Abstract

The first year of life is a crucial period during which the composition and functionality of the gut microbiota develop to stabilize and resemble that of adults. Throughout this process, the gut microbiota has been found to contribute to the maturation of the immune system, in gastrointestinal physiology, in cognitive advancement and in metabolic regulation. Breastfeeding, the “golden standard of infant nutrition,” is a cornerstone during this period, not only for its direct effect but also due to its indirect effect through the modulation of gut microbiota. Human milk is known to contain indigestible carbohydrates, termed human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), that are utilized by intestinal microorganisms. Bacteria that degrade HMOs like Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Bifidobacterium breve dominate the infant gut microbiota during breastfeeding. A number of carbohydrate active enzymes have been found and identified in the infant gut, thus supporting the hypothesis that these bacteria are able to degrade HMOs. It is suggested that via resource-sharing and cross-feeding, the initial utilization of HMOs drives the interplay within the intestinal microbial communities. This is of pronounced importance since these communities promote healthy development and some of their species also persist in the adult microbiome. The emerging production and accessibility to metagenomic data make it increasingly possible to unravel the metabolic capacity of entire ecosystems. Such insights can increase understanding of how the gut microbiota in infants is assembled and makes it a possible target to support healthy growth. In this manuscript, we discuss the co-occurrence and function of carbohydrate active enzymes relevant to HMO utilization in the first year of life, based on publicly available metagenomic data. We compare the enzyme profiles of breastfed children throughout the first year of life to those of formula-fed infants.

Keywords: gut microbiota, human milk oligosaccharides, functional metagenomics, carbohydrate active enzymes, glycoside hydrolases, microbial communities

Introduction

The relationship between humans and the gut microbiota starts directly after birth and continues throughout life. The newborn gut is inoculated at birth with microorganisms that will be its first inhabitants. Through ecological succession, the infant gut gets enriched with microorganisms, and after the first year of life begins to reach a certain compositional stability (Lozupone et al., 2012). Several factors have been shown to influence the development of the gut microbiota composition in infants. The mode of birth, the gestation age, the type of feeding, the use of antibiotics, the environment and the mother’s secretor status are major components of this equation (Harmsen et al., 2000; Marques et al., 2010; Fouhy et al., 2012; Azad et al., 2013; Lewis et al., 2015). Even though the gut microbiota establishes a stable community with similarities to that of an adult roughly after the first 12–36 months (Lozupone et al., 2012; Bäckhed et al., 2015; Bokulich et al., 2016; Stewart et al., 2018), the infant microbiota preceding this period can affect lifelong health (Cox et al., 2014; O’Mahony et al., 2014; Serino et al., 2017; Carlson et al., 2018). The microbiota-mediated health effect in children is highly driven by the feeding in early life and sets breastfeeding as an important steering wheel of this process. The breast-milk derived palette of the infant gut microbiota has been associated, among others, with limited tendency to develop obesity (Luoto et al., 2011; Forbes et al., 2018), atopy (Fujimura et al., 2016) as well as various immunomodulatory factors (Schwartz et al., 2012; Fujimura et al., 2016). Even though bold associations are still controversial, several studies have found links between breastfeeding and lower occurrence of diseases like asthma (Silvers et al., 2012; Ahmadizar et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2019; Harvey et al., 2020) and eczema (Chiu et al., 2016; Elbert et al., 2017; Flohr et al., 2018), limited tendency for obesity (Yamakawa et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2014; Bider-Canfield et al., 2017; Modrek et al., 2017) and better cognition development (Angelsen et al., 2001; Boucher et al., 2017; Lenehan et al., 2020). Research endeavors focus on human milk because the “golden standard” of feed could also be the “golden ticket” for improving alternative infant nutrition.

Human milk derives its nutritious value from its complex composition. It is a conglomeration of energy storing macromolecules, namely proteins, carbohydrates and fat, and bioactive compounds, such as immune cells, hormones, antimicrobials, vitamins, and glycans of various sizes (Ballard and Morrow, 2013). The glycans are commonly termed as human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs). The bonds holding the structure of HMOs are not degraded in the upper gastrointestinal tract, thus they are indigestible carbohydrates. More than 95% of the HMOs reach the infant’s gut undigested (Engfer et al., 2000; Gnoth et al., 2000). There they can be utilized by certain bacteria that can degrade them, and quickly after the beginning of lactation, the gut microbiota is dominated by taxa belonging to the phylum Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria (Stark and Lee, 1982; Penders et al., 2006; Adlerberth and Wold, 2009; Albrecht et al., 2013; Bäckhed et al., 2015). Bifidobacteria, especially the Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium breve, and Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis, have proven to be ample HMO-degraders, and a number of their enzymes have been isolated (Møller et al., 2001; Wada et al., 2008; Yoshida et al., 2012). Genomic-based analysis and in vitro experiments have shown that the enzymatic repertoire related to HMO degradation is probably species or even strain-specific (Pokusaeva et al., 2011; James et al., 2016; Sakanaka et al., 2020). Since the complete dismantling of HMOs dictates enzymes for transportation, degradation, and utilization a certain collaboration is suggested. Indeed, different strains of the same species have been identified as being part of microbial communities, intra- and inter- individually (Asnicar et al., 2017; Lawson et al., 2019), thus adding to the known collaborative substrate utilization between bifidobacteria (Milani et al., 2015). Moreover, other species such as Bacteroides spp., Ruminococcus gnavus, Lactobacillus spp., Akkermansia muciniphila, Clostridium spp., and Escherichia coli have also been found to possess the ability to degrade certain HMOs or parts of them in mono- and cocultures (Marcobal et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2013; Thongaram et al., 2017; Kostopoulos et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Salli et al., 2021). Metabolic products are exchanged between bacteria via cross-feeding, creating a microbial network that collaboratively thrives in the presence of human milk carbohydrates (Bunesova et al., 2016; Schwab et al., 2017).

However, the gut microbiota composition of formula-fed infants has been found to be more diverse with higher prevalence and/or abundance of bacteria such as Clostridium difficile, E. coli, Veillonella spp., Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium), Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., and adult-associated bifidobacteria (Penders et al., 2006; Fallani et al., 2010; Azad et al., 2013; Gomez-Llorente et al., 2013; Bäckhed et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2020). However, for taxa such as those from the genus Bacteroides and Lactobacillus there is not a clear consensus in literature (Fallani et al., 2010; Gomez-Llorente et al., 2013; Bäckhed et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2020). Introduction of solid food is also a factor that has been shown to shift the microbiome toward a more adult-like state (Bergström et al., 2014; Bäckhed et al., 2015) and was recently associated with taxa such as A. muciniphila, Bacteroides spp., Erwinia spp., Streptococcus spp., and Veillonella spp. (Differding et al., 2020). These findings demonstrate that human milk can be a major driver for the gut microbiota during this critical window. It is suggested that these profiles of infants, receiving or not receiving, human milk derive from the metabolic pressure applied by the presence and absence of HMOs, respectively. Therefore, it is of interest to explore the Carbohydrate Active Enzymes (CAZymes) profiles of the gut microbiota in milk-fed infants that are relevant to HMO-degradation. In this analysis review we focus on glycoside hydrolases related to HMO-degradation within the first year of life and current advances concerning their presence and importance. We compared these profiles to that of children who were formula fed. To assist our objective, we employed publicly available Metagenome Assembled Genomes (MAGs; Nayfach et al., 2019) based on metagenomic data from infants up to 12 months old (Bäckhed et al., 2015) with various feeding backgrounds.

Energy Storing Glycans of Human Milk and Alternative Infant Feeding

Human milk oligosaccharides are the second most abundant carbohydrate in human milk after lactose (60 g/L) (Urashima et al., 2017). Total HMO concentrations can vary dependent on time, starting from 20 to 25 g/L in foremilk and reaching 5–20 g/L in hindmilk (Coppa et al., 1993; Thurl et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2017; Meemken and Qaim, 2018). These oligosaccharides consist of a lactose core decorated with N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc), D-galactose (Gal), N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) and L-fucose (Fuc) (Wu et al., 2010) (Figure 1). Up to date, more than 200 structures have been identified in human milk, all of which are an elongation product of 19 core structures (Urashima et al., 2017). The core structures can be categorized depending on the bond formed between galactose and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine. In lactose, Gal and glucose (Glc) are connected with β1-4 linkage creating a disaccharide. Lactose is elongated with the addition of a disaccharide with a β1-3 or β1-6 bond. These can be Lacto-N-biose, where GlcNAc is connected to Gal with a β1-3 bond, or N-acetyllactosamine, where GlcNAc is connected to Gal with a β1-4 bond. These lead to a Type I or Type II chain, respectively. The tetrasaccharide can be further decorated with Fuc or Neu5Ac or the Lacto-N-biose/N-acetyllactosamine disaccharide. The configuration of the HMO can be either linear or branched. When a disaccharide is attached to the 3N of Gal, the 6N is available and its decoration leads to a branched structure, and vice versa (Urashima et al., 2017). Up to date, there have not been any characterized structures with an additional Glc or lactose in their structure. The variability of HMOs in mothers additionally depends on their Secretor Status and Lewis blood type which is defined by the presence or absence and position of the fucose residues on the HMOs (Scheneel-Brunner et al., 1972; Viverge et al., 1990; Kelly et al., 1995; Yip et al., 2007; Underwood et al., 2015). Some HMO structures are also sialylated, thus resulting in 8–21% of the total HMO concentration (Totten et al., 2012). Fuc residues can be attached by an α1-2, α1-3, or α1-4 linkage and Neu5Ac by an α2-3 or α2-6 linkage.

