Abstract

Primary liver cancer accounts for the third most deadly type of malignant tumor globally, and approximately 80% of the cases are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which highly relies on the activity of hypoxia responsive pathways to bolster its metastatic behaviors. MicroRNA-29a (MIR29A) has been shown to exert a hepatoprotective effect on hepatocellular damage and liver fibrosis induced by cholestasis and diet stress, while its clinical and biological role on the activity hypoxia responsive genes including LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA remains unclear. TCGA datasets were retrieved to confirm the differential expression and prognostic significance of all genes in the HCC and normal tissue. The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset was used to corroborate the differential expression and diagnostic value of MIR29A. The bioinformatic identification were conducted to examine the interaction of MIR29A with LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA. The suppressive activity of MIR29A on LOX, LOXL2, and VEGF was verified by qPCR, immunoblotting, and luciferase. The effect of overexpression of MIR29A-3p mimics in vitro on apoptosis markers (caspase-9, -3, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)); cell viability and wound healing performance were examined using immunoblot and a WST-1 assay and a wound healing assay, respectively. The HCC tissue presented low expression of MIR29A, yet high expression of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA as compared to normal control. Serum MIR29A of HCC patients showed decreased levels as compared to that of normal control, with an area under curve (AUC) of 0.751 of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Low expression of MIR29A and high expression of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA indicated poor overall survival (OS). MIR29A-3p was shown to target the 3′UTR of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA. Overexpression of MIR29A-3p mimic in HepG2 cells led to downregulated gene and protein expression levels of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA, wherein luciferase reporter assay confirmed that MIR29A-3p exerts the inhibitory activity via directly binding to the 3′UTR of LOX and VEGFA. Furthermore, overexpression of MIR29A-3p mimic induced the activity of caspase-9 and -3 and PARP, while it inhibited the cell viability and wound healing performance. Collectively, this study provides novel insight into a clinical-applicable panel consisting of MIR29, LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA and demonstrates an anti-HCC effect of MIR29A via comprehensively suppressing the expression of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA, paving the way to a prospective theragnostic approach for HCC.

Keywords: microRNA-29a, hepatocellular carcinoma, metastasis, lysyl oxidase, lysyl oxidase like 2, vascular endothelial growth factor A, diagnosis, prognosis

1. Introduction

Primary liver cancer accounts for the third most deadly type of malignant tumor globally and approximately 80% of the cases are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1,2]. To date, despite the availability of many different therapeutic interventions, such as surgical resection, liver transplantation, radiofrequency ablation, chemoembolization, and target therapy [3], the prognosis of HCC remains poor, with a five-year overall survival (OS) rate below 20% [1]. One of the key factors is its propensity for metastatic progression and poor response to pharmacological approaches [3]. As such, the identification of promising theragnostic targets to improve the prognosis of the HCC patients is of vital importance.

The lysyl oxidase family members are secreted copper-dependent oxidases, including five paralogues: LOX, LOX-like 1–4 (LOXL1–4), which act to exert catalytic activity to remodel the cross-linking of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of fibrotic liver and that of a corrupted tumor microenvironment (TME) [4]. To date, the roles of LOX and LOXL2 in the clinical significance and therapeutic implication of HCC are mostly studied as compared to the other family members [5]. The fact that LOX and LOXL2 serving as critical factors in mediating the formation of a corrupted TME and promoting the progression of metastasis of HCC through activating pathways involved in hypoxia responsive signaling and angiogenesis, and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) has been highlighted [5]. For example, LOX acts to mediate angiogenesis via increasing the secreted vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) from HCC cells [6] and to augment metastatic behaviors by activating EMT program [7]. On the other hand, LOXL2 was reported to activate the process of angiogenesis through upregulating the HIF-1α/VEGF pathway [8] and promote HCC metastasis to distant organ via an AKT/fibronectin-dependent pathway [9]. Given the biological importance of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA in the cancer progression, a variety of targeting drugs has currently been evaluated in clinical trials [5,10,11,12]. Nonetheless, a treatment approach that can comprehensively targeting these factors to render therapeutic potential for the treatment of HCC is yet to be identified.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), a large family of small non-coding RNAs, was reported to feature diverse and crucial effect on the development and metastasis of HCC by targeting the 3′ untranslational region (3′UTR) of a variety of genes [13]. MIR29 family members consist of MIR29A, MIR29B, and MIR29C. The UCU sequence of MIR29A results in its high stability as compared to the rapid decay of MIR29B and MIR29C caused by the presence of UUU tri-uracil sequence [14]. The MIR29A expression features clinical significance in a variety of disease scenarios, including Alzheimer’s disease [15], Parkinson’s disease [16], ankylosing spondylitis [17], atherosclerosis [18], atrial fibrillation [19], active pulmonary tuberculosis [20], thoracic aneurysms [21], tendon disease [22], diabetes [23], scleroderma [24], cholestatic pediatric liver disease [25], and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [26]. Importantly, our previous studies have reported the hepatoprotective role of MIR29A in the scenario of cholestasis- or diet-induced steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], and growing evidence has revealed its regulatory role on HCC metastasis [13,39]. In terms of biological activity, MIR29A was reported to directly target VEGFA to perturb the wound healing process [40], and to directly target LOXL2 to impede tumor progression [41]. In this study, we demonstrated that MIR29A, along with LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA, exhibits diagnostic and prognostic significance and that overexpression of MIR29A notably contributes to suppression of cellular metastatic behaviors by comprehensively targeting the 3′UTR of the aforementioned genes, offering novel insights into the MIR29A-involved signaling in the development of a practical diagnostic/prognostic panel and a therapeutic strategy.

