Abstract

Ursolic acid is a natural compound possessing several therapeutic properties including anticancer potential. In present study, cytotoxic and antimetastatic properties of ursolic acid were investigated in intestinal cancer cell lines INT-407 and HCT-116. The cells growth and number were decreased in a dose- and time-dependent manner in both the cell lines. It also increases reactive oxygen species levels in the cells in order to induce apoptosis. Ursolic acid was found to be a significant inhibitor of cancer cells migration and gene expression of migration markers FN1, CDH2, CTNNB1 and TWIST was also downregulated. Ursolic acid treatment downregulated the gene expression of survival factors BCL-2, SURVIVIN, NFKB and SP1, while upregulated the growth-restricting genes BAX, P21 and P53. These results indicate that ursolic acid has anticancer and antimetastatic properties against intestinal cancer. These properties could be beneficial in cancer treatment and could be used as complementary medicine.

Keywords: ursolic acid; herbal medicine; reactive oxygen species; intestinal cancer; NFKB, SP1

Introduction

Intestinal cancer is a common cancer type worldwide with the leading subtype colorectal cancer, which is the third most diagnosed carcinoma and a leading cause of cancer-associated deaths worldwide [1]. Annually, there are more than half a million deaths due to colorectal cancer, which accounts for 8% of all cancer deaths [2]. Due to the excessive toxicity of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, herbal medication is an emerging field of interest. Herbal medication provides a safe and effective treatment option for cancer treatment. The herbal medicines can modulate the immune system, and improve overall survival and quality of life when administered as complementary medicine [3]; one such complementary compound is 3β-hydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic-acid or Ursolic acid (UA) (Fig. 1A). Structurally, it is a pentacyclic triterpenoid, which has the molecular formula C30H48O3 and 456.70 g/mol molecular weight. The melting point of UA is 283–285°C and it is soluble in methanol, pyridine and acetone, but is insoluble in water and petroleum ether [4]. UA belongs to cyclosqualenoid family and found in the various medicinal plants such as Ocimum basilicum (holy basil), Malus domestica (Apple), Vaccinium macrocarpon Air (cranberry), Rosemarinus officinalis, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng (bearberry), Rhododendron hymenanthes Makino, Calluna vulgaris, Eugenia jambolana and Eriobotrya japonica etc. [5]. Ursolic acid possesses disease-preventing and treatment properties, which are associated with its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential [6–8], thus it has been used to treat metabolic and cardiovascular diseases [9], including different types of cancer [10,11]. The involvement of ursolic acid was reported in the cell cycle arrest, growth inhibition, apoptosis and metastasis inhibition via regulating multiple signaling pathways [12]. The therapeutic potential of ursolic acid has been studied in cancers of the bladder, thyroid, breast, lung, gastric, hepatic, cervical, glioma, leukemia, multiple myeloma, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate and melanoma [13]. At the molecular level, ursolic acid inhibits the expression of urokinase plasminogen activator, interleukin-8, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), NFkB and activate ROCK/PTEN mediated cofilin-1 resulting in reduced cancer cell proliferation [6,14]. The present study explores the effects of ursolic acid treatment on cell proliferation, nuclear morphology and the metastatic properties of INT-407 and HCT-116 human intestinal cancer cells.

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structure of ursolic acid (B) cytotoxicity of different concentrations of ursolic acid in human intestinal cancer cells INT-407 and HCT-116 at 24 and 48 h. (C) Fluorescence images of acridine orange and propidium iodide-stained INT-407 cells and histograms represented the quantified data as viable, early and late apoptotic cells. (D) Fluorescence images HCT-116 cells and histograms represented the quantified data. The data represent the mean ± SE of three experiments (statistically significant differences, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Materials and Methods

Materials

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium (DMEM), Fetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin-EDTA solution Phosphate buffer saline (PBS), Antibiotic Antimycotic Solution and Gentamicin Solution were purchased from HIMEDIA laboratories (Mumbai, India). Ursolic acid (90%), 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA), N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), 2′-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)-2,5′-bi-1H-benzimidazole trihydrochloride hydrate (Hoechst 33258) and propidium iodide were procured from Sigma-Aldrich Pvt. Ltd. (USA). High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit and SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). RNASure Mini Kit was purchased from Genetix biotech (India). Cell cultures (INT-407 and HCT-116) were purchased from National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India. All other chemicals used were of molecular and analytical grade.

