Keywords: α-cell, clearance, glucagon, impaired glucose tolerance, prediabetes

Abstract

Impaired glucose tolerance arises out of impaired postprandial insulin secretion and delayed suppression of glucagon. These defects occur early and independently in the pathogenesis of prediabetes. Quantification of the contribution of α-cell dysfunction to glucose tolerance has been lacking because knowledge of glucagon kinetics in humans is limited. Therefore, in a series of experiments examining the interaction of glucagon suppression with insulin secretion we studied 51 nondiabetic subjects (age = 54 ± 13 yr, BMI = 28 ± 4 kg/m2). Glucose was infused to mimic the systemic appearance of an oral challenge. Somatostatin was used to inhibit endogenous hormone secretion. 120 min after the start of the experiment, glucagon was infused at 0.65 ng/kg/min. The rise in glucagon concentrations was used to estimate its kinetic parameters [volume of distribution (Vd), half-life (t1/2), and clearance rate (CL)]. A single-exponential model provided the best fit for the data, and individualized kinetic parameters were estimated: Vd = 8.2 ± 2.7 L, t1/2 = 4 ± 1.1 min, CL = 1.4 ± 0.33 L/min. Stepwise linear regression was used to correlate Vd with BMI and sex (R2adj = 0.44), whereas CL similarly correlated with lean body mass or BSA (both R2 = 0.28). This enabled the development of a population-based model using anthropometric characteristics to predict Vd and CL. These data demonstrate that it is feasible to derive glucagon kinetic parameters from anthropometric characteristics, thereby enabling quantitation of the rate of glucagon appearance in the systemic circulation in large populations.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY State-of-the-art measurement of insulin secretion in humans is accomplished by deconvolution of peripheral C-peptide concentrations using population-derived parameters of C-peptide kinetics. In contrast, knowledge of the kinetic parameters of glucagon in humans is lacking so that measurement of glucagon secretion to date is largely qualitative. This series of experiments enabled measurement of glucagon kinetics in 51 subjects, and subsequently, stepwise linear regression was used to correlate these parameters with anthropometric characteristics. This enabled the development of a population-based model using anthropometric characteristics to predict the volume of distribution and the rate of clearance. This is a necessary first step in the development of a model to quantitate of glucagon secretion and action (and its contribution to glucose tolerance) in large populations.

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) has been characterized as a bi-hormonal disease with defective and delayed insulin secretion interacting with impaired glucagon suppression to cause postprandial hyperglycemia (1). To date, examination of the pathogenesis underlying the progression from normal glucose tolerance to overt type 2 diabetes has focused overwhelmingly on β-cell dysfunction and the relative contributions of insulin secretion and of insulin action (2). The ability to quantify β-cell function using the minimal model enables comparison of the abnormalities present in different subgroups of glucose tolerance and allows quantification of the effects of various interventions on glucose metabolism (3).

It has become increasingly apparent that α-cell dysfunction, at least to some degree, occurs independently of β-cell dysfunction (4, 5). Furthermore, the association of α-cell dysfunction with genetic predisposition to T2DM would suggest that it is an early contributor to the development of T2DM (6, 7). Given that α-cell and β-cell functions have opposite effects on glucose metabolism, assessment of global islet function in a given individual is likely to better quantify the degree of metabolic dysfunction and risk of progression to T2DM. Quantification of α-cell function during an oral or intravenous challenge would allow comparison of α-cell function among individuals and, perhaps, help to better understand the evolution of prediabetes.

At the present time, the optimal method of quantifying insulin secretion utilizes C-peptide. This is because despite insulin and C-peptide being secreted in a 1:1 ratio into the portal circulation, C-peptide, unlike insulin, does not undergo hepatic extraction (3). However, since C-peptide has a relatively long half-life in the circulation, knowledge of its rate of clearance is required to deconvolve insulin secretion rates from C-peptide concentrations. To avoid the impracticality of measuring C-peptide clearance in every individual undergoing β-cell function testing, Van Cauter et al. (8) derived standard kinetic parameters from the individual measurement of C-peptide clearance in a relatively large population. This approach has been independently validated by our group during an intravenous (9) and an oral (10) glucose tolerance test. Campioni et al. used similar methods to derive standard kinetic parameters for insulin clearance, enabling the subsequent quantification of hepatic extraction (11).

