Abstract

The poverty-as-a-vaccine hypothesis came to light following the wide circulation of the controversial British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) World Service post on the internet and social media. It was a theoretical response to what this paper has termed as “the African COVID-19 paradox” or what some have characterised as the “African COVID-19 anomaly” whose thesis is though Africa is the poorest continent in the world, yet it has some of the lowest COVID-19 infection and mortality rates globally. This paradoxical profile apparently contradicts earlier and grim projections by several international bodies on the fate of Africa in this global health crisis. Given this background, we specifically tested the validity of the hypothesis from a geographic perspective within the spatial framework of Africa. Data came from secondary sources. Evidence truly points out a significant negative relationship between COVID-19 and poverty in Africa and thus statistically supports the poverty-as-a-vaccine hypothesis. However, this does not confirm that poverty confers immunity against COVID-19 but it implicitly shows there are complex factors responsible for the anomaly. The main conclusion of the paper is that poverty has no protective immunity against COVID-19 in Africa and is therefore not tenable.

Keywords: African COVID-19 paradox, Poverty, Air traffic, Africa, COVID-19

Introduction

COVID-19 otherwise known as coronavirus is a relatively new and highly transmissible viral infection caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). This causal agent is the latest addition to the large family of coronaviruses (of which Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome [SARS] are members) (World Health Organisation 2020b). The virus was discovered at a seafood market at Wuhan, Hubei Province of China on the 31st of December, 2019 (Africa Centre for Disease Control 2020; Casscella et al. 2020). Three months after, the World Health Organisation declared the novel infection a pandemic on the 11 March 2020 (World Health Organisation 2020) following its swift spread across the world. This virus no doubt has greatly altered the course of human history. Within a very short time, the world has rapidly shifted from the socially proximate community with which we were once deeply familiar to a socially distant one. Its impacts are presently more challenging for humanity to bear. Human lives, bonds and livelihoods across the world have been disrupted at varying degrees of severity. Thus, this global health emergency continuously compels us to reconsider and reorganize all facets of human existence.

Global figures as at August 4, 2020 show there were 18,142,718 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and 691,013 deaths (World Health Organisation 2020). This obviously has placed a huge strain on the healthcare systems and demography across the globe (Iyanda et al 2020). Of all the continents in the world, Africa, with 16.72% of the world’s population, is one of the least affected with 4.5% of the global burden whereas the highly developed parts of the world such as Europe and North America bear a significant burden of the pandemic. This is rather incomprehensible to many observers for a number of reasons. Before this African pandemic puzzle is further elaborated, it is appropriate to situate this mystery within context. Prior to the virus’s arrival to Africa which came much later than the rest of the world, there were some speculations that Africa’s comparatively warm climate would be an absorbing barrier to the spatial diffusion of COVID-19 (see Martinex-Alvarez et al. 2020; Olapegba et al. 2020). This meant the virus would not survive the African tropical climate. On the contrary, it did. The first COVID-19 case on the continent was in Egypt on 14 February, 2020. Since then, the virus had spread rapidly—initially through what Muller-Mahn and Kioko (2021) elegantly described as “the internationally mobile elites”—to the rest of the continent where most of the cases were at first limited to capital cities or major urban centres and later spread to surrounding states or provinces (WHO, 2020). For instance, a large percentage of Nigeria’s COVID-19 infection cases are in Africa’s largest city, Lagos (Olusola et al 2020; Osayomi 2020; Okafor and Osayomi 2021) because it is a major hub of international travel and the most populous city in Nigeria (Okafor and Osayomi 2021).

In the meantime, The U.N. Economic Commission for Africa in April 2020 had projected 1.2 billion infection cases and 3.3 million deaths to occur in the continent if nothing was done to contain the spread of the virus. The raison d’etre for the projection was the current underdevelopment status of Africa which is sadly characterized by high infectious disease burdens/highly immunocompromised population and growing non-communicable disease prevalence such as HIV, obesity, diabetes, tuberculosis, chronic respiratory diseases, among others which have been found to be risk factors of COVID-19 (Adepoju 2020; CDC 2020; Goufo et al. 2020), inadequate health care facilities, shortage of medical personnel and equipment, low budgetary allocations to health, absence or poorly developed and implemented social welfare programmes (Rosenthal et al 2020; Oppong 2020; Nuwagira and Muzoora 2020; Martinez-Alvarez et al 2020; Ataguba 2020; Lone and Ahmad 2020; Lawal 2021; Maeda and Nkengasong 2021). The fragile healthcare systems was initially expected to leave Africa absolutely unprepared for the imminent outbreak as at then, as El-Sadr and Justman (2020) also noted the stark disparities in the distribution of critical medical equipment such as ventilators among African countries; and the poor quality of healthcare and social infrastructure. Lastly, Ataguba (2020) in his own assessment created a very grim scenario in which the continent would suffer multiple tragedies because of its large dependence on the regular foreign aid flow from the developed countries which he envisaged might suddenly stop so as to meet urgent needs arising from the COVID-19 pandemic in donor countries. In his estimations, Africa would be left in a financially helpless situation and multiple challenges to contend with.

Given Africa’s current development status, there were frantic calls that the Africa Centre for Disease Control (CDC) and the WHO should be fully prepared for the pandemic’s devastating impacts in Africa which were projected to be more severe than anywhere else in the world (Nuwagira and Muzoora 2020). It was in fact predicted that given the endemic poverty, economic hardships and overstretched social amenities, Africa could have 30 million poor people in the end (BBC Africa 2020). On the contrary, Africa recorded lower infection and fatality rates than the developed world (Iwuoha et al 2020). In the words of El-Sadr and Justman (2020, p. e11:1), Africa “has been largely spared the impact that has thrown China, the US and Europe into chaos”.

