Abstract

Site-specific incorporation of 2′-modifications and neutral linkages in the deoxynucleotide gap region of toxic phosphorothioate (PS) gapmer ASOs can enhance therapeutic index and safety. In this manuscript, we determined the effect of introducing 2′,5′-linked RNA in the deoxynucleotide gap region on toxicity and potency of PS ASOs. Our results demonstrate that incorporation of 2′,5′-linked RNA in the gap region dramatically improved hepatotoxicity profile of PS-ASOs without compromising potency and provide a novel alternate chemical approach for improving therapeutic index of ASO drugs.

Keywords: Antisense oligonucleotides; 2′,5′-RNA; Gap modification; Therapeutic index

RNA therapeutics is emerging as a third drug discovery platform, and chemical modifications were essential for making this technology a clinical success.1 Chemical modifications have been used to enhance RNA-binding and nuclease stability of RNA therapeutic drugs.2,3 In addition, site-specific chemical modifications have been utilized to improve therapeutic properties of antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) and siRNA therapeutics.4−7 At least four phosphorothioate (PS) gapmer ASOs have been approved for clinical use, and over 45 PS ASOs are are in development across numerous therapeutics areas.1 Our group recently reported that site-specific incorporation of 2′-modifications or neutral linkages in the deoxynucleotide gap region can enhance the therapeutic index of toxic PS gapmer ASOs bearing high affinity modifications such as cEt BNA and LNA.6 Toxic PS ASOs bind more proteins with higher affinity and cause nucleolar mislocalization of paraspeckle proteins such as P54nrb.6 We also reported that replacing DNA nucleotides with 2′-O-methyl at gap position 2 reduced protein-binding, decreased hepatotoxicity, and improved therapeutic index of ASOs.6

In this report, we investigated if replacing DNA nucleotides in the gap region with a hydrophilic modification such as RNA could also improve therapeutic index. Unfortunately, introducing even a single RNA nucleotide in the DNA gap region resulted in severe metabolic instability. To address this, we further examined if replacing RNA with 2′,5′-linked RNA could enhance metabolic stability while maintaining antisense activity. 2′,5′-Linked RNA is a structural analogue of RNA with potential roles in the prebiotic world8 and is capable of forming Watson–Crick base pairs with complementary RNA, albeit with slightly reduced thermal stability.9,10 Indeed, site-specific incorporation of one or more 2′,5′-RNA in siRNA is tolerated and shown to have similar properties as natural siRNA.11,12

