Abstract

Background

Target temperature management (TTM) is suggested to reduce brain damage in the presence of global or local ischemia. Prompt TTM application may help to improve outcomes, but it is often hindered by technical problems, mainly related to the portability of cooling devices and temperature monitoring systems. Tympanic temperature (TTy) measurement may represent a practical, non-invasive approach for core temperature monitoring in emergency settings, but its accuracy under different TTM protocols is poorly characterized. The present scoping review aimed to collect the available evidence about TTy monitoring in TTM to describe the technique diffusion in various TTM contexts and its accuracy in comparison with other body sites under different cooling protocols and clinical conditions.

Methods

The scoping review was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR). PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science electronic databases were systematically searched to identify studies conducted in the last 20 years, where TTy was measured in TTM context with specific focus on pre-hospital or in-hospital emergency settings.

Results

The systematic search identified 35 studies, 12 performing TTy measurements during TTM in healthy subjects, 17 in patients with acute cardiovascular events, and 6 in patients with acute neurological diseases. The studies showed that TTy was able to track temperature changes induced by either local or whole-body cooling approaches in both pre-hospital and in-hospital settings. Direct comparisons to other core temperature measurements from other body sites were available in 22 studies, which showed a faster and larger change of TTy upon TTM compared to other core temperature measurements. Direct brain temperature measurements were available only in 3 studies and showed a good correlation between TTy and brain temperature, although TTy displayed a tendency to overestimate cooling effects compared to brain temperature.

Conclusions

TTy was capable to track temperature changes under a variety of TTM protocols and clinical conditions in both pre-hospital and in-hospital settings. Due to the heterogeneity and paucity of comparative temperature data, future studies are needed to fully elucidate the advantages of TTy in emergency settings and its capability to track brain temperature.

Keywords: Target temperature management, Hypothermia, Ear canal, Tympanic membrane, Cooling devices, Hearables, Cardiac arrest, Stroke, Physiological monitoring, Temperature

Background

Targeted temperature management (TTM), former therapeutic hypothermia, is an intentional reduction of core temperature to a selected and strictly controlled [1] range of values, which is aimed to improve outcomes in various clinical conditions, including cardiac arrest (CA), traumatic brain injury, stroke, and myocardial infarction [2–4]. By lowering brain temperature, TTM is thought to mitigate brain damage due to global (i.e., CA) or local (i.e., stroke) ischemia, through various mechanisms, including a decrease of cerebral oxygen and glucose consumption, and a reduction of ATP demand [5, 6]. Current guidelines and recent trials support the use of TTM (in the range of 32–36 °C [2, 3]) in all CA patients who remain in a state of coma after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) [2, 7–11]. The benefit of systemic and selective TTM in stroke patients is supported by recent trials and meta-analyses [12, 13]. Despite a broad consensus on TTM benefits, the application of pre-hospital TTM, for example in out-of-hospital CA, is still controversial [14, 15]. Variable outcomes have been reported [16–18], which may be partially due to limitations in pre-hospital cooling procedures and/or accuracy of temperature monitoring.

Since discrepancies between brain and systemic temperatures have been described, direct monitoring of brain temperature would be desirable for optimal TTM [19]. However, brain temperature measurement techniques are invasive and impractical in most cases and settings. Among different sites for core temperature measurement (e.g., ear canal, rectum, bladder, esophagus, and pulmonary artery) [20], the ear canal (or tympanic membrane) has been proposed as a surrogate measurement site during TTM procedures, especially in pre-hospital and emergency settings, thanks to its accessibility, minimal invasiveness, and fast response. The vasculature pattern of the tympanic membrane is shared with the brain and mediates a thermal equilibrium between the two sites [21–23], which suggests the potential of tympanic temperature (TTy) to reflect brain temperature. In addition, the vasculature in the tympanic region is minimally influenced by the thermoregulatory vasomotor response, which guarantees adequate flow conditions [24]. In pre-hospital settings, TTy has been shown—albeit with mixed results—to be comparable to invasive temperature measurements at hospital admission [20], providing that insulation from the environment is ensured during measurement [25]. On the other hand, TTy measurement can only be performed if the ear canal is not obstructed (e.g., by blood, cerumen, snow) [20]. TTy can be biased in situations during which blood flow is absent or inadequate [23, 26], and/or it can be affected by anatomical and vascular changes following major ear surgery and large tympanic membrane perforations [27]. TTy accuracy under different TTM protocols (e.g., local versus whole body), TTM phases (e.g., induction versus maintenance), and different pathophysiological conditions need to be further clarified.

This scoping review aims to identify and to summarize all the available evidence over the last 20 years about TTy monitoring in the context of TTM from studies performed either in patients with various acute disorders or in healthy subjects. We describe the level of diffusion of the techniques in various TTM contexts with a focus on pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency settings. We provide indications on the accuracy of tympanic measurements in comparison to other body sites under different TTM phases, cooling protocols, and clinical conditions.

Methods

The scoping review was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [28].

Eligibility criteria

The literature search was performed by two authors (AM and MM) to identify studies, conducted in the last 20 years, that used TTy during TTM approaches. The search strategy is schematized by the inclusion criteria in Table 1, categorized according to the broad Population-Concept-Context (PCC) mnemonic, recommended for scoping reviews [29, 30]. The scoping review was focused on pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency settings. We considered both studies testing TTM approaches in healthy subjects and studies where TTM was performed in patients experiencing different emergency conditions. Studies about accidental hypothermia, drug-induced hypothermia, and perioperative and postoperative hypothermia were excluded. The range of TTM temperatures was set to 32–36 °C according to TTM definition in [2, 3], while studies on normothermia maintenance in patients with fever were not considered. The search was restricted to articles published in English in peer-reviewed journals. No restriction on study design was posed. Abstracts presentations, conference proceedings, and reviews were excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for the scoping review summarized according to the Population-Concept-Context (PCC) mnemonic, recommended for scoping reviews [29, 30]

| Population |

• Healthy adults (testing of target temperature management approaches). • Patients undergoing target temperature approaches under emergency conditions, including cardiovascular and neurologic emergencies. • Any gender. |

| Concept | • Tympanic temperature measurement in the context of target temperature management. |

| Context |

• Testing of target temperature management approaches in healthy subjects; target temperature management in patients in pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency settings. • Original peer-reviewed research articles (any study design), published in English in the last 20 years. |

Information sources, search strategy, and study selection

A systematic search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, and ISI Web of Science electronic databases to identify primary references from January 2000 to April 2020. The following search strings were used: (“aural” OR “tympanic” OR “epitympanic” OR “ear” OR “ear canal” OR “in-ear” OR “ear-in” OR “earbud” OR “earpiece” OR “earable”) AND (“temperature” OR “temperature monitoring” OR “core temperature” OR “core body temperature” OR “body temperature”) AND (“hypothermia” OR “hypothermic” OR “therapeutic hypothermia” OR “hypothermic treatment” OR “target temperature management” OR “TTM” OR “body cooling” OR “low temperature” OR “low body temperature”). The database search was followed by a review of the citations from eligible studies. Studies were selected based on title and abstract using the online platform Rayyan [31]. Selected studies were read thoroughly to identify those suitable for inclusion in the scoping review.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (MM and AM) independently extracted the demographic and experimental data from the selected studies. When disagreement occurred, they reviewed the papers together to reach consensus. For each study, the following relevant information was extracted and summarized: the characteristics of the investigated study population; TTM protocols (body cooling modality, target temperature); the experimental and/or clinical settings of application; the available temperature measurements (presence and location of comparative/reference temperature measurements in addition to the tympanic one); and the main results of the studies in terms of feasibility of the tympanic measurements and comparability of TTy with core temperature measurements from other body sites.

Results

Selected studies

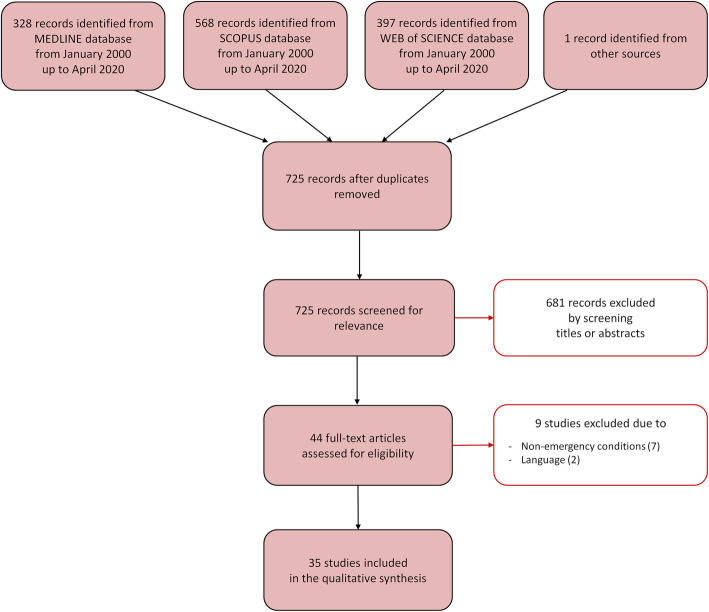

The database search identified a total of 725 relevant references once duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). A total of 681 references were excluded after reading title and abstract and 44 were retrieved for further evaluation. Of these, 9 studies were excluded, because they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria. Following the selection process, 35 studies were included in the scoping review. Of these studies, 12 measured TTy during tests of TTM protocols in healthy subjects, 17 during TTM in patients with acute cardiovascular events, and 6 during TTM in patients with acute neurological disorders. The studies are described in the next paragraphs and summarized in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Fig. 1.