Ever since, Africa’s shockingly low COVID-19 morbidity and mortality or better framed as the ‘African COVID-19 paradox’ has been the subject of growing curiosity in both the academia and media circles. In this instance, a media report from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC World Service) expressed surprise at the fact that “… infection and death rates in many African countries have turned out to be much lower than initially feared …” and went further to postulate that Africa’s endemic poverty might be a vaccine against COVID-19 (BBC World 2020). It, therefore, followed that the inability of some or many African households to meet their daily necessities of life such as food, shelter, health and clothing somewhat conferred natural immunity against the highly contagious disease. This conjecture of course received outrage, condemnation and criticism on social media.

Though the poverty-as-a-vaccine hypothesis, as it was later called, was largely perceived, in the eye of the public, to be severely harsh and a dehumanising assessment of Africa and its people, this controversial presumption clearly stems from the region’s gloomy socio-economic profile. Africa accounts for the largest number of poor people in the world—more than 70 percent of the world’s poorest (Hamel et al., 2019). No doubt, poverty has significant effects on health outcomes such as malaria, neglected tropical diseases and so on. According to the World Health Organisation (2004), most diseases in Africa are associated with poverty, poor nutrition, indoor air pollution and lack of access to proper sanitation and health education. Therefore, the scrutiny of this African COVID-19 paradox forms the basis of this study. The paper then set out to analyse the geographical heterogeneity of COVID-19 pandemic in Africa with a view to empirically verifying the validity of the hypothesis among other explanatory factors. This might provide fresh insights on the nature of the pandemic in Africa and probably raise new avenues of enquiry. The specific objectives of the study are as follows: (a) analyse the geographical distribution of COVID-19 in Africa with a view to determining the degree of spatial clustering (b) determine the relative significance of poverty in the explanation of the observed spatial pattern. The rest of the discussion proceeds in the following manner. The “Data and Methods” section follows this introduction. The second section contains the results. The third section is the discussion of the study’s findings. The paper ends with conclusions.

Data and Methods

This paper largely relied on secondary data from the Africa Centre for Disease Control (Africa CDC), Population Reference Bureau (PRB), the African Development Bank (AfDB), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP). Retrospective data on the number of confirmed COVID-19 morbidity and mortality cases in all the African countries as at August 3, 2020 (09.00 AM East African Time) were extracted from the Africa CDC while the explanatory variables on Human Development Index (HDI), percent population using basic sanitation facilities, percent fine particulate matter, percentage of the population 65 years of age and above, life expectancy, HIV/AIDS, percent population with piped water in urban areas, percent population with limited and shared sanitation facilities, percent population who practice open defecation, percent of country’s population that is urban, national population density, Human Poverty Index (HPI), poverty incidence, diabetes prevalence and funding towards Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) were obtained from PRB, AFDB, UNDP, IDF and JMP.

The following statistical techniques Global Moran’s I, Anselin, local Moran, Pearson correlation and multivariate regression were applied in the study. We examined the pattern of spread of COVID 19 in Africa using the Global Moran ‘s I and Anselin local Moran. The Global Moran’s I tests for the presence and strength of spatial autocorrelation in geographic data. It seeks to know if values of a given object correlate in geographic space. The I index varies between -1 (negative spatial autocorrelation) and + 1 (positive spatial autocorrelation). If it is close to zero, zero spatial autocorrelation is present. A positive spatial autocorrelation in this instance would mean countries with similar COVID-19 rates are spatially clustered while a negative autocorrelation suggests countries are surrounded by neighbours with contrasting values. Anselin Local Moran identified the location of COVID-19 hotspots and coldspots in Africa. Any of the five categories of disease clusters was anticipated in the study: High–High (HH)—above-average concentration of COVID-19; Low–Low (LL)—below-average concentration of COVID-19; Low–High (LH)/High–Low (HL) refers to the outliers in geographic space, and not significant means no cluster. On the other hand, Pearson correlation was employed to examine the nature and degree of association between COVID-19 and the explanatory variables. The multivariate linear regression quantified the joint and individual contributions of important explanatory variables on the geographical distribution of COVID-19 in Africa. The dependent variables were COVID-19 morbidity rate and COVID-19 mortality rate. They were arrived at by dividing the number of confirmed cases/deaths by the population of a given country multiplied by 100,000. Choropleth maps and spatial analysis were done with ArcGIS 10.4 version and GeoDa while statistical data analysis was performed with SPSS version 20.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Summary statistics are presented in Table 1. Considerable variation based on the standard deviation, was seen in WASH funding, population density, COVID-19 morbidity rate and population with access to sanitation facilities.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Socio-environmental variable | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of population 65 years of age and above | 3.84 | 1.989 |

| Percentage of population with access to basic sanitation facilities | 37.62 | 23.901 |

