Abstract

According to GLOBOCAN 2018 data Colorectal cancer (CRC) represents the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world and has the second-highest mortality rate. The incidence of CRC has been rising worldwide, the majority of cases being in developing countries mostly due to the adoption of an unhealthy lifestyle. The main driving factors behind CRC are a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, red meat consumption, alcohol, and tobacco; however, early detection screenings and standardized treatment options have reduced CRC mortality. Better family history and genetic testing can help those with a hereditary predisposition in taking preventative measures.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Risk factors, Epidemiology, Inherited Colorectal Cancer

Introduction

In 2018, colorectal cancer (CRC) accounted for 1,026,215 and 823,303 new cancer cases in men and women, respectively, ranking third in incidence, situated behind breast and lung cancer and second in mortality, after lung cancer with a number of 880,792 in both men and women [1].

The possibility of developing CRC is around 5% and has been linked to dietary habits, lifestyle, and phenotype. CRC has been classified into familial (30%) and sporadic (70%) based on the mutation origin [2].

A persistent increase in mortality and also new cases in younger adults (below 50 years of age) has been reported in the past few years, a fact that can be attributed to the development of better screening methods.

Dietary habits and lifestyle can induce intestinal inflammation and alterations in the intestinal microflora facilitating polyp growth based on an immune response, in time these polyps can turn cancerous. Hyper-proliferation and finally carcinogenesis can develop by spontaneous or hereditary mutations in tumour-suppressor genes and oncogenes, thus lifestyle changes, genetic testing, and early cancer screening are essential in CRC prevention.

Taking into account all nations and ages, males present a higher incidence than females, about 1.5 times higher [2].

The gender variation among older adults has shifted in recent years mirroring that seen in young adults, also regarding sex women seem to be prone to CRC affecting the ascending colon, while men tend to present more with proximal and rectal CRC. The right-sided localization of CRC is more aggressive than the left-sided localization [4].

Taking into account age, it is shown that older adults (over 65 years of age) have a higher probability of being diagnosed with CRC than adults between 50-64 years of age,75% higher, and also higher than young adults (25-49 years old) around 30% higher [3].

A significant risk factor for colorectal neoplasia is represented by a family history of CRC. In about 20% of cases with adenomatous polyps or CRC, a family background of these neoplasms has been found, and in about 55% of cases with CRC hereditary genetic alterations have been recognized [5].

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) is represented by many precancerous polyps, hundreds or thousands, with colon and rectum localization. FAP is an uncommon, autosomal dominant disease, typically connected with the development of colorectal polyps. This disease has an incidence of 1:8000 and represents under 1% of all colorectal cancers [6].

Adenomatous polyps typically develop in the first or second decade of life, and, whenever left untreated, it can progress to CRC. Also, other extracolonic neoplasia has a higher rate of incidence in FAP [7,8].

The association between obesity and CRC is highly debated as the prevalence of obesity continues to rise. The accepted measure of obesity is the body mass index (a person’s weight expressed in kilograms, divided by the square of height expressed in meters). A high BMI can indicate obesity but there are cases in which it is not relevant (ascites, large tumours) [9,10].

Tobacco smoking has been correlated with a high risk of developing adenomas and hyperplastic polyps and in 2009 the International Agency for the Research of Cancer stated that tobacco smoking is a risk factor for CRC. Smoking, correlated also to lung cancer, the number one cancer in mortality worldwide, is the number one preventable cancer risk factor [11].

Material and Methods

The study conducted was both a retrospective and prospective study. We included 132 patients in our study who were referred to the “Renasterea” Private Clinic and the Department of Internal Medicine of the Emergency County Hospital Craiova between 2015 and 2020. All patients gave a written informed consent prior to being included in the study and were informed of the procedures of the study, and of the fact that they could at any point, withdraw their consent. The protocol of the study was designed according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova.

After clinical evaluation, all patients underwent colonoscopy, followed by biopsies. A histopathological exam was performed for all biopsies. The BMI was evaluated using the standardized formula of calculus. All patients received a questionnaire where risk and hereditary factors were evaluated. All data obtained was stored in Microsoft Excel files (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA®) and was statistically analysed in order to investigate the relationship between the onset of colorectal cancer and the risk factors identified (obesity, cigarette smoking, family history). Numerical data were reported as mean±standard deviation of the values. The graphical representation and calculation of the regression coefficients were performed with Excel, Pivot tables using the controls, functions, statistics, chart, and data analysis module.