Selection process for the studies included in the scoping review. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram depicts the number of records identified, included, and excluded, and the reasons for exclusion, through the different phases of the scoping review

Table 2.

Studies testing different approaches of target temperature management in healthy subjects.

| Study | Population | Cooling approach | Tympanic TM device | Core TM sites | Other TM sites | Main results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Protocol | Feasibility | Comparability | |||||

| Bagić et al. [32] |

N: 10 Age: [21–47] y Male: 50% |

Head and neck cooling | Cooling session lengths: 30 and 60 min. Cooling device T: 1.5 to 4.5–5 °C. | IRTT, Braun PRO 3000 Thermometer, Braun GmbH, Germany; TTy measured in both ears. | Intestinal pill | Scalp, forearm, abdomen, leg, face, and mouth | In both ears, TTy displayed significant differences between the start and end of cooling (p < 0.001). | A significant difference was observed in scalp T (p < 0.001), but not in intestinal T (p = NS). |

| Kallmünzer et al. [33] |

N: 10 Age: 35 (28–42) y Male: 60% |

Neck cooling |

Cooling session length: 190 min Cooling device T: 4 °C. |

IRTT, Genius 2, Tyco Healthcare Group, USA | Rectal | None | TTy displayed a significant drop after neck cooling (−1.7 °C, p = 0.001). | Rectal T displayed a smaller decrease (−0.65 °C, p = 0.019). |

| Koehn et al. [34] |

N: 11 Age: 42 ± 11 y Male: 45% |

Neck cooling |

Cooling session length: 90 min. Cooling device T: 4 °C. |

Thermocouple thermometer, ELan Med GmbH, Germany | Rectal | Neck skin | TTy showed a slight but significant decrease (from 35.6 ± 0.2 °C to 35.0 ± 0.8 °C, p = 0.026) within 10 min of cooling, reaching minimal values (34.7 ± 0.4 °C, p < 0.001) after 50 min | Neck skin and rectal T decreased respectively by a higher and lower extent than TTy. |

| Koehn et al. [35] |

N: 10 Age: 35 ± 13 y Man: 100% |

Head and neck cooling |

Cooling session length: 120 min Cooling device T: 4 °C. |

Thermocouple thermometer, ELan Med GmbH, Germany | Rectal | Forehead skin | TTy decreased to minimal values (from 36.6 ± 0.7 °C to 31.8 ± 1.2 °C, p < 0.001) after 40 min of cooling, with a slow increase thereafter. | Forehead skin and rectal T achieved the respective lowest values at 20 and 120 min, respectively. |

| Zweifler et al. [36] |

N: 22 Age: 31 ± 8 y Male: 45% |

Chest and thighs cooling |

Active cooling plus hypothermia maintenance: < 5 h. TT: 34–35 °C (tympanic). Shivering suppression by meperidine, buspirone, and MgSO4. |

Thermocouple thermometer, Mon-a-Therm, Mallinckrodt Anesthesia Products, USA; ear canal occluded with cotton and gauze, ear probe taped in place. | Rectal | None | TTy reached the TT=35 °C in a median time of 88 min (mean cooling rate of 1.4 ± 0.5 °C/h). | A time-dependent gradient was observed between TTy and rectal T (from −0.1 ± 0.3 °C at baseline to −0.6 ± 0.4 °C at 105 min, −0.3 ± 0.5 °C at maintenance phase). |

| Zweifler et al. [37] |

Intervention 1: N: 8 Age: 33 ± 8 y Male: 37% Intervention 2: N: 14 Age: 30 ± 9 y Male: 36% |

Chest and thighs cooling |

Active cooling plus hypothermia maintenance: < 5 h. TT: 34–35 °C (tympanic). Shivering suppression by meperidine, buspirone, or ondansetron, with (intervention 1) or without MgSO4 (intervention 2). |

Thermocouple thermometer, Mon-a-Therm, Mallinckrodt Anesthesia Products, USA; ear canal occluded with cotton and gauze, ear probe taped in place. | Rectal | None | Baseline TTy was 36.8±0.2 °C in intervention 1 and 37.0±0.3 °C in intervention 2. TTy depicted the prolongation of cooling time induced by meperidine (delay of 36 min, p = 0.003, for each 50 mg of drug) and the reduction of cooling time by MgSO4 (17 min, p = 0.039). | Baseline rectal T was 37.0±0.2 °C in intervention 1 and 37.0±0.3 °C in intervention 2. |

| Zweifler et al. [38] |

Intervention 1: N: 5 Age: 36 ± 5 y Male: 60% Intervention 2: N: 5 Age: 30 ± 11 y Male: 20% |

Intervention 1: Chest and thighs cooling Intervention 2: Thighs, back, and abdomen cooling |

Intervention 1: Active cooling plus hypothermia maintenance: < 5 h. TT: 34–35 °C (tympanic). Intervention 2: Active cooling plus hypothermia maintenance: < 5 h. TT: 34.5 °C (rectal). In both, shivering suppression by meperidine, or chlorpromazine |

Thermocouple thermometer, Mon-a-Therm, Mallinckrodt Anesthesia Products, Inc, USA. | Rectal | Mean skin-surface T from calf, thigh, chest, and upper arm skin. | TTy reached the TT=35 °C in 77 ± 23 min (mean cooling rate of 1.5 ± 0.6 °C/h) in Intervention 1 and in 90 ± 53 min (mean cooling rate of 1.4 ± 0.4 °C/h) in Intervention 2. | Rectal T displayed higher values than TTy over the cooling procedure in intervention 2. |

| Mahmood et al. [39] |

N: 18 Age: 32 ± 8 y Male: 44% |

Chest and thighs cooling |

Active cooling plus hypothermia maintenance: ≤ 5 h. TT: 34.5 °C (tympanic). Shivering suppression by meperidine and/or ondansetron and/or buspirone. |

NR | Rectal | None | TTy changes correlated with the mean flow velocity of the middle cerebral artery (p < 0.001). | At baseline TTy was 36.9 ± 0.3 °C, while rectal T was 37.0 ± 0.2 °C. |

| Adams and Koster [40] |

N: 10 Age: > 18 y Male: 50% |

Face and neck cooling | Device application at ambient T of 19 °C. | IRTT, Genius 3000A, Sherwood-Davis & Geck, Gosport UK | None | None | TTy showed a difference of 0.433 °C (p < 0.0001) between baseline and end of cooling exposure. | NR |

| Doufas et al. [41] |

N: 10 Age: 24 ± 4 y Male: 100% |

Whole body cooling by lactated Ringer’s solution (~4 °C) | Lactate infusion to decrease TTy by 1–2 °C/h until identification of the shivering threshold. Conditions tested: no drug, dexmedetomidine and/or meperidine. | Thermocouple thermometer, Mon-a-Therm, Mallinckrodt Anesthesiology Products, Inc., Ireland; ear canal occluded with cotton, probe taped in place, bandage over the ear. | None | Mean skin surface T from 15 area-weighted sites. | TTy detected the significant (p < 0.001) reduction of the shivering threshold induced by meperidine (drop of 1.2°C), dexmedetomidine (0.7 ± 0.5 °C), and their combination (2.0 ± 0.5 °C). | NR |

| Jackson et al. [42] |

N: 12 Age: 27 ± 11 y Male: 42% |

Head and neck cooling |

Cooling session length: 90 min. Cooling device settings: (i) maximum cooling; (ii) bypass mode in each participant. |

IRTT, Genius 2, Tyco Healthcare Group, USA | None | Sublingual |

In condition (i), TTy decreased from 37.01 ± 0.34 °C to 36.70 ± 0.38 °C (60 min) and to 36.76 ± 0.33 °C (90 min). In (ii), TTy decreased to a smaller extent, from 36.93 ± 0.30 °C to 36.85 ± 0.29 °C (60 min) and 36.85 ± 0.27 °C (90 min). |

