Abstract

Purpose:

We sought to determine preferences of biobank participants whose samples were tested for clinically actionable variants but did not respond to an initial invitation to receive results.

Methods:

We re-contacted a subsample of participants in the Kaiser Permanente Washington/ University of Washington site of the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE3) Network. The subsample had provided broad consent for their samples to be used for research but had not responded to one initial mailed invitation to receive their results. We sent a letter from the principal investigators with phone outreach. If no contact was made, we sent a certified letter stating our assumption that participant had actively refused. We collected reasons for declining.

Results:

We re-contacted 123 participants. Response rate was 70.7% (n=87). Of these, 62 (71.3%) declined the offer of returned results and 25 (28.7%) consented. The most common reasons provided for refusal included not wanting to know (n=22) and concerns about insurability (n=28).

Conclusion:

Efforts to re-contact biobank participants can yield high response. Though active refusal upon recontact was common, our data do not support assuming initial nonresponse to be refusal. Future research can work toward best practices for re-consenting, especially when clinically actionable results are possible.

Introduction

Testing of biobank samples can yield clinically actionable results. Best practices for consent procedures for returning genomic test results to biobank participants are evolving. This study describes an ad hoc re-contact study of biobank participants who provided broad consent for use of samples but who did not respond to an initial invitation to receive clinically actionable results.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study was conducted at the Kaiser Permanente Washington/ University of Washington site of the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) 3 Network.1,2 Site participants were part of the Northwest Institute for Genomic Medicine biorepository (also known as NWIGM). All were Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA) members recruited between 2008 and 2017. By design, the sample was enriched with people of Asian ancestry and people with a personal history of either colorectal cancer or colon polyps. All initial consent and re-contact procedures were approved by the KPWA IRB.

Initial consent procedures

Membership in the research biobank used broad consent procedures, where participants provided broad consent for the collection and long-term storage of DNA samples and associated phenotypic data, and for their samples to be used for genetic research.3,4 The broad consent did not include return of actionable results to participants. Under this broad consent, in 2017–2018 we tested CLIA-compliant samples against a sequencing panel for 67 gene-disease pairs with known or putative clinical actionability, including the 58 of 59 considered actionable by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.5 Participants (n=2400) were then contacted via mailed letter and asked to provide written consent by return mail to receive the results of this clinical grade genomic data. Consent included both receiving results and placement of the results in the participant’s medical record at Kaiser Permanente WA. Non-responders were mailed a follow-up letter and consent form; no other follow-up was attempted.

