Abstract

To measure the heart rate of unrestrained sea turtles, it has been believed that a probe must be inserted inside the body owing to the presence of the shell. However, inserting the probe is invasive and difficult to apply to animals in the field. Here, we have developed a non-invasive heart rate measurement method for some species of sea turtles. In our approach, an electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed using an animal-borne ECG recorder and two electrodes—which were electrically insulated from seawater—pasted on the carapace. Based on the measured ECG, the heartbeat signals were identified with an algorithm using a band-pass filter. We implemented this algorithm in a user-friendly program package, ECGtoHR. In experiments conducted in a water tank and in a lagoon, we successfully measured the heart rate of loggerhead, olive ridley and black turtles, but not green and hawksbill turtles. The average heart rate of turtles when resting underwater was 6.2 ± 1.9 beats min–1 and that when moving at the surface was 14.0 ± 2.4 beats min–1. Our approach is particularly suitable for endangered species such as sea turtles, and has the potential to be extended to a variety of other free-ranging species.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Measuring physiology in free-living animals (Part I)’.

Keywords: electrocardiogram, heart rate, sea turtle, biologging, non-invasive measurement

1. Introduction

Heart rate measurement is an essential means for studying the physiological status of free-ranging animals. This approach is especially important when studying the physiological adaptation for diving [1–3]. In marine mammals and seabirds, extensive research has revealed interesting adaptations for diving, such as bradycardia during dives and tachycardia at the sea surface [4,5]. Among diving reptiles, sea turtles perform deep and prolonged dives. Therefore, the diving of sea turtles can be a good comparison for the diving of endotherms, marine mammals and seabirds. In fact, many studies have been conducted on the diving behaviour of reptiles, including sea turtles [6]. On the other hand, very few studies have investigated the physiological aspects of diving reptiles. For instance, the heart rates of free-ranging diving reptiles in the field have only been reported in sea snakes [7], American alligators [8], freshwater crocodiles [9] and leatherback sea turtles [10]. Owing to the lack of studies regarding the physiological adaptation for diving in reptiles, there is a gap in the present knowledge on this paramount topic.

The main difficulty in measuring the heart rate of sea turtles is due to the presence of the shell. The heart rate can be measured using an electrocardiogram (ECG) or pulse wave analysis [11,12]. It is believed that the signals from these tests are completely blocked by hard tissues, such as bone, carapace and plastron. Therefore, in all studies measuring the heart rate of unrestrained sea turtles, a probe has been inserted inside the body by methods such as surgical operation [10,12–14]. This approach leaves two points to be overcome. First, surgical operation is invasive; when the turtle shell is drilled and the probe inserted, it takes two weeks to heal the wound owing to the low metabolic rate of reptiles [14]. Second, when the probe is placed inside the body, the probe must be firmly secured to the body and not displace spontaneously. If this is not the case, seawater can enter the body and may cause severe inflammation. This point greatly reduces the applicability of this approach to wildlife. When studying wildlife with a biologging approach, it is sometimes difficult to capture the animal twice (i.e. for the attachment and retrieval of the tag). In such cases, the tag attached to the animal can be scheduled to drop off of the individual, and then be retrieved without a second capture [15,16]. However, this could be problematic if a part of the tag remains inside the body, especially for endangered species like sea turtles. Thus, the automatic tag-releasing approach is not currently favourable for heart rate measurement.

To address these issues, we have developed a non-invasive heart rate measuring system for some species of sea turtles. This novel approach achieved ECG measurement with electrodes pasted on the carapace. Thus, nothing will remain inside the body when the tag detaches naturally. The measurement system consisted of an ECG recorder, two electrodes and a signal processing program. Because the ECG voltage detected on the carapace was very weak, we developed a new signal processing algorithm to extract heartbeats from a noisy signal.

2. Material and methods

(a) . Animals

In this study, five loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta), three green turtles (Chelonia mydas), one black turtle (Chelonia mydas agassizii), one olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) and one hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) were used (electronic supplementary material, table S1). The average body mass was 41 ± 23 kg (15–96 kg) and the sexes of the turtles were not determined. Two green, one olive ridley and one hawksbill turtles were kept in the Suma Aqualife Park Kobe aquarium (Kobe, Japan). The experiment was performed in a water tank (width, length and depth: 5 × 3 × 1 m) in the aquarium for the green and hawksbill turtles, and an artificial lagoon near the aquarium (250 × 80 × 4 m) for the olive ridley turtle. The turtle in the lagoon was captured by snorkelling when attaching and retrieving tags. Five loggerhead, one green and one black turtles were incidentally caught in the set nets of fisheries activities along the Sanriku Coast in Japan [17,18]. Once safely rescued, the turtles were immediately transferred to the marine station of the University of Tokyo (International Coastal Research Centre, Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo; 39.35° N, 141.92° E), located ca 20 km from the set nets. For temporary rehabilitation, the turtles were kept individually in water tanks (1 × 2 × 1 m), and the experiments were performed in each tank. This study was conducted as a part of a tag and release programme, in which loggerhead turtles caught by set nets as bycatch along the Sanriku Coast were handed over to researchers by fishermen. All individual turtles had plastic and metal ID tags applied, and were released after a rehabilitation period ranging from one to four weeks. The water temperature during the experiments in Kobe and on the Sanriku Coast was 20.8 ± 3.7°C (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