Accordingly, we set out to measure glucagon kinetics in nondiabetic subjects and then derive standard kinetic parameters that could be utilized in the future experiments (8). To do so, we suppressed endogenous islet secretion using a pancreatic clamp. During these conditions, when endogenous glucagon secretion was suppressed for 120 min, infusion of glucagon at 0.65 ng/kg/min enabled the measurement of volume of distribution (Vd), half-life (t1/2), and clearance rate (CL) in study participants. Taking into account the anthropometric characteristics of the subjects, we were then able to derive standardized kinetic parameters for glucagon, which allow deconvolution of the rate of systemic glucagon appearance from glucagon concentrations. This is an important first step in the development of a model to study integrated islet function in humans.

METHODS

Screening

After approval by the Mayo Institutional Review Board, we utilized the Mayo Clinic Biobank (a repository of biological samples from 50,000 volunteers) to identify potential study subjects. To do so, we randomly selected individuals from the age span of 25–70 yr (thereby minimizing the potential confounding effects of age on glucose tolerance and insulin secretion), who had no history of diabetes and resided within a 100 mile radius of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Those individuals who expressed interest in participating were invited to the Clinical Research Unit for a screening visit. After written informed consent was obtained, participants underwent a 2-h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) to characterize their glucose tolerance status as previously described (12). All participants were not taking medications that could affect glucose metabolism and had no history of chronic illness or upper gastrointestinal surgery. Subjects were in good health, were at a stable weight, and did not engage in regular vigorous exercise. All subjects were instructed to follow a weight-maintenance diet containing 55% of carbohydrate, 30% of fat, and 15% of protein for at least three days before the study. Body composition was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (iDXA scanner; GE, Wauwatosa, WI).

Experimental Design

Fifty-one subjects were studied on two occasions in random order, at least 2 wk apart. For the purposes of this manuscript, we will describe in detail the experiment germane to this work—an experiment designed to mimic postprandial glucagon suppression. Subjects were admitted to the Clinical Research and Trials Unit (CRTU) at 1700 on the day before study. They then consumed a standard 10 kcal/kg meal (55% of carbohydrate, 30% of fat, 15% of protein) and fasted overnight. The following morning (0530), a forearm vein was cannulated to allow infusions to be performed. In addition, a cannula was inserted retrogradely into a vein of the contra-lateral dorsum of the hand, which was then placed in a heated Plexiglas box maintained at 55°C to allow sampling of arterialized venous blood. At ∼0600 (-180 min), a primed (10 µCi prime, 0.1 µCi/min continuous) infusion containing trace amounts of glucose labeled with [3-3H] glucose was started and continued till 0900 (0 min). At 0900 (0 min), the infusion was decreased so as to mimic the anticipated fall of endogenous glucose production (EGP). In addition, a “prandial” glucose infusion also labeled with [3-3H] glucose was started so as to produce glucose concentrations similar to those observed after oral ingestion of 75 g glucose (13).

Simultaneously, an infusion of somatostatin (60 ng/kg/min) was started at 0900 (0 min) to inhibit endogenous islet secretion and therefore ensure identical portal insulin concentrations on the two study days (14). Insulin was infused using a variable infusion rate to mimic postprandial insulin secretion. Glucagon was infused at 0.65 ng/kg/min from 1100 (120 min) till the end of the study at 1400 (300 min) to mimic the normal postprandial pattern of suppression of glucagon.

The second experimental day—whose results are not used in the present analysis—was designed to mimic the absence of postprandial glucagon suppression. The experimental design was identical except that glucagon was infused continuously at 0.65 ng/kg/min from 0900 (0 min) till the end of the study at 1400 (300 min). A similar approach had been utilized previously (15, 16).

Analytic Techniques

All blood was immediately placed on ice, centrifuged at 4°C, separated, and stored at −80°C until assay. Glucagon was measured using a two-site ELISA (Mercodia, Winston Salem, NC) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay has an interassay coefficient of variation (CV) of 6.6% at 4.8 pmol/L, 5.5% at 14.9 pmol/L, and 7.0% at 45.9 pmol/L, and it has a detectability range of 1.7–130 pmol/L.

Calculations

The time course of glucagon concentration during a constant infusion can be modeled as a sum of exponentials (17), given by the formula:

| (1) |

where ir is the infusion rate, specified in the experimental design; N is the number of exponentials; t0 is the infusion start time; Ai are the amplitudes of the exponentials; and αi is their decay constant.