| Percent fine particulate matter | 34.27 | 17.728 |

| Percentage of population that is urban | 46.97 | 20.018 |

| Human Poverty Index (HPI) | 32.39 | 12.506 |

| Human Development Index (HDI) | 0.66 | 0.478 |

| COVID-19 morbidity | 107.9488 | 197.32266 |

| COVID-19 mortality | 1.6565 | 2.82917 |

| Poverty incidence (%) | 34.56 | 22.994 |

| Population density | 982.57 | 1110.338 |

|

WASH funding Life expectancy |

65,403,846.15 62.4130 |

66,998,759.021 5.11892 |

| Open defecation | 6.9184 | 9.13518 |

| Piped water in urban areas | 72.0208 | 23.40348 |

| Limited shared sanitation facilities | 26.8776 | 15.62268 |

|

Diabetes prevalence HIV/AIDS |

4.79 10.5053 |

3.723 7.33049 |

Geographical Distribution of COVID-19

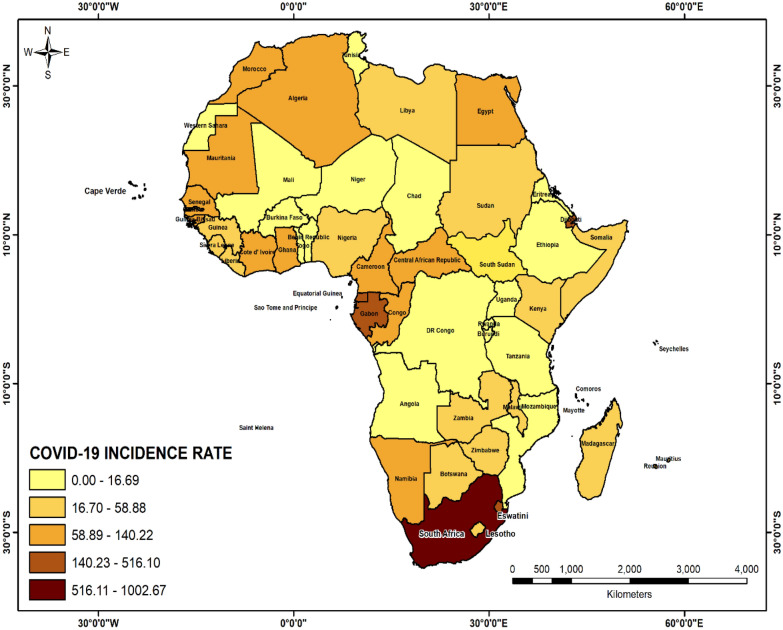

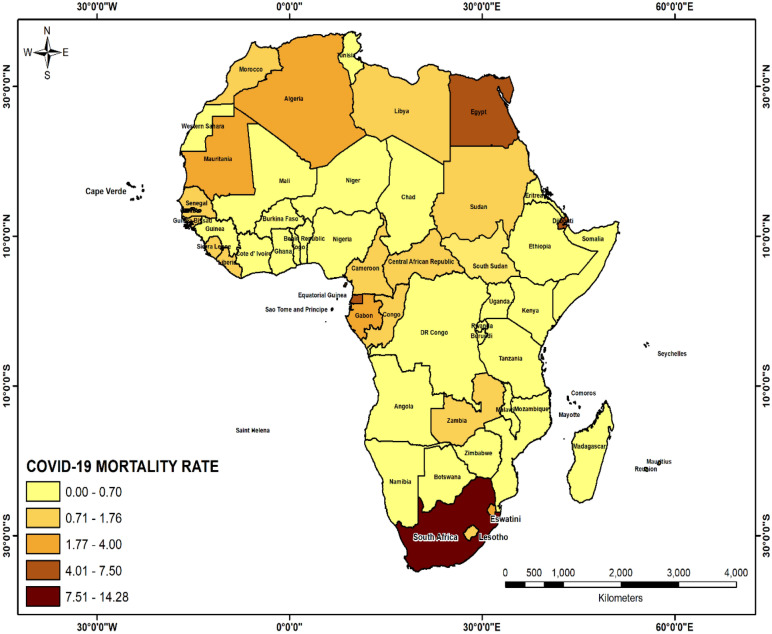

As at August 3, 2020 09.00AM Eastern African Time, there were 957,702 confirmed cases and 20,292 deaths associated with COVID-19 in Africa. Five countries with the highest COVID-19 incidence rates were South Africa (872.84/100,000), Djibouti (516/100,000), Sao Tome (437/100,000), Cape Verde (424.50/100,000), and Equatorial Guinea (344.36/100,000) (Fig. 1) while South Africa (14.28/100,000) tops the mortality list followed by Sao Tome and Principe (7.50/100,000), Equatorial Guinea (5.93/100,000), Djibouti (5.9/100,000) and Egypt (4.91/100,000) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of COVID-19 morbidity in Africa (August 3, 2020 9.00AM EAT)

Fig. 2.

Geographical distribution of COVID-19 mortality in Africa (August 3, 2020 9. EAT)

