Abstract

Background

Characterizing the kinetics of the antibody response to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) is of critical importance to developing strategies that may mitigate the public health burden of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). We conducted a prospective, longitudinal analysis of COVID-19 convalescent plasma donors at multiple time points over an 11-month period to determine how circulating antibody levels change over time following natural infection.

Methods

From April 2020 to February 2021, we enrolled 228 donors. At each study visit, subjects either donated plasma or had study samples drawn only. Anti–SARS-CoV-2 donor testing was performed using the VITROS Anti–SARS-CoV-2 Total and IgG assays and an in-house fluorescence reduction neutralization assay.

Results

Anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were identified in 97% of COVID-19 convalescent donors at initial presentation. In follow-up analyses, of 116 donors presenting at repeat time points, 91.4% had detectable IgG levels up to 11 months after symptom recovery, while 63% had detectable neutralizing titers; however, 25% of donors had neutralizing levels that dropped to an undetectable titer over time.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that immunological memory is acquired in most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 and is sustained in a majority of patients for up to 11 months after recovery.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT04360278.

Keywords: convalescent plasma, COVID-19, immunological memory, neutralizing, serology

A longitudinal serological study of 228 convalescent plasma donors showed that immunological memory is acquired in most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 and is sustained in a majority of patients for up to 11 months after recovery.

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), constitutes a global health crisis with devastating social and economic consequences. As efforts are underway to curtail further spread of COVID-19 worldwide, it is critical to understand the longevity and potency of immune response to SARS‐CoV‐2. Antibody production represents a significant component of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2, and serologic assays to detect circulating antibody levels are a readily available tool in clinical laboratory settings for tracking immune responses over time [1, 2].

Due to the recent emergence of this infectious disease, there is a relative paucity of data on the long-term kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Studies of individuals who have recovered from natural infection may help to determine how long antibodies persist after an immunizing exposure, and whether or not these antibodies might protect against reinfection. The persistence of antibody response may also help predict the efficacy of vaccines for COVID‐19.

COVID-19 convalescent plasma (CCP) is an investigational therapy that remains somewhat controversial, with conflicting reports of efficacy [3–5]. The underlying principle of this treatment approach is the passive transfer of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies to patients with COVID-19. Serologic assays therefore play a critical role in identifying suitable convalescent plasma donors and provide evidence of humoral immunity against SARS-CoV-2.

Importantly, as CCP donors may return for multiple repeat donations, these individuals provide a valuable opportunity to characterize anti–SARS-CoV-2 serologic responses and to determine how circulating antibody levels change over time in a well-defined cohort [6].

Of the four major structural proteins for SARS-Co-V2, spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, the S and the N proteins are both highly immunogenic and abundantly expressed during the infection [7]. They have been used as target antigens for the majority of serological assays. The S glycoprotein, however, is surface-exposed and mediates entry into host cells. As such it is subject to a more stringent selection pressure from the immune system and, for this reason, it represents the main target of neutralizing antibodies [8].

In the current study, we prospectively conducted a longitudinal serological assessment of CCP donors after recovery from natural infection. Donors were assessed for levels of neutralizing antibodies as well as total and immunoglobulin G (IgG)-specific S protein antibodies using a laboratory-developed fluorescence reduction neutralization assay (FRNA) and a commercially available system (Ortho VITROS). Data were analyzed to identify correlations between antibody levels and clinical characteristics, and we present follow-up serological data in repeat CCP donors. Collectively, we present a comprehensive view of SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics over an 11-month period after natural infection, increasing our understanding of COVID-19 immune responses among persons with community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection.

METHODS

CCP Donor Qualification and Plasma Collection

CCP donors were prospectively enrolled onto an institutional review board-approved protocol (Clinical Trials Registration, NCT04360278) and provided written informed consent for the study. Eligibility criteria included (1) routine blood donor criteria, (2) molecular or serologic laboratory evidence of past COVID-19 infection, and (3) complete recovery from COVID-19, with no symptoms for ≥28 days or ≥14 days with a negative molecular test after recovery.

We collected donor demographic and biometric data, including age, race, sex, and body mass index (BMI). We categorized clinical severity of past COVID-19 infection as asymptomatic, mild (self-limiting course, symptomatic management at home), moderate (emergency room management or hospitalization), or severe (intensive care unit [ICU] admission). Depending on center-specific logistics and changes in demand for convalescent plasma, at each study visit, subjects either donated plasma or only had whole blood samples drawn for research; in all cases, anti–SARS-CoV-2 testing was performed. Based on the results of the previous visit, donors were recruited to either continue donating plasma or donate samples for research purposes. Plasma collections were performed by apheresis, yielding 600–825 mL of donor plasma. Sample draws were limited to <70 mL of whole blood per visit. The minimum interval between plasma donations was 28 days; shorter intervals were acceptable between sample draw visits. Routine plasma donor testing was performed, including standard infectious disease testing, blood group assessment, and HLA antibody testing in female donors.

Plasma for anti–SARS-CoV-2 testing was isolated from EDTA-anticoagulated human whole blood samples. Samples were processed immediately after collection, centrifuged for 15 minutes at 2500 rpm to separate the plasma phase. The upper plasma layer was extracted, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C in our research repository after antibody testing, and then shipped on dry ice to the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick, MD for the in-house assessment of the sample’s SARS-CoV-2 neutralization activity.

Prior to August 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended titers of at least 1:160 for investigational convalescent plasma, but a titer of 1:80 was considered acceptable if higher-titer units were not available. In August 2020, the FDA granted CCP emergency use authorization; the criteria for high-titer CCP have subsequently been revised several times.

SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassay

Donor samples were tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies using the Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics VITROS Total (IgA/G/M) and IgG COVID-19 Antibody tests following the manufacturer’s package insert instructions [9]. Both assays have been granted emergency use authorization by the FDA. The Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics anti–SARS-CoV-2 assay is a qualitative chemiluminescence immunoassay (ChLIA) utilizing luminol-horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-mediated chemiluminescence assay, performed on the VITROS 3600 automated immunoassay analyzer. The assay involved a 2-stage reaction. In the first stage, antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 present in the sample bound with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein coated on wells. Any unbound sample was removed by washing. In the second stage, HRP-labeled murine monoclonal anti-human IgG antibodies (or recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 antigen for the total assay) were added in the conjugate reagent. The conjugate bound specifically to the antibody portion of the antigen-antibody complex. If complexes were not present, the unbound conjugate was removed by the subsequent washing step. The HRP in the bound conjugate catalyzed oxidation of the luminol, which produced a chemiluminescent reaction measured by a luminometer. The patient sample signal was divided by the calibrator signal, with the resulting signal/cutoff (S/Co) values of <1.00 and ≥1.00 corresponding to nonreactive and reactive results, respectively.

SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Assay

Assays for determining neutralizing titers were performed with authentic SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV/USA-WA1-A12/2020 from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) at the NIH-NIAID Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick, MD, using a FRNA as described by Holbrook et al [10]. All data were analyzed using Excel. To detect potential experimental errors, we used Dixon Q-test, a quick statistical method to detect gross errors in small samples. We used the critical value of 0.829 for 95% confidence level at n = 4 [11, 12].

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.4.3. Relationship between multiple groups were examined using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, with post hoc comparisons calculated using Dunn multiple comparison test. US population demographic data for age and sex were obtained from the 2019 US Census Bureau survey [13]. Blood type frequencies were obtained from Garratty et al [14].

RESULTS

COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Donor Characteristics

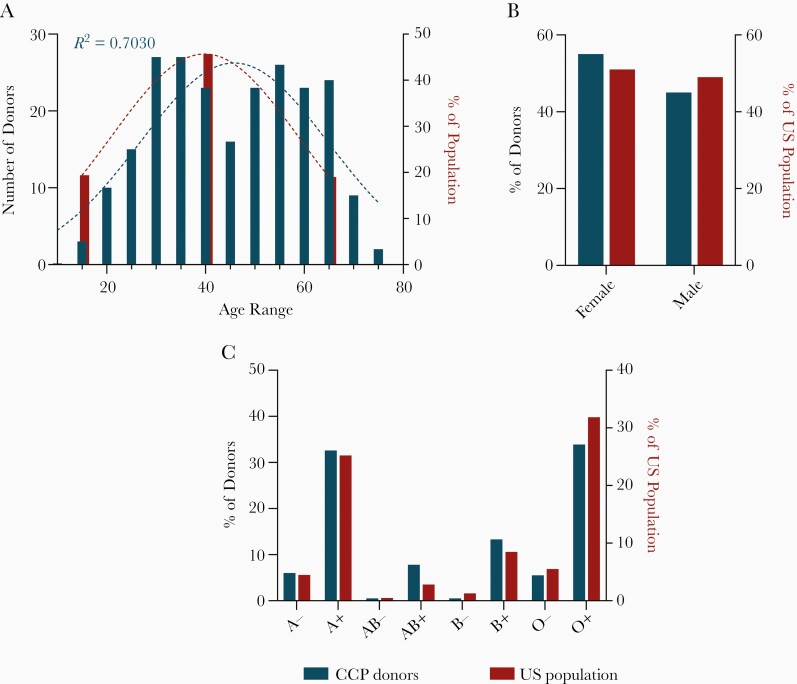

We enrolled 228 CCP donors between April 2020 and February of 2021. The median age of the cohort was 47 (18–79) years; 54.8% of donors were female. The distribution of donor ABO/Rh blood groups was as follow: A+ (31.1%), A− (5.7%), AB+ (7.5%), AB− (0.4%), B+ (12.7%), B− (0.4%), O+ (32.5%), and O− (5.3%), which was not statistically different from the US general population (Figure 1A–1C). HLA antibodies were found in 24% of women. The overwhelming majority of donors reported a mild disease course (205, 89.9%). Most donors self-identified as white (75.9%), Asian (8.3%), black (6.1%), or Hispanic (3.9%). Additional CCP donor characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 convalescent plasma donor characteristics. A, Age distribution of COVID-19 convalescent plasma (CCP) donors (blue; n = 228) relative to the US population (red). Dotted lines represent a Gaussian distribution and the coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated for the CCP goodness of fit. B, Sex distribution of CCP donors (blue; n = 228) relative to the US population (red). Binomial test was not significant relative to the US population. C, Blood type distribution of CCP donors (blue; n = 218) relative to the US population (red). Binomial tests performed relative to US population, all comparisons were not significant following Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 1.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Convalescent Plasma Donor Characteristics

| Characteristic | All Donors (n = 228) | Repeat Donors (n = 116) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 125 (54.8) | 64 (55.1) |

| Male | 103 (45.2) | 52 (44.9) |

| Disease course | ||

| Asymptomatic | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1.7) |

| Mild | 205 (89.9) | 103 (88.8) |

| Moderate | 16 (7.0) | 9 (7.8) |

| Severe | 3 (1.3) | 2 (1.7) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 19 (8.3) | 8 (6.9) |