The model was identified on glucagon data by using a Bayesian maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimator, where the prior was noninformative for Ai and αi and Gaussian with a mean based on the sampling schedule and standard deviation of 20% for t0. The fit of a single- versus a double-exponential model was compared, with the one exponential showing superior ability to describe the data; thus, we subsequently fixed N equal to 1. We then derived the individualized glucagon kinetics [volume of distribution (Vd), half-life (t1/2), and clearance rate (CL)] from the exponential expression, using the formulas:

| (2) |

The dependence of the kinetic parameters and common anthropometric characteristics [age, weight, height, sex, lean body mass (LBM), body mass index (BMI), and body surface area (BSA)] was studied using a stepwise regression analysis in MATLAB (ver. 2018a). A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Finally, we used the newly estimated glucagon kinetic parameters to reconstruct the secretion rate of glucagon from the glucagon concentrations observed during the screening OGTT by the use of nonparametric deconvolution (18), mirroring the approach used to estimate insulin secretion (19).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Stepwise regression analysis was performed as outlined above. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Volunteer Characteristics

We studied 51 subjects (17 males and 34 females), with a mean age of 54 ± 13 yr and a BMI of 28.2 ± 3.9 kg/m2 (means ± SD). Detailed anthropometric characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics and kinetic parameters in all the studied subjects and in subject grouped by sex

| All (51) | Male (17) | Female (34) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 54.4 ± 12.7 | 52.4 ± 14.9 | 55.4 ± 11.5 |

| Total body mass, kg | 81.9 ± 15.3 | 91.0 ± 13.0 | 77.3 ± 14.4 |

| Lean body mass, kg | 47.5 ± 10.4 | 59.6 ± 3.4 | 41.5 ± 5.5 |

| Height, cm | 170.1 ± 9.8 | 179.5 ± 6.2 | 165.4 ± 7.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.2 ± 3.9 | 28.2 ± 3.4 | 28.1 ± 4.1 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| Exponential Parametrization | |||

| A1, L−1 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.05 |

| α1, min−1 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.05 |

| Kinetic parameters | |||

| Volume, L | 8.18 ± 2.68 | 9.23 ± 2.45 | 7.65 ± 2.67 |

| t1/2, min | 3.96 ± 1.12 | 4.01 ± 1.19 | 3.94 ± 1.10 |

| CL, L/min | 1.44 ± 0.33 | 1.64 ± 0.36 | 1.34 ± 0.27 |

| Vol/TBM, L/kg | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.03 |

Data reported as means ± SD. BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CL, clearance rate; TBM, total body mass.

Glucagon Concentrations during Fasting and Experimental Conditions

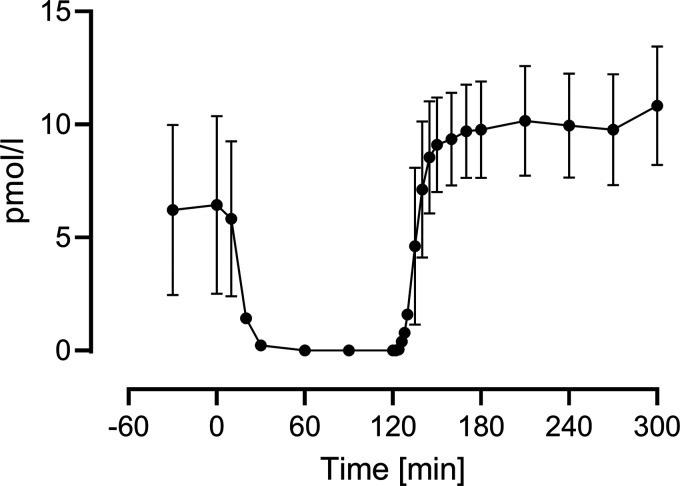

Mean fasting glucagon concentration was 6.4 ± 3.7 pmol/L. After the start of the somatostatin infusion, concentrations fell rapidly, so that within 30 min most of the subjects were below the assay’s lower limit of detectability. After the start of the infusion at 1100 (120 min), glucagon concentrations rose to a steady-state concentration (10.1 ± 2.5 pmol/L over the last hour of the experiment) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Measured glucagon concentrations during the experiment, averaged across the population. Vertical bars represent SDs. SD, standard deviation.