2. Results

2.1. The Aberrent Expression and the Prognostic Value of MIR29A, LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA in HCC Patients

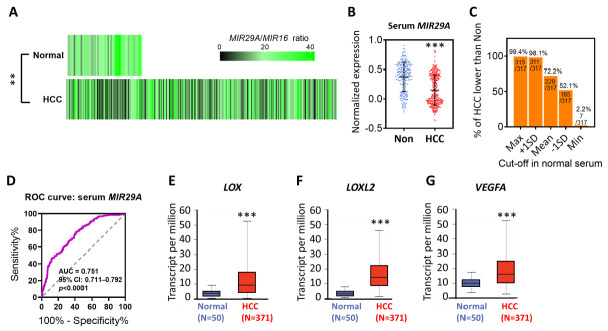

We firstly examined the MIR29A expression levels in HCC and normal tissue by accessing the TCGA datasets in the OncoMir Cancer Database (OMCD). Using MIR16 as a normalization control as previously described [42], HCC tumor tissue (375 TCGA datasets) presented significantly lower expression levels of MIR29A than that of normal tissue (51 TCGA datasets) (p < 0.01; Figure 1A). In addition, serum MIR29A expression normalized to MIR16 in HCC patients and non-cancer individuals from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) dataset presented a similar trending (p < 0.001; Figure 1B). The number (%) of HCC patients presenting a lower value than normal individuals at the cut-off of maximum, mean + 1SD, mean, mean-1SD, and minimum value of normal serum was 315/317 (99.4%), 311/317 (98.1%), 229/317 (72.2%), 165/317 (52.1), and 7/317 (2.2%), respectively (Figure 1C). We then asked whether MIR29A gene alteration in HCC plays a factor in its expression change. In this regard, we surveyed the MIR29A data with regard to structural variant, mutation, and copy number alterations (CNA) from TCGA PanCancer Atlas Studies using the cBioPortal web platform, where 10,953 patients/10,967 samples are included as of 26 May 2021. In HCC, MIR29A presented a 1.084% alteration frequency in amplification without the presence of deletion and mutation (Supplementary Figure S1), indicating that copy number alteration, deletion, and mutation scarcely contribute to an expression change of MIR29A. In addition, MIR29A expression between male and female HCC tissue showed no difference (Supplementary Figure S2), suggesting no potential gender bias acting on its expression in HCC tissue. Additionally, we determined the diagnostic value of serum MIR29A using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and noted that MIR29A presented good diagnostic accuracy for the discrimination of disease, with an area under curve (AUC) of 0.751 (95% CI: 0.711–0.792, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1D). Next, UALCAN web server-accessed TCGA datasets revealed that the mRNA of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA presented elevated expression levels in HCC tissue as compared to that in normal tissue (p < 0.001; Figure 1E–G).

Figure 1.

Differential expression analysis of MIR29A, LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA in HCC patients as compared to normal individuals. (A) Heatmap of MIR29A expression level in normal tissue and HCC, wherein 51 and 375 TCGA datasets were respectively accessed in the OncoMir Cancer Database (OMCD). MIR16 expression level served as normalization control. ** p < 0.01 between normal and HCC group. The raw data of TCGA samples retrieved from OMCD are shown in Supplementary File S1. (B) Serum MIR29A expression level of HCC patient and non-cancer individuals retrieved from the GSE113740 dataset. MIR16 expression level served as the normalization control. *** p < 0.001 between the non-cancer (Non) and HCC group. (C) The number (%) of HCC patients presenting a lower value than normal individuals at the cut-off of maximum, mean + 1SD, mean, mean-1SD, and minimum value of normal serum. (D) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for non-cancer and HCC cohorts based on serum MIR29A levels from the GSE113740 dataset. The gene expression level of LOX (E), LOXL2 (F), and VEGFA (G) in HCC and normal tissue retrieved from TCGA datasets. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 between the normal and HCC group. Panel E, F and G were adapted form UALCAN, which is an open assessed web server.

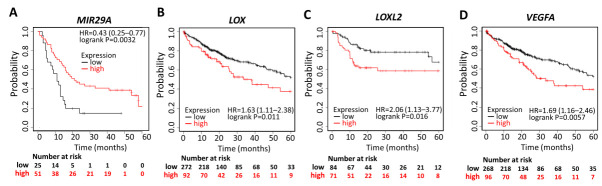

The correlation between the expression of MIR29A, LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA and corresponding clinical follow-up information was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test. High MIR29A expression was found to be associated with increased overall survival (OS) (HR = 0.43; p = 0.0032) (Figure 2A), while high expression of LOX (HR = 1.63; p = 0.011) (Figure 2B), LOXL2 (HR = 2.06; p = 0.016) (Figure 2C), and VEGFA (HR = 1.69; p = 0.0057) (Figure 2D) was associated with decreased OS. These results indicate that the downregulated MIR29A and upregulated LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA predicts poor prognosis, serve as an independent prognostic panel, and may contribute to HCC progression.

Figure 2.

Prognostic value of MIR29A, LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA in HCC patients. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis representing the probability of the overall survival (OS) in HCC patients based on low vs. high expression of MIR29A (A), LOX (B), LOXL2 (C), and VEGFA (D). HR, hazard ratio.

