Abstract

The focus of the phenomenological qualitative study was on the lived experiences of U.S. educators who identified as lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB). Life story data regarding stress, coping, and identity were gathered, triangulated, and analyzed from 24 U.S. educators who identified as LGB teachers, mentors, and coaches. Four themes resulted: (a) subscribing to a helping identity, (b) being effective as an educator, (c) experiencing different levels of support, and (d) being out about sexual orientation to different degrees. Recommendations for future research are provided.

Keywords: Educators, LGBT, lived experiences, phenomenology

Introduction

A paucity of research exists on the lived experiences of educators who identify as lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB). A review of the limited extant research identifies a focus on outness and the impact of environment (Downs, 2009; Szalacha, 2003), however, race, ethnicity, and gender have been less studied. This is of concern because educators who are LGB are forced to participate in a balancing act between self and career, yet they may also identify as racial, ethic, and gender minorities (Prock, Berlin, Harold, & Groden, 2019). This dynamic may allow some people to align their identities, without having to compromise themselves; however, for other people, it may not (Harold, Prock, & Groden, 2019). For example, for educators who are LGB and people of color, they may learn to code switch, a linguistic skill to go between more than one language to match the cultural norms of settings (Sadao, 2003). As a result, we conducted this phenomenological qualitative research study to explore themes in such narratives with a robust national U.S sample of LGB people who shared information about their lived experiences as educators.

There is a dynamic relationship between one’s identity and purpose related to work (Blustein, Kenny, Di Fabio, and Guichard, 2019). When work policies and roles are monolithic, employees’ needs are often not met (e.g. unequal pay) (Blustein et al., 2019). Sexual minority educator identity, like other types of identity, is created through discourse and other forms of communication (semiotics) where the self is located (Lasky, 2005). For educators who identify as LGB, navigating the complex nature of one’s own unique identity and additional work identity leads to attempts to balance personal and professional selves in congruent and incongruent ways (Jones, Gray, & Harris, 2014). Heterosexist attitudes compound this dynamic; students may judge the educators harshly, and even subconsciously (Gates, 2011). “Attitudes [toward LGB people] have ranged from tolerance to oppression, with hostility and condemnation being the norm in Western societies” (Downs, 2009, p. 18).

Educators who are LGB possess multiple identities, so they are susceptible to experiencing the compounding effects of minority stress (Meyer, 2003). Stereotypes often set them apart and they are excluded in the education profession, in the LGBTQ community, and in their own racial and ethnic communities (McConnell, Janulis, Phillips, Truong, & Birkett, 2018; Moradi et al., 2010). In the current study, 62% of the sample identified as people of color (POC). Prior research findings have also shown that a significant part of LGBTQ identity involves the negotiation of multiple identities within one’s self, leading to stress and conflict (Meyer & Ouellette, 2009). This may lead to concealment of one’s authentic identity, an increase of prejudice and discrimination, and lack of LGB role models throughout life (Sutter & Perrin, 2016). Consequently, this paper first provides a review of the literature on sexual minority educator identity, and second, considers the retrospective meaning of the lived experiences of educators who identify as LGB.

Sexual minority educator identity

Although some individuals who are sexual minorities share with others about their minority sexual orientation (i.e. come out) and experience positive effects (Weston, 2014), others come out and experience negative effects. Whipple (2018) interviewed two high school math teachers who identify as gay. They reported that a group of students tore down their safe zone poster in their absence. Additionally, the teachers shared the following:

It is easier for some teachers to be out about their minority sexual orientation because of the characteristics of their school.

Some educators may lead with one identity over another depending on where and with whom they work.

Disclosure of sexual orientation can make a school more inclusive.

Math teacher identity was related to the development of new curricula.

Classroom spaces were reflective of the educator’s passion to teach.

The teachers promoted collaboration as a way for students to get to know each other.

Woods (2012) interviewed 12 physical education teachers who identified as lesbian. These teachers were often harassed, and they struggled with coming out to others. The latter occurred because they believed that coming out would either result in receiving more support or less support (e.g. job loss). As a result, all of the teachers kept their personal and professional identities separate. However, this came with a cost. Concealment taxed their psychological resources (Woods, 2012). Similar findings were discovered by Downs (2009) who interviewed eight female and four male school counselors who identified as LGB about coming out at work. They recommended that more supervisors support individuals who are sexual minorities.

To discern how their experiences informed their teaching, Jackson (2007) interviewed nine teachers who either identified as gay or lesbian. Each participant was interviewed three to four times. Data gathered from them informed development of a six-stage theory to explain how sexual minority identity informed pedagogy. The theory postulated that teachers who identified as LGB integrated their sexual and teaching identities, which resulted in either using teacher-centered or student-centered classroom practices. The six stages of teaching included (1) a pre-teaching stage in which participants spoke about life before and after holding a teaching position, (2) a closeted-teaching stage during which teacher participants taught but were not out, (3) a super-teacher stage in which teachers did not promote a same-sex agenda, (4) an on-the-verge stage during which teachers tried to come out but could not, (5) a post-coming out stage when teachers were out to others, and (6) an authentic-teacher stage when teachers integrated sexual and gender minority topics into classroom curricula.

