Abstract

Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is the major pathway of Ca2+ entry in mammalian cells, and regulates a variety of cellular functions including proliferation, motility, apoptosis, and death. Accumulating evidence has indicated that augmented SOCE is related to the generation and development of cancer, including tumor formation, proliferation, angiogenesis, metastasis, and antitumor immunity. Therefore, the development of compounds targeting SOCE has been proposed as a potential and effective strategy for use in cancer therapy. In this review, we summarize the current research on SOCE inhibitors and blockers, discuss their effects and possible mechanisms of action in cancer therapy, and induce a new perspective on the treatment of cancer.

Keywords: SOCE, cancer, inhibitor, pharmacodynamics, therapy

Introduction

The Overview of Store-Operated Calcium Entry

Store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) is typically activated by ligands of cell surface receptors such as G proteins that activate phospholipase C (PLC) to cleave phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and produce inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate (IP3). IP3 binds to IP3 receptors (IP3R) on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, leading to the release of Ca2+ from the ER. Cells respond to this depletion of ER intraluminal Ca2+ by opening Ca2+ channels to allow cellular influx, which is also the provenance of “SOCE.” Researchers have been exploring the mechanisms and functions of SOCE since its discovery and definition, and it has been found that stromal interaction molecules (STIMs) and ORAI family proteins are the two major participants in SOCE (Hogan et al., 2010; Prakriya and Lewis, 2015).

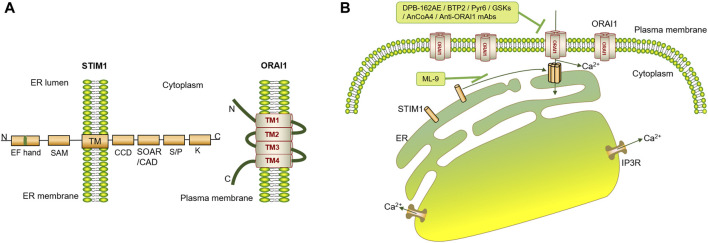

STIM proteins (STIM1 and STIM2) are located on the ER membrane and are essential for SOCE (Williams et al., 2001; Liou et al., 2005; Roos et al., 2005). STIM1 contains an ER-luminal portion (containing two EF-hands and a sterile α-motif (SAM) domain), a single transmembrane segment, and a cytoplasmic portion (containing a coiled-coil domain (CCD), a STIM-ORAI-activating region (SOAR) or CRAC activation domain (CAD), a serine- or proline-rich segments and a polybasic (PB) C-tail) (Hogan et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2016). STIM2 has a structure similar to STIM1 but a critical residue difference in the SOAR domain, which endows STIM2 with partial agonist properties and competitive inhibiting functions in STIM1-mediated Ca2+ entry, thereby maintaining basal cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels by preventing uncontrolled activation of ORAI proteins (Brandman et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2014).

ORAI proteins are plasma membrane (PM) channels that can be gated by STIMs for Ca2+ entry during SOCE. Three homologs of ORAI have been identified in humans, namely, ORAI1, ORAI2, and ORAI3 (also called CRACM1-3), among which, ORAI1 is the most potent and has been extensively studied. ORAI1 contains four transmembrane helices (TM1-TM4), an intracellular location domain (including N-terminal and C-terminal epitope tags) and an extracellular location domain (including an epitope tag introduced into the TM3-TM4 loop). The N-terminus and C-terminus of ORAI1 intracellular sites are essential for the interaction with STIM1 and the opening of the ORAI1 channel (Peinelt et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006; Hogan et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2016). The homologs, ORAI2 and ORAI3 primarily differ in cytosolic N-terminal, C-terminal and 3–4 loop sequences (Amcheslavsky et al., 2015), and they mediate SOCE in a manner similar to that of ORAI1, but they differ in permeability properties and inactivation (Lis et al., 2007), leading to augmented SOCE efficacy in the order ORAI1 > ORAI2 > ORAI3 (Mercer et al., 2006).

When STIM1 residing in the ER lumen senses a Ca2+ decrease in the ER, it initiates conformational changes and oligomerization, overcoming the intracellular autoinhibition mediated by CC1 to expose SOAR/CAD and the PB C-tail. Activated STIM1 multimerizes and migrates toward the PM, where it interacts with the intracellular regions of ORAI1, resulting in ORAI1 activation and Ca2+ influx (Figure 1) (Liou et al., 2005; Park et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2010).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of ORAI1- and STIM1-mediated SOCE. (A) STIM1 contains two EF-hands, a sterile α motif (SAM) domain, a single transmembrane segment, a coiled-coil domain (CCD), a STIM-ORAI activating region (SOAR) or CRAC activation domain (CAD), a serine- or proline-rich segments, and a polybasic (PB) C-tail. ORAI1 contains four transmembrane helices (TM1-TM4), intracellular N-terminal and C-terminal epitope tags, and an extracellular epitope tag that is introduced into the TM3-TM4 loop. (B) IP3R binds to IP3 upon triggering by agonists, leading to the release of Ca2+ from the ER. STIM1 residing in the ER senses the Ca2+ decrease in the ER and initiates conformational changes and oligomerization to expose SOAR/CAD and the PB C-tail. Activated STIM1 further multimerizes and migrates toward the PM, interacts with the intracellular regions of ORAI1, gates and opens ORAI1 directly to enable rapidly uptake of Ca2+. SOCE-targeted inhibitors, such as DPB-162AE, BTP2, Pyr6, GSKs, AnCoA4, Anti-ORAI1 mAbs and so on, are demonstrated to inhibit ORAI1, and ML-9 is confirmed to inhibit STIM1 translocation.

Transient receptor potential proteins (TRPs) contain similar structures, consisting of six transmembrane-helical domains (TM1-TM6) with a loop between TM5 and TM6 and cytoplasmic N- and C-termini (Venkatachalam and Montell, 2007). TRP channels, especially TRPC channels, have been proposed as candidate components of SOCE, although this assignment is still disputed, under certain conditions, several TRPC channels can function in SOCE pathways (Prakriya and Lewis, 2015). For example, in HEK-293 cells, the knockdown of TRPC1, TRPC3 or TRPC7 dramatically reduced the SOCE activated by passive Ca2+ store depletion, while inhibition of TRPC4 or TRPC6 had no effect on SOCs activity (Zagranichnaya et al., 2005). However, in human corneal epithelial cells, mouse endothelial cells and mouse mesangial cells, TRPC4 deficiency decreased SOCE (Tiruppathi et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2005). Furthermore, TRPC3 and TRPC7 effects on SOCE depend on their expression levels. At low expression levels, they are activated by passive Ca2+ store depletion and act as SOCE, while at high expression levels, they behave as Ca2+ store-independent Ca2+ influx channels (Worley et al., 2007). Therefore, it is necessary to continue to explore the function of TRPCs in SOCE.

Role of Store-Operated Calcium Entry in Cancer

Accumulating evidence has revealed that many cancers, such as breast, liver, lung, gastric, colon, and ovarian cancer, exhibit augmented SOCE and overexpression of STIM1 or ORAI1. SOCE inhibition through STIM1 or ORAI1 knockdown inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells, suggesting that SOCE may act as an oncogenic pathway (Yang et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2011; Yoshida et al., 2012; Motiani et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2014; Umemura et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015; Schmid et al., 2016; Xia et al., 2016; Goswamee et al., 2018; Wang Y. et al., 2018; Zang et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020). In addition, SOCE is believed to promote tumor angiogenesis through the increased secretion of VEGF by endothelial and cancer cells. For example, in cervical cancer, STIM1 regulates the production of VEGF to control the formation of blood vessels, and the formation of tumor could be impaired by inhibiting STIM1 (Chen et al., 2011). In addition, the potential therapeutic value of targeting SOCE in cancer has further been supported by the fact that STIM- and ORAI- mediated SOCE is essential for the secretion of cytokines and chemokines from T cells, mast cells, and macrophages, as well as in the differentiation and functions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. For example, the inhibition of SOCE by genetic deletion of ORAI1, STIM1, or STIM2 in murine CD4+ T cells impaired Th17 cell function, causing a decrease in the production of IL-17, which is believed to be proinflammatory factor important for tumor progression (Ma et al., 2010; Shaw et al., 2014; Mehrotra et al., 2019). Moreover, as candidate components of SOCE, TRP channels have been found to affect the survival, proliferation, and invasion of cancer cells (Shapovalov et al., 2016). For example, TRPC1 was confirmed to play different roles in tumorigenesis, inhibition of TRPC1 by siRNA or SOCE inhibitors could suppress the proliferation and invasion of cancer cells including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, malignant glioma and non-small-cell lung carcinoma (Bomben and Sontheimer, 2010; He et al., 2012; Tajeddine and Gailly, 2012).

In summary, SOCE promotes the proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells, and enhances tumor angiogenesis and the formation of a tumor-promoting inflammatory environment. Inhibition of SOCE may be a potential and effective therapy for cancers. In this review, we summarize the available inhibitors of SOCE (Tables 1, 2), discuss their effects and possible mechanisms (Table 3), and introduce a new viewpoint on the treatment of cancer.

TABLE 1.