2.2. MIR29A Act as A Common Supressor of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA

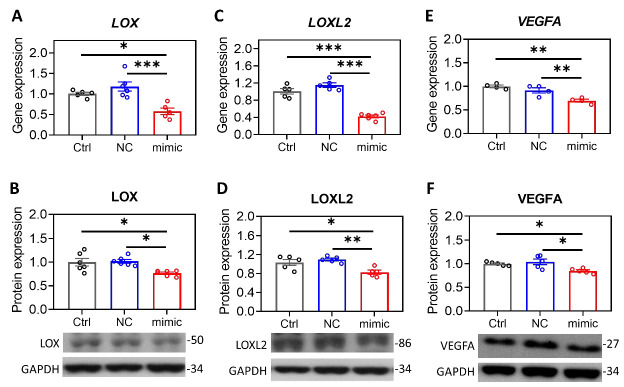

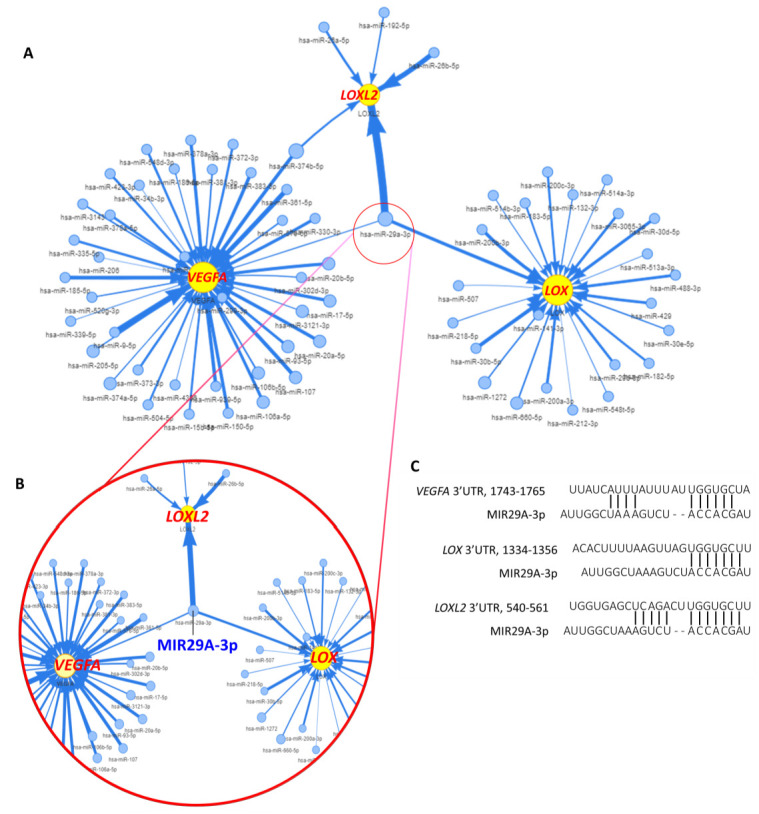

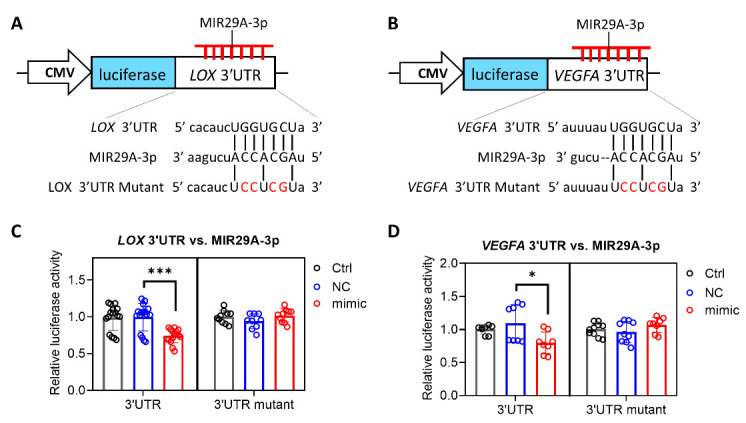

The contrary expression pattern between MIR29A and the aforementioned mRNAs in HCC tissue prompted us to ask whether MIR29A presents a pathway-centric manner on modulating the genes responsible for hypoxic adaptation, matrix remodeling, and angiogenesis. We conducted gene functional enrichment analysis to examine the microRNA-interacting network of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA using GSCALite and TargetScan Release 7.2. As shown in Figure 3, MIR29A-3p acts as a central hub in regulating LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA (Figure 3A,B) via putative binding at the 3′UTR (Figure 3C). We then verified the bioinformatic prediction by an in vitro experimental setting, where overexpression of MIR29A-3p in human HCC cell line HepG2 significantly inhibited the gene and protein expression of LOX (Figure 4A,B), LOXL2 (Figure 4C,D), and VEGFA (Figure 4E,F) (all p < 0.05). Additionally, the molecular interaction at posttranscriptional level was corroborated by luciferase reporter assay. As shown in Figure 5A,B, the pMIR-REPORTERTM plasmid comprises a strong protomer CMV to drive the expression of luciferase that is fused with the 3′UTR sequence of LOX or VEGFA (Figure 5A,B). Binding of MIR29A-3p to wild type 3′UTR leads to reduced luciferase signal, whereas the 3′UTR mutant serves as a negative control. Overexpression of MIR29A-3p suppressed the reported luciferase activity of wild type but not that of mutant, as compared to the negative control (NC)-treated group (all p < 0.05) (Figure 5C,D), revealing that the direct binding to LOX 3′UTR and VEGFA 3′UTR accounts for the suppression activity of MIR29A-3p.

Figure 3.

Bioinformatic identification of MIR29A as a common suppressor for LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA in HCC. (A) microRNA-interacting network of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA in the TCGA cohort of HCC. (B) The enlargement of MIR29A-3p-controlled network, revealing targeted genes LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA. (C) MIR29A-3p putative binding to the 3′UTR of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA were predicted by bioinformatic survey of TargetScan Release 7.2.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of MIR29A suppresses the gene and protein expression of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA. Human HCC HepG2 cells were treated with transfection reagent as a control (Ctrl), miR negative control sequence (NC), or MIR29A-3p mimic (mimic). Then, cell specimens of at least four independent experiments were processed for the detection of gene and protein expression levels of LOX (A,B), LOXL2 (C,D), and VEGFA (E,F) by using qPCR and western blot. 18S in qPCR was used for the normalization gene, while GAPDH in western blot served as the loading control. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 between the indicated groups.

Figure 5.

