Abstract

Diatoms are photosynthetic microalgae that fix a significant fraction of the world’s carbon. Because of their photosynthetic efficiency and high-lipid content, diatoms are priority candidates for biofuel production. Here, we report that sporulating Bacillus thuringiensis and other members of the Bacillus cereus group, when in co-culture with the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum, significantly increase diatom cell count. Bioassay-guided purification of the mother cell lysate of B. thuringiensis led to the identification of two diketopiperazines (DKPs) that stimulate both P. tricornutum growth and increase its lipid content. These findings may be exploited to enhance P. tricornutum growth and microalgae-based biofuel production. As increasing numbers of DKPs are isolated from marine microbes, the work gives potential clues to bacterial-produced growth factors for marine microalgae.

Introduction

Diatoms are unicellular photosynthetic algae that perform critical environmental functions with global implications. Thriving in various aquatic environments and equipped with efficient carbon concentration mechanisms, diatoms are among the planet’s most productive microalgae and fix a fifth of global carbon (Amin et al., 2012; Hildebrand et al., 2012). Diatoms fix carbon in the form of lipid droplets, a particularly useful form of biofuels, tolerate harsh environments, and perform well in large-scale cultures (Hildebrand et al., 2012). Because of these features, diatoms are considered as some of the most promising microalgae for biofuel production. Even with these desirable features, a scalable, commercially viable microalga-derived biofuel has not yet been realized. A better understanding of diatom physiology could increase the feasibility of diatom-derived biofuels (Hu et al., 2008; Hildebrand et al., 2012).

Diatoms and marine microorganisms have co-inhabited the oceans for more than 200 million years. The close association and interaction among them are evident by substantial horizontal gene transfer; an estimated 784 genes of bacterial origin are found in the genome of the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Bowler et al., 2008). Beneficial diatom–bacterium interactions through nutrient exchange are well documented, where bacteria provide the diatom with micronutrients, such as vitamin B12 or siderophores for iron uptake, in exchange for dissolved organic matter produced by the diatom (Croft et al., 2005; Boyd and Ellwood, 2010; Foster et al., 2011; Seyedsayamdost et al., 2011; Segev et al., 2016). In addition, natural compounds of marine origin are being explored to probe into diatom physiology and increase lipid production. The two small molecules penicillide and verrucarin J isolated from fungi of marine origin were recently shown to promote neutral lipid accumulation in P. tricornutum but unfortunately inhibited diatom growth (Yu et al., 2020). Increased knowledge on bacterium–diatom interactions may offer new strategies to enhance diatom growth and diatom-derived lipid production.

The Bacillus cereus group of bacteria is Gram-positive, rod-shaped, and spore-forming. They are found in a wide range of habitats from soil to water, from animals to plants, and from sea water to marine sediments (Jensen et al., 2003; Guinebretière et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2017). The strong survivability, adaptation, and wide dispersal were attributed to their metabolic diversity and spore-forming ability (Guinebretière et al., 2008). One important member of the B. cereus group is B. thuringiensis, which is known to produce proteinaceous crystalline toxin against insect larvae and widely used as a biological insecticide (Schnepf et al., 1998). Some B. cereus group bacteria were among those crop-rhizosphere isolates with plant growth-promoting abilities (Raddadi et al., 2008; Ashraf et al., 2019). Their prevalence, availability, and diverse metabolic abilities make B. cereus group bacteria attractive candidates to test for beneficial bacterium–diatom interactions.

In this study, we co-cultured P. tricornutum with several B. cereus group bacteria and showed that the P. tricornutum cell number increases significantly in the co-culture. Focused analyses of the B. thuringiensis–P. tricornutum co-culture revealed that sporulation-mediated cell lysis of B. thuringiensis released a small molecular metabolite capable of stimulating P. tricornutum proliferation by nearly three-fold. Purification of B. thuringiensis mother cell lysate and characterization of the factor led to the identification of two diketopiperazines (DKPs), the smallest possible cyclic peptides made up of only two amino acids, as being responsible for the stimulating activity. Both the B. thuringiensis mother cell lysate and the synthesized DKPs were shown to be capable of increasing lipid production in P. tricornutum. Together, our studies identified two bacterium-derived DKPs—members of a much larger family—that possess activities on the growth of marine diatom P. tricornutum, offering further approaches for enhancing algae-based biofuel production and potential clues to bacterial-produced growth factors for marine microalgae.

Results

Discovery of bacterial-derived factor(s) that induce the growth of P. tricornutum

