Abstract

Indigenous women globally are subjected to high rates of multiple forms of violence, including intimate partner violence (IPV), yet there is often a mismatch between available services and Indigenous women’s needs and there are few evidence-based interventions specifically designed for this group. Building on an IPV-specific intervention (Intervention for Health Enhancement After Leaving [iHEAL]), “Reclaiming Our Spirits” (ROS) is a health promotion intervention developed to address this gap. Offered over 6 to 8 months in a partnership between nurses and Indigenous Elders, nurses worked individually with women focusing on six areas for health promotion and integrated health-related workshops within weekly Circles led by an Indigenous Elder. The efficacy of ROS in improving women’s quality of life and health was examined in a community sample of 152 Indigenous women living in highly marginalizing conditions in two Canadian cities. Participants completed standard self-report measures of primary (quality of life, trauma symptoms) and secondary outcomes (depressive symptoms, social support, mastery, personal agency, interpersonal agency, chronic pain disability) at three points: preintervention (T1), postintervention (T2), and 6 months later (T3). In an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) were used to examine hypothesized changes in outcomes over time. As hypothesized, women’s quality of life and trauma symptoms improved significantly pre- to postintervention and these changes were maintained 6 months later. Similar patterns of improvement were noted for five of six secondary outcomes, although improvements in interpersonal agency were not maintained at T3. Chronic pain disability did not change over time. Within a context of extreme poverty, structural violence, and high levels of trauma and substance use, some women enrolled but were unable to participate. Despite the challenging circumstances in the women’s lives, these findings suggest that this intervention has promise and can be effectively tailored to the specific needs of Indigenous women.

Keywords: domestic violence, mental health and violence, cultural contexts, intervention/treatment

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has been increasingly recognized as a pressing public health issue for women globally. In its first report on global prevalence of violence against women—including both IPV and nonpartner sexual violence—the World Health Organization (WHO, 2013) highlighted the pervasiveness of IPV worldwide, with 30% of ever-partnered women having experienced physical or sexual violence from their intimate partners. IPV is known to have long-term and often severe consequences on the health of women. Studies, including systematic reviews, repeatedly show that the most significant outcomes associated with IPV are depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety (Chmielowska & Fuhr, 2017; Devries et al., 2013; Lagdon, Armour, & Stringer, 2014). Indeed, in a systematic review, Devries et al. showed that for women, IPV was associated with incident-depressive symptoms, and depressive symptoms with incident IPV suggesting that IPV can lead to depression, and that depression may create vulnerability to IPV.

In Canada, violence against women continues to be a major problem as indicated by police-reported and self-reported spousal violence data showing that women are more likely to be victims of severe forms of IPV in comparison with men. Women are twice as likely to report severe forms of spousal violence (i.e., being sexually assaulted, beaten, choked, or threatened with a gun or a knife) as compared with men (Statistics Canada, 2016b). Furthermore, some groups, including Indigenous women, women with disabilities, and those who identify as lesbian or bisexual, are more likely to experience more frequent and severe forms of IPV (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2016). Specifically, as is the case globally (Chmielowska & Fuhr, 2017), Indigenous women in Canada are at least 3 times more likely to have experienced IPV in the previous 5 years as compared with other Canadian women (Statistics Canada, 2016b) and face 7 times greater risk of being choked, threatened with a weapon, and severely beaten (Puchala, Paul, Kennedy, & Mehl-Madrona, 2010) than non-Indigenous women. Moreover, while IPV rates have declined in the general population in Canada, a similar trend has not been seen among Indigenous women, where rates have remained constant in the past decade (Statistics Canada, 2016b).

Colonization has been proposed as the leading explanation for the high rates of interpersonal violence experienced in Indigenous communities (Brassard, Montminy, Bergeron, & Sosa-Sanchez, 2015; Brownridge et al., 2017; Burnette, 2016; Finfgeld-Connett, 2015; Kuokkanen, 2015; Kwan, 2015). These studies illustrate that colonization has eroded Indigenous ways of living and destabilized large proportions of the population through racism, oppression, and loss of resources, autonomy, and culture. Research also shows that colonialism has affected and continues to shape Indigenous peoples’ life experiences and the myriad ways violence has become rooted in the historical, political, and socioeconomic contexts of their lives. In addition, experiences of IPV and mental disorders among Indigenous women appear linked and exacerbated by poverty, discrimination, and substance abuse (Chmielowska & Fuhr, 2017).

In Canada, the countless forms of structural violence, discrimination, and violations of human rights targeting Indigenous people are particularly evident in the Canadian government’s assimilation policies, strategies of the Indian Act of 1876, 2 and the creation of residential schools, all of which contributed to the intergenerational transmission of violence that increases the risk of IPV (Brownridge et al., 2017; Daoud, Smylie, Urquia, Allan, & O’Campo, 2013; Kwan, 2015). Being subjected to forced assimilation, violence, and abuse at residential schools and more recently in other forms of state care (e.g., foster care) has meant that entire generations of Indigenous children have grown up without learning healthy parenting. Among the consequences of these forms of trauma are challenges with interpersonal relationships including the ability to regulate emotions, behaviors, and expectations of others in intimate relationships, making people vulnerable both as victims and perpetrators of IPV (Brownridge et al., 2017; Burnette, 2016; Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Evans-Campbell, 2008).

Although violence against women was traditionally considered taboo (K. Anderson, 2001; Matamonasa-Bennett, 2014), over time, the imposition of Westernized beliefs including the propagation of patriarchy meant that customary expressions of respect in Indigenous communities were often disrupted, and the balance of power between men and women in the community displaced (Burnette, 2016; Daoud et al., 2013; Finfgeld-Connett, 2015). Colonization, past and present, continues to manifest in many ways including the structural challenges of poverty and lack of access to resources such as land, education, health, and housing that confront Indigenous women disproportionately, increasing their social vulnerability and exposure to abuse (Anaya, 2012; Daoud et al., 2013; Kolahdooz, Nader, Yi, & Sharma, 2015; Pedersen, Malcoe, & Pulkingham, 2013). Although understanding the role of history in shaping violence against Indigenous people is important, current manifestations of gender-based violence and how those are interpreted and addressed within Indigenous communities need to be better understood (Kuokkanen, 2015). To address the issue of IPV and the needs of Indigenous women, a holistic approach guided and rooted in the collective cultural knowledge of Indigenous people has been advised (Finfgeld-Connett, 2015).

Over the last few decades, in North America and globally, IPV interventions aimed at women with histories of IPV have been trialed using a variety of approaches (e.g., counseling, advocacy) and periods of intervention (brief or extended). A recent systematic review showed that most short-term interventions (time-limited groups and individual treatment modalities less than eight sessions) are effective with large effect sizes in targeted areas such as PTSD, self-esteem, depression, general distress, and life functioning—with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)–based interventions tailored to individual women having the largest effect sizes (Arroyo, Lundahl, Butters, Vanderloo, & Wood, 2017). Interventions offered over extended periods of time, particularly those that use counseling and structured therapy, have shown promise in reducing the negative effects of IPV including PTSD symptoms and depression and in improving the quality of life (QOL) and social support of women (Eckhardt et al., 2013; Johnson, Zlotnick, & Perez, 2011; Sullivan, Bybee, & Allen, 2002). Components found to be effective include safety planning for violence, skill building in self-care for mental health, and strategies for reducing stress (Sabri & Gielen, 2017). There is empirical support showing that effective IPV interventions should be tailored to meet the needs of specific women and their stage of readiness (C. Anderson, 2003; Haggerty & Goodman, 2003) and place responsibility not solely on service providers but on the system as a whole where one point of contact connects to other access points for IPV information and services (Chang et al., 2005).

