Abstract

In this study, some chemical components of hemp seed, which widely consumed as snack food in Middle East were determined. The effects of different roasting temperatures (140, 160 and 180 °C) and times (0–60 min) on the oxidative stability and antioxidant content of hemp seed oil were investigated. Hemp seed oil contained high levels of linoleic acid (54.85%), α-linolenic acid (18.13%) and γ-tocopherol (707.47 mg/kg oil). While tocopherol isomers decreased with increasing roasting time and temperature, total phenolic content and antioxidant activity showed increasing trend. The peroxide and p-anisidine values of roasted samples varied from 1.33 to 3.09 meq O2 /kg oil and 1.65 to 43.27, respectively. The peroxide and p-anisidine values of samples were simultaneously generated at the early stage of roasting. Kinetic evaluation of data showed that peroxides act as limiting factor in autocatalytic oxidation reactions. The order and rate constant regarding peroxide value were similar with those of p-anisidine value. The effects of roasting temperature and time on the oxidation parameters and antioxidant contents of samples were significant (p < 0.05). Based on peroxide and p-anisidine values, roasting at 140–160 °C for 35 min or at 180 °C for 15 min are recommended to provide good quality roasted hemp seed.

Keywords: Antioxidant activity, Hemp seed, Kinetic parameters, Oxidative stability, Tocopherols, Total phenolic content

Introduction

Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) is a single-year herbaceous plant. It is an economically valuable plant as an important source of food and fiber. Hemp has been used as a source of food, fiber and medicine for thousands of years. The plant has grown naturally in western and Central Asia and has also been cultivated commercially in developed countries (EU, Japan, Canada and US). However, cultivation of hemp was prohibited after the 1930s around the world because of the presence of phytochemical drug δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which can cause psychoactive effects (Paz et al. 2014). Recently, interest in hemp has been increased with the development of new cultivars with low THC content (≤ 0.3% THC). The planting area and crop have similarly increased around the world due to its multiple utilities in several industries. Hemp has been cultivated for its fiber and seed. Hemp seed is used as a food for human and domesticated animals, and as an oil source for different food, chemical, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries (Paz et al. 2014; Porto et al. 2015; Oomah et al. 2002).

Hemp seed contains 25–35% oil, 20–25% protein, 20–30% carbohydrate, 10–15% insoluble fibre and several minerals (Deferne and Pate 1996). Hemp seed oil contains several components such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and tocopherols which have beneficial effects on human health. Linoleic (n-6) and α-linolenic (n-3) acids are PUFAs found in hemp seed oil. These are known as essential fatty acids, which play important roles in many metabolic processes. Essential fatty acids serve as precursors of biochemicals which regulate many body functions, and low levels of essential fatty acids may be a factor in a number of illnesses (Porto et al. 2015). Hemp seed oil is considered to be perfectly balanced with regard to the ratio of n-6 and n-3 fatty acids (3:1) for human nutrition. Therefore, in addition to its nutritional value, hemp seed oil has demonstrated positive health benefits regarding lipid metabolism, cardiovascular health, immunomodulatory effects and dermatological diseases (Callaway 2004; Paz et al. 2014). Porto et al (2015) noted that seed oils from different hemp varieties contained 2.89–5.88% palmitic, 1.76–2.37% stearic, 9.25–12.31% oleic, 55.98–59.37% linoleic, 3.19–6.42% γ-linoleic, 17.34–19.70% α-linoleic and 0.74–1.58% eicosenoic acids.

Hemp seed oil also contains high amounts of tocopherols. Tocopherols may reduce the risk of cancer, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases (Jiang et al. 2001). Tocopherols are well known antioxidants and provide protection against oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids during processing and storage. Paz et al (2014). reported that the α-, β-, γ- and δ-tocopherol contents of the hemp seed oil were 3.22, 0.81, 73.38 and 2.87 mg/100 g oil, respectively. γ- Tocopherol is the dominant tocopherol in hemp seed oil. It is more powerfull than α-tocopherol in detoxifying lipophilic electrophiles and inhibiting prostate cancer cell proliferation (Jiang et al. 2001). Recently, hemp seed has been identified as a natural source of polar antioxidants. The assay of phenolic content and antioxidant activity in defatted hemp seed exhibited considerable high values. Total phenolic and flavonoid contents, and DPPH radical scavenging activities (IC50) of methanolic extracts from defatted hemp seed samples belong to three hemp varieties were 4.57–8.04 mg GAE/100 mg extract, 5.39–10.90 mg RE/100 mg extract and 0.1–0.27 mg/mL extract, respectively (Lesma et al. 2014).

Hemp seed as a food has been documented throughout recorded history. Some traditional hemp seed foods are still consumed in the Baltic States, Middle East and China. It has also become a popular healthy food in North America and Europe during the last decade (Chen et al. 2010). Hemp seed is known as Çedene in Turkey, and roasted hemp seed is consumed as a popular snack food in Eastern Anatolia (Turkey).

Roasting is a widely used process in food industry. Roasting deactivates antinutritional components and undesirable enzyms, and gives characteristic flavour and brown colour to final product. Furthermore, roasting ruptures the oil cells and promotes coalescing of small oil particles into larger oil droplets, consequently increases the oil yield during pressing (Wijesundera et al. 2008). Roasting has a controversial influence on the stability of fat-containing foods. Cammerer and Kroh (2009) indicated that roasted linseeds became rapidly rancid, however, the oxidative stability of peanuts increased with increasing roasting temperature and time. Several reports have described the positive effect of roasting on oxidative stability of different seed oil (Matthaus 2013; Shrestha and Meulenaer 2014; Rozanska et al. 2019). Jannata et al (2013) noted that both γ-tocopherol and total phenolic contents of roasted sesame seeds were rised with increasing roasting time and temperature. There are some studies about kinetics of color and textural changes of different foods during roasting (Demir and Cronin 2005; Demir et al. 2002). However there is no literatüre about kinetics of oil oxidation in oil seeds during roasting. Javidipour et al (2017) noted that the reaction orders and rate constants for peroxide and hexanal formation in different oils during microwave heating were forund to be 0.1, 1.74 and 1.0, 0.4344 for hazelnut; 0.1, 0.91 and 1.0, 0.3643 for olive; 0.1, 4.88 and 1.0, 0.5827 for soybean; 0.1, 4.5 and 1.0, 0.6107 for sunflower oil.

