There is a major debate regarding the function of the thalamus: does the thalamus solely gate the transmission of information or is it actively involved in processing information? Sherman and Guillery (2006) argued that thalamic nuclei function as bidirectional relays for the flow of information between cortical and subcortical areas, with their neural activity being shaped by a convergence of “driving” and “modulatory” inputs. Driving inputs, in this framework, are those that “contain the main information to be conveyed to the cortex” (Sherman and Guillery, 2006). A classic example of driving input is the retinal input to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus. In contrast, modulatory inputs to the LGN come from the cortex and brainstem. They play a role in gating, sharpening, or regulating the flow of retinal input to other brain areas. Driving and modulatory inputs to the thalamus have been differentiated based on the morphology and synaptic properties of afferent axon terminals in the thalamus (Sherman and Guillery, 2011). The driver/modulator framework treats the thalamus as gating information flow and implicitly assumes that the processing of information relevant to shaping behavior happens, for the most part, upstream or downstream of the thalamus rather than in the thalamus itself.

The distinction between driving and modulatory inputs seems well suited to explain processing in primary sensory nuclei, but become less clear when one considers responses in thalamic nuclei interconnected with association cortices. While the driver/modulator framework would predict responses in these nuclei to be dominated by driving inputs from the cortex, recent studies in mice and monkeys have suggested that higher-order sensory thalamic nuclei actively integrate cortical inputs (Saalmann and Kastner, 2011; Wolff et al., 2021) and may represent abstract information derived from sensory input, such as perceptual confidence, as opposed to visual signals per se (Komura et al., 2013). The tendency toward greater abstraction in nonsensory nuclei was also demonstrated in a study of mouse mediodorsal thalamus (MD), a nucleus that projects to the prefrontal cortex, which found that MD neurons signal context cues during task switching and might use these signals to implement task switching through feedforward projections to cortex (Rikhye et al., 2018).

A recent study by Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) furthers the ongoing debate about whether thalamus processes information. The authors investigated signals within the central thalamus, which comprises the caudal part of the ventral lateral thalamic nucleus (VLc), the lateral MD (MDl), and the centrolateral thalamic nucleus (CL). The central thalamus receives inputs from the frontal cortex, cerebellum, and basal ganglia, and the authors use it as a model system to investigate how such convergent inputs are processed. This provides a novel framework for studying thalamic integration that will likely prove fruitful in isolating the function of central thalamus circuitry.

Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) trained monkeys on a missing-oddball-detection task likely to engage central thalamus. The oddball paradigm is commonly used in humans to assess temporal awareness (Squires et al., 1975) and has previously been adapted for use in primates across sensory domains (Ohmae et al., 2013; Camalier et al., 2019). In the version of the task the authors used, monkeys were trained to report the omission of a single stimulus within a sequence of visual-auditory stimuli presented at fixed intervals. There are several reasons why this is a useful paradigm for investigating information integration in the central thalamus. First, multiple lines of evidence across species suggest a central role for the central thalamus in timing movements (Tanaka, 2006; Lusk et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Second, the authors can leverage their own prior investigations of signals in cerebellar nuclei and striatum (Ohmae et al., 2013; Kameda et al., 2019) to determine which components of thalamic activity might rely on these dominant inputs to the central thalamus.