Structures and IC50 of compounds.

| Compound | Structure | IC50 of SOCE inhibition | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| SKF96365 |

|

IC50 = 10.2 ± 1.2 μM in VSMCs | Zhang et al. (1999) |

| IC50 = 12 μM in Jurkat T cells | Chung et al. (1994) | ||

| IC50 = 1.2 μM in arterioles | McGahon et al. (2012) | ||

| IC50 = 60 μM in PLP-B lymphocyte cells | Dago et al. (2018) | ||

| 2-APB |

|

IC50 = 4.8 ± 0.6 μM in DT40 cells | Goto et al. (2010) |

| IC50 = 3.7 μM as inhibitor, >100 μM as activator in arterioles | McGahon et al. (2012) | ||

| IC50 = 3 μM in CHO cells | Ozaki et al. (2013) | ||

| IC50 = 17 ± 1 μM in human platelets | Giambelluca and Gende (2007) | ||

| IC50 = 15 μM in Jurkat T cells | Suzuki et al. (2010) | ||

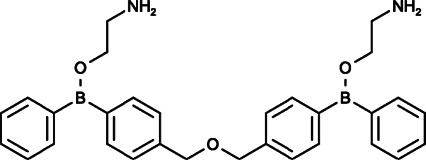

| DPB-162AE |

|

IC50 = 27 ± 2 nM in DT40 cells | Goto et al. (2010) |

| IC50 = 190 ± 6 nM in CHO cells | Goto et al. (2010) | ||

| IC50 = 200 nM in HEK293 cells | Hendron et al. (2014) | ||

| IC50 = 0.32 μM in Jurkat T cells | Suzuki et al. (2010) | ||

| DPB-163AE |

|

IC50 = 42 ± 3 nM in DT40 cells | Goto et al. (2010) |

| IC50 = 210 ± 20 nM in CHO cells | Goto et al. (2010) | ||

| IC50 = 600 nM in HEK293 cells | Hendron et al. (2014) | ||

| IC50 = 0.43 μM in Jurkat T cells | Suzuki et al. (2010) | ||

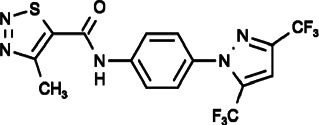

| BTP2 |

|

IC50 = 100 nM in Jurkat T cells | Ishikawa et al. (2003) |

| IC50 = ∼10 nM in peripheral blood T-lymphocytes | Zitt et al. (2004) | ||

| IC50 = 0.1–0.3 μM in HEK293 cells, DT40 B cells and A7r5 smooth muscle cells | He et al. (2005) | ||

| IC50 = 0.59 μM in RBL-2H3 cells | Schleifer et al. (2012) | ||

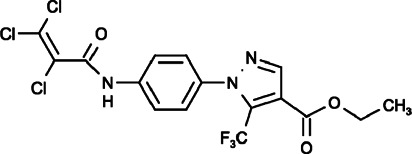

| Pyr3 |

|

IC50 = 0.5 μM in E13 cortical neurons | Gibon et al. (2010) |

| IC50 = 0.54 μM in RBL-2H3 cells | Schleifer et al. (2012) | ||

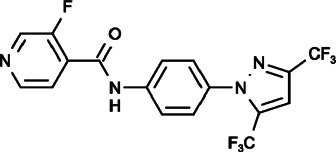

| Pyr6 |

|

IC50 = 0.49 μM in RBL-2H3 cells | Schleifer et al. (2012) |

| Pyr10 |

|

IC50 = 13.08 μM in RBL-2H3 cells | Schleifer et al. (2012) |

| GSK-5498A |

|

IC50 = ∼1 μM in human embryonic kidney cells | Rice et al. (2013) |

| IC50 = 3.7 μM in ASMCs | Chen and Sanderson (2017) | ||

| GSK-5503A |

|

IC50 = ∼4 μM in HEK cells | Derler et al. (2013) |

| GSK-7975A |

|

IC50 = ∼4 μM in HEK cells | Derler et al. (2013) |

| IC50 = 4.1 μM in ASMCs | Chen and Sanderson (2017) | ||

| IC50 = 0.34 μM in HLMCs | Ashmole et al. (2012) | ||

| Synta66 |

|

IC50 = ∼1 μM in Jurkat T cells | Di Sabatino et al. (2009) |

| IC50 = 3 μM in RBL-1 mast cells | Ng et al. (2008) | ||

| IC50 = 0.25 μM in HLMCs | Ashmole et al. (2012) | ||

| CAI |

|

IC50 = 2∼5 μM in Huh-7 cells | Enfissi et al. (2004) |

| CM4620 |

|

IC50 = 120 nM for ORAI1/STIM1-mediated SOCE in HEK 293 cells | Wen et al. (2015); Waldron et al. (2019) |

| IC50 = 900 nM for ORAI2/STIM1-mediated SOCE in HEK 293 cells | |||

| ML-9 |

|

IC50 = ∼16 μM in HEK293 cells | Smyth et al. (2008) |

| NPPB |

|

IC50 = 5 μM in Jurkat T cells | Li et al. (2000) |

| AnCoA4 |

|

Not found | Not found |

| RO2959 |

|

IC50 = 402 ± 129 nM in RBL-2H3 cells | Chen G. et al. (2013) |

| IC50 = 265 ± 16 nM in CD4+ T cells | Chen G. et al. (2013) | ||

| YZ129 |

|

IC50 = 820 ± 130 nM in HeLa cells | Liu et al. (2019) |

| MRS-1845 |

|

IC50 = 1.7 μM in HL-60 cells | Harper et al. (2003) |

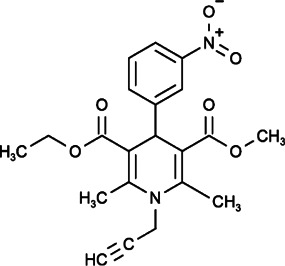

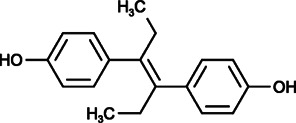

| DES |

|

IC50 = ∼1 μM in GBM cells | Liu et al. (2011) |

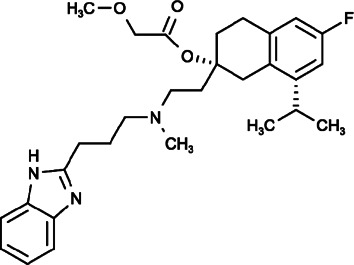

| Mibefradil |

|

IC50 = 52.6, 14.1, and 3.8 μM for ORAI1, ORAI2, and ORAI3 respectively in HEK-293 T-REx cells | Li et al. (2019) |

TABLE 2.

Targeting channels of compounds.

TABLE 3.

SOCE inhibitors in cancer research.

| Compound | Cancer type | Cell lines | Major effect | Possible mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SKF96365 | MG astrocytoma | U373 | Inhibition of cell growth | Promotes the accumulation of [3H]IP1 and inhibits the mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ | Lee et al. (1993); Arias-Montaño et al. (1998) |

| Cervical cancer | Hela | Inhibition of cell growth and cell migration | Promotes the accumulation of [3H]IP1 | Arias-Montaño et al. (1998); Chen Y.-T. et al. (2013) | |

| SiHa | Inhibits the activation of non-muscle myosin II and the formation of actomyosin via blocking SOCE channel | ||||

| Neuroblastoma | SK-N-MC | Inhibition of cell growth | Inhibits the mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ | Lee et al. (1993) | |

| Gastric cancer | AGS and MKN45 | Inhibition of cell growth and tumor formation | Arrests cell cycle in G2/M phase | Cai et al. (2009) | |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | CNE2 and HONE1 | Inhibition of cell proliferation and colony formation, promotion of apoptosis and cell-cycle | Distracts the transduction of oncogenic Ca2+ signaling | Zhang et al. (2015) | |

| Colorectal cancer | HCT116 and HT29 | Inhibition of cell growth and tumor formation, inducement of apoptosis, cell-cycle and autophagy | Inhibits the calcium/CaMKIIγ/AKT-mediated pathway | Jing et al. (2016) | |

| Prostate cancer | DU145 and PC3 | Inhibition of the survival and proliferation | Inhibits AKT/mTOR pathway and induces autophagy | Selvaraj et al. (2016) | |

| Multiple myeloma | KM3 and U266 | Inhibition of cell viability and proliferation, inducement of apoptosis | Arrests cell cycle in G2/M phase. Induces the reduction of [Ca2+]i | Wang W. et al. (2018) | |

| Ovarian cancer | SKOV3 | Inhibition of cell proliferation | Arrests cell cycle in G2/M phase through inhibiting TRPC channels | Zeng et al. (2013) | |

| Glioma and glioblastoma | U251, U87, D54MG, LN-229, T98G, U373 | Inhibition of cell growth and colony formation. Increase in the sensitivity to irradiation | Inhibits TRPC channels. Arrests cell cycle in G2/M phase | Bomben and Sontheimer (2008); Ding et al. (2010); Song et al. (2014) | |

| Breast tumor | MDA-MB-231 | Inhibition of cell migration, inhibition of tumor Metastasis in mice | Impairs the assembly and disassembly of focal adhesions | Yang et al. (2009) | |

| Melanoma | WM793 | Inhibition of cell invasion | Blocks the formation, activity of invadopodium | Sun et al. (2014) | |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | A549 | Inhibition of cell migration and proliferation | Inhibits TRPC channels and SOCE channel | Wang Y. et al. (2018) | |

| 2-APB | Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) | RD, RH30 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Inhibits SOCE channel | Schmid et al. (2016) |

| Melanoma | WM793 | Inhibition of cell invasion and lung metastasis | Blocks the formation, activity and maturation of invadopodium | Sun et al. (2014) | |

| Cervical cancer | SiHa | Inhibition of cell migration | Inhibits actomyosin formation and cellular contractile force via blocking SOCE channel | Chen Y.-T. et al. (2013) | |

| Ovarian cancer | SKOV3 | Inhibition of cell proliferation | Inhibits TRPC channels | Zeng et al. (2013) | |

| Breast cancer | MDA-MB-231, AU565, T47D | Inhibition of cell viability and proliferation | Arrests cell cycle in S phase | Liu et al. (2020) | |

| Prostate cancer | DU145, PC3 | Inhibition of cell migration | Inhibits EMT via blocking TRPM7 channel activity | Sun et al. (2018) | |

| Glioma and glioblastoma | D54MG, U87 | Inhibition of cell development, migration and invasion | Inhibits SOCE channel and TRPC channels (TRPC1, TRPC3, TRPC5, TRPC6) | Bomben and Sontheimer (2008); Shi et al. (2015) | |

| GBM (Glioblastoma multiforme) | A172 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Inhibits TRPM7 channel | Leng et al. (2015) | |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | CNE2, 5-8F, 6-10B | Inhibition of cell migration and invasion | Inhibits TRPC1 and TRPM7 channel | Chen et al. (2010); He et al. (2012) | |

| HK1 | Inhibition of angiogenesis | Inhibits VEGF production and endothelial tube formation by blocking SOCE | Ye et al. (2018) | ||

| Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | H1975, A549, LLC-1 | Inhibition of primary and metastatic Lewis lung cancer | Inhibits intracellular Ca2+mobilization | Qu et al. (2018) | |

| BTP2 | Colon cancer | HT29 | Inhibition of cell growth | Inhibits SOCE channel and transcription cycling of topoisomerase-II α | Núñez et al. (2006) |

