Abstract

Background

Middle-aged and older adults requiring skilled home healthcare (‘home health’) services following hospital discharge are at high risk of experiencing suboptimal outcomes. Information management (IM) needed to organise and communicate care plans is critical to ensure safety. Little is known about IM during this transition.

Objectives

(1) Describe the current IM process (activity goals, subactivities, information required, information sources/targets and modes of communication) from home health providers’ perspectives and (2) Identify IM-related process failures.

Methods

Multisite qualitative study. We performed semistructured interviews and direct observations with 33 home health administrative staff, 46 home health providers, 60 middle-aged and older adults, and 40 informal caregivers during the preadmission process and initial home visit. Data were analysed to generate themes and information flow diagrams.

Results

We identified four IM goals during the preadmission process: prepare referral document and inform agency; verify insurance; contact adult and review case to schedule visit. We identified four IM goals during the initial home visit: assess appropriateness and obtain consent; manage expectations; ensure safety and develop contingency plans. We identified IM-related process failures associated with each goal: home health providers and adults with too much information (information overload); home health providers without complete information (information underload); home health coordinators needing information from many places (information scatter); adults’ and informal caregivers’ mismatched expectations regarding home health services (information conflict) and home health providers encountering inaccurate information (erroneous information).

Conclusions

IM for hospital-to-home health transitions is complex, yet key for patient safety. Organisational infrastructure is needed to support IM. Future clinical workflows and health information technology should be designed to mitigate IM-related process failures to facilitate safer hospital-to-home health transitions.

INTRODUCTION

Problems during middle-aged and older adults’ care transitions are common, costly, dangerous and persistent despite two decades of patient safety research.1–4 In the USA, those who require skilled home healthcare (‘home health’) services (eg, nursing, rehabilitation therapy) following hospital discharge are among those at highest risk of experiencing suboptimal outcomes, including rehospitalisation.5–8 Seventeen per cent of US hospitalised older adults experience hospital-to-home health transitions.9 Although there are a variety of interventions to improve care transitions from hospital to home,10–14 these are not specific to hospital-to-home health transitions. Rehospitalisation rates among home health patients remain high,7,15–17 suggesting patient safety threats persist.

Information management (IM) refers to the ability of home health providers to collect, organise and communicate adults’ needs, status and care plans to key care providers during hospital-to-home health transitions. These include hospital-based healthcare professionals, patients and informal caregivers, home health providers, primary care providers, specialists and pharmacists. Most existing IM studies are limited to improving hospital-based processes and ignore the wider healthcare delivery ecosystem.18–27 Many patient safety issues occur after hospital discharge and are highly related to IM activities, including those related to home health.28

We sought to investigate IM during middle-aged and older adults’ (hereinafter referred to as ‘adults’) hospital-to-home health transitions. There is little understanding about IM-related process failures (information problems that may contribute to errors)29 related to suboptimal IM during transitions. IM-related process failures occur when IM fails to achieve its intended outcome. Understanding IM-related process failures faced by home health providers is important because of providers’ critical role in the postdischarge period,30 the importance of incorporating providers’ perspectives in creating a ‘shared view’ of care transitions3 and the high risk of adverse events during hospital-to-home health transitions.5

The objectives of this paper were to: (1) describe the current IM process in the context of the hospital-to-home health transition from home health providers’ perspectives and (2) identify IM-related process failures.

METHODS

Study design

This was a multisite qualitative study eliciting contextual factors influencing the quality of care during the hospital-to-home health transition—beginning with the home health preadmission process (from hospital referral to home visit scheduling) and ending with the initial home visit (~48 hours after hospital discharge). This period is the time when the adult is not yet under the direct care of a healthcare provider and may be at increased risk of adverse events.

We used the Information Chaos conceptual framework from Human Factors Engineering to guide our data collection and analyses. Human Factors Engineering studies the interactions among people and elements of their work system with the goal of optimising performance and reducing harm.31–38 The Information Chaos framework29 describes five IM-related process failures comprising information chaos (ie, confusion and disorganisation of information): information overload, underload, scatter, conflict and erroneous information.

