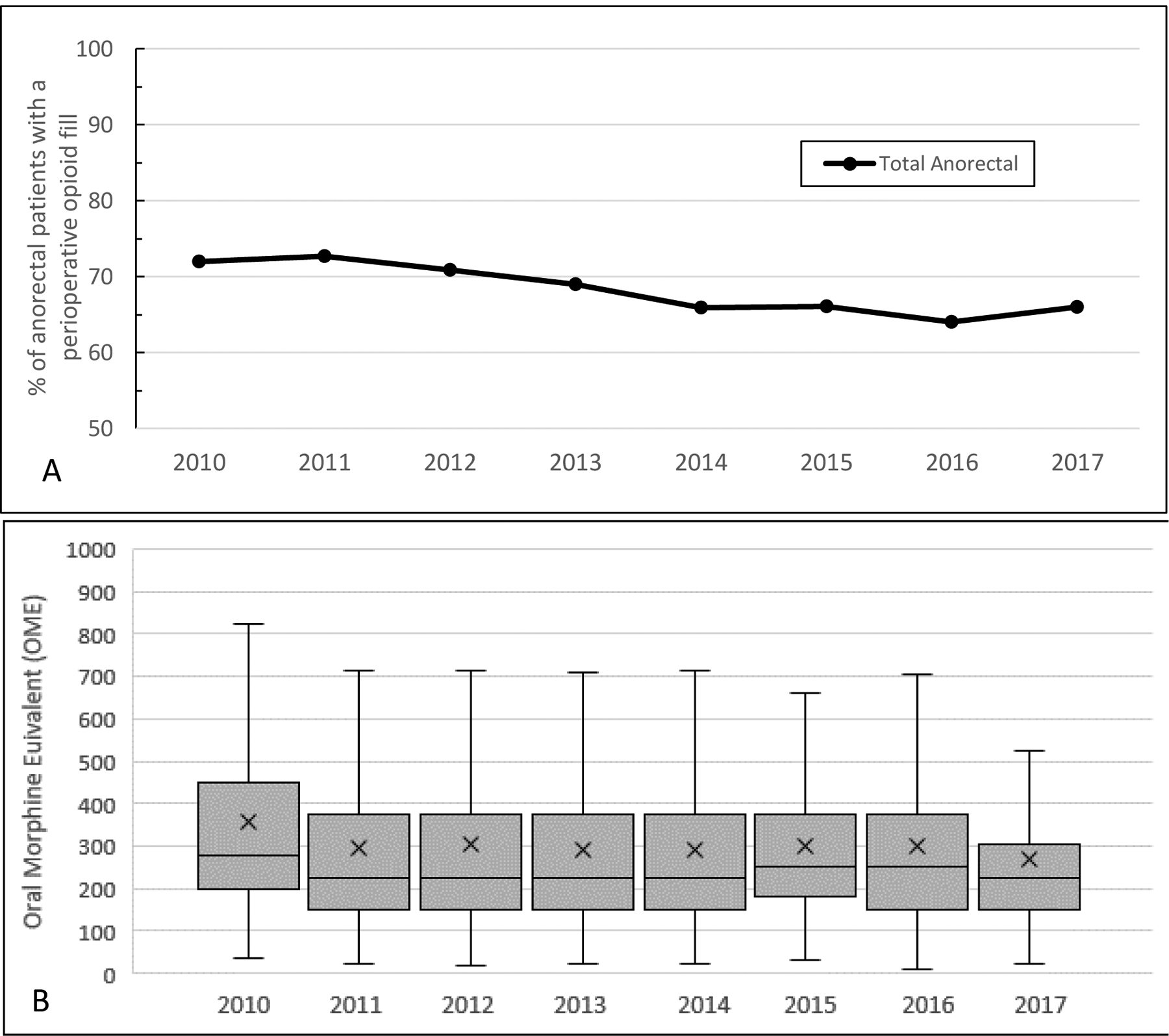

Over the study period, the annual rate of perioperative opioid fills decreased 1.2% per year, from 72% in 2010 to 66% in 2017 (p<0.001) (Figure 3a). The rates were consistently highest for fistulas, followed by hemorrhoids, then fissures. There appeared to be an uptick in prescribing in the first half of 2017, but this may be due to the incomplete 12 months of data and further investigation is needed to determine if this becomes a trend. There was a small but significant reduction in OME over the study period, with a median OME (IQR) of 280 (250–400) in 2010 and 225 (150–375) in 2017(p<0.001) (Figure 3b). Similar to the pattern observed in prescribing rates, fistula patients were prescribed the highest dosages, followed by hemorrhoid and then fissure. Furthermore, patients who filled a prescription perioperatively and developed new persistent use had larger prescription sizes than those who filled perioperatively but did not go on to new persistent use over the entire study period [300 OME (200–450) vs 240 OME (150–375); p<0.001].