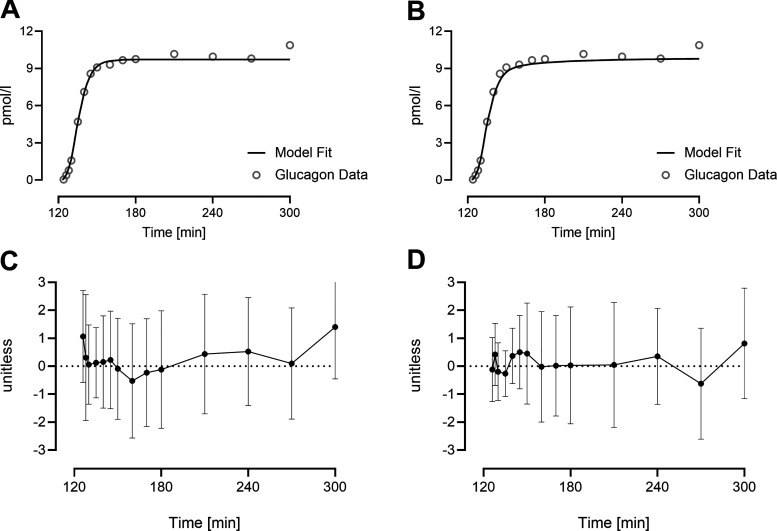

Modeling of Glucagon Concentrations during Glucagon Infusion

A single-exponential model was able to fit glucagon concentrations in all 51 subjects (Fig. 2A), and all the parameters were estimated with good precision (CVs < 30%). On the other hand, a two-exponential model provided an acceptable fit in only 39 subjects because in the remainder, the estimates collapsed to a single-exponential model (Fig. 2B). The fit of the two-exponential model reduced the weighted residual sum of squares (41.1 vs. 34.6 for the single- and double-exponential model, respectively), while also significantly increasing the error of estimation (CVs > 1,000%). Average values for the two-exponential models and their performance indices are reported in Table 2. The weighted residuals for the one- and two-exponential models over the course of the experiment are shown in Fig. 2, C and D, respectively.

Figure 2.

Average glucagon concentration (dot) and average model prediction (line) using a single-exponential model in 51 subjects (A) and a double-exponential model in 39 subjects (B). Average weighted residuals of the subjects’ fit are reported for the one-exponential (C) and two-exponential (D) model, with vertical bars representing SDs. SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Estimated exponential parameters using the one- and two-exponential models to describe the glucagon data

| A1, L−1 | α1, min−1 | A2, L−1 | α2, min−1 | Residual Independence | CV | WRSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-exponential model(n = 51) | 0.14 | 0.19 | – | – | 100% | 16% | 41.1 |

| Two-exponential model(n = 39) | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 97% | >1,000% | 34.6 |

Average values are reported alongside three indices of model performance: percentage of cases with residue randomness (residual independence), mean coefficient of variation (CV), and mean weighted residual sum of squares (WRSS).

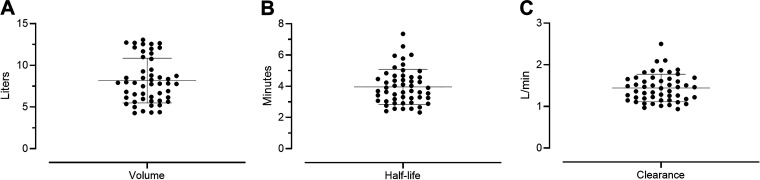

Assessment of Individualized Glucagon Kinetics

The exponential parameters were used to calculate the individualized kinetic values (Fig. 3, A–C), described in Eq. 2. The volume of distribution was normalized by total body weight (Fig. 3D). Average and standard deviation for kinetic values are reported in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Glucagon kinetics values showing volume of distribution (A), half-life (B), and clearance (C).

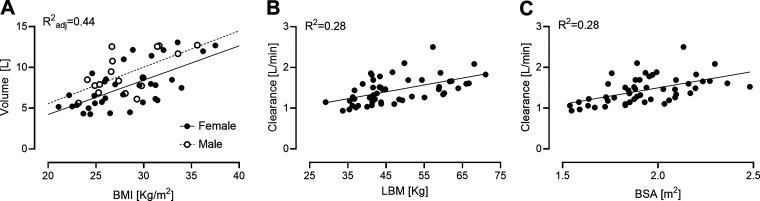

Assessment of Standardized Glucagon Kinetics

Among the tested regressions, volume of distribution and clearance showed the strongest correlations. In particular, the stepwise regression selected both BMI and sex as regressors to predict Vd (Fig. 4A, R2adjusted = 0.44). For the clearance, both LBM (Fig. 4B, R2 = 0.28) and BSA (Fig. 4C, R2 = 0.28) showed a similar performance.

