Keywords: DRA, human enteroids, NHE3, proteomics, shear stress

Abstract

There is increasing evidence that the study of normal human enteroids duplicates many known aspects of human intestinal physiology. However, this epithelial cell-only model lacks the many nonepithelial intestinal cells present in the gastrointestinal tract and exposure to the mechanical forces to which the intestine is exposed. We tested the hypothesis that physical shear forces produced by luminal and blood flow would provide an intestinal model more closely resembling normal human jejunum. Jejunal enteroid monolayers were studied in the Emulate, Inc. Intestine-Chip under conditions of constant luminal and basolateral flow that was designed to mimic normal intestinal fluid flow, with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) on the basolateral surface and with Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin only on the luminal surface. The jejunal enteroids formed monolayers that remained confluent for 6–8 days, began differentiating at least as early as day 2 post plating, and demonstrated continuing differentiation over the entire time of the study, as shown by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and Western blot analysis. Differentiation impacted villus genes and proteins differently with early expression of regenerating family member 1α (REG1A), early reduction to a low but constant level of expression of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1), and increasing expression of sucrase-isomaltase (SI) and downregulated in adenoma (DRA). These results were consistent with continual differentiation, as was shown to occur in mouse villus enterocytes. Compared with differentiated enteroid monolayers grown on Transwell inserts, enteroids exposed to flow were more differentiated but exhibited increased apoptosis and reduced carbohydrate metabolism, as shown by proteomic analysis. This study of human jejunal enteroids-on-chip suggests that luminal and basolateral flow produce a model of continual differentiation over time and NaCl absorption that mimics normal intestine and should provide new insights in intestinal physiology.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study showed that polarized enteroid models in which there is no basolateral Wnt3a, are differentiated, regardless of the Wnt3a status of the apical media. The study supports the concept that in the human intestine villus differentiation is not an all or none phenomenon, demonstrating that at different days after lack of basolateral Wnt exposure, clusters of genes and proteins exist geographically along the villus with different domains having different functions.

INTRODUCTION

In vitro cell culture models studied as monolayers in conventional platforms, usually Transwell inserts, are widely used to study human intestinal physiology and disease. However, conventional cell culture methods do not incorporate the mechanical forces that intestinal cells are exposed to in intact tissue, thus representing one of the limits of these models to mimic the normal in vivo intestine (34). The recent development of organ-on-a-chip technology has provided the potential for the development of new platforms that appear to, more accurately, model the in vivo microenvironments and associated functional capabilities of human living cells. One of the strengths of these techniques is that they allow the application of mechanical forces, especially fluid shear stress, and also mechanical strain, which have been shown to alter the physiological functions and structure of in vitro cells of multiple types (4, 26, 27.) These systems can be used to enable direct fluidic connection of multiple organ-chips, each modeling a different human tissue or organ (38). Human organs-on-chips have the potential for further defining aspects of physiology, pathophysiology, pharmacology, and toxicology, although the extent of their contribution to these studies requires further evaluation (19, 38, 40).

As part of the human organs-on-chips initiative, there have been a number of advances in the development of platforms for intestinal cells (25). To date, a number of studies have reported the use of these platforms exposed to mechanical forces with Caco-2 cells (16, 17) and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived organoids (41). However, these cells have limitations as models of normal segment-specific human intestine. Specifically, Caco-2 cells are a colon cancer cell line and do not fully recapitulate the physiological functions of the small intestine. In terms of iPSC-derived organoids, there have been concerns with their differentiation status into specific parts of the gut and they appear to represent a fetal- or neonatal-like genotype even when matured by exposure to murine vascular beds (9, 31). Human enteroids are primary cultures of intestinal epithelial cells derived from intestinal leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5)+ stem cells. They appear to faithfully recapitulate the physiology and pathophysiology of native, segment-specific intestinal epithelium and potentially provide a model that more closely mimics the normal human intestine, compared with Caco-2 cells and iPSC-derived organoids, as they are currently used (8, 15, 42, 43, 44). Recently, a growing but still limited number of studies have reported polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based chip platforms that exposed human enteroid monolayers from duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon to mechanical forces and resulted in the development of well-differentiated epithelial monolayers with some more differentiated characteristics compared with the other existing human cell models (12, 16, 29, 33, 36). However, multiple additional conditions are still being tried with these platforms, as is their use with coculture of other intestinal cells in addition to the enteroids, all of which are attempting to make these models more closely resemble the normal intestine (18, 24).

We now report effects of further changes in conditions used with the Jejunum-Intestine-Chip using polarized human jejunal enteroid monolayers that are derived from a healthy adult donor and a microengineered system (Emulate, Boston, MA) that allows continuous luminal and basolateral fluid flow and exposure to cyclic mechanical strain. In culture with basolateral media lacking Wnt3A, but with Wnt3A present in the apical media at a time before tight junction formation, the enteroids rapidly differentiated to form highly functional epithelial cells with characteristics of mature villus epithelium. These conditions can be used to study both normal physiologic functions, including Na+ and Cl− absorption, which occur in the jejunal intestinal villus.

METHODS

Cell Culture

The study of human enteroids was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (NA_00038329). This study used jejunal enteroids derived from a healthy adult donor following a protocol that was described previously (8, 42). This enteroid was from a 25-yr-old healthy female with type A blood and has been studied in detail in both three-dimensional (3-D) and two-dimensional formats (8, 18, 33). Crypt cells were isolated from endoscopic biopsies for the development of enteroids. Enteroids were embedded in Matrigel, propagated using expansion media that is enriched in Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin, and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C (42). Enteroids were plated either in PDMS-based “Intestine-Chips” (Emulate) or on Transwell inserts (Corning), the latter to develop differentiated enteroid monolayers, using differentiation media that lacks Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin (42). Enteroids grown on Transwell inserts were maintained under static conditions at all times.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in EGM-2 media (Lonza) containing 2% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, hydrocortisone, human fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, human insulin-like growth factor, ascorbic acid, human epidermal growth factor, gentamicin, and heparin. EGM-2 media is widely used for the culture of endothelial cells (1, 23). HUVECs with passage numbers <6 were used for the development of the Intestine-Chip.

Intestine-Chip

Intestine-Chips were provided by Emulate (Boston, MA). Each PDMS chip has an upper chamber and a lower chamber, which are separated by a PDMS porous membrane (14, 15). Membranes were activated following the manufacturer’s instructions and coated with collagen IV (200 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich). HUVECs were plated on the bottom side of the membrane and allowed to attach for at least 2 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Enteroids were retrieved from Matrigel, dissociated into small fragments by TrypLE (Gibco), plated to the top side of the membrane, and allowed to attach overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. The upper chamber and lower chamber were filled with enteroid expansion media and EGM-2 media, respectively. The next day, unattached cells were removed by rigorous washing with media. The Intestine-Chips were then moved to the Human Emulation System (Emulate), which maintained gassing and provided continuous media flow (60 μL/h) in the upper and lower chambers (14, 15). The system included a culture module instrument that holds up to 12 chips and was maintained in a 5% CO2 at 37°C environment. In most studies, enteroids were exposed to continuous media flow (60 μL/h) without cyclic stretch. The growth of enteroids and HUVECs in the Intestine-Chips was monitored using a Keyance BZ-X700 microscope. Images were analyzed using BZ software. For proteomic studies, enteroids in the Intestine-Chips were maintained under static conditions with no media flow (static), exposed to flow (60 μL/h) without cyclic stretch (flow), or exposed to flow plus cyclic stretch (15 Hz, 10% magnitude) by the Human Emulation System (flow plus stretch). The flow rate was set at 60 μL/h to mimic the postprandial cardiac output to the small intestine (33). The frequency and magnitude of cyclic stretch were not amenable to change manually, and there was no change in cyclic stretch during the studies.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

To collect enteroids from the Intestine-Chips, the upper chamber was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) ×3, filled with TrypLE, and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C until cells were detached from the membrane. Cells were resuspended in TrypLE/PBS and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm × 5 min. Before enteroids were collected, HUVECs were collected using the same method to avoid cross contamination. Total RNA was isolated using PureLink RNA Mini kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript VILO Master Mix (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a QuantStudio 12 K Flex real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of gene-specific primers are listed in Table 1. Each sample was studied in triplicate. Human 18S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) was used as the internal control for normalization. Results were quantitated using the 2–ΔΔCT method.

Table 1.