To learn about politics and power in education, Auciello (2016) interviewed eight administrators: five men who identified as gay and three women who identified as lesbian. Five themes resulted. The administrators (1) experienced fear; (2) wanted to help others; (3) were sensitive to diversity; (4) were resilient and had integrity; and (5) realized that administrators, students, and staff members benefited from respecting each other. Subthemes derived from the five main themes were identified as well. Specifically, the administrators (1) had the desire to pursue leadership positions but were challenged by heterosexuals; (2) set priorities reflective of the degree to which they were out to others; and (3) came out or not to others based on school politics, the race and ethnicity of others in the school, administrator and staff support, and the degree to which school stakeholders displayed gender non-conforming behaviors.

The experiences of educational leaders who identify as sexual minorities were also the focus of a dissertation study by Denton (2009). Most educational leaders shared that they were afraid of not being accepted from a young age. They, however, learned to cope by using silence and working harder to overcompensate for perceived flaws. As a result, they developed a greater sense of self and the ability to show compassion to others who were also marginalized like themselves. Developing safe spaces for everyone, helping the voiceless, and becoming role models became goals. Some participants reported feeling inferior. As a result, they presented to others cautiously and sought out ways to validate their primary relationships. Most importantly, they did not compartmentalize their identities; the educational leaders integrated their identities despite being concerned about job security, a concern that subsided over time. All leaders reported facing discrimination in the absence of federal and state protections. They believed more policies and laws were needed to protect those who were sexual minorities like themselves. In addition, they thought that those who worked in educator preparation and staff development to promote the values of inclusion and respect.

Ferfolja (2007) interviewed 17 teachers who identified as lesbian. Feminist post structural theory was applied to the process of coding data about power differences. The study identified four themes: (1) teachers protected themselves by keeping some aspects of their lives private; (2) teachers were viewed as heterosexual if they worked in a conservative school and were divorced or separated; (3) teachers were viewed as asexual if they were mothers committed to their children; and (4) teachers were seen by others as having sexual identities and ages that were related to each other. For example, younger teachers who identified as lesbian were not viewed by others as lesbian because the younger teachers were also perceived as still having plenty of time in life to find and court opposite sex partners. All themes in Ferfolja’s (2007) study appeared to relate to the overarching idea that “the possibility of the teacher being a lesbian was perceived as far removed from the thought of colleagues” (Ferfolja, 2007, p. 582).

Method

This phenomenological qualitative study contributed to an emerging research area to study the meaning of the life stories tied to educator identity among sexual minorities who identified as LGB. The research method was selected based upon an appreciation of those methods which would produce the data that would best address the research question (Frost, 2019). Authors of this study explored the retrospective life stories to provide an in depth understanding of specific phenomena and processes. The overarching research question was “What themes have been attached to the lived experiences of U.S educators who identify as LGB?” Data were collected from three cohorts of U.S. LGB adults who were paid 75 dollars to participate in individual interviews. The interview sample was comprised of coaches, mentors, and teachers who were from one of three age cohorts; (a) a Post Stonewall Pride cohort (ages 57–64 in 2020), (b) an HIV/AIDS epidemic cohort (ages 39–46 in 2020), and (c) a same-sex marriage cohort (ages 23–30 in 2020). Age cohorts were determined prior to data collection with the assumption that people in each of these cohorts would have a unique vantage point from which to interpret and share about their life experiences since they had come of age at different time periods during youth and adolescence.

Sampling

We analyzed data from 191 participants representing three generations of LGB people in the United States (U.S.) as part of the Generations Study (www.generations-study.com) (Frost et al., 2019). Participants were recruited within 80 miles of Austin, Texas; Tucson, Arizona; New York City, New York; and San Francisco, California. These cities were selected for regional diversity as well as proximity to research team members. The participants were required to have minimally achieved a sixth-grade education and had to be U. S. residents when they were between six and 13 years old. Recruitment focused on LGB people, yet participants in the study were asked to describe their sexual identities, revealing diversity with respect to both sexual and gender identities. The sample included people from diverse racial/ethnic groups, including African American, Asian American, European American, Latinx, Native American, or Multiracial.

Interview protocols

Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire. Participants were interviewed face-to-face for two to three hours. The interview protocol was developed to focus on lifetime identity stress and was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. After the participants signed a consent form, they answered questions about stress, coping, social history, and their career experiences. As a result, the data yielded important insights into this topic because data analyzed were garnered from the responses of 24 participants who talked specifically about their experiences as educators. Data were compared as part of data analysis procedures (Creswell, 2002; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Additionally, descriptive and reflective field notes were collected to record (1) conversations before and after audio-recording; (2) actions of the interviewee; and (3) ideas, questions, and concerns of interviewers. Interviewers used the questionnaire to collect certain information, and they were free to explore other topics (e.g. why one decided to become an educator). All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Research team