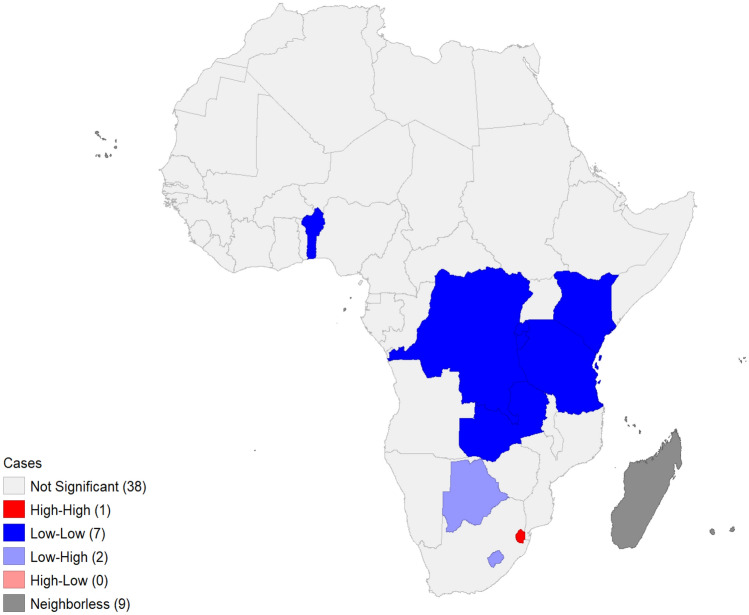

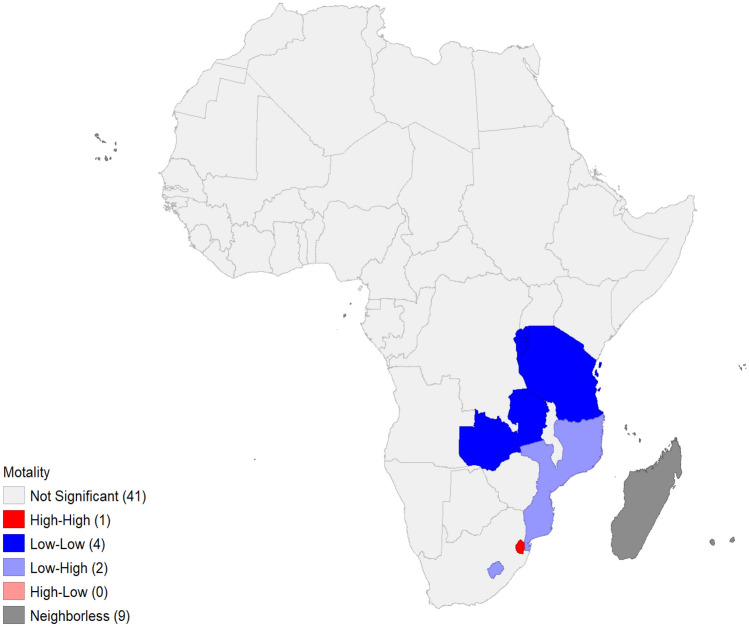

Spatial Clustering and Hotspot Analysis

There was no evidence of spatial autocorrelation in morbidity (I = 0.0551; z = 1.0144; p = 0.148) and mortality in Africa (I = 0.0080; z = 0.4292; p = 0.285). COVID-19 clusters of different categories were found in Africa (Figs. 3, 4). Incidentally, Eswatini was the only HH cluster with respect to morbidity and mortality. It means that the country is bordered by countries with equally or similarly high incidence and mortality rates. With regard to morbidity, Botswana and Lesotho were labelled LH because they had comparatively low incidence rates. Lesotho and Mozambique were LH clusters of COVID-19 mortality (Tables 2, 3).

Fig. 3.

COVID-19 morbidity hotspots

Fig. 4.

COVID-19 mortality hotspots

Table 2.

COVID-19 morbidity clusters

| Country | I | p | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| DR Congo | 0.166232 | 0.045 | LL |

|

Benin Zambia Burundi Rwanda |

0.203733 0.114958 0.244631 0.218277 |

0.019 0.038 0.018 0.003 |

LL LL LL LL |

| Tanzania | 0.224333 | 0.006 | LL |

| Kenya | 0.118099 | 0.031 | LL |

| Botswana | − 0.349292 | 0.044 | LH |

| Eswatini | 2.547961 | 0.043 | HH |

| Lesotho | − 1.611073 | 0.001 | LH |

Table 3.

COVID-19 mortality clusters

| Country | I | p | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zambia | 0.088453 | 0.002 | LL |