Fig. 3.

(A) Annual rates of perioperative opioid prescribing among opioid-naïve anorectal patients. (B) Annual distribution of opioid prescription size among opioid-naïve anorectal patients who filled a prescription during the perioperative period, in OME.

The strongest association with NPOU observed in the multivariable logistic regression model was the exposure to a perioperative prescription fill with an OR 3.92 and 95% CI 2.92–5.27 (p<0.0001). Significant associations to NPOU were also observed in the following patient-level covariates: CCI (OR, 1.15; CI, 1.09–1.20), history of tobacco use (OR, 1.79; CI, 1.37–2.36), history of mood disorders (OR, 1.52; CI, 1.23–1.87) and history of pain disorders (OR, 1.49; CI, 1.23–1.82). Additionally, patients in the Western region of the country exhibited the highest estimate in association to NPOU (OR, 1.96; CI, 1.30–2.95), while those with a Bachelor’s degree or higher had a protective association (OR, 0.70; CI, 0.54–0.90). There was no significant association with the type of procedure performed. Factors associated with NPOU among opioid naive anorectal patients are seen in Table 2. The area under the receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curve for prediction of NPOU was 0.72.

Table 2-.

Multivariable Logistic Regression for New Persistent Opioid Use

| Covariates | Odds Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | ||||

| Postoperative Opioid Fill | 3.92 | 2.92 | 5.27 | <0.0001 |

| Patient Characteristics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.20 | 0.99 | 1.44 | 0.061 |

| Age Category (Ref=65+) | ||||

| 18–34 | 1.16 | 0.83 | 1.63 | 0.383 |

| 35–49 | 0.93 | 0.70 | 1.23 | 0.602 |

| 50–64 | 1.17 | 0.90 | 1.52 | 0.233 |

| Region (Ref=Northeast) | ||||

| Midwest | 1.59 | 1.05 | 2.40 | 0.027 |

| South | 1.85 | 1.26 | 2.73 | 0.002 |

| West | 1.96 | 1.30 | 2.95 | 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.94 | 0.45 | 8.39 | 0.377 |

| Education (Ref=Less than Bachelor degree) | ||||

| Less than 12th grade | 1.80 | 0.64 | 5.12 | 0.268 |

| High school diploma | 1.08 | 0.87 | 1.34 | 0.498 |

| Bachelor degree plus | 0.70 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.006 |

| Unknown | 0.54 | 0.23 | 1.25 | 0.150 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 0.49 | 0.26 | 0.93 | 0.030 |

| Black | 1.08 | 0.77 | 1.51 | 0.669 |

| Hispanic | 0.99 | 0.72 | 1.36 | 0.929 |

| Unknown | 0.93 | 0.73 | 1.19 | 0.574 |

| Year of procedure (Ref=2010) | ||||

| 2011 | 1.07 | 0.79 | 1.44 | 0.666 |

| 2012 | 0.99 | 0.73 | 1.35 | 0.954 |

| 2013 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.97 | 0.031 |

| 2014 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 1.23 | 0.424 |

| 2015 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 1.26 | 0.544 |

| 2016 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0.070 |

| 2017 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.73 | 0.002 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| Procedure Type (Ref=Hemorrhoid) | ||||

| Fissure | 0.96 | 0.77 | 1.20 | 0.729 |

| Fistula | 1.09 | 0.76 | 1.56 | 0.615 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| CCI (Charlson Comorbidity Index) | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.20 | <0.0001 |

| Tobacco Use | 1.79 | 1.37 | 2.36 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol or Substance Disorder | 1.33 | 0.83 | 2.14 | 0.247 |