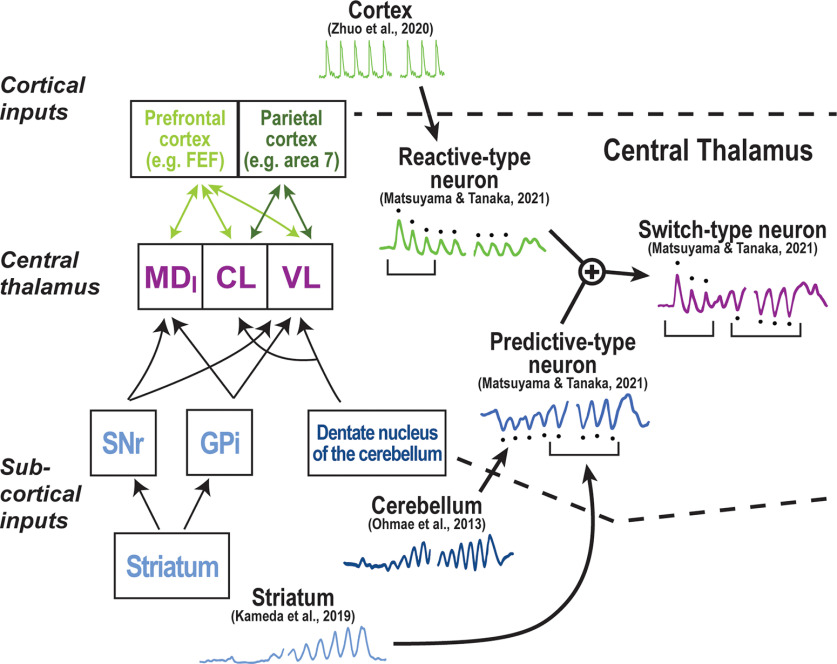

After training animals, the authors performed single-neuron recordings in the central thalamus and studied neural responses during task performance. They found that responses to the oddball sequence fell into three subclasses (Fig. 1) that varied in both the sign and timing of responses relative to a periodic visual stimulus. The authors suggest that two of these subclasses depend on the predominant input to the central thalamus. The first class, which the authors termed reactive type, responded to visual stimulus onset with a burst, and exhibited adaptation over repeated presentations of the stimulus. Neuronal responses resembled those in the parietal cortex (Suzuki and Gottlieb, 2013; Zhou et al., 2020), inferior temporal cortex (Kaliukhovich and Vogels, 2014), and visual cortex (Zhou et al., 2020). A second class, which the authors termed predictive type, exhibited neuronal responses that resembled those previously observed in primate striatum and cerebellum on the same task (Ohmae et al., 2013; Kameda et al., 2019). These neurons exhibited a weak suppressive response following stimulus onset, and the responses increased in amplitude with each stimulus repetition.

Figure 1.

Structure of inputs to the central thalamic nuclei and their role in an oddball task. Parietal cortical neurons exhibit transient visual responses to each oddball stimulus (Zhou et al., 2020). Responses may drive the activity of reactive-type neurons reported by Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) in central thalamus. In striatum and cerebellum, responses to each stimulus in an oddball paradigm are suppressive and occur at the time of stimulus onset (Kameda et al., 2019; Ohmae et al., 2013). These responses might form the main input to predictive-type neurons observed in central thalamus (Matsuyama and Tanaka, 2021). The responses of switch-type neurons in central thalamus might result from the integration of signals observed in reactive- and predictive-type neurons (Matsuyama and Tanaka, 2021). FEF = frontal eye field; MDl = lateral MD; CL = centrolateral thalamic nucleus; VL = ventral lateral thalamic nucleus; SNr = substantia nigra reticulata; GPi = globus pallidus internal.

Perhaps most notably, Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) discovered a novel subclass of cells, whose neural signature did not resemble those previously observed in other brain areas. Like reactive-type neurons, this class of neurons initially responded with strong bursts of activity following the onset of visual-auditory stimuli, with a latency of ∼120 ms. However, for later stimuli, cells exhibited a phase shift, with suppressive responses following stimulus onset, akin to the responses observed in predictive-type neurons. The shift in response profiles occurred rapidly: usually between the third and fourth presentation of the visual-auditory stimulus. Therefore, these cells were named switch-type neurons. Given the rapid shift in both the response profile and the timing of responses, the authors argue that the switch did not result from a slow adaptation from reactive to predictive responses.

The authors created a simple model to demonstrate that switch-type neurons might be generated by a simple weighted sum of reactive and predictive neuron signals. Apart from accounting for the core dynamic properties of switch-type neurons, an additional benefit of this computation is that it can also account for the continuum of responses that one sees from neurons that have very strong switch type-related activity to those neurons that show solely predictive responses.

The results of the study by Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) demonstrate that, in addition to their established role in regulating information flow to cortex, thalamic nuclei might actively integrate incoming signals. This fits well with previous results from studies of thalamic nuclei that border the central thalamus in both primates and rodents. For example, when recording neuronal responses on a memory-guided saccade task, Watanabe and Funahashi (2004) reported that primate MD contains more omnidirectional neurons than dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Omnidirectional neurons are thought to be capable of implementing computations that go beyond saccade execution or planning, indicating that MD can perform more general computations. Similarly, in rodent motor thalamus [VA–VL (ventroanterior–ventrolateral) complex], neurons respond to instructional cues rather than to movement kinematics, indicating that the role of motor thalamus might have more complex functions than relaying motor commands from subcortical structures (Gaidica et al., 2018). In the driver/modulator framework, the thalamus gates driving inputs transmitted to cortex, but does not process them internally. In contrast, the results of these studies suggest that thalamic networks have the ability to perform more complex computations on incoming signals, including an ability to integrate multiple driving inputs. While the distinction between driving and modulator inputs captures some aspects of signal processing, the driver/modulator framework is, in its current state, unable to account for the integration of multiple driving inputs within thalamus. In the future, it will be necessary to expand on the current driver/modulator framework to capture these dynamics.

At the same time, the work of Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) sheds light on the functional organization of thalamic nuclei. The authors recorded neuronal responses at the border of VLc, MDl, and CL, and found neurons from each of their identified subclasses within each of these thalamic nuclei. To date, divisions of nuclei within the central zone of the thalamus have been primarily based on either cytoarchitecture or their afferent inputs. The finding of Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) highlights that functional boundaries do not necessarily run between thalamic nuclei. Instead, functional regions within the thalamus might run along a gradient that stretches across nuclei or form patches within the thalamus.