FIGURE 1.

Structural backbone of (A) HMOs, (B) GOS, and (C) FOS.

On the other hand, infant formula, a common breast milk analog, does not contain HMOs. Some products, however, contain plant-based indigestible carbohydrates such as galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) and fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) to mimic some of the benefits of HMOs (Figure 1). GOS are made out of a lactose core elongated by Gal monomers (β1-3-Gal, β1-4-Gal, or β1-6-Gal) reaching a degree of polymerization (DP) from 2 to 8 (Verkhnyatskaya et al., 2019). FOS are made of the addition of repetitive fructose moieties to a glucose unit with a DP from 2 to 60. Dependent on the number of fructose molecules the FOS are characterized as inulin (DP = 2–60), oligofructose or long chain fructooligosaccharides (DP < 20) or short chain fructooligosaccharides (DP < 5) (Sabater-Molina et al., 2009; Akkerman et al., 2019). Inulin type FOS (Figure 1) are considered here due to their popularity as infant formula ingredients (Sorour et al., 2017).

Glycoside Hydrolases Toward Milk Associated Oligosaccharides in Infancy: Presence and Importance

Characterized Glycoside Hydrolases

The HMOs found in human milk are an excellent substrate for bacteria that possess the suitable enzymatic abilities to degrade them. This is suggested to stir the microbial community toward the dominance of bifidobacteria in early life gut microbiota. Research in the last decade has focused majorly on the characterization of bifidobacterial (B. breve, B. longum, B. bifidum) enzymes to elucidate the complete degradation pattern of HMOs. Similarly, respective focus has been applied to enzymes that degrade the common prebiotics, GOS and FOS, that are added in infant formulas. Glycoside hydrolases are necessary to break the bonds that withhold the structures of these oligosaccharides. These are enzymes of hydrolytic capacity, meaning that they react with water to abolish glycosidic bonds in a retaining or inverting manner. According to their primary structure, they are classified into 167 families up to this date (Lombard et al., 2014). For this review, we have summarized the GH families that are related to the degradation of HMOs, GOS and FOS based on experimentally acquired data (Table 1). The results are restricted to enzymes that have been currently characterized by the following means in bacteria that are highly abundant in infant gut: isolation and purification, knock-out of gene and research of function, gene expression micro-arrays, proteomics or patent.

TABLE 1.

GH families of the infant gut microbiota and their identified specific enzymes that have been found to take part in HMO, GOS and FOS degradation. Enzymes are associated with their target and the bacteria from which they have been isolated.

| GH family | Enzyme | EC number | Target | Bacteria | Genea | References | |

| HMO related | GH18 | Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase/Endoglycosidase | EC 3.2.1.96 | Galβ1-3GlcNAc2 Galβ1-4GlcNAc2 | B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | EndoBI-1 | Parc et al., 2015; Karav et al., 2016; Garrido et al., 2018 |

| B. longum subsp. infantis 157F/SC142 | EndoBI-2 | Fukuda et al., 2011; Garrido et al., 2018 | |||||

| GH20 | lacto-N-biosidase | EC 3.2.1.140 | GlcNAcβ1-3Gal GlcNAcβ1-6Gal | B. bifidum JCM1254 | lnbB | Wada et al., 2008 | |

| β-hexosaminidase/β-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminidase | EC 3.2.1.52 | B. bifidum JCM1254 | BbhI, BbhII | Miwa et al., 2010 | |||

| EC. 3.2.1.- | B. longum subsp. longum JCM1217 | BLLJ_1391 | Honda et al., 2013 | ||||

| B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_0459, Blon_0732, Blon_2355 | Garrido et al., 2012; Kavanaugh et al., 2013 | |||||

| GH29 | α-L-fucosidase | EC 3.2.1.51 | Fucα1-3Gal Fucα1-4Gal Fucα1-3GlcNAc Fucα1-4GlcNAc | B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_0248, Blon_0426, Blon_2336 | Sela et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013 | |

| B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_2336 | Sela et al., 2012 | |||||

| α-1,3/1,4-L-fucosidase | EC 3.2.1.111 | B. bifidum JCM1254 | afcB | Ashida et al., 2009 | |||

| GH33 | 2,3-2,6-a-sialidase | EC 3.2.1.18 | Neu5Acα2-3Gal Neu5Acα2-6Gal Neu5Acα2-6GlcNAc | B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697 | nanH1, nanH2 | Sela et al., 2011 | |

| B. bifidum JCM1254 | SiaBb2 | Kiyohara et al., 2011 | |||||

| B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_2348 | Kim et al., 2013 | |||||

| GH85 | Endo-β-N -acetylglucosaminidase/Endoglycosidase | EC 3.2.1.96 | Galβ1-3GlcNAc2 Galβ1-4GlcNAc2 | B. longum NCC2705 B. longum DJO10A B. breve | EndoBB | Schell et al., 2002; Garrido et al., 2018 | |

| GH95 | α-1,2-L-fucosidase | EC 3.2.1.63 | Fucα1-2Gal | B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_2335 | Sela et al., 2012 | |

| B. bifidum JCM1254 | afcA | Ashida et al., 2009 | |||||

| GH112 | GNB/LNB phosphorylase | EC 2.4.1.211 | Galβ1-3GlcNAc | B. breve UCC2003 | lnbP | James et al., 2016 | |

| B. bifidum JCM1254 | LnpA1, LnpA2 | Nishimoto and Kitaoka, 2007; Nishimoto et al., 2012 | |||||

| GH136 | lacto-N-biosidase | EC 3.2.1.140 | GlcNAcβ1-3Gal | B. longum subsp. longum JCM1217 | LnbX | Sakurama et al., 2013 | |

| HMO and GOS related | GH1 | β-1,4-galactosidase | EC 3.2.1.23 | Galβ1-4Glc | Putative | ||

| GH2 | β-1,4-galactosidase | EC 3.2.1.23 | Galβ1-4Glc | B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697 | Bga2A | Yoshida et al., 2012 | |

| B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_2334, Blon_0268 | Garrido et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013 | |||||

| B. breve UCC2003 | lacZ6 | James et al., 2016 | |||||

| B. breve UCC2003 | lacZ(2) | O’Connell Motherway et al., 2013 | |||||

| B. bifidum DSM20215 | BIF1, BIF2, BIF3 | Møller et al., 2001 | |||||

| B. bifidum JCM1254 | BbgIII | Miwa et al., 2010 | |||||

| B. bifidum NCIMB4117 | BbgI, BbgIII, BbgIV | Goulas et al., 2009 | |||||

| GH35 | β-galactosidase | EC 3.2.1.23 | Galβ1-4Glc | Other species | |||

| GH42 | β-galactosidase | EC 3.2.1.23 | Galβ1-4Glc Galβ1-3Gal Galβ1-4Gal Galβ1-6Gal | B. breve UCC2003 | galG, lntA | James et al., 2016 | |

| B. breve UCC2003 | galG, gosG | O’Connell Motherway et al., 2013 | |||||

| B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697 | Bga42A, Bga42B, Bga42C | Yoshida et al., 2012; Garrido et al., 2013; Viborg et al., 2014 | |||||

| B. infantis DSM20088 | INF1 | Møller et al., 2001 | |||||

| B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_2016, Blon_2416 | Kim et al., 2013 | |||||

| B. bifidum NCIMB4117 | BbgII | Goulas et al., 2009 | |||||

| GOS related | GH53 | Endo-galactanase | EC 3.2.1.89 | Galβ1-4Gal | B. breve UCC2003 | galA | O’Connell Motherway et al., 2013 |

| FOS related | GH32 | β-fructofuranosidase | EC 3.2.1.26 | Glcβ1-2Fru | B. breve UCC2003 | fosC | Ryan et al., 2005 |

| β-fructofuranosidase/fructan β-fructosidase | EC 3.2.1.80 EC 3.2.1.26 | Fruβ1-2Fru Glcβ1-2Fru | B. longum ATCC 15697 | B.longum_l1 | Ávila-Fernández et al., 2016 Warchol et al., 2002 | ||

| Exo-inulinase | EC 3.2.1.80 | Fruβ1-2Fru | B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_2056, Blon_0787 | Kim et al., 2013 | ||

| GH13 | Sucrose phosphorylase/inulinase | EC 2.4.1.7 | Glcβ1-2Fru | B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 | Blon_0128, Blon_1740, Blon_0282, Blon_2453 | Kim et al., 2013 |

*The enzymes for which the gene name is not provided are recorded by their genetic locus.

