Abstract

Background

Clinical trials in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) focus primarily on ambulant patients. Results cannot be extrapolated to later disease stages due to a decline in targeted muscle tissue. In non‐ambulant DMD patients, hand function is relatively preserved and crucial for daily‐life activities. We used quantitative MRI (qMRI) to establish whether the thenar muscles could be valuable to monitor treatment effects in non‐ambulant DMD patients.

Methods

Seventeen non‐ambulant DMD patients (range 10.2–24.1 years) and 13 healthy controls (range 9.5–25.4 years) underwent qMRI of the right hand at 3 T at baseline. Thenar fat fraction (FF), total volume (TV), and contractile volume (CV) were determined using 4‐point Dixon, and T2water was determined using multiecho spin‐echo. Clinical assessments at baseline (n = 17) and 12 months (n = 13) included pinch strength (kg), performance of the upper limb (PUL) 2.0, DMD upper limb patient reported outcome measure (PROM), and playing a video game for 10 min using a game controller. Group differences and correlations were assessed with non‐parametric tests.

Results

Total volume was lower in patients compared with healthy controls (6.9 cm3, 5.3–9.0 cm3 vs. 13.0 cm3, 7.6–15.8 cm3, P = 0.010). CV was also lower in patients (6.3 cm3, 4.6–8.3 cm3 vs. 11.9 cm3, 6.9–14.6 cm3, P = 0.010). FF was slightly elevated (9.7%, 7.3–11.4% vs. 7.7%, 6.6–8.4%, P = 0.043), while T2water was higher (31.5 ms, 30.0–32.6 ms vs. 28.1 ms, 27.8–29.4 ms, P < 0.001). Pinch strength and PUL decreased over 12 months (2.857 kg, 2.137–4.010 to 2.243 kg, 1.930–3.339 kg, and 29 points, 20–36 to 23 points, 17–30, both P < 0.001), while PROM did not (49 points, 36–57 to 44 points, 30–54, P = 0.041). All patients were able to play for 10 min at baseline or follow‐up, but some did not comply with the study procedures regarding this endpoint. Pinch strength correlated with TV and CV in patients (rho = 0.72 and rho = 0.68) and controls (both rho = 0.89). PUL correlated with TV, CV, and T2water (rho = 0.57, rho = 0.51, and rho = −0.59).

Conclusions

Low thenar FF, increased T2water, correlation of muscle size with strength and function, and the decrease in strength and function over 1 year indicate that the thenar muscles are a valuable and quantifiable target for therapy in later stages of DMD. Further studies are needed to relate these data to the loss of a clinically meaningful milestone.

Keywords: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, MRI, Target for muscle treatment, Thenar muscles

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is characterized by progressive replacement of muscle with fat and fibrotic tissue due to the absence of full‐length dystrophin. 1 This leads to a clinical presentation with a proximal to distal gradient of muscle weakness, in which loss of independent ambulation generally occurs years before loss of upper arm function. 2 Although the first drugs in DMD have now received regulatory approval, there is no cure yet, and ongoing clinical trials focus primarily on ambulant patients. 3 Regulators do not support extrapolation of trial results in ambulant patients to later disease stages, because progressive replacement of muscle by fat is considered irreversible and thus leads to a progressive reduction in target tissue. 4 , 5

Hand function is preserved even longer than upper arm function in DMD and is crucial for daily‐life activities. 6 , 7 Many of these activities require grasping motions for which the thenar muscles primarily generate the opposition of the thumb. 8 Because efficacy of new drugs has to be proven separately in non‐ambulant patients, preparation for clinical trials in later disease stages is essential. To facilitate the development of these trials, it is necessary to collect natural history data, develop outcome parameters, and study biomarkers that reflect a decline in upper limb function. Quantitative MRI (qMRI) fat fraction (FF) has shown potential as such a biomarker in the lower extremities, and increased FF of the vastus lateralis predicts a decline in ambulatory function. 9 , 10 , 11 Ongoing studies assess the feasibility of qMRI FF in the upper and lower arm, but studies in intrinsic hand muscles are lacking. 12 , 13 , 14 Another qMRI parameter, the T2 relaxation time of the muscle compartment (T2water), is indicative for early muscle pathology, because it increases due to inflammation, myocyte swelling, oedema, and necrosis. 15 , 16 Here, we aimed to study the thenar muscles for their value to monitor treatment effects in non‐ambulant DMD patients by obtaining natural history of hand function over 1 year and by assessing qMRI parameters compared with healthy controls (HC).

Methods

Participants

Between March 2018 and July 2019, DMD patients were recruited from the Dutch Dystrophinopathy Database 17 and via Dutch neurologists, rehabilitation specialists, and patient organizations. Inclusion criteria were male, non‐ambulant genetically confirmed DMD, aged ≥8 years. Exclusion criteria were MRI contraindications (e.g. scoliosis surgery or daytime respiratory support), inability to lie still for 45 min, exposure to an investigational drug ≤6 months prior to participation, and recent (≤6 months) upper extremity surgery or trauma. Healthy age‐matched controls were recruited using posters and advertisements in local media. The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients and legal representatives prior to inclusion. The investigation was conducted according to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The reported assessments were performed as part of a longitudinal study on outcome measures in non‐ambulant DMD patients at Leiden University Medical Center: ‘Upper extremity outcome measures in non‐ambulant DMD patients’, registered on ToetsingOnline with ABR number NL63133.058.17 (https://www.toetsingonline.nl). We report results from baseline (DMD and HC) and 12 months follow‐up (DMD only). MRI of the hand muscles was only performed at baseline, and clinical assessments were performed at every visit.