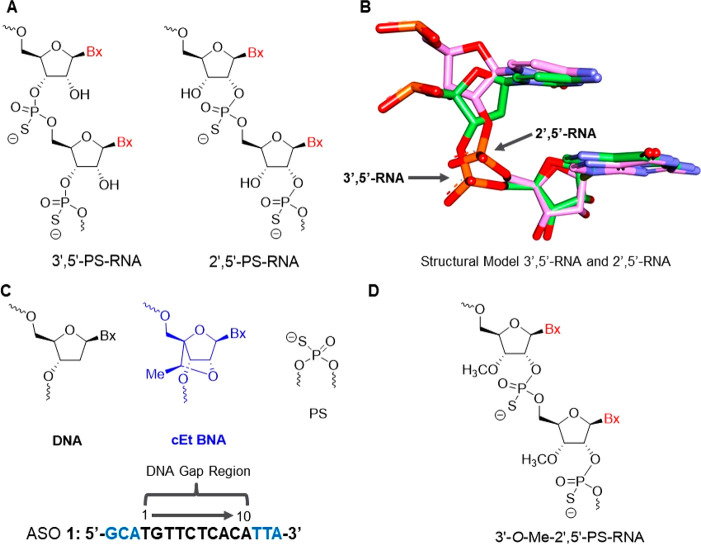

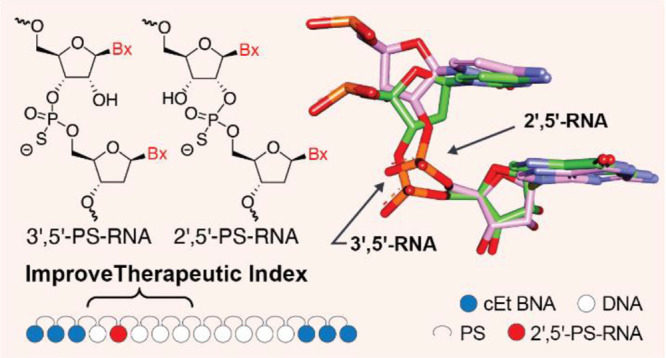

To test our hypothesis, we introduced 2′,5′-linked PS RNA and 3′-O-methyl-2′,5′ PS RNA, (Figure 1) in the gap region of a model toxic ASO 1 and determined the effect of these substitutions on potency and hepatotoxicity. We found that site-specific incorporation of a single 2′,5′-linked nucleotide did not disrupt base-pairing and could enhance the therapeutic profile of the modified ASOs when incorporated at positions 1–4 in the deoxynucleotide gap. The 2′,5′-linked modifications exhibited a broader positional preference as compared to the 2′-OMe gap modification strategy described previously.6 Additionally, the ASO containing 2′,5′-RNA at DNA gap position 2 showed potency similar to parent ASO highlighting the therapeutic potential of this class of nucleic acid analogues.

Figure 1.

(A). Structure of 3′,5′ and 2′,5′-PS-RNA. (B). Structural model of 3′,5′- and 2′,5′-RNA showing similar position of the nucleobases but different backbone geometries. (C). Chemical structure of CXCL12 cEt BNA18 gapmer ASO 1. (D). Structure of 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA

Effect of Site-specific Incorporation of RNA on ASO Activity and Toxicity in Cells and in Animals

