Abstract

Introduction

Intensive care unit (ICU) visitation has traditionally been restrictive, primarily due to septic considerations and staff apprehension towards unrestricted visitation policy. However, ICU admission is stressful for patients and their families and the presence of family relatives at ICU patients’ bedside may help alleviate the same. The present study compares the viewpoints of healthcare workers (HCW) and patients’ family members regarding these two types of visitation policies.

Materials and methods

The initial assessment involved a qualitative investigation, based on an inductive grounded theory approach. Participant interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, manually coded, themes analyzed, and aggregate dimensions unfolded. Subsequently, a structured proforma filled by stakeholders and responses were coded as categorical variables (quantitative investigation). Their association with a continuous presence of family members was seen using univariate analysis (Chi-square test) and p <0.05 was considered significant. Satisfaction levels were rated on a Likert scale.

Results

Eighty-six stakeholders [group A: HCWs (15 doctors, 29 nurses), group B: patients (n = 18), and their relatives (n = 24)] were interviewed. While group A preferred restricted visitation policy (RVP), group B preferred unrestricted visitation policy (UVP). Quantitative data confirmed that HCWs (92.8% nurses and 85.7% doctors) were more satisfied with RVP and group B (92.3% relatives and 87.5% patients) with UVP. Group A (75.9% nurses and 93.3% doctors) therefore preferred RVP and group B (75% families and 66.6% patients) preferred UVP.

Conclusion

The patients and their families were more satisfied with UVP contrary to HCWs who were skeptical towards UVP and preferred RVP.

How to cite this article

Mahajan RK, Gupta S, Singh G, Mahajan R, Gautam PL. Continuous Family Access to the Intensive Care Unit: A Mixed Method Exploratory Study. Indian J Crit Care Med 2021;25(5):540–550.

Keywords: Intensive care unit, Mixed method, Visiting policy

Introduction

Intensive care unit (ICU) visiting policies have been a contentious issue. Patients and their families find ICU experience highly stressful, resulting in anxiety (65%) and depression (35%) amongst the relatives during admission. While the family access to ICU has traditionally been restrictive (restricted visitation policy—RVP) to avoid septic complications, patient-centered care involves designing a visitation policy to meet the needs of both patients and their families in addition to high standard therapeutic care. This may require an unrestricted or open visitation policy (UVP/OVP).

The present study assesses the acceptance of the UVP and RVP among the healthcare workers (HCWs—physicians, residents, nurses), patients, and their relatives in different ICUs of a tertiary care hospital in North India by a mixed methodology approach.

Materials and Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital with 12 ICUs having 160 beds. While eight ICUs (108 beds) of medical/surgical critical care units follow a UVP policy, four ICUs (52 beds) in the cardiac center follow RVP. In UVP, one visitor is allowed with the patient in ICU for 24 h, whereas in RVP, one visitor is allowed for 30 min twice a day.

Study Design

After institutional ethics approval (IEC Number 2019-405), the study was conducted prospectively between May and July 2019. A fixed mixed methods model was used and outlined using a typology-based approach with the purpose of triangulation, offset, and completeness. It was based on a convergent parallel design. The qualitative and quantitative strands were implemented concurrently, with equal priority but independent of each other, and data accrued were merged only during interpretation.1,2 With this design, divergent but complementary data could be obtained on the same topic.3

Data Collection

Qualitative Investigation

This was based on the inductive grounded theory approach, which involves moving back and forth between data collection and analysis until a theory that fits the data emerges.4 Theoretical sampling was done. Data obtained from the first participants determined which new participants were likely to provide the required information; hence, a sample size could not be determined beforehand. Data collection was stopped when themes were saturated.1,2 Four types of stakeholders were identified and divided into two groups: group A: included doctors and nurses dedicated to caring for the critically ill and group B: included unintubated patients and families of mechanically ventilated patients admitted for more than 48 h in ICU. Families were defined as first-degree relatives visiting the patient. For each member; age, gender, educational status, and relationship with the patient were recorded. To minimize bias, patients with active cardiac ailments were included. The data collection was done by a member of research team who had complete knowledge of the research project but was not directly involved in patient care (S). After informed consent, an interview (protocol in the supplement) consisting of semi-structured and open ended questions, was conducted (and audiotaped) in vernacular language (by S).5

Quantitative Investigation

Stakeholders were also given a structured proforma consisting of separate but related questions so that mixing quantitative with qualitative methods would help to improve a more basic design.2 This proforma was generated by three study team members (RKM, GS, RM). Duplicate items were excluded.

Analysis

The data were analyzed using a mixed method approach by Creswell and Plano Clark.9

Qualitative Analysis

The study began with cycles of data collection and analysis to identify interrelations among concepts, which were aggregated into an integrative theory, based on the grounded theory approach.