MRI acquisition

MRI scans of the right hand were acquired on a 3 T scanner (Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) with two 47 mm surface coils placed on the ventral and dorsal side of the thenar muscles. The standard position for participants was on the right side with the right shoulder in 90° flexion, the elbow in 90° flexion and the forearm in maximum pronation, which was supported by holding a handle (Supporting Information, Figure S1). If this position was uncomfortable, patients could choose from lying on the right side with the elbow halfway between pronation and supination or lying in supine position with the forearm either in maximum pronation or halfway between pronation and supination.

The protocol consisted of a 4‐point Dixon scan [25 contiguous slices of 4 mm thickness, repetition time (TR) 310 ms, first echo time (TE) 4.40 ms, echo spacing (ΔTE) 0.76 ms, flip angle 20°, field of view (FOV) 100 × 100 mm, voxel size 1 × 1 mm, reconstructed voxel size 0.89 × 0.89 mm], a multiecho spin‐echo (MSE) scan (five slices of 4 mm thickness with 8 mm slice gap, TR 300 ms, TE 8.0 ms, ΔTE 8.0 ms, FOV 100 × 100 mm, voxel size 1 × 1 mm, reconstructed voxel size 0.89 × 0.89 mm), and a B1 map (five contiguous slices of 12 mm thickness, dual‐TR gradient echo with TRs of 30 and 100 ms, TE 2.01 ms, FOV 100 × 100 mm, voxel size 1.56 × 2 mm, reconstructed voxel size 0.89 × 0.89 mm). The Dixon scans, MSE scans, and B1 maps were aligned perpendicular to the first metacarpal bone and covered the thenar muscles completely.

MRI analysis

Water and fat images were reconstructed from the Dixon data using in‐house developed software (Matlab 2016a, The Mathworks of Natick, Massachusetts, USA) assuming a six‐peak lipid spectrum. 18 B0 maps were determined from the phase data of the first and last echoes, and the Goldstein branch cut method was used for phase unwrapping. 19 Scans with major movement artefacts, water/fat swaps, insufficient signal, or other artefacts in the thenar were excluded. Regions of interest (ROIs) of the thenar muscles were drawn on all slices of the Dixon scans using online available software (http://mipav.cit.nih.gov) (Figure 1A). The thenar muscles consist of the abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, and opponens pollicis muscle. The ROIs were drawn on the border of this muscle group, except at the dorsal side because the fascia between the different intrinsic hand muscles could not be observed. This dorsal ROI boundary was defined by a straight line on the palmar side of the tendon of the flexor pollicis longus muscle and the first metacarpal bone. All ROIs of the HCs were drawn by one rater (K.J.N.) and of the DMD patients by two raters (K.J.N. and A.J.P.). Because different positioning of the first metacarpal bone could influence the position and size of a single slice, all qMRI values are reported for the whole thenar muscle and used for subsequent analyses. The total volume (TV; cm3) of all thenar ROIs combined was assessed from these raw ROIs. For FF measurements (FF; %), an erosion of two voxels was performed for every ROI to avoid contamination of ROIs with subcutaneous fat. A correction for the T1‐weighting in the water and fat images was incorporated in the FF calculation, assuming T1 values of 1420 ms (correction factor: 1.25) and 371 ms (correction factor: 1.05) for water and fat, respectively. 20 Thenar FF was then calculated as a weighted mean value by averaging all thenar voxels of all eroded ROIs from the reconstructed fat and water images as follows:

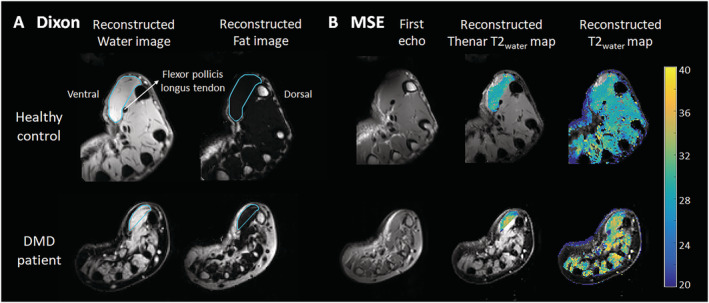

Figure 1.

Dixon and multiecho spin‐echo (MSE) MRI acquisitions and analyses.(A) Example of a Dixon reconstructed water and fat image of a healthy control (HC; 16 years old) and a Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) patient (13 years old). Regions of interest of the thenar muscles were drawn (light blue line) with the dorsal boundary defined as a line on the palmar side of the tendon of the flexor pollicis longus muscle and first metacarpal bone. (B) Example of the first echo from the MSE scan of the same HC and DMD patient and the following reconstructed images: T2water map for voxels within the thenar region of interest and T2water map of all hand muscles. MSE voxels that fitted on the physiological boundaries of the dictionary were excluded.