Conventional interventions based on case management approaches for people who have experienced violence in the family, including IPV, often reflect Western-based individualistic thinking, and are usually not inclusive of Indigenous knowledges or worldviews (Jackson, Coleman, & Sweet Grass, 2015; Kwan, 2015). Attempts to adapt these approaches, for example, through the addition of a cultural competency framework, tend to act as major barriers for Indigenous women in accessing services, further marginalizing women by reproducing “colonial violence” (Jackson et al., 2015; Kwan, 2015). However, group-based interventions that connect Indigenous women with family and community and integrate traditional knowledges have been shown to be preferred forms of IPV intervention because they are grounded in values of sharing, for example, sharing food, stories, and healing pathways (Jackson et al., 2015; Kwan, 2015; Norton & Manson, 1997; Puchala et al., 2010). Scholars argue that for an intervention to be accepted and effective in Indigenous communities, it needs to be safe, respectful, flexible, multilevel, and based on Indigenous worldviews of spirituality, ceremonies, and interconnectedness (Lester-Smith, 2013; Riel, Languedoc, Brown, & Gerrits, 2016). In the Australian context, Spangaro et al. (2016) reported four elements identified by Australian Indigenous women as key for them to engage with IPV services, namely, “Build the relationship first, Come at it slowly, People like me are here, and A process of borrowed trust” (p. 86). In Canada, community-based group interventions designed by Indigenous women themselves have shown promise in terms of therapeutic and healing effects for women with histories of abuse; these interventions have included storytelling and other health promoting cultural activities that foreground Indigenous ceremonies and traditions, along with guidance and teachings of Elders (Jackson et al., 2015; Lester-Smith, 2013; Puchala et al., 2010).

In summary, research shows high levels of IPV against Indigenous women, with significant impacts compounded by poverty, individual and systemic forms of discrimination, and structural violence. Research further suggests that the needs of Indigenous women are not well met by conventional services and interventions. However, few interventions have been developed or tested specifically for Indigenous women. One exception is the online safety decision aid, (nicknamed ‘iSAFE’), which was tailored to Māori women in New Zealand, and tested in a randomized control trial (Koziol-McLain et al., 2018). The intervention was shown to be effective in reducing IPV exposure for Māori but not for non-Māori women, supporting the contention that tailored approaches are needed for specific groups. In Canada, there have been no interventions tailored for and tested with Indigenous women with histories of IPV. Therefore, building on our ongoing program of research on the efficacy of a health promotion intervention for women who have experienced IPV, known as the Intervention for Health Enhancement After Leaving (iHEAL), we developed an intervention designed to support Indigenous women who have experienced violence (Varcoe et al., 2017). The purpose of this study was to test the efficacy of this intervention, known as Reclaiming Our Spirits (ROS), in improving the QOL and health of a community sample of Indigenous women living in two Canadian cities.

From iHEAL to ROS

iHEAL was developed based on a grounded theory derived from a study conducted with women who had left abusive partners (Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, Varcoe, & Wuest, 2011; Ford-Gilboe, Wuest, Varcoe, & Merritt-Gray, 2006; Wuest, Ford-Gilboe, Merritt-Gray, & Varcoe, 2013) and evidence regarding the health effects of violence against women and effective health promotion interventions. In the grounded theory, the central problem women face in attempting to move beyond a life of abuse is intrusion—unwanted interference from ongoing harassment or abuse, cumulative physical and mental health consequences of abuse, undesirable life changes such as reduced economic circumstances and social isolation, and the “costs” (i.e., stress and conflict related to bureaucratic process and personal expectations) of getting help from family members, friends, and “the system.” The grounded theory identified six ways that women worked to limit the intrusion they experienced and strengthen their own capacities. The ways women strengthen their capacity to limit intrusion (managing basics, managing symptoms, regenerating family, renewing self, safeguarding, and cautious connecting) provide the substantive focus for the components of the intervention.

The intervention initially was conceptualized as nurse-led, working in partnership with women and community organizations, and guided by 10 principles, using a three-phase process (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2011). This version of iHEAL was tested in two feasibility studies conducted in the provinces of Ontario and New Brunswick (Wuest et al., 2015), using slightly different partnership models (i.e., a social worker was part of the nursing team in Ontario, whereas nurses partnered with domestic violence outreach workers in New Brunswick). In both studies, community health nurses (CHNs) worked in partnership with women in ~10 to 18 sessions over approximately 6 months. Both studies used single group before-after designs, with assessments conducted at baseline, immediately postintervention, and 6 months later. Interviews were also conducted with women and nurses to understand how iHEAL was implemented and experienced, including its acceptability, benefits, and barriers to implementation. Results of both studies supported that iHEAL was feasible to implement, at reasonable cost (~Can$2600 per woman) and acceptable to women, who showed significant improvements over time in key areas, including mental health, QOL, self-efficacy, and mastery. These feasibility studies suggested that iHEAL is a promising intervention for women with histories of IPV and that it would be strengthened by more attention to spirituality and substance use issues and opportunities for women to connect with one another. Although some Indigenous women participated in both previous studies, iHEAL was not specifically designed with the needs and contexts of Indigenous women in mind. Consequently, without modification, iHEAL could be experienced as overlooking and ignoring Indigenous women’s particular needs and contexts (Varcoe et al., 2017).

We worked to mitigate the risk of creating a colonizing intervention through a series of interrelated approaches including (a) guidance from a steering committee of Indigenous women with research expertise specific to IPV and Indigenous women’s experiences; (b) articulation of an Indigenous lens, including using Cree (one of the largest Indigenous language groups in North America) concepts to identify key aspects; and (c) interviews with Indigenous Elders (n = 10) residing in the study setting. Through this work, we developed 10 new principles to guide the intervention and integrated a Circle, 3 led by an Elder (Varcoe et al., 2017). The Circles were conducted as group activities focused on Indigenous cultural teachings, in which women could participate or decline to do so. Results of pilot testing the intervention with 21 Indigenous women showed improvements in QOL, depressive symptoms and trauma symptoms, personal and interpersonal agency, and social conflict from pre- to postintervention, but worsening pain and pain disability (Varcoe et al., 2017). Women found the pilot intervention acceptable and helpful but suggested more attention to substance use issues, more traditional teachings, trauma counseling, information on IPV, and safety planning. They wanted to have the Circle led by more than one Elder, especially to integrate more diverse cultural teachings, and to have more structured and smaller Circles to limit the number of traumatic stories being told. Although the women in the pilot study all had experienced IPV, the difficulty of determining what constituted having “left” an abusive partner led us to widen our inclusion criteria and, ultimately, to change the meaning of the acronym iHEAL to mean “intervention for health enhancement and living.” At the end of the pilot study, the women renamed what they called the “program” to “ROS.” The study protocol was revised based on the pilot study findings and a refined version of ROS was created. Specifically, we hired two Elders (one from the Indigenous territory in which the study was conducted, the other from one of the most prevalent Indigenous groups in Canada), framed the Circles as informational (rather than open sharing circles), integrated health information in a workshop format, and intensified the nurses’ training on pain management and substance use. This study was undertaken to test the efficacy of ROS with a larger sample of Indigenous women and to further evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and costs of delivering this intervention.