Settings and participants

The study was conducted at five home health sites associated with three home health agencies across rural and urban sites in the USA (table 1). We recruited four types of participants most involved in executing hospital-to-home health transitions: home health administrative staff (hospital home health coordinators, intake staff, visit schedulers, clinical team managers, quality improvement officers, executive leadership), home health providers (nurses, rehabilitation therapists), adults aged 45 and older and informal caregivers (eg, friends or family).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating study sites

| Home health agency site | Home health agency ownership | Region | Average daily census | Average monthly admissions | Number of transitions observed (n=60) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Not-for-profit | Urban | 1977 | 1280 | 13 |

| 2 | Not-for-profit | Urban | 3229 | 2152 | 11 |

| 3 | For-profit | Rural | 98 | 28 | 8 |

| 4 | For-profit | Urban/suburban | 170 | 51 | 6 |

| 5 | Not-for-profit | Urban/suburban | 750 | 550 | 22 |

Data collection

Based on a combination of purposive and network sampling,39 we identified and interviewed home health administrative staff to better understand the unique processes and challenges of each study site.

Each home health agency would identify English-speaking or Spanish-speaking adults referred for home health services after hospital discharge, regardless of diagnosis. We approached adults either in-person before hospital discharge or by phone the day after hospital discharge. We obtained written consent from the home health provider assigned to visit the adult in the home and the adult (or the adult’s legally authorised representative, if applicable).

A geriatric medicine physician (AIA) and a human factors engineer (NEW) conducted direct observations of the home health preadmission process and initial home visit. As direct observers, the researchers did not participate in the activities taking place and remained as unobtrusive as possible (non-participant observation).40 Immediately following each home visit, researchers interviewed the adult, informal caregiver (interviewed at the same time as the adult) and home health provider. Interviews focused on key goals of, and barriers and facilitators to, successful IM during care transitions generally and during the most recent transition specifically. Interviews with participants lasted between 20 and 60 min, were audio recorded and transcribed. We transcribed observation notes electronically.

Data analyses

We analysed data from more than 180 hours of observation and 80 hours of interviews. To characterize IM goals, we used Human Factors Engineering methodology employed in our previous work,34 first performing content analysis of observation notes and interviews and then creating process-flow diagrams as a data representation approach, which we reviewed with home health subject matter experts.

We used an iterative approach to conduct content analysis and create our coding framework.41,42 Two researchers (AIA, AH) reviewed all transcripts and identified IM-related items. These items became the first-order codes in our framework and included terms, concepts and categories originating from the participants.43 Four researchers (AIA, AH, APG, BL) combined these codes into second-order codes representing IM goals and IM-related process failures. The two researchers (AIA, AH) reviewed all transcripts independently and identified emergent codes representing ideas not falling within our conceptual or coding frameworks. Because the research team developed the coding framework using a group consensus approach and discussed and reconciled coding differences by consensus,44 we did not compute inter-rater reliability. ATLAS. ti qualitative data management soft- ware facilitated analyses.45 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating site.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

table 1 summarises characteristics of participating study sites. Home health providers (n=46) had an average of 11.8 years of experience in the home health industry (range, 0.5–33 years). Home health providers were 69.6% nurses, 19.6% rehabilitation therapists and 8.6% administrators or home health coordinators. Home health administrative staff (n=33) had an average of 16.5 years of experience in the home care industry (range, 2–35 years). The average age of the adults (n=60) was 73.8 years (range, 48–98) and the informal caregivers (n=40) was 62.9 years (range, 21–87). Seven adults were Spanish-speaking (interviews conducted by AIA, a native Spanish speaker, using translated study materials).

The next sections describe IM goals and process failures during the two phases of the hospital-to-home health transition: home health preadmission process and initial home visit.