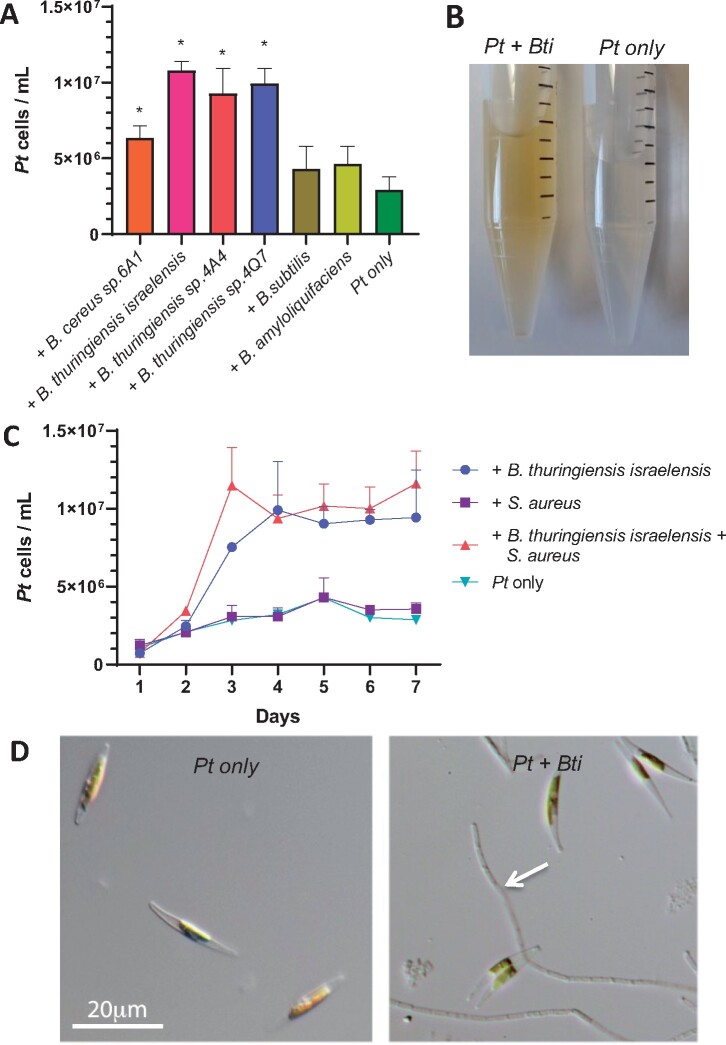

To investigate the effect of B. cereus bacteria on P. tricornutum growth, we tested co-cultures between P. tricornutum and several B. cereus group bacteria, namely B. thuringiensis sp. Israelensis (Bti), B. thuringiensis sp. 4A4, B. thuringiensis sp. 4Q7, and B. cereus sp. 6A1, all of which stimulated P. tricornutum growth (Figure 1A). In contrast, co-culture between P. tricornutum and B. subtilis or B. amyloliquefaciens, two members of the B. subtilis group, did not lead to growth increase (Figure 1A), indicating that the stimulating ability is selective to the B. cereus group. As B. thuringiensis sp. israelensis (Bti) produced a particularly robust stimulation, we focused our study on the B. thuringiensis–P. tricornutum co-culture (Figure 1B and C). We counted P. tricornutum cell numbers daily in the bacterium–diatom co-culture and showed a two- to three-fold increase in P. tricornutum cells at the stationary phase. In the same experiment, we included another Gram-positive bacterium, namely Staphylococcus aureus, either added together with B. thuringiensis or by itself to the P. tricornutum culture. Staphylococcus aureus had no effect on the growth of P. tricornutum (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Bacillus cereus clade of bacteria stimulates P. tricornutum growth during co-culture. A, Bacillus cereus clade members, B. cereus sp. 6A1, B. thuringiensis israelensis (Bti), B. thuringiensis sp. 4A4, and B. thuringiensis sp. 4Q7 as well as Bacillus subtilis clade members, B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens, are tested for their ability to stimulate P. tricornutum (Pt) growth. Pt cells (y-axis) were counted at Day 6 of co-culture. Each culture condition has three biological replicates. Error bars are ±1 SD (Standard Deviation). “*” represents significant difference from “Pt only” (two-tailed Student’s t test: P < 0.05). To control for carryover LB into the co-culture by the bacteria, LB of equivalent volume (100 µL) was added to the L1 medium in the “Pt only” control. B, A tube containing co-culture of Pt and Bti and a tube with Pt in axenic condition (both at Day 5). The brown color tube indicates higher Pt cell density. C, Growth curve of Pt when co-cultured with S. aureus, B. thuringiensis sp. israelensis, both bacteria combined, or under axenic condition (Pt only). The bacteria are added to the Pt culture at Day 1. The Pt cell number (Y-axis) was quantified at each day (X-axis). D, Microscopic images of Pt cells (left) and Pt cells in co-culture (right; both at Day 4). A chain of Bti spores is indicated by an arrow. Both images are at the same magnification; scale bar is 20 µm.

Microscopic examination of the B. thuringiensis-stimulated P. tricornutum co-culture revealed the presence of B. thuringiensis endospores (Figure 1D, arrow), suggesting that B. thuringiensis underwent sporulation under co-culture conditions, where the L1 medium, an enriched seawater medium for algae growth (Guillard and Hargraves, 1993), is likely nutrient poor for the bacteria. This was subsequently confirmed when B. thuringiensis was inoculated into the L1 medium without P. tricornutum and shown to form spores just as in the co-culture.

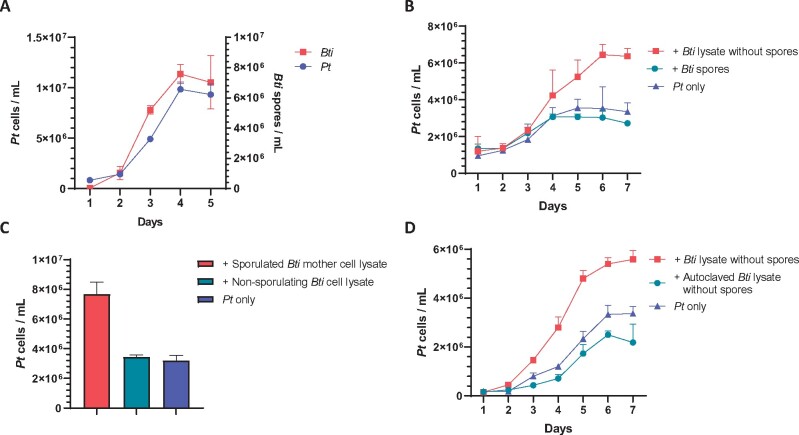

Comparison of P. tricornutum cells and the B. thuringiensis spores over a 5-d period during the co-culture revealed that both P. tricornutum cells and B. thuringiensis spores increased rapidly at Days 2–4 (Figure 2A), suggesting that sporulation directly correlates to the growth of P. tricornutum. In Bacillus, sporulation is accompanied by mother cell lysis (Higgins and Dworkin, 2012), which would release growth stimulating intracellular factors into the culture media. To test this hypothesis, P. tricornutum was treated, respectively, with B. thuringiensis spores or the mother cell lysate, when the spores and cell debris were removed. Growth stimulation was only observed when using the mother cell lysate (Figure 2B). Mechanically lysed B. thuringiensis cells growing in nutrient-rich LB medium (no sporulation), as disrupted by sonication with subsequent filtration, was unable to stimulate diatom growth (Figure 2C). This result supports that sporulation under nutrient-deplete conditions is required for the production of the stimulating factors. The mother cell lysate was heat-treated by autoclaving (121°C, 30 min), which resulted in loss of stimulating activity (Figure 2D). Pretreatment of the B. thuringiensis lysate with Proteinase K did not affect the stimulating effect of the lysate (Supplemental Figure S1). Thus, a small and heat-labile molecule is likely responsible for the growth-promoting effect.

Figure 2.

The mother cell lysate of Bti contains a heat-labile stimulator. A, Pt cell counts (left Y-axis) and Bti spore counts (right Y-axis) in co-cultures, showing correlation between diatom cells and bacterial spores. B, Pt cell counts in culture with Bti mother cell lysate (spores removed), the Bti spores, and Pt only, respectively. C, Pt cell counts in cultures containing sporulated Bti mother cell lysate, nonsporulating Bti cell lysate, and the axenic control (Pt only). Cell counts were done at Day 7 of co-culture. D, Pt cell counts in culture with Bti mother cell lysate, autoclaved B. thuringiensis mother cell lysate, or the axenic control (Pt only). Each culturing condition contained three replicates. Error bars are ±1 SD.

Identification of the growth-stimulating factor(s)

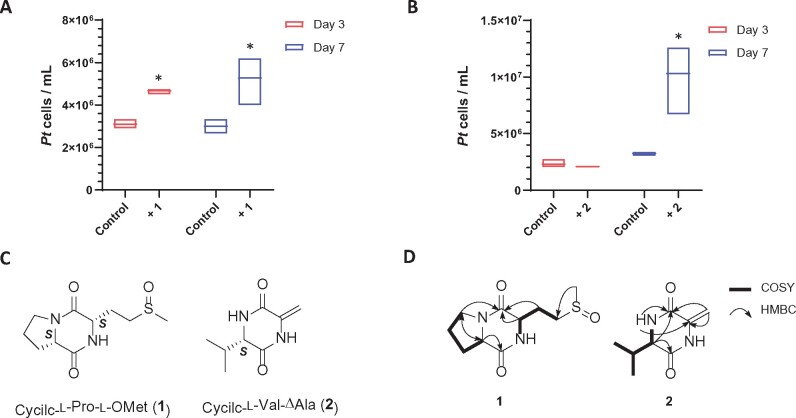

The growth-stimulating factor was captured from the B. thuringiensis mother cell lysate using a mixture of XAD resins, and the crude extract was fractionated into five reduced-complexity fractions using reverse-phase (RP) solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns. Growth-stimulating activity was in the water fraction, indicating that the active small molecules are highly polar. Further fractionation using RP high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) yielded 25 additional fractions, which were screened for growth stimulation of P. tricornutum. Only two fractions exhibited activity (Figure 3 A and B). Comprehensive analysis of UV, mass, and NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) data revealed that the active fractions contained two cyclic dipeptides (1 and 2) belonging to DKP (Figure 3 C and D).