Method

Congruent with recommendations for evaluation of complex interventions (Egan, Bambra, Petticrew, & Whitehead, 2009; Hawe, 2015; Lewin, Glenton, & Oxman, 2009; Sandelowski, 1996), we conducted a longitudinal, mixed methods study to examine the process and outcomes associated with ROS in a sample of 152 Indigenous women who had experienced IPV in their lifetimes. The study was conducted in a Western Canadian province in two cities: one site in suburban city (a housing complex for women experiencing violence) and two sites (a community center, and a housing complex for women experiencing violence) in the inner city of a large urban center. The intervention was delivered over 6 to 8 months by nurses and Elders hired for the study, supported by the research team and other experts. All women who enrolled in the study were offered the intervention. Participants completed standard self-report measures of primary (QOL, trauma symptoms) and secondary outcomes (depressive symptoms, social support, mastery, personal agency, interpersonal agency, chronic pain disability) at three points in time: preintervention (T1), postintervention (T2), and 6 months later (T3). Specifically, for each outcome, we hypothesized the following: (a) there would be significant improvements from preinvention (T1) to immediately postintervention (T2) and (b) these improvements would be maintained 6 months after the intervention ended (T3). At postintervention (T2) and follow-up (T3), qualitative interviews were conducted to explore women’s experiences of the intervention and the process by which the intervention produced the desired effects, and to identify unanticipated outcomes and barriers to implementation. Economic costs were estimated using administrative records.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was provided by the first author’s university ethics review board. Key ethical considerations included minimizing harm related to participation, including exposure to traumatizing stories during group activities, repeated recounting of their own experiences, and exposure to social judgment by any study staff. This study was conducted in settings in which there are high rates of poverty, very limited affordable housing options, and a concentration of services for people with substance use issues, HIV, and mental health problems. We provided the nurses with 60 hrs of training related to the intervention model, violence, trauma- and violence-informed care, chronic pain, substance use, and mental health. We also provided training related to Indigenous cultural safety, using a well-recognized online training developed for this purpose. The Elders were already skilled leaders of Indigenous ceremonies and Circles, but joined the nurses for training on trauma. Based on the Elders’ prior experience and the pilot study, they established guidelines with the women for Circle participation to promote safety. We used strategies to avoid coercion to participate, such as offering honoraria and food without expectation of participation. The interviewers were trained to assess for distress and offer appropriate resources to women in a mandatory follow-up phone call after each interview. When we recognized that the initial survey was distressing for many women and we were unable to reach women for follow-up (e.g., women had no phones or no airtime available on their phones), we deleted some questions and moved others (e.g., child maltreatment questions) to a later time point, and set follow-up for debriefing in person.

Recruitment

A community sample of 152 women was recruited over 10 months primarily through community-based recruitment strategies that included collaborating with health and social service providing agencies in the study areas, posting advertisements on community boards, making presentations about the study, and word of mouth. Eligibility criteria included (a) self-identifying as Indigenous; (b) having experienced IPV in their lifetime, as determined by both self-report and a modified, four-item version of the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) (Parker & McFarlane, 1991); (c) being above 18 years of age; and (d) living in an area adjacent to a study site. Originally designed as a cross-over cohort study, no women who expressed interest in the study were willing to delay participation in the intervention. Women were still enrolled in two cohorts to better manage the group size and workload of the nurses and Elders. Because there were no significant differences between the cohorts on any demographic or outcome variables, the cohorts were combined for analysis.

Data Collection and Measurement

Data were collected from participants during face to face interviews conducted by trained research assistants at enrolment (T1, preintervention), immediately postintervention (T2), and 6 months later (T3) at a safe location of the woman’s choosing (usually a community health or education center). Women were provided with honoraria of $25 and costs of transportation and child care (as needed) in relation to each interview. At all three time points, interviews included standardized self-report measures of study outcomes. Information about women’s demographic characteristics and abuse histories were collected using survey questions at T1 (after the first 65 women, child maltreatment data were collected at T2). The preintervention interviews took 45 min to 2.5 hr (average 1.5) to complete, while postintervention interviews averaged 2 hr and included, or were followed by, a qualitative interview focused on the women’s experiences of the intervention. Administrative data used to estimate the costs of the intervention were recorded by nurses and Elders on a standard form created for the study as part of their documentation of women’s engagement in the intervention.

Study outcomes

Seven self-report instruments, each with established reliability and validity, were used to measure the study outcomes.

Quality of Life was measured using the Sullivan’s Quality of Life Scale (Sullivan & Bybee, 1999), a brief nine-item measure adapted from a longer measure developed by Andrews and Withey (1976) for women with histories of IPV and validated with them (Bybee & Sullivan, 2002, 2005). Participants are asked to rate each item on a 7-point scale measuring satisfaction with particular areas of their lives from extremely pleased (1) to terrible (7). Responses are reverse-scored and summed with higher scores indicating higher QOL. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .890.

Trauma Symptoms were measured using the PTSD checklist, Civilian Version (PCL-C), a 17-item self-report measure used in community settings to assess meeting of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Weathers, Huska, & Keane, 1991; Wilkins, Lang, & Norman, 2011). Participants are asked to report how much each symptom has bothered them in the past month using a 5-point Likert-type scale, from not at all (1) to extremely (5). Items are summed with a possible range of 17 to 85, with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology. A cutoff of 44 is recommended as indicator of probable clinically significant trauma symptoms. Validity and internal consistency reliability (.94 for the total scale and .82-.94 for subscales) are well demonstrated (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996). Internal consistency of the total PCL-C scores in the sample was .936.

Depressive Symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Revised (CESD-R), a 20-item self-report measure of symptoms reflective of the DSM-IV criteria for depression (Eaton, Smith, Ybarra, Carles, & Tien, 2004). Women are asked to report how often they have experienced each symptom in the past week or so, using five options, from not at all or less than 1 day (0) to nearly every day for 2 weeks (4). The highest scores are summed with a possible range of 0 to 60. A cutoff score of 16 is consistent with symptoms of clinical depression. The CESD-R demonstrates good to excellent face and construct validity, as well as excellent internal consistency (α = .90-.96; Van Dam & Earleywine, 2011). Internal consistency in this study was .940.

Chronic pain disability was measured using the pain disability score from Von Korff, Ormel, Keefe, and Dworkin’s (1992) scale, in which three items measure pain-related interference with daily activities; change in ability to take part in recreational, social, and family activities; and change in ability to work. Each item measures interference from 0 to 10; higher scores indicate higher interference. Scores were averaged and multiplied by 10, transformed to a 0 to 100 range. Cronbach’s alpha in this study .929.

Social support was measured using the 13-item support scale of the Interpersonal Resources Inventory (IPRI) (Tilden, Hirsch, & Nelson, 1994), a self-report measure designed to assess perceived availability of emotional, informational, and instrumental support. Participants are asked to rate their access to social support on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), or how often they have social support from never (1) to very often (5). Responses are summed to produce scores (range = 0-65); higher scores reflect higher levels of social support. Internal consistency was .884 in the study sample.

Personal and Interpersonal Agency were assessed using the Personal Agency Scale (PAS) and Interpersonal Agency Scale (IAS) (Smith et al., 2000). In the PAS (eight items), participants report how often they use their own efforts, abilities, and skills to accomplish their goals on a scale ranging from never (1) to often (4). Responses are summed for a total score of 8 to 32. In the IAS (five items), participants report how often they work with other people to achieve their goals from never (1) to often (4). Responses are summed for a total score of 5 to 20. The PAS and IAS have demonstrated high construct validity as well as acceptable Cronbach’s alpha and split-half reliability (Smith et al., 2000). Internal consistency was .863 for PAS and .886 for IAS in the study sample.

Mastery or perceptions of personal control over one’s life was measured on Pearlin’s self-report, seven-item Mastery Scale (Pearlin & Radabaugh, 1976; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). Women are asked to rate how much they agree/disagree that they feel in control over their life circumstances from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). Scores are produced by summing all responses so that higher scores indicate higher perceived mastery. This scale has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .75-.78) and is used widely in various population groups with good results (Turner, Pearlin, & Mullan, 1998). In this study, the mean inter-item correlation for these items was .216.

