Abstract

Glomerella leaf spot (GLS), a fungal disease caused by Colletotrichum fructicola, severely affects apple quality and yield, yet few resistance genes have been identified in apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). Here we found a transcription factor MdWRKY17 significantly induced by C. fructicola infection in the susceptible apple cultivar “Gala.” MdWRKY17 overexpressing transgenic “Gala” plants exhibited increased susceptibility to C. fructicola, whereas MdWRKY17 RNA-interference plants showed opposite phenotypes, indicating MdWRKY17 acts as a plant susceptibility factor during C. fructicola infection. Furthermore, MdWRKY17 directly bound to the promoter of the salicylic acid (SA) degradation gene Downy Mildew Resistant 6 (MdDMR6) and promoted its expression, resulting in reduced resistance to C. fructicola. Additionally, Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) 3 (MdMPK3) directly interacted with and phosphorylated MdWRKY17. Importantly, predicted phosphorylation residues in MdWRKY17 by MAPK kinase 4 (MdMEK4)-MdMPK3 were critical for the activity of MdWRKY17 to regulate MdDMR6 expression. In the six susceptible germplasms, MdWRKY17 levels were significantly higher than the six tolerant germplasms after infection, which corresponded with lower SA content, confirming the critical role of MdWRKY17-mediated SA degradation in GLS tolerance. Our study reveals a rapid regulatory mechanism of MdWRKY17, which is essential for SA degradation and GLS susceptibility, paving the way to generate GLS resistant apple.

MdWRKY17 directly activates the expression of Downy Mildew Resistant 6 (MdDMR6), resulting in salicylic acid (SA) degradation and Glomerella leaf spot susceptibility in apple.

Introduction

Apple (Malus domestica) is a popular fruit around the world. Perennial apple trees are exposed to a wide variety of pathogens. Colletotrichum fructicola, a hemibiotrophic fungus that was first reported in Brazil in 1988, causes Glomerella leaf spot (GLS) in apple (Leite et al., 1988). Since 2011, multiple GLS outbreaks have occurred in China, making it one of the most devastating fungal diseases of apple (Wang et al., 2012). GLS causes severe defoliation during the growing season. This disease also infects fruit, causing fruit spots and drop, which severely reduce apple quality and yield (Wang et al., 2015). In addition, GLS weakens tree vigor, thereby affecting fruit production the following year.

GLS has affected almost all apple-producing areas in China. The only approach currently used to control GLS is spray application of the fungicide dithiocarbamate. However, dithiocarbamate cannot protect susceptible apple cultivars such as the popular cultivar “Gala” from C. fructicola contamination, resulting in great losses in apple production. Dithiocarbamate not only reduces food safety and pollutes the environment, but also increases production costs (Wang et al., 2015). Therefore, there is much interest in breeding C. fructicola-resistant apple cultivars. The most effective, organic strategy for disease control is molecular breeding, which depends on clarifying the molecular mechanism underlying disease resistance.

In the plant defense response against invading pathogens, when pathogen-/microbe-associated molecular patterns or pathogen-derived effector proteins are recognized by plants, signaling inside the cell can be activated to elicit pathogen responses (Ramirez-Prado et al., 2018). The activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades is a key event during defense signaling (Su et al., 2017). MAPKs target and phosphorylate various transcription factors that regulate the transcription of downstream genes involved in a range of physiological processes, ultimately orchestrating pathogen tolerance (Meng and Zhang, 2013).

To date, MPK3 has been shown to function in plant immunity with a positive role or negative role in disease signaling (Meng and Zhang, 2013; Frei Dit Frey et al., 2014). The MAPK kinase 4/5(MKK4/5)-MPK3 cascade functions in both fungal and bacterial signaling, regulating ethylene biosynthesis and camalexin production during Botrytis cinerea (Han et al., 2010; Mao et al., 2011) and regulating stomatal closure during Pseudomonas syringae signaling (Su et al., 2017). MAPK cascades propagate biotic signals by phosphorylating various transcription factors, including WRKY, ERF, and MYB (Xu et al., 2016). WRKYs are important targets of MAPK cascades. For instance, MPK3/MPK6-WRKY33 and MAPK-WRKY7/8/9/11 function in B. cinerea and Phytophthora infestans signaling, respectively (Li et al., 2012; Adachi et al., 2015).

WRKY transcription factors play key roles in plant resistance to various pathogens. WRKYs contain a highly conserved WRKYGQK heptapeptide at their N-terminus which specifically binds to W-boxes with the sequence (T)(T)TGAC(C/T) in the promoters of their downstream genes (Rushton et al., 2010). WRKY transcription factors regulate resistance to downy mildew in grapevine (Vitis vinifera), witches’ broom disease in jujube (Ziziphus jujuba), canker disease in grapefruit (Citrus paradisi), and GLS in apple (Merz et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2015; Xue et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019a).

WRKYs control various physiological processes including salicylic acid (SA; also known as 2-hydroxybenzoic acid) biosynthesis and phytoalexin secretion by directly regulating the transcription of ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE1 (ICS1), Phytoalexin Deficient 3 (PAD3), and the Pleiotropic Drug Resistance transporter genes PEN3, and PDR12 in response to Xanthomonas oryzae and B. cinerea infection, respectively (van Verk et al., 2011; Birkenbihl et al., 2012; He et al.,2019). WRKY33 downregulates SA levels and SA signaling pathways in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Birkenbihl et al., 2012). By contrast, in apple, MdWRKY15 enhances SA accumulation by activating the SA synthetase gene MdICS1, thereby conferring resistance to Botryosphaeria dothidea (Zhao et al., 2019).

SA induces the massive production of antimicrobial pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins that function in plant defense (Zheng et al., 2015), making it an important hormone in pathogen defense responses. SA hydroxylation is the main pathway mediating SA degradation, in which SA is hydroxylated by an enzyme encoded by Downy Mildew Resistant 6 (DMR6; Zhang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2017).

SA levels in plants are primarily determined by the balance of SA biosynthesis (mainly controlled by ICS1) and SA degradation (regulated by the catabolic genes DMR6 and SAG108; Seyfferth and Tsuda, 2014). To date, only the transcriptional regulation of SA biosynthesis has been intensively studied. The calmodulin-binding proteins 60 g and WRKY28 directly activate the transcription of ICS1, whereas NAC019/NAC055/NAC072 directly inhibit the expression of this gene (Zhang et al., 2010; van Verk et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2012). The transcriptional regulation of SA catabolism remains unclear.

Since the 2011 outbreak of GLS in China, several studies have been carried out to explore the molecular mechanism underlying GLS resistance. The C. fructicola strains causing this outbreak were isolated in 2018 (Liang et al., 2018) and the C. fructicola resistance loci in apple were mapped to a 9.8-cM region (Liu et al., 2016). However, the candidate resistance genes have not been isolated. The exogenous application of SA induces strong disease resistance against GLS in highly susceptible apple cultivars by enhancing the activities of defense-related enzymes and upregulating the expression of PR genes (Zhang et al., 2016). In addition, the GLS-responsive gene miRln20 negatively regulates GLS resistance by suppressing the expression of the resistance gene TN1-GLS (Zhang et al., 2019b). Similarly, MdWRKY100 conferred enhanced tolerance to C. fructicola in transgenic apple by upregulating the expression of several PR genes (Zhang et al., 2019a). However, the signaling pathways in apple that transduce extracellular stimuli into the cell during the response to C. fructicola, including the transcription factors that orchestrate downstream physiological processes that promote GLS tolerance, is unknown.

In this study, we identified a transcription factor MdWRKY17 from GLS susceptible cultivar “Gala,” which is a susceptibility factor directly upregulating MdDMR6 gene to degrade SA. Additionally, the phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 at the proved residues by GLS-activated MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade is critical for its activity to regulate MdDMR6 expression. The differential MdWRKY17 levels between six tolerant and six susceptible germplasms, corresponding with SA content, confirming the critical role of MdWRKY17 mediated SA degradation in GLS tolerance. Our identification of a pathway in the defense response to GLS provides insight into the molecular mechanism underlying immunity and could facilitate the molecular breeding of apple varieties with improved resistance to C. fructicola.

Results

C. fructicola induced transcriptional activator MdWRKY17 operates negatively in apple C. fructicola tolerance

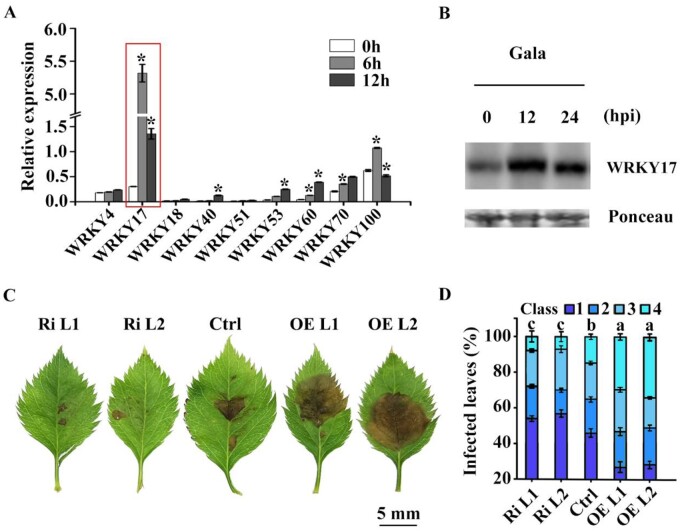

To identify the WRKY candidate involved in apple C. fructicola resistance, we compared the expression profiles of nine selected MdWRKY candidates, in susceptible apple variety “Gala” using reverse transcription-quantative real time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis. Upon C. fructicola inoculation, MdWRKY17 expression was induced to almost 18 times before infection, also significantly higher than all the other candidate genes within 6 h (Figure 1A). MdWRKY17 is a transcriptional activator localized in nucleus (Supplemental Figure S1). It belongs to the subgroup I and has the highest amino acid identity (49.36%) with AtWRKY33 (Supplemental Figures S2 and S3). Immunoblot analysis indicated that C. fructicola treatment substantially increased MdWRKY17 protein levels in susceptible “Gala” (Figure1B). These findings indicate that MdWRKY17 is a transcriptional activator involved in the response of apple to C. fructicola.

Figure 1.

MdWRKY17 negatively regulates GLS tolerance in apple. (A) Relative expression levels of the disease-involved MdWRKYs detected by RT-qPCR in susceptible variety “Gala” at 0, 6, and 12 h after C. fructicola infection. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (Student’s t test): *P < 0.05. (B) MdWRKY17 levels increased in susceptible “Gala” after C. fructicola infection. MdWRKY17 level was detected by immunoblot analysis using MdWRKY17 antibody, and Ponceau stained bands indicated protein loading. (C) The phenotypes of leaves from transgenic plants overexpressing MdWRKY17 or RNAi of MdWRKY17 and control plants 4 d after C. fructicola infection. MdWRKY17 silencing by RNAi increased GLS tolerance, while MdWRKY17 overexpression conferred increased GLS susceptibility. Bar, 5 mm. (D) Statistics of GLS susceptibility in leaves 4 d after inoculation with C. fructicola in MdWRKY17 overexpression or RNAi lines and control plants. The disease symptoms in the leaves were scored based on the lesion size (Class 0, no symptoms; Class 1, <2 mm; Class 2, from 2 to 6 mm; Class 3, from 6 to 10 mm; Class 4, from 10 to 14 mm; and Class 5, >14 mm). Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) of Class 4 using Fisher’s LSD.