Contractile volume (CV) was calculated by subtracting the fat containing area from TV as follows:

The MSE scans were fitted using a dictionary‐fitting algorithm with an extended phase graph model in which the FF, T2water, and B1 were fitted, and the flip angle slice profile and through‐plane chemical shift displacement were incorporated. 21 , 22 This dictionary was created using T2water values from 10 to 60 ms, T2fat values from 120 to 200 ms, FF values from 0% to 100%, and B1 values from 50% to 140%. The T2fat was calibrated on the subcutaneous fat per slice by creating an automatic fat mask using the last echo of the MSE sequence. The fitted B1 values were visually confirmed to correspond to the B1 map by comparing values from similar locations on the same slices. Uneroded ROIs were copied from the Dixon images, manually checked and adapted in case of movement between scans, and eroded with two voxels before further analysis. Voxels that fitted on the physiological boundaries of the dictionary were excluded. If less than 100 thenar voxels remained for a particular scan, that scan was excluded. Thenar T2water was estimated over all slices as a weighted mean of all thenar voxels (Figure 1B) and of all intrinsic hand muscle voxels (supporting information).

Clinical assessments

All clinical assessments were performed after the MRI examination. Weight was measured using a patient lift with inbuilt scale (Maxi Move™, ArjoHuntleigh, Sweden). Height was calculated from the ulna length for both DMD patients and HCs using the formula proposed by Gauld et al. 23 with 18 as maximum age.

Pinch strength of the right hand was assessed with MyoPinch and grip strength with MyoGrip (Institute of Myology, Ateliers Laumonier, France). 24 Specific strength was defined as the pinch strength in kg per cm3 of CV. Performance of the upper limb (PUL) 2.0 was performed for the right arm and only in DMD patients because a maximum score was assumed in HCs. The PUL 2.0 consists of 22 items and yields a maximum total score of 42 points. 25 Items are divided over three dimensions with a maximum score of 12 for the shoulder dimension, 17 for the elbow dimension, and 13 for the distal wrist/hand dimension. The adapted DMD upper limb patient reported outcome measure (PROM) questionnaire was used to investigate patient reported upper limb function. The questionnaire contains 32 daily‐life activity items that are scored on a three‐level scale (‘cannot do’, ‘with difficulty’, and ‘easy’) with a maximum possible score of 64 points. 26 Furthermore, DMD patients were asked to play a video game (Rocket League®, Psyonix LLC, California, USA) for 10 min using a game controller (GC‐100XF Wired Gaming Controller, NACON™, Bigben group, France). In this game, patients used their right thumb to steer a vehicle on the screen. Afterwards, patients rated tiredness and difficulty on two 10‐point numeric rating scales (NRS) ranging from ‘not at all tiring/difficult’ (score 0) to ‘very tiring/difficult’ (score 10) with matching facial cartoons based on the Wong‐Baker Faces Rating Scale. 27

Statistical analysis

Interrater variability of qMRI results in DMD patients was assessed using Bland–Altman analyses to determine bias and limits of agreement. Differences in baseline characteristics, qMRI values, specific strength, and pinch strength between DMD patients and HCs were assessed with the Mann–Whitney U test. Differences in clinical assessments over 12 months were assessed using Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Bonferroni–Holm correction was used to correct for multiple comparisons of qMRI results between patients and HCs and of clinical assessments between baseline and follow‐up. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to correlate qMRI values to pinch strength and grip strength in DMD patients and HCs, and to PUL total and distal, PROM total, and NRS scores in patients. The correlation was considered very strong (0.9–1.0), strong (0.7–0.9), or moderate (0.5–0.7). 28

Data availability

Anonymized data and analysis software can be made available to qualified investigators on request.

Results

Characteristics of participants and quantitative MRI data inclusion

Twenty‐two DMD patients and 14 HCs participated. Five patients and one HC could not undergo MRI. Characteristics of the remaining 17 patients and 13 HCs are presented in Table 1. Because of the unforeseen restrictions during the COVID‐19 pandemic, the 12 months follow‐up visit could only take place for 13 patients. All patients used corticosteroids at baseline, except for two patients who had temporarily ceased treatment for 6 weeks prior to the visit due to weight gain and non‐compliance.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Healthy controls (n = 13) | DMD patients(n = 17) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15.7 (11.1–20.7) | 13.4 (12.5–16.7) | 0.536 |

| Calculated height (m) | 1.73 (1.47–1.75) | 1.54 (1.47–1.66) | 0.053 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.5 (16.4–22.3) | 27.5 (23.4–31.6) | 0.001 |

| Right‐handed | 12 (92.3%) | 13 (76.5%) | |

| Prednisone intermittent | NA | 8 (47.1%) | |

| Deflazacort intermittent | NA | 8 (47.1%) | |

| Deflazacort daily | NA | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Steroids on‐day at baseline | NA | 7 (41.1%) | |

| Steroids off‐day at baseline | NA | 10 (58.8%) | |

| Age at start steroid use (years) | NA | 5.7 (4.6–8.0) | |

| Age at loss of ambulation (years) | NA | 11.6 (10.1–12.8) range 8.6–18.9 | |

| Time since loss of ambulation (years) | NA | 2.6 (1.4–4.0) |

Values are median (first‐third quartiles) or number of patients (%). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

BMI, body mass index; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

All HCs and 10 DMD patients could maintain the standard position, while three patients had their forearm positioned halfway between pronation and supination. The MRI scans were acquired in supine position in four DMD patients due to discomfort lying on the side, one with the forearm in maximum pronation, and three with their forearm positioned halfway between pronation and supination. Scans in a separate group of HCs showed no or minimal differences in qMRI results between two forearm positions (Figure S2). Interrater variability (Figure S3) showed a mean bias in FF of 0.4%, and 95% limits of agreement −1.3% to 2.0%; for TV, this was 0.4 cm3 (−0.8 to 1.7 cm3); for CV, 0.3 cm3 (−0.8 to 1.5 cm3); and for T2water, 0.1 ms (−0.8 to 0.9 ms).