Figure 4.

Correlations between individualized glucagon kinetic and anthropometric characteristics. Volume of distribution depended on body mass index and sex (rmen = 0.61, rwomen = 0.64, A). Clearance exhibited a similar relationship with lean body mass (r = 0.53, B) and body surface area (r = 0.53, C).

The linear regression models, linking Vd and CL with their regressors, are as follows:

| (3) |

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare individual glucagon kinetics with those calculated using the population-based models described above (Eq. 3). The values for Vd and CL calculated using the population-based models did not differ from the individualized values.

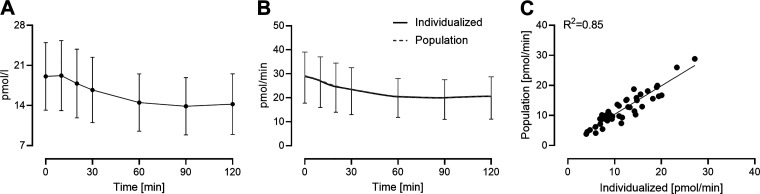

Use of Individualized and Standardized Glucagon Kinetics to Calculate the Posthepatic Rate of Glucagon Appearance

Both individualized and population-based kinetic parameters were used to deconvolve glucagon concentrations measured at the time of screening OGTT. By applying the individually determined kinetic parameters, as well as those derived from the population model, to the observed glucagon concentrations (Fig. 5A), the individualized and population-based rate of glucagon appearance in the systemic circulation, respectively, can be estimated during the glucose stimulus (Fig. 5B). The accuracy of the estimated rates did not differ significantly when calculated using individualized or population-based kinetic parameters. Comparison of the suppression of glucagon appearance (the difference between fasting and nadir values for glucagon appearance—Fig. 5C) obtained using individualized or population-based kinetic parameters showed strong correlation (R2 = 0.85).

Figure 5.

Glucagon concentration during a screening OGTT (A) and the estimated rates of systemic appearance using individualized and population kinetics (B). The difference between fasting and nadir values for glucagon appearance derived using individualized glucagon kinetic parameters correlated with those derived using population-based parameters (C). OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt at deriving standardized glucagon kinetic parameters from their direct measurement in a medium-sized group of otherwise healthy individuals. Subsequently, as proof of principle, we used glucagon concentrations measured during a screening OGTT to derive the systemic rate of glucagon appearance. The use of standardized, population-based kinetics produced rates of appearance that did not differ from those obtained using individual glucagon kinetic parameters. This is a necessary first step toward measuring glucagon secretion and action in larger populations.

Why is this important? Glucagon and insulin have opposing effects on glucose metabolism. At present, the gold standard measurement for insulin secretion and action—the oral minimal model—ignores α-cell function. Therefore, to better assess integrated islet function and appreciate the role of glucagon in the pathogenesis of glucose intolerance, precise measures of glucagon secretion are necessary (7). Since concentrations of a given hormone in the peripheral circulation represent a balance between secretion and clearance, a first step toward measuring glucagon secretion is the development of robust measures of the hormone’s volume of distribution, half-life, and clearance rate.

In our data set, the exponential parametrization allowed us to derive individualized glucagon kinetic parameters. Analysis of the weighted residuals and the precision of the parameters showed that a single-exponential model was a more flexible and better descriptor of the data. With this model, glucagon volume of distribution was estimated at around 8 L, with a fast half-life of 4 min and a clearance of 1.4 L/min. As an internal validation, the value for clearance obtained using the steady-state concentrations prevailing during glucagon infusion in the last hour of study provides very similar rates of clearance (1.4 ± 0.4 L/min, data not shown).

To date, surprisingly few studies have examined glucagon kinetics in humans. In people with type 1 diabetes, euglycemia or hyperglycemia did not seem to alter glucagon clearance during a glucose clamp. The reported rate (∼0.02 L/kg/min—i.e., ∼1.4 L/min for a 70-kg human) of that study (20) is similar to what we observed in our current experiment. Pontiroli et al. (21) also studied 5 healthy subjects and 11 people with type 1 diabetes. When glucagon was administered intravenously in their healthy group, they reported a single-exponential model as the best fit for the data, in addition to a clearance rate (18.9 mL min−1 kg−1) similar to the values obtained in our experiment (18.1 mL min−1 kg−1). They also measured an average half-life of 6.6 min, which is higher than what we report (4 min). The mean volume of distribution they reported was twice as high (0.19 L/kg) as the mean values we observed (0.10 L/kg). In both cases, the volume of distribution of glucagon exceeds the circulatory volume despite low lipid solubility for glucagon, but in keeping with a low rate of ionization of the hormone in the circulation and low binding to plasma proteins—factors expected to increase volume of distribution of peptides (22).