Once the stakeholders were interviewed, audio recordings underwent verbatim transcription and translation by a second investigator (RKM).9 Data was manually coded and analysis was done in three phases. Phase 1: Open coding: Initial participant responses were coded for emergent keywords and first-order concepts were generated. Phase 2: Axial coding: repetitive codes were merged and analyzed for themes. Phase 3: Selective coding: an aggregate dimension was unfolded.6 Data validation was done by intercoder agreement (RKM, RM).7

Quantitative Analysis of Structured Data

Satisfaction levels of participants were rated on the 5-point Likert scale (very dissatisfied, moderately dissatisfied, somewhat satisfied, moderately satisfied, very satisfied).8 Responses of stakeholders were coded as categorical variables and their association with main explanatory variable (continuous presence of family members) was seen. Responses were probed using univariate analysis by using the Chi-square test and p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

In view of a lesser number of extreme responses, the first two responses were clubbed as “not satisfied” and the last three as “satisfied”.

Results

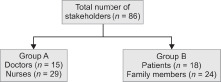

Eighty-six stakeholders including 15 doctors, 29 nurses, 24 family members, and 18 patients were interviewed. Respondents were divided into two groups (Flowchart 1). Group A comprised of HCWs (doctors and nurses) and group B of patients and their family members. Baseline characteristics of groups A and B are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Five aggregate dimensions emerged as a central concept around which all other themes and codes were arranged (Supplementary Table 1).

Flowchart.

Distribution of stakeholders into two groups

Table 1.

Number of stakeholders

| Number of stakeholders | Group I (UVP) | Group II (RVP) |

|---|---|---|

| Doctors (n = 15) | 8 | 7 |

| Nurses (n = 29) | 15 | 14 |

| Family members (n = 24) | 13 | 11 |

| Patients (n = 18) | 8 | 10 |

Tables 2A and B.

Baseline characteristics of stakeholders: (A) Group A: characteristics of HCWs; (B) Group B: characteristics of relatives and patients

| A: Group A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sl. No. | Variables | Doctors (n = 15) | Nurses (n = 29) |

| 1. | Age (years) mean ± SD | 42.7 ± 8.62 | 32.5 ± 8.09 |

| 2. | Number of females | 7 | 29 |

| 3. | ICU experience (years) mean | 12.31 | 7.41 |

| 4. | Mean number of working hours/week | 58 | 47.9 |

| 5. | HCW:patient ratio (average) | 1:11 | 1:2 |

| HCW, healthcare worker; SD, standard deviation | |||

| B: Group B | |||

| Sl. No. | Variables | Relatives (n = 24) | Patients (n = 18) |

| 1. | Type of patient admission | ||

| Elective | 8.3% | 16.6% | |

| Emergency | 91.6% | 83.3% | |

| 2. | Patient diagnosis | ||

| Trauma | 4.1% | 5.5% | |

| Medical | 37.4% | 55.5% | |

| Surgical | 58.3% | 38.8% | |

| 3. | Age (years) mean ± SD | 42.3 ± 16.3 | 56 ± 15.7 |

| 4. | Male:female | 1:1 | 2:1 |

SD, standard deviation

Supplementary Table 1.

Qualitative table

| Aggregate dimensions | Themes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Satisfaction of participants | Satisfaction of physicians and staff | UVP doctor 8: “UVP decreases doctor's responsibility and the treatment remains transparent” UVP nurse 15: “In restricted visitation, relatives may blame the staff in case the patient becomes suddenly ill” |

| Overall satisfaction of family and improved communication with family and patient | UVP doctor 1: “In UVP, multiple numbers of relatives may become violent, relatives can see whether appropriate treatment is being given or not” UVP doctor 4: “Patients need relatives for communication as they may not be able to express themselves” UVP doctor 6: “Sense of suspicion of anything undue being done in the ICU is not there if relatives are nearby” UVP doctor 8: “In UVP, attendants are in constant touch with the patient so they know patient's condition” UVP nurse 3: “In UVP, relatives know the change in status” UVP nurse 4: “In UVP, relatives are satisfied that the treatment is given” UVP nurse 5: “In UVP, relatives can meet the doctor and know the progress of the patient, they can see patient's progress or deterioration” UVP nurse 6: “In UVP, relatives can see that the treatment is being given” UVP nurse 7: “In UVP, relatives rest assured that the treatment is given to the patient” UVP nurse 8: “In UVP, attendants see that the care being given” UVP nurse 10: “In UVP, patients condition is known whether improving or worsening” UVP nurse 11: “In UVP, relatives are aware of the ongoing treatment, medicines given and procedures done on their patients” UVP nurse 12: “In UVP, relatives know about the condition of the patient, can see whether medication is given or not and are kept informed about patient's condition” UVP nurse 13: “In UVP, attendants know what treatment is being given or procedure done” UVP nurse 14: “In RVP, relatives may not trust the staff” UVP, nurse 15: “In UVP, relatives help in the communication of patient with the staff. In RVP, there is a lack of trust in the staff and the relatives may blame the staff if the patient becomes sick” RVP nurse 5: “Patients do not feel homesick when relatives are around” UVP family 1: “In UVP, there is emotional support to the patients and their family, else the patients will get bored” UVP family 2: “In UVP, we come to know the condition of the patient and we can talk to the doctors, we are satisfied that our patient is been taken care of. In RVP, we won't know if medicines have been given to our patient or not” UVP family 3: “In UVP, we are satisfied that we are with our patient in this difficult time, we can see that our medicines are being used on our patient and our patient is being taken care of” UVP family 4: “In UVP, we come to know regarding the improvement of our patient” UVP family 5: “In UVP, we are satisfied that treatment is continued and medicines are being given” UVP family 6: “In UVP, we are satisfied that they are taking care of the patient. We can come to know our patient's condition and can explain it to the rest of the family” UVP family 7: “We are satisfied that we are taking care of our loved one, we come to know our patient's condition” UVP family 8: “In UVP, increases satisfaction of the patient and family, we are kept updated about our patient's condition” UVP family 9: “We are kept updated about patient's condition” UVP family 10: “In UVP, emotional satisfaction and hope for the family is more, we are satisfied that medicines are being given” UVP family 11: “In UVP, we can see that the treatment is going on, that our patient is getting better or worse. We are satisfied that our medicines are being used on our patients. In RVP, we won't know the condition of our patient” UVP family 12: “We can take care of our patients” UVP family 13: “We can take care of our patients. In RVP, we won't know the condition of our patient” RVP family 3: “In RVP, family apprehension is always there” RVP family 6: “We stay updated about patient's status” RVP patient 4: “In UVP, family will be more satisfied” RVP patient 5: “In UVP, family will be more satisfied” |