Compared to control plants, transgenic plants overexpressing MdWRKY17 were hypersensitive to C. fructicola; the leaves with most severe symptoms were nearly 2 times of that in untransformed control plants. By contrast, in RNAi MdWRKY17 lines, leaves with severe symptoms were only half of the control (Figure1, C and D; Supplemental Figure S4). These results indicated that MdWRKY17 is an important negative regulator of C. fructicola resistance.

MdWRKY17 is phosphorylated by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade

We investigated the phosphorylation variation of MdWRKY17 after C. fructicola infection in both apple leaves and calli. Flag-MdWRKY17WT was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag agarose beads from apple calli transiently transformed by agrobacteria carrying Flag-MdWRKY17WT, which were collected at 0, 12, and 24 h after infection. Then MdWRKY17WT was quantified for its phosphorylation observation by immunoblot analysis using a p-Ser/Thr antibody. The phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 increased significantly, suggesting C. fructicola infection-induced this phosphorylation. Similar result was obtained in apple leaves (Figure 2A;Supplemental Figure S5).

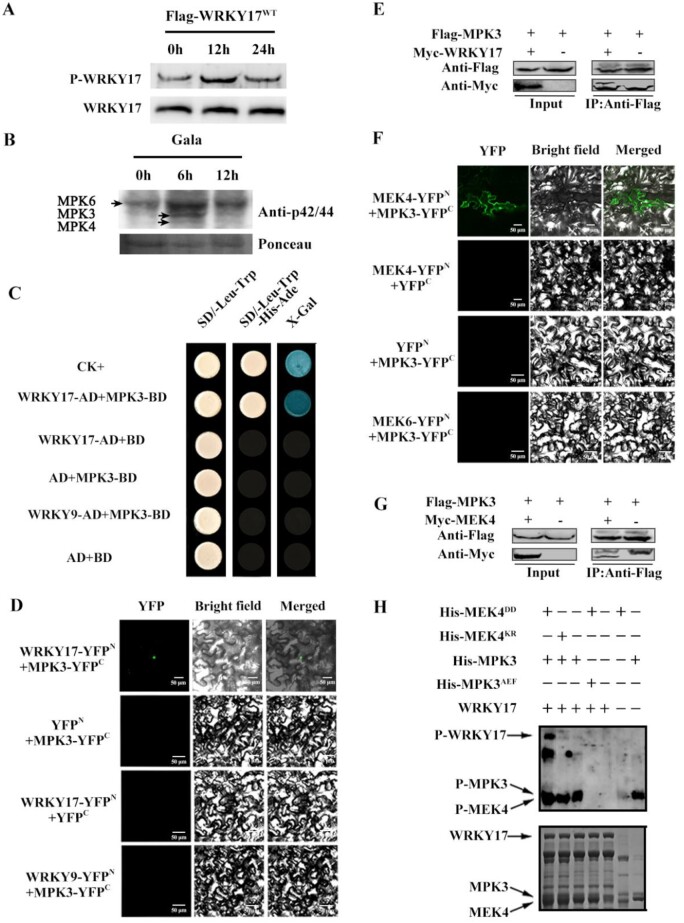

Figure 2.

Identification of the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade, which phosphorylates MdWRKY17. (A) The phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 is induced by C. fructicola infection. In apple calli transiently transformed with Flag-MdWRKY17WT, C. fructicola infection substantially increased MdWRKY17 phosphorylation. Flag-MdWRKY17WT was overexpressed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag agarose beads in transiently transformed apple calli after C. fructicola infection, which was quantified by immunoblot analysis using Anti-Flag antibody for the further phosphorylation detection by immunoblotting with p-Ser/Thr antibody. (B) MdMPK3 was activated dramatically 6 h after C. fructicola infection. MAPK activities at 0, 6, and 12 h after C. fructicola infection were analyzed by immunoblot with Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) antibody, and Ponceau stained bands indicate protein loading. (C) Confirmation of the interaction between MdWRKY17 and MdMPK3 by Y2H analysis. Yeast cells harboring pGADT7-MdWRKY17 and pGBKT7-MdMPK3 were grown on SD/-Leu/-Trp or SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade medium. The pGADT7-T and pGBKT7-p53 pair was used as a positive control (CK+), whereas the pGADT7-MdWRKY9 and pGBKT7-MdMPK3 pair, pGADT7 and pGBKT7-MdMPK3 pair, pGADT7-MdWRKY17 and pGBKT7 pair, and pGADT7 and pGBKT7 pair were used as negative controls. (D) Visualization of MdWRKY17–MdMPK3 interaction via BiFC. N. benthamiana leaves were agroinfiltrated with the N-terminal part of YFP fused with MdWRKY17 (nYFP-MdWRKY17) and the C-terminal part of YFP fused with MdMPK3 (cYFP-MdMPK3). The combination of nYFP-MdWRKY9 and cYFP-MdMPK3 was used as a negative control. YFP signals were detected by confocal microscopy (×40). Bar, 50 μm. (E) In vivo Co-IP assay between MdWRKY17 and MdMPK3. The total proteins were extracted from 35S::MdWRKY17‐Myc + 35S:: MdMPK3‐Flag or 35S::Myc + 35S:: MdMPK3‐Flag co‐ expressed N. benthamiana, and then immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag agarose beads. The anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis, respectively. (F) BiFC visualization of the MdMPK3–MdMEK4 interaction in N. benthamiana leaves. The combination of nYFP-MdMEK6 and cYFP-MdMPK3 was used as a negative control. Bar, 50 μm. (G) In vivo Co-IP assay between MdMEK4 and MdMPK3. The total proteins were extracted from 35S:: MdMEK4‐Myc + 35S:: MdMPK3‐Flag or 35S::Myc + 35S:: MdMPK3‐Flag co‐expressed N. benthamiana, and then immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag agarose beads. The anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis, respectively. (H) In vitro kinase assay of MdWRKY17 phosphorylation by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade. Recombinant MdWRKY17 was phosphorylated by MdMPK3 following activation by constitutively activated MdMEK4DD. A kinase-negative variant (MdMEK4KR) and a kinase-dead form of MdMPK3 (MdMPK3AEF) were used as the negative control.

To further isolate the kinase for MdWRKY17 phosphorylation, a yeast screening assay was performed. As a result, MdMPK3 was identified and found to be activated dramatically by C. fructicola infection (Figure 2B;Supplemental Figure S6). Furthermore, the interaction of MdWRKY17 and MdMPK3 is confirmed by a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay (Figure 2C). MdMPK3 interacted with MdWRKY17 in the nucleus, as determined by a bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay (Figure 2D). Furthermore, the in vivo interaction of MdWRKY17 and MdMPK3 was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) in infiltrated Nicotiana benthamiana by Agrobacterium with 35S:: MdWRKY17‐Myc + 35S::MdMPK3‐Flag, or 35S::Myc + 35S::MdMPK3‐Flag as negative control, respectively. The MdWRKY17‐Myc could be immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag agarose beads, but negative control Myc could not (Figure 2E), confirming the in vivo interaction between MdMPK3 and MdWRKY17. To identify the upstream kinases, we investigated the interactions of all five MdMEKs with MdMPK3 via a BiFC assay. MdMEK4 interacted with MdMPK3 on the plasma membrane and in the nucleus (Figure 2F;Supplemental Figure S7), which was confirmed by further in vivo Co-IP assay (Figure 2G).

We conducted an in vitro kinase assay to determine whether the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade could phosphorylate MdWRKY17. MdWRKY17 was strongly phosphorylated by MdMPK3 following activation by the constitutively active kinase MdMEK4DD, but not by a kinase-dead form of MdMPK3 (MdMPK3AEF) or a kinase-negative form of MdMEK4 (MdMEK4KR; Figure 2H). These results indicate that the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade phosphorylates MdWRKY17 in vitro.

MdWRKY17 directly up-regulates MdDMR6 gene to degrade SA

The level of SA and Jasmonic Acid (JA), two important plant defense hormones, were measured to identify the possible physiological process regulated by MdMEK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17. As shown in Figure 3A, compared to untransformed control plants, the level of SA was only 68% in transgenic lines overexpressing MdWRKY17 and 130% in transgenic RNAi MdWRKY17. However, there is no significant difference of JA between transgenic lines and control (Supplemental Figure S8).

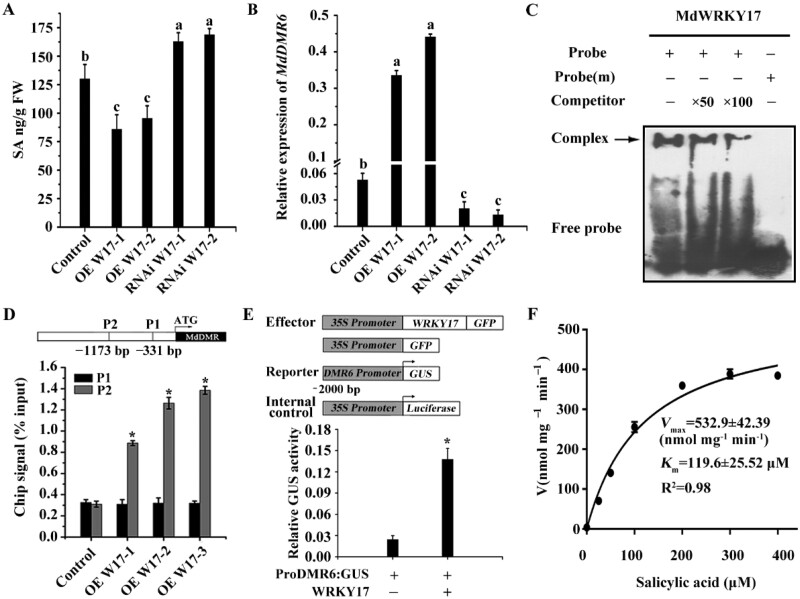

Figure 3.