| Black | 14 (6.1) | 4 (3.4) |

| White | 173 (75.9) | 88 (75.9) |

| Hispanic | 9 (3.9) | 8 (6.9) |

| Mixed race | 7 (3.1) | 4 (3.4) |

| Other/unknown | 4 (1.8) | 3 (2.6) |

| Declined | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) |

| Blood type | ||

| A− | 13 (5.7) | 8 (6.9) |

| A+ | 71 (31.1) | 36 (31.0) |

| AB− | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| AB+ | 17 (7.5) | 8 (6.9) |

| B− | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| B+ | 29 (12.7) | 16 (13.8) |

| O− | 12 (5.3) | 5 (4.3) |

| O+ | 74 (32.5) | 41 (35.3) |

| Unknown | 10 (4.4) | … |

| HLA status in women | ||

| Negative | 91 (72.8) | 49 (76.6) |

| Positive | 30 (24.0) | 14 (21.9) |

| Unknown | 4 (3.2) | 1 (1.5) |

| Age, y, median (range) | 47 (18–79) | 50.5 (19–79) |

| BMI, median (range) | 26.1 (17.9–51.8) | 26.1 (17.9–51.8) |

| Days after symptom resolution, median (range) | ||

| 1st donation | 47.5 (18–315) | 42.5 (18–244) |

| 2nd donation | … | 105 (53–321) |

| 3rd donation | … | 159 (88–322) |

| 4th donation | … | 196 (122–308) |

| 5th donation | … | 208.5 (157–302) |

| 6th donation | … | 243 (187–272) |

| 7th donation | … | 241 (216–315) |

| 8th donations | … | 273.5 (256–291) |

| 9th donations | … | 285 |

| Final donation | … | 196 (57–322) |

| Days between donations, median (range) | ||

| Consecutive donations | … | 44.5 (12–293) |

| 1st and final donation | … | 109.5 (21–293) |

| No. of donations | ||

| 2 | … | 44 (37.9) |

| 3 | … | 27 (23.3) |

| 4 | … | 23 (19.8) |

| 5 | … | 10 (8.6) |

| 6 | … | 8 (6.9) |

| 7 | … | 2 (1.7) |

| 8 | … | 1 (0.9) |

| 9 | … | 1 (0.9) |

Data are No. (%) except where indicated.

Disease course was categorized as asymptomatic, mild (self-limiting course, symptomatic management at home), moderate (emergency room management or hospitalization), and severe (intensive care unit admission).

SARS-CoV-2 Seroconversion and Neutralizing Activity at Initial Presentation

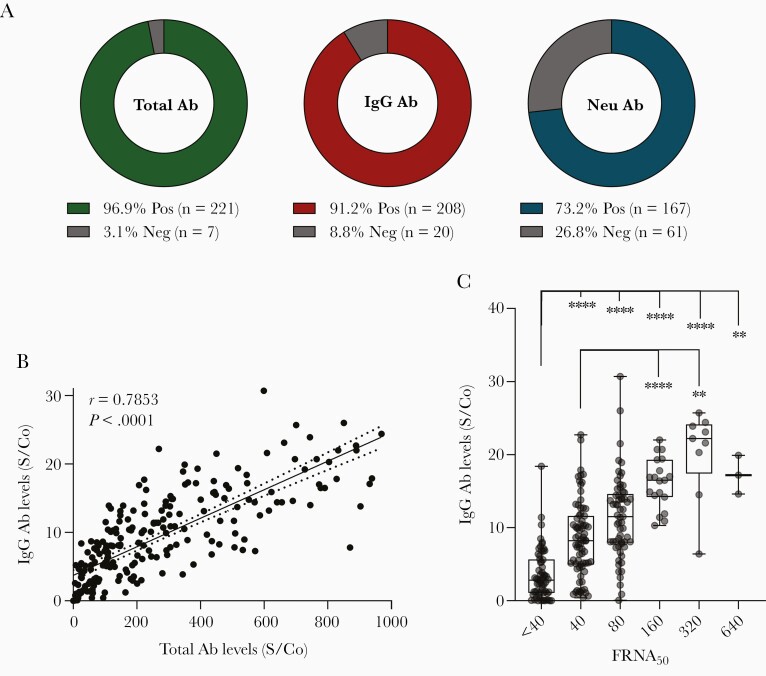

At the first study visit, donors presented at a median of 47.5 (18–315) days after symptom resolution. Total SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were detected in 96.9% of donors (221/228) and IgG antibodies were detected in 91.2% of donors (208/228) (Figure 2A). The median S/Co values of CCP plasma samples using the Ortho total Ab and Ortho IgG assay were 186 (S/Co 0.1–969) and 8.1 (S/Co 0.01–30.7), respectively. In 44.3% (101/228) of the donors, IgG antibody levels at initial presentation met the current FDA EUA high titer criterion of S/Co ≥9.5 when tested with IgG VITROS.

Figure 2.

SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion and neutralizing activity at initial donation. A, Percent of CCP donors testing positive or negative for the presence of total Ab, IgG Ab, or neutralizing Ab. B, Correlation of total antibody levels with IgG antibody levels (n = 228). Line represents a linear fit of the data including 95% confidence interval (dotted lines). Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is displayed along with P value. C, Distribution of IgG antibody levels based on FRNA50 neutralizing antibody titers (n = 228). Boxplots indicate median value with 1st and 3rd quartiles, and bars span minimum and maximum values. Individual patient values are indicated by dots. A statistically significant difference between groups was determined via Kruskal-Wallis test (P value < .0001). Post hoc comparisons were calculated using Dunn multiple comparison test, with significant pairwise comparisons indicated on the graph. * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001, **** P < .0001. Abbreviations: Ab, antibodies; CCP, COVID-19 convalescent plasma; FRNA50, fluorescence reduction neutralization assay at 50% reduction; IgG, immunoglobulin G; Neg, negative; Neu, neutralizing; Pos, positive; S/Co, signal to cutoff ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Total SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels were strongly correlated with IgG antibody levels (r = 0.7853, P = <.0001) (Figure 2B). Neutralizing activity as measured by FRNA50 was observed in 73.2% of samples (167/228) (Figure 2A). The majority of donors 136 (59.6%) had relatively modest neutralizing activity (FRNA50 titer ≤1:80). Specifically, 75 (32.9%) had an FRNA50 titer of <1:80, and 61 (26.8%) donors had a titer of 1:80, which prior to August 2020 was the minimum acceptable neutralizing antibody titer for CCP per FDA recommendations. A small proportion of CCP donors had higher neutralizing activity (FRNA50 titer >1:80), 19 (8.3%) had an FRNA50 titer of 1:160, 9 (3.9%) had a titer of 1:320, and 3 (1.3%) had a titer of 1:640. In our cohort, a statistically significant difference in mean IgG levels among neutralizing titer groups was observed (Kruskal-Wallis test; H (5) = 106.1, P = <.0001). Specifically, average IgG antibody levels were significantly greater in samples with high FRNA50 titer (1:80 or higher) than in low-titer samples (<1:80) (Figure 2C), suggesting a positive correlation between IgG antibodies and SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing activity. We observed weak correlations between total antibody levels or IgG antibody levels and duration of convalescence (expressed as days after symptom resolution). Specifically, over time, total antibodies displayed a weak but significant positive correlation (r = 0.2144, P = .0012), while IgG antibodies displayed a weak negative correlation of significance (r = −0.1612, P = .0157) (Supplementary Figure 1A). A statistically significant difference in mean days after symptom resolution and neutralizing titer was observed (Kruskal-Wallis test; H (5) = 24.00, P = .0002), with post hoc pairwise comparisons suggesting a negative correlation between the 2 (Supplementary Figure 1B).

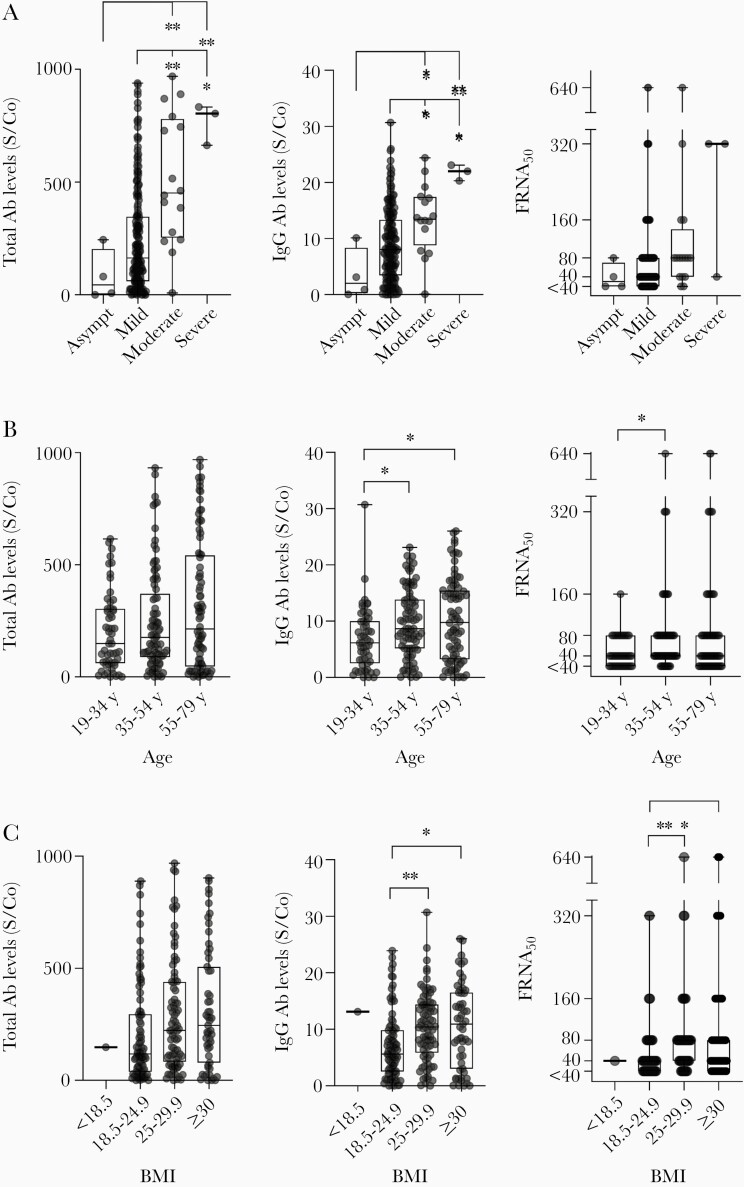

Correlation of CCP Donor Serology Tests and Neutralizing Activity With Clinical Characteristics

A severe clinical COVID-19 course requiring ICU admission, was associated with increased levels of total and IgG antibodies at initial presentation (P < .0001 and P = .0003, respectively). There was a statistical significance association between COVID-19 disease severity and neutralizing antibody titer (P = .0224) (Figure 3A). Increased IgG antibody levels and neutralizing titers were associated with both increased donor age (P = .0073 and P = .0191, respectively) and BMI (P = .0006 and P = .0012, respectively) (Figure 3B and 3C). We observed no associations between total antibody levels, IgG levels, or neutralizing antibody titers and sex, HLA status in women, blood type, or race (Supplementary Figure 1C–1F).

