Abstract

Introduction: Little is known about the experiences and concerns of patients recently diagnosed with thyroid cancer or an indeterminate thyroid nodule. This study sought to explore patients' reactions to diagnosis with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) or indeterminate cytology on fine needle aspiration.

Methods: We conducted semistructured interviews with 85 patients with recently diagnosed PTC or an indeterminate thyroid nodule before undergoing thyroidectomy. We included adults with nodules ≥1 cm and Bethesda III, IV, V, and VI cytology. The analysis utilized grounded theory methodology to create a conceptual model of patient reactions.

Results: After diagnosis, participants experienced shock, anxiety, fear, and a strong need to “get it out” because “it's cancer!” This response was frequently followed by a sense of urgency to “get it done,” which made waiting for surgery difficult. These reactions occurred regardless of whether participants had confirmed PTC or indeterminate cytology. Participants described the wait between diagnosis and surgery as difficult, because the cancer or nodule was “still sitting there” and “could be spreading.” Participants often viewed surgery and getting the cancer out as a “fix” that would resolve their fears and worries, returning them to normalcy. The need to “get it out” also led some participants to minimize the risk of complications or adverse outcomes. Education about the slow-growing nature of PTC reassured some, but not all patients.

Conclusions: After diagnosis with PTC or an indeterminate thyroid nodule, many patients have strong emotional reactions and an impulse to “get it out” elicited by the word “cancer.” This reaction can persist even after receiving education about the excellent prognosis. Understanding patients' response to diagnosis is critical, because their emotional reactions likely pose a barrier to implementing guidelines recommending less extensive management for PTC.

Keywords: thyroid cancer, thyroid nodule, indeterminate nodule, cancer fear, anxiety, qualitative, active surveillance

Introduction

Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is the most common thyroid malignancy (1). Unlike those with many other malignancies, patients with localized PTC have excellent long-term survival—99.9% at 10 years (2). Patients at low risk for recurrence also have an excellent prognosis regardless of the extent of thyroidectomy (3,4). The American Thyroid Association (ATA) updated guidelines for managing these patients in 2015 (1,5). In addition to total thyroidectomy, patients with low-risk PTC measuring 1–4 cm have the option of thyroid lobectomy if there is no reason to remove the contralateral lobe. This less extensive option decreases the risk for complications and has the potential to improve quality of life (6–12).

Changes to the ATA guidelines for patients with PTC has led to an increased need for shared decision making and individualizing treatment plans (13). However, little is known about patients' experiences and concerns before undergoing treatment, particularly with respect to the impact of their diagnosis. Research to date has largely focused on survivors of thyroid cancer who often have a decreased quality of life and other psychosocial stress, despite their excellent prognosis (14–28). Data suggest that the long-term psychological well-being of cancer survivors is associated with their emotional response to diagnosis (29). Therefore, data are needed to better understand patients' responses to diagnosis with PTC.

Clinical experience suggests that patients diagnosed with an indeterminate thyroid nodule have similar experiences to those with PTC, especially with respect to treatment options and the need for shared decision making. Up to 30% of cytology results are indeterminate (Bethesda III or IV) or suspicious for PTC (Bethesda V) (30). The uncertainty about malignancy combined with the wide range of cancer risk likely impacts patients' experiences (31). However, a few studies have examined patients with indeterminate cytology at the time of diagnosis.

Given the paucity of data in this area, this study included patients with PTC and those with indeterminate cytology. The aim of this study was to better understand patients' experiences surrounding diagnosis with thyroid cancer or an indeterminate nodule. This information is necessary for understanding and supporting complex treatment decision making and for developing strategies to implement guideline changes recommending less extensive treatment.

Materials and Methods

Study population

To better understand patients' experiences surrounding diagnosis with PTC or an indeterminate nodule, we recruited adults 18 years of age or older diagnosed with a 1 cm or larger thyroid nodule and cytology of PTC (Bethesda VI), suspicious for PTC (Bethesda V), or indeterminate result (Bethesda III or IV) considered highly suspicious for cancer by the treating provider due to ultrasound appearance or other clinical history. Participation was part of an ongoing prospective randomized clinical trial (NCT02138214) conducted at a tertiary care center in the United States. The primary aim of the trial was to assess surgical outcomes of total thyroidectomy with or without prophylactic central neck dissection. This study was part of a planned secondary aim that examined patient experiences and quality of life after thyroid lobectomy, total thyroidectomy, and total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection. Patients with cervical lymph node metastases present preoperatively or discovered intraoperatively were excluded.