Sublingual T showed a slower response. In (i), it decreased from 36.80 ± 0.14 °C to 36.70 ± 0.10 °C (60 min) and to 36.70 ± 0.12 °C (90 min). In (ii), it decreased from 36.74 ± 0.12 °C to 36.72 ± 0.11 °C (60 min) and 36.71 ± 0.08 °C (90 min). |

| Wadhwa et al. [43] |

N: 9 Age: 27 [18–40] y Male: 100% |

Whole body cooling by lactated Ringer’s solution (~4 °C) |

Lactate infusion via central venous catheter for 2 h to decrease TTy by ≈1.5 °C·h−1. Condition tested: intravenous MgSO4 (bolus of 80 mg·kg−1 plus infusion of 2 g·h−1), or an equal volume of saline solution. |

Thermocouple thermometer, Tyco-Mallinckrodt Anesthesiology Products, Inc, USA; ear canal occluded by cotton and gauze. | None | Skin surface |

TTy detected a significant reduction of the shivering threshold (0.3 ± 0.4 °C, p = 0.040) by MgSO4 infusion. TTy was 36.6 ± 0.2 °C after 30 min of MgSO4 infusion vs. 36.8 ± 0.3 °C after 30 min of saline solution infusion. |

Skin T was 33.2 ± 0.7 °C after 30 min of MgSO4 infusion vs. 33.6 ±1.3 °C after 30 min of saline solution infusion. |

Data are numbers (N), percentages (%), mean ± standard deviation, or [range], as available. HR, heart rate; IRTT, infrared tympanic thermometer; MgSO4, magnesium sulfate; NR, not reported; TTy, tympanic temperature; T, temperature; TM, temperature measurement: TT, target temperature; vs., versus; y, years

Table 3.

Studies performing target temperature management in acute cardiovascular events

| Study | Pathology | Population | Cooling approach | Setting | Tympanic TM device | Core TM sites | Other TM sites | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feasibility | Comparability | ||||||||

| Busch et al. [44] | CA |

N: 84 Age: 71 (63; 79) y Male: 76% |

Post-ROSC trans-nasal cooling. TT: 33 °C (tympanic and esophageal). |

ED/ ICU | IRTT, ThermoScan Pro 4000, Braun GmbH, Germany | Esophageal, or arterial, or bladder, or rectal | None | TTy displayed a cooling rate of 2.3 (1.6; 3.0) °C/h. The cooling time to reach the tympanic TT was 60 (36.5; 117.5) min and was reached in 66% of pts. | The cooling rate of overall core sites (esophageal, arterial, bladder, or rectal) was 1.1 (0.7; 1.5) °C/h, with a faster response for esophageal or arterial (1.4 (0.9; 2.0) °C/h) than for bladder or rectal (0.9 (0.5; 1.2) °C/h; p=0.001). The cooling time to reach the core TT was 180 (120; 285) min and was reached in 19% of patients. |

| Callaway et al. [45] | OHCA |

Intervention: N: 9 Age: 68 ± 15 y Male: 100% Control: N: 13 Age: 80 ± 10 y Male: 71% |

Intervention: intra-arrest head and neck cooling. TT: 34 °C (esophageal). Control: standard care. |

PH/ ED | IRTT, NR. | Esophageal | Naso-pharyngeal | TTy displayed unpredictable variations due to ice in the ears. | NR |

| Castren et al. [46] | OHCA |

Intervention: N: 93 Age: 66 y Male: 72% Control: N: 101 Age: 64 y Male: 78% |

Intervention: intra-arrest trans-nasal cooling. TT: 34 °C (tympanic and core). Control: standard care. |

PH | IRTT, NR | Rectal, or bladder, or intravascular | None | TTy at hospital arrival was significantly different (p<0.001) in intervention (34.2±1.5 °C) vs. control (35.5±0.9 °C). The cooling rate was 1.3 °C in 26 min. The cooling time to reach the tympanic TT was significantly shorter (p=0.03) in the intervention (102 (81; 155) min) vs. the control (291(183; 416) min) group. | Core T (rectal, or bladder, or intravascular) at admission was 35.1±1.3 °C in intervention vs. 35.8 °C ± 0.9 °C in control (p<0.01). Cooling time to reach the core TT was 155 (124; 315) min in the intervention vs. 284 (172; 471) in the control group. |

| Hasper et al. [47] | OHCA |

N: 10 Age: 71.5 y§ Male: 80% |

Post-ROSC whole body cooling by cold saline infusion and water pads. TT: 33 °C (NR). |

ED | IRTT, Braun ThermoScan pro4000; Welch Allyn, Germany | Esophageal, or bladder | None | During TTM TTy was 33.40 {33.30; 33.60} °C. | TTy displayed a small bias with respect to esophageal T (0.021 °C ± 0.80 °C) and a high significant correlation with esophageal (r=0.95, p<0.0001) and bladder T (r=0.96, p<0.0001). |

| Hachimi-Idrissi et al. [48] | OHCA |

Intervention: N: 16 Age: 77 [52; 95] y Male: 56% Control: N: 14 Age: 74 [59; 91] y Male: 64% |

Intervention: head and neck cooling. TT: 34 °C (bladder). Control: standard care. |

ED | IRTT, Braun Thermoscan, Braun, Germany | Central venous, arterial, or bladder | Scalp | The cooling time to reach the tympanic TT in intervention was 60 (15; 240) min. | The cooling time to reach the bladder TT was longer, 180 (70; 240) min (p = NR). |

| Islam et al. [49] | OHCA |

Intervention: N: 37 Age: 64 ± 12 y Male: 86% Control: N: 37 Age: 62 ± 13 y Male: 74% |

Intervention: post-ROSC intra-nasal cooling. TT: 34 °C (tympanic and esophageal). Control: standard surface-cooling. TT: 34 °C (tympanic and esophageal). |

CL by direct admission | NR | Esophageal | None |

In the first cooling hour, TTy showed a significantly larger drop (1.75 °C) in intervention vs. control (0.935 °C, p<0.01). The cooling time to reach the tympanic TT was 75.2 min in intervention vs. 107.2 min in control (p=NS). |

Esophageal T drop in the first hour was not significantly different in intervention (1.148 °C) vs. control (0.904 °C, p = NS). The cooling time to reach the esophageal TT was 84.7 min in intervention vs. 114.9 min in control (p=NS). |

| Krizanac et al. [50] | OHCA |

N: 20 Age: 63 (43; 88) y Male: 80% |

Post-ROSC cooling by cooling pads, or intravascular cooling catheters and intravenous cold saline infusion. TT: 33 °C (esophageal). |

ED | Thermistor thermometer, Mon-a-Therm, Tyco Healthcare, UK. | Esophageal, bladder, pulmonary artery, or femoral-iliac artery | None | TTy tracked temperature changes induced by cooling but continuously and substantially underestimated the pulmonary artery T during cooling as well as during steady state. | The bias of TTy compared to pulmonary artery T were -0.6 {−0.8; −0.3} °C (overall) and −0.6 {−0.8; −0.4}°C (cooling phase). The tympanic TT was reached with an anticipation of −38 {−65; −23.5} min compared to the pulmonary artery. |

| Shin et al. [51] | OHCA |

N: 21 Age: 50 ± 20 y Male: 71% |

Post-ROSC cooling by cold saline infusion and external cooling pads. TT: 33 °C (bladder). |

ED | Thermistor thermometer, Probe 400 Series, DeRoyal, USA; inserted after otoscopic exam, taped in place, covered with bandage. | Rectal, bladder, or pulmonary artery | None | TTy tracked the changes induced by cold saline cooling, but it underestimated pulmonary artery T through the whole procedure. | The bias$ of TTy compared to pulmonary artery was: −1.03 ± 1.47 °C (overall), −1.11 ± 1.53 °C (induction phase), −1.12 ± 1.29 °C (maintenance phase), and −0.89 ± 1.62 °C (rewarming phase). The correlation was: 0.860 (overall), 0.815 (induction phase), 0.611 (maintenance phase), and 0.776 (rewarming phase). |

| Stratil et al. [52] | CA |

Winter group (outside T ≤ 10 °C): N: 61 Age: 60 (50; 75) y Male: 70% Summer group: (outside T ≥ 20 °C): N: 39 Age: 57 (48; 65) y Male: 77% |

Mild therapeutic hypothermia by surface or invasive cooling in 25 winter and 24 summer patients. TT: <34 °C (NR). |

ED | IRTT, Ototemp LighTouch; Exergen, USA; only at admission. | Bladder, or esophageal | None | TTy at hospital admission was significantly lower (p=0.001) in winter (34.9 °C (34; 35.6)) vs. summer group (36 °C (35.3–36.3)). | Core T at admission was 35.3 °C (34.8; 35.9) in winter vs. 36.2 °C (35.5–36.7) in summer group (p = 0.001). |

| Takeda et al. [53] |

CA (mainly OHCA) |

Intervention: N: 53 Age: 72 (62; 81) y Male: 47% Control: N: 55 Age: 72 (64; 78) y Male: 67% |

Intervention: pre- or post-ROSC pharyngeal cooling plus whole body cooling. TT: 32 °C (tympanic). Control: standard care. |