Graduate and post-doctoral students interviewed participants along with the lead author who also coded and analyzed data along with the remaining authors. All members of the research team expected to identify salient themes in the data central to the lived experiences of participants who identified as LGB educators. We hypothesized that level of outness would have varied among participants and that educators who identified as LGB would have become educators themselves in order to serve as role models that they lacked during the school-age years. The lead author for this team is a counselor educator and researcher who is a 42-year-old European American, cisgender, gay male. He is interested in counseling youth and adolescents, LGBTQI school and career topics, mixed research, motivation, and the experiences of minorities in STEM. His age is representative of the ages of those in the middle cohort in this study. He grew up in the rural Midwest and did not have access to LGBTQI resources. The second author is a European American, heterosexual, cisgender female with a PhD in gerontology. She is an Educational Ambassador for SAGE, a national service and advocacy organization for LGBT elders. She views herself as a heterosexual ally and stands up to biphobia, homophobia, and transphobia. As a qualitative researcher whose scholarship has focused on the experiences of LGBT elders, she coded and analyzed data as part of this project. The first and second authors are Assistant Professors at a private college in the Northeast. The third author identifies as a Cherokee, gay, cisgender male. He is Professor Emeritus at a research-intensive university in the Midwest. His age is about the ages of participants in the older cohort. He was raised in poverty in the rural Midwest and served as a consultant and editor regarding participants’ voices, including Native American voices, in this paper. The fourth author is a European American, gay, cisgender male. He is a senior faculty member at a research-intensive university in the South. His age is between the ages of participants in the middle and older cohorts. He was raised in the rural South and experienced silence in relationship to secondary school-level LGBTQ issues.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the Constant Comparative method which is a thematic approach this is compatible with phenomenology (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Data were gathered, transcribed, and coded (based on agreement) after receiving data from the first participant to identify topics throughout the interview process. Codes were assigned to new data, which allowed team members to compare data throughout the data analysis process. As more data were gathered, compared, and coded, themes began to emerge from the codes. New data were differentiated or dedifferentiated from data collected and analyzed earlier. Straightforward codes were grouped into themes. Next, we identified notable patterns in the form of multiple unique views disclosed by participants regarding their experiences (Onwuegbuzie & Johnson, 2006). All team members identified main ideas in each transcript which they shared with each other. Transcript data were summarized as succinctly and clearly as possible. When research team members could not agree, transcripts were re-reviewed.

After the team reviewed the original, larger Generations Study data set, including a discussion of the research questions and initial findings, researchers re-read interviews separately. During this time, phrases, words, patterns, omissions, and commonalities were searched for to create larger themes (Patton, 1990; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Variables of interest were race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, school levels and settings, career milestones, level of outness, number of role models, and advocacy training. Auditor feedback was provided and reviewed by the research team until consensus was met during the process of coding transcripts, developing main ideas, and cross analysis (Hill, 2012). Additionally, findings were analyzed to inform future research.

Coding transcripts involved coding data related to interview protocol question items. For example, a question about the impact of being harassed during youth might have been “How did one’s age impact one’s decision to become a teacher?” Themes could have comprised one or more codes. Preliminary themes were the first themes identified by research team members. Transcript data were coded and placed into themes. Examples of the data were short and long phrases shared by participants. Each member of the research team shared openly with each other to minimize power differences considering the Feminist post-structural frame applied in Ferfolja’s (2007) study. Each transcript was coded using the same themes unless the theme list changed stemming from the inclusion of new data and transcript codes. If this outcome resulted, transcripts coded earlier during the data analysis process were re-coded using the new list of codes.

Results and discussion

The experiences of educators who identify as LGB were explored in this study. Specifically, the purpose was to develop a better understanding of the meaning of their lived experiences which, as found in earlier studies, was often tied coming out or not to others about their sexual orientation. We hope that our findings will inform the work of researchers, employers, and helping professionals, including counselors, so that they may better meet the needs of people who identify as LGB, including those who also identify as racial, ethic, and gender minorities. We will now discuss our findings in more detail. First, demographic information about participants is shared. Second, we address the desire of participants to help others and then discuss intersectionality. Third, participants’ views about being effective as educators are reviewed. Fourth, level of support by parents and friends is reviewed. Fifth, outness is reviewed and followed by discussion. Last, study limitations and research recommendations are provided.

Study participants

Themes and participants’ narratives follow. Of the 24 educators who identified as LGB who were interviewed, those who identified as gay and lesbian and reached adulthood during the Stonewall Rebellion shared more about choosing to become educators than individuals who identified as LGB who reached adulthood during the HIV/AIDS Generation and during the legalization of same-gender marriage in the U.S. Across all three Generations Study cohorts, males who identified as Black who also most commonly identified as bisexual, and males and females who identified as Native American who also most commonly identified as Two-Spirit, shared the most in comparison to all other participants about why they became educators. The classes that the educator participants most commonly taught were drama, physical education, and photography. Each of the study participants were from one of three cohorts: (a) seven (29%) grew up during the Stonewall Rebellion, (b) 13 (54%) grew up during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and (c) four (17%) grew up during the passage of same-sex marriage law. Of the 24 participants, nine (38%) were European American and 15 (62%) were POC. Of the remaining 15, two (8%) were Asian Pacific Islander, two (8%) were Native American, four (17%) were African American, six (25%) were Latino/a/x, and one (4%) was Multiracial.