While the findings of Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) are consistent with the hypothesis that thalamic circuits integrate information, it is possible that switch-type neurons instead represent inputs from other cortical/subcortical areas upstream of thalamus that have not yet been discovered. In addition, integration might rely on reciprocal loops between thalamus and cortex as suggested by recent studies in the mouse. For example, perturbation of either the anterior lateral motor cortex or the motor thalamus in the mouse disrupts sensory discrimination, and reciprocal excitatory projections between the two areas are necessary to sustain persistent activity required for correct judgments (Guo et al., 2017). An obvious follow-up experiment is to perform neural recordings from cortical regions that project to the central thalamus to determine whether the signature of switch-type neurons might also be found elsewhere. In addition, perturbation experiments can be used to determine whether inactivation of the striatum or cerebellum will only alter the signal of predictive-type neurons or also that of switch-type neurons; the latter being additional evidence that the signal of switch-type neurons relies on integration of reactive and predictive signals within the thalamus. In each case, we are confident that Matsuyama and Tanaka (2021) have developed an exciting experimental model that sheds light on the mechanisms of thalamic computation.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: These short reviews of recent JNeurosci articles, written exclusively by students or postdoctoral fellows, summarize the important findings of the paper and provide additional insight and commentary. If the authors of the highlighted article have written a response to the Journal Club, the response can be found by viewing the Journal Club at www.jneurosci.org. For more information on the format, review process, and purpose of Journal Club articles, please see http://jneurosci.org/content/jneurosci-journal-club.

References

- Camalier CR, Scarim K, Mishkin M, Averbeck BB (2019) A comparison of auditory oddball responses in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, and auditory cortex of macaque. J Cogn Neurosci 31:1054–1064. 10.1162/jocn_a_01387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidica M, Hurst A, Cyr C, Leventhal DK (2018) Distinct populations of motor thalamic neurons encode action initiation, action selection, and movement vigor. J Neurosci 38:6563–6573. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0463-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo ZV, Inagaki HK, Daie K, Druckmann S, Gerfen CR, Svoboda K (2017) Maintenance of persistent activity in a frontal thalamocortical loop. Nature 545:181–186. 10.1038/nature22324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliukhovich DA, Vogels R (2014) Neurons in macaque inferior temporal cortex show no surprise response to deviants in visual oddball sequences. J Neurosci 34:12801–12815. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2154-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda M, Ohmae S, Tanaka M (2019) Entrained neuronal activity to periodic visual stimuli in the primate striatum compared with the cerebellum. Elife 8:e48702. 10.7554/eLife.48702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komura Y, Nikkuni A, Hirashima N, Uetake T, Miyamoto A (2013) Responses of pulvinar neurons reflect a subject's confidence in visual categorization. Nat Neurosci 16:749–755. 10.1038/nn.3393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk N, Meck WH, Yin HH (2020) Mediodorsal thalamus contributes to the timing of instrumental actions. J Neurosci 40:6379–6388. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0695-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama K, Tanaka M (2021) Temporal prediction signals for periodic sensory events in the primate central thalamus. J Neurosci 41:1917–1927. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2151-20.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmae S, Uematsu A, Tanaka M (2013) Temporally specific sensory signals for the detection of stimulus omission in the primate deep cerebellar nuclei. J Neurosci 33:15432–15441. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1698-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikhye RV, Gilra A, Halassa MM (2018) Thalamic regulation of switching between cortical representations enables cognitive flexibility. Nat Neurosci 21:1753–1763. 10.1038/s41593-018-0269-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saalmann YB, Kastner S (2011) Cognitive and perceptual functions of the visual thalamus. Neuron 71:209–223. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW (2006) Exploring the thalamus and its role in cortical function, Ed 2. Cambridge, MA: MIT. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW (2011) Distinct functions for direct and transthalamic corticocortical connections. J Neurophysiol 106:1068–1077. 10.1152/jn.00429.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires NK, Squires KC, Hillyard SA (1975) Two varieties of long-latency positive waves evoked by unpredictable auditory stimuli in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 38:387–401. 10.1016/0013-4694(75)90263-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Gottlieb J (2013) Distinct neural mechanisms of distractor suppression in the frontal and parietal lobe. Nat Neurosci 16:98–104. 10.1038/nn.3282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M (2006) Inactivation of the central thalamus delays self-timed saccades. Nat Neurosci 9:20–22. 10.1038/nn1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Hosseini E, Meirhaeghe N, Akkad A, Jazayeri M (2020) Reinforcement regulates timing variability in thalamus. Elife 9:e55872. 10.7554/eLife.55872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Funahashi S (2004) Neuronal activity throughout the primate mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus during oculomotor delayed-responses. II. Activity encoding visual versus motor signal. J Neurophysiol 92:1756–1769. 10.1152/jn.00995.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, Morceau S, Folkard R, Martin-Cortecero J, Groh A (2021) A thalamic bridge from sensory perception to cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 120:222–235. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZC, Huang WA, Yu Y, Negahbani E, Stitt IM, Alexander ML, Hamm JP, Kato HK, Fröhlich F (2020) Stimulus-specific regulation of visual oddball differentiation in posterior parietal cortex. Sci Rep 10:13973. 10.1038/s41598-020-70448-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]