MIR29A-3p exerts a suppressive activity by directly targeting the 3′UTR of LOX and VEGFA. A schematic illustration of the pMIR-REPORTERTM plasmid for the cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven luciferase reporter assay for MIR29A-3p on LOX (A,C) and VEGFA (B,D). Nucleotides in red denotes mismatched mutation as compared to that of wild type. After transfection of the pMIR-REPORTERTM plasmid, HepG2 cells were treated with transfection reagent transfection reagent as a control (Ctrl), miR negative control sequence (NC), or MIR29A-3p mimic (mimic), followed by the detection of luciferase activity. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 between the indicated groups.

2.3. Overexpression of MIR29A Might Induce Apoptosis Signaling and Inhibits Wound Healing Performance and Viability in HCC Cells

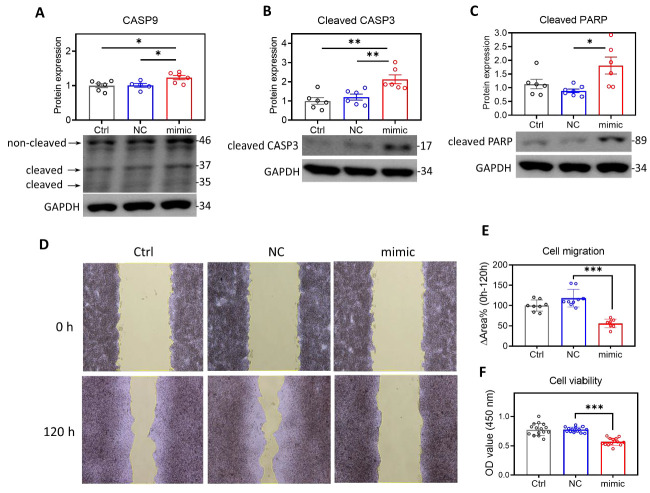

We then evaluated the effect of overexpression of MIR29A-3p mimics on the metastatic behaviors of HCC cells. As shown in Figure 6, overexpression of MIR29A-3p mimics induced a significant increase in the markers representing activated apoptosis signaling, including the increased ratio of cleaved/non-cleaved caspase-9 (Figure 6A), cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 6B), and cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (Figure 6C). Additionally, the wound healing assay showed that overexpression of MIR29A-3p mimics features a suppressive effect on cellular wound healing performance (Figure 6D,E). WST-1 assay revealed an overexpression of MIR29A-3p mimics saps cell viability (Figure 6F). Together, these results indicate that MIR29A acts toward the impeded metastatic behaviors of HCC cells.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of MIR29A-3p in HepG2 cells might induce apoptosis signaling and inhibits wound healing performance, and viability. HepG2 cells treated with transfection reagent as a control (Ctrl), MIRs negative sequence (NC), or MIR29A-3p mimic (mimic) for 24 h, followed by further assays. The activity of apoptosis signaling was examined by probing the cleaved (37 and 35 kDa)/non-cleaved (46 kDa) caspase-9 (CASP9) (A), cleaved caspase-3 (CASP3) (B), and cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (C). GAPDH as loading control. The ratio of cleaved/non-cleaved CASP9, and the GAPDH-normalized cleaved CASP3 and cleaved PARP were analyzed for the densitometric quantification. (D) Representative image at 0 h and 120 h of wound healing assay. (E) Quantification histogram of the changed area percentage (∆Area%) of the scratched ditch determined by the migrated cells. (F) Cell viability detected by WST-1-based OD450 signal. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 between indicated groups.

3. Discussion

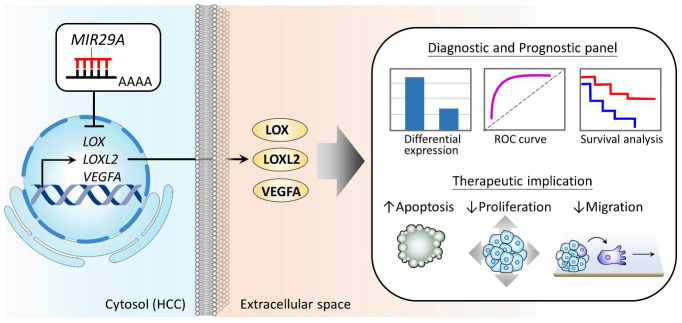

In this study, we demonstrated that MIR29A, LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA represent a panel of differential biomarkers and independent prognostic factors for HCC patients and that MIR29A acts as a common suppressor on these genes to impede the metastatic behaviors of HCC. The proposed model of the clinical value and the mechanism underlying MIR29A-centric pathways is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Proposed model illustrating the diagnostic and prognostic value of MIR29A and its biological role in suppressing HCC metastatic behaviors. MIR29A, LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA serves as a panel of diagnostic and prognostic factors. Mechanistically, elevated MIR29A acts toward the downregulation of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA, leading to an impeded metastatic behavior by inducing cell apoptosis and suppressing proliferation and migration.

There are a number of studies reporting that low expression of MIR29A represents a biomarker and a predictor for poor outcome in HCC patients [43,44,45,46], whereas a few reports showed an opposite expression manner [47,48]. In this study, a decreased expression of MIR29A is noted in HCC tissue as compared to that of normal tissue and serves as an independent factor for poor OS, in support of the aforementioned reports [43,44,45,46]. Zhu et al. and Xue et al. reported increased serum MIR29A as a diagnostic factor of HCC [42,49], while our study demonstrated that serum MIR29A expression was in parallel with that of tissue and exhibited a good diagnostic accuracy.

Although MIR29A-activated metastasis-suppression signaling pathways involving carcinogenesis, epigenetics, metabolic adaptation, and immunomodulation in HCC have been noted [39], its role in regulating factors modeling the structure of TME was yet to be clarified. In this regard, our study identified MIR29A as a common suppressor for LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA, which notably present a panel of diagnostic and prognostic factors along with MIR29A. As such, this finding provides new insights into clinical decision-making and the development of predictive settings for HCC.