| Cervical cancer | SiHa | Inhibition of cell migration | Inhibits actomyosin formation and cellular contractile force via blocking SOCE channel | Chen Y.-T. et al. (2013) | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) | RD, RH30 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Inhibits SOCE channel | Schmid et al. (2016) | |

| Breast cancer | MDA-MB-468 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Inhibits SOCE channel | Azimi et al. (2018) | |

| Prostate cancer | PC-3 | Inhibition of cell invasion | Inhibits drebrin to bind to actin filaments | Dart et al. (2017) | |

| Pyr3 | triple negative breast cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, inducement of apoptosis and cell death | Affects the TRPC3/RASA4/MAPK Pathway | Wang et al. (2019) |

| Melanoma | C8161 | Inhibition of cell proliferation and migration | Inhibits TRPC3 channel | Oda et al. (2017) | |

| Glioblastoma multiforme | LN229, U87 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Dephosphorylates focal adhesion kinase and myosin light chain via inhibiting TRPC3 channel | Chang et al. (2018) | |

| CAI | Melanoma | A2058 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, adhesion and motility | Inhibits the receptor-mediated stimulation of effector enzymes | Kohn and Liotta (1990); Kohn et al. (1992) |

| Inhibition growth and metastasis of transplanted xenografts | Inhibits calcium fluxes, arachidonic acid release, and phosphoinositides generation | ||||

| Breast cancer | MDA-MB-231 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, adhesion and motility | Inhibits the receptor-mediated stimulation of effector enzymes | Kohn and Liotta. (1990) | |

| Ovarian cancer | OVCAR-3 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, adhesion and motility | Inhibits the receptor-mediated stimulation of effector enzymes | Kohn and Liotta (1990); Kohn et al. (1992) | |

| Inhibition growth and metastasis of transplanted xenografts | Inhibits calcium fluxes, arachidonic acid release, and phosphoinositides generation | ||||

| Colon cancer | HT-29 | Inhibition of the formation and growth of experimental pulmonary metastases in nude mice | Inhibits calcium fluxes, arachidonic acid release, and phosphoinositides generation | Kohn et al. (1992) | |

| Prostate cancer | DU-145, PPC-1, PC3, LNCaP | Inhibition of cell proliferation | Inhibits calcium fluxes and PSA production | Wasilenko et al. (1996) | |

| Glioblastoma | A172, T98G, U87, H4, U251 | Inhibition of cell proliferation and adhesion | Inhibits calcium fluxes and calcium-sensitive signal transduction pathways | Jacobs et al. (1997) | |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | EVSCC14/17M, EVSCC19M, EVSCC18, UMSCC10A, FaDu | Inhibition of cell growth and invasion | Inhibits calcium fluxes | Wu et al. (1997) | |

| Hepatoma | Hep G2, Huh-7 | Inhibition of cell proliferation | Inhibits calcium entry | Enfissi et al. (2004) | |

| Small cell lung cancer | NCI-H209, NCI- H345 | Inhibition of cell growth, inhibition of xenograft proliferation in nude mice | Inhibits calcium fluxes | Moody et al. (2003) | |

| Inhibits the angiogenesis | |||||

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 32D P210, 32D E255K | Inhibition of cell growth and decrease of BCR-ABL | Inhibits calcium influxes and signal transduction | Corrado et al. (2011) | |

| Liver metastases from B16F1 melanoma | B16F1 | Decrease of the volume size and angiogenesis of tumor | Reduces the number of microvessels/mm2 and microvessel size | Luzzi et al. (1998) | |

| Lewis lung carcinoma | LLC cell | Inhibition of cell growth | Inhibits production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in TAMs | Ju et al. (2012) | |

| Melanoma | OVA-B16 | Inhibition of tumor growth | Activates the CD8+ T cells and stimulates IDO1-Kyn metabolic circuitry | Shi et al. (2019) | |

| RP4010 | Esophageal cancer | KYSE-30, KYSE-150, KYSE-790, KYSE-190 | Inhibition of cell proliferation and tumor growth | Inhibits SOCE channel-mediated Ca2+ oscillations | Cui et al. (2018) |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | L3.6pl, BxPC-3, MiaPaCa-2 | Inhibition of cell proliferation and colony formation | Inhibits CRAC channel | Khan et al. (2020) | |

| ML-9 | Pancreatic cancer | MIA PaCa-2, Panc1, BxPC3 | Inhibition of cell invasion and adhesion | Inhibits MLCK to decrease the activity of cytoskeleton | Kaneko et al. (2002) |

| Prostate cancer | LNCaP, PC3, DU-145 | Inducement of prostate cell death | Stimulates autophagy via modulating Ca2+ homeostasis | Kondratskyi et al. (2014) | |

| NPPB | Ovarian cancer | A2780 | Inhibition of cell adhesion and invasion | Inhibits chloride channels leading to inhibition of [Ca2+]i | Li et al. (2009) |

| YZ129 | Glioblastoma | U87 | Inhibition of cell proliferation, migration and mobility | Inhibits calcineurin-NFAT pathway | Liu et al. (2019) |

| NSAIDs | Colon cancer | HT29 | Inhibition of cell growth | Inhibits SOCE channel and COX-2 expression | Núñez et al. (2006); Wang et al. (2015) |

Store-Operated Calcium Entry-Targeted Compounds in the Application of Cancer Treatment

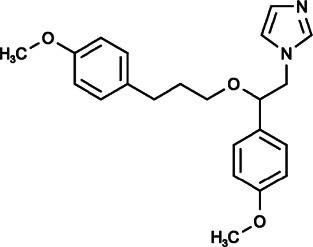

SKF 96365

(1-[2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-[3-(4-Methoxyphenyl)propoxy]ethyl]imidazole;hydrochloride)

SKF 96365 is structurally distinct from classic Ca2+ antagonists, drugs or compounds that inhibit Ca2+ entry by directly inhibiting Ca2+ channels or affecting Ca2+ pools. It shows selectivity in blocking receptor-mediated Ca2+ entry (RMCE), the Ca2+ influx that is independent of depolarization and caused by receptor occupation, leading to a significant increase in [Ca2+]i biologically, with no impact on internal Ca2+ release in platelets, neutrophils or endothelial cells (Spedding, 1982; Merritt et al., 1990; Cabello and Schilling, 1993), and the inhibition of RMCE exerted by SKF 96365 could inhibit [3H]-thymidine incorporation, interleukin-2 (IL-2) synthesis and cell proliferation of peripheral blood lymphocytes (Chung et al., 1994). It was also found that SKF 96365 could block store-independent TRP channels in osteoclasts and capacitative Ca2+ entry (CCE) in astrocytes (Wu et al., 1999; Bennett et al., 2001).

Iwamuro et al. found, for the first time, that SKF 96365 sensitively inhibited the SOCE activated by ET-1 at high concentrations (Iwamuro et al., 1999). As a SOCE inhibitor, SKF 96365 was reported to inhibit cell proliferation in many cancers by inducing cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase (Nordström et al., 1992; Lee et al., 1993; Arias-Montaño et al., 1998; Cai et al., 2009; Zeng et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015; Jing et al., 2016; Wang W. et al., 2018). Autophagy seems to play different roles in the pharmacological mechanism of SKF 96365. Inhibition of SOCE by SKF 96365 inhibited the AKT/mTOR pathway, induced autophagic cell death and decreased the survival, and proliferation of PC3 and DU145 prostate cancer cells (Selvaraj et al., 2016), while in colorectal cancer cells, SKF 96365 was reported to induce cytoprotective autophagy to delay apoptosis through the inhibition of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIγ (CaMKIIγ)/AKT signaling cascade, and autophagy inhibition could significantly augment the anticancer effect of SFK 96365 in mouse xenograft models (Jing et al., 2016).

In addition, SKF 96365 could also effectively inhibit the metastasis of cancers. It could impair the assembly and disassembly of focal adhesions of breast cancer cells (Yang et al., 2009), block the formation and activity of invadopodium in melanoma cells (Sun et al., 2014), and it could also inhibit cell migration by inactivating non-muscle myosin II and reducing actomyosin formation and contractile force in cervical and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells (Chen Y.-T. et al., 2013; Wang Y. et al., 2018). In addition to inhibiting growth and colony formation independently through the blockage of Ca2+ channels, for example, through the blockage of TRPC channels in glioma cells (Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008; Ding et al., 2010; Song et al., 2014), SKF 96365 could also enhance the sensitivity of glioma cell lines to irradiation (Ding et al., 2010), suggesting that SKF 96365 may be developed not only as an anti-chemotherapy, but also as an adjuvant drug for radiotherapy.

In summary, the antineoplastic effects of SKF 96345 are universal. However, it has been confirmed that its effects are nonspecific (Franzius et al., 1994), and therefore it is necessary to conduct more studies to clearly delineate its specific mechanisms.

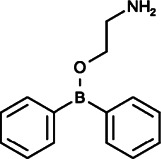

2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate and Analogs

2-APB (2-Diphenylboranyloxyethanamine)

Initial studies reported that 2-APB, as a novel membrane-penetrable modulator, inhibited Ca2+ release induced by IP3 without affecting IP3 binding to IP3R (IC50 = 42 µM) (Maruyama et al., 1997). Subsequently, 2-APB was found to be a reliable blocker of SOCE but an inconsistent inhibitor of IP3-induced Ca2+ release. With further study, it was found that 2-APB could exert both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on Ca2+ influx through CRAC channels: at low concentrations (1–5 µM), it activated SOCE pathway, while at high concentrations (≥10 µM), it blocked SOCE pathway completely (Prakriya and Lewis, 2001). The mechanisms of the dual effects of 2-APB on SOCE are also complicated: 2-APB could inhibit STIM1 directly by facilitating the coupling between CC1 (coiled-coil 1) and SOAR (STIM-ORAI-activating region) of STIM1. On the other hand, 2-APB could also impair the functions of STIM1 indirectly by interrupting the coupling between STIM1 and the mutant, ORAI1-V102C (Peinelt et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2016). Moreover, 2-APB could directly gate and dilate the pore diameter of ORAI1 and ORAI3 to regulate SOCE pathway without affecting STIM1 (DeHaven et al., 2008; Peinelt et al., 2008; Schindl et al., 2008; Yamashita et al., 2011; Amcheslavsky et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2016; Kappel et al., 2020). 2-APB also exerts multifaceted effects on transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (Colton and Zhu, 2007). It was reported that 2-APB could act as an agonist of TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV3, TRPM6, and TRPC3 channels(Ma et al., 2003; Chung et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2004; Li et al., 2006), however, it exerted inhibitory roles on TRPC1, TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, TRPC6, TRPC7, TRPM2, TRPM3, TRPM7, TRPM8, TRPV3, and TRPV6 channels (Hu et al., 2004; Poburko et al., 2004; Lievremont et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006; Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008; Togashi et al., 2008; Chokshi et al., 2012; Kovacs et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2018). Among these TRP channels, 2-APB could close the TRPV6 channel through protein–lipid interactions by binding to TRPV6 directly, and TRPV3 also was found to undergo similar structural changes triggered by 2-APB (Singh et al., 2018; Zubcevic et al., 2018).