Ages of participants ranged from 21 to 58, with an average age of 40. Ten (42%) were female, 11 (46%) were male, and three (12%) were genderqueer. Two (8%) were bisexual, three (12%) were lesbian, 10 (42%) were gay, two (8%) were pansexual, and seven (30%) were queer. Two (8%) received high school diplomas, two (8%) received associate degrees, two (8%) received bachelor’s degrees, five (22%) received college degrees, and eleven (46%) fully completed graduate education. Two (8%) pursued some level of graduate education. Ten (42%) participants did not have children, but 4 (17%) did. Six (25%) participants were single, and eight (33%) were partnered. Twenty-two (92%) participants reported living in a metro area of 1 million people or more. One (4%) participant, a male who identified as Latino and gay, lived in a nonmetro area with 20,000 or more people in the vicinity of a metro area. One (4%) participant, a male who identified as Native American and gay, lived in a nonmetro area with 2,500 people or less not in the vicinity of a metro area.

Helping identity

When analyzing the data, we found that the participants reached a point in life when they were helping and serving others. Second to the theme of level of outness to others, this theme was the most identified among the data gathered from the 24 educators. For Evan, a male who identified as Black and gay, this realization was the highest point in his life. He shared, “It’s when I got this job [at] this not for profit organization that teaches arts through education. (….) I have finally figured out what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. That was teaching.” Others found themselves gravitating toward the teaching profession when they were younger. Jerry, a male who identified as Native American and gay, was a coach, mentor, and community leader during adolescence. When he was a child, he had felt alienated because of being bullied and experiencing prejudice. Consequently, helping others made him feel better. A participant who identified as Latino, genderqueer, and pansexual shared:

I remember being in first grade and already tutoring people that were at a lower-level reading or math. (….) I was already being paid at the same rate as other teachers’ assistants that were in college and stuff like that, because I was so good. I was awesome at my teaching. I love teaching. I love teaching.

Jesus, a male who identified as Latino and gay, shared:

I am now working as a life coach in my life so that’s an aspect that—a new identity that is coming out of others that I feel like really matches like I can best serve people. I work as a nanny right now for a family on the Upper Eastside so there is that. Being a caregiver. (….) I am a big helper in people’s lives and my life.

Vicky, who identified as Latina and bisexual, disclosed:

I can talk to someone who is in junior high and struggling with this. Two of my nephews and my nieces. Talk to them. “Hey. It’s okay! It’s okay. Let’s talk about sex. Let’s talk about sexuality. Let’s talk about safe sex.” That motivates me, and that pushes me. I don’t struggle because now I know how I feel, what I feel, what my sexuality looks like, and I am comfortable. I wish I could say the same for a lot of other people.

Effectiveness as an educator

Participants spoke about the importance of becoming effective educators. They believed that this would occur when they (1) had others who were present in their lives who cared about them, (2) learned to persevere by cognitively coping (i.e. they did not care what others thought about them), (3) identified different pedagogical approaches to teach others, and (4) decided to become role models for others. Marco, who identified as Latino and gay, shared:

To be a successful educator, I think, requires an openness to people, regardless of ethnicity, regardless of socioeconomic level, regardless of sexual orientation. One of the things that I see myself as, more than anything else, is a helper to others. If I can help you with whatever the situation—clean up your streets, teach you how to compost, teach you how to diagram a sentence, teach you how to landscape, whatever the case—then I’m succeeding. Success, I think, comes from not money, not title, but from how much you have helped others. I think, to be exclusionary would be contrary to that. I really try to stay open to everyone.

Johnny, who identified as Black and gay, disclosed:

I worked at the Lake University from “91 to 97.” [It was] run by a congregation of sisters. They always had a (…) healthy percentage of gay students. Now, the funny thing is that while they never spoke about it, it was always about trying to figure out how we can nurture—I remember having a conversation with the president at the time when the gay students (…) were trying to get recognition. She calls me into her office and goes, “I know you’re advising this group, but you should just know we’re not gonna be able to recognize them, because the church won’t. The archdiocese won’t let us recognize ‘em. I want you to support these young people. (….) Let them know that I support them.” I said, “Well, sister, they’d be much happier to hear that from you. If this is how you want me to move, I am happy to do that. (….) We would funnel things through our center for women that were programs to support our gay and lesbian students on our camps, because no one would question the director of the center for women.” “This is the center for women! This is what we have to do!” The nuns was [sic] like, “Oh yes, we have to support the women,” kind of thing. [Chuckles]

Vicky said:

I am part of an organization that focuses on social and educational events for LGBTQA Latinos, Hispanics, and Mexicans. Being part of that group and doing outreach really helps. Where I work, that helps to educate others about the bigger picture. Now that I see things in the bigger scale, when we are talking about intersectional biases, sexism, and racism, it is all connected.

Dan, who identified as White and gay, shared, “In teaching, I wanna make sure that the gay students, the queer students, feel the same pride in themselves and feel equally validated in their experience so that they can use that in their art.” Additionally, Jenny, a female art educator who identified as White and lesbian, said:

I do a lot of exploring in all kinds of ways that a lot of people might not, that aren’t—that don’t feel as free to, or liberated to. I have used my art to heal myself. I have used my art to heal others, meaning, creating my own art to put out there for others. I also used art to help others heal by teaching them how to do art, and how to express whatever they need to, to emote, so it becomes a cathartic experience for them. That is the teacher part of me. Those two are intertwined.

