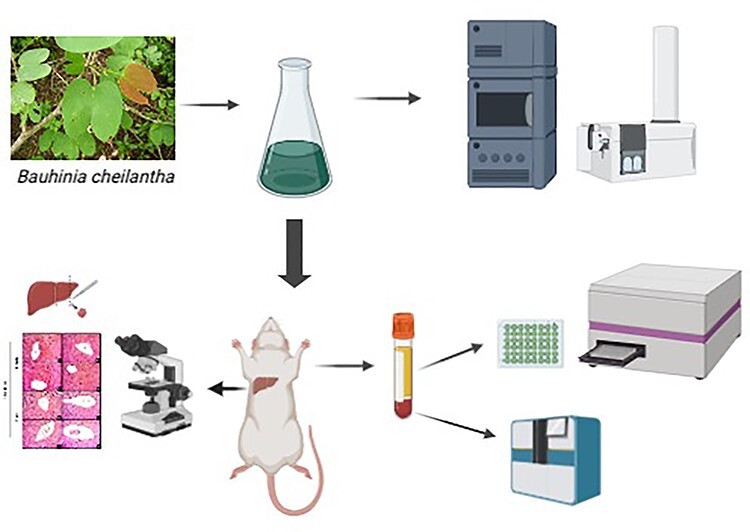

Graphical abstract

Keywords: quercitin, afzelin, acute toxicity, sub-acute toxicity, Bauhinia cheilantha

Abstract

Bauhinia cheilantha (Fabaceae), known popularly as pata-de-vaca and mororó has been largely recommended treating several diseases in folk medicine. However, information on safe doses and use is still scarce. The goal was to evaluate in-vitro antioxidant and antihemolytic and also acute and sub-acute toxicity effects of hydroalcoholic extract from B. cheilantha leaves (HaEBcl). The identification of the compounds in the HaEBcl was performed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with a diode array detector and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Antioxidant and hemolytic activity of HaEBcl was evaluated in vitro. To study acute toxicity, female mice received HaEBcl in a single dose of 300 and 2.000 mg/kg. Later, sub-acute toxicity was introduced in both female and male mice by oral gavage at 300, 1000, or 2000 mg/kg for 28 consecutive days. Hematological and biochemical profiles were created from the blood as well as from histological analysis of the liver. HaEBcl is rich in flavonoids (quercitrin and afzelin), has no hemolytic effects and moderate antioxidant effects in vitro. Acute toxicity evaluation showed that lethal dose (LD50) of HaEBcl was over 2000 mg/kg. Sub-acute toxicity testing elicited no clinical signs of toxicity, morbidity, or mortality. The hematological and biochemical parameters discounted any chance of hepatic or kidney toxicity. Furthermore, histopathological data did not reveal any disturbance in liver morphology in treated mice. Results indicate that HaEBcl has no hemolytic and moderate antioxidant effects in vitro. In addition, HaEBcl dosage levels up to 2000 mg/kg are nontoxic and can be considered safe for mammals.

Introduction

The genus Bauhinia (Fabaceae, Leguminoseae) is composed of large and diversified pantropical plants with ~300–350 species, which are known as cow’s paw or cow’s hoof, because of the shape of their leaves [1, 2]. Traditionally, this genus has been used in folk medicine as a remedy for different kinds of diseases, mainly diabetes, pain in general, inflammation, and infections [2, 3].

Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. is a shrub or small tree with simple and alternate, leaves split at the apex up to the middle (similar to cow’s foot). It is native to the Caatinga (seasonal dry forest), a specific Brazilian biome, where it grows mainly on stony soils, poor in nutrients, in open formations, and at high altitudes [1]. The areal parts and stem-bark are used in folk medicine in many communities living in the semiarid region of Northeastern Brazil [2]. Some are used to treat diabetes, influenza, pain in general, diabetes, intestinal, stomach, and renal problems, as well as a in decoction, alcoholic infusion, aqueous infusion, poultice, or juice [2, 4]. In addition, B. cheilantha has economic and nutritional importance [1]. Bauhinia cheilantha seeds have a high protein content (~36%), reasonable essential amino acids profile, and low levels of antinutritional compounds [4]. For is reason, this species is widely used for different proposes in local communities in the semiarid region.

However, the general perception that plants, because of their nutritional, medicinal, and economic importance, are absent from adverse effects is not only false, but also dangerous. Plants produce bioactive compounds known as secondary metabolites, which play an essential role in defending the plants from biotic and abiotic stress conditions [5]. Even though these molecules can be used for biopharmaceutical purposes, some of them may lead to toxicity, or even death, in both humans and animals [5, 6]. For example, pyrrolizidine alkaloids are naturally occurring toxins produced by over 6000 plant species whose toxicity is largely documented [7]. Other alkaloids include tropane alkaloids such as atropine and scopolamine, and hyoscyamine, which are used as anticholinergics in Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs and homeopathic remedies [8]. This molecule may be very dangerous at high doses. Various plants can cause toxic effects when ingested. For example, progressive interstitial nephritis leading to end stage of renal disease and urothelial malignancy in users of Aristolochia fangchi [9] has been documented. Atropa belladonna, popularly known as belladonna or deadly nightshade, ranks among one of the most poisonous plants in Europe and other parts of the world. Thus, it is mandatory to trace the toxicological profile of popularly-used herbal medicines.

The aim of this study was to provide scientific data on the safe use of B. cheilantha, focusing on its in-vitro antihemolytic and antioxidant activity and also acute and sub-acute toxicities through the evaluation of behavioral, biochemical, hematological, and histological parameters of the hydroalcoholic extract from B. cheilantha leaves (HaEBcl).

Materials and Methods

Plant material and preparation of extract

Bauhinia cheilantha leaves were collected in March 2019 in the town of Altinho, (8°35′13,5″ S; 36°5′34,6″ W), in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil, and identified by Dr. Ulysses Paulino de Albuquerque (UFPE). A voucher specimen (PEUFR 48 653, 46 183) has been deposited at the Herbarium of the Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE).

The hydroalcoholic extract of B. cheilantha leaves (HaEBcl) was prepared by maceration from dried and powdered leaves (100 g) in 100 ml of ethanol 80% at room temperature (28°C) overnight. The solvent from HaEBcl was filtered and concentrated using a rotary evaporator to provide an aqueous ethanolic extract After preparation, the dried powder extract was stored at room temperature. The HaEBcl extract was used for preliminary phytochemical analysis and toxicological assays.

Phytochemical analysis

Determination of total phenolic content

The total phenolic content of the samples was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteau reagent according to the method of Slinkard and Singleton [10] modified using gallic acid as a standard phenolic compound. Initially, the samples were solubilized in ethanol at concentrations of 1.0 mg/ml. A 50-μl aliquot of each solution was transferred to an Eppendorf tube with 20 μl of the Folin–Ciocalteau reagent and 870 μl of distilled water was added and stirred for 1 min. Then, 60 μl of the Na2CO3 solution (15%) was added to the mixture and stirred for 30 s, resulting in a final concentration of 100 μg/ml for the samples. Absorbance was measured at 760 nm on a spectrophotometer. The total amount of phenolic compounds was determined in equivalent micrograms of gallic acid, using the equation obtained in the standard gallic acid graph.