Human milk oligosaccharides are complex structures, and this trait is also depicted in the enzymatic repertoire needed to dismantle them (Table 1). When glycans are linked to peptides in the form of glycoproteins, the GH18 or GH85 endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidases are needed to free the oligosaccharides. GlcNAc residues, termed also as sialic acid, residues are cleaved by 2,3-2,6-a-sialidases of the GH33 family. Decorated fucose, in milk of Secretor mothers, is removed via α-L-fucosidases which belong to GH29 and GH95, dependent on their specificity. In the main HMO chain, hydrolysis of the β1-3 bond in Lacto-N-biose and the β1-4 bond in N-acetyllactosamine is catalyzed by LNB/GNB phosphorylases of the GH112 family. The release of lactose from the adjacent GlcNAc is performed by lacto-N-biosidases of the GH20 and GH136 families or β-hexosaminidases/β-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminidases of GH20. The remaining lactose from HMOs as well as free human milk lactose is targeted by β-galactosidases able to hydrolyze β1-4 linkages. To date, all experimentally characterized β-galactosidases belong to the GH2 and GH42 families. There are not any characterized GH1 family β-galactosidases from highly abundant bacterial inhabitants of the infant gut. However, putative in silico characterized β-galactosidases from this family may prove their ability to target HMOs in the future. Accordingly, GH35 β-galactosidase activity has been described for the less abundant mucus associated bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila, able to catalyze the removal of Gal from the GlcNAcβ1-3Gal and GlcNAcβ1-6Gal disaccharides (Guo et al., 2018; Kostopoulos et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). The inherent differences in the β-galactosidases of the four families in terms of structure and substrate handling were recently explained (Kumar et al., 2019). The ability of GH2 to accumulate distinct domains and the evidence of its β-galactosidases to successfully bind lactose as well as the capacity of GH42 to actively interact with broadly linked Gal could be a possible explanation for their presence in successful utilization of HMOs.

The degradation of common infant formula oligosaccharides, GOS and FOS, requires an alternate and more concise glycoside hydrolase profile (Table 1). GOS have a less complex structure, and their degradation relies on the previously explained enzymes of the GH2 and GH42 families. The utilization of FOS requires mainly enzymes that cleave the Fuc moieties from the oligosaccharides and belong to the GH13, GH32, and GH68 families. However, agreeing to previous exploratory attempts (Chia, 2018) there were no available data for characterized GH68 enzymes in known infant gut bacteria.

Human Milk and Alternative Feeding Enrich Pre-weaning Infants With HMO-Related GHs

The first diet humans come in contact with is milk. The breastfeeding lasts approximately 6 months, but depending on other factors such as the availability of the breast milk or the societal context, it can last up to 12 months or 2 years (Figure 2) (Gianni et al., 2019; World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund, 2019). During that period, for many children across the globe, milk consumption also means alternative forms of feeding like infant formula. Almost 75% of infants in the western world and 60% globally will receive infant formula within the first six months (Theurich et al., 2019; World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund, 2019).

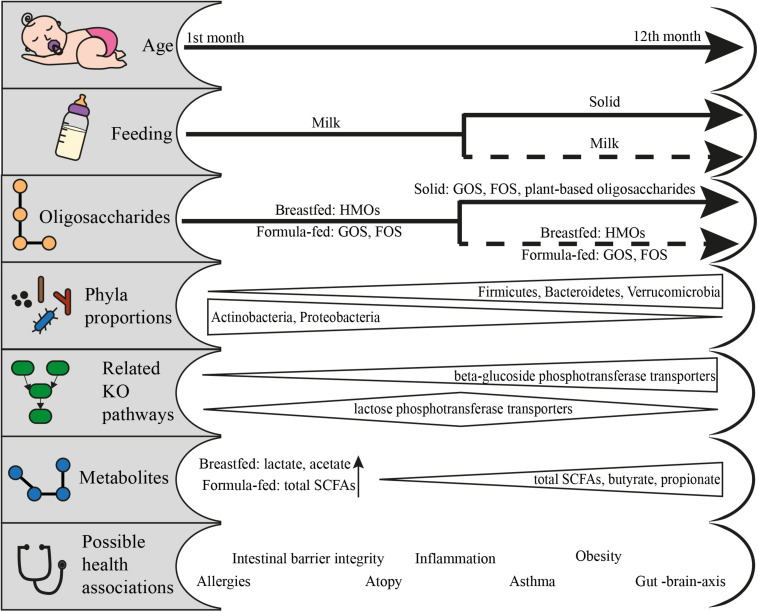

FIGURE 2.

From feeding to health outcomes in the first year of life: feeding patterns and the respective available oligosaccharides, the change in phyla proportions, the KO pathways related to the utilization of fed oligosaccharides, the metabolites produced and the possible health associations. Data adapted from Schwiertz et al. (2010), Koenig et al. (2011), van der Aa et al. (2011), Bäckhed et al. (2015), Huang et al. (2017), Cait et al. (2019), Roduit et al. (2019), Venegas et al. (2019), and Differding et al. (2020).

Infants quickly gain microbial communities that are capable of utilizing the increased concentrations of milk carbohydrates such as lactose and HMOs (Bäckhed et al., 2015). Bäckhed et al. (2015) found that the HMO-relevant GH2, GH18, GH29, GH35, GH42, GH85, and GH95 were more enriched in breastfed compared to formula-fed children of 4 months, but in a non-significant manner. Agreeingly, Ye et al. (2019) demonstrated no significant differences in GHs based on the same cohort. These results contradict the image of differential species abundances between the two groups. The general nature of some GHs like GH2, GH13, and GH42 regarding the targeted substrate can be a factor leading to that result. It should also be taken into consideration that the enzymatic capabilities of the community have been found to be determined by its members (Bäckhed et al., 2015; Lawson et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2019). In general, bifidobacteria contain the highest amount of genetically identified CAZymes related to human milk consumption (Ye et al., 2019). This ability has been attributed to different species or even different strains of this genus within the same subject. For example, the GH29 family that includes the enzymes relevant to cleavage of fucose was only present in Bifidobacterium infantis strains and not B. longum, B. breve or Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum in infant metagenomes (Lawson et al., 2019). Current studies show data that justify the enzymatic contribution of more taxa that is yet to be fully elucidated (Milani et al., 2015; Turroni et al., 2016; Borewicz et al., 2020).