This study was carried out to determine the effects of different roasting temperatures and times on some compositional and oxidative parameters of hemp seed oil. In addition, kinetic parameters of lipid oxidation reactions during roasting were investigated as a function of temperature.

Materials and methods

Sample

Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seed samples were obtained from local farmer in Vezirköprü, in the north region of Anatolia harvested in 2017. After harvesting, sun-dried hemp seeds were immediately transported to the laboratory, and stored at 4 °C in dark until used.

Reagents and chemicals

n-Hexane for chromatography, methanol, chloroform, n-hexane, isopropanol, isooctane, p-anisidine, sodium thiosulfate, Folin–Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent, sodium carbonate, and acetic acid were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) stable radical and standards of gallic acid and mix fatty acid methyl esters were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). α-, γ- and δ-tocopherol were obtained from Supelco (Bellefonte, PA, USA).

Roasting treatments

Hemp seeds were equally spread as a thin layer (~ 5 mm) in aluminium pans for roasting. Samples were roasted in a labratory oven (Memmert, UN55, Germany) at 140, 160 and 180 °C for 60 min. At 5 min intervals, sample (50 g) was taken and cooled to room temperature and then stored at − 26 °C until analysis.

Determination of dry matter, protein and total oil

Dry matter, protein and total oil contents were determined according to the methods given by AOAC (2003).

Oil extraction

Hemp seed oil was extracted by cold extraction for peroxide, p-anisidine, fatty acid and tocopherol assays. For oil extraction, hemp seeds were ground with a coffee mill (Arnica AA1708, İstanbul). Ground hemp seeds (35 g) and n-hexane (130 mL) mixture was homogenized with a homogenizer (Isolab, 621.11.001, China) for 30 s at 10,000 rpm. Mixture was placed in the extraction flask under nitrogen, and shaked with circular shaker for 2 h at 180 rpm in dark at room temperature. Mixture was filtered, and than solvent layer from pooled filtrates was removed by a rotary vacuum evaporator (IKA, RV-10, Germany). Extracted oil was dried by adding powdered anhydrous sodium sulphate. Then sodium sulphate residue was separated off by filtration. The extracted oil was transferred to glass amber vials under nitrogen flow and stored at – 26 °C before further analyses.

Fatty acid composition

The fatty acid composition of hemp seed oil was determined by gas chromatography. The methyl esters of fatty acids were prepared according to International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Method No 2.301 (IUPAC 1991). Fatty acid profile was analysed using an Agilent 6890 N gas chromatograph equipped with flame ionization detector (FID). A capillary column DB 23 (30 m × 0.25 mm id × 0.25 mm film thickness, Agilent Technologies, J&W Scientific, USA) was used. Injector, column, and detector temperatures were 230, 190 and 240 °C, respectively. Split ratio was 1:100. Carrier gas was helium with a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min.

Peroxide value (PV) and p-anisidin value (AV) determination

The PVs of the hemp seed oils were determined using a titration method according to AOCS Official Method Cd 8–53 (AOCS 1997). AVs of hemp seed oils were determined according to AOCS Official Method Cd 18–90 using an Agilent 8453 spectrophotometer (AOCS 1992). The total oxidation value (TOTOX) was calculated by the following equation (Wai et al. 2009).

| 1 |

Tocopherol content

Analysis of tocopherols were carried out by using an HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) that consisted of a LC-20 AD gradient pump, a Rheodyne 7725i valve furnished with 20 μL loop, a SPD-M20A diode array detector and CTO-10AS VP column oven. The method described by AOCS (Official Method No: Ce 8-89) was used for HPLC, with slight modifications (AOCS 1993). Diluted hemp seed oil with n-hexane was filtered through a 0.45 mm polytetrafluoroethylene membrane filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and analysed by HPLC. Separation of tocopherols was carried out using a LiChrosorb Si60 (250 × 4.6 mm i.d., particle size of 5 µm) column (Hichrom, Reading, U.K.). The mobile phase was a mixture of n-hexane and isopropanol (99:1, v/v). Elution was performed at a solvent flow rate of 1 mL/min with an isocratic program. Detection was made at 295 nm and 25 °C. The compounds appearing in chromatograms were identified based on their retention times and spectral data by comparison with standards.

Total phenolic content

Defatted ground hemp seed (5 g) and methanol (9.5 mL) were placed into a centrifuge tube and homojenized with homogenizer for 15 sn at 10,000 rpm. Mixture shaked with circular shaker (Jeio Tech, OS-4000, South Korea) for 2 h in dark at room temperature, and then the mixture was centrifuged at 8000 g (Nuve, NF1200R, Turkey) for 10 min at 20 °C. The residue was separated, and the above procedure was repeated twice using the residue. Pooled supernatants were adjusted to 25 mL with methanol. Total phenolic content in methanolic extracts was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method (Singleton and Rossi 1965). Results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent (mg GAE) per gram of defatted hemp seed.

DPPH Assay

Antioxidant activity of hemp seed methanolic extract was measured according to Pyo et al (2004). Hemp seed methanolic extract (0.1 mL) was added to 3.9 mL of DPPH solution (0.025 g/L in methanol). The mixture was left for 60 min in dark at room temperature until the reaction reached a plateau. The absorbances of sample and control at 515 nm were measured by spectrophotometer (Agilent, 8453, USA). The inhibitory percentage of DPPH was calculated according to the following equation:

| 2 |

where A0 is the absorbance of the control, and AS is the absorbance of the sample.

