Abstract

Purpose

We report the case of a 33-year-old male who presented with unilateral central serous retinopathy three days after the injection of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Observations

A 33-year-old healthy Hispanic male referred to the ophthalmology service due to blurry vision and metamorphopsia in the right eye without any flashes, floaters, eye redness or pain. The patient reported that 69 hours prior to presentation he received the first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. He denied any past ocular history or pertinent medical history. He does not take any medicines and denies stressful factors in his life. The clinical examination and imaging tests were consistent with central serous retinopathy that resolved in three months.

Conclusions and importance

This is the first report of an ocular complication potentially associated with a COVID-19 vaccination. Our case contributes information of a side effect potentially related to this new vaccine.

Keywords: COVID-19, mRNA vaccine, CSR, Central serous retinopathy

1. Introduction

Since the first report of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in China in December 2019, COVID-19 has been responsible for more than three million deaths worldwide. The ongoing outbreak of COVID-19 has been declared by the World Health Organization as a public health emergency and a vaccine to control the situation was anxiously expected. Vaccine development occurred in less than one year and thus, long-term data on side effects are still developing.

The most common ocular manifestation of COVID-19 is hyperemia or conjunctival “congestion.“1,2 In addition, reports of central retinal vein occlusion,3 toxic shock syndrome4 and hemorrhages with microinfarcts have been described in COVID-19 patients.5 To the best of our knowledge, no intraocular side effects have been reported from any of the COVID-19 vaccinations (a case of Bell's Palsy was described in a patient who received the Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccine).6

We present a unique case of a healthy Hispanic male who presented with unilateral central serous retinopathy (CSR), temporally related to the administration of a COVID-19 vaccine.

2. Case report

A 33-year-old healthy Hispanic male was referred for ophthalmological evaluation due to blurry vision and metamorphopsia in his right eye. He denied flashes, floaters, ocular pain or redness. He did not have any visual symptoms in his left eye.

Past ocular history was negative except for mild hyperopic refractive error. Past medical history was only significant for hip surgery post traumatic injury six years prior to presentation. He denied use of any medications including any remote history of corticosteroids. 69 hours before presentation he received the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, after which, he reported soreness at the injection site and fatigue for 24 hours. Since the inception of the pandemic, the patient has experienced no COVID-19 symptoms and had a negative PCR result in November 2020.

On exam, his best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/63 and 20/25 in his right and left eye, respectively. Pupils were equally round and reactive to light and accommodation. Intraocular pressure was 10 mmHg in both eyes.

Anterior segment exam was within normal limits. Dilated fundus examination was normal in the left eye but revealed loss of foveal reflex and swollen appearance of the macula in the right eye. No hemorrhages or vascular abnormalities were noted (Fig. 1A).

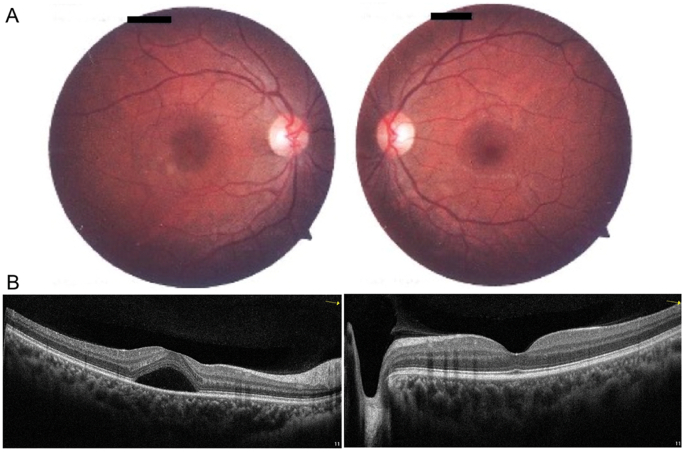

Fig. 1.

Clinical evaluation of a patient with unilateral central serous retinopathy. Right eye (left column) and left eye (right column) are shown. Fundus photography of the posterior pole (A) of the right eye shows an inferotemporal parafoveal depigmented lesion. The left eye fundus was normal. Optical coherence tomography (B) of the right eye shows a serous detachment of the neurosensory retina in the central macula.