Participant recruitment

Research staff identified eligible participants by screening the electronic health record. Eligibility was confirmed by the treating surgeon (n = 11) or advanced practice provider (n = 1) who introduced the study to patients in person during the initial consultation. The conversations between the surgeon and patient in the clinic reflected real-life conditions and were not standardized. However, all visits consistently included a discussion of the diagnosis, prognosis, appropriate treatment alternatives, risks of treatment, and long-term outcomes. All patients were provided with educational materials, including a handout and booklet that reviewed thyroid pathology including nodules and thyroid cancer, indications for surgery, risks of surgery, and convalescence. All patients were aware of their diagnosis before their visit to the surgeon. Research staff obtained written consent from eligible patients in person after their surgical consultation, and interviews occurred at least 1 week later at a time convenient for the patient, with a mean of 23.8 ± 19.3 days. Because participation in this study was part of an ongoing prospective randomized trial powered for surgical outcomes, interviews were not performed with the goal of achieving thematic saturation. This study includes the number of patients enrolled at the time of analysis and was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (No. 2014-0391).

Data collection

Trained nonclinical interviewers (n = 15) conducted semistructured interviews between August 2014 and February 2019 at the subjects' convenience in a private room, such as a conference room or office, in or adjacent to the hospital. Interviewers followed a semistructured interview guide developed from pilot interviews, with eight patients at various stages in the diagnostic–treatment process. Pilot interviews were not included in data analysis. Interviews included both prompted and unprompted questions. Interviewers were trained to strategically deviate from the guide to probe on topics most relevant to the study aims.

Participants were questioned about (a) their experience with diagnosis, (b) interaction with their surgeon, (c) advice they would give the surgeon after the initial consultation, (d) advice they would give to a newly diagnosed patient, and (e) the effectiveness of communication with their care team. Throughout the interview process, interview guides were iteratively modified by the study's principal investigators (R.S.S. and N.P.C.) to best fit the study aims. Participants were encouraged to share any information or experiences they felt were relevant to their thyroid cancer experience and were explicitly given permission to not answer any questions that made them uncomfortable. Once completed, audio recordings from the interviews were transcribed verbatim and all identifiers were removed from transcripts before coding.

Qualitative analysis

Study principle investigators (R.S.S. and N.P.C.) and qualitative research experts (C.L.M. and J.O.) conducted line-by-line coding of the pilot interview transcripts (n = 8) to define emergent themes and develop a coding structure by using a grounded theory approach (32). Initial analyses of the themes were compared among researchers, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. From this process, a catalogue of focused codes was developed and a group of trained coders applied the coding scheme to the entire data set by using NVivo 11 (QSR International) software. Emerging themes were continuously integrated into the code book by using a constant comparative method at bi-weekly coding meetings. A descriptive matrix analysis was performed to systematically identify any differences in the responses of subjects based on their cytologic diagnosis. Matrices facilitate simultaneous and systematic identification of similarities, differences, and trends in responses across groups in qualitative research (33).

Conceptual model development

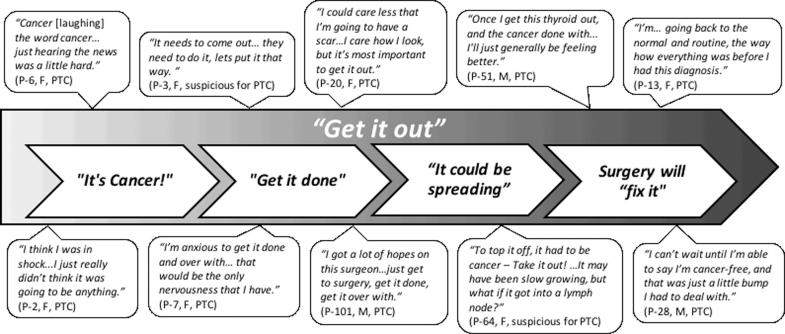

To examine participants' reactions to their diagnosis, codes were queried and analyzed by the research team using memo writing. We explored patients' emotional and psychological responses to diagnosis and the influence of outside factors, including family, friends, and doctors. Once the “get it out” reaction was identified, we examined the data for consequences of the response and its impact on other aspects of treatment. The research team met throughout the analysis process to discuss descriptive memos and summaries of the data and collaboratively developed a conceptual model of the themes within the data (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Representative themes and quotations from participants characterizing their response to diagnosis with PTC or an indeterminate thyroid nodule. F, female; M, male; PTC, papillary thyroid cancer.

Results

We conducted 85 semistructured interviews with patients before undergoing surgery for a diagnosis of PTC (n = 50) or an indeterminate thyroid nodule (n = 35). Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. Interviews lasted an average of 60 minutes (range 45–120 minutes). To illustrate the range of participant responses, quotes are labeled with the participant's study number (P-#), sex (male [M] or female [F]), and biopsy result (PTC, suspicious for PTC, or indeterminate for Bethesda III or IV). We did not observe systematic differences in the responses of patients with confirmed PTC and those with an indeterminate thyroid nodule.

