Abstract

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is a leading cause of death in patients with refractory epilepsy. Centrally-mediated respiratory dysfunction has been identified as one of the principal mechanisms responsible for SUDEP. Seizures generate a surge in adenosine release. Elevated adenosine levels suppress breathing. Insufficient metabolic clearance of a seizure-induced adenosine surge might be a precipitating factor in SUDEP. In order to deliver targeted therapies to prevent SUDEP, reliable biomarkers must be identified to enable prompt intervention. Because of the integral role of the phrenic nerve in breathing, we hypothesized that suppression of phrenic nerve activity could be utilized as predictive biomarker for imminent SUDEP.

We used a rat model of kainic acid-induced seizures in combination with pharmacological suppression of metabolic adenosine clearance to trigger seizure-induced death in tracheostomized rats. Recordings of EEG, blood pressure, and phrenic nerve activity were made concomitant to the seizure. We found suppression of phrenic nerve burst frequency to 58.9% of baseline (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA) which preceded seizure-induced death; importantly, irregularities of phrenic nerve activity were partly reversible by the adenosine receptor antagonist caffeine. Suppression of phrenic nerve activity may be a useful biomarker for imminent SUDEP. The ability to reliably detect the onset of SUDEP may be instrumental in the timely administration of potentially lifesaving interventions.

Keywords: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, seizures, epilepsy, phrenic nerve activity, adenosine

1. INTRODUCTION

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is the leading cause of epilepsy-related death in patients with refractory epilepsy. The lifetime risk of SUDEP can be as high as 35% in at risk populations (Massey et al., 2014). The pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for SUDEP have not been clearly defined; however, convergent lines of evidence from human and animal studies have implicated some combination of centrally-mediated respiratory and cardiac dysfunction following a seizure (Elmali et al., 2019; Jones and Thomas, 2017; Massey et al., 2014). Continuous video EEG of patients in epilepsy monitoring units has demonstrated that SUDEP is typified by a generalized tonic-clonic seizure followed by centrally-mediated terminal apnea and then cardiac arrest (Ryvlin et al., 2013). This same sequence has been observed in animal models of SUDEP (Faingold et al., 2010; Lertwittayanon et al., 2020). Two major unmet clinical goals are: (1) a consistent predictive biomarker of imminent SUDEP; and (2) a therapeutic intervention capable of reliably preventing SUDEP. If these goals could be achieved, a predictive biomarker of SUDEP onset might be used in concert with a therapeutic intervention in a closed-loop system to prevent this devastating and highly enigmatic phenomenon.

Understanding the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the fatal derangement of cardiorespiratory function seen in SUDEP may be critical to developing lifesaving countermeasures. One of the potential mechanisms implicated in SUDEP is based on excessive seizure-induced release of the inhibitory neuromodulator adenosine. During a seizure, the brain releases adenosine as a neuro-protective mechanism to reduce neural transmission and abate seizure activity via the activation of A1 receptors (During and Spencer, 1992; Fedele et al., 2006; Ilie et al., 2012; Li et al., 2007; Lovatt et al., 2012). The inhibitory effect of adenosine release in forebrain structures is beneficial in its critical role in seizure termination; however, elevated adenosine in the brainstem causes respiratory suppression (Barraco et al., 1990), presumably by its interaction with A2A receptors influencing the GABAergic modulation of respiratory circuits (Mayer et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2004; Zaidi et al., 2006). Under normal conditions, adenosine is rapidly metabolized into adenosine monophosphate or inosine by the enzymes adenosine kinase and adenosine deaminase, respectively. Unfortunately, this mechanism for endogenous adenosine clearance may be inadequate following the up to 10-fold increases in extracellular adenosine seen in the postictal period. As such, seizure-induced adenosine release, in combination with insufficient metabolic clearance, may result in the respiratory failure which is characteristic of SUDEP (Massey et al., 2014). Pharmacological inhibition of adenosine metabolism prior to kainic acid seizure induction in mice delays the onset of seizure activity (ostensibly due to elevated adenosine levels in the forebrain) but, causes seizure-induced death (ostensibly due elevated adenosine levels in the brainstem) (Shen et al., 2010). In this model, the adenosine receptor antagonist caffeine delays seizure induced death (Shen et al., 2010). Like seizures, traumatic brain injury elicits a large increase in adenosine release. Apneas and mortality consequent to traumatic brain injury in rats is reduced by caffeine treatment (Lusardi et al., 2012). Taken together, the results of these studies suggest that adenosine may play a critical role in the mechanisms responsible for SUDEP.

The aim of this study was to (1) evaluate suppression of phrenic nerve activity (PNA) as predictor for SUDEP and (2) to test the therapeutic efficacy of caffeine to reverse seizure-induced PNA changes. Accomplishing these goals would bring us closer to our overarching goal of a closed-loop system for SUDEP prevention. Our approach was to monitor EEG, blood pressure, heart rate, and the electrophysiological activity of the phrenic nerve during seizures in a rat model of kainic acid induced seizures with impaired metabolic adenosine clearance. The kainic acid model used here produces protracted seizure activity and is a well characterized model of status epilepticus (Bertoglio et al., 2017). Although the experimental approach employed in this investigation does not model SUDEP, the insights into seizure-induced respiratory arrest gained in this model may be translatable to SUDEP. Additional experimentation in other models of seizure-induced death will be needed to determine the efficacy of PNA as a biomarker of imminent SUDEP. Further, animals were tracheostomized to eliminate the possible contribution of laryngospasm in precipitating sudden death (Irizarry et al., 2020; Stewart et al., 2017). We then compared these observations to those taken from animals treated with caffeine after the onset of PNA suppression. Our results suggest that suppression of PNA may be a useful biomarker for imminent SUDEP and that caffeine partially reverses the PNA abnormalities observed in this model.

2. METHODS

2.1. Animals

The experiments performed in this study were conducted in a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, with study protocols in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Rutgers University. All experiments were performed on adult male Wistar rats (n = 30, 310 – 400 grams, 8 – 11 weeks of age) obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA).

2.2. General Surgical Procedure

The following procedures have been reported previously by our group (Chitravanshi and Sapru, 1996, 1999, 2002). Under general anesthesia (2% isoflurane, 98% O2) tracheostomy was performed using PE-240 tubing. The rats were then artificially ventilated (46–48 cycles/min, 2.5 mL tidal volume) through the tracheostomy tube using a rodent ventilator (model 683, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Body temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C using a rectal temperature probe (RET-1, Physitemp Instruments, Clifton, NJ) connected to a temperature controller and infrared heat lamp (TCAT-2A). The right femoral artery was cannulated for hemodynamic monitoring. The cannulation was connected to a pressure transducer, and data capture and analysis was carried out with the CED 1401 data acquisition unit and Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). The right and left femoral veins were cannulated for administration of urethane and drug infusion, respectively. Following cannulation, the animal was gradually transitioned from isoflurane to urethane anesthesia (1.2 g/kg, intravenous) over the course of 25–35 minutes. Urethane was infused in a 75 mg/ml solution at a constant rate of 0.19 ml/min. Following urethane administration, the ventilator was removed for the remainder of the experiment. The depth of anesthesia was assessed every 15 minutes by pinching of the hind limb, with the absence of an increase in blood pressure or withdrawal of the limb indicating the rats were well anesthetized. In the case of insufficient depth of anesthesia, an additional 10% of the initial urethane dose was administered.

2.3. EEG and Phrenic Nerve Recording

The animals were fixed in a prone position into a stereotactic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tajunga, CA). For EEG recording, stainless steel epidural screw electrodes were placed over the hippocampus bilaterally (3.5 mm posterior to bregma, 3 mm lateral from the midline) (Bhandare et al., 2016). Steel wire was firmly placed between the head of the screw and the calvarium. The phrenic nerve was isolated on one side with a dorsolateral approach. The nerve was dissected away from the underlying connective tissue. stally, de-sheathed, and placed onto a bipolar platinum hook electrode. The nerve was embedded in a silicone elastomer (Kwil-Sil). The EEG and phrenic nerve electrodes were connected to a Super-Z head stage (Super-Z; CWE, Ardmore, PA) for signal amplification and relayed to another amplifier (BMA-830, CWE, Ardmore, PA; filtered at 0.1–10kHz). Data capture and analysis was done using the CED 1401 data acquisition unit and Spike2 software.