When used as a blocker of SOCE at high concentrations, 2-APB displayed anticancer effects on rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, glioblastoma, lung cancer, melanoma, and cervical cancer (Bomben and Sontheimer, 2008; Chen Y.-T. et al., 2013; Zeng et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2014; Leng et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2015; Schmid et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020). For instance, in breast cancer, 2-APB inhibited cell viability, and proliferation through inhibiting TRPM7 channel by arresting cell cycle in S phase not by promoting cell death (Liu et al., 2020). In melanoma and cervical cancer, 2-APB could reduce migration and invasion by inhibiting actomyosin formation, invadopodium assembly and maturation, through mechanisms similar to those of SKF 96365 action (Chen Y.-T. et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2014). 2-APB in NPC could also attenuate adhesive and invasive abilities by inhibiting TRPC1 and TRPM7 (Chen et al., 2010; He et al., 2012). Furthermore, it was reported that 2-APB could effectively antagonize the angiogenesis of NPC in vivo by inhibiting VEGF production and endothelial tube formation through the blockage of SOCE (Ye et al., 2018). In another study, 2-APB sensitized NSCLC cells to the antitumor effect of bortezomib (BZM) via suppression of Ca2+-mediated autophagy (Qu et al., 2018).

These effects suggest that 2-APB is attractive as a potentially potent therapy for primary cancer and metastatic cancer.

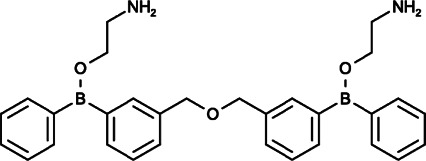

2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate and Analogs

As 2-APB is a promising but not entirely specific SOCE inhibitor, Goto et al. explored two novel 2-APB structurally isomeric analogs in order to develop more specific and potent SOCE inhibitors: DPB-162AE and DPB-163AE (Goto et al., 2010). These two diphenylborinate (DPB) compounds are 100-fold more potent than 2-APB, and they are able to inhibit the clustering of STIM1 and block the ORAI1 or ORAI2 activity induced by STIM1 by inactivating the SOAR domain in STIM1. In particular, DPB-162 AE could consistently inhibit endogenous SOCE regardless of whether the concentration was high or low and exerted little effect on L-type Ca2+ channels, TRPC channels, or Ca2+ pumps when exerting maximal inhibitory effect on Ca2+ entry (Goto et al., 2010; Hendron et al., 2014; Bittremieux et al., 2017). However, the actions of DPB-163AE are more complex, showing a similar pattern to 2-APB by activating SOCE at low concentrations and inhibiting SOCE at higher levels (Goto et al., 2010).

Moreover, similar to 2-APB, at low concentrations (∼100 nM), both DPB-162AE and DPB-163AE could facilitate Orai3 currents, and at high concentrations (>300 nM), they transiently activated ORAI3 currents and then deactivated them. DPB compounds have been proven to activate ORAI3 in a STIM1-dependent manner, but they could not change the pore diameter of ORAI3, which is different from the mechanisms of 2-APB. It is speculated that because they are larger than 2-APB, DPB compounds are unable to enter the pore of ORAI3 (Goto et al., 2010; Hendron et al., 2014). In addition, DPB-162AE was reported to provoke leakage of Ca2+ from the ER into the cytosol in HeLa and SU-DHL-4 cells at concentrations required for adequate SOCE inhibition (Hendron et al., 2014; Bittremieux et al., 2017).

Although there have been no studies on DPB compounds with respect to cancer treatment to date, considering the specific inhibition of SOCE, DPB compounds are expected to be developed as potential anticancer drugs.

Pyrazole Derivatives

Pyr2 (N-[4-[3,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazol-1-yl]phenyl]-4-Methylthiadiazole-5-Carboxamide)

Pyr2, also known as BTP2 or YM-58483, was initially found to be able to inhibit SOCE, leading to impaired IL-2 production and NFAT dephosphorylation in Jurkat cells without affecting the T cell receptor (TCR) signal transduction cascade (Ishikawa et al., 2003). BTP2 also showed complicated effects on TRP channels, TRPC1, TRPC3, TRPC5, and TRPC6 channels were inhibited effectively; however, TRPM4 was activated by BTP2 at low concentrations in a dose-dependent manner. BTP-mediated facilitation of TRPM4, which is a Ca2+-activated cation channel that decreases Ca2+ influx by depolarizing lymphocytes, is the main mechanism for the suppression of cytokine release. Furthermore, it has been reported that the mechanism of inhibiting TRP channels, such as TRPC3 and TRPC5, involved in reducing their open probability rather than changing their pore properties without affecting the other Ca2+ signals in T cells including Ca2+ pumps, mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling and ER Ca2+ release (Zitt et al., 2004; He et al., 2005; Schwarz et al., 2006; Takezawa et al., 2006; Oláh et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2017).

BTP2 has exhibited inhibitory effects on several types of allergic inflammation, including autoimmune and antigen induced diseases through the suppression of cytokine release (IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) and T cell proliferation (Ohga et al., 2008; Law et al., 2011; Geng et al., 2012). Although many studies have indicated that BTP2 affects cancer through the modulation of immune cells, previous reports have mainly focused on the direct inhibition of cell proliferation, migration, and invasion of cancer cells themselves. For example, in colon cancer, BTP2 obviously decreased cell growth through direct SOCE inhibition (Núñez et al., 2006). BTP2 could also inhibit cell migration of cervical cancer, rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), and breast cancer via blockage of SOCE (Chen Y.-T. et al., 2013; Schmid et al., 2016; Azimi et al., 2018); furthermore, the inhibition of cell migration in cervical cancer was due to the inhibition of actomyosin reorganization and contraction forces, similar to the effects of SKF96365 and 2-APB (Chen Y.-T. et al., 2013). It was also found that BTP2 could inhibit the proliferation and tubulogenesis of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), which are essential for the vascularization and metastatic switching of solid tumors (Dragoni et al., 2011; Lodola et al., 2012). On the other hand, BTP2 could inhibit the invasion of prostate cancer cells by impeding the binding of drebrin to actin filaments, with a SOCE independent mechanism (Dart et al., 2017).

In summary, the mechanism and effect of BTP2 on cancer are multi-aspect, and it is necessary to carry out further research on them for clarification.

Pyr3 (Ethyl1-(4-(2,3,3-Trichloroacrylamido)phenyl)-5-(Trifluoromethyl)-1h-Pyrazole-4-Carboxylate)

Pyr3 has mainly been recognized for directly and selectively inhibiting TRPC3 with attenuated activation of Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways, and structure-function relationship studies showed that the trichloroacrylic amide group is important for the TRPC3 selectivity of Pyr3 (Kiyonaka et al., 2009). The blockade of TRPC3-mediated Ca2+ signaling pathways by Pyr3 reduced cell proliferation, induced cell apoptosis and sensitized cell death to chemotherapeutic agents in triple-negative breast cancer through the inhibition of TRPC3-Ras GTPase-activating protein 4 (RASA4)-MAPK signaling cascade (Wang et al., 2019). In melanoma, Pyr3 also decreased the cell proliferation and migration in vitro and inhibited tumor growth in vivo by inhibiting TRPC3 and its downstream JAK/STAT5 and AKT pathways (Oda et al., 2017). Chang et al. reported that Pyr3 could inhibit the migration and invasion of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells and reduce the size of tumor xenografts significantly by dephosphorylating focal adhesion kinase and myosin light chain (Chang et al., 2018). Subsequently, Pyr3 was found to effectively inhibit ORAI1-mediated SOCE in HEK293 cells and mast cells (RBL-2H3) in a dose dependent manner, and the amid-bond linked side-group pivotal for TRPC subtype selectivity was also proposed as a potential structural determinant for the SOCE inhibitory action (Schleifer et al., 2012).

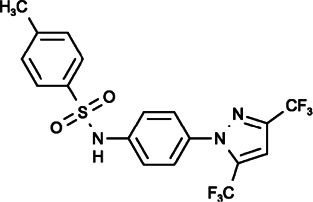

Pyr6 and Pyr10 (N-[4-[3,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazol-1-yl]phenyl]-3-Fluoropyridine-4-Carboxamide), (N-[4-[3,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazol-1-yl]phenyl]-4-Methylbenzenesulfonamide)

It was reported that Pyr6 could inhibit both ORAI1-mediated SOCE and TRPC3 channels in mast cells leading to the suppression of mast cell activation, however, its effect on SOCE inhibition was 37-fold times that of TRPC3 inhibition, and it differed from the effect of Pyr10, which could specifically inhibit TRPC3 and had no effect on SOCE (Schleifer et al., 2012; Chauvet et al., 2016), thereby suggesting that Pyr6 and Pyr10 can be used as valuable tools to distinguish SOCE and TRPC3 channels.