Figure 3.

Correlation of serology tests and neutralizing activity with clinical characteristics. Total antibody levels, IgG antibody levels, and neutralizing antibody titers (FRNA50) in CCP donors are shown based on (A) clinical disease course (asymptomatic, n = 4; mild, n = 205; moderate, n = 16; severe, n = 3); (B) donor age (19–34 years, n = 55; 35–54 years, n = 89; 55–79 years, n = 84); and (C) donor BMI (<18.5, n = 1; 18.5–24.9, n = 87; 25–29.9, n = 84; ≥30, n = 55; missing data for n = 1 donor). For all graphs, boxplots display the median with 1st and 3rd quartiles, and bars span minimum and maximum values. Individual patient values are indicated by dots. Statistically significant differences between groups were determined via Kruskal-Wallis test (A) for total Ab levels and IgG Ab levels based on disease course (P = <.0001 and .0003, respectively); (B) for IgG Ab levels and neutralizing titers based on age (P value = .0073 and .0191, respectively); and (C) for IgG Ab levels and neutralizing titers based on BMI (P value = .0006 and .0012, respectively). Post hoc comparisons were calculated using Dunn multiple comparison test, with significant pairwise comparisons indicated on graphs. * P < .05, ** P < .01. Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Asympt, asymptomatic; BMI, body mass index; CCP, COVID-19 convalescent plasma; FRNA50, fluorescence reduction neutralization assay at 50% reduction; IgG, immunoglobulin G; S/Co, signal to cutoff ratio.

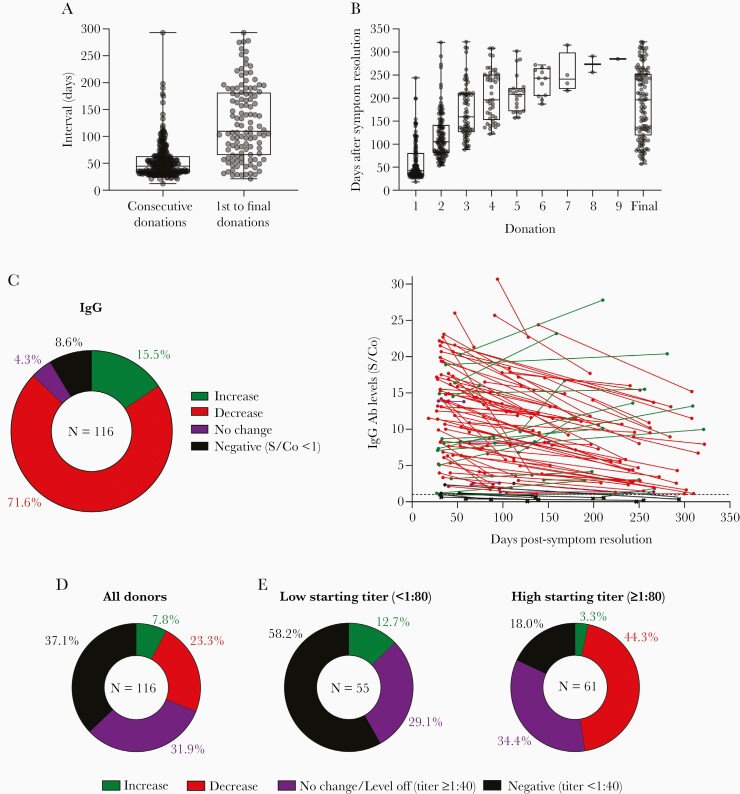

SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Levels in CCP Donors Over Time

In total, 116/228 (51%) plasma donors returned for repeat study visits, allowing for IgG and neutralizing antibody analyses at multiple time points. Repeat donor demographics were similar to our overall cohort. Most repeat donors presented 2 (37.9%) or 3 (23.3%) times, 38.8% (n = 45/116) presented for 4 or more study visits (Table 1). The median interval between consecutive visits was 44.5 (12–293) days and between the first and final visit was 109.5 (21–293) days (Figure 4A). Across all repeat donors, the first visit time point occurred at a median of 42.5 (18–244) days after symptom resolution, and the final time point occurred at a median of 196 (57–322) days after symptom resolution (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels in CCP donors over time. A, Boxplots indicate the interval between consecutive donations and between first and final donation. B, Boxplots display median number of days after symptom resolution at indicated donations. A and B, Boxplots indicate median value with 1st and 3rd quartiles, and bars span minimum and maximum values. Individual patient values indicated by dots. C, IgG antibody outcomes over time for repeat CCP donors are quantified in the pie chart, and individual antibody levels are plotted relative to days after symptom resolution (n = 114; n = 2 asymptomatic donors not plotted). Only first and last CCP donation values are plotted. Samples from the same donor connected by lines. Colors indicate antibody level outcomes over time: increase (green), decrease (red), no change (percent change <1%; purple), and negative (levels consistently below or falling below cutoff threshold S/Co < 1; black). The S/Co threshold of 1 indicated by the dashed line. Values below this threshold are represented by an “x.” D, Neutralizing titer outcomes over time for repeat CCP donors are quantified. Outcome categories are the same as in (C) except no change/level off indicates donors whose titers remained unchanged or leveled off to a detectable titer (≥1:40) for their last 2 or more donations, and negative indicates donors with consistently undetectable activity or whose titers fell to an undetectable level (<1:40). E, Outcomes from (D) stratified based on the titer at first donation. Abbreviations: CCP, COVID-19 convalescent plasma; IgG, immunoglobulin G; S/Co, signal to cutoff ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

