Abstract

The molecular mechanisms of insect resistance to Cry toxins generated from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) urgently need to be elucidated to enable the improvement and sustainability of Bt-based products. Although downregulation of the expression of midgut receptor genes is a pivotal mechanism of insect resistance to Bt Cry toxins, the underlying transcriptional regulation of these genes remains elusive. Herein, we unraveled the regulatory mechanism of the downregulation of the ABC transporter gene PxABCG1 (also called Pxwhite), a functional midgut receptor of the Bt Cry1Ac toxin in Plutella xylostella. The PxABCG1 promoters of Cry1Ac-susceptible and Cry1Ac-resistant strains were cloned and analyzed, and they showed clear differences in activity. Subsequently, a dual-luciferase reporter assay, a yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assay, and RNA interference (RNAi) experiments demonstrated that a cis-mutation in a binding site of the Hox transcription factor Antennapedia (Antp) decreased the promoter activity of the resistant strain and eliminated the binding and regulation of Antp, thereby enhancing the resistance of P. xylostella to the Cry1Ac toxin. These results advance our knowledge of the roles of cis- and trans-regulatory variations in the regulation of midgut Cry receptor genes and the evolution of Bt resistance, contributing to a more complete understanding of the Bt resistance mechanism.

Keywords: Bacillus thuringiensis, Plutella xylostella, cis-mutation, Antp, ABCG1, Cry1Ac resistance

1. Introduction

Insecticidal proteins from the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) have become the most successful alternatives to chemical pesticides because of their efficient and specific insecticidal activity and their environmental benignity [1,2,3,4]. To date, biopesticides and transgenic crops based on recombinant Bt or Bt toxins have been widely used for pest control worldwide, making substantial contributions to socioeconomic development and environmental sustainability [5]. Unfortunately, the benefits and long-term application potential of Bt products are severely threatened by evolved resistance in insects [6,7]. Therefore, clarifying the molecular mechanisms of Bt resistance is essential for delaying the evolution of insect resistance to Bt Cry toxins and for sustainably utilizing Bt products.

The Bt Cry proteins exert their toxicity through multiple main steps in the larval midgut, and the interaction of Cry toxins with functional receptors is critical for their cytotoxicity, and post-binding events result in cell lysis and death [4,8,9,10]. Empirical evidence demonstrates that the functional receptors for Bt toxins in the midgut include cadherin (CAD), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aminopeptidase N (APN), and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family proteins [11,12]. Decreases in the expression of these receptor genes reduce toxin-receptor interactions and thus promote the evolution of Bt resistance in various insects [13,14]. Nevertheless, the mechanistic details of the transcriptional regulation of these midgut Cry receptor genes remain largely unknown.

The ABCG1 gene (also known as white) was the first identified ABC transporter gene in arthropods [15] and participates in diverse physiological processes. In humans, the ABCG1 gene plays important roles in cellular lipid homeostasis, cell proliferation, apoptosis, vasoconstriction, vasorelaxation, and several human diseases [16,17,18]. In insects, the ABCG1 gene is responsible for color determination of the eye, serosa, or epidermis; behavior; and detoxification of toxic substances [19]. In crustaceans, the ABCG1 gene is critical for the responses to acidic and alkaline conditions and for xenobiotic detoxification [20,21,22]. Our recent studies have suggested that ABCG1 can also act as a functional midgut receptor of the Bt Cry1Ac toxin, and its reduced expression is closely linked to Bt Cry1Ac resistance [14,23]. Although the transcriptional regulation of ABCG1 expression in humans has been explored in depth [18], information about this process in insects is sparse.

Intraspecific and interspecific variation in gene expression is common and is considered to favor adaptive evolution and species diversification [24]. Approaches used to explore the evolution of gene expression commonly focus on two components: cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors [24]. cis-acting mutations, including base mutations and insertions/deletions (indels), and changes in trans-acting factors are involved in the regulation of P450 genes that confer resistance to chemical insecticides in various insects [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway trans-regulates the differential expression of multiple midgut Cry1Ac receptor genes and non-receptor paralogous genes to mediate high-level resistance to the Bt Cry1Ac toxin in Plutella xylostella [14,23,34,35,36], suggesting that some MAPK-responsive transcription factors (TFs) are responsible for regulation of such downstream midgut genes, including PxABCG1. Nonetheless, the cis- and trans-factors that modulate the downregulation of midgut receptor genes, including ABCG1, in Bt-resistant insects are still unclear.

Here, we investigated the transcriptional regulation of the differential expression of the PxABCG1 gene in P. xylostella. Our work shows that a Hox family TF, Antennapedia (Antp), interacts with its binding site (a cis-regulatory element, CRE) in the PxABCG1 promoter of a susceptible strain to activate its expression. However, a cis-acting mutation makes Antp unable to bind to the CRE and regulate the PxABCG1 gene, which leads to downregulation of PxABCG1 gene expression and enhances resistance to the Cry1Ac toxin in P. xylostella. Our work on cis- and trans-regulation of the PxABCG1 gene adds to the body of knowledge of the roles of cis- and trans-regulatory variations in environmental adaptation and contributes to a more complete understanding of the Bt resistance mechanism.