Kinetic calculations

In order to estimate the kinetic parameters, experimental results were analysed acoording to Baştürk et al (2007). Lipid oxidation reactions defined as the autocatalyzed reaction by hydroperoxides. Based on this knowledge, Özilgen and Özilgen (1990) provided Eq. (3), according to PV determination:

| 3 |

where C is the concentration of the total oxidation products, Cmax is the maximum attainable concentration of oxidation product (in this case, hydroperoxides), k is the rate constant and t is time. In the early stages of the lipid oxidation process when C < < C max, the term 1–C/Cmax = 1, and Eq. (4) is obtained (Kamal-Eldin and Yanishlieva 2005).

| 4 |

A kinetic model (Eq. 5) was derived from a first-order autocatalytic reaction and a second-order decomposition reaction (Crapiste et al. 1999):

| 5 |

where PV is the peroxide value, and k1 and k2 are the autocatalytic formation and decomposition rate constants, respectively. Equations (6) and (7) were used for the determination of the orders and the rate constants of the reactions. The kinetic model of autoxidation reaction is written as Eq. (6):

| 6 |

where α and β are the orders of the oxidation and decomposition reactions, respectively.

The decomposition reaction rate of PV is equal to the production reaction rate of AV (Eq. 7):

| 7 |

Increasing rates of AV were determined using the measured AV during roasting periods. Equation (7) was linearized and Eq. (8) was obtained:

| 8 |

ln(dAV/dt) versus ln(PV) was plotted for each sample, and the slope and intercept of the line were determined as β and ln(k2), respectively. Thereafter, Eq. (6) was rewritten as Eq. (9)

| 9 |

and then linearized, and Eq. (10) was obtained:

| 10 |

ln(dPV / dt + k2PV β) versus ln(PV) was plotted for each sample, and the slope and intercept of the line were determined as α and ln(k1), respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in SAS package program version 9.4. Roasting experiments were carried out in three replicates. The differences between the fatty acid contents of unroasted and roasted samples were analysed by one-way ANOVA. Data from oxidative stability, antioxidant contents and antioxidant activity of samples were obtained from factorial design. In factorial design, there were 3 levels for temperature in all analysis, 12 levels for time in oxidation stability analysis and 6 levels for time in antioxidant component analysis. A general linear model was used to compare differences in means among groups and to determine the interaction effects. Duncan method was used to evaluate differences between means.

Results and discussion

Effect of roasting on different compositional parameters

Some chemical properties of unroasted hemp seed were given in Table 1. Hemp seed had high dry matter (91.49%) ash (5.06%), protein (26.31%) and oil (37.27%) contents. Callaway (2004) noted that dry matter, ash, protein and oil contents of hemp seed were 93.5, 5.6, 24.0 and 35.5%, respectively. Our results regarding the protein and oil contents of hemp seed were higher than results reported by Callaway (2004). Kiralan et al. (2010) noted that the oil content of hemp seeds from Turkey ranged from 29.6 to 36.5%. Our result was slightly higher than those reported by Kiralan et al. (2010).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of hemp seed

| Hemp seed | |

|---|---|

| Dry matter (%) | 91.49 ± 0.47 |

| Ash (%) | 5.06 ± 0.34 |

| Protein (%) (N = 6.25) | 26.13 ± 0.23 |

| Oil (%) | 37.27 ± 1.64 |

| Tocopherols (mg/kg oil) | |

| α- Tocopherol | 52.92 ± 0.71 |

| γ- Tocopherol | 707.47 ± 2.42 |

| δ- Tocopherol | 38.47 ± 0.52 |

| Total tocopherol | 798.86 ± 2.22 |

| Total phenolic content (mg GA eq./kg defatted matter) | 1022.11 ± 0.00 |

| DPPH (% inhibition) | 31.76 ± 1.34 |

Data are expressed as mean ± S.D

Fatty acid compositions identified in oils extracted from hemp seed samples before and after roasting were given in Table 2. The major fatty acid in hemp seed oil was linoleic (54.85%), followed by α-linolenic (18.65%), oleic (15.12%), palmitic (6.31%), stearic (2.83%), eicosenoic (1.09%), arachidic (1.03%), γ-linolenic (0.52%) and palmitoleic (0.15%) acids. Petrovic et al. (2015) reported that palmitic, stearic, oleic, linoleic, α- and γ-linolenic acid levels of hemp seed from different geographic origins varied in the ranges of 5.91–7.38, 2.13–2.99, 9.78–14.1, 55.76–57.26, 14.79–19.91 and 0.51–4.55%, respectively. Our results are in accordance with results reported by Petrovic et al. (2015). Kiralan et al. (2010) investigated the fatty acid compositions of hemp seeds harvested from different locations in Turkey. Palmitic, stearic, oleic, linoleic, α- and γ-linolenic acid levels of hemp seed oil from Vezirkopru province were found to be 6.46, 2.44, 13.2, 56.16, 18.58 and 0.97%, respectively. Our results were in good agreement with results reported by Kiralan et al. (2010).

Table 2.