Demographic characteristics and abuse histories

Information about women’ s demographic characteristics was collected using survey questions, and standard self-report measures were used to collect the women’s abuse histories. To gather information about socioeconomic conditions, women were asked about their employment status, income, and work experiences. The Financial Strain Index (FSI) (Ali & Avison, 1997) was used to rate women’s difficulty meeting financial obligations on a 4-point scale ranging from very difficult (1) to not at all difficult (4). They were also asked about their dependent children and child support, housing situation and shelter use in the last year, and self-identification with Indigenous communities (i.e., First Nations, Inuit, and Métis). Experiences of IPV were measured using the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS; Hegarty, Sheehan, & Schonfeld, 1999), a 30-item scale that asks how often they had experienced various abusive experiences on a 6-point Likert-type scale from 0 (never) to 5 (daily). For this study, three sexual abuse items were revised: “Put foreign objects in my vagina” was revised to “Made me perform sex acts that I did not enjoy or like,” “Raped me” was revised to “Forced me to have sex,” and “Tried to rape me” was revised to “Tried to force me to have sex.” Child abuse experiences were assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein & Fink, 1998), with women asked whether they believed they had experienced different acts of childhood maltreatment and neglect on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from never true (1) to very true (5). Finally, experiences of sexual assault were assessed using two questions from the Canadian Violence Against Women Survey (Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, 1993) which assesses experiences of sexual assault since the age of 16 as defined by the Canadian Criminal Code. Specifically, women were asked to report (yes/no) if they had been (a) touched against their will in a sexual way and (b) forced into sexual activity.

Costs of the Intervention

Adminstrative data recorded by nurses and Elders were used to estimate the costs involved in providing the intervention. These included (a) staff time (nurses and Elders) spent working with women, in clinical meetings, completing documentation, making referrals, and related work; (b) transportation costs (nurses, Elders, and women) involved in meetings between interventionists and the women; (c) child care costs for women who needed child care while participating; (d) materials for Circles including art supplies and refreshments, honoraria for guest speakers, and room rental; and (e) participation-related costs incurred during women’s meetings with a nurse including refreshments. In a few instances, the nurses provided women a small amount of money to cover the costs associated with getting an identity card, birth certificate, or notary services required to complete applications for housing or other services.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics appropriate to the data were used to summarize all study variables. Chi-square and t tests were used to test for baseline differences between those with and without missing data. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) were used to assess changes in outcome measures over time. As GEE does not require complete data at each time point, all women were included in the analysis. Time was specified as a categorical variable with preintervention as the reference group. The models were tested for differences in outcomes between pre- and postintervention and between preintervention and 6-month follow-up. All women were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis reported here. ITT analysis retains every participant, regardless of level of participation, including those not participating in the intervention. This strategy is similar to actual clinical practice and leads to more conservative, that is, smaller, estimates of intervention effects.

Qualitative data from individual interviews were analyzed using an interpretive thematic analysis following the procedures and guidelines for rigor involved in qualitatively derived data (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Denzin & Lincoln, 2017; Thorne, 2016). Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, and checked by the interviewer to ensure accuracy. The transcripts were read repeatedly by the research team to identify recurring and contradictory patterns and themes. Based on these readings, a preliminary set of codes were developed and the team jointly coded the initial 12 interview transcripts that led to further refinement of coding categories. We used NVivo™ to assist with organizing and coding of the interviews. The research team, which included Indigenous steering committee members, met regularly during the coding process to assess interrater reliability, resolve discrepancies, and ensure consistency.

Costs of the intervention were estimated by summing expenses across all categories, exclusive of training for the nurses, and dividing this figure over all women, regardless of level of participation, to yield an average per woman cost.

Sample

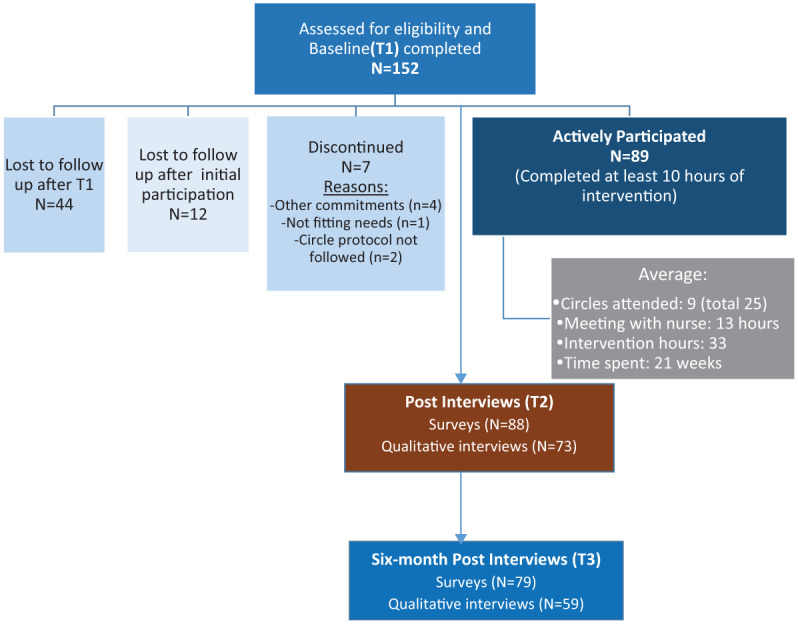

In all, 152 women consented to participate, completed baseline data collection, and were enrolled in the study; all met the eligibility criteria. As shown in Figure 1, of the 152 women, 44 women (29%) completed the baseline assessment (T1), but did not participate in the intervention; 108 (71%) participated. Of the 108 who initiated participation, 12 (8%) were “lost to follow-up” after attending one or two circles or meetings with a nurse, while seven (5%) actively discontinued participating, citing other commitments, a lack of fit, or that Indigenous protocol was not being followed in the Circles. Active participation was, therefore, defined as completing a minimum of 10 hrs with the nurses and/or Elders. Compared to those who actively participated, the 19 women who initiated participation but discontinued reported experiencing more severe IPV (mean CAS scores 81.6 vs. 34.3), had lower median incomes ($736 vs. $929/month), and were more likely to report problem drinking based on the Audit (62.5% vs. 46.5%).

Figure 1.

ROS CONSORT flow diagram.

Note. ROS = Reclaiming Our Spirits.

The 89 women who actively participated attended an average of nine circles and met an average of 13 hrs with a nurse, for a total average of 33 intervention hours over an average of 21 weeks. The retention rate postintervention (T2) was 58%, and 52% at the 6-month follow-up (T3).