2. Results

2.1. Cloning and Analysis of the PxABCG1 Promoter in Bt-Susceptible and Bt-Resistant Strains

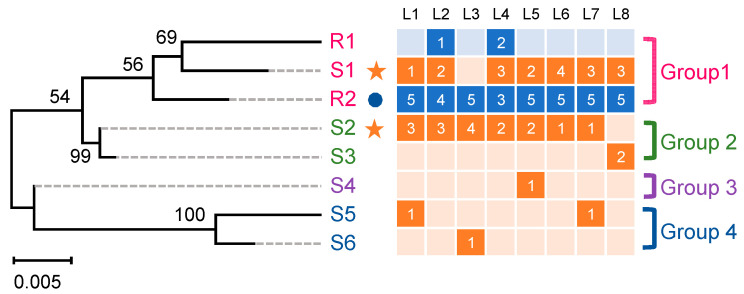

A total of eight 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) sequences of the PxABCG1 gene containing abundant single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and fragment indels were obtained from eight individuals, each of the Bt-susceptible DBM1Ac-S and Bt-resistant NIL-R strains, respectively (Figure S1). Notably, all larvae of the resistant strain exhibited only two 5′-UTR sequences (R1 and R2), while larvae of the susceptible strain obtained six corresponding sequences (S1–S6) (Figure S1). A phylogenetic analysis was performed to clarify the evolutionary relationships among these different 5′-UTR sequences of the PxABCG1 gene. The sequences clustered into four different groups (designated groups 1 to 4). The two sequences of the resistant strain were most similar to S1 of the susceptible strain; these three sequences were clustered into group 1. The other three groups were composed of different sequences of the susceptible strain (Figure 1). All the 5′-UTR sequences of the PxABCG1 gene shared high sequence identity ranging from 94.47% to 100% between and within groups (Figure S2). R2 was the dominant 5′-UTR sequence for the resistant strain, which was amplified in all eight individuals (Figure 1). Of the six 5′-UTR sequences in the susceptible strain, S1 and S2 were detected in six of the eight individuals, while the other sequences (S3–S6) were detected only in very few larvae (Figure 1). Therefore, the S1 and S2 sequences were the main promoters for the susceptible strain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of PxABCG1 promoter sequences amplified from the Bt-susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S and the Bt-resistant strain NIL-R. The phylogenetic tree was generated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method based on the model optimized using the Bayes Information Criterion with “complete deletion” as the gaps/missing data treatment and 1000 bootstrap replications. The classification of different PxABCG1 promoter sequences is shown on the right. Promoter sequences of the PxABCG1 gene were amplified from 8 susceptible DBM1Ac-S larvae and 8 resistant NIL-R larvae, respectively. L1 to L8 above represents each susceptible or resistant larva, and five clones from each larva were sequenced. Squares shaded in orange and blue represent susceptible and resistant larvae, respectively, and the number within the squares shows the number of the corresponding promoter detected in the 5 sequenced clones per larva. The orange star and the blue circle denote the major type of PxABCG1 promoter sequences in the susceptible and resistant larvae, respectively.

2.2. PxABCG1 Promoter Activity Differs between Bt-Susceptible and Bt-Resistant Strains

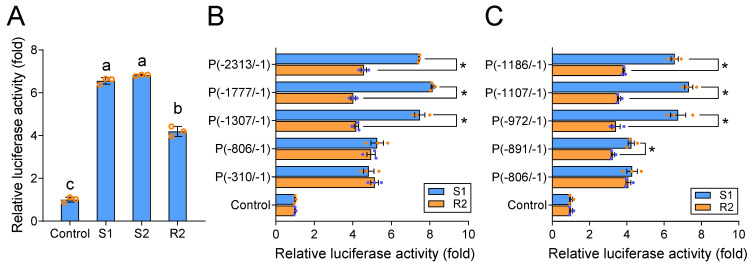

To explore whether the differences in the 5′-UTR sequence of the PxABCG1 gene between the Bt-susceptible and Bt-resistant strains can affect promoter activity and thus lead to differential expression of the PxABCG1 gene, the full-length sequences of R2, S1, and S2 were subcloned into the pGL4.10 plasmid. The resulting plasmids were transfected into S2 cells, and the promoter activity was detected. The results showed that the activity of S1 and S2 was significantly higher than that of R2 (Figure 2A), indicating that the different 5′-UTRs result in different promoter activity levels and affect the transcript levels of the PxABCG1 gene in Bt-susceptible and Bt-resistant strains.

Figure 2.

Detection of promoter activity by dual luciferase reporter assay. (A) Analysis of the activity of the primary PxABCG1 resistance promoter (R2) and the main PxABCG1 susceptibility promoter (wild-type S1/S2). The relative luciferase activity (firefly luciferase activity/Renilla luciferase activity) of different pGL4.10-promoter plasmids was normalized to that of the control pGL4.10 vector. The values shown are the means and the corresponding standard error of the mean (SEM) values for three biological replicates and four technical replicates. The significance of differences was determined by one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences. (B) Activity of progressive 5′ deleted recombinants of the S1 and R2 promoters after shortening from −2313 to −310. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis (*, p < 0.05). (C) Activity of progressive 5′ deletion constructs created through shortening of the sequence from −1186 to −806. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis (*, p < 0.05).

To further locate the sites leading to the different activity levels of the susceptible and resistant promoters, we used S1 and R2 as templates to construct a series of progressive 5′ deleted recombinants and measured their activity levels. When the promoters were truncated from −1307 to −806, the promoter activity of S1 was significantly decreased and became similar to the R2 activity (Figure 2B), suggesting that the elements responsible for the differential activity of the PxABCG1 promoter S1 are located within the fragment from −1307 to −806 (Figure 2B).

To narrow down the location of the possible cis-acting element, we further shortened the S1 and R2 promoter regions from −1307 to −806. The differential activity between S1 and R2 remarkably reduced when the promoters were truncated from −972 to −891, and disappeared once sequences upstream of position −806 were removed (Figure 2C). These results suggest that the promoter region with differential activity between susceptible and resistant strains is located in the region from −972 to −806, especially the region between −972 and −891.