Jesus shared about trying to effectively motivate all students to reach their full potential:

“Enthusiastic” is probably one of the pinnacle aspects of who I am and how I naturally feel when I meet people. I feel like I meet people in their full potential, and I see their full potential. I think everyone is genuinely unique and special. “Gay,” “Puerto Rican,” “Successful go-getter,” and “a learner.” I am always up for learning.

Jerry added:

I’m vocal. I’m my worst critic. I’m hard-headed. Perfectionist. When it comes to cheerleading, (…) I’ve coached [at] junior colleges. I’ve coached high school teams. I coached an all-star team. Then I came to elementary school, [and] they were like, “Can you help?” I am like “Sure, I’ll help you. I’m on it.” On them. Making this fourth grader lift this one girl by himself. “Push up! Push it. You can push it!”

Having high expectations of his students was related to Jerry’s personhood as a Native American (intersectionality). Although he struggled growing up as Native American on the reservation because he identified as gay, he was able to connect more effectively with his students who were treated differently. Jerry was committed to providing them with a safe environment.

Levels of support

Throughout their lives, participants received varying levels of support from parents and friends. Jerry’s mother helped him to develop mentorship skills. From a young age, other people naturally sought him out for help. As such, his mother expected him to mentor them. She also showed him love even though she did not accept him. This dynamic was present among Jerry’s friends as well. Whereas on one hand they supported him, on the other hand they did not. For example, they verbally bullied him (Simons, Ramdas, & Russell, 2020). To cope Jerry utilized cognitive reframing; Jerry made up excuses in his mind for why his friends did not support him. Sadly, however, before he learned how to cope in this way, he contemplated suicide, abused drugs, and had many sex partners.

Evan had limited peer support during high school. As a result, he gave up on himself once he started college. He stated, “If I [would have had support], maybe I would not have given up so easily.” However, his experience with lack of support during adolescence contributed to his decision to become an educator, a decision that he made when was enrolled in an internship course:

It took me sitting in that [internship] class and watching my boss and a teaching artist teaching these kids and be like, “I want to do this.” Me sitting with them after all the kids leave, and I am listening to them talk about their lesson plans for the next day and be like, “I want to do this. I want to—I really want to work with kids. I really want to help them understand the world.

Levels of outness

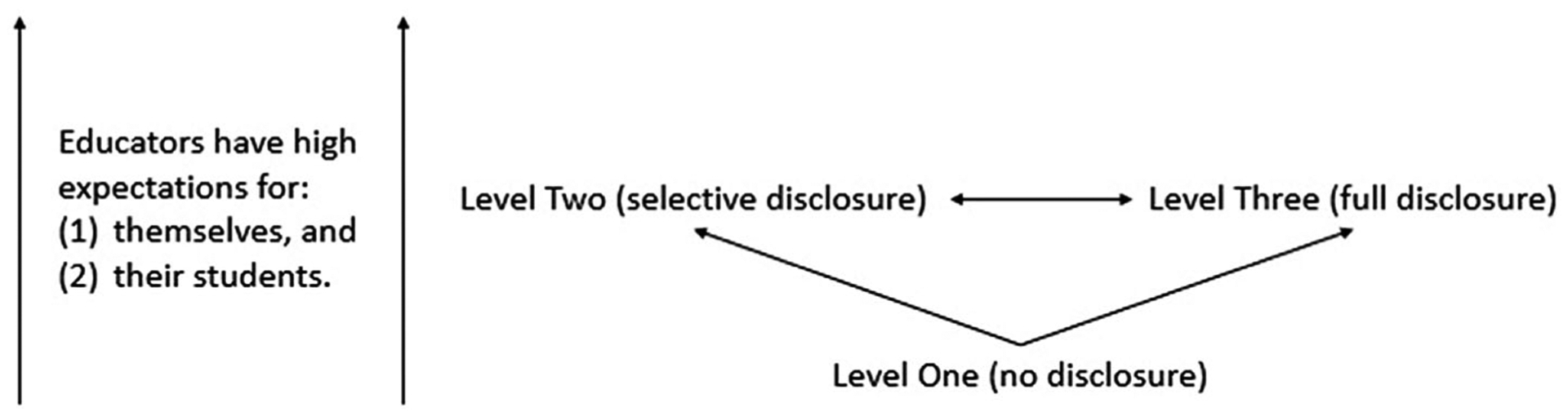

All participants talked about the degree to which they were out and how they described themselves to others at school regarding their sexual orientation. As a result, in this section, a model of sexual minority educator career identity development related to level of outness among educators who have high expectation of themselves and their students is proposed (see Figure 1). The proposed model has three levels. Levels one and two are dynamic (i.e. they are non-linear). Most participants strove to come out, even if they were not, and some did this while incurring a cost or pursuing education. Jerry did not find it easy to identify as gay even though he wanted to be visible. This occurred because he knew that some parents would not want to have their children enrolled in his class if they knew that he identified as gay. Being out, an important part of his identity, therefore, came with a price. Janette, a female who identified as Native American and pansexual, said:

I hope to get my bachelor’s degree by the end of next year. Then [I will] start teaching math at a high school, while I pursue graduate school. Hopefully by the time I turn 30, I [will] have my PhD in math and can be a college professor.