(b) . Electrocardiogram recorder and accelerometer

The ECG was recorded using an ECG recorder (W400-ECG; Little Leonardo, Tokyo, Japan). The device was cylindrical, 21 mm in diameter and 109 mm in length, and the mass was 60 g in air. Lead wires for electrode connection extended from the device. The voltage span of the input signal was ± 5.8 mV. The device provided 12-bit analogue–digital (AD) conversion and a 2 GB memory. The ECG was recorded at 100 or 500 Hz. We also recorded the activity of the turtles by accelerometer (M190L-D2GT; Little Leonardo). The shape of this device was also cylindrical (15 mm in diameter and 53 mm in length) and the mass was 18 g in air. Using an accelerometer, we recorded the longitudinal acceleration at 16 Hz, temperature at 1 Hz and depth at 1 Hz.

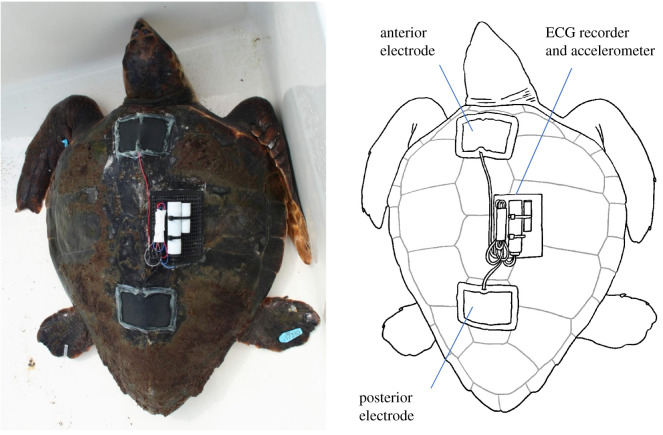

In addition to the ECG recorder and accelerometer, the measurement system included electrodes, rubber sheets and a plastic mesh used to attach the recorders on the carapace (see below; figure 1; electronic supplementary material, movie S1). In total, the mass of the whole system was 150 g in air.

Figure 1.

A loggerhead turtle equipped with an ECG recorder and accelerometer. Two electrodes were pasted onto the carapace, and covered with black rubber sheets. The recorders were attached to the middle of the carapace and connected to the electrodes with lead wires. (Online version in colour.)

(c) . Tag attachment and retrieval

Adhesive tape made of electro-conductive fabric (KNZ-ST50 shield cloth tape; Kyowa Harmonet Ltd, Kyoto, Japan) was cut into squares (7 × 5 cm) and used as electrodes placed on the carapace of the turtles. Lead wires were attached to the ends of the electrodes with the same adhesive tape.

Two electrodes were used and the voltage difference between these electrodes was measured as the ECG signal. The electrodes were placed on the midline anterior and posterior parts of the carapace (figure 1). The anterior electrode was used as the negative electrode and was located close to the heart. The posterior electrode was used as both the positive and earth electrodes. After pasting the electrodes on the carapace, the electrodes were moistened with seawater so that they were able to detect the electrical signal on the surface of the carapace. At this stage, we checked whether the electrodes properly detected the ECG signal using a portable ECG monitor (Heart Mate IEC-1103; Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). Once the ECG signal was confirmed, the edges of the electrodes were glued onto the carapace using instant adhesive (Aron Alpha Jelly Extra; Konishi, Osaka, Japan).

Since the electrodes were electro-conductive, we insulated the outside of the electrodes with rubber sheet. Without this insulation, the voltage difference between the electrodes would disappear when the turtle was submerged owing to the electric leakage caused by seawater. First, the carapace around the electrode was wiped with acetone to remove water from the carapace. Next, the electrode was covered with a rubber sheet (11 × 8 × 0.1 cm), and the edge of the sheet was fixed by bonding with an instant adhesive. The rubber sheet was tightly attached to prevent air from entering between the sheet and the electrode. To completely insulate between the carapace and the rubber sheet, the edge of the rubber sheet was sealed with silicone resin (Bath Bond Q; Konishi), which was allowed to set for 30 min.