However, it is unclear as to why there would be these differences in glucagon volume of distribution and half-life between the two studies. One potential explanation for these discrepancies is that in Ref. (21) endogenous glucagon secretion was not inhibited by somatostatin. In addition, the sample size was also likely to be too small to capture the variation in glucagon kinetics in a representative population. In addition, glucagon arises from post-translational processing of proglucagon in the α-cell, but other proglucagon-derived peptides can be detected in the plasma (23). Commercial assays differ in their specificity for glucagon, and some are susceptible to interference by peptides such as oxyntomodulin or glicentin (24, 25). Given that these peptides differ from native glucagon, their clearance rate and half-life in the circulation are also likely to differ. The specificity of the assay used by Pontiroli et al. for glucagon, as opposed to other proglucagon-derived peptides (with different rates of clearance and volumes of distribution), is uncertain (21). Differences in body composition could explain the discrepancies observed, but the subjects studied in (21) were leaner (BMI 22.9 kg/ m2) than our cohort—and therefore expected to have a lower volume of distribution.

In our experimental design, the mechanical delay after the infusion pump was started at 120 min and a delay between the first appearance of glucagon and the rise in glucagon concentration above the assay’s lower limit of detectability introduced some uncertainty in our measurements. Because of these uncertainties, we opted for a Bayesian approach, as before (10), to estimate the time of glucagon appearance in the systemic circulation as a parameter of the model. This approach estimated an average delay of 3.8 ± 1.5 min, which, when combined with the single-exponential model, was able to fit the data with good precision.

Another potential limitation is that, unlike under physiologic conditions, glucagon was infused into the peripheral circulation in this experiment. α-Cells secrete glucagon into the portal circulation where it likely undergoes some degree of hepatic extraction before entering the systemic circulation (26, 27). Unlike the case with insulin (28), the degree of extraction is smaller (27) and does not seem to be altered by the glycemic state or glucagon secretion (26). Hepatic extraction as glucagon travels from the portal to the systemic circulation should not alter the kinetics of glucagon clearance from the peripheral circulation. However, absence of quantitation of this parameter, at the present time our data allow estimation of the rate of systemic (posthepatic) glucagon appearance.

After obtaining the individualized kinetic parameters, we subsequently derived stepwise linear regressions to estimate the parameters’ relationship with anthropometric characteristics. We found significant relationships between volumes of distribution in men and women with their BMI, as well as between glucagon clearances with LBM or BSA. In this data set, the correlation of clearance with LBM could imply a physiological relationship between glucagon and body mass. Indeed, glucagon agonists are associated with weight loss (29, 30). Although LBM and BSA provide similar estimation of glucagon clearance, measurement of LBM will require measurement of body composition, and therefore, BSA may be simpler to utilize in larger studies or in facilities, which do not have access to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

When compared to other groups that use the same methodology applied to different hormones (C-peptide and insulin), our analysis utilized a smaller, but more homogenous, sample of nondiabetic subjects. For example, it has been suggested that diabetes is associated with an increased volume of distribution and half-life of glucagon (21). To better pursue our study of prediabetes, we currently focused on a nondiabetic, middle-aged, and slightly overweight population. Similar experimental design and analysis will be needed to extend our finding to other population groups, as well as to determine the presence of any difference in glucagon kinetics in people with diabetes. It is however notable that our analysis found a stronger correlation between hormone kinetics (glucagon in this case) and anthropometric characteristics of our target population compared to what was reported by Van Cauter et al. (8) and Campioni et al. (11). This should translate into smaller errors in the estimation of kinetic parameters using anthropometric data—as borne out by the subsequent deconvolution of peripheral glucagon concentrations to quantitate glucagon appearance during a separate experiment (in response to an oral challenge).