MdWRKY17 directly up-regulates MdDMR6 gene to degrade SA. (A) SA levels are significantly lower in the leaves of transgenic apple plant overexpressing MdWRKY17 but higher in RNAi plants compared to those in control “Gala” plants. (B) MdDMR6 expression is significantly higher in MdWRKY17 overexpression lines and lower in RNAi lines than in control plants. Data in A and B are mean ± SD of three replicates. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) using Fisher’s LSD. (C) EMSA confirming the in vitro binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter. Arrow indicates the position of a protein-DNA complex after incubation of biotin-labeled DNA probe with MBP-MdWRKY17. Both the probe containing a W-box (TTGACC) and the probe (m) containing a mutated W-box (TTAAAA) were synthesized based on the sequence of the MdDMR6 promoter. And ×50 and ×100 means that the amount of unlabeled probe was 50 times or 100 times higher than the biotin-labeled probe. (D) Significantly more MdWRKY17 binds to the W-box of the MdDMR6 promoter in MdWRKY17 overexpression lines vs. the control, as indicated by ChIP-qPCR. The position of the W-box is indicated by a gray bar. The ChIP signal was quantified as the percentage of immunoprecipitated DNA in the total input DNA, as determined by qPCR. Data are means ± SD. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (Student’s t test): *P < 0.05. (E) Relative GUS activity normalized by luciferase (LUC) activity in apple calli transiently transformed by agrobacteria EHA105 respectively carrying pCAMBIA1301-MdDMR6pro and 35Spro: LUC, and co-transformed with pMDC83-MdWRKY17 or pMDC83. The LUC gene driven by the 35S promoter was used as an internal control for transformation efficiency. Relative GUS activity (GUS/LUC) indicates the ultimate quantification of the MdDMR6 promoter activity. Data are means ± SD. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (Student’s t test): *P < 0.05. (F) Enzyme kinetics of recombinant MdDMR6 protein (SA as the substrate). MdDMR6 was incubated with increasing concentrations of SA (0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 μM) for 30 min at 30°C. Km and Vmax were determined using the Michaelis–Menten equation. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments.

The expression levels of genes involved in SA biosynthesis (MdICS1-1 and MdICS1-2) and SA signaling (MdEDS1-1, MdEDS1-2, MdPAD4-1, and MdPAD4-2) were not significantly altered in the transgenic plants (Supplemental Figure S9). However, the expression level of the SA degradation gene MdDMR6 was 7 times higher in the overexpression lines and 50% lower in the RNAi lines than in the untransformed control (Figure 3B), suggesting MdWRKY17 regulates SA degradation rather than biosynthesis or signaling.

An in vitro electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showed that MdWRKY17 can bind to the P2 fragment of the MdDMR6 promoter containing the W-box. Competition from unlabeled probe decreased this binding, and a mutation in the W-box abolished this binding, confirming that MdWRKY17 binds specifically to the MdDMR6 promoter (Figure 3C). In an in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR assay, in all three overexpression lines, MdWRKY17 specifically bound to the P2 fragment of the MdDMR6 promoter at a rate nearly four-fold that of control plants, confirming this specific binding in vivo (Figure 3D).

In addition, MdWRKY17 overexpression in transiently transformed apple calli increased the activity of GUS driven by the MdDMR6 promoter to a level nearly 4 times that of the control (without MdWRKY17 overexpression; Figure 3E), indicating that MdWRKY17 activates MdDMR6 expression in vivo. Together, these results indicate that MdWRKY17 specifically binds to the MdDMR6 promoter and activates its expression.

The phylogenic tree analysis showed that MdDMR6 is a homolog of AtDMR6 (Supplemental Figure S10), encoding SA hydroxylase, which converts SA to 2,5-DHBA (Zhang et al., 2017). An enzymatic assay showed that GST-MdDMR6 catalyzes the conversion of SA to 2,5-DHBA in vitro. The catalytic rate increased as the SA concentration increased from 0 to 300 µM but remained nearly unchanged as the SA concentration increased from 300 to 400 µM. The calculated Km and Vmax of this enzyme were 119.6 ± 25.52 µM and 532.9 ± 42.39 nmol mg−1 min−1, respectively (Figure 3F).

The MdMEK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 pathway reduces SA levels and increases GLS susceptibility

Exogenous treatment with SA by spraying partially reversed the GLS hypersensitivity of transgenic apple plants overexpressing MdWRKY17 (Figure 4, A and B), suggesting that GLS hypersensitivity induced by MdWRKY17 overexpression might be mediated by SA decrease.

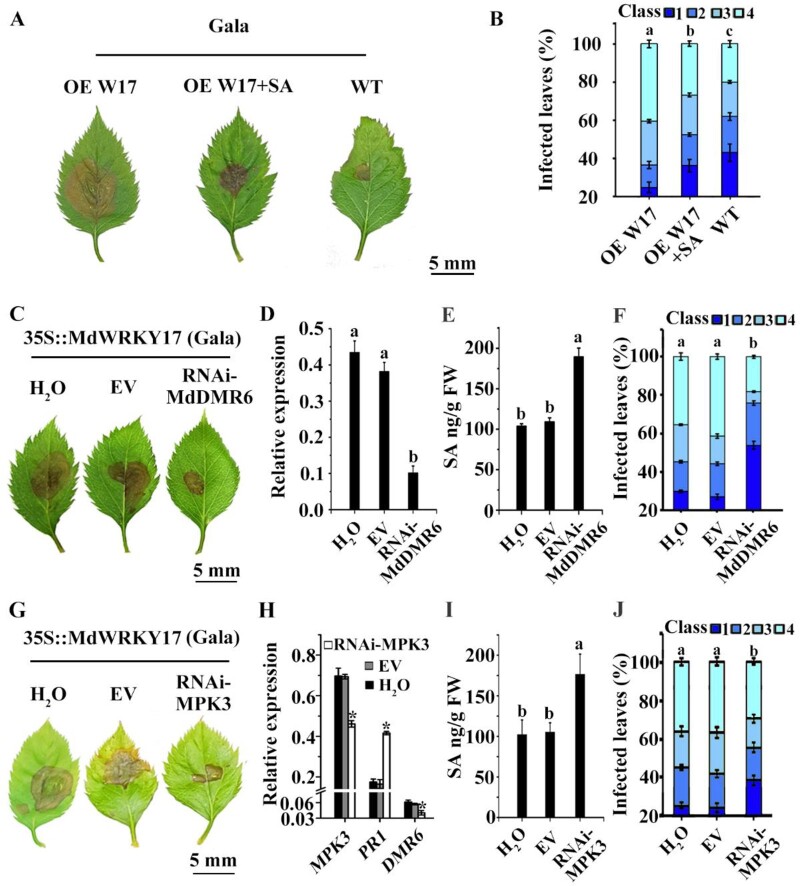

Figure 4.

The MdMEK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 plays a critical role in SA degradation-mediated GLS susceptibility in the transgenic plant overexpressing MdWRKY17. (A–B) Exogenous application of SA partially rescues the GLS susceptibility of transgenic apple plants overexpressing MdWRKY17. The phenotype of leaves from transgenic apple plants overexpressing MdWRKY17 was observed (A). And the percentage of variant leaf susceptibility was recorded (B). Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) of Class 4 using Fisher’s LSD. (C) RNA-interfered MdDMR6 partially rescues GLS susceptibility of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines. Fully developed leaves of sub-cultured MdWRKY17 overexpression lines were injected at their centers with Agrobacterium harboring pZH01-MdDMR6, with water and empty pZH01 vector used as controls. Three days after injection, the C. fructicola spore suspension was applied to the injection site for GLS infection. RNA-interfered MdDMR6 clearly conferred GLS tolerance to the MdWRKY17 overexpression line. (D) MdDMR6 transcript levels in the leaves of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines after RNAi of MdDMR6, as detected by RT-qPCR prior to C. fructicola inoculation. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) using Fisher’s LSD. (E) SA levels are significantly increased in the leaves of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines after RNA interference of MdDMR6 compared to the control. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) using Fisher’s LSD. (F) GLS tolerance of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines with RNA interference of MdDMR6 is enhanced at 4 d after C. fructicola inoculation compared to the control. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) of Class 4 using Fisher’s LSD. (G) RNA-interfered MdMPK3 rescued GLS susceptibility of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines. GLS tolerance observed in the leaves of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines after RNAi of MdMPK3 and C. fructicola incubation. (H) MdMPK3, MdDMR6, and MdPR1 (SA marker gene) transcript levels in the leaves of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines after RNAi of MdMPK3. RT-qPCR showed that RNA-interfered MdMPK3 reduced MdMPK3 and MdDMR6 expression in MdWRKY17 overexpression lines and increased MdPR1 expression significantly compared to the MdWRKY17 overexpression lines as controls. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (Student’s t test): *P < 0.05. (I) SA levels are significantly higher in the leaves of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines after RNAi of MdMPK3 compared to the control. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) using Fisher’s LSD. (J) GLS tolerance of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines with RNAi of MdMPK3 is enhanced at 4 d after C. fructicola inoculation compared to the control. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) of Class 4 using Fisher’s LSD.

To check if the MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 pathway plays an important role in SA-mediated GLS tolerance, we silenced MdDMR6 by RNA interference in the leaves of transgenic apple overexpressing MdWRKY17 (Figure 4C). The expression of MdDMR6 decreased by nearly 75% in leaves compared with two controls (Figure 4D), which led to 73% higher SA levels and reduced the most severe symptoms to nearly half in transgenic leaves (Figure 4, E and F), suggesting that MdDMR6-resulted SA-decrease is the major reason of the GLS susceptibility of MdWRKY17 overexpression lines.

To confirm that the MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 pathway plays an important role in GLS tolerance, we silenced MdMPK3 by RNA interference in the leaves of transgenic apple overexpressing MdWRKY17 (Figure 4G). This resulted in the decreased expression of MdDMR6, increased SA levels, and improved GLS tolerance in transgenic leaves, compared to the control (Figure 4, H–J). These results suggest that the MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 cascade plays a critical role in GLS tolerance.

