Abstract

Wear particles from orthopedic implants cause aseptic loosening, the leading cause of implant revisions. The particles are phagocytosed by macrophages leading to activation of the nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and release of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) which then contributes to osteoclast differentiation and implant loosening. The mechanism of inflammasome activation by orthopedic particles is undetermined but other particles cause the cytosolic accumulation of the lysosomal cathepsin-family proteases which can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Here, we demonstrate that lysosome membrane disruption causes cathepsin release into the cytoplasm that drives both inflammasome activation and cell death but that these processes occur independently. Using wild-type and genetically-manipulated immortalized murine bone marrow derived macrophages and pharmacologic inhibitors, we found that NLRP3 and gasdermin D are required for particle-induced IL-1β release but not for particle-induced cell death. In contrast, phagocytosis and lysosomal cathepsin release are critical for both IL-1β release and cell death. Collectively, our findings identify the pan-cathepsin inhibitor Ca-074Me and the NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 as therapeutic interventions worth exploring in aseptic loosening of orthopedic implants. We also found that particle-induced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in pre-primed macrophages and cell death are not dependent on pathogen-associated molecular patterns adherent to the wear particles despite such pathogen-associated molecular patterns being critical for all other previously studied wear particle responses, including priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Keywords: aseptic loosening, cathepsins, gasdermin D, inflammasome, lysosomal disruption

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Aseptic loosening remains a prevalent complication of total joint arthroplasties and accounts for approximately 25% of revisions.1 Aseptic loosening is caused by wear particle generation which correlates with degree of osteolysis.2,3 Similar mechanisms appear to induce osteolysis in response to all orthopedic wear particles,4 except for cobalt-chromium corrosion products that cause a distinct type of implant failure. Macrophages phagocytose wear particles5 and then release interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and other proinflammatory cytokines that induce osteoclastogenesis.4,6–9 Thus, particle-induced osteoclastogenesis in vitro and particle-induced osteolysis in mice are blocked by anti-IL-1β antibodies or IL-1Ra6,8,10 and an IL-1Ra polymorphism associates with aseptic loosening.11

In macrophages, cleavage of pro-IL-1β to active IL-1β is accomplished by caspase-1 whose activation is regulated by multi-protein inflammasomes.12 The nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome mediates responses to crystals and other particles,12 including orthopaedically-relevant particles.13–19 Caspase-1 activation by NLRP3 inflammasomes requires two-steps to first prime, and then activate, the inflammasome.12 Priming of NLRP3 inflammasomes can be induced by multiple inflammatory stimuli including pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or lipoteichoic acid12 and by PAMPs adherent to titanium particles.19 Priming results in upregulation of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β.12,19 Activation is then required for NLRP3 to recruit the adapter protein apoptosis-associated speck like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) which oligomerizes and activates caspase-1.20

The leading model of particle-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation involves destabilization of lysosomal membranes and release of cathepsins and other lysosomal components into the cytosol16,21–25 which can then induce formation of plasma membrane pores and potassium efflux resulting in inflammasome activation.26 For example, silica crystals induce swelling of macrophage lysosomes and the lysosomal V-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1 inhibits silica-induced IL-1β release.23 Additionally, particle-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β release are reduced by pan-cathepsin inhibition.16,21,22,24,27 Multiple cathepsins likely act re-dundantly as deletion of single cathepsins does not have a significant effect compared with pan-cathepsin inhibitors or deletion of multiple cathepsins.21,24,25

Cell death is another common consequence of lysosome destabilization and inflammasome activation.21,22,25,27 Cell death of macrophages and other cell types in peri-prosthetic tissue from aseptic loosening patients has also been noted.28–32 Cell death in response to monosodium urate or silica crystals is inflammasome-independent but there is conflicting data on whether it depends on cathepsins.25,27 Orthopedic particles that induce aseptic loosening can also induce macrophage cell death33,34 but the mechanisms have not been studied.

Gasdermin D is a key mediator of inflammasome-dependent cell death.35 Caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin D to generate N-terminal products that oligomerize to form plasma membrane pores and mediate both IL-1β efflux and pyroptotic cell death.35 While gasdermin D deficiency ameliorates auto-inflammatory conditions in vivo,35 effects of gasdermin D on particle-induced osteolysis have not been studied.

This study tested whether the model of particle phagocytosis, lysosomal destabilization, lysosomal cathepsin release and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome to cleave IL-1β and gasdermin D and induce cell death is applicable to titanium particles, as an example of orthopedic particles that induce aseptic loosening. Safe and effective inhibitors exist for cathepsins and the NLRP3 inflammasome and we therefore also determined whether they prevent particle-induced IL-1β release and cell death and therefore might have applications in treating aseptic loosening.

2 |. METHODS

Detailed methods are included in the Supplementary Materials. In brief, immortalized bone marrow derived macrophages (iBMDMs), either wild-type or lacking specific genes (NLRP3, TLR2, TLR4, or gasdermin D), were primed with ultrapure LPS and then incubated with specific inhibitors of phagocytosis (cytochalasin D), lysosomal V-ATPase (bafilomycin), cathepsins (Ca-074Me and K777), the NLRP3 inflammasome (MCC950), caspases (ZVAD), or their respective vehicles. After 15 minutes, macrophages were stimulated with 500 μL of complete media with indicated concentrations of particles, positive control (ATP, 5 mM), or without stimuli. Except as noted, culture media and cell lysates were collected 8 hours after particle addition. Levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. IL-1β bioactivity was measured using HEK-Blue IL-1R cells as recommended by manufacturer (Cat#hkb-il1r; InvivoGen). Western blotting assessed abundance and cleavage of pro-IL-1β, gasdermin D, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and oligomerization of ASC. Lytic cell death was assessed by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release measured according to manufacturer instructions (Pierce; Cat#88954) and was normalized to maximal LDH release from lysed macrophages (1% Triton X-100, Cat#X100; Sigma-Aldrich). Cell viability was assessed by measuring resazurin reduction (44 μM, Cat#R7107; Sigma-Aldrich) during a 1-hour incubation. Cytosol was collected after permeabilizing the plasma membrane but not intracellular organelle membranes, and cathepsin levels were then measured biochemically. Particle phagocytosis was measured in bright-field images (LSM510 laser scanning microscope, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using an automated algorithm developed for this purpose (MATLAB, Mathworks, Natick, MA) on 15 randomly-selected images from each group (five fields each from three independent experiments). The algorithm counts particles within cell borders determined with a Canny filter.

2.1 |. Data Analysis

Individual points on line graphs represent means and standard deviations of three or more independent experiments each with three culture wells per group. In bar graphs, symbols depict each of three to six independent experiments, each representing the mean of three culture wells per group. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism8 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Since all data were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test) and of equal variance (Brown-Forsythe test), significance (P < .05) was evaluated by one-way or two-way analysis of variance with Holm-Sidak post-hocs.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Titanium particles induce the release of mature IL-1β and cell death by macrophages independently of adherent PAMPs