| Eswatini | 2.539900 | 0.045 | HH |

| Tanzania | 0.040000 | 0.007 | LL |

| Burundi | 0.313656 | 0.006 | LL |

| Rwanda | 0.314621 | 0.003 | LL |

| Lesotho | − 1.12530 | 0.0010 | LH |

| Mozambique | − 0.473867 | 0.048 | LH |

The Relationship Between COVID-19 and Poverty

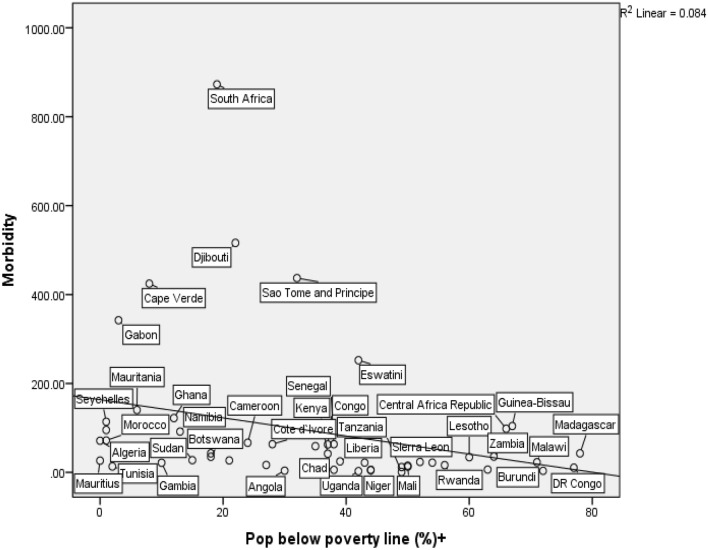

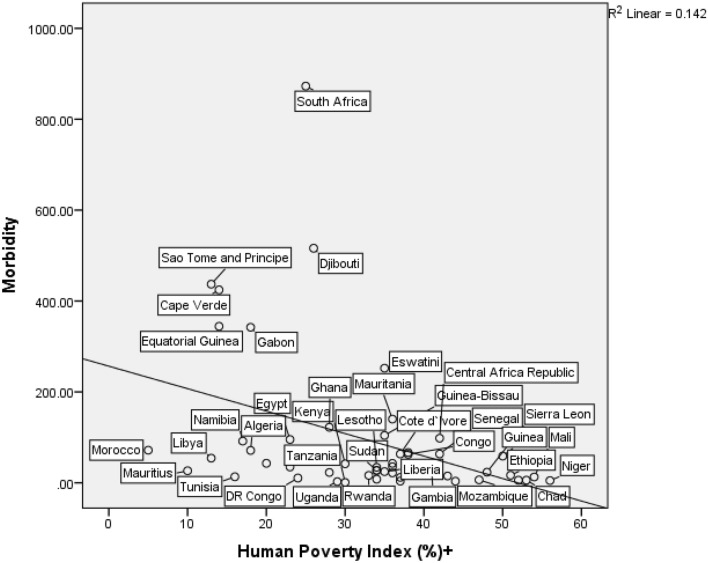

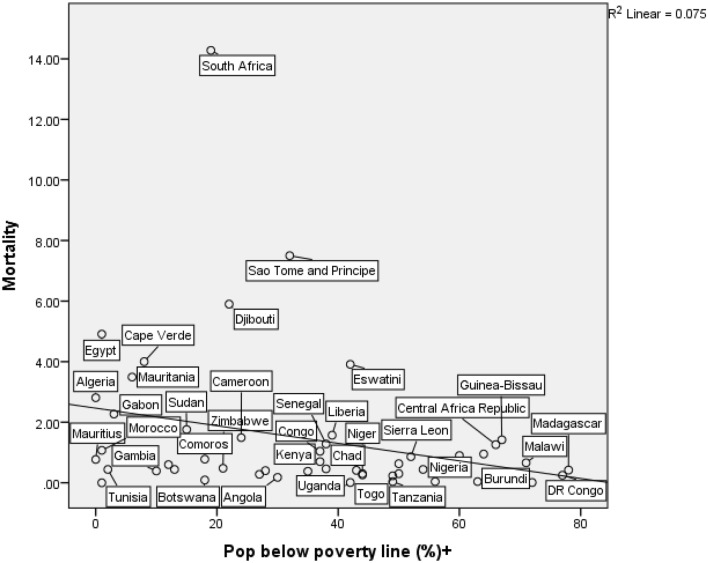

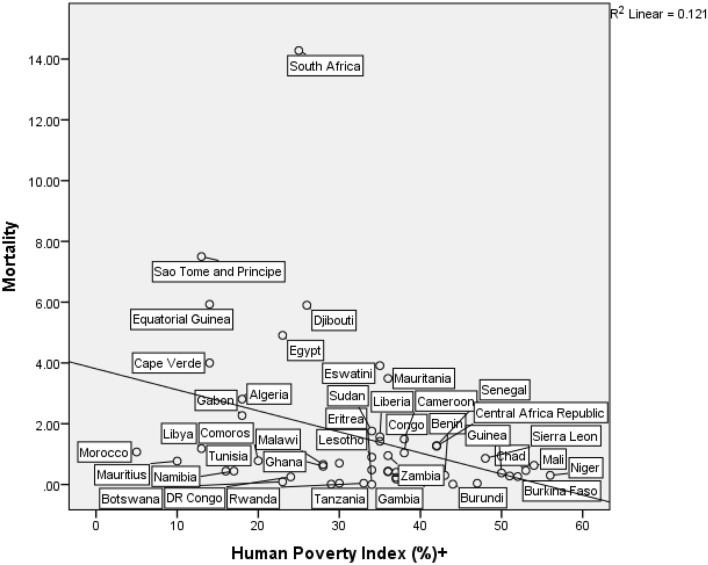

Based on the results, there are noticeable geographical variations in COVID-19 across the continent. What is yet to be known is if African countries with high levels of poverty truly have low COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates. Four scatter diagrams (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8) were produced to depict the nature and strength of the relationship between COVID-19 and two poverty indicators: poverty incidence and Human Poverty Index (HPI). They offer useful insights on the African COVID-19 paradox. The first diagram (Fig. 5) show that Djibouti, Caper Verde, Gabon and Sao Tome and Principe have fairly high COVID-19 morbidity rates but with fairly low poverty levels. In addition, Eswatini, Central African Republic (CAR), Guniea Bissau, Zambia, Malawi and Madagascar just to mention a few have the highest poverty levels but COVID-19 morbidity is very low. Like Fig. 5, Fig. 6 shows similar patterns but more countries such as Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Niger, Mali, Guinea, and Mauritania have high poverty levels but low morbidity rates. With respect to mortality, Fig. 7 reveals that Egypt, Cape Verde, Mauritania, Algeria have moderately high mortality rates but very low poverty levels. Furthermore, Sao Tome and Principe and Djibouti have higher mortality rates but moderately low poverty levels. CAR, Guinea, Malawi and Madagascar have high poverty levels but low morbidity rates. Like Fig. 7, Fig. 8 present very similar patterns. Two trends are common to all these diagrams. First, South Africa was an outlier in all the diagrams. Second, there is a negative association between COVID-19 and poverty. The coefficient of determination (R2) values for Figs. 5 (R2 = 0.084), 6 (R2 = 0.142), 7 (R2 = 0.075), 8 (R2 = 0.121) indicate the proportion of COVID-19 explained by poverty is very low and therefore are weak explanatory models.