Cell culture conditions and maintenance

The human intestinal carcinoma cell lines INT-407 and HCT-116 were cultured and maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 (Sanyo, Japan). Cell lines were regularly monitored for contaminations.

Cytotoxicity assay

The INT-407 and HCT-116 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate with a density of 104 cells per well and incubated overnight. After overnight incubation, cells were treated with ursolic acid (5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 and 50 μM) and again incubated for 24 and 48 h. After treatment, the ursolic acid-containing media was discarded and cells were washed with 1X PBS to remove the traces of UA. Then, cells were incubated with 50 μl of (5 mg/ml) MTT solution for 3–4 h in CO2 incubator. Then, MTT solution was removed carefully without disturbing the formazan crystals and 100 μl DMSO was added in order to dissolve formazan crystals which were formed by viable cells. Absorbance was recorded by Multiskan™ GO Microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 570 nm. The mean inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated by the linear regression method.

Viable and dead cells detection by acridine orange/propidium iodide staining

Cells were seeded in a 12-well plate with a density of 105 cells per well and incubated overnight. After overnight incubation, treatment was given with defined concentrations of ursolic acid (0, 5, 34.7 μM for INT-407, 34.9 μM for HCT-116 and 50 μM) and incubated for 24 h. After treatment, the media was discarded and cells were washed with 1X PBS. Then, cells were stained with acridine orange (AO) and propidium iodide PI (1:1) for 15 min in the dark. After staining, the stain was removed and cells were washed with 1X PBS twice to remove over staining. The cells were visualized under the fluorescence microscope (CKX53, Olympus, Japan). The number of viable, early and late apoptotic cells was counted for three random microscopic fields.

Measurement of ROS by 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) assay

Cells were seeded in a 12-well plate and incubated overnight. Then, cells were treated with ursolic acid (0, 5, IC50 and 50 μM) and incubated for 24 h. After ursolic acid treatment, the 10 μM 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA) was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min under dark condition. Then, the media was discarded and cells were washed with 1X PBS and immediately visualized under a fluorescence microscope (CKX53, Olympus, Japan).

Nuclear morphology by Hoechst 33258

The cells were seeded on poly L-lysine coated coverslips in a 12-well plate with 1 × 105 cells/well seeding density and incubated overnight. Then, cells were treated with ursolic acid (0, 5, 34.7 μM for INT-407, 34.9 μM for HCT-116) for 24 h. After that, the media was discarded and cells were washed with 1X PBS and fixed with freshly prepared 4% formaldehyde solution for 10–15 min at room temperature. Then, formaldehyde was discarded and cells were washed with 1X PBS. After washing, Triton X-100 (0.01%) was added to the cells for 10 min at RT. Triton X-100 was discarded and cells were washed with 1X PBS. Then, cells were stained with a working solution of Hoechst 33258 (1:1500 dilution in 1X PBS) for 10–15 min at room temperature under dark conditions. Stain was removed and cells were washed twice with 1X PBS to avoid over staining. The coverslips were mounted on slides with VECTASHIELD antifade mounting medium and visualized under a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV3000, Olympus Corporation, Japan).

Cell migration assay

Cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well in a 6-well plate and were cultured for 24 h in 4% FBS till 90% confluency. A straight scratch was created by scraping the monolayer with a sterile micropipette tip (200 μl) and the floating cells were washed with 1X PBS and treated with ursolic acid (0, 5, 10 and 20 μM). The microscopic images of each scratch were captured at 0, 12 and 24 h time points. Each scratch was examined and the healed area was measured by a brightfield microscope (CKX53, Olympus, Japan).