Figure 3.

Identification of two DKPs as the growth simulators from B. thuringiensis. A, The growth enhancing effect of 1 was significant in Days 3 and 7 cultures. B, Significant stimulating effect of 2 was shown in Day 7 culture. Each culturing condition has three biological replicates. Error bars are ±1 SD. “*” indicates significant difference (two-tailed Student’s t test: P < 0.05) between each DKP-stimulated culture and the control. For the controls, MeOH/H2O was added to the L1 medium at the same percentage as the DKP solution. C, Structures of cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) and cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2). D, Key COSY and HMBC correlations of 1 and 2.

Compound 1 was purified as a white powder having a molecular formula of C10H16N2O3S based on high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS; obsd. [M + H]+ m/z 245.0972, Δ 2.8 p.p.m.), a formula that requires four degrees of unsaturation. Interpretation of the 1D and 2D NMR data (1H, 13C, heteronuclear single quantum correlation, homonuclear correlation spectroscopy [COSY], and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation [HMBC]; Supplemental Table S1) of 1 revealed two carboxyl carbons (δC 175.2 and 168.8), two α-carbons (δC 61.7 and 56.4), five aliphatic carbons (δC 50.2, 48.1, 30.4, 25.2, and 24.6), and one singlet methyl (δC 39.2), which make up three distinct spin systems. The first spin system, with COSY correlations between H-3 (δH 3.57), H-4 (δH 2.08/1.98), H-5 (δH 2.36/1.97), and α-proton H-6 (δH 4.36), is indicative of a proline residue. The second spin system contained COSY correlations between an α-methine H-9 (δH 4.53) and two methylenes, H-10 (δH 2.38/2.31) and H-11 (δH 2.97). A key HMBC correlation from the singlet methyl group, H-13 (δH 2.74), to C-11 led to the assignment of the second partial structure as methionine sulfoxide. Additional HMBC correlations from H-9 to C-1 (δC 168.8) and from H-6 to C-7 (δC 175.2) connected the two partial structures and established the planar structure of 1 as cyclic- l-Pro- l-OMet, a DKP (Figure 3, C and D; Supplemental Figure S2–S6).

Compound 2 has a molecular formula of C8H13N2O on the basis of HR-ESI-MS (obsd. [M + H]+ m/z 169.0981, Δ 1.2 p.p.m.) and based on the 1D NMR data 2 appeared to be another DKP (Supplemental Table S2). Analysis of the chemical shifts and UV spectrum indicated 2 incorporated a terminal methylene (δC/δH 98.9/5.17 and 4.76) and geminal dimethyl moiety. Detailed analysis of the 2D NMR dataset revealed the planar structure of 2 is cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (Figure 3, C and D; Supplemental Figure S7–S11).

The absolute stereoconfigurations of the three chiral amino residues in 1 and 2 were determined by Marfey’s analysis. Each DKP was hydrolyzed and then derivatized with 1-fluoro-2-4-dinitrophenyl-5-l-alanine amide (l-FDAA; Szókán et al., 1988). Comparison of the reaction mixture to authentic standards using an high resolution liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (HR-LC-MS) revealed that all amino acids correspond to l-amino acids (Supplemental Table S3 and Supplemental Figures S12 and S13).

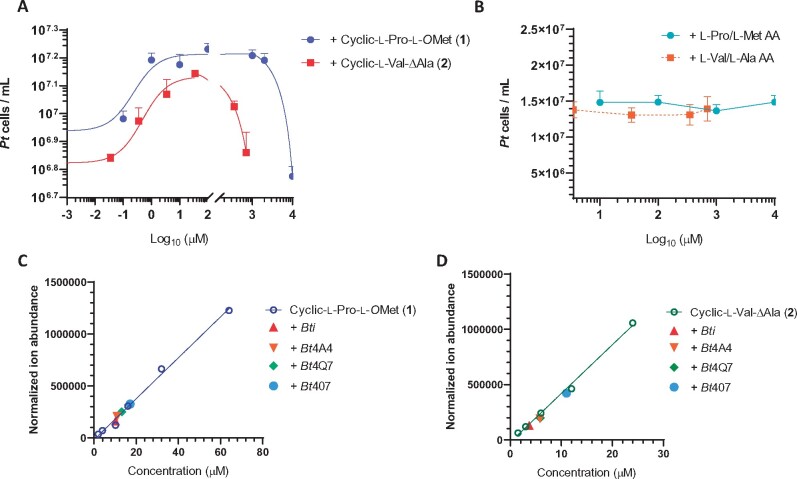

Due to low production yields of both 1 and 2 by the producing bacterium and a desire to rule out an active impurity, we sought an alternative source for each metabolite in order to obtain enough material for unambiguous biological evaluation. Compound 2 was commercially available (Boc Sciences, Shirley, NY, USA; CAS number: 25516-00-1; Supplemental Figures S14 and S15), but we had to synthesize 1. The synthesis involved two steps and traditional peptide-coupling chemistry (Campbell and Blackwell, 2009; Supplemental Figures S16 and S17). Both metabolites stimulated diatom growth in dose-dependent manners with minimal active concentrations of 100 and 35 nM for compounds 1 and 2, respectively (Figure 4A). Importantly, addition of individual amino acids that constitute the DKP’s building blocks, even at high concentrations (0.7–10 mM), had no effect on the diatom growth (Figure 4B). Furthermore, chemical profiling revealed that all growth stimulatory B. thuringiensis strains produced 4–20 µM of both 1 and 2 in spent media, with B. thuringiensis sp. 407 producing the highest amounts of each of the DKPs (Figure 4 C and D).

Figure 4.

The bacteria-derived DKPs (cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet and cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla) stimulate Pt growth in a dose-dependent manner. A, Pt cell numbers when growing in culture containing different concentrations of cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) and cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2). Cell counts were done at Day 7, when effective stimulation was established for both DKPs. B, Solutions containing mixed pair of single l-amino acids (l-Pro/l-Met AA and l-Val/l-Ala AA) failed to stimulate Pt growth at different concentrations. Cell counts were done at Day 8 of culture. Each culturing condition has three biological replicates. Error bars are ±1 SD. C, Absolute quantification of cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) and D, Absolute quantification of cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2) in Bti, B. thuringiensis sp.4A4, B. thuringiensis sp.4Q7, B. thuringiensis sp.407. The calibration curve is also shown.