Home healthcare preadmission process

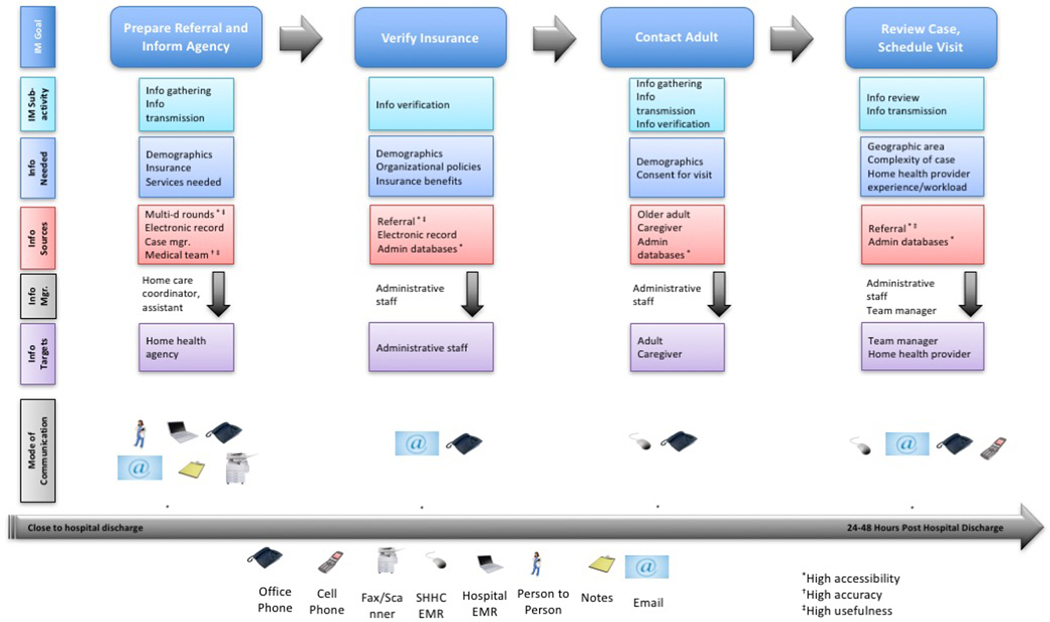

We identified four IM goals at all five sites: (1) prepare referral document and inform agency; (2) verify insurance; (3) contact adult and (4) review case to schedule visit. Figure 1 depicts the key IM goals during the home health preadmission process, information needed to meet each goal, primary information manager, information sources/targets for this information, principal modes of communicating the information and quality of the information gathered from information sources (see legend). table 2 summarises the IM-related process failure(s). table 3 contains representative quotes gathered during observations and interviews. Additional quotes are listed in online supplementary appendix A.

Figure 1.

Goals of information management during the home care preadmission process and quality of information gathered from information sources.

Table 2.

Overview of information management related activities during the preadmission process and initial home care visit

| Process failures→ | Information overload | Information underload | Information scatter | Information conflict | Erroneous information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information management goals during home health preadmission process/information manager(s) | |||||

| Prepare referral documentation and inform agency/home health coordinator | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Verify insurance/Administration staff | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Contact adult/Administrative staff | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Review case to schedule visit/Administrative staff, team manager | ✓ | ||||

| Information management goals during initial home visit/information manager(s) | |||||

| Assess appropriateness for home care and obtain consent for treatment/home health provider | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Manage expectations/home health provider | ✓ | ||||

| Ensure safety/home health provider | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Develop contingency plans and recovery scenarios/ home health provider | ✓ | ||||

All are employees of the home health agency.

Table 3.

Definitions of information management-related process failures during the hospital-to-home health transition

| Information management-related process failure | Definition | Related Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Information overload | Difficulty identifying relevant information among all of the information provided (eg, a medical record with too much detail). It becomes challenging to organise, synthesise, interpret or act on the information. | ‘Husband has binder given to

him by [discharging hospital] with a full summary of the rehab

hospitalization, labs, scripts, educational materials…Husband

says binder is overwhelming—he hasn’t had time to read

it…he is rifling thru all the papers to try and find

something in the binder that he can’t find about the meds.

Spends a long time on this.’ Excerpt from researcher field notes at Site 2. |

| Information underload | Information needed to perform a task ismissing (eg, key aspects of the medical history needed to implement care plan). |

‘We are sometimes seeing

inappropriate homecare referrals…the information that

we’re getting in terms of case referrals [documents]

sometimes is like five sentences, so you’re really not

getting a lot of information when you’re going into the

home…Basically, you’re going in there blind. You

don’t know even what [kind of diagnoses] you’re

seeing…’ Home health provider at Site 1. |

| Information scatter | Needed information is located in multiple places (eg, medical record, administrative databases, adult’s home, physician’s office). |

‘…[some information] is

not in the electronic medical [record]…you…go to the

[paper] chart…I also skim the physician’s orders and

make sure that the medications match up…, [I make sure to

check for other information]…that may have to be put on my

referral document that was not [told to me by the social

worker]…[The information needed is not in one

place]…you definitely search back and

forth…’ Home healthcare coordinator at Site 5 |

| Information conflict | Challenges determining which pieces of conflicting information are correct (eg, medication discrepancies). |

‘…[When I was in the

hospital]…the social worker said ‘you will get a home

health aide who can do laundry, do light shopping and light

cleaning.’…[and then I later] heard no…because

Medicare doesn’t pay for that.’ [Interviewer:]

‘It’s unfortunate …that you were told one thing

and then something else happened.’ ‘You only

learn…when these things happen to you, you

know.’ Patient from Site 2. |

| Erroneous information | Information that is wrong (eg, incorrect address, incorrect medication dose). |

‘…Some of the

information that we get on the referrals is incomplete, we sometimes

get information that according to the patient is completely

wrong… And if they don’t have the discharge papers,

it’s difficult to kind of

verify…’ Home health nurse from Site 1. |

Goal 1: prepare referral document and inform home health agency

Home health agencies employed home care coordinators to gather information and start developing a postdischarge care plan for inpatients referred to home health services. Their work occurred in the hospital. Home health agencies invested in this role because they needed someone to gather hospital-to-home health transition information into one place (figure 1, table 2).