Figure 1.

Model of sexual minority educator career identity development related to level of outness.

As they aged, the participants reported that coming out required having to become more patient and comfortable with their sexual identities. Publicly identifying as LGB has been and is still one of the most challenging tasks for current and future educators to enact (Simons, 2020). However, once they came out, they inspired others to do the same. In another study conducted by Simons and Russell (in press) with the Generations Study dataset, at least one participant in each of the three Generations Study age cohorts (younger, middle, and older) was either implicitly or explicitly out with the aim to serve as a role model. Some educators made the decision during early adolescence to be out in adulthood by either selectively disclosing (level two) or fully disclosing about their sexual orientation to others (level three). In one instance, a participant came out as a lesbian later in life because she had been inspired by her male high school photography teacher who identified as gay.

Level one (no disclosure)

At level one, strict division existed between educator participants’ personal and professional lives about being out to others. The participants did not disclose in either sphere even if they wanted to; they remained in the closet indefinitely about their sexuality. Resultingly, their autonomy and wellness were compromised, and, in addition to not disclosing about their minority sexual orientation to others, some foreclosed on a desire to become educators (Marcia, 1966). A more likely scenario though was one in which participants became educators but remained closeted throughout the full length of their careers. Matt talked about a principal who was Catholic:

He is still so afraid of someone finding out that he is gay that he goes to just crazy lengths to try to separate and distance himself from those possibilities. It is very sad to see that. He should be able to live his life.

Level two (selective disclosure)

At level two, participants selectively shared about themselves to others. The participants were out about their minority sexual orientation (or aspects of it), but they did not share this information all the time with everyone. For example, students sometimes would ask the educators personal questions. Some might in turn have shared this information, whereas others might have not. Johnny disclosed, “[A person] had to earn the ability to have that information. (….) I certainly operated under the rule of you do not need to know until I tell you.” Jenny shared:

Right now I teach at an elementary school and it is not information for the kids or the parents. If my colleagues wanted to know or were curious, I have no problem with that. (…) I am part of the Southern Arizona Senior Pride group. I do not have a problem with that [either].

Jenny and several other participants chose to only disclose about their minority sexual orientation if they were directly asked about it (e.g. what is your sexual orientation?), of if certain people asked (e.g. high school versus elementary students). At level two, one’s level of outness to others (e.g. colleagues) also was related to intimacy. Ian, a male who identified as White and gay, disclosed:

Up until last year, I was a classroom teacher and just did not talk about [my sexual orientation]. (….) Now, like with people at work that know, when then it comes up casually, it is not a big deal, but I also feel like, yeah, I could not be close to them without them knowing.

Level three (full disclosure)

At level three, educators recognized the need for social justice, role models, and visibility among individuals who identified as LGB in schools. Sherman, a male who identified as Black and gay, was fully out:

I told all my assistant coaches I am gay. If you have a problem with that, there is the door. A lot of ‘em just didn’t know how to deal with that. A lot of ‘em after seeing me in action and the way I acted asked, “Are you sure you are gay? You don’t act like a gay man!” It was their idea of what a gay man acted like; you know?

Dan said:

To me. It is important to be visible as gay. (…) I find it a small part of my teaching (…) to say “I am gay.” (.…) I am not ashamed of my experience, nor should you be. (….) Embrace it. Use it. Learn from it.

Evan shared:

When I do become a teacher I am going to be out, and I am going to talk about it. I am going to be like, “This is who I am.” I am not going to be afraid to be with kids because I feel more comfortable as an actual teacher instead of a student teacher or an intern working with kids.

Vicky stated:

Anger pushed me to say, “You know what? I don’t care what you think. I don’t care what anything thinks. This is who I am, and there’s a lot more like me. I’m going to speak out against this, and I’m gonna help others.”

Simons et al. (2020) discovered that participants who matured during the legalization of same-gender marriage primarily used cognitive techniques to cope with their decision to be fully out. Johnny said:

If I was going to be expected to attend these functions at my employer, with my employer, beyond the normal workday where my colleagues were bringing their spouses, I was gonna bring my partner, whether people liked it or not. (….) My approach was, it was my job to show even those skeptics potentially in the crowd—there was a priest who was on our staff—is that I could be a professional, a very well-respected professional. (….) For me, it is like, “Okay, you know who you are, where you are. How can you be better?” That has been my thing.

Future research

All themes appeared to hang together on the levels of outness theme. “The notion of coming out” remains complicated (Khayatt & Iskander, 2020, p. 7). This was confirmed by a review of literature using each theme that we discovered in this study as a keyword. The same questions that have been asked in the past are still being asked today with the caveat: in addition to asking about coming out as a teacher who is a sexual minority, more people are asking about what it means to come out as a gender minority. Khayatt and Iskander (2020) found that in some ways it is more challenging for those who identify as gender minorities to come out to students than those who identify as LGB. This seems to relate to a struggle in academia and society at large to answer the following: (1) What is gender? (2) What is sex? (3) What does it mean for one to identify as non-binary? As a result, more research is warranted in this research area.