|

| Overall satisfaction of patient | UVP doctor 7: “In UVP, there is good emotional support to the patient” UV doctor 8: “In UVP, patients will be less anxious if relatives are nearby” RVP doctor 1: “Relatives provide moral support to the patient” UVP, nurse 5: “Patients agree to what the family members say, better than the strangers” RVP nurse 2: “In RVP, patients may feel lonely” RVP nurse 4: “Relatives increase psychological support of the patients” RVP nurse 5: “Patients don't feel homesick” RVP nurse 8: “Patients are more comfortable with the family members” UVP family 2: “Patients do not feel alone” UVP family 6: “In UVP, patients are less anxious as relatives are nearby. Relatives improve the willpower of the patient” UVP family 7: “Relatives increase the moral support of the patients” UVP family 8: “Relatives increase the moral support of the patients” UVP family 10: “Relatives increase the moral support of the patients” UVP family 12: “Family provides emotional support to the patients” RVP family 4: “Family members provide emotional support to the patient. In RVP, there is no moral support for the patient” RVP family 5: “Family members can fulfill patient's requirements, patient's stress will be less” RVP family 6: “Family provides emotional support to the patient” RVP family 7: “Family provides emotional support to the patient” RVP family 8: “Family provides moral support to the patient” UVP patient 1: “Family offers moral support to the and we feel better” UVP patient 2: “Family offers psychological support and we feel better” UVP patient 5: “Relatives can fulfill our small needs” UVP patient 6: “Family provides us moral support. In RVP, patients may feel scared” RVP patient 7: “In RVP, we can share our problems and we have moral support” RVP patient 4: “In RVP, there is no emotional support for the patient” RVP patient 6: “In RVP, patients feel lonely” |

|

| 2. Sharing of staff workload | Provision of basic care | RVP doctor 3: “In UVP, relatives can help nursing staff, chances of ICU psychosis will be less with relatives around” RVP doctor 6: “In RVP, relatives can take care of the patients in psychosis” UVP nurse 3: “Relatives help in changing position in heavy patients” UVP nurse 6: “In UVP, relatives encourage patients for physiotherapy” UVP nurse 7: “In UVP, relatives can take care of their patient if the nurse is UVP nurse 8: In case of prolonged stays, relatives learn to do suctioning and administer NG feeds in preparation for home care. UVP nurse 14: “In UVP, relatives take care of the patient if the busy with the other sick patient” RVP nurse 3: “Relatives can help in caring” RVP family 5: “Nurses’ workload will be less” UVP patient 3: “Relatives can take care of the patient” RVP patient 9: “Relatives can feed the patient” |

| Relatives help with patient monitoring | UVP doctor 3: “They make you aware of small changes in patient status like ventilator disconnections” RVP doctor 3: “Relatives can monitor the patient” UVP nurse 7: “In UVP, they inform small changes in patient status” UVP nurse 12: “Relatives help in monitoring the patients” RVP nurse 1: “Relatives help in monitoring” RVP nurse 3: “Relatives can prevent injury and fall” UVP family 5: “In UVP, we can monitor the patient and inform subtle changes” |

|

| As a restraint alternative | UVP doctor 6: “Presence of family member reduces the need for pharmacological sedation and analgesia during weaning from mechanical ventilation” RVP doctor 1: “Relatives can hold violent patients”UVP nurse 2: “Relatives can hold the patients” UVP nurse 3: “Relatives help to hold the patients” UVP nurse 5: “Relatives can hold a violent patient and prevent patient injury” UVP nurse 8: “Relatives help to hold restless patients” UVP nurse 9: “In UVP, attendants hold the restless patients and prevent the patient from injury” UVP nurse 14: “Relatives help in holding violent patients” RVP nurse 3: “Relatives prevent injury or fall. In RVP, it is difficult for staff to manage the patients in psychosis alone” RVP nurse 10: “Relatives hold the patients in psychosis” |

|

| Physical help | UVP doctor 3: Relatives help in bringing medication UVP nurse 1: “Relatives can be of great help in bringing the medication in case of an emergency” UVP nurse 2: “Relatives can be of great help in bringing the medication in case of an emergency” UVP nurse 7: “Restricted visitation requires more manpower and 1:1 nursing ratio” UVP nurse 9: “Restricted visitation requires more manpower and 1:1 nursing ratio” UVP patient 4: “Relatives can bring medication” |