Home care coordinators experienced information scatter while preparing the referral document, because they needed information from multiple sources using various modes of communication to prepare the referral and transmit it to the agency (table 3). There was information conflict to resolve, such as discrepancies between care plans in the electronic health record and those in the discharge instructions. Information in the electronic health record was often missing or inaccurate, and the healthcare team was not easily accessible for clarification.

Goal 2: verify insurance

Home health administrative staff used information from the referral document prepared by the coordinator and supplemented it with information from the electronic health record, if they had access to it, and from their own administrative databases. There was little or no face-to-face communication. Intake staff experienced information scatter and information conflict. For example, insurance benefit information was sometimes located in multiple databases with limited accessibility (information scatter). In addition, insurance information in the referral document was sometimes different from information in other databases (information conflict). Despite these challenges, the referral document remained the most accessible and useful source of information(figure 1, table 2).

Goal 3: contact adult

The goal of this subactivity was to initiate contact with the adult and obtain initial consent for a home health provider to visit the home. Administrative staff experienced information underload or information conflict, as the sources of information were not reliable. The adult’s or informal caregiver’s contact information may have been missing or did not match the information in the referral document. Additionally, the adult and their informal caregiver may have been difficult to contact (eg, not return phone calls) (figure 1, table 2).

Goal 4: review case and schedule visit

Schedulers (non-clinical personnel) assigned newly referred patients to a home health provider. Team managers were experienced former home health providers who supervised a group of providers assigned to a particular patient population or region. The team manager briefly reviewed the referral document and determined how quickly the home visit must be scheduled and which clinician could be assigned based on patient complexity, geographic area, provider’s experience and provider’s workload. The team manager might have ‘overridden’ a scheduler’s assignment of a patient to a home health provider, if the manager felt another provider would have been more appropriate (figure 1, table 2).

Administrative staff experienced information underload, when information regarding the care plan was missing or not comprehensive. For example, in an effort to streamline information transfer, some key information was lost (see representative quotes in online supplementary appendix A). Additionally, schedulers may not have been aware of home health provider workload when scheduling home visits and may have unduly burdened some staff.

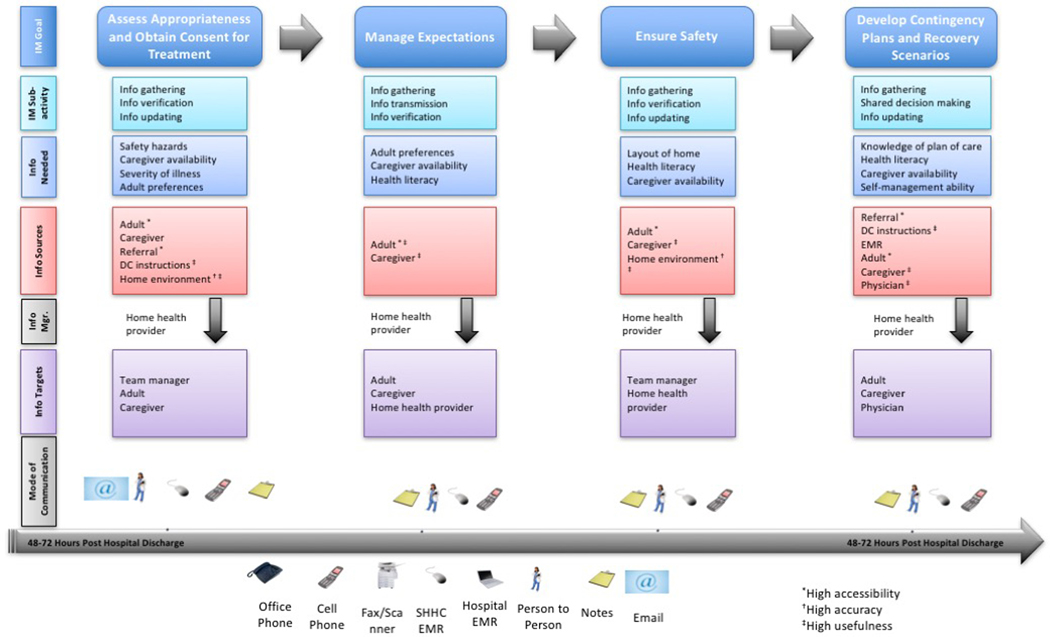

Initial home care visit

Figure 2 depicts the key IM goals and subactivities during the initial home visit. We identified four goals related to IM activities during the initial home visit: (1) assess appropriateness for home care and obtain consent for treatment; (2) manage expectations; (3) ensure safety and (4) develop contingency plans.