Roberts, Allan, and Wells (2007) interviewed two teachers, Gayle and Carol, both of whom identified as transgender. They were interviewed about transitioning from one gender to another while working in K-12 education. Gayle shared:

I tried until I was in my mid-fifties to bury my inner female core identity by taking on many extra-curricular activities within my school and, in my free time, keeping myself constantly occupied with such activities as backpacking, canoeing, and wildlife photography. However, the mounting mental anguish (which I later understood to be gender dysphoria) eventually intensified to the point where I could no longer function—even as a successful and highly respected teacher. I knew that I ultimately had to transition for myself and for my peace of mind (as cited in Roberts et al., 2007, p. 121).

Carol shared:

The students and parents showed no sign of seeing anything unusual about my appearance and mannerisms. Sadly, [however,] my principal continued her attempts to have me removed. My desire to continue teaching, however, was stronger than her ability to dissuade me. I developed a personal mantra to fortify my strength and courage to survive. I repeated the phrase, “I will teach in a deep, dank dungeon, next door to hell,” which helped me to survive through some very adverse conditions. (…) Today, I remain teaching as a proud teacher (as cited in Roberts et al., 2007, p. 124).

Second, researchers should begin to study the experiences of transgender males and nonbinary people more and do so separately from the experiences of those who identify as LGB. The experiences of Gayle and Carol illustrate how difficult it is to transition from one gender to another as a teacher. Additionally, most of the research conducted to understand experiences like their experiences has been qualitative and used small sample sizes. Thus, to develop and improve practice recommendations to support colleagues who experience distress related to sex and gender, we encourage researchers to conduct quantitative and mixed research with large sample sizes to study the current and retrospective experiences of educators like Gayle and Carol.

Third, research should be conducted that take geographic considerations into account. In this study, we did not compare data across the four cities. A study, however, like this is warranted given the differences between the cities. Next, because most sexual minority educator research has been conducted in the U.S., Great Britain, and Australia, more research in this area should be conducted using data gathered from elsewhere. This is especially important because educators who come out in Bangladesh, Barbados, Guyana, Sierra Leone, Qatar, Uganda, and Zambia may go to prison for life. In northern Nigeria and southern Somalia, in Syrian and Iraqi ISIS territories, and in Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Iraq, Mauritania, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Yemen, these educators may be put to death (Amnesty International, 2020). Government officials in Nigeria, Uganda, and Russia rarely discuss sexual and gender minority topics with Western representatives.

Last, additional research is needed to examine the differences in experiences between male, female, intersex, transgender, and gender non-conforming educators who work in different schools during different stages of personal and professional development, and with different levels of ability to advocate for minorities. Study in these areas will help researchers refine recommendations for effectively advocating for students who identify as sexual and gender minorities. Measures that have been standardized that may be utilized to study this research area include the School Counselor Sexual Minority Advocacy Competence Scale (SCSMACS; Simons, 2018) and the Measure of Gender Exploration and Commitment (MGEC; Simons & Bahr, 2020).

Limitations

We conducted retrospective life story interviews with a non-probability sample of 24 educators comprising teachers, mentors, and coaches who identified as LGB. The participants were assumed to be experts of the meaning of their own experiences. Some disclosed their sexual orientation to others at work, but others had not. Four themes, including a model of identity development were identified, as well as several future research recommendations. Data were gathered from the cohorts of participants who lived in or within 80 miles of four LGBT/Queer friendly cities. Learning about the experiences of one group of educators in comparison to the experiences of another group of educators was challenging because sociocultural changes over time have different effects on groups of people over time. Next, we explored data gathered from three generational cohorts of participants. As a result, the findings of the study cannot be widely applied to a population of educators. The findings, however, have shed light on the retrospective experiences of educators who identified as LGB.

Conclusion

We believe that all students, including students who are sexual minorities, deserve to learn from courageous leaders who are looked up to by young people who say, “I want to be like them.” We conducted a non-directive phenomenological qualitative research study to learn about the lived experiences of educators who identified as LGB, many of whom were also POC (i.e. 62% of the sample). Our findings confirmed and extended prior research findings. People who are LGB have a long history in education—whether they have been out to others or not. The educators we interviewed had dedicated their lives to education with different levels of support. They seemed to believe that the educator’s role was related to the whole community. Educator preparation often began for them at an early age. They had to learn how to persevere and accept themselves when others did not. This rite of passage prepared for them for their chosen career. Deciding to enter education was core to their identities and an act of courage.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the interviewers and field research workers and recognize the contribution of Heather Cole, Stephanie Farrell, Jessica Fish, Janae Hubbard, Evan Krueger, Quinlyn Morrow, Jose M. Rodas, James Thing, Antonio Cintron, and Erin Toolis.

Funding

Research reported in this article is part of the Generations Study, supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HD078526.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The Generations investigators are: Ilan H. Meyer, Ph.D., (PI), David M. Frost, Ph.D., Phillip L. Hammack, Ph.D., Marguerita Lightfoot, Ph.D., Stephen T. Russell, Ph.D. and Bianca D.M. Wilson, Ph.D. (Co-Investigators, listed alphabetically).