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Participants (n = 85)

| Characteristic | Cohort, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at consent (years) (±SD) | 48.2 (±13.5) |

| Female | 62 (73) |

| Caucasian | 83 (98) |

| Some college/associates degree graduatea–c | 28 (33) |

| College graduate | 25 (29) |

| Higher degree graduate | 23 (27) |

| Currently employeda | 62 (73) |

| Marriedb | 65 (76) |

| Former smokera | 23 (35) |

| Never smokera | 62 (73) |

| Past surgeriesc | 70 (82) |

| Incidentally found nodule | 32 (38) |

| One or more chronic conditionsb | 43 (51) |

| Personal cancer historyc | 10 (12) |

| Family cancer historyc | 68 (80) |

Four respondents did not provide the indicated information.

Two respondents did not provide the indicated information.

One respondent did not provide the indicated information.

SD, standard deviation.

Get it out

The dominant theme that characterized participants' reaction to diagnosis was a strong desire to “get it out,” referring to getting the cancer or potential cancer out of their bodies (Fig. 1). Participants' comments ranged from brief statements, such as: “Just get it out!” (P-2, F, PTC) or “I want to get this thyroid out. I'm done with it!” (P-51, M, PTC) to more in-depth discussion related to the undesirable presence of the cancer:

“…it's still sitting there, in my throat, and I gotta get it out…I just, I just, I gotta get this out of there… just yank it out!” (P-35, M, indeterminate)

The “get it out” reaction emerged unprompted in the majority of interviews (n = 46) and frequently in response to the open-ended question, “What concerns you most at this time?” Other frequently discussed concerns in response to this question involved worries related to surgery, such as scarring, effects on voice or swallowing, or anticipated difficulties related to recovery. The “get it out” reaction did not appear to be associated with participants' age, gender, tumor size, comorbidities, or cytology result.

Participants sometimes used the notion that they could “get it out” to reassure themselves and others. For example, one participant comforted others by saying: “This doesn't mean I'm gonna die… we're able to actually take this out.” (P-31, F, indeterminate)

It's cancer!

The diagnosis of PTC or an indeterminate thyroid nodule had an immediate emotional impact on many participants, because “it's cancer!” (Fig. 1). Reactions were characterized by shock, anxiety, and fear regardless of whether participants had a confirmed diagnosis of PTC or indeterminate cytology result (Fig. 1). The “C word” was at the root of participants' reactions:

“I fell apart… I cried… the initial shock when you hear the word cancer… it's not a word you want to hear.” (P-11, F, PTC)

“I've been scared to death ever since [the biopsy]… because it's cancer, or it could be.” (P-35, M, indeterminate)

A few participants felt that the diagnosis of PTC or possible cancer was such a major disruption to their life that everything had to be put on hold until surgery. Participants recounted that once someone has a cancer diagnosis:

“You can pretty much take everything else off your calendar…” (P-6, F, PTC)

“You have to take time off of work, you have to figure out and rearrange your busy schedule, and you know, who has time for cancer? Nobody.” (P-5, F, suspicious for PTC)

Not all patients experienced such a strong emotional reaction to their diagnosis. Knowledge about PTC being very treatable did decrease concerns among some participants:

“It just didn't really bother me…the only difference is I have the [diagnosis] now, but I've had this cancer… and I've been doing fine.” (P-37, F, PTC)

“I wasn't worried about it because I did research, and I know that normally with the thyroid, if it's cancerous, it's pretty common to be able to take it out and not have a problem. So I'm not real concerned.” (P-34, M, indeterminate)

However, many participants still expressed the desire to “get it out” even if they did not experience fear or anxiety in response to their diagnosis or were reassured by the excellent prognosis of PTC.

Urgency to get it done

Participants' need to “get it out” was often accompanied or followed by a sense of urgency to have cancerous tissue surgically removed. This urgency was expressed by participants through their desire to “get it done” as soon as possible, referring to surgery (Fig. 1). This finding was striking and unexpected, as none of the interview questions were designed to elicit a patient's sense of urgency. Many participants also reported being educated by their surgeon that PTC was slow-growing. One participant stated:

“I got a lot of hopes on this surgeon getting it done and over…just get to surgery, get it done, get it over with.” (P-101, M, PTC)

For some participants, the urgency to “get it done” was accompanied by anxiety and stress manifested by trouble sleeping. Others just wanted to get the cancer out of their body as soon as possible, but they did not describe stress reactions.