Figure 2.

Goals of information management during the initial home visit and quality of information gathered from information sources.

Goal 1: assess appropriateness for home care and obtain consent for treatment

The home health provider spent time right before and during the initial home visit to determine if home health services were appropriate for the patient. The adult must not be too complex to manage at home and not too well to negate the need for skilled services. The home health provider also identified whether there was an informal caregiver to assist with care plan implementation or whether the adult was able to self-manage their conditions. If the adult appeared appropriate for home health services, the home health provider obtained their written consent for treatment (figure 2, table 2).

Home health providers experienced information scatter while obtaining information from multiple sources (eg, referral document, hospital discharge paperwork, electronic health record, healthcare team, adult, informal caregiver and home environment). There was also conflicting or erroneous information, especially around medications. Medication lists taken from the hospital discharge paperwork often (>80% of the time) did not match the list of medications the adult was taking once they arrived at home (see online supplementary appendix B for photographs of an older adult’s bathroom demonstrating the complexity of sorting through medications). In addition, the adult and informal caregiver sometimes had conflicting opinions about the need for home health services or no longer wanted services once the adult was out of the hospital.

Finally, home health providers experienced information underload regarding care plan implementation. Hospital discharge instructions, if present, were not comprehensive, and hospital discharge summaries were typically not available at the time of the initial home visit. Adults and informal caregivers also experienced information underload, unless they had previous experience with receiving home care services. During the visit, the adult and informal caregiver were the most accessible source of information. The most useful sources of care plan information were the hospital discharge instructions (if available), and the home environment itself (home health provider could directly observe potential process failures, mitigating strategies and informal caregiver availability).

Goal 2: manage expectations

As the visit proceeded, the home health provider began to clarify what the adult could expect from home health services, the adult’s preferences and the ability of the informal caregiver to participate in care plan implementation. Information conflict was the main challenge, as there were often mismatched expectations (>80% of the time) on the part of the adult and informal caregiver regarding what services the home health agency would provide and what role(s) informal caregivers needed to take on. Most often, the adult and informal caregiver expected the home health provider to provide more services than were possible under the scope of their insurance benefits. However, in some instances, home health services exceeded adult or caregiver expectations (eg, an informal caregiver at one site was surprised to learn they could receive occupational therapy in the home). Clarifying conversations among the home health provider, adult and informal caregiver were the most useful means of resolving unmatched expectations (figure 2, table 2).

Goal 3: ensure safety

An important component of the visit was for the home health provider to ensure that the adult would be safe at home and there were available resources to carry out the care plan. As part of the safety assessment, the home health provider evaluated the home’s physical layout, adult and caregiver health literacy and the caregiver’s willingness and availability to assist with care plan implementation. There was potential for information scatter and information underload. Information scatter existed when the home health provider was at the same time evaluating the home and assessing the cognitive and functional abilities of the adult and caregiver and needing to do all of this by gathering information from scattered sources. Information underload often existed because the first visit did not provide a comprehensive view of the home situation. Nonetheless, the most accurate and useful information came from observation of family dynamics and an assessment of the home environment itself (figure 2, table 2).

Goal 4: develop contingency plan

The home health provider was the information manager to achieve this final IM goal during the initial home visit. Towards the end of the visit, after much information had been gathered, transmitted and verified, the home health provider created an initial care plan that included contingency plans for problems that could arise, such as the development of clinical symptoms. Adults and informal caregivers often felt information overload during the initial home visit, overwhelmed by educational materials and tasks to complete as part of the care plan. See online supplementary appendix C for a photograph of a strategy an informal caregiver used to help his legally blind father manage tasks. While contingency planning was intended to reduce anxiety, it sometimes increased anxiety in the short term, as adults and informal caregivers were asked to consider ‘worst-case scenarios’ and plan for events they had not anticipated (figure 2, table 2).

Characteristics common to both phases of the transition

We identified three characteristics common to both the home health preadmission process and the initial home visit. First, though the data we presented in figures 1 and 2 list each IM goal as occurring sequentially, the process was not always sequential. Second, there was variation across sites regarding who managed information for a particular IM goal, as some sites did not have coordinators. Third, several IM-related process failures could be present during each IM subactivity, and in some cases, process failures identified during one IM subactivity might lead to additional safety issues in later activities.

The initial home care visit was characterised by having one main information manager—the home health provider. The home health provider also was a key information target, meaning the provider was gathering information for themselves to use in the future. Serving as both the information manager and the target facilitated IM, allowing for complete tailoring of the information to the intended target, but may have also contributed to information overload.