DKP changes composition and yield of fatty acids in P. tricornutum

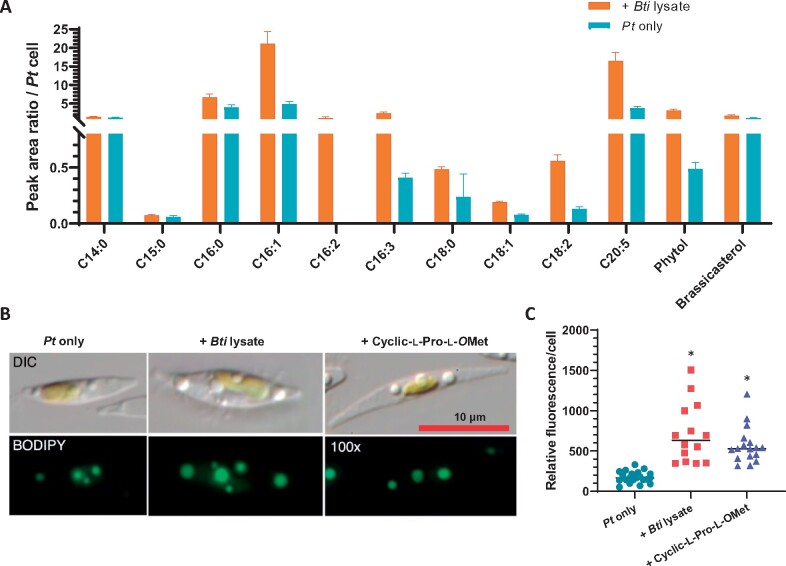

Whereas the B. thuringiensis lysate can effectively and inexpensively increase P. tricornutum growth, it is not known if such treatment would negatively impact lipid production in P. tricornutum. This is important as diatoms are regarded as one of the most promising sources of biofuel. To address this question, the lipid composition and yield were analyzed using gas chromatography–MS (GC–MS) to identify and quantify the fatty acids in cultures stimulated with the B. thuringiensis cell-free lysate. At Day 7, P. tricornutum cells were centrifuged and the pellet was subjected to extraction. The result revealed increased levels of three key components of biodiesel—palmitoleic acid (C16:1), oleic acid (C18:1), and linoleic acid (C18:2)—in B. thuringiensis lysate-stimulated P. tricornutum (Figure 5A), as well as an increase in beneficial dietary lipids, eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5) and palmitoleic acid (C16:1; Figure 5A). Interestingly, all the unsaturated fatty acids increased in relative and absolute abundance, whereas the saturated fatty acids did not (Figure 5A). Shifting to unsaturated fatty acid production and enhanced overall lipid productivity have been reported in P. tricornutum as a stress response upon cold temperature or nitrogen limitation (Jiang and Gao, 2004; Zulu et al., 2018).

Figure 5.

Stimulated Pt cells have higher lipid content and higher yield of beneficial fatty acids. A, Fatty acid fractions of 7-d-old Pt culture grown in L1 medium (Pt only) or L1 medium containing Bti lysate measured by GC–MS. Values represent normalized fatty acid production per cell of each culture as peak area ratio versus the internal standard. Cells of Pt only averaged 4.35E + 06 Pt cells per milliliter, whereas cells of Pt + Bti lysate averaged 1.34E + 07 cells per milliliter. B, DIC microscopy images (top) and fluorescent microscopic images (bottom) of BODIPY-stained Pt cells at stationary phase (12 d). All images are at the same magnification; scale bar is 10 µm. C, Relative Fluorescence/cell (Y-axis) is equal to Integrated Density (see “Methods” section) based on BODIPY staining of Pt cells at stationary phase. Black horizontal bars represent the average Integrated Density of cells in the experimental condition. N = 23 (Pt only), 30 cells (Pt + Bti lysate), and 47 (Pt + cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet).

The effect of the DKP on P. tricornutum lipid composition was also tested by staining stationary phase P. tricornutum cells with BODIPY 505/515, a fluorescent stain for neutral lipids (Wu et al., 2014). Phaeodactylum tricornutum cells grown in L1 medium containing 100 µM cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) or cell-free lysate of B. thuringiensis exhibited higher relative fluorescence per cell than the P. tricornutum control cultured in L1 medium only (Figure 5 B and C). These results suggest that the DKP and B. thuringiensis lysate not only stimulate P. tricornutum growth but also increase neutral lipid accumulation.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that B. cereus group bacteria, upon sporulation and mother cell lysis, release small molecules into their culture medium, and these small molecules possess the ability to stimulate P. tricortunum growth. Bioassay-guided purification led to the identification of two DKPs, cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) and cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2), which are able to exert diatom growth-stimulating effects at nanomolar concentrations. DKPs contain a heterocyclic six-membered ring, which provides metabolic stability, protease resistance, and conformational rigidity (Borthwick, 2012; Giessen and Marahiel, 2015).

DKPs have been isolated from marine-derived bacteria, fungi, mollusks, sponges, and red algae (Huang et al., 2014). l-Val-ΔAla (2) was previously identified from cell-free Pseudomonas aeruginosa culture (Holden et al., 1999). More recently, cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) is among 32 DKPs identified from five bacterial strains isolated from marine sediments (Harizani et al., 2020). However, the biological functions of most of these naturally produced DKPs remain elusive. The only known diatom-derived DKP is a diproline that acts as a pheromone to coordinate attraction and mating in the benthic pennate diatom Seminavis robusta (Gillard et al., 2013). However, sexual reproduction in P. tricornutum is currently not well understood; any similar roles will need further investigation. The marine bacterial quorum-sensing systems, such as the N-acylhomoserine lactones (AHLs) system, regulate cell density-dependent onset of bioluminescence in Vibrios fisheri (Tanet et al., 2019). l-Val-ΔAla was shown to antagonize AHL-mediated induction of bioluminescence as well as inhibit the swarming mobility of Gram-negative bacterium Serratia liquefaciens (Holden et al., 1999), suggesting that l-Val-ΔAla may be involved in signal communications between different bacteria. In soil, a series of proline-derived DKPs produced by P. aeruginosa were found to mimic the effect of phytohormone auxin and affect root development in Arabidopsis thaliana, indicating DKPs play roles in transkingdom signaling (Ortiz-Castro et al., 2011).

The two DKPs identified in this study exhibited dose-dependent effects on P. tricornutum growth (Figure 4A). At a low concentration of 100 nM for cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) or 35 nM for cyclic- l-Val-ΔAla (2), the DKPs lose their growth-promoting effect. Half maximal effective concentrations EC50 for growth stimulation were shown to be 320 nM for cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) and 690 nM for cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2). When the DKP concentration exceeds 10 mM or 700 μM for cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) or cyclic- l-Val-ΔAla (2), respectively, growth inhibition was instead observed (Figure 4A). This result suggests that the two DKPs may be important regulatory factors instead of just being essential nutrients.

The absolute concentration of cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) and cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2) in the Bti lysate was quantified to be 10 and 4 µM for cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) and cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2), respectively (Figure 4 C and D), which are within the optimal range for growth promotion. Individual DKPs even at the optimal concentration range exhibit a longer lag time in promoting P. tricornutum growth than the bacterial lysate and cause P. tricornutum cells to reach plateau earlier than the bacterial lysate. The difference could be due to different microenvironments surrounding P. tricornutum that may affect DKP stability or effectiveness, or as a result of other growth-promoting compounds that remain to be identified from the B. thuringiensis lysate.

Given the ubiquitousness and abundance of the B. cereus group of bacteria, including their existence in sea water and marine sediments (Maeda et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2017), it is possible that diatoms may encounter the B. cereus group bacteria or bacterium-derived DKPs in the marine environment. Could bacterial-derived DKPs encourage diatom proliferation to increase dissolved organic carbon for their own use or indicate to diatoms the presence of certain bacteria competing for essential nutrients? Since there has been no report of direct association/interaction between Bacillus and diatoms in natural habitats, further investigations are necessary.