There are increasing reports demonstrating the promising effect of targeting hypoxia-responsive genes, such as LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA. For instance, a couple of drugs targeting LOX family members are in the early stage of clinical trials [5], including pancreatic and colorectal adenocarcinoma [10,11]. Sorafenib was shown to hit the first breakthrough systemic therapy for treating advanced HCC via disrupting VEGF signaling [50]. Three angiogenesis inhibitor, Trebananib, rebastanib, and MEDI3617, have been evaluated in phase I and II clinical trials [51]. Despite the present lack of HCC trial using approaches targeting the activity of LOX family members, further investigation into broadening the horizons of this issues and the therapeutic strategy widely targeting critical factors are promising. In this study, we demonstrated the biological role of MIR29A in comprehensively inhibiting LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA and its effect on counteracting metastatic behaviors by inducing apoptosis and repressing cell viability and wound healing performance, indicating the potential of MIR29A as an adjuvant therapy that may further enhance the treatment effectiveness of the targeting therapy for HCC. Nevertheless, further studies mimicking the physiological circumstance such as in vivo evaluation is warranted to clarify the safety and efficacy in a preclinical setting.

In summary, this study provides novel insight into a clinically applicable panel consisting of MIR29, LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA and demonstrates an anti-HCC effect of MIR29A via comprehensively suppressing the expression of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA, paving the way to a prospective theragnostic approach for HCC.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Analysis of Gene Differential Expression and Prognostic Significance

The MIR29A expression levels in HCC and normal liver tissue were analyzed using the OncoMiR Cancer Database (OMCD) web server, a repository enabling systemic comparative genome analysis of miR expression sequencing data derived from over 10,000 cancer patients with associated clinical information and organ-specific controls present in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database [52]. The raw data of TCGA samples retrieved from OMCD are shown in Supplementary File 1. Serum MIR29A expression levels in HCC and non-cancer cohorts were analyzed using National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accessed on 25 April 2021)) [53], GSE113740. The comparison of the gene expression level in HCC and normal tissue was undertaken in UALCAN web server [54], which facilitates access to publicly available cancer OMICS data, such as TCGA and Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC). MIR16 served as normalization control as previously described [42].

Kaplan–Meier analysis, which was used to determine the prognostic value of biomarkers, was conducted in the Kaplan-Meier plotter web server (available online: https://kmplot.com/analysis/ (accessed on 25 April 2021)), which includes data sources from GEO, European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), and TCGA to enable the assessment of the effect of 54 k genes, including mRNA, miR, and protein on survival in 21 cancer types [55]. The prognostic value of miR and mRNA was evaluated by using the panel miRpower for liver cancer [56] and RNA-seq for liver cancer [57] of the KM plotter, respectively.

4.2. Bioinformatic Analysis of MIR29A-mRNA Interaction

The microRNA interacting network of LOX, LOXL2, and VEGFA2 was retrieved from GSCALite, which is a gene set cancer analysis platform that integrates cancer genomic data from the TCGA [58]. Prediction of MIR29A-5p/-3p interaction was conducted using the TargetScan release 7.2 database (available online: http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/ (accessed on 25 April 2021)) [59].

4.3. Cell Culture and Transfection

Human HCC cell line HepG2 were purchased from American Type Tissue Collection (ATCC) and cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; 10437-028, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (15240-062, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The oligonucleotides of the MIR29A mimics and their corresponding MIR negative control were purchased from GE Healthcare Dharmacon (C-300504-07-0050 and CN-001000-01-50, respectively). The transfection of MIR29A mimics and the negative control was carried out with Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (13778-150, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were collected 24 h after transfection for further experiments.

4.4. Luciferase Reporter Assay

To investigate the molecular basis of MIR29A-3p acting on LOX and VEGFA, HepG2 cells were respectively transfected with pMIR-LOX-3′UTR and pMIR-VEGFA-3′UTR followed by transfection of reagent only, MIR negative sequence, or MIR29A-3p mimic. Cells transfected with pMIR-LOX-3′UTR mutant and pMIR-VEGFA-3′UTR mutant served as the negative control. Specifically, the sequence of wild type 3′UTR or mutated 3′UTR were cloned into the multiple cloning site after the CMV-driven luciferase (Figure 3B) of the pMIR-REPORTERTM plasmid (AM5795, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Then, HepG2 cells were seeded at 1.8 × 106 cells in a 100 mm dish for 18 h. Next, 6 μg reporter plasmids were transfected into a 100 mm dish cultivating HepG2 cells in the presence of Turbofect transfection reagent (R0531, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) for 20 h. HepG2 were subsequently trypsinized and seeded at 9 × 105 cells in a 60 mm dish with fresh growth medium. Furthermore, 25 nM MIR29A-3p mimic (C-300504-07-0050, GE Healthcare Dharmacon, IN, USA), MIR negative control (CN-001000-01-50, GE Healthcare Dharmacon), or no-sequence control (Ctrl) were transfected into cells in the presence of RNAiMAX transfection reagent (#13778-150, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 24 h. Finally, cells were lysed for the detection of luciferase signal with Neolite Reporter Gene Assay System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA of the cells was extracted by using TRIzol® reagent (15596026, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then underwent reverse transcription to yield cDNA with an oligodeoxynucleotide primer (oligo dT15)-based method according to the manufacturer’s protocol (M1701, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The qPCR reaction was undertaken using 2 × SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (04887352001, Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA) on LightCycler480® (Roche). Each PCR reaction included 0.5 μM forward and reverse primers, 30 ng of cDNA, and 1 × SYBR Green PCR Master Mix in a total reaction volume of 10 μL. For qPCR program, an initial amplification was done with a denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 62 °C for 15 s, and primer extension at 72 °C for 25 s, followed by melting curve analysis. The primer sequences for human genes were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers pairs.

| Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | |

|---|---|---|

| LOX | 5′-CAGCAGATCCAATGGGAGAAC-3′ | 5′-GCTGAGGCTGGTACTGTGAG-3′ |

| LOXL2 | 5′-TGTACCGCCATGACATCGAC-3′ | 5′-TAGCGGCTCCTGCATTTCAT-3′ |

| VEGFA | 5′-AAGGGGCAAAAACGAAAGCG-3′ | 5′-GCTCCAGGGCATTAGACAGC-3′ |

| 18S | 5′-GTAAC CCGTT GAACC CCATT-3′ | 5′-CCATC CAATC GGTAG TAGCG-3′ |

4.6. Western Blotting

The western blotting procedure was compatible with a quantitative approach, as described previously [60]. Briefly, approximately 1 × 106 cells were lysed in protein lysis buffer (17081, iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea), homogenized, and then centrifugated. The resulting supernatant lysates underwent protein quantitation measurement using Bio-RAD protein assay, in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (LIT33, Bio-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). The bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a standard to construct a standard curve for the relative quantitation of the proteins in the samples. Next, 40 µg of protein was separated in 8–15%SDS-PAGE, which was then transferred onto PVDF membrane and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibodies included LOX (1:1000; NB100-2527, Novus, CO, USA), LOXL2 (1:1000; GTX105085, GeneTex, Irvine, USA), VEGFA (1:1000; ab46154, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), caspase 9 (1:1000; 10380-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA), cleaved caspase-3 (1:1000; #9661, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), cleavedPARP (1:1000; #9541, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), and GAPDH (1:100,000; 60004-1-lg, Proteintech). After washing twice with TBST solution, PVDF membrane was incubated with secondary antibodies, such as horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit immunoglobulin-G antibodies (1:5000; NEF812001EA, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) or HRP anti-mouse immunoglobulin-G antibodies (1:10,000; NEF822001, PerkinElmer) at room temperature for 1 h. The blots were developed with an ECL Western blotting system and exposed them to film (GE28-9068-37, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The signals were quantified by using Quantity One® 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The accurate quantitative value of the target protein was normalized by its corresponding GAPDH.

4.7. Wound Healing Assay

Wound healing assay was employed to detect the wound healing performance of the cells. In each culture-insert, 5 × 105 HepG2 cells were seeded (ibidi culture-insert 2 well, ibidi GmbH, Martinsried, Germany) overnight to allow attachment. Then, the culture-insert was removed, thereby creating a bar of wound. Furthermore, PBS was used to wash out the unattached cells. After the transfection of 25 nM MIR29A mimics and their corresponding MIR negative control, the culture plate was photographed to document the width of the wound under a light microscope (50× magnification) at 0 and 120 h. The area of the wound was quantified using imageJ Version 1.53i.