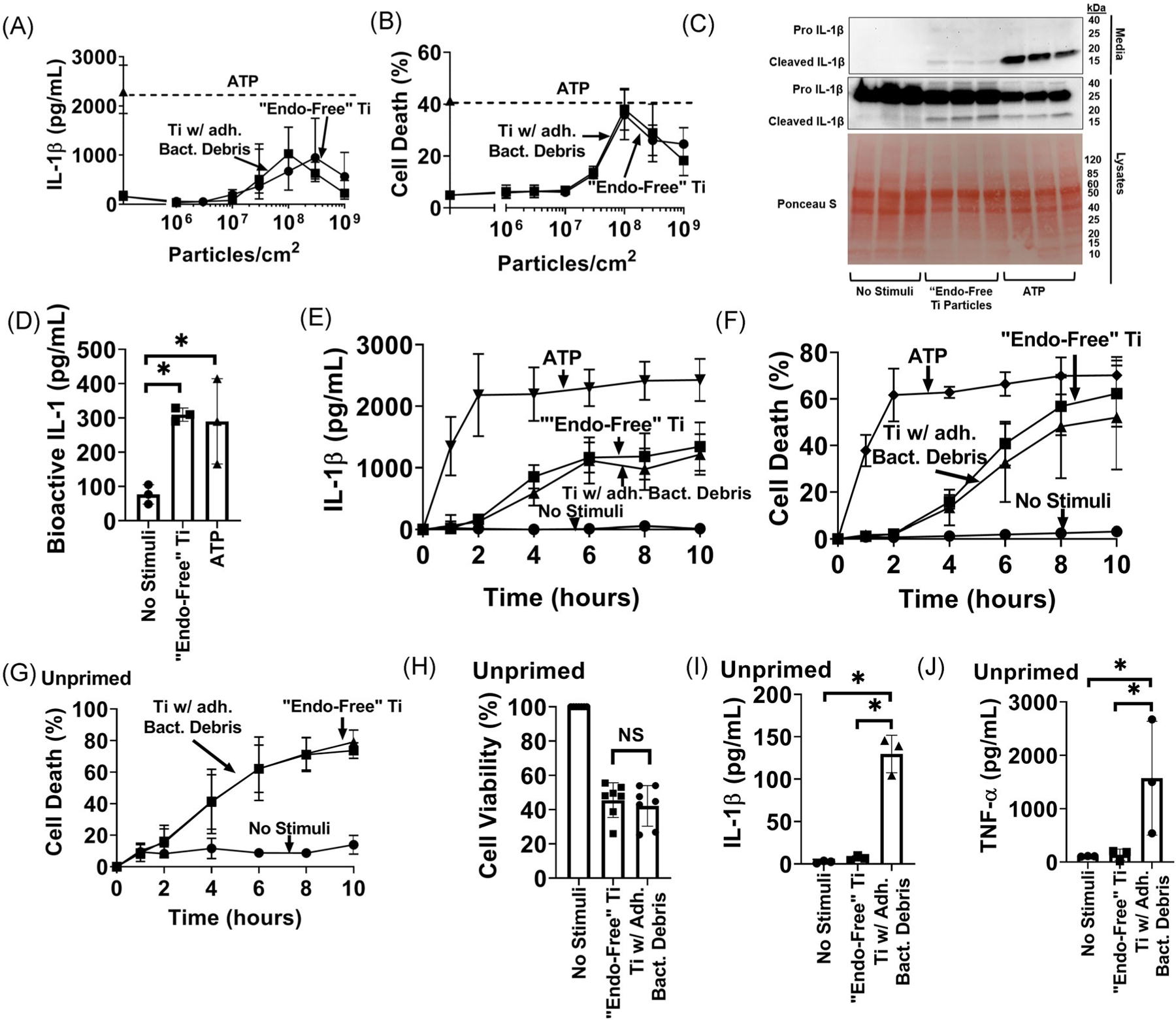

We previously showed that adherent PAMPs and their cognate TLRs are required for priming of macrophage NLRP3 inflammasomes by titanium particles.19 This study examines activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and therefore focuses on macrophages that were LPS-primed before exposure to particles. As a soluble non-particle positive control, we used extracellular ATP, which targets plasma membrane P2X7 receptor cation channels to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. We compared activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and found that IL-1β release is induced with similar dose responses by both “endotoxin-free” titanium particles and titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris (Figure 1A). Both types of particles also showed similar dose responses when LDH release was measured to assess lytic cell death (Figure 1B), another typical consequence of NLRP3 inflammasome activation.21,22,25,27 Both types of particles induced maximal release of IL-1β and LDH at a concentration of 108 particles per cm2, which was therefore used for all subsequent experiments, except where indicated. Since macrophage death might also release unprocessed pro-IL-1β, we confirmed that titanium particles induce release of processed IL-1β by Western blotting and IL-1 bioassay (Figure 1C,D).

FIGURE 1.

Titanium particles induce the release of mature interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and cell death by macrophages independently of adherent pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs): A, B, immortalized bone marrow derived macrophages (iBMDMs) were primed with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (4 hours, 4 μg/mL) and then incubated for 8 hours without additional stimuli or with the indicated doses of either “endotoxin-free” titanium particles or titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (A) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and cell death was measured by (B) lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. C, iBMDMs (2.5 × 105cells/cm2) were primed with LPS (4 hours, 4 μg/mL) and then incubated for 8 hours without additional stimuli, with “endotoxin-free” titanium particles (108/cm2), or with 5 mM ATP as a positive control. Culture media proteins between 10 and 50 kDa were concentrated 8-fold and then resolved on western blots. Concentrated culture media and cell lysates were blotted for IL-1β and lysate blots were stained with Ponceau S to assess protein loading. D, iBMDMs were primed with LPS (4 hours, 4 μg/mL) and then incubated for 8 hours without additional stimuli, with “endotoxin-free” titanium particles (108/cm2), or with 5 mM ATP as a positive control. IL-1 bioactivity in culture media was measured with HEK-Blue sensor cells. E, F, iBMDMs were primed with LPS (4 hours, 4 μg/mL) and then incubated for the indicated times without additional stimuli or with either “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris or ATP. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (E) ELISA and cell death was measured by (F) LDH assay. G, Unprimed iBMDMs were incubated for the indicated times without stimuli or with either “endotoxin-free” titanium particles or titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris. Cell death was assessed by LDH assay. H-J, Unprimed iBMDMs were incubated for 8 hours without stimuli or with either “endotoxin-free” titanium particles or titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris. Cell viability was assessed by measuring (H) resazurin reduction. IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in the culture media were measured by (I, J) ELISA. A, B, and E-G, Mean ± SD of three independent experiments. C, Representative images. Each image includes three samples obtained from separate culture wells per group. D, H-J, Mean ± SD of three to six independent experiments (symbols). *P < .05 as calculated from one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparisons and Sidak correction. All experiments included triplicate culture wells per group and each culture well was assayed in triplicate

To further examine the relationship between IL-1β release and cell death, we studied their kinetics in response to wear particles or extracellular ATP. In pre-primed cells, IL-1β and LDH were released concurrently, with maximal levels after approximately 8 hours of particle stimulation, and kinetics were not affected by bacterial debris on the particles (Figure 1E,F). As expected, ATP, as a soluble inflammasome activator, elicited more rapid IL-1β release and cell death (both near maximal within 2 hours) than the wear particles. The kinetics of particle-induced LDH release was also not affected by LPS priming (Figure 1F,G). To confirm that LDH release is coordinated with decreased viability, macrophage viability was assessed by resazurin reduction. Both particles coordinately decreased resazurin reduction and increased LDH release at the eight hour timepoint (Figure 1G,H). As expected, release of IL-1β by unprimed macrophages was induced by particles with adherent bacteria but not by “endotoxin-free” particles (Figure 1I). Similarly, release of TNFα by unprimed macrophages, which like priming requires nuclear factor-κB signaling,36 was induced by particles with adherent bacteria but not by “endotoxin-free” particles (Figure 1J). In contrast to our previous findings on priming of NLRP3 inflammasomes,19 results in Figure 1 collectively show that activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and induction of cell death by titanium particles is independent of the PAMPs known to adhere to titanium particles.