Fig. 5.

The relationship between COVID-19 and poverty incidence

Fig. 6.

Relationship between COVID-19 morbidity and Human Poverty Index

Fig. 7.

Relationship between COVID-19 mortality and poverty incidence

Fig. 8.

Relationship between COVID-19 mortality and Human Poverty Index

Associations with Country Level Characteristics

The results of bivariate correlations are set out in Table 4. On one hand, COVID-19 morbidity is associated with an increase in access to basic sanitation facilities, percent urban population, air traffic and piped water in urban Africa and at the same time, inversely associated with HPI and poverty incidence. On the other hand, access to sanitation facilities, percent urban population, air traffic, diabetes prevalence, piped water is directly associated with COVID-19 mortality, which suggests that an increase in the aforementioned variables predicts an increase in COVID-19 mortality. However, HPI and unimproved sanitation are negatively related with COVID-19 mortality. This indicates that a decline in poverty and access to unimproved sanitation facilities increases COVID-19 mortality rate. Drawing from the evidence presented and with particular reference to the hypothesis, the bivariate correlational analysis confirmed a statistically significant negative association between COVID-19 infection and mortality and the poverty indices. On the premise of this evidence, the poverty-as-a-vaccine hypothesis is somewhat validated.

Table 4.

Bivariate Correlations

| Country level characteristics | Morbidity | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent population with sanitation facilities | 0.412 | 0.479 | |

| Urban population | 0.410 | 0.324 | |

| HPI | − 0.377 | − 0.348 | |

| Poverty incidence | − 0.290 | – | |

| Air traffic | 0.595 | 0.702 | |

| Basic sanitation facilities | 0.316 | 0.388 | |

| Percent urban population with piped water | 0.332 | 0.293 | |

| Population below the poverty line | − 0.290 | – | |

| Unimproved sanitation | – | − 0.295 | |

All significant variables at p < 0.05

Two multivariable stepwise regression model were estimated to determine the individual and collective impacts of the explanatory variables on COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Air traffic was the only significant explanatory variable that emerged in the two models (see Table 5). In other words, poverty, in terms of relative importance, is not the most significant explanatory factor in the distribution of COVID-19.

Table 5.

Results of multivariable regression model

| Dependent variable | Explanatory variable | Beta coefficient | R2 | F | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morbidity | 0.642 | 0.412 | 19.592 | 0.000 | |

| Air traffic | |||||

| Mortality | 0.755 | 0.642 | 37.232 | 0.000 |

Discussion

As previously mentioned, the principal objective of this paper was to examine the extent to which the geographical distribution of COVID-19 mirrors the variations in poverty incidence among other factors within the purview of the poverty-as-a-vaccine-hypothesis. First, spatial variations in the distribution of the COVID-19 morbidity and morbidity in Africa are clear. South Africa had the highest COVID-19 infection and mortality rates in Africa. There are four potential explanations for this high prevalence. The first explanation is linked to the large and densely populated urban settlements in the country (Arashi et al 2020). South Africa has an urban population of 66 percent which is the highest in southern Africa (Population Reference Bureau, 2019). As it is well known, urbanisation facilitates the transmission of infectious diseases. With respect to COVID-19, its transmission heavily relies on physical proximity.

The second explanation is associated with the pre-existing and widespread non-communicable diseases epidemic which has greatly increased the risk of exposure to COVID-19 among South Africans (Arashi et al 2020). The third explanation is the country’s “early and comprehensive program for widespread testing” (Rosenthal et al. 2020:1145) which largely accounted for the very large number of reported cases and eventually the successful management of COVID-19. South Africa has tested over 4 million people, making it the highest on the continent (Worldometer, 2020). The last explanation is the arrival of the winter season in southern Africa which favours the effective spread of viruses including COVID-19 (Lone and Ahmad 2020). The presence of a hotspot in Eswatini could be a spill over effect due to its geographic proximity to South Africa.

The cold spots in Central and East Africa could be attributed to the low testing rates in the region as at the time of the study. As earlier stated, testing rates on the continent are generally very low and this could present a false impression of COVID-19 prevalence (Soy, 2020). The lack or low level of testing makes it difficult to determine the true nature, scale and magnitude of the outbreak on the continent (Kazeem 2020). This might explain the relatively low numbers of infections and fatalities in many East African countries. An example is Tanzania which stopped testing for COVID-19 because the country’s president John Magufuli, before his demise, was “… certain that many Tanzanians believe, that the corona disease has been eliminated by God” (BBC News Africa 2020). There was no information, at the time of writing, on the total number of COVID-19 tests conducted in the Democratic Republic of Congo at the (Worldometer, 2020). At the time of writing, only 2,852 tests per 1 million population in Burundi had been conducted so far while less than 9,000 tests per 1 million population have been carried out in Zambia (Worldometer, 2020).

Some results of the bivariate correlations were counterintuitive. For instance, the relationship between access to basic sanitation facilities and COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, contrary to theoretical expectations, was positive, meaning access to basic sanitation increases COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. One would definitely anticipate that increased access to basic sanitation facilities, which is a critical component of COVID-19 prevention and control, should significantly reduce the exposure to infection. As a matter of fact, the World Health Organization (2020) proclaims that proper sanitation and hygienic conditions are a frontline defence against infectious diseases such as COVID-19. This puzzling result could suggest that there may be obscure but more important factors that were perhaps overlooked.