|

| 3. Outcome for patient recovery | Risk of infections | UVP doctor 1: “In UVP, multiple numbers of relatives increases the risk of infections” UVP doctor 2: “In UVP, there is a higher risk of infections” UVP doctor 3: “In UVP, higher risk of infections with multiple numbers of relatives” UVP doctor 4: “In UVP, there may be higher risk of infections” UVP doctor 7: “ICU with RVP may have fewer infections”. RVP doctor1: “Presence of relatives in ICU increases the incidence of infections” RVP doctor 2: “In RVP, there are fewer chances of infections” RVP doctor 5: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” UVP nurse 1: “Presence of relatives increases the risk of infections” UVP nurse 3: “There are increased chances of infections with UVP” UVP nurse 4: “Unrestricted visitation leads to a higher rate of infections which prolong ICU stay and increases the cost of treatment” UVP nurse 5: “There is increased risk of infections with UVP and hence increased cost of treatment, we can concentrate more on work in RVP” UVP nurse 9: “Relatives can increase the risk of infections” UVP nurse 10: “Relatives increase the risk of infections” UVP nurse 12: “UVP increases infection rates” UVP nurse 13: “There is increased risk of infections with UVP” UVP nurse 15: “Presence of relatives increases infection rates” RVP nurse 4: “In RVP, there is better infection control” RVP nurse5: In RVP, there are lesser chances of infection” RVP nurse 8: “In RVP, there are fewer chances of infections” RVP nurse 9: “In RVP, there are fewer chances of infection” RVP nurse 11: “Restricted visitation leads to lesser chances of infection” RVP nurse 14: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” UVP family 3: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” UVP family 4: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” UVP family 5: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” RVP family 4: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” RVP family 6: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” RVP family7: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” RVP family 8: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” RVP family 11: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” RVP patient 4: “In UVP, there are increased chances of infections” |

| Disorganization of essential treatment and care | UVP doctor 3: “In UVP, relatives tend to interfere with our prescribed treatment. And counseling has to be done multiple numbers of times.” In RVP, “working will be more regulated” RVP doctor 2: “In RVP, working is not hampered” RVP doctor 5: “In UVP, relatives ask unnecessary questions and disturb patient management”RVP doctor6: “Discussions in medical terminology may be misinterpreted by the relatives” RVP nurse 9: “If relatives are around, staff has to answer multiple questions, which interrupt care” UVP nurse 1: “Increased time and effort is spent in regulating the relatives, relatives interfere with treatment and nursing care” UVP nurse 2: “In UVP, relatives interfere with nursing care. In restricted visitation, work is more regulated” UVP nurse 3: “Relatives interfere with treatment and care and we have to explain the condition repeatedly” UVP nurse 5: “Relatives interfere with treatment and care” UVP nurse 6: “Multiple relatives ask same questions” UVP nurse 7: “Multiple relatives ask same questions and interfere with care” UVP nurse 9: “Relatives hinder in the treatment by asking same questions” UVP nurse 10: “Relatives disturb the staff by asking same questions again and again and interfere with care” UVP nurse 12: “Relatives interrupt during care” UVP nurse 14: “Relatives interfere with care” RVP nurse 2: “Relatives interfere with our work” RVP nurse 3: “In RVP, there is no interference in treatment and staff can concentrate on their work” RVP nurse 4: “Relatives interfere with treatment” RVP nurse 9: “Multiple relatives come and ask the same questions and we have to answer” RVP nurse 10: “Relatives interrupt in our work” RVP nurse 11: “Relatives interfere with prescribed treatment” RVP nurse 12: “Nurses can properly devote time to patient care if relatives are not around” RVP nurse 13: “Relatives interfere with our work” RVP nurse 14: “Relatives interrupt care, multiple relatives ask same questions” RVP patient 2: “Relatives disturb the staff” RVP patient 8: “Relatives interfere with nurses and doctor's work” |

|

| Patient rest opportunities | RVP doctor 2: “In RVP, patients can take rest properly” UVP nurse 9: “Relatives disturb the patient and do not allow them to rest” UVP nurse 10: “Relatives disturb the patients” RVP nurse 4: “In RVP, there is better patient rest” RVP nurse 5: “Relatives do not get proper rest” RVP nurse 7: “In UVP, there is inadequate patient rest” RVP nurse 12: “In UVP, there is decreased patient rest” RVP doctor 3: “Patients can take rest properly in unrestricted visitation” UVP doctor 3: “Patients will be more comfortable without the relatives” UVP family 1: “Multiple relatives will disturb the patient” UVP family 3: “In UVP, patients get disturbed” RVP family 11: “In UVP, patient is disturbed” RVP patient 3: “In RVP, patients get adequate rest” RVP patient 10: “In UVP, there is increased disturbance to the patient” |

|

| Improved care | UVP doctor 7: “In UVP, patient care is better as the staff remains on their toes” RVP family 8: “In UVP, there is faster patient recovery” |