Gene-specific primers for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| ADA | GGGCTGCTGAACGTCATTG | AGGCATGTAGTAGTCAAACTTGG |

| CFTR | GAAGTAGTGATGGAGAATGTAACAGC | GCTTTCTCAAATAATTCCCCAAA |

| DRA | CCATCATCGTGCTGATTGTC | AGCTGCCAGGACGGACTT |

| GPX2 | GAATGGGCAGAACGAGCATC | CCGGCCCTATGAGGAACTTC |

| NKCC1 | AAAGGAACATTCAAGCACAGC | CTAGACACAGCACCTTTTCGTG |

| Ki67 | GAGGTGTGCAGAAAATCCAAA | CTGTCCCTATGACTTCTGGTTGT |

| KRT20 | GGACGACACCCAGCGTTTAT | CGCTCCCATAGTTCACCGTG |

| LGR5 | ACCAGACTATGCCTTTGGAAAC | TTCCCAGGGAGTGGATTCTAT |

| PAT-1 | TCTACCAGTTCATTGTTCAGAGGA | GAGAGGGTAGGTCTTCCAAGG |

| REG1A | GAGAAGCCAACTCAGACTCAG | TGAGACAGAAACATCAGGCAG |

| SI | TTTTGGCATCCAGATTCGAC | ATCCAGGCAGCCAAGAATC |

| SLC2A2 | GCTGCTCAACTAATCACCATGC | TGGTCCCAATTTTGAAAACCCC |

| 18S | GCAATTATTCCCCATGAACG | GGGACTTAATCAACGCAAGC |

ADA, adenosine deaminase; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; DRA, downregulated in adenoma; GPX2, glutathione peroxidase 2; KRT20, keratin 20; LGR5, leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5; NKCC1, Na+/K+/2Cl− co-transporter 1; PAT-1, putative anion transporter-1; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; REG1A, regenerating family member 1; SI: sucrase-isomaltase.

Immunoblotting

Enteroids were collected from the Intestine-Chips as described in Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction and solubilized in lysis buffer containing 60 mM hydroxyethyl piperazine ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA trisodium, 3 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3PO4, and 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein lysates were homogenized by sonication and quantitated using the bicinchoninic acid method. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE on 4%–20% precast gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Blots were blocked with 5% nonfat milk, probed with primary antibodies (Table 2) overnight at 4°C, and IRDye-conjugated secondary antibodies (LI-COR) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized and quantified using an Odyssey CLx imaging system and Image Studio software.

Table 2.

Primary antibodies for immunoblotting and immunofluorescence

| Antigen | Manufacturer | Catalog Number | Host |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromogranin A | Abcam | ab15160 | Rabbit |

| DRA | Santa Cruz | sc-376187 | Mouse |

| E-cadherin | BD | 610182 | Mouse |

| GAPDH | Sigma-Aldrich | G8795 | Mouse |

| MUC2 | Abcam | ab11197 | Mouse |

| NHE3 | Novus | NBP1-82574 | Rabbit |

| NKCC1 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | T4-C | Mouse |

| PECAM-1 | Novus | NB600-562 | Mouse |

| Phospho-Ezrin | Cell Signaling | 3726S | Rabbit |

| Villin | Abcam | ab130751 | Rabbit |

ADA, adenosine deaminase; DRA, downregulated in adenoma; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NHE3, Na+/H+ exchanger 3; NKCC1, Na+/K+/2Cl− co-transporter 1; PECAM-1, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1.

Mass Spectrometry and Biostatistical Evaluation

Proteins were reduced/alkylated and precipitated with DTT/iodoacetomide. After a wash with acetone, protein pellets were reconstituted in triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) and digested with Trypsin/LysC overnight at 37°C. Peptides were labeled with tandem mass tags (TMT) and analyzed by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on nano-LC-Lumos (Thermo Fisher) interfaced with a nano-Acquity LC system (Waters). Tandem MS spectra were processed by Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Fisher). MS/MS spectra were analyzed with Mascot (Matrix Science) Uniprot_Human-180915 database and a small database containing enzymes, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and several nonhuman proteins. Peptide identifications from Mascot searches were processed within Proteome Discoverer to identify peptides with a confidence threshold of 0.01% false discovery rate.

The proteome data derived from two 3-plex TMT labeling analyses using the Proteome Discoverer software were imported into Partek Genomics Suite 7.0 (Partek, Saint Louis, MO) for protein annotation and further analysis. One or more mass spectra were assigned to each National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) RefSeq identifier, which represents a single protein isoform, and for each identifier, the median of these multiple spectra values was calculated to produce a single log2 abundance value representing that protein. Only those spectra with a unique, single RefSeq and Proteome Discoverer Isolation Interference value of <30% were accepted for further evaluation of these 7,784 proteins. The values of each TMT data set’s samples (flow vs. Transwell inserts; flow vs. static growth in Intestine-chip; flow vs. flow plus repetitive stretch) were independently quantile normalized to minimize any noise and experimental variation, and subsequently used in their log2 notation for statistical analysis. Partek Genomics Suite was used to create the principal component analysis (PCA) plots, wherein expression values were in quantile normalized log2 notation.

To determine the relative protein expression levels of the different biological classes in Partek, their quantile normalized log2 values underwent two-tailed two-way ANOVA t test analysis, wherein the TMT run served as the second degree of freedom, assuming a hypothesized mean of 0 change. The proteins’ relative expression was reported as fold change.

To examine differential protein expression, these normalized data were imported into Spotfire DecisionSite with Functional Genomics v9.1.2 (TIBCO Spotfire, Boston, MA). Different pairs of biological samples’ values were compared for each protein/gene yielding linear and log2-fold change values. To characterize these fold changes, their log2 values underwent standard deviation (SD) analyses allowing us to set appropriate fold change thresholds of differential expression. Those proteins whose linear fold changes were >1.5 were considered to be differentially expressed for purposes of functional analysis of pathways and function on the QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) platform.

Immunofluorescence

The upper and lower chambers of the Intestine-Chips were rinsed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. After being blocked/permeabilized by 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% saponin, cells were incubated with primary antibodies (Table 1) overnight at 4°C. The next day, cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher) and secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 568 for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, cells were visualized using an Olympus FV3000RS confocal microscope with a silicon oil objective (×30, NA 1.05).

Measurement of NHE3 and DRA Activities

Measurement of Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) and downregulated in adenoma (DRA) activities were performed using an Olympus FV1000MP two-photon microscope and SNARF intracellular pH (pHi)-sensitive dyes (Molecular Probes), using the experimental setup and objective, as described previously (2).

To determine NHE3 activity, cells were incubated with SNARF-4F and Na+-NH4Cl solution (in mM: 98 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 25 glucose, 20 HEPES, and 40 NH4Cl; pH 7.4) for 30 min in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were then examined using a two-photon microscope with the microfluidic chip connected to a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus). The syringe pump allowed continuous fluid flow through the upper and lower chambers at a constant flow rate of up to 0.75 mL/min. In both chambers, initial perfusion was with tetramethylammonium (TMA)+ solution (138 mM tetramethylammonium chloride (C4H12NCl), 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM glucose, and 20 mM HEPES; pH 7.4) for 10 min. The upper chamber was then perfused with Na+ solution (138 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM glucose, and 20 mM HEPES; pH 7.4) to determine the rate of Na+-dependent pHi recovery. In some experiments, the solutions in the upper chamber were supplemented with Tenapanor, a small-molecule NHE3 inhibitor (3).

To measure DRA activity, cells were incubated with SNARF-1 for 30 min in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were then examined using a two-photon microscope at a flow rate of 0.75 mL/min. The lower chamber was perfused throughout the studies with Cl−-free solution (in mmol/L: 110 Na-gluconate, 5 K-gluconate, 5 Ca-gluconate, 1 Mg-gluconate, 10 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, 1 amiloride, 5 HEPES; 95% O2–5% CO2); the upper chamber was perfused with Cl− solution (in mmol/L: 110 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 10 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, 1 amiloride, 5 HEPES; 95% O2–5% CO2) or Cl−-free solution to allow determination of the rate of Cl−/HCO3− exchange. Multiple rounds of removing/replenishing Cl− in the upper chamber were performed to determine the basal Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity as well as the activity in the presence of a specific DRA inhibitor, DRAinh-A250 (10).