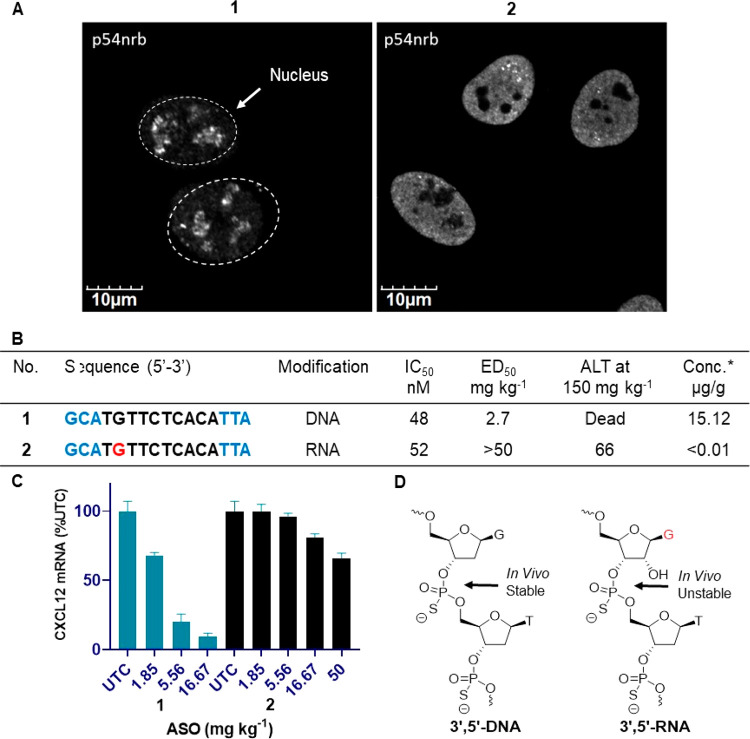

To understand the effect of introducing an RNA modification in the DNA gap region on the hepatotoxicity of a model toxic ASO 1, we synthesized variants of 1 where the 2′-deoxyguanosine monomer at positions 2 in the gap was replaced with guanosine (2, Figure 2). This position was chosen because our previous studies showed that modification at gap position 2 with 2′-O-methylguanosine can reduce ASO toxicity.6 We first evaluated the effect of replacing DNA with RNA nucleotide at gap position 2 (ASO 2) on the delocalization of p54nrb using scanning microscopy (2, Figure 2A).6 Upon transfection, ASO 2 attenuated nucleolar delocalization of p54nrb (Figure 2A). This data suggests that, like 2′-O-Me modification, RNA at gap position 2 can reduce binding of PS ASO to proteins implicated for toxicity.6 The modified ASO 2 was also evaluated in mouse 3T3 cells after delivery by electroporation where it exhibited comparable potency relative to the control ASO 1 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Effect of nucleolar delocalization of p54nrb in cells treated with ASO 1 and 2, immunofluorescent staining of p54nrb in HeLa cells 4 h after transfection with 60 nM ASOs 1 and 2, toxic PS-ASO 1 induced nuclear localization of p54nrb and RNase H1 to nucleoli, RNA modified ASO 2 reduced nuclear localization of p54nrb to nucleoli. (B−C) In vitro and in vivo potency, ALT (IU/L) of mice treated with 150 mg kg−1 and tissue concentration of ASO 1 and 2. *Concentration of ASOs 1−2 in livers of mice dosed at 16.7 mg kg−1 via subcutaneous injection. (D) Site of metabolic cleavage in 3′,5′-DNA and 3′,5′-RNA in mouse liver. ASOs 1−2 blue letters indicate cEt BNA, black letters indicate DNA and red indicates 2′,5′-PS-RNA nucleotides.

The ASOs 1 and 2 were next injected subcutaneously into mice at a dose of 150 mg/kg, and the animals were sacrificed 72 h after injection. Levels of plasma alanine transaminase (ALT) were measured as an indicator of hepatotoxicity. RNA modified ASO 2 showed complete ablation of hepatotoxicity relative to the parent ASO 1. Given the stronger effect on reducing toxicity observed with the RNA gap modification, we next investigated potency of ASO 2 relative to parent ASO 1 in mice. Mice were injected subcutaneously with increasing doses of the ASOs 1 and 2, and reductions of liver CXCL12 mRNA were quantified post sacrifice. As seen in Figure 2C, potency of ASO 2 was significantly lower than ASO 1. Interestingly, analysis of liver samples from mice treated with 16.7 mg kg–1 of ASOs 1 and 2 revealed no detectable level of ASO 2 (Figure 2B). It is well-known that PS RNA is metabolically less stable than PS DNA.13,14 It is conceivable that comparable activity of ASO 1 and 2 in cell culture but significantly reduced potency and lower accumulation of ASO 2 in the liver may be a result of reduced metabolic stability of RNA modified ASO 2 in mice. To address this, we hypothesized that replacing RNA with 2′,5′-PS-RNA in the gap region will enhance metabolic stability while maintaining activity and improving therapeutic index.

Effect of Site-specific Incorporation of 2′,5′-RNA on ASO Activity and Toxicity in Cells and in Animals

The 2′,5′-backbone linkage is an isomer of natural 3′,5′-backbone in RNA (Figure 1A). Recent high resolution crystallographic data on 3′,5′- and 2′,5′-mixed-backbone RNA duplexes showed that RNA duplexes can accommodate perturbation caused by 2′,5′-linkages and share the same global A-like structure of 3′,5′-RNA duplexes (Figure 1B).15 Thus, we hypothesized that 2′,5′-PS-RNA when placed in the gap region of ASOs could alter local structure and modulate interactions of PS-ASOs with important cellular proteins implicated in toxicity.

