Abstract

We report low-temperature muon spin relaxation/rotation (μSR) measurements on single crystals of the actinide superconductor UTe2. Below 5 K we observe a continuous slowing down of magnetic fluctuations that persists through the superconducting transition temperature (Tc = 1.6 K), but we find no evidence of long-range or local magnetic order down to 0.025 K. The temperature dependence of the dynamic relaxation rate down to 0.4 K agrees with the self-consistent renormalization theory of spin fluctuations for a three-dimensional weak itinerant ferromagnetic metal. Our μSR measurements also indicate that the superconductivity coexists with the magnetic fluctuations.

The unusual physical properties of intermetallic uranium-based superconductors are primarily due to the U-5f electrons having both localized and itinerant character. In a subclass of these compounds, superconductivity coexists with ferromagnetism. In URhGe and UCoGe [1,2] this occurs at ambient pressure, whereas superconductivity appears over a limited pressure range in UGe2 and UIr [3,4]. With the exception of UIr, the Curie temperature of these ferromagnetic (FM) superconductors signficantly exceeds Tc, and the upper critical field Hc2 at low temperatures greatly exceeds the Pauli paramagnetic limiting field. These observations indicate that the superconducting (SC) phases in these materials are associated with spin-triplet Cooper pairing, and likely mediated by low-lying magnetic fluctuations in the FM phase [5–8]. The triplet state is specifically nonunitary, characterized by a nonzero spin-triplet Cooper pair magnetic moment due to alignment of the Cooper pair spins with the internal field generated by the preexisting FM order.

Very recently, superconductivity has been observed in UTe2 at ambient pressure below Tc ~ 1.6 K [9]. The superconductivity in UTe2 also seems to involve spin-triplet pairing, as evidenced by a strongly anisotropic critical field Hc2. Furthermore, a large residual value of the Sommerfeld coefficient γ is observed in the SC state, which is nearly 50% of the value of γ above Tc [9,10]. This suggests that only half of the electrons occupying states near the Fermi surface participate in spin-triplet pairing, while the remainder continue to form a Fermi liquid. While this is compatible with UTe2 being a nonunitary spin-triplet superconductor (in which the spin of the Cooper pairs is aligned in a particular direction), unlike URhGe, UCoGe, and UGe2, there is no experimental evidence for ordering of the U-5f electron spins prior to the onset of superconductivity. Instead, the normal-state a-axis magnetization exhibits scaling behavior indicative of strong magnetic fluctuations associated with metallic FM quantum criticality [9].

Little is known about the nature of the magnetism in UTe2 below Tc, including whether it competes or coexists with superconductivity. Specific heat measurements show no anomaly below Tc [9,10], but like other bulk properties may be insensitive to a FM transition with little associated entropy (such as small-moment itinerant ferromagnetism). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments indicate the development of low-frequency longitudinal magnetic fluctuations and the vanishing of the NMR signal along the a axis below 20 K [11]. Here we report muon spin relaxation/rotation (μSR) experiments on UTe2 single crystals that confirm the absence of FM order below Tc and demonstrate the presence of magnetic fluctuations consistent with FM quantum criticality that coexist with superconductivity.

The UTe2 single crystals were grown by a chemical vapor transport method. Powder x-ray diffraction (XRD) and Laue XRD measurements indicate that the single crystals are of high quality. The details of the sample growth and characterization are given in Ref. [9]. Zero-field (ZF), longitudinal-field (LF), transverse-field (TF), and weak transverse-field (wTF) μSR measurements were performed on a mosaic of 21 single crystals. Measurements over the temperature range 0.02 K ≲ T ≲ 5 K were achieved using an Oxford Instruments top-loading dilution refrigerator on the M15 surface muon beam line at TRIUMF. The UTe2 single crystals covered ~70% of a 12.5 mm × 14 mm silver (Ag) sample holder. For the ZF-μSR experiments, stray external magnetic fields at the sample position were reduced to ≲20 mG using the precession signal due to muonium (Mu ≡ μ+ e−) in intrinsic Si as a sensitive magnetometer [12]. The TF and LF measurements were performed with a magnetic field applied parallel to the linear momentum of the muon beam (which we define to be in the z direction). The wTF experiments were done with the field applied perpendicular to the beam (defined to be the x direction). The initial muon spin polarization P(0) was directed parallel to the z axis for the ZF, LF, and wTF experiments, and rotated in the x direction for the TF measurements. The c or the a axis of the single crystals was arbitrarily aligned in the z direction. All error bars herein denote uncertainties of one standard deviation.