2.4. Drugs and Injection Timeline

Animals were treated with the following drugs via intravenous infusion in this study: 5-iodotuberocidin (3 mg/kg), an inhibitor of adenosine kinase (the key enzyme for metabolic adenosine clearance in the brain, 5-ITU, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), in a 10 mmol solution; kainic acid (10 mg/kg; KA, Sigma-Aldrich) in a 10 mg/ml solution; and caffeine (25 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) in a 10 mg/ml solution. DMSO and saline were used as vehicle (Veh) for 5-ITU and KA, respectively.

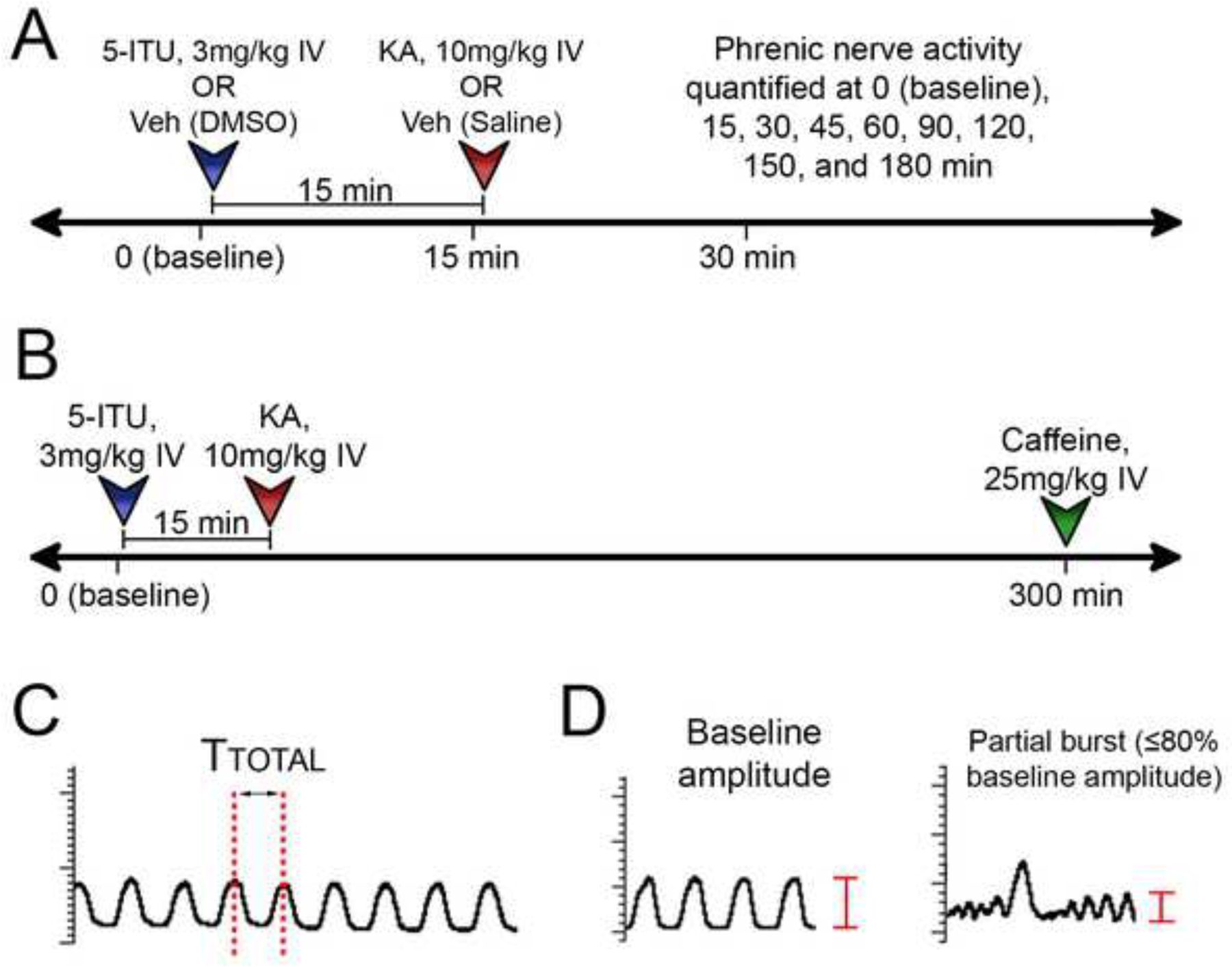

In our approach, we first applied the ADK antagonist 5-ITU, followed 15 minutes later by the infusion of KA to induce acute seizures (Fig. 1A). Phrenic nerve activity was assessed at 0 (baseline activity), 15 (time point of KA injection), 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 minutes after 5-ITU (or the first vehicle) injection. Experiments were performed in a 2 × 2 design with the four groups being: (1) ITU-KA (infusion of 5-ITU followed by KA, n=12), (2) Veh-Veh (infusion of DMSO followed by saline, n=6), (3) ITU-Veh (infusion of 5-ITU followed by saline, n=6), and (4) Veh-KA (infusion of DMSO followed by KA, n=6).

Figure 1. Experimental Timeline and Sample Traces.

(A) Injection timeline to assess phrenic nerve changes in response to pretreatment with 5-ITU and KA. 5-ITU is injected immediately after the baseline time point. KA is injected 15 minutes following 5-ITU. (B) Caffeine was injected at 300 min to determine reversibility of the phrenic nerve bursts changes in the ITU-KA group. (C) Graphical representation of interburst interval (Ttotal), the value used to determine phrenic nerve burst frequency, is the time (sec) from the peak of one discharge to another. (D) Aberrant partial nerve bursts were quantified by identifying nerve discharges that were ≤ 80% of the baseline burst amplitude.

A subset of rats (n=6) in the ITU-KA group underwent a longer observation period of 300 minutes. Half of these rats (n=3) were injected with caffeine at 300 minutes to evaluate the effects that adenosine receptor blockade would have on seizure induced depression of PNA (Fig. 1B).

2.5. Data and Statistical Analysis

Phrenic nerve activity was quantified by frequency. Frequency was determined by the interburst interval (Fig. 1C), denoted by Ttotal, the time from the peak of one dominant nerve discharge to another. Ten consecutive interburst interval values were calculated at each time point and averaged to determine the final nerve frequency per minute (60/Ttotal). Aberrant partial phrenic nerve bursts were quantified in all animals in the ITU-KA group at the 1-hour, 2-hour, and 3-hour timepoints (Fig. 1D). Ten seconds were sampled at each timepoint and used to quantify the partial nerve discharges per second. All frequencies are represented as a percent change from baseline. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 8.2.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California). Differences between four groups were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. Differences between two groups were analyzed using Mann-Whiteney U test or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. Statistical significance was considered p < 0.05. The values in this study are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