“I don't want to keep losing sleep over it. I just want it done and gone.” (P-89, F, PTC)

“I haven't really been nervous about it or anything. I'm just ready to go…at this point I'm like, ‘Ok, let's just get it done.’” (P-23, F, suspicious for PTC)

Difficulty waiting for surgery

Participants' desire and sense of urgency to get the cancer or nodule out was especially apparent when they described their difficulty waiting for surgery. Participants were not prompted to discuss wait time, but many independently described anxiety and worry they experienced from not being able to have surgery right away. One participant characterized the wait as “the hardest part” and “psychologically difficult” (P-6, F, PTC), while another stated frankly, “I don't want to wait” (P-75, F, PTC). Others said:

“Waiting is the worst part, because for me, I'm like let's just go! Let's go and do this!…otherwise you get nervous or scared.” (P-37, F, suspicious for PTC)

“Even though I was told…‘This is very slow growing, waiting isn't going to matter.’ It matters for your mental state.” (P-27, F, suspicious for PTC)

You can't watch cancer: it could be spreading

Several participants expressed anxiety about knowing there was cancer in their bodies, and they frequently voiced worry over the possibility that the cancer could be spreading while they waited for surgery. One participant said they hoped the doctors would get it out “so it doesn't travel anywhere else in my body” (P-11, F, PTC), while another participant shared:

“I'm struggling because I'm thinking, ‘I have cancer in here right now. We need to get this out. And it could be spreading through my lymph nodes.’” (P-20, F, PTC)

Some participants' concerns about the possibility of metastasis was the main way they expressed their fear and worry about cancer, while some also shared the belief that cancer has to be removed or actively treated. For example, one participant stated:“It's still gotta get outta here! You can't just leave it!” (P-45, F, indeterminate)

Surgery will “fix it”

Participants often viewed thyroid cancer as a discrete problem that could be “fixed” with surgery (Fig. 1). They believed that getting the cancer out of the body would allow them to be “done and over.” One participant used an auto-repair metaphor to describe this view:

“Ok, let's get this fixed, you know? We'll get you fixed up… almost like a car, you know, open the hood, get you fixed up, get you going.” (P-73, M, PTC)

Participants also used “fix it” language when talking about the urgency to get the cancer out of their body. One participant shared:

“I would've had surgery the next day. I was like ‘Ok let's just fix it…I want to be done with that piece of it.” (P-6, F, PTC)

Participants often anticipated that surgery would return their life to normal and resolve or “fix” their emotional and psychological stress, because the cancer would be gone (Fig. 1). Some anticipated experiencing peace of mind. Participants stated:

“I think I will be happier, more energetic [after surgery], because I won't have this worry over my head…some of that stress will go away.” (P-16, F, PTC)

“I think the smart thing to do is to remove it…and it's peace of mind for me to get it out of there.” (P-73, M, PTC)

The idea that removing the cancer with surgery would reduce patients' worry also occasionally came from physicians. One participant recalled their surgeon advising:

“Just take it out…[you] just won't have to worry about it anymore.” (P-38, M, indeterminate)

Minimizing the likelihood and severity of potential adverse outcomes

The need to “get it out” led some participants to minimize the risk of potential adverse treatment effects, such as complications or the need to take a lifelong thyroid hormone. Participants often acknowledged that surgical complications were possible, but they downplayed the degree to which these negative outcomes would affect them. They felt that potential complications such as vocal cord paralysis or visible scars on their neck would be worth having, as long as they meant the cancer was gone (Fig. 1).

“The important thing to me would be to get that cancer out, and those things [referring to complications]…would come secondary. What good is having a good voice if you've got cancer… you've gotta get that out…” (P-20, F, PTC)

“They have to be super careful they don't nick anything. There's always a danger when you have surgery…that doesn't really alarm me because it needs to come out.” (P-3, F, suspicious for PTC)

The desire to remove the entire thyroid and get the cancer out also led some participants to minimize the impact of living without a thyroid gland. One participant believed they would “just have to take a little pill for the rest of my life” (P-7, F, PTC). Others predicted:

“…as long as they get all of it out of there, then I don't see it [referring to cancer] affecting very much other than the medications I may have to do.” (P-35, M, indeterminate)

Discussion

This qualitative study demonstrated that patients with PTC and indeterminate thyroid nodules often experience intense reactions to their diagnosis characterized by the need to “get it out.” This need is accompanied by a sense of urgency and a desire to “get it done” and over with because “it's cancer!.” Participants viewed surgery as a way to “fix” their disease, allowing them to stop worrying and return to their life the way it was before their diagnosis. The need to get the cancer or potential cancer out of the body often outweighed the potential for complications or other adverse effects of surgery. While surgeons frequently educated participants about the slow-growing nature of PTC, this education came after their emotional response evoked by the “C word.” These findings have significant implications for patients with thyroid cancer and their physicians when developing strategies to support shared decision making and implement less extensive treatment, such as lobectomy or surveillance.