Most importantly, the rather interesting observation—not simply because it defies expectations but because it largely confirms what Oppong (2020) had characterised as the “African COVID-19 anomaly”—is the negative relationship between COVID-19 and poverty. Again, this aligns with the conjecture put forward by the controversial BBC report, though from a statistical analysis standpoint. If we were to closely examine the paradoxical situation, one may find more intriguing the peculiarity of two specific countries: South Africa and Nigeria. South Africa was an outlier in the relationship between COVID-19 and poverty. It had the highest COVID-19 infection and mortality rates and very low poverty rate. This is in spite of the fact that it has comparatively strong development indicators in Africa. Nigeria, which was recently tagged the world’s poverty capital (World Poverty Clock 2019) unexpectedly has one of the lowest morbidity and mortality rates in the continent. Again, this further reinforces the spatial mismatch between COVID-19 and poverty observed among African countries.

This inquiry has not clearly, and perhaps not successfully solved the mystery: Why does Africa have fewer cases of COVID-19 infection and death than the rest of the world? There are a plethora of factors that are consistently stressed as forces shaping the African COVID-19 puzzle. This includes but may not be limited to the following: effective health emergency coordination and management, late onset–early preparedness and response, history of epidemic outbreaks and effective containment, efficacy of local/alternative medicines and Africa’s large youthful population (Hamann et al. 2020; Oppong 2020; Wadvalla 2020; Iwuoha et al. 2020; Maeda and Nkengasong 2021; Salyer et al 2021). Though it is beyond the scope of this study to verify these positions or quantify their relative contributions, it is very glaring that there is an interplay of factors at work than just poverty. Thus, the poverty-as-a-vaccine hypothesis does not hold water.

Based on the results of the multivariable regression, air traffic is the only significant predictor of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. This finding further strengthens the role of air travel in COVID-19 transmission. Onafeso et al (2021) had earlier identified the significance of air traffic in the geographical spread of the disease in Africa. They pointed out, like other scholars, that most of the index cases in Africa were imported from overseas. Similarly, Osayomi et al (2020) highlighted the relative importance of air traffic in the geographical distribution of COVID-19 in West Africa by illustrating how it puts more countries, such as Nigeria, at greater risk of infection than others. These results among others explain the several airport closures across Africa and travel bans issued by African governments on specific foreign nationals from high risk countries at the onset of the pandemic.

Conclusion

This study examined the geographical distribution of COVID-19 in Africa in relation to the poverty-as-a-vaccine hypothesis. Its major contribution to the ongoing examination of COVID-19 was the empirical verification of the controversial hypothesis. The main conclusion of the paper is that poverty does not confer protection against COVID-19 and is therefore a weak theoretical explanation for the African COVID-19 paradox. The paradox, however, could have a clearer meaning if it is further examined at a finer geographic scale. Clearly, there is a multiplicity of conflicting perspectives on the pandemic puzzle. There is still the need for further research to investigate this anomaly. More importantly, research should be directed at understanding why, in spite of the socio-economic progress in some developed countries within and outside Africa, are there many COVID-19 infections and deaths? A major limitation of this study is the time sensitive nature of the data. The number of infections and deaths increase daily and the patterns and underlying forces could change at any point in time. Another limitation was data on the number of people tested across Africa was not publicly available at the time of this research and, therefore, the study could not quantify its effects on prevalence. In light of the study’s findings, we recommend that the poverty-as-a- vaccine-hypothesis should be tested at the subnational level in African countries so as to greatly enhance our understanding of the pandemic puzzle.

Funding

There was no funding for this research.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

This study did not require ethical approval because it was based on secondary data analysis.

Consent for Publication

Upon acceptance, we give the consent to publish the article.

References

- Arashi M, Bekker A, Salehi M, Millard S, Erasmus B, Cronje T, Golpaygani M (2020). Spatial analysis and prediction of COVID-19 spread in South Africa after lockdown. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.09596

- Adepoju P. Tuberculosis and HIV responses threatened by COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;7(5):e319–e320. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataguba JE. COVID-19 pandemic, a war to be won: understanding its economic implications for Africa. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18:325–328. doi: 10.1007/s40258-020-00580-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBC News Africa. (2020). Coronavirus: John Magufuli declares Tanzania free of Covid-19. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52966016

- BBC World (2020) Coronavirus in South Africa: Scientists explore surprise theory for low death rate. https://bbc.in/2QKNZmD

- CDC. (2020). COVID-19 and Noncommunicable Diseases (NCDs). https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/COVID-19%20and%20NCDs-%20Frequently%20Asked%20Questions_June2020.pdf.