3. RESULTS

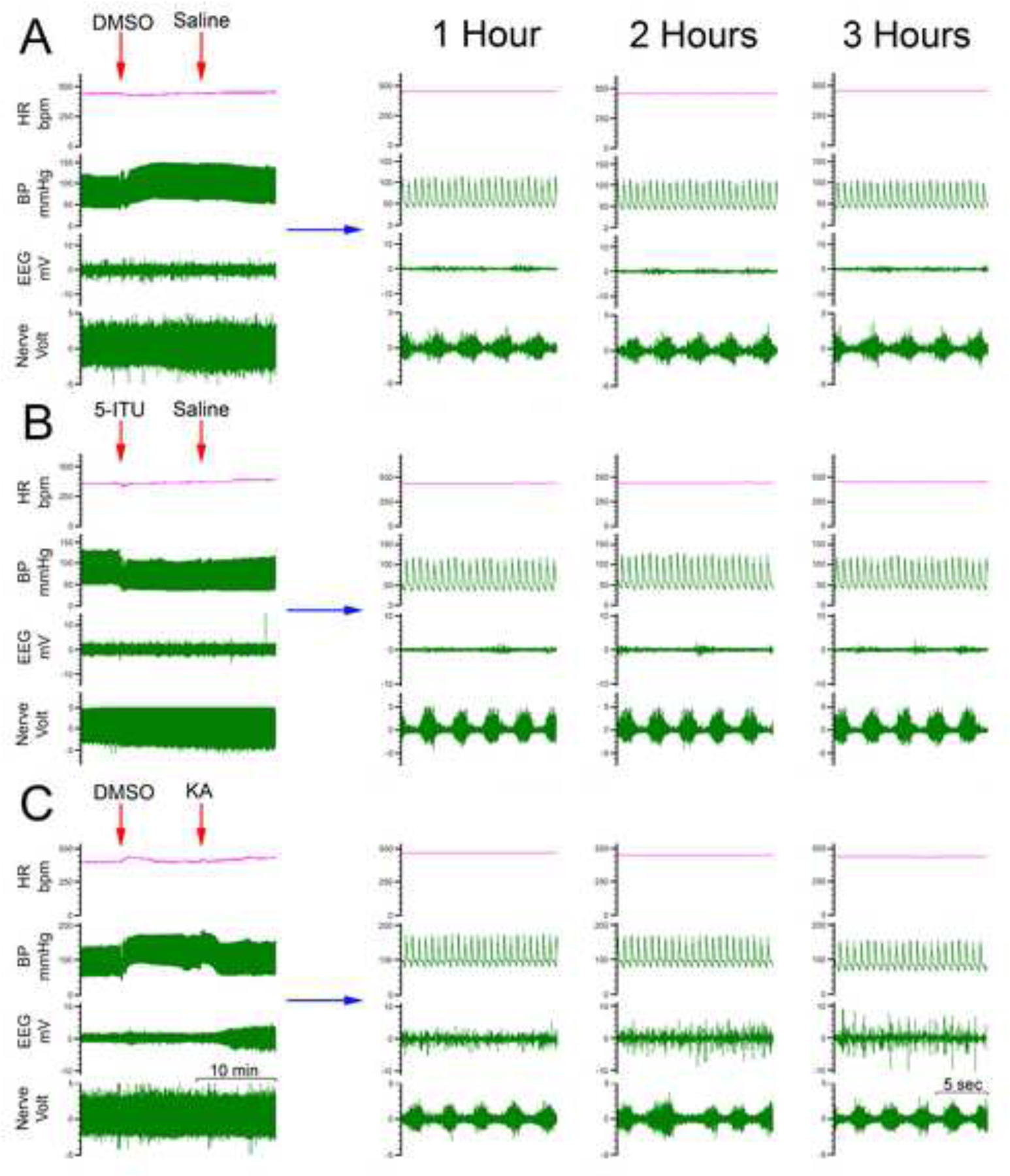

In order to study SUDEP and its mechanisms, it is beneficial to have a model system that allows for the simultaneous assessment of physiological parameters (EEG, heart rate, blood pressure, and PNA as indicator of respiration) in conjunction with the controlled induction of a SUDEP-like event. In line with the adenosine hypothesis of SUDEP (Richerson et al., 2016; Shen et al., 2010), we hypothesized that a combination of the ADK inhibitor 5-ITU in conjunction with a seizure triggered by KA would induce respiratory failure and death. Representative traces of heart rate, blood pressure, EEG and PNA from animals in the Veh-Veh, 5-ITU-Veh and ITU-KA groups are shown in Fig. 2A, 2B and 2C, respectively. Baseline parameters were noted prior to experimental manipulations such as vehicle/drug administration and are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2. Electrophysiologic and Hemodynamic Output Data.

(A) Representative traces of heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), EEG and PNA from a Veh-Veh subject, infused with DMSO followed by saline. Expanded EEGs are shown on the right before and after saline injection. (B) Identical parameters are shown in a rat pretreated with 5-ITU, followed by KA. The EEG shows increased activity approximately 25 minutes following IV infusion with KA. Expanded EEGs are shown on the right before and after KA injection. Expanded phrenic nerve burst activity on the right at 1 hour demonstrates distinct morphological changes in the rats pretreated with 5-ITU and KA, beginning typically at 50–60 min.

Table 1.

Baseline Animal Information

| Veh-Veh (n=6) | ITU-Veh (n=6) | Veh-KA (n=6) | ITU-KA (n=12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (grams) | 338.0 ± 7.2 | 331.2 ± 4.4 | 339.8 ± 10.2 | 348.6 ± 8.0 |

| Mean Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 76.2 ± 3.3 | 83.2 ± 2.9 | 80.5 ± 2.6 | 82.1 ± 2.1 |

| Pulse (beats per minute) | 424.7 ± 14.1 | 439.3 ± 8.6 | 427.7 ± 11.6 | 415.6 ± 11.5 |

| Frequency (bursts per second) | 1.51 ± 0.10 | 1.50 ± 0.08 | 1.60 ± 0.11 | 1.43 ± 0.16 |

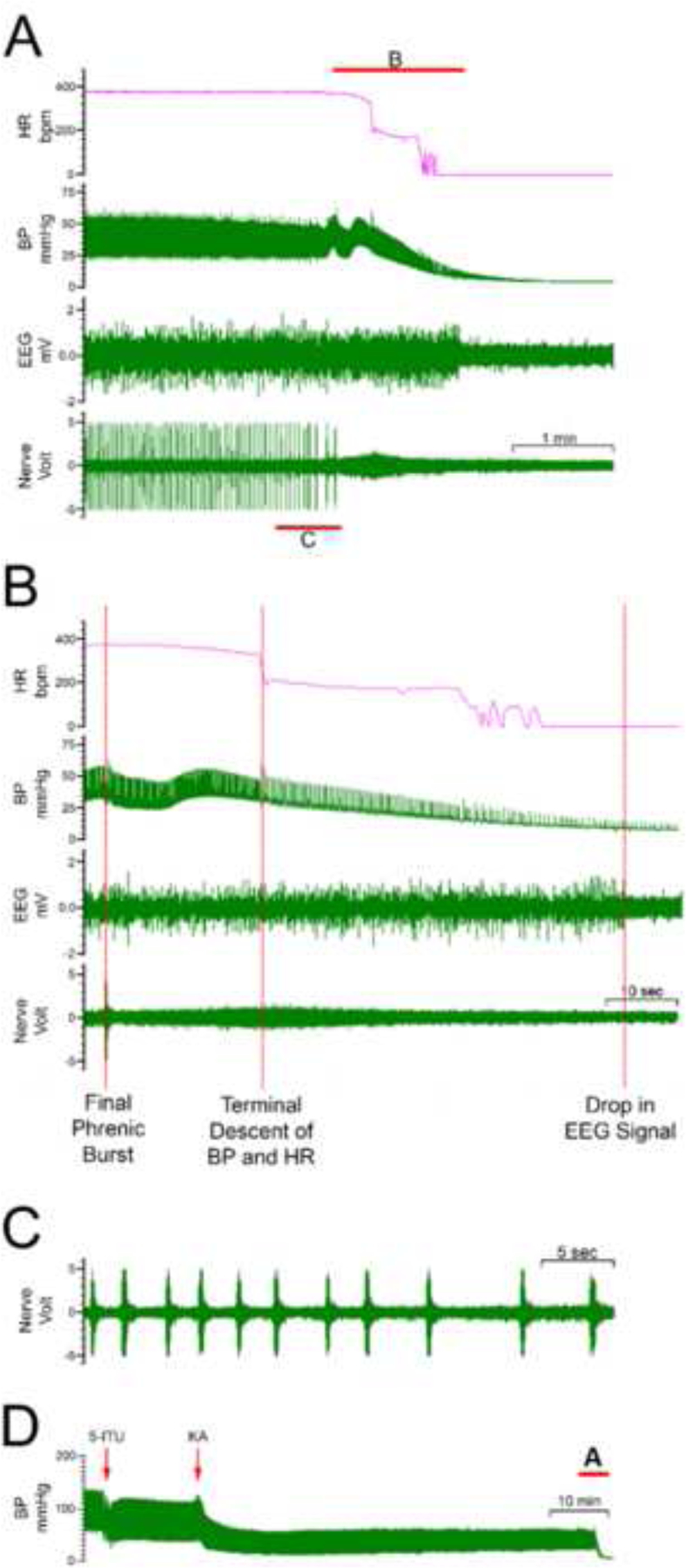

3.1. Adenosine-induced respiratory suppression can lead to sudden death

Two animals (16.7%) in the ITU-KA group died at approximately 80 and 110 min following 5-ITU injection, whereas no death was observed in animals given only KA, 5-ITU, or vehicle. A gradual decline in PNA was observed approximately 40–45 min following the injection of 5-ITU with associated changes in phrenic nerve burst activity (PNBA) morphology. As shown in Fig. 3 the following events preceded death. We found suppression of phrenic nerve activity (PNA) and irregularities, with the final phrenic burst occurring about 20 seconds before the terminal descent of blood pressure and heart rate, which led to cardiac arrest about 1 minute after the last phrenic nerve burst. Finally, EEG activity ceased about 10 seconds after cessation of cardiac activity. Although the injection of 5-ITU and KA caused a drop in BP from a baseline of ~80 mmHg (Figure 3D), a steady BP was maintained when changes in PNA were noted (Figure 3A–B). The drop in BP by 5-ITU and KA was consistent as noted in Figure 2B–C, however, the BP recovered to normal levels over time in the survival group which lacked abnormal PNA. Our observation that PNA starts to degrade before the BP drops supports our notion that irregularities and suppression of PNA constitute a predictive biomarker for SUDEP.