References

- Amnesty International (2020). LGBTI rights. https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/discrimination/lgbt-rights/.

- Auciello MJ (2016). In their own voices: The lived personal and professional experiences of LGB[BT]I school administrators (Doctoral dissertation). Newark, NJ: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein DL, Kenny ME, Di Fabio A, & Guichard J (2019). Expanding the impact of the psychology of working: Engaging psychology in the struggle for decent work and human rights. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(1), 3–28. doi: 10.1177/1069072718774002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J (2002). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Denton MJ (2009). The lived experiences of lesbian/gay/[bisexual/transgender] educational Leaders (Doctoral dissertation). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Downs JL (2009). Lesbian, gay, bisexual school counselors: What influences their decision-making regarding coming out at work (Doctoral dissertation). Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University. [Google Scholar]

- Ferfolja T (2007). Teacher negotiations of sexual subjectivities. Gender and Education, 19(5), 569–586. doi: 10.1080/09540250701535584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Hammack PL, Wilson BDM, Russell ST, Lightfoot M, & Meyer IH (2019). The qualitative interview in psychology and the study of social change: Sexual identity development, minority stress, and health in the Generations Study. Qualitative Psychology, 7(3), 245–266. doi: 10.1037/qup0000148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates G (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? Los Angeles: Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Harold RD, Prock KA, & Groden SR (2019). Academic and personal identity: Connection vs. separation. Journal of Social Work Education, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2019.1670304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE (Ed.). (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JM (2007). Unmasking identities: An exploration of the lives of gay and lesbian teachers. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jones T, Gray E, & Harris A (2014). GLBTIQ teachers in Australian education policy: Protections, suspicions, and restrictions. Sex Education, 14(3), 338–353. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2014.901908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khayatt D, & Iskander L (2020). Reflecting on ‘coming out’ in the classroom. Teaching Education, 31(1), 6–16. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2019.1689943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lasky S (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 899–816. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell EA, Janulis P, Phillips G, Truong R, & Birkett M (2018). Multiple minority stress and LGBT community resilience among sexual minority men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, & Ouellette SC (2009). Unity and purpose at the intersections of racial/ethnic and sexual identities. In Hammack PL & Cohler BJ (Eds.), The story of sexual identity: Narrative perspectives on the gay and lesbian life course (pp. 79–106). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:Oso/9780195326789.003.0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Wiseman MC, DeBlaere C, Goodman MB, Sarkees A, Brewster ME, & Huang Y-P (2010). LGB of color and white individuals’ perceptions of heterosexist stigma, internalized homophobia, and outness: Comparisons of levels and links. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(3), 397–424. doi: 10.1177/0011000009335263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, & Johnson RB (2006). The validity issue in mixed research. Research in the Schools, 13, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Prock KA, Berlin S, Harold RD, & Groden SR (2019). Stories from LGBTQ social work faculty: What is the impact of being “out” in academia? Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 31(2), 182–201. 10.1080/10538720.2019.1584074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G, Allan C, & Wells K (2007). Understanding gender identity in K-12 Schools. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education, 4(4), 119–129. doi: 10.1300/J367v04n04_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadao KC (2003). Living in two worlds: Success and the bicultural faculty of color. The Review of Higher Education, 26 (4), 397–418. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2003.0034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JD (2018). School Counselor Sexual Minority Advocacy Competence Scale (SCSMACS): Development, validity, and reliability. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1–4. doi: 10.1177/2156759X18761900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JD (2020). From identity to enaction: Identity behavior theory. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Simons JD, & Bahr MW (2020). The Measure of Gender Exploration and Commitment: Gender identity development, student wellness, and the role of the school counselor. Journal of School Counseling, 18(9), 1–34. Retrieved from http://www.jsc.montana.edu/articles/v18n9.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Simons JD, Ramdas M, & Russell ST (2020). School-age coping: Themes across three generations of sexual minorities. Journal of School Counseling, 18(22), 1–28. Retrieved from http:/www.jsc.montana.edu/articles/v18n22.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JD, & Russell ST (in press). Educator interaction with sexual minority students. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin J (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin J (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter M, & Perrin PB (2016). Discrimination, mental health, and suicidal ideation among LGBTQ people of color. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 98–105. doi: 10.1037/cou0000126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha L (2003). Safer sexual diversity climate: Lessons learnt from an evaluation of Massachusetts safe school programs for gay and lesbian students. American Journal of Education, 110(1), 58–88. doi: 10.1086/377673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Testa RJ, Habarth J, Peta J, Balsam K, & Bockting W (2015). Development of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weston D (2014, October 17). One simple act can be a global inspiration. The Times Educational Supplement, 5117, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Woods SE (2012). Describing the experience of lesbian physical educators: A phenomenological study. In Sparkes AC (Ed.), Research in Physical Education and Sport (pp. 90–117. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Whipple KS (2018). LGBTQ Secondary Mathematics Educators: Their Identities and Their Classrooms (Doctoral dissertation). St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]