The demographic characteristics of women are shown in Table 1. All identified as Indigenous and were from diverse nations and language groups from across Canada. The women faced significant economic hardship. Their average annual income (Can$9,570) was well below the Canadian poverty line, which for a single person living in a large city in Canada in the year of data collection (2015) was Can$22,133, based on low-income measure after tax (LIM-AT) (Statistics Canada, 2016a). Their average monthly housing costs were nearly one half of their average monthly income, and 39% had spent one or more nights in a housing shelter in the previous 12 months. The women also experienced high levels of multiple forms of violence: over 75% had experienced physical, sexual, and psychological child maltreatment, whereas 84% and 91% reported experiences of childhood physical and emotional neglect, respectively, indicators of social disadvantage and a reflection of the extensive state interference with Indigenous parenting; 71% had been sexually assaulted since age 16. The average score on the CAS was 48, with 90.1% having a score above 3 and 85.7% having a score above 7. Taft, Small, Hegarty, Lumley, Watson, and Gold (2009) use a cutoff of 3 for low levels of abuse and a cutoff of 7 for high levels of abuse.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 152).

| Sample Characteristics | n | % | M or Mdn a | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 47 a | 18-66 | |||

| Indigenous identity | |||||

| First Nations | 128 | 86.5 | |||

| Métis | 19 | 12.8 | |||

| Inuit | 1 | 0.7 | |||

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed full or part-time | 18 | 12.0 | |||

| Unemployed | 132 | 88.0 | |||

| Income | |||||

| Receiving disability assistance b | 100 | 66.7 | |||

| Receiving social assistance | 35 | 25.2 | |||

| Personal monthly income | 797.50 a | 0-5,156 | |||

| Living situation | |||||

| Living with partner | 19 | 13.5 | |||

| Mother of child(ren) under 18 years | 63 | 42.9 | |||

| Living with children full- or part-time | 39 | 63.9 c | |||

| One or more nights at a shelter in the past 12 months | 58 | 38.9 | |||

| Change in residence in the past 12 months | 62 | 44.6 | |||

| Abuse history | |||||

| Severity of IPV (past 12 months) d | 48.216 | 40.265 | |||

| Experienced sexual assault (since age 16) | 72 | 71.3 | |||

| Childhood abuse e | |||||

| Emotional abuse | 89 | 88.1 | |||

| Physical abuse | 77 | 75.5 | |||

| Sexual abuse | 81 | 81.8 | |||

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; CAS = Composite Abuse Scale; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

Percentages shown are true estimates for the sample, not adjusting for missing data.

Disability assistance is approximately Can$200/month more than social assistance and provides access to some additional health care benefits.

Percentage of women with children.

Based on CAS.

Based on CTQ clinical subscales; percentage of women who scored as having low, moderate, or severe maltreatment for each of these subscales.

Results

Baseline descriptive statistics for each outcome are provided in Table 2. The women had very high levels of depressive symptoms, trauma symptoms, and chronic pain: 72.4% of the women were above the cutoff score for significant or high depressive symptoms, 59.6% were above the cutoff score for clinical trauma symptoms, and 49.7% had moderately or severely limiting pain. The average chronic pain disability score of 49.21 was considerably higher than found in a sample of 309 Canadian women who had experienced IPV where the mean was 37.28 (Wuest et al., 2009). The women’s reported QOL (M = 38.62; SD =11.49) was similar to our earlier feasibility study in which the women’s QOL was 39.2 (SD = 9.9) using the same scale (Wuest et al., 2015). To interpret levels of social support, personal agency, interpersonal agency, and mastery, we converted mean scores back to the 4- or 5-point scale used for reporting each item. Mean levels of both social support and mastery were moderate (3.44 and 3.37 on 5-point scale, respectively); similarly, mean scores for both personal agency and interpersonal agency were slightly above the mid-point of the response scale (3.04 and 2.99, respectively) and consistent with scores in the moderate range.

Table 2.

Baseline Descriptive Statistics for Study Outcomes (N = 152).

| M | SD | Range | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | 38.62 | 11.49 | 16-62 | |

| Trauma symptoms | 49.13 | 16.20 | 17-81 | |

| Score of 44 or above (indicating probable clinical trauma symptoms) | 90 (59.6) | |||

| Depressive symptoms | 28.25 | 15.67 | 0-56 | |

| Score of 16 or above (indicating probable depression) | 110 (72.4) | |||

| Pain disability | 49.21 | 30.32 | 0-100 | |

| Pain Grade III: High disability (moderately limiting) | 33 (23.1) | |||

| Pain Grade IV: High disability (severely limiting) | 38 (26.6) | |||

| Pain intensity | 57.84 | 25.21 | 0-100 | |

| Social support a | 44.78 | 8.99 | 20-60 | |

| Interpersonal agency | 14.65 | 4.13 | 5-20 | |

| Personal agency | 24.30 | 5.37 | 10-32 | |

| Mastery | 23.58 | 5.37 | 9-35 |

One item from the Interpersonal Relationships Inventory: Social Support measure was missing from 73 of the questionnaires, so the social support score excludes this item.

Those who completed all three time points (n = 70) did not differ from those who missed one or more time points (n = 82) on Indigenous identity (p = .604), personal income (p = .356), employment status (p = .351), whether they lived with their partners (p = .239), were parenting dependent children (p = .886), lived with their children (p = .360), whether they had stayed in a shelter in the past 12 months (p = .274), or had a permanent change in residence in the past 12 months (p = .972). They also did not differ on pain disability (p = .194), depressive symptoms (p = .369), trauma symptoms (p = .338), mastery (p = .711), personal agency (p = .580), interpersonal agency (p = .604), or severity of abuse (p = .200). Those who completed all three assessments were significantly younger (M = 42.14 vs. M = 47.89, p = .009) and had lower QOL (M = 36.14 vs. M = 41.46, p = .005).

Tests of the Hypotheses

As hypothesized, the women experienced significant improvements in QOL, trauma symptoms (primary outcomes), and depressive symptoms, social support, and mastery (secondary outcomes) immediately following the intervention that were maintained 6 months after the intervention ended (see Table 3). For interpersonal agency, the change from T1 to T2 was not significant, but the change from T1 to T3 was significant. No changes were observed over time for chronic pain disability.

Table 3.

Changes in Health and Quality of Life.

| Preintervention (N = 152) |

Postintervention (N = 88) |

6-Month Follow-Up (N = 79) |

Effect Size p Value Pre–Post |

Effect Size p Value Pre to 6 Months |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | 38.72 | 42.81 | 42.51 | 0.36 p < .001 |

0.33 p < .001 |

| Trauma symptoms | 49.05 | 43.86 | 42.49 | −0.32 p = .001 |

−0.40 p < .001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 28.25 | 22.85 | 23.94 | −0.34 p < .001 |

−0.28 p = .001 |

| Social support | 46.86 | 51.10 | 49.39 | 0.44 p < .011 |

0.26 p = .001 |

| Mastery | 23.56 | 25.03 | 25.72 | 0.27 p = .011 |

0.40 p < .001 |

| Personal agency | 24.32 | 26.20 | 26.49 | 0.35 p < .001 |

0.40 p < .001 |

| Interpersonal agency | 14.67 | 15.88 | 15.46 | 0.29 p = .002 |

0.19 p = .070 |

| Chronic pain | 49.23 | 44.15 | 48.35 | −0.17 p = .082 |

−0.03 p = .781 |

Intervention Costs

The intervention costs were $2,528 per woman. The majority of the costs were staff time (80%).

Experiences of the Intervention

Overall, the women were profoundly positive about the intervention. The women valued having time with the nurses, being listened to, and not being judged, often contrasting the intervention with prior experiences with health care providers and programs. Many spoke about developing trust, which in turn allowed them to “open up” and develop more confidence about speaking up for themselves.

The trusting issue was a really big, #1 big for me. Yeah, so my nurse really helped me along with that.

The best part was being able to talk to [my nurse] . . . it was nice to just sit there. . . And being able to talk to her about anything and not be rushed.

It took me a while to trust. My nurse was. . . it took me a few times to see her in order for me to open up and talk. And now I felt, I felt good after I opened up. You know the stuff that was going on with me, she was listening.

I feel much more confident to speak to people in authority. I feel like I’m more open now with like my doctors, my nurses and stuff like that.

Second, most women appreciated the Indigenous approaches used in ROS including the cultural teachings and the guidance and leadership of the Elders. The women also gained from engaging with other women in group activities. In combination with the support from the Elders and nurses, women felt they could engage more safely with a wider range of people.