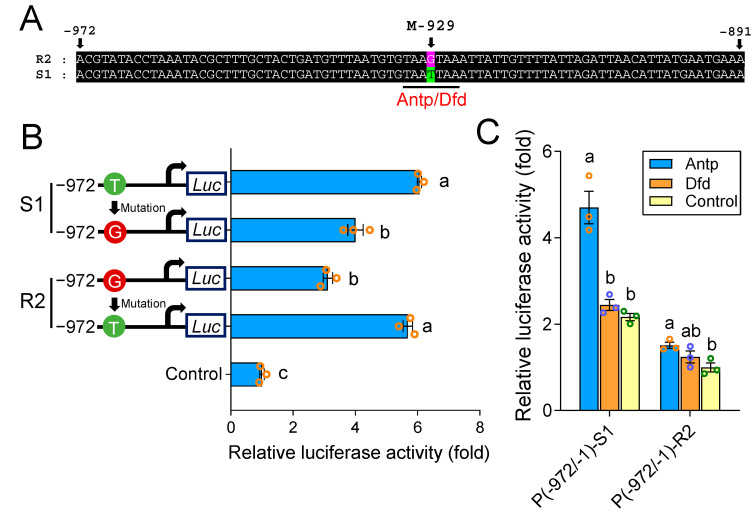

2.3. A cis-Acting Mutation in the Binding Site of Antp Reduces PxABCG1 Promoter Activity

Nucleotide sequence alignment of the region from −972 to −891 showed that there was only a single point mutation (M-929) difference at nucleotide −929 between the S1 and R2 promoters (Figure 3A). To probe whether this mutation can result in a difference in promoter activity, we used the P(-972/-1) constructs of S1 and R2 as templates and performed directed mutation at this site. The point mutation at M-929 (from T to G) significantly reduced the activity of P(-972/-1)-S1, whereas the change from G to T elevated the activity of P(-972/-1)-R2 (Figure 3B). This indicated that M-929 was primarily responsible for the difference in PxABCG1 promoter activity between −972 and −891. A binding site (CRE, TAATTAA, −932 to −925) of Antp and Deformed (Dfd) was predicted to occur near M-929 in the S1 promoter, and the point mutation in M-929 led to CRE disappearance in the R2 promoter of the resistant strain (Figure 3A), suggesting that the disappearance of the CRE may cause Antp and/or Dfd to be unable to bind to the promoter and thus reduces PxABCG1 expression in the Bt-resistant strain. To test this hypothesis, expression vectors for Antp and Dfd were constructed and cotransfected with P(-972/-1). The data showed that Dfd did not obviously affect S1 and R2 but that Antp enhanced the activity of S1 but not that of R2 (Figure 3C), indicating that Antp is involved in PxABCG1 expression regulation in the susceptible strain.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the point mutation between −972 and −891. (A) Nucleotide sequence alignment of the fragment from −972 and −891 in PxABCG1 promoters S1 and R2. (B) Activity of the promoters P(-972/-1)-S1 and P(-972/-1)-R2 with site-directed mutagenesis at M-929. The empty pGL4.10 vector was used as a control. The significance of differences was determined by one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences. (C) Effects of Antp and Dfd on the activity levels of PxABCG1 promoters S1 and R2. The empty pAc5.1 vector was used for controls. The significance of differences was determined by one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences.

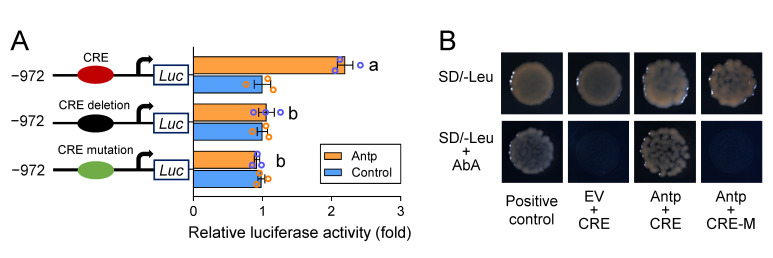

2.4. A cis-Acting Mutation Causes Antp to Fail to Bind to the Promoter and Regulate PxABCG1

To further verify whether the cis-acting mutation in the predicted binding site affects the positive regulation of Antp in the PxABCG1-susceptible promoter, the CRE (TAATTAA, −932 to −925) in P(-972/-1)-S1 was deleted or mutated to TAAGTAA. Antp was then cotransfected into S2 cells with P(-972/-1)-S1 containing a normal, deleted, or mutant CRE. Antp could not trigger the activity of the PxABCG1 promoter after deletion or mutation of the CRE (Figure 4A). A yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assay was further performed to detect the interaction between Antp and the normal or mutant CRE. Y1HGold strains transformed with Antp, and the normal CRE grew normally on the medium lacking leucine (Leu) and supplemented with aureobasidin A (AbA) (Figure 4B). These results indicate that Antp positively regulates the expression of the PxABCG1 gene through the CRE in the promoter of the susceptible strain and that the cis-acting mutation in the Antp CRE prevents the binding and regulation of Antp.

Figure 4.

Antp positively regulates PxABCG1 promoter activity through the CRE. (A) Effect of Antp on the activity of the PxABCG1 promoter with either a deletion or a mutation in the CRE. The CRE (TAATTAA, −932 to −925) in P(-972/-1)-S1 was deleted or mutated to TAAGTAA. Antp was cotransfected with P(-972/-1)-S1 containing a normal CRE (red ellipse), lacking a CRE (black ellipse), or containing a mutant CRE (green ellipse). The empty pAc5.1 vector was used as a control. One-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test was used for statistical analysis (p < 0.05). Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences. (B) Investigation of the direct interaction between Antp and the CRE using a Y1H assay. Bait vectors containing three tandem repeats with the normal or mutant CRE and a prey vector containing Antp were transferred into the Y1HGold yeast strain. The yeast was grown on SD/-Leu selective medium with or without AbA. EV, empty prey vector; positive control, pGADT7-p53 + pABAi-p53.

2.5. Antp-Mediated Positive Regulation of PxABCG1 In Vivo Is Eliminated in the Bt-Resistant Strain

The TF Antp, which belongs to the Hox family, contains a conserved homeodomain in the C-terminus responsible for specific DNA binding and a YPWM motif adjacent to the homeobox in the N-terminus that typically mediates protein dimerization (Figures S3 and S4) [37]. A phylogenetic analysis of Antp was performed to clarify the evolutionary history of Antp proteins in diverse insects. The Antp proteins were evolutionarily conserved and clearly clustered into groups corresponding to the insect orders (Figure S3).

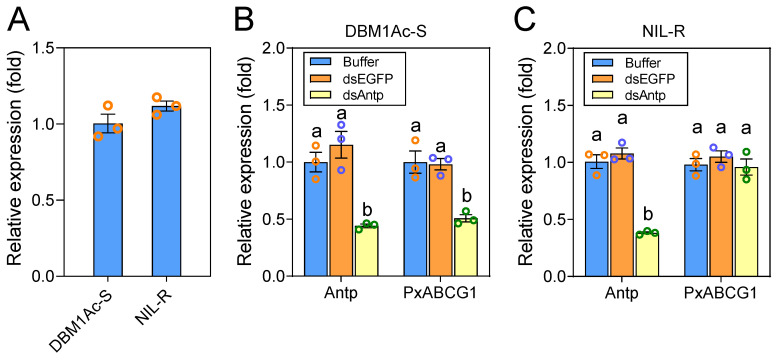

To investigate whether Antp participates in resistance to Cry1Ac toxin in P. xylostella by controlling the Bt receptor gene PxABCG1, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was first conducted to detect Antp expression levels in the midgut tissues of the Bt-susceptible and Bt-resistant strains. The transcript level of the midgut Antp gene was not significantly different between the susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S and the resistant strain NIL-R (Figure 5A), excluding the possibility that variation in Antp expression is related to Bt resistance. Furthermore, RNA interference (RNAi) was performed in susceptible and resistant larvae to investigate whether Antp regulates PxABCG1 expression in vivo. After Antp silencing, the expression level of the PxABCG1 gene was decreased significantly in the susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S (Figure 5B). However, downregulation of Antp did not have an effect on PxABCG1 expression in the resistant strain NIL-R (Figure 5C). These in vivo results indicate that Antp positively regulates PxABCG1 gene expression in the susceptible strain but is unable to regulate PxABCG1 in the Bt-resistant strain.