Representative ZF-μSR asymmetry spectra for UTe2 at T = 0.04 and 4.9 K are shown in the inset of Fig. 1. No oscillation indicative of magnetic order is observed in any of the ZF-μSR spectra, which are well described by a three-component function consisting of two exponential relaxation terms plus a temperature-independent background term due to muons stopping outside the sample:

| (1) |

The sum of the sample asymmetries A1 + A2 is a measure of the recorded decay events originating from muons stopping in the sample. A global fit of the ZF spectra for all temperatures assuming common values of the asymmetry parameters, yielded A1/A(0) = 24%, A2/A(0) = 29%, and AB/A(0) = 47%. A previous μSR study of UGe2 identified two muon stopping sites, with site populations of ~45% for one site and ~55% for the other [13], in excellent agreement with the results here. The temperature variation of the ZF relaxation rates λ1 and λ2 are shown in Fig. 1. The monotonic increase in λ1 and λ2 with decreasing temperature indicates that the local magnetic field sensed at each muon site is dominated by a slowing down of magnetic fluctuations, as explained below. The difference in the size of the relaxation rates reflects a difference in the dipolar and hyperfine couplings of the U-5f electrons to the muon at the two stopping sites.

FIG. 1.

Temperature dependence of the ZF exponential relaxation rates obtained from fits of the ZF-μSR asymmetry spectra to Eq. (1). Inset: Representative ZF signals for T = 4.9 K and T = 0.04 K. The solid curves are the resultant fits to Eq. (1).

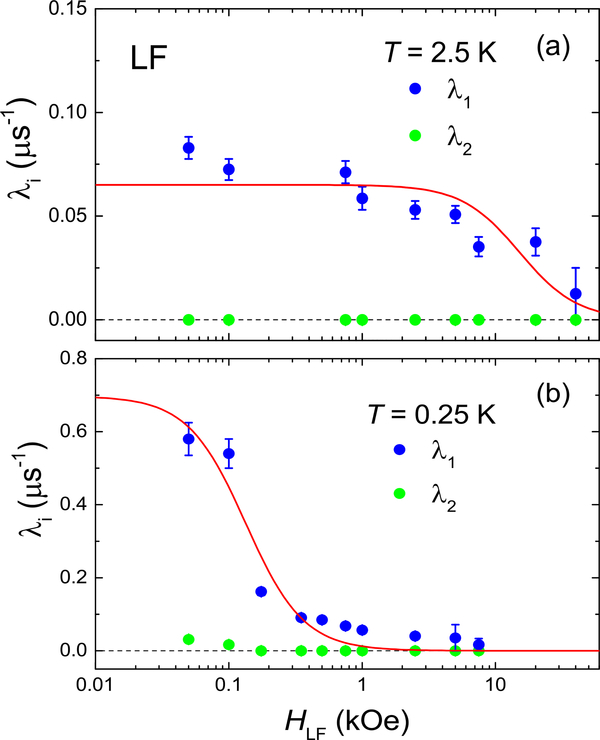

To confirm the dynamic nature of the magnetism, LF-μSR measurements were performed for various longitudinal applied fields HLF. Representative LF-μSR asymmetry spectra for T = 2.5 and 0.25 K are shown in Fig. 2. The LF signals are reasonably described by Eq. (1). Figure 3 shows the dependence of the fitted relaxation rates λ1 and λ2 on HLF. Also shown in Fig. 3 are fits of the field dependence of the larger relaxation rate λ1 to the Redfield equation [14]

| (2) |

where is the mean of the square of the transverse components of the time-varying local magnetic field at the muon site, and τ is the characteristic fluctuation time. The fit for 2.5 K yields λ1(HLF = 0) = 0.065(5) μs−1, τ = 8(3) × 10−10 s, and Bloc = 76(22) G, whereas the fit for 0.25 K yields λ1(HLF = 0) = 0.70(9) μs−1, τ = 9(2) × 10−8 s, and Bloc = 23(4) G. We could not confirm similar fluctuation rates at the second muon site, because λ2 is much smaller and not well resolved for most fields.