|

| 4. ICU decorum | ICU decorum | UVP doctor 2: In UVP, “patient confidentiality is hampered” UVP doctor 6: In UVP, “in case of a mishap, agitation of one attendant may influence the other attendants” UVP doctor 7: “In case a medical error occurs, patients relatives will know and get agitated” UVP doctor 7: “Relatives take pictures of the records and confidential things can leak out” RVP doctor 1: “Relatives create chaos in the unit” UVP nurse 1: “Relatives keep checking files and argue with staff” UVP nurse 2: “Relatives keep checking reports and files and argue with staff” UVP nurse 4: “In UVP, there are more chances of increased violence and agitation among the relatives” UVP nurse 5: “Frustrated relatives may become violent” UVP nurse 12: “Relatives increase the noise in the unit, relatives can create panic in the unit” UVP nurse 13: “In RVP, working environment would be calm” UVP nurse 14: “Relatives keep looking at other beds” UVP nurse 15: “There may be increased violence and agitation among the family” RVP nurse 8: “Privacy of the patient is maintained in unrestricted visitation” RVP nurse 9: “Nurses cannot give personal care in front of family members” UVP family 5: “In UVP, one attendant is influenced by other attendants” RVP patient 3: “Presence of relatives increases crowding of the unit” RVP patient 5: “Presence of relatives increases crowding in the unit” RVP patient 8: “Presence of relatives increases crowding in the unit” |

| 5. Stress levels of stakeholders | Stress levels of HCWs, family members, and patients | UVP doctor 2: “In UVP, bedside discussions might be misinterpreted” UVP doctor 8: “In UVP. there is increased work pressure on staff and doctors and increased violence” RVP, doctor 2: “Relatives are anxious and stressed as they felt out of touch with their patient” RVP doctor 6: “In RVP, relatives panic even on minor fluctuations in vitals” RVP nurse 8: “In RVP, relatives do not have to suffer” RVP nurse 9: “In UVP, staff may hesitate to work in front of relatives. In RVP, attendants may not have sufficient time to stay and can go home” RVP nurse 13: “Relatives panic on seeing sick patients. The presence of relatives increases the stress of patients” RVP, patient 1: “Relatives are free to do their work” RVP family 2: “Restricted visitations cause less stress to the patient” RVP family 4: “The family members have to leave work and come so in RVP, there is less disturbance to the family” RVP patient 1: “In UVP, sitting by my side will waste their time, In RVP, they are free to do their work” RVP patient 2: “In RVP, family is free to do their work” RVP patient 4: “Family's routine gets disrupted” |

These include:

1. Satisfaction of the participants

Group A

Qualitative assessment: HCWs were more content with RVP than UVP. They felt that in UVP, relatives tend to interfere with treatment and disturb the staff by asking multiple questions thus interrupting work rounds and care. The staff has to spend increased time and effort to reconcile the relatives. However, a few HCWs deciphered that UVP ensures treatment transparency and reduces the why and wherefore of the treatment.

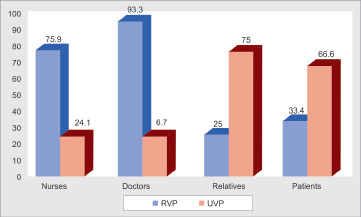

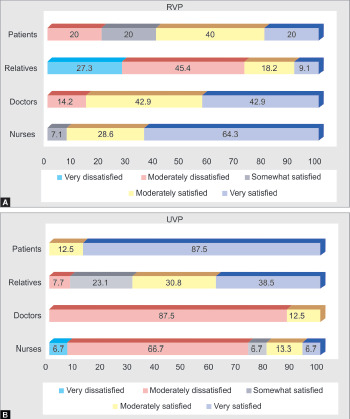

Quantitative assessment: The majority of participants (86%) in group A [75.9% nurses (p = 0.038) and 93.3% doctors (p = 0.33)] preferred RVP over UVP (Fig. 1) as they (86.2% nurses and 86.7% doctors) felt that they have to keep giving information to relatives in unrestricted visitation, which increases the time spent on a patient and affects routine management. Significantly greater number of HCWs (92.8% nurses and 85.7% doctors) following RVP (Fig. 2a) and only 26.7% of nurses and 12.5% of doctors following UVP (Fig. 2b) were satisfied with their current visitation policies (p-value for nurses and doctors were 0.0004 and 0.005, respectively). Most of the group A participants (75% doctors and 66.7% nurses) following UVP wanted to change to alternate policy (Fig. 3a) as compared to only a few HCWs [16.7% doctors (p = 0.002) and 7.14% nurses (p = 0.001)] following RVP (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 1.

Visitation policy preferred by the stakeholders

Figs 2A and B.

Satisfaction of the stakeholds (A) RVP, (B) UVP

Figs 3A and B.

Inclination of the stakeholders to change to alternate policy (A) UVP, (B) RVP

Group B

Qualitative assessment: The participants felt that UVP increases their overall and emotional satisfaction. Being close to their patient, relatives could assess the quality of diagnostic and therapeutic care being provided to the patient. Also, they felt satisfied being by the side of their loved ones in difficult times. Patients said that they get moral and emotional support and encouragement from their families and that the relatives help to improve their communication with staff.