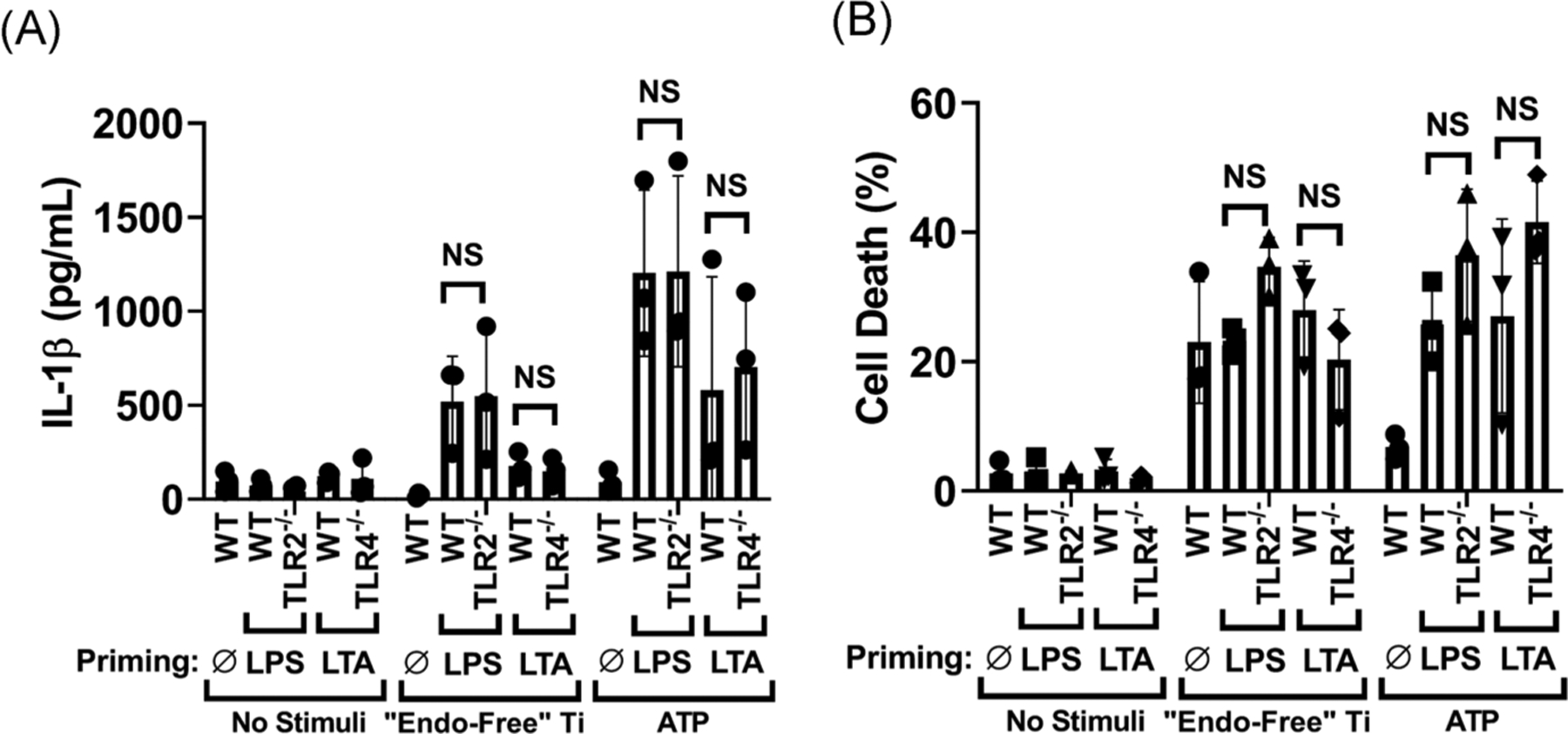

3.2 |. Titanium particle-induced inflammasome activation is independent of TLR2 and TLR4

It was hypothesized that DAMPs, acting through TLR2 and TLR4 but independently of PAMPs, contribute to aseptic loosening by activating NLRP3 inflammasomes.37,38 To test this hypothesis, we evaluated whether TLR2 or TLR4 contribute to release of IL-1β or LDH induced by titanium particles in pre-primed macrophages. Prior to incubation with particles, NLRP3 inflammasomes in macrophages from TLR2−/− or TLR4−/− mice were primed with PAMPs specific for non-deleted TLRs. In those pre-primed macrophages, deletion of either TLR2 or TLR4 did not significantly alter the release of IL-1β or LDH induced by “endotoxin-free” titanium particles or, as expected, by ATP (Figure 2A,B). As an additional control, priming of NLRP3 inflammasomes with cognate PAMPs was blocked by deletion of TLR2 or TLR4 (Figure S2). The results in Figure 2 demonstrate that DAMPs do not act through TLR2 and TLR4 independently of PAMPs to activate NLRP3 inflammasomes.

FIGURE 2.

Titanium particle-induced inflammasome activation is independent of TLR2 and TLR4. A, B, Wild-type, TLR2−/−, or TLR4−/− iBMDMs were primed with PAMPs that activate non-deleted TLRs (LPS for TLR2−/− and lipoteichoic acid [LTA] for TLR4−/−) or used unprimed (Ø) and then incubated for 8 hours without additional stimuli, with 108/cm2 of “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP. IL-1β in the culture media was measured by (A) ELISA and cell death was measured by (B) LDH assay. Bars represent means ± SD of three independent experiments (symbols). All experiments included triplicate culture wells per group and each culture well was assayed in triplicate. Significance was calculated by two-way ANOVA with Sidak correction. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; iBMDM, immortalized bone marrow derived macrophage; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PAMP, pathogen associated molecular pattern

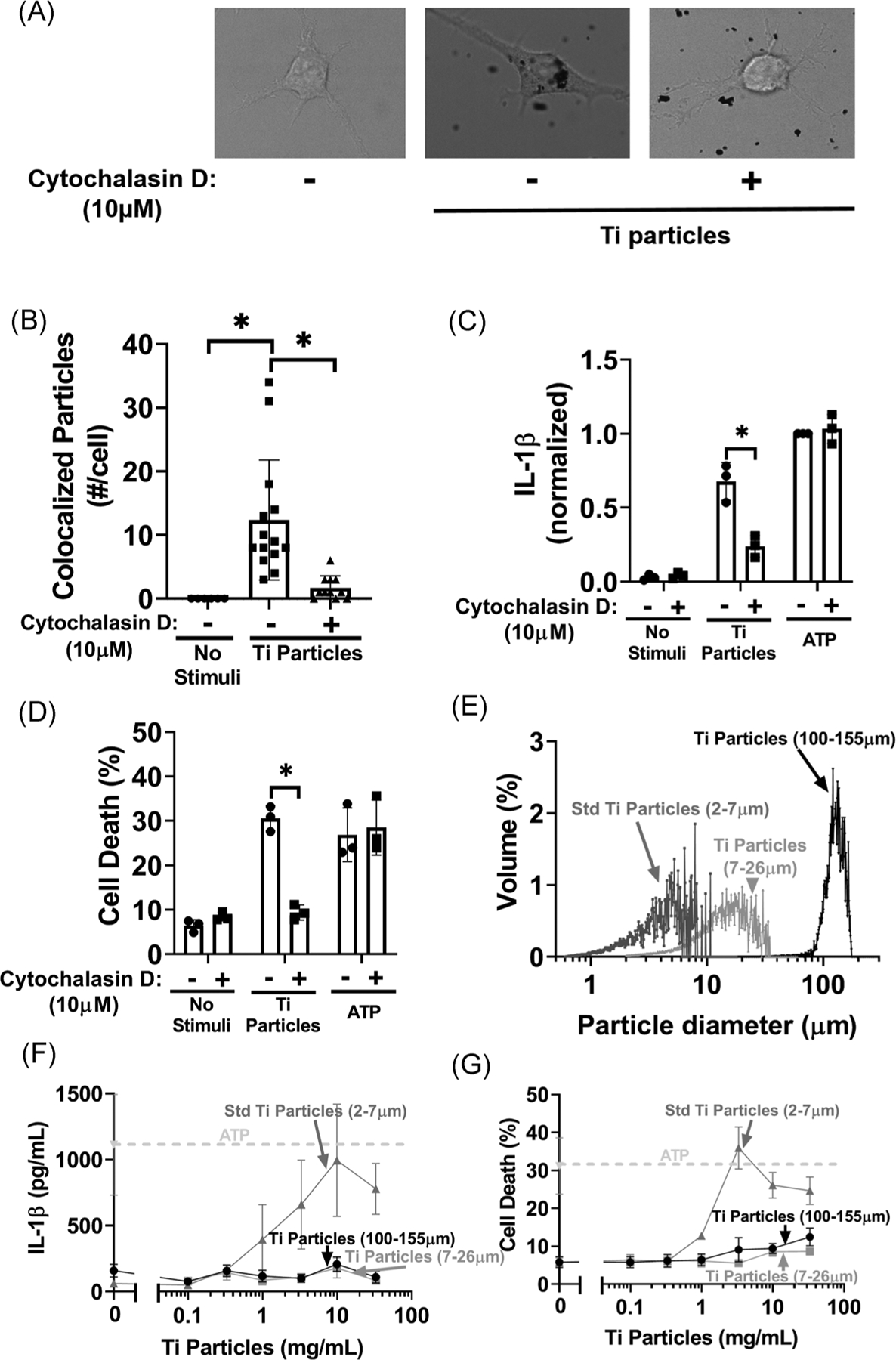

3.3 |. Phagocytosis is required for induction of both IL-1β release and cell death by titanium particles

We confirmed that macrophages internalize substantial numbers of titanium particles and that particle internalization is reduced by inhibition of phagocytosis with cytochalasin D (Figure 3A,B). We then tested whether inhibition of phagocytosis suppresses the ability of the particles to induce IL-1β release and cell death. Cytochalasin D reduced particle-induced IL-1β release by 64% and completely prevented particle-induced cell death (Figure 3C,D). This inhibition is specific to particle-induced responses as cytochalasin D did not alter ATP-induced responses (Figure 3C,D). Because cytochalasin D, as an inhibitor of actin polymerization, affects cellular motility responses independently of phagocytosis, we determined whether larger non-phagocytosable titanium particles (7–26 μm and 100–155 μm diameters; Figure 3E) induce IL-1β release and cell death. Compared with phagocytosable titanium particles (2–7 μm diameters, Figure 3E), larger titanium particles induced little IL-1β release or cell death (Figure 3F,G). Collectively, the results in Figure 3 show that phagocytosis is required for induction of IL-1β release and cell death by appropriately-sized particles; and larger particles limited to the extracellular compartments do not elicit inflammasome or cell death responses via possible interaction with cell surface components.39

FIGURE 3.