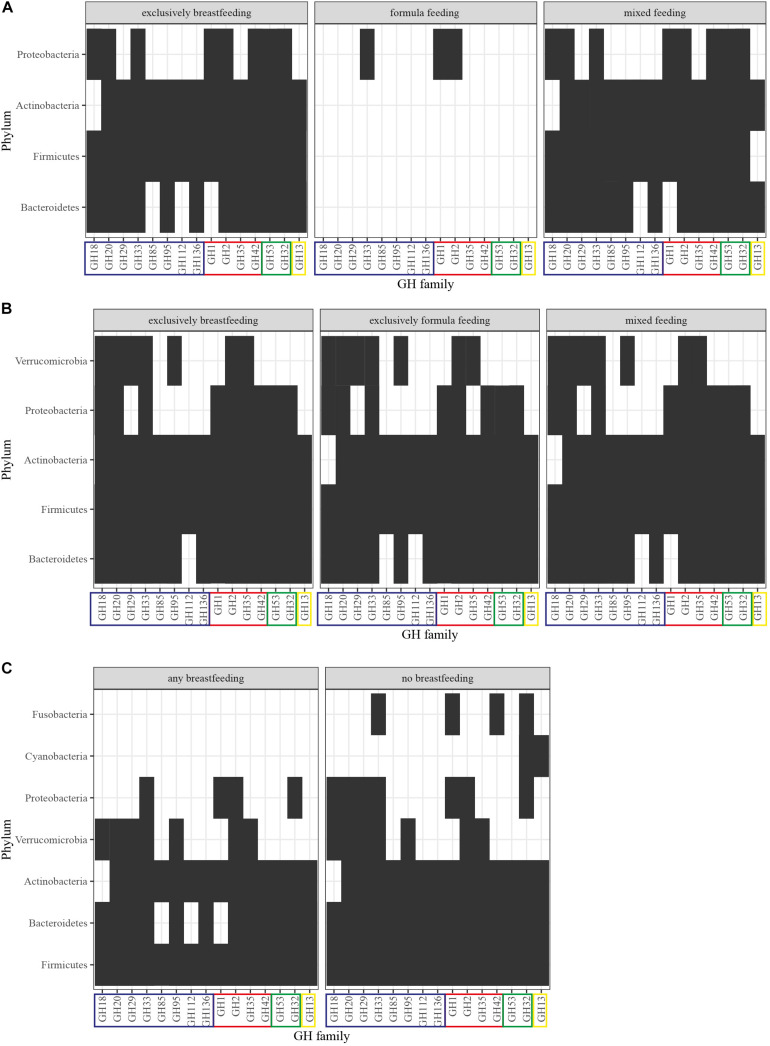

We, therefore, proceeded to summarize the presence of HMO-, GOS- and FOS-related GHs (Supplementary Material, In silico Analysis Method) per phylum in the gut microbiota from infants up to 12 months of age (Bäckhed et al., 2015; Nayfach et al., 2019; Supplementary Figure 1). Our analysis illustrates that as infants reach the first 4 months of age, their gut microbiota becomes more diverse, thus contributing their GHs toward oligosaccharide utilization (Figure 3). The GH profile of formula-fed newborns is greatly depleted, which could be attributed to underrepresentation as only one out of the 98 newborns in the cohort fall within that type of feeding. At 4 months, the GHs demonstrate a coherent presence in the differently fed infants with no absent GHs. However, in children who are exclusively breastfed, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria contribute activity from the GH85, GH18, and GH35 families, respectively, as opposed to the exclusively formula-fed infants. These enzymatic capabilities are attributed in silico to: Byturicimonas spp., Prevotella copri, and Bacteroides salyersiae (Bacteroidetes), Actinomyces_A neuii_A (Actinobacteria), Klebsiella oxytoca and Citrobacter HGM20797 (Proteobacteria). Future metagenomic data from infants are needed to assess whether these traits are detected in other cohorts as well. Consistency of such results would add to the current questions on how the microbial taxa dominate the infant gut microbiota and affect physiology, initiated from feeding.

FIGURE 3.

GH profiles per phylum and feeding in (A) newborns, (B) 4-month-old infants, and (C) 12-month-old infants. GHs were detected in MAGs of Nayfach et al. (2019) derived from the original dataset of Bäckhed et al. (2015). The identification method was based on domain-based Hidden Markov Models against the dbCAN CAZyme domain HMM database (Lombard et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018). GHs are grouped into: (blue) HMO-related, (red) HMO- and GOS-related, (green) GOS-related, (yellow) FOS-related. Presence of the GH family is signified with a black box and abscence with a white box.

The effects of this enzymatic utilization are evident on the infants of few months old to later life. Degradation of HMOs as well as GOS and FOS leads to the production of Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs), lactate and succinate. Lactate is especially dominant in the infant microbiome (Bridgman et al., 2017) and its benefits span from the cross-feeding of other bacteria (Pham et al., 2016) to the protection against pathogens (Fayol-Messaoudi et al., 2005; Duar et al., 2020) or the rejuvenation of gut epithelial cells (Lee et al., 2018). Especially breastfed infants have a higher concentration of acetate (Bridgman et al., 2017). It is interesting that Differding et al. (2020) found that the microbial communities during the milk-feeding period can get projected on the metabolome of 1-year-olds, especially for infants to which solid food is introduced early and have a more “mature” microbiota composition. Butyrate and propionate have been linked with lower occurrence of atopy coupled with experimentation on mice where SCFAs showed a promising annihilation of allergic airway inflammation (Roduit et al., 2019). The link is also evident on metagenomic data, where children whose microbiota had a lower percentage of GHs, in general as well as those related to HMO utilization, had a higher incidence of atopy (Cait et al., 2019). The same study linked those profiles with lower detection rate of genes implicated in butyrate fermentation. This agrees with the accumulated evidence on the protective nature of breastfeeding against allergy related manifestations.

Cessation of Breastfeeding Introduces GHs From a Wider Range of Phyla

After the first six months of life, introduction of solid food becomes an important aspect of the infant diet. Breastfeeding may or may not be performed during that period. This signifies an important milestone in the composition and functionality of the gut microbiota (Figure 2). During this period, the infant microbiome has been found to mature and resemble more that of adults. The species belonging to genera such as Bacteroides, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium, and Ruminococcus are introduced to the gut of children that receive solid food (Bergström et al., 2014; Bäckhed et al., 2015). However, genera dominating the younger gut such as Bifidobacterium, have still a pivotal role in the composition especially for the infants that continue to breastfeed (Fallani et al., 2011; Bäckhed et al., 2015). These reports further highlight the resource-pressure of human milk in shaping the gut microbiota in the first year of life.

In terms of GHs relevant to HMO, GOS, and FOS utilization (Table 1), no significant differences have been reported (Bäckhed et al., 2015; Ye et al., 2019). Interestingly, 12-month-old infants who were breastfed had a higher representation of these GHs, nevertheless in a non-significant manner (Bäckhed et al., 2015). Our previously described analysis highlights these findings and adds to the understanding of phyla contribution (Supplementary Figure 1). As seen in Figure 3, after cessation of breastfeeding, bacteria from the Fusobacteria and Cyanobacteria introduce GOS- and FOS-related GHs. However, HMO-related GHs are not depleted. Keeping in mind that GH families include various enzymes, this could be attributed to the effect of solid food on introducing a wider range of species in the gut and thus possibly increasing the overall GH genetic potential. Moreover, these enzymes are still relevant in the adult gut microbiota because they target plant- or host-derived glycans. Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes possess HMO-related GHs (GH18, GH20, GH29 and GH85, GH112, GH1, respectively) that are absent in 1-year-olds that receive human milk as primary or side-feeding. These are in silico attributed to the presence of genera like Enterobacter, Citrobacter, Hafnia, and Sutterella from Proteobacteria and Coprobacter, Butyricimonas, and Barnesiella from Bacteroidetes in non-breastfed infants. Publicly available data on the coverage of reads that constitute a GH domain within a certain species could give an indication of gut microbiota composition and relationships in terms of species functional enrichment.

Bacteria that become more abundant at 1 year of age, such as Bacteroides spp., are known to possess variable carbohydrate degrading abilities. Moreover, evidence suggest that mucin degradation, that can be inhibited earlier by B. longum subsp. infantis (Karav et al., 2018), is performed by, for example, the increasing Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, A. muciniphila (Bergström et al., 2014; Bäckhed et al., 2015; Differding et al., 2020) and the pre-established B. bifidum (Tsai et al., 1991; Derrien et al., 2004; Ruas-Madiedo et al., 2008). These O-glycans (Supplementary Figure 2) are targeted by some GHs that are common with the previously mentioned HMO-related CAZymes, namely fucosidases (GH29, GH95), sialidases (GH33), sulfatases, and β-hexosaminidases (GH20) (Chia, 2018; Chia et al., 2020; Kostopoulos et al., 2020). Absence of indigestible carbohydrates in gnotobiotic mice shifted the intestinal bacteria to transcriptional increase of CAZymes of mucin degradation (Desai et al., 2016), possible evidence of the protective role of prebiotics toward the integrity of the mucosal barrier. However, it has been shown that the major functional pressure of solid food is the wide range of substrates and the high amounts of plant indigestible carbohydrates. As in adults, the gut microbiota needs an array of GHs that can successfully degrade starch, pectin, xylan, arabinoxylan, arabinogalactan and other complex structures (Kaoutari et al., 2013; Bäckhed et al., 2015; Turroni et al., 2016).

Solid food affects the composition of the gut microbiota, and its results are evident in the first year and beyond. Total SCFA concentrations and the proportions of butyrate and propionate increase with solid food consumption and coincide with the proportional decrease of the non-butyrate producing bifidobacteria and the overall change in the proportion of the major phyla (Koenig et al., 2011; Differding et al., 2020). The role of microbial metabolites and the link to disease induction or protection are promising, but still quite scarce for infants, and sometimes controversial. SCFAs can have molecular interactions with intestinal cells, thus contributing to the regulation of inflammation (Venegas et al., 2019). The fortification with Bifidobacterium-containing symbionts protected the young intestinal cells (Zheng et al., 2020) and decreased the chances of asthma in atopic infants (van der Aa et al., 2011). SCFA-mediated effects of the gut microbiota are still emerging, with possible connection to better sleep (Szentirmai et al., 2019), protection against brain illness (Benakis et al., 2020) and behavior (Johnson and Foster, 2018). However, increased levels of SCFAs have also been correlated with obesity (Schwiertz et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2017). What is unanimously agreed, is that the first year of life is a critical timeframe for the establishment of the gut microbiota and that it has strong health implications for later life.