One of the main bottlenecks for algal-derived biofuels is algae cultivation and accumulation of enough biomass (Khan et al., 2018; Sajjadi et al., 2018). Most industrial cultivations of microalgae are in axenic photobioreactors or low-cost, open, nutrient-poor ponds. The slow growth rate of algae in nutrient-poor axenic medium, open pond, or aquatic conditions has limited its potential for sustainable biofuel production. Phaeodactylum tricornutum is a superb model organism for investigations that may lead to innovative solutions for these limitations. The available molecular genetic tools in P. tricornutum enable the genetic engineering of genes in the lipid biosynthesis pathway to increase lipid production (Daboussi et al., 2014; Serif et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). The results reported here provide another approach, the B. thuringiensis lysate can be inexpensively produced to stimulate P. tricornutum growth as well as increase neutral lipid production, leading to enhanced biomass accumulation without any observed negative impact on lipid content. Future work pairing our bacterial and chemical approaches with targeted genetic manipulation will allow for a greater understanding and improved benefit for biofuel production.

Methods

Equipment

UV spectra were acquired by using a Ultrospec 5300-pro UV/Visible spectrophotometer. Optical rotations were recorded on a JASCO P-2000 polarimeter (sodium light source) with a 1-cm cell. NMR spectra were recorded by a Bruker Avance 500 MHz spectrometer. ESI low-resolution LC/MS data were obtained by using an Agilent Technologies 6130 quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled with an Agilent Technologies 1200 series HPLC. HR-ESI mass spectra were acquired on an Agilent LC-q-TOF Mass Spectrometer 6530-equipped with a 1290 uHPLC system. HPLC purifications were performed by using Agilent 1100 or 1200 series LC systems equipped with a photo-diode array detector.

Bacillus strains and culture conditions

Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis was isolated from spores in the larvicide Gnatrol (Valent, Walnut Creek, CA, USA). Bacillus subtilis sp. 168 and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens were from Dr Wade Winkler at the University of Maryland, College Park. Bacillus cereus sp. 6A1, B. thuringiensis sp. 4A4, and B. thuringiensis sp. 4Q7 were purchased from the Bacillus Genetics Stock Center. Bacillus thuringiensis sp. 4D4 and B. thuringiensis sp. 407 were from Dr Vincent Lee. All Bacillus spp. were cultured in LB medium (5 g yeast extract, 10 g peptone, and 5 g sodium chloride in 1 L distilled water; Bertani, 1951). A single colony of Bacillus was added to 10 mL LB, which was grown at 37°C shaking at 200 r.p.m. overnight.

Phaeodactylum tricornutum strain, culture condition, and cell counts

Phaeodactylum tricornutum was cultured in the L1 medium (Guillard and Hargraves, 1993; https://ncma.bigelow.org/PML11L), a salt water solution containing 32 g/L of Instant Ocean sea salt supplemented with 1 mL (per liter salt water) trace metal solution (NCMA) as well as 8.82 × 10−4 M NaNO3, 3.62 × 10−5 M NaH2PO4·H2O, and 1.06 × 10−4 M Na2SiO3·9H2O.

Phaeodactylum tricornutum strain CCMP632 was obtained from NCMA (Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota, East Boothbay, ME). P. tricornutum cells were grown in nonshaking L1 medium at 22°C with a light intensity of 50 µmol/m2/s until mid-exponential phase, and 100 μL of such P. tricornutum culture was transferred to 2 mL L1 medium in 15-mL Falcon tubes with a tapered bottom. Overnight B. thuringiensis culture (100 µL), or control medium, or nutrients were, respectively, added into the same 2-mL culture. Co-cultures were grown without agitation at 22°C with a light intensity of 50 µmol/m2/s. P. tricornutum cells at any growth stage could be stimulated by adding the stimulating agents.

All cell counts of P. tricornutum were performed using a Hauser Scientific Levy Hemacytometer. An aliquot of 7.5 µL of cell culture was loaded into the well. Cells occupying the 1 mm × 1 mm × 0.1 µL grid were counted in the experiment. The cell counts were then scaled up to indicate “number of P. tricornutum cells per mL.”

Bacillus thuringiensis cell lysate production

To generate the B. thuringiensis mother cell lysate, 1.25 mL of B. thuringiensis overnight culture in LB medium was added to 25 mL of fresh L1 medium. The nutrient poor bacterial culture was kept at room temperature (RT) without shaking for 2 weeks to enable sporulation. The culture was spun down and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-µm filter to yield spore-free lysate. The spores in the pellet were washed 3 times in distilled water and resuspended in 1.25 mL of L1 medium; 100 µL was added to 2 mL of L1 medium for co-culture with 100 µL of P. tricornutum.

To generate mechanically lysed nonsporulating B. thuringiensis cells, 1.25 mL of B. thuringiensis was removed from a 25-mL overnight culture in LB, spun down, and resuspended in 350 µL of L1 medium. The cellular suspension was sonicated using the Microson Ultrasonic Cell Disruptor (Misonix) at setting 12 for 10 × 1-s pulses. The shredded cells were resuspended in 25 mL of L1 medium and filtered through a 0.22-µm filter. An aliquot (2 mL) of mechanically generated lysate was transferred into a 15-mL Falcon tube followed by the addition of 100 µL P. tricornutum culture at exponential phase.

Proteinase K treatment of mother cell lysate

To pre-treat the Bacillus mother cell lysate with Proteinase K, 2 μL of Proteinase K (20 mg/mL) was added to 2 mL Bacillus mother cell lysate, which was allowed to sit for 1 week at 22°C. Afterwards, 80 μL of water containing 4.1 mg of glycine was added to the Bacillus lysate to inhibit the Proteinase K. At this point, 100-μL P. tricornutum culture was added to the 2-mL lysate pretreated with Proteinase K.

Identification of DKP from B. thuringiensis israelensis lysate

The Bacillus thuringiensis strain was cultivated in 5 mL of LB medium in a 15-mL falcon tube. After cultivating the strain for 3 d on a rotary shaker at 180 r.p.m. at 30°C, 5 mL of the B. thuringiensis liquid culture was inoculated to 500 mL of L1 medium (1 mL NaNO3 [75.0 g/L dH2O], 1 mL NaH2PO4·H2O [5.0 g/L dH2O], 1 mL Na2SiO3·9H2O [30.0 g/L dH2O] in 1 L artificial seawater) in a 1-L Pyrex media storage bottle. To induce sporulation and generate B. thuringiensis mother-cell lysate, the B. thuringiensis was incubated at 22°C. The culture was allowed to sporulate for 21 d to generate the mother cell lysate. Supernatant from 8 L culture for the B. thuringiensis israelensis was loaded on a column containing 100 g of XAD4 and 100 g of XAD7 (Amberlite® XAD4 and XAD7, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). After loading the supernatant, the column was washed with 500 mL of DI water and then the crude extract was eluted with 500 mL of 100% MeOH (v/v). The MeOH was evaporated to yield a crude extract. The crude extract was then resuspended in ∼50 mL of 100% DI water (v/v) and loaded on a 10 g RP C18 SPE cartridge and fractionated using the following solvent system: 100% H2O (v/v; fraction A), 20% (v/v; fraction B), 40% (v/v; fraction C), 60% (v/v; fraction D), 80% (v/v; fraction D), and 100% (v/v; fraction E) MeOH/H2O. The growth simulation activity was only detected in fraction A—100% water fraction.