RNA expression analysis

Cells were treated with ursolic acid for 24 h and total RNA was extracted by RNASure Mini Kit (Genetix, India) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA was checked for concentration and purity by the Nano-Drop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using high-capacity cDNA synthesis kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time qPCR was performed to analyze the expression pattern of target genes according to our previously reported protocol [15]. Human 18 s rRNA expression was kept as a housekeeping gene.

Statistical analysis

Three independent experiments were performed for each assay and results were shown as means ± SEM. Student’s t-test and two-way ANOVA were employed to analyze the differences between data sets. The P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

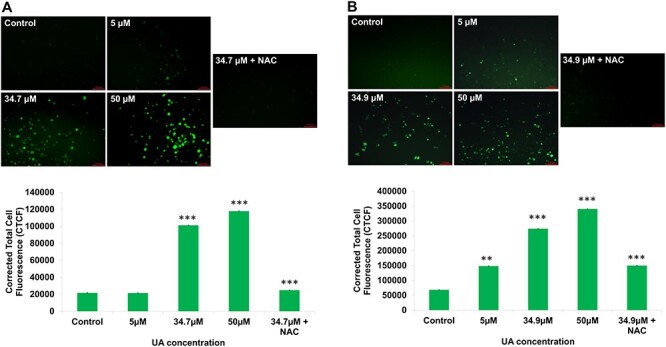

Ursolic acid exposure kills the intestinal cancer cells by inducing intracellular ROS

The two intestinal cancer cells INT-407 and HCT-116 were exposed to ursolic acid for 24 and 48 h. The obtained data show the dose- and time-dependent growth inhibition in both the cell lines (Fig. 1B). The mean inhibitory concentration was calculated for 24 h time point and found to be 34.7 μM and 34.9 μM for INT-407 and HCT-116, respectively. Moreover, a significant number of membrane-compromised and dead cells were observed via AO-PI staining, which further supports the MTT data suggesting ursolic acid as a potent cytotoxic compound for intestinal cancer cells (Fig. 1C and D). Then, cells were examined for the intracellular ROS levels after ursolic acid treatment. The high intensity of fluorescence was observed in IC50 (34.7 μM for INT-407 and 34.9 μM for HCT-116) and 50 μM treated cells, representing the level of ROS. The UA-induced oxidative stress was reversed by 5 mM NAC treatment. The intensity of fluorescence was quantified and calculated as corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) and found to be statistically significant (Fig. 2). The above results reveal that ursolic acid promotes cell death in intestinal cancer cells by increasing ROS levels.

Figure 2.

(A) Fluorescence images show intracellular ROS level in INT-407 cells after ursolic acid treatment and histograms represent the quantified data. (B) Intracellular ROS level in HCT-116 cells after ursolic acid treatment and histograms represent the quantified data. The data represent the mean ± SE of three experiments (statistically significant differences, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Ursolic acid induce chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation

The ursolic acid treated cells were observed after Hoechst 33258 staining for nuclear morphology. The control group nuclei were round and no fragmentation was observed, while in the treated cells, condensed and fragmented nuclei were observed. The number of normal and damaged nuclei was counted. The number of fragmented nuclei in treated groups was found to be statistically significant (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(A) Fluorescence images show nuclear morphology of ursolic acid-treated INT-407 cells and percentage of condensed and fragmented nuclei in different treatment groups. (B) Nuclear morphology of ursolic acid-treated HCT-116 cells and percentage of condensed and fragmented nuclei in different treatment groups. The data represent the mean ± SE of three experiments (statistically significant differences, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Ursolic acid restricts the migration ability of cancer cells

The cells in the control groups were migrated normally and healed the maximum wounded area, while the treated groups showed a reduced rate of migration and less or no healing was observed in both of the cell lines. The area of the scratch was measured and found to be statistically significant compared to the control groups. These results indicate that ursolic acid inhibits cell migration in intestinal cancer (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