IgG levels decreased over time in a majority of repeat donors 71.6% (83/116) but increased in 15.5% (18/116) of donors. IgG levels remained unchanged in 4.3% of donors (5/116). In 8.6% of CCP donors (10/116), IgG levels fell below or remained consistently below the cutoff threshold (S/Co <1) (Figure 4C and Supplementary Figure 2A). Importantly, of the 10 donors with undetectable IgG levels at their final visit, 4 had undetectable IgG levels at initial presentation and the remaining 6 had very low initial IgG S/Co values (S/Co <3). For donors whose IgG levels decreased over time, an average decrease of 35.1% (± 20.9%) in the S/Co value was observed between the first and final visit. For donors whose IgG levels increased over time, the mean increase in IgG S/Co was 56.2% (± 53.3%).

In our analysis of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody titers over time, for 23.3% (27/116) of repeat CCP donors the FRNA50 titers decreased, and increased in only 7.8% (9/116) of donors. In 31.9% (37/116) of donors, neutralizing antibody titers remained unchanged over time or leveled off to a detectable titer for 2 or more consecutive final time points. Importantly, 37.1% (43/116) of donors, had no detectable neutralizing activity over time (n = 14) or had titers fall to undetectable levels (n = 29) (Figure 4D). We observed a striking relationship between neutralizing titer levels at first assessment and titer outcome over time. In general, donors with lower initial FRNA50 titers (<1:80) were more likely to lose neutralizing activity over time, while donors with higher starting titers were more likely to have their titer levels remain constant or level off over time (Supplementary Figure 2B). This can be seen when repeat CCP donors are stratified based on low (< 1:80) or high (> 1:80) starting titer levels at the initial study visit. For CCP donors with low initial neutralizing titer, 58.2% of donors (32/55) lost neutralizing activity or had titers that remained undetectable over time, compared to 18.0% (11/61) of high-titer CCP donors. Conversely, 34.4% (21/61) of high neutralizing titer donors compared to 29.1% (16/55) of low-titer donors had titers that remained unchanged or leveled off over time (Figure 4E). Additionally, in the high neutralizing titer group, the majority of donors saw their titer levels decrease over time44.3% (27/61). It remains to be seen whether titers would continue to fall for these donors or would level off over additional time points. Of note, no SARS-CoV-2 reinfection was observed in the study cohort.

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 has infected millions of individuals globally and, as of June 2021, has led to the death of >3 million individuals worldwide [15]. One of the reasons for the explosive increase in cases is the limited preexisting immunity to the virus. As the vaccination effort around the world began with multiple vaccine types and candidates, evolving variants add complexity to the plan to outrun the virus by vaccination. Cases of reinfections began to be reported in late 2020 [16–18]. Most of the reported reinfections were far less severe than the first infection in those early reports, boosting the optimistic hypothesis that immune memory of the millions of COVID-19 survivors would be able to contribute to the herd immunity to tame the pandemic. However, Zucman et al described a somber case that is an exception to those mild reinfections described to date, reporting a more severe reinfection caused by the South African variant 20H/501Y.V2 (B.1.351) [19].

As shown from studies of common human coronaviruses, neutralizing antibodies are induced and can last for years, providing protection from reinfection or, in some cases, from aggressive disease [20]. Fewer definitive data are available for SARS-CoV-2, and the emergence of multiple viral variants and the potential for more severe reinfection underscores the need to better understand the body’s natural immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Undoubtedly, a better understanding of antibody kinetics and protective immunity will be critical in terms of protection against reinfection, for public health policy, and vaccine development for COVID-19. To begin to address these questions, we conducted a prospective, longitudinal analysis of 228 CCP donors with multiple time points over an 11-month period. Studying recovered individuals provides an important opportunity to investigate both antiviral antibody quantification and population immunity conferred after exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, having repeat serological assessments allowed for the investigation of how circulating antibody levels change over time following natural infection.

At initial assessment, total and IgG SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were detected in 96.9% and 91.2% of donors, respectively. Total SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels were strongly correlated with IgG antibody levels, and neutralizing activity was observed in 73.2% of donors.

Our study suggests that most CCP plasma donors, regardless of COVID-19 disease severity, have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and more than 70% possess neutralizing antibodies. Notably, and in accordance with already published studies, we have observed a considerable range in antibody titers in recovered COVID-19 donors [21, 22].

When correlating IgG antibody levels and neutralizing titers with the clinical picture, our results are consistent with previously published data, observing positive correlation with disease severity [23–29], age [27–29], and BMI [30]. While some reports observed a correlation between antibody levels and male sex [28, 29, 31], we did not observe a statistically significant association in our study. This may be due to the predominantly mild symptomatic nature of our cohort, as men are also more likely to develop severe COVID-19 [32], presenting a potential confounding factor.