On the middle of the carapace, we attached an ECG recorder and accelerometer. The tags were fixed onto plastic mesh using a plastic cable tie, then glued onto the carapace using adhesive bond (Cemedine Super X; Cemedine Co., Tokyo, Japan). The two lead wires extending from the ECG recorder were connected to the lead wires of the electrodes. The connection was sealed with a heat-shrinkable tube. Then, the extra lead wires were wrapped with vinyl tape and placed along the recorders. Each wire was relatively long (ca 30 cm) so that the connection work could be done easily. The ECG recorder attachment procedure is shown in electronic supplementary material, movie S1.

After the tag attachment, the turtles were left in the water tank or lagoon, free to be submerged, swim and rest. When the turtle carapace had a keel, there was sometimes a small amount of air between the electrodes and the rubber sheet because it was difficult to attach the sheet completely. In such cases, the ECG recording showed unnatural background noise for some time (less than 1 h) after releasing the turtle into the water. Once such noise disappeared, the ECG recording became stable. The background noise observed within the first hour, may have been due to air gathering along the edge of the electrodes, between the electrode and the rubber sheet. Therefore, recordings made within 1 h of the turtle's release into the water were not used in this study. As the turtles in the tanks usually swim during the day and rest at night, we measured the heart rate for approximately 24 h to examine the condition during swimming and resting (except for one individual; table 1). For other individuals, the heart rate was measured for approximately 3 days. At the end of the experiments, the tags were removed and the data were downloaded. The turtles were not fed during the ECG recording.

Table 1.

Heart rate and recording duration of sea turtles. Values are reported as means ± s.d. The heart rate measurement periods (h) for each behaviour are indicated in parentheses. bpm, beats per minute.

| ID | species | experiment condition | mass (kg) | water temperature (°C) | recording duration (h) | proportion of time properly measured (%) | heart rate when resting underwater (bpm) | heart rate when moving underwater (bpm) | heart rate when moving at the surface (bpm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | loggerhead | tank | 35 | 22.8 ± 1.2 | 27.7 | 94.2 | 7.0 ± 1.8 (9.5) | — | 12.3 ± 3.3 (16.6) |

| 2 | loggerhead | tank | 35 | 22.7 ± 0.7 | 24.3 | 84.4 | 7.0 ± 1.5 (8.7) | — | 14.4 ± 5.0 (11.8) |

| 3 | loggerhead | tank | 26 | 23.9 ± 1.5 | 22.9 | 97.8 | 7.5 ± 2.8 (12.8) | — | 18.0 ± 5.7 (9.7) |

| 4 | loggerhead | tank | 30 | 16.7 ± 0.4 | 18.2 | 88.5 | 8.8 ± 1.7 (6.9) | — | 12.0 ± 3.2 (9.2) |

| 5 | loggerhead | tank | 47 | 24.6 ± 0.1 | 68.3 | 65.9 | 5.7 ± 0.9 (11.9) | — | 15.1 ± 4.8 (33.1) |

| 6 | black | tank | 17 | 15.1 ± 0.1 | 24.7 | 44.5 | 3.7 ± 1.3 (4.1) | — | 11.0 ± 5.7 (6.8) |

| 7 | olive ridley | lagoon | 54 | 19.6 ± 0.3 | 69.8 | 84.4 | 3.8 ± 0.9 (41.1) | 5.5 ± 3.3 (13.1) | 15.3 ± 4.7 (4.7) |

| grand mean | 35 ± 13 | 20.8 ± 3.7 | 36.6 ± 22.4 | 80.0 ± 18.6 | 6.2 ± 1.9 | 5.5 | 14.0 ± 2.4 | ||