Fatty acid compositions of samples at the beggining and after roasting at different temperatures (% methyl esters)

| Fatty Acids | Unroasted | 140 °C | 160 °C | 180 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palmitic acid (C16:0) | 6.31 ± 0.30a | 6.18 ± 0.19a | 6.24 ± 0.12a | 6.32 ± 0.21a |

| Palmitoleic acid (C16:1) | 0.15 ± 0.05a | 0.12 ± 0.01a | 0.12 ± 0.01a | 0.07 ± 0.08a |

| Stearic acid (C18:0) | 2.83 ± 0.02a | 2.85 ± 0.00a | 2.86 ± 0.04a | 2.87 ± 0.05a |

| Oleic acid (C18:1) | 15.12 ± 0.04a | 15.00 ± 0.06a | 15.05 ± 0.01a | 15.12 ± 0.02a |

| Linoleic acid (C18:2 n6) | 54.85 ± 0.23a | 54.80 ± 0.38a | 55.03 ± 0.13a | 55.02 ± 0.05a |

| γ-Linolenic acid (C18:3 n6) | 0.52 ± 0.04a | 0.54 ± 0.01a | 0.52 ± 0.02a | 0.52 ± 0.08a |

| α -Linolenic acid (C18:3 n3) | 18.13 ± 0.16a | 18.29 ± 0.06a | 18.16 ± 0.08a | 18.11 ± 0.08a |

| Arachidic acid (C20:0) | 1.03 ± 0.13a | 0.96 ± 0.03a | 0.94 ± 0.02a | 0.96 ± 0.01a |

| Eicosenoic acid (C20:1) | 1.09 ± 0.01a | 1.28 ± 0.30a | 1.08 ± 0.02a | 1.07 ± 0.05a |

| Total SFA | 10.17 ± 0.32a | 9.99 ± 0.22a | 10.00 ± 0.18a | 10.15 ± 0.27a |

| Total USFA | 89.34 ± 0.90a | 89.49 ± 0.41a | 89.44 ± 0.19a | 89.39 ± 0.32a |

| Total MUFA | 16.36 ± 0.10a | 16.40 ± 0.37a | 16.25 ± 0.18a | 16.26 ± 0.15a |

| Total PUFA | 72.98 ± 0.20a | 73.09 ± 0.04a | 73.19 ± 0.10a | 73.13 ± 0.16a |

Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. Numbers followed by different superscript lowercase letters within the same row are significantly different (p < 0.05)

PUFA (72.98%) was the main group of fatty acids in hemp seed oil. Oleic acid was the dominant MUFA. In the last decade, benefical effects of oils on health have been related to the ratio of omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 fatty acids (n-6/n-3 ratio). High n-6/n-3 ratio increases the risk of diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular and inflammatory. Increasing the level of omega-3 (low n-6/n-3 ratio) reduces risk of these diseases and improves brain functions, mood, intelligence etc. (Luzaić et al. 2018). In this study, n-6/n-3 ratio in hemp seed oil was found to be 3:1, which was recommended as a perfect balance for n-6/n-3 ratio in human nutrition (Callaway 2004; Paz et al. 2014). Therefore, hemp seed oil had healthy fatty acid profile due to its high omega-3 fatty acid content (α-linolenic acid), consequently its low n-6/n-3 ratio.

The fatty acid compositions of hemp seed oils obtained from roasted seeds (140, 160 and 180 ºC) were given in Table 2. Roasting at three different temperatures leaded to small changes in fatty acid compositions of samples. Roasting did not significantly affect the fatty acid composition of hemp seed oil (p > 0.05). The shell and the antioxidants content (tocopherols, phenolics, melanoidins etc.) of hemp seed should be providing protective effect against oxidation. Wijesundera et al. (2008) noted that roasting did not affect the fatty acid compositions of canola and mustard seed oils. Rozanska et al. (2019) reported that Maillard reaction products such as nitrogenous macromelcules-melanoidins formed during roasting protected PUFA against oxidation.

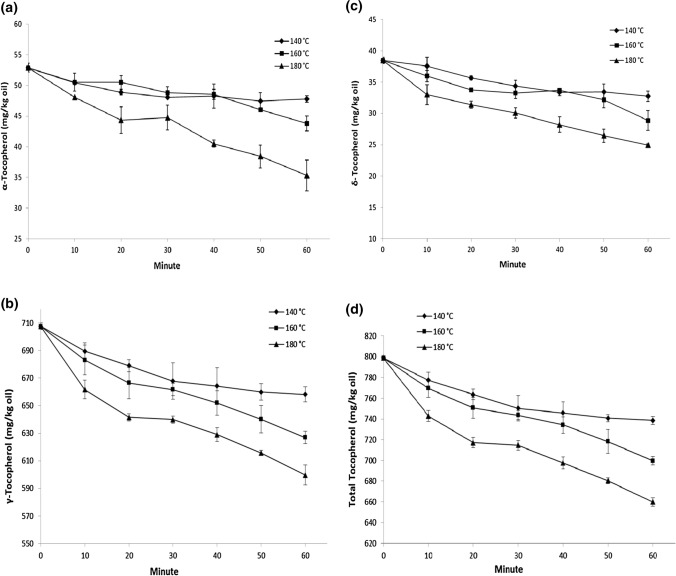

Tocopherols compete with oil to bind with the lipid proxy radicals, and they react with lipid proxy radicals faster than oils. Tocopherols play an important role in preventing oils from oxidation during processing and storage because they can stop radical chain reactions, especially for PUFAs (Rossi et al. 2007). α-, γ- and δ- Tocopherols were identified and quantified in hemp seed oils extracted from unroasted (Table 1) and roasted seeds (Fig. 1). The amounts of α-, γ-, δ- and total tocopherol contents of oil from unroasted hemp seed were 52.92, 707.47, 38.47 and 798.86 mg/kg oil, respectively. Teh and Birch (2013) reported that α- and γ- tocopherol contents of hemp seed oil were 28.8 and 564.1 mg/kg oil, respectively. The results obtained in this study for α- and γ- tocopherols were higher than the findings of Teh and Birch (2013). γ-Tocopherol was the major tocopherol isomer (88.56%) in samples. Similar ratio (90%) was accounted for Cannabis ruderale L. by Oomah et al (2002). High γ-tocopherol ratio is a unique characteristic for hemp seed oil among edible vegetable oils, and only argan oil has a comparable γ-tocopherol content (407.7 mg/kg, 87.09% of the total tocopherol), which both evaluated as high-price products (Matthaus 2013).

Fig. 1.