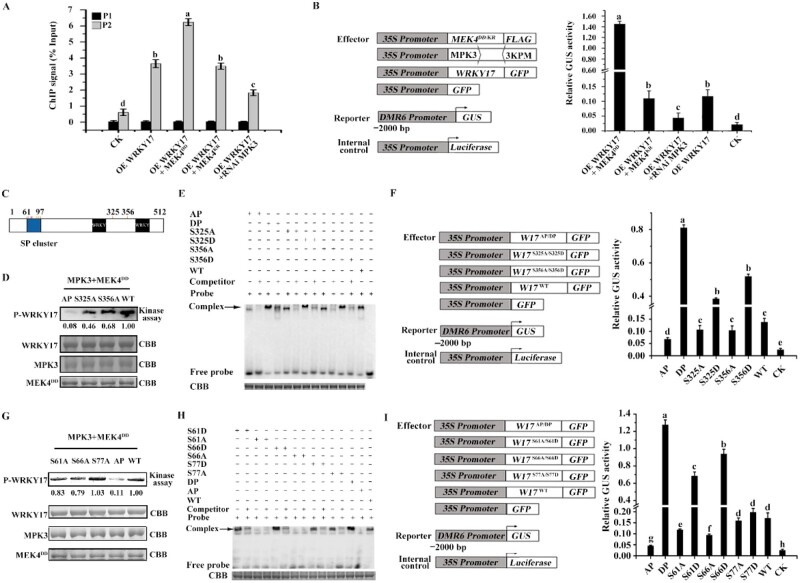

Phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade is involved in regulating MdDMR6 expression

To explore how the phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade affects its ability to regulate MdDMR6, we examined the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter and MdDMR6 expression in transiently transformed apple calli by ChIP-qPCR. The overexpression of MdWRKY17 significantly increased the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter. This binding was enhanced when the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade was constitutively activated but was nearly unchanged when the cascade remained inactive. This binding was further reduced when MdMPK3 was silenced by RNA interference (Figure 5A). These results demonstrate that the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter is enhanced by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 at S61, S66, S325, and S356 by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade increases the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter for its transcription. (A) Binding of MdWRKY17 phosphorylated by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade to the MdDMR6 promoter, as indicated by ChIP-qPCR. The position of the W-box is indicated as in Figure 3C. The ChIP signal was quantified as the percentage of immunoprecipitated DNA in the total input DNA, as determined by qPCR. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) using Fisher’s LSD. (B) Relative GUS activity normalized by LUC activity in apple calli transiently transformed by Agrobacterium EHA105 respectively carrying pMDC83-MdWRKY17, pCAMBIA1301-MdDMR6pro, and 35Spro: LUC, and co-transformed with pCAMBIA1300-MdMEK4DD/KR, pZH01-MdMPK3, or pCAMBIA1300. MdDMR6 expression directly regulated by MdWRKY17 was enhanced by the activated MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) using Fisher’s LSD. (C) Putative phosphorylated Ser/Thr residues of MdWRKY17 by MdMAPK cascades are indicated in orange and blue, respectively. Clustered Pro-directed Ser residues (SP cluster) was indicated with dark blue. The numbers indicate the positions of amino acids in MdWRKY17. (D) Confirmation of the phosphorylation sites of MdWRKY17 by MdMPK3 via an in vitro kinase assay. MdMPK3 constitutively activated by MdMEK4DD, a constitutively active kinase form of MdMEK4, was used to phosphorylate recombinant MdWRKY17 and its three mutants at S-61/S-66/T-73/S-77/S-85/S-97 in the SP cluster, S325 and S356 with Ala (A), respectively named as MdWRKY17AP, MdWRKY17S325A, and MdWRKY17S356A. The loading of MdWRKY17, MdMPK3, and MdMEK4DD was quantified by CBB staining. The phosphorylation of wild-type and mutated MdWRKY17 were detected by immunoblot analysis using p-Ser/Thr antibody. MdWRKY17 phosphorylation was significantly reduced when S-61/S-66/T-73/S-77/S-85/S-97 in the SP cluster, 325-S, or 356-S was mutated. (E). The phosphorylation of S-61/S-66/T-73/S-77/S-85/S-97 in the SP cluster, S325 or S356 in MdWRKY17 enhances its binding to the MdDMR6 promoter. Recombinant MdWRKY17 and its three mutants at S-61/S-66/T-73/S-77/S-85/S-97 in the SP cluster, S325 and S356 with Asp (D), respectively named as MdWRKY17DP, MdWRKY17S325D, and MdWRKY17S356D. In the EMSA, the binding of MdWRKY17 to the W-box of the MdDMR6 promoter was enhanced by the phospho-mimicking mutations of MdWRKY17 protein (MBP-MdWRKY17DP/S325D/S356D) in the constitutively phosphorylated form and was reduced by MBP-MdWRKY17AP/S325A/S356A in the nonphosphorylated form compared to MBP-MdWRKY17WT. (F) The phosphorylation of S-61/S-66/T-73/S-77/S-85/S-97 in the SP cluster, S325 or S356 in MdWRKY17 activates MdDMR6 expression in transiently transformed calli. Relative GUS activity was normalized with LUC activity in apple calli transiently transformed with Agrobacterium EHA105 carrying pCAMBIA1301-MdDMR6 pro and 35Spro: LUC, respectively, and co-transformed with pMDC83-MdWRKY17AP/DP/S325A/S325D/S356A/S356D/WT. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) using Fisher’s LSD. (G) Confirmation of the phosphorylation sites in SP cluster of MdWRKY17 by MdMPK3 via an in vitro kinase assay. MdMPK3 constitutively activated by MdMEK4DD was used to phosphorylate recombinant MdWRKY17 and its four mutants MdWRKY17S61A, MdWRKY17S66A, MdWRKY17S77A, and MdWRKY17AP, respectively. The loading of MdWRKY17, MdMPK3, and MdMEK4DD was quantified by CBB staining. The phosphorylation of wild-type and mutated MdWRKY17 were detected by immunoblot analysis using p-Ser/Thr antibody. MdWRKY17 phosphorylation was significantly reduced when 61-S or 66-S in the SP cluster was mutated. (H) The phosphorylation of S-61 or S-66 in MdWRKY17 enhances its binding to the MdDMR6 promoter. In the EMSA, the binding of MdWRKY17 to the W-box of the MdDMR6 promoter was enhanced by the phospho-mimicking mutations of MdWRKY17 protein (MBP-MdWRKY17S61D/S66D/DP) and was reduced by MBP-MdWRKY17S61A/S66A/AP compared to MBP-MdWRKY17WT. (I) The phosphorylation of S61 or S66 in the SP cluster of MdWRKY17 activates MdDMR6 expression in transiently transformed calli. Relative GUS activity was normalized with LUC activity in apple calli transiently transformed with Agrobacterium EHA105 carrying pCAMBIA1301-MdDMR6 pro and 35Spro: LUC, respectively, and co-transformed with pMDC83-MdWRKY17AP/DP/S61A/S61D/S66A/S66D/S77A/S77D/WT. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) using Fisher’s LSD.

Furthermore, in a transient GUS assay, GUS activity driven by the MdDMR6 promoter showed a similar pattern to the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter. Therefore, not only does this binding activate MdDMR6 expression, but the phosphorylation of the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade also promotes the activation of MdDMR6 by MdWRKY17 (Figure 5B;Supplemental Figure S11).

The MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade phosphorylates MdWRKY17 at sites S61/S66/S325/S356, increasing the transcriptional activity of MdWRKY17

To identify the functional phosphorylation sites of MdWRKY17 by MdMPK3 (Figure 5C), we performed liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS). When 83% of the MdWRKY17 sequence was examined, four possible in vitro phosphorylation sites in the SP cluster (S61/S66/T73/S77) and a potential site outside the SP cluster (S325) were identified (Supplemental Figure S12). We mutated the predicted phosphorylation sites (S61/S66/T73/S77/S85/S97) in the SP cluster, unreported S325, and its nearest typical MAPK phosphorylation site (S356) to Ala. In vitro kinase assays indicated that the mutation of MdWRKY17 at sites in the SP cluster resulted in significantly weaker phosphorylation by MdMPK3, while sites S325 and S356 led to weaker phosphorylation as well (Figure 5D).

We incubated recombinant MBP-MdWRKY17AP/DP/S325A/S325D/S356A/S356D/WT proteins with the W-box probe of the MdDMR6 promoter, respectively, in an EMSA. By contrast with MdWRKY17WT, the DNA-binding activities of MdWRKY17DP/S325D/S356D (mimicking the constitutive phosphorylation of MdWRKY17) were higher, but that of MdWRKY17AP/S325A/S356A (mimicking inactive phosphorylation) were lower (Figure 5E). These results suggest that SP cluster, S325, and S356 are important phosphorylation sites of MdWRKY17 by MdMPK3 via enhancing the binding of MdWRKY17 to MdDMR6 promoter.

We also conducted an in vivo test in transiently transformed apple calli to investigate the effect of the phosphorylation of SP cluster, S325, and S356 in MdWRKY17 on MdDMR6 expression. Compared to calli overexpressing MdWRKY17WT-GFP, in transiently transformed calli overexpressing MdWRKY17DP/S325D/S356D-GFP, GUS expression driven by the MdDMR6 promoter were 5, 2, and 3 times higher, respectively (Figure 5F;Supplemental Figure S13A). Therefore, the phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 at SP cluster, S325, and S356 by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade enhances the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter and promotes the activation of MdDMR6 by MdWRKY17.

To further explore the major phosphorylation sites in MdWRKY17 SP cluster, similar in vitro kinase assay, EMSA assay, and in vivo transcriptional activity assay in transiently transformed calli described above were conducted, respectively, with MdWRKY17S61/S66/S77 mutated at the typical phosphorylation sites, which were identified by LC–MS. The mutated S-61 or S-66 sites resulted in substantially weaker phosphorylation by MdMPK3 (Figure 5G) and also significantly changed DNA-binding activities of MdWRKY17 to MdDMR6 promoter (Figure 5H). Furthermore, MdWRKY17DP-GFP, MdWRKY17S61D-GFP, and MdWRKY17S66D-GFP increased GUS expression driven by the MdDMR6 promoter to 7, 4, and 5 times of that in calli overexpressing MdWRKY17WT-GFP or MdWRKY17S77D-GFP, respectively (Figure 5I;Supplemental Figure S13B).

Taken together, the phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 at S-61, S-66 (in the SP cluster), S-325, and S-356 (outside SP cluster) by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade, respectively, enhances the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter and promotes the activation of MdDMR6 by MdWRKY17.