Conclusion and Perspectives

In this analysis review, we have summarized the function, the importance, and the presence of GHs related to human- and formula-milk in infants up to 12 months old. We utilized publicly available metagenomic data that profile the metabolic potential of complete microbial communities. The adaptation pressure that breastfeeding imposes on those communities is evident in the contribution of phyla to these profiles. The GHs that target HMOs and plant-based formula oligosaccharides show that they both enrich the same bacterial phyla, but in a different manner with possible effects on the composition of the gut microbiota, the metabolic products, and the maturation process of the microbiome.

Such data indicate that the entire microbial network, and not only the dominant and widely characterized Bifidobacterium spp., contribute to the functional effect of milk-related oligosaccharides. HMO-utilizers thrive in this period and produce a variety of by-products and metabolites that are harvested by adjacent microorganisms, such as butyrate-producers. Cross-feeding is suggested to generate the interactions between the different members of the community leading to the formation of a network. This is indispensable, as it lays the ground for the mature gut microbiota. HMO-utilizers could, thus, support the first indigenous inhabitants of the adult gut microbiota. Further isolation and characterization of GHs from intestinal bacteria will contribute to the knowledge on the specificity of these enzymes, as well as the ecological advantage they confer.

Currently, the emerging genomic and analytical chemistry methods allow investigation of the composition within the gut microbiota with high resolution, as well as the quantification of its metabolic products. However, the methods capturing the actual interplay between infant gut bacteria are scarce. Moreover, the complexity of the system hinders the distinction between the effect of diet and other factors, such as the delivery mode or the surrounding environment. More metagenomics analyses are needed to unravel the potential of the infant gut microbiota to produce certain compounds and to profile the differences dependent on feeding. Currently, this second part is only based in in vitro experiments, leaving space for experimental procedures that link the genetic potential with the metabolic products (via meta-proteomics and meta-transcriptomics). Closed microbial systems are a suggestion for modeling the structure to function relationship that can expand the research to other species residing in the infant gut.

Author Contributions

AI and CB initiated the ideas and concepts for this manuscript. AI wrote the manuscript. CB was involved in writing the manuscript. JK and CB supervised the project. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

JK is an employee of Danone Nutricia Research. This work is part of a project partially funded by Danone Nutricia Research. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was a part of the research funded by the Green Top Sectors Grant of NWO (GSGT.2019.002) including matching by Danone Nutricia Research.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.631282/full#supplementary-material

References

- Adlerberth I., Wold A. (2009). Establishment of the gut microbiota in Western infants. Acta Paediatr. 98 229–238. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01060.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadizar F., Vijverberg S. J. H., Arets H. G. M., de Boer A., Garssen J., Kraneveld A. D., et al. (2017). Breastfeeding is associated with a decreased risk of childhood asthma exacerbations later in life. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 28 649–654. 10.1111/pai.12760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkerman R., Faas M. M., De Vos P. (2019). Non-digestible carbohydrates in infant formula as substitution for human milk oligosaccharide functions: effects on microbiota and gut maturation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59 1486–1497. 10.1080/10408398.2017.1414030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht S., van den Heuvel E. G. H. M., Gruppen H., Schols H. A. (2013). “Gastrointestinal metabolization of human milk oligosaccharides,” in Handbook of Dietary and Nutritional Aspects of Human Breast Milk, eds Zibadi S., Ross Watson R., Preedy V. R. (Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers; ), 293–314. 10.3920/978-90-8686-764-6_15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen N. K., Vik T., Jacobsen G., Bakketeig L. S. (2001). Breast feeding and cognitive development at age 1 and 5 years. Arch. Dis. Child. 85 183–188. 10.1136/adc.85.3.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashida H., Miyake A., Kiyohara M., Wada J., Yoshida E., Kumagai H., et al. (2009). Two distinct α-l-fucosidases from Bifidobacterium bifidum are essential for the utilization of fucosylated milk oligosaccharides and glycoconjugates. Glycobiology 19 1010–1017. 10.1093/glycob/cwp082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnicar F., Manara S., Zolfo M., Truong D. T., Scholz M., Armanini F., et al. (2017). Studying vertical microbiome transmission from mothers to infants by strain-level metagenomic profiling. mSystems 2:e00164-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Fernández Á, Cuevas-Juárez E., Rodríguez-Alegría M. E., Olvera C., López-Munguía A. (2016). Functional characterization of a novel β-fructofuranosidase from Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 on structurally diverse fructans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 121 263–276. 10.1111/jam.13154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad M. B., Konya T., Maughan H., Guttman D. S., Field C. J., Chari R. S., et al. (2013). Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months. CMAJ 185 385–394. 10.1503/cmaj.121189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckhed F., Roswall J., Peng Y., Feng Q., Jia H., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., et al. (2015). Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe 17 690–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard O., Morrow A. L. (2013). Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 60 49–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benakis C., Martin-Gallausiaux C., Trezzi J. P., Melton P., Liesz A., Wilmes P. (2020). The microbiome-gut-brain axis in acute and chronic brain diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 61 1–9. 10.1016/j.conb.2019.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergström A., Skov T. H., Bahl M. I., Roager H. M., Christensen L. B., Ejlerskov K. T., et al. (2014). Establishment of intestinal microbiota during early life: a longitudinal, explorative study of a large cohort of Danish infants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80 2889–2900. 10.1128/aem.00342-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bider-Canfield Z., Martinez M. P., Wang X., Yu W., Bautista M. P., Brookey J., et al. (2017). Maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, breastfeeding and childhood overweight at age 2 years. Pediatr. Obes. 12 171–178. 10.1111/ijpo.12125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich N. A., Chung J., Battaglia T., Henderson N., Jay M., Li H., et al. (2016). Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci. Transl. Med. 8:343ra82. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borewicz K., Gu F., Saccenti E., Hechler C., Beijers R., de Weerth C., et al. (2020). The association between breastmilk oligosaccharides and faecal microbiota in healthy breastfed infants at two, six, and twelve weeks of age. Sci. Rep. 10:4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher O., Julvez J., Guxens M., Arranz E., Ibarluzea J., Sánchez, et al. (2017). Association between breastfeeding duration and cognitive development, autistic traits and ADHD symptoms: a multicenter study in Spain. Pediatr. Res. 81 434–442. 10.1038/pr.2016.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgman S. L., Azad M. B., Field C. J., Haqq A. M., Becker A. B., Mandhane P. J., et al. (2017). Fecal short-chain fatty acid variations by breastfeeding status in infants at 4 months: differences in relative versus absolute concentrations. Front. Nutr. 4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunesova V., Lacroix C., Schwab C. (2016). Fucosyllactose and L-fucose utilization of infant Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense. BMC Microbiol. 16:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cait A., Cardenas E., Dimitriu P. A., Amenyogbe N., Dai D., Cait J., et al. (2019). Reduced genetic potential for butyrate fermentation in the gut microbiome of infants who develop allergic sensitization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 144 1638–1647.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson A. L., Xia K., Azcarate-Peril M. A., Goldman B. D., Ahn M., Styner M. A., et al. (2018). Infant gut microbiome associated with cognitive development. Biol. Psychiatry 83 148–159. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia L. W. (2018). Cross-Feeding Interactions of Gut Symbionts Driven by Human Milk Oligosaccharides and Mucins. Wageningen: Wageningen University. [Google Scholar]