Total flavonoid content

The determination of flavonoids followed the methodology proposed by Woisky and Salatino [11] with modifications, using quercetin as the standard. Initially, ethanol solutions (1.0 mg/ml) of the Bauhinia extract were prepared. For the test, 50 μl of sample (final concentration 50 μg/ml) and 500 μl of 5% aluminum chloride solution (AlCl3) were placed in an Eppendorf tube and the volume was made up to 1000 μl with methanol. After 30 min, the absorbance was measured using an Elisa UV–Vis spectrophotometer at 425 nm, using 96-well plates. The analyses were performed in triplicate. The content of total flavonoids was determined by interpolating the sample absorbance against a calibration curve constructed with quercetin standard solutions in various concentrations (2.5–20 μg/ml) and expressed as an equivalent milligram. Quercetin per gram of extract (mg EQ/g), considering the standard deviation (SD).

The phytochemical analysis was obtained in negative electrospray mode using an XEVO-G2XSQTOF mass spectrometer (Waters, Manchester, UK) connected to an ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters, Milford®, MA, USA). The analytical detector was a Waters Acquity PDA detector, which was set to a wavelength range of 200–400 nm. The conditions for obtaining the data by UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS/MS were set according to Cabrera et al. [12].

The antioxidant activity of HaEBcl

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity assay

The radical scavenging activity of HaEBcl was performed against the free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) following the methodology of Silva et al. [13]. Stock solution was prepared from the extracts and ethanol fraction in different concentrations (0.10–5.0 mg/ml). Through preliminary analysis, appropriate quantities of stock solutions of the samples and 450 μl of the solution of DPPH˙ (23.6 mg/ml in ethanol, EtOH) were transferred to 0.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and the volume was completed with EtOH, following homogenization. Samples were sonicated for 30 min and placed in a 96-well plate to record the amount of DPPH˙ on a UV–Vis (Biochrom EZ Read 2000®) device at a wavelength of 517 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control and all concentrations were tested in triplicate. The percentage scavenging activity (% SA) was calculated from the equation:

|

where Abscontrol is the absorbance of the control containing only the ethanol solution of DPPH, and Abssample is the absorbance of the radical in the presence of the sample or standard ascorbic acid.

2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS˙+) scavenging activity assay

The 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS˙+) radical scavenging of HaEBcl was carried out following the methodology described by Re et al. [14], in a UV–Vis (Biochrom EZ Read 2000®) device, using Trolox as the standard compound. The starting concentrations of the solutions of the samples were 0.1–1.0 mg/ml, with the addition of 450 μl of the radical ABTS˙+ solution to give final concentrations of 2.5–100.0 μg/ml samples. Samples were protected from light and sonicated for 6 min. Absorbance of the samples and the positive control were measured at a wavelength of 734 nm using a microplate of 96 wells. Each concentration was tested in triplicate. The percentage of free radical scavenging activity of ABTS˙+ was calculated by the equation:

|

where Abscontrol is the absorbance of the control containing only the ethanol solution of ABTS˙+ and Abssample is the absorbance of the radical in the presence of the sample or standard ascorbic acid.

The antiradical efficiency was established using linear regression analysis and the 95% confidence interval (CI; P < 0.05) obtained using the statistical program GraphPad Prism 5.0®. The results were expressed through the value of the half maximal effective concentration (EC50), which represents the concentration of the sample necessary to sequester 50% of the radicals.

In vitro hemolytic assay

The evaluation of the osmotic fragility of red blood cells (RBC) was performed on a fresh blood sample collected from a healthy rat, using dethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as anticoagulant [15]. The blood sample was carefully mixed with 0.90% NaCl solution and the mixture was centrifuged (1500 rpm, 15 min). The supernatant was discarded and this procedure was repeated. The concentrate of RBC (5 ml) was added to 1.0 ml of plant extract in different concentrations (corresponding to 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 mg of plant/ml in 0.9% NaCl solution) and incubated for 60 min at room temperature, with two repetitions for each concentration. Extracts were also prepared of 200 mg/ml containing different concentrations of NaCl (0 up to 0.9%) and incubated with blood samples. The hemolytic percentage was determined by measurement of hemoglobin in the supernatants using a commercial kit (BioClin®, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil) and a spectrophotometer at 540 nm. The experiments were analyzed with paired t-test to verify potential differences between hypotonic and isotonic phases (% concentrations of NaCl) versus relative hemolysis (% hemolysis). The hemolysis rate was calculated as follows:

|

Experimental animals and ethical statement

Adult female and male Swiss albino mice (35 ± 3 g, aged 8–10 weeks) were obtained from Animal House of the Physiology and Pharmacology Department at Federal University of Pernambuco. Mice were housed with a 12/12 light–dark cycle, 22 ± 3°C with free access to water and conventional lab chow diet (Purina, Labina®, Brazil). All experiments were performed between 8:00 and 10:00 am. The protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Pernambuco (CEUA-UFPE, process #: 23076.004793/2015-42) and conducted in accordance with Guide for the Care and Use Laboratory Animal published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Acute oral toxicity

The acute toxicity test was performed according to Guideline 423 (acute toxic class method) of the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for testing chemicals for acute oral toxicity [16]. After 5 days of acclimation in a propylene cage, nulliparous and non-pregnant female mice (three for each group) were fasted for 3 h and weighed before extract administration. The HaEBcl was dissolved in saline 0.9% and administered by gavage in mice in single dose using animal feeding needles (100 μl/100 g b.w.). Animals were randomly divided into three groups with three animals each: (i) treated with saline 0.9% (Control); (ii) treated with 300 mg/kg of HaEBcl (HaEBcl300); and (iii) treated with 2000 mg/kg of HaEBcl (HaEBcl2000).

In the first 4 h, all animals were closely observed for piloerection, changes in skin, fur and eyes, toxic effects on the mucous membrane, behavior pattern disorientation, hypoactivity, hyperventilation, asthenia, lethargy, sleep, diarrhea, tremors, salivation, convulsion, coma, motor activity, or death. After this, the animals were continuously observed every 24-h daily during 14 days. Parameters such as body weight, food and water intake were monitored daily. On the 14th day, female mice were euthanized by injection of a xylazine (80 mg/kg, i.p.) and ketamine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) solution, and the blood and organs were drawn for biochemical and macroscopic analysis. Based on mortality in each group, the LD50 was estimated [17].

Sub-acute oral toxicity test

The sub-acute toxicity test was conducted according to the Guideline 407 (repeated dose 28-day oral toxicity study in rodent) of the OECD to test chemicals for acute oral toxicity [18]. After 5 days of acclimation in propylene cages, male and nulliparous and non-pregnant female mice were fasted for 3 h and weighed before extract administration. The mice were divided into groups of 10, 5 male and 5 female each, to be treated daily over 28 consecutive days by gavage using animal feeding needles (100 μl/100 g b.w.) The groups were as follows: (i) treated with saline 0.9% (Control); (ii) treated with 300 mg/kg of HaEBcl (HaEBcl300); (iii) treated with 1000 mg/kg of HaEBcl (HaEBcl1000); and (iv) treated with 2000 mg/kg of HaEBcl (HaEBcl2000).

Animals were weighed weekly and observed for behavioral changes, food and water intake, and general morphological aspect. At the end of the treatment, all animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of ketamine and xylazine mixture (80 mg and 10 mg/kg, respectively), and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Blood samples were collected for biochemical and hematological analysis and the organs were weighed and stored for histopathology (liver).

Biochemical and hematological analysis

Blood collecting

On the 14th and 28th days after treatment, fasted mice rats were anesthetized as described previously; blood was drawn by the retro-orbital technique with or without heparin for both hematological and serum biochemical analysis.