Four Dixon scans and five MSE scans of DMD patients and four MSE scans of HCs were excluded due to insufficient signal or movement artefacts. Thirteen Dixon scans from patients and HCs and 12 MSE scans from patients and nine from HCs were included in the analyses (refer to the flowchart in Figure S4).

Thenar fat fraction, muscle size, and T2water

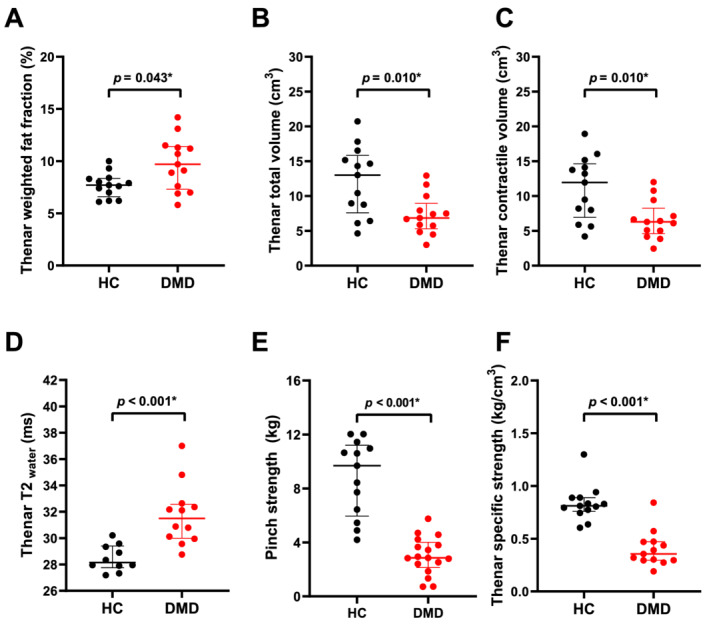

Thenar FF was only slightly elevated in patients compared with HCs (median 9.7 vs. 7.7%, P = 0.043; Figure 2A). By contrast, TV and CV were significantly lower in patients (median 6.9 and 6.3 vs. 13.0 and 11.9 cm3, both P = 0.010; Figure 2B and C), whereas thenar T2water was higher (median 31.5 vs. 28.1 ms, P < 0.001; Figure 2D). The higher thenar T2water in DMD patients could be visually confirmed for all intrinsic hand muscles (Figure S5). In patients, whole thenar TV, CV, and specific strength correlated very strongly (rho = 0.96–0.97) to these same values determined on only the slice with the largest cross‐sectional area (CSA), FF correlated moderately (rho = 0.67; Figure S6).

Figure 2.

Dixon and pinch strength results of healthy controls (HC) compared with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) patients. Thenar weighted fat fraction (FF) (A), total volume (TV) (B), contractile volume (CV) (C), T2water (D), pinch strength (E), and specific strength (F) are presented for healthy controls (HCs; black) and DMD patients (red). TV, CV, specific strength, and pinch strength were lower in DMD patients. T2water was higher compared with HCs, while FF was only slightly elevated. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Uncorrected P values are reported and statistical significance after Bonferroni–Holm correction is shown by *.

Clinical assessments

Clinical assessments at baseline and follow‐up are presented in Table 2. At baseline, pinch strength in patients was lower compared with HCs (Figure 2E), and it decreased significantly over 12 months from median 2.857 to 2.243 kg (Figure 3A). PUL total also significantly decreased from a median of 29 to 23 points. Grip strength declined from median 8.47 to 6.39 kg and PROM total scores from 49 to 44 points, but both were not significant after correction. PUL distal and NRS tiredness and difficulty scores did not show a decline over 12 months. At baseline, all patients scored NRS tiredness score ≤4 (i.e. ‘not really tiring’). Similarly, NRS difficulty score was ≤4 (i.e. ‘not really difficult’) for all patients except two, who scored 5 and 6 (i.e. ‘a little difficult’). Fifteen out of 17 patients were able to play the video game for 10 min at baseline, including the patient with the lowest pinch strength (0.723 kg), and 10 out of 13 patients were able at 12 months follow‐up. Two patients at baseline and one at follow‐up did not want to continue playing after 5 min but were able to play for 10 min at a later study visit. The other two patients at follow‐up refused or quit after 5 min, but claimed to easily play for 10 min.

Table 2.

Clinical assessments in DMD patients at baseline and 12 months follow‐up

| DMD patients | Baseline (n = 17) | 12 months follow‐up (n = 13) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinch strength (kg) | 2.857 (2.137–4.010) | 2.243 (1.930–3.339) | <0.001* |

| Grip strength, kg | 8.47 (5.25–11.08) | 6.39 (4.92–9.93) | 0.016 |

| PUL 2.0 total score, points (max 42) | 29 (20–36) | 23 (17–30) | <0.001* |

| PUL 2.0 shoulder score, points (max 12) | 4 (0–8) | 1 (0–6) | 0.109 |

| PUL 2.0 elbow score, points (max 17) | 13 (10–16) | 11 (7–14) | 0.001* |

| PUL 2.0 distal score, points (max 13) | 11 (10–12) | 11 (10–12) | 0.227 |

| PROM total score, points (max 64) | 49 (36–57) | 44 (30–54) | 0.041 |

| NRS tiring, points (max 10) | 0 (0–1) n = 15 | 1 (0–4) n = 9 | 0.250 |

| NRS difficult, points (max 10) | 0 (0–2) n = 15 | 0 (0–1) n = 9 | 1.000 |

Values are median (first‐third quartiles). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Uncorrected P values are reported and statistical significance after Bonferroni–Holm correction is shown by *. If a certain value was not available for all patient, the number of patients for whom the data were available was presented after the result with n = number.

DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; NRS, numeric rating scale; PROM, patient reported outcome measure; PUL, performance of the upper limb.

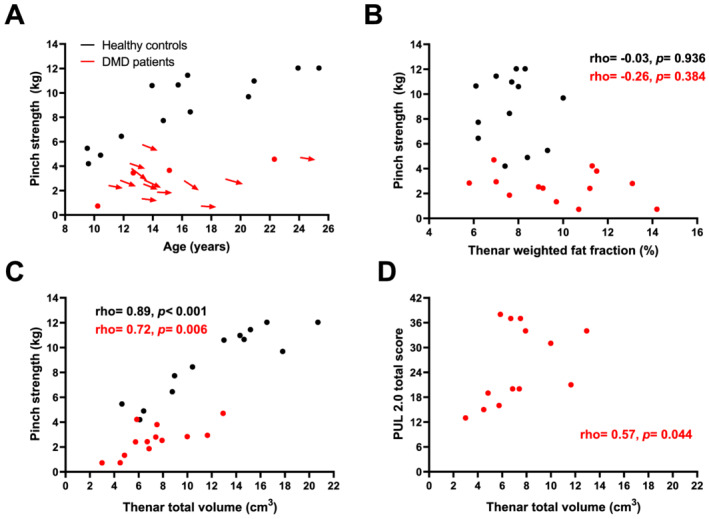

Figure 3.

Pinch strength declines over time and correlates with quantitative MRI muscle size in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). (A) Pinch strength is plotted vs. age for both healthy controls (HC; black) and DMD patients (red). In all patients with 12 months follow‐up data, pinch strength decreased over that time‐period. (B) No clear relation between the plotted thenar fat fraction and pinch strength can be observed. Thenar total volume (TV) is plotted against pinch strength in (C) and performance of the upper limb (PUL) 2.0 total score in (D). A strong correlation between pinch strength and TV in HCs and DMD patients can be observed, as well as a moderate correlation between PUL 2.0 total score and TV in DMD patients.

Relations between quantitative MRI and clinical assessments

Table 3 shows correlations between qMRI parameters and clinical assessments. Apart from the smaller TV and CV, specific strength (kg/cm3) was also significantly lower in patients (median 0.36 vs. 0.81 kg/cm3; Figure 2F). In both groups, FF did not correlate with pinch or grip strength (Figure 3B). In patients, pinch strength correlated strongly with TV (Figure 3C) and moderately with CV. There was a moderate correlation between grip strength and TV and CV, between PUL total and TV (Figure 3D), CV and T2water, between PUL distal and TV and CV, between PROM total and TV and CV, and between NRS tiredness and TV. In HCs, correlations of pinch and grip strength with TV and CV were also strong or very strong.

Table 3.

Correlations between quantitative MRI results and clinical assessments

| Variable | Fat fraction | Total volume | Contractile volume | T2water |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls | ||||

| Pinch strength | rho = −0.03 | rho = 0.89 | rho = 0.89 | rho = −0.39 |

| P = 0.936 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.266 | |

| Grip strength | rho = 0.03 | rho = 0.91 | rho = 0.91 | rho = −0.44 |

| P = 0.936 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.200 | |

| DMD patients | ||||

| Pinch strength | rho = −0.26 | rho = 0.72 | rho = 0.68 | rho = 0.16 |

| P = 0.384 | P = 0.006 | P = 0.010 | P = 0.618 | |

| Grip strength | rho = −0.17 | rho = 0.69 | rho = 0.67 | rho = −0.15 |

| P = 0.578 | P = 0.009 | P = 0.013 | P = 0.633 | |

| PUL 2.0 total score | rho = −0.22 | rho = 0.57 | rho = 0.51 | rho = −0.59 |

| P = 0.480 | P = 0.044 | P = 0.075 | P = 0.043 | |

| PUL 2.0 distal score | rho = −0.35 | rho = 0.58 | rho = 0.53 | rho = 0.10 |

| P = 0.249 | P = 0.039 | P = 0.065 | P = 0.765 | |

| DMD upper limb PROM | rho = −0.32 | rho = 0.55 | rho = 0.52 | rho = −0.03 |

| P = 0.292 | P = 0.051 | P = 0.070 | P = 0.931 | |

| NRS tiredness score | rho = 0.26 | rho = −0.54 | rho = −0.50 | rho = 0.12 |

| P = 0.415 | P = 0.068 | P = 0.101 | P = 0.721 | |

| NRS difficulty score | rho = −0.18 | rho = −0.28 | rho = −0.24 | rho = 0.02 |

| P = 0.569 | P = 0.384 | P = 0.446 | P = 0.951 | |

DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; NRS, numeric rating scale; PROM, patient reported outcome measure; PUL, performance of the upper limb.