Quantitative assessment: Seventy-five percent of families (p = 0.033) and 66.6% of patients (p = 0.009) preferred UVP (Fig. 1). Group B participants (92.3% relatives and 87.5% patients) who were admitted to ICUs following UVP were more satisfied with their current policy (Fig. 2b) contrary to only 27.3% of families (p = 0.001) and 20% of patients (p = 0.004) in ICUs with RVP (Fig. 2a). Around 73% of relatives and 60% of patients in RVP (Fig. 3b) wanted to change to alternative policy when compared with 15.4% of relatives (p = 0.004) and 12.5% of patients (p = 0.04) in UVP (Fig. 3a).

2. Sharing of staff workload

Group A

Qualitative assessment: Nurses discerned that patient's relatives participate actively in providing patient care, bringing medication in case of an emergency, holding violent and agitated patients, and orientating patients thus reducing the risk of ICU psychosis. Relatives’ interaction with patients by talking and touching increases their willpower and reduces sedation requirement during weaning. Doctors felt that relatives can be of great help in monitoring the patients in ICUs with a low nurse:patient ratio. RVP on the other hand increases nurses’ responsibilities.

Quantitative assessment: About 68.9% of nurses and 53.3% of doctors felt that the presence of a family member at the bedside is beneficial for the patient.

Group B

Qualitative assessment: The participants felt that the family can reduce the nurses’ workload by helping the staff with patient care and also getting the medication quickly in case of an emergency.

Quantitative assessment: About 70.8% of relatives and 66.6% of patients believed that the presence of family is beneficial for the patients.

3. Outcome for patient recovery

Group A

Qualitative assessment: The participants felt that in UVP, there is an increased risk of hospital-acquired infection to patients as relatives are unaware of the significance of hand hygiene. HCWs also observed increased disruption of treatment and care with UVP as they have to repeatedly answer the questions of continually changing relatives. The relatives being idle may unreasonably use their mobile phones, which might disturb the patient. Nurses also observed that the patients are unable to take adequate rest when one relative is always around.

Quantitative assessment: Most of HCWs (86.7% doctors and 96.6% nurses) thought that unrestricted visitation increased infections.

Group B

Qualitative assessment: The family members too were concerned about the increased risk of infection with UVP. Sometimes they may be sick and fear transmitting or catching an infection from the critically ill patients in ICU. In restricted visitation, patients felt that they can take adequate rest and when awake, they develop a better rapport with the staff which may lead to improved outcomes.

Quantitative assessment: As the relatives fear the increased risk of infections, 95.8% of family members said that they always try to maintain their hand hygiene.

4. ICU decorum

Group A: HCWs felt that relatives increase the noise in the unit and take up space. UVP hampers professional confidentiality, affects patient autonomy, increases chaos in the unit, and may lead to a higher incidence of violence as one agitated attendant may influence all others present. Some of the relatives annoyingly keep clicking pictures of patient documents and treatment charts or peeking into other patient's details thus affecting patient privacy.

Group B: Patients and relatives too felt that restricted visitation avoids crowding in the unit and preserves proper ICU functioning.

5. Stress levels of stakeholders

Group A

Qualitative assessment: In unrestricted visitation, the relatives are constantly listening to and possibly misinterpreting discussions at bedside rounds. There is constant pressure on the staff that might affect their performance. Although patients might be content having their family members around, HCWs believed that staying in ICU is stressful for the relatives as they panic about even minor fluctuations in vitals.

Quantitative assessment: Nurses (75.9%) felt an increased psychological burden due to the presence of stressed families. As per 60% of doctors, the continuous presence of relatives in UVP hampers bedside teaching. Many (60%) could feel the stress of constantly working under watchful eyes and 86.7% did feel the need to modify their way of communication with each other in ICU if relatives were around.

Group B

Qualitative assessment: Some relatives felt that RVP increases anxiety as they are unable to meet their loved ones and know what's going on with the patient. Contrarily, some believed they could be stress-free in RVP and could continue their work without disruption in their daily routine.

Quantitative assessment: The majority of patients (83.3%) felt that the presence of a relative nearby would decrease their stress and anxiety (p = 0.028). Only a few family members (54%) felt that always staying in ICU with patients disrupted their routine (p = 0.062).

We also enquired about stakeholder's opinions regarding the presence of family during physician rounds, physician and nursing procedures, and emergencies (Table 3). Whereas the HCWs were equivocal, family members strongly felt that they should be allowed during doctor's rounds so that they can communicate better with doctors. Nurses invincibly felt that family should be present in case of an emergency, mainly due to fact that they should be updated regarding the patient's condition, and also they might serve as an additional help to get medications if required.

Table 3.