Hematological analysis

On the 14th and 28th days, hematological parameters included RBC, hemoglobin concentration (HBG), hematocrit (HCT), red cell volume distribution (RDW), platelet count (PLT), mean platelet volume (MPV), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), lymphocytes (LYM), and white blood cells (WBC). These were determined by an automatic hematology analyzer (SDH-20, Labtest®, Brazil).

Serum biochemistry

The serum levels of alanine (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin, total protein (TP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine (CRE) were measured with kits from Labtest® in accordance with manufacture’s protocol.

Organ mass and histopathological analysis

On the 14th and 28th days, all mice were necropsied after blood collection for anatomical localization and gross examination of visible changes in the organs (aspect, color, and size). Selected organs including lungs, heart, liver, kidney, testicles, uterus, ovaries, spleen, adipose tissue, stomach, soleus, and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle. Were carefully excised and trimmed of fat and connective tissue before being weighed. The organ weight values were normalized by tibia length. On the 14th and 28th day of treatment, the specimens of liver were fixed in 10% formalin buffer solution for 24 h at room temperature and washed for 4 h with tap water. They were then dehydrated step-wise using 70–100% EtOH. Dehydrated tissues were made transparent through addition of xylene. Tissues were added to pre-heated paraffin for sufficient infiltration, then cooled, and formed into paraffin blocks before being cut into 5-μm sections using a microtome (Leica® RM 2025, Heidelberger, Germany). The paraffin was removed and specimens were dehydrated and stained with hematoxylin–eosin for observation with an inverted optical microscope (Leica®, Heidelberger, Germany) coupled to a video camera (Leica® DFC 280, Wetzlar, Germany) and a computer monitor. The specimens of liver were photographed and analyzed by an experienced pathologist for any cellular damage or change in morphology.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni test was employed to analyze the data between treated groups and their respective control groups. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Phytochemical analysis

Total phenols and flavonoids content

The results showed no statistically significant difference (Table 1) between total phenols and flavonoids content, which may suggest that the phenolic compounds found in the B. cheilantha extract are of the flavonoid type, similar to quercetin.

Table 1.

Total content of phenols and flavonoids in the hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves

| Phenolic content (mg EGA/g sample) | Flavonoid content (mg EQ/g sample) |

|---|---|

| 184.10 ± 7.54 | 202.39 ± 4.43 |

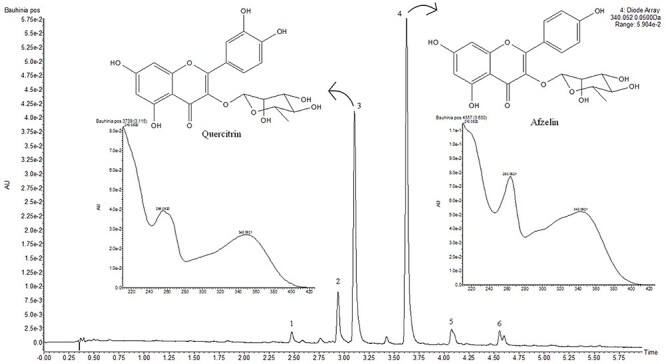

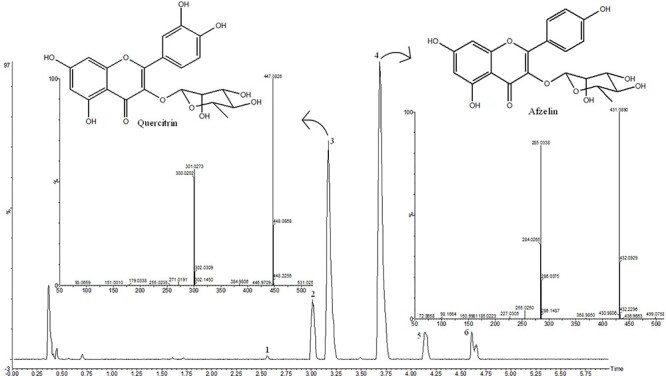

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography

The hydroalcoholic extract from B. cheilantha was analyzed by ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode array detection and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry for the profiling and structural characterization of the compounds. The UPLC-diode array detector (DAD) chromatograms at 340 nm and base peak ion (BPI) chromatograms of extract are presented in Figs 1 and 2, respectively. The compounds were identified based on their characteristic UV–Vis spectra peaks and mass detection as well as the accurate mass measurement of the precursor and product ions. All the compounds detected are listed on Table 2. The principal compounds 3 (quercitrin) and 4 (afzelin) were compared with standard samples (Figs 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Chromatogram of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves analyzed by UPLC-DAD.

Figure 2.

ESI BPI chromatogram of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves analyzed by UPLC-qTOF-MS.

Table 2.

Characterization of compounds from hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves by UPLC/qTOF-MSE

| Compound | RT (min) | UV λmax (nm) | [M−H]− (m/z) experimental | [M−H]− (m/z) calculated | MS/MS | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.55 | 349 | 463.0818 | 463.0882 | 301.0218 [M−H−hexose]− | Quercetin hexoside |

| 2 | 3.01 | 352 | 433.0710 | 433.0776 | 301.0281 [M−H−pentose]−, 300.0197 [M−2H−pentose]−, 271.0391 [M−2H–CO–pentose]− | Quercetin pentoside |

| 3 | 3.17 | 255, 349 | 447.0983 | 447.0932 | 301.0277 [M−H−rhamnose]−, 300.0207 [M−2H–rhamnose]−, 271.0187 [M−2H–CO–rhamnose]− | Quercitrin* |

| 4 | 3.68 | 263, 344 | 431.0914 | 431.0983 | 285.0342 [M−H–rhamnose]−, 284.0269 [M−2H–rhamnose]−, 255.0257 [M−2H–CO–rhamnose]− | Afzelin* |

| 5 | 4.14 | 348 | 599.1011 | 599.1042 | 445.1307 [M−2H–galloyl]−, 301.0291 [M−2H–galloyl–rhamnose]− | Quercetin-galloyl-rhamnoside |

| 6 | 4.61 | 265, 347 | 583.1001 | 583.1093 | 285.0348 [M−2H–galloyl–rhamnose]− | Kaempferol–galloyl–rhamoside |

Four compounds were identified as quercetin glycosides (1, 2, 3, and 5) and two were identified as glycosides of kaempferol (4 and 6). Observation of glycosidic residues pentoside (136 Da), rhamnosyl (146 Da), and glucosyl (162 Da) were cleaved sequentially and generated characteristic aglycone fragments compared with the available literature. Peaks 3 and 4 were compared with the standard and identified as quecitrin and afzelin, respectively. The mass spectra are shown in Fig. 2. Compounds 1 and 2 were identified as quercetin hexoside, m/z 463.0818 and quercetin–pentoside m/z 433.0710 [M−H]− with specific fragmentation at m/z 301.0218 [M−H−hexose]− and m/z 301.0281 [M−H−pentose]−, corresponding to radical loss from deprotonated molecules, respectively. Compounds 5 and 6 at m/z 599.1011 [M−H]− and 583.1001 [M−H]− were identified as quercetin and kaempferol galloyl rhamnosides, respectively. The main fragmentation at m/z 301.0291 and m/z 285.0348 resulted from the loss of a galloyl-rhamnoside moiety.

Antioxidant activity of HaEBcl

As shown in Table 3, the radical scavenging activity of the HaEBcl was performed using the radical scavenging abilities of DPPH and ABTS. The HaEBcl was able to inhibit the activity of DPPH radicals (EC50 = 409.5 μg/ml) and also perform an antioxidant activity for ABTS (EC50 = 104 μg/ml).