Discussion

The thenar muscles were assessed for their value to monitor treatment effects in DMD using qMRI, strength and functional assessments. TV, CV, specific strength, and pinch strength were lower, and T2water was higher in DMD patients compared with HCs, while FF was only slightly elevated. Pinch strength and PUL total decreased significantly over 12 months in DMD patients, and there were moderate to strong correlations of qMRI muscle size with pinch strength and PUL total and distal. Despite this decrease in strength, operating a game controller was still possible for all our participants.

In DMD, hand function is preserved, years after loss of ambulation and the ability to raise the arms. 2 Previous qMRI studies support this pattern of decline on a tissue level by showing a proximal to distal involvement, where thigh, shoulder, and upper arm muscles are, on average, more affected than lower leg and forearm muscles. 29 , 30 Hand function and corresponding activities are vital for independence, for example, operating a wheelchair and using a smart phone or computer, and for entertainment. Compared with ambulant patients, non‐ambulant patients spend significantly more time (in total 2–4 h/day) on playing (online) video games, which in recent years has become an important tool for social interaction. 7

Drugs that preserve muscle and make use of dystrophin products are assumed to have the greatest effect on progression at an early disease stage, because they rely on the presence of sufficient muscle tissue. 4 , 5 In addition, measurable disease progression is of vital importance to detect this potential preserving effect of a drug. All aspects of the thenar muscles that were assessed in this study pointed towards a relative preservation of the thenar muscles, and some also showed measurable disease progression: tissue characteristics as measured by qMRI, strength via pinch strength, function by assessing PUL and PROM, and activities in daily life via playing a video game. On the tissue level, we found a slightly increased FF and an elevated T2water in the thenar muscles of DMD patients. T2water reflects active pathological processes, such as inflammation, myocyte swelling, oedema, and necrosis, 16 and previous qMRI studies of lower extremity muscles showed that young DMD patients have limited fat replacement and elevated T2water. 15 , 31 Other qMRI techniques might show early signs of muscle pathology and treatment effects in DMD, such as ionic dysregulation by sodium MRI, 32 or pH or phosphodiester alterations by 31P or 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. 33 , 34 Thenar muscle volume was clearly reduced compared with HCs, which could be inherent to the dystrophic process or related to long‐term corticosteroid use. 1 , 35

For the second aspect, muscle strength, we observed a decline in pinch strength over 12 months in our non‐ambulant cohort, which is in agreement with the slightly older and weaker cohort described by Seferian et al. 36 As onset of weakness in pinch strength can already be quantified in preschool infants with DMD, 37 this process is apparently slow. The higher baseline pinch strength in our cohort compared with literature could be explained by the younger age at inclusion in the present study, and higher age at and shorter duration since loss of ambulation, and more consistent corticosteroid use. 36 The lower specific strength we observed was also reported in other muscles of DMD patients as well as in other muscular dystrophies. 30 , 38 , 39 The strong correlation between muscle size and strength suggests that therapies that manage to increase muscle volume have the potential to also increase muscle strength. 40

The PUL 2.0 total has been accepted as a primary endpoint in non‐ambulant DMD (e.g. NCT03406780 and NCT04371666). We showed quantifiable disease progression on function level in the upper extremity, reflected by a decline in the PUL 2.0 total within the same range of the non‐ambulant cohort of Pane et al. 41 A decline in PUL distal was reported in a much larger cohort over 24 months, but this was small (0.8 points), not reported as significant and therefore arguably not clinically relevant. 41 We did not observe a decline in the distal domain, supporting the preservation of hand function. The decline in PUL total was not reflected in a significant decline in PROM total score in our data, which could have been caused by our small cohort. Ultimately, it is important that therapies are shown to have an effect on activities in daily life, especially from a regulatory and patient's perspective. 4 Therefore, we studied the ability to play video games for 10 min using a game controller as clinical endpoint. None of the patients had reached this endpoint during our study, although some patients were not motivated to complete the 10 min or preferred smaller game controllers than used in the current setup. Therefore, the search for a direct connection between results on tissue characteristics, strength, and function level with this or another robust clinical endpoint will be continued.

Obtaining qMRI data of the thenar muscles in non‐ambulant DMD patients led to some challenges and technical considerations. Contractures of knee flexion, shoulder extension and internal rotation, forearm pronation, and wrist flexion caused difficulties in maintaining the desired standardized position or any comfortable position in the MRI scanner. To address the effects of this on our outcome parameters, we studied the effect of two forearm positions on qMRI results separately and found that thenar FF and T2water were comparable between both positions (supporting information). Even though TV and CV differed significantly between positions, average differences were small (0.55–0.63 cm3). We also found that TV and CV correlated strongly with these same values determined on only the slice with the largest CSA (supporting information), indicating that (contractile) CSA can be used as a proxy for whole muscle values. Thenar FFs, however, should always be determined via whole muscle analysis, as correlations between single slice and whole muscle were moderate for thenar FF. This could be explained by the known proximal‐distal differences in fat replacement in DMD. 42 , 43 Furthermore, both the small size of the hand and positioning away from the centre of the MRI scanner led to reductions in image quality. The best scan quality was observed when patients were positioned on the right side with the arm placed beside the body with either the elbow in 90° flexion and the forearm halfway between pronation and supination, or the elbow in maximum extension and the forearm in any comfortable position. However, the more severely affected patients in our study were often unable to lie on their right side, which makes the use of qMRI of the thenar muscles as biomarker challenging when using a conventional MR scanner. Drawing ROIs consistently may be challenging because of the small size of the thenar muscles, but the low interrater variability showed that this did not influence our qMRI results. The positioning away from the centre of the MRI scanner resulted in both DMD patients and HCs in difficulties with obtaining sufficient B1 for the MSE scans. However, as the T2water values in all intrinsic hand muscles in DMD were also elevated, and values in our HCs are comparable with those of our previous study in upper arm and lower extremity muscles, 22 we are confident that the analysis was sound.