Results

The contribution of each risk factor to the overall estimation of CRC risk is described in detail below and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Obesity, smoking, and family history in patients with colorectal cancer

|

Risk Factor |

Relative risk |

Confidence interval |

P-value for chi-square test |

|

|

BMI |

Overall |

1.5111 |

1.1299 to 2.0210 |

0.00444 |

|

Male, CRC |

2.5879 |

1.6743 to 4.0002 |

0.00001 |

|

|

Female, CRC |

1.9231 |

1.0016 to 3.6923 |

0.0407 |

|

|

Smoking |

Overall |

2.0000 |

1.3056 to 3.0637 |

0.0014 |

|

Male, CRC |

2.0625 |

1.2313 to 3.4549 |

0.0060 |

|

|

Female, CRC |

1.8750 |

0.8796 to 3.9967 |

0.1036 |

|

|

Family History |

Overall |

3.6391 |

1.0388 to 12.7489 |

0.0434 |

|

Male, CRC |

4.5000 |

1.0024 to 20.2017 |

0.0496 |

|

|

Female, CRC |

1.9216 |

0.1799 to 20.5201 |

0.5888 |

|

Obesity

The correlation between CRC risk and obesity was studied using data from 132 colorectal cancer cases. Among the male patients, 48 had a higher BMI than 24.99 (range 25-45), in female patients 20 had a higher BMI (range 25-35) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Obesity among colorectal patients and control group

The association between obesity and CRC in our male patients (Relative risk=2.5879, 95% CI=1.6743 to 4.0002) was stronger than the association for female patients (Relative risk=1.9231,95% CI=1.0016 to 3.6923). The RR is significant (RR=1.5111,95% CI: 1.1299 to 2.0210), and the heterogeneity also (P, 0.00444). These results show there is a positive association between obesity and CRC risk.

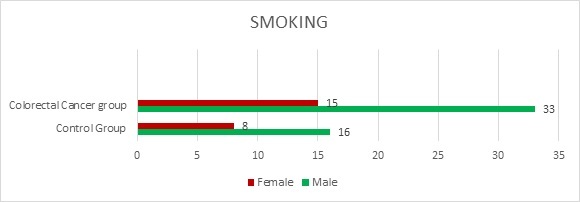

Tobacco (Cigarette Smoking)

In total, 48 patients smoke or smoked prior to the diagnosis, 62.5% were men. Our analytic sample included 72% never, 70 % former, and 29% current smokers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Smoking among female and male colorectal cancer patients and control group

When compared with never smoking, significant associations between smoking (former or current) and never smoked (RR=2; 95% CI=1.3056 to 3.0637) were found. Also, it was shown that male smokers have a higher risk than female smokers.

Family History

The association between the CRC risk in patients presenting a history of this neoplasia in first-degree relatives or a family history of CRC was studied. The risk for developing CRC was higher in individuals with a family history in comparison to the ones without (RR=3.6391, 95% CI: 1.0388 to 12.7489). In our study, 11 patients showed a history of CRC in relatives, among whom three have Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Family history in patients with colorectal cancer

Gender and age

We examined the correlation between sex and age in our study group, the ratio between male and female was 1.87 (85 males, 47 females) with an age range between 33 and 87 (mean age 60±2 years). Considering all ages, males are shown to have a higher chance of developing CRC than females.

The ratio between older adults (65+) and young adults (age between 30-65) was 1.17 in males (46 males over 65, 39 males under 65) and 1.6 in females (29 females over 65, 18 females under 65). In our study, we have found a high similarity in incidence rate for CRC between older (above 65 years of age) and younger (below 65 years of age) patients.

Cancer localization

In our study of 134 cases of CRC, 84 patients presented with rectum localization of the neoplasm, 32 with a left localization, and 16 with a right localization; from the 84 patients with rectal cancer 55 were male and 29 female (ratio M/F: 1.89), from the 32 with a left localization 25 were male and just 7 were female (ratio M/F: 3.57) and from the 16 patients with a right localization 10 were female and 6 were male (ratio F/M: 1.66) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Localization of Colorectal Cancer

Discussions

In the past several years, colorectal cancer has become a global health crisis, with more and more new cases being diagnosed each year. Additionally, CRC has been recently placed second in mortality worldwide, after lung cancer. Nowadays, with immunotherapy and genetic testing [12] knowing how risk factors impact CRC has a high significance in the development and treatment of this disease.

In this retrospective cohort study, the differential associations between risk factors of colorectal cancer were explored. We did observe that there is an important association between all of these factors and the presence of CRC in patients.

Regarding obesity there is a high risk for the overall patient cohort in comparison with the normal group, additionally there is a higher risk for male compared to female patients.

Based on our literature search, our findings were in accordance, with the difference that the risk was higher in both male and female patients [13,14,15,16,17].

The International Agency for the Research of Cancer (IARC) concluded that tobacco smoking is a risk factor for CRC, with a relative risk of 1.18, in patients that are regular smokers, statement released in 2009 [11], after five years prior it reported that tobacco smoking cannot be definitively associated with the development of CRC [18,19]. In our study, we have found a substantial risk for CRC in our overall patients (i.e., a RR of 2).

For these two factors, a possible explanation for the high risk could be the socio-economic status.

Some groups of patients present an increased risk for CRC: patients with intestinal polyps or inflammatory bowel disease, patients with a relative affected by FAP, and patients that are not part of the first two categories but include a family history of CRC [14]. In our study group, we have found both FAP patients (a lower number of cases), and patients that are not part of families with an autosomal dominant colorectal disease. The overall risk for these patients is high (i.e., a RR of 3.6) compared to the control group. The risk for female patients with a family history of CRC was lower than for male patients, this can be attributed to the larger number of males in proportion to females that was enlisted into the CRC group.