To the best of our knowledge, this investigation is the first to prospectively characterize patients' response to a diagnosis of PTC or an indeterminate nodule. Patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer have an excellent prognosis yet appear to have an emotional reaction similar to that described in patients with more aggressive cancers (34–36). In a retrospective study from Australia by Nickel et al. that interviewed patients with <1 cm PTC after treatment, some recalled feeling shock, panic, or worry when they were diagnosed, particularly in reaction to the word “cancer” (37). Many also expressed a need to “get it out” or heard such from their physician (36). Therefore, the emotional reaction to diagnosis may occur regardless of cancer or nodule size. Misra et al. similarly found that diagnosis of recurrent thyroid cancer elicits shock followed by negative emotions, including fear, anger, and sadness (38). In the current study, participants' emotional response was striking and seemed to reflect societal beliefs and cultural norms related to the word “cancer” as well as the erroneous belief that all cancers are deadly (36,39,40). While referring to thyroid cancer as the “good cancer” can have an untoward effect on patients, strategies to educate and prepare patients undergoing biopsy for a possible cancer diagnosis may be effective and necessary for implementing less extensive management (41,42).

In this study, we also observed emotional stress and the “get it out” reaction in patients who did not have a confirmed cancer diagnosis, but had indeterminate cytology results. This finding has not been previously described. Byrne et al. found similar results in patients undergoing lung cancer screening (43). Those with an indeterminate or suspicious lung screening result experienced increased state anxiety and fear of cancer. These findings are not surprising given the ubiquitous nature of cancer fear (39,40,44,45). Studies show that even in healthy adults, cancer is one of the most feared diseases, and at least a third of the general population worries about getting cancer (40,46). Educating the public about the differences between cancers and their outcomes may decrease fears once a patient is diagnosed.

The “get it out” response to diagnosis evoked by the word “cancer” has several clinical implications. In men with localized prostate cancer, the need to “get it out” is associated with choosing active treatment over surveillance (47,48). Men who experience “get it out” reactions are believed to make heuristic shortcuts and selectively interpret educational information related to cancer, which biases decision making and drives them to choose potentially overly aggressive treatment (49,50). Data also indicate that higher levels of anxiety after a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer are associated with patients choosing surgery as a treatment option (47). Similar heuristics likely impact patients with thyroid cancer. Such shortcuts in thinking almost certainly color how patients with thyroid cancer understand and incorporate educational information into their treatment decisions (36,51). Because less extensive management strategies are newly endorsed by the ATA for patients with low-risk thyroid cancer, understanding these emotional and psychological responses to diagnosis in the context of decision making is critical. These responses and the associative processing connected to the word “cancer” represent major barriers to active surveillance or less extensive surgery with lobectomy.

Another finding of this study that has significant practice implications is participants' belief that surgery will “fix” their cancer. The well-known “fix it” model of decision making describes how a medical problem, such as thyroid cancer, can be viewed as an isolated and correctable deviation from the norm where a medical or surgical “fix” returns a person to their properly functioning state (52). Using this mental model, patients may erroneously anticipate that surgery (specifically, total thyroidectomy) will return them to “normal” despite being educated otherwise. Patients may also falsely believe that their worries or fears will disappear once they are “fixed” and discount the possibility of complications, as observed in this study.

However, it is well documented that thyroid cancer survivors often do not return to “normal” and instead experience a reduced quality of life, debilitating fatigue, and/or suffer from permanent complications related to their voice or calcium regulation (14,22,26,53–57). Survivors also experience anxiety and fear of recurrence even when they are several years out from their initial treatment and experience cancer-related worry that is comparable to the general oncology population (58–60). Surgeons have been shown to use “fix it” language as a default, which may facilitate patients' beliefs and keep patients from considering all possible treatment outcomes and less extensive options (61).

Strategies to address cancer fear and the use of the “fix it” model will be necessary to move from “scared” to “shared” decision making for patients with thyroid cancer and indeterminate thyroid nodules in the era of increased treatment options. Experts have suggested slowing down the diagnosis and treatment decision-making process, utilizing decision aids, discussing complications at a second visit, and/or providing take-home educational materials about complications (47). Future interventions to educate these patients and support decision making should take into account the emotional impact of the diagnosis. Addressing cancer-related fears may facilitate patients' comprehension of potential outcomes and allow them to better incorporate this knowledge into their decision.