ED | Thermistor thermometer, TM400, Covidien, Japan; TTy measured bilaterally, insulation with adhesive wrapping material. | Rectal, or bladder | None | In intervention TTy showed a drop of 0.06 °C/min in the first 10 min after arrival, followed by a slower decrease. TTy was significantly lower in intervention vs. control at 40 min (33.7 ± 1.4 °C vs. 34.1 ± 1.1 °C, p = 0.02) and 120 min (32.9 ± 1.2 °C vs. 34.1 ± 1.3 °C, p < 0.001). | Core T dropped by 0.02 °C/min at 30 min after arrival. Core T was significantly lower in intervention vs. control at 120 min (34.5 ± 1.1 °C vs. 35.3 ± 1.0 °C, p = 0.02). |

| Wandaller et al. [54] | CA |

Intervention 1: N: 5 Intervention 2: N: 6 Control: none. Demographic data: NR. |

Intervention: post-ROSC head cooling without (1) or with neck cooling (2). Additional endovascular cooling if necessary. TT: 33 °C (esophageal). |

ED | Thermocouple thermometer, Mon-a-term, Mallinckrodt, Inc, USA. | Esophageal and jugular | None | TTy showed a drop of 3.4 °C in the first 3 h of cooling. |

T drop was 3.7 °C at the jugular site and 2.4 °C at the esophageal site. With respect to esophageal T, TTy displayed a bias of − 1.65 {−2.2; −1.1} °C (p=0.001) in Intervention 1 vs. −3.06 {-4.27; −1.85} °C in Intervention 2 (p=0.001). |

| Zeiner et al. [55] | OHCA |

N: 27 Age: 58 (52; 64) y Male: 74% |

Post-ROSC surface body cooling plus head and body cooling by pre-cooled mattress. TT: 33 ± 1 °C (pulmonary artery). |

ED/ICU | IRTT, Ototemp LighTouch, Exergen, USA; only at admission. |

Esophageal, bladder, or pulmonary artery |

None | TTy was measured only at admission and showed a value of 35.3 °C (34.9–36.0 °C). | NR |

| Ko et al. [56] | OHCA |

Intervention: N: 23 Age: 55 ± 15 y Male: 87% Control: N: 35 Age: 63 ± 18 y Male: 71% |

Intervention: post-ROSC whole body cooling by blanket and cold crystalloid intravenous infusion. TT: 33 °C (tympanic). Control: standard care. |

ED/ ICU | Non-contact thermometer, NR. | None | None | TTy detected significant differences (p = 0.004) during TTM in intervention (35.16 °C) vs. control (36.5 °C). | NR |

| Skulec et al. [57] | OHCA |

Intervention: N: 40 Age: 61 ± 18 y Male: 85% Control: N: 40 Age: 61 ± 17 y Male: 72% |

Intervention: post-ROSC, PH cooling by intravenous cold saline infusion plus in-hospital TTM. TT: <34 °C (tympanic). Control: standard care (in-hospital TTM). |

PH/ ED | NR | None | None | In intervention, TTy dropped by 1.4 ± 0.8 °C (from 36.2 ± 1.5 to 34.7 ± 1.4 °C; p<0.001) in 42.8 ± 19.6 min. The tympanic TT was reached in 17.5% of patients. | NR |

| Storm et al. [58] | OHCA |

Intervention: N: 20 Age: 62 (52; 71) y Male: 65% Control: N: 25 Age: 58 (44; 66) y Male: 84% |

Intervention: post-ROSC head cooling by hypothermia cap. TT: NR. Control: standard care. |

PH | NR | None | None |

In intervention: TTy dropped from 35.5 °C (34.8; 36.3) to 34.4 °C (33.6; 35.4) after head cooling (p<0.001). In two patients, TTy was not affected by cooling. |

NR |

| Erlinge et al. [59] | STEMI |

Intervention: N: 61 Age: 57 (37; 79) y Male: 79% Control: N: 59 Age: 59 (30; 75) y Male: 86% |

Intervention: pre-reperfusion cooling by cold saline infusion. TT: ≤35 °C (cooling catheter) before reperfusion. Control: standard care. |

CL | NR | None | Cooling catheter sensor, during endovascular cooling | In the intervention group, TTy was measured only at baseline and was 36.0 ± 0.7 °C. | The cooling catheter T at reperfusion was 34.7 ± 0.6 °C (p=NR). |

| Testori et al. [60] | STEMI |

Intervention: N: 47 Age: 58 ± 10 y Male: 79% Control: N: 54 Age: 55 ± 12 y Male: 81% |

Intervention: PH cooling by cold saline and surface pads, followed by CL endovascular cooling. TT: 34 °C (cooling catheter). Control: standard care. |

PH / CL | IRTT, Ototemp Ligh-Touch, Exergen, USA | None | Cooling catheter sensor, during endovascular cooling | In the intervention group, TTy displayed a significant decrease from a baseline of 36.1 ± 0.5 °C to 35.5 ± 0.6 °C after PH cooling (p < 0.01). | The cooling catheter T at reperfusion was 34.4 °C ± 0.6 °C. |

Data are numbers (N), percentages (%), mean, mean ± standard deviation or limits of agreements*, mean {95% confidence interval}, median§, median (interquartile range), median [range], as available. $, bias definition reversed with respect to the original publication. CA, cardiac arrest; CL, catheter lab; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; IRTT, infrared tympanic thermometer; NR, not reported; NS, not significant; OHCA, out of hospital cardiac arrest; MI, myocardial infarction; PH, pre-hospital; r, correlation coefficient; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; T, temperature; TM, temperature measurement; TT, target temperature; TTy, tympanic temperature; y, years; vs., versus

Table 4.

Studies performing target temperature management in acute neurologic diseases

| Study | Disease | Population | Cooling approach | Setting | Tympanic TM device | Core TM site | Other TM sites | Main results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Protocol | Feasibility | Comparability | |||||||

| Abou-Chebl et al. [61] | TBI, IS, ICH |

N: 15* Age: 50 ± 17 y Male: 40% NIHSS: 26.7 ± 6.7 |

Naso-pharingeal cooling | Administration rate of 80 L/min for 1 h. | NICU | NR |

Bladder, or rectal, or esophageal, or pulmonary artery. Brain |

None | TTy decreased by 2.2 ± 2 °C during induction, with a drop of 0.65 ± 0.39 °C within 15 min (two outliers excluded). | During induction, T decreased by 1.4 ± 0.4 °C (by 0.53 ± 0.24 °C at 15 min) at the brain and by 1.1 ± 0.6 °C (by 0.43 ± 0.35 °C at 15 min) at core sites (bladder, rectal esophageal, or pulmonary artery). |

| Poli et al. [62] | IS, ICH, SAH |

Intervention 1: N: 10 Age: 65 ± 7 y Male: 60% Intervention 2: N: 10 Age: 56 ± 12 y Male: 50% Overall NIHSS: 14.5 (6.75-24.75) |

Intervention 1: Whole body cooling by cold saline infusion (4 °C). Intervention 2: Naso-pharingeal cooling |

Intervention 1: Infusion flow rate of 4 L/h for 33 ± 4 min. Intervention 2: rate of 60 L/min for 1 h. |

NICU | NR |

Bladder, rectal, and esophageal. ICP/T brain probe (>3 cm below the cortical surface) |

None | TTy reacted similarly to relative changes of brain T during cold infusion, albeit with slightly different absolute values. | TTy correlated well with brain T changes induced by cold infusion, but overestimated brain cooling by naso-pharyngeal cooling (p = 0.005). TTy was slightly lower than brain T even at baseline (37.1 ± 0.7 °C vs 37.5 ± 0.7 °C, p < 0.001). |

| Poli et al. [63] | IS, ICH, SAH |

N: 11 Age: 58 ± 15 y Male: 73% NIHSS: 22.9 ± 13.2 |

Head and neck cooling (4 °C); subsequent whole-body surface cooling if requested. |

Device applied if body core T > 37.1 °C. Drugs: If body core T > 37.1 °C after 1 h of cooling or initial body core T > 38.0 °C, administration of acetaminophen or metamizole and whole-body surface cooling. |

NICU | Thermistor thermometer, TTS 400, Smiths Medical, USA |

Bladder. ICP/T brain probe, (>3 cm below the cortical surface) |

None | After 1 h of cooling, TTy was reduced by −1.69 ± 1.19 °C (p < 0.001), with a maximum decrease of −1.79 ± 1.19 °C after 37 ± 16 min. | TTy at baseline and during cooling was significantly lower (p <0.001) than brain T. After 1 h of cooling, brain T was reduced by −0.32 ± 0.2 °C (p <0.001), and bladder T by −0.18 ± 0.15 °C (p = 0.003). The maximal decrease of brain T was −0.36 ± 0.22 °C after 49 ± 17 min, and of bladder T −0.25 ± 0.15 °C after 48 ± 19 min. |

| Kammersgaard et al. [64] | IS, ICH |

Intervention: N: 17 Age: 69 ± 16 y Male: 71% SSS: 25.8 (11.5) Control: N: 56 Age: 70 ± 10 y Male: 77% SSS: 28 (11.5). |