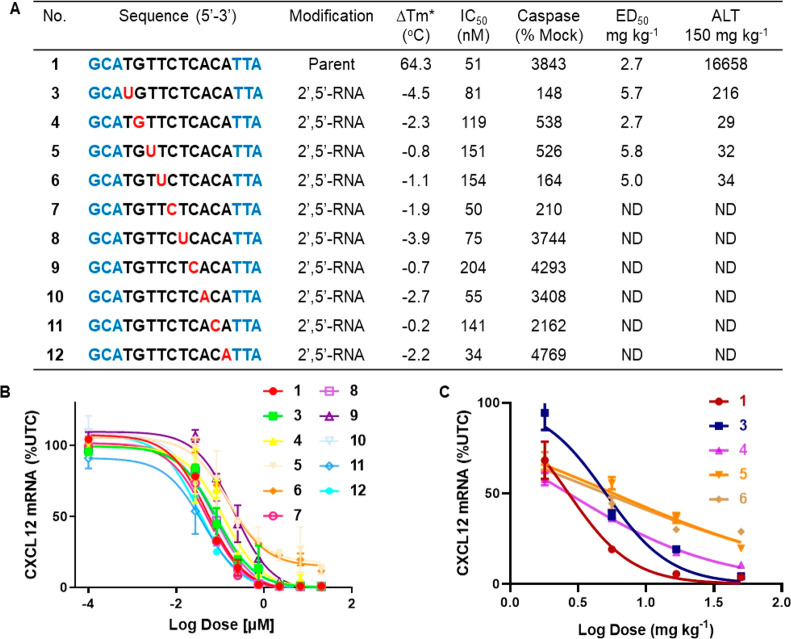

We investigated the effect of 2′,5′-backbone RNA (Figure 1A) on toxicity and potency when placed in the DNA gap region of the toxic PS ASO 1. The 2′,5′-nucleotides were incorporated in the deoxynucleotide gap region in a site-specific manner (3–12, Figure 3A) using standard automated solid-phase DNA synthesis chemistry,4 and the resulting ASOs were evaluated in duplex thermal stability measurements for RNA-binding affinity and in cells for effects on antisense activity and cytotoxicity (Figure 3A,B). Incorporation of a single 2′,5′-RNA nucleotide in the gap resulted in varying changes in duplex thermal stability (Tm) depending on the position with maximum reduction (−4.5 °C/mod) at position 2 and minimum reduction at position 9 (−0.2 °C/mod) relative to the control ASO (Figure 3A). The modified ASOs 3–12 were also evaluated for antisense activity in mouse 3T3 cells, where all of them exhibited comparable activity (within 2–4-fold IC50) as the parent ASO (Figure 3A). Toxic ASOs show activation of caspase activity indicative of cytotoxicity.6 Interestingly, introducing 2′,5′-PS-RNA at gap positions 1–5 dramatically reduced cytotoxicity in cells relative to parent ASO 1 (Figure 3A). However, positioning 2′,5′-PS-RNA at gap positions 6–10 did not reduce caspase activation relative to parent ASO 1. These results are consistent with our previous observation that the 5′-portion of the DNA gap region is sensitive to protein binding and chemical modification.6

Figure 3.

(A,B) 2′,5′-PS-RNA modification was walked in the gap region (3–12) and the effect on duplex stability versus complementary RNA (Tm), potency (IC50) in NIH3T3 cells, and cytotoxicity as measured by caspase activation in Hepa1–6 cells, and characterization of hepatotoxicity of ASOs 3–6 as measured by increase in plasma ALT (IU/L). (C) Characterizing the effect of 2′,5′-PS-RNA modification at positions 1–4 (3–6) in the DNA gap on potency as determined by the dose required to reduce CXCL12 mRNA by 50% in the livers relative to untreated control animal (ED50). ASOs 1 and 3–12. Blue letters indicate cEt BNA, black indicates DNA, and red indicates 2′,5′-PS-RNA nucleotides. ND = not done. *ΔTm relative to parent ASO 1.