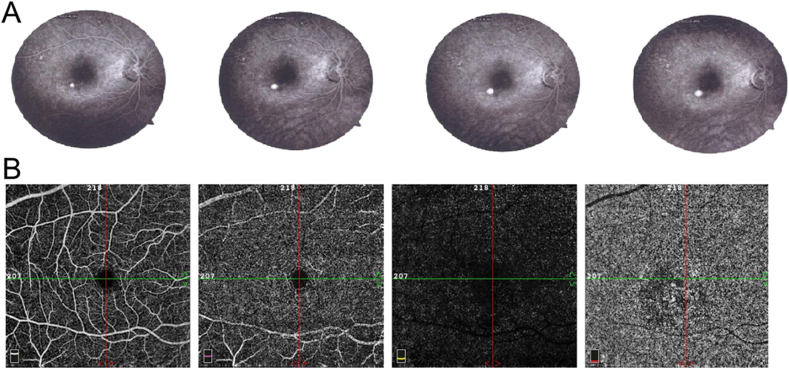

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the right eye showed a macular serous detachment of the neurosensory retina (Fig. 1B) with a central foveal thickness (CFT) of 457 μm. OCT of the left eye was unremarkable. On fluorescein angiography (FA), a single point of leakage was noted following the classical ink-blot pattern, with progressive expansion of hyperfluorescence emanating from a single point (Fig. 2A). Consistent with previous reports of CSR,7, 8, 9 OCT angiography (OCTA) showed generally attenuated flow signal in the choriocapillaris that colocalized to the area of serous retinal detachment and foci of increased flow signal (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Vascular examinations of the effected eye of a patient with unilateral central serous retinopathy. (A) Fluorescein angiography from early (left) to late (right) angiogram phases show the classic expansile dot just inferotemporal to the fovea. Optical coherence tomography angiography (B) of the right eye is unremarkable in the superficial (left) and deep (second from left) capillary plexuses and avascular segments (second from right) but shows generally attenuated flow signal that colocalized to the area of serous retinal detachment and foci of increased flow signal at the level of the choriocapillaris (right).

After the initial evaluation, the patient was prescribed spironolactone 50mg daily and was evaluated two and three months later. At the two-month visit, BCVA improved to 20/40 and CFT decreased to 325 μm. At the three-month visit, BCVA improved to 20/20, CFT decreased to 211 μm, OCT showed complete resolution of subretinal fluid, and the patient was asymptomatic.

3. Discussion

We present a case of acute unilateral CSR that developed shortly after immunization with the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of an intraocular complication associated with COVID-19 vaccination.

We believe it is prudent to consider the immunization as a potential contributor to disease, given 1) the temporal association between immunization and symptom onset, 2) the relatively low incidence of CSR (9.9 per 100,000 individuals)10 and 3) our case's absence of classical risk factors for CSR development (including a history of exogenous steroid use, recent stressful social history, and type-A personality).11 While no cases of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine associated CSR have been reported to date, CSR has been associated with vaccinations against influenza, yellow fever, anthrax and smallpox.12, 13, 14, 15 Still, these cases are rare. In fact, a search of the terms “central serous”, “central serous retinopathy”, “central serous chorioretinopathy” and “CSR” across all vaccine products by all vaccine manufacturers yielded no results from 1990 to date using the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. Nevertheless, vaccines have also been associated with a host of chorioretinal pathologies beyond CSR. For example, vaccinations against influenza, yellow fever, hepatitis B, and Neisseria meningitidis have been associated with uveitis, acute idiopathic maculopathy, acute macular neuroretinopathy, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, and multiple evanescent white dot syndrome.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

The pathophysiology of CSR remains incompletely understood, but the current literature emphasizes the role of a hyperpermeable and thickened choroid, as a result of hydrostatic forces, ischemia, or inflammation.11 Further evidence suggests endogenous and exogenous glucocorticoids contribute to the development of the choroidal vasculopathy.24 The role of retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction remains uncertain. Furthermore, CSR's difficult to explain associations with additional risk factors—systemic hypertension,25 alcohol use,25 gastroesophageal reflux disease,26 and sympathomimetic agents27—offer additional questions about the pathophysiology of disease.

There are several possible pathophysiologic mechanisms for the mRNA vaccine to cause CSR. Our hypotheses for possible pathophysiologic mechanisms are divided into three arms, related to increased serum cortisol, free extracellular mRNA, and polyethlene glycol. First, there is an association between CSR and high serum cortisol levels.28 The authors could not find any data related to serum cortisol levels after mRNA immunizations. However in one study of a tetanus toxoid vaccination, serum cortisol levels increased acutely nearly two-fold after vaccination.29 Therefore, it seems reasonable that mRNA immunizations may similarly trigger endogenous glucocorticoid release. On the other hand, studies have consistently demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines inhibit glucocorticoid receptor expression through decreased receptor translocation and binding affinity.30 Vaccines, including the extensively studied influenza virus vaccine, induce mild inflammatory responses.31, 32, 33 Another study showed that pain at injection site and increased body temperature were accompanied by a pro-inflammatory cytokine response.34