(A) Migration of INT-407 cells after ursolic acid treatment and area of the wound at different time interval. (B) Migration of HCT-116 cells after ursolic acid treatment and histograms represented the area of the wound at different time interval. The data represent the mean ± SE of three experiments (statistically significant differences, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

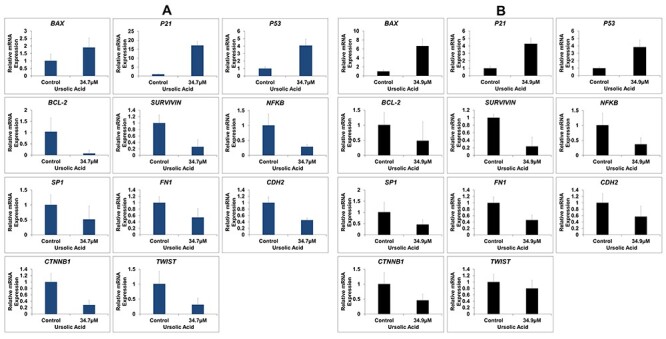

Gene expression after ursolic acid treatment in intestinal cancer cells

The mRNA expression was analyzed in ursolic acid treated cells by real-time PCR. The antiapoptotic genes BCL-2 and SURVIVIN were downregulated, while BAX was upregulated. Moreover, the expression of NFKB and SP1, cell growth promoters, was downregulated after ursolic acid treatment. The cell cycle regulator P21 and P53 were found to be upregulated. Cell migration associated genes FN1, CDH2, CTNNB1 and TWIST were downregulated in treated groups (Fig. 5). The normalized fold changes of all the genes are provided in Table 1.

Figure 5.

(A) Relative gene expression in INT-407 cells after ursolic acid treatment. (B) Relative gene expression in HCT-116 cells after ursolic acid treatment. Human 18 s rRNA gene was used as housekeeping gene to calculate normalized fold change.

Table 1.

Relative mRNA expression of target genes in ursolic acid-treated cancer cells (Fold change)

| Gene Name | INT-407 | HCT-116 |

|---|---|---|

| BAX | 1.9 ↑ | 6.6 ↑ |

| P21 | 17.1 ↑ | 4.2 ↑ |

| P53 | 4 ↑ | 3.8 ↑ |

| NFKB | 3.5 ↓ | 2.7 ↓ |

| SP1 | 2 ↓ | 2.5 ↓ |

| BCL-2 | 13.3↓ | 2 ↓ |

| SURVIVIN | 3.8 ↓ | 4.3 ↓ |

| FN1 | 1.8 ↓ | 2.1 ↓ |

| CDH2 | 2.2 ↓ | 1.75 ↓ |

| CTNNB1 | 3.5 ↓ | 2.2 ↓ |

| TWIST | 3.3 ↓ | 1.25 ↓ |

Discussion

Intestinal cancer is a major health concern in developed and developing nations despite emerging treatment modalities. Herbal medicines provide a low cost and effective treatment option over modern synthetic medicines from an economic aspect. Among herbal approaches, ursolic acid was a candidate therapeutic drug as complementary medicine [6,7,10]. There are several herbal compounds well known to induce cell death [15–18]. This report focused on the effect of ursolic acid on intestinal cancer cells INT-407 and HCT-116, which suppressed the cancer cell growth and proliferation by inducing apoptosis. Ursolic acid usually shows antioxidant properties but can be a ROS inducer in the colorectal cancer cells [19,20]. In the current study, we also found high ROS levels in treated compared to the control groups; this might be one of the mechanisms behind apoptosis in intestinal cancer cells. Moreover, the nuclei of ursolic acid-treated cancer cells were found to be condensed and fragmented, which further supports the cytotoxic effect of ursolic acid on intestinal cancer cells. Metastatic property is the deadliest side of the cancerous cells, as it increases the complexity and decreases the survival rate [21]; it was significantly suppressed by ursolic acid treatment in both the cell lines. Further, in molecular analysis, RNA expression was determined by real-time PCR. The