In conclusion, analysis of glucagon concentrations after infusion of glucagon during a pancreatic clamp to inhibit endogenous secretion allows derivation of individual kinetic parameters for glucagon. This enabled the development of a population-based model using anthropometric characteristics to predict Vd and CL. These data demonstrate that it is feasible to derive glucagon kinetic parameters from anthropometric characteristics, and apply this information for deconvolution of glucagon secretion. These data open the door to noninvasive quantitation of glucagon secretion and its contribution to glucose tolerance in large populations.

GRANTS

This study was supported by US National Institutes of Health DK78646, DK116231, and DK126206 (to A. Vella), the Mayo Clinic General Clinical Research Center, University of Padova Research Grant CPDA145405, and Mayo Clinic General Clinical Research Center (UL1 TR000135).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.V. conceived and designed research; A.V., J.D.A., and A.M.E. performed experiments; M.C.L., A.V., J.D.A., D.J.S.W., and C.D.M. analyzed data; A.V. and C.D.M. interpreted results of experiments; M.C.L. prepared figures; A.V. drafted manuscript; M.C.L., A.V., J.D.A., D.J.S.W., A.M.E., and C.D.M. edited and revised manuscript; M.C.L., A.V., J.D.A., D.J.S.W., A.M.E., and C.D.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the study support and coordination provided by Paula Giesler, Jeanette Laugen, Brent McConahey, and Gail De Foster. We are also grateful for the excellent secretarial support of Monica Davis and Hanne Lucier.