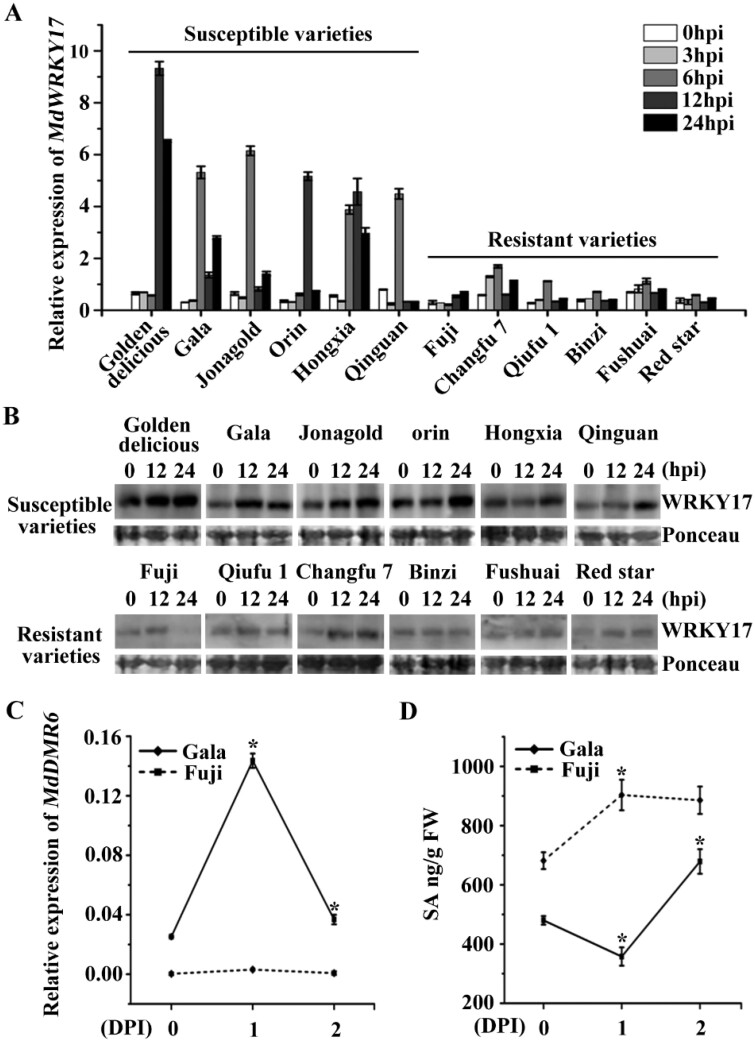

The MdWRKY17 level is critical for C. fructicola resistance via regulating SA degradation

To elucidate the molecular basis of GLS resistance in apple, we analyzed the transcript and protein level of MdWRKY17 in 12 GLS susceptible or tolerant apple germplasms. As shown in Figure 6, A and B, the MdWRKY17 transcript and protein levels were significantly higher in susceptible apple germplasms than the tolerant ones after infection. Furthermore, we analyzed the expression of MdDMR6 and SA levels in the GLS susceptible apple cultivar “Gala” and GLS tolerant cultivar “Fuji” after C. fructicola infection. In “Gala,” RT-qPCR analysis indicated that MdDMR6 expression increased nearly seven-fold and SA levels decreased to 73% after 1 d of C. fructicola infection. By contrast, in “Fuji,” the MdDMR6 expression was nearly unchanged, and SA levels increased 32% (Figure 6, C and D). These results suggest that the significant decrease in SA levels in “Gala” upon C. fructicola infection primarily results from MdWRKY17-mediated upregulation of MdDMR6, which accelerates SA degradation and promotes GLS susceptibility in this apple cultivar (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

The MdWRKY17 level is critical for C. fructicola resistance via regulating SA degradation. (A) Relative expression of MdWRKY17 detected by RT-qPCR in six GLS-resistant germplasms (“Fuji,” “Changfu-7,” “Qiufu-1,” “Binzi,” “Fushuai,” and “Red star”) and six GLS-susceptible germplasms (“Golden delicious,” “Gala,” “Jonagold,” “Orin,” “Hongxia,” and “Qinguan”) at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after C. fructicola infection. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. (B) MdWRKY17 protein levels were substantially higher in six susceptible germplasms than the resistant ones after C. fructicola infection. (C) MdDMR6 was significantly increased in the leaves of the susceptible cultivar “Gala” and nearly unchanged in resistant cultivar “Fuji” by 1 day after C. fructicola inoculation, as revealed by RT-qPCR. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (Student’s t test): *P < 0.05. (D) SA levels were significantly increased in the leaves of the resistant cultivar “Fuji” and decreased in the leaves of the susceptible cultivar “Gala” by 1 d after C. fructicola inoculation. Data are means ± SD of triplicate experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (Student’s t test): *P < 0.05.

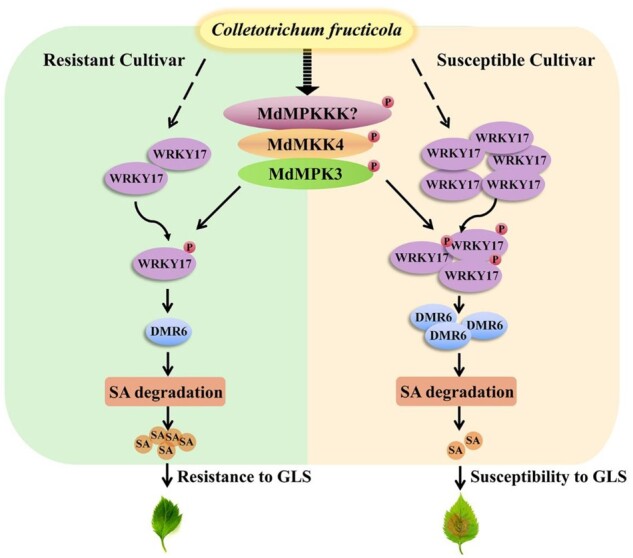

Figure 7.

A model of the MdMEK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6-SA pathway-mediated GLS response in apple. C. fructicola-triggered phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 by MAP kinase kinase 4 (MdMEK4)-MAP kinase 3 (MdMPK3) cascade enhances the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter and activates its expression to promote SA degradation. In the susceptible cultivar “Gala,” C. fructicola infection increases MdWRKY17 protein levels, thereby inducing the MdMEK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6-SA pathway to accelerate SA degradation, resulting in GLS susceptibility. By contrast, in the resistant cultivar “Fuji,” the MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 mediated SA degradation is not fully triggered to induce GLS susceptibility.

Discussion

Frequent outbreaks of GLS, one of the most economically damaging apple diseases in China, have occurred over the past decade. GLS has been detected in almost all apple-producing areas, resulting in crop losses ranging from 30% to 70% (Zhang et al., 2008). However, the molecular mechanism underlying GLS resistance in apple is poorly understood. Therefore, in this study, we explored this molecular mechanism in “Gala,” a popular apple cultivar that is widely planted worldwide and is highly susceptible to GLS. Our findings provide insight into the GLS resistance mechanism in apple.

Since apple trees are perennial woody plants, long-term resistance to pathogen relies on the coordination of several complex physiological processes. Transcription factors play central roles in receiving upstream signals and regulating downstream genes expression during pathogen responses. WRKY transcription factors play important roles in plant resistance to various fungal diseases in apple (Fan et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019a). Therefore, in this study, we identified WRKY genes in apple to explore the GLS resistance mechanism. Among the selected nine candidate MdWRKY genes, MdWRKY17, most significantly induced by C. fructicola, was further researched (Figure 1, A and B). Overexpression of MdWRKY17 in transgenic “Gala” plants increased GLS susceptibility, whereas RNAi-mediated silencing of MdWRKY17 in “Gala” plants enhanced GLS tolerance (Figure 1, C and D). Therefore, the role of MdWRKY17 in GLS tolerance is a susceptibility factor, in opposite of another WRKY, MdWRKY100, which positively controls GLS tolerance (Zhang et al., 2019a).

It is critical for MdWRKY17 to receive the GLS signal for subsequent reactions. The MdWRKY17 phosphorylation is induced by GLS, suggesting GLS signaling is possibly mediated by phosphorylation (Figure 2A;Supplemental Figure S12). Many diseases signaling involves WRKY phosphorylation, such as WRKY33 phosphorylated by the MAPK cascades in B. cinerea signaling (He et al., 2019) and NbWRKY8 phosphorylated by the SIPK/WIPK in P. infestans and Colletotrichum orbiculare signaling (Ishihama et al., 2011). To isolate the kinase for MdWRKY17 phosphorylation, MdMPK3 was identified via yeast screening assay using MdWRKY17-pGADT7 as the bait. Furthermore, MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade is identified by BiFC and Co-IP, and demonstrated to be activated by GLS (Figure 2, B–G). MdMPK6 was also significantly activated by GLS inferring its important role in GLS defense, which remains unknown in apple. In vitro kinase assay proved MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade phosphorylates MdWRKY17 (Figure 2H). Taken together, MdWRKY17 is phosphorylated by the C. fructicola-activated MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade, suggesting its possible critical role in GLS signaling via regulating MdWRKY17.

To further identify the possible physiological process regulated by MdWRKY17, the two critical hormones (SA and JA) in regulating disease tolerance were measured in the transgenic plants. Interestingly, SA levels in the overexpression lines were only 68% those of control plants, whereas SA levels in the RNAi lines were 30% higher than the control (Figure 3A), indicating that MdWRKY17 negatively regulates SA levels, resulting in GLS susceptibility. Similarly, in Arabidopsis, the wrky33 mutant has higher SA levels than the wild-type upon B. cinerea infection, suggesting that WRKY33 plays a negative role in regulating SA metabolism (Birkenbihl et al., 2012). By contrast, in apple, MdWRKY100 promotes GLS tolerance and increases the expression of PR2, a typical marker gene regulated by SA, that has thus far not been shown to play a direct role in SA metabolism. Other physiological research also proved SA is critical for GLS tolerance by application of exogenous SA in apple (Zhang et al., 2016).

We investigated the expression of all critical genes involved in SA biosynthesis, degradation, and signaling in transgenic apple by qPCR analysis. Only MdDMR6 expression was significantly activated in all transgenic overexpression lines and downregulated in RNAi lines (Figure 3B;Supplemental Figure S8). EMSA and ChIP-qPCR demonstrated that MdWRKY17 directly binds to the MdDMR6 promoter in vitro and in vivo, respectively (Figure 3, C and D). The overexpression of MdWRKY17 increased the GUS activity driven by MdDMR6 promoter in the transiently transformed calli, confirming MdWRKY17 directly activates the MdDMR6 expression (Figure 3E). MdDMR6 is a homolog of AtDMR6, encoding 2-oxoglutarate-Fe (II) oxygenase, which degrades SA (Zhang et al., 2017). In vitro enzymatic assays indicated that MdDMR6 is a SA hydroxylase that converts SA to 2,5-DHBA (Figure 3F). Although SA degradation has been reported, how SA degradation is transcriptionally regulated was hitherto unknown. Herein, we demonstrated that a WRKY transcription factor directly regulates SA degradation.

To determine whether MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 mediated SA degradation, activated by MdMEK4-MdMPK3, is the key mechanism leading to GLS susceptibility in the overexpression lines, we sprayed these plants with SA firstly. This treatment partially rescued the GLS susceptibility of the transgenic overexpression lines (Figure 4, A and B). This partial reversion inferred that MdWRKY17 might regulate multiple physiological processes for GLS susceptibility. Although exogenous SA could not completely rescue GLS susceptibility, this pretty good reversion confirming SA levels plays a key role in MdWRKY17-mediated GLS susceptibility. In addition, when MdDMR6 was RNA-interfered in the overexpression lines, the declined MdDMR6 and therefore increased SA also rescued GLS susceptibility, proving this SA-decrease is mainly mediated by MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 pathway (Figure 4, C–F). Finally, the decrease of MdDMR6, increase of SA and reversed GLS susceptibility were also created by RNA-interfered MdMPK3 in the overexpression lines, suggesting MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 mediated SA degradation, activated by MdMEK4-MdMPK3, is critical for MdWRKY17-mediated GLS susceptibility (Figure 4, G–J). Taken together, MdMEK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 mediated SA degradation is the key mechanism leading to GLS susceptibility in MdWRKY17 overexpression lines.