Fraction A (100% water fraction) was then subjected to reversed-phase prep-HPLC (Luna® Phenyl-Hexyl: 250 × 21.2 mm, 5 µm) with the following linear gradient elution: 5% acetonitrile (ACN)/95% H2O (v/v) to 20% ACN/80% H2O (v/v) over 40 min with a flow rate of 10 mL/min. Fractions were collected every 2 min between 5 and 55 min, generating 25 refined fractions. Growth stimulating activity was detected in fractions A13 (31 min) and A19 (43 min) yielding cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1- 2.5 mg) and cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2- 1.2 mg), respectively.

Cyclic -l-Pro-l-OMet (1). [α]D −125.8 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (4.12) nm; HR-ESI-MS m/z 245.0972 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C10H17N2O3S 245.0965); 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δH 4.53 (t, J = 5.0, 1Η), 4.36 (t, J = 8.0, 1Η), 3.57 (m, 2H), 2.97 (m, 2H), 2.74 (s, 3Η), 2.38–2.31 (m, 3H), 2.08 (m, 1H), 1.98–1.97 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O) δC 175.2, 168.9, 61.8, 56.5, 50.3, 48.1, 39.3, 30.5, 25.3, and 24.6.

Cyclic -l-Val-ΔAla (2). [α]D −113.2 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 220 (4.08) nm, 240 (3.96); HR-ESI-MS m/z 169.0981 [M + H]+ (calcd for C8H13N2O2 169.0983); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH 10.52 (brs, 1Η), 8.36 (s, 1Η), 5.17 (s, 1H), 4.77 (s, 1H), 3.83 (br, 1Η), 2.12 (m, 1H), 0.91 (d, J = 7.5, 3H), 0.81 (d, J = 7.5, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC 165.5, 158.7, 134.6, 98.9, 60.4, 33.2, 18.0, and 16.5.

Cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (A13) was dissolved in 50 μL of 30% MeOH/H2O (v/v) solution. Cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (A19) was solved in 70% MeOH/H2O (v/v) solution. An aliquot (10 μL) of each DKP solution was added to 1 mL of L1 media containing P. tricornutum cells. Cell counts were taken at Days 3 and 7. Three biological replicates were used for each cell count (Figure 3).

Marfey’s method for determination of absolute configurations of 1 and 2

One milligram of cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) and cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2) were hydrolyzed in 0.5 mL of 6 N HCl at 115°C. After 1 h, the reaction mixtures were cooled to RT by placing on ice water for 3 min. The reaction mixture was evaporated in vacuo then the material was resuspended in 0.5 mL H2O and dried under vacuum (×3) to ensure complete removal of the acid. The hydrolysate of each DKP was lyophilized overnight. Subsequently, the dried reaction material and 0.5 mg of each amino acids, including l-Pro, d-Pro, l-OMet, l/d-OMet, l-Val, and d-Val, were each dissolved in 100 μL of 1 N NaHCO3, followed by the addition of 50 μL of 10 mg/mL l-FDAA in acetone. The reaction mixture was incubated at 80°C for 3 min then quenched by the addition of 50 μL of 2 N HCl. Then 300 μL of 50% ACN/50% H2O (v/v) was added to each mixture and 10 μL was analyzed by LC-MS using a Kinetex® EVO C18 column (100 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) using the following gradient solvent system: gradient from 20% ACN + 0.1% FA (v/v)/80% H2O + 0.1% FA (v/v) to 60% ACN + 0.1.% FA (v/v)/40% H2O + 0.1% FA (v/v) over 40 min with a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min (UV detection at 340 nm). The retention times of authentic acid l-FDAA derivatives l-Pro (13.1 min), d-Pro (16.8 min), l-OMet (9.7 min), d-OMet (10.6 min), l-Val (20.7 min), and d-Val (24.2 min); the hydrolysate products gave peaks with retention times of 13.1, 9.8, and 20.7 min, according to l-Pro, l-Val, and l-OMet, respectively.

Total synthesis of cyclic- l-Pro-l-OMet (1)

Boc-l-methionine-sulfoxide (1,000 mg, 3.76 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (20 mL) followed by O-(Benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (1.713 mg, 4.52 mmol) and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at RT. Subsequently, l-Proline methyl ester (749 mg, 4.52 mmol) and triethylamine (0.63 mL, 4.52 mmol) were added, and the mixture was stirred for 18 h at 4°C in a cold room. After 18 h, the reaction mixture was quenched by adding water (10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (20 mL × 3). The organic layer was dried under vacuum to yield 580 mg of crude white oil (41% yield). The oil was then dissolved in 1 mL of anhydrous dioxane, heated to 50°C and 3 N hydrochloride (0.6 mL, ∼4 equiv.) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h and then worked up by evaporating the solvent under vacuum. The mixture was then lyophilized under high vacuum overnight. The final cyclization reaction was accomplished by resuspending the dried oil in anhydrous dimethylformamide (2 mL), which was then heated to 100°C and stirred for 4 h. The mixture was frozen and then dried by lyophilizing under high vacuum overnight. The resulting oil was purified by reversed-phase prep-HPLC using a LunaⓇ Phenyl-Hexyl column (250 × 21.2 mm, 5 µm) with the following solvent gradient system: 5% ACN/95% H2O (v/v) to 20% ACN/80% H2O (v/v) over 40 min with a flowrate of 10 mL/min. Cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) was obtained as white oil with an overall yield of 26.6% (250 mg).

Absolute quantifications of the two DKPs in different strains

Production levels of 1 and 2 produced by different B. thuringiensis strains—B. thuringiensis israelensis, B. thuringiensis sp. 4A4, B. thuringiensis sp. 4Q7, and B. thuringiensis sp. 407—were quantified using 1-L cultures of each strain. An aliquot of 5 mL of overnight LB cultures of each strain were used to inoculated 500 mL of L1 media. Cultures were grown at 22°C without shaking for 21 d. Then each supernatant was centrifuged (7,000 rcf, 30 min) and freeze-dried. The dried cell pellets were weighed in order to normalize production levels to total biomass. The spent supernatant of each extract was passed over a column containing 20 g of XAD4 and XAD7 resin mixture the crude extract was eluted with 40 mL of DI water and 40 mL of 100% MeOH (v/v). The dried crude extract was then resuspended in ∼20 mL of 100% DI water (v/v) and was loaded on Sep-pak C18 cartridge (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). The cartridge was washed with 20 mL of 100% H2O (v/v) and 20 mL of 25% MeOH/75% H2O (v/v) and dried to form one fraction per strain. The fractions were resuspended in 500 μL of 50% MeOH/50% H2O (v/v) and 10 μL was analyzed on the LC-MS equipped with a KinetexⓇ EVO C18 column (100 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) using the following gradient system: 5% ACN/95% H2O (v/v) to 60% ACN/40% H2O (v/v) over 20 min at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min. Integrated extracted ion chromatograms for ion adducts corresponding to 1 (m/z 244) and 2 (m/z 168) were analyzed and compared to a six-point standard curve generated by authentic standards.