Longitudinal analyses of 116 CCP donors revealed that 91.4% of donors had detectable IgG levels up to 11 months after recovery. Although the majority of repeat donors demonstrated a decrease in IgG levels over follow-up, IgG levels decreased by only 35.1% on average, and seroreversion to negative was uncommon. Indeed, of the 8.6% of donors with undetectable IgG levels at their final study visit, just under half of these had no detectible IgG at the initial collection, while the rest represented cases of seroreversion (overall seroreversion rate of 5.2%). It is unlikely that the decline in IgG level was related to the number or frequency of plasma donations in this cohort because, in general, IgG levels do not appreciably decrease over the course of a few months of infrequent plasma donation [33].

However, IgG levels increased in 15.5% (18/116) of plasma donors returned for repeat study visits, and a constant high antibody titer was present up to 293 days from the first donation. IgG levels showed an increase at the last donation that ranged from 10 to 15 (median values) S/Co value. It could be that in these donors the seroconversion took a longer time to mount, in particular considering they were all mild cases.

With respect to neutralizing antibodies, SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody levels tended to remain detectable, irrespective of the disease severity. We found that 63% of donors had detectable neutralizing titers up to 11 months postrecovery, with 25% of donors seroreverting, and 12% of donors failing to make detectible neutralizing antibody titers over the course of the study. Although we have observed a decrease in plasma neutralizing activity over time, neutralizing antibody titers remained measurable in a majority of donors.

Importantly, we observed that if donors were stratified based on their titer level at initial assessment, 82% of donors with high starting titer (>1:80) maintained detectible titers over time, while this dropped to 41.8% for those with low starting titer (<1:80). Therefore, our data suggest that neutralizing activity in the early convalescent period may be predictive of long-term neutralizing activity retention. The levels of neutralizing antibody activity required to prevent SARS-CoV-2 reinfection are currently unknown. In our cohort, no SARS-CoV-2 reinfection was identified.

Our results support sustained immunological memory for most of the first year following SARS-CoV-2 infection, even for mild COVID-19 cases, consistent with other reports [34–36]. Furthermore, our data suggest that circulating IgG and neutralizing antibodies persist in most healthy people over the first year following symptom resolution, and longer-term follow-up studies by others have observed similar results out to 8 months [37–41]. However, other reports have observed a decline in immunological response over the first months following symptom resolution, particularly in mild and asymptomatic cases [42–44]. Such discordances could have major implications for modelling of disease transmission, herd immunity, and vaccine strategies. Following SARS-CoV-2 infection, B and T cells maintain immunological memory, which enables quicker and stronger response on the subsequent encounter with the same or a related pathogen and might contribute to herd immunity. Some authors suggest that antibodies confer protective immunity against future SARS-CoV-2 infection [45,46]; however, the strength and durability of this protection is unknown. In our CCP donor cohort we observed sustained immune memory, with IgG and neutralizing antibodies detected up to 11 months after recovery, supporting the notion that naturally infected patients may have the ability to combat reinfection. The role of nonneutralizing SARS-CoV-2 antibodies is unclear; however, they may confer in vivo protection and do not appear to be associated with antibody-dependent enhancement. More evidence is emerging about the role of cellular responses in protective immunity against COVID-19. Recent studies showed highly functional T-cell–mediated response even in individuals who did not mount an antibody response after SARS-CoV-2 infection [47]. Efforts are underway to identify the correlates of immunological protection through studying animal models, variable disease outcomes, and preexisting immunity to other coronaviruses [48].

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank National Institutes of Health (NIH) blood donors for their participation in the study.

Author contributions. K. W. conceived, designed, and supervised clinical protocols. V. D. G. conceived, designed, and supervised the research study. A. N. H. performed statistical analysis and generated all figures. L. C., S. P., and T. S. recruited participants, executed clinical protocols, and collected clinical data. J. T. provided oversight to clinical sample processing and testing. R. G., J. L., and E. N. P. performed the neutralization assays. M. R. H. provided oversight to neutralization work experiments and critically reviewed the manuscript. V. D. G., K. W., A. N. H., and L. C. wrote and critically reviewed the manuscript with input from all coauthors. H. J. A. and C. C. C. critically reviewed the manuscript.

Disclaimer. The views expressed are the authors’ own and do not represent the NIH, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the US Federal Government.

Financial support . This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH Clinical Center (grant number Z99 CL999999); and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, (NIAID/NIH) (grant number HHSN272201800013C). R. G., J. L., and M. R. H. performed this work as employees of Laulima Government Solutions, LLC and E. P. performed this work as an employee of Tunnell Government Services.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Jiang XL, Wang GL, Zhao XN, et al. Lasting antibody and T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients three months after infection. Nat Commun. 2021; 12:897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Byazrova M, Yusubalieva G, Spiridonova A, Efimov G, Mazurov D, Baranov K, et al. Pattern of circulating SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody-secreting and memory B-cell generation in patients with acute COVID-19. Clin Transl Immunol 2021; 10:e1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, et al. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA 2020; 323:1582–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cantore I, Valente P. Convalescent plasma from COVID 19 patients enhances intensive care unit survival rate. A preliminary report. Transfus Apher Sci 2020; 59:102848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li L, Zhang W, Hu Y, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on time to clinical improvement in patients with severe and life-threatening COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324:460–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muecksch F, Wise H, Batchelor B, et al. Longitudinal serological analysis and neutralizing antibody levels in coronavirus disease 2019 convalescent patients. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:389–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 2020; 181:281–92.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu W, Liu L, Kou G, et al. Evaluation of nucleocapsid and spike protein-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for detecting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58:e00461-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ortho Clinical Diagnostics. Instructions for use CoV2T. https://www.fda.gov/media/136967/download. Accessed 17 March 2021.