Other potential etiologies may arise from the presence of extracellular RNA. Extracellular naked RNA has been shown to increase the permeability of endothelial cells and may thus contribute to leaky choriocapillaris.35 Alternatively, extracellular naked RNA has been shown to promote blood coagulation and thrombus formation.36 Studies of CSR have highlighted that retinal areas with mid-phase inner choroidal staining also have delayed choroidal filling, suggesting choroidal lobular ischemia with associated areas of venous dilation.37,38 Interestingly, this phenomenon may explain the attenuated flow signal in the choriocapillaris on OCTA in cases of CSR, including our case.7, 8, 9 Further, elevated serum plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, a fibrinolytic, in CSR have led to the suggestion of a thrombotic mechanism for these vascular changes.39

Finally, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-2000 is a lipid ingredient in the vaccine formulation meant to enable the delivery of RNA into host cells. PEGs are the most commonly used hydrophilic polymers used in drug delivery tasked to control pharmacokinetic properties and deliver drug to specific sites. Anaphylactic reactions have been reported in relation to PEG compounds, that are used in bowel preparation regimens and prescription medications (e.g. methylprednisolone acetate).40 In addition, subretinal PEG-8 induces choroidal neovascularization and choroidal vessel thickening through activation of the complement pathway in murine models.41,42

4. Conclusions

Acute CSR may be temporally associated with mRNA Covid-19 immunization.

Patient consent

Informed consent was obtained on this patient at the Instituto “La Raza,” Mexico City, Mexico.