Re-contact procedures

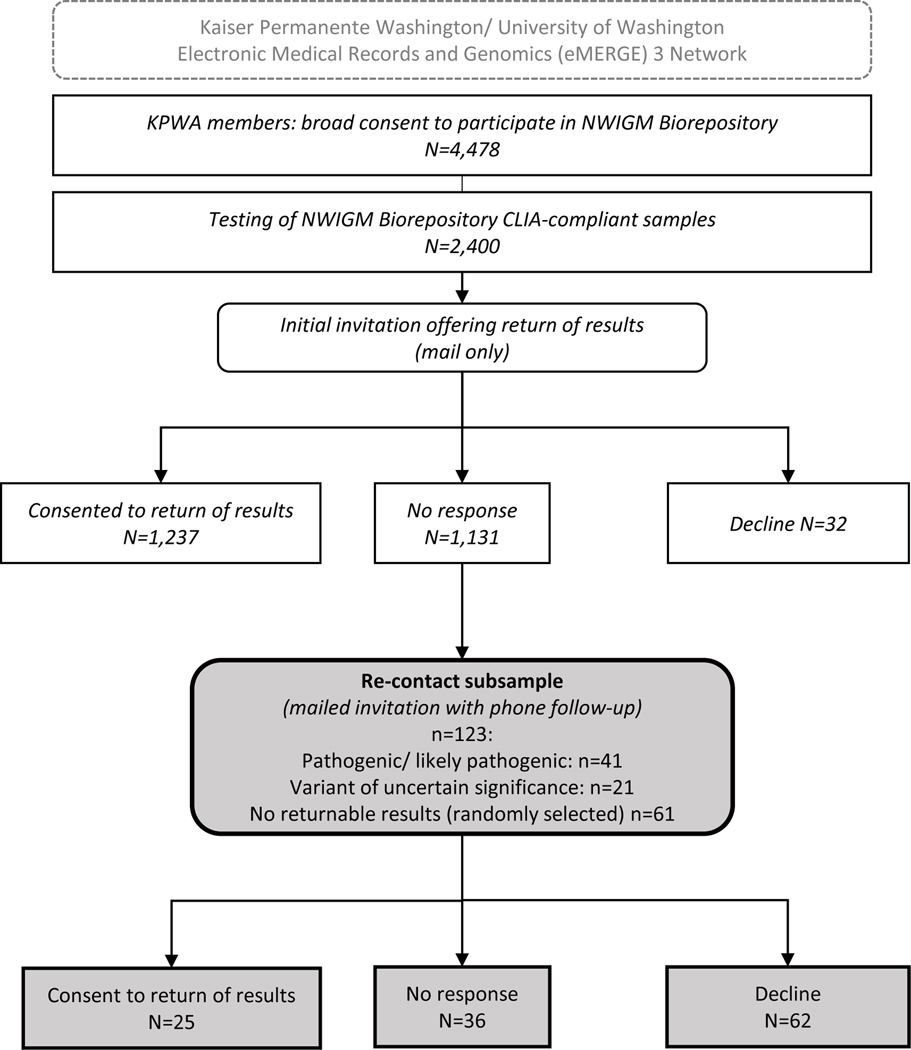

Due to incomplete response (52.9%) to the initial invitation, and since clinically actionable results had been detected during testing, in 2019 we re-contacted a subsample of biobank participants who had not responded to our initial invitation. The subsample (n=123) intentionally included all 41 people whose sequencing found actionable pathogenic or likely pathogenic findings and all 21 people whose results indicated variants of uncertain significance in CRC-associated genes. We also included a random sample of people (n=61) with no actionable results. Individuals with no actionable findings were included so that neither the participant nor the study staff re-contacting them could infer whether a participant had an actionable or VUS finding (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study overview.

Re-contact procedures included a mailed letter re-inviting the participant to receive results, followed by a call from the study team with up to 3 additional phone attempts. We used current contact information listed in the medical record to contact participants. Study team members conducting the re-contact were blinded to participants’ test results. During phone follow up, we used field notes to summarize reasons for refusal when offered. Mail and phone were the only IRB-approved methods for contact with participants and were typical and expected communication methods as part of biobank participation.

Communication points in the re-contact letter included a reminder of biobank participation, a description of the eMERGE study, and an invitation to receive results with placement of results in their KP electronic health record. During phone contact, the study team invited questions about the study. If all repeated attempts to reach the person were unsuccessful, we sent a certified letter stating our assumption of their refusal. Study team contact information was provided on all written communications.

Analysis

We compared the demographics of the initial sample, the subset of people who responded to the initial invitation, and the re-contact subsample using previously collected eMERGE study records. We calculated responses to both rounds of consent invitations. During re-contact we documented consent disposition for each participant as either active consent (returned written consent); active refusal (provided written or verbal consent); or no response. We qualitatively summarized the primary reason for each participant declining to consent.

Results

Participants were mean age 61 years at the initial consent invitation, which occurred between November 2016 and February 2017. Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar in the initially consented and re-contacted groups (Table 1), except participants in the re-contact sample were less likely to report white race and more likely to have a personal history of either colorectal cancer or colorectal polyps.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Initial sample (2017–2018) | % | Re-contact subsample (2019) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2,400 | 123 | ||

| Age in years, Mean (range) | 61 (29–101) | 59 (33–38) | ||

| Female | 1436 | 60% | 75 | 61% |

| Race (self-reported) | ||||

| AI/AN | 23 | 1.0% | 1 | 0.1% |

| Asian | 970 | 41.0% | 53 | 43.0% |

| Hawaiian/ PI | 9 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Black/ AA | 49 | 2.0% | 6 | 4.8% |

| White | 1283 | 53.0% | 59 | 48.0% |

| Multi-ethnic | 35 | 1.5% | 2 | 1.5% |

| Unknown | 31 | 1.3% | 2 | 1.5% |

| Hispanic | 65 | 3.0% | 3 | 2.5% |

| CRC diagnosis | 533 | 22.0% | 46 | 38.0% |

| Colorectal polyps | 812 | 34.0% | 51 | 41.0% |

| No CRC diagnosis or polyps | 1,055 | 44.0% | 26 | 21.0% |

| Responded to invitation | 1269 | 52.9% | 87 | 70.7% |

| Consent | % of respondents | % of respondents | ||

| Consented to return of results | 1237 | 97.5% | 25 | 28.7% |

| Declined return of results | 32 | 2.5% | 62 | 71.3% |

In response to the initial invitation, 1269 (52.9%) responded; 1237 participants actively consented to return of results and 32 provided active written refusal. Nearly half (47.3%) did not return any written response.