Phaeodactylum tricornutum growth stimulation by DKP and mixed single amino acids

Cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1) was dissolved in 30% MeOH (v/v) in the water at a stock concentration of 100 mM. cyclic-l-Val-ΔAla (2) was dissolved in 70% MeOH (v/v) in the water at a stock concentration of 20 mM. Then 30% MeOH (v/v) and 70% MeOH (v/v) solutions were used in DKP-free control cultures, respectively. Final concentrations were obtained by diluting DKPs in the L1 media. Phaeodactylum tricornutum cells were cultured in 1 mL of L1 medium containing 10 mM, 2 mM, 1 mM, 100 μM, 10 μM, 1 Μm, and 100 nM final concentrations for 1. Then 700 μM, 350 μM, 35 μM, 3.5 μM, 350 nM, and 35 nM are final concentrations for 2, and DKP-free methanol, respectively. Counts were taken on Day 7. Solutions containing mixed pair of single l-amino acids (l-Pro/l-Met AA and l-Val/l-Ala AA) were added to L1 media. l-Pro/l-Met AA was added at concentrations of 10 mM, 1 mM, 100 μM, and 10 μM, l-Val/l-Ala AA were added at concentrations 700 μM, 350 μM, 35 μM, and 3.5 μM. Counts were taken on Day 8.

Fatty acid analysis and BODIPY staining

About 2.5 mL of mid-exponential P. tricornutum cells were added to 50 mL of L1 medium or 50 mL of L1 medium containing B. thuringiensis lysate (see earlier section on B. thuringiensis lysate production). After 7 d, cells were centrifuged at 8,000g for 6 min. After removing the supernantant, the cells were transferred to 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged again at 13,300g for 30 seconds, and the pellet was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C. To extract lipids, a mixture of 628 μL methanol, 251 μL chloroform, and 251 μL water was added to the pellet. This suspension was vortexed and held at –20°C for 90 min, with a further vortex at 30 and 60 min. Extracts were centrifuged at 8,000g for 5 min and the supernatant was transferred to a separate vial. An additional mixture of 286-μL methanol and 286-μL chloroform was added to the cell pellet. The sample was vortex mixed and held at –20°C for 30 min, centrifuged at 8,000g for 5 min, and the supernatant was added to the previously saved supernatant. Then 286 μL of water was added to the combined liquid extract to achieve phase separation. The aqueous methanol layer was removed from the chloroform. The chloroform was evaporated under a gentile stream of nitrogen, and lipids were derivatized by adding 200 μL of 3 N methanolic HCl to the dried chloroform layer and heating at 70°C for 1 h. After allowing the sample to cool to RT, 100 μL of hexanes were added and the sample vortex mixed. The upper hexane layer containing the methyl-esterified lipids was collected. An additional 100 μL of hexanes was added to the acid raffinate and vortex mixed. The upper hexane layer was again collected and combined with the first extract. Then 50-μg methyl heptadecanoate was added as an internal standard. All samples were analyzed using a Bruker 450-GC gas chromatograph equipped with a Varian VF-5ms (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) column coupled to a Bruker 300MS mass spectrometer (Bruker, Fremont, CA, USA) in full scan, electron ionization mode. The GC oven temperature was initially set at 150°C for 2 min, raised to 205°C at 10°C min−1, then raised to 230°C at 3°C min−1, and finally raised to 300°C and held for 3 min at 10°C min−1. Compounds were identified using the Varian MS workstation software (version 6.9.3) in conjunction with the NIST mass spectral library (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Ion intensities were quantified using the sum of the total ion chromatograph peak area. The signal intensity of each compound within a sample was first normalized to the intensity of the internal standard, and then normalized to the total cell number in each sample.

For BODIPY 505/515 (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) staining of lipids, P. tricornutum was grown in L1 medium, L1 + B. thuringiensis lysate, or L1 + 100 μM cyclic-l-Pro-l-OMet (1). One milliliter of each culture was harvested at 12 d (stationary phase) and placed in a microcentrifuge tube. One microliter of 10 mM BODIPY (dissolved in DMSO) was added to each tube, which was left in the dark for 10 min. Afterward, P. tricornutum cells were washed twice with fresh L1 medium (pelleted at 11,000g for 10 min.) and then imaged with a Leica SP5X confocal microscope. The confocal images were analyzed using ImageJ-Fiji (https://imagej.net/Fiji). To quantify fluorescence, acceptable fluorescence intensity threshold was set between 50 and 225. A low threshold of 50 removes background fluorescence, whereas the high threshold of 225 excludes potentially oversaturated pixels. Individual cells were circled; Integrated Density (Mean Fluorescence Intensity × Area of Fluorescence with readings between 50 and 225) was obtained for the circled cell and plotted in Figure 5C. Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and fluorescent images of individual P. tricornutum cells shown in Figure 5B were obtained at 250× magnification using a Zeiss Axioscope with a Sony Alpha 7mrII camera (2.5×).

Supplemental data

The following supplemental materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. The B. thuringiensis-derived agent is resistant to Proteinase K (PROK).

Supplemental Figure S2. 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz) of cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1) in D2O.

Supplemental Figure S3. 13C NMR spectrum (125MHz) of cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1) in D2O.

Supplemental Figure S4. COSY spectrum (500 MHz) of cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1) in D2O.

Supplemental Figure S5. HSQC spectrum (500 MHz) of cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1) in D2O.

Supplemental Figure S6. HMBC spectrum (500 MHz) of cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1) in D2O.

Supplemental Figure S7. 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz) of cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S8. 13C NMR spectrum (125MHz) of cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S9. COSY spectrum (500 MHz) of cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S10. HSQC spectrum (500 MHz) of cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S11. HMBC spectrum (500 MHz) of cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S12. Comparison of retention time between cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1) and synthetic cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1) in LC–MS chromatogram.

Supplemental Figure S13. Comparison of retention time between cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) and synthetic cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) in LC–MS chromatogram.

Supplemental Figure S14. 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz) of synthetic cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S15. 13C NMR spectrum (125MHz) of synthetic cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (2) in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Figure S16 . 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz) of synthetic cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1)in D2O.

Supplemental Figure S17 . 13C NMR spectrum (125MHz) of synthetic cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet (1) in D2O.

Supplemental Table S1. 1H and 13C NMR data of 1 in D2O.

Supplemental Table S2. 1H and 13C NMR data of 2 in DMSO-d6.

Supplemental Table S3. LC/MS analysis of the FDAA derivatives of cyclic-L-Pro-L-OMet and cyclic-L-Val-ΔAla (1 and 2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for advice, bacterial strains, microscopy, equipment provided by Drs. Charles Delwiche, Eric Haag, Jonathan Goodson, Lei Guo, Cordelia Weiss, Caren Chang, Wade Winkler, Vince Lee, and Steven Farber. We would like to thank the dedicated assistance by undergraduates Ms. Caroline Gonter, Marta Roman, and Lina Sobh.

J.S., M.B., E.M., and A.Q. performed the experiments. M.L. performed data analyses. J.S., M.B., E.M., and Z.L. wrote the manuscript. J.C., G.S., and Z.L. guided the study. Z.L. agrees to serve as the author responsible for contact and ensures communication. All authors read, revised, and approved the manuscript.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instruction for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Zhongchi Liu (zliu@umd.edu).