(d) . Band-pass filter

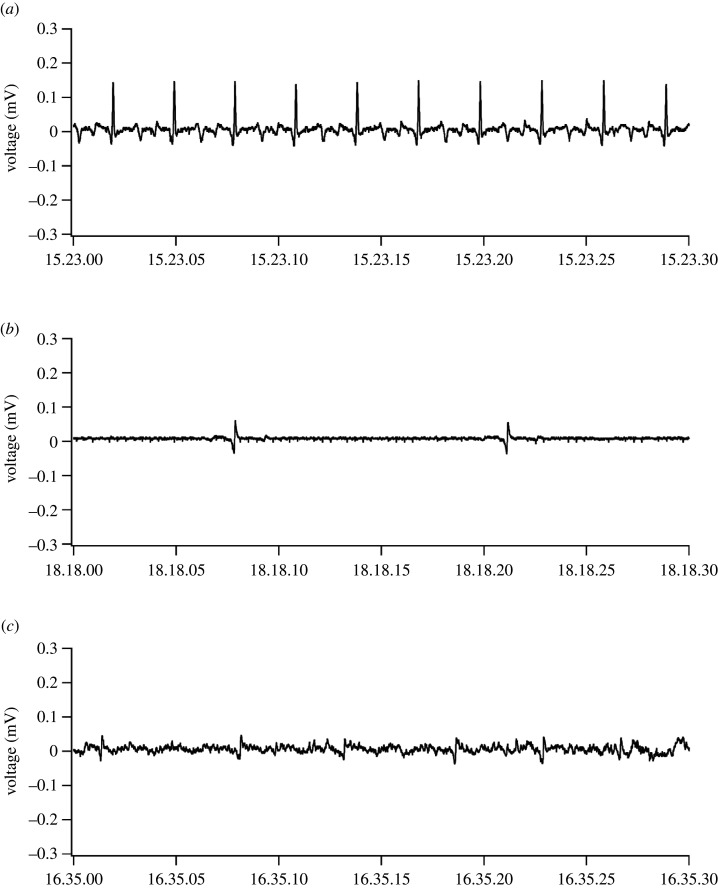

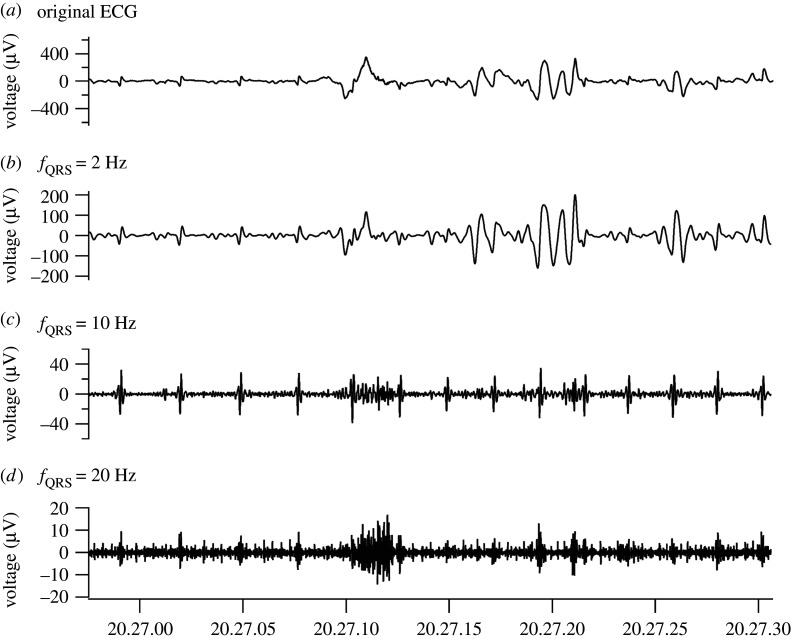

The ECG recordings contained noise, especially when the turtle was moving (figure 2). The signal of heartbeat consisted of several waves (i.e. P, Q, R, S and T waves), where the P wave represented the depolarization of the atria; the QRS complex represented the depolarization of the ventricles; and the T wave represented the repolarization of the ventricles. In terms of the frequency characteristics, the transition phase from Q to R waves showed the most drastic change in voltage, which was distinct from the other ECG waves and noise caused by body movements. Therefore, we focused on the QRS complexes to extract the heartbeat signals from the ECG recordings. We employed a finite impulse response (FIR) filter with Hanning windows [19,20], which was a band-pass filter passing only the QRS complex signal, but not the other waves and noise (figure 3). The parameters of the filter were as follows: the end of the rejected band was fQRS/3.0 Hz, the start of the pass band was fQRS/1.5 Hz, the end of the pass band was fQRS × 1.5 Hz and the start of the reject band was fQRS × 3.0 Hz. The number of coefficients for the high-pass filter was fsampling × 1.2 and that for the low-pass filter was fsampling × 0.4, where fQRS was the frequency of the steepest part of the QRS complex and fsampling was the sampling frequency of the ECG recording. The signals within the pass band were retained (gain = 1), whereas those in the reject band were omitted (gain = 0). When fQRS was 10 Hz, the signal between 6.6 and 15 Hz would be 100% retained, whereas signals less than 3.3 Hz and more than 30 Hz would be totally omitted.

Figure 2.

Original ECG of the olive ridley turtle when resting on land (a), resting underwater (b) and moving at the surface (c).

Figure 3.

The effect of the band-pass filter on the ECG when fQRS was 2, 10 and 20 Hz. (a) Original ECG. (b–d) Filtered ECG when the fQRS = 2, 10 and 20 Hz. At 2 Hz, the filtered ECG contained noise. At 20 Hz, the filtered ECG did not contain the QRS complex signal. The filtered ECG processed at fQRS = 10 Hz had a clear QRS complex signal and weak noise.

The QRS complex shapes differed slightly between individuals, possibly caused by a small difference in the position of the electrode pasted near the heart. We visually adjusted fQRS to best extract the QRS complexes in each individual (fQRS = 4–10 Hz). After filtering, the filtered signal was resampled at fQRS × 10 Hz to reduce the amount of calculations in the further steps.