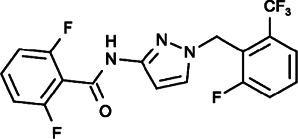

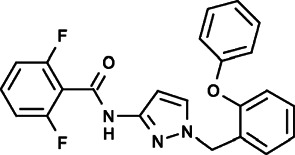

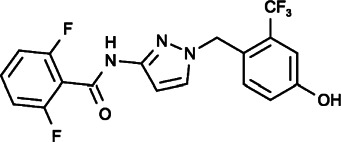

GSK-5503A, GSK-7975A and GSK-5498A (2,6-Difluoro-N-[1-[(2-Phenoxyphenyl)methyl]pyrazol-3-yl]benzamide), (2,6-Difluoro-N-[1-[[4-Hydroxy-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]methyl]pyrazol-3-yl]benzamide), (2,6-Difluoro-N-[1-[[2-Fluoro-6-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]methyl]pyrazol-3-yl]benzamide)

Several novel pyrazole compounds including GSK-5503A, GSK-7975A, and GSK-5498A have been developed by GlaxoSmithKline as specific blockers of SOCE. GSK-5503A and GSK-7975A could inhibit STIM1-mediated ORAI1 and ORAI3 currents potentially via an allosteric effect on the selectivity filter of ORAI with a slow onset of action that did not have effects on STIM1-STIM1 oligomerization or STIM1-ORAI1 coupling (Yamashita et al., 2007; Derler et al., 2013). GSK-7975A could also efficiently inhibit the TRPV6 channel, possibly due to its architectural similarities to the selectivity filters of ORAI channels (Owsianik et al., 2006; Derler et al., 2013; Jairaman and Prakriya, 2013). GSK-5498A and GSK-7975A have been used to inhibit mediator and cytokine release from mast cells and T cells (such as IFN-γ and IL2) in multiple human and rat preparations by completely inhibiting SOCE (Rice et al., 2013). Although the roles of immune cells and cytokines are complicated in the tumor microenvironment, these compounds are expected to be applied as cancer treatments that function through anticancer immunity processes under certain circumstances.

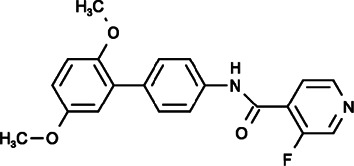

Synta66 (N-[4-(2,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)phenyl]-3-Fluoropyridine-4-Carboxamide)

Synta66, also known as GSK1349571A, has garnered extensive attention in recent years because of its ability to selectively inhibit CRAC channels without affecting on PDGF- or ATP-evoked Ca2+ release, overexpressed TRPC5 channels, native TRPC1/5-containing channels, STIM1 clustering or nonselective store-operated cationic currents (Li et al., 2011). It has been confirmed that the potency of SOCE inhibition is directed against Orai1 in the order of Synta66 > 2-APB > GSK-7975A > SKF96365 > MRS1845 in human platelets (van Kruchten et al., 2012). By inhibiting SOCE effectively and specifically, Synta66 could inhibit the receptor-triggered mutual activation between Syk activation and Ca2+ influx in the RBL mast cell line, reduce the release of histamine, leukotriene C4 (LTC4), and cytokines (such as IL-5, IL-8, IL-13, and TNF-α) in human lung mast cells (HLMCs), and inhibit the expression of T-bet and the production of IL-2, IL17, and IFN-γ in lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) and biopsy specimens obtained from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients (Ng et al., 2008; Di Sabatino et al., 2009; Ashmole et al., 2012). Azimi et al. compared the pharmacological inhibitory effects of Synta66 and BTP2 on SOCE pathway in breast cancer cell lines. They found that both Synta66 and BTP2 could inhibit the protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2) activator, and trypsin and EGF produced Ca2+ influx and serum-activated migration of MDA-MB-468 cells (Azimi et al., 2018). However, interestingly, Synta66, but not BTP2, had no effect on proliferation or EGF-activated cell migration, which are realized through unexplored mechanisms (Azimi et al., 2018). To date, no study has investigated whether Synta66 has anti-tumor effects in other cancers, nevertheless, Synta66 still has great potential to be developed as an available therapy for tumor treatment due to its specific and effective inhibition of SOCE.

Monoclonal Antibodies

Anti-ORAI1 Monoclonal Antibodies

Lin et al. developed high-affinity fully human mAbs to human ORAI1, that bind to amino acid residues 210–217 of the human ORAI1 extracellular loop 2 domain (ECL2). These mAbs potently inhibited the SOCE, NFAT translocation and cytokine secretion from Jurkat T cells and in human whole blood (Lin et al., 2013). Another mAb to human native ORAI1, generated by Cox, also binds to ECL2 and could block the function of T cells both in vitro and in vivo, including the inhibition of T cell proliferation and cytokine production in immune cells isolated from rheumatoid arthritis patients and showed efficacy on an anti-ORAI1 human T cell-mediated graft-versus host disease (GvHD) mouse model (Cox et al., 2013), suggesting that mAb may be a novel treatment for humans with autoimmune diseases. Taken together, since anti-ORAI1 mAbs could impact on the autoimmune response, we speculate that they also show great potential to be used as cancer therapy by modulating of the tumor immune microenvironment.

Inhibitors in Clinical Trials

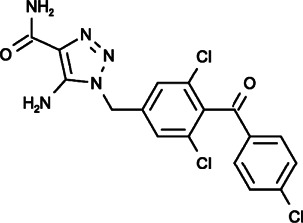

Carboxyamidotriazole (5-Amino-1-[[3,5-Dichloro-4-(4-Chlorobenzoyl)phenyl]methyl]triazole-4-Carboxamide)

CAI (carboxyamidotriazole), also called L-651582, is one of the SOCE inhibitors that has been evaluated in clinical trials. It was initially developed as a coccidiostat and was confirmed to inhibit calcium influx, including SOCE, RMCE and VDCE (Hupe et al., 1991; Kohn et al., 1994; Sjaastad et al., 1996). Through the inhibition of Ca2+ influx and related signaling processes, such as receptor-associated tyrosine phosphorylation, arachidonic acid generation, and nucleotide biosynthesis, CAI displayed effective anticancer effects, including antiproliferative, antimigratory, antiangiogenic and antimetastatic properties, in a broad range of human tumors, including melanoma, glioblastoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), hepatoma, small cell lung cancer (SCLC), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), and ovarian, breast, colon and prostate cancer (Kohn and Liotta, 1990; Kohn et al., 1992; Wasilenko et al., 1996; Jacobs et al., 1997; Wu et al., 1997; Luzzi et al., 1998; Moody et al., 2003; Enfissi et al., 2004; Corrado et al., 2011). Moreover, CAI could exert its anti-tumor activity through modulation of the tumor immune microenvironment by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokine production (such as TNF-α) in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), promoting IFN-γ release from activated CD8+ T cells or stimulating the IDO1-Kyn metabolic circuitry (Ju et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2019).

As a potential anticancer drug, CAI has been tested in phase I/II/III clinical trials, some of which showing that CAI could stabilize and improve the condition of patients with pancreaticobiliary carcinomas, melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, epithelial ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, glioblastoma and other anaplastic gliomas while exhibiting a limited toxicity profile (Figg et al., 1995; Kohn et al., 1996; Bauer et al., 1999; Hussain et al., 2003; Hillman et al., 2010; Das, 2018; Omuro et al., 2018). However, its performance was barely satisfactory in many clinical trials, preventing it from being a first-line chemotherapy drug (Stadler et al., 2005).

RP4010

RP4010 was developed by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals. It was confirmed to block SOCE and SOCE-mediated Ca2+ oscillations in a dose-dependent manner, leading to the inhibition of NF-κB/p65 translocation to nuclei, thus impeding the proliferation and in ESCC xenograft tumor growth (Cui et al., 2018). In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, RP4010 inhibited cancer cell proliferation and colony formation by reducing Akt/mTOR and Ca2+ influx-mediated NFAT signaling. Furthermore, RP4010 combined with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel could enhance anticancer activities in PDAC cells and patient-derived xenografts, indicating the potential of RP4010 as an anticancer chemotherapy (Khan et al., 2020). Indeed, RP4010 is in phase I/IB clinical trials currently.

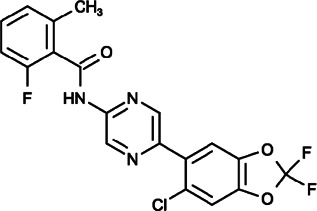

CM4620 (N-[5-(6-Chloro-2,2-Difluoro-1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl)pyrazin-2-yl]-2-Fluoro-6-Methylbenzamide)

CM4620, also called CM-128, was developed by CalciMedica and tested in phase I/II clinical trials to reduce pancreatitis. It could inhibit cell death pathway activation by SOCE inhibition in pancreatic acinar cells, thus leading to markedly reduced acute pancreatitis in mouse models (Wen et al., 2015). A recent study further demonstrated that in acute pancreatitis, CM4620 could not only inhibit the necrosis of parenchymal pancreatic acinar cells but could also prevent the activation of immune cells to reduce inflammation (Waldron et al., 2019). Although the effect of CM4620 on cancer cells is still unknown, it has the potential to be developed as a cancer therapy through its regulation of tumor immune cells.

Other Small Molecular Inhibitors

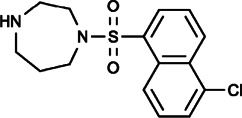

ML-9 (1-(5-chloronaphthalen-1-yl)sulfonyl-1,4-diazepane) was initially described as an inhibitor of myosin light chain kinases (MLCKs) that binds at or near the ATP-binding site at the active center of kinases with or without Ca2+ calmodulin (Saitoh et al., 1987). Shortly thereafter, ML-9 was found to inhibit agonist-stimulated Ca2+ entry in endothelial cells without affecting the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Watanabe et al., 1996), and it was confirmed to inhibit SOCE in a dose-dependent manner by blocking rearrangement and puncta formation of STIM1 without inhibiting MLCKs. Thus far, ML-9 is the only inhibitor of STIM1 translocation (Smyth et al., 2008). Furthermore, ML-9 could also inhibit the activity of TRPC5 channel by impairing its plasma membrane localization through MLCK inhibition (Shimizu et al., 2006), causing apoptosis in both untransformed and transformed epithelial cells, retarding the growth of mammary and prostate cancer cells and blocking the invasion and adhesion of human pancreatic cancer cells (Kaneko et al., 2002). In another study, ML-9 reduced SOCE and induced Ca2+-dependent autophagy to promote the death of prostate cancer cells, but the effect of ML-9 on autophagy was independent of STIM1 and SOCE inhibition, suggesting that ML-9 may exert its effects on cancer cells through multiple mechanisms. Moreover, ML-9 combined with docetaxel could enhance the cell death of LNCaP, PC3 and DU-145 cells, suggesting that ML-9 may be developed as an adjuvant to anticancer chemotherapy (Kondratskyi et al., 2014).