In conclusion, the minimal fat replacement within the thenar muscles and increased T2water indicate that the thenar muscles are in an early stage of muscle pathology in this cohort of non‐ambulant patients. The simultaneous decrease in pinch strength and PUL total over 1 year shows that there is measurable disease progression within the possible duration of a clinical trial. Together with the correlation between muscle size and function, these results indicate that the thenar muscles are a valuable and quantifiable target for systemic or local therapy in later stages of the disease.

Funding

This work was supported by the Stichting Spieren for Spieren (grant SvS15).

Conflicts of interest

K.J.N., K.R.K., A.S.D.S.M., T.T.J.V., N.M.V., J.B., and J.J.G.M.V. report no relevant disclosures. M.H. reports paid consultancy for ATOM International Ltd. outside the submitted work. E.H.N. reports ad hoc consultancies for WAVE, Santhera, Regenxbio, and PTC, and he worked as investigator of clinical trials of Italfarmaco, NS Pharma, Reveragen, Roche, WAVE, and Sarepta outside the submitted work. HEK reports research support from Philips Healthcare during the conduct of the study, consultancy for PTC therapeutics and Esperare, and trial support from ImagingDMD‐UF outside the submitted work. All reimbursements from E.H.N. and H.E.K. were received by the LUMC. No personal financial benefits were received.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Example of a participant and forearm positioned in maximum pronation.

Figure S2. Thenar qMRI results in different forearm positions.

Figure S3. Interrater variability for thenar qMRI results.

Figure S4. Flowchart of MRI data inclusion.

Figure S5. T2water of all hand muscles for HCs and DMD patients.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Stichting Spieren for Spieren (grant SvS15) for funding this work. The authors are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Neuromuscular Diseases (ERN EURO‐NMD). The authors of this manuscript certify that they comply with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 44

Naarding K. J., Keene K. R., Sardjoe Mishre A. S. D., Veeger T. T. J., van de Velde N. M., Prins A. J., Burakiewicz J., Verschuuren J. J. G. M., van der Holst M., Niks E. H., and Kan H. E. (2021) Preserved thenar muscles in non‐ambulant Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients, Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 12, 694–703, 10.1002/jcsm.12711

Erik H. Niks and Hermien E. Kan contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Cros D, Harnden P, Pellissier JF, Serratrice G. Muscle hypertrophy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. A pathological and morphometric study. J Neurol 1989;236:43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McDonald CM, Henricson EK, Abresch RT, Duong T, Joyce NC, Hu F, et al. Long‐term effects of glucocorticoids on function, quality of life, and survival in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2018;391:451–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verhaart IEC, Aartsma‐Rus A. Therapeutic developments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Rev Neurol 2019;15:373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. CHMP . Guideline on the clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. In European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2015/12/WC500199239.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2020.

- 5. CDER, CBER . Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Related Dystrophinopathies: Developing Drugs for Treatment. Guidance for Industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/92233/download . Accessed on May 1, 2019. US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) 2018.

- 6. Connolly AM, Malkus EC, Mendell JR, Flanigan KM, Miller JP, Schierbecker JR, et al. Outcome reliability in non‐ambulatory boys/men with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 2015;51:522–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heutinck L, Kampen NV, Jansen M, Groot IJ. Physical activity in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy is lower and less demanding compared to healthy boys. J Child Neurol 2017;32:450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duncan SF, Saracevic CE, Kakinoki R. Biomechanics of the hand. Hand Clin 2013;29:483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barnard AM, Willcocks RJ, Triplett WT, Forbes SC, Daniels MJ, Chakraborty S, et al. MR biomarkers predict clinical function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2020;94:e897–e909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naarding KJ, Reyngoudt H, van Zwet EW, Hooijmans MT, Tian C, Rybalsky I, et al. MRI vastus lateralis fat fraction predicts loss of ambulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2020;94:e1386–e1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rooney WD, Berlow YA, Triplett WT, Forbes SC, Willcocks RJ, Wang DJ, et al. Modeling disease trajectory in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2020;94:e1622–e1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hogrel JY, Wary C, Moraux A, Azzabou N, Decostre V, Ollivier G, et al. Longitudinal functional and NMR assessment of upper limbs in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2016;86:1022–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ricotti V, Evans MR, Sinclair CD, Butler JW, Ridout DA, Hogrel JY, et al. Upper limb evaluation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: fat‐water quantification by MRI, muscle force and function define endpoints for clinical trials. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Willcocks RJ, Triplett WT, Forbes SC, Arora H, Senesac CR, Lott DJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the proximal upper extremity musculature in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol 2017;264:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arpan I, Willcocks RJ, Forbes SC, Finkel RS, Lott DJ, Rooney WD, et al. Examination of effects of corticosteroids on skeletal muscles of boys with DMD using MRI and MRS. Neurology 2014;83:974–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carlier PG. Global T2 versus water T2 in NMR imaging of fatty infiltrated muscles: different methodology, different information and different implications. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24:390–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van den Bergen JC, Ginjaar HB, van Essen AJ, Pangalila R, de Groot IJ, Wijkstra PJ, et al. Forty‐five years of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in the Netherlands. J Neuromuscul Dis 2014;1:99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hamilton G, Yokoo T, Bydder M, Cruite I, Schroeder ME, Sirlin CB, et al. In vivo characterization of the liver fat (1)H MR spectrum. NMR Biomed 2011;24:784–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spottiswoode B . 2D phase unwrapping algorithms. https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/22504‐2d‐phase‐unwrapping‐algorithms. Retrieved November 1, 2020: MATLAB Central File Exchange; 2020.