Acknowledgements and Disclosures

The authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Abrishami M., Tohidinezhad F., Daneshvar R. Ocular manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Northeast of Iran. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28(5):739–744. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1773868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L., Deng C., Chen X. Ocular manifestations and clinical characteristics of 535 cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98(8):e951–e959. doi: 10.1111/aos.14472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yahalomi T., Pikkel J., Arnon R., Pessach Y. Central retinal vein occlusion in a young healthy COVID-19 patient: a case report. Am J Ophthalmol Case Reports. 2020;20:100992. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng Y., Armenti S.T., Albin O.R., Mian S.I. Novel case of an adult with toxic shock syndrome following COVID-19 infection. Am J Ophthalmol Case Reports. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lani-Louzada R., Ramos C do V.F., Cordeiro R.M., Sadun A.A. Retinal changes in COVID-19 hospitalized cases. PLoS One. 2020;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2035389. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matet A., Daruich A., Hardy S., Behar-Cohen F. Patterns OF choriocapillaris flow signal voids IN central serous chorioretinopathy: an optical coherence tomography angiography study. Retina. 2019;39(11):2178–2188. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costanzo E., Cohen S.Y., Miere A. Optical coherence tomography angiography in central serous chorioretinopathy. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:134783. doi: 10.1155/2015/134783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cakir B., Reich M., Lang S. OCT angiography of the choriocapillaris in central serous chorioretinopathy: a quantitative subgroup Analysis. Ophthalmol Ther. 2019;8(1):75–86. doi: 10.1007/s40123-018-0159-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitzmann A.S., Pulido J.S., Diehl N.N., Hodge D.O., Burke J.P. The incidence of central serous chorioretinopathy in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980–2002. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholson B., Noble J., Forooghian F., Meyerle C. Central serous chorioretinopathy: update on pathophysiology and treatment. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(2):103–126. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ROSEN E. The significance of ocular complications following vaccination. Br J Ophthalmol. 1949;33(6):358–368. doi: 10.1136/bjo.33.6.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster B.S., Agahigian D.D. Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with anthrax vaccination. Retina. 2004;24(4) doi: 10.1097/00006982-200408000-00023. https://journals.lww.com/retinajournal/Fulltext/2004/08000/CENTRAL_SEROUS_CHORIORETINOPATHY_ASSOCIATED_WITH.23.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palacios A.I., Rodríguez M., Martín M.D. Central serous chorioretinopathy of unusual etiology: a report of 2 cases. Arch la Soc Española Oftalmol (English Ed. 2014;89(7):275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereima R.R., Bonatti R., Crotti F. Ocular Adverse events following yellow fever vaccination: a case series. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. April 7, 2021:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1887279. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marinho P.M., Nascimento H., Romano A., Muccioli C., Belfort R. Diffuse uveitis and chorioretinal changes after yellow fever vaccination: a re-emerging epidemic. Int J Retin Vitr. 2019;5(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s40942-019-0180-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng C.C., Jumper J.M., Cunningham E.T.J. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome following influenza immunization - a multimodal imaging study. Am J Ophthalmol case reports. 2020;19:100845. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorge L.F., Queiroz R. de P., Gasparin F., Vasconcelos-Santos D.V. Presumed unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy following H1N1 vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1734213. Published online March 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parth S S.Z.J., Hl J. Acute macular neuroretinopathy following the administration of an influenza vaccination. Ophthalmic Surgery, Lasers Imaging Retin. 2018;49(10):e165–e168. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20181002-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sood A.B., O'Keefe G., Bui D., Jain N. Vogt-koyanagi-harada disease associated with hepatitis B vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27(4):524–527. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2018.1483520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abou-Samra A., Tarabishy A.B. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome following intradermal influenza vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27(4):528–530. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1423334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biancardi A.L., de Moraes H.V. Anterior and intermediate uveitis following yellow fever vaccination with fractional dose: case reports. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;27(4):521–523. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2018.1510529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moysidis S.N., Koulisis N., Patel V.R. The second blind spot: small retinal vessel vasculopathy after vaccination against Neisseriameningitidis and yellow fever. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2017;11 doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000391. https://journals.lww.com/retinalcases/Fulltext/2017/01111/THE_SECOND_BLIND_SPOT__SMALL_RETINAL_VESSEL.6.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholson B.P., Atchison E., Idris A.A., Bakri S.J. Central serous chorioretinopathy and glucocorticoids: an update on evidence for association. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haimovici R., Koh S., Gagnon D.R., Lehrfeld T., Wellik S. Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: a case–control study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(2):244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mansuetta C.C., Mason J.O., Swanner J. An association between central serous chorioretinopathy and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(6):1096–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michael J.C., Pak J., Pulido J., de Venecia G. Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with administration of sympathomimetic agents. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(1):182–185. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00076-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zakir S.M., Shukla M., Simi Z.U.R., Ahmad J., Sajid M. Serum cortisol and testosterone levels in idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57(6):419–422. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.57143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oken E., Kasper D.L., Gleason R.E., Adler G.K. Tetanus toxoid stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal Axis correlates inversely with the increase in tetanus toxoid antibody Titers1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(5):1691–1696. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pace T.W.W., Miller A.H. Cytokines and glucocorticoid receptor signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179(1):86–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaser R., Robles T.F., Sheridan J., Malarkey W.B., Kiecolt-Glaser J.K. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2003;60(10):1009–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christian L.M., Porter K., Karlsson E., Schultz-Cherry S., Iams J.D. Serum proinflammatory cytokine responses to influenza virus vaccine among women during pregnancy versus non-pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70(1):45–53. doi: 10.1111/aji.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christian L.M., Iams J.D., Porter K., Glaser R. Inflammatory responses to trivalent influenza virus vaccine among pregnant women. Vaccine. 2011;29(48):8982–8987. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christian L.M., Porter K., Karlsson E., Schultz-Cherry S. Proinflammatory cytokine responses correspond with subjective side effects after influenza virus vaccination. Vaccine. 2015;33(29):3360–3366. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer S., Gerriets T., Wessels C. Extracellular RNA mediates endothelial-cell permeability via vascular endothelial growth factor. Blood. 2007;110(7):2457–2465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-040691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kannemeier C., Shibamiya A., Nakazawa F. Extracellular RNA constitutes a natural procoagulant cofactor in blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(15):6388–6393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608647104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prünte C., Flammer J. Choroidal capillary and venous congestion in central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(1):26–34. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)70531-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spaide R.F., Hall L., Haas A. ICG videoangiography of older patients with CSCR. Retina. 1996;16:201–213. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iijima H., Iida T., Murayama K., Imai M., Gohdo T. Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 in central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127(4):477–478. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(98)00378-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone C.A., Liu Y., Relling M.V. Immediate hypersensitivity to polyethylene glycols and polysorbates: more common than we have recognized. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(5):1533–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.12.003. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandez-Bueno I., Alonso-Alonso M.L., Garcia-Gutierrez M.T., Diebold Y. Reliability and reproducibility of a rodent model of choroidal neovascularization based on the subretinal injection of polyethylene glycol. Mol Vis. 2019;25(August 2018):194–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lyzogubov V.V., Tytarenko R.G., Liu J., Bora N.S., Bora P.S. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-induced mouse model of choroidal neovascularization. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(18):16229–16237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]