The major strengths of this study include the prospective qualitative design, inclusion of patients with indeterminate nodules, and large sample size. However, these data should be interpreted in the context of limitations. Data collection occurred at a single institution from patients who were clinically node-negative and enrolled in a clinical trial. Therefore, the results may not reflect the experiences of all patients with PTC, particularly those with positive lymph nodes, undergoing other management options, or not enrolled in the trial. The trial also excluded patients with other types of thyroid cancer and those with cancers <1 cm. Patients were also seen by 11 different surgeons whose comments during the consultation may have affected their reaction to their cancer diagnosis. The timing of disclosure of their diagnosis also may have affected patients' responses. In addition, there is potential for selection bias, though study procedures and protocols were designed to minimize this possibility. These included clearly defined eligibility criteria, screening all surgeons' clinics, inviting all eligible patients to participate, recruitment and consent by a trained nonclinical member of the research team, and scheduling interviews at a time convenient for participants. While the study included patients with indeterminate nodules, it was not designed to compare these patients with those with PTC. Unique issues that were not apparent in our interviews may exist in each cohort. Despite these limitations, these data shed new light on issues related to cancer fear that may significantly affect the treatment decision-making process.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that patients with PTC as well as those with indeterminate thyroid nodules often have a strong emotional reaction to their diagnosis characterized by a need to “get it out.” Despite having an excellent prognosis, this reaction appears similar to patients with other more aggressive cancers. The fear and anxiety evoked by the word “cancer” have the potential to overshadow patients' cognitive awareness and processing of cancer-related information. Further research and interventions are necessary to ensure adequate patient education, decision making and psychosocial support for patients newly diagnosed with PTC or an indeterminate nodule. Addressing cancer fear in patients with PTC will be key for implementing new guidelines that recommend less extensive treatment or active surveillance.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sarah Robbins, MPH for her assistance with study management and article preparation.

Disclaimers

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) or National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (Grant No. P30CA014520) and the NCI (Grant No. R01CA176911; PI's R.S.S. and N.P.C.). Dr. Pitt was supported by the NCI (Grant No. K08CA230204).

References

- 1. Davies L, Morris LG, Haymart M, Chen AY, Goldenberg D, Morris J, Ogilvie JB, Terris DJ, Netterville J, Wong RJ, Randolph G, Committee AESS. 2015. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Disease State Clinical Review: the increasing incidence of thyroid cancer. Endocr Pract 21:686–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Explorer Application. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/application (accessed March23, 2020)