Re-contact letters were sent approximately three years later, between September 2019 and January 2020. Response rate to the re-contact sample of 123 people was higher; 87 people (70.7%) responded. Of these 87, the majority (n=62, 71.3%) declined the offer of returned results. In total, 25 of the 87 respondents (28.7%) provided written consent for return (Table 2). Nine subsequently had pathogenic or likely pathogenic results returned. Age, race/ethnicity, and colorectal cancer status appeared similar across the consenting, declining, and unable to reach groups (Supplemental materials).

No letters or certified letters were returned. The most common reasons for refusal (n=62) included not wanting to know (n=22) and concerns about insurability (n=28). A less commonly reported reason was concerns about privacy (n=12).

Discussion

Before returning clinically actionable findings to biobank or research participants, clear understanding of participant preferences for receiving actionable findings is both of critical importance and difficult to attain.6–8 Our results indicate several potentially valuable findings.

First, our efforts to re-contact initially nonresponsive participants yielded high response and resulted in more complete knowledge of participant preferences about return of genomic sequencing results.

Second, our results suggest that nonresponse to a consent invitation should not be construed as refusal. While half (50.3%) of re-contacted respondents actively refused return of results, a substantial minority (20.1%) consented to receive results. Thus, despite reports that a majority of sequencing recipients hypothetically prefer to receive all possible results,9–11 our findings suggest much more mixed preferences when offered results in a real research setting. Further, they reveal continuing participant concerns about insurance discrimination and preferences not to know results in a population who had previously provided broad consent and a context where clinically actionable results were possible.

Third, these results highlight the evolving nature of best practices about models of consent for return of results under a broad consent framework. We adopted a staged consent model in this study,6 where broad consent was followed with consent to receive specific results. However, high nonresponse rates and resource constraints complicated the full realization of this model. Further, the study team struggled with incomplete knowledge of participant preferences, particularly since we were in possession of clinically actionable information. We also re-contacted only a subsample of initially nonresponding participants, highlighting resource constraints associated with staged consent procedures. 12

Return of genomic results remains a murky area for clinicians, scientists and the public we serve. Our findings emphasize the importance of consent procedures that allow both meaningful assessment of participant preferences for return of results to biobank participants, particularly clinically actionable results. Further research can shed light on best practices for inviting informed consent, including methods for outreach besides mail or phone, broad versus specific consent, and procedures for assigning disposition to unanswered invitations to provide consent. This study highlights the practical limitations of staged consent models and the importance of consent procedures that accurately reflect participant preferences for receiving results at all stages of biobank participation.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data is available upon request by contacting the study team.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

5U01HG008657 NHGRI. The funder had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

ETHICS DECLARATION

All activities reported were reviewed and approved by the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants as required by the IRB.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST NOTIFICATION PAGE

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCarty CA, Chisholm RL, Chute CG, et al. The eMERGE Network: a consortium of biorepositories linked to electronic medical records data for conducting genomic studies. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.eMERGE Consortium. Harmonizing Clinical Sequencing and Interpretation for the eMERGE III Network. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105(3):588–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludman EJ, Fullerton SM, Spangler L, et al. Glad you asked: participants’ opinions of re-consent for dbGap data submission. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2010;5(3):9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Bares JM, Jarvik GP, Larson EB, Burke W. Informed consent in genome-scale research: What do prospective participants think? AJOB Prim Res. 2012;3(3):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15(7):565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appelbaum PS, Parens E, Waldman CR, et al. Models of consent to return of incidental findings in genomic research. Hastings Cent Rep. 2014;44(4):22–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke W, Beskow LM, Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Brelsford K. Informed consent in translational genomics: Insufficient without trustworthy governance. J Law Med Ethics. 2018;46(1):79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackley MP, Fletcher B, Parker M, Watkins H, Ormondroyd E. Stakeholder views on secondary findings in whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Genet Med. 2017;19(3):283–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bijlsma R, Wouters R, Wessels H, et al. Preferences to receive unsolicited findings of germline genome sequencing in a large population of patients with cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;5(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middleton A, Morley KI, Bragin E, et al. Attitudes of nearly 7000 health professionals, genomic researchers and publics toward the return of incidental results from sequencing research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(1):21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godino L, Varesco L, Bruno W, et al. Preferences of Italian patients for return of secondary findings from clinical genome/exome sequencing. J Genet Couns. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appelbaum PS, Fyer A, Klitzman RL, et al. Researchers’ views on informed consent for return of secondary results in genomic research. Genet Med. 2015;17(8):644–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request by contacting the study team.