- Chia L. W., Mank M., Blijenberg B., Aalvink S., Bongers R. S., Stahl B., et al. (2020). Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron fosters the growth of butyrate-producing anaerostipes caccae in the presence of lactose and total human milk carbohydrates. Microorganisms 8:1513. 10.3390/microorganisms8101513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C. Y., Liao S. L., Su K. W., Tsai M. H., Hua M. C., Lai S. H., et al. (2016). Exclusive or partial breastfeeding for 6 months is associated with reduced milk sensitization and risk of Eczema in early childhood. Medicine 95:e3391. 10.1097/md.0000000000003391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppa G. V., Gabrielli O., Pierani P., Catassi C., Carlucci A., Giorgi P. L. (1993). Changes in carbohydrate composition in human milk over 4 months of lactation. Pediatrics 91 631–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox L. M., Yamanishi S., Sohn J., Alekseyenko A. V., Leung J. M., Cho I., et al. (2014). Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell 158 705–721. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien M., Vaughan E. E., Plugge C. M., de Vos W. M. (2004). Akkermansia municiphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54 1469–1476. 10.1099/ijs.0.02873-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M. S., Seekatz A. M., Koropatkin N. M., Kamada N., Hickey C. A., Wolter M., et al. (2016). A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell 167 1339–1353.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Differding M. K., Benjamin-Neelon S. E., Hoyo C., Østbye T., Mueller N. T. (2020). Timing of complementary feeding is associated with gut microbiota diversity and composition and short chain fatty acid concentrations over the first year of life. BMC Microbiol. 20:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duar R. M., Kyle D., Casaburi G. (2020). Colonization resistance in the infant gut: the role of B. infantis in reducing pH and preventing pathogen growth. High Throughput 9:7. 10.3390/ht9020007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert N. J., van Meel E. R., den Dekker H. T., de Jong N. W., Nijsten T. E. C., Jaddoe V. W. V., et al. (2017). Duration and exclusiveness of breastfeeding and risk of childhood atopic diseases. Allergy 72 1936–1943. 10.1111/all.13195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engfer M. B., Stahl B., Finke B., Sawatzki G., Daniel H. (2000). Human milk oligosaccharides are resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71 1589–1596. 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallani M., Amarri S., Uusijarvi A., Adam R., Khanna S., Aguilera M., et al. (2011). Determinants of the human infant intestinal microbiota after the introduction of first complementary foods in infant samples from five European centres. Microbiology 157 1385–1392. 10.1099/mic.0.042143-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallani M., Young D., Scott J., Norin E., Amarri S., Adam R., et al. (2010). Intestinal microbiota of 6-week-old infants across europe: geographic influence beyond delivery mode, breast-feeding, and antibiotics. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 51 77–84. 10.1097/mpg.0b013e3181d1b11e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayol-Messaoudi D., Berger C. N., Coconnier-Polter M. H., Liévin-Le Moal V., Servin A. L. (2005). pH-, lactic acid-, and non-lactic acid-dependent activities of probiotic lactobacilli against Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 6008–6013. 10.1128/aem.71.10.6008-6013.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohr C., John Henderson A., Kramer M. S., Patel R., Thompson J., Rifas-Shiman S. L., et al. (2018). Effect of an intervention to promote breastfeeding on asthma, lung function, and atopic eczema at age 16 years follow-up of the probit randomized trial. JAMA Pediatr. 172:e174064 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes J. D., Azad M. B., Vehling L., Tun H. M., Konya T. B., Guttman D. S., et al. (2018). Association of exposure to formula in the hospital and subsequent infant feeding practices with gut microbiota and risk of overweight in the first year of life. JAMA Pediatr. 172:e181161. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouhy F., Ross R. P., Fitzgerald G. F., Stanton C., Cotter P. D. (2012). Composition of the early intestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 3 203–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura K. E., Sitarik A. R., Havstad S., Lin D. L., Levan S., Fadrosh D., et al. (2016). Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat. Med. 22 1187–1191. 10.1038/nm.4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S., Toh H., Hase K., Oshima K., Nakanishi Y., Yoshimura K., et al. (2011). Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature 469 543–549. 10.1038/nature09646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido D., German J. B., Lebrilla C. B., Mills D. A. (2018). Enzymes and Methods for Cleaving N-glycans from Glycoproteins. U.S. Patent. Washington, DC: United States Patent and Trademark Office. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido D., Ruiz-Moyano S., Mills D. A. (2012). Release and utilization of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine from human milk oligosaccharides by Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis. Anaerobe 18 430–435. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2012.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido D., Ruiz-Moyano S., Jimenez-Espinoza R., Eom H. J., Block D. E., Mills D. A. (2013). Utilization of galactooligosaccharides by Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis isolates. Food Microbiol. 33 262–270. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni M. L., Bettinelli M. E., Manfra P., Sorrentino G., Bezze E., Plevani L., et al. (2019). Breastfeeding difficulties and risk for early breastfeeding cessation. Nutrients 11:2266. 10.3390/nu11102266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnoth M. J., Kunz C., Kinne-Saffran E., Rudloff S. (2000). Human milk oligosaccharides are minimally digested in vitro. J. Nutr. 130 3014–3020. 10.1093/jn/130.12.3014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Llorente C., Plaza-Diaz J., Aguilera M., Muñoz-Quezada S., Bermudez-Brito M., Peso-Echarri P., et al. (2013). Three main factors define changes in fecal microbiota associated with feeding modality in infants. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 57 461–466. 10.1097/mpg.0b013e31829d519a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulas T., Goulas A., Tzortzis G., Gibson G. R. (2009). Comparative analysis of four β-galactosidases from Bifidobacterium bifidum NCIMB41171: purification and biochemical characterisation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 82 1079–1088. 10.1007/s00253-008-1795-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B. S., Zheng F., Crouch L., Cai Z. P., Wang M., Bolam D. N., et al. (2018). Cloning, purification and biochemical characterisation of a GH35 beta-1,3/beta-1,6-galactosidase from the mucin-degrading gut bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila. Glycoconj. J. 35 255–263. 10.1007/s10719-018-9824-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen H. J. M., Wildeboer-Veloo A. C. M., Raangs G. C., Wagendorp A. A., Klijn N., Bindels J. G., et al. (2000). Analysis of intestinal flora development in breast-fed and formula-fed infants by using molecular identification and detection methods. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 30 61–67. 10.1097/00005176-200001000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey S. M., Murphy V. E., Gibson P. G., Collison A., Robinson P., Sly P. D., et al. (2020). Maternal asthma, breastfeeding, and respiratory outcomes in the first year of life. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 55 1690–1696. 10.1002/ppul.24756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y., Nishimoto M., Katayama T., Kitaoka M. (2013). Characterization of the Cytosolic β-N-Acetylglucosaminidase from Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum. Japanese Soc. Appl. Biosci. 60, 141–146. 10.5458/JAG.JAG.JAG-2013_001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Gao S., Chen J., Albrecht E., Zhao R., Yang X. (2017). Maternal butyrate supplementation induces insulin resistance associated with enhanced intramuscular fat deposition in the offspring. Oncotarget 8 13073–13084. 10.18632/oncotarget.14375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James K., Motherway M. O. C., Bottacini F., Van Sinderen D. (2016). Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 metabolises the human milk oligosaccharides lacto-N-tetraose and lacto-N-neo-tetraose through overlapping, yet distinct pathways. Sci. Rep. 6:38560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. V. A., Foster K. R. (2018). Why does the microbiome affect behaviour? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16 647–655. 10.1038/s41579-018-0014-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaoutari A., El, Armougom F., Gordon J. I., Raoult D., Henrissat B. (2013). The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11 497–504. 10.1038/nrmicro3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karav S., Casaburi G., Frese S. A. (2018). Reduced colonic mucin degradation in breastfed infants colonized by Bifido3bacterium longum subsp. infantis EVC001. FEBS Open Bio 8 1649–1657. 10.1002/2211-5463.12516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karav S., Le Parc A., Leite J. M., De Moura Bell N., Frese S. A., Kirmiz N., et al. (2016). Oligosaccharides released from milk glycoproteins are selective growth substrates for infant-associated bifidobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82 3622–3630. 10.1128/aem.00547-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh D. W., O’Callaghan J., Buttó L. F., Slattery H., Lane J., Clyne M., et al. (2013). Exposure of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis to milk oligosaccharides increases adhesion to epithelial cells and induces a substantial transcriptional response. PLoS One 8:e67224. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. J., Rouquier S., Giorgi D., Lennon G. G., Lowe J. B. (1995). Sequence and expression of a candidate for the human Secretor blood group alpha(1,2)fucosyltransferase gene (FUT2). Homozygosity for an enzyme-inactivating nonsense mutation commonly correlates with the non-secretor phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 270 4640–4649. 