To determine if the reduced cytotoxicity observed in cells translates to animals, mice were injected with 150 mg/kg of ASOs 3–6 (Figure 4A), and the animals were sacrificed 72 h after injection. Levels of plasma alanine transaminase (ALT) were measured as an indicator of hepatotoxicity. All ASOs modified with 2′,5′-PS-RNA 3–6 (Figure 4A) showed reductions in hepatotoxicity relative to the parent ASO 1 (Figure 4A). The level of reduction was higher for ASOs 4–6 compared to ASO 3. The ASOs were also evaluated for potency to reduce CXCL12 mRNA in the liver. Mice were injected with 1.8, 5.6, 16.7, and 50 mg kg–1 of 2′,5′-PS-RNA ASOs 1, 3–6 and sacrificed 72 h after injection. Livers were harvested, and the dose required to reduce CXCL12 mRNA by 50% in the liver was determined. ASOs 3, 5, and 6 showed 2-fold reduced potency relative to the control ASO 1. Interestingly, ASO 4 with a 2′,5′-PS-RNA modification at gap position 2 showed similar potency relative to parent ASO 1. Taken together, these results suggest that replacing 3′,5′-DNA PS with a 2′,5′-RNA PS-linkages at position 2 can enhance ASO safety without reducing potency. Our observation that 2′,5′-PS-RNA can reduce the toxicity of the modified ASOs when incorporated at positions 1–4 in the deoxynucleotide gap region suggests that these modifications have a broader positional preference as compared to the 2′-O-Me gap modification strategy, in which gap position 2 and, to a lesser extent, position 3 are sensitive to 2′-O-Me modification.6 However, we have also shown that introducing alkyl phosphonate linkages at positions 2 or 3, and 5′-alkyl DNA modifications at positions 3 and 4, can also reduce hepatotoxicity,4,16 suggesting a modification specific foot-print near the 5′-end of the DNA gap can be utilized to enhance therapeutic index.

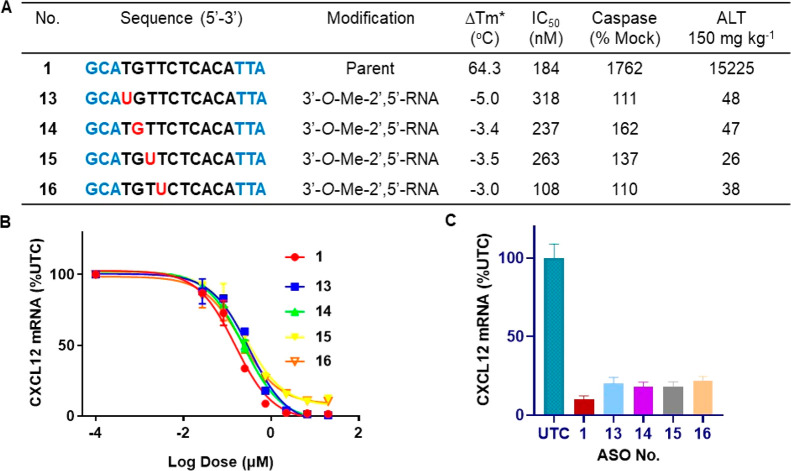

Figure 4.

(A−B) 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA modification was walked in the gap region (13−16) and the effect on duplex stability versus complementary RNA (Tm), potency (IC50) in NIH3T3 cells, and cytotoxicity as measured by caspase activation in Hepa1-6 cells, and characterization of hepatotoxicity of ASOs 13−16 as measured by increase in plasma ALT (IU/L). (C) Effect of 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA in the DNA gap position 1−4 (ASOs 13−16) on activity in the livers of mouse dosed 17 mg kg−1 of ASOs once via subcutaneous injection. ASOs 1, 13−16 blue letters indicate cEt, BNA, black letters indicate DNA and red indicates 3′-O-Me-2′,5′- PS-RNA nucleotides. *ΔTm relative to parent ASO 1.

Effect of Site-Specific Incorporation of 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA on ASO Activity and Toxicity in Cells and in Animals