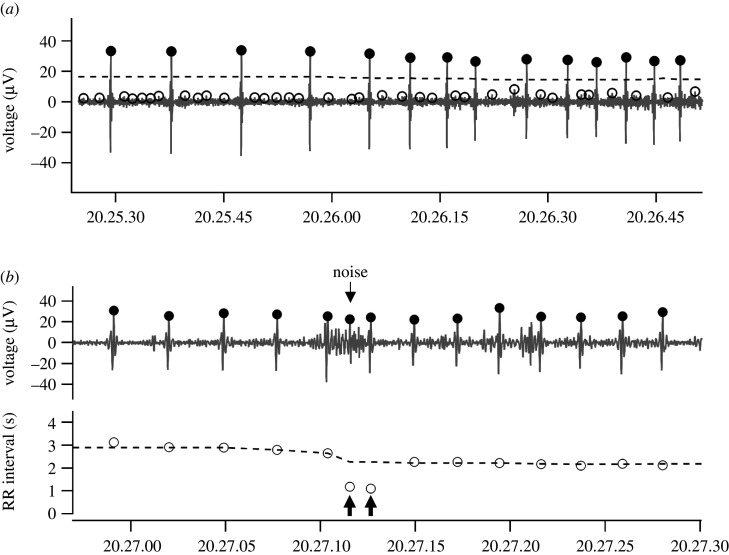

(e) . Detection of R waves

According to previous reports, we assumed that the maximum heart rate of sea turtles would be 40 beats min–1 under our experimental conditions [11,12]. For instance, if the heart rate is always less than 60 beats min–1, there will be no more than one heartbeat within a second. In other words, within the minimum heartbeat interval calculated by the maximum heart rate, there would be 0 or 1 R wave, which should be indicated by the highest voltage value in the filtered ECG. Thus, as a first step, we determined the time points at which the maximum voltage was recorded within the time periods of the assumed minimum heartbeat interval, and used these time points as R wave candidates (figure 4a). Next, to identify R waves from the candidates, we set a threshold of voltage value. By using 100 successive candidates, we calculated the 90th percentile of the candidate values, close to the maximum voltage of true R waves, but more robust against the turbulence caused by noise; we considered the half value of the 90th percentile as the threshold. When the voltage of the candidate was smaller than the threshold, the candidate was omitted.

Figure 4.

Schema of the R wave detection process. (a) R wave candidates identified on the filtered ECG (filled and open circles). Half of the 90th percentile (the threshold) is indicated by a broken line. Each filled circle indicates the next step of the analysis. (b) The filtered ECG contained a false R wave (top). Filled circles on the ECG show the points judged as R wave candidates in the previous step. A false R wave detected by the difference of RR intervals (bottom). RR intervals for each R wave are indicated by open circles. The median value of RR intervals is indicated by a broken line. The false R wave split the RR interval into two segments (arrows).

The RR interval is the time interval between two consecutive R waves. When a big noise peak is recognized as a false R wave in the middle of two R waves, one true RR interval will divided into two small RR intervals, which should be corrected (figure 4b). To identify the false small RR intervals, the value of the true RR interval should be estimated. If the value of an RR interval is close to the estimated value, then the RR interval can be determined to be the true RR interval. To do this, we took five successive RR intervals, and calculated the median value. As consecutive RR intervals would not show much difference from each other, the true RR interval should be close to the median value. When (1) the values of two successive RR intervals were less than the median value, and (2) the sum of these two RR values was 80–120% of the median value, these two RR intervals were united and the false R wave caused by noise was deleted.

(f) . Heart rate estimation

The instantaneous heart rate was calculated as the reciprocal of the RR interval. The heart rate per minute was calculated as the median value of instantaneous heart rates per minute. The median is more robust than the mean as a representative value when the data may contain some errors. We also calculated the coefficient of variation (CV: the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean) of instantaneous heart rates every minute to assess whether our method properly detected the heartbeats. When the CV was larger than 0.4, the corresponding time period was omitted and was not used in the heart rate estimation because noise could interfere with the values.

(g) . Behavioural classification

The acceleration record was used to distinguish between resting and moving. Specifically, we calculated the standard deviation of the longitudinal acceleration every minute. The turtle was regarded as resting when the standard deviation of acceleration was less than 0.2 m s–2, because this value was very small and indicated no motion. Other periods were regarded as the turtle moving. For the turtles examined in the water tank, their behaviours were classified into two categories: resting underwater and moving at the surface. As the depth of the tank was 1 m, once the turtle started to move, the turtle immediately reached the surface. Thus, we did not distinguish the behaviours of moving underwater and moving at the surface. By contrast, for the turtle examined in the lagoon, we classified the behaviours into three categories: resting underwater, moving underwater and moving at the surface. When the turtle reached a depth shallower than 1 m, we defined it as staying at the surface. There were no behavioural records corresponding to resting at the surface in the experiment.