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H., An H. J., Garrido D., German J. B., Lebrilla C. B., Mills D. A. (2013). Proteomic analysis of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis reveals the metabolic insight on consumption of prebiotics and Host Glycans. PLoS One 8:e0057535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyohara M., Tanigawa K., Chaiwangsri T., Katayama T., Ashida H., Yamamoto K. (2011). An exo-α-sialidase from bifidobacteria involved in the degradation of sialyloligosaccharides in human milk and intestinal glycoconjugates. Glycobiology 21 437–447. 10.1093/glycob/cwq175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig J. E., Spor A., Scalfone N., Fricker A. D., Stombaugh J., Knight R., et al. (2011). Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108 4578–4585. 10.1073/pnas.1000081107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostopoulos I., Elzinga J., Ottman N., Klievink J. T., Blijenberg B., Aalvink S., et al. (2020). Akkermansia muciniphila uses human milk oligosaccharides to thrive in the early life conditions in vitro. Sci. Rep. 10:14330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Henrissat B., Coutinho P. M. (2019). Intrinsic dynamic behavior of enzyme:substrate complexes govern the catalytic action of β-galactosidases across clan GH-A. Sci. Rep. 9:10346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson M. A. E., O’Neill I. J., Kujawska M., Gowrinadh Javvadi S., Wijeyesekera A., Flegg Z., et al. (2019). Breast milk-derived human milk oligosaccharides promote Bifidobacterium interactions within a single ecosystem. ISME J. 14 635–648. 10.1038/s41396-019-0553-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-S., Kim T.-Y., Kim Y., Kamada N., Gao N., Correspondence M.-N. K. (2018). Microbiota-derived lactate accelerates intestinal stem-cell-mediated epithelial development in brief. Cell Host Microbe 24 833–846. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenehan S. M., Boylan G. B., Livingstone V., Fogarty L., Twomey D. M., Nikolovski J., et al. (2020). The impact of short-term predominate breastfeeding on cognitive outcome at 5 years. Acta Paediatr. 109 982–988. 10.1111/apa.15014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Z. T., Totten S. M., Smilowitz J. T., Popovic M., Parker E., Lemay D. G., et al. (2015). Maternal fucosyltransferase 2 status affects the gut bifidobacterial communities of breastfed infants. Microbiome 3:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P. M., Henrissat B. (2014). The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 D490–D495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone C. A., Stombaugh J. I., Gordon J. I., Jansson J. K., Knight R. (2012). Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489 220–230. 10.1038/nature11550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoto R., Kalliomäki M., Laitinen K., Delzenne N. M., Cani P. D., Salminen S., et al. (2011). Initial dietary and microbiological environments deviate in normal-weight compared to overweight children at 10 years of age. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 52 90–95. 10.1097/mpg.0b013e3181f3457f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Li Z., Zhang W., Zhang C., Zhang Y., Mei H., et al. (2020). Comparison of gut microbiota in exclusively breast-fed and formula-fed babies: a study of 91 term infants. Sci. Rep. 10:15792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcobal A., Barboza M., Sonnenburg E. D., Pudlo N., Martens E. C., Desai P., et al. (2011). Bacteroides in the infant gut consume milk oligosaccharides via mucus-utilization pathways. Cell Host Microbe 10 507–514. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques T. M., Wall R., Ross R. P., Fitzgerald G. F., Ryan C. A., Stanton C. (2010). Programming infant gut microbiota: influence of dietary and environmental factors. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21 149–156. 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meemken E.-M., Qaim M. (2018). Organic agriculture, food security, and the environment. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 10 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Milani C., Lugli G. A., Duranti S., Turroni F., Mancabelli L., Ferrario C., et al. (2015). Bifidobacteria exhibit social behavior through carbohydrate resource sharing in the gut. Sci. Rep. 5:15782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa M., Horimoto T., Kiyohara M., Katayama T., Kitaoka M., Ashida H., et al. (2010). Cooperation of β-galactosidase and β-N-acetylhexosaminidase from bifidobacteria in assimilation of human milk oligosaccharides with type 2 structure. Glycobiology 20 1402–1409. 10.1093/glycob/cwq101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrek S., Basu S., Harding M., White J. S., Bartick M. C., Rodriguez E., et al. (2017). Does breastfeeding duration decrease child obesity? an instrumental variables analysis. Pediatr. Obes. 12 304–311. 10.1111/ijpo.12143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller P. L., Jørgensen F., Hansen O. C., Madsen S. M., Stougaard P. (2001). Intra- and extracellular β-Galactosidases from Bifidobacterium bifidum and B. infantis: molecular cloning, Heterologous expression, and comparative characterization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 2276–2283. 10.1128/aem.67.5.2276-2283.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayfach S., Shi Z. J., Seshadri R., Pollard K. S., Kyrpides N. C. (2019). New insights from uncultivated genomes of the global human gut microbiome. Nature 568 505–510. 10.1038/s41586-019-1058-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto M., Kitaoka M. (2007). Identification of the putative proton donor residue of lacto-N-biose phosphorylase (EC 2.4.1.211). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71 1587–1591. 10.1271/bbb.70064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto M., Hidaka M., Nakajima M., Fushinobu S., Kitaoka M. (2012). Identification of amino acid residues that determine the substrate preference of 1,3-β-galactosyl-N-acetylhexosamine phosphorylase. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 74 97–102. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2011.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell Motherway M., Kinsella M., Fitzgerald G. F., Van Sinderen D. (2013). Transcriptional and functional characterization of genetic elements involved in galacto-oligosaccharide utilization by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Microb. Biotechnol. 6 67–79. 10.1111/1751-7915.12011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony S. M., Felice V. D., Nally K., Savignac H. M., Claesson M. J., Scully P., et al. (2014). Disturbance of the gut microbiota in early-life selectively affects visceral pain in adulthood without impacting cognitive or anxiety-related behaviors in male rats. Neuroscience 277 885–901. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parc A., Le, Karav S., Bell J. M., Frese S. A., Liu Y., et al. (2015). A novel endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase releases specific N-glycans depending on different reaction conditions. Biotechnol. Prog. 31 1323–1330. 10.1002/btpr.2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penders J., Thijs C., Vink C., Stelma F. F., Snijders B., Kummeling I., et al. (2006). Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics 118 511–521. 10.1542/peds.2005-2824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham V. T., Lacroix C., Braegger C. P., Chassard C. (2016). Early colonization of functional groups of microbes in the infant gut. Environ. Microbiol. 18 2246–2258. 10.1111/1462-2920.13316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokusaeva K., Fitzgerald G. F., Van Sinderen D. (2011). Carbohydrate metabolism in Bifidobacteria. Genes Nutr. 6 285–306. 10.1007/s12263-010-0206-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roduit C., Frei R., Ferstl R., Loeliger S., Westermann P., Rhyner C., et al. (2019). High levels of butyrate and propionate in early life are associated with protection against atopy. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 74 799–809. 10.1111/all.13660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruas-Madiedo P., Gueimonde M., Fernández-García M., De Los Reyes-Gavilán C. G., Margolles A. (2008). Mucin degradation by Bifidobacterium strains isolated from the human intestinal microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 1936–1940. 10.1128/aem.02509-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S. M., Fitzgerald G. F., Van Sinderen D. (2005). Transcriptional regulation and characterization of a novel-fructofuranosidase-encoding gene from bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 3475–3482. 10.1128/aem.71.7.3475-3482.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabater-Molina M., Larqué E., Torrella F., Zamora S. (2009). Dietary fructooligosaccharides and potential benefits on health. J. Physiol. Biochem. 65 315–328. 10.1007/bf03180584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakanaka M., Gotoh A., Yoshida K., Odamaki T., Koguchi H., Xiao J. Z., et al. (2020). Varied pathways of infant gut-associated Bifidobacterium to assimilate human milk oligosaccharides: prevalence of the gene set and its correlation with bifidobacteria-rich microbiota formation. Nutrients 12:71. 10.3390/nu12010071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurama H., Kiyohara M., Wada J., Honda Y., Yamaguchi M., Fukiya S., et al. (2013). Lacto-N-biosidase encoded by a novel gene of Bifidobacterium longum subspecies longum shows unique substrate specificity and requires a designated chaperone for its active expression. J. Biol. Chem. 288 25194–25206. 10.1074/jbc.m113.484733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salli K., Hirvonen J., Siitonen J., Ahonen I., Anglenius H., Maukonen J. (2021). Selective utilization of the human milk oligosaccharides 2′-Fucosyllactose, 3-Fucosyllactose, and difucosyllactose by various probiotic and pathogenic bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69 170–182. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell M. A., Karmirantzou M., Snel B., Vilanova D., Berger B., Pessi G., et al. (2002). The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 14422–14427. 10.1073/pnas.212527599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheneel-Brunner H., Chester M. A., Watkins W. M. (1972). a-L-Fucosyltransferases in human serum from donors of different ABO, secretor and lewis blood - group phenotypes. Eur. J. Biochem. 30 269–277. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb02095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab C., Ruscheweyh H.