crucial antiapoptotic BCL-2 and SURVIVIN genes were downregulated and pro-apoptotic BAX gene was upregulated after ursolic acid treatment [22,23], which suggests that the ursolic acid promotes apoptosis in intestinal cancer cells. Several reports show the involvement of NFKB in cell survival and cancer progression. Ursolic acid treatment significantly decreased the expression of NFKB in the treated group in both the cell lines, indicating the inhibition of cellular growth. Interestingly, the SP1 gene was also found downregulated upon ursolic acid treatment, which is reported to be upregulated in ovarian, breast, gastric, colon and hepatocellular carcinoma [18,24–31]. The SP1 transcription factor induces several survival-associated genes to inhibit apoptosis [31–33]. Moreover, the cell cycle regulator P21 was found to be upregulated, which suggest the cell cycle inhibition by ursolic acid in intestinal cancer cells. The P53 gene was also upregulated, as the ursolic acid treatment increases ROS, which possibly causes nuclear damage, which could further lead to the damage-responsive expression of P53 gene. Principle migration marker genes such as FN1, CDH2, CTNNB1 and TWIST, which regulate cellular migration found to be downregulated after ursolic acid treatment in both the cell lines. These findings clearly show the therapeutic potential of ursolic acid for intestinal cancer treatment.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Laxminarayan Rawat: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing—original draft. Vijayashree Nayak: Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Central Sophisticated Instrumentation Facility (CSIF), Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, K.K. Birla Goa Campus for confocal microscopy.

Contributor Information

Laxminarayan Rawat, Department of Biological Sciences, Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, K.K. Birla Goa Campus, NH-17B, Zuarinagar, Goa, 403726, India.