Table 3.

Determination of antioxidant activity according to EC50 (μg/ml) values of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves, ascorbic acid and TROLOX samples by DPPH and ABST methods

| Sample | DPPH | ABTS |

|---|---|---|

| EC 50 μg/ml (CI) | EC 50 μg/ml (CI) | |

| HaEBcl | 409.5 (401.4–420.6) | 104.0 (93.0–114.1) |

| Ascorbic Acid | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | – |

| TROLOX | – | 4.1 (3.7–5.8) |

*Ascorbic acid and TROLOX (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) were used as reference antioxidants for DPPH and ABTS analysis, respectively.

Hemolytic activity

The result presented in Fig. 3 show that HaEBcl did not disrupt the red cell membrane but preserved the integrity of the erythrocyte membrane in various NaCl concentrations.

Figure 3.

In-vitro hemolytic effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves (0–200 mg/ml) on female mice erythrocyte.

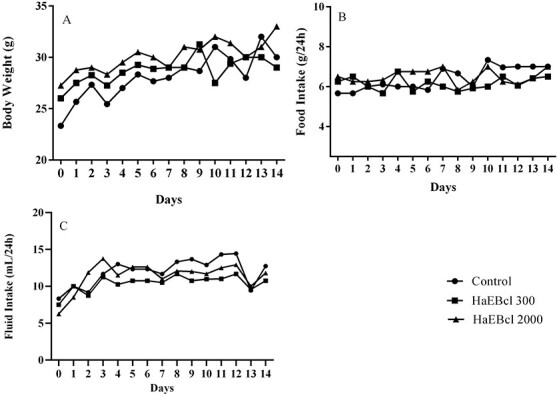

Acute oral toxicity (single dose evaluation of HaEBcl)

In acute toxicity testing, administration of a single oral dose of HaEBcl did not produce mortality or any toxic signs or symptoms at the different doses under study. No skin irritation, fur, eyes, mucous membrane toxic effects, piloerection, disorientation, hypoactivity, hyperventilation, asthenia, lethargy, sleep, diarrhea, tremors, salivation, convulsion, coma, motor activity, or death were registered. In addition, body weight gain and food and fluid consumption differences among the groups treated with HaEBcl were not observed (Fig. 4). Likewise, the macroscopic analysis revealed that HaEBcl did not produce any alteration in organ color, size, shape, or texture, compared with the control.

Figure 4.

Effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves through an oral acute toxicity test (single dose) on body weight gain (A), food intake (B) and fluid intake (C) in female Swiss mice.

As shown in Table 4, the oral acute toxicity of single dose of the HaEBcl did not produce relative weight organ alteration when compared with control group. In addition, neither any biochemical nor hematological parameters evaluated were statistically different in oral acute and a single dose treated mice when compared with control group at 14th day of experiment (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 4.

Effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilanthaπ (Bong.) Steud. leaves by an oral acute toxicity test on absolute total weight gain (g) and relative organ weight in female mice treated at 14th day

| Parameters | Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 300 mg/kg HaEBcl | 2.000 mg/kg HaEBcl | |

| Total weight gain (g) | 28.31 ± 0.58 | 28.90 ± 0.36 | 30.24 ± 0.39 |

| Tibia (mm) | 18.67 ± 0.7 | 18.25 ± 0.25 | 18.25 ± 0.48 |

| Liver (mg/mm) | 10.0 ± 0.67 | 10.0 ± 0.5 | 102.2 ± 0.5 |

| Kidneys (mg/mm) | 2.12 ± 0.17 | 2.51 ± 0.19 | 2.26 ± 0.11 |

| Heart (mg/mm) | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 0.80 ± 0.02 | 0.80 ± 0.06 |

| Lung (mg/mm) | 1.04 ± 0.07 | 1.06 ± 0.10 | 1.05 ± 0.11 |

| Stomach (mg/mm) | 1.42 ± 0.07 | 1.87 ± 0.13 | 1.90 ± 0.11 |

| Spleen (mg/mm) | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 0.82 ± 0.6 | 0.86 ± 0.6 |

| Uterus (mg/mm) | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.38 ± 0.05 |

| Ovaries (mg/mm) | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 |

| Adipose tissue (mg/mm) | 2.68 ± 0.28 | 3.53 ± 0.36 | 3.40 ± 0.15 |

| EDL (mg/mm) | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| Soleus (mg/mm) | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. One way ANOVA variance test was performed followed by Bonferroni test. The difference among groups were considered statically when P < 0.05.

Table 5.

Effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves on oral acute toxicity test in biochemical parameters in female mice treated at 14th day

| Parameters | Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | HaEBcl300 | HaEBcl2.000 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 69.10 ± 10.24 | 61.30 ± 1.85 | 61.47.50 ± 2.92 |

| AST(U/L) | 109.40 ± 11.41 | 93.52 ± 12.08 | 100.40.71 ± 4.44 |

| AST: ALT ratio | 1.40 ± 0.50 | 1.53 ± 0.20 | 1.53 ± 0.04 |

| TP (g/dl) | 5.76 ± 0.23 | 5.45 ± 0.05 | 5.65 ± 0.06 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.16 ± 0.17 | 1.90 ± 0.04 | 2.02 ± 0.23 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 73.13 ± 3.18 | 70.80 ± 6.664 | 70.50 ± 4.76 |

| CRE (mg/dl) | 0.50 ± 0.005 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.05 |

Results are expressed as Mean ± SEM. One way ANOVA variance test was performed followed by Bonferroni test. The difference among groups were considered statically when P < 0.05.

Table 6.

Effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves on oral acute toxicity test in hematological parameters in female mice treated at 14th day

| Parameters | Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | HaEBcl300 | HaEBcl2.000 | |

| RBC (106/mm3) | 7.15 ± 0.23 | 5.33 ± 0.36 | 6.71 ± 0.26 |

| HGB (g/dl) | 9.73 ± 0.48 | 7.68 ± 0.57 | 8.65 ± 0.30 |

| MCH (%) | 13.60 ± 0.31 | 13.05 ± 0.13 | 12.90 ± 0.20 |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 25.27 ± 0.52 | 12.90 ± 0.20 | 24.90 ± 0.21 |

| MCV (fL) | 54.00 ± 0.00 | 53.00 ± 0.71 | 51.75 ± 0.48 |

| HCT (%) | 38.53 ± 1.41 | 31.18 ± 2.17 | 34.65 ± 1.33 |

| RDW% (%) | 15.23 ± 0.07 | 14.85 ± 0.21 | 12.75 ± 1.16 |

| PLT (103/mm3) | 619.67 ± 72.65 | 582.25 ± 18.89 | 716.75 ± 49.30 |

| MPV (fL) | 6.90 ± 0.55 | 6.80 ± 0.85 | 6.15 ± 0.61 |

| WBC (109/l) | 3.70 ± 0.70 | 2.93 ± 0.91 | 3.50 ± 1.14 |

| LYM (mm3) | 8.83 ± 0.15 | 8.65 ± 1.47 | 8.39 ± 0.50 |

Results are expressed as Mean ± SEM. One way ANOVA variance test was performed followed by Bonferroni test. The difference among groups were considered statically when P < 0.05.