Intervention: whole-body cooling by “forced air” method. Control: standard care. |

Intervention: device applied for 6 h. | SU | IRTT, Diatek Model 9000, Diatek Inc, USA | Rectal | None | The mean TTy decreased significantly after 1 h of cooling (from 36.8 °C at baseline to 36.4 °C, p = 0.002). The lowest TTy was achieved after 6 h (35.5 °C, p = 0.001 vs baseline). | A strong correlation was observed between rectal T and TTy. |

| Kollmar et al. [65] | IS |

N: 10 (9 receiving rtPA) Age: 67 ± 13 y Male: NR NIHSS: 5.5 [4-12]. |

Whole body cooling by cold saline infusion (4 °C, 25 mL/kg body weight) |

Administration for 123 ± 20 min after symptom onset and 17 ± 11 min after rt-PA treatment start. Drugs: pethidine/ buspirone for preventing shivering. |

NR | NR | None | None | TTy decreased from a baseline of 37.1 ± 0.7 °C by a maximum of 1.6 ± 0.3 °C (p < 0.005). The lowest measured TTy (35.4 ± 0.7 °C) was reached 52 ± 16 min after cold infusion start. | NR |

| Sund-Levander and Wahren 2000 [66] | SAH, CH, TBI |

N: 7 Age: 57 ± 11 y Male: 29% |

Whole body cooling, or wrists, ankles, or groin cooling. | Body surface sponged with cool water or alcohol; or alcohol-saturated wraps on wrists, ankles, or groin. Additional cooling with a fan. | NICU | IRTT, Genius 3000 A, Sherwood Medical, UK | None | Skin surface at the toe tip | An increased TTy - toe T gradient was significantly associated with the occurrence of shivering (p < 0.01). | The TTy - toe T gradient decreased more during the intervention when the arms and legs were covered (9.1 ± 5.7 °C) than uncovered (11.7 ± 4.2 °C, p < 0.001). |

Data are numbers (N), percentages (%), mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or [range], as available. *Hypothermia was performed for neuroprotection only in 6 patients

CH, cerebral haematoma; IRTT, infrared tympanic thermometer; ICH, intracerebral haemorrage; ICP, intracranial pressure; IS, ischemic stroke; NICU, neurointensive care unit; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; NR, not reported; rtPA, recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; SSS, Scandinavian Stroke Scale (SSS) score; SU, stroke unit; T, temperature; TH, therapeutic hypothermia; TM, temperature measurement; TTM, target temperature management; TTy, tympanic temperature; TBI, traumatic brain injury; y, years

Tympanic temperature measurement during testing of TTM approaches in healthy subjects

The literature search identified 12 studies that monitored TTy to test the effects of TTM protocols in healthy subjects. These studies are summarized in Table 2. In 10 studies [32–40, 42], TTM was achieved using surface cooling garments, such as head and neck or chest and thighs cooling devices. In the remaining two studies [41, 43], endovascular cold solutions were used. Comparative core-temperature measurements were present in eight studies [32–39], where rectal/intestinal sites were monitored. Consistently among studies, TTy showed more pronounced changes than rectal [33–35] or intestinal temperature [32]. During chest and thighs surface cooling, the difference between tympanic and rectal temperature was maximal during induction of hypothermia and decreased during its maintenance [36]. Compared to other measurement sites, during head cooling TTy temperature showed lower variations than skin temperature [35] and more reliable data than sublingual temperature measurements [42]. Overall the studies showed that TTy was useful in the validation of novel cooling strategies in healthy subjects, where TTy was able to track temperature variations induced by local head and/or neck [32–35, 42] or chest and tights cooling [36–39]. In addition, it was shown to correlate with intracerebral blood flow velocity during mild hypothermia induced by local cooling [39]. In four studies focusing on TTM shivering thresholds [37, 38, 41, 43], TTy was able to identify the shivering threshold during either local [37, 38] or endovascular cooling [41, 43].

Tympanic temperature measurement during TTM in acute cardiovascular events

Seventeen studies were identified in which TTy was measured during TTM in patients with acute cardiovascular events. The studies are summarized in Table 3. Fifteen studies [44–58] included patients with CA. TTM was started in a pre-hospital setting in four studies [45, 46, 57, 58], while it was started at the emergency department in the remaining eleven [44, 47–56]. Two studies [59, 60] included patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions and TTM was performed pre-reperfusion [59, 60]. In one study, the procedure was started in the pre-hospital setting [60]. In all the studies, target temperature was in the range of mild hypothermia (33–34 °C), whereas the TTM cooling procedures and protocols varied among the studies, including (i) local cooling procedures [44–46, 48, 49, 58], (ii) whole body cooling [47, 57, 59, 60], and (iii) a combination of the two [50–56]. Comparative core-temperature measurements, including esophageal, rectal, bladder, iliac, or pulmonary artery sites, were mostly available for the studies performed in hospital settings [44, 45, 47–51, 53–55], and provided indications of TTy accuracy in relation to the TTM phases [50, 51]. During local cooling procedures, such as trans-nasal cooling, the tympanic site generally displayed a faster response than the rectal and bladder ones [44, 46]. The tympanic site showed comparable cooling times with respect to the esophageal site [49], although it showed larger temperature variations in response to the cooling maneuvers [44, 49]. TTy showed larger bias compared to esophageal temperature during head and especially head-neck cooling, where it underestimated esophageal T with an average bias of −1.65 °C and −3.06 °C (p=0.001), respectively [54]. During whole body cooling, the tympanic site showed a low average bias (0.021 °C) and high correlation (r = 0.95, p < 0.0001) compared to the esophageal site [47]. Conversely, TTy showed the highest bias in comparison with pulmonary-artery measurements [50, 51], resulting in the underestimation of core temperature through the different TTM phases (overall bias of − 0.6 °C [50] and − 1.03 °C [51]) and in a shorter cooling-time duration [51]. In pre-hospital settings, TTy was capable of tracking the effects of prompt post-ROSC application of TTM by cold saline infusion [57] or by a hypothermia cap [58] in CA patients, as well as the effects of cold saline and surface pads in patients with acute myocardial infarction [60]. However, tympanic measurements showed to be biased by external factors, such as variations in the environmental temperature [52] or the presence of snow/ice in the ear canal [45]. In the in-hospital setting, tympanic measurements were able to track temperature changes associated with nasal/pharyngeal or head/neck cooling [44, 48, 49, 53], cold saline infusion [47, 57], or a combination of local and whole body cooling [50, 51, 53–56]. In patients with acute myocardial infarction [59, 60], the tympanic site was used to complement catheter tip measurements, when the latter were not available.

Tympanic temperature measurement during TTM in acute neurological disorders

Six studies tracked TTy during TTM in patients with acute neurological disorders, which included ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and cerebral hematoma after traumatic brain injury. The studies are summarized in Table 4. TTM protocols were applied in-hospital in all the retrieved studies. In three studies [61–63], patients were intubated and deeply sedated. TTM protocols differed among the studies in terms of cooling devices, target temperature measurement sites, starting temperature, and target temperature (mostly mild hypothermia). The applied cooling techniques included (i) whole body cooling by intravenous injection of cold saline solutions [62, 65] and (ii) local body cooling by nasopharyngeal [61, 62] or head/neck cooling devices [63], body surface wraps/sponges [66], and/or the “forced air” method [64]. In most of the studies, comparative core measurements were available for the bladder, rectal, and esophageal sites [61–63, 67], and in one study also for the pulmonary artery [61]. TTy showed a larger drop compared to other core-temperature measurement sites during pharyngeal cooling [61], while it showed strong correlation with rectal temperature during surface cooling by “forced air” method [64]. In three studies [61–63], brain temperature measurements from a probe inserted below the cortical surface were available. TTy correlated well with brain temperature during whole body cooling induced by intravenous cold saline solution in stroke patients, although it displayed lower values already at baseline with a bias of − 0.4 °C [62]. During nasopharyngeal cooling [61, 62] or head and neck cooling [63], TTy overestimated brain cooling, showing a more marked decrease (drop in the first hour of cooling ranging from −1.69 to −2.2 °C at the tympanum vs. −0.32 to −1.4 °C at the brain), while other core-temperature measurement sites underestimated brain cooling, displaying a lower decrease (temperature drop ranging from − 0.18 °C to − 1.1 °C) [61, 63].

TTy displayed capability to track temperature changes induced by either local or whole cooling. In addition, when used in combination with skin temperature, it depicted the risk of shivering during surface cooling [66].

Discussion

The main findings of the present scoping review, aimed at assessing the diffusion, feasibility, and accuracy of TTy monitoring during TTM, are: (i) TTy was capable to track temperature changes induced by a variety of TTM approaches, including local or whole body cooling, in both pre-hospital and in-hospital settings and under different clinical conditions; (ii) TTy may have selective advantages for TTM in pre-hospital settings, where it is often the sole temperature measurement available; and (iii) limited evidence is available about TTy accuracy in relation to reliable core body and brain sites.