- 20. Gold GE, Han E, Stainsby J, Wright G, Brittain J, Beaulieu C. Musculoskeletal MRI at 3.0 T: relaxation times and image contrast. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weigel M. Extended phase graphs: dephasing, RF pulses, and echoes ‐ pure and simple. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;41:266–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keene KR, Beenakker JM, Hooijmans MT, Naarding KJ, Niks EH, Otto LAM, et al. T2 relaxation‐time mapping in healthy and diseased skeletal muscle using extended phase graph algorithms. Magn Reson Med 2020;84:2656–2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gauld LM, Kappers J, Carlin JB, Robertson CF. Height prediction from ulna length. Dev Med Child Neurol 2004;46:475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Servais L, Deconinck N, Moraux A, Benali M, Canal A, Van Parys F, et al. Innovative methods to assess upper limb strength and function in non‐ambulant Duchenne patients. Neuromuscul Disord 2013;23:139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mayhew AG, Coratti G, Mazzone ES, Klingels K, James M, Pane M, et al. Performance of upper limb module for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klingels K, Mayhew AG, Mazzone ES, Duong T, Decostre V, Werlauff U, et al. Development of a patient‐reported outcome measure for upper limb function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: DMD upper limb PROM. Dev Med Child Neurol 2017;59:224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs 1988;14:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mukaka MM. Statistics corner: a guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J 2012;24:69–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Forbes SC, Arora H, Willcocks RJ, Triplett WT, Rooney WD, Barnard AM, et al. Upper and lower extremities in Duchenne muscular dystrophy evaluated with quantitative MRI and proton MR spectroscopy in a multicenter cohort. Radiology 2020;295:616–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wokke BH, van den Bergen JC, Versluis MJ, Niks EH, Milles J, Webb AG, et al. Quantitative MRI and strength measurements in the assessment of muscle quality in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hooijmans MT, Niks EH, Burakiewicz J, Verschuuren JJ, Webb AG, Kan HE. Elevated phosphodiester and T2 levels can be measured in the absence of fat infiltration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. NMR Biomed 2017;30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gerhalter T, Gast LV, Marty B, Martin J, Trollmann R, Schussler S, et al. (23) Na MRI depicts early changes in ion homeostasis in skeletal muscle tissue of patients with duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;50:1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hooijmans MT, Doorenweerd N, Baligand C, Verschuuren J, Ronen I, Niks EH, et al. Spatially localized phosphorous metabolism of skeletal muscle in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients: 24‐month follow‐up. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182086. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reyngoudt H, Turk S, Carlier PG. (1) H NMRS of carnosine combined with (31) P NMRS to better characterize skeletal muscle pH dysregulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed 2018;31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schakman O, Gilson H, Kalista S, Thissen JP. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy induced by glucocorticoids. Horm Res 2009;72:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seferian AM, Moraux A, Annoussamy M, Canal A, Decostre V, Diebate O, et al. Upper limb strength and function changes during a one‐year follow‐up in non‐ambulant patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an observational multicenter trial. PLoS One 2015;10:e0113999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mattar FL, Sobreira C. Hand weakness in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and its relation to physical disability. Neuromuscul Disord 2008;18:193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lokken N, Hedermann G, Thomsen C, Vissing J. Contractile properties are disrupted in Becker muscular dystrophy, but not in limb girdle type 2I. Ann Neurol 2016;80:466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marra MA, Heskamp L, Mul K, Lassche S, van Engelen BGM, Heerschap A, et al. Specific muscle strength is reduced in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: an MRI based musculoskeletal analysis. Neuromuscul Disord 2018;28:238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bettica P, Petrini S, D'Oria V, D'Amico A, Catteruccia M, Pane M, et al. Histological effects of givinostat in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 2016;26:643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pane M, Coratti G, Brogna C, Mazzone ES, Mayhew A, Fanelli L, et al. Upper limb function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: 24 month longitudinal data. PLoS One 2018;13:e0199223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hooijmans MT, Niks EH, Burakiewicz J, Anastasopoulos C, van den Berg SI, van Zwet E, et al. Non‐uniform muscle fat replacement along the proximodistal axis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 2017;27:458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chrzanowski SM, Baligand C, Willcocks RJ, Deol J, Schmalfuss I, Lott DJ, et al. Multi‐slice MRI reveals heterogeneity in disease distribution along the length of muscle in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Myol 2017;36:151–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. von Haehling S, Morley JE, Coats AJS, Anker SD. Ethical guidelines for publishing in the journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle: update 2019. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019;10:1143–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Example of a participant and forearm positioned in maximum pronation.

Figure S2. Thenar qMRI results in different forearm positions.

Figure S3. Interrater variability for thenar qMRI results.

Figure S4. Flowchart of MRI data inclusion.

Figure S5. T2water of all hand muscles for HCs and DMD patients.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data and analysis software can be made available to qualified investigators on request.