DISCUSSION

In this multisite, qualitative study, we described the IM process and identified IM-related process failures during adults’ hospital-to-home health transitions. We found that IM was complex and involved coordinating information from multiple sources across settings and over time. IM required a high reliance on many information sources, managers and targets to reduce risk throughout the care transition. Despite this high reliance, the home health agency had little control over the accessibility, accuracy and usefulness of information from sources outside of the agency (eg, physicians, adults). Hence, suboptimal IM carried a significant risk of propagating IM-related process failures, unless there were systems to recognise and mitigate these failures. Study findings build on previous work34 demonstrating the complex workflow of home care coordinators and problems with information access as key challenges to optimal hospital-to-home health transitions. Study findings also extend our previous work46–48 and those of others30,38,49–51 identifying safety risks during hospital-to-home health transitions.

Second, we found variation across sites regarding who served as the information manager during the home health preadmission process. When home health agencies employed a home care coordinator to manage the care transition from the hospital, home health providers noted improved information quality, had more trust in the information and were more likely to receive information pertinent to the needs of the home health provider. This highlights the importance of aligning information managers’ perceived or actual motivations for completing IM tasks. Study findings also support designing interventions to bring hospital and home health staff together to understand each other’s work environments and information needs. These types of interventions could lead to effective system-level changes by redesigning information-sharing tools based on hospital and home health providers’ stated needs. Others have found a variety of unmet information needs in the home health setting postdischarge, including erroneous information and information overload.30 A study eliciting views of primary care physicians and home health providers found unclear definition of roles and responsibilities, care fragmentation and miscommunication among community health providers may contribute to rehospitalisation.49

Third, physicians were notably absent from the hospital-to-home health transition. Despite coordinators’ efforts to create accurate and useful referral documents, they had limited or no access to medical providers to clarify care plans. As a result, home health administrative staff scheduled initial home visits based on very limited clinical information. Home health providers, in turn, often did not have access to complete and correct information during the initial home visit. Neither hospital-based nor ambulatory care-based physicians were easily accessible to assist home health providers, adults and informal caregivers with contingency planning. Efforts to improve care transitions need to address the underlying reasons for physicians’ absence during the critical transition period, such as lack of awareness, accountability or reimbursement.

Fourth, it is critical to recognise the importance and potential negative impact of information overload on the safety of hospital-to-home health transitions. Adults and informal caregivers were especially susceptible to feeling overwhelmed when presented with information or asked to engage in contingency planning. Our study population was slightly younger than the home health population nationally.52 Cognitive impairment, fatigue, sleep deprivation, psychological distress and the effort of the sheer number of tasks they needed to complete after discharge compounded the overload. Providing more information and education may not be the most effective solution to empowering adults and informal caregivers during transitions. Information needs to be parsimonious and tailored to the ability of the recipients to receive and process the information. A review of regulatory requirements contributing to information overload should be undertaken.

Finally, organisational and technological infrastructure was not in place at the level of the hospital or home health agency to support IM during the hospital-to-home health transition. Our finding suggests home health staff needed integrated summaries of information in centralised locations to perform their tasks efficiently. Health information-technology systems were poorly designed to support the ‘realities’ of home health provider work over time and across healthcare settings. The referral document was an attempt to provide succinct information tailored to the needs of the home health agency. Home health agencies valued the information in the referral document so much that some agencies were willing to hire coordinators to be in charge of assessing referred patients and preparing the referral document. We found that coordinators employed by home health agencies transmitted information that home health providers felt was of higher quality and likely reduced the risk of IM-related process failures. Nonetheless, home health agencies expending significant energy to create tailored information summaries suggests the infrastructure to create these summaries was otherwise lacking. More research is needed on how to design underlying work system factors (information technology-related and others) to support interdependent work across healthcare settings.53

Our study had limitations. First, findings may not reflect the experiences of home health providers, adults or informal caregivers elsewhere. However, we chose study sites that varied based on the population they serve, ownership structure and affiliation with academic institutions. As this was a qualitative study, the focus was not on generalisability, but rather on transferability.54 Second, we focused on IM activities and IM-related process failures from the perspectives of home health providers. Other providers (eg, physicians) have little direct involvement in the execution of hospital-to-home health transitions. It is important to note that adults and caregivers were also information managers. The work of adults and informal caregivers could be the primary focus of future studies. Third, this study focused on the home health preadmission process and initial home visit, thus study findings do not reflect IM goals nor IM-related process failures present during other phases of the care transition (eg, hospital discharge, time after the initial home visit).