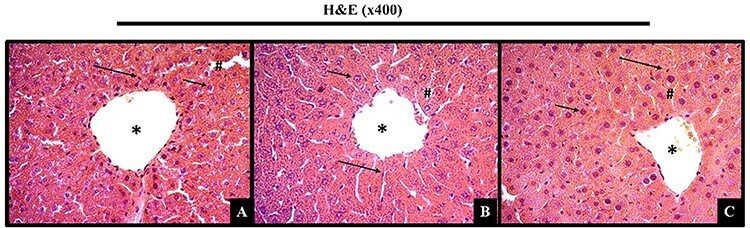

Histopathological examination of organs from animals treated with animals with different doses showed normal architecture, suggesting non-harmful changes, and morphological disorders induced by single oral dose of HaEBcl at 14th day of treatment (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Histological examination of liver sections from mice treated orally with hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves (300 or 2000 mg/kg) at 14 day in acute single dose toxicity study.

Sub-acute oral test (repeated dose 28-day oral toxicity)

General signs and mortality

All animals survived until scheduled necropsy. The sub-acute oral test was conducted over 4 weeks (28 days) with three different doses: 300, 1000, and 2000 mg/kg/day and control group. The daily observation did not reveal any sign of toxicity, altered behavior or mortality.

Body weight gain, food and fluid intake, and relative organ weight

Body weight gain, food, and fluid intake were compatible with physiological development for females and males during 28 days of treatment (Fig. 6). The relative tissue weights were not altered by hydroalcoholic extract of B. cheilantha leaves (Table 7). The organ mass analysis of the target tissues of the treated animals did not show significant (P < 0.05) changes when compared with the control group for either sex (Table 7).

Figure 6.

Effect of sub-acute oral toxicity evaluation of (28 days) of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves on body weight gain (A and B), food intake (C and D) and fluid intake (E and F) in female and male Swiss mice.

Table 7.

Effect of sub-acute oral toxicity evaluation of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves on absolute total body weight gain and relative organ weight in female and male Swiss mice treated for 28 consecutive days

| Sex | Parameters | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | HaEBcl300 | HaEBcl1.000 | HaEBcl2.000 | ||

| Female | Total weight gain (g) | 36.66 ± 0.49 | 33.15 ± 0.52 | 29.59 ± 0.48 | 35.58 ± 0.88 |

| Tibia (mm) | 19.3 ± 0.33 | 16.25 ± 0.48 | 19.25 ± 0.48 | 19.20 ± 0.37 | |

| Liver (mg/mm) | 8.36 ± 0.60 | 9.51 ± 0.38 | 6.71 ± 0.23 | 7.38 ± 0.67 | |

| Kidneys (mg/mm) | 2.09 ± 0.09 | 1.84 ± 0.04 | 1.90 ± 0.03 | 1.99 ± 0.14 | |

| Heart (mg/mm) | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.89 ± 0.08 | |

| Lung (mg/mm) | 1.48 ± 0.13 | 0.96 ± 0.06 | 1.04 ± 0.17 | 1.49 ± 0.25 | |

| Stomach (mg/mm) | 1.99 ± 0.09 | 1.80 ± 0.09 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 1.57 ± 0.31 | |

| Spleen (mg/mm) | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 0.42 ± 0.08 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | |

| Uterus (mg/mm) | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.67 ± 0.13 | 0.72 ± 0.34 | |

| Ovaries (mg/mm) | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.18 | |

| Adipose tissue (mg/mm) | 8.91 ± 1.32 | 7.93 ± 0.95 | 12.70 ± 1.46 | 9.29 ± 2.17 | |

| EDL (mg/mm) | 0.89 ± 0.17 | 0.69 ± 0.18 | 0.75 ± 0.23 | 0.98 ± 0.16 | |

| Soleus (mg/mm) | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | |

| Male | Total weight gain (g) | 37.99 ± 0.95 | 38.00 ± 0.79 | 36.97 ± 0.23 | 36.68 ± 0.87 |

| Tibia (mm) | 17.20 ± 0.80 | 20.20 ± 0.86 | 18.60 ± 0.93 | 18.50 ± 0.87 | |

| Liver (g/100 g) | 13.04 ± 2.86 | 13.89 ± 0.83 | 13.44 ± 0.63 | 13.79 ± 0.72 | |

| Kidneys (mg/mm) | 5.22 ± 0.23 | 4.78 ± 0.34 | 4.45 ± 0.34 | 4.06 ± 0.49 | |

| Heart (mg/mm) | 1.64 ± 0.08 | 1.37 ± 0.04 | 1.17 ± 0.07 | 1.44 ± 0.03 | |

| Lung (mg/mm) | 3.31 ± 0.33 | 2.98 ± 0.11 | 2.29 ± 0.10 | 2.59 ± 0.25 | |

| Stomach (mg/mm) | 3.57 ± 0.49 | 2.49 ± 0.27 | 2.56 ± 0.25 | 3.30 ± 0.72 | |

| Spleen (mg/mm) | 1.15 ± 0.15 | 0.96 ± 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.09 | 1.03 ± 0.13 | |

| Testicles (mg/mm) | 1.35 ± 0.07 | 1.29 ± 0.09 | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 1.08 ± 0.13 | |

| Adipose tissue (mg/mm) | 7.83 ± 0.43 | 8.59 ± 0.82 | 5.71 ± 0.60 | 6.36 ± 0.36 | |

| EDL (mg/mm) | 0.11 ± 0.07 | 0.37 ± 0.050 | 0.31 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.13 | |

Results are expressed as Mean ± SEM. One way ANOVA variance test was performed followed by Bonferroni test. The difference among groups were considered statically when P < 0.05. Weight gain, weight of heart, liver, and kidneys as normalized by tibial length, adipose tissue, soleus muscles and EDL.

Biochemical parameters

The treatment with HaEBcl during 28 consecutive days in doses of 300, 1000, and 2000 mg/kg did not change in any biochemical profile in mice of both sexes, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Effect of sub-acute oral toxicity evaluation of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves on biochemical parameters in female and male Swiss mice treated for 28 consecutive days

| Sex | Parameters | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | HaEBcl300 | HaEBcl1.000 | HaEBcl2.000 | ||

| Female | ALT (U/L) | 103.52 ± 6.91 | 88.5 ± 2.57 | 100.60 ± 5.73 | 83.50 ± 5.22 |

| AST (U/L) | 118.70 ± 4.33 | 100.10 ± 8.67 | 110.23 ± 9.65 | 90.71 ± 8.97 | |

| AST: ALT Ratio | 1.16 ± 0.06 | 1.82 ± 0.03 | 1.14 ± 0.03 | 1.25 ± 0.07 | |

| TP (g/dl) | 7.08 ± 0.52 | 6.01 ± 0.4 | 6.57 ± 0.17 | 6.92 ± 0.29 | |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 1.95 ± 0.09 | 1.82 ± 0.10 | 2.62 ± 0.09 | 2.70 ± 0.07 | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 65.92 ± 1.05 | 54.37 ± 3.43 | 46.13 ± 3.05 | 54.8 ± 2.52 | |

| CRE (mg/dl) | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | |

| Male | ALT (U/L) | 105.58 ± 6.88 | 98.88 ± 6.04 | 101.21 ± 1.04 | 99.39 ± 3.16 |

| AST(U/L) | 145.50 ± 8.94 | 144.77 ± 14.38 | 135.15 ± 12.75 | 147.25 ± 13.00 | |

| AST: ALT Ratio | 1.39 ± 0.10 | 1.55 ± 0.16 | 1.39 ± 0.11 | 1.47 ± 0.16 | |

| TP (g/dl) | 3.56 ± 0.04 | 3.57 ± 0.03 | 3.53 ± 0.04 | 3.48 ± 0.04 | |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.11 ± 0.13 | 1.99 ± 0.04 | 2.08 ± 0.15 | 1.84 ± 0.04 | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 78.76 ± 3.47 | 73.03 ± 4.11 | 65.21 ± 2.29 | 81.38 ± 3.21 | |

| CRE (mg/dl) | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | |

Results are expressed as Mean ± SEM. One way ANOVA variance test was performed followed by Bonferroni test. The difference among groups were considered statically when P < 0.05.