Figure 3. Seizure-induced Respiratory Failure.

(A) Two rats pretreated with 5-ITU and KA underwent death secondary to respiratory suppression. Shown is cessation of phrenic nerve activity, followed by loss of blood pressure and reduced EEG activity. In this illustrated case, death occurred at 80 min. (B) Expanded view, demonstrating the sequence of events that preceded death. The final phrenic nerve burst occurred approximately 20 seconds prior to the terminal descent of blood pressure and heart rate, which was followed by the drop in the EEG signal approximately 50 seconds later. (C) Shown is an expanded view of the phrenic nerve activity prior to seizure-induced respiratory death, demonstrating an increase in the phrenic nerve interburst distance prior to sudden loss of the signal. (D) Shown is the full trace of BP with a baseline blood pressure of ~ 80 mmHg. A drop in BP was noted following administration of both 5-ITU and KA injections. Red insert indicates the part of trace that is expanded in (A).

3.2. Suppression of phrenic nerve activity during seizures with concomitant inhibition of metabolic adenosine clearance

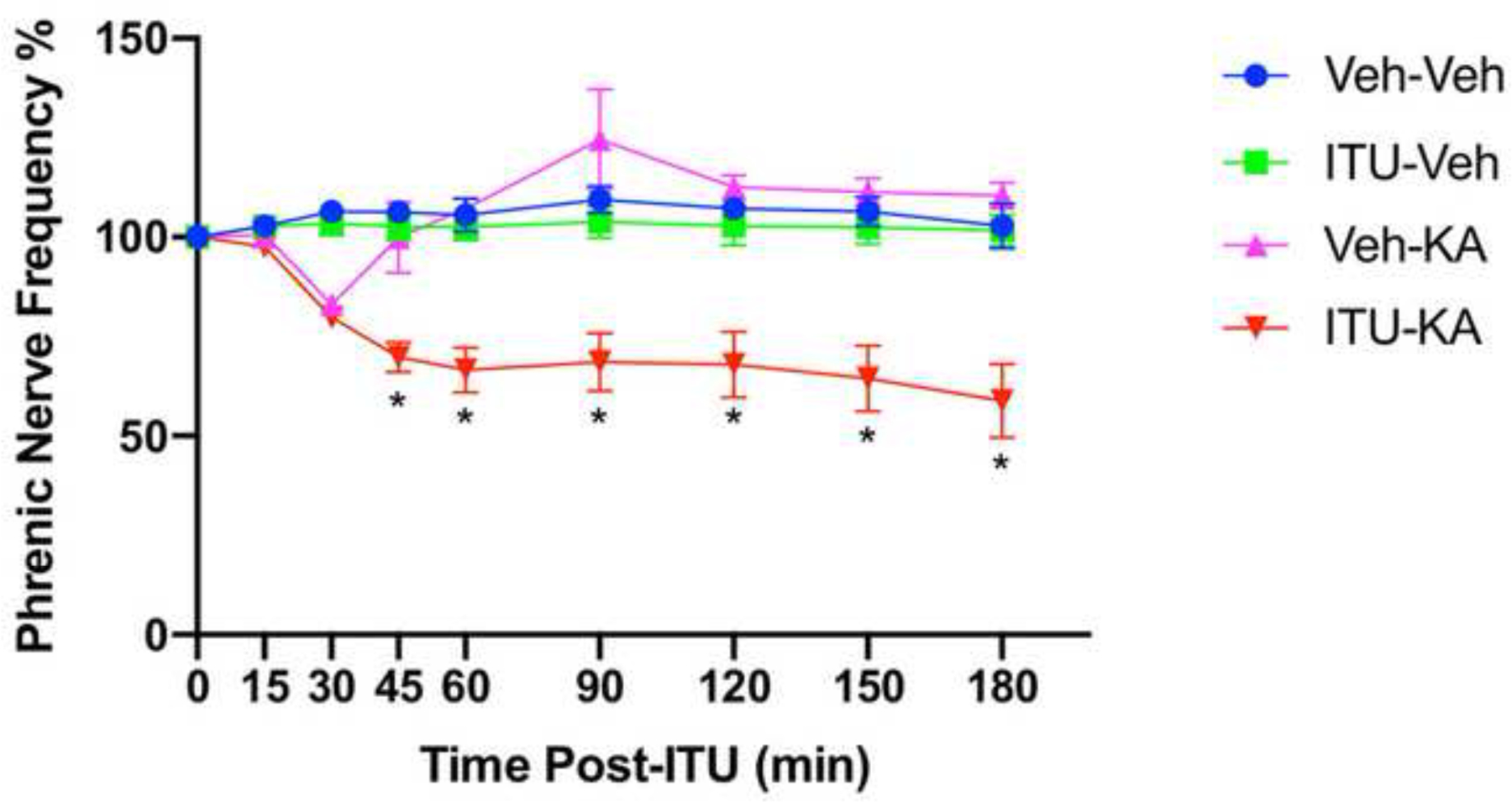

We compared PNA in: (1) animals subjected to a seizure in combination with 5-ITU (n = 12), (2) animals exposed to only a seizure (n = 6), (3) animals treated only with 5-ITU (n = 6), and (4) animals treated only with vehicle (n = 6). In the animals treated with both 5-ITU and KA, the phrenic nerve burst frequency was significantly reduced, ranging from 69.8 ± 3.7% (n = 12) at 45 min to 58.9 ± 9.3% at 180 min (n = 10), demonstrating sustained suppression over the duration of the recording period (p < 0.001 at each time point from 45 to 180 min; 45 min F (3, 26) = 14.49, 60 min F (3, 26) = 17.64, 90 min F (3, 25) = 10.56, 120 min F (3, 24) = 10.53, 150 min F (3, 24) = 11.78, 180 min F (3, 24) = 10.90; One-way ANOVA, confirmed with Tukey’s HSD). The initial drop in phrenic nerve burst frequency at 45 minutes was typically preceded by an increase in interictal epileptiform discharges (Fig. 3). In the group of animals that had KA-induced seizures without 5-ITU administration (Veh-KA), the phrenic nerve frequency initially dropped at 30 min (83.0 ± 2.4% of baseline, n = 6), but subsequently increased in activity at 90 min (124.6 ± 12.6% of baseline, n = 6), and trended back toward baseline values for the remaining duration of the observation period; however, none of these changes were statistically significant. Importantly, 5-ITU alone had no effect on phrenic nerve activity (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Phrenic Nerve Bursts Frequency Quantification.

Phrenic nerve bursts frequencies are shown for each of the 4 groups, represented as a percent of the baseline frequency measurement. Animals pretreated with 5-ITU and KA develop a significantly slower frequency starting at 45 minutes (69.8 ± 3.7% (n = 12) of the baseline measurement) of the baseline measurement, extending to the end of the 3-hour observation period (58.9 ± 9.3% (n = 10) of the baseline measurement); *p < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA).