(h) . Data analysis

ECG, depth and acceleration records were analysed using IGOR Pro v.7.08 (Wavemetrics, Portland, OR, USA) with the Ethographer program package [21]. For the signal processing part of the algorithm, we have developed a new program package, ECGtoHR, which runs on IGOR Pro. ECGtoHR removes noise from the ECG with a band-pass filter, detects R waves, and estimates heart rate by inserting two parameters, fQRS and maximum heart rate, as described above. This program package provides a graphical user interface, and thus is easy to use (electronic supplementary material, movie S2). The program can be downloaded via the internet and is free of charge for academic use (https://sites.google.com/site/kqsakamoto/ecgtohr).

We summarized the heart rate per minute to estimate the represented value of the heart rate in each behavioural mode. The difference in the heart rate in each behavioural mode was examined using Student's t-test. The Bonferroni correction was employed to compare the three groups. The values are expressed as means ± s.d.

3. Results

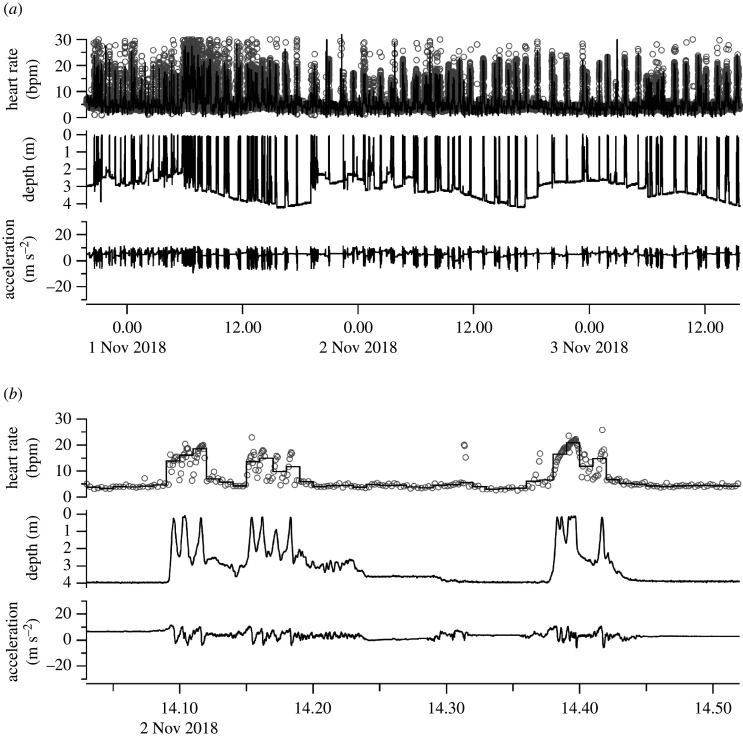

When we attached the electrodes to turtles on land, we noticed the differences between species. Clear R waves were observed in the loggerhead (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), black (electronic supplementary material, figure S2) and olive ridley turtles (figure 2); however, only slight R waves were observed in the green turtle (electronic supplementary material, figure S3), and R waves were not detected at all in the hawksbill turtle (electronic supplementary material, figure S4). After the tag attachment, we released the turtles into the water. Once the turtle entered the water, the R wave amplitude of all turtles became weakened. Especially in green turtles, the R waves disappeared. Therefore, we measured the ECG signal and estimated the heart rate of the loggerhead, black and olive ridley turtles (table 1, figure 5 and electronic supplementary material, datasets). During 18.2–69.8 h of ECG recording for each individual, the heart rate was successfully determined 80.0 ± 18.6% of the time (11.0–58.9 h). The heart rate when resting underwater was 6.2 ± 1.9 beats min–1, whereas the heart rate when moving at the surface was 14.0 ± 2.4 beats min–1 (paired t-test, p < 0.001). In the case of the olive ridley turtle, the heart rate was measured when the turtle stayed in the lagoon. The turtle sometimes moved underwater for more than 10 min. The heart rate when the turtle was moving underwater was 5.5 ± 3.3 beats min–1, which was 45% higher than when resting on the bottom in the lagoon (3.8 ± 0.9 beats min–1; unpaired t-test with Bonferroni correction, p < 0.001), but much lower than when moving at the surface and breathing (15.3 ± 4.7 beats min–1; p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Heart rate, depth and longitudinal acceleration traces of the olive ridley turtle measured in the lagoon. (a) Entire record. (b) Enlarged image of the recording. Instantaneous heart rates are indicated by open circles and the median heart rates per minute are indicated by a solid line. The maximum depth was affected by the horizontal movement of the turtle and diurnal rhythm of the tide. Longitudinal acceleration indicates the time when the turtle was moving. bpm, beats per minute.