Hematological parameters

The oral sub-acute toxicity study did not produce any significant effect on the hematological parameters, after 28 days daily administration (Table 9).

Table 9.

Effect of sub-acute oral toxicity evaluation of hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves on hematological parameters in female and male Swiss mice treated for 28 consecutive days

| Sex | Parameters | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | HaEBcl300 | HaEBcl1.000 | HaEBcl2.000 | ||

| Female | RBC (106/mm3) | 8.01 ± 0.10 | 5.68 ± 0.13 | 7.61 ± 0.11 | 7.70 ± 0.22 |

| HGB (g/dl) | 15.21 ± 0.20 | 6.28 ± 0.21 | 13.40 ± 0.10 | 13.71 ± 0.34 | |

| MCH (%) | 18.90 ± 0.22 | 11.13 ± 0.50 | 32.91 ± 0.60 | 30.45 ± 0.60 | |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 31.41 ± 0.70 | 20.88 ± 1.16 | 34.06 ± 0.90 | 30.31 ± 0.92 | |

| MCV (fL) | 60.01 ± 1.72 | 53.50 ± 0.50 | 53.61 ± 1.63 | 59.10 ± 1.75 | |

| HCT (%) | 48.30 ± 1.61 | 30.30 ± 0.89 | 40.80 ± 0.91 | 45.24 ± 1.00 | |

| RDW% (%) | 15.00 ± 0.30 | 13.03 ± 0.59 | 13.15 ± 0.43 | 16.94 ± 0.15 | |

| PLT (103/mm3) | 474.00 ± 69.41 | 933.00 ± 135.25 | 532.25 ± 134.66 | 522.20 ± 199.95 | |

| MPV (fL) | 4.90 ± 0.05 | 6.37 ± 2.26 | 4.95 ± 0.15 | 4.87 ± 0.30 | |

| WBC (109/l) | 5.50 ± 0.70 | 3.35 ± 1.25 | 2.50 ± 0.10 | 3.71 ± 0.40 | |

| LYM (mm3) | 5.40 ± 0.70 | 4.70 ± 0.52 | 4.31 ± 0.3 | 4.60 ± 0.6 | |

| Male | RBC (106/mm3) | 7.86 ± 0.12 | 8.29 ± 0.17 | 7.81 ± 0.17 | 8.42 ± 0.14 |

| HGB (g/dl) | 14.2 ± 0.27 | 14.4 ± 0.13 | 13.76 ± 0.42 | 14.7 ± 0.26 | |

| MCH (%) | 18.4 ± 0.40 | 17.38 ± 0.32 | 17.86 ± 0.79 | 17.45 ± 0.26 | |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 35.42 ± 0.27 | 34.54 ± 0.39 | 36.02 ± 0.85 | 35.00 ± 0.44 | |

| MCV (fL) | 51.02 ± 0.90 | 50.34 ± 0.56 | 50.02 ± 1.28 | 49.92 ± 0.69 | |

| HCT (%) | 40.08 ± 0.74 | 41.74 ± 0.44 | 39.1 ± 0.69 | 42.05 ± 0.45 | |

| RDW (%) | 17.00 ± 0.16 | 17.18 ± 0.21 | 16.6 ± 0.23 | 17.68 ± 0.33 | |

| PLT (mm3) | 673.8 ± 22.89 | 766.8 ± 33.44 | 709.0 ± 13.59 | 719.5 ± 51.33 | |

| MPV (fL) | 4.84 ± 0.06 | 4.84 ± 0.04 | 4.66 ± 0.15 | 4.875 ± 0.06 | |

| WBC (109/l) | 1.38 ± 0.28 | 1.82 ± 0.11 | 1.96 ± 0.27 | 2.02 ± 0.30 | |

| LYM (mm3) | 1.32 ± 0.25 | 1.78 ± 0.11 | 1.98 ± 0.34 | 1.85 ± 0.25 | |

Results are expressed as Mean ± SEM. One way ANOVA variance test was performed followed by Bonferroni test. The difference among groups were considered statically when P < 0.05.

Histopathological parameters

Bauhinia cheilantha leaves from the sub-acute oral toxicity treatment did not produce any significant (P < 0.05) effect on the histopathological examinations of tissues on any of the harvested organs, indicating no treatment-related changes in the treated and control groups (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Histological examination of liver sections from mice treated orally with hydroalcoholic extract of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. leaves (300 or 2000 mg/kg) after 28-day sub-acute toxicity study.

Discussion

Species belonging to the Bauhinia genus are used around the world in traditional medicine for treating dysentery, diarrhea, colds, diabetes, and inflammation [2, 19–21]. Despite their positive biological effects, the absence of toxicological activity of this and other vegetal species should always be confirmed. Extract of B. cheilantha has been used in traditional medicine as a hypoglycemic agent [22]. Despite the popular use and the confirmed biological effects [4, 22], there are no studies about its toxicological safety. This study is the first report on the safe use of the hydroalcoholic extract of B. cheilantha leaves in mice. We provided clear evidence that HaEBcl did not show any sign of toxicity, with neither acute nor sub-acute symptoms in vivo. There was moderate antioxidant without hemolytic activity in vitro.

Assessment of toxic effect of natural products plays a crucial role in the guarantee for traditional use, in which hemolytic activity is first step towards providing information about the interaction between the active compounds and biological entities at cellular levels [23]. HaEBcl did not display hemolytic activity, probably because it stabilized the RBC membrane, reducing hypotonic solution-induced hemolysis. Mammalian cytotoxicity assays were also performed by hemolysis test [24]. Non-toxic effects of the plant extract, shown by absence of hemolytic activity, have also been reported by other researchers [24, 25]. It is not clear about what the precise mechanism of plant extract is that stabilizes the erythrocyte membrane. The alteration of the erythrocyte membrane permeability and increase in movement of water and ions cause excessive accumulation of fluid in the cell, allowing the release of hemoglobin [26]. It is possible that HaEBcl and its constituents may interreact with phospholipid and protein cellular membrane of the RBC. It is well-known that flavonoids protect erythrocyte membrane stability against hypotonic lysis [27]. In addition, stabilization of the erythrocyte membrane, by reducing the release of lytic enzymes, may contribute towards its anti-inflammatory property. Although his aspect was not the aim of this study, it should be noted that the antihemolytic activity can be associated with an anti-inflammatory property [26]. This suggests that HaEBcl, then, may be used in the future to combat inflammation with no toxic effects.