Changes in the tocopherol contents of the hemp seed oils during roasting process (a α-Tocopherol contents of roasted hemp seed oils; b γ-Tocopherol contents of roasted hemp seed oils; c δ-Tocopherol contents of roasted hemp seed oils; d Total tocopherol contents of roasted hemp seed oils)

Changes in tocopherol isomers and total tocopherol contents of hemp seed oils during roasting were shown in Fig. 1. Tocopherols in hemp seed oil significantly decreased with increasing the roasting time and temperature. For all tocopherol isomers and total tocopherol contents, the differences among roasting times and temperatures were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05). Samples roasted at higher temperatures showed higher tocopherol losses. The α-, γ-, δ- and total tocopherol losses ratio in samples roasted at 140, 160 and 180 °C were 9.67, 6.98, 14.91, 7.54%; 17.24, 11.39, 24.93, 12.43% and 33.23, 15.23, 35.22, 17.39%, respectively. High decreasing ratios for δ- and α- tocopherols were related to their low initial values. Major protective effect was provided by γ-tocopherol as dominant tocopherol isomer found in hemp seed oil (707.47 mg/kg oil). The decrease in tocopherols may be related to the decomposition of tocopherols at high temperatures during roasting, and also their consumption against oxidation. Tocopherol isomers showed different antioxidative activitiy in oils, followed the order of γ > δ > α > β (Tuberoso et al. 2007). Shrestha and Meulenaer (2014) reported decreases in γ-tocopherol contents of mustard and rapeseed after roasting at 180 °C, however no significant change was observed in α- tocopherol content of roasted samples.

Total phenolic contents and antioxidant activity values of hemp seed samples were shown in Table 3. Defatted matter of hemp seed was a rich source of phenolic compounds, and consequently showed high antioxidant activity (% inhibition). Teh et al. (2014) reported that the total phenolic content of hemp seed was 4323.3 mg GA eq/kg defatted sample, and its % inhibition level of DPPH radical was 5.33%. Our result for total phenolic content was lower than data reported by Teh et al. (2014). The total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of hemp seed were rised with increasing roasting time and temperature. Roasting at different times and temperatures significantly affected the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of hemp seed (p < 0.05). In addition, for both parameters, there was a significant interaction between roasting times and temperatures (p < 0.05). The increasing ratios of the total phenolic contents after roasting at 140, 160 and 180 °C were found to be 39.45, 95.70 and 160.07%, respectively. Antioxidan activity of hemp seed was also similarly affected by roasting. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of hemp seed samples increased from an initial value of 31.76 to 40.22, 52.22 and 60.60% inhibition after roasting at 140, 160 and 180 °C, respectively. Aktaş and Bakkalbaşı (2017) indicated that the increase in phenolic contents during heating might be due to the release of free phenolics from bound phenolics by the breakdown of cellular constituents and cell walls. Carciochi et al. (2016) reported that maillard reaction products, phenolic content and antioxidant activity in quinoa seeds were increased during roasting.

Table 3.

Changes in the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of the hemp seed during roasting process

| Minute | Total Phenolic Content (mg GA eq./kg defatted matter) | DPPH (% inhibition) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140 °C | 160 °C | 180 °C | 140 °C | 160 °C | 180 °C | |

| 0 | 1022.1 ± 0.0 | 1022.1 ± 0.0 | 1022.1 ± 0.0 | 31.76 ± 1.34 | 31.76 ± 1.34 | 31.76 ± 1.34 |

| 10 | 1114.1 ± 52.5Cd | 1131.2 ± 0.0Bd | 1186.7 ± 74.5Ad | 33.85 ± 6.01Cc | 33.27 ± 3.48Bc | 37.52 ± 0.19Ac |

| 20 | 1152.1 ± 141.7Cdc | 1410.7 ± 125.9Bdc | 1412.1 ± 346.8Ac | 34.11 ± 4.99Ccb | 34.54 ± 0.00Bcb | 43.28 ± 2.91Acb |

| 30 | 1182.8 ± 128.0Cc | 1471.4 ± 73.6Bc | 1620.4 ± 282.6Ac | 34.45 ± 3.81Ccb | 38.93 ± 0.86Bcb | 45.50 ± 2.66Acb |

| 40 | 1307.4 ± 271.9Cb | 1531.7 ± 161.3Bb | 2193.1 ± 458.9Ab | 35.13 ± 1.03Cb | 42.52 ± 4.69Bb | 48.25 ± 6.01Ab |

| 50 | 1404.4 ± 173.8Ca | 1799.1 ± 11.2Ba | 2642.1 ± 121.0Aa | 38.85 ± 5.75Ca | 46.15 ± 4.99Ba | 58.87 ± 7.42Aa |

| 60 | 1425.4 ± 10.2Ca | 2000.3 ± 187.6Ba | 2658.2 ± 104.6Aa | 40.22 ± 6.70Ca | 52.72 ± 7.14Ba | 60.60 ± 3.56Aa |

Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. Numbers followed by different superscript uppercase letters amongst the temperatures are significantly different (p < 0.05). Numbers followed by different superscript lowercase letters within the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Effect of roasting on some oxidation parameters of hemp seed oil