Phagocytosis of titanium particles is critical for IL-1β release and cell death. A, B, Unprimed wild-type iBMDMs were pre-incubated with either vehicle or cytochalasin D for 15 minutes and then incubated for 2 hours without additional stimuli or with 107/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles. Phagocytosis of the particles was assessed by (A) confocal microscopy and (B) quantified in 15 randomly selected cells (five chosen from three independent experiments) using a MATLAB algorithm trained on an independent training set. C, D, LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were pre-incubated with either vehicle or cytochalasin D for 15 minutes and then incubated for 8 hours without stimuli, with 108/cm2 “Endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (C) ELISA and cell death was measured by (D) LDH assay. E, Titanium particle samples from each size group were binned by particle diameter using a Coulter counter. F, G, LPS-primed iBMDMs were incubated without stimuli or with the indicated doses of “endotoxin-free” titanium particles of varied sizes: 7 to 26 μm or 100 to 155 μm. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (F) ELISA and cell death was measured by (G) LDH assay. Data for the standard sized titanium particles (2–7 μm) is reproduced from Figure 1C,D for comparison. A, Representative images from 15 images per group pooled from three independent experiments. B, Bars represent mean ± SD of 15 cells (symbols) pooled from three independent experiments. C, D, Bars represent means ± SD of three independent experiments (symbols). *P < .05 as calculated from two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Sidak correction. F, G, Symbols represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. All experiments included triplicate culture wells per group and each culture well was assayed in triplicate. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; iBMDM, immortalized bone marrow derived macrophage; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide

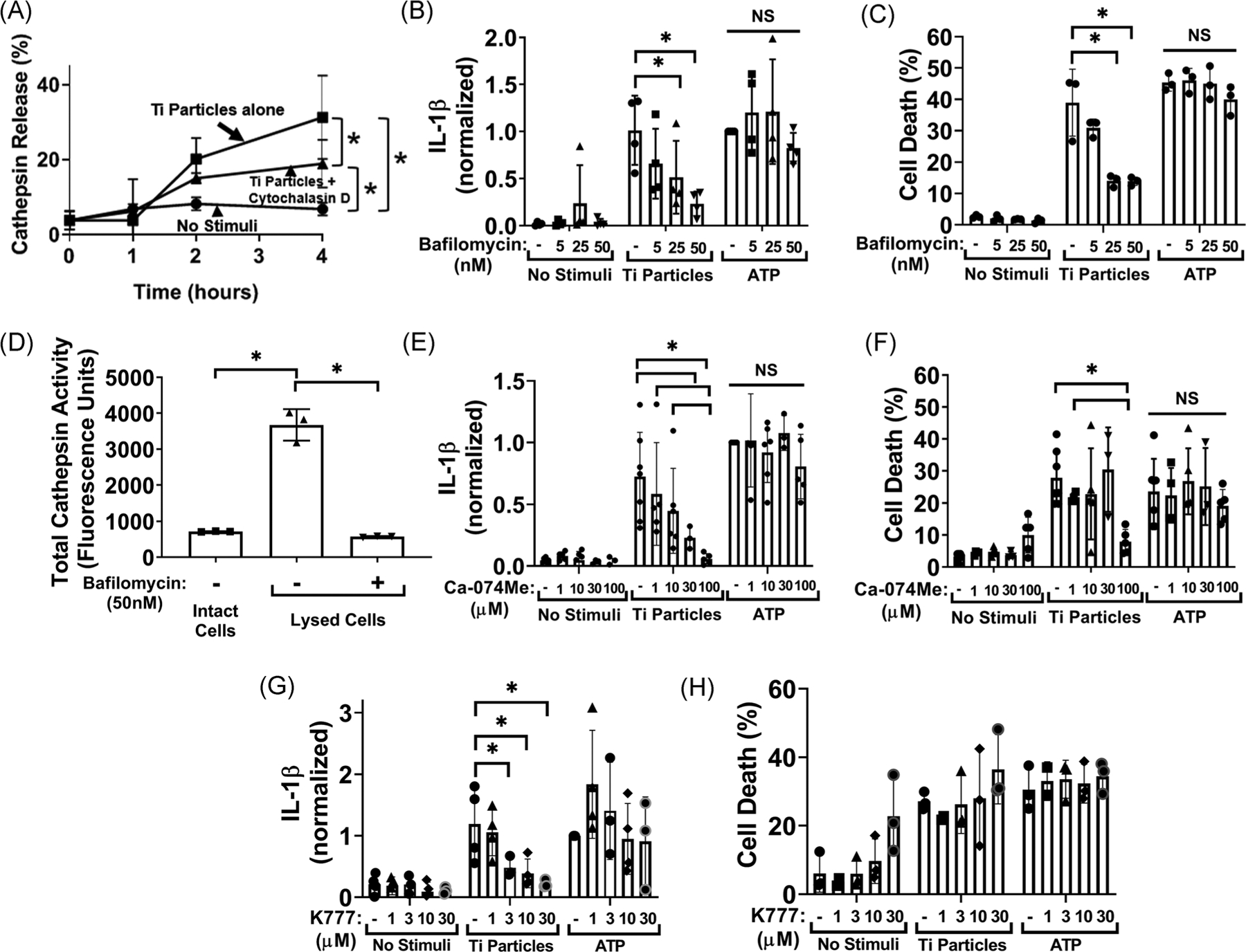

3.4 |. Lysosome function and release of lysosomal cathepsins into the cytosol are required for titanium particles to induce cell death and release of IL-1β

Having demonstrated that titanium particles are phagocytosed by macrophages, we next tested the role of lysosomes in titanium particle-induced inflammation. We therefore assessed lysosomal disruption by measuring the activity of normally intra-lysosomal cathepsins released into the cytosol. Titanium particles induced significantly higher levels of cytosolic cathepsin activity consistent with release of lysosomal components (Figure 4A). Particle-induced cathepsin release was inhibited 40% by cytochalasin D suggesting that phagocytosis is upstream of and, at least in part, required for cathepsin release (Figure 4A). We next determined whether inhibition of lysosomal homeostatic function by blocking acidification with the lysosomal V-ATPase inhibitor,40 bafilomycin A1, affects IL-1β release and cell death. Bafilomycin A1 dose-dependently decreased particle-induced IL-1β release by up to 77% and cell death by up to 64% (Figure 4B,C). A possible consequence of lysosomal alkalization is loss of activity of pH sensitive enzymes such as cathepsins.41 Bafilomycin A1 reduced total cathepsin activity by 84% (Figure 4D). To determine whether cathepsins contribute to particle-induced IL-1β release or cell death, we measured effects of the pan-cathepsin inhibitor Ca-074Me.24,25 Ca-074Me reduced titanium particle-induced IL-1β release by 92% and cell death by 69% at the highest dose tested (Figure 4E,F). K777, a pan-cathepsin inhibitor with distinct specificities for individual cathepsins,24,25 also dose-dependently reduced titanium particle-induced IL-1β release by up to 79% but had little effect on particle-induced cell death (Figure 4G,H). The effects of bafilomycin A1, Ca-074Me, and K777 are specific for particle responses because, as expected,23 none of them altered ATP responses (Figures 4B, C, E–H). Collectively, the results in Figure 4 demonstrate that lysosome function and release of lysosomal cathepsins into the cytosol are required for titanium particles to induce release of IL-1β by macrophages and their cell death.

FIGURE 4.

Lysosomal cathepsins are essential for induction of IL-1β release by the titanium particles but dispensable for particle-induced cell death (A) LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were pre-incubated with vehicle or cytochalasin D (10 μM) for 15 minutes and then incubated without stimuli, or with 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles for the indicated times. Cathepsin activity in the cytosol was measured by activity assay. B, C, LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were pre-incubated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of bafilomycin A1 and then incubated without stimuli, with 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP for 8 hours. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (B) ELISA and cell death was measured by (C) LDH assay. D, Unprimed wild-type iBMDMs were incubated with either vehicle control or 50 nM bafilomycin A1. Total cathepsin activity in intact or digitonin-lysed macrophages was measured by activity assay. E-H, LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were pre-incubated with vehicle, (E, F) Ca-074Me, or (G, H) K777 for 15 minutes and then incubated without stimuli, with 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP for 8 hours. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (E, G) ELISA and cell death was measured by (F, H) LDH assay. A, Symbols represent means ± SD of three independent experiments. B-H, Bars represent means ± SD of three independent experiments (symbols). All experiments included triplicate culture wells per group and each culture well was assayed in triplicate. *P < .05 as calculated from (D) one-way or (B, C, and E-H) two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Sidak correction. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; iBMDM, immortalized bone marrow derived macrophage; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide

3.5 |. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes is required for induction of IL-1β release by titanium particles but is dispensable for particle-induced cell death