At the end of each experiment, intracellular pH was calibrated using K+ clamp solutions that contained 10 μmol/L nigericin (Cayman Chemical) and were set to specific pHs. Data were analyzed using MetaMorph software. At least 20 areas were picked for analysis for each sample. The rate of initial alkalization following the switch from TMA solution to Na+ solution was calculated to determine NHE3 activity. The rate of initial alkalization following the switch from Cl−-containing to Cl−-free solution was calculated to determine DRA activity.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t tests or ANOVA when more than two comparisons were made. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and results were not significant unless P values were provided. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

Development of Intestine-Chip

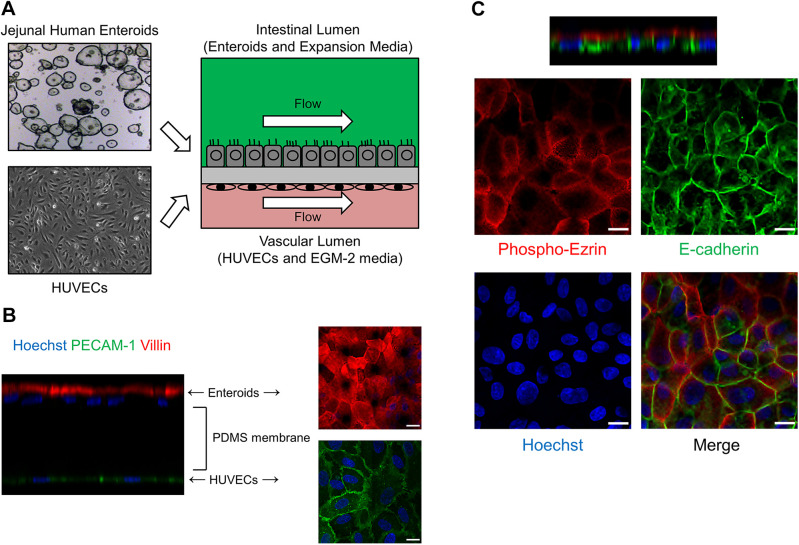

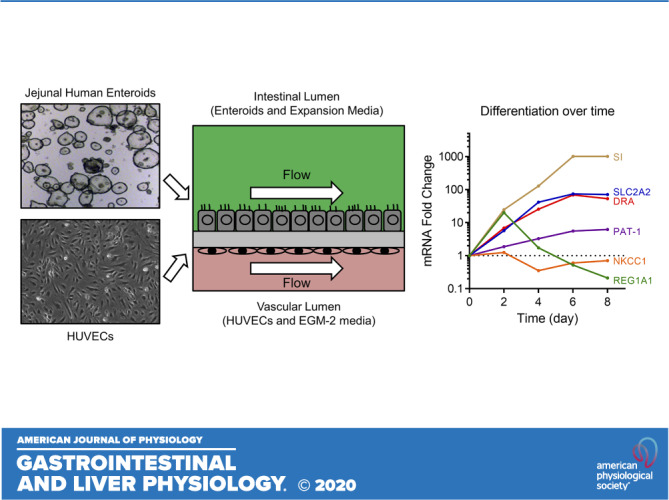

As shown in Fig. 1A, each Intestine-Chip consisted of an intestinal lumen developed with jejunal enteroids and a vascular lumen developed with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in the upper and lower chip channels, respectively. A continuous flow of enteroid expansion media in the upper chamber and EGM-2 media in the lower chamber was controlled by the Human Emulation System, set to mimic intestinal fluid flow (14, 15, 29). Using an intestinal epithelial cell-specific brush-border marker, villin, and an endothelial cell-specific marker, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1), immunofluorescence studies showed that enteroids and HUVECs were separately attached to the two sides of the PDMS membrane and aligned as monolayers (Fig. 1B). The enteroids were normally polarized in the Jejunal-Intestine-Chip, with phospho-ezrin expressed on the apical membrane and E-cadherin expressed on the lateral membrane (Fig. 1C). Enteroids became confluent within 2–3 days after plating and maintained morphological integrity until days 6–8 after plating, when an increasing number of floating apoptotic cells were observed (data not shown). Of note, we did not observe any “villus-like” structures that were reported in the Intestine-Chips using Caco-2 cells, iPSC-derived intestinal organoids, pediatric enteroids, or duodenal enteroids in previous studies (12, 14, 15, 16, 29, 36, 41).

Figure 1.

Development of Intestine-Chip using human adult jejunal enteroids and Human Emulation System. A: schematic of the Intestine-Chip. A two-chamber polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic device (Emulate, Inc., Boston, MA) was used as described previously (14, 15, 29). The upper chamber was used to establish an intestinal lumen using adult jejunal enteroids and enteroid expansion media. The lower chamber was used to establish a vascular lumen using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and EGM-2 media. Continuous media flow was introduced by the Human Emulation System (Emulate, Inc.). B: representative immunofluorescence results (n = 2) showing that villin (red)-positive enteroids and PECAM-1 (green)-positive HUVECs were located in the upper chamber and lower chamber of Jejunal-Intestine-Chip, respectively, separated by a porous PDMS membrane. Scale bar = 15 μm. C: representative immunofluorescence results (n = 2) showing that phospho-ezrin (red) and E-cadherin (green) were expressed on the apical membrane and lateral membrane of enteroids in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip, respectively. Cell nuclei were stained blue with Hoechst 33342. Scale bar = 15 μm.

Progressive Differentiation of Enteroids in Intestine-Chip

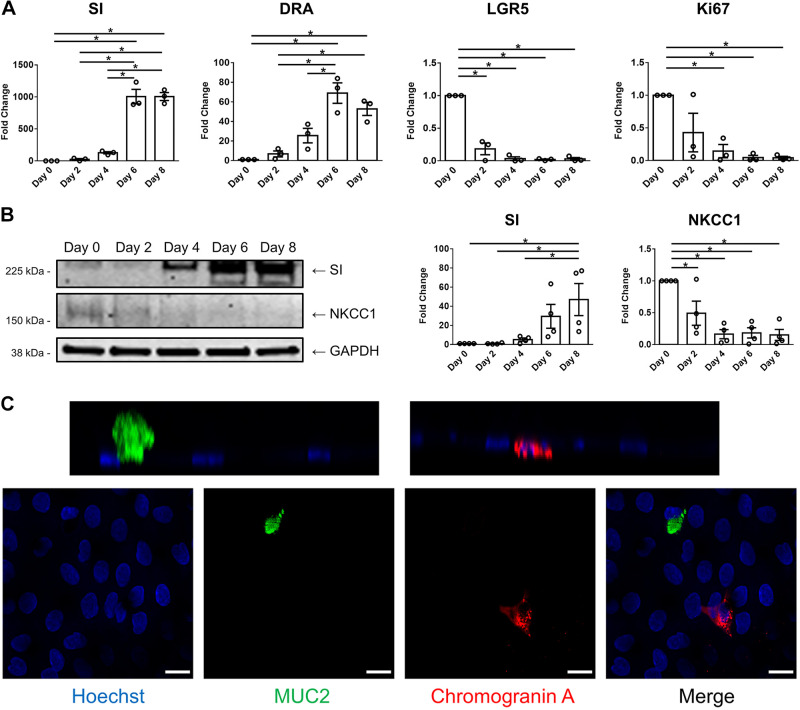

Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin allow maintenance of the stemness of adult intestinal LGR5+ stem cells (5). We previously confirmed that removing Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin from culture media caused differentiation of enteroids, as shown by the presence of absorptive enterocytes, goblet cells, tuft cells, and enteroendocrine cells as well as the appearance of proteins that only occur in the villus and loss of proteins that are only or primarily expressed in the crypt (8, 24, 42). In this study, we used enteroid expansion media that contains Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin only in the intestinal upper channel and EGM-2 media that lacks Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin in the vascular lower channel. The rationale was to determine if apical addition of Wnt-containing media before formation of restrictive tight junctions would allow preservation of the crypt-like state. However, the absence of these factors on the basolateral surface of enteroids resulted in enteroid differentiation that had begun already at the earliest times studied. To examine the state of differentiation, enteroids were collected from Jejunal-Intestine-Chips at different time points post plating and markers of cells normally in the intestinal villus and crypt compartments were determined by qRT-PCR and/or immunoblotting and immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. 2A, the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels of SI and DRA, both of which are enriched in differentiated enteroids, were increased over time in enteroids cultured in the Intestine-Chip, trending upward as soon as day 2 post plating, although only becoming statistically significant by day 6 and peaking on days 6–8 post plating. In contrast, the mRNA levels of LGR5, a marker of intestinal stem cells, and Ki67, a proliferation marker, were decreased starting as soon as day 2 post plating. At the protein level, in parallel with the changes in mRNA level, the amount of SI was increased over time, whereas NKCC1, an ion transport protein that is enriched in undifferentiated enteroids, was reduced (Fig. 2B). On day 6 post plating, differentiated intestinal epithelial cells were observed in enteroids in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip, including mucin 2 (MUC2)-positive goblet cells and chromogranin A-positive enteroendocrine cells (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data suggest that enteroids in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip become differentiated over time, starting by day 2 post plating, and reach maximal differentiation on days 6–8 post plating. The latter follows the well-described life-cycle of intestinal crypt-derived epithelial cells and explains why enteroids in Intestine-Chip did not remain morphologically intact for more than 1 wk. These changes are, at least in part, driven by the use of EGM-2 media that lacks Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin in the vascular channel. Based on these findings, day 6 post plating was selected as the time for subsequent functional studies, as the enteroids at this time point were differentiated and not overwhelmingly apoptotic.

Figure 2.