4. Discussion

It is unclear what caused the species differences in the ECG signals detected on the carapace (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, figures S1–S4). The carapace is covered by scutes, which are made of keratin [22]. We noticed that the detection of the ECG signal was correlated with the scute texture of each turtle species. The scutes of the hawksbill and green turtles were composed of dense keratin, and looked like nail tissue; they did not transmit electricity. By contrast, those of loggerhead and olive ridley turtles formed relatively sparse structures. When we attached the electrodes onto the carapace, we observed that the carapace of these turtles absorbed a small amount of seawater, which might transmit the ECG signal through the carapace. The black turtle showed characteristics intermediate between those of green and loggerhead turtles, possibly resulting in a smaller amplitude of the R wave and lower proportion of time in which the heart rate was successfully identified (44.5%) than that in loggerhead and olive ridley turtles (65.9–97.8%; electronic supplementary material, figure S5). Among the studies reporting the sea turtle ECG, only one showed the ECG amplitude. Compared with the study measuring the ECG signal from electrodes placed inside the body of green turtles [14], the amplitude of R waves in this study was ca 10 times smaller, even in loggerhead and olive ridley turtles. Such a small signal amplitude may be due to the interference effect of the carapace.

It is difficult to draw any conclusion regarding the effect of species difference, mass and water temperature on heart rate from the results of this study. In addition, these conditions were variable among previous reports measuring the heart rate of sea turtles. Therefore, we cannot draw any conclusions from the simple comparison of the heart rates in these studies. Nevertheless, the heart rates recorded in this study were relatively lower than previous reports measuring the heart rates of sea turtles [10–14,23,24]. The lower stress from this non-invasive technique could account for any differences that mass and temperature do explain.

The other advantage of our newly developed method is a signal processing algorithm that enables us to pick up small heartbeat signals from noisy ECG signals. While the heart rate of free-ranging animals has been extensively measured, the available signal processing programs are designed only for human ECGs. Thus, past studies have visually examined or used a custom-written program to identify R waves and estimate the heart rate [10,12,25]. ECGs can be visually examined in detail, though detecting the heartbeat is sometimes difficult and time consuming in noisy ECGs (figure 3). Custom-written programs are designed only for the study species and may not be suitable for other species; however, our program package for signal processing was designed for a wide range of animals, including cetaceans [26] and is openly available to the public.

5. Conclusion

While measuring the physiology of free-ranging animals provides important insights into how animals live in their natural environments, methodological difficulties have sometimes impeded further progress. Unlike conventional heart rate measurement methods for free-ranging sea turtles, this technique does not leave any part of the device inside the body, even in the case of the tag detaching naturally. Thus, this method is applicable to automatic tag-releasing systems and greatly expands the scope of possible research. Moreover, our measurement approach is non-invasive and therefore has many positive aspects, such as not requiring further research permits, being better adapted to the well-being of the animal, best practice for use in research of protected species. Therefore, our approach offers a new opportunity to study the physiology of free-ranging animals.

Acknowledgements

We thank: Tomoko Narazaki for valuable input in the design of the experiment; Masaya Shinmura and the staff of Suma Aqualife Park Kobe for their assistance in the field; Ken Yoda and Masaki Shirai for providing ECG recorders. We are also grateful to the volunteers from the Fisheries Cooperative Association of Funakoshi Bay, Kamaishi-Tobu, Omoe, Sasaki, Shin-Otsuchi and Yamaichi for providing the incidentally caught, wild sea turtles used in this study.

Ethics

We carefully conducted this study according to the principles of 3Rs (reduction, replacement and refinement) in this study. Although it was inevitable to use sea turtles to achieve the purpose of the study, only the minimum number of individuals were used to develop and validate our heart rate measurements system for several sea turtle species. In addition, we performed the most non-invasive study to measure the heart rate of sea turtles compared with previous studies. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute of the University of Tokyo (permission number P18-18).

Data accessibility

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

K.Q.S. conceived the study; K.Q.S. and K.S. designed the experiment; K.Q.S., M.M., C.K., T.F. and T.I. conducted the experiment; K.Q.S. analysed the data and wrote the first draft. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interest.

Funding

This work was supported by Tohoku Ecosystem-Associated Marine Science (TEAMS) funding to K.Q.S and K.S., and JSPS KAKENHI grant no. 17H00776 to K.S.