Figure 5.

Effect of Antp on PxABCG1 expression in vivo. (A) Relative expression of the midgut Antp gene in 4th-instar larvae of the susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S and the resistant strain NIL-R. The RPL32 gene was used as an internal control. The average relative expression level and standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent replicates are presented. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis (p < 0.05). (B) Relative expression of Antp and PxABCG1 in larvae of the susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S at 48 h post injection with buffer, dsEGFP, or dsAntp. The expression levels of Antp or PxABCG1 in the control larvae injected with buffer were set as 1. Different letters among groups indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05; Duncan’s test; n = 3). Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences. (C) Relative expression of Antp and PxABCG1 in larvae of the resistant strain NIL-R at 48 h post injection with buffer, dsEGFP, or dsAntp. Different letters on the bars indicate significant differences.

3. Discussion

Variations in gene expression, which are ubiquitous within populations and between species, are considered to be the raw material for evolution and to contribute to adaptive evolution [24,38,39]. Decreased expression of midgut Bt receptor genes is one of the primary reasons for insects developing high-level Bt resistance. However, little is known about the transcriptional regulation of the differential expression of these genes. In this study, we revealed that Antp positively regulates the expression of the Cry1Ac receptor gene PxABCG1 and that a cis-acting mutation causes Antp to fail to activate PxABCG1 expression, thus increasing resistance to the Cry1Ac toxin in P. xylostella.

Numerous studies support the idea that cis-variation of individual or multiple genes contributes to the evolution of gene expression and to environmental adaptability in eukaryotes [40,41]. It is generally believed that cis-evolution is less pleiotropic and more common in “structural” genes such as protease genes, which do not directly affect the expression of other genes compared with regulatory genes [24]. In insects, cis-variation, including base mutation and fragment insertion/deletion in the 5′-UTR, can cause constitutive overexpression of P450 genes and result in phenotypes of resistance to chemical pesticides [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. For example, transposable element insertions into the 5′-UTR of the Cyp6g1 gene cause overexpression of this gene at the transcriptional level, conferring DDT resistance in Drosophila melanogaster [25,26]. In addition, a single nucleotide change in a core promoter is involved in CYP9M10 gene overexpression in pyrethroid-resistant Culex quinquefasciatus [27]. Overexpression of CYP6CY3, which confers resistance to the plant alkaloid nicotine and neonicotinoids in Myzus persicae, is related to the insertion of dinucleotide microsatellites in the promoter [28]. Multiple mutations in cis-acting elements lead to increased expression of CYP6FU1 and confer resistance to deltamethrin in Laodelphax striatellus [29]. Moreover, cis-regulatory variants of CYP6P9a- and CYP6P9b-mediated gene overexpression are associated with pyrethroid resistance in the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus [30,31]. Recently, a cis-acting mutation was found to increase CYP321A8 expression and chlorpyrifos resistance in Spodoptera exigua [32]. Rather than P450 gene overexpression, which enhances metabolic detoxification and causes insect resistance to chemical insecticides, the molecular mechanism of insect resistance to Bt toxins is closely linked to the downregulation of midgut Bt receptor genes. Our study provides evidence of a cis-acting mutation that reduces the expression of the midgut Bt receptor gene PxABCG1. This result advances understanding of how cis-acting mutations contribute to the subtle control of gene expression and the evolution of Bt resistance.

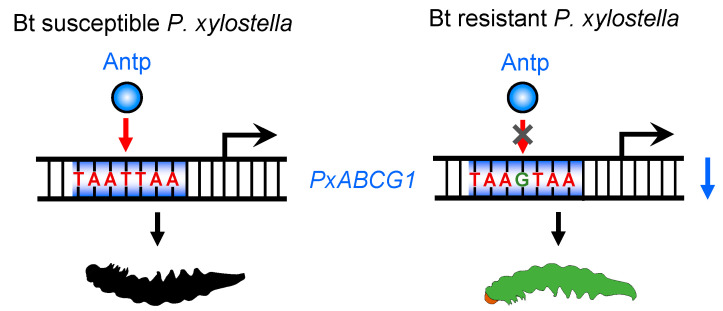

Functional divergence of cis-acting elements resulting from nucleotide substitutions, insertions, and/or deletions usually disrupts TF binding [42]. Some potential binding sites of TFs were thought to be changed due to cis-acting mutations in P450 gene promoters in the studies producing the abovementioned findings; however, corresponding specific trans-factors that act in concert with predicted binding sites have rarely been identified and verified. A recent study demonstrated that a cis-acting mutation increases CYP321A8 expression by creating a binding site for Knirps [32]. In this study, we demonstrated that the binding site of Antp was altered from the PxABCG1 promoter in the resistant strain and that the cis-acting mutation disrupted Antp binding and decreased PxABCG1 expression, conferring resistance to the Cry1Ac toxin in P. xylostella (Figure 6). Increased understanding of the interaction between cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors related to Bt resistance will enable more complete and accurate appreciation of the Bt resistance mechanism. Notably, the cis-variation in the PxABCG1 promoter can be exploited in a DNA-based assay to detect the frequency and distribution of midgut Bt receptor-mediated Cry1Ac resistance in P. xylostella [30,31], which will make a crucial contribution to Bt resistance management.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the transcriptional regulation of reduced PxABCG1 expression. In the Cry1Ac resistant strain P. xylostella, a cis-acting mutation in the binding site of Antp prevents Antp binding and downregulates PxABCG1 expression, thereby enhancing larval resistance to Cry1Ac toxin. The black larva denotes larval death, and the green larva represents larval survival.