Human adult jejunal enteroids in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip continue to differentiate over time. A: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) results showing that the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels of sucrase-isomaltase (SI) and downregulated in adenoma (DRA, SLC26A3) were increased in enteroids in Intestine Chip after plating, peaking at days 6–8. In contrast, leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor (LGR5) and Ki67 were decreased over time. Human 18S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) was used as the internal control. Day 0 represents undifferentiated enteroids, sampled prior to plating. Results are means ± SE. n = 3 separate experiments; *P < 0.05. B: the protein expression of SI was increased, whereas that of Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) was decreased in enteroids in Intestine-Chip from day 0 to day 8 after plating, as determined by immunoblotting. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the loading control. Results are means ± SE. n = 4 separate experiments; *P < 0.05. C: representative immunofluorescence images (n = 2) showing mature intestinal epithelial cells among enteroids in Intestine-Chip on day 6 after plating, including MUC2 (green)-positive goblet cells and chromogranin A (red)-positive enteroendocrine cells. Cell nuclei were stained blue with Hoechst 33342. Scale bar = 15 μm.

Recently, evidence in mouse intestine has been presented that once epithelial cells differentiate upon leaving the crypt, they undergo further changes as they move up the villus until they undergo apoptosis (22). In detailed studies correlating bulk and single-cell RNAseq, RNA FISH, and immunofluorescence in the mouse small intestine, clustering of proteins by function was demonstrated along the vertical axis, with the suggestion of continuing differentiation as cells move from the villus base to the villus tip (22). Consequently, we characterized the expression of known villus proteins during differentiation of human jejunal enteroids (by comparing expression at the day of plating and days 2, 4, 6, and 8 post plating) to determine if human enteroids exhibited time-dependent stages of differentiation. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S2 our results strongly supported continual differentiation of jejunal enteroids with three distinct patterns of gene/protein expression that paralleled the stages of differentiation identified in mouse small intestine (22). These patterns consisted of the following: 1) levels of regenerating family member 1 (REG1A) were maximally expressed in the murine small intestine villus base, with expression in the human jejunal enteroids at a high level on day 2 post plating and returned to a low level at subsequent days postplating; 2) NKCC1 declined after day 2 post plating but remained present, which is consistent with its expression primarily in the lower villus; 3) putative anion transporter-1 (PAT-1), SLC2A2, and keratin 20 (KRT20) increased dramatically after day 2 post plating, consistent with expression in the mid to upper villus. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) expression did not change over time.

Ion Transport Function of Enteroids in Intestine-Chip

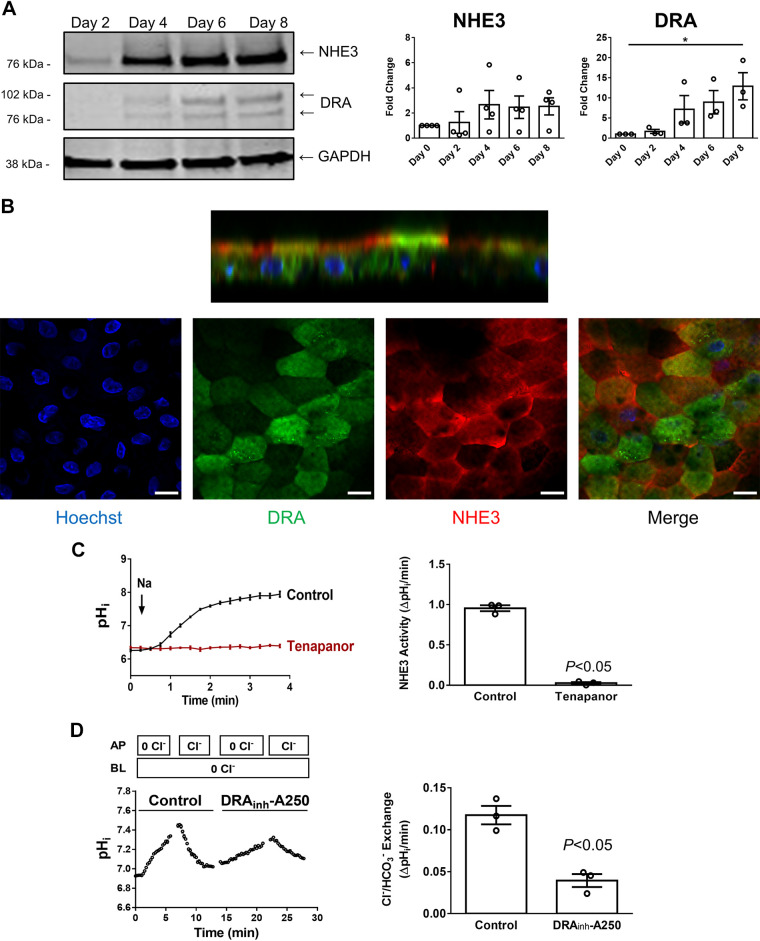

Ion transport is an important physiological function of the small intestine, especially as part of total body salt and water homeostasis in addition to involvement in digestion (6, 7, 42). Several ion transport processes occur primarily in differentiated villus intestinal epithelial cells. These include electroneutral NaCl absorption, which is mediated by two transport proteins, NHE3 (SLC9A3) and DRA (SLC26A3). Dysfunction of NHE3 or DRA is implicated in congenital and infectious diarrheal diseases (11, 13, 20, 21, 32, 35). To determine the usefulness of the Jejunal-Intestine-Chip for quantitation of intestinal sodium and chloride absorption, we studied the protein expression and activities of NHE3 and DRA in enteroid monolayers. Figure 3A shows a trend of increased NHE3 and DRA protein expression over time in enteroids in the Intestine-Chip, consistent with our previous findings that these two proteins were more abundant in differentiated than in undifferentiated enteroids (8, 42). The pattern of increase was similar to other transport proteins demonstrated in Supplemental Fig. S2, increasing in expression as enteroids continued to differentiate. Immunofluorescence studies showed that NHE3 and DRA proteins were mostly located on the apical membrane of enteroids, although a significant intracellular component of DRA was visible by immunofluorescence miscroscopy (Fig. 3B). Importantly, enteroids in the Jejunal-Intestine-Chip (day 6 after plating) exhibited NHE3-mediated Na+/H+ exchange activity that was sensitive to the NHE3 inhibitor, Tenapanor (3), and DRA-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity that was sensitive to the DRA inhibitor, DRAinh-A250 (10) (Fig. 3, C and D). These results further demonstrate that enteroids in the Intestine-Chip are differentiated at a functional level. There was residual Cl−HCO3− exchange activity in the jejunal enteroids after exposure to DRAinh-A250, with approximately the same activity as that of DRA, which is assumed to be due to PAT-1, although this was not evaluated since there was no specific PAT-1 inhibitor or specific PAT-1 antibody available.

Figure 3.

Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) and downregulated in adenoma (DRA) are expressed apically in jejunal enteroid monolayers in Intestine-Chip. A: immunoblot showing that both NHE3 and DRA were upregulated over time postplating at the protein level in enteroids in Intestine Chip. Results are representative (left) and means ± SE of n = 3–4 separate experiments; *P < 0.05 all compared with day 0 (right). B: representative immunofluorescence images (n = 2) showing that NHE3 (red) and DRA (green) were mostly located on the apical membrane of enteroids in Intestine-Chip, although DRA also had a large intracellular component. Scale bar = 15 μm. C: the transport function of NHE3 was determined using two-photon microscopy and intracellular pH dye SNARF-4F. Representative traces (left) show that sodium-dependent intracellular alkalization was detected in enteroids in Intestine-Chip, which was not observed in the presence of Tenapanor (2 μM, apical side), a specific NHE3 inhibitor. Quantitation (right) reveals a dramatic reduction in NHE3 activity in the presence of Tenapanor. Results are representative (left) and means ±SE of n = 3 separate experiments (right). D: the transport function of DRA was determined using two-photon microscopy and intracellular pH dye SNARF-1. Representative traces are shown on the left and quantitation of results on the right. Removal of apical chloride caused intracellular alkalization in enteroids in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip, which was reversible by replenishing apical chloride. DRA played a role in these processes as DRAinh-A250 (5 μM, apical side), a specific DRA inhibitor, significantly reduced the rate of intracellular pH change. However, there was a significant residual component. DRAinh-A250 was present at all times in the perfusion solution. Previous studies showed this compound was able to inhibit ∼100% of DRA activity in human colonoids (37). Results on the right are means ± SE of n = 3 separate experiments.