Our study had several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify key IM goals and IM-related process failures from the perspectives of home health providers executing adults’ transitions. Second, we used a Human Factors Engineering approach to study the hospital-to-home health IM process; Human Factors Engineering methods are well suited to evaluate contextual factors and understand interactions among stakeholders within and across care settings.36,53 Third, we obtained the perspectives of those most directly involved in hospital-to-home health transitions—home health providers—in order to have a comprehensive view and to give voice to those not well represented in the medical literature.

Implications

Understanding the nature of IM-related process failures can guide the development of interventions to support IM during transitions and improve patient safety. For example, interventions could promote standardisation of information transfer protocols to reduce information scatter, support situational awareness and foster collaborative IM practices.55,56 The use of dashboards has been useful to capture, synthesise and disseminate information in real time and could be used during care transitions.57,58 Home health/hospital team meetings could reduce the occurrence of information conflict, underload and erroneous information.55,59 Finally, creating programmes that facilitate alignment of incentives across the entire continuum of care could support best practices. For example, helping home health and hospital teams get to know each other as ‘senders and receivers’47,60 may create behavioural incentives to improve IM.

CONCLUSION

IM during hospital-to-home health transitions is complex. Future studies could examine barriers leading to IM-related process failures relating to the index hospitalisation or the type of home health service provided. Studies could also examine contextual factors in the work system, such as patterns of barrier propagation, outcomes resulting from suboptimal IM and ideas for design implications to support collaborative IM during care transitions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding This study was funded by Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Scholar grant (grant number: KL2TR001077), National Patient Safety Foundation and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1K08HS022916).