- El-Sadr WM, Justman J. Africa in the Path of Covid-19. New Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):e11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goufo EFD, Khan Y, Chaudhry QA. HIV and shifting epicenters for COVID-19, an alert for some countries. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139(2020):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann R, Muthuri JN, Nwagwu I, Pariag-Maraye N, Chamberlin W, Ghai S, Amaeshi K, Ogbechie C. COVID-19 in Africa: contextualizing impacts, responses, and prospects. Environment. 2020;62(6):8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel K, Tong B, Hofer M. (2019). Poverty in Africa is now falling-but not fast enough. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2019/03/28/poverty-in-africa-is-now-falling-but-not-fast-enough/

- Iwuoha VC, Ezeibe EN, Ezeibe CC. Glocalization of COVID-19 responses and management of the pandemic in Africa. Local Environ. 2020;25(8):641–647. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2020.1802410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iyanda AE, Adeleke R, Lu Y, Osayomi T, Adaralegbe A, Lasode M, Chima-Adaralegbe NJ, Osundina AM. A retrospective cross-national examination of COVID-19 outbreak in 175 countries: a multiscale geographically weighted regression analysis. J Infection Publ Health. 2020;13(10):1438–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaye IM, Horney JA. The impact of social vulnerability on COVID-19 in the US: an analysis of spatially varying relationships. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazeem, Y. (2020). Africa’s toughest battle with Covid-19 is getting enough tests done. https://qz.com/africa/1890208/how-many-covid-19-tests-have-african-countries-done/

- Lawal Y. Africa’s low COVID-19 mortality rate: A paradox? Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los Angeles Times. (2020). How coronavirus — a ‘rich man’s disease’—infected the poor. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-05-08/how-the-coronavirus-began-as-a-disease-of-the-rich

- PinalutMushi VM, Shao M. Tailoring of the ongoing water, sanitation and hygiene interventions for prevention and control of COVID-19. Trop Med Health. 2020;48(47):1–3. doi: 10.1186/s41182-020-00236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda JM, Nkengasong JN. The puzzle of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa. Science. 2021;371(6524):27–28. doi: 10.1126/science.abf8832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Alvarez MM, Jarde A, Usuf E, Brotherton H, Bittaye M, Samateh A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic in West Africa. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8:631–632. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Mahn D, Kioko E. Rethinking African Futures after COVID-19. Afr Spectr. 2021 doi: 10.1177/00020397211003591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nuwagira E, Muzoora C. Is sub-Saharan Africa prepared for COVID-19? Trop Med Health. 2020;48(1):1–3. doi: 10.1186/s41182-019-0188-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okafor, S. I., & Osayomi, T. (2021) Geographical Dynamics of COVID-19 in Nigeria. In Akhtar, R. (eds) Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreaks, environment and human behaviour: International Case Studies, 327.

- Olapegba, P.O and Ayandele, O and Kolawole, S. O. and Oguntayo, R ,Gandi, J. C., Dangiwa, A L. and Ottu, Iboro F. A., Iorfa, S. K., A Preliminary Assessment of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Knowledge and Perceptions in Nigeria. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3584408 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3584408

- Olusola A, Olusola B, Onafeso O, Ajiola F, Adelabu S. Early geography of the coronavirus disease outbreak in Nigeria. GeoJournal. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10708-020-10278-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onafeso OD, Onafeso TE, Olumuyiwa-Oluwabiyi GT, Faniyi MO, Olusola AO, Dina AO, Hassan AM, Folorunso SO, Adelabu S, Adagbasa E. Geographical trend analysis of COVID-19 pandemic onset in Africa. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2021;4(1):100137. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppong JR. The African COVID-19 anomaly. African Geographical Review. 2020;39(3):282–288. doi: 10.1080/19376812.2020.1794918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osayomi, T. (2020). Understanding the Geography of COVID-19 Transmission in Nigeria. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/34107839_Understanding_the_geographyof_COVID-19_transmission_in Nigeria

- Osayomi T, Adeleke R, Taiwo OJ, Gbadegesin AS, Fatayo OC, Akpoterai LE, Ayanda JT, Moyin-Jesu J, Isioye A. Cross-national variations in COVID-19 outbreak in West Africa: Where does Nigeria stand in the pandemic? Spat Inf Res. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s41324-020-00371-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raifman MA, Raifman JR. Disparities in the population at risk of severe illness from COVID-19 by race/ethnicity and income. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(1):137–139. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinault, N. (2019). Rapid Urbanization Presents New Problems for Africa. https://www.voanews.com/africa/rapid-urbanization-presents-new-problems-africa.

- Rosenthal PJ, Breman JG, Djimde AA, John CC, Kamya MR, Leke RG, Moeti MR, Nkengasong J, Bausch DG. COVID-19: shining the light on Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(6):1145. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghir, J., & Santaro, J. (2018). Urbanization in Sub-Saharan Africa. https://www.csis.org/analysis/urbanization-subsaharanafrica#:~:text=Urbanization%20is%20transforming%20the%20world.&text=The%20global%20share%20of%20African,gross%20domestic%20product%20(GDP).

- Salyer SJ, Maeda J, Sembuche S, Kebede Y, Tshangela A, Moussif M, Ihekweazu C, Mayet N, Abate E, Ouma AO, Nkengasong J. The first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1265–1275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00632-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stier, A.., Berman, M., & Bettencourt, L. (2020). COVID-19 Attack Rate Increases with City Size (March 30, 2020). Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation Research Paper. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3564464.

- Wadvalla B. How Africa has tackled COVID-19. Br Med J. 2020;370:m2830. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Measuring Living Standards within Cities. Households Surveys: Dar es Salaam and Durban. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . Cote d’Ivoire Urbanization. Review Diversified Urbanization. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2017. African cities opening door to the world. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/854221490781543956/pdf/113851-PUB-PUBLIC-PUBDATE-2-9-2017.pdf.

- World Poverty Clock (2019). World Poverty Clock. Retrieved March 8, 2020, from https://kamlafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/World-Poverty-Clock.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 72. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200401-sitrep-72-covid-19.pdf.

- You H, Wu X, Guo, x. Distribution of COVID-19 Morbidity Rate in Association with Social and Economic Factors in Wuhan, China: Implications for Urban Development. Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3417):1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]