3.3. Phrenic nerve burst activity morphology following 5-ITU and KA

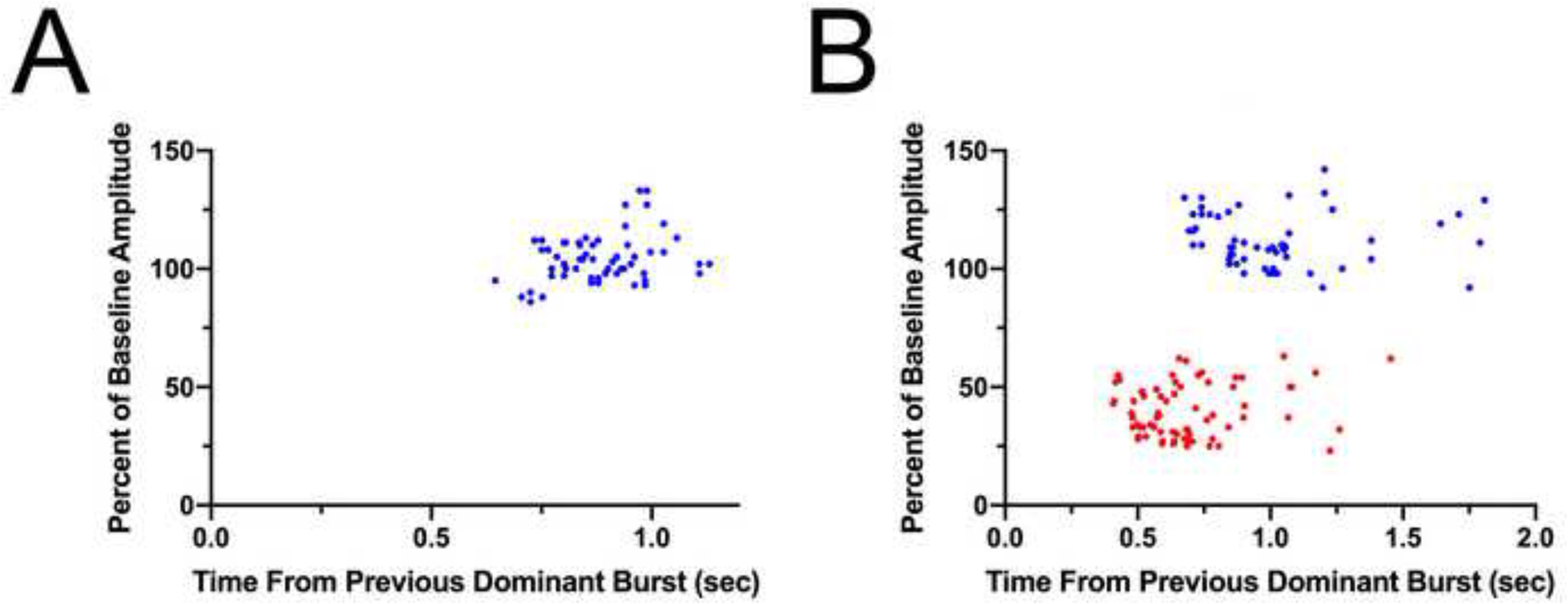

Given the distinct morphological changes we observed in the PNBA, we aimed to more closely evaluate the phrenic nerve discharge waveform. Phrenic nerve burst morphology was compared between: (1) animals injected with both 5-ITU and KA (n = 12), (2) those injected with only 5-ITU (n = 6), (3) only KA (n = 6), (4) and only vehicle (n = 6). An analysis of the phrenic nerve waveform in the ITU-KA group (Fig. 3) revealed multiple irregular smaller nerve discharges interspersed between large primary discharges. This morphological change manifested in 11/12 rats (91.7%) in the ITU-KA group. The smaller irregular bursts typically began at 50–60 min and were always preceded by seizure activity as detected by EEG. Quantification of the partial phrenic nerve bursts in the ITU-KA group demonstrated 1.01 ± 0.21 (n=12), 1.71 ± 0.26 (n=10), 1.87 ± 0.27 (n=10) bursts per second at the 1-hour, 2-hour, and 3-hour time points, respectively. In contrast, there were no changes of this kind observed in animals in the Veh-Veh, ITU-Veh, and Veh-KA groups. Further assessment of the partial phrenic nerve bursts in the ITU-KA group as a measure of amplitude as a percent of the baseline value, as well as the time from the previous dominant burst (dominant bursts were considered; those were ≥ 80% of the baseline amplitude) revealed two distinct populations of nerve discharges, those that are considered dominant bursts (blue), as well as aberrant partial nerve bursts (red) (Fig 5). Put together, these data indicate that the combination of impaired adenosine clearance and acute seizure activity is necessary to induce morphological changes in the phrenic nerve discharge waveform.

Figure 5. Evolution of Phrenic Nerve Burst Activity.

(A) For each animal in the ITU-KA group, a 5 second segment of the PNBA was analyzed at the 30 min timepoint, assessing both the amplitude as a percent of the baseline value as well as the time from the previous dominant burst (dominant bursts were considered those were ≥ 80% of the baseline amplitude). This demonstrated a uniform collection of phrenic nerve bursts.

(B) An identical analysis was carried out at the 60 min timepoint. This revealed two distinct populations of nerve discharges, those that are considered dominant bursts (blue), as well as aberrant partial nerve bursts (red).

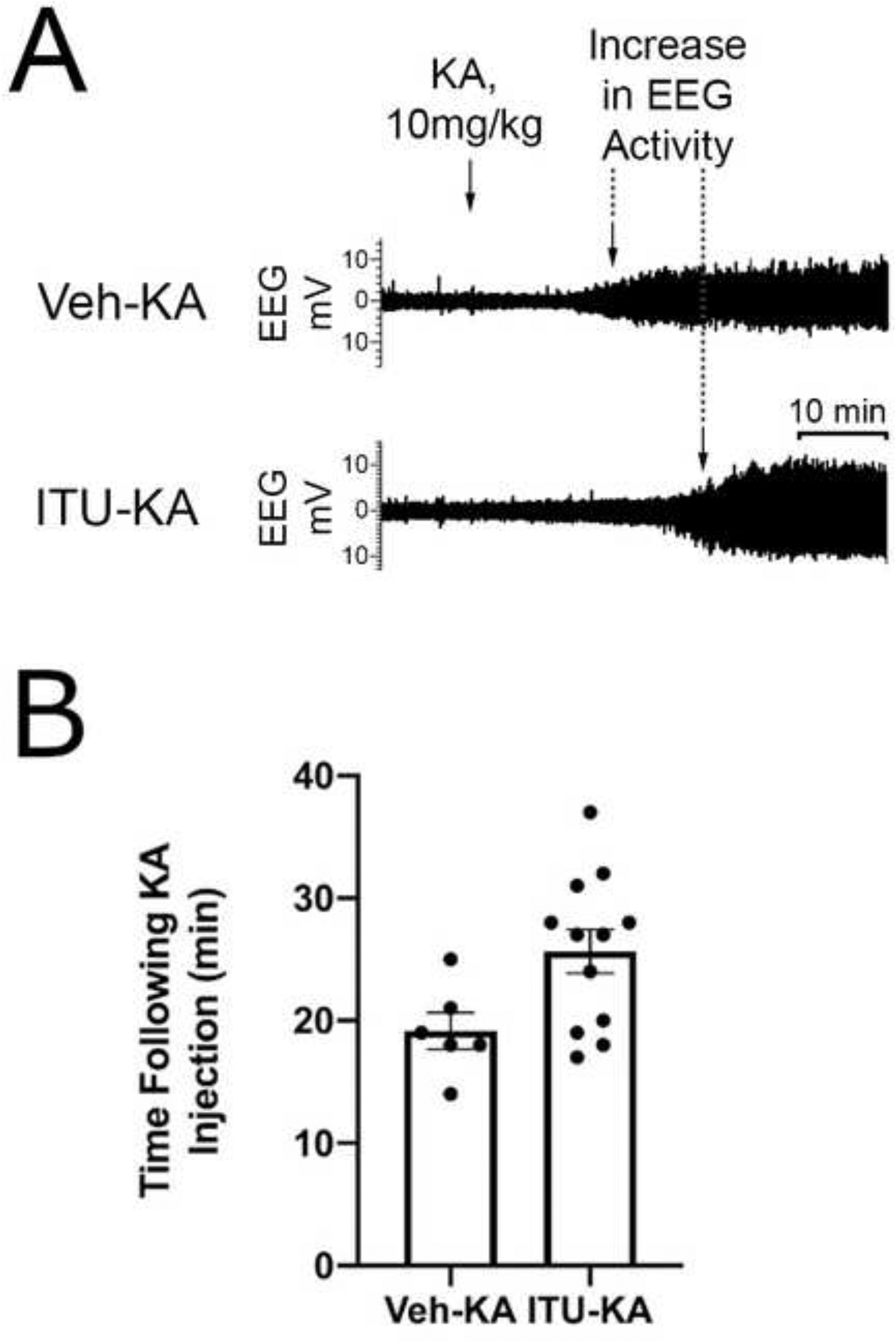

3.4. 5-ITU prolongs time to seizure onset

We hypothesized that rats pretreated with 5-ITU before KA administration would have a greater latency to seizure onset compared to rats pretreated with vehicle (Fig. 6A). Animals in the ITU-KA group (n = 12) had a significantly longer time to seizure onset compared to those in the Veh-KA group (n = 6) (25.67 ± 1.79 vs. 19.17 ± 1.49 minutes, respectively; Mann-Whitney U = 14.50, p = 0.044, Mann-Whitney U test, Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Effect of 5-ITU on Seizure Onset.