Feasibility and performance of TTy monitoring in emergency and critical care

The evidence provided by the 35 identified studies generally supported the capability of TTy to follow temperature changes induced by either local or whole-body cooling strategies. The most common application fields for TTy were the testing of novel cooling strategies in healthy subjects and the monitoring of TTM in patients with acute cardiovascular events, while applications in patients with acute neurological disorders were sparser. In patients with acute cardiac disease, TTy monitoring was applied in both pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency settings. In the former setting, tympanic monitoring was mostly used as the sole temperature measurement, which may indicate a selective advantage of TTy in this condition. Thanks to its reduced invasiveness and easy application, ear probe measurements may allow prompt TTM initiation [68]. In comparison, esophageal temperature probes usually require an intubated patient and rectal temperature measurements may be not easily accessible [68]. However, factors limiting TTy reliability should be properly considered for an appropriate use of the technique. TTy measurements may be influenced by alterations in the blood flow to the brain, as demonstrated for instance by tilting maneuvers [23]. Therefore, TTy measurements in CA patients should be considered reliable only after the patient has regained a stable spontaneous circulation. Moreover, pre-hospital studies showed TTy measurements to be affected by external factors, such as variations in the environmental temperature or the presence of snow/ice in the ear canal [45]. Consistently, previous studies pointed out the necessity of performing TTy measurements in a clean and dry ear canal and the importance of properly insulating the tympanic probe, especially when operating in settings exposed to environmental factors (e.g., cold, wind) [25, 69].

Comparison of the tympanic site versus other core-temperature measurement sites

In emergency and critical care settings, alternative core-temperature measurement sites are available to track temperature; thus, the performance and eventual advantages of TTy in comparison to other measures need to be evaluated. Tympanic measurements were combined with other measurements in 30 studies [32–39, 41–55, 59–64, 66], of which 22 studies [32–39, 44, 46–54, 61–64] provided a direct comparison with temperatures measured at different core or brain sites. These studies presented heterogeneity in terms of studied population, cooling protocols and devices, tympanic thermometer type (IRTTs or thermistor/thermocouple thermometers), and comparative/reference sites. All these variability factors hindered the calculation of an overall figure of merit for tympanic measurement site. As an additional limitation, rectal temperature was mostly used as comparator among studies. The rectal site has known limitations and a slow response in dynamic conditions [20, 70–72], which is mainly attributed to the buffering influence and heat-sink effect of rectal tissue and stool in the rectum [73, 74].

The comparison of Tty with the most reliable core sites (i.e., esophageal, jugular, and pulmonary artery sites), available from studies in emergency and critical care settings, showed that TTy performance depended on the cooling protocols and reference site considered. Compared to esophageal temperature, TTy showed comparable cooling times during intranasal cooling [49], and low bias and high correlation during cold saline infusion [47]. A larger bias with esophageal temperature was observed during head and neck cooling [54]. Compared to the pulmonary artery, the tympanic site showed the highest bias during cold saline infusion [50, 51]. Although the pulmonary artery temperature is usually considered as the gold standard core-temperature to guide clinical mild hypothermia [75, 76], previous studies have shown that the temperature of the pulmonary artery blood may reflect less well brain temperature when hypothermia is induced or reversed, during either selective head cooling or rapid intravascular cooling [77, 78]. Instead, esophageal temperature responds rapidly to changes in the temperature of the blood perfusing the heart and great vessels [77, 79] and it showed a better relationship with brain temperature when inducing hypothermia and at early TTM, in either selective head or whole-body cooling [77]. The better agreement of TTy with the esophageal than with the pulmonary artery temperature may thus suggest the reliability of TTy to track brain temperature. The capability of TTy to reflect brain temperature is supported by the assumption that the tympanic membrane is supplied by vasculature from the same sources that supply the brain (i.e., branches of the basilar and internal carotid arteries, which join anastomoses with branches of the external carotid artery in the region around and within the tympanic membrane [21, 22, 80]), which guarantees thermal equilibrium between the two sites [23]. However, although TTy is currently the most commonly used non-invasive method for brain temperature estimation [81], being the sole anatomical structure close to the brain that is accessible without surgery [82, 83], concerns remain on its accuracy, mainly due to measurement errors, measuring devices, and/or real temperature differences between the ears [80]. In the specific setting of TTM, the present review revealed a gap of evidence in the literature about the capability of TTy to reflect brain temperature. We identified only three studies in acute neurological patients [61–63], which provided comparative direct brain temperature measurements at a single subcortex site. The studies displayed heterogeneity in terms of patient characteristics and underlying disorders, cooling procedures, and target temperature. The results showed a high correlation between TTy and brain temperature during whole body cooling. Nonetheless, TTy generally overestimated brain cooling in either whole body [61, 62] or local body cooling [62], with more severe overestimation during head and neck cooling [63]. Of note, other sites for core-temperature measurements generally underestimated cooling effects [61]. Although these results may suggest the potential of TTy to track brain temperature with similar performance to other more invasive distal measurement sites, the larger response of TTy may result in an overestimation of cooling effects through different TTM phases and thus in a shorter cooling-time duration [51], with the risk for patients to stay outside the ideal temperature range during TTM induction and steady state.

Future perspectives

Simultaneous measurements at different brain and core temperature sites according to well-defined protocols should be performed during both local and whole-body cooling procedures. The characterization of the spatiotemporal temperature patterns under various TTM approaches by a continuous temperature acquisition through the different TTM phases is desirable. In experimental studies, brain temperature should be monitored at multiple sites, since a single site may not reflect temperature across the brain, especially in the presence of head cooling and marked temperature gradients [84–86]. The systematic assessment of bias and correlation between TTy and brain or other core-temperature measurement sites and the comparison with therapeutic outcome may allow to define sharp recommendation and safe target ranges for TTy under different TTM applications. TTy performance may be improved with proper recalibration of target temperature values, as TTy often led to an underestimation of core temperature even at baseline but showed a moderate to high correlation with esophageal temperature. Finally, clinical, experimental, and industrial research should synergistically concur to develop wearable temperature trackers [80], able to overcome the limitations of current tympanic thermometers [25, 66, 69, 80, 87] and to grant fix probe positioning and protection from external environmental conditions [80]. These developments may improve temperature monitoring and allow early TTM extension under logistically challenging critical conditions.

Conclusions

The results of the present scoping review provided evidence about the capability of TTy to track temperature changes induced by either local or whole-body cooling in both pre-hospital and in-hospital TTM applications. However, there is a paucity of studies performing a systematic comparison of TTy performance with reliable core and brain temperature measurement sites, which hinders a thorough evaluation of TTy advantages in emergency settings and of the capability of TTy to track brain temperature. Future experimental and clinical studies should bridge this gap of evidence by providing reliable devices and dedicated temperature ranges for safe application of TTy in TTM and by clarifying the relationship between TTy and brain temperature. Thanks to its easy use and reduced invasiveness, TTy may have selective advantage in pre-hospital settings, when practical limitations may hinder temperature acquisition from more invasive sites.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Innovation, Research, University and Museums of the Autonomous Province of Bozen/Bolzano for covering the Open Access publication costs.

Abbreviations

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- CA

Cardiac arrest

- IRTT

Infrared tympanic thermometer

- PCC

Population-Concept-Context

- ROSC

Return of spontaneous circulation

- TTM

Target temperature management

- TTy

Tympanic temperature

Authors’ contributions

MM and MA conceived the study, performed the systematic search, extracted and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript. MF, IBR, and GS concurred to data interpretation and substantively revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the FESR Program 2014–2020 of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano – Alto Adige, under Grant Agreement [513/2019]/Project number [FESR 1114] [Development of innovative sensors for monitoring vital parameters in emergency medicine, MedSENS].