FIG. 2.

Representative LF-μSR asymmetry spectra at (a) 2.5 K and (b) 0.25 K, for several different values of the applied magnetic field. The solid curves are fits to Eq. (1).

FIG. 3.

Field dependence of the relaxation rates λ1 and λ2 from the fits of the LF-μSR asymmetry spectra at (a) 2.5 K, and (b) 0.25 K. The solid red curves are fits of λ1(HLF) to Eq. (2).

Above ~150 K, the magnetic susceptibility χ(T) of UTe2 is described by a Curie-Weiss law with an effective magnetic moment μeff that is close to the expected value (3.6μB/U) for localized U-5f electrons and a Weiss temperature θ ~ −100 K [15]. However, near ~35 K, χ(T) for the H ‖ b axis exhibits a maximum that suggests the U-5f electrons may become more itinerant at lower temperatures. Figure 4 shows the temperature dependence of λ1/T, where λ1 (≡1/T1) is the larger of the two dynamic ZF exponential relaxation rates. The phenomenological self-consistent renormalization (SCR) theory for itinerant ferromagnetism [16], predicts that 1/T1T ∝ T−4/3 near a FM quantum critical point (QCP) in a three-dimensional metal [17]. As shown in Fig. 4, this behavior is observed down to T = 0.4 K. The deviation below ~0.3 K suggests a breakdown in SCR theory close to the presumed FM QCP. The inset of Fig. 4 shows that T1T (which is proportional to the inverse of the imaginary part of the dynamical local spin susceptibility) goes to zero as T → 0, which provides evidence for the ground state of UTe2 being close to a FM QCP.

FIG. 4.

Temperature dependence of λ1/T (≡1/T1T) for zero field. The solid blue line is a fit of the data over 0.4 ⩽ T ⩽ 4.9 K to the power-law equation 1/T1T ∝ T −n, which yields the exponent n = 1.35 ± 0.04. The dashed line is a similar fit over 0.037 ⩽ T ⩽ 0.3 K, yielding n = 1.12 ± 0.14. The inset shows a plot of T/λ1 (≡T1T) versus T 1.12 with a linear fit that yields the T = 0 intercept T/λ1 = (0.7 ± 4.2) × 10−3 K μs.

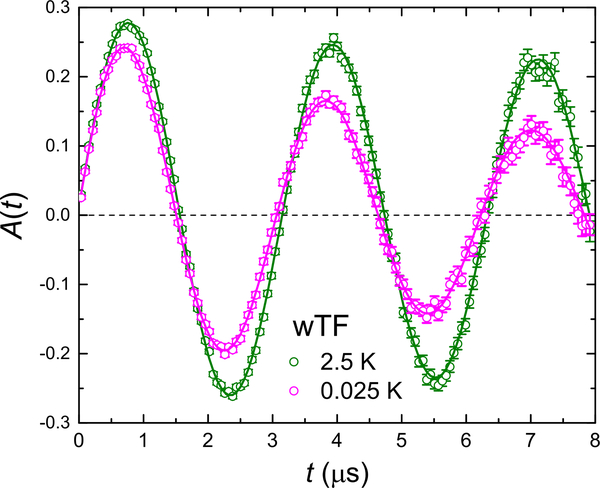

Figure 5 shows wTF-μSR asymmetry spectra above and far below Tc. The data were fit to the following sum of two exponentially damped precessing terms due to the sample and an undamped temperature-independent precessing component due to muons that missed the sample:

| (3) |

where ϕ is the initial phase of the muon spin polarization P(0) relative to the x direction. The fits yield A1 + A2 = 0.176(4) and 0.165(4) for T = 2.5 and 0.025 K, respectively. The lower-critical field Hc1(T) of UTe2 is unknown, but presumably quite small. The smaller value of AS at 0.025 K may be due to partial flux expulsion, if Hc1(T = 0.025 K) is somewhat larger than the applied 23 Oe local field. Regardless, the small difference between AS at the two temperatures indicates that the magnetic volume sensed by the muon above and below Tc is essentially the same. Consequently, the superconductivity must reside in spatial regions where there are magnetic fluctuations.