(A) EEG traces before and after KA injection characteristic of animals in the Veh-KA and ITU-KA groups. Rats injected with 5-ITU typically had a longer time to seizure onset following KA administration. (B) The average time to seizure onset was significantly longer in the animals pretreated with 5-ITU (n = 12) than in animals treated with vehicle (n = 6) (25.7 ± 1.5 vs 19.2 ± 1.8 minutes, respectively); Mann–Whitney U = 14.50, p = 0.044.

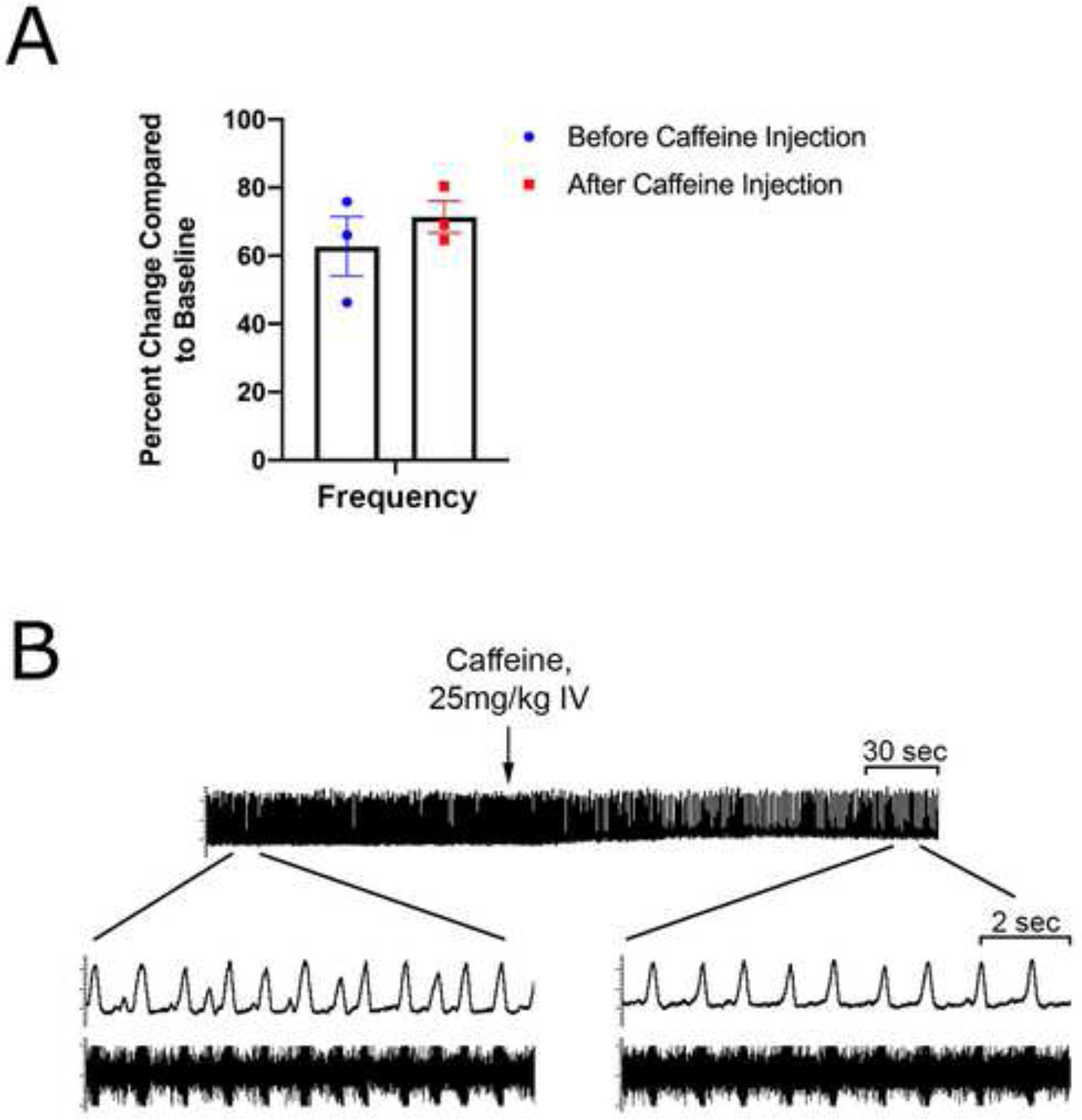

3.5. Caffeine reverses morphological changes in phrenic nerve activity

We intravenously injected caffeine (25 mg/kg) 300 minutes after baseline in rats pretreated with 5-ITU and KA (n = 3), and phrenic nerve activity and burst morphology was compared before and after caffeine administration. Caffeine injection resulted in an initial drop in burst frequency followed by a rebound increase 5 – 10 min after infusion. At 10 min, the frequency increased by 8.6% (Fig. 7A) though this change was not statistically significant (W = 0.400, p = 0.500, Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test). Furthermore, caffeine injection had reduced the PNBA abnormalities in the 3 rats, typically 3–4 minutes following caffeine infusion (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Effect of Caffeine on Abnormal Phrenic Nerve Activity.

(A) On average, caffeine injection at 300 min in rats pretreated with 5-ITU and KA (n = 3) caused an initial decrease in frequency followed by an increase of the frequency by 8.7% (from 62.7 ±8.7 % to 71.4 ± 4.7%) at 10 min following injection, though this change was not statistically significant; W = 0.400, p = 0.500 (Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test). (B) The phrenic nerve burst activity is shown 2 min prior and 3 min after caffeine injection. Caffeine improves morphological changes in the phrenic nerve burst activity induced by 5-ITU and KA.

4. DISCUSSION

The major findings of this studies are: (1) KA-induced seizures in combination with impaired adenosine clearance results in a potentially fatal suppression of phrenic nerve activity. (2) Suppression of phrenic nerve activity precedes cardiovascular failure and EEG flattening making it a potentially useful biomarker for impending seizure-induced death. (3) KA-induced seizures in combination with impaired adenosine clearance alters the waveform of phrenic nerve bursting by introducing smaller irregular partial bursts. (4) Caffeine administration reverses the changes in the waveform of phrenic nerve bursting but may not rescue burst frequency.

Our study is primarily directed at testing and further refining the adenosine hypothesis of SUDEP (Shen et al., 2010) towards potential development of a closed loop system for SUDEP prevention. Endogenous adenosine is released in response to seizure activity as a protective mechanism to promote seizure termination via A1 receptor activiation (Fedele et al., 2006). With widespread expression of A1 receptors in the hippocampus and cortical regions, A1 receptor mediated seizure termination is crucial to preventing seizures from evolving into status epilepticus (Kochanek et al., 2006; Swanson et al., 1995; Van Dort et al., 2009). A2A receptors are abundantly expressed on GABAergic neurons in the respiratory central pattern generators (Wilson et al., 2004; Zaidi et al., 2006). Increases in brainstem adenosine levels cause respiratory suppression (Barraco et al., 1990). Under normal circumstances, during respiratory suppression CO2 levels in the blood quickly rise and trigger the hypercapnic ventilatory response (Teran et al., 2014). Unfortunately, increased adenosine signaling blunts the hypercapnic ventilatory response potentially contributing to SUDEP (Falquetto et al., 2018). Adenosine levels in the brain and CO2 levels in the blood remain elevated long the end of a seizure (During and Spencer, 1992; Sainju et al., 2019). Possibly, elevated postictal adenosine levels suppress the hypercapnic ventilatory response in the postictal period and are causally related to the lasting increase in blood CO2 levels. Excessive activation of A2A receptors following a seizure may suppress breathing, arousal, and the hypercapnic ventilatory response in ways which potentiate SUDEP.