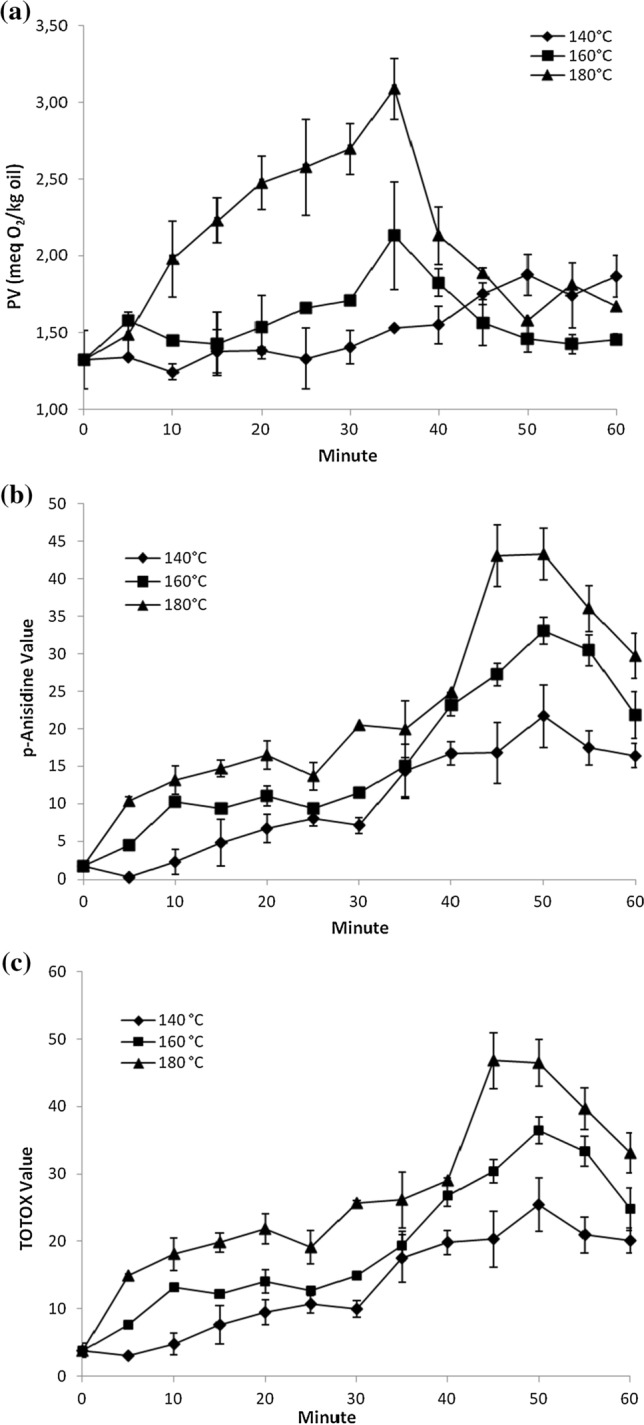

The effect of roasting on oxidation level of hemp seed oil was determined by measuring peroxide, p-anisidine and TOTOX values (Fig. 2). PV represents the concentration of peroxides and hydroperoxides (meq O2/kg oil) known as primary oxidation products formed in the initial stage of lipid oxidation. Changes in PVs of the hemp seed oil during roasting were presented in Fig. 2a. Increasing the roasting temperature and time significantly affected the PVs of samples (p < 0.01). The PV of samples roasted at 140 °C varied in a narrow range (1.33–1.55 meq O2/kg oil) up to 40 min roasting, then increased to 1.88 meq O2/kg oil at 50 min, following irregular change up to 60 min. After a slight increase at 5 min (1.58 meq O2/kg oil) the PV of samples roasted at 160 °C varied in a narrow range (1.58–1.71 meq O2/kg oil) up to 30 min roasting, followed increasing pattern up to 35 min (2.13 meq O2/kg oil) and then showed decreasing trend. In samples roasted at 180 °C, after a slight increased at 5 min (1.48 meq O2/kg oil) roasting, the PV of samples sharply increased up to 35 min (3.09 meq O2/kg oil). The PVs of all samples showed decreasing trend after reaching the highest values. Decreasing the hydroperoxides content of samples may be due to degradation of these compounds to secondary oxidation products at the later stage of roasting. The values obtained for PV were below the permissible limit of the international standards (10 meq O2/kg) for edible oils (Codex Alimentarius 2015).

Fig. 2.

Changes in the oxidative stability parameters of the hemp seed oils during roasting process (a PVs in oils of roasted hemp seeds; b AVs in oils of roasted hemp seeds; c Totox values in oils of roasted hemp seeds)

Reaction of unsaturated aldehydes with p-anisidine reagent gives products that show strong absorption at 350 nm. As a result, the AV is a good indicator for unsaturated aldehydes which are known as secondary oxidation products (Wai et al. 2009). The roasting at different temperatures and times significantly affected the AV of samples (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b). The initial AV of sample was 1.65. The AV of samples roasted at 140 °C, after a slight decrease at 5 min, showed increasing trend up to 50 min (21.68) following decreasing pattern up to 60 min. The AV of samples roasted at 160 °C increased up to 10 min, then irregularly changed in a narrow range up to 35 min (10.31–15.05) following increase up to 50 min (33.06), and finally decreased up to 60 min. Samples roasted at 180 °C showed higher AVs than its counterparts roasted at 140 and 160 °C at all sampling intervals. The AV of samples roasted at 180 °C increased up to 35 min (1.65–19.95), sharply increased up to 45 min (43.03) and dramatically decreased from 50 to 60 min. The results showed that at the early stage of roasting, primary (PV) and secondary (AV) oxidation products are simultaneously generated. In samples roasted at 140 °C, PV and AV formation (up to 50 min) and degradation (up to 60 min) occurred simultaneously at a narrow range. In samples roasted at 160 and 180 °C the PV reached to its highest level at 35 min. Interestingly, the decrease in PV after 35 min exposure to roasting accompanied with a sharp increase in AV of the samples (Fig. 2a, b). This was due to simultanously degradation of hydroperoxides to secondary oxidation products represented by AV. While PV varied in a narrow range in all samples (1.33–3.09 meq O2/kg oil), variation in AV ranged from 1.65 to 43.27. Guillen and Cabo (2002) reported that in some oils, such as olive and rapeseed, the generation of secondary oxidation products begins almost simultaneously with the generation of hydroperoxides, and in others, such as sunflower and safflower oils the degradation of hydroperoxides begins when the concentration of these compounds is appreciable.