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Michela Masé and Alessandro Micarelli contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Taccone FS, Picetti E, Vincent J-L. High quality targeted temperature management (TTM) after cardiac arrest. Critical Care. 2020;24(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2721-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Gasche Y, Hassager C, Horn J, Hovdenes J, Kjaergaard J, Kuiper M, Pellis T, Stammet P, Wanscher M, Wise MP, Åneman A, al-Subaie N, Boesgaard S, Bro-Jeppesen J, Brunetti I, Bugge JF, Hingston CD, Juffermans NP, Koopmans M, Køber L, Langørgen J, Lilja G, Møller JE, Rundgren M, Rylander C, Smid O, Werer C, Winkel P, Friberg H. Targeted temperature management at 33°C versus 36°C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2197–2206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polderman KH, Herold I. Therapeutic hypothermia and controlled normothermia in the intensive care unit: practical considerations, side effects, and cooling methods. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):1101–1120. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181962ad5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polderman KH. Induced hypothermia and fever control for prevention and treatment of neurological injuries. Lancet. 2008;371(9628):1955–1969. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60837-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karnatovskaia LV, Wartenberg KE, Freeman WD. Therapeutic hypothermia for neuroprotection: history, mechanisms, risks, and clinical applications. Neurohospitalist. 2014;4(3):153–163. doi: 10.1177/1941874413519802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evald L, Brønnick K, Duez CHV, Grejs AM, Jeppesen AN, Søreide E, Kirkegaard H, Nielsen JF. Prolonged targeted temperature management reduces memory retrieval deficits six months post-cardiac arrest: a randomised controlled trial. Resuscitation. 2019;134:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lascarrou J-B, Merdji H, Le Gouge A, Colin G, Grillet G, Girardie P, et al. Targeted temperature management for cardiac arrest with nonshockable rhythm. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(24):2327–2337. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1906661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkegaard H, Søreide E, de Haas I, Pettilä V, Taccone FS, Arus U, Storm C, Hassager C, Nielsen JF, Sørensen CA, Ilkjær S, Jeppesen AN, Grejs AM, Duez CHV, Hjort J, Larsen AI, Toome V, Tiainen M, Hästbacka J, Laitio T, Skrifvars MB. Targeted temperature management for 48 vs 24 hours and neurologic outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(4):341–350. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Fazio C, Skrifvars MB, Søreide E, Creteur J, Grejs AM, Kjærgaard J, et al. Intravascular versus surface cooling for targeted temperature management after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: an analysis of the TTH48 trial. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2335-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Böttiger BW, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Genbrugge C, Haywood K, Lilja G, Moulaert VRM, Nikolaou N, Olasveengen TM, Skrifvars MB, Taccone F, Soar J. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(4):369–421. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06368-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuczynski AM, Marzoughi S, Al Sultan AS, Colbourne F, Menon BK, van Es ACGM, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia in acute ischemic stroke-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(5):13. doi: 10.1007/s11910-020-01029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Worp HB, Macleod MR, Bath PM, Bathula R, Christensen H, Colam B, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia for acute ischaemic stroke. Results of a European multicentre, randomised, phase III clinical trial. Eur Stroke J. 2019;4(3):254–262. doi: 10.1177/2396987319844690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soar J, Callaway CW, Aibiki M, Böttiger BW, Brooks SC, Deakin CD, Donnino MW, Drajer S, Kloeck W, Morley PT, Morrison LJ, Neumar RW, Nicholson TC, Nolan JP, Okada K, O’Neil BJ, Paiva EF, Parr MJ, Wang TL, Witt J, Andersen LW, Berg KM, Sandroni C, Lin S, Lavonas EJ, Golan E, Alhelail MA, Chopra A, Cocchi MN, Cronberg T, Dainty KN, Drennan IR, Fries M, Geocadin RG, Gräsner JT, Granfeldt A, Heikal S, Kudenchuk PJ, Lagina AT, III, Løfgren B, Mhyre J, Monsieurs KG, Mottram AR, Pellis T, Reynolds JC, Ristagno G, Severyn FA, Skrifvars M, Stacey WC, Sullivan J, Todhunter SL, Vissers G, West S, Wetsch WA, Wong N, Xanthos T, Zelop CM, Zimmerman J. Part 4: Advanced life support: 2015 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation. 2015;95:e71–120. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peberdy MA, Callaway CW, Neumar RW, Geocadin RG, Zimmerman JL, Donnino M, Gabrielli A, Silvers SM, Zaritsky AL, Merchant R, vanden Hoek T, Kronick SL, American Heart Association Part 9: post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(18_suppl_3):S768–S786. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard SA, Smith K, Cameron P, Masci K, Taylor DM, Cooper DJ, Kelly AM, Silvester W, Rapid Infusion of Cold Hartmanns Investigators Induction of prehospital therapeutic hypothermia after resuscitation from nonventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):747–753. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182377038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nie C, Dong J, Zhang P, Liu X, Han F. Prehospital therapeutic hypothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(11):2209–2216. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kämäräinen A, Virkkunen I, Tenhunen J, Yli-Hankala A, Silfvast T. Prehospital therapeutic hypothermia for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53(7):900–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safar P, Xiao F, Radovsky A, Tanigawa K, Ebmeyer U, Bircher N, Alexander H, Stezoski SW. Improved cerebral resuscitation from cardiac arrest in dogs with mild hypothermia plus blood flow promotion. Stroke. 1996;27(1):105–113. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.27.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strapazzon G, Procter E, Paal P, Brugger H. Pre-hospital core temperature measurement in accidental and therapeutic hypothermia. High Alt Med Biol. 2014;15(2):104–111. doi: 10.1089/ham.2014.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy PW, Heusch AI. The vagaries of ear temperature assessment. J Med Eng Technol. 2006;30(4):242–251. doi: 10.1080/03091900600711415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benzinger TH, Taylor GW. Cranial measurements of internal temperature in man. Temperature - Its Measurement and Control in Science and Industry. New York: Reinhold; 1963. pp. 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorr D, Lund A, Fredrikson M, Secher NH. Tympanic membrane temperature decreases during head up tilt: relation to frontal lobe oxygenation and middle cerebral artery mean blood flow velocity. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2017;77(8):587–591. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2017.1371323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paal P, Brugger H, Strapazzon G. Accidental hypothermia. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;157:547–563. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-64074-1.00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strapazzon G, Procter E, Putzer G, Avancini G, Dal Cappello T, Überbacher N, Hofer G, Rainer B, Rammlmair G, Brugger H. Influence of low ambient temperature on epitympanic temperature measurement: a prospective randomized clinical study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Budidha K, Kyriacou PA. In vivo investigation of ear canal pulse oximetry during hypothermia. J Clin Monit Comput. 2018;32(1):97–107. doi: 10.1007/s10877-017-9975-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmäl F, Loh-van den Brink M, Stoll W. Effect of the status after ear surgery and ear pathology on the results of infrared tympanic thermometry. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(2):105–110. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-0966-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters MDJ. In no uncertain terms: the importance of a defined objective in scoping reviews. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(2):1–4. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2016-2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagić A, Theodore WH, Boudreau EA, Bonwetsch R, Greenfield J, Elkins W, Sato S. Towards a non-invasive interictal application of hypothermia for treating seizures: a feasibility and pilot study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118(4):240–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kallmünzer B, Beck A, Schwab S, Kollmar R. Local head and neck cooling leads to hypothermia in healthy volunteers. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(3):207–210. doi: 10.1159/000329376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koehn J, Wang R, de Rojas LC, Kallmünzer B, Winder K, Köhrmann M, et al. Neck cooling induces blood pressure increase and peripheral vasoconstriction in healthy persons. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(9):2521–2529. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04349-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koehn J, Kollmar R, Cimpianu C-L, Kallmünzer B, Moeller S, Schwab S, Hilz MJ. Head and neck cooling decreases tympanic and skin temperature, but significantly increases blood pressure. Stroke. 2012;43(8):2142–2148. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.652248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zweifler RM, Voorhees ME, Mahmood MA, Parnell M. Rectal temperature reflects tympanic temperature during mild induced hypothermia in nonintubated subjects. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2004;16(3):232–235. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zweifler RM, Voorhees ME, Mahmood MA, Parnell M. Magnesium sulfate increases the rate of hypothermia via surface cooling and improves comfort. Stroke. 2004;35(10):2331–2334. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141161.63181.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zweifler RM, Voorhees ME, Mahmood MA, Alday DD. Induction and maintenance of mild hypothermia by surface cooling in non-intubated subjects. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;12(5):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahmood MA, Voorhees ME, Parnell M, Zweifler RM. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonographic evaluation of middle cerebral artery hemodynamics during mild hypothermia. J Neuroimaging. 2005;15(4):336–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2005.tb00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams R, Koster RW. Burning issues: early cooling of the brain after resuscitation using burn dressings. A proof of concept observation. Resuscitation. 2008;78(2):146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doufas AG, Lin C-M, Suleman M-I, Liem EB, Lenhardt R, Morioka N, Akça O, Shah YM, Bjorksten AR, Sessler DI. Dexmedetomidine and meperidine additively reduce the shivering threshold in humans. Stroke. 2003;34(5):1218–1223. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000068787.76670.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson K, Rubin R, Van Hoeck N, Hauert T, Lana V, Wang H, et al. The effect of selective head-neck cooling on physiological and cognitive functions in healthy volunteers. Transl Neurosci. 