To elucidate how the MdMPK3 cascade regulates MdWRKY17-mediated SA degradation, further ChIP-qPCR and in vivo expression assays demonstrated that the constitutive phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade increases the binding of MdWRKY17 to the MdDMR6 promoter, thereby increasing MdDMR6 expression (Figure 5, A and B). These findings imply that MdDMR6 expression and SA degradation are triggered by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade, a process mediated by MdWRKY17. Although no evidence directly implicating MPK3 in SA metabolism is currently available, MPK3 was shown to play a pivotal role in SA-mediated priming of plants for disease resistance (Beckers et al., 2009). In this study, we clearly revealed the role of MdMPK3 in regulating MdWRKY17-mediated SA degradation.

We identified S-61, S-66, T-73, and S-77 in the SP cluster and S-325 as the phosphorylation sites of MdWRKY17 by LC–MS (Supplemental Figure S11), and confirmed this result by an in vitro kinase assay with point-mutated MdWRKY17 (Figure 5, D and G). EMSA and an in vivo transcriptional activity assay using inactivated or constitutively activated MdMEK4-MdMPK3 further confirmed that these sites are functional phosphorylation sites that regulate MdWRKY17-mediated MdDMR6 transcription (Figure 5, E, F, H, and I). The phosphorylation sites (S-61 and S-66) in the SP cluster are well known (Mao et al., 2011), but the two functional SP sites (S-325 and S-356) outside the SP cluster for the phosphorylation of WRKY by the MAPK cascade have not previously been reported.

To elucidate the molecular basis for GLS resistance in apple, we analyzed the transcript and protein level of MdWRKY17 in six GLS susceptible and six tolerant apple germplasms. The MdWRKY17 transcript and protein levels were significantly higher in susceptible apple germplasms than the tolerant ones after infection (Figure 6, A and B). Taken together with the undifferentially activated MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade between susceptible and tolerance cultivars (Supplemental Figure S5), the amount of MdWRKY17 plays the critical role in GLS tolerance. In the battle of C. fructicola and susceptible apple, MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade is activated normally. But somehow MdWRKY17-MdDMR6, is switched on possibly via unknown hijack mechanism, indicated by the dramatically increased MdWRKY17 resulting in SA degradation and GLS susceptibility.

Finally, the MdDMR6 expression and SA levels regulated by MdWRKY17 were also detected in the GLS susceptible cultivar “Gala” and tolerant cultivar “Fuji” after C. fructicola infection. In susceptible “Gala,” MdDMR6 expression increased sharply and SA levels decreased rapidly within 1 d of C. fructicola infection, whereas in tolerant cultivar “Fuji,” MdDMR6 expression was nearly unchanged and SA levels rapidly increased in response to the same treatment (Figure 6, C and D). SA levels are determined by both SA biosynthesis and degradation (Zhang et al., 2017; Maruri-López et al., 2019). However, the SA biosynthesis-related genes MdICS1, MdEDS1, and MdPAD4 are not regulated by MdWRKY17 (Supplemental Figure S8). Therefore, the decrease in SA levels mainly results from elevated MdDMR6 expression via the regulation of C. fructicola-induced MdWRKY17 in susceptible “Gala.” In the tolerant cultivar “Fuji,” the nearly unchanged MdWRKY17 and MdDMR6 expression might have no significant effect in SA degradation.

Taken together, our in vivo and in vitro data indicated that the MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 pathway is a major factor leading to the GLS susceptibility of “Gala” apple.

Conclusion

Here we identified MdMEK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6, a critical regulatory pathway that promotes SA degradation in the GLS susceptible apple cultivar “Gala.” We uncovered a rapid regulatory mechanism of a previously unknown aspect of GLS susceptibility (Figure 7). Furthermore, we generated a GLS-resistant “Gala” line in which MdWRKY17 was silenced via RNAi. Our finding should contribute to the molecular breeding of apple varieties with increased resistance to C. fructicola.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

“Gala” (M. domestica Borkh. cv “Royal Gala”) and “Fuji” (M. domestica Borkh. cv “Red Fuji”) apple plants were cultured in vitro as described previously (Zhang et al., 2019b). The transgenic apple plants with overexpression or RNA-interference of MdWRKY17 and control plants were rooted and transplanted as described by Zheng et al. (2018). Calli derived from “Gala” embryos were cultured on MS medium containing 1.5 mg L−1 2, 4-D, and 0.4 mg L−1 6-BA at 25°C in darkness and sub-cultured every 2 weeks.

Leaf (4 cm in length) samples for RT-qPCR and SA measurements were collected at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after incubation with C. fructicola as described by Meng et al., (2018) from 12 9-year-old apple germplasms, including six GLS-resistant germplasms (“Fuji,” “Changfu-7,” “Qiufu-1,” “Binzi,” “Fushuai,” and “Red star”) and six GLS-susceptible germplasms (“Golden delicious,” “Gala,” “Jonagold,” “Orin,” “Hongxia,” and “Qinguan”) in the National Germplasm Repository of Apple (Institute of Pomology of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, CAAS, Xingcheng, Liaoning Province, China).

Preparation of C. fructicola spore suspensions and inoculation

C. fructicola was grown on potato dextrose agar medium at 25°C for 1 week, and the fungal spores were suspended in sterile water at a concentration of 1 × 106 cfu mL−1 for fungal inoculation, as measured by microscopy (Olympus CX31RTSF, Tokyo, Japan).

The leaves (1.5 cm in length) of in vitro-cultured apple plants or the leaves (4 cm in length) of field-grown “Gala” apple plants were sprayed with spore suspension, incubated in Petri dishes containing moist filter paper at 25°C, and then sampled at 0, 12, and 24 h after infection for the detection of MdWRKY17 phosphorylation, or sampled at 0, 6, and 12 h after infection for the detection of MdWRKYs expression. Similarly, for the detection of MdWRKY17 expression and protein levels, the leaves of 12 field-grown apple germplasms were inoculated with C. fructicola and sampled at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after infection. And for the detection of MdMPK activity, the leaves (1.5 cm in length) of in vitro-cultured “Gala” and “Fuji” plants were inoculated with C. fructicola and sampled at 0, 6, and 12 h after infection.

To phenotype transgenic apple plants with overexpression or RNA-interference of MdWRKY17, the leaves from transgenic and control plants were inoculated with a 10 μL spore suspension on the center as described by Zhang et al. (2018). Similarly, to explore the effect of MdMEK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17-MdDMR6 mediated SA degradation to GLS susceptibility, the leaves from transgenic and control plants were inoculated with spore suspension as described above, 2 d after spraying with 0.1 mM SA. Additionally, the leaves of transgenic plants with overexpressed MdWRKY17 were inoculated with spore suspension, 3 d after transiently RNA-interfered MdDMR6 or MdMPK3, respectively, for phenotyping. Each experiment was independently repeated 3 times.

RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR analysis was performed to detect the expression of MdWRKY genes in susceptible apple variety “Gala” and the expression of MdWRKY17 in 12 apple germplasms in response to C. fructicola infection. After C. fructicola incubation, 10 leaves were collected for RNA extraction and RT-qPCR assays as described previously (Zheng et al., 2018). The primer sequences used for RT-qPCR are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Similarly, RT-qPCR was performed to examine the expression of MdWRKY17 and SA signaling/biosynthetic/catabolic genes (MdEDS1-1, MdEDS1-2, MdPAD4-1, MdPAD4-2, MdICS1-1, MdICS1-2, and MdDMR6) in transgenic and control plants, and the expression of MdDMR6 at 0, 1, and 2 d in response to C. fructicola infection in field-grown resistant “Fuji” and susceptible “Gala.” Each experiment was independently repeated 3 times.

Measuring MdWRKY17 levels after C. fructicola infection

The coding sequence of MdWRKY17 was inserted into pHM4 to generate MBP-MdWRKY17 (primers listed in Supplemental Table S2). The expression and purification of MBP-MdWRKY17 protein and creation of the polyclonal antibody against MBP-MdWRKY17 protein were performed as described by Zheng et al. (2018). All polyclonal antibody work was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations approved by Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission.

Samples (∼200 mg) of leaf tissue were collected from susceptible “Gala” at 0, 12, and 24 h of incubation with C. fructicola for protein extraction and immunoblot analysis using anti-MdWRKY17 antibody (rabbit,1:2,000) as described by Zheng et al. (2018). The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Subcellular localization of MdWRKY17

The coding sequence of MdWRKY17 was subcloned into the pMDC83 vector to express MdWRKY17-GFP fusion protein (primers listed at Supplemental Table S2). The N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with GV3101 carrying 35S::MdWRKY17-GFP for fluorescence images according to Zheng et al. (2018).

Transcriptional activation assays in yeast

The MdWRKY17 coding region was inserted into the pGBKT7 vector (primers listed at Supplemental Table S2) for the transcriptional activation assay in yeast as described by Zheng et al. (2018).

Phylogenic tree construction

Phylogenetic trees of MdWRKY17 and MdDMR6 were constructed using the homologous genes blasted at NCBI website, respectively in Arabidopsis (A. thaliana), rice (Oryza sativa), tobacco (N. benthamiana), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), poplar (Populus sp.), apple for MdWRKY17, and in Arabidopsis, soybean (Glycine max), apple (M. domestica Borkh.), and grape (V. vinifera) for MdDMR6, as described by (Falcone Ferreyra et al., 2015).

The multiple alignments of MdWRKY17 were performed with DNAMAN to analysis the shared domains in Arabidopsis, rice, and apple.

Generating and phenotyping transgenic “Gala” plants with overexpression or RNA interference of MdWRKY17

The MdWRKY17 coding region was amplified and inserted into the pBI121 and PK7WIWG2D vectors to generate MdWRKY17-GUS for overexpression and MdWRKY17-PK7WIWG2D for RNA interference (primers listed in Supplemental Table S2). Transfection into Agrobacterium strain EHA105 and agrobacterium-mediated transformation of “Gala” were described previously (Zheng et al. 2018).

To phenotype transgenic apple plants with overexpression or RNA-interference of MdWRKY17, the leaves of transgenic and control plants were inoculated as described above. The disease symptoms in the leaves were scored based on the lesion size (Class 0, no symptoms; Class 1, <2 mm; Class 2, from 2 to 6 mm; Class 3, from 6 to 10 mm; Class 4, from 10 to 14 mm; and Class 5, >14 mm) 4 d later, as described previously (Meng et al.,2018).

To find the effects of exogenous SA on GLS tolerance in transgenic plants overexpressing MdWRKY17, the leaves of transgenic plants 2 d after spraying with 0.1 mM SA were inoculated as described above. Four days later, all SA-treated and untreated control leaves were photographed for symptom analysis as described above.