Hox family members, which form a highly conserved subclass of the homeodomain superfamily, are master regulators that determine cellular fates during embryonic morphogenesis and maintain tissue architecture [43,44]. Antp, a Hox family protein, was originally discovered in D. melanogaster, and its mutation causes abnormal body formation during embryogenesis [45]. Since the discovery of Antp, studies in Bombyx mori have demonstrated that Antp regulates the region-specific expression of multiple silk protein genes, including sericin-1, sericin-3, fhxh4, and fhxh5, in the middle silk gland [46,47]. Although the important regulatory role of Antp in normal growth and development has been corroborated, no study has investigated its function in insect resistance to chemical pesticides or biological pesticides. Here, we verified a new target gene of Antp, the Cry1Ac receptor gene PxABCG1, which is activated by Antp via a classical binding site. A cis-acting mutation in the PxABCG1 promoter results in the failure of Antp to regulate PxABCG1, thus enhancing larval resistance to the Cry1Ac toxin. Conserved TFs, including Hox proteins, can acquire new target genes through evolutionary processes [48]. For example, alterations in some target genes of Ultrabithorax (Ubx) are associated with the diversification of insect wings [49,50]. Considering that the other roles of Antp remain largely unexplored, identification of more target genes and functional binding sites of Antp will contribute to our understanding of the in vivo functions of Hox proteins.

Despite the finding that a cis-acting mutation is related to reduced expression of the PxABCG1 gene, in vivo evidence is needed to verify the effects of this point mutation on PxABCG1 expression and Cry1Ac resistance in P. xylostella further. Recently, the novel CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique has been applied to probe gene functions in diverse species [51]. This powerful tool also plays a critical role in the dissection of the transcriptional regulation of functional genes by enabling the generation of cis-acting mutations or mutagenesis of the coding DNA sequences of trans-acting factors [37]. However, the mutation of trans-acting factors usually leads to complete loss of function with pleiotropic effects [52], especially for some regulators essential for normal growth and development, such as Hox factors, and dysregulation of these genes can lead to abnormal development and malignant tumors in humans [44]. In contrast, editing of the cis-acting elements of target genes provides the possibility of generating a series of alleles with different transcript levels, thus assisting in the exploration of the effect of cis-variation on gene expression and the fine-tuning of target expression [37,52]. In the tomato, new alleles with varying expression levels have been generated to optimize the inflorescence architecture by using CRISPR to target the cis-acting elements of the SEPALLATA4 and FRUITFULL genes [53]. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the Vrille (Vri) binding site in the enhancer in the male Daphnia magna genome results in reduced expression of the Dsx1 gene [54]. We have also successfully applied the CRISPR/Cas9 system to knock out the PxAPN1, PxAPN3a, PxABCC2, and PxABCC3 genes in P. xylostella in order to validate the roles of these genes in Cry1Ac resistance [23,36]. Functional verification of cis-acting mutations with CRISPR/Cas9 technology will be conducive to illuminating the in vivo effect of cis-variation on PxABCG1 expression in P. xylostella.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that the activated MAPK signaling pathway trans-regulates the differential expression of multiple midgut Bt receptor genes, including PxABCG1, to confer high-level resistance to the Cry1Ac toxin in P. xylostella [14,23,34,35,36], indicating that one or more TFs downstream respond to the MAPK signaling pathway to modulate the expression of these genes. Indeed, our recent study has revealed that MAPK-activated PxJun represses the expression of the midgut Bt receptor gene PxABCB1 and thus increases larval resistance to the Cry1Ac toxin [55]. Thus, in addition to cis-variation, trans-acting factors downstream of MAPK likely also participate in the downregulation of the PxABCG1 gene. This possibility will be investigated in future studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Insect Strains and Cell Line

The Bt-susceptible P. xylostella strain DBM1Ac-S and the near-isogenic Cry1Ac-resistant strain NIL-R were used in this study, as described in detail previously [35,56,57]. Briefly, the DBM1Ac-S strain has been kept continuously for more than 10 years in our laboratory without exposure to any pesticides. The NIL-R strain exhibits over 4000-fold greater resistance to the Bt Cry1Ac protoxin than the susceptible DBM1Ac-S strain. The larvae were reared on Jing Feng No. 1 cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) at 25 °C under 65% relative humidity (RH) and a 16:8 (light:dark) photoperiod. The adults were supplied with a 10% honey/water solution.

Drosophila S2 cells for the dual-luciferase reporter assay were cultured in a HyClone SFX-insect medium (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Rockville, MD, USA) at 27 °C.

4.2. Toxin Preparation and Bioassay

The Cry1Ac protoxin preparation and leaf-dip bioassay were carried out as described previously [14,58]. Briefly, the Cry1Ac protoxin was extracted and purified from Bt var. kurstaki (Btk) strain HD-73 and then quantified and stored in 50 mM Na2CO3 (pH 9.6) at −20 °C for subsequent use. A three-day leaf-dip bioassay was performed using third-instar larvae with ten per group and four replicates. The control mortality did not exceed 5%.

4.3. Extraction of DNA and RNA

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from individual fourth-instar larvae from the Bt-susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S and the resistant strain NIL-R using a TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) from midgut tissue that was dissected from fourth-instar larvae in ice-cold insect Ringer’s solution (130 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2). First-strand cDNA used for gene cloning or qPCR was synthesized using a PrimeScript II First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Dalian, China) or a PrimeScript RT Kit (with gDNA Eraser, Perfect Real Time) (Takara, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. The obtained samples were stored at −20 °C until use.

4.4. Cloning of the Promoter and TFs

A pair of specific PCR primers (Table S1) was designed to amplify the PxABCG1 promoter based on the 5′-UTR sequence of the PxABCG1 gene in the P. xylostella genome from the DBM-DB (http://116.62.11.144/DBM/index.php, accessed date: 4 November 2019) and LepBase (http://ensembl.lepbase.org/Plutella_xylostella_pacbiov1/Info/Index, accessed date: 4 November 2019). Then, large-scale cloning and sequencing of the PxABCG1 promoter were conducted for the Bt-susceptible DBM1Ac-S strain and the resistant NIL-R strain (gDNA as template, 8 samples per strain, and 5 positive clones of each sample for sequencing) to identify potential sequence variations. PrimeSTAR Max DNA Polymerase (Takara, Dalian, China) was used for PCR amplification following the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR products were subsequently purified and subcloned into pEASY-T1 vectors (TransGen, Beijing, China) for further sequencing.

The coding sequences (CDSs) of Antp and Dfd in P. xylostella were retrieved from the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed date: 7 June 2020) under accession numbers XM_011557407 and XM_038120187, respectively. The CDSs were further corrected with our previous P. xylostella midgut transcriptome database [59]. The full-length CDSs were amplified using their corresponding specific primers (Table S2).