We next explored the effect of introducing 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA nucleotides in the DNA gap region on potency and toxicity. In this modification, the hydroxyl-group is protected and, as a result, is chemically more stable and easier to synthesize than RNA. We synthesized ASOs 13–16 (Figure 4A) containing 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA (Figure 1) at positions 1–4 in the gap region of toxic ASO 1. The 3′-O-methylribonucleoside-2′-phosphoramidites were synthesized using reported methods.17 Synthesis of ASOs 13–16 (Figure 4A) were accomplished using standard automated solid-phase DNA synthesis chemistry.4Tm of ASOs 13–16 duplexed with complementary RNA were determined and we found that single 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA incorporation in the deoxynucleotide gap region showed similar reduction (−3 to −5 °C/mod, Figure 4A) in thermal stability as compared to 2′,5′-RNA. The activity of modified ASO 13–16 were evaluated in mouse 3T3 cells, and all of them exhibited comparable activity (within 2-fold IC50) relative to the parent ASO 1 (Figure 4A,B). To evaluate the effect of 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA modification on the cytotoxicity of ASO, we evaluated caspase activation of modified ASOs 13–16 and compared to parent toxic ASO 1. Consistent, with other 2′,5′-linked nucleotides studied in this report, placing a single 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA modification in the deoxynucleotide gap region significantly reduced caspase activation in cells relative to parent ASO 1 (Figure 4A). This data further suggests that introducing even a single 2′,5′-linkage in the deoxynucleotide gap region reduces cytotoxicity.

We next evaluated the effect of 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA modification on hepatotoxicity in mice. Animals were injected with 150 mg/kg of the CXCL12 ASOs 13–16 (Figure 4A) and sacrificed 72 h after injection, and levels of ALT were measured as an indicator of hepatotoxicity. ASOs modified with 3′-O-Me-2′,5′-PS-RNA modification (13–16, Figure 4A) showed reductions in ALT level relative to the parent ASO 1 (Figure 4A). Further, we evaluated the activity of ASOs 13–16 in mice. Mice were injected with 16.7 mg kg–1 ASOs 1 and 13–16 once, and animals were sacrificed after 72 h of injection. Livers were harvested, and the inhibition of CXCL12 mRNA expression was determined by q-RTPCR. All ASOs inhibited expression of CXCL12 mRNA and parent ASO 1 showed slightly higher inhibition (Figure 4C).

In conclusion, we demonstrate that site-specific incorporation of 2′,5′-linked RNA in the gap region enhances the therapeutic profile of toxic PS ASOs. 2′,5′-PS-RNA can enhance the therapeutic profile of the modified ASOs when incorporated at positions 1–4 in the deoxynucleotide gap, suggesting that these modifications have a different positional preference as compared to the 2′-O-Me gap modification strategy described previously.6 Additionally, the ASO containing 2′,5′-PS-RNA at DNA gap position 2 showed potency similar to parent ASO highlighting the therapeutic potential of this class of nucleic acid analogues. The work presented in this report adds to the growing body of evidence that small structural changes in the gap region of ASO can mitigate hepatotoxicity without affecting potency. This work ushers a new chemical optimization approach with a focus on improving the therapeutic profile of nucleic acid-based therapeutics.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- cEt

constrained ethyl

- BNA

bridged nucleic acid

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00072.