4.8. Cell Viability Assay

WST-1 assay was used to determine the cell viability. In each 96-well, 5 × 105 HepG2 cells were seeded at a volume of 100 μL. After attachment, cells were transfected with 25 nM MIR29A mimics and their corresponding MIR negative control for 24 h, followed by the addition of 10 μL WST-1 reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, QC, Canada) for another 1 h at 37 °C. The absorbance signal was measured using a microplate reader (Hidex Sense microplate reader, Turku, Finland) at a test wavelength of 450 nm and reference wavelength of 630 nm.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± standard error (SE). Quantitative data were analyzed using unpaired t-test for two-group comparison or one-way analysis of variance for three-or-more-group comparison when appropriate. Least significant difference (LSD) test was used for post-hoc analysis. Two-sided p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yuan-Ting Chuang and Chia-Ling Wu for assisting with this article.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms22116001/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-L.Y., H.-Y.L. and Y.-H.H.; methodology, H.-Y.L. and M.-C.T.; software, H.-Y.L. and Y.-H.C.; validation, C.-C.W., and P.-Y.C.; formal analysis, P.-Y.C.; investigation, P.-Y.C.; resources, Y.-H.H.; data curation, H.-Y.L., M.-C.T., and Y.-H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-L.Y., H.-Y.L. and P.-Y.C.; writing—review and editing, H.-Y.L. and Y.-H.H.; visualization, H.-Y.L.; supervision, P.-Y.C.; project administration, Y.-L.Y. and Y.-H.H.; funding acquisition, Y.-L.Y. and Y.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (106-2314-B-182A-141 -MY3, 108-2314-B-182A-066-, 108-2811-B-182A-509, 106-2314-B-442-001-MY3, 109- 2314-B-442-001, and 109-2314-B-075B-002), National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-109BCCO-MF202015-01), Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (CMRPG8K1071 and CMRPG8K0981), and Show Chwan Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (SRD-109023, SRD-109024, SRD-109025, RD107063, and SRD-110008). However, these organizations had no part in the study design, data collection and analysis, publication decisions, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors hereby declare no conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aly A., Ronnebaum S., Patel D., Doleh Y., Benavente F. Epidemiologic, humanistic and economic burden of hepatocellular carcinoma in the USA: A systematic literature review. Hepat. Oncol. 2020;7:HEP27. doi: 10.2217/hep-2020-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet J.M., Zucman-Rossi J., Pikarsky E., Sangro B., Schwartz M., Sherman M., Gores G. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016;2:16018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye M., Song Y., Pan S., Chu M., Wang Z.W., Zhu X. Evolving roles of lysyl oxidase family in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;215:107633. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin H.Y., Li C.J., Yang Y.L., Huang Y.H., Hsiau Y.T., Chu P.Y. Roles of lysyl oxidase family members in the tumor microenvironment and progression of liver cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:9751. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang M., Liu J., Wang F., Tian Z., Ma B., Li Z., Wang B., Zhao W. Lysyl oxidase assists tumorinitiating cells to enhance angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2019;54:1398–1408. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umezaki N., Nakagawa S., Yamashita Y.I., Kitano Y., Arima K., Miyata T., Hiyoshi Y., Okabe H., Nitta H., Hayashi H., et al. Lysyl oxidase induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and predicts intrahepatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:2033–2043. doi: 10.1111/cas.14010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan Z., Zheng W., Li H., Wu W., Liu X., Sun Z., Hu H., Du L., Jia Q., Liu Q. LOXL2 upregulates hypoxiainducible factor1alpha signaling through SnailFBP1 axis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2020;43:1641–1649. doi: 10.3892/or.2020.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu S., Zheng Q., Xing X., Dong Y., Wang Y., You Y., Chen R., Hu C., Chen J., Gao D., et al. Matrix stiffness-upregulated LOXL2 promotes fibronectin production, MMP9 and CXCL12 expression and BMDCs recruitment to assist pre-metastatic niche formation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;37:99. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0761-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hecht J.R., Benson A.B., 3rd, Vyushkov D., Yang Y., Bendell J., Verma U. A Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of simtuzumab in combination with FOLFIRI for the second-line treatment of metastatic KRAS mutant colorectal adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2017;22:243-e23. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson A.B., 3rd, Wainberg Z.A., Hecht J.R., Vyushkov D., Dong H., Bendell J., Kudrik F. A Phase II Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled study of simtuzumab or placebo in combination with gemcitabine for the first-line treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2017;22:241-e15. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finn R.S., Zhu A.X. Targeting angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: Focus on VEGF and bevacizumab. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:503–509. doi: 10.1586/era.09.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X., He Y., Mackowiak B., Gao B. MicroRNAs as regulators, biomarkers and therapeutic targets in liver diseases. Gut. 2021;70:784–795. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z., Zou J., Wang G.K., Zhang J.T., Huang S., Qin Y.W., Jing Q. Uracils at nucleotide position 9-11 are required for the rapid turnover of miR-29 family. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4387–4395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller M., Jakel L., Bruinsma I.B., Claassen J.A., Kuiperij H.B., Verbeek M.M. MicroRNA-29a Is a candidate biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease in cell-free cerebrospinal fluid. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016;53:2894–2899. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9156-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goh S.Y., Chao Y.X., Dheen S.T., Tan E.K., Tay S.S. Role of MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:5649. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J., Song G., Yin Z., Fu Z., Ye Z. MiR-29a and Messenger RNA expression of bone turnover markers in canonical wnt pathway in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin. Lab. 2017;63:955–960. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2017.161214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y.Q., Cai A.P., Chen J.Y., Huang C., Li J., Feng Y.Q. The Relationship of Plasma miR-29a and oxidized low density lipoprotein with atherosclerosis. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2016;40:1521–1528. doi: 10.1159/000453202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y., Yuan Y., Qiu C. Underexpression of CACNA1C Caused by Overexpression of microRNA-29a Underlies the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrillation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016;22:2175–2181. doi: 10.12659/MSM.896191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afum-Adjei Awuah A., Ueberberg B., Owusu-Dabo E., Frempong M., Jacobsen M. Dynamics of T-cell IFN-gamma and miR-29a expression during active pulmonary tuberculosis. Int. Immunol. 2014;26:579–582. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxu068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones J.A., Stroud R.E., O’Quinn E.C., Black L.E., Barth J.L., Elefteriades J.A., Bavaria J.E., Gorman J.H., 3rd, Gorman R.C., Spinale F.G., et al. Selective microRNA suppression in human thoracic aneurysms: Relationship of miR-29a to aortic size and proteolytic induction. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2011;4:605–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.960419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millar N.L., Gilchrist D.S., Akbar M., Reilly J.H., Kerr S.C., Campbell A.L., Murrell G.A.C., Liew F.Y., Kurowska-Stolarska M., McInnes I.B. MicroRNA29a regulates IL-33-mediated tissue remodelling in tendon disease. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6774. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu Y.C., Chang P.J., Ho C., Huang Y.T., Shih Y.H., Wang C.J., Lin C.L. Protective effects of miR-29a on diabetic glomerular dysfunction by modulation of DKK1/Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:30575. doi: 10.1038/srep30575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawashita Y., Jinnin M., Makino T., Kajihara I., Makino K., Honda N., Masuguchi S., Fukushima S., Inoue Y., Ihn H. Circulating miR-29a levels in patients with scleroderma spectrum disorder. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011;61:67–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldschmidt I., Thum T., Baumann U. Circulating miR-21 and miR-29a as Markers of disease severity and etiology in cholestatic pediatric liver disease. J. Clin. Med. 2016;5:28. doi: 10.3390/jcm5030028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin H.Y., Yang Y.L., Wang P.W., Wang F.S., Huang Y.H. The emerging role of MicroRNAs in NAFLD: Highlight of MicroRNA-29a in modulating oxidative stress, inflammation, and beyond. Cells. 2020;9:1041. doi: 10.3390/cells9041041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Y.H., Kuo H.C., Yang Y.L., Wang F.S. MicroRNA-29a is a key regulon that regulates BRD4 and mitigates liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019;16:212–220. doi: 10.7150/ijms.29930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Y.H., Tiao M.M., Huang L.T., Chuang J.H., Kuo K.C., Yang Y.L., Wang F.S. Activation of Mir-29a in activated hepatic stellate cells modulates its profibrogenic phenotype through inhibition of histone deacetylases 4. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0136453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Y.H., Yang Y.L., Huang F.C., Tiao M.M., Lin Y.C., Tsai M.H., Wang F.S. MicroRNA-29a mitigation of endoplasmic reticulum and autophagy aberrance counteracts in obstructive jaundice-induced fibrosis in mice. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018;243:13–21. doi: 10.1177/1535370217741500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y.H., Yang Y.L., Wang F.S. The Role of miR-29a in the regulation, function, and signaling of liver fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1889. doi: 10.3390/ijms19071889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li S.C., Wang F.S., Yang Y.L., Tiao M.M., Chuang J.H., Huang Y.H. Microarray study of pathway analysis expression profile associated with MicroRNA-29a with regard to murine cholestatic liver injuries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:324. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin H.Y., Wang F.S., Yang Y.L., Huang Y.H. MicroRNA-29a Suppresses CD36 to Ameliorate High Fat Diet-Induced Steatohepatitis and Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Cells. 2019;8:1298. doi: 10.3390/cells8101298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Y.C., Wang F.S., Yang Y.L., Chuang Y.T., Huang Y.H. MicroRNA-29a mitigation of toll-like receptor 2 and 4 signaling and alleviation of obstructive jaundice-induced fibrosis in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;496:880–886. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiao M.M., Wang F.S., Huang L.T., Chuang J.H., Kuo H.C., Yang Y.L., Huang Y.H. MicroRNA-29a protects against acute liver injury in a mouse model of obstructive jaundice via inhibition of the extrinsic apoptosis pathway. Apoptosis. 2014;19:30–41. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y.L., Kuo H.C., Wang F.S., Huang Y.H. MicroRNA-29a Disrupts DNMT3b to Ameliorate diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1499. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y.L., Wang F.S., Li S.C., Tiao M.M., Huang Y.H. MicroRNA-29a alleviates bile duct ligation exacerbation of hepatic fibrosis in mice through epigenetic control of methyltransferases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:192. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y.L., Wang F.S., Lin H.Y., Huang Y.H. Exogenous Therapeutics of Microrna-29a Attenuates Development of Hepatic Fibrosis in Cholestatic Animal Model through Regulation of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase p85 Alpha. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3636. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y.L., Wang P.W., Wang F.S., Lin H.Y., Huang Y.H. miR-29a Modulates GSK3beta/SIRT1-linked mitochondrial proteostatic stress to ameliorate mouse non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:6884. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y.L., Chang Y.H., Li C.J., Huang Y.H., Tsai M.C., Chu P.Y., Lin H.Y. New Insights into the Role of miR-29a in hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications in mechanisms and theragnostics. J. Pers Med. 2021;11:219. doi: 10.3390/jpm11030219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang L., Engeland C.G., Cheng B. Social isolation impairs oral palatal wound healing in sprague-dawley rats: A role for miR-29 and miR-203 via VEGF suppression. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dey S., Kwon J.J., Liu S., Hodge G.A., Taleb S., Zimmers T.A., Wan J., Kota J. miR-29a Is Repressed by MYC in Pancreatic Cancer and Its Restoration Drives Tumor-Suppressive Effects via Downregulation of LOXL2. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020;18:311–323. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xue X., Zhao Y., Wang X., Qin L., Hu R. Development and validation of serum exosomal microRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell Biochem. 2019;120:135–142. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi Y., Kong W., Lu Y., Zheng Y. Traditional Chinese Medicine Xiaoai Jiedu recipe suppresses the development of hepatocellular carcinoma via Regulating the microRNA-29a/Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 Axis. Oncol. Targets Ther. 2020;13:7329–7342. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S248797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44.Zhang Y., Yang L., Wang S., Liu Z., Xiu M. MiR-29a suppresses cell proliferation by targeting SIRT1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2018;22:151–159. doi: 10.3233/CBM-171120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahati S., Xiao L., Yang Y., Mao R., Bao Y. miR-29a suppresses growth and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating CLDN1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;486:732–737. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parpart S., Roessler S., Dong F., Rao V., Takai A., Ji J., Qin L.X., Ye Q.H., Jia H.L., Tang Z.Y., et al. Modulation of miR-29 expression by alpha-fetoprotein is linked to the hepatocellular carcinoma epigenome. Hepatology. 2014;60:872–883. doi: 10.1002/hep.27200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Q., Yin D., Zhang Y., Yu L., Li X.D., Zhou Z.J., Zhou S.L., Gao D.M., Hu J., Jin C., et al. MicroRNA-29a induces loss of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and promotes metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma through a TET-SOCS1-MMP9 signaling axis. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2906. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu H.T., Dong Q.Z., Sheng Y.Y., Wei J.W., Wang G., Zhou H.J., Ren N., Jia H.L., Ye Q.H., Qin L.X. MicroRNA-29a-5p is a novel predictor for early recurrence of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu H.T., Hasan A.M., Liu R.B., Zhang Z.C., Zhang X., Wang J., Wang H.Y., Wang F., Shao J.Y. Serum microRNA profiles as prognostic biomarkers for HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:45637–45648. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gillen J., Richardson D., Moore K. Angiopoietin-1 and Angiopoietin-2 Inhibitors: Clinical Development. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019;21:22. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarver A.L., Sarver A.E., Yuan C., Subramanian S. OMCD: OncomiR Cancer Database. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:1223. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5085-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A.E. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chandrashekar D.S., Bashel B., Balasubramanya S.A.H., Creighton C.J., Ponce-Rodriguez I., Chakravarthi B., Varambally S. UALCAN: A portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival Analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19:649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagy A., Munkacsy G., Gyorffy B. Pancancer survival analysis of cancer hallmark genes. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:6047. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84787-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagy A., Lanczky A., Menyhart O., Gyorffy B. Validation of miRNA prognostic power in hepatocellular carcinoma using expression data of independent datasets. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:9227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27521-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Menyhart O., Nagy A., Gyorffy B. Determining consistent prognostic biomarkers of overall survival and vascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018;5:181006. doi: 10.1098/rsos.181006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu C.J., Hu F.F., Xia M.X., Han L., Zhang Q., Guo A.Y. GSCALite: A web server for gene set cancer analysis. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3771–3772. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agarwal V., Bell G.W., Nam J.W., Bartel D.P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife. 2015;4:e05005. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pillai-Kastoori L., Schutz-Geschwender A.R., Harford J.A. A systematic approach to quantitative Western blot analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2020;593:113608. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2020.113608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material.