4.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

The obtained CDSs of the TFs were translated into amino acid sequences using the ExPASy translate tool (https://web.expasy.org/translate/, accessed date: 19 June 2020). The DNA and protein sequences were analyzed and aligned using DNAMAN 7.0 software (Lynnon Biosoft, USA). Multiple sequence alignment was conducted using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/, accessed date: 13 March 2021), and the results were further formatted using GeneDoc 2.7 software (http://genedoc.software.informer.com/2.7/, 13 March 2021). Potential CREs for TF binding in the PxABCG1 promoter were predicted with the JASPAR database (http://jaspar.genereg.net, accessed date: 6 June 2020) and the PROMO virtual laboratory (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3, accessed date: 6 June 2020). The sequence similarity among different promoter sequences was analyzed using the BLAST at the NCBI website (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, 16 December 2019). A phylogenetic tree to clarify the phylogenetic relationships of different 5′-UTR sequences was generated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA 7.0 software (https://www.megasoftware.net/, 16 December 2019). The conserved domains of the Antp protein were analyzed using the Conserved Domain Database (CDD) at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/, 14 March 2021). A phylogenetic tree of Antp proteins in different insects was built using MEGA 7.0 software with the neighbor-joining (NJ) method.

4.6. Dual-Luciferase Assay

The two most common sequences of PxABCG1 promoters in the susceptible strain (S1 and S2) and the primary promoter in the resistant strain (R2) were used for analysis and for a comparison of promoter activity. The full-length promoter and a series of 5′-truncated promoters were amplified using specific primers (Table S1) and subcloned into the firefly luciferase reporter vector pGL4.10 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to prepare pGL4.10-promoter constructs. Promoter fragments with CRE deletion or point mutation were obtained by gene synthesis (TsingKe, Nanjing, China). The CDSs of the TFs were amplified using their corresponding primers (Table S2) and subcloned into the pAc5.1/V5-His B (hereinafter called “pAc5.1”) expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The pGL4.73 vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) containing a Renilla luciferase gene was used as an internal control.

Cell transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). S2 cells were cultured in 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well. To detect promoter activity, the promoter constructs (600 ng) were cotransfected with the pGL4.73 plasmid (200 ng), and the empty pGL4.10 vector was used as a control. To evaluate the regulatory effects of TFs on the promoter, TF expression plasmids (600 ng), promoter constructs (200 ng), and the pGL4.73 vector (100 ng) were cotransfected into S2 cells, and the empty pAc5.1 plasmid was used as a control. After 48 h of transfection, the cells were collected, and the luciferase activity was measured on a GloMax 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) by using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The relative luciferase activity (firefly luciferase activity/Renilla luciferase activity) of different pGL4.10-promoter plasmids was normalized to that of the control pGL4.10 vector. Each experiment was replicated three times. One-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test was used for analysis of the significant differences (p < 0.05).

4.7. Y1H Assay

A Y1H assay was performed to verify the direct interaction between Antp and the normal/mutant CRE using a Matchmaker Gold Yeast One-Hybrid System (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) according to the recommended protocol. Bait plasmids (CRE and CRE-M) were generated by ligating three tandem repeats that contain the normal CRE (5′- taatgtgTAATTAAattatt-3′) or mutant CRE (5′-taatgtgTAAGTAAattatt-3′) into the pAbAi vector between the XhoI and HindIII restriction sites. The bait plasmids were linearized with BstBI and integrated into Y1HGold yeast to generate the bait strains and were then selected on SD/-Ura medium. The minimum concentration of AbA that inhibited the normal growth of the bait strains on SD/-Ura medium was 600 ng/mL. The prey plasmid containing Antp was constructed by subcloning the CDS into the pGADT7 vector, which was then transformed into the bait strains. Selection was performed on a SD/-Leu medium with 600 ng/mL AbA. The positive control was the Y1HGold strain cotransformed with the pGADT7-p53 and pAbAi-p53 plasmids, and the negative control was the Y1HGold strain cotransformed with the empty vector pGADT7 and the normal pAbAi-CRE plasmid.

4.8. qPCR Analysis

As mentioned previously [14,34], the expression of the Antp and PxABCG1 genes was quantified by qPCR using the specific primers listed in Table S3. The qPCR experiment was run on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) using FastFire qPCR PreMix (SYBR Green) (Tiangen, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each experiment was performed with three biological replicates and four technical replicates. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method and normalized to the level of the internal control ribosomal protein L32 (RPL32) gene (GenBank accession no. AB180441). One-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test was used for analysis of the significant differences (p < 0.05).