Vijayashree Nayak, Department of Biological Sciences, Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, K.K. Birla Goa Campus, NH-17B, Zuarinagar, Goa, 403726, India.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sreevalsan S, Safe S. Reactive oxygen species and colorectal cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep 2013;9:350–7. doi: 10.1007/s11888-013-0190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yin SY, Wei WC, Jian FY et al. Therapeutic applications of herbal medicines for cancer patients, evidence-based complement. Altern Med 2013;2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/302426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kashyap D, Tuli HS, Sharma AK. Ursolic acid (UA): a metabolite with promising therapeutic potential. Life Sci 2016;146:201–13. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. NGO SNT, Williams DB, Head RJ. Rosemary and cancer prevention: preclinical perspectives. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2011;51:946–54. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.490883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mu D, Zhou G, Li J et al. Ursolic acid activates the apoptosis of prostate cancer via ROCK/PTEN mediated mitochondrial translocation of cofilin-1. Oncol Lett 2018;15:3202–6. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prasad S, Tyagi AK. Chemosensitization by Ursolic acid: a new avenue for cancer therapy. Role Nutraceuticals Cancer Chemosensitization 2018;99–109. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-812373-7.00005-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yin R, Li T, Tian JX et al. Ursolic acid, a potential anticancer compound for breast cancer therapy. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2018;58:568–74. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1203755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Y.-T. Lin, Y.-M. Yu, W.-C. Chang, et al. Ursolic acid plays a protective role in obesity-induced cardiovascular diseases. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 94 (2016) 627–633. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laszczyk MN. Pentacyclic triterpenes of the lupane, oleanane and ursane group as tools in cancer therapy. Planta Med 2009;75:1549–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1186102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prasad S, Yadav VR, Sung B et al. Ursolic acid inhibits growth and metastasis of human, colorectal cancer in an orthotopic nude mouse model by targeting multiple cell signaling pathways: Chemosensitization with capecitabine. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:4942–53. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woźniak Ł, Skąpska S, Marszałek K. Ursolic acid - a pentacyclic triterpenoid with a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities. Molecules 2015;20:20614–41. doi: 10.3390/molecules201119721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin CC, Huang CY, Mong MC et al. Antiangiogenic potential of three triterpenic acids in human liver cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem 2011;59:755–62. doi: 10.1021/jf103904b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rawat L, Hegde H, Hoti SL et al. Piperlongumine induces ROS mediated cell death and synergizes paclitaxel in human intestinal cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother 2020;128:110243. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Lei P et al. Betulinic acid inhibits colon cancer cell and tumor growth and induces proteasome-dependent and -independent downregulation of specificity proteins (Sp) transcription factors. BMC Cancer 2011;11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gandhy SU, Kim K, Larsen L et al. Curcumin and synthetic analogs induce reactive oxygen species and decreases specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors by targeting microRNAs. BMC Cancer 2012;12:564. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chadalapaka G, Jutooru I, Safe S. Celastrol decreases specificity proteins (Sp) and fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 (FGFR3) in bladder cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2012;33:886–94. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Y, Huang L, Shi H et al. Ursolic acid enhances the therapeutic effects of oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer by inhibition of drug resistance. Cancer Sci 2018;109:94–102. doi: 10.1111/cas.13425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kasiappan R, Jutooru I, Mohankumar K et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-inducing triterpenoid inhibits rhabdomyosarcoma cell and tumor growth through targeting SP transcription factors. Mol Cancer Res 2019;17:794–805. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH et al. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020;5. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0134-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ola MS, Nawaz M, Ahsan H. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins and caspases in the regulation of apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem 2011;351:41–58. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0709-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mita AC, Mita MM, Nawrocki ST et al. Survivin: key regulator of mitosis and apoptosis and novel target for cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:5000–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. R. Bajpai, G.N.-C.R. in Oncology/Hematology, undefined 2017, Specificity protein 1: its role in colorectal cancer progression and metastasis, Elsevier. (n.d.). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040842816304048 (5 January 2021, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yie Y, Zhao S, Tang Q et al. Ursolic acid inhibited growth of hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells through AMPKα-mediated reduction of DNA methyltransferase 1. Mol Cell Biochem 2014;402:63–74. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vellingiri I, Subramaniam D, Jayaramayya S et al. Understanding the role of the transcription factor Sp1 in ovarian cancer: from theory to practice. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1153. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou C, Ji J, Cai Q et al. MTA2 promotes gastric cancer cells invasion and is transcriptionally regulated by Sp1. Mol Cancer 2013;12:102. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takeuchi H, Taoka R, Mmeje CO et al. CDODA-Me decreases specificity protein transcription factors and induces apoptosis in bladder cancer cells through induction of reactive oxygen species. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig 2016;34:337.e11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jutooru I, Chadalapaka G, Abdelrahim M et al. Methyl 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oate decreases specificity protein transcription factors and inhibits pancreatic tumor growth: role of microRNA-27a. Mol Pharmacol 2010;78:226–36. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.064451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hedrick E, Cheng Y, Jin UH et al. Specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors Sp1, Sp3 and Sp4 are non-oncogene addiction genes in cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016;7:22245–56. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Safe S, Abbruzzese J, Abdelrahim M et al. Specificity protein transcription factors and cancer: opportunities for drug development. Cancer Prev Res 2018;11. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-17-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beishline K, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Sp1 and the ‘hallmarks of cancer. FEBS J 2015;282:224–58. doi: 10.1111/FEBS.13148@10.1002/(ISSN)1742-4658(CAT)FREEREVIEWCONTENT(VI)REVIEWS1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Asanuma K, Tsuji N, Endoh T et al. Survivin enhances Fas ligand expression via up-regulation of specificity protein 1-mediated gene transcription in colon cancer cells. J Immunol 2004;172:3922–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. J. Boulaire, A. Fotedar, R. Fotedar. The functions of the cdk-cyclin kinase inhibitor p21(WAF1), Pathol Biol 48 (2000) 190–202. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10858953 (13 May 2018, date last accessed). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]