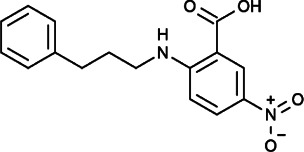

NPPB (5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)-benzoic acid), frequently used as a blocker of chloride channels, could also reduce CCE in endothelial cells (Gericke et al., 1994). It was also confirmed that NPPB could directly interact with CRAC to reversibly inhibit Ca2+ influx in Jurkat cells in a dose-dependent manner (Li et al., 2000). In ovarian cancer, NPPB could significantly inhibit A2780 cell adhesion and invasion (Li et al., 2009).

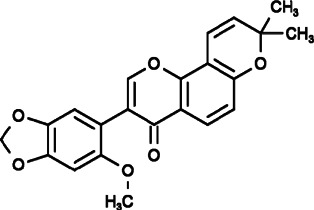

AnCoA4 (3-(6-methoxy-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-8,8-dimethylpyrano[2,3-f]chromen-4-one) was identified by screening small-molecule microarray (SMM) using minimal functional domains of STIM1 and ORAI1, and it was found to inhibit Ca2+ influx by binding to the C-terminus of ORAI1 directly to perturb the interaction between STIM1 and ORAI1 by reducing the affinity of ORAI1 for STIM1. Through SOCE inhibition, AnCoA4 blocked T cell activation and inhibited the T cell-mediated immune response in vitro and in vivo, indicting the possibility that it can be used in therapeutic areas, including immunomodulation, inflammation and cancer (Sadaghiani et al., 2014).

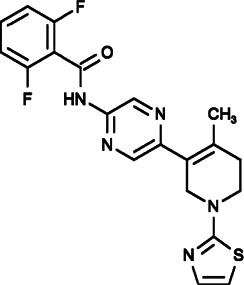

RO2959 (2,6-difluoro-N-[5-[4-methyl-1-(1,3-thiazol-2-yl)-3,6-dihydro-2H-pyridin-5-yl]pyrazin-2-yl]benzamide) could specifically block SOCE by inhibiting the IP3-dependent CRAC current in native RBL-2H3 cells, CHO cells with STIM1/ORAI1 overexpression and human primary CD4+ T cells, resulting in a decrease in TCR-triggered gene expression, cell proliferation and cytokine production in T cells (Chen G. et al., 2013).

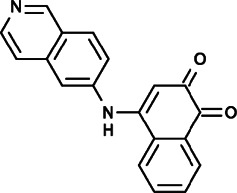

YZ129 (4-(isoquinolin-6-ylamino)-naphthalene-1,2-dione) was identified because of its inhibition of thapsigargin-triggered Ca2+ influx and NFAT nuclear entry through an automated high-content screening platform and it was found to exhibit potent anti-tumor activity against glioblastoma. It could bind to HSP90 directly and antagonize its calcineurin-chaperoning effect to reduce NFAT nuclear translocation and inhibit other key proto-oncogenic pathways, including hypoxic and glycolytic pathways and the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis, thus leading to cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase of glioblastoma and promoting apoptosis and inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and migration (Liu et al., 2019).

MRS-1844 (DHPs-32) and MRS-1845 (DHPs-35) are compounds in the 1,4-dihydropyridine (DHP) family, and they were confirmed to inhibit store-operated calcium channels and reduce voltage-dependent L-type calcium channels. In addition, their potency in SOCE inhibition was much smaller than that of common SOCE inhibitors (the reported order is Synta66 > 2-APB > GSK-7975A > SKF96365 > MRS1845) (Harper et al., 2003; van Kruchten et al., 2012).

Repurposing FDA-Approved Drugs

In addition to the abovementioned compounds targeting SOCE, other compounds that have been approved for clinical use in corresponding diseases were confirmed to inhibit SOCE. The ability of these compounds to inhibit Ca2+ influx through SOCE indicates the importance of learning more about their pharmacological properties and mechanisms, and the potential to extend their clinical indications.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES, 4-[(E)-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-hex-3-en-3-yl]-phenol) is a potent synthetic estrogen used for estrogen therapy in prostate and breast cancer. It was reported to inhibit SOCE and Ca2+ influx in a variety of cell types without affecting the whole-cell monovalent cation current mediated by TRPM7 channels. Trans-stilbene, a close structural analog of DES that lacks hydroxyl and ethyl groups, had no effect on CRAC current, further suggesting the specificity of DES for SOCE (Zakharov et al., 2004; Ohana et al., 2009; Dobrydneva et al., 2010).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to relieve pain, fever and inflammation. Epidemiological studies worldwide have demonstrated that NSAIDs also have cancer-protective effects, as these drugs are associated with a reduced risk of various types of cancer. In colon cancer, it has been reported that NSAIDs could exert antiproliferative effects through SOCE inhibition, and salicylate, the main aspirin metabolite, is considered a mild mitochondrial uncoupler that prevents mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and promotes the Ca2+-dependent inactivation of SOCE, thus inhibiting the proliferation of HT29 cells (Núñez et al., 2006). Another study suggested that STIM1 overexpression promoted colorectal cancer progression through an increase in the expression of the pro-inflammatory and pro-metastatic enzyme cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). The inhibition of COX-2 with two NSAIDs, ibuprofen and indomethacin, abrogated STIM1-induced colorectal cancer (CRC) progression (Wang et al., 2015).

Mibefradil ([(1S,2S)-2-[2-[3-(1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)propyl-methylamino]ethyl]-6-fluoro-1-propan-2-yl-3,4-dihydro-1H-naphthalen-2-yl]2-methoxyacetate), a T-type Ca2+ channel blocker that was initially developed as a cardiovascular drug, was recently found to inhibit SOCE by blocking ORAI channels in a dose-dependent and reversible manner to significantly inhibit cell proliferation, induce cell apoptosis and arrest cell cycle in S and G2/M phases in HEK-293T-REx cells (Li et al., 2019).

Conclusion and Perspectives

Ca2+ signaling is involved in almost all cellular activities in organisms. As a major route of Ca2+ entry in mammalian cells for replenishing the depleted intracellular Ca2+ store, SOCE regulates a diverse array of biological processes. Accumulating evidence has shown that STIM/ORAI-mediated SOCE is excessive in cancer tissues, and it is becoming clear that augmented SOCE promotes the malignant behavior of cancer cells, including tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Therefore, SOCE could be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of cancer.