4.9. RNAi

Silencing of Antp expression was carried out in larvae of the Bt-susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S and the resistant strain NIL-R via RNAi. Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) preparation, dsRNA microinjection, midgut RNA extraction, qPCR, and bioassays were performed as mentioned previously [60]. Briefly, the cDNA fragments of Antp or EGFP to be used for dsRNA synthesis were amplified using gene-specific dsRNA primers containing a T7 promoter on the 5′ end (Table S3). Then, dsAntp and dsEGFP were synthesized using a T7 RiboMAX Express RNAi System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Thirty larvae were microinjected with buffer, dsEGFP (300 ng), or dsAntp (300 ng). Each treatment was performed with three biological replicates. The expression levels of Antp and PxABCG1 were detected by qPCR. One-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test was used for analysis of the significant differences (p < 0.05).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms22116106/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Q. and Z.G.; investigation, J.Q., F.Y., L.X. and Z.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Q. and Z.G.; writing—review and editing, J.Q., X.Z. (Xuguo Zhou), X.Z. (Xiaomao Zhou), N.C., Y.Z. and Z.G.; supervision, X.Z. (Xiaomao Zhou), Y.Z. and Z.G.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and Z.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31630059; 31701813; 32022074), the Beijing Key Laboratory for Pest Control and Sustainable Cultivation of Vegetables, and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-IVFCAAS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bravo A., Likitvivatanavong S., Gill S.S., Soberón M. Bacillus thuringiensis: A Story of a Successful Bioinsecticide. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011;41:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanahuja G., Banakar R., Twyman R.M., Capell T., Christou P. Bacillus thuringiensis: A Century of Research, Development and Commercial Applications. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011;9:283–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchis V. From Microbial Sprays to Insect-Resistant Transgenic Plants: History of the Biopesticide Bacillus thuringiensis. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2011;31:217–231. doi: 10.1051/agro/2010027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jurat-Fuentes J.L., Heckel D.G., Ferre J. Mechanisms of Resistance to Insecticidal Proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021;66:121–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-052620-073348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ISAAA . ISAAA Brief No. 55. Cornell University; Ithaca, NY, USA: 2019. Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops in 2019: Biotech Crops Drive Socio-Economic Development and Sustainable Environment in the New Frontieri. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabashnik B.E., Brévault T., Carrière Y. Insect Resistance to Bt Crops: Lessons from the First Billion Acres. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:510–521. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabashnik B.E., Carrière Y. Surge in Insect Resistance to Transgenic Crops and Prospects for Sustainability. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:926–935. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardo-López L., Soberón M., Bravo A. Bacillus thuringiensis Insecticidal Three-Domain Cry Toxins: Mode of Action, Insect Resistance and Consequences for Crop Protection. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013;37:3–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jurat-Fuentes J.L., Crickmore N. Specificity Determinants for Cry Insecticidal Proteins: Insights from Their Mode of Action. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017;142:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Bortoli C.P., Jurat-Fuentes J.L. Mechanisms of Resistance to Commercially Relevant Entomopathogenic Bacteria. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2019;33:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pigott C.R., Ellar D.J. Role of Receptors in Bacillus thuringiensis Crystal Toxin Activity. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:255–281. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00034-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu C., Chakrabarty S., Jin M., Liu K., Xiao Y. Insect ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporters: Roles in Xenobiotic Detoxification and Bt Insecticidal Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:2829. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adang M.J., Crickmore N., Jurat-Fuentes J.L. Diversity of Bacillus thuringiensis Crystal Toxins and Mechanism of Action. Adv. Insect Physiol. 2014;47:39–87. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo Z., Kang S., Zhu X., Xia J., Wu Q., Wang S., Xie W., Zhang Y. Down-Regulation of a Novel ABC Transporter Gene (Pxwhite) Is Associated with Cry1Ac Resistance in the Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella (L.) Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015;59:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewart G.D., Howells A.J. ABC Transporters Involved in Transport of Eye Pigment Precursors in Drosophila melanogaster. In: Ambudkar S.V., Gottesman M.M., editors. ABC Transporters: Biochemical, Cellular, and Molecular Aspects, Methods Enzymol. Volume 292. Academic Press; San Diego, CA, USA: 1998. pp. 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarr P.T., Tarling E.J., Bojanic D.D., Edwards P.A., Baldan A. Emerging New Paradigms for ABCG Transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1791:584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr I.D., Haider A.J., Gelissen I.C. The ABCG Family of Membrane-Associated Transporters: You Don’t Have to Be Big to Be Mighty. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;164:1767–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frambach S.J.C.M., de Haas R., Smeitink J.A.M., Rongen G.A., Russel F.G.M., Schirris T.J.J. Brothers in Arms: ABCA1-and ABCG1-Mediated Cholesterol Efflux as Promising Targets in Cardiovascular Disease Treatment. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020;72:152–190. doi: 10.1124/pr.119.017897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dermauw W., Van Leeuwen T. The ABC Gene Family in Arthropods: Comparative Genomics and Role in Insecticide Transport and Resistance. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014;45:89–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J., He W.Y., Wang W.N., Yang C.W., Wang L., Xin Y., Wu J., Cai D.X., Liu Y., Wang A.L. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of an ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transmembrane Transporter from the White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 2009;150:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang Z.Q., Li J., Liu P., Kuo M.M.C., He Y.Y., Chen P., Li J.T. cDNA Cloning and Expression Profile Analysis of an ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter in the Hepatopancreas and Intestine of Shrimp Fenneropenaeus Chinensis. Aquaculture. 2012;356:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2012.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhai Q.Q., Li J., Chang Z.Q. cDNA Cloning, Characterization and Expression Analysis of ATP-Binding Cassette Transmembrane Transporter in Exopalaemon carinicauda. Aquac. Res. 2017;48:4143–4154. doi: 10.1111/are.13234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Z., Kang S., Sun D., Gong L., Zhou J., Qin J., Guo L., Zhu L., Bai Y., Ye F., et al. MAPK-Dependent Hormonal Signaling Plasticity Contributes to Overcoming Bacillus thuringiensis Toxin Action in an Insect Host. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3003. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16608-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Signor S.A., Nuzhdin S.V. The Evolution of Gene Expression in cis and Trans. Trends Genet. 2018;34:532–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daborn P.J., Yen J.L., Bogwitz M.R., Le Goff G., Feil E., Jeffers S., Tijet N., Perry T., Heckel D., Batterham P., et al. A Single P450 Allele Associated with Insecticide Resistance in Drosophila. Science. 2002;297:2253–2356. doi: 10.1126/science.1074170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt J.M., Good R.T., Appleton B., Sherrard J., Raymant G.C., Bogwitz M.R., Martin J., Daborn P.J., Goddard M.E., Batterham P., et al. Copy Number Variation and Transposable Elements Feature in Recent, Ongoing Adaptation at the Cyp6g1 Locus. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itokawa K., Komagata O., Kasai S., Tomita T. A Single Nucleotide Change in a Core Promoter Is Involved in the Progressive Overexpression of the Duplicated CYP9M10 Haplotype Lineage in Culex quinquefasciatus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015;66:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bass C., Zimmer C.T., Riveron J.M., Wilding C.S., Wondji C.S., Kaussmann M., Field L.M., Williamson M.S., Nauen R. Gene Amplification and Microsatellite Polymorphism Underlie a Recent Insect Host Shift. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:19460–19465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314122110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pu J., Sun H., Wang J., Wu M., Wang K., Denholm I., Han Z. Multiple cis-Acting Elements Involved in Up-Regulation of a Cytochrome P450 Gene Conferring Resistance to Deltamethrin in Smal Brown Planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus (Fallén) Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016;78:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weedall G.D., Mugenzi L.M.J., Menze B.D., Tchouakui M., Ibrahim S.S., Amvongo-Adjia N., Irving H., Wondji M.J., Tchoupo M., Djouaka R., et al. A Cytochrome P450 Allele Confers Pyrethroid Resistance on a Major African Malaria Vector, Reducing Insecticide-Treated Bednet Efficacy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11:eaat7386. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat7386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mugenzi L.M.J., Menze B.D., Tchouakui M., Wondji M.J., Irving H., Tchoupo M., Hearn J., Weedall G.D., Riveron J.M., Wondji C.S. cis-Regulatory CYP6P9b P450 Variants Associated with Loss of Insecticide-Treated Bed Net Efficacy against Anopheles funestus. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4652. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12686-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu B., Huang H., Hu S., Ren M., Wei Q., Tian X., Elzaki M.E.A., Bass C., Su J., Reddy Palli S. Changes in Both Trans- and cis-Regulatory Elements Mediate Insecticide Resistance in a Lepidopteron Pest, Spodoptera exigua. PLoS Genet. 2021;17:e1009403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilding C.S. Regulating Resistance: Cncc:Maf, Antioxidant Response Elements and the Overexpression of Detoxification Genes in Insecticide Resistance. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018;27:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou J., Guo Z., Kang S., Qin J., Gong L., Sun D., Guo L., Zhu L., Bai Y., Zhang Z., et al. Reduced Expression of the P-Glycoprotein Gene Pxabcb1 Is Linked to Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac Toxin in Plutella xylostella (L.) Pest Manag. Sci. 2020;76:712–720. doi: 10.1002/ps.5569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Z., Kang S., Chen D., Wu Q., Wang S., Xie W., Zhu X., Baxter S.W., Zhou X., Jurat-Fuentes J.L., et al. MAPK Signaling Pathway Alters Expression of Midgut ALP and ABCC Genes and Causes Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac Toxin in Diamondback Moth. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo Z., Sun D., Kang S., Zhou J., Gong L., Qin J., Guo L., Zhu L., Bai Y., Luo L., et al. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Knockout of Both the Pxabcc2 and Pxabcc3 Genes Confers High-Level Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac Toxin in the Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella (L.) Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019;107:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo Z., Qin J., Zhou X., Zhang Y. Insect Transcription Factors: A Landscape of Their Structures and Biological Functions in Drosophila and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3691. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitehead A., Crawford D.L. Variation Within and Among Species in Gene Expression: Raw Material for Evolution. Mol. Ecol. 2006;15:1197–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uusi-Heikkilä S., Sävilammi T., Leder E., Arlinghaus R., Primmer C.R. Rapid, Broad-Scale Gene Expression Evolution in Experimentally Harvested Fish Populations. Mol. Ecol. 2017;26:3954–3967. doi: 10.1111/mec.14179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stern D.L., Orgogozo V. The Loci of Evolution: How Predictable Is Genetic Evolution? Evolution. 2008;62:2155–2177. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rebeiz M., Williams T.M. Using Drosophila Pigmentation Traits to Study the Mechanisms of cis-Regulatory Evolution. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017;19:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wittkopp P.J., Kalay G. cis-Regulatory Elements: Molecular Mechanisms and Evolutionary Processes Underlying Divergence. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;13:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nrg3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akam M. Hox and HOM: Homologous Gene Clusters in Insects and Vertebrates. Cell. 1989;57:347–349. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu M., Zhan J., Zhang H. HOX Family Transcription Factors: Related Signaling Pathways and Post-Translational Modifications in Cancer. Cell. Signal. 2020;66:109469. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneuwly S., Klemenz R., Gehring W.J. Redesigning the Body Plan of Drosophila by Ectopic Expression of the Homoeotic Gene Antennapedia. Nature. 1987;325:816–818. doi: 10.1038/325816a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimoto M., Tsubota T., Uchino K., Sezutsu H., Takiya S. Hox Transcription Factor Antp Regulates Sericin-1 Gene Expression in the Terminal Differentiated Silk Gland of Bombyx mori. Dev. Biol. 2014;386:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsubota T., Tomita S., Uchino K., Kimoto M., Takiya S., Kajiwara H., Yamazaki T., Sezutsu H. A Hox Gene, Antennapedia, Regulates Expression of Multiple Major Silk Protein Genes in the Silkworm Bombyx mori. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:7087–7096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.699819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saenko S.V., Marialva M.S., Beldade P. Involvement of the Conserved Hox Gene Antennapedia in the Development and Evolution of a Novel Trait. EvoDevo. 2011;2:9. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomoyasu Y., Wheeler S.R., Denell R.E. Ultrabithorax Is Required for Membranous Wing Identity in the Beetle Tribolium castaneum. Nature. 2005;433:643–647. doi: 10.1038/nature03272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomoyasu Y. Ultrabithorax and the Evolution of Insect Forewing/Hindwing Differentiation. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017;19:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun D., Guo Z., Liu Y., Zhang Y. Progress and Prospects of CRISPR/Cas Systems in Insects and Other Arthropods. Front. Physiol. 2017;8:608. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolter F., Schindele P., Puchta H. Plant Breeding at the Speed of Light: The Power of CRISPR/Cas to Generate Directed Genetic Diversity at Multiple Sites. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:176. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soyk S., Lemmon Z.H., Oved M., Fisher J., Liberatore K.L., Park S.J., Goren A., Jiang K., Ramos A., van der Knaap E., et al. Bypassing Negative Epistasis on Yield in Tomato Imposed by a Domestication Gene. Cell. 2017;169:1142–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mohamad Ishak N.S., Nong Q.D., Matsuura T., Kato Y., Watanabe H. Co-Option of the Bzip Transcription Factor Vrille as the Activator of Doublesex1 in Environmental Sex Determination of the Crustacean Daphnia magna. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qin J., Guo L., Ye F., Kang S., Sun D., Zhu L., Bai Y., Cheng Z., Xu L., Ouyang C., et al. MAPK-Activated Transcription Factor PxJun Suppresses Pxabcb1 Expression and Confers Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac Toxin in Plutella xylostella (L.) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021;87:e00466-21. doi: 10.1128/aem.00466-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu X., Lei Y., Yang Y., Baxter S.W., Li J., Wu Q., Wang S., Xie W., Guo Z., Fu W., et al. Construction and Characterisation of Near-Isogenic Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) Strains Resistant to Cry1Ac Toxin. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015;71:225–233. doi: 10.1002/ps.3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo Z., Kang S., Zhu X., Wu Q., Wang S., Xie W., Zhang Y. The Midgut Cadherin-Like Gene Is Not Associated with Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Toxin Cry1Ac in Plutella xylostella (L.) J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015;126:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo Z., Gong L., Kang S., Zhou J., Sun D., Qin J., Guo L., Zhu L., Bai Y., Bravo A., et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Cry1Ac Protoxin Activation Mediated by Midgut Proteases in Susceptible and Resistant Plutella xylostella (L.) Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020;163:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xie W., Lei Y., Fu W., Yang Z., Zhu X., Guo Z., Wu Q., Wang S., Xu B., Zhou X., et al. Tissue-Specific Transcriptome Profiling of Plutella xylostella Third Instar Larval Midgut. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012;8:1142–1155. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo Z., Kang S., Zhu X., Xia J., Wu Q., Wang S., Xie W., Zhang Y. The novel ABC Transporter ABCH1 Is a Potential Target for RNAi-Based Insect Pest Control and Resistance Management. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13728. doi: 10.1038/srep13728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.