I feel like I am more open now with people in general. . . I feel like I have more confidence. . . Like more inner confidence. I feel more accepted. I feel like I am better able to start friendships now. That’s always been a problem. Even if I can start a friendship, I can’t maintain it always. . . and I feel I have grown a lot in that way. It’s easier for me now. I feel I have learned more social skills.

Despite the overall positive experience, there were various tensions throughout. Most frequently, there were tensions related to different expectations—the women initially did not know what to expect from the intervention, especially from their time with the nurses. They also had different understandings regarding what was “allowed” (such as how much time they could have with the nurse, or whether the nurse could buy them coffee or lunch). Importantly, throughout the intervention, tensions arose in the group setting. There were often struggles related to different opinions about cultural protocols (both among women and between the women and the Elders) and related to substance use issues (whether women who were using should be allowed to participate, difficulties for women witnessing other women using or talking about using). Finally, some women experienced mismatches between themselves and their nurse or Elder, but for those who actively participated, they felt that they benefited despite such mismatches.

The women had a number of recommendations for improving the intervention, which they often referred to as a program. Some wanted the program to be longer and the Circles to be more frequent, and some wanted more structure in the Circles. Some women thought the nurses needed better training about substance use and community resources and that the Elders needed more training in managing groups; others wanted more cultural teachings.

In sum, those who participated reported benefits and were positive about their experiences which have been described more fully, along with a discussion of the limitations and challenges, in a documentary (https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=19&v=hQcmRmBYNqY)

Limitations

The women’s refusal to participate in a delayed intervention group to permit the planned crossover design, and the high attrition rate are the greatest limitations. These limitations are due in part to historical and ongoing exploitive treatment of Indigenous people by researchers, locally and more generally, leading to distrust of research in the community, the lack of fit between conventional research methods and Indigenous ways of knowing, and the conditions of the women’s lives. Elsewhere, we report on strategies to mitigate these limitations including further privileging Indigenous knowledge (McKenzie, Varcoe, Browne, & Ford-Gilboe, 2018). Some women enrolled but were unable participate, reflecting the extreme economic deprivation and high levels of trauma many Indigenous women face (Benoit et al., 2016; Daoud et al., 2013; Kubik, Bourassa, & Hampton, 2009). For many women who did participate, high levels of support were required from the nurses to remind women of appointments and the Circle schedule, and to help them attend, given the difficult circumstances of their lives and their limited resources and poor health (e.g., over half had histories of head injuries and memory problems). Recognizing these limitations, this study was able to engage diverse Indigenous women living with high levels of trauma and living in highly marginalizing conditions, despite the challenging circumstances of their lives. Although the study drew participants from only two cities in one Canadian province, the diversity of the Indigenous identities of the participants and the fact that the majority of Indigenous people in Canada live in urban settings (Statistics Canada, 2017) enhance the potential applicability of the findings.

Discussion and Implications

The findings suggest that the health of Indigenous women who have experienced IPV can be supported effectively. Similar to the smaller iHEAL feasibility studies (Wuest et al., 2015), significant improvements in QOL and trauma symptoms were achieved and maintained after 6 months and similar patterns of improvement were noted for five of six secondary outcomes. Furthermore, these improvements were achieved at a similar cost. The cost appears slightly lower than for the previous feasibility studies because, in keeping with an ITT analysis, the cost was spread over all study participants, whereas in the feasibility studies, we pro-rated the costs based on level of participation.

Importantly, chronic pain disability did not change over time. Pain disability declined initially (T1-T2), but not significantly. Despite increased training and attention to chronic pain by the nurses, as with the pilot (Varcoe et al., 2017) and the New Brunswick feasibility study (Wuest et al., 2015), iHEAL does not seem to impact pain. In part, this is likely due to the long-term, intractable nature of chronic pain in the context of IPV (Wuest et al., 2010) and the relatively short duration of the intervention. We did observe a significant improvement in disabling chronic pain over a 12-month period in the small (n = 29) pilot study of iHEAL in Ontario, but it was conducted under ideal conditions in a well-resourced city, which may have affected the results. Future research and programming must integrate effective pain assessment and management strategies and reassess whether such changes result in improvements in chronic pain.

Interpersonal agency improved initially, but was not sustained. This may be understandable given that the IAS taps into relationships with others, something over which women may have limited control. The qualitative interviews suggested that the greatest impact for the women was increased trust and openness with others, which may require time to develop within existing social circles. This aligns with the findings of a systematic review of posttraumatic growth in survivors of interpersonal violence. The findings suggested that the mean prevalence of growth in interpersonal violence survivors is around 71% (range = 58%-99%). Survivors reported growth in all domains, “personal strength,” “new possibilities,” “experience of relationships with others,” and “outlook on life,” with the highest level of growth consistently being experienced in the “appreciation of life” domain (Elderton, Berry, & Chan, 2017). Clearly, research and programs need an ongoing emphasis on supporting posttraumatic growth for women who experience IPV.

The integration of Elders and elder-led Circles was an innovative approach that distinguished the intervention as uniquely designed for Indigenous women. As noted, actively engaging Elders have shown potential for supporting the well-being of women exposed to IPV (Jackson et al., 2015; Lester-Smith, 2013; Puchala et al., 2010). A recent study of the impacts of Elders providing primary care showed significant improvements for Indigenous patients’ mental health, including lower levels of suicidality (Hadjipavlou et al., 2018; Tu et al., Forthcoming), and suggested that Elders could effectively support Indigenous people, even when they did not share language, culture, or traditions. The qualitative data in the current study suggest that for many women, the opportunity to connect with Elders was key to their evolving identities as Indigenous women, and for some, a reconnection to culture.

The use of Circles allowed sharing of cultural practices and traditions, and brought women together, with the potential of enhancing social support, which has been identified as a key variable in recovery of women from IPV and in reducing the symptoms of depression and enhancing self-esteem (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2009; Liu, Dore, & Amrani-Cohen, 2013). The qualitative data suggested that many women deeply appreciated being able to connect with other women with similar experiences, and for some, supportive relationships evolved beyond the intervention. Group-based IPV interventions are increasingly being recognized for their effectiveness on many counts including their cost-effectiveness and ability to offer immediate access to a network of women at a similar stage of recovery that allows for validation of experiences and reduced feelings of self-blame and isolation (Fritch & Lynch, 2008; Liu et al., 2013). Community-based trauma-informed group interventions that encourage women to tell their stories and break the silence of isolation and fear imposed by their abusers (Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013) have taken a variety of forms over time including those focused on mindfulness, spirituality, and yoga therapy to allow for rebuilding of self and agency (Allen & Wozniak, 2010; Clark et al., 2014; Crowder, 2016; Nolan, 2016). For example, in a small exploratory study in the United States, Allen and Wozniak (2010) showed that a group-based IPV intervention, drawing on alternative healing approaches including prayer, meditation, yoga, creative visualization, and art therapy, allowed women to “step away from an identity embedded in trauma and violence toward a sense of self embedded in wholeness, health, and strength”(p. 39). Group interventions have been argued as particularly beneficial when participants have some common ground such as being mothers exposed to IPV (Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013; Grip, Almqvist, & Broberg, 2011) or belonging to particular cultural or religious group (Singh & Hays, 2008; Sweifach & Heft-LaPorte, 2007). Studies show that women of racialized groups often have negative experiences with services, distrust individual counseling, and value collectivism, contributing to group interventions being seen as particularly beneficial (Singh & Hays, 2008; Sweifach & Heft-LaPorte, 2007). However, in ROS, despite attending to feedback from the pilot study and the efforts of Elders and nurses to limit the sharing of traumatizing stories and the harms related to substance use, the Circles were a significant source of tension for the women, Elders, and nurses. Using a group approach requires attention to and training for effective, safe group facilitation, and maybe beyond the scope of what can be achieved within an individually tailored intervention.