-J., Bunesova V., Pham V. T., Beerenwinkel N., Lacroix C. (2017). Trophic interactions of infant Bifidobacteria and Eubacterium hallii during L-fucose and Fucosyllactose degradation. Front. Microbiol. 8:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S., Friedberg I., Ivanov I. V., Davidson L. A., Goldsby J. S., Dahl D. B., et al. (2012). A metagenomic study of diet-dependent interaction between gut microbiota and host in infants reveals differences in immune response. Genome Biol. 13:R32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiertz A., Taras D., Schäfer K., Beijer S., Bos N. A., Donus C., et al. (2010). Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity 18 190–195. 10.1038/oby.2009.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela D. A., Garrido D., Lerno L., Wu S., Tan K., Eom H. J., et al. (2012). Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 α-fucosidases are active on fucosylated human milk oligosaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 795–803. 10.1128/aem.06762-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela D. A., Li Y., Lerno L., Wu S., Marcobal A. M., Bruce German J., et al. (2011). An infant-associated bacterial commensal utilizes breast milk sialyloligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 286 11909–11918. 10.1074/jbc.m110.193359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serino M., Nicolas S., Trabelsi M.-S., Burcelin R., Blasco-Baque V. (2017). Young microbes for adult obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 12 e28–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvers K. M., Frampton C. M., Wickens K., Pattemore P. K., Ingham T., Fishwick D., et al. (2012). Breastfeeding protects against current asthma up to 6 years of age. J. Pediatr. 160 991–996.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorour N. M., Tayel A. A., Abbas R. N., Abonama O. M. (2017). “Microbial biosynthesis of health-promoting food ingredients,” in Food Biosynthesis, eds Grumezescu A. M., Holban A. M. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 55–93. 10.1016/b978-0-12-811372-1.00002-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stark P. L., Lee A. (1982). The microbial ecology of the large bowel of breastfed and formula-fed infants during the first year of life. J. Med. Microbiol. 15 189–203. 10.1099/00222615-15-2-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. J., Ajami N. J., O’Brien J. L., Hutchinson D. S., Smith D. P., Wong M. C., et al. (2018). Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 562 583–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szentirmai É, Millican N. S., Massie A. R., Kapás L. (2019). Butyrate, a metabolite of intestinal bacteria, enhances sleep. Sci. Rep. 9:7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theurich M. A., Davanzo R., Busck-Rasmussen M., Díaz-Gómez N. M., Brennan C., Kylberg E., et al. (2019). Breastfeeding rates and programs in europe: a survey of 11 national breastfeeding committees and representatives. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 68 400–407. 10.1097/mpg.0000000000002234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongaram T., Hoeflinger J. L., Chow J. M., Miller M. J. (2017). Human milk oligosaccharide consumption by probiotic and human-associated bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. J. Dairy Sci. 100 7825–7833. 10.3168/jds.2017-12753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurl S., Munzert M., Henker J., Boehm G., Müller-Werner B., Jelinek J., et al. (2010). Variation of human milk oligosaccharides in relation to milk groups and lactational periods. Br. J. Nutr. 104 1261–1271. 10.1017/s0007114510002072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totten S. M., Zivkovic A. M., Wu S., Ngyuen U., Freeman S. L., Ruhaak L. R., et al. (2012). Comprehensive profiles of human milk oligosaccharides yield highly sensitive and specific markers for determining secretor status in lactating mothers. J. Proteome Res. 11 6124–6133. 10.1021/pr300769g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. H., Hart C. A., Rhodes J. M. (1991). Production of mucin degrading sulphatase and glycosidases by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 13 97–101. 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1991.tb00580.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turroni F., Milani C., Duranti S., Mancabelli L., Mangifesta M., Viappiani A., et al. (2016). Deciphering bifidobacterial-mediated metabolic interactions and their impact on gut microbiota by a multi-omics approach. ISME J. 10 1656–1668. 10.1038/ismej.2015.236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood M. A., Gaerlan S., De Leoz M. L. A., Dimapasoc L., Kalanetra K. M., Lemay D. G., et al. (2015). Human milk oligosaccharides in premature infants: absorption, excretion and influence on the intestinal microbiota. Pediatr. Res. 78 670–677. 10.1038/pr.2015.162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urashima T., Hirabayashi J., Sato S., Kobata A. (2017). Human milk oligosaccharides as essential tools for basic and application studies on Galectins. Trends Glycosci. Glycotechnol. 30 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- van der, Aa L. B., van Aalderen W. M. C., Heymans H. S. A., Henk Sillevis, Smitt J., et al. (2011). Synbiotics prevent asthma-like symptoms in infants with atopic dermatitis. Allergy 66 170–177. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02416.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venegas D. P., De La Fuente M. K., Landskron G., González M. J., Quera R., Dijkstra G., et al. (2019). Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front. Immunol. 10:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhnyatskaya S., Ferrari M., De Vos P., Walvoort M. T. C. (2019). Shaping the infant microbiome with non-digestible carbohydrates. Front. Microbiol. 10:343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viborg A. H., Katayama T., Hachem A. M., Andersen M. C., Nishimoto M., Clausen M. H., et al. (2014). Distinct substrate specificities of three glycoside hydrolase family 42 β-galactosidases from Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697. Glycobiology 24 208–216. 10.1093/glycob/cwt104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viverge D., Grimmonprez L., Cassanas G., Bardet L., Solere M. (1990). Discriminant carbohydrate components of human milk according to donor secretor types. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 11 365–370. 10.1097/00005176-199010000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada J., Ando T., Kiyohara M., Ashida H., Kitaoka M., Yamaguchi M., et al. (2008). Bifidobacterium bifidum lacto-N-biosidase, a critical enzyme for the degradation of human milk oligosaccharides with a type 1 structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 3996–4004. 10.1128/aem.00149-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol M., Perrin S., Grill J.-P., Schneider F. (2002). Characterization of a purified beta-fructofuranosidase from Bifidobacterium infantis ATCC 15697. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 35 462–467. 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2002.01224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund (2019). Global Breastfeeding Scorecard 2019: Increasing Commitment to Breastfeeding Through Funding and Improved Policies and Programmes. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Rebello O., Crost E. H., Owen C. D., Walpole S., Bennati-Granier C., et al. (2020). Fucosidases from the human gut symbiont Ruminococcus gnavus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78 675–693. 10.1007/s00018-020-03514-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Tao N., German J. B., Grimm R., Lebrilla C. B. (2010). Development of an annotated library of neutral human milk oligosaccharides. J. Proteome Res. 9 4138–4151. 10.1021/pr100362f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G., Davis J. C., Goonatilleke E., Smilowitz J. T., German J. B., Lebrilla C. B. (2017). Absolute quantitation of human milk oligosaccharides reveals phenotypic variations during lactation. J. Nutr. 147 117–124. 10.3945/jn.116.238279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Yang W., Wang Y., Wang M., Zhang M. (2020). Structural and biochemical analyses of β-N-acetylhexosaminidase Am0868 from akkermansia muciniphila involved in mucin degradation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 529 876–881. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.06.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M., Dehaas E., Kurmi O. P. (2019). Understanding the relationship between breastfeeding and childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 54:A4516. [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa M., Yorifuji T., Inoue S., Kato T., Doi H. (2013). Breastfeeding and obesity among schoolchildren: a nationwide longitudinal survey in Japan. JAMA Pediatr. 167 919–925. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Liu L., Zhu Y., Huang G., Wang P. P. (2014). The association between breastfeeding and childhood obesity: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 14:1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L., Das P., Li P., Ji B., Nielsen J. (2019). Carbohydrate active enzymes are affected by diet transition from milk to solid food in infant gut microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 95:fiz159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip S. P., Lai S. K., Wong M. L. (2007). Systematic sequence analysis of the human fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2) gene identifies novel sequence variations and alleles. Transfusion 47 1369–1380. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida E., Sakurama H., Kiyohara M., Nakajima M., Kitaoka M., Ashida H., et al. (2012). Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis uses two different β-galactosidases for selectively degrading type-1 and type-2 human milk oligosaccharides. Glycobiology 22 361–368. 10.1093/glycob/cwr116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z.-T., Chen C., Newburg D. S. (2013). Utilization of major fucosylated and sialylated human milk oligosaccharides by isolated human gut microbes. Glycobiology 23 1281–1292. 10.1093/glycob/cwt065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Yohe T., Huang L., Entwistle S., Wu P., Yang Z., et al. (2018). dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N., Gao Y., Zhu W., Meng D., Walker W. A. (2020). Short chain fatty acids produced by colonizing intestinal commensal bacterial interaction with expressed breast milk are anti-inflammatory in human immature enterocytes. PLoS One 15:e0229283. 10.1371/journal.pone.0229283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.