Regarding sex and age in CRC, we have found that males are more prone to develop CRC, as was also found in our literature search [20,21], with a lower starting age than females (33 years for male and 46 for female). Also, we have found the incidence rate of CRC in young adults (before 65 years) almost the same as in old adults (over 65 years) [22].

The majority of tumours (88%) were located distal to the splenic flexure, with 63% involving the rectum. Proximal (right colon) cancers were noted in only 22% of patients.

Our results are different from the literature search, the number of distal localizations was higher compared to the proximal localization [21], and the incidence of rectum cancer was also higher in our CRC group, also in discordance with the literature search [23]. Also, we have found that more females had a proximal localization of CRC, with males being prone to a distal or rectal localization, which is in accordance with literature [20].

Conclusions

Through this paper, we have tried to show the importance of risk factors in patients with colorectal cancer depending on their age, sex, smoking habits, BMI, and genetic inheritance.

All of these factors have presented a significant correlation with the development of colorectal cancer, except for cigarette smoking.

In conclusion, there can be a sustained reduction in colorectal cancer development with knowing risk factors and screening.

Also, knowledge of the genetic risk assists in specific investigations, management, and treatment of those affected by CRC and their relatives.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Globocan Global Cancer Observatory, 2018, Cancer Today. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr[Accessed 20.07.2020]

- 2.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61(5):759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Our World in Data, 2019. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/cancer[Accessed July 2020]

- 4.Overbeek JA, Kuiper JG, van der Heijden AAWA, Labots M, Haug U, Herings RMC, Nijpels G. Sex-and site-specific differences in colorectal cancer risk among people with type 2 diabetes. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34(2):269–276. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3191-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burt Randall NDW. Genetic Testing for Inherited Colon Cancer. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2005;128(6):20–20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Chapelle A. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2004;4(10):769–780. doi: 10.1038/nrc1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knudsen AL, Bisgaard ML, Bülow S. Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis (AFAP): a review of the literature. Familial Cancer. 2003;2(1):43–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1023286520725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King JE, Dozois RR, Lindor NM, Ahlquist DA. Care of patients and their families with familial adenomatous polyposis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(1):57–67. doi: 10.4065/75.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deurenberg P, Yap M, van Staveren WA. Body mass index and percent body fat: a meta-analysis among different ethnic groups. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22(12):1164–1171. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karahalios A, Simpson JA, Baglietto L, MacInnis RJ, Hodge AM, Giles GG, English DR. Change in weight and waist circumference and risk of colorectal cancer: results from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:157–157. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Smoking and Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(23):2765–2778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Florescu-ţenea RM, Kamal AM, Mitruţ P, Mitruţ R, Ilie DS, Nicolaescu AC, Mogoantă L. Colorectal Cancer: An Update on Treatment Options and Future Perspectives. Curr Health Sci J. 2019;45(2):134–141. doi: 10.12865/CHSJ.45.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Zhang P, Shi C, Zou Y, Qin H. Obesity and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(1):e53916–e53916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebecca A, Barnetson MGD. In: Colorectal Cancer. Cassidy J, Johnston P, Van Cutsem E, editors. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2006. Genetic Susceptibility to Colorectal Cancer; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(2):89–103. doi: 10.5114/pg.2018.81072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aleksandrova K, Nimptsch K, Pischon T. Obesity and colorectal cancer. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2013;5:61–77. doi: 10.2741/e596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitlock K, Gill RS, Birch DW, Karmali S. The Association between Obesity and Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2012;2012:768247–768247. doi: 10.1155/2012/768247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ordóñez-Mena JM, Walter V, Schöttker B, Jenab M, O'Doherty MG, Kee F, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Peeters PHM, Stricker BH, Ruiter R, Hofman A, Söderberg S, Jousilahti P, Kuulasmaa K, Freedman ND, Wilsgaard T, Wolk A, Nilsson LM, Tjønneland A, Quirós JR, van Duijnhoven FJB, Siersema PD, Boffetta P, Trichopoulou A, Brenner H, Consortium on H. Ageing: Network of Cohorts in E. the United S Impact of prediagnostic smoking and smoking cessation on colorectal cancer prognosis: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from cohorts within the CHANCES consortium. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(2):472–483. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IARC . In: Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. IARC Working Group, editor. Lyon: WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2004. Colorectal cancer; pp. 615–621. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White A, Ironmonger L, Steele RJC, Ormiston-Smith N, Crawford C, Seims A. A review of sex-related differences in colorectal cancer incidence, screening uptake, routes to diagnosis, cancer stage and survival in the UK. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):906–906. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy G, Devesa SS, Cross AJ, Inskip PD, McGlynn KA, Cook MB. Sex disparities in colorectal cancer incidence by anatomic subsite, race and age. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(7):1668–1675. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abualkhair WH, Zhou M, Ahnen D, Yu Q, Wu X-C, Karlitz JJ. Trends in Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer in the United States Among Those Approaching Screening Age. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(1):e1920407–e1920407. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers EA, Feingold DL, Forde KA, Arnell T, Jang JH, Whelan RL. Colorectal cancer in patients under 50 years of age: a retrospective analysis of two institutions' experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(34):5651–5657. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]