- 10. Bennett RS, Postnikova EN, Liang J, et al. Scalable, micro-neutralization assay for qualitative assessment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID 19) virus-neutralizing antibodies in human clinical samples. Viruses 2021; 13:893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dean RB, Dixon WJ. Simplified statistics for small numbers of observations. Anal Chem 1951; 23:636–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rorabacher DB. Statistical treatment for rejection of deviant values: critical values of Dixon’s “Q” parameter and related subrange ratios at the 95% confidence level. Anal Chem 2002; 63:139–146.12. [Google Scholar]

- 13. United States Census Bureau. www.census.gov. Accessed 25 May 2021.

- 14. Garratty G, Glynn SA, McEntire R, Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. ABO and Rh(D) phenotype frequencies of different racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Transfusion 2004; 44:703–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. John Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. Accessed 16 June 2021.

- 16. Selvaraj V, Herman K, Dapaah-Afriyie K. Severe, symptomatic reinfection in a patient with COVID-19. R I Med J (2013) 2020; 103:24–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. To KK, Hung IF, Chan KH, et al. Serum antibody profile of a patient with coronavirus disease 19 reinfection. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:e659–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. To KK, Hung IF, Ip JD, et al. COVID-19 re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-coronavirus-2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing [published online ahead of print 18 May 2021]. Clin Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zucman N, Uhel F, Descamps D, Roux D, Ricard JD. Severe reinfection with South African SARS-CoV-2 variant 501Y.V2: a case report [published online ahead of print 10 February 2021]. Clin Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2021; 397:220–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang AT, Garcia-Carreras B, Hitchings MDT, Yang B, Katzelnick LC, Rattigan SM, et al. A systematic review of antibody mediated immunity to coronaviruses: kinetics, correlates of protection, and association with severity. Nat Commun 2020; 11:4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benner SE, Patel EU, Laeyendecker O, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody avidity responses in COVID-19 patients and convalescent plasma donors. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:1974–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu F, Liu M, Wang A, et al. Evaluating the association of clinical characteristics with neutralizing antibody levels in patients who have recovered from mild COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:1356–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Long QX, Tang XJ, Shi QL, et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med 2020; 26:1200–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ko JH, Joo EJ, Park SJ, et al. Neutralizing antibody production in asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients, in comparison with pneumonic COVID-19 patients. J Clin Med 2020; 9:2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lei Q, Li Y, Hou HY, et al. Antibody dynamics to SARS-CoV-2 in asymptomatic COVID-19 infections. Allergy 2021; 76:551–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen Y, Zuiani A, Fischinger S, et al. Quick COVID-19 healers sustain anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody production. Cell 2020; 183:1496–507.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robbiani DF, Gaebler C, Muecksch F, et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature 2020; 584:437–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boonyaratanakornkit J, Morishima C, Selke S, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and temporal predictors of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 among COVID-19 convalescent plasma donor candidates. J Clin Invest 2021; 131:e144930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Racine-Brzostek SE, Yang HS, Jack GA, et al. Postconvalescent SARS-CoV-2 IgG and neutralizing antibodies are elevated in individuals with poor metabolic health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 106:e2025–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bwire GM. Coronavirus: why men are more vulnerable to Covid-19 than women? [published online ahead of print 4 June 2020]. SN Compr Clin Med doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00341-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020; 369:m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burgin M, Hopkins G, Moore B, Nasser J, Richardson A, Minchinton R. Serum IgG and IgM levels in new and regular long-term plasmapheresis donors. Med Lab Sci 1992; 49:265–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Terpos E, Mentis A, Dimopoulos MA. Loss of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in mild Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mateus J, Grifoni A, Tarke A, et al. Selective and cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 T cell epitopes in unexposed humans. Science 2020; 370:89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wajnberg A, Amanat F, Firpo A, et al. Robust neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection persist for months. Science 2020; 370:1227–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang XL, Wang GL, Zhao XN, et al. Lasting antibody and T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients three months after infection. Nat Commun 2021; 12:897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 2021; 371:eabf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lau EHY, Tsang OTY, Hui DSC, et al. Neutralizing antibody titres in SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Commun 2021; 12:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marot S, Malet I, Leducq V, et al. Rapid decline of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 among infected healthcare workers. Nat Commun 2021; 12:844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ibarrondo FJ, Fulcher JA, Goodman-Meza D, et al. Rapid decay of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in persons with mild Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1085–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu F, Liu M, Wang A, et al. Evaluating the association of clinical characteristics with neutralizing antibody levels in patients who have recovered from mild COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:1356–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Long QX, Tang XJ, Shi QL, et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med 2020; 26:1200–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell 2020; 181:1489–501.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Harvey RA, Rassen JA, Kabelac CA, et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 seropositive antibody test with risk of future infection. JAMA Intern Med 2021; 181:672–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Priyanka Choudhary OP, Singh I. Protective immunity against COVID-19: unravelling the evidences for humoral vs. cellular components. Travel Med Infect Dis 2021; 39:101911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nelde A, Bilich T, Heitmann JS, et al. SARS-CoV-2-derived peptides define heterologous and COVID-19-induced T cell recognition. Nat Immunol 2021; 22:74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kang CK, Kim M, Lee S, et al. Longitudinal analysis of human memory T-cell response according to the severity of illness up to 8 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection 2021; 224:39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.