FIG. 5.

Weak TF-μSR asymmetry spectra recorded for H = 23 Oe. The solid curves are fits to Eq. (3).

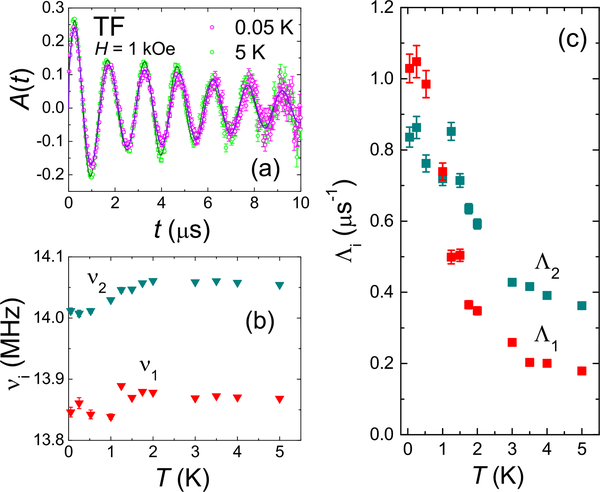

Figure 6(a) shows representative TF-μSR asymmetry spectra recorded for H = 1 kOe. Fourier transforms of these TF-μSR spectra indicate an evolution of the internal magnetic field distribution with decreasing temperature [18]. Once again the TF signals were fit to the sum

| (4) |

where ψ is the initial phase of the muon spin polarization P(0) relative to the z direction. The exponentially damped terms account for muons stopping at the two sites in the sample, and the Gaussian-damped term accounts for muons that missed the sample. The precession frequencies νi are a measure of the local field Bμ,i sensed by the muon at the two stopping sites, where νi = (γμ/2π)Bμ,i and γμ/2π is the muon gyromagnetic ratio. The applied 1 kOe field induces a polarization of the U-5f moments and a corresponding relative muon frequency shift (Knight shift), which is different for the two muon sites. Fits of the TF asymmetry spectra to Eq. (4) were performed assuming the background term is independent of temperature, and the ratio of the asymmetries A1, A2, and AB are the same as determined from the analysis of the ZF asymmetry spectra.

FIG. 6.

(a) TF-μSR asymmetry spectra at T = 0.05 and 5 K for a magnetic field H = 1 kOe applied parallel to the z direction, displayed in a rotating reference frame frequency of 13.15 MHz. The solid curves are fits to Eq. (4). Temperature dependence of the fitted (b) muon spin precession frequencies, and (c) TF relaxation rates.

The temperature dependence of ν1 and ν2 is shown in Fig. 6(b). Below T ~ 1.6 K there is a decrease in ν1 and ν2 compatible with the estimate of ~0.2% for the SC diamagnetic shift from the relation [19] −4πM = (Hc2 − H)/[1.18(2κ2 − 1) + n], with Hc2 = 200 kOe, H = 1 kOe, κ = 200, and n ⩽ 1. However, the temperature dependence of the TF relaxation rates Λ1 and Λ2 [see Fig. 6(c)] do not exhibit a significant change in behavior at Tc. This indicates that Λ1 and Λ2 are dominated by the internal magnetic field distribution associated with the magnetic fluctuations and the London penetration depth λL is quite long—as is the case for other uranium-based superconductors in which λL ≳ 10 000 Å [20]. The magnetic fluctuations may also contribute to ν1(T) and ν2(T) by adding or opposing the SC diamagnetic shift.