Our study demonstrates a progressive decrease in phrenic nerve burst frequency in animals with pharmacologically impaired adenosine metabolism following KA-induced seizures; this respiratory suppression was shown to trigger death in a subset of the animals in this group, although this data has to be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. It is important to note that the adenosine amplifying effects of the pharmacological inhibition of metabolism (via 5-ITU) and increased endogenous production (via KA-induced seizures) were necessary to induce phrenic nerve burst frequency suppression and waveform irregularities (partial phrenic nerve bursts). Neither, KA or 5-ITU alone elicited these changes. The aberrant partial phrenic nerve bursts seen in this investigation, to the best of our knowledge, have not been observed in the context of seizure activity or otherwise. However, the physiological relevance of these aberrant partial bursts remains unclear. The A2A receptor has a lower affinity for adenosine than the A1 receptor (130nM vs 70nM, respectively) (Dunwiddie and Masino, 2001). The lack of alterations in phrenic nerve activity in the Veh-KA group indicates that the surging of adenosine which occurs during a typical seizure is likely insufficient to activate the A2A receptors on GABAergic central pattern generator neurons in a way which significantly disrupts breathing. This finding parallels clinical data which indicate that SUDEP is unlikely to occur after any given seizure, but is rather a result of chronically uncontrolled seizures (Harden et al., 2017). This suggests that refractory epilepsy may result in maladaptive changes to adenosine signaling or metabolism, predisposing patients to SUDEP and warranting further investigation.

Existing literature suggests that respiratory arrest precedes cardiac failure and electrocerebral shutdown in SUDEP and is a subject of ongoing investigations. Recent reports demonstrate that seizure-induced death can be the result of a seizure-induced central apnea (Vilella et al., 2019a; Vilella et al., 2019b), whereas other studies implicate airway obstruction due to laryngospasm (Lacuey et al., 2018; Stewart et al., 2017). Tracheostomy in our experimental design eliminated the possibility of laryngospasm, reinforcing a central etiology as the causative factor. Our data illustrate that reduced phrenic nerve bursts occur prior to death due to respiratory failure, highlights the use of phrenic nerve recording as a way to predict an imminent SUDEP event. Taken together, these results indicate that death was due to central failure in respiratory drive as opposed to peripheral airway occlusion. When considering its clinical utility, phrenic nerve activity as a predictor for SUDEP is useful only so far as a therapeutic option exists to prevent seizure-induced respiratory arrest. Methylxanthines, particularly caffeine, have had encouraging results in preventing lethal apnea in neurological conditions such as TBI and apnea of prematurity, and have prolonged survival in mice with KA-induced seizures and inhibited adenosine metabolism. While caffeine administration in our study abrogated the partial bursts observed in PNA, there was not a significant difference in the change of PNBA frequency. In order to clearly interpret the restorative effect of caffeine, future investigations are needed to (1) clarify the conditions in which these partial bursts and PNBA abnormalities occur, (2) determine how these partial bursts are reflected in neuronal activity in the phrenic motor nucleus and (3) understand the relationship between these partial bursts and respiratory failure. Further work evaluating the optimal time and dosing for intervention may improve outcomes.

In this study, we demonstrate that non-fatal kainic acid induced-seizures precipitate a transient decrease in phrenic nerve activity. In contrast, fatal seizures were characterized by a decrease in PNA which worsened over time and concluded with respiratory arrest and death. Although it is unclear what factors differentiate those seizures, which result in death from the countless others that do not, our finding suggests that recording from the phrenic nerve could be used to identify imminent seizure-induced death after KA-induced status epilepticus. Seizure-induced respiratory disruption is known to cause rapid and lasting derangement of blood gasses (Bateman et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2018). Cardiovascular and respiratory chemoreflex responses to insufficient O2 and excessive CO2 are likely to be a critical lifesaving response during the postictal period (Massey et al., 2014). Interestingly, rats with chronic epilepsy due to kainic acid induced status epilepticus display normal chemoreflex responses to hypoxic and hypercapnic stimuli (Bhandare et al., 2017). It is conceivable that recent seizure activity, but not chronic epilepsy itself, causes chemoreflex disruption. If seizure-induced adenosine surging was responsible for chemoreflex disruption one would expect an alteration in the chemoreflex response to hypercapnia/hypoxia in the minutes to hours following seizures, but not necessarily any difference at the interictal baseline (During and Spencer, 1992). Furthermore, this prior study used urethane anesthesia which has been demonstrated to alter chemoreflex responses (Massey and Richerson, 2017). Taken together, we present the utility of phrenic nerve recording as a way to monitor central respiratory output and predict the likelihood of lethal seizure-induced apnea in an adenosine-centric model of SUDEP. Centrally-induced respiratory suppression has been established as a fundamental component contributing to SUDEP (Rheims et al., 2019; Ryvlin et al., 2013). As such, the investigation of biomarkers to detect respiratory activity is a crucial first step to enable the preemptive identification of an impending SUDEP event, opening the door for prompt therapeutic intervention.