- 3. McDow AD PS 2019. Extent of surgery for low-risk differentiated thyroid cancer. Surg Clin North Am 99:599–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gartland RM, Lubitz CC. 2018. Impact of extent of surgery on tumor recurrence and survival for papillary thyroid cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 25:2520–2525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L. 2016. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 26:1–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nickel B, Tan T, Cvejic E, Baade P, McLeod DSA, Pandeya N, Youl P, McCaffery K, Jordan S. 2019. Health-related quality of life after diagnosis and treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer and association with type of surgical treatment. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145:231–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosato L, Pacini F, Panier Suffat L, Mondini G, Ginardi A, Maggio M, Bosco MC, Della Pepa C. 2015. Post-thyroidectomy chronic asthenia: self-deception or disease? Endocrine 48:615–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ryu J, Ryu YM, Jung YS, Kim SJ, Lee YJ, Lee EK, Kim SK, Kim TS, Kim TH, Lee CY, Park SY, Chung KW. 2013. Extent of thyroidectomy affects vocal and throat functions: a prospective observational study of lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy. Surgery 154:611–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kong SH, Ryu J, Kim MJ, Cho SW, Song YS, Yi KH, Park DJ, Hwangbo Y, Lee YJ, Lee KE, Kim SJ, Jeong WJ, Chung EJ, Hah JH, Choi JY, Ryu CH, Jung YS, Moon JH, Lee EK, Park YJ. 2019. Longitudinal assessment of quality of life according to treatment options in low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinoma patients: active surveillance or immediate surgery (interim analysis of MAeSTro). Thyroid 29:1089–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jeon MJ, Lee YM, Sung TY, Han M, Shin YW, Kim WG, Kim TY, Chung KW, Shong YK, Kim WB. 2019. Quality of life in patients with papillary thyroid microcarcinoma managed by active surveillance or lobectomy: a cross-sectional study. Thyroid 29:956–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Griffin A, Brito JP, Bahl M, Hoang JK. 2017. Applying criteria of active surveillance to low-risk papillary thyroid cancer over a decade: how many surgeries and complications can be avoided? Thyroid 27:518–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oda H, Miyauchi A, Ito Y, Yoshioka K, Nakayama A, Sasai H, Masuoka H, Yabuta T, Fukushima M, Higashiyama T, Kihara M, Kobayashi K, Miya A. 2016. Incidences of unfavorable events in the management of low-risk papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid by active surveillance versus immediate surgery. Thyroid 26:150–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pitt SC, Lubitz CC. 2017. Editorial: complex decision making in thyroid cancer: costs and consequences-is less more? Surgery 161:134–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Applewhite MK, James BC, Kaplan SP, Angelos P, Kaplan EL, Grogan RH, Aschebrook-Kilfoy B. 2016. Quality of life in thyroid cancer is similar to that of other cancers with worse survival. World J Surg 40:551–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, James B, Nagar S, Kaplan S, Seng V, Ahsan H, Angelos P, Kaplan EL, Guerrero MA, Kuo JH, Lee JA, Mitmaker EJ, Moalem J, Ruan DT, Shen WT, Grogan RH. 2015. Risk factors for decreased quality of life in thyroid cancer survivors: initial findings from the North American Thyroid Cancer Survivorship Study. Thyroid 25:1313–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goldfarb M, Casillas J. 2014. Unmet information and support needs in newly diagnosed thyroid cancer: comparison of adolescents/young adults (AYA) and older patients. J Cancer Surviv 8:394–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morley S GM 2015. Support needs and survivorship concerns of thyroid cancer patients. Thyroid 25:649–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldfarb M, Casillas J. 2016. Thyroid cancer-specific quality of life and health-related quality of life in young adult thyroid cancer survivors. Thyroid 26:923–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hedman C, Djarv T, Strang P, Lundgren CI. 2016. Determinants of long-term quality of life in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma—a population-based cohort study in Sweden. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 55:365–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hedman C, Djarv T, Strang P, Lundgren CI. 2017. Effect of thyroid-related symptoms on long-term quality of life in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a population-based study in Sweden. Thyroid 27:1034–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Husson O, Haak HR, Buffart LM, Nieuwlaat WA, Oranje WA, Mols F, Kuijpens JL, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. 2013. Health-related quality of life and disease specific symptoms in long-term thyroid cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 52:249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Husson O, Nieuwlaat WA, Oranje WA, Haak HR, van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F. 2013. Fatigue among short- and long-term thyroid cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Thyroid 23:1247–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee JI, Kim SH, Tan AH, Kim HK, Jang HW, Hur KY, Kim JH, Kim KW, Chung JH, Kim SW. 2010. Decreased health-related quality of life in disease-free survivors of differentiated thyroid cancer in Korea. Health Qual Life Outcomes 8:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nies M, Klein Hesselink MS, Huizinga GA, Sulkers E, Brouwers AH, Burgerhof JGM, van Dam E, Havekes B, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Corssmit EPM, Kremer LCM, Netea-Maier RT, van der Pal HJH, Peeters RP, Plukker JTM, Ronckers CM, van Santen HM, Tissing WJE, Links TP, Bocca G. 2017. Long-term quality of life in adult survivors of pediatric differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:1218–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singer S, Lincke T, Gamper E, Bhaskaran K, Schreiber S, Hinz A, Schulte T. 2012. Quality of life in patients with thyroid cancer compared with the general population. Thyroid 22:117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tagay S, Herpertz S, Langkafel M, Erim Y, Bockisch A, Senf W, Gorges R. 2006. Health-related Quality of Life, depression and anxiety in thyroid cancer patients. Qual Life Res 15:695–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goswami S, Mongelli M, Peipert BJ, Helenowski I, Yount SE, Sturgeon C. 2018. Benchmarking health-related quality of life in thyroid cancer versus other cancers and United States normative data. Surgery 164:986–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goswami S, Peipert BJ, Mongelli MN, Kurumety SK, Helenowski IB, Yount SE, Sturgeon C. 2019. Clinical factors associated with worse quality-of-life scores in United States thyroid cancer survivors. Surgery 166:69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stinesen Kollberg K, Wilderang U, Thorsteinsdottir T, Hugosson J, Wiklund P, Bjartell A, Carlsson S, Stranne J, Haglind E, Steineck G. 2017. How badly did it hit? Self-assessed emotional shock upon prostate cancer diagnosis and psychological well-being: a follow-up at 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 56:984–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schneider DF, Cherney Stafford LM, Brys N, Greenberg CC, Balentine CJ, Elfenbein DM, Pitt SC. 2017. Gauging the extent of thyroidectomy for indeterminate thyroid nodules: an oncologic perspective. Endocr Pract 23:442–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cibas ES, Ali SZ. 2017. The 2017 Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Thyroid 27:1341–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charmaz K 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd Edition. Sage, London [Google Scholar]