As we summarized above, multiple compounds targeting SOCE have been developed and their efficiency in the inhibition of proliferation and migration of cancer cells has been evaluated. However, rare SOCE inhibitors have been approved for clinical use in cancer treatment due to their poor selectivity, which urgently needs to addressed. In addition, as SOCE is not the only channel for Ca2+ entry, cells could adopt other ways to obtain sufficient Ca2+ even after complete SOCE inhibition. Under this condition, drug combinations could be considered. Furthermore, due to the universal roles of Ca2+ signaling in cells, the cytotoxicity of SOCE inhibitors on normal cells and some anticancer immune cell inhibitors should also be considered in clinical anticancer applications. Developing SOCE inhibitors that could specifically target tumor tissues in certain circumstances is a hopeful therapeutic orientation toward cancer in the future.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972745, 81872238, and 81572361), Ten Thousand Plan Youth Talent Support Program of Zhejiang Province (ZJWR0108009), and Zhejiang Medical Innovative Discipline Construction Project-2016.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Amcheslavsky A., Safrina O., Cahalan M. D. (2014). State-Dependent Block of Orai3 TM1 and TM3 Cysteine Mutants: Insights Into 2-APB Activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 143 (5), 621–631. 10.1085/jgp.201411171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amcheslavsky A., Wood M. L., Yeromin A. V., Parker I., Freites J. A., Tobias D. J., et al. (2015). Molecular Biophysics of Orai Store-Operated Ca2+ Channels. Biophys. J. 108 (2), 237–246. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.3473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Montaño J.-A., Gibson W. J., Young J. M. (1998). SK&F 96365 (1-{β-[3-(4-Methoxyphenyl)propoxy]- 4-Methoxyphenylethyl}-1H-Imidazole Hydrochloride) Stimulates Phosphoinositide Hydrolysis in Human U373 MG Astrocytoma Cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 56 (8), 1023–1027. 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00125-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmole I., Duffy S. M., Leyland M. L., Morrison V. S., Begg M., Bradding P. (2012). CRACM/Orai Ion Channel Expression and Function in Human Lung Mast Cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129 (6), 1628–1635. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimi I., Bong A. H., Poo G. X. H., Armitage K., Lok D., Roberts-Thomson S. J., et al. (2018). Pharmacological Inhibition of Store-Operated Calcium Entry in MDA-MB-468 Basal A Breast Cancer Cells: Consequences on Calcium Signalling, Cell Migration and Proliferation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75 (24), 4525–4537. 10.1007/s00018-018-2904-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer K. S., Figg W. D., Hamilton J. M., Jones E. C., Premkumar A., Steinberg S. M., et al. (1999). A Pharmacokinetically Guided Phase II Study of Carboxyamido-Triazole in Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 5 (9), 2324–2329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B. D., Alvarez U., Hruska K. A. (2001). Receptor-Operated Osteoclast Calcium Sensing. Endocrinology 142 (5), 1968–1974. 10.1210/endo.142.5.8125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittremieux M., Gerasimenko J. V., Schuermans M., Luyten T., Stapleton E., Alzayady K. J., et al. (2017). DPB162-AE, An Inhibitor of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry, Can Deplete the Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Store. Cell Calcium 62, 60–70. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomben V. C., Sontheimer H. W. (2008). Inhibition of Transient Receptor Potential Canonical Channels Impairs Cytokinesis in Human Malignant Gliomas. Cell Prolif. 41 (1), 98–121. 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00504.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomben V. C., Sontheimer H. (2010). Disruption of Transient Receptor Potential Canonical Channel 1 Causes Incomplete Cytokinesis and Slows the Growth of Human Malignant Gliomas. Glia 58 (10), 1145–1156. 10.1002/glia.20994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandman O., Liou J., Park W. S., Meyer T. (2007). STIM2 is a Feedback Regulator that Stabilizes Basal Cytosolic and Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Levels. Cell 131 (7), 1327–1339. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello O. A., Schilling W. P. (1993). Vectorial Ca2+ Flux From the Extracellular Space to the Endoplasmic Reticulum via a Restricted Cytoplasmic Compartment Regulates Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate-Stimulated Ca2+ Release From Internal Stores in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Biochem. J. 295 (Pt 2), 357–366. 10.1042/bj2950357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai R., Ding X., Zhou K., Shi Y., Ge R., Ren G., et al. (2009). Blockade of TRPC6 Channels Induced G2/M Phase Arrest and Suppressed Growth in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. Int. J. Cancer 125 (10), 2281–2287. 10.1002/ijc.24551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.-H., Cheng Y.-C., Tsai W.-C., Tsao M.-J., Chen Y. (2018). Pyr3 Induces Apoptosis and Inhibits Migration in Human Glioblastoma Cells. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 48 (4), 1694–1702. 10.1159/000492293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet S., Jarvis L., Chevallet M., Shrestha N., Groschner K., Bouron A. (2016). Pharmacological Characterization of the Native Store-Operated Calcium Channels of Cortical Neurons From Embryonic Mouse Brain. Front. Pharmacol. 7, 486. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Sanderson M. J. (2017). Store-Operated Calcium Entry is Required for Sustained Contraction and Ca2+ Oscillations of Airway Smooth Muscle. J. Physiol. 595 (10), 3203–3218. 10.1113/JP272694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-P., Luan Y., You C.-X., Chen X.-H., Luo R.-C., Li R. (2010). TRPM7 Regulates the Migration of Human Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cell by Mediating Ca2+ Influx. Cell Calcium 47 (5), 425–432. 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-F., Chiu W.-T., Chen Y.-T., Lin P.-Y., Huang H.-J., Chou C.-Y., et al. (2011). Calcium Store Sensor Stromal-Interaction Molecule 1-Dependent Signaling Plays an Important Role in Cervical Cancer Growth, Migration, and Angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108 (37), 15225–15230. 10.1073/pnas.1103315108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Panicker S., Lau K.-Y., Apparsundaram S., Patel V. A., Chen S.-L., et al. (2013). Characterization of a Novel CRAC Inhibitor that Potently Blocks Human T Cell Activation and Effector Functions. Mol. Immunol. 54 (3-4), 355–367. 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-T., Chen Y.-F., Chiu W.-T., Wang Y.-K., Chang H.-C., Shen M.-R. (2013). The ER Ca2+ Sensor STIM1 Regulates Actomyosin Contractility of Migratory Cells. J. Cell Sci. 126 (Pt 5), 1260–1267. 10.1242/jcs.121129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chokshi R., Fruasaha P., Kozak J. A. (2012). 2-Aminoethyl Diphenyl Borinate (2-APB) Inhibits TRPM7 Channels through an Intracellular Acidification Mechanism. Channels 6 (5), 362–369. 10.4161/chan.21628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S. C., McDonald T. V., Gardner P. (1994). Inhibition by SK&F 96365 of Ca2+ Current, IL-2 Production and Activation in T Lymphocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 113 (3), 861–868. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17072.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M.-K., Lee H., Mizuno A., Suzuki M., Caterina M. J. (2004). 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate Activates and Sensitizes the Heat-Gated Ion Channel TRPV3. J. Neurosci. 24 (22), 5177–5182. 10.1523/jneurosci.0934-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton C. K., Zhu M. X. (2007). 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate as a Common Activator of TRPV1, TRPV2, and TRPV3 Channels. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 179, 173–187. 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrado C., Raimondo S., Flugy A. M., Fontana S., Santoro A., Stassi G., et al. (2011). Carboxyamidotriazole Inhibits Cell Growth of Imatinib-Resistant Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia Cells Including T315I Bcr-Abl Mutant by a Redox-Mediated Mechanism. Cancer Lett. 300 (2), 205–214. 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. H., Hussell S., Søndergaard H., Roepstorff K., Bui J.-V., Deer J. R., et al. (2013). Antibody-Mediated Targeting of the Orai1 Calcium Channel Inhibits T Cell Function. PLoS One 8 (12), e82944. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C., Merritt R., Fu L., Pan Z. (2017). Targeting Calcium Signaling in Cancer Therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 7 (1), 3–17. 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C., Chang Y., Zhang X., Choi S., Tran H., Penmetsa K. V., et al. (2018). Targeting Orai1-Mediated Store-Operated Calcium Entry by RP4010 for Anti-Tumor Activity in Esophagus Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 432, 169–179. 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dago C., Maux P., Roisnel T., Brigaudeau C., Bekro Y.-A., Mignen O., et al. (2018). Preliminary Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) of a Novel Series of Pyrazole SKF-96365 Analogues as Potential Store-Operated Calcium Entry (SOCE) Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (3), 856. 10.3390/ijms19030856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart A. E., Worth D. C., Muir G., Chandra A., Morris J. D., McKee C., et al. (2017). The Drebrin/EB3 Pathway Drives Invasive Activity in Prostate Cancer. Oncogene 36 (29), 4111–4123. 10.1038/onc.2017.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M. (2018). Carboxyamidotriazole Orotate in Glioblastoma. Lancet Oncol. 19 (6), e292. 10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30347-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Boyles R. R., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr. (2008). Complex Actions of 2-Aminoethyldiphenyl Borate on Store-Operated Calcium Entry. J. Biol. Chem. 283 (28), 19265–19273. 10.1074/jbc.M801535200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derler I., Schindl R., Fritsch R., Heftberger P., Riedl M. C., Begg M., et al. (2013). The Action of Selective CRAC Channel Blockers is Affected by the Orai Pore Geometry. Cell Calcium 53 (2), 139–151. 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sabatino A., Rovedatti L., Kaur R., Spencer J. P., Brown J. T., Morisset V. D., et al. (2009). Targeting Gut T Cell Ca2+ Release-Activated Ca2+ Channels Inhibits T Cell Cytokine Production and T-Box Transcription Factor T-Bet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Immunol. 183 (5), 3454–3462. 10.4049/jimmunol.0802887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., He Z., Zhou K., Cheng J., Yao H., Lu D., et al. (2010). Essential Role of TRPC6 Channels in G2/M Phase Transition and Development of Human Glioma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 102 (14), 1052–1068. 10.1093/jnci/djq217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrydneva Y., Williams R. L., Blackmore P. F. (2010). Diethylstilbestrol and Other Nonsteroidal Estrogens: Novel Class of Store-Operated Calcium Channel Modulators. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 55 (5), 522–530. 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181d64b33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni S., Laforenza U., Bonetti E., Lodola F., Bottino C., Berra-Romani R., et al. (2011). Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Stimulates Endothelial colony Forming Cells Proliferation and Tubulogenesis by Inducing Oscillations in Intracellular Ca2+ Concentration. Stem Cells 29 (11), 1898–1907. 10.1002/stem.734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enfissi A., Prigent S., Colosetti P., Capiod T. (2004). The Blocking of Capacitative Calcium Entry by 2-Aminoethyl Diphenylborate (2-APB) and Carboxyamidotriazole (CAI) Inhibits Proliferation in Hep G2 and Huh-7 Human Hepatoma Cells. Cell Calcium 36 (6), 459–467. 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figg W. D., Cole K. A., Reed E., Steinberg S. M., Piscitelli S. C., Davis P. A., et al. (1995). Pharmacokinetics of Orally Administered Carboxyamido-Triazole, an Inhibitor of Calcium-Mediated Signal Transduction. Clin. Cancer Res. 1 (8), 797–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzius D., Hoth M., Penner R. (1994). Non-Specific Effects of Calcium Entry Antagonists in Mast Cells. Pflugers Arch. 428 (5–6), 433–438. 10.1007/bf00374562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng S., Gao Y.-d., Yang J., Zou J.-j., Guo W. (2012). Potential Role of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry in Th2 Response Induced by Histamine in Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 12 (2), 358–367. 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gericke M., Oike M., Droogmans G., Nilius B. (1994). Inhibition of Capacitative Ca2+ Entry by a Cl− Channel Blocker in Human Endothelial Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Mol. Pharmacol. 269 (3), 381–384. 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90046-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giambelluca M. S., Gende O. A. (2007). Selective Inhibition of Calcium Influx by 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 565 (1–3), 1–6. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon J., Tu P., Bouron A. (2010). Store-Depletion and Hyperforin Activate Distinct Types of Ca2+-Conducting Channels in Cortical Neurons. Cell Calcium 47 (6), 538–543. 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswamee P., Pounardjian T., Giovannucci D. R. (2018). Arachidonic Acid-Induced Ca2+ Entry and Migration in a Neuroendocrine Cancer Cell Line. Cancer Cell Int. 18, 30. 10.1186/s12935-018-0529-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto J.-I., Suzuki A. Z., Ozaki S., Matsumoto N., Nakamura T., Ebisui E., et al. (2010). Two Novel 2-Aminoethyl Diphenylborinate (2-APB) Analogues Differentially Activate and Inhibit Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry via STIM Proteins. Cell Calcium 47 (1), 1–10. 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper J. L., Camerini-Otero C. S., Li A.-H., Kim S.-A., Jacobson K. A., Daly J. W. (2003). Dihydropyridines as Inhibitors of Capacitative Calcium Entry in Leukemic HL-60 Cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 65 (3), 329–338. 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01488-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.-P., Hewavitharana T., Soboloff J., Spassova M. A., Gill D. L. (2005). A Functional Link Between Store-Operated and TRPC Channels Revealed by the 3,5-Bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazole Derivative, BTP2. J. Biol. Chem. 280 (12), 10997–11006. 10.1074/jbc.M411797200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B., Liu F., Ruan J., Li A., Chen J., Li R., et al. (2012). Silencing TRPC1 Expression Inhibits Invasion of CNE2 Nasopharyngeal Tumor Cells. Oncol. Rep. 27 (5), 1548–1554. 10.3892/or.2012.1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendron E., Wang X., Zhou Y., Cai X., Goto J.-I., Mikoshiba K., et al. (2014). Potent Functional Uncoupling Between STIM1 and Orai1 by Dimeric 2-Aminodiphenyl Borinate Analogs. Cell Calcium 56 (6), 482–492. 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman S. L., Mandrekar S. J., Bot B., DeMatteo R. P., Perez E. A., Ballman K. V., et al. (2010). Evaluation of the Value of Attribution in the Interpretation of Adverse Event Data: A North Central Cancer Treatment Group and American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Investigation. J. Clin. Oncol. 28 (18), 3002–3007. 10.1200/jco.2009.27.4282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Rao A. (2010). Molecular Basis of Calcium Signaling in Lymphocytes: STIM and ORAI. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 491–533. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H.-Z., Gu Q., Wang C., Colton C. K., Tang J., Kinoshita-Kawada M., et al. (2004). 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate is a Common Activator of TRPV1, TRPV2, and TRPV3. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (34), 35741–35748. 10.1074/jbc.M404164200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.-K., Lin Y.-H., Chang H.-A., Lai Y.-S., Chen Y.-C., Huang S.-C., et al. (2020). Chemoresistant Ovarian Cancer Enhances its Migration Abilities by Increasing Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry-Mediated Turnover of Focal Adhesions. J. Biomed. Sci. 27 (1), 36. 10.1186/s12929-020-00630-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupe D. J., Boltz R., Cohen C. J., Felix J., Ham E., Miller D., et al. (1991). The Inhibition of Receptor-Mediated and Voltage-Dependent Calcium Entry by the Antiproliferative L-651,582. J. Biol. Chem. 266 (16), 10136–10142. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)99200-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M. M., Kotz H., Minasian L., Premkumar A., Sarosy G., Reed E., et al. (2003). Phase II Trial of Carboxyamidotriazole in Patients With Relapsed Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 21 (23), 4356–4363. 10.1200/jco.2003.04.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa J., Ohga K., Yoshino T., Takezawa R., Ichikawa A., Kubota H., et al. (2003). A Pyrazole Derivative, YM-58483, Potently Inhibits Store-Operated Sustained Ca2+ Influx and IL-2 Production in T Lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 170 (9), 4441–4449. 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamuro Y., Miwa S., Zhang X.-F., Minowa T., Enoki T., Okamoto Y., et al. (1999). Activation of Three Types of Voltage-Independent Ca2+ Channel in A7r5 Cells by Endothelin-1 as Revealed by a Novel Ca2+channel Blocker LOE 908. Br. J. Pharmacol. 126 (5), 1107–1114. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs W., Mikkelsen T., Smith R., Nelson K., Rosenblum M. L., Kohn E. C. (1997). Inhibitory Effects of CAI in Glioblastoma Growth and Invasion. J. Neurooncol. 32 (2), 93–101. 10.1023/a:1005777711567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jairaman A., Prakriya M. (2013). Molecular Pharmacology of Store-Operated CRAC Channels. Channels 7 (5), 402–414. 10.4161/chan.25292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Z., Sui X., Yao J., Xie J., Jiang L., Zhou Y., et al. (2016). SKF-96365 Activates Cytoprotective Autophagy to Delay Apoptosis in Colorectal Cancer Cells Through Inhibition of the Calcium/CaMKIIγ/AKT-Mediated Pathway. Cancer Lett. 372 (2), 226–238. 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju R., Wu D., Guo L., Li J., Ye C., Zhang D. (2012). Inhibition of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Tumour Associated Macrophages is a Potential Anti-Cancer Mechanism of Carboxyamidotriazole. Eur. J. Cancer 48 (7), 1085–1095. 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko K., Satoh K., Masamune A., Satoh A., Shimosegawa T. (2002). Myosin Light Chain Kinase Inhibitors Can Block Invasion and Adhesion of Human Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines. Pancreas 24 (1), 34–41. 10.1097/00006676-200201000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappel S., Kilch T., Baur R., Lochner M., Peinelt C. (2020). The Number and Position of Orai3 Units Within Heteromeric Store-Operated Ca2+ Channels Alter the Pharmacology of ICRAC. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (7), 2458. 10.3390/ijms21072458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan H. Y., Mpilla G. B., Sexton R., Viswanadha S., Penmetsa K. V., Aboukameel A., et al. (2020). Calcium Release-Activated Calcium (CRAC) Channel Inhibition Suppresses Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cell Proliferation and Patient-Derived Tumor Growth. Cancers 12 (3), 750. 10.3390/cancers12030750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-H., Lkhagvadorj S., Lee M.-R., Hwang K.-H., Chung H. C., Jung J. H., et al. (2014). Orai1 and STIM1 are Critical for Cell Migration and Proliferation of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 448 (1), 76–82. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.04.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyonaka S., Kato K., Nishida M., Mio K., Numaga T., Sawaguchi Y., et al. (2009). Selective and Direct Inhibition of TRPC3 Channels Underlies Biological Activities of a Pyrazole Compound. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106 (13), 5400–5405. 10.1073/pnas.0808793106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn E. C., Liotta L. A. (1990). L651582: A Novel Antiproliferative and Antimetastasis Agent. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 82 (1), 54–61. 10.1093/jnci/82.1.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn E. C., Sandeen M. A., Liotta L. A. (1992). In Vivo Efficacy of a Novel Inhibitor of Selected Signal Transduction Pathways Including Calcium, Arachidonate, and Inositol Phosphates. Cancer Res. 52 (11), 3208–3212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn E. C., Felder C. C., Jacobs W., Holmes K. A., Day A., Freer R., et al. (1994). Structure-Function Analysis of Signal and Growth Inhibition by Carboxyamido-Triazole, CAI. Cancer Res. 54 (4), 935–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn E. C., Reed E., Sarosy G., Christian M., Link C. J., Cole K., et al. (1996). Clinical Investigation of a Cytostatic Calcium Influx Inhibitor in Patients With Refractory Cancers. Cancer Res. 56 (3), 569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratskyi A., Yassine M., Slomianny C., Kondratska K., Gordienko D., Dewailly E., et al. (2014). Identification of ML-9 as a Lysosomotropic Agent Targeting Autophagy and Cell Death. Cell Death Dis. 5 (4), e1193. 10.1038/cddis.2014.156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs G., Montalbetti N., Simonin A., Danko T., Balazs B., Zsembery A., et al. (2012). Inhibition of the Human Epithelial Calcium Channel TRPV6 by 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate (2-APB). Cell Calcium 52 (6), 468–480. 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Morales J. L., Mottram L. F., Iyer A., Peterson B. R., August A. (2011). Structural Requirements for the Inhibition of Calcium Mobilization and Mast Cell Activation by the Pyrazole Derivative BTP2. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 43 (8), 1228–1239. 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. S., Sayeed M. M., Wurster R. D. (1993). Inhibition of Human Brain Tumor Cell Growth by a Receptor-Operated Ca2+ Channel Blocker. Cancer Lett. 72 (1–2), 77–81. 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90014-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng T.-D., Li M.-H., Shen J.-F., Liu M.-L., Li X.-B., Sun H.-W., et al. (2015). Suppression of TRPM7 Inhibits Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Malignant Human Glioma Cells. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 21 (3), 252–261. 10.1111/cns.12354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. H., Spence K. T., Dargis P. G., Christian E. P. (2000). Properties of Ca(2+) Release-Activated Ca(2+) Channel Block by 5-Nitro-2-(3-Phenylpropylamino)-Benzoic Acid in Jurkat Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 394 (2–3), 171–179. 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00144-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Jiang J., Yue L. (2006). Functional Characterization of Homo- and Heteromeric Channel Kinases TRPM6 and TRPM7. J. Gen. Physiol. 127 (5), 525–537. 10.1085/jgp.200609502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang Q., Lin W., Wang B. (2009). Regulation of Ovarian Cancer Cell Adhesion and Invasion by Chloride Channels. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 19 (4), 526–530. 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a3d6d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., McKeown L., Ojelabi O., Stacey M., Foster R., O'Regan D., et al. (2011). Nanomolar Potency and Selectivity of a Ca2+ Release-Activated Ca2+ Channel Inhibitor Against Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry and Migration of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 164 (2), 382–393. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01368.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Rubaiy H. N., Chen G. L., Hallett T., Zaibi N., Zeng B., et al. (2019). Mibefradil, a T‐Type Ca 2+ Channel Blocker Also Blocks Orai Channels by Action at the Extracellular Surface. Br. J. Pharmacol. 176 (19), 3845–3856. 10.1111/bph.14788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievremont J.-P., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr. (2005). Mechanism of Inhibition of TRPC Cation Channels by 2-Aminoethoxydiphenylborane. Mol. Pharmacol. 68 (3), 758–762. 10.1124/mol.105.012856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F.-F., Elliott R., Colombero A., Gaida K., Kelley L., Moksa A., et al. (2013). Generation and Characterization of Fully Human Monoclonal Antibodies Against Human Orai1 for Autoimmune Disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 345 (2), 225–238. 10.1124/jpet.112.202788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J., Kim M. L., Do Heo W., Jones J. T., Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E., Jr., et al. (2005). STIM is a Ca2+ Sensor Essential for Ca2+-Store-Depletion-Triggered Ca2+ Influx. Curr. Biol. 15 (13), 1235–1241. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis A., Peinelt C., Beck A., Parvez S., Monteilh-Zoller M., Fleig A., et al. (2007). CRACM1, CRACM2, and CRACM3 are Store-Operated Ca2+ Channels With Distinct Functional Properties. Curr. Biol. 17 (9), 794–800. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Hughes J. D., Rollins S., Chen B., Perkins E. (2011). Calcium Entry via ORAI1 Regulates Glioblastoma Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 91 (3), 753–760. 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Li H., He L., Xiang Y., Tian C., Li C., et al. (2019). Discovery of Small-Molecule Inhibitors of the HSP90-Calcineurin-NFAT Pathway Against Glioblastoma. Cel Chem. Biol. 26 (3), 352–365. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Dilger J. P., Lin J. (2020). The Role of Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 7 (TRPM7) in Cell Viability: A Potential Target to Suppress Breast Cancer Cell Cycle. Cancers 12 (1), 131. 10.3390/cancers12010131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodola F., Laforenza U., Bonetti E., Lim D., Dragoni S., Bottino C., et al. (2012). Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry is Remodelled and Controls In Vitro Angiogenesis in Endothelial Progenitor Cells Isolated From Tumoral Patients. PLoS One 7 (9), e42541. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]