Mechanical Forces Modulate Protein Expression in Enteroids

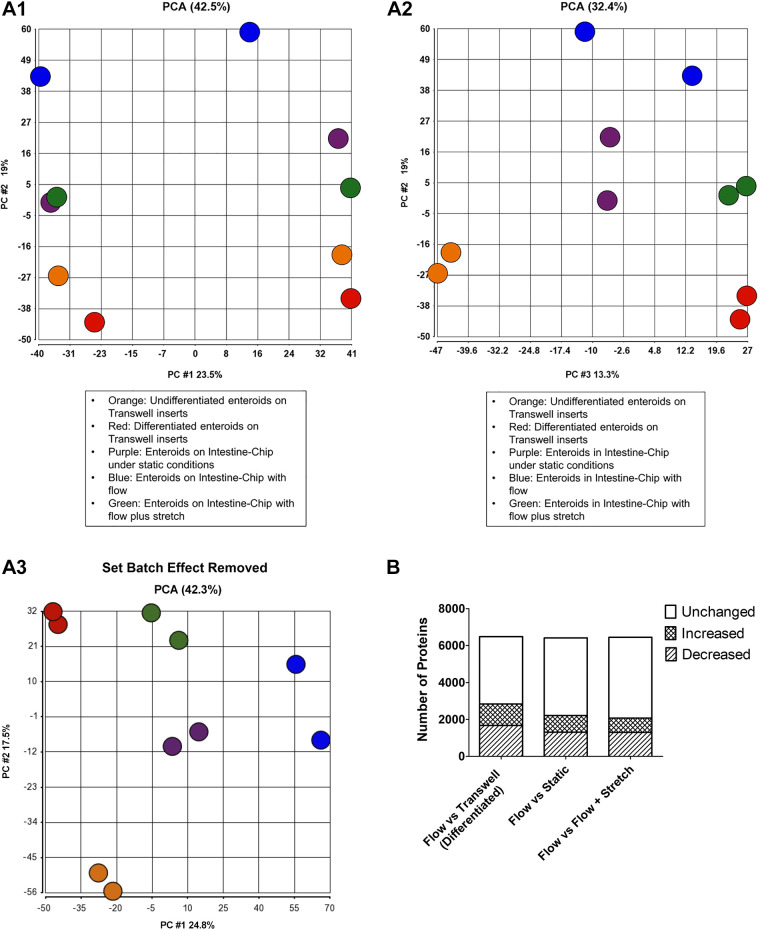

A major function of the Human Emulation System is the ability to apply mechanical forces, including fluid shear stress and cyclic strain, to cells that are grown on Intestine-Chips. Application of these physical forces allowed us to investigate their effects on jejunal epithelial cells using proteomic analysis. As shown in Fig. 4A, principal component analyses (PCA) compared enteroids in Jejunum-Intestine-Chip exposed to flow, flow plus stretch, or studied under static conditions and enteroids from the same subject grown as monolayers in Transwell inserts under differentiated or undifferentiated conditions. The principal component analyses (PCA) showed that enteroids grown under each condition resembled each other more than they resembled enteroids from any of the other growth conditions (see Fig. 4). The biggest differences in protein expression (other than between differentiated and undifferentiated enteroids grown on Transwell inserts) were identified between enteroids in the Jejunal-Intestine-Chip grown under flow conditions compared with differentiated enteroids on Transwell inserts. Intermediate were the enteroids in Jejunum-Intestine-Chip cultured under static conditions and enteroids exposed to flow plus stretch. We speculate that the intermediate level of expression of the enteroids under static conditions indicates only partial effects provided by the Intestine-Chip, whereas the intermediate position of the flow plus stretch condition may indicate partial reversal or even control of the magnitude of the protein expression changes caused by flow alone.

Figure 4.

Mechanical forces modulate the protein signature of enteroids. A: principal component analysis (PCA). The PCA statistical method was used to compare protein expression (shown as clusters) of jejunal human enteroids grown on Transwell inserts under undifferentiated and differentiated conditions (undifferentiated, orange; differentiated, red); the same jejunal enteroids grown in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip under static conditions without flow or repetitive stretching (static, purple), with apical and basolateral flow (flow, blue), and flow plus stretch (flow+stretch, green). Three views (A1, A2, A3) of the top three principal components are displayed in two-dimensional (2-D) plots, which were generated using Partek Genomics Suite analysis software. PCA analysis uses correlation of all the analyzed proteins to depict sets of proteins as components that represent the samples’ similarity along that set’s plot axis. Mass spec analyses show strong technical batch effects for different instrument runs, as seen in the X-axis of A1, labeled “PC #1.” This is the first principal component, which represents the proteins that differentiate the two instrument runs. A2 depicts the second and third components of proteins that tightly group the two runs’ biological replicates together. The Partek Remove Batch Effect tool allows a PCA analysis to exclude extraneous nonbiological effects, in this case instrument run, from consideration, and this was used independently to generate A3, which essentially recapitulates A-2, confirming that the biological replicates group together and that this mass spec analysis distinguishes their underlying biological differences. B: differentially expressed proteins comparing flow vs. Transwell (differentiated), flow vs. static, flow vs. flow plus stretch. Figure shows total proteins expressed for both conditions being compared and the number of proteins that were increased or decreased by at least 1.5 times comparing flow to each of the other three conditions.

The differential expression of proteins was assessed by comparing enteroids grown in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip with flow to those grown in Transwell inserts (differentiated enteroids), and in Intestine-Chip under static conditions or exposed to flow plus stretch. As shown in Fig. 4B, a total of 2,838 out of 6,489 proteins identified in both conditions were differentially expressed by at least 1.5-fold (1,164 proteins induced and 1,674 proteins inhibited) in enteroids in Jejunal Intestine-Chip with apical and basolateral flow compared with the same passage of differentiated enteroids grown on Transwell inserts. Concerning differences in specific pathways or functions, proteins that were increased by flow-included differentiation (proteins with increased expression included sucrase-isomaltase, mucin 1, mucin 3, carbonic anhydrase 1, and chromogranin B), apoptosis, and oxidative phosphorylation (Supplemental Table S1A; all Supplemental material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12749801.v1). As expected, there were multiple processes and functions increased in enteroids grown on Transwell inserts that do not allow application of the mechanical forces. These included 14-3-3 signaling, lipid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, gluconeogenesis, and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling. Minus versus average (MVA) plot of the differentially expressed proteins with specific proteins of interest highlighted is shown in Supplemental Fig. S1A. These data suggest improved maturation and differentiation in enteroids in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip with continuous flow compared with those on Transwell inserts, but there also appears to be some injury from the mechanical force. Of note, it is not clear if these differences are caused by fluid shear stress only or other stimuli that enteroids on Transwell inserts were not exposed to, including HUVECs and the contents in EGM-2 media.

We further investigated whether the addition of mechanical stretch in addition to dynamic flow would result in further changes in the protein expression profiling of the jejunal enteroids. Enteroids in Jejunal-Intestine-Chips with dynamic flow were compared with those exposed to both flow and cyclic stretch. As shown in Fig. 4B, 2,078 proteins out of a total of 6,477 proteins identified in both conditions were differentially expressed by at least 1.5-fold (779 proteins increased and 1,299 proteins decreased) in enteroids in Intestine-Chips with apical plus basolateral flow compared with the same passage of enteroids exposed to both flow plus stretch. There were minimal increases in specific pathways or functions in enteroids exposed to flow compared with flow plus stretch when analyzed for increases of 1.5-fold or higher, although expression of multiple proteins was altered (see MVA plot, Supplemental Fig. S1B). In contrast, enteroids grown under flow plus stretch had increases of 1.5-fold or greater in proteins related to mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) signaling, AMPK signaling, EGF signaling, lipid synthesis, and carbohydrate metabolism, as compared with enteroids exposed to flow alone (Supplemental Table S1B).

In an attempt to dissect the specific effects of mechanical forces from potential effects of the other factors, the proteomes of enteroids grown in the Jejunal-Intestine-Chips under dynamic flow were compared with the same enteroids in Jejunal-Intestine-Chips that were maintained under static conditions. As shown in Fig. 4C and Supplemental Table S1C, a total of 2,215 proteins were differentially expressed by at least 1.5-fold between enteroids exposed to apical and basolateral flow compared with those maintained in static conditions, out of 6,417 total proteins identified in both conditions (903 proteins increased and 1,312 proteins decreased expression) in enteroids in Intestine-Chip with flow compared with the same passage of enteroids grown in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip under static conditions. Proteins upregulated in the enteroids exposed to shear force included those associated with cell death, oxidative phosphorylation, sumoylation, whereas functions and pathways increased in enteroids grown in the Jejunal-Intestine-Chip under static conditions included AMPK signaling, cholesterol synthesis, and lipid metabolism (Supplemental Table S1B and Supplemental Fig. S1B). It is important to note that the Intestine-Chip was not designed to be studied under static conditions, and the experimental design used in this study was applied to better characterize the processes regulated by dynamic flow that can only be applied using the Intestine-Chip system as opposed to static conditions employed by Transwell inserts or other cell culture platforms. Importantly, the differences in the Intestine-Chip studied under static conditions compared with those exposed to mechanical forces could have been caused by lack of nutrients or presence of metabolic products, which are normally washed away by the perfused fluids, in addition to the effects of the mechanical forces themselves. Nonetheless, the increased apoptosis in the presence of shear stress in spite of more adequate nutrients and the removal of metabolic products suggests that this is important to consider in using this methodology.