Opinion of stakeholders regarding family presence during rounds, procedures, and emergencies

| Nurses (n = 29) | Doctors (n = 15) | Family (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician rounds | |||

| Yes | 15 (51.7%) | 7 (46.6%) | 19 (79.1%) |

| No | 14 (48.2%) | 8 (53.3%) | 5 (20.8%) |

| Physician procedure | |||

| Yes | 2 (6.8%) | 2 (13.3%) | 12 (50%) |

| No | 27 (93.1%) | 13 (86.6%) | 12 (50%) |

| Nursing procedures | |||

| Yes | 2 (6.8%) | 3 (20%) | 14 (58.3%) |

| No | 27 (93.1%) | 12 (80%) | 10 (41.6%) |

| Emergencies | |||

| Yes | 19 (65.5%) | 4 (26.2%) | 14 (58.3%) |

| No | 10 (34.3%) | 11 (73.3%) | 10 (41.6%) |

Discussion

We found that group A participants were more satisfied with RVP contrary to group B participants who preferred UVP. Although all the stakeholders acknowledged that relatives may be of help in decreasing staff workload, they were also concerned about the increased risk of infection with UVP. Contrary to group B, group A said that the continuous presence of relatives increased their stress as well as interfered with their work.

This study has many interesting aspects. This is the first study that we know of which has evaluated physicians’, nurses’, relatives’, and patient's perceptions of two types of ICU visiting policies in the same hospital and that too with a mixed methodology approach. Second, the overall duration of visits in UVP in our ICUs was much longer than in the previous reports.14,15

We found that HCWs were more satisfied with RVP. In a study on the attitude of ICU nurses towards open visitation, 75.3% of nurses had skeptical beliefs towards open visitation in their ICUs and only 15.1% of nurses felt that visitation benefits caregivers.9 The nurses are generally less satisfied with OVP and the majority of them report that family members interrupt care, without being of much help themselves.10–13 Contrarily, some studies have also suggested improved satisfaction among ICU professionals with flexible visiting hours.14 Even a few of our physicians reflected that they do not have to justify that the patient is being taken care of and this might help in avoiding unnecessary litigation on doctors. The presence of family during times of emergency may help them to understand that every possible treatment has been implemented. Studies have shown that open access to visitors increases the family's confidence in and appreciation of HCWs taking care of their loved ones and leads to improved patient and family anxiety and satisfaction.10–12,15–17 Participants discerned that presence of family facilitates staff communication with patients and families. Relatives regularly know the condition of their patients from time to time and as a family can understand their loved ones better, patient communication also improves.9,10 Family engagement and empowerment have been shown to reduce the risk of ICU delirium also.11,16 One study which did not report better family satisfaction with OVP was probably because their physicians did not have time for regular family discussions.15

UVP has a dual effect on nurses’ workload. Relatives can help nurses by assisting in patient monitoring, serving as restraint alternatives, providing patient care (especially in uncooperative patients), and physical help (changing positions in obese patients, bringing medication in case of an emergency). On the other hand, their continuous presence also leads to an increase in time spent by nurses in answering family's questions. This is in consensus with previous studies in which nurses did feel that OVP causes nurses to spend more time providing information to relatives.9,10 RVP also increases staff workload. Our ICUs have a 1:2 nurse:patient ratio, so if a nurse has one sick patient, she might find it difficult to attend to every need of the other patient. Hence, ICUs practicing RVP should have a 1:1 nursing ratio.

The majority of stakeholders (irrespective of their visitation policy) believed that UVP exposes patients to increased risk of infections. This alibi has been the major cornerstone of restricted visitation models. However, this theoretical risk has not been consistently confirmed in the literature.11,13,15

In our study, HCWs perceived an increase in disorganization of treatment and care with UVP. Literature has mixed results for the same. Some studies concurred with this10,13 while others did not.18,22 This difference is probably explained by the difference in the overall duration of visit, which was much longer in our ICUs with UVP as compared to these previous reports. The presence of a family member in case of an emergency or when physicians are doing procedures has not shown to have any adverse outcomes.18

Our participants felt that patients admitted in ICUs following UVP were unable to take proper rest. Literature is ambiguous regarding this. A few studies disagreed9,19 while others agreed that UVP decreases patient rest opportunities.20 UVP also increases chaos and confusion in ICU and the same has been suggested in previous studies.9

Our HCWs also recognized increased levels of stress by the continuous presence of relatives. Doctors felt awkward discussing and examining patients as well as teaching by the bedside when relatives are around as they can misinterpret the discussions. Literature is inconsistent regarding stress levels of HCWs in UVP; a few reporting decreases while in others staff did feel uncomfortable and had to change their work attitude when due family members were around.13 The concern of fragmented information from multiple sources being misunderstood has already been addressed in previous studies where authors had suggested limiting long discussions by patient's bedside.21 Unrestricted visitation also causes emotional involvement of nurses thus increasing their stress and strain.10 Quite a few studies reported increased incidence of burnout syndrome after flexible hours were introduced in ICU.11,22

We found that families of patients admitted in ICUs were always stressed irrespective of the visitation policy. In UVP, the probable reason was exhaustion and in RVP, relatives felt they were not continuously updated about the patient's condition. Research has noted the increased concern of visitor fatigue and exhaustion with UVP.23,24 However in some studies, the 24-r policy had decreased stress and anxiety but the families came for 1–2 s per day and did not congregate in large numbers in patient's room.12,15

In our study, patients had decreased stress in both UVP and RVP. Whereas some patients felt emotionally strong with family members being nearby, others felt that the continuous presence of family members is not required as it disrupts the entire family's routine and also decreases their rest time. But the majority of patients would prefer OVP. Unrestricted visitation has been seen to have conflicting effects on patient stress. Whereas family members relieve stress by providing emotional support for patients, their presence also decreases patient rest opportunities and hampers their privacy. Literature has shown that open visiting policies are preferred by patients as they help mitigate their stress.15,25

Limitations

We used manual coding instead of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) as we felt that coding with the hand would provide a more flexible approach in identifying and classifying the subject matter. Moreover, trying to learn the basics of coding and qualitative data analysis in software would have been overwhelming as well as time-consuming.