Methods for the synthesis of ASOs 1–16, analytical data for compounds 1–16, methods for determining Tm, for cell culture, and for animal experiments (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Crooke S. T.; Witztum J. L.; Bennett C. F.; Baker B. F. RNA-Targeted Therapeutics. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 714–739. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli M.; Manoharan M. Re-Engineering RNA Molecules into Therapeutic Agents. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1036–1047. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W. B.; Seth P. P. The Medicinal Chemistry of Therapeutic Oligonucleotides. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9645–9667. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migawa M. T; Shen W.; Wan W B.; Vasquez G.; Oestergaard M. E; Low A.; De Hoyos C. L; Gupta R.; Murray S.; Tanowitz M.; Bell M.; Nichols J. G; Gaus H.; Liang X.-h.; Swayze E. E; Crooke S. T; Seth P. P Site-specific replacement of phosphorothioate with alkyl phosphonate linkages enhances the therapeutic profile of gapmer ASOs by modulating interactions with cellular proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5465–5479. 10.1093/nar/gkz247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel M. K.; Foster D. J.; Kel’in A. V.; Zlatev I.; Bisbe A.; Jayaraman M.; Lackey J. G.; Rajeev K. G.; Charisse K.; Harp J.; Pallan P. S.; Maier M. A.; Egli M.; Manoharan M. Chirality Dependent Potency Enhancement and Structural Impact of Glycol Nucleic Acid Modification on siRNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8537–8546. 10.1021/jacs.7b02694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W.; De Hoyos C. L.; Migawa M. T.; Vickers T. A.; Sun H.; Low A.; Bell T. A. 3rd; Rahdar M.; Mukhopadhyay S.; Hart C. E.; Bell M.; Riney S.; Murray S. F.; Greenlee S.; Crooke R. M.; Liang X.-H.; Seth P. P.; Crooke S. T. Chemical modification of PS-ASO therapeutics reduces cellular protein-binding and improves the therapeutic index. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 640–650. 10.1038/s41587-019-0106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W. B.; Migawa M. T.; Vasquez G.; Murray H. M.; Nichols J. G.; Gaus H.; Berdeja A.; Lee S.; Hart C. E.; Lima W. F.; Swayze E. E.; Seth P. P. Synthesis, biophysical properties and biological activity of second generation antisense oligonucleotides containing chiral phosphorothioate linkages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 13456–13468. 10.1093/nar/gku1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher D. A.; McHale A. H. Nonenzymic joining of oligoadenylates on a polyuridylic acid template. Science 1976, 192, 53–54. 10.1126/science.1257755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannaris P. A.; Damha M. J. (1993) Oligoribonucleotides containing 2’,5′-phosphodiester linkages exhibit binding selectivity for 3′,5′-RNA over 3′,5′-ssDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 4742–4749. 10.1093/nar/21.20.4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasner M.; Arion D.; Borkow G.; Noronha A.; Uddin A. H.; Parniak M. A.; Damha M. J. (1998) Physicochemical and Biochemical Properties of 2’,5′-Linked RNA and 2’,5′-RNA:3′,5′-RNA ″Hybrid″ Duplexes. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 7478–7486. 10.1021/bi980160b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash T. P.; Kraynack B.; Baker B. F.; Swayze E. E.; Bhat B. (2006) RNA interference by 2’,5′-linked nucleic acid duplexes in mammalian cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3238–3240. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibian M.; Harikrishna S.; Fakhoury J.; Barton M.; Ageely E. A.; Cencic R.; Fakih H. H.; Katolik A.; Takahashi M.; Rossi J.; Pelletier J.; Gagnon K. T.; Pradeepkumar P. I.; Damha Masad J. Effect of 2’-5′/3′-5′ phosphodiester linkage heterogeneity on RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 4643–4657. 10.1093/nar/gkaa222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima W. F.; Prakash T. P.; Murray H. M.; Kinberger G. A.; Li W.; Chappell A. E.; Li C. S.; Murray S. F.; Gaus H.; Seth P. P.; Swayze E. E.; Crooke S. T. Single-Stranded siRNAs Activate RNAi in Animals. Cell 2012, 150, 883–894. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M. J.; Crooke S. T.; Monteith D. K.; Cooper S. R.; Lemonidis K. M.; Stecker K. K.; Martin M. J.; Crooke R. M. In vivo distribution and metabolism of a phosphorothioate oligonucleotide within rat liver after intravenous administration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 286, 447–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J.; Li L.; Engelhart A. E.; Gan J.; Wang J.; Szostak J. W. Structural insights into the effects of 2’-5′ linkages on the RNA duplex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 3050–3055. 10.1073/pnas.1317799111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez G.; Freestone G. C.; Wan W. B.; Low A.; De Hoyos C. L.; Yu J.; Prakash T. P.; Ǿstergaard M. E.; Liang X.-H.; Crooke S. T.; Swayze E. E.; Migawa M. T.; Seth P. P. Site-specific incorporation of 5′-methyl DNA enhances the therapeutic profile of gapmer ASOs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 1828–1839. 10.1093/nar/gkab047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. C.; Roy S. K. U.S. Patent US5214135A, 1993.

- Seth P. P.; Siwkowski A.; Allerson C. R.; Vasquez G.; Lee S.; Prakash T. P.; Wancewicz E. V.; Witchell D.; Swayze E. E. (2009) Short antisense oligonucleotides with novel 2’-4’ conformationaly restricted nucleoside analogues show improved potency without increased toxicity in animals. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 10–13. 10.1021/jm801294h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.