2015;6(1):131–138. doi: 10.1515/tnsci-2015-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wadhwa A, Sengupta P, Durrani J, Akça O, Lenhardt R, Sessler DI, Doufas AG. Magnesium sulphate only slightly reduces the shivering threshold in humans. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(6):756–762. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busch H-J, Eichwede F, Födisch M, Taccone FS, Wöbker G, Schwab T, Hopf HB, Tonner P, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Martens P, Fritz H, Bode C, Vincent JL, Inderbitzen B, Barbut D, Sterz F, Janata A. Safety and feasibility of nasopharyngeal evaporative cooling in the emergency department setting in survivors of cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2010;81(8):943–949. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Callaway CW, Tadler SC, Katz LM, Lipinski CL, Brader E. Feasibility of external cranial cooling during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2002;52(2):159–165. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9572(01)00462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castrén M, Nordberg P, Svensson L, Taccone F, Vincent J-L, Desruelles D, et al. Intra-arrest transnasal evaporative cooling: a randomized, prehospital, multicenter study (PRINCE: Pre-ROSC IntraNasal Cooling Effectiveness) Circulation. 2010;122(7):729–736. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.931691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hasper D, Nee J, Schefold JC, Krueger A, Storm C. Tympanic temperature during therapeutic hypothermia. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(6):483–485. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.090464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hachimi-Idrissi S, Corne L, Ebinger G, Michotte Y, Huyghens L, Hachimi-Idrissi S, et al. Mild hypothermia induced by a helmet device: a clinical feasibility study. RESUSCITATION. 2001;51(3):275–281. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9572(01)00412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Islam S, Hampton-Till J, Watson N, Mannakkara NN, Hamarneh A, Webber T, Magee N, Abbey L, Jagathesan R, Kabir A, Sayer J, Robinson N, Aggarwal R, Clesham G, Kelly P, Gamma R, Tang K, Davies JR, Keeble TR. Early targeted brain COOLing in the cardiac CATHeterisation laboratory following cardiac arrest (COOLCATH) Resuscitation. 2015;97:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.09.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krizanac D, Stratil P, Hoerburger D, Testori C, Wallmueller C, Schober A, Haugk M, Haller M, Behringer W, Herkner H, Sterz F, Holzer M. Femoro-iliacal artery versus pulmonary artery core temperature measurement during therapeutic hypothermia: an observational study. Resuscitation. 2013;84(6):805–809. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shin J, Kim J, Song K, Kwak Y. Core temperature measurement in therapeutic hypothermia according to different phases: comparison of bladder, rectal, and tympanic versus pulmonary artery methods. Resuscitation. 2013;84(6):810–817. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stratil P, Wallmueller C, Schober A, Stoeckl M, Hoerburger D, Weiser C, Testori C, Krizanac D, Spiel A, Uray T, Sterz F, Haugk M. Seasonal variability and influence of outdoor temperature on body temperature of cardiac arrest victims. Resuscitation. 2013;84(5):630–634. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takeda Y, Kawashima T, Kiyota K, Oda S, Morimoto N, Kobata H, Isobe H, Honda M, Fujimi S, Onda J, I S, Sakamoto T, Ishikawa M, Nakano H, Sadamitsu D, Kishikawa M, Kinoshita K, Yokoyama T, Harada M, Kitaura M, Ichihara K, Hashimoto H, Tsuji H, Yorifuji T, Nagano O, Katayama H, Ujike Y, Morita K. Feasibility study of immediate pharyngeal cooling initiation in cardiac arrest patients after arrival at the emergency room. Resuscitation. 2014;85(12):1647–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wandaller C, Holzer M, Sterz F, Wandaller A, Arrich J, Uray T, Laggner AN, Herkner H. Head and neck cooling after cardiac arrest results in lower jugular bulb than esophageal temperature. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(4):460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeiner A, Holzer M, Sterz F, Behringer W, Schörkhuber W, Müllner M, et al. Mild resuscitative hypothermia to improve neurological outcome after cardiac arrest: a clinical feasibility trial. Stroke. 2000;31(1):86–94. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ko Y, Jung JY, Kim H-T, Lee J-Y. Auditory canal temperature measurement using a wearable device during sleep: comparisons with rectal temperatures at 6, 10, and 14 cm depths. J Therm Biol. 2019;85:102410. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2019.102410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skulec R, Truhlár A, Seblová J, Dostál P, Cerný V. Pre-hospital cooling of patients following cardiac arrest is effective using even low volumes of cold saline. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):R231. doi: 10.1186/cc9386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Storm C, Schefold JC, Kerner T, Schmidbauer W, Gloza J, Krueger A, Jörres A, Hasper D. Prehospital cooling with hypothermia caps (PreCoCa): a feasibility study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97(10):768–772. doi: 10.1007/s00392-008-0678-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erlinge D, Götberg M, Lang I, Holzer M, Noc M, Clemmensen P, et al. Rapid endovascular catheter core cooling combined with cold saline as an adjunct to percutaneous coronary intervention for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction: The CHILL-MI trial: a randomized controlled study of the use of central venous catheter core cooling combined with cold saline as an adjunct to percutaneous coronary intervention for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1857–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Testori C, Beitzke D, Mangold A, Sterz F, Loewe C, Weiser C, Scherz T, Herkner H, Lang I. Out-of-hospital initiation of hypothermia in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a randomised trial. Heart. 2019;105(7):531–537. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abou-Chebl A, Sung G, Barbut D, Torbey M. Local brain temperature reduction through intranasal cooling with the RhinoChill device: preliminary safety data in brain-injured patients. Stroke. 2011;42(8):2164–2169. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.613000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poli S, Purrucker J, Priglinger M, Ebner M, Sykora M, Diedler J, Bulut C, Popp E, Rupp A, Hametner C. Rapid Induction of COOLing in Stroke Patients (iCOOL1): a randomised pilot study comparing cold infusions with nasopharyngeal cooling. Crit Care. 2014;18(5):582. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0582-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poli S, Purrucker J, Priglinger M, Diedler J, Sykora M, Popp E, Steiner T, Veltkamp R, Bösel J, Rupp A, Hacke W, Hametner C. Induction of cooling with a passive head and neck cooling device: effects on brain temperature after stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(3):708–713. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.672923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kammersgaard LP, Rasmussen BH, Jørgensen HS, Reith J, Weber U, Olsen TS. Feasibility and safety of inducing modest hypothermia in awake patients with acute stroke through surface cooling: a case-control study: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke. 2000;31(9):2251–2256. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.9.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kollmar R, Schellinger PD, Steigleder T, Köhrmann M, Schwab S. Ice-cold saline for the induction of mild hypothermia in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a pilot study. Stroke. 2009;40(5):1907–1909. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.530410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sund-Levander M, Grodzinsky E. Assessment of body temperature measurement options. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(942):944–950. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.16.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kammersgaard LP, Jørgensen HS, Rungby JA, Reith J, Nakayama H, Weber UJ, Houth J, Olsen TS. Admission body temperature predicts long-term mortality after acute stroke: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke. 2002;33(7):1759–1762. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000019910.90280.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uleberg O, Eidstuen S, Vangberg G, Skogvoll E. Temperature measurements in trauma patients: is the ear the key to the core? Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skaiaa SC, Brattebø G, Aßmus J, Thomassen Ø. The impact of environmental factors in pre-hospital thermistor-based tympanic temperature measurement: a pilot field study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0148-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee SM, Williams WJ, Fortney Schneider SM. Core temperature measurement during supine exercise: esophageal, rectal, and intestinal temperatures. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2000;71:939–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lim CL, Byrne C, Lee JK. Human thermoregulation and measurement of body temperature in exercise and clinical settings. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2008;37:347–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilkinson DM, Carter JM, Richmond VL, Blacker SD, Rayson MP. The effect of cool water ingestion on gastrointestinal pill temperature. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(3):523–528. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815cc43e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gagnon D, Lemire BB, Jay O, Kenny GP. Aural canal, esophageal, and rectal temperatures during exertional heat stress and the subsequent recovery period. J Athl Train. 2010;45(2):157–163. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ng D. Infrared ear thermometers versus rectal thermometers. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1881. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11739-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Robinson J, Charlton J, Seal R, Spady D, Joffres MR. Oesophageal, rectal, axillary, tympanic and pulmonary artery temperatures during cardiac surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45(4):317–323. doi: 10.1007/BF03012021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akata T, Setoguchi H, Shirozu K, Yoshino J. Reliability of temperatures measured at standard monitoring sites as an index of brain temperature during deep hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass conducted for thoracic aortic reconstruction. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:1559-1565.e2. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Li H, Yang Z, Liu Y, Wu Z, Pan W, Li S, Ling Q, Tang W. Is esophageal temperature better to estimate brain temperature during target temperature management in a porcine model of cardiopulmonary resuscitation? Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1279307. doi: 10.1155/2017/1279307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stone JG, Young WL, Smith CR, Solomon RA, Wald A, Ostapkovich N, et al. Do standard monitoring sites reflect true brain temperature when profound hypothermia is rapidly induced and reversed? Anesthesiology. 1995;82(2):344–351. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199502000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaukuntla H, Harrington D, Bilkoo I, Clutton-Brock T, Jones T, Bonser RS. Temperature monitoring during cardiopulmonary bypass--do we undercool or overheat the brain? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26(3):580–585. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]