One limitation in our study was that the experiments were conducted on animals under urethane anesthesia which may meaningfully impact experimental outcomes. In particular, urethane anesthesia has been previously shown to decrease breathing and the hypercapnic ventilatory response (Massey and Richerson, 2017). Furthermore, we utilized an acute seizure model to elicit SUDEP, whereas SUDEP in humans is typically a result of chronically uncontrolled seizures. A further limitation is the small sample size and lack of sufficient power to claim that suppression in PNA universally occurs prior to epilepsy-induced death. However, the fact that none of the survivors (10/12) showed PNA irregularities and that we were able to pick up those irregularities only in the small subset of animals that died (2/12) suggests that PNA irregularities might be a biomarker for imminent SUDEP, although further studies with significantly larger sample sizes would be needed to validate this conclusion. Despite these limitations our data provides evidence for the role that seizure-induced adenosine release plays in centrally-mediated respiratory depression in SUDEP. The combination of the ability to detect suppression of PNA as biomarker for imminent SUDEP, with an intervention (e.g. caffeine) my lead to the development of a closed loop system for SUDEP prevention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DB: NS065957, NS103740) and Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (DB, CURE Catalyst Award).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Barraco RA, Janusz CA, Schoener EP, Simpson LL, 1990. Cardiorespiratory function is altered by picomole injections of 5’-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine into the nucleus tractus solitarius of rats. Brain Res 507, 234–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman LM, Li CS, Seyal M, 2008. Ictal hypoxemia in localization-related epilepsy: analysis of incidence, severity and risk factors. Brain 131, 3239–3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoglio D, Amhaoul H, Van Eetveldt A, Houbrechts R, Van De Vijver S, Ali I, Dedeurwaerdere S, 2017. Kainic Acid-Induced Post-Status Epilepticus Models of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy with Diverging Seizure Phenotype and Neuropathology. Front Neurol 8, 588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandare AM, Kapoor K, Pilowsky PM, Farnham MM, 2016. Seizure-Induced Sympathoexcitation Is Caused by Activation of Glutamatergic Receptors in RVLM That Also Causes Proarrhythmogenic Changes Mediated by PACAP and Microglia in Rats. J Neurosci 36, 506–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandare AM, Kapoor K, Powell KL, Braine E, Casillas-Espinosa P, O’Brien TJ, Farnham MMJ, Pilowsky PM, 2017. Inhibition of microglial activation with minocycline at the intrathecal level attenuates sympathoexcitatory and proarrhythmogenic changes in rats with chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience 350, 23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitravanshi VC, Sapru HN, 1996. NMDA as well as non-NMDA receptors mediate the neurotransmission of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons in the adult rat. Brain Res 715, 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitravanshi VC, Sapru HN, 1999. Phrenic nerve responses to chemical stimulation of the subregions of ventral medullary respiratory neuronal group in the rat. Brain Res 821, 443–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitravanshi VC, Sapru HN, 2002. Microinjections of glycine into the pre-Botzinger complex inhibit phrenic nerve activity in the rat. Brain Res 947, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA, 2001. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci 24, 31–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- During MJ, Spencer DD, 1992. Adenosine: a potential mediator of seizure arrest and postictal refractoriness. Ann Neurol 32, 618–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmali AD, Bebek N, Baykan B, 2019. Let’s talk SUDEP. Noro Psikiyatr Ars 56, 292–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold CL, Randall M, Tupal S, 2010. DBA/1 mice exhibit chronic susceptibility to audiogenic seizures followed by sudden death associated with respiratory arrest. Epilepsy Behav 17, 436–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falquetto B, Oliveira LM, Takakura AC, Mulkey DK, Moreira TS, 2018. Inhibition of the hypercapnic ventilatory response by adenosine in the retrotrapezoid nucleus in awake rats. Neuropharmacology 138, 47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele DE, Li T, Lan JQ, Fredholm BB, Boison D, 2006. Adenosine A1 receptors are crucial in keeping an epileptic focus localized. Exp Neurol 200, 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden C, Tomson T, Gloss D, Buchhalter J, Cross JH, Donner E, French JA, Gil-Nagel A, Hesdorffer DC, Smithson WH, Spitz MC, Walczak TS, Sander JW, Ryvlin P, 2017. Practice guideline summary: Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy incidence rates and risk factors: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 88, 1674–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilie A, Raimondo JV, Akerman CJ, 2012. Adenosine release during seizures attenuates GABAA receptor-mediated depolarization. J Neurosci 32, 5321–5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry R, Sukato D, Kollmar R, Schild S, Silverman J, Sundaram K, Stephenson S, Stewart M, 2020. Seizures induce obstructive apnea in DBA/2J audiogenic seizure-prone mice: Lifesaving impact of tracheal implants. Epilepsia 61, e13–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LA, Thomas RH, 2017. Sudden death in epilepsy: Insights from the last 25 years. Seizure 44, 232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Bravo E, Thirnbeck CK, Smith-Mellecker LA, Kim SH, Gehlbach BK, Laux LC, Zhou X, Nordli DR Jr., Richerson GB, 2018. Severe peri-ictal respiratory dysfunction is common in Dravet syndrome. J Clin Invest 128, 1141–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek PM, Vagni VA, Janesko KL, Washington CB, Crumrine PK, Garman RH, Jenkins LW, Clark RS, Homanics GE, Dixon CE, Schnermann J, Jackson EK, 2006. Adenosine A1 receptor knockout mice develop lethal status epilepticus after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26, 565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacuey N, Vilella L, Hampson JP, Sahadevan J, Lhatoo SD, 2018. Ictal laryngospasm monitored by video-EEG and polygraphy: a potential SUDEP mechanism. Epileptic Disord 20, 146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lertwittayanon W, Devinsky O, Carlen PL, 2020. Cardiorespiratory depression from brainstem seizure activity in freely moving rats. Neurobiol Dis 134, 104628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Steinbeck JA, Lusardi T, Koch P, Lan JQ, Wilz A, Segschneider M, Simon RP, Brustle O, Boison D, 2007. Suppression of kindling epileptogenesis by adenosine releasing stem cell-derived brain implants. Brain 130, 1276–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovatt D, Xu Q, Liu W, Takano T, Smith NA, Schnermann J, Tieu K, Nedergaard M, 2012. Neuronal adenosine release, and not astrocytic ATP release, mediates feedback inhibition of excitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 6265–6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi TA, Lytle NK, Szybala C, Boison D, 2012. Caffeine prevents acute mortality after TBI in rats without increased morbidity. Exp Neurol 234, 161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey CA, Richerson GB, 2017. Isoflurane, ketamine-xylazine, and urethane markedly alter breathing even at subtherapeutic doses. J Neurophysiol 118, 2389–2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey CA, Sowers LP, Dlouhy BJ, Richerson GB, 2014. Mechanisms of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: the pathway to prevention. Nat Rev Neurol 10, 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer CA, Haxhiu MA, Martin RJ, Wilson CG, 2006. Adenosine A2A receptors mediate GABAergic inhibition of respiration in immature rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 100, 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheims S, Alvarez BM, Alexandre V, Curot J, Maillard L, Bartolomei F, Derambure P, Hirsch E, Michel V, Chassoux F, Tourniaire D, Crespel A, Biraben A, Navarro V, Kahane P, De Toffol B, Thomas P, Rosenberg S, Valton L, Bezin L, Ryvlin P, group R. M. s., 2019. Hypoxemia following generalized convulsive seizures: Risk factors and effect of oxygen therapy. Neurology 92, e183–e193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson GB, Boison D, Faingold CL, Ryvlin P, 2016. From unwitnessed fatality to witnessed rescue: Pharmacologic intervention in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia 57 Suppl 1, 35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryvlin P, Nashef L, Lhatoo SD, Bateman LM, Bird J, Bleasel A, Boon P, Crespel A, Dworetzky BA, Hogenhaven H, Lerche H, Maillard L, Malter MP, Marchal C, Murthy JM, Nitsche M, Pataraia E, Rabben T, Rheims S, Sadzot B, Schulze-Bonhage A, Seyal M, So EL, Spitz M, Szucs A, Tan M, Tao JX, Tomson T, 2013. Incidence and mechanisms of cardiorespiratory arrests in epilepsy monitoring units (MORTEMUS): a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 12, 966–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainju RK, Dragon DN, Winnike HB, Nashelsky MB, Granner MA, Gehlbach BK, Richerson GB, 2019. Ventilatory response to CO2 in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 60, 508–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HY, Li T, Boison D, 2010. A novel mouse model for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP): role of impaired adenosine clearance. Epilepsia 51, 465–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M, Kollmar R, Nakase K, Silverman J, Sundaram K, Orman R, Lazar J, 2017. Obstructive apnea due to laryngospasm links ictal to postictal events in SUDEP cases and offers practical biomarkers for review of past cases and prevention of new ones. Epilepsia 58, e87–e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson TH, Drazba JA, Rivkees SA, 1995. Adenosine A1 receptors are located predominantly on axons in the rat hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol 363, 517–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teran FA, Massey CA, Richerson GB, 2014. Serotonin neurons and central respiratory chemoreception: where are we now? Prog Brain Res 209, 207–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dort CJ, Baghdoyan HA, Lydic R, 2009. Adenosine A(1) and A(2A) receptors in mouse prefrontal cortex modulate acetylcholine release and behavioral arousal. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 29, 871–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilella L, Lacuey N, Hampson JP, Rani MRS, Loparo K, Sainju RK, Friedman D, Nei M, Strohl K, Allen L, Scott C, Gehlbach BK, Zonjy B, Hupp NJ, Zaremba A, Shafiabadi N, Zhao X, Reick-Mitrisin V, Schuele S, Ogren J, Harper RM, Diehl B, Bateman LM, Devinsky O, Richerson GB, Tanner A, Tatsuoka C, Lhatoo SD, 2019a. Incidence, Recurrence, and Risk Factors for Peri-ictal Central Apnea and Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy. Front Neurol 10, 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilella L, Lacuey N, Hampson JP, Rani MRS, Sainju RK, Friedman D, Nei M, Strohl K, Scott C, Gehlbach BK, Zonjy B, Hupp NJ, Zaremba A, Shafiabadi N, Zhao X, Reick-Mitrisin V, Schuele S, Ogren J, Harper RM, Diehl B, Bateman L, Devinsky O, Richerson GB, Ryvlin P, Lhatoo SD, 2019b. Postconvulsive central apnea as a biomarker for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Neurology 92, e171–e182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CG, Martin RJ, Jaber M, Abu-Shaweesh J, Jafri A, Haxhiu MA, Zaidi S, 2004. Adenosine A2A receptors interact with GABAergic pathways to modulate respiration in neonatal piglets. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 141, 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi SI, Jafri A, Martin RJ, Haxhiu MA, 2006. Adenosine A2A receptors are expressed by GABAergic neurons of medulla oblongata in developing rat. Brain Res 1071, 42–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]