The sum of AV and 2xPV is known as the total oxidation value (TOTOX) and this empiric parameter provides a better picture of the overall quality status of the oil (Wai et al. 2009). Changes in TOTOX values of the hemp seed oils during roasting were given in Fig. 2c. AVs in hemp seed oils were considerably higher than their PVs. Therefore, AV has major effect on calculation of TOTOX value. AVs and TOTOX values followed the same pattern during roasting in 140, 160 and 180 °C. The roasting temperature and time significantly affected the TOTOX values of samples (p < 0.05). According to the TOTOX limit (TOTOX = 20) mentioned in German Guidelines for Edible Fats and Oils (2011), roasting at 140 and 160 °C for 35 min, and roasting at 180 °C for 15 min can be recommended for roasting of hemp seed.

Kinetic of oxidation parameters during roasting process

Oxidation is a highly complex process because of the effects of various internal and external parameters. Oxidation is a mixed reaction that involves series and parallel reactions. The typical approach of processing by writing the rate law expressions for the elementary reaction steps cannot be used for simulation because it is almost impossible to monitor the concentrations of all the products, reactants and intermediate components separately (Özilgen and Özilgen 1990). In order to evaluate the oxidation reactions in roasted hemp seed samples, kinetic analysis was applied to PVs and AVs obtained during roasting. The orders and rate constants of the reactions for oxidation during roasting were given in Table 4. Results showed that the orders and rate constants of oxidation reactions were changed depending on the reaction temperature. Reaction rate constants rised with increasing temperature as expected. It is a common method to select a constant kinetic order for the entire oxidation reaction. Crapiste et al. (1999) declared that decomposition reactions in autocatalyzed lipid oxidation occurred according to second-order kinetics. However, in this study, the reaction order dramatically decreased from first-order to zero-order with increase the reaction temperature. Decreasing the reaction order implies that the reaction rate becomes independent from reactant concentration. In zero-order reaction, the reaction rate is controlled by the reaction rate constant. Baştürk et al (2007) noted that the orders of formation and decomposition reactions in oxidation of cottonseed, palm and soybean oils were changed from first-order to zero-order with increase the temperature. Our results were similar with findings reported by Baştürk et al (2007). In our study, reaction rate constants and orders of secondary oxidation products (AVs) were similar with those of primer oxidation products (PVs). It is an interesting result that has not been reported previously. In this study, secondary oxidation products in hemp seed oil generated almost simultaneously with the generation of hydroperoxides. Lipid peroxides acted as a limiting factor for formation of autocatalytic oxidation reactions. Therefore, the orders and rate constants of formation reactions of primary (PV) and secondary (AV) oxidation products were found to be similar.

Table 4.

The rate constants and reaction orders of primary and secondary reactions

| Roasting Temperature (°C) | α | k1 | β | k2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140 | 1.45 ± 0.07 | 0.32 ± 0.00 | 1.34 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.06 |

| 160 | 0.96 ± 0.29 | 1.38 ± 0.41 | 0.94 ± 0.29 | 1.39 ± 0.42 |

| 180 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 1.94 ± 0.21 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 1.92 ± 0.21 |

Conclusion

Results showed that hemp seed oil had high linoleic and α-linolenic acids, and low n-6/n3 ratio. Roasting did not affect the fatty acid composition of hemp seed oil. Hemp seed had high γ-tocopherol content, which corresponded to 88.56% of the total tocopherols. Tocopherol content of hemp seed oil was significantly reduced with increasing roasting time and temperature. Defatted matter of hemp seed was a good source of phenolic compounds and consequently had high antioxidant activity. Total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of hemp seed were increased after roasting process. PV, AV and TOTOX values of samples increased initially before reaching a maximum value and decreased at the later stage of roasting. Consequently, low temperature and short time roasting (140 and 160 °C for 35 min; 180 °C for 15 min) must be chosen providing good quality hemp seed. Based on its rich α-linolenic acid, γ-tocopherol, total phenolic contents and high oxidative stability (low PV and AV), under defined roasting conditions hemp seed can be evaluated as a healthy snack food.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Van Yüzüncü Yıl University Research Fund (Project No. FYL-2017-6411).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aktaş ZZ, Bakkalbaşı E. Influence of different cooking methods on color, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant activity of kale. Int J Food Prop. 2017;20(4):877–887. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2016.1188308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarus (2015) Codex Standard for Edible Fats and Oils Not Covered by Individual Standards. CODEX STAN 19-1981, Rev. 1989-1999 (Amended 2009, 2013, 2015) Codex Alimentarius, Rome, Italy

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis. Washington, DC: Association of official analytical chemists; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- AOCS (1992) p-Anisidine value (Official Method Cd 18–90). In: Official methods and recommended practices of the American oil chemists’ society (Additions and Revisions). AOCS press, Champaign, IL.

- AOCS (1993) Determation of tocopherols and tocotrienols in vegetable oils and fats by HPLC (Offical Method Ce 8–89). In: Official methods and recommended practices of the American oil chemists’ society, AOCS press, Champaign, IL.

- AOCS (1997) Peroxide value (Official Method Cd 8–53). In: Official methods and recommended practices of the American oil chemists’ society. AOCS press, Champaign, IL.