This study provides further evidence that iHEAL is a promising intervention and suggests testing with a comparison group is warranted. It further suggests that iHEAL can be successfully tailored for Indigenous women. However, the number of women who could not participate, despite interest, discontinued or required very high levels of support points to the need for different or more intensive approaches for women who are most highly marginalized by poverty and racism.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of many team members, including Angela Heino, Janina Krabbe, and Marilyn Merritt Gray. In particular, their steering committee of Indigenous women with diverse relevant expertise guided the study throughout: Linda Day, Jane Inyallie, Roberta Price, and Madeleine Dion Stout. Madeleine Dion Stout is positioned as the senior author in recognition of her foundational conceptualization and guidance of this study. Most importantly, they acknowledge the contributions of the women who participated in the study who provided extensive input formally and informally, and continue to do so.

Author Biographies

Colleen Varcoe, RN, PhD, is a professor in the School of Nursing, The University of British Columbia. Her research focuses on violence and inequity, and includes studies of organizational interventions to promote equity, including fostering cultural safety, trauma and violence informed care, and harm reduction.

Marilyn Ford-Gilboe, RN, PhD, FAAN, holds the women’s health research chair in Rural Health, Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing, Western University. Her research focuses on health equity and quality of life among women afffected by intimate partner violence in diverse contexts and includes studies testing safety and health interventions, and the measurement of gender-based violence and equity-oriented care.

Annette J. Browne, RN, PhD, is a professor at the School of Nursing, The University of British Columbia. Her research focuses on health inequities, and includes studies on organizational interventions to improve health and health care for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, cultural safety, and strategies to mitigate racism and other forms of discrimination in health care.

Nancy Perrin, PhD, director of the biostatistics and methods core, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, is an expert in the application of multivariate statistical techniques to health outcomes with an emphasis on violence against women both domestically and internationally. Previously, she was the senior director of research, data, and analysis at the Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

Vicky Bungay, RN, PhD, is an associate professor and the director of the Capacity Research Unit in the School of Nursing, The University of British Columbia. She holds a Canada research chair (Tier 2) in gender, equity, and community engagement and her work is further supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award program.

Holly McKenzie, MA, is a PhD candidate in interdisciplinary studies and research trainee with the School of Nursing, The University of British Columbia. She engages diverse quantitative and qualitative approaches to generate knowledge and promote transformative change. Her research focuses on reproductive justice and injustice, as well as structural and interpersonal violence.

Victoria Smye, RN, PhD, is an associate professor and the director of the Arthur Labatt Family School of Nursing at Western University. Her research focuses on mental health and inequity with a primary focus in the area of Indigenous health.

Roberta Price is an Indigenous Coast Salish Elder of Snuneymux and Cowichan heritage. She serves as an Elder in a number of clinical settings and has been a researcher at the School of Nursing, The University of British Columbia, for the past 15 years.

Jane Inyallie is Tse’khene First Nations from McLeod Lake, BC. She has been a counselor at Central Interior Native Health in Prince George for over 20 years. She draws on poetry writing as a process of healing and incorporates art in her work with people.

Koushambhi Khan, PhD, is a senior research manager at the School of Nursing, The University of British Columbia. Over the past 15 years, she has worked on several research projects involving immigrant and Indigenous communities with a focus on equity in health and heath care.

Madeleine Dion Stout, MA, BN, is a Cree speaker and honorary professor at the School of Nursing, The University of British Columbia. She has served in various key positions including as the president of the Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association (formerly the Aboriginal Nurses Association) of Canada and vice-chair of the Board of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, and has received numerous awards. Her involvement in research has shaped the way equity is understood for Indigenous women.

All dollar figures are Canadian dollars.

The Indian Act of 1876 is the original Canadian federal legislation designed to assimilate and govern “Indians,” the colonial term used to refer to First Nations peoples. The Indian Act has been amended several times but remains an actively applied legislation containing all federal policies and regulations pertaining to people who are “registered status Indians” (Government of Canada, 2018). 1

“Circle” refers to a practice common to many Indigenous groups of formally sitting or standing together for a purpose, such as sharing stories, healing practices, and ceremonies and traditions; Circles are often guided by traditions and include ceremonies.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Institute for Aboriginal Peoples Health (funding reference number, MOP-111188).

References

- Ali J., Avison W. R. (1997). Employment transitions and psychological distress: The contrasting experiences of single and married mothers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 345-362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen K., Wozniak D. (2010). The language of healing: Women’s voices in healing and recovering from domestic violence. Social Work in Mental Health, 9, 37-55. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2010.494540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Anaya J. (2012). Report of the special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Retrieved from http://unsr.jamesanaya.org/docs/annual/2012_hrc_annual_report_en.pdf

- Anderson C. (2003). Evolving out of violence: An application of the Transtheoretical Model of Behavioral Change. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 17, 225-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. (2001). A recognition of being: Reconstructing native womanhood. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Sumach Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews F. M., Withey S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: The development and measurement of perceptual indicators. New York, NY: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo K., Lundahl B., Butters R., Vanderloo M., Wood D. S. (2017). Short-term interventions for survivors of intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18(2), 155-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit A. C., Cotnam J., Raboud J., Greene S., Beaver K., Zoccole A., . . . Loutfy M. (2016). Experiences of chronic stress and mental health concerns among urban Indigenous women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19, 809-823. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0622-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D., Fink L. (1998). Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard E. B., Jones-Alexander J., Buckley T. C., Forneris C. A. (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 669-673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassard R., Montminy L., Bergeron A., Sosa-Sanchez I. (2015). Application of intersectional analysis to data on domestic violence against Aboriginal women living in remote communities in the Province of Quebec. Aboriginal Policy Studies, 4, 3-23. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brownridge D. A., Taillieu T., Afifi T., Chan K. L., Emery C., Lavoie J., Elgar F. (2017). Child maltreatment and intimate partner violence among indigenous and non-indigenous Canadians. Journal of Family Violence, 32(6), 607-619. doi: 10.1007/s10896-016-9880-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette C. E. (2016). Historical oppression and indigenous families: Uncovering potential risk factors for indigenous families touched by violence. Family Relations, 65, 354-368. doi: 10.1111/fare.12191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bybee D. I., Sullivan C. M. (2002). The process through which an advocacy intervention resulted in positive change for battered women over time. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 103-132. doi: 10.1023/a:1014376202459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bybee D. I., Sullivan C. M. (2005). Predicting re-victimization of battered women 3 years after exiting a shelter program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 85-96. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6234-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. (1993). Violence against women survey highlights and questionnaire package. Retrieved from www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/instrument/3896_Q1_V1-eng.pdf

- Chang J. C., Cluss P. A., Ranieri L., Hawker L., Buranosky R., Dado D., . . . Scholle S. H. (2005). Health care interventions for intimate partner violence: What women want. Womens Health Issues, 15(1), 21-30. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielowska M., Fuhr D. C. (2017). Intimate partner violence and mental ill health among global populations of Indigenous women: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52, 689-704. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1375-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C. J., Lewis-Dmello A., Anders D., Parsons A., Nguyen-Feng V., Henn L., Emerson D. (2014). Trauma-sensitive yoga as an adjunct mental health treatment in group therapy for survivors of domestic violence: A feasibility study. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 20, 152-158. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowder R. (2016). Mindfulness based feminist therapy: The intermingling edges of self-compassion and social justice. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 35, 24-40. doi: 10.1080/15426432.2015.1080605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud N., Smylie J., Urquia M., Allan B., O’Campo P. (2013). The contribution of socio-economic position to the excesses of violence and intimate partner violence among aboriginal versus non-Aboriginal Women in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 104, e278-e283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. (2017). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Devries K. M., Mak J. Y., Bacchus L. J., Child J. C., Falder G., Petzold M., . . . Watts C. H. (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), 1-11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton W. W., Smith C., Ybarra M., Carles M., Tien A. (2004). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). In Maruish M. (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for the treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 363-377). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C. I., Murphy C. M., Whitaker D. J., Sprunger J., Dykstra R., Woodard K. (2013). The effectiveness of intervention programs for perpetrators and victims of intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 4, 196-231. [Google Scholar]