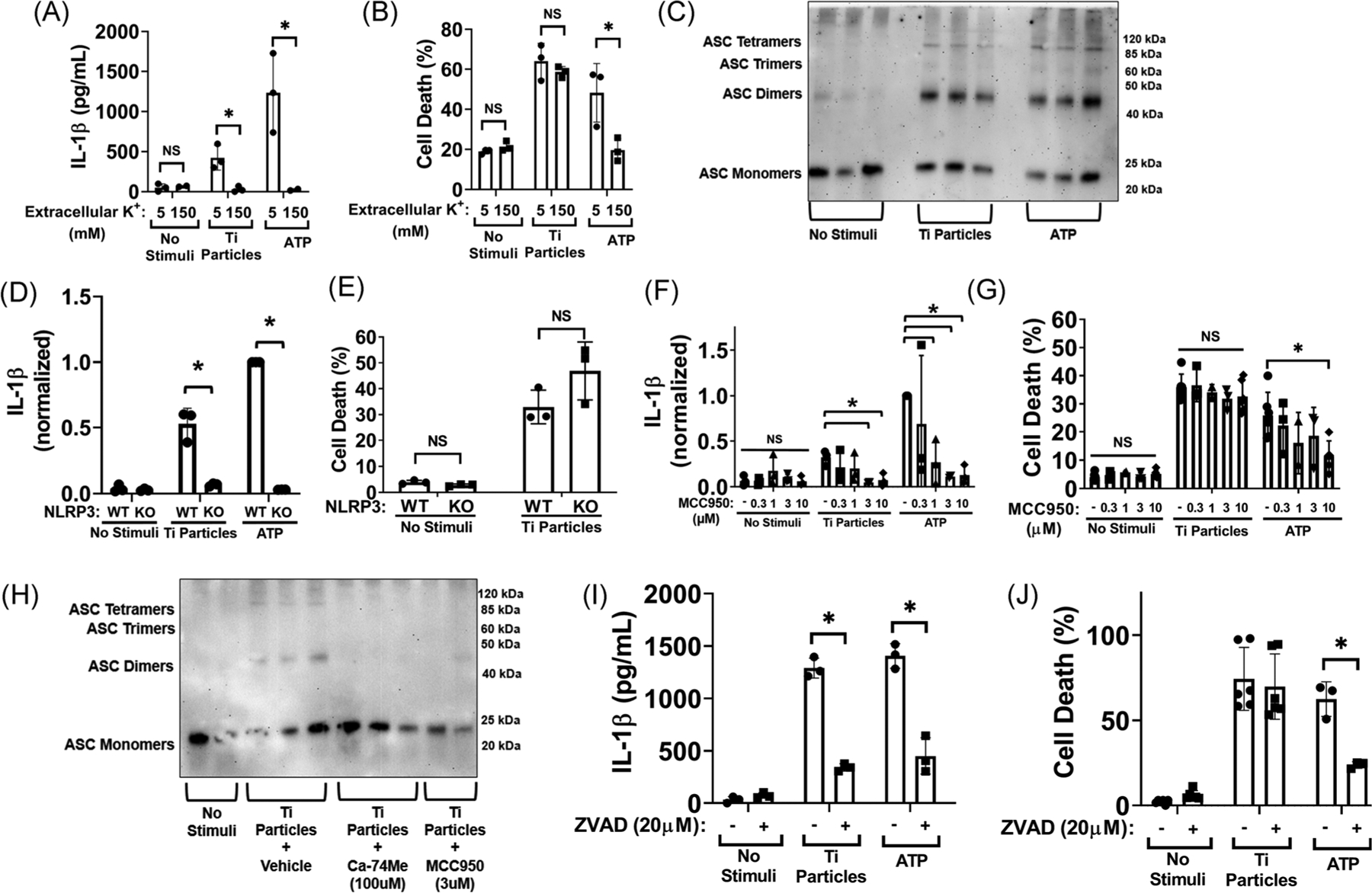

To test the mechanism by which the release of lysosomal contents results in IL-1β release, we examined whether potassium efflux was necessary. High extracellular potassium, which inhibits potassium efflux upstream of inflammasome activation,26 also inhibited titanium particle- and ATP-induced IL-1β release but had no significant effect on titanium particle-induced cell death (Figure 5A,B). We next confirmed that titanium particles induce inflammasome activation by assaying ASC oligomerization via western blotting.20 The substantial increase in intensity of bands representing ASC dimers and multi-mers in cell lysates confirmed that inflammasome activation was induced by both titanium particles and the ATP positive control (Figure 5C). We next confirmed that induction of IL-1β release by particles is blocked in macrophages from NLRP3−/− mice (Figure 5D). In contrast, NLRP3 deletion did not alter cell death induced by titanium particles (Figure 5E). A specific inhibitor of NLRP3 inflammasomes, MCC950,42 was also tested as a potential therapeutic intervention. MCC950 dose-dependently reduced IL-1β release induced by titanium particles or ATP (up to 77% and 87%, respectively) and reduced ATP-induced cell death (up to 51%) but did not alter particle-induced cell death (Figure 5F,G). Consistent with its mechanism as a direct inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome, MCC950 also substantially inhibited particle-induced ASC oligomerization (Figure 5H). This particle-induced cell death was not dependent on classical pyroptotic or apoptotic pathways as a pan-caspase inhibitor did not block the cell death despite having the expected inhibitory effects on IL1β release by inhibiting caspase-1 (Figure 5I,J). Additionally, titanium particle-induced cell death did not result in increased PARP cleavage indicating no appreciable activation of apoptosis (Figure S3). Collectively, the results in Figure 5 demonstrate that activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes is required for induction of IL-1β release, but not induction of cell death, by titanium particles. The pan-cathepsin inhibitor Ca-074Me also markedly suppressed particle-induced ASC oligomerization (Figure 5H) indicating that particle-induced cathepsin release is upstream of, and required for, activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes.

FIGURE 5.

The NLRP3 inflammasome is essential for induction of IL-1β release by the titanium particles but dispensable for particle-induced cell death. A, B, LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were incubated without stimuli, with 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP for 8 hours in media with either standard culture media potassium (5 mM) with added sodium to match osmolality or high potassium (150 mM). IL-1β in culture media was measured by (A) ELISA and cell death was measured by (B) LDH assay (C) LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were incubated without stimuli, with 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP for 8 hours. ASC in cell lysates was cross-linked with DSS and then resolved by western blot. D, E, LPS primed wild-type or NLRP3−/− iBMDMs were incubated without stimuli, with 108/cm2 titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP for 8 hours. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (D) ELISA and cell death was measured by (E) LDH assay. F, G, LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were pre-treated with vehicle or the indicated concentrations of MCC950 for 15 minutes, then incubated without stimuli, with 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP for 8 hours. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (F) ELISA and cell death was measured by (G) LDH assay. H, LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were pre-treated with vehicle, Ca-074Me (100 μM) or MCC950 (3 μM) for 15 minutes and then stimulated with no stimuli or 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles for 8 hours. ASC in cell lysates was cross-linked with DSS and then resolved by Western blot. I, J, LPS-primed wild-type iBMDMs were pre-treated with vehicle or ZVAD (20 μM) for 15 minutes, then incubated for 8 hours without stimuli or with 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP for 1 hour as a positive control. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (I) ELISA and cell death was measured by (J) LDH assay. C, H, Representative images of three independent experiments. Each image includes three samples obtained from separate culture wells per group. A, B, D-G, and I, J, Bars represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments (symbols). All experiments included triplicate culture wells per group and each culture well was assayed in triplicate. *P < .05 as calculated from two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Sidak correction. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing C-terminal caspase recruitment domain; DSS, disuccinimidyl suberate; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; iBMDM, immortalized bone marrow derived macrophage; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide

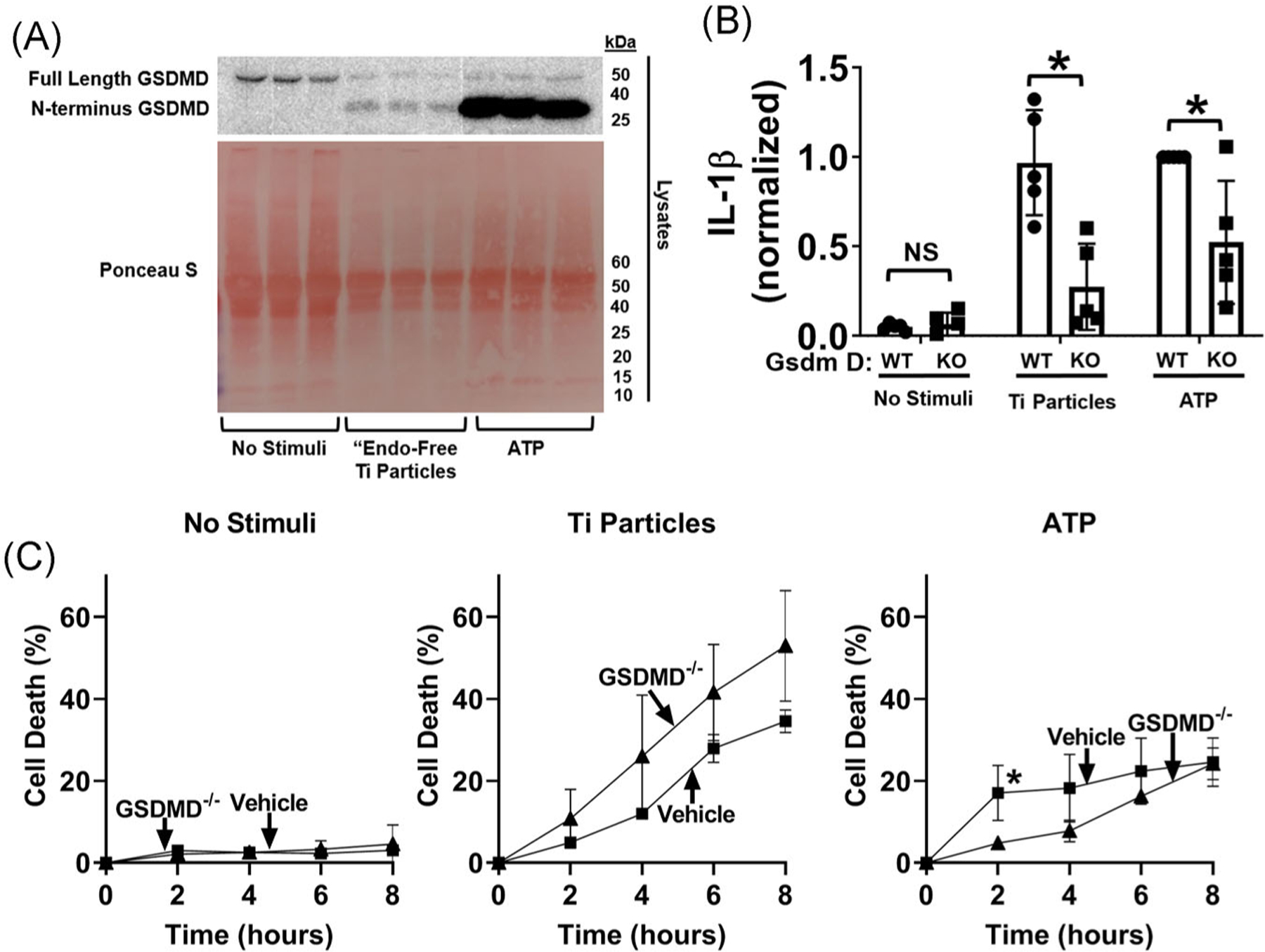

3.6 |. Gasdermin D is required for induction of IL-1β release by titanium particles but is dispensable for particle-induced cell death

Recent studies identified gasdermin D as an additional target which is cleaved by caspase-1 to form plasma membrane pores that can mediate both pre-lytic IL-1β efflux and IL-1β release secondary to pyroptotic lysis.35 Titanium particles, like ATP, induced cleavage of gasdermin D into the pore forming N-terminal fragment (Figure 6A). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of Gasdermin D43 (confirmed in Figure S4) reduced particle-induced IL-1β release by 72% (Figure 6B). In contrast, gasdermin D deletion did not slow the kinetics or decrease the magnitude of cell death induced by titanium particles (Figure 6C). As expected,43 gasdermin D deletion reduced ATP-induced IL-1β release and delayed ATP-induced cell death (Figure 6B,C). Collectively, the results in Figure 6 show that gasdermin D is required for titanium particle induction of IL-1β release, but not induction of cell death.

FIGURE 6.

Gasdermin D is required for induction of IL-1β release by the titanium particles but is dispensable for cell death. A, iBMDMs (2.5 × 105cells/cm2) were primed with LPS (4 hours, 4 μg/mL) and then incubated for 8 hours without additional stimuli or with “endotoxin-free” titanium particles (108/cm2), or for 1 hour with 5 mM ATP as a positive control. Cell lysates were blotted for gasdermin D and protein loading was assessed with Ponceau S staining of the membrane. B, C, LPS-primed wild-type or gasdermin D−/− iBMDMs were incubated without stimuli, with 108/cm2 “endotoxin-free” titanium particles, or with 5 mM ATP for (B) 8 hours or (C) the indicated times. IL-1β in culture media was measured by (B) ELISA and cell death was measured by (C) LDH assay. A, Representative images. Each image includes three samples obtained from separate culture wells per group. B, Bars represent mean ± SD of five independent experiments (symbols). *P < .05 as calculated from one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Sidak correction (C) Symbols represent means ± SD of four independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with wild-type at that timepoint as calculated from two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons and Sidak correction. All experiments included triplicate culture wells per group and each culture well was assayed in triplicate. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; iBMDM, immortalized bone marrow derived macrophage; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide

4 |. DISCUSSION

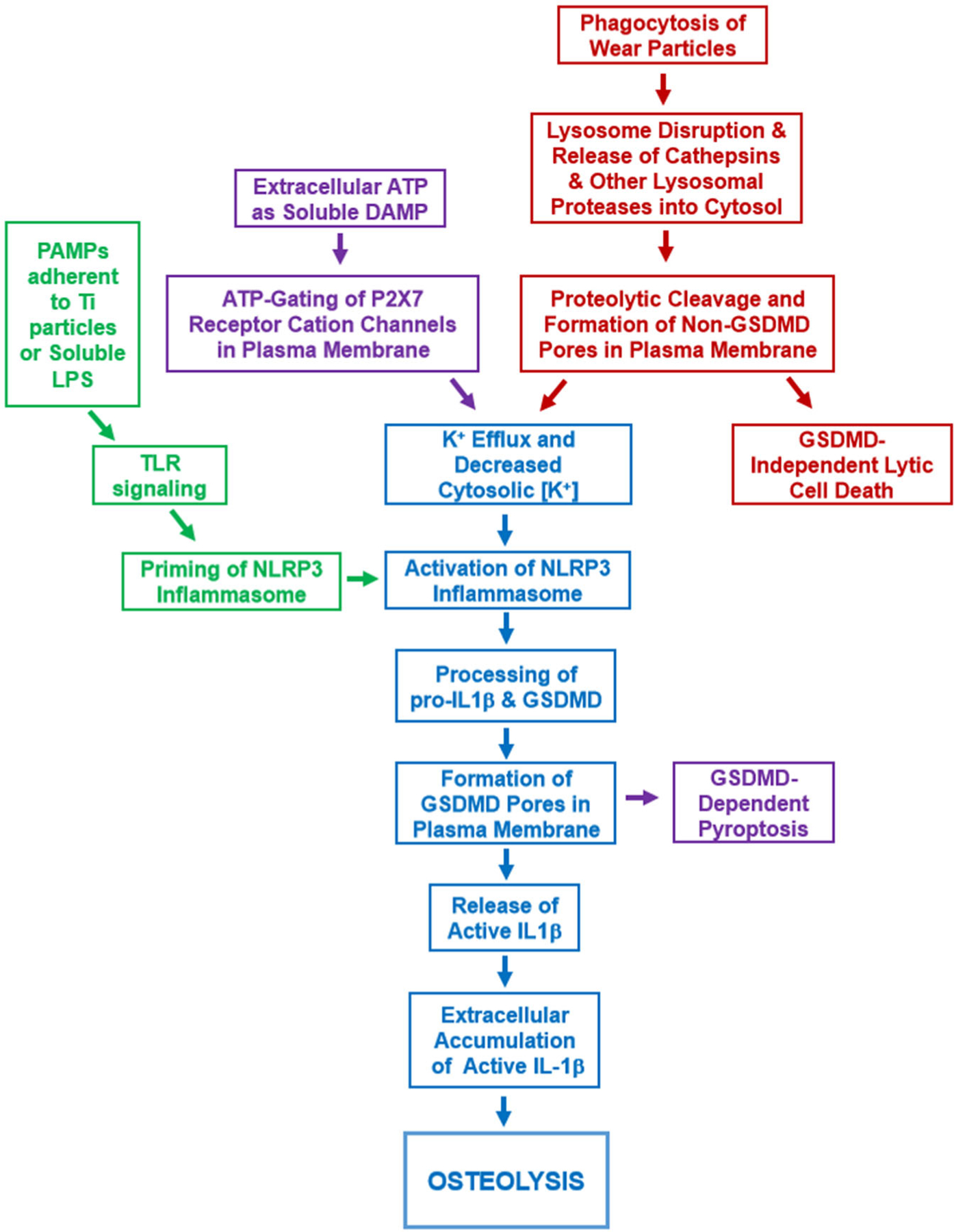

Aseptic loosening, the leading cause of orthopedic implant revision,1 is a macrophage driven inflammatory response to wear particles that includes IL-1β production and subsequent osteoclast differentiation.2–12 Both orthopedic and non-orthopedic particles can induce IL-1β release through phagocytosis, lysosomal damage, and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.16,21,23–25,27 IL-1β release induced by nigericin or ATP is also dependent on plasma membrane pores formed by gasdermin D12 although the role of gasdermin D in particle-induced IL-1β release is less clear.27 In this study, we confirmed that orthopedically-relevant titanium particles induce IL-1β release through similar mechanisms (Figure 7). Thus, iBMDMs phagocytose titanium particles and inhibition of this phagocytosis with either pharmacologic manipulation or particle size prevents the downstream signaling that leads to IL-1β processing and release and to cell death. Those downstream effects of titanium particle phagocytosis include lysosome membrane disruption and release of lysosomal cathepsins into the cytosol. As titanium particles are one of the most chemically stable types of orthopedic wear particles, our results are consistent with the concept that particle-induced lysosomal disruption is primarily due to physical rather than chemical mechanisms.16,44,45 Similarly to other particles,16,21–25 the cathepsins released into the cytosol are important as pan-cathepsin inhibition with Ca-074Me or K77724,25 inhibited activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and the subsequent release of IL-1β. The release of lysosomal contents may contribute to the formation of a potassium permeable pore as particle-induced IL-1β release was dependent on potassium efflux. Bafilomycin A1, a lysosomal V-ATPase inhibitor,40 also inhibited IL-1β release induced by titanium particles. Mechanistically, the effect of bafilomycin A1 may be to inhibit pH-sensitive lysosomal enzymes such as cathepsins. This could occur by direct effects of pH on the cathepsins, by dysregulation of cystatins, or by proteolytic inactivation by other lysosomal proteases that are normally inactive at acidic lysosomal pH.41 The NLRP3 inflammasome was also demonstrated to be critical for IL-1β release as either genetic deletion of NLRP3 or pharmacologic inhibition by MCC95042 blocked titanium particle-induced IL-1β release. Similarly, genetic deletion of gasdermin D blocked titanium particle-induced IL-1β release. These are the first results linking gasdermin D to aseptic loosening of orthopedic implants.

FIGURE 7.

Working model of IL-1β release and cell death induced by the orthopedic wear particles that cause aseptic loosening. See Discussion for details. IL-1β, interleukin-1β

The pathophysiologic role of cell death in particle-induced osteolysis has not been well established although histology and cell death assays indicate it occurs at an increased rate around loose implants compared with synovial tissue obtained during primary orthopedic implantation surgery28–32 and in macrophages exposed to orthopedic particles in culture.33,34 Prior work from our lab found no significant cell death induced by titanium particles at short timepoints (1.5 hours).36 In the current study, we demonstrate that titanium particles induce cell death at longer time points (>4 hours) and that the cell death, like activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes, was potently blocked by inhibition of either phagocytosis or lysosomal acidification (Figure 7). Ca-074Me and K777, pan-cathepsin inhibitors with distinct specificities for individual cathepsins,24 also potently reduced titanium particle-induced activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes but had less effect on particle-induced cell death. Thus, our results are consistent with those of Orlowski24,25 who found that silica crystal-induced IL-1β release is inhibited more potently by Ca-074Me or K777 than silica-induced macrophage cell death. Both sets of results are most likely due to activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes depending on cathepsins, such as cathepsin B, that are relatively more sensitive to Ca-074Me and K777, while macrophage cell death depends on cathepsins that are less sensitive, such as cathepsins C, L and X.21,24,25 The effects of Ca-074Me on responses induced by titanium particles are also consistent with the recently reported effects of Ca-074Me on responses induced by alum particles.27 In that study, Ca-074Me and K777 reduced IL-1β release induced by alum or monosodium urate and cell death induced by monosodium urate but had little effect on alum-induced cell death. We cannot exclude the possibility that the effects of Ca-074Me or K777 on macrophage cell death are due to off-target effects. However, none of the Ca-074Me or K777 doses we used detectably affected ATP-induced macrophage cell death, and Ca-074Me did not have a detectable effect on ATP-induced activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes. Moreover, extensive experiments that combined genetic deletion and siRNA-mediated knockdown showed that multiple cathepsins contribute to induction by silica crystals of both IL-1β secretion and macrophage cell death.24,25 Our results with bafilomycin A1 and the cathepsin inhibitors, taken together with those of Orlowski and colleagues24,25 and Rashidi and colleagues,27 therefore indicate that macrophage cell death induced by multiple types of particles is likely dependent on release of lysosomal cathepsins into the cytosol and that the specific cathepsins that are important appears to vary between different types of particles. Consistent with the later possibility, cell death induced by lysosomal destabilization or by pyroptosis are mediated by different cathepsins and, as a result, are inhibited by Ca-074Me with different potency.21 Future studies will be needed to determine which specific cathepsins are most important for macrophage cell death in response to individual types of particles.

Activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes can cause pyroptotic cell death through caspase-1 cleavage of gasdermin D and its insertion into the plasma membrane.35 However, macrophage cell death induced by titanium particles was not affected by omission of NLRP3 inflammasome priming, genetic deletion of NLRP3, or pharmacological inhibition with MCC950 despite causing the expected inhibitory effect on IL-1β release.13,14,19,42 These findings are consistent with the lack of dependence on inflammasome activation of macrophage cell death induced by various non-orthopedic particles or by direct lysosome destabilizing agents.21,25,27 The titanium particle-induced cell death is also not dependent on other caspases as inhibition with ZVAD did not affect cell death. Gasdermin D also was dispensable for particle-induced death as its CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion did not affect titanium particle-induced cell death but caused the expected inhibitory effect on IL-1β release.35 This suggests that gasdermin D pores are either not involved or redundant in titanium particle-induced cell death. Our results are distinct from findings that gasdermin D is dispensable for both IL-1β release and the concomitant macrophage cell death induced by alum or monosodium urate.27 The pathways of lysosomal cell death overlap substantially with multiple other cell death pathways.46 It is therefore possible that induction of multiple cell death pathways explains why NLRP3 inflammasome activation and gasdermin D are dispensable for titanium particle-induced death despite being activated by titanium particles (Figures 5 and 6). Future studies will consider the possibilities that redundant plasma membrane pores are formed (Figure 7), such as through serine protease cleavage of other gasdermins (as has been demonstrated with granzyme B)47 or release and insertion of lysosmal perforins into the plasma membrane.48 Regardless of their molecular identity, we propose that the putative non-gasdermin D pores (activated by lysosomal proteases released into the cytosol) act as both potassium efflux conduits to induce NLRP3 inflammasome signaling and mediators of lytic cell death by disrupting steady-state plasma membrane mechanisms that maintain ionic and osmotic homeostasis.