DISCUSSION

In this study, normal human adult jejunal enteroid monolayers were studied in a PDMS-based organ-chip platform using an automated perfusion/gassing system that included the presence of endothelial cells (HUVECs) on the basolateral surface and continuous apical and basolateral fluid flow, which is called the Human Emulation System (14, 15). In the proteomic studies, the effect of addition of repetitive stretch was also compared. This study used human jejunal enteroids to help further evaluate conditions used to make the enteroid model more closely resemble normal intestine, in this case by adding the mechanical force of flow-related shear stress under conditions in which differentiation was only driven by lack of basolateral Wnt3A. This model produced differentiated enteroids and allowed the study of differentiated, villus-like enterocytes for 6–8 days. Notably, differentiation already started by no later than the day 2 post plating. We elected to study enteroids at day 6 post plating, which was before the appearance of a large number of apoptotic cells but at a time that the cells were differentiated based on the expression of digestive enzymes and transport proteins. The state of differentiation of the intestinal epithelial cells was indicated by their low proliferation rate as indicated by Ki67 expression, the abundance of cells that are present predominantly in the villus and not the crypt, including goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells, reduced expression of proteins that are abundant in the crypt (LGR5 and NKCC1), and increased expression of proteins that are present in the villus (sucrase-isomaltase, NHE3, DRA, PAT-1). In addition, these enteroids had transport functions that are associated with the villus, including apical Na+/H+ exchange carried out by NHE3 and Cl−/HCO3− exchange, which was partially due to apical DRA and probably PAT-1. However, given the differentiated state of the enteroids produced, the enteroids could not be maintained over multiple passages and did not allow for study of the crypt population of enterocytes. Please note that studies were only performed on one jejunal enteroid line, although one that we have studied extensively (8, 24, 33).

The following modifications in the usual conditions used with the Intestine-Chip and what was learned include: 1) The apical presence of Wnt3A, R-Spondin, and Noggin failed to prevent differentiation that started before day 2 post plating. This occurred despite exposure to Wnt3A at least to the lateral membranes given the presence of immature tight junctions present immediately post plating. This indicates the dominant role of exposure of the stem cells at the base of the crypt to the basolateral solution lacking Wnt3A via the 7-μm pores in the separating membrane, in spite of similar flow rates on both the apical and basolateral enteroid surfaces. In future studies, the lack of effectiveness of apical Wnt3A-containing media in maintaining a crypt-like state should allow omission of this more expensive media. 2) The presence of basolateral HUVECs appears to have had a similar effect on intestinal microvascular cells as similar differentiation occurred with both, comparing duodenal and jejunal enteroids in separate studies (14, 15). One of the motivations to use HUVECs was that in developing Body-on-a-Chip in which organoids from multiple organs are connected, having a common endothelial cell and media represents simplifying conditions. Hence, we attribute this rapid differentiation state of the cells to lack of exposure of enteroids to growth factors, especially Wnt3A, from the basolateral surface and not to the HUVECs cultured in the lower channel of the chip. 3) The demonstration that NHE3 and DRA activity could be determined with a two-photon microscope using SNARF dyes as well as the previously used pH-sensitive dye, BCECF (8), indicates another positive characteristic of the optical characteristics of the PDMS Intestine-Chip.

This study also demonstrated that the shear force, generated by flow, enhanced intestinal differentiation, based on the findings showing that enteroids in the Intestine-Chip under flow exhibited a greater level of expression of villus proteins measured in proteomic studies, as well as greater cell height and number of microvilli, than those grown in static conditions in the Transwell inserts (33), the latter being the model most used until now for the study of differentiated enteroids. However, this conclusion must be considered tentative since the shear force was not the only difference between the Intestine-Chip and Transwell inserts conditions, with there being differences in the presence of HUVECs and the nature of the basolateral media. Furthermore, the fact that shear stress was the relevant mechanical force was indicated by jejunal enteroids studied in the Jejunum-Intestine-Chip under conditions of both flow and flow plus stretch, having increased enteroid height and number of microvilli that were not significantly different (33), as well as the relatively minor changes in protein expression in the proteomic studies.

We attribute this rapid differentiation state of the cells to lack of exposure of enteroids to growth factors, especially Wnt3A, from the basolateral surface and not to the HUVECs cultured in the lower channel of the chip. In fact, in similar but still preliminary studies, with the same apical and basolateral flow and media conditions used in the current studies but in the absence of HUVECs (no cells added to the lower channel of the Intestine-Chip), similar differentiation of enteroids occurred, again consistent with lack of basolateral Wnt3A accounting for the rapid differentiation (Yin, Sunuwar, and Donowitz, unpublished observation). This hypothesis was recently supported by the demonstration that in studies with Intestine-Chip using both Caco-2 cells and human proximal colonic enteroids, it was the basolateral flow that affected enterocyte differentiation, with the mechanism suggested as removal of a Wnt-inhibitor under the conditions of flow that were used and which we duplicated in the current studies (29). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the physical forces the enteroids are exposed to when cultured in the Jejunal-Intestine-Chip, support enhanced intestinal differentiation. The latter hypothesis is based on our findings that enteroids cultured in Intestine-Chip under flow exhibited greater levels of differentiation than those grown in Transwell inserts, the latter being the model most used until now for the study of differentiated enteroids.

Differentiation of enterocytes has been thought of occurring at the point the cells emerge from the crypt and ending with cell apoptosis as they reach the villus tip, with the dying tip cells thought to be less functional than the cells further down the villus. Recently, studies with mouse jejunum clarified that differentiation is a continuous process with continued differentiation occurring as cells move from the villus base to the villus tip. Furthermore, multiple areas of protein zonation were demonstrated along the villus resulting in graded functional clustering at multiple domains along the villus, including the villus tip (22). As shown in Supplemental Fig. S2. our results showed that differentiation, at least as primarily indicated by changes in mRNA expression, in the Jejunal-Intestine-Chip started before day 2 post plating and progressed over the time in culture, with different patterns of gene/protein expression. Importantly, expression of multiple classes of proteins examined in jejunum in the Intestine-Chip followed the zonation suggested previously in murine small intestinal villi. This includes expression of REG1A, a protein involved in acute-phase responses and suggested as being present in the villus base to limit access of the microbiota to the crypt; REG1A expression was maximal at day 2 post plating, consistent with presence in the low villus (22). NKCC1 was expressed at significant levels at day 2 post plating but decreased after that, although it was expressed at subsequent times. This is consistent with the demonstrated functional anion secretion present in the lower villus and upper crypt demonstrated in human ileal enteroids (8, 42). In contrast, mRNA expression of sucrase-isomaltase and two transport proteins [SLC26A6 (PAT-1), SLC2A2 (GLUT2)] had a similar expression pattern, increasing from day 2 until day 8; at the protein level, SLC26A3 (DRA) followed a similar expression pattern (Fig. 2A). This expression pattern is consistent with demonstration of proteins involved in nutrient digestion and absorption and electrolyte absorption being clustered in the middle to upper portion of the villus in mouse jejunum (22). The major difference with the results from previous studies in the mouse intestine was the lack of change in expression of adenosine deaminase (ADA) (22). These observations of continual differentiation of villus mRNAs/proteins in domain-specific regions along the villus were further examined by performing similar studies with enteroids grown on Transwell inserts based on days following Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin withdrawal from both the apical and basolateral surfaces. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S2, qRT-PCR results were similar in jejunal enteroid monolayers (from three donors) on Transwell inserts to the results in Jejunal-Intestine-Chip concerning changes in mRNA expression over time. There was additional support for the pattern of mRNA expression with the addition of studies of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and glutathione peroxidase 2 (GPX2), which behaved very similarly to NKCC1 with significant levels at day 1 post plating but with subsequent decreased but present expression. These results were consistent with functional anion secretion being present in the lower villus and also with the demonstrated presence of glutathione transferase activity being clustered in the lower villus of mouse small intestine. In addition, ADA expression only increased at day 7, consistent with expression in the villus tip. This is different from findings in the Intestine-Chip but supportive of findings in mouse intestine, in which ADA and proteins involved in purine metabolism were concentrated near the villus tip (22). Although the results shown here suggest that the human small intestinal villus undergoes continued differentiation after enterocytes emerge into the villus from the crypt, more detailed studies are needed to characterize the extent and consistency of the zonation and its functional consequences in human intestine, particularly with regards to information about protein quantitation and an increase in the number of villus proteins characterized. Moreover, these results support the need to reevaluate the concept that villus tip cells should only be thought of as dying cells. All the above taken together suggest that culture of human enteroids in the Intestine-Chip and in Transwell inserts recapitulates the sequence of differentiation events of the intestinal epithelial cells along the villus.

An area of apparent differences with previous studies using the Intestine-Chip was our inability to observe what has been described as villus-like structures (12, 14, 15, 16, 29, 36, 41). The only time we observed anything similar to what was previously reported as undulated structures was in areas that represented 3-D enteroids that had been incompletely broken up in plating in the Intestine-Chip. Although differences in some of the technical approaches we used compared with the previously reported studies may be the explanation, we suggest that in-depth evaluation of what is being called villus-like structures be carried out to include differential expression of villus proteins and to be sure they do not represent multilayers of cells, that is known to occur with Caco-2 cells.