REFERENCES

- 1.Unger RH, Orci L. The essential role of glucagon in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1: 14–16, 1975. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock G, Chittilapilly E, Basu R, Toffolo G, Cobelli C, Chandramouli V, Landau BR, Rizza RA. Contribution of hepatic and extrahepatic insulin resistance to the pathogenesis of impaired fasting glucose: role of increased rates of gluconeogenesis. Diabetes 56: 1703–1711, 2007. doi: 10.2337/db06-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobelli C, Man CD, Toffolo G, Basu R, Vella A, Rizza R. The oral minimal model method. Diabetes 63: 1203–1213, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db13-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Færch K, Vistisen D, Pacini G, Torekov SS, Johansen NB, Witte DR, Jonsson A, Pedersen O, Hansen T, Lauritzen T, Jørgensen ME, Ahrén B, Holst JJ. Insulin resistance is accompanied by increased fasting glucagon and delayed glucagon suppression in individuals with normal and impaired glucose regulation. Diabetes 65: 3473–3481, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db16-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma A, Varghese RT, Shah M, Man CD, Cobelli C, Rizza RA, Bailey KR, Vella A. Impaired insulin action is associated with increased glucagon concentrations in nondiabetic humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 103: 314–319, 2018. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams JD, Man CD, Laurenti MC, Andrade MD, Cobelli C, Rizza RA, Bailey KR, Vella A. Fasting glucagon concentrations are associated with longitudinal decline of β-cell function in non-diabetic humans. Metabolism 105: 154175, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah M, Varghese RT, Miles JM, Piccinini F, Dalla Man C, Cobelli C, Bailey KR, Rizza RA, Vella A. TCF7L2 genotype and α-cell function in humans without diabetes. Diabetes 65: 371–380, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db15-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Cauter E, Mestrez F, Sturis J, Polonsky KS. Estimation of insulin secretion rates from C-peptide levels. Comparison of individual and standard kinetic parameters for C-peptide clearance. Diabetes 41: 368–377, 1992. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toffolo G, De Grandi F, Cobelli C. Estimation of beta-cell sensitivity from intravenous glucose tolerance test C-peptide data. Knowledge of the kinetics avoids errors in modeling the secretion. Diabetes 44: 845–854, 1995. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.7.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varghese RT, Man CD, Laurenti MC, Piccinini F, Sharma A, Shah M, Bailey KR, Rizza RA, Cobelli C, Vella A. Performance of individually measured vs population-based C-peptide kinetics to assess beta-cell function in the presence and absence of acute insulin resistance. Diabetes Obes Metab 20: 549–555, 2018. doi: 10.1111/dom.13106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campioni M, Toffolo G, Basu R, Rizza RA, Cobelli C. Minimal model assessment of hepatic insulin extraction during an oral test from standard insulin kinetic parameters. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E941–948, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90842.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sathananthan A, Man CD, Zinsmeister AR, Camilleri M, Rodeheffer RJ, Toffolo G, Cobelli C, Rizza RA, Vella A. A concerted decline in insulin secretion and action occurs across the spectrum of fasting and postchallenge glucose concentrations. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 76: 212–219, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vella A, Shah P, Basu R, Basu A, Holst JJ, Rizza RA. Effect of glucagon-like peptide 1(7-36) amide on glucose effectiveness and insulin action in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 49: 611–617, 2000. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varghese RT, Viegas I, Barosa C, Marques C, Shah M, Rizza RA, Jones JG, Vella A. Diabetes-associated variation in TCF7L2 is not associated with hepatic or extrahepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes 65: 887–892, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db15-1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah P, Basu A, Basu R, Rizza R. Impact of lack of suppression of glucagon on glucose tolerance in humans. Am J Physiol 277: E283–290, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.2.E283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah P, Vella A, Basu A, Basu R, Schwenk WF, Rizza RA. Lack of suppression of glucagon contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 4053–4059, 2000. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caumo A, Cobelli C. Tracer experiment design for metabolic fluxes estimation in steady and nonsteady state. In: Modelling Methodology for Physiology and Medicine. London: Elsevier, 2014, p. 153–178. [ 10.1016/B978-012160245-1/50007-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Nicolao G, Sparacino G, Cobelli C. Nonparametric input estimation in physiological systems: problems, methods, and case studies. Automatica 33: 851–870, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0005-1098(96)00254-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sparacino G, Cobelli C. A stochastic deconvolution method to reconstruct insulin secretion rate after a glucose stimulus. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 43: 512–529, 1996. doi: 10.1109/10.488799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinshaw L, Mallad A, Man CD, Basu R, Cobelli C, Carter RE, Kudva YC, Basu A. Glucagon sensitivity and clearance in type 1 diabetes: insights from in vivo and in silico experiments. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 309: E474–486, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00236.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pontiroli AE, Calderara A, Perfetti MG, Bareggi SR. Pharmacokinetics of intranasal, intramuscular and intravenous glucagon in healthy subjects and diabetic patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 45: 555–558, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF00315314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang G, Zhang BB. Glucagon and regulation of glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E671–678, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00492.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holst JJ, Bersani M, Johnsen AH, Kofod H, Hartmann B, Orskov C. Proglucagon processing in porcine and human pancreas. J Biol Chem 269: 18827–18833, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Hartmann B, Veedfald S, Windelov JA, Plamboeck A, Bojsen-Moller KN, Idorn T, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Knop FK, Vilsboll T, Madsbad S, Deacon CF, Holst JJ. Hyperglucagonaemia analysed by glucagon sandwich ELISA: nonspecific interference or truly elevated levels? Diabetologia 57: 1919–1926, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3283-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Veedfald S, Plamboeck A, Deacon CF, Hartmann B, Knop FK, Vilsboll T, Holst JJ. Inability of some commercial assays to measure suppression of glucagon secretion. J Diabetes Res 2016: 8352957, 2016. doi: 10.1155/2016/8352957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herold KC, Jaspan JB. Hepatic glucagon clearance during insulin induced hypoglycemia. Horm Metab Res 18: 431–435, 1986. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishida T, Lewis RM, Hartley CJ, Entman ML, Field JB. Comparison of hepatic extraction of insulin and glucagon in conscious and anesthetized dogs. Endocrinology 112: 1098–1109, 1983. doi: 10.1210/endo-112-3-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meier JJ, Veldhuis JD, Butler PC. Pulsatile insulin secretion dictates systemic insulin delivery by regulating hepatic insulin extraction in humans. Diabetes 54: 1649–1656, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cegla J, Troke RC, Jones B, Tharakan G, Kenkre J, McCullough KA, Lim CT, Parvisi N, Hussein M, Chambers ES, Minnion J, Cuenco J, Ghatei MA, Meeran K, Tan TM, Bloom SR. Co-infusion of low-dose GLP-1 and glucagon in man results in a reduction in food intake. Diabetes 63: 3711–3720, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db14-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finan B, Yang B, Ottaway N, Smiley DL, Ma T, Clemmensen C, Chabenne J, Zhang L, Habegger KM, Fischer K, Campbell JE, Sandoval D, Seeley RJ, Bleicher K, Uhles S, Riboulet W, Funk J, Hertel C, Belli S, Sebokova E, Conde-Knape K, Konkar A, Drucker DJ, Gelfanov V, Pfluger PT, Muller TD, Perez-Tilve D, DiMarchi RD, Tschop MH. A rationally designed monomeric peptide triagonist corrects obesity and diabetes in rodents. Nat Med 21: 27–36, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nm.3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]