Considering the complexity of the phytochemical composition of plant extract, total antioxidant properties need to be evaluated, using at least two methods [28]. Here, we performed DPPH radical and ABTS scavenging antioxidant tests, which showed a moderate antioxidant activity which may be explained, at least in part, by the presence of flavonoids (quercitrin and afzelin), well-known natural antioxidant molecules [19, 29, 30]. Both DPPH and ABTS scavenging activities reflect a hydrogen-donating ability to form non radical species which in turn presents the lipid peroxidation of cellular components [19]. The antioxidant property has been strongly demonstrated in Bauhinia genus, such methanolic extract of B. variegate bark [20] and B. vahalii leaves [19]. There are also studies of the hydroalcoholic extract of B. forficata and B. microstachya leaves [31, 32]. Here, we show that HAEBcl has the ability to scavenge free radicals, and may be used as potential natural antioxidant to prevented biological damage caused by oxidative stress. This reinforces the potential use of the HaEBcl in biomedical applications.

Rodent models have been instrumental in helping to answer questions related to traditional use of the plants: in this case, toxicity [33]. Here, HaEBcl had no acute toxic effect in the evaluated doses for Swiss mice with respect to behavior, biochemical, histological, hemolysis activity, and body weight gain, food intake or sudden death. In addition, the non-acute toxicity effect could also suggest that the LD50 of this extract is greater than 2.000 mg/kg administered by oral route in mice. In accordance with OECD guidelines, HaEBcl is classified in category 5, as nontoxic [16]. To the best our knowledge, there is no scientific report about toxicity of B. cheilantha, however B holophylla [34], B. acuminata [35] and B. purpurea [21] have no acute toxic effect either.

Regulatory authorities require precise biochemical, hematological, and histopathological analyses to characterize the toxicological properties of any substance intended for prolonged use [36]. Thus, repeated-dose oral toxicity (sub-acute) may be evaluated after initial information on toxicity has been obtained by acute testing [37]. This strategy may determine the absolute toxic dose and target organ toxicity, and highlight biochemical, hematological and histopathological repercussions in mice. Sub-acute toxicity testing, in our study elicited no clinical signs of toxicity, morbidity, or mortality in any of the evaluated doses (300, 1000, and 2000 mg/kg), which may lead to the inference that these doses could be safely employed in disease treatment. Our data corroborates other studies by showing no signs of sub-acute toxicity by hydroalcoholic extracts Piper cernuum [15], B. purpurea [21, 38] Verbena litoralis up to 1000 mg/kg and 2000 mg/kg, respectively, during at least 28 days.

The 28-day oral sub-acute test revealed that HaEBcl provoked no deaths or clinical signs of toxicity in any dose evaluated. Body weight and food intake were similar for all the doses evaluated. HaEBcl compromised neither the metabolism of macronutrients and animal growth nor affected intra and extracellular dehydration in mice [39]. In addition, the absence of organ weight modifications, which are a simple and sensitive means for detecting harmful effects of xenobiotics [15] reaffirmed the non-toxicity effect of HaEBcl in subacute oral tested mice.

The analysis of blood parameters is relevant for risk evaluation, since changes in the hematological system have a higher predictive value for human toxicity, when data are translated from animal studies [17, 38]. In this sub-chronic study, HaEBcl did not elicit any changes in either white or RBC, nor in any of the hematological parameters evaluated, illustrating that this extract did not adversely affect animal health.

The liver plays a pivotal role in drug metabolism and biotransformation, and its function and structure may be evaluated for toxicity. Serum biomarkers are used to assess liver function and damage [17]. An increase in serum content of alanine and aspartate transaminases, as well as reduction in albumin and TP, are strong indicators of hepatic injury [40]. HaEBcl did not produce any alteration in any serum biomarker of the liver function, which was confirmed by the preservation of the normal liver architecture. An increase in serum CRE and urea levels indicates impaired kidney functions [40]. Similarly, HaEBcl did not alter the kidney functions in any dose evaluated in the oral acute and sub-chronic experiments with mice. The protective effect of the B. variegate and B. hookeri in acute liver and kidney injury induced by thioacetamide [41] and carbon tetrachloride [42] has been demonstrated in rats. Taken together, our results suggest that daily administration of HaEBcl in the tested doses does not produce any significant toxicity in female and male mice.

Conclusion

Based on oral acute and sub chronic administration in mice, it may be concluded that hydroalcoholic extract from B. cheilanta leaves has no clinical signs of toxicity effect or mortality in evaluated doses administered to mice. The DL50 value of HaEBcl is up to 2000 mg/kg in oral acute and up to 1000 mg/kg in oral sub chronic doses for both female and male mice. In general, HaEBcl may be classified to be safe, with a broad safety margin for therapeutic use. In addition, HaEBcl has a potential as a radical scavenger and to detect the presence of quercitrin and afzelin. This work provides valuable data for the safe use of HaEBcl which should be essential for future pharmacological studies. HaEBcl has a high potential for use in food and drug products, with remarkable benefits for human health.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the financial support of Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoa de Nível Superior (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, grant no. 424800/2018-7). We acknowledge the National Institute of Science and Technology—Ethnobiology, Bioprospecting and Nature Conservation (INCT), which is certified by CNPq and financially supported by the Science and Technology Support Foundation of the State of Pernambuco (FACEPE, grant no. APQ-0562-2.01/17) for the partial funding of the study. The English text of this paper has been revised by Sidney Pratt, Canadian, MAT (The Johns Hopkins University), RSAdip—TESL (Cambridge University).

Contributor Information

Alanne Lucena de Brito, Laboratório de Neuroendocrinologia e Metabolismo, Departamento de Fisiologia e Farmacologia, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Avenida Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235, 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil.

Carla Mirele Tabósa Quixabeira, Laboratório de Neuroendocrinologia e Metabolismo, Departamento de Fisiologia e Farmacologia, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Avenida Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235, 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil.

Lidiane Mâcedo Alves de Lima, Departamento de Química, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Rua Dom Manoel de Medeiros, S/N, 52171-900, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil.

Silvana Tavares Paz, Departamento de Patologia, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Avenida Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235, 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil.

Ayala Nara Pereira Gomes, Departamento de Química, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Rua Dom Manoel de Medeiros, S/N, 52171-900, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil.

Thiago Antônio de Souza Araújo, Departamento de saúde, Centro Universitário Maurício de Nassau, Rua Jonathas de Vasconcelos, 92, 51021-140, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Ulysses Paulino de Albuquerque, Laboratório de Ecologia e Evolução de Sistemas Socioecológicos, Departamento de Botênica, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Avenida Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235, 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Dayane Aparecida Gomes, Laboratório de Neuroendocrinologia e Metabolismo, Departamento de Fisiologia e Farmacologia, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Avenida Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235, 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil.

Tania Maria Sarmento Silva, Departamento de Química, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Rua Dom Manoel de Medeiros, S/N, 52171-900, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil.

Eduardo Carvalho Lira, Laboratório de Neuroendocrinologia e Metabolismo, Departamento de Fisiologia e Farmacologia, Centro de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Avenida Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235, 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil.