Of note, however, is that although this model of normal human adult jejunal enteroids in Intestine-Chip represents differentiated villus-like enterocytes, the early differentiation is not compatible with the use of this model in its current design to mimic the crypt compartment of the small intestine. For now, the study of undifferentiated crypt-like jejunal enteroids can only be accomplished by studying 3-D enteroids or enteroids on Transwell inserts in which both apical and basolateral compartments are exposed to Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin and maintained under static conditions (8, 18, 42). We have not determined in this study the consequences on enteroid differentiation by perfusing the upper and lower channels of the Jejunal-Intestine-Chip with the same enteroid expansion media that contains Wnt3A, R-spondin, and Noggin, although this media did not allow maintenance of the HUVECs.

During embryonic and fetal development, mechanical forces are crucial in intestinal loop formation and epithelial architecture organization (28, 30). Currently, a limited number of studies are available with regard to the effects of mechanical forces on intestinal epithelial cells in the postnatal period. In vivo, intestinal epithelium is exposed to a variety of mechanical forces, including shear stress that is associated with luminal and basolateral fluid flow and compression force induced by muscle contraction driven by peristalsis. To date, detailed studies on the effects of these physical forces on intact normal human intestine are lacking. Along these lines, in human ileum, the loss of luminal flow was found to change the expression of various genes involved in proliferation, structural maintenance, digestion, metabolism, and transport (39). In a recent study, Poling et al. (25) showed that spring-induced uniaxial strain enhanced the maturation of iPSC-derived intestinal organoids implanted in vivo. Axial mechanical strain delivered over 14 days by a gradually expanding intraluminal spring caused changes in gene expression pattern from that resembling fetal intestine to one resembling newborn intestine along with increased villus height and crypt depth, tight junction protein expression, and muscle protein expression and contractility, among many other changes.

In the current study, we provide additional proteomic evidence that mechanical forces, particularly fluid shear stress, promote the maturation/differentiation of intestinal epithelial cells. By comparing the proteomic profiles of enteroids from the same samples that either underwent continuous fluid flow while cultured in the Intestine-Chip or studied as monolayers in Transwell inserts under static conditions, we were able to identify biological processes that are changed by fluid shear stress. There was evidence of increased differentiation (proteins with increased expression included sucrase-isomaltase, mucin 3, chromogranin B, and carbonic anhydrase 1, among others), and oxidative phosphorylation, but there was also evidence of induction of proteins associated with increased injury (increased apoptosis) and decreased expression of proteins involved in metabolic process, including lipid biosynthesis, and carbohydrate metabolism. These results suggest that exposure to flow supports functional differentiation and also may provide insights into mechanisms by which epithelial cells adjust to their normal in vivo microenvironment.

Interestingly, the addition of mechanical stretch on top of fluid flow did not seem to cause further differentiation of the enteroids. Changes observed when repetitive stretch was added to fluid flow involved signaling pathways that included increased mTOR, HGF, AMPK, and EGF signaling as well as lipid synthesis and carbohydrate metabolism. It is important to note that the mechanical strain introduced by the Human Emulation System was initially designed to mimic the changes in lung expansion that occur during normal respiration and do not fully mimic the complex contraction patterns that are part of normal peristalsis. These results highlight the need for further studies to increase understanding of the effects of peristaltic contractions on intestinal epithelial function in ex vivo systems.

In conclusion, our study presents a model of Jejunal-Intestine-Chip, in particular of the differentiated intestinal epithelium, and can be used to study jejunum in health and disease. In spite of the early phase of this type of modeling, the current study shows how systematic evaluation of added organ microenvironment-specific factors can contribute to our understanding of tissue differentiation and function; although full understanding will require that multiple factors be studied together and their influence on each other and not only on the epithelial cells be determined.

GRANTS

This study is partly supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DK-26523, R01-DK-116352, R24-DK-64388, U18-TR000552, UH3-TR00003, UO1-DK-10316, and P30-DK-89502, and Emulate, Inc. (Boston, MA).