Conclusion

The HCWs were more satisfied with RVP and would prefer the same. They felt that the continuous presence of a relative interferes with their work and hence they were reluctant to change to the alternative policy. This is contrary to the patients and their relatives who preferred UVP as they were more satisfied being close to their loved ones.

Orcid

Rubina K Mahajan https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9933-5342

Suvidha Gupta https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7766-6941

Gagandeep Singh https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6661-3553

Ramit Mahajan https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6726-6151

Parshotam L Gautam https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7615-4781

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2011. Choosing a mixed methods design. In: Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. pp. 54–106. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoonenboom J, Johnson RB. How to construct a mixed methods research design. Köln Z Sozio. 2011;69(2):107–131. doi: 10.1007/s11577-017-0454-1. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann ML, Hanson WE. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2008. An expanded typology for classifying mixed methods research into designs. In: The Mixed Methods Reader. pp. 159–196. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charmaz K. “Discovering” chronic illness: using grounded theory. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(11):1161–1172. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90256-R. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creswell JW. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2003. Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair E. A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. J Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences. 2015 Jan 19;6(1):14–29. doi: 10.2458/jmm.v6i1.18772. DOI: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurasaki KS. Intercoder reliability for validating conclusions drawn from open-ended interview data: field methods [Internet]. [[cited 2020 Mar 11];];https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1525822X0001200301 2016 Jul 24; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan GM, Artino AR. Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):541–542. doi: 10.4300/JGME-5-4-18. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berti D, Ferdinande P, Moons P. Beliefs and attitudes of intensive care nurses toward visits and open visiting policy. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(6):1060–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0599-x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitton S, Pittiglio LI. Critical care open visiting hours. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2011;34(4):361–366. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e31822c9ab1. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nassar Junior AP, Besen BAMP, Robinson CC, Falavigna M, Teixeira C, Rosa RG. Flexible versus restrictive visiting policies in ICUs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(7):1175–1180. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003155. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Philippart F, Timsit JF, Diaw F, Willems V, Tabah A, et al. Perceptions of a 24-hour visiting policy in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(1):30–35. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000295310.29099.F8. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Silva Ramos FJ, Fumis RRL, Azevedo LCP, Schettino G. Perceptions of an open visitation policy by intensive care unit workers. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3(1):34. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-3-34. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozub E, Scheler S, Necoechea G, O'Byrne N. Improving nurse satisfaction with open visitation in an adult intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2017;40(2):144–154. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000151. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fumagalli S, Calvani S, Gironi E, Roberts A, Gabbai D, Fracchia S, et al. An unrestricted visitation policy reduces patients’ and relatives’ stress levels in intensive care units. [[cited 2019 Sep 8];];https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/34/suppl_1/P5126/2863041. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2013 Aug 1;34(suppl_1) doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht310.P5126. P5126. Available from: DOI: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh SJ, Ely EW, Gong MN. Can intensive care unit delirium be prevented and reduced? Lessons learned and future directions. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(6):648–656. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-232FR. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter JD, Goddard C, Rothwell M, Ketharaju S, Cooper H. A survey of intensive care unit visiting policies in the United Kingdom. Anaesthesi. 65(11):1101–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06506.x. 201v; DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beesley SJ, Hopkins RO, Francis L, Chapman D, Johnson J, Johnson N, et al. Let them in: family presence during intensive care unit procedures. Ann Am Thorac So. 2016;13(7):1155–1159. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-754OI. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marco L, Bermejillo I, Garayalde N, Sarrate I, Margall MA, Asiain MC. Intensive care nurses’ beliefs and attitudes towards the effect of open visiting on patients, family and nurses. Nurs Crit Care. 2006;11(1):33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2006.00148.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halm MA, Titler MG. Appropriateness of critical care visitation: perceptions of patients, families, nurses, and physicians. J Nurs Qual Assur. 1990;5(1):25–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riccioni L, Ajmone-Cat CA, Rogante S, Ranaldi G, Ciarlone A. New roles for health-care workers in the open ICU. Trends Anaestd Cril Care. 2014;4(6):182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tacc.2014.08.003. DOI: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giannini A, Miccinesi G, Prandi E, Buzzoni C, Borreani C ODIN Study Group. Partial liberalization of visiting policies and ICU staff: a before-and-after study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(12):2180–2187. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3087-5. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart A, Hardin SR, Townsend AP, Ramsey S, Mahrle-Henson A. Critical care visitation: nurse and family preference. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2013;32(6):289–299. doi: 10.1097/01.DCC.0000434515.58265.7d. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berwick DM, Kotagal M. Restricted visiting hours in ICUs: time to change. JAMA. 2004;292(6):736–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.736. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khaleghparast S, Joolaee S, Ghanbari B, Maleki M, Peyrovi H, Bahrani N. A review of visiting policies in intensive care units. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(6):267–276. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p267. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]