Glossary

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 2,2’-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (CRE), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), diode array detector (DAD), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), dethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), half maximal effective concentration (EC50), hematocrit (HCT), hemoglobin concentration (HBG), high performance liquid chromatography (HPCL), hydroalcoholic extract of B. cheilantha (HaEBcl), lethal dose (LD50), lymphocytes (LYM), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean platelet volume (MPV), organization for economic cooperation and development (OECD), platelet count (PLT), red blood cells (RBC), red cell volume distribution (RDW), total protein (TP), and white blood cells (WBC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Silva ACC, Oliveira DG. Population structure and spatial distribution of Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. in two fragments at different regeneration stages in the caatinga, in Sergipe, Brazil. Rev Arv Viçosa 2015;39:431–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Filho VC. Chemical composition and biological potential of plants from the genus Bauhinia. Phytother Res 2009;23:1347–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cartaxo SL, Souza MMA, Albuquerque UP. Medicinal plants with bioprospecting potential used in semi-arid northeastern Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol 2010;131:326–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Teixeira DC, Farias DF, Carvalho AFU et al. Chemical composition, nutritive value, and toxicological evaluation of Bauhinia cheilantha seeds: a legume from semiarid regions widely used in folk medicine. Biomed Res Int 2013;67881:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Isah T. Stress and defense responses in plant secondary metabolites production. Biol Res 2019;52:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dicson SM, Samuthirapandi M, Govindaraju A, et al. Evaluation of in vivo and in vitro safety profile of the Indian traditional medicinal plant Grewia tiliaefolia. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2015;73:241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jiang Ma, Qingsu Xia, Peter P. Fu, et al. , Pyrrole-protein adducts – A biomarker of pyrralizidine alkaloid-induced hepatotoxicity. J Food Drug Anal, 2018, 26(3), 965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kohnen-Johannsen KL, Kayser O. Tropane alkaloids: chemistry, pharmacology, biosynthesis and production. Molecules 2019;24:1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vanherweghem J-L, Depierreux M, Tielemans C et al. Rapidly progressive interstitial renal fibrosis in young women: association with slimming regimen including Chinese herbs. Lancet, 1993;341:387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Slinkard K, Singleton VL. Total phenol analyses: automation and comparison with manual methods. Am J Enol Viticult 1977;28:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woiky RG, Salatino A. Analysis of propolis: some parameters and procedures for chemical quality control. J Apicult Res 1998;37:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cabrera SP, Camara CA, Silva TMS. Chemical constituents of flowers from Geoffroea spinosa Jacq. (Leguminosae), a plant species visited by bees. Biochem Syst Ecol 2020;88:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Silva JP, Areias FM, Proença FM, et al. Oxidative stress protection by newly synthesized nitrogen compounds with pharmacological potential. Life Sci 2006;78:1256–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A et al. Antioxidant activity applying in improved ABTS radical cation. Decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med 1999;26:1231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolff FR, Broering MF, Jurcevic JD et al. Safety assessment of Piper cernuum Vell. (Piperaceae) leaves extract: acute, sub-acute toxicity and genotoxicity studies. J Ethnopharmacol 2018;10:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Organization for economic cooperation and development (OECD) Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, OECD 423 . Acute Oral Toxicity-Acute Toxic Class Method. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barbosa HM, Nascimento JN, Araújo TA et al. Acute toxicity and cytotoxicity effect of ethanolic extract of Spondias tuberosa Arruda bark: hematological, biochemical and histopathological evaluation. An Acad Bras Cienc 2016;88:1993–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Organization for economic cooperation and development (OECD) Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, OECD 407 . Acute Oral Toxicity-Acute Toxic Class Method. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sowndhararajan K, Kang SC. Free radical scavenging activity from different extracts of leaves of Bauhinia vahlii Wight & Arn. Saudi J Biol Sci 2013;20:319–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sharma N, Sharma A, Bhatia G et al. Isolation of phytochemicals from Bauhinia variegata bark and their in vitro antioxidant and cytotoxic potential. Antioxidants 2019;8:492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kumar S, Kumar R, Gupta YK, et al. In vivo anti-arthritic activity of Bauhinia purpurea Linn bark extract, Indian. J Pharmacol 2019;51:25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Almeida ER, Guedes MC, Albuquerque JFC, et al. Xavier HH. Hypoglycemic effect of Bauhinia cheilandra in rats. Fitoterapia 2006;77:276–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suganthy N, Muniasamy S, Archunan G. Safety assessment of methanolic extract of Terminalia chebula fruit, Terminalia arjuna bark and its bioactive constituent 7-methyl gallic acid: in vitro and in vivo studies. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2018;92:347–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silva SCC, Braz EMA, Carvalho FAA et al. Antibacterial and cytotoxic properties from esterified Sterculia gum. J Biol Macromol 2020;164:606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aquino DFS, Monteiro TA, Claudia ALC et al. Investigation of the antioxidant and hypoglycemiant properties of Alibertia edulis (L.C. Rich) A.C. Rich. leaves. J Ethnopharmocol 2020;253:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Javeda F, Jabeena Q, Aslamb N, et al. Pharmacological evaluation of analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activities of ethanolic extract of Indigofera argentea Burm. F. J Ethnopharmocology 2020;15:256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chaudhuri S, Banerjee A, Basu K et al. Interaction of flavonoids with red blood cell membrane lipids and proteins: antioxidant and antihemolytic effects. Int J Biol Macromol 2007;41:42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rejeb IB, Dhen N, Gargouri M, et al. Chemical composition, antioxidant potential and enzymes inhibitory properties of Globe artichoke by-products. Chem Biodivers 2020;6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silva KL, Filho VC. Plantas do gênero Bauhinia: composição química e potencial farmacológico. Quim Nova 2002;25:449–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sezer ED, Oktay LM, Karadadas E et al. Assessing Anticancer Potential of Blueberry Flavonoids, Quercetin, Kaempferol, and Gentisic Acid, Through Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis Parameters on HCT-116 Cells. J Med Food 2019;22:1118–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Menezes PR, Schwarz EA, Santos C.A.M. In vitro antioxidant activity of species collected in Paraná. Fitoterapia 2004;75:398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miceli N, Buongiorno LP, Celi MG et al. Role of the flavonoid-rich fraction in the antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of Bauhinia forficata Link. (Fabaceae) leaves extract. Nat Prod Res 2016;30:1229–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Atsafack SS, Kuiate J-R, Mouokeu RS et al. Toxicological studies of stem bark extract from Schefflera barteri Harms (Araliaceae). BMC Complement Altern Med 2015;15:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rozza AL, Cesar DA, Pieroni LG et al. Antiulcerogenic activity and toxicity of Bauhinia holophylla hydroalcoholic extract. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015;2015:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Padgaonkar AV, Suryavanshi SV, Londhe VY, et al. Acute toxicity study and anti-nociceptive activity of Bauhinia acuminata Linn. Leaf extracts in experimental animal models. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;97:60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Branquinho LS, Santos JA, Cardoso CAL et al. Anti-inflamatory and toxicological evaluation of essential oil from Piper glabratum leaves. J Ethnopharmacol 2017;198:372–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nazari S, Rameshrad M, Hosseinzadeh H. Toxicological effects of Glycyrrhiza glabra (Licorice): a review. Phytother Res 2017;31:1635–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lima R d, Guex CG, Silva ARH et al. Acute and subacute toxicity and chemical constituents of the hydroethanolic extract of Verbena litoralis Kunth. J Ethnopharmacol 2018;224:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aouachria S, Boumerfeg S, Benslama A et al. Acute, sub-acute toxicity and antioxidant activities (in vitro and in vivo) of Reichardia picroide crude extract. J Ethnopharmacol 2017;208:105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Senior JR. Alanine aminotransferase: a clinical and regulatory tool for detecting liver injury—past, present, and future. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012;92:332–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bashandy SAE, El Awdan SA, Mohamed SM, et al. Allium porrum and Bauhinia variegata mitigate acute liver failure and nephrotoxicity induced by thioacetamide in male rats. Indian J Clin Biochem 2020;35:147–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Al-Sayed E, Abdel-Daim MM, Kilany OE et al. Protective role of polyphenols from Bauhinia kookeri against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepato- and nephrotoxicity in mice. Ren Fail 2015;37:1198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]