DISCLOSURES

Magdalena Kasendra and Katia Karalis were employed by Emulate, Inc. during the performance of the study. No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.Y., L.S., H.Y., C.T., and M.D. conceived and designed research; J.Y., L.S., H.Y., and T.B. performed experiments; J.Y., L.S., M.K., H.Y., C.-M.T., C.T., T.B., R.C., and K.K. analyzed data; J.Y., L.S., M.K., C.-M.T., C.T., T.B., R.C., K.K., and M.D. interpreted results of experiments; J.Y., L.S., C.T., and R.C. prepared figures; J.Y. and M.D. drafted manuscript; J.Y., L.S., M.K., H.Y., C.T., K.K., and M.D. edited and revised manuscript; J.Y., L.S., M.K., H.Y., C.-M.T., C.T., R.C., K.K., and M.D. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank George McNamara (Johns Hopkins University) and Jason Brenner (Olympus) for assistance in confocal imaging, Dr. Alan Verkman (University of California, San Francisco) for providing DRAinh-A250, and Ardelyx, Inc. (Fremont, CA) for providing Tenapanor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alimperti S, Mirabella T, Bajaj V, Polacheck W, Pirone DM, Duffield J, Eyckmans J, Assoian RK, Chen CS. Three-dimensional biomimetic vascular model reveals a RhoA, Rac1, and N-cadherin balance in mural cell-endothelial cell-regulated barrier function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114: 8758–8763, 2017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618333114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avula LR, Chen T, Kovbasnjuk O, Donowitz M. Both NHERF3 and NHERF2 are necessary for multiple aspects of acute regulation of NHE3 by elevated Ca2+, cGMP, and lysophosphatidic acid. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 314: G81–G90, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00140.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Rosenbaum DP. Tenapanor treatment of patients withconstipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety trial. Am J Gastroenterol 112: 763–774, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins NT, Cummins PM, Colgan OC, Ferguson G, Birney YA, Murphy RP, Meade G, Cahill PA. Cyclic strain-mediated regulation of vascular endothelial occludin and ZO-1: influence on intercellular tight junction assembly and function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 62–68, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000194097.92824.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Lau W, Barker N, Low TY, Koo BK, Li VS, Teunissen H, Kujala P, Haegebarth A, Peters PJ, van de Wetering M, Stange DE, van Es JE, Guardavaccaro D, Schasfoort RB, Mohri Y, Nishimori K, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Clevers H. LGR5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 476: 293–297, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duan T, Cil O, Tse CM, Sarker R, Lin R, Donowitz M, Verkman AS. Inhibition of CFTR-mediated intestinal chloride secretion as potential therapy for bile acid diarrhea. FASEB J 33: 10924–10934, 2019. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901166R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field M. Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea. J Clin Invest 111: 931–943, 2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI18326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foulke-Abel J, In J, Yin J, Zachos NC, Kovbasnjuk O, Estes MK, de Jonge H, Donowitz M. Human enteroids as a model of upper small intestinal ion transport physiology and pathophysiology. Gastroenterology 150: 638–649.e8, 2016. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregersen H, Kassab GS, Fung YC. The zero-stress state of the gastrointestinal tract: biomechanical and functional implications. Dig Dis Sci 45: 2271–2281, 2000. doi: 10.1023/a:1005649520386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haggie PM, Cil O, Lee S, Tan JA, Rivera AA, Phuan PW, Verkman AS. SLC26A3 inhibitor identified in small molecule screen blocks colonic fluid absorption and reduces constipation. JCI Insight 3: e121370, 2018. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.In J, Foulke-Abel J, Zachos NC, Hansen AM, Kaper JB, Bernstein HD, Halushka M, Blutt S, Estes MK, Donowitz M, Kovbasnjuk O. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli reduce mucus and intermicrovillar bridges in human stem cell-derived colonoids. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2: 48–62.e3, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, Gazzaniga FS, Calamari EL, Camacho DM, Fadel CW, Bein A, Swenor B, Nestor B, Cronce MJ, Tovaglieri A, Levy O, Gregory KE, Breault DT, Cabral JMS, Kasper DL, Novak R, Ingber DE. A complex human gut microbiome cultured in an anaerobic intestine-on-a-chip. Nat Biomed Eng 3: 520–531, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0397-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janecke AR, Heinz-Erian P, Yin J, Petersen BS, Franke A, Lechner S, Fuchs I, Melancon S, Uhlig HH, Travis S, Marinier E, Perisic V, Ristic N, Gerner P, Booth IW, Wedenoja S, Baumgartner N, Vodopiutz J, Frechette-Duval MC, De Lafollie J, Persad R, Warner N, Tse CM, Sud K, Zachos NC, Sarker R, Zhu X, Muise AM, Zimmer KP, Witt H, Zoller H, Donowitz M, Muller T. Reduced sodium/proton exchanger NHE3 activity causes congenital sodium diarrhea. Hum Mol Genet 24: 6614–6623, 2015. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasendra M, Luc R, Yin J, Manatakis DV, Kulkarni G, Lucchesi C, Sliz J, Apostolou A, Sunuwar L, Obrigewitch J, Jang KJ, Hamilton GA, Donowitz M, Karalis K. Duodenum Intestine-Chip for preclinical drug assessment in a human relevant model. Elife 9: e50135, 2020. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasendra M, Tovaglieri A, Sontheimer-Phelps A, Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, Bein A, Chalkiadaki A, Scholl W, Zhang C, Rickner H, Richmond CA, Li H, Breault DT, Ingber DE. Development of a primary human Small Intestine-on-a-Chip using biopsy-derived organoids. Sci Rep 8: 2871, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HJ, Huh D, Hamilton G, Ingber DE. Human gut-on-a-chip inhabited by microbial flora that experiences intestinal peristalsis-like motions and flow. Lab Chip 12: 2165–2174, 2012. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40074j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Li H, Collins JJ, Ingber DE. Contributions of microbiome and mechanical deformation to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and inflammation in a human gut-on-a-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E7–E15, 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522193112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar P, Kuhlmann FM, Chakraborty S, Bourgeois AL, Foulke-Abel J, Tumala B, Vickers TJ, Sack DA, DeNearing B, Harro CD, Wright WS, Gildersleeve JC, Ciorba MA, Santhanam S, Porter CK, Gutierrez RL, Prouty MG, Riddle MS, Polino A, Sheikh A, Donowitz M, Fleckenstein JM. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-blood group A interactions intensify diarrheal severity. J Clin Invest 128: 3298–3311, 2018. doi: 10.1172/JCI97659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Low LA, Tagle DA. Organs-on-chips: progress, challenges, and future directions. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 242: 1573–1578, 2017. doi: 10.1177/1535370217700523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mäkelä S, Kere J, Holmberg C, Höglund P. SLC26A3 mutations in congenital chloride diarrhea. Hum Mutat 20: 425–438, 2002. doi: 10.1002/humu.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchelletta RR, Gareau MG, McCole DF, Okamoto S, Roel E, Klinkenberg R, Guiney DG, Fierer J, Barrett KE. Altered expression and localization of ion transporters contribute to diarrhea in mice with Salmonella-induced enteritis. Gastroenterology 145: 1358–1368.e1-4, 2013. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moor AE, Harnik Y, Ben-Moshe S, Massasa EE, Rozenberg M, Eilam R, Bahar Halpern K, Itzkovitz S. Spatial reconstruction of single enterocytes uncovers broad zonation along the intestinal villus axis. Cell 175: 1156–1167.e15, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Njah K, Chakraborty S, Qiu B, Arumugam S, Raju A, Pobbati AV, Lakshmanan M, Tergaonkar V, Thibault G, Wang X, Hong W. A role of agrin in maintaining the stability of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 during tumor angiogenesis. Cell Rep 28: 949–965.e7, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noel G, Baetz NW, Staab JF, Donowitz M, Kovbasnjuk O, Pasetti MF, Zachos NC. A primary human macrophage-enteroid co-culture model to investigate mucosal gut physiology and host-pathogen interactions. Sci Rep 7: 45270, 2017. [Erratum in Sci Rep 7: 46790, 2017]. doi: 10.1038/srep45270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poling HM, Wu D, Brown N, Baker M, Hausfeld TA, Huynh N, Chaffron S, Dunn JCY, Hogan SP, Wells JM, Helmrath MA, Mahe MM. Mechanically induced development and maturation of human intestinal organoids in vivo. Nat Biomed Eng 2: 429–442, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0243-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raasch M, Rennert K, Jahn T, Peters S, Henkel T, Huber O, Schulz I, Becker H, Lorkowski S, Funke H, Mosig A. Microfluidically supported biochip design for culture of endothelial cell layers with improved perfusion conditions. Biofabrication 7: 015013, 2015. doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/7/1/015013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rashidi H, Alhaque S, Szkolnicka D, Flint O, Hay DC. Fluid shear stress modulation of hepatocyte-like cell function. Arch Toxicol 90: 1757–1761, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1689-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savin T, Kurpios NA, Shyer AE, Florescu P, Liang H, Mahadevan L, Tabin CJ. On the growth and form of the gut. Nature 476: 57–62, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin W, Hinojosa CD, Ingber DE, Kim HJ. Human intestinal morphogenesis controlled by transepithelial morphogen gradient and flow-dependent physical cues in a microengineered gut-on-a-chip. iScience 15: 391–406, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shyer AE, Tallinen T, Nerurkar NL, Wei Z, Gil ES, Kaplan DL, Tabin CJ, Mahadevan L. Villification: how the gut gets its villi. Science 342: 212–218, 2013. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6154.21-b, . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spence JR, Mayhew CN, Rankin SA, Kuhar MF, Vallance JE, Tolle K, Hoskins EE, Kalinichenko VV, Wells SI, Zorn AM, Shroyer NF, Wells JM. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature 470: 105–109, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subramanya SB, Rajendran VM, Srinivasan P, Nanda Kumar NS, Ramakrishna BS, Binder HJ. Differential regulation of cholera toxin-inhibited Na-H exchange isoforms by butyrate in rat ileum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293: G857–G863, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00462.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sunuwar L, Yin J, Kasendra M, Karalis K, Kaper J, Fleckenstein J, Donowitz M. Mechanical stimuli affect Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin-cyclic GMP signaling in a human enteroid Intestine-Chip model. Infect Immun 88: e00866-19, 2019. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00866-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terry BS, Lyle AB, Schoen JA, Rentschler ME. Preliminary mechanical characterization of the small bowel for in vivo robotic mobility. J Biomech Eng 133: 091010, 2011. doi: 10.1115/1.4005168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thiagarajah JR, Kamin DS, Acra S, Goldsmith JD, Roland JT, Lencer WI, Muise AM, Goldenring JR, Avitzur Y, Martín MG; PediCODE Consortium. Advances in evaluation of chronic diarrhea in infants. Gastroenterology 154: 2045–2059.e6, 2018. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tovaglieri A, Sontheimer-Phelps A, Geirnaert A, Prantil-Baun R, Camacho DM, Chou DB, Jalili-Firoozinezhad S, de Wouters T, Kasendra M, Super M, Cartwright MJ, Richmond CA, Breault DT, Lacroix C, Ingber DE. Species-specific enhancement of enterohemorrhagic E. coli pathogenesis mediated by microbiome metabolites. Microbiome 7: 43, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0650-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tse CM, Yin J, Singh V, Sarker R, Lin R, Verkman AS, Turner JR, Donowitz M. cAMP stimulates SLC26A3 activity in human colon by a CFTR-dependent mechanism that does not require CFTR activity. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 7: 641–653, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vernetti L, Gough A, Baetz N, Blutt S, Broughman JR, Brown JA, Foulke-Abel J, Hasan N, In J, Kelly E, Kovbasnjuk O, Repper J, Senutovitch N, Stabb J, Yeung C, Zachos NC, Donowitz M, Estes M, Himmelfarb J, Truskey G, Wikswo JP, Taylor DL. Functional coupling of human microphysiology systems: intestine, liver, kidney proximal tubule, blood-brain barrier and skeletal muscle. Sci Rep 7: 42296, 2017. doi: 10.1038/srep42296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wieck MM, Schlieve CR, Thornton ME, Fowler KL, Isani M, Grant CN, Hilton AE, Hou X, Grubbs BH, Frey MR, Grikscheit TC. Prolonged absence of mechanoluminal stimulation in human intestine alters the transcriptome and intestinal stem cell niche. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 3: 367–388.e1, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wikswo JP. The relevance and potential roles of microphysiological systems in biology and medicine. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 239: 1061–1072, 2014. doi: 10.1177/1535370214542068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Workman MJ, Gleeson JP, Troisi EJ, Estrada HQ, Kerns SJ, Hinojosa CD, Hamilton GA, Targan SR, Svendsen CN, Barrett RJ. Enhanced utilization of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived human intestinal organoids using microengineered chips. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 5: 669–677.e2, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin J, Tse CM, Avula LR, Singh V, Foulke-Abel J, de Jonge HR, Donowitz M. Molecular basis and differentiation-associated alterations of anion secretion in human duodenal enteroid monolayers. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 5: 591–609, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu H, Hasan NM, In JG, Estes MK, Kovbasnjuk O, Zachos NC, Donowitz M. The contributions of human mini-intestines to the study of intestinal physiology and pathophysiology. Annu Rev Physiol 79: 291–312, 2017. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zachos NC, Kovbasnjuk O, Foulke-Abel J, In J, Blutt SE, de Jonge HR, Estes MK, Donowitz M. Human enteroids/colonoids and intestinal organoids functionally recapitulate normal intestinal physiology and pathophysiology. J Biol Chem 291: 3759–3766, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.635995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]