- 33. Averill JB 2002. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res 12:855–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brocken P, Prins JB, Dekhuijzen PNR, van der Heijden HFM. 2012. The faster the better?—A systematic review on distress in the diagnostic phase of suspected cancer, and the influence of rapid diagnostic pathways. Psychooncology 21:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. 2001. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 10:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jensen CB, Saucke MC, Francis DO, Voils CI, Pitt SC. 2020. From overdiagnosis to overtreatment of low-risk thyroid cancer: a thematic analysis of attitudes and beliefs of endocrinologists, surgeons, and patients. Thyroid 30:696–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nickel B, Brito JP, Moynihan R, Barratt A, Jordan S, McCaffery K. 2018. Patients' experiences of diagnosis and management of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 18:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Misra S, Meiyappan S, Heus L, Freeman J, Rotstein L, Brierley JD, Tsang RW, Rodin G, Ezzat S, Goldstein DP, Sawka AM. 2013. Patients' experiences following local-regional recurrence of thyroid cancer: a qualitative study. J Surg Oncol 108:47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Agustina E, Dodd RH, Waller J, Vrinten C. 2018. Understanding middle-aged and older adults' first associations with the word “cancer”: a mixed methods study in England. Psychooncology 27:309–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vrinten C, McGregor LM, Heinrich M, von Wagner C, Waller J, Wardle J, Black GB. 2017. What do people fear about cancer? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of cancer fears in the general population. Psychooncology 26:1070–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Easley J MB, Robinson L. 2013. Its the “good” cancer, so who cares? Percieved lack of support_among young thyroid cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 40:596–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Randle RW, Bushman NM, Orne J, Balentine CJ, Wendt E, Saucke M, Pitt SC, Macdonald CL, Connor NP, Sippel RS. 2017. Papillary thyroid cancer: the good and bad of the “good cancer”. Thyroid 27:902–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Byrne MM, Weissfeld J, Roberts MS. 2008. Anxiety, fear of cancer, and perceived risk of cancer following lung cancer screening. Med Decis Making 28:917–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Murphy PJ, Marlow LAV, Waller J, Vrinten C. 2018. What is it about a cancer diagnosis that would worry people? A population-based survey of adults in England. BMC Cancer 18:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Whitaker KL, Cromme S, Winstanley K, Renzi C, Wardle J. 2016. Emotional responses to the experience of cancer ‘alarm’ symptoms. Psychooncology 25:567–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vrinten C, Waller J, von Wagner C, Wardle J. 2015. Cancer fear: facilitator and deterrent to participation in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent 24:400–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Volk RJ, McFall SL, Cantor SB, Byrd TL, Le YC, Kuban DA, Mullen PD. 2014. ‘It's not like you just had a heart attack’: decision-making about active surveillance by men with localized prostate cancer. Psychooncology 23:467–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Henrikson NB, Ellis WJ, Berry DL. 2009. “It's not like I can change my mind later”: reversibility and decision timing in prostate cancer treatment decision-making. Patient Educat Counsel 77:302–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Penson DF 2012. Factors influencing patients' acceptance and adherence to active surveillance. J Natl Cancer Institute Monographs 2012:207–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Steginga SK, Occhipinti S. 2004. The application of the heuristic-systematic processing model to treatment decision making about prostate cancer. Med Decis Making 24:573–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pitt SC, Wendt E, Saucke MC, Voils CI, Orne J, Macdonald CL, Connor NP, Sippel RS. 2019. A qualitative analysis of the preoperative needs of patients with papillary thyroid cancer. J Surg Res 244:324–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lynn J, DeGrazia D. 1991. An outcomes model of medical decision making. Theoret Med 12:325–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Drabe N, Steinert H, Moergeli H, Weidt S, Strobel K, Jenewein J. 2016. Perception of treatment burden, psychological distress, and fatigue in thyroid cancer patients and their partners - effects of gender, role, and time since diagnosis. Psychooncology 25:203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gamper EM, Wintner LM, Rodrigues M, Buxbaum S, Nilica B, Singer S, Giesinger JM, Holzner B, Virgolini I. 2015. Persistent quality of life impairments in differentiated thyroid cancer patients: results from a monitoring programme. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag 42:1179–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Papaleontiou M, Hughes DT, Guo C, Banerjee M, Haymart MR. 2017. Population-based assessment of complications following surgery for thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:2543–2551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kletzien H, Macdonald CL, Orne J, Francis DO, Leverson G, Wendt E, Sippel RS, Connor NP. 2018. Comparison between patient-perceived voice changes and quantitative voice measures in the first postoperative year after thyroidectomy: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144:995–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Krekeler BN, Wendt E, Macdonald C, Orne J, Francis DO, Sippel R, Connor NP. 2018. Patient-reported dysphagia after thyroidectomy: a qualitative study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144:342–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hedman C, Djarv T, Strang P, Lundgren CI 2018. Fear of recurrence and view of life affect health-related quality of life in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a prospective swedish population-based study. Thyroid [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1089/thy.2018.0388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hedman C, Strang P, Djarv T, Widberg I, Lundgren CI. 2017. Anxiety and fear of recurrence despite a good prognosis: an interview study with differentiated thyroid cancer patients. Thyroid 27:1417–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bresner L, Banach R, Rodin G, Thabane L, Ezzat S, Sawka AM. 2015. Cancer-related worry in Canadian thyroid cancer survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:977–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kruser JM, Pecanac KE, Brasel KJ, Cooper Z, Steffens NM, McKneally MF, Schwarze ML. 2015. “And I think that we can fix it”: mental models used in high-risk surgical decision making. Ann Surg 261:678–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]