| Mental Health | ||||

| Disruptive Disorder | 1.18 | 0.65 | 2.16 | 0.582 |

| Mood Disorder | 1.52 | 1.23 | 1.87 | 0.000 |

| Other Mental Disorder | 1.52 | 1.02 | 2.27 | 0.041 |

| Pain | ||||

| Pain (Arthritis, Back, Neck) | 1.49 | 1.23 | 1.82 | <0.0001 |

Discussion

In this study, we found high rates of opioid prescribing in the perioperative period in anorectal procedures, with small decreases over time despite the increasing national awareness on the dangers of opioids. Rates of NPOU were over 2% after these procedures thought of as “low risk” (Figure 2). Variables associated with NPOU identified perioperative opioid fills as the strongest independent factor, associated with a nearly 4 times higher odds of NPOU. There was no significant association between NPOU and the type of anorectal procedure performed. With the spiraling opioid epidemic, knowledge that elective surgery serves as a common gateway to persistent opioid use has presented a challenging problem for providers to balance the competing interests of managing acute postoperative pain and minimize the risks of persistent opioid use after the surgery24. Ambulatory anorectal surgery cases are rarely considered in the context of the problem, despite being commonly performed and often including postoperative opioid prescriptions13–19. Study on the trends and contribution of opioids in ambulatory anorectal procedures to NPOU should be determined, as they could impact a large number of patients and opioid prescribing policies.

The results of this work highlight the contribution and risks of NPOU from opioids after ambulatory anorectal surgery. There is little work to date on anorectal cases for comparison. Moreover, there are no evidence-based opioid prescribing guidelines for hemorrhoidectomy, fistula, or fissure patients. Most studies have concentrated on major inpatient procedures, and their results may not be translatable to anorectal procedures for surgeons and policymakers22, 23, 25–27. The large-scale work by Alam et al. on opioid prescribing after short-stay surgery did not include any anorectal procedures21. In the comprehensive work comparing opioid prescribing patterns and NPOU in 29,068 major and minor surgery cases by Brummett at al., hemorrhoidectomy was the only relevant minor procedure included, and its contribution from this procedure to the sample size is unknown14. Thus, the present study focused on ambulatory anorectal procedure to determine the trends in opioid prescribing to develop guidelines is necessary.

The current study is a unique contribution by concentrating on opioid prescribing trends and NPOU after common ambulatory anorectal cases on a national scale. We found opioids were commonly prescribed, between 66–72%, with rates differing across the 3 common procedures. Though the rate of postoperative opioid fills and median OME used decreased annually, there was a considerable risk of NPOU in patients that were opioid-naïve before anorectal surgery. Our prescribing rates were lower than the pervasive and the widely variable amount described by Swarup et al. in a single institution review of 42 outpatient anorectal surgery patients, where 90% were prescribed opioids in volumes up to 120 pills13. However, 80% of pills prescribed were not used; the median number of pills taken was four, with 1 of 42 patients requiring an opioid refill. Adequate pain control was reported in 60% of patients with this amount. While the study was limited by the small sample size, lack of generalizability, and lack of validated scales for postoperative outcomes, the need for standards and ability to achieve adequate pain control with minimal opioids was demonstrated. On a larger scale, Lu et al. retrospectively reviewed 6,294 hemorrhoidectomy patients aged 18–64 from a military claims database, confirming the commonness of opioids after an anorectal procedure28. In their study, 88% filled an initial opioid prescription, and nearly a third received an opioid refill within 2 weeks of the first prescription28. Similar to our findings, characteristics that impacted the likelihood of an opioid refill after hemorrhoidectomy included a history of substance abuse (OR, 3.26; 95% CI,1.37–7.34) and a longer length of index opioid prescription or more opioids provided.

From this work, several previously published findings with regard to opioid prescribing and NPOU in minor and major surgery align with our new findings in ambulatory anorectal surgery. First, opioids are highly prescribed after all surgery, and with wide variability. Our prescribing rates of 66–72% were substantial and comparable to prior works in which postoperative opioid prescribing was often several times more than what was needed or taken by patients13, 13–20, 29–32. Second, NPOU is a risk for all patient populations and procedures. The risk has been previously described between 5 and 10% in minor and major surgery14, 20–23. This work highlights the risk in common ambulatory anorectal cases, and the risk in other populations unlikely to be considered has also been shown, including elderly, oncology, pregnant, and pediatric patients11, 14, 19, 33, 34. Third, certain patient characteristics associated with new persistent use seem universal across both major and minor abdominal and anorectal surgery, including a greater number of comorbidities, preexisting pain conditions, substance abuse, and mental health disorders14, 28, 35. Fourth, filling a perioperative opioid prescription had the strongest association with persistent use. Fortunately, prescribing is a potentially modifiable risk factor. Up to a third of anorectal surgery patients in this study filled no opioid prescriptions after surgery, and published work demonstrates opioid prescribing can be dramatically reduced and even eliminated while maintaining patient-reported pain control13, 36. Thus, opioid-sparing pain control after surgery with a focus on avoiding unnecessary perioperative opioid prescriptions is feasible. This is particularly important as prior work has described the phenomena in which patients prescribed a longer duration of opioids took more opioids and patients who filled larger prescription quantities were more likely to develop NPOU14, 21, 37–39. Persistent use may be for reasons other than pain in ambulatory anorectal surgery, where the pain experienced would be expected to be less than after major surgeries14, also highlighting the importance of reducing perioperative opioid prescriptions.