Footnotes

Disclaimer AIA affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Ethics approval Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman EA, Boult C. American Geriatrics Society Health Care Systems C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:556–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, et al. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1842–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutton E, Dixon-Woods M, Tarrant C. Ethnographic process evaluation of a quality improvement project to improve transitions of care for older people. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbaje AI, Kansagara DL, Salanitro AH, et al. Regardless of age: Incorporating principles from geriatric medicine to improve care transitions for patients with complex needs. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:932–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murtaugh CM, Litke A. Transitions through postacute and long-term care settings: patterns of use and outcomes for a national cohort of elders. Med Care 2002;40:227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolff JL, Meadow A, Weiss CO, et al. Medicare home health patients’ transitions through acute and post-acute care settings. Med Care 2008;46:1188–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosati RJ, Huang L. Development and testing of an analytic model to identify home healthcare patients at risk for a hospitalization within the first 60 days of care. Home Health Care Serv Q 2007;26:21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sears NA, Blais R, Spinks M, et al. Associations between patient factors and adverse events in the home care setting: a secondary data analysis of two canadian adverse event studies. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Medicare’s post-acute care: Trends and ways to rationalize payments. In: Report to the congress: medicare payment policy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999;281:613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbaje AI, Maron DD, Yu Q, et al. The geriatric floating interdisciplinary transition team. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:460–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madigan EA, Gordon NH, Fortinsky RH, et al. Rehospitalization in a national population of home health care patients with heart failure. Health Serv Res 2012;47:2316–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson MA, Hanson KS, DeVilder NW, et al. Hospital readmissions during home care: a pilot study. J Community Health Nurs 1996;13:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashton CM, Petersen NJ, Souchek J, et al. Geographic variations in utilization rates in Veterans Affairs hospitals and clinics. N Engl J Med 1999;340:32–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry D, Costanzo DM, Elliott B, et al. Preventing avoidable hospitalizations. Home Healthc Nurse 2011;29:540–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalista T, Lemay V, Cohen L. Postdischarge community pharmacist-provided home services for patients after hospitalization for heart failure. J Am Pharm Assoc 2015;55:438–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markley J, Sabharwal K, Wang Z, et al. A community-wide quality improvement project on patient care transitions reduces 30-day hospital readmissions from home health agencies. Home Healthc Nurse 2012;30:E1–E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corbett CF, Setter SM, Daratha KB, et al. Nurse identified hospital to home medication discrepancies: implications for improving transitional care. Geriatr Nurs 2010;31:188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cegarra-Navarro JG, Wensley AKP, Sánchez-Polo MT. Improving quality of service of home healthcare units with health information technologies. Health Information Management Journal 2011;40:30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albrecht JS, Gruber-Baldini AL, Hirshon JM, et al. Hospital discharge instructions: comprehension and compliance among older adults. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1491–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrne K, Orange JB, Ward-Griffin C. Care transition experiences of spousal caregivers: from a geriatric rehabilitation unit to home. Qual Health Res 2011;21:1371–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giosa JL, Stolee P, Dupuis SL, et al. An examination of family caregiver experiences during care transitions of older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement 2014;33:137–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lattimer C. Practices to improve transitions of care: a national perspective. North Carolina medical journal 2012;73:45–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy MC, Jansen BJ. A model for understanding collaborative information behavior in context: A study of two healthcare teams. Inf Process Manag 2008;44:256–73. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, et al. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:646–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beasley JW, Wetterneck TB, Temte J, et al. Information chaos in primary care: implications for physician performance and patient safety. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 2011;24:745–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romagnoli KM, Handler SM, Ligons FM, et al. Homecare nurses’ perceptions of unmet information needs and communication difficulties of older patients in the immediate post-hospital discharge period. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:324–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurses AP, Ozok AA, Pronovost PJ. Time to accelerate integration of human factors and ergonomics in patient safety: Table 1. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carayon P, ed. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety. Second ed. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, et al. Human factors systems approach to healthcare quality and patient safety. Appl Ergon 2014;45:14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nasarwanji M, Werner NE, Carl K, et al. Identifying challenges associated with the care transition workflow from hospital to skilled home health care: perspectives of home health care agency providers. Home Health Care Serv Q 2015;34(3–4):185–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arbaje AI, Kansagara DL, Salanitro AH, et al. Regardless of age: incorporating principles from geriatric medicine to improve care transitions for patients with complex needs. J Gen Intern Med 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werner NE, Gurses AP, Leff B, et al. Improving care transitions across healthcare settings through a human factors approach. J Healthc Qual 2016;38:328–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The National Academies Press. Health Care Comes Home: The Human Factors. Washington, DC, 2011:200. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ck O, Valdez RS, Casper GR, et al. Human factors and ergonomics in home care: Current concerns and future considerations for health information technology. Work 2009;33:201–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. Second edn. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flick U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 310. Second ed. London: SAGE Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.López A, Detz A, Ratanawongsa N, et al. What patients say about their doctors online: a qualitative content analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:685–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vashi A, Rhodes KV. “Sign Right Here and You’re Good to Go”: a content analysis of audiotaped emergency department discharge instructions. Ann Emerg Med 2011;57:315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saldana J. An Introduction to Codes and Coding. In: The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Third Edn. Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing, 2016:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1758–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anon. GmbH AtSSD ATL AS. ti: The Knowledge Workbench. In:, ed. 6.2 edn. Berlin, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller SC, Gurses AP, Werner N, et al. Older adults and management of medical devices in the home: five requirements for appropriate use. Popul Health Manag 2017;20:278–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schoenborn NL, Arbaje AI, Eubank KJ, et al. Clinician roles and responsibilities during care transitions of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:231–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arbaje AI, Newcomer AR, Maynor KA, et al. Excellence in transitional care of older adults and pay-for-performance: perspectives of health care professionals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2014;40:550–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shih AF, Buurman BM, Tynan-McKiernan K, et al. Views of primary care physicians and home care nurses on the causes of readmission of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2193–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaidya SR, Shapiro JS, Papa AV, et al. Perceptions of health information exchange in home healthcare. Comput Inform Nurs 2012;30:503–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brody AA, Gibson B, Tresner-Kirsch D, et al. High prevalence of medication discrepancies between home health referrals and centers for medicare and medicaid services home health certification and plan of care and their potential to affect safety of vulnerable elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:e166–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-Term care providers and services users in the United States: data from the national study of long-term care providers, 2013–2014. Vital Health Stat 3 2016;3:1–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Werner NE, Malkana S, Gurses AP, et al. Toward a process-level view of distributed healthcare tasks: Medication management as a case study. Appl Ergon 2017;65:255–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gittell JH. Organizing work to support relational coordination. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2000;11:517–39. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hansen P, Järvelin K. Collaborative information retrieval in an information-intensive domain. Inf Process Manag 2005;41:1101–19. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosow E, Adam J, Coulombe K, et al. Virtual instrumentation and real-time executive dashboards. Solutions for health care systems. Nurs Adm Q 2003;27:58–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wears RL, Perry SJ, Wilson S, et al. Emergency department status boards: user-evolved artefacts for inter- and intra-group coordination. Cogn Technol Work 2007;9:163–70. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoffer Gittell J, Gittell JH. Coordinating mechanisms in care provider groups: relational coordination as a mediator and input uncertainty as a moderator of performance effects. Manage Sci 2002;48:1408–26. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Campbell DA, Thompson M. Patient safety rounds: description of an inexpensive but important strategy to improve the safety culture. American Journal of Medical Quality 2007;22:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.