A controversy exists as to whether bacterial PAMPs contribute to aseptic loosening of orthopedic implants.4,37,38 Consistent with that possibility, we recently demonstrated that the titanium particles with adherent bacterial debris can prime NLRP3 inflammasomes via activation of cognate TLRs but that “endotoxin-free” titanium particles cannot.19 In contrast, the current study found that activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and macrophage cell death are not dependent on PAMPs adherent to the titanium particles, TLR2, or TLR4. Cell death along with activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in pre-primed cells are therefore the only macrophage responses induced by orthopedic wear particles that we or other investigators found to be independent of PAMPs or TLRs.4,19,33 Thus, activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and/or cell death induced by titanium particles may account for the ~50% of particle-induced osteolysis that is independent of PAMPs, TLR2, TLR4, and TIRAP/Mal in murine calvaria.9,49,50 Wear particle-induced IL-1β release contributes to aseptic loosening6,8,11 and macrophage cell death may also contribute. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition is proposed as a therapy for other inflammatory diseases,42 however, we demonstrated that the NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 blocks IL-1β release but does not alter cell death induced by titanium particles. In contrast, the upstream processes of titanium particle phagocytosis and lysosomal membrane disruption are required for both IL-1β release and cell death. This provides an opportunity to target a wider breadth of the aseptic loosening inflammatory process with a single inhibitor of lysosomal function or cathepsin activity, such as Ca-074Me, which is safe and effective in a wide variety of murine models. A limitation of our study is that the conclusions are based on cell culture studies rather than in vivo models. Future studies are therefore required to determine whether these findings translate into actionable interventions in aseptic loosening.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Derek Abbott for the immortalized gasdermin D−/− macrophages and Dr. Kate Fitzgerald for the wild-type and NLRP3−/− immortalized macrophages. TLR2−/− and TLR4−/− macrophages were obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Macrophage Cell Line Derived from TLR2 Knockout Mice, NR-9457 and Macrophage Cell Line Derived from TLR4 Knockout Mice, NR-9458 respectively. This study was funded in part by grants TL1TR000441, T32AR007505, and R21AR069785 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). Hip, knee & shoulder arthroplasty: 2019 Annual report. Adelaide: AOA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkinson JM, Hamer AJ, Stockley I, Eastell R. Polyethylene wear rate and osteolysis: critical threshold versus continuous dose-response relationship. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2005; 23(3):520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Looney RJ, Boyd A, Totterman S, et al. Volumetric computerized to-mography as a measurement of periprosthetic acetabular osteolysis and its correlation with wear. Arthritis Res Ther. 2001;4(1):59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenfield EM. Do genetic susceptibility, toll-like receptors, and pathogen-associated molecular patterns modulate the effects of wear? Clin Orthop. 2014;472(12):3709–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nich C, Takakubo Y, Pajarinen J, et al. Macrophages—key cells in the response to wear debris from joint replacements. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101(10):3033–3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taki N, Tatro JM, Lowe R, Goldberg VM, Greenfield EM. Comparison of the roles of IL-1, IL-6, and TNFα in cell culture and murine models of aseptic loosening. Bone. 2007;40(5):1276–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenfield EM, Bi Y, Ragab AA, Goldberg VM, Van De Motter RR. The role of osteoclast differentiation in aseptic loosening. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2002;20(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eger M, Hiram-Bab S, Liron T, et al. Mechanism and prevention of titanium particle-induced inflammation and osteolysis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bi Y, Seabold JM, Kaar SG, et al. Adherent endotoxin on orthopedic wear particles stimulates cytokine production and osteoclast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(11):2082–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang S-Y, Wu B, Mayton L, et al. Protective effects of IL-1Ra or vIL-10 gene transfer on a murine model of wear debris-induced osteolysis. Gene Ther. 2004;11(5):483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon A, Kiss-Toth E, Stockley I, Eastell R, Wilkinson JM. Polymorphisms in the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and interleukin-6 genes affect risk of osteolysis in patients with total hip arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):3157–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornung V, Latz E. Critical functions of priming and lysosomal damage for NLRP3 activation. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(3):620–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alippe Y, Wang C, Ricci B, et al. Bone matrix components activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote osteoclast differentiation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burton L, Paget D, Binder NB, et al. Orthopedic wear debris mediated inflammatory osteolysis is mediated in part by NALP3 inflammasome activation. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2013;31(1):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caicedo MS, Desai R, McAllister K, Reddy A, Jacobs JJ, Hallab NJ. Soluble and particulate Co-Cr-Mo alloy implant metals activate the inflammasome danger signaling pathway in human macrophages: a novel mechanism for implant debris reactivity. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2009;27(7):847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caicedo MS, Samelko L, McAllister K, Jacobs JJ, Hallab NJ. Increasing both CoCrMo-alloy particle size and surface irregularity induces increased macrophage inflammasome activation in vitro potentially through lysosomal destabilization mechanisms. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2013;31(10):1633–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maitra R, Clement CC, Scharf B, et al. Endosomal damage and TLR2 mediated inflammasome activation by alkane particles in the generation of aseptic osteolysis. Mol Immunol. 2009;47(2–3):175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St Pierre CA, Chan M, Iwakura Y, Ayers DC, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW. Periprosthetic osteolysis: characterizing the innate immune response to titanium wear-particles. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2010;28(11):1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manzano GW, Fort BP, Dubyak GR, Greenfield EM. Wear particle-induced priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome depends on adherent pathogen-associated molecular patterns and their cognate toll-like receptors: an in vitro study. Clin Orthop. 2018;476(12):2442–2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoss F, Rodriguez-Alcazar JF, Latz E. Assembly and regulation of ASC specks. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(7):1211–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brojatsch J, Lima H, Palliser D, et al. Distinct cathepsins control necrotic cell death mediated by pyroptosis inducers and lysosome-destabilizing agents. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(7):964–972. 10.4161/15384101.2014.991194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lima H Jr Jr., Jacobson LS, Goldberg MF, et al. Role of lysosome rupture in controlling Nlrp3 signaling and necrotic cell death. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(12):1868–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts mediate NALP-3 inflammasome activation via phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(8):847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orlowski GM, Colbert JD, Sharma S, Bogyo M, Robertson SA, Rock KL. Multiple cathepsins promote pro-IL-1β synthesis and NLRP3-mediated IL-1β activation. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 2015; 195(4):1685–1697. 1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlowski GM, Sharma S, Colbert JD, et al. Frontline science: multiple cathepsins promote inflammasome-independent, particle-induced cell death during NLRP3-dependent IL-1β activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Núñez G. K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38(6):1142–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rashidi M, Simpson DS, Hempel A, et al. The pyroptotic cell death effector Gasdermin D is activated by Gout-associated uric acid crystals but is dispensable for cell death and IL-1β release. J Immunol. 2019;203(3):736–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huk OL, Zukor DJ, Ralston W, Lisbona A, Petit A. Apoptosis in interface membranes of aseptically loose total hip arthroplasty. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2001;12(7):653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renò F, Sabbatini M, Massè A, Bosetti M, Cannas M. Fibroblast apoptosis and caspase-8 activation in aseptic loosening. Biomaterials. 2003;24(22):3941–3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landgraeber S, von Knoch M, Löer F, et al. Extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of apoptosis in aseptic loosening after total hip replacement. Biomaterials. 2008;29(24):3444–3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang XS, Revell PA. In situ localization of apoptotic changes in the interface membrane of aseptically loosened orthopaedic implants. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 1999;10(12):879–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang F, Wu W, Cao L, et al. Pathways of macrophage apoptosis within the interface membrane in aseptic loosening of prostheses. Biomaterials. 2011;32(35):9159–9167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwab LP, Marlar J, Hasty KA, Smith RA. Macrophage response to high number of titanium particles is cytotoxic and COX-2 mediated and it is not affected by the particle’s endotoxin content or the cleaning treatment. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;99(4):630–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petit A, Catelas I, Antoniou J, Zukor DJ, Huk OL. Differential apoptotic response of J774 macrophages to alumina and ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene particles. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2002;20(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuchiya K Inflammasome-associated cell death: pyroptosis, apoptosis, and physiological implications. Microbiol Immunol. 2020;64: 252–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beidelschies MA, Huang H, McMullen MR, et al. Stimulation of macrophage TNFalpha production by orthopaedic wear particles requires activation of the ERK1/2/Egr-1 and NF-kappaB pathways but is independent of p38 and JNK. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217(3):652–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasko MK, Goodman SB. Emperor’s new clothes: is particle disease really infected particle disease? J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2016;34(9):1497–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samelko L, Landgraeber S, McAllister K, Jacobs J, Hallab NJ. Cobalt alloy implant debris induces inflammation and bone loss primarily through danger signaling, not TLR4 activation: implications for DAMP-ening implant related inflammation. PLOS One. 2016;11(7): e0160141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hari A, Zhang Y, Tu Z, et al. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by crystalline structures via cell surface contact. Sci Rep. 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4250918/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(21):7972–7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turk B, Bieth JG, Björk I, et al. Regulation of the activity of lysosomal cysteine proteinases by pH-induced inactivation and/or endogenous protein inhibitors, cystatins. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1995;376(4): 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coll RC, Robertson AAB, Chae JJ, et al. A small molecule inhibitior of the NLRP3 inflammasome is a potential therapeutic for inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21(3):248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russo HM, Rathkey J, Boyd-Tressler A, Katsnelson MA, Abbott DW, Dubyak GR. Active caspase-1 induces plasma membrane pores that precede pyroptotic lysis and are blocked by lanthanides. J Immunol Baltim Md. 2016;197(4):1353–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, Sun B, Liu S, Xia T. Structure Activity relationships of engineered nanomaterials in inducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation and chronic lung fibrosis. Nano Impact. 2017;6:99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kusaka T, Nakayama M, Nakamura K, Ishimiya M, Furusawa E, Ogasawara K. Effect of silica particle size on macrophage inflammatory responses. PLOS One. 2014;9(3):e92634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P, Kroemer G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 2019;29(5):347–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Xia S, et al. Gasdermin E suppresses tumour growth by activating anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2020;579(7799):415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu X, Lieberman J. Knocking’em dead: pore-forming proteins in immune defense. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020;38:455–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bechtel CP, Gebhart JJ, Tatro JM, Kiss-Toth E, Wilkinson JM, Greenfield EM. Particle-induced osteolysis is mediated by TIRAP/Mal in vitro and in vivo: dependence on adherent pathogen-associated molecular patterns. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(4):285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greenfield EM, Beidelschies MA, Tatro JM, Goldberg VM, Hise AG. Bacterial pathogen-associated molecular patterns stimulate biological activity of orthopaedic wear particles by activating cognate toll-like receptors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(42):32378–32384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.