References

- 1.Butler PJ, Jones DR. 1997. Physiology of diving of birds and mammals. Physiol. Rev. 77, 837-899. ( 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.837) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler PJ, Green JA, Boyd IL, Speakman JR. 2004. Measuring metabolic rate in the field: the pros and cons of the doubly labelled water and heart rate methods. Funct. Ecol. 18, 168-183. ( 10.1111/j.0269-8463.2004.00821.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green. 2011. The heart rate method for estimating metabolic rate: review and recommendations. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 158, 287-304. ( 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.09.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponganis PJ. 2015. Diving physiology of marine mammals and seabirds. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldbogen JA, et al. 2019. Extreme bradycardia and tachycardia in the world's largest animal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25 329-25 332. ( 10.1073/pnas.1914273116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochscheid S. 2014. Why we mind sea turtles' underwater business: a review on the study of diving behavior. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 450, 118-136. ( 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.10.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heatwole H, Seymour RS, Webster MED. 1979. Heart rate of sea snakes diving in the sea. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 62, 453-456. ( 10.1016/0300-9629(79)90085-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith EN, Allison RD, Crowder WE. 1974. Bradycardia in free ranging American alligator. Copeia 1974, 770-772. ( 10.2307/1442691) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seebacher F, Franklin CE, Reed M. 2005. Diving behaviour of a reptile (Crocodylus johnstoni) in the wild: interactions with heart rate and body temperature. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 78, 1-8. ( 10.1086/425192) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Southwood AL, Andrews RD, Lutcavage ME, Paladino FV, West NH, George RH, Jones DR. 1999. Heart rates and diving behavior of leatherback sea turtles in the eastern Pacific Ocean. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 1115-1125. ( 10.1242/jeb.202.9.1115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochscheid S, Bentivegna F, Speakman JR. 2002. Regional blood flow in sea turtles: implications for heat exchange in an aquatic ectotherm. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 75, 66-76. ( 10.1086/339050) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams CL, Sato K, Ponganis PJ. 2019. Activity, not submergence, explains diving heart rates of captive loggerhead sea turtles. J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb200824. ( 10.1242/jeb.200824) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Southwood AL, Darveau CA, Jones DR. 2003. Metabolic and cardiovascular adjustments of juvenile green turtles to seasonal changes in temperature and photoperiod. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 4521-4531. ( 10.1242/jeb.00689) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuyama J, Shiozawa M, Shiode D. 2020. Heart rate and cardiac response to exercise during voluntary dives in captive sea turtles (Cheloniidae). Biol. Open 9, bio049247. ( 10.1242/bio.049247) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe Y, Baranov EA, Sato K, Naito Y, Miyazaki N. 2004. Foraging-tactics of Baikal seals differ between day and night. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 279, 283-289. ( 10.3354/meps279283) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narazaki T, Sato K, Abernathy KJ, Marshall GJ, Miyazaki N. 2009. Sea turtles compensate deflection of heading at the sea surface during directional travel. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 4019-4026. ( 10.1242/jeb.034637) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narazaki T, Sato K, Miyazaki N. 2015. Summer migration to temperate foraging habitats and active winter diving of juvenile loggerhead turtles Caretta caretta in the western North Pacific. Mar. Biol. 162, 1251-1263. ( 10.1007/s00227-015-2666-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuoka T, Narazaki T, Sato K. 2015. Summer-restricted migration of green turtles Chelonia mydas to a temperate habitat of the northwest Pacific Ocean. Endang. Species Res. 28, 1-10. ( 10.3354/esr00671) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris FJ. 1978. On the use of windows for harmonic analysis with the discrete Fourier Transform. Proc. IEEE. 66, 51-83. ( 10.1109/PROC.1978.10837) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zahradnik P, Vlcek M. 2004. Fast analytical design algorithms for FIR notch filters. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 51, 608-623. ( 10.1109/TCSI.2003.822404) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakamoto KQ, Sato K, Ishizuka M, Watanuki Y, Takahashi A, Daunt F, Wanless S. 2009. Can ethograms be automatically generated using body acceleration data from free-ranging birds? PLoS ONE 4, e5379. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0005379) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wyneken J. 2001. The anatomy of sea turtles. NOAA Tech. Memo., NMFS-SEFSC-470. Miami, FL: US Department of Commerce.

- 23.Lanteri A, Lloze R, Roussel H. 1980. Diving and heart beat compounds in the marine turtle Caretta caretta (LINNÉ) (Reptilia, Testudines). Amphibia-Reptilia 1, 337-341. ( 10.1163/156853881X00429) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Southwood AL, Andrews RD, Paladino FV, Jones DR. 2005. Effects of diving and swimming behavior on body temperatures of Pacific leatherback turtles in tropical seas. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 78, 285-297. ( 10.1086/427048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakamoto KQ, Takahashi A, Iwata T, Yamamoto T, Yamamoto M, Trathan PN. 2013. Heart rate and estimated energy expenditure of flapping and gliding in black-browed albatrosses. J. Exp. Biol. 216, 3175-3182. ( 10.1242/jeb.079905) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aoki K, Watanabe Y, Inamori D, Funasaka N, Sakamoto KQ. 2021. Towards non-invasive heart rate monitoring of free-ranging cetaceans: a unipolar suction cup tag measured the heart rate of trained Risso's dolphins. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200225. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0225) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.