Funding

This work has been supported by a grant from NSF/CBET 1134115 to G. S. and Z. L. as well as the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project 1010278 to Z. L. and J. S. was supported by the Wayne T. and Mary T. Hockmeyer Endowed Fellowship. M. L. was supported in part by NSF award DGE-1632976.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Amin SA, Parker MS,, Armbrust EV (2012) Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76: 667–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf A, Bano A, Ali SA (2019) Characterisation of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria from rhizosphere soil of heat-stressed and unstressed wheat and their use as bio-inoculant. Plant Biol 21: 762–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertani G (1951) Studies on lysogenesis I. J Bacteriol 62: 293–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthwick AD (2012) 2,5-Diketopiperazines: synthesis, reactions, medicinal chemistry, and bioactive natural products. Chem Rev 112: 3641–3716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, Allen AE, Badger JH, Grimwood J, Jabbari K, Kuo A, Maheswari U, Martens C, Maumus F, Otillar RP, et al. (2008) The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature 456: 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd PW, Ellwood MJ (2010) The biogeochemical cycle of iron in the ocean. Nat Geosci 3: 675–682 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Blackwell HE (2009) Efficient construction of diketopiperazine macroarrays through a cyclative-cleavage strategy and their evaluation as luminescence inhibitors in the bacterial symbiont vibrio fischeri. J Comb Chem 11: 1094–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft MT, Lawrence AD, Raux-Deery E, Warren MJ, Smith AG (2005) Algae acquire vitamin B12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Nature 438: 90–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daboussi F, Leduc S, Maréchal A, Dubois G, Guyot V, Perez-Michaut C, Amato A, Falciatore A, Juillerat A, Beurdeley M, et al. (2014) Genome engineering empowers the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum for biotechnology. Nat Commun 5: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster RA, Kuypers MMM, Vagner T, Paerl RW, Musat N, Zehr JP (2011) Nitrogen fixation and transfer in open ocean diatom–cyanobacterial symbioses. ISME J 5: 1484–1493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giessen TW, Marahiel MA (2015) Rational and combinatorial tailoring of bioactive cyclic dipeptides. Front Microbiol 6: 785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillard J, Frenkel J, Devos V, Sabbe K, Paul C, Rempt M, Inzé D, Pohnert G, Vuylsteke M, Vyverman W (2013) Metabolomics enables the structure elucidation of a diatom sex pheromone. Angew Chem Int Ed 52: 854–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillard RRL, Hargraves PE (1993) Stichochrysis immobilis is a diatom, not a chrysophyte. Phycologia 32: 234–236 [Google Scholar]

- Guinebretière MH, Thompson FL, Sorokin A, Normand P, Dawyndt P, Ehling‐Schulz M, Svensson B, Sanchis V, Nguyen‐The C, Heyndrickx M, et al. (2008) Ecological diversification in the Bacillus cereus group. Environ Microbiol 10: 851–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harizani M, Katsini E, Georgantea P, Roussis V, Ioannou E (2020) New chlorinated 2,5-diketopiperazines from marine-derived bacteria isolated from sediments of the Eastern Mediterranean sea. Molecules 25: 1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D, Dworkin J (2012) Recent progress in Bacillus subtilis sporulation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36: 131–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand M, Davis AK, Smith SR, Traller JC, Abbriano R (2012) The place of diatoms in the biofuels industry. Biofuels 3: 221–240 [Google Scholar]

- Holden MTG, Chhabra SR, Nys RD, Stead P, Bainton NJ, Hill PJ, Manefield M, Kumar N, Labatte M, England D, et al. (1999) Quorum-sensing cross talk: isolation and chemical characterization of cyclic dipeptides from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol 33: 1254–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Sommerfeld M, Jarvis E, Ghirardi M, Posewitz M, Seibert M, Darzins A (2008) Microalgal triacylglycerols as feedstocks for biofuel production: perspectives and advances. Plant J 54: 621–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang RM, Yi XX, Zhou Y, Su X, Peng Y, Gao CH (2014) An update on 2,5-diketopiperazines from marine organisms. Mar Drugs 12: 6213–6235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen GB, Hansen BM, Eilenberg J, Mahillon J (2003) The hidden lifestyles of Bacillus cereus and relatives. Environ Microbiol 5: 631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Gao K (2004) Effects of lowering temperature during culture on the production of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum (bacillariophyceae)1. J Phycol 40: 651–654 [Google Scholar]

- Khan MI, Shin JH, Kim JD (2018) The promising future of microalgae: current status, challenges, and optimization of a sustainable and renewable industry for biofuels, feed, and other products. Microb Cell Fact 17: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Lai Q, Du J, Shao Z (2017) Genetic diversity and population structure of the Bacillus cereus group bacteria from diverse marine environments. Sci Rep 7: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda M, Mizuki E, Nakamura Y, Hatano T, Ohba M (2000) Recovery of Bacillus thuringiensis from marine sediments of Japan. Curr Microbiol 40: 418–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Castro R, Díaz-Pérez C, Martínez-Trujillo M, del Río RE, Campos-García J, López-Bucio J (2011) Transkingdom signaling based on bacterial cyclodipeptides with auxin activity in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 7253–7258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raddadi N, Cherif A, Boudabous A, Daffonchio D (2008) Screening of plant growth promoting traits of Bacillus thuringiensis. Ann Microbiol 58: 47–52 [Google Scholar]

- Sajjadi B, Chen WY, Raman AAA, Ibrahim S (2018) Microalgae lipid and biomass for biofuel production: a comprehensive review on lipid enhancement strategies and their effects on fatty acid composition. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 97: 200–232 [Google Scholar]

- Schnepf E, Crickmore N, Rie JV, Lereclus D, Baum J, Feitelson J, Zeigler DR, Dean DH (1998) Bacillus thuringiensis and Its Pesticidal Crystal Proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62: 775–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev E, Wyche TP, Kim KH, Petersen J, Ellebrandt C, Vlamakis H, Barteneva N, Paulson JN, Chai L, Clardy J, et al. (2016) Dynamic metabolic exchange governs a marine algal-bacterial interaction. eLife 5: e17473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serif M, Dubois G, Finoux AL, Teste MA, Jallet D, Daboussi F (2018) One-step generation of multiple gene knock-outs in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum by DNA-free genome editing. Nat Commun 9: 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyedsayamdost MR, Case RJ, Kolter R, Clardy J (2011) The Jekyll-and-Hyde chemistry of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. Nat Chem 3: 331–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szókán G, Mezö G, Hudecz F (1988) Application of marfey’s reagent in racemization studies of amino acids and peptides. J Chromatogr A 444: 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanet L, Tamburini C, Baumas C, Garel M, Simon G, Casalot L (2019) Bacterial bioluminescence: light emission in photobacterium phosphoreum is not under quorum-sensing control. Front Microbiol 10: 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Dong HP, Wei W, Balamurugan S, Yang WD, Liu JS, Li HY (2018) Dual expression of plastidial GPAT1 and LPAT1 regulates triacylglycerol production and the fatty acid profile in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Biotechnol Biofuels 11: 318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Zhang B, Huang A, Huan L, He L, Lin A, Niu J, Wang G (2014) Detection of intracellular neutral lipid content in the marine microalgae Prorocentrum micans and Phaeodactylum tricornutum using Nile red and BODIPY 505/515. J Appl Phycol 26: 1659–1668 [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Chen X, Jiang M, Li X (2020) Two marine natural products, penicillide and verrucarin J, are identified from a chemical genetic screen for neutral lipid accumulation effectors in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104: 2731–2743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulu NN, Zienkiewicz K, Vollheyde K, Feussner I (2018) Current trends to comprehend lipid metabolism in diatoms. Prog Lipid Res 70: 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.