- Baştürk A, Javidipour I, Boyacı İH. Oxidative stability of natural and chemically interesterified cottonseed, palm and soybean oils. J Food Lipids. 2007;14:170–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4522.2007.00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway JC. Hempseed as a Nutritional Resource: An Overwiev. Euphytica. 2004;140:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s10681-004-4811-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cammerer B, Kroh LW. Shelf life of linseeds and peanuts in relation to roasting. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2009;42:545–549. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2008.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carciochi RA, Galv R, D’Alessandro LG, Manrique GD. Effect of roasting conditions on the antioxidant compounds of quinoa seeds. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2016;51:1018–1025. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, He J, Zhang J, Zhang H, Qian P, Hao J, Li L. Analytical characterization of hempseed (seed of Cannabis sativa L.) oil from eight regions in China. J Diet Suppl. 2010;7:117–129. doi: 10.3109/19390211003781669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crapiste GH, Brevedan MIV, Carelli AA. Oxidation of sunflower oil during storage. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1999;76:1437–1443. doi: 10.1007/s11746-999-0181-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deferne JL, Pate DW. Hemp seed oil: a source of valuable essential fatty acids. J Int Hemp Assoc. 1996;3:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Demir AD, Cornin K. Modelling the kinetics of textural changes in hazelnuts during roasting. Simul Model Pract Th. 2005;13:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.simpat.2003.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir AD, Celayeta JMF, Cronin K, Abodayeh K. Modelling of the kinetics of colour change in hazelnuts during air roasting. J Food Eng. 2002;55:283–292. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(02)00103-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- German Guidelines for Edible Fats and Oils (2011) Leitsätze für Speisefette und-öle vom 3. November 2011. (BAnz. Nr. 181 vom 01.12.2011, pp 4256).

- Gullien MD, Cabo N. Fourier transform infrared spectra data versus peroxide and anisidine values to determine oxidative stability of edible oils. Food Chem. 2002;77:503–510. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00371-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jannata B, Oveisib MR, Sadeghib N, Hajimahmoodib M, Behzadb M, Nahavandib B, Tehranib S, Sadeghic F, Oveisic M. Effect of roasting process on total phenolic compounds and γ-tocopherol contents of Iranian sesame seeds (Sesamum indicum) Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12(4):751–758. doi: 10.22037/IJPR.2013.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javidipour I, Erinç H, Baştürk A, Tekin A. Oxidative changes in hazelnut, olive, soybean, and sunflower oils during microwave heating. Int J Food Prop. 2017;20(7):1582–1592. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2016.1214963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Christen S, Shigenaga MK, Ames BN. γ-Tocopherol, the major form of vitamin E in the US diet, deserves more attention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:714–722. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal-Eldin A, Yanishlieva N. Kinetic analysis of lipid oxidation data. In: Kamal-Eldin A, Pokorny J, editors. Analysis of lipid oxidation. Champaign: AOCS Press; 2005. pp. 234–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kiralan M, Gül V, Kara M. Fatty acid composition of hempseed oils from different locations in Turkey. Span J Agric Res. 2010;8(2):385–390. doi: 10.5424/sjar/2010082-1220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesma G, Consonni R, Gambaro V, Remuzzi C, Roda G, Silvani A, Vece V, Viscont GL. Cannabinoid-free Cannabis sativa L. grown in the Po valley: evaluation of fatty acid profile, antioxidant capacity and metabolic content. Nat Prod Res. 2014;28(21):1801–1807. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.926354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lužaic T, Romanić R, Kravić S, Radić B. Formulation of sunflower and flaxseed oil blends rich in omega 3 fatty acids. Food Health Dis. 2018;7(1):18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Matthaus B. Quality Parameters for cold press edible Argan oils. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8(1):37–41. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1300800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oomah BD, Busson M, Godfrey DV, Drover JCG. Characteristics of hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) seed oil. Food Chem. 2002;76:33–43. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00245-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Özilgen S, Özilgen M. Kinetic model of lipid oxidation in foods. J Food Sci. 1990;55:498–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1990.tb06795.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paz SM, Marín-Aguilar F, García-Giménez MD, Fernández-Arche MA. Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seed oil: Analytical and phytochemical characterization of the unsaponifiable fraction. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:1105–1110. doi: 10.1021/jf404278q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic M, Debeljak Z, Kesic N, Dzidara P. Relationship between cannabinoids content and composition of fatty acids in hempseed oils. Food Chem. 2015;170:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porto CD, Decorti D, Natolino A. Potential oil yield, fatty acid composition, and oxidation stability of the hempseed oil from four Cannabis sativa L. cultivars. J Diet Suppl. 2015;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.3109/19390211.2014.887601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyo YH, Lee TC, Logendra L, Rosen RT. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of swiss chard (Beta vulgaris subspecies cycla) extracts. Food Chem. 2004;85:19–26. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00294-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Alamprese C, Ratti S. Tocopherols and tocotrienols as free radical-scavengers inrefined vegetable oils and their stability during deep-fat frying. Food Chem. 2007;102:812–817. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozanska MB, Kowalczewski PL, Tomaszewska-Gras J, Dwiecki K, Mildner-Szkudlarz S. Seed-roasting process affects oxidative stability of cold-pressed oils. Antioxidants. 2019;8(8):313. doi: 10.3390/antiox8080313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IUPAC . International union of pure and applied chemistry method No 2.301. In: Paquot C, editor. Standard methods for analysis of oils, fats and derivatives. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha K, Meulenaer BD. Effect of seed roasting on canolol, tocopherol, and phospholipid contents, maillard type reactions, and oxidative stability of mustard and rapeseed oils. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:5412–5419. doi: 10.1021/jf500549t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic phosphotungustic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Teh S, Birch J. Physicochemical and quality characteristics of cold pressed hemp, flax and canola seed oils. J Food Compos Anal. 2013;30:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2013.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teh SS, Bekhit AED, Birch J. Antioxidative polyphenols from defatted oilseed cakes: Effect of solvents. Antioxidants. 2014;3:67–80. doi: 10.3390/antiox3010067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuberoso CIG, Kowalczyk A, Sarritzu E, Cabras P. Determination of antioxidant compounds and antioxidant activity in commercial oilseeds for food use. Food Chem. 2007;103:1494–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wai TW, Saad B, Penglim B. Determination of totox value in palm oleins using a FI- potentiometric analyzer. Food Chem. 2009;113:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.06.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesundera C, Ceccato C, Fagan P, Shen Z. Seed roasting improves the oxidative stability of canola (B. napus) and mustard (B. juncea) seed oils. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2008;110:360–367. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200700214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]