In conclusion, we observe a gradual slowing down of magnetic fluctuations with decreasing temperature below 5 K, consistent with weak FM fluctuations approaching a magnetic instability. However, we find no evidence for magnetic order down to 0.025 K. Hence there is no phase transition to FM order in UTe2 preceding or coinciding with the onset of superconductivity. The magnetic volume fraction is not significantly reduced below Tc, indicating that the superconductivity coexists with the fluctuating magnetism. Lastly, we note that because the relaxation rate of the ZF-μSR signal below 5 K is dominated by dynamic local fields, it is not possible to determine whether spontaneous static magnetic fields occur below Tc due to time-reversal symmetry breaking in the SC state.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of TRIUMF’s Centre for Molecular and Materials Science for technical assistance. J.E.S. acknowledges support from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Research at the University of Maryland was supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award No. DE-SC0019154, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative through Grant No. GBMF4419. S.R.S. acknowledges support from the National Institute of Standards and Technology Cooperative Agreement 70NANB17H301.

References

- [1].Aoki D, Huxley A, Ressouche E, Braithwaite D, Flouquet J, Brison JP, Lhotel E, and Paulsen C, Nature (London) 413, 613 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Huy NT, Gasparini A, de Nijs DE, Huang Y, Klaasse JCP, Gortenmulder T, de Visser A, Hamann A, Görlach T, and Löhneysen H. v., Phys. Rev. Lett 99, 067006 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Saxena SS, Agarwal P, Ahilan K, Grosche FM, Haselwimmer RKW, Steiner MJ, Pugh E, Walker IR, Julian SR, Monthoux P, Lonzarich GG, Huxley A, Sheikin I, Braithwaite D, and Flouquet J, Nature (London) 406, 587 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Akazawa T, Hidaka H, Fujiwara T, Kobayashi TC, Yamamoto E, Haga Y, Settai R, and Ōnuki Y, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 16, L29 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fay D and Appel J, Phys. Rev. B 22, 3173 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- [6].Roussev R and Millis AJ, Phys. Rev. B 63, 140504(R) (2001). [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kirkpatrick TR, Belitz D, Vojta T, and Narayanan R, Phys. Rev. Lett 87, 127003 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tateiwa N, Haga Y, and Yamamoto E, Phys. Rev. Lett 121, 237001 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ran S, Eckberg C, Ding Q-P, Furukawa Y, Metz T, Saha SR, Liu I-L, Zic M, Kim H, Paglione J, and Butch NP, Science 365, 684 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Aoki D, Nakamura A, Honda F, Li D, Homma Y, Shimizu Y, Sato YJ, Knebel G, Brison J-P, Pourret A, Braithwaite D, Lapertot G, Niu Q, Vališka M, Harima H, and Flouquet J, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 88, 043702 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tokunaga Y, Sakai H, Kambe S, Hattori T, Higa N, Nakamine G, Kitagawa S, Ishida K, Nakamura A, Shimizu Y, Homma Y, Li D, Honda F, and Aoki D, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 88, 073701 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [12].Morris G and Heffner R, Physica B 326, 252 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sakarya S, Gubbens PCM, Yaouanc A, Dalmas de Réotier P, Andreica D, Amato A, Zimmermann U, van Dijk NH, Brück E, Huang Y, and Gortenmulder T, Phys. Rev. B 81, 024429 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schenck A, Muon Spin Rotation Spectroscopy: Principles and Applications in Solid State Physics (Adam Hilger Ltd., Bristol and Boston, 1985). [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ikeda S, Sakai H, Aoki D, Homma Y, Yamamoto E, Nakamura A, Shiokawa Y, Haga Y, and Onuki Y, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 75, 116 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moriya T, J. Magn. Magn. Mater 100, 261 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ishigaki A and Moriya T, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 65, 3402 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- [18]. See Supplemental Material at http://link.aps.org/supplemental/10.1103/PhysRevB.100.140502. for Fourier transforms of representative TF-μSR asymmetry spectra for H = 1 kOe.

- [19].Abrikosov AA, J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2, 199 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gross F, Andres K, and Chandrasekhar BS, Physica C 162–164, 419 (1989). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.