- Egan M., Bambra C., Petticrew M., Whitehead M. (2009). Reviewing evidence on complex social interventions: Appraising implementation in systematic reviews of the health effects of organisational-level workplace interventions. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63, 4-11. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.071233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft M. K., Cohen P., Brown J., Smailes E., Chen H., Johnson J. G. (2003). Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 741-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elderton A., Berry A., Chan C. (2017). A systematic review of posttraumatic growth in survivors of interpersonal violence in adulthood. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 18(2), 223-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T. (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/Native Alaska communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 316-338. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finfgeld-Connett D. (2015). Qualitative systematic review of intimate partner violence among native Americans. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36, 754-760. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1047072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M., Merritt-Gray M., Varcoe C., Wuest J. (2011). A theory-based primary health care intervention for women who have left abusive partners. Advances in Nursing Science, 34(3), 198-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M., Wuest J., Varcoe C., Merritt-Gray M. (2006). Translating research. Developing an evidence-based health advocacy intervention for women who have left an abusive partner. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 38(1), 147-167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe M., Wuest J., Varcoe C., Davies L., Merritt-Gray M., Campbell J., Wilk P. (2009). Modelling the effects of intimate partner violence and access to resources on women’s health in the early years after leaving an abusive partner. Soc Sci Med, 68(6), 1021-1029. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritch A., Lynch S. (2008). Group treatment for adult survivors of interpersonal trauma. Journal of Psychological Trauma, 7, 145-169. doi: 10.1080/19322880802266797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. (2018). Justice Laws Website. Indian Act. Retrieved from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/page-2.html#h-5

- Graham-Bermann S. A., Miller L. E. (2013). Intervention to reduce traumatic stress following intimate partner violence: An efficacy trial of the Moms’ Empowerment Program (MEP). Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 41, 329-349. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2013.41.2.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grip K., Almqvist K., Broberg A. (2011). Effects of a group-based intervention on psychological health and perceived parenting capacity among mothers exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV): A preliminary study. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 81, 81-100. doi: 10.1080/00377317.2011.543047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjipavlou G., Varcoe C., Tu D., Dehoney J., Price R., Browne A. J. (2018). “All my relations”: Experiences and perceptions of Indigenous patients connecting with Indigenous Elders in an inner city primary care partnership for mental health and well-being. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 190, E608-e615. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.171390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty L. A., Goodman L. A. (2003). Stages of change-based nursing interventions for victims of interpersonal violence. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 32, 68-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P. (2015). Lessons from complex interventions to improve health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36, 307-323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty K., Sheehan M., Schonfeld C. (1999). A multidimensional definition of partner abuse: Development and preliminary validation of the Composite Abuse Scale. Journal of Family Violence, 14, 399-415. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson E. L., Coleman J., Sweet Grass D. (2015). Threading, stitching, and storytelling: Using CBPR and Blackfoot knowledge and cultural practices to improve domestic violence services for First Nations Women. Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 4, 1-27. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. M., Zlotnick C., Perez S. (2011). Cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD in residents of battered women’s shelters: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 542-551. doi: 10.1037/a0023822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolahdooz F., Nader F., Yi K. J., Sharma S. (2015). Understanding the social determinants of health among Indigenous Canadians: Priorities for health promotion policies and actions. Global Health Action, 8. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol-McLain J., Vandal A. C., Wilson D., Nada-Raja S., Dobbs T., McLean C., . . . Glass N. E. (2018). Efficacy of a web-based safety decision aid for women experiencing intimate partner violence: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19, e426-e426. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubik W., Bourassa C., Hampton M. (2009). Stolen sisters, second class citizens, poor health: The legacy of colonization in Canada. Humanity & Society, 33, 18-34. doi: 10.1177/016059760903300103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuokkanen R. (2015). Gendered violence and politics in indigenous communities. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17, 271-288. doi: 10.1080/14616742.2014.901816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan J. (2015). From taboo to epidemic: Family violence within aboriginal communities. Global Social Welfare, 2, 1-8. doi: 10.1007/s40609-014-0003-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lagdon S., Armour C., Stringer M. (2014). Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5, Article 24794. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.24794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester-Smith D. (2013). Healing aboriginal family violence through aboriginal storytelling. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9, 309-321. doi: 10.1177/117718011300900403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S., Glenton C., Oxman A. D. (2009). Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: Methodological study. British Medical Journal, 339, b3496. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Dore M., Amrani-Cohen I. (2013). Treating the effects of interpersonal violence: A comparison of two group models. Social Work With Groups, 36, 59-72. doi: 10.1080/01609513.2012.725156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matamonasa-Bennett A. (2014). “A disease of the outside people” Native American men’s perceptions of intimate partner violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39, 20-36. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie H. A., Varcoe C., Browne A. J., Ford-Gilboe M. (2018). Context matters: Promoting Inclusion in an inner city context. In Klodawsky F., Andrew C., Siltanen J. (Eds.), Social development research to promote inclusion in canadian cities (pp. 83-110). Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan C. R. (2016). Bending without breaking: A narrative review of trauma-sensitive yoga for women with PTSD. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 24, 32-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton I. M., Manson S. M. (1997). Domestic violence intervention in an urban Indian health center. Community Mental Health Journal, 33, 331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker B., McFarlane J. (1991). Nursing assessment of the battered pregnant woman. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 16, 161-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Radabaugh C. W. (1976). Economic strains and the coping function of alcohol. American Journal of Sociology, 82, 652-663. doi: 10.1086/226357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Schooler C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19, 2-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen J. S., Malcoe L. H., Pulkingham J. (2013). Explaining aboriginal/non-aboriginal inequalities in postseparation violence against Canadian women: Application of a structural violence approach. Violence Against Women, 19, 1034-1058. doi: 10.1177/1077801213499245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2016). The chief public health officer’s report on the state of public health in Canada 2016—A focus on family violence in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/2016-focus-family-violence-canada.html

- Puchala C., Paul S., Kennedy C., Mehl-Madrona L. (2010). Using traditional spirituality to reduce domestic violence within aboriginal communities. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16, 89-96. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riel E., Languedoc S., Brown J., Gerrits J. (2016). Couples counseling for aboriginal clients following intimate partner violence: Service providers’ perceptions of risk. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60, 286-307. doi: 10.1177/0306624x14551953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B., Gielen A. (2017). Integrated multicomponent interventions for safety and health risks among Black female survivors of violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1524838017730647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (1996). Using qualitative methods in intervention studies. Research in Nursing & Health, 19, 359-364. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Hays D. (2008). Feminist group counseling with South Asian women who have survived intimate partner violence. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 33, 84-102. doi: 10.1080/01933920701798588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. C., Kohn S. J., Savage-Stevens S. E., Finch J. J., Ingate R., Lim Y. O. (2000). The effects of interpersonal and personal agency on perceived control and psychological well-being in adulthood. The Gerontologist, 40, 458-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]