Measuring the effects of C. fructicola infection on MdWRKY17 phosphorylation

MdWRKY17 was immunoprecipitated and quantified with anti-MdWRKY17 antibody or anti-Flag antibody as described by Li et al. (2020) from total proteins extracted from 400 mg leaf tissue from transgenic plants or transiently transformed calli overexpressing MdWRKY17 at 0, 12, and 24 h after C. fructicola infection. The phosphorylation of quantified MdWRKY17 was detected by immunoblotting with p-Ser/Thr antibody (mouse, 1:2,000) as described above, and quantified MdWRKY17 was shown by Western blot. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Isolation of the kinase for MdWRKY17 phosphorylation

Y2H screening assays were performed to identify the candidate kinase for MdWRKY17 phosphorylation using MdWRKY17-pGADT7 as the bait as described by An et al. (2020). RNA was extracted from C. fructicola infected apple leaves. An apple library was constructed (Shanghai OE Biotech Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), which was subsequently mixed with MdWRKY17-pGAD and transformed into yeast cells. The cDNA fragments of transformed yeast strains that survived in the SD‐Trp/‐Leu/‐His/‐Ade (‐T/‐L/‐H/‐A) medium were identified by sequencing.

MAPK assay

To analyze MdMPK activity after C. fructicola incubation, proteins were extracted from the leaves (1.5 cm in length) of in vitro-cultured “Gala” and “Fuji” plants at 0, 6, and 12 h after incubation with C. fructicola. MdMPK activities were detected by immunoblotting with Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) antibody. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Y2H assay

The coding sequences of MdWRKY17 and MdMPK3 were amplified and inserted into pGADT7 and pGBKT7, respectively (primers are listed in Supplemental Table S2). The Y2H assay was performed as described by Meng et al. (2018). The combination of pGADT7-MdWRKY9 and pGBKT7-MdMPK3 was used as a negative control.

BiFC assay

The coding sequence of MdMPK3 was amplified and inserted into the 35S: pSPYCE-cYFP vector, whereas MdWRKY17 was inserted into 35S: pSPYNE-nYFP. The in vivo interaction of pSPYNE-MdWRKY17 and pSPYCE-MdMPK3 was detected by BiFC as described by Li et al. (2020). The Confocal imaging was performed using a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope FV3000 (OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan). GFP was excited at 488 nm. Images were obtained at 480 V HV, 42% Exposure Rate, 1.000× Gain, and 5% Offset. The combination of pSPYNE-MdWRKY9 and pSPYCE-MdMPK3 was used as a negative control. Furthermore, MdMPK3 was used to explore its interactions with all the five MdMEKs in apple (MdMEK2/3/4/6/9) by BiFC. The combination of pSPYCE-MdMPK3 and pSPYNE-MdMEK6 was used as negative control. The primers used for vector construction are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Co-IP assay

The coding sequences of MdWRKY17 and MdMEK4 were cloned into pCAMBIA1307 vector containing a 6×Myc tag, and MdMPK3 subcloned into pCAMBIA1300 vector containing a 3×Flag tag, respectively. The Agrobacterium EHA105 strain carrying pCAMBIA1300-MdMPK3 were co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves with pCAMBIA1307-MdWRKY17, or pCAMBIA1307-MdMEK4, respectively, to detect the in vivo interaction between MdWRKY17 and MdMPK3, MdMPK3, and MdMEK4 by Co-IP assay in N. benthamiana according to Li et al. (2020).

In vitro kinase assay

The constitutively active kinase variant MdMEK4DD and the kinase-negative variant MdMEK4KR (created by site-directed mutagenesis), MdMPK3, and the kinase-dead form MdMPK3AEF (T196A/Y198F) coding sequences were inserted into pET28a for HIS-tagged recombinant protein expression and purification. Primers used for mutagenesis and vector construction are listed in Supplemental Table S2. Briefly, 75 μg MdWRKY17 and 7.5 μg MdMPK3/MdMPK3AEF were incubated with 0.5 μg recombinant MdMEK4DD/MdMEK4KR, respectively, and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay as described by Li et al. (2020). Finally, the phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 was detected by immunoblotting with p-Ser/Thr antibody as described above. Relative MdWRKY17 protein levels were quantitated by Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining.

The LC–MS identified and predicted phosphorylation sites (AP/S61A/S66A/S77A/S325A/S356A) of MdWRKY17 by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade were confirmed by in vitro kinase assays with possible phosphor-inactive MdWRKY17 mutants (MdWRKY17AP/S61A/S66A/S77A/S325A/S356A) and MdMPK3 constitutively activated by MdMEK4DD as described above. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Detection of SA and JA contents

SA was extracted from 100 mg leaf tissue (1.5 cm in length) from transgenic and control plants and leaf samples (4 cm in length) collected from field-grown susceptible “Gala” and resistant “Fuji” apple varieties at 0, 1, and 2 d after C. fructicola inoculation. Methyl salicylate (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) was used as an internal standard. The samples were analyzed by HPLC as described by Zhou et al. (2019).

JA was extracted from 0.5 g leaf tissue (3 cm in length) of transplanted transgenic and control plants. The detection of JA was carried out by an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described previously (Yang et al., 2001). Each experiment was independently repeated 4 times.

ChIP-qPCR assay

Polyclonal antibody of MdWRKY17 protein was prepared according to Zheng et al. (2018). ChIP-qPCR assays of transgenic and control apple plants were performed with anti-MdWRKY17 antibody as described by Zheng et al. (2018). The primers were designed based on the sequence of the MdDMR6 promoter (Supplemental Table S2). The experiments were performed in triplicate.

EMSA

EMSAs using MBP-MdWRKY17 protein and the 5' biotin-labeled MdDMR6 promoter fragment containing the W-box or mutant W-box were performed as described by Zheng et al. (2018), with unlabeled DNA sequences used as a competitor.

To detect the functional MdWRKY17 phosphorylation sites for its binding to the MdDMR6 promoter, EMSAs were performed using wild-type and mutated MBP-MdWRKY17 mimicking nonphosphorylated MdWRKY17S61A/S66A/S77A/AP/S325A/S356A and mimicking constitutively phosphorylated MdWRKY17S61D/S66D/S77D/DP/S325D/S356D as described above. Each experiment was independently repeated 3 times.

Detecting the regulation of MdMPKK4-MdMPK3-MdWRKY17 pathway on MdDMR6 expression in transiently transformed apple calli

To detect the effect of MdWRKY17 overexpression on MdDMR6 expression, a GUS assay was performed using apple calli that were transiently transformed with Agrobacterium EHA105 carrying pCAMBIA1301-MdDMR6pro and 35Spro: LUC co-transformed with pMDC83-MdWRKY17 or pMDC83 as described by Zheng et al. (2018). The 35Spro: LUC was used as an internal control. The GUS and LUC activities were quantified as described by Zheng et al. (2018). The promoter activity was determined by GUS/LUC ratio. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

To examine the effect of MdWRKY17 phosphorylation by the MdMPKK4-MdMPK3 cascade on MdDMR6 expression, apple calli were transiently transformed with Agrobacterium EHA105 carrying MdWRKY17-GFP, MdDMR6pro: GUS, and 35Spro: LUC co-transformed with pCAMBIA1300-MdMEK4DD/KR, pZH01-MdMPK3, or pCAMBIA1300, respectively, as described above. The protein level and phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 were detected by immunoblotting with MdWRKY17 antibody and p-Ser/Thr antibody, respectively.

Similarly, the functional MdWRKY17 phosphorylation sites that regulate MdDMR6 expression were identified in apple calli transiently transformed with Agrobacterium EHA105 carrying pCAMBIA1301-MdDMR6pro and 35Spro: LUC co-transformed with wild-type and mutated MdWRKY17 at the possible phosphorylation sites (pMDC83-MdWRKY17DP/AP/S61D/S61A/S66D/S66A/S77D/S77A/S325D/S325A/S356D/S356A/WT) as described above. The relative expression of MdWRKY17 was detected via RT-qPCR. Each experiment was independently repeated 3 times.

The isolation of the functional phosphorylation sites of MdWRKY17 made it available to confirm the induced phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 by GLS (Figure 2A) Apple calli were transiently transformed with Agrobacterium EHA105 carrying Flag-MdWRKY17WT or Flag-MdWRKY17AP, respectively. Flag-MdWRKY17WT and Flag-MdWRKY17AP were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag agarose beads from transiently transformed apple calli collected at 0, 12, and 24 h after C. fructicola infection, which were quantified by immunoblot analysis using Anti-Flag antibody and then used for phosphorylation detection by immunoblotting with p-Ser/Thr antibody.

Measuring MdDMR6 enzyme activity

The coding sequence of MdDMR6 was amplified and inserted into pGEX-6P-1 for GST-MdDMR6 expression and purification as described above. Kinetics analysis of MdDMR6 enzyme activity was performed as described in Zhang et al. (2017), with some modifications. Briefly, 30 μg GST-MdDMR6 was incubated with various concentrations (0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 μM) of SA in 100 μL reaction mixtures at 30°C for 30 min. Following centrifugation for 10 min at 13,000 rpm at 4°C, 2,5-DHBA levels were measured by HPLC as described above. Km and Vmax were determined using GraphPad Prism version 7 software (www.graphpad.com) using nonlinear regression for the Michaelis–Menten equation. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

RNA interference of MdDMR6 or MdMPK3 in apple leaves by Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation

To identify if SA degradation in transgenic MdWRKY17 overexpression lines is mainly mediated by MdWRKY17-MdDMR6, pZH01-MdDMR6 was generated for RNA interference. The specific primers were listed at Supplemental Table S2. RNA interference of MdDMR6 was performed by transiently transforming leaves of transgenic “Gala” plants overexpressing MdWRKY17 using Agrobacterium strain EHA105 carrying pZH01-MdDMR6, as described by Zhang et al. (2018). MdDMR6 expression and SA content were detected 3 d after transient transformation, and GLS tolerance was recorded 4 days after infection as described above. The experiment was independently repeated 3 times.

Similarly, to confirm MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade regulated SA degradation and GLS susceptibility via MdWRKY17 mediated MdDMR6 expression, RNA interference of MdMPK3 was performed by transiently transforming leaves of transgenic “Gala” plants overexpressing MdWRKY17 using Agrobacterium strain EHA105 carrying pZH01-MdMPK3 as described above. MdMPK3, MdDMR6, and MdPR1 expression, SA content 3 d after transient transformation, and tolerance to C. fructicola 4 d after infection were detected as described above. The experiment was independently repeated 3 times.

LC–MS

The phosphorylation sites of MdWRKY17 by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade were identified by LC–MS. Briefly, 100 μg MdWRKY17 protein and 10 μg recombinant MdMPK3 protein were incubated with 1 μg recombinant MdMEK4DD/MdMEK4KR for the reaction, digested by chymotrypsin, and detected as described by Li et al. (2020).