With these tenets established, important clinical implications can come from this work. Risk factors for persistent use may be more prevalent than surgeons think in anorectal surgery. Preoperative patient screening for NPOU high-risk characteristics and counseling on the dangers of opioids and alternatives should be extended to ambulatory anorectal surgery. In addition, opioid sparing pain management and prudent prescribing should be practiced to reduce the number of unnecessary opioids given and the risk of diversion and NPOU. The effectiveness and acceptability of these practices has been demonstrated after minor surgical procedures, and can be extended to common anorectal cases40. Finally, with the rates and risks established, policymakers can work to create standards for prescribing after ambulatory anorectal surgery, and potentially have a great impact on the opioid epidemic from these frequent cases.

We recognize the limitations in this work. The data source is an administrative claims database, where there could be entry and coding errors, and provides limited demographic variables limits. Thus, we could not consider more granular details or other variables which could impact persistent use and outcomes, such as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) application, ERAS compliance, and intraoperative medication. However, the large sample size here permits drawing importance inferences for representative national prescribing and trends. The cohort was drawn from a large, population-based group of privately insured adults and their dependents, so our findings may not be generalizable to the uninsured or underinsured. Further, we did not capture opioids prescribed nor actual opioid consumption, but assumed opioid prescription fills were a valid estimate of opioid prescribing and use. Prospective data are needed to investigate the patient-level factors associated with NPOU. Despite any limitations, this work provides valuable insight on prescribing trends for opioids after ambulatory anorectal surgery, and their contribution to the opioid epidemic.

Conclusions

From a national claims-based analysis, opioid prescribing after ambulatory anorectal procedures is widespread, with variations in duration. While there were small reductions in opioid prescriptions annually over the study period, there has been little change in the amount prescribed. New persistent opioid use was over 2% in all for these procedures traditionally thought of as “low risk,” and significantly higher for patients that filled perioperative opioid prescriptions. As perioperative prescribing is an actionable finding, this demonstrates a need for surgeons to recognize the impact of the opioids prescribed, both in rate and dose, and eliminate unnecessary prescribing in ambulatory anorectal surgery. These findings should be considered when developing and disseminating best practices for pain management after ambulatory anorectal surgery.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures:

BCK, JFW and CMB were supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH RO1 DA042859) and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS, E20180672-00 Michigan DHHS - MA-2018 Master Agreement Program) as well as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA: E20180568-00 MA-2018 Master Agreement Program). Dr. Brummett is a consultant for Heron Therapeutics (San Diego, CA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, MDHHS, or SAMHSA.

The authors received no funding for this work.

Footnotes

Podium Presentation, The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Annual Conference, June 6–10, 2020, Boston, MA (Cancelled due to COVID-19, presented virtually).

The authors otherwise have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Deborah S Keller, Division of Colorectal Surgery, Department of Surgery; Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Brooke C Kenney, Institute of Healthcare Policy and Innovation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Calista M Harbaugh, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Jennifer F Waljee, Center for Healthcare Outcomes & Policy; Department of Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Chad M Brummett, Institute of Healthcare Policy and Innovation; Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

References:

- 1.Kenan K, Mack K, Paulozzi L. Trends in prescriptions for oxycodone and other commonly used opioids in the United States, 2000–2010. Open Med. 2012;6:e41–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulozzi LJ, Jones CM, Mack KA, et al. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The White House Council of Economic Advisers, Council of Economic Advisers Report: the Underestimated Cost of the Opioid Crisis. Issued November 20, 2017. Available online at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/cea-report-underestimated-cost-opioid-crisis/?utm_source=link, Last accessed May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, Xu L. The Economic Burden of Prescription Opioid Overdose, Abuse, and Dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care. 2016;54:901–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in Prescription Drug Use Among Adults in the United States From 1999–2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1818–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kern DM, Zhou S, Chavoshi S et al. Treatment patterns, healthcare utilization, and costs of chronic opioid treatment for non-cancer pain in the United States. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e222–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JS, Vu JV, Edelman AL et al. Health Care Spending and New Persistent Opioid Use After Surgery. Ann Surg. 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santosa KB, Hu HM, Brummett CM et al. New persistent opioid use among older patients following surgery: A Medicare claims analysis. Surgery. 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall MJ, Schwartzman A, Zhang J, Liu X. Ambulatory Surgery Data From Hospitals and Ambulatory Surgery Centers: United States, 2010. Natl Health Stat Report. 20171–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swarup A, Mathis KA, Hill MV, Ivatury SJ. Patterns of opioid use and prescribing for outpatient anorectal operations. J Surg Res. 2018;229:283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J et al. New Persistent Opioid Use After Minor and Major Surgical Procedures in US Adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose KR, Christie BM, Block LM, Rao VK, Michelotti BF. Opioid Prescribing and Consumption Patterns following Outpatient Plastic Surgery Procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, Finnerty E. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, Bishoff J. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. J Urol. 2011;185:551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris K, Curtis J, Larsen B et al. Opioid pain medication use after dermatologic surgery: a prospective observational study of 212 dermatologic surgery patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harbaugh CM, Lee JS, Hu HM et al. Persistent Opioid Use Among Pediatric Patients After Surgery. Pediatrics. 2018;141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaveri S, Nobel TB, Khetan P, Divino CM. Risk of Chronic Opioid Use in Opioid-Naïve and Non-Naïve Patients after Ambulatory Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll I, Barelka P, Wang CK et al. A pilot cohort study of the determinants of longitudinal opioid use after surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1286–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hah JM, Bateman BT, Ratliff J, Curtin C, Sun E. Chronic Opioid Use After Surgery: Implications for Perioperative Management in the Face of the Opioid Epidemic. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1733–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera DN. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu CL, King AB, Geiger TM et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Perioperative Opioid Minimization in Opioid-Naïve Patients. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:567–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scully RE, Schoenfeld AJ, Jiang W et al. Defining Optimal Length of Opioid Pain Medication Prescription After Common Surgical Procedures. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu P, Fields AC, Andriotti T et al. Opioid Prescriptions After Hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wunsch H, Wijeysundera DN, Passarella MA, Neuman MD. Opioids Prescribed After Low-Risk Surgical Procedures in the United States, 2004–2012. JAMA. 2016;315:1654–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urman RD, Seger DL, Fiskio JM et al. The Burden of Opioid-Related Adverse Drug Events on Hospitalized Previously Opioid-Free Surgical Patients. J Patient Saf. 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thiels CA, Anderson SS, Ubl DS et al. Wide Variation and Overprescription of Opioids After Elective Surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;266:564–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larach DB, Waljee JF, Hu HM et al. Patterns of Initial Opioid Prescribing to Opioid-Naive Patients. Ann Surg. 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peahl AF, Morgan DM, Dalton VK et al. New persistent opioid use after acute opioid prescribing in pregnancy: a nationwide analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JS, Hu HM, Edelman AL et al. New Persistent Opioid Use Among Patients With Cancer After Curative-Intent Surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:4042–4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larach DB, Sahara MJ, As-Sanie S et al. Patient Factors Associated with Opioid Consumption in the Month Following Major Surgery. Ann Surg. 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartford LB, Murphy PB, Gray DK et al. The Standardization of Outpatient Procedure (STOP) Narcotics after anorectal surgery: a prospective non-inferiority study to reduce opioid use. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24:563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y, Cuthbert CA, Karim S et al. Associations Between Physician Prescribing Behavior and Persistent Postoperative Opioid Use Among Cancer Patients Undergoing Curative-intent Surgery: A Population-based Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Factors Influencing Long-Term Opioid Use Among Opioid Naive Patients: An Examination of Initial Prescription Characteristics and Pain Etiologies. J Pain. 2017;18:1374–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ladha KS, Neuman MD, Broms G et al. Opioid Prescribing After Surgery in the United States, Canada, and Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1910734.31483475 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hallway A, Vu J, Lee J et al. Patient Satisfaction and Pain Control Using an Opioid-Sparing Postoperative Pathway. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229:316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.