ChIP-qPCR analysis of transiently transformed apple calli

To detect the effect of MdWRKY17 phosphorylation by the MdMEK4-MdMPK3 cascade on its binding to the MdDMR6 promoter, pCAMBIA1300-MdMEK4DD/MdMEK4KR were generated for overexpression and pZH01-MdMPK3 for RNA interference. Apple calli were transiently transformed with Agrobacterium EHA105 carrying pMDC83-MdWRKY17 co-transformed with pCAMBIA1300-MdMEK4DD, pCAMBIA1300-MdMEK4KR, pZH01-MdMPK3, or pCAMBIA1300 as described by Zheng et al. (2018). Calli transformed with pCAMBIA1300 and pMDC83 were used as the control. ChIP-qPCR was performed as described by Meng et al. (2018). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Accession numbers

MdWRKY4, Md16G1066500; MdWRKY17, Md12G1181000; MdWRKY18, Md15G1039500; MdWRKY40, Md09G1224500; MdWRKY51, Md15G1331300; MdWRKY53, Md16G1066500; MdWRKY60, Md17G1223100; MdWRKY70, Md01G1168600; MdWRKY100, Md03G1057400; MdDMR6, Md10G1053200; MdMPK3, Md11G1121500; MdICS1-1, Md06G1188700; MdICS1-2, Md14G1195500; MdPAD4-1, Md15G1136300; MdPAD4-2, Md17G1039700; MdEDS1-1, Md02G1099600; MdEDS1-2, Md05G1133000; MdPR1, Md15G1277700; MdActin, Md01G1001600.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. MdWRKY17 is a transcriptional activator localized in the nucleus.

Supplemental Figure S2. The phylogenetic tree of MdWRKY17.

Supplemental Figure S3. Bioinformatic analysis of MdWRKY17.

Supplemental Figure S4. MdWRKY17 expression in transgenic lines.

Supplemental Figure S5. Phosphorylation of MdWRKY17 was activated by GLS in apple.

Supplemental Figure S6. The variation of MAPKs activity after C. fructicola infection.

Supplemental Figure S7. Co-localization between MdMPK3 and MdMEKs by BiFC assays.

Supplemental Figure S8. Levels of JA in the leaves of transgenic and control apple plants.

Supplemental Figure S9. Relative expression of SA signaling and biosynthetic genes in transgenic apple plants.

Supplemental Figure S10. The phylogenetic tree of MdDMR6.

Supplemental Figure S11. MdWRKY17 phosphorylation by MdMEK4-MdMPK3.

Supplemental Figure S12. Potential phosphorylation sites of MdWRKY17.

Supplemental Figure S13. Relative expression of MdWRKY17 in transiently transformed apple calli.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used for RT-qPCR.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used for vector construction, site mutation, EMSA, and ChIP-qPCR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Guangyu Sun in Northwest A&F University for providing the C. fructicola strain.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research & Development Program of China (SQ2018YFD1000300, 2019YFD1000104), National Natural Science Fund (No. 31772279, U1803105) and 111 Project (B17043).

Conflict of interest statement. There is no conflict of interest.

J.K. planned and designed the research. D.S., C.W., X.Z., Z.H., Y.Z., Y.Z., A.J., H.Z., K.S., Y.B., T.Y., L.W., Y.S., J.L., Z.Z., and Y.G. performed experiments, conducted fieldwork, and analyzed the data. D.S. and J.K. wrote the manuscript.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Jin Kong (jinkong@cau.edu.cn).

References

- Adachi H, Nakano T, Miyagawa N, Ishihama N, Yoshioka M, Katou Y, Yaeno T, Shirasu K, Yoshioka H (2015) WRKY transcription factors phosphorylated by MAPK regulate a plant immune NADPH oxidase in Nicotiana benthamiana .Plant Cell 27: 2645–2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J, Wang X, Zhang X, Xu H, Bi S, You C, Hao Y (2020) An apple MYB transcription factor regulates cold tolerance and anthocyanin accumulation and undergoes MIEL1-mediated degradation. Plant Biotechnol J 18: 337–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers GJM, Jaskiewicz M, Liu YD, Underwood WR, He SY, Zhang SQ, Conratha U (2009) Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases 3 and 6 are required for full priming of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21: 944–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkenbihl RP, Diezel C, Somssich IE (2012) Arabidopsis WRKY33 is a key transcriptional regulator of hormonal and metabolic responses toward Botrytis cinerea infection. Plant Physiol 159: 266–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone Ferreyra ML, Emiliani J, Rodriguez EJ, Campos-Bermudez VA, Grotewold E, Casati P ( 2015) The Identification of Maize and Arabidopsis Type I FLAVONE SYNTHASEs Links Flavones with Hormones and Biotic Interactions. Plant Physiol 169: 1090–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H, Wang F, Gao H, Wang L, Xu J, Zhao Z (2011) Pathogen-induced MdWRKY1 in ‘Qinguan’ apple enhances disease resistance. J Plant Biol 54: 150–158 [Google Scholar]

- Frei Dit Frey N, Garcia AV, Bigeard J, Zaag R, Bueso E, Garmier M, Pateyron S, Tauzia-Moreau ML, Brunaud V, Balzergue S et al. (2014) Functional analysis of Arabidopsis immune‐related MAPKs uncovers a role for MPK3 as negative regulator of inducible defences. Genome Biol 15: R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Li G, Yang K, Mao G, Wang R, Liu Y, Zhang S (2010) Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 and 6 regulate Botrytis cinereal-induced ethylene production in Arabidopsis. Plant J 64: 114–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Xu J, Wang X, He X, Wang Y, Zhou J, Zhang S, Meng X (2019) The Arabidopsis pleiotropic drug resistance transporters PEN3 and PDR12 mediate camalexin secretion for resistance to Botrytis cinereal. Plant Cell 31: 2206–2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama N, Yamada R, Yoshioka M, Katou S, Yoshioka H (2011) Phosphorylation of the Nicotiana benthamiana WRKY8 transcription factor by MAPK functions in the defense response. Plant Cell 23: 1153–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite RP, Tsuneta M, Kishino AY (1988) Ocorrencia de mancha foliar de Glomerella em macieira no Estado do Parana. IAPAR. Informe da Pesquisa. IAPAR, Curitiba, Brazil, p. 81

- Li G, Meng X, Wang R, Mao G, Han L, Liu Y, Zhang S (2012) Dual-level regulation of ACC synthase activity by MPK3/MPK6 cascade and its downstream WRKY transcription factor during ethylene induction in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 8: e1002767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhou H, Zhang Y, Li Z, Yang Y, Guo Y (2020) The GSK-like kinase BIN2 is a molecular switch between the salt stress response and growth recovery in Arabidopsis thaliana. Dev Cell 55: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Shang S, Dong Q, Wang B, Zhang R, Gleason ML, Sun G (2018) Transcriptomic analysis reveals candidate genes regulating development and host interactions of Colletotrichum fructicola. BMC Genom 19: 557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Li B, Wang C, Liu C, Kong X, Zhu J, Dai H (2016) Genetics and molecular marker identification of a resistance to glomerella leaf spot in apple. Hortic Plant J 2: 121–125 [Google Scholar]

- Mao G, Meng X, Liu Y, Zheng Z, Chen Z, Zhang S (2011) Phosphorylation of a WRKY transcription factor by two pathogen-responsive MAPKs drives phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 1639–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruri-López I, Aviles-Baltazar NY, Buchala A, Serrano M (2019) Intra and extracellular journey of the phytohormone salicylic acid. Front Plant Sci 10: 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng D, Li C, Park HJ, Gonzalez J, Wang J, Dandekar AM, Turgeon BG, Cheng L (2018) Sorbitol modulates resistance to Alternaria alternata by regulating the expression of an NLR resistance gene in apple. Plant Cell 30: 1562–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Zhang S (2013) MAPK Cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Ann Rev Phytopathol 51: 245–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz PR, Moser T, Höll J, Kortekamp A, Buchholz G, Zyprian E, Bogs J (2015) The transcription factor VvWRKY33 is involved in the regulation of grapevine (Vitis vinifera) defense against the oomycete pathogen Plasmopara viticola. Physiol Plant 153: 365–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Prado JS, Abulfaraj AA, Rayapuram N, Benhamed M, Hirt H (2018) Plant immunity: from signaling to epigenetic control of defense. Trends Plant Sci 23: 833–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton PJ, Somssich IE, Ringler P, Shen QJ (2010) WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci 15: 247–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfferth C, Tsuda K. (2014) Salicylic acid signal transduction: the initiation of biosynthesis, perception and transcriptional reprogramming. Front Plant Sci 5: 697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Febres VJ, Jones JB, Moore GA (2015) Responsiveness of different citrus genotypes to the Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri-derived pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) flg22 correlates with resistance to citrus canker. Mol Plant Pathol 16: 507–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J, Zhang M, Zhang L, Sun T, Liu Y, Lukowitz W, Xu J, Zhang S (2017) Regulation of stomatal immunity by interdependent functions of a pathogen-responsive MPK3/MPK6 cascade and Abscisic acid. Plant Cell 29: 526–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Verk MC, Bol JF, Linthorst HJ (2011) WRKY transcription factors involved in activation of SA biosynthesis genes. BMC Plant Biol 11:89–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Li B, Dong X, Wang C, Zhang Z (2015) Effects of temperature, wetness duration and moisture on the conidial germination, infection, and disease incubation period of Glomerella cingulate. Plant Dis 99: 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Zhang Z, Li B, Wang H, Dong X (2012) First report of glomerella leaf spot of apple ccaused by Glomerella cingulata in China. Plant Dis 96: 912–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Meng J, Meng X, Zhao Y, Liu J, Sun T, Liu Y, Wang Q, Zhang S (2016) Pathogen-responsive MPK3 and MPK6 reprogram the biosynthesis of indole glucosinolates and their derivatives in Arabidopsis immunity. Plant Cell 28: 1144–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue C, Li H, Liu Z, Wang L, Zhao Y, Wei X, Fang H, Liu M, Zhao J (2019) Genome-wide analysis of the WRKY gene family and their positive responses to phytoplasma invasion in Chinese jujube. BMC Genom 20: 464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zhang J, Wang Z, Zhu Q, Wang W (2001) Hormonal changes in the grains of rice subjected to water stress during grain filling. Plant Physiol 127: 315–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Wang F, Yang S, Zhang Y, Xue H, Wang Y, Yan S, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Ma Y (2019a) MdWRKY100 encodes a group I WRKY transcription factor in Malus domestica that positively regulates resistance to Colletotrichum gloeosporioides infection. Plant Sci 286: 68–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Halitschke R, Yin C, Liu C, Gan S (2013) Salicylic acid 3-hydroxylase regulates Arabidopsis leaf longevity by mediating salicylic acid catabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 14807–14812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Ma C, Zhang Y, Gu Z, Li W, Duan X, Wang S, Hao L, Wang Y, Wang S, Li T (2018) A single-nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter of a hairpin RNA contributes to Alternaria alternata leaf spot resistance in apple (Malus × domestica). Plant Cell 30: 1924–1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Wang S, Cui J, Sun G (2008) First report of bitter rot caused by Colletotrichum acutatum on apple in China. Plant Dis 92: 1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]