Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with high heterogeneity is one of the most frequent malignant tumors throughout the world. However, there is no research to establish a ferroptosis-related lncRNAs (FRlncRNAs) signature for the patients with HCC. Therefore, this study was designed to establish a novel FRlncRNAs signature to predict the survival of patients with HCC.

Method

The expression profiles of lncRNAs were acquired from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. FRlncRNAs co-expressed with ferroptosis-related genes were utilized to establish a signature. Cox regression was used to construct a novel three FRlncRNAs signature in the TCGA cohort, which was verified in the GEO validation cohort.

Results

Three differently expressed FRlncRNAs significantly associated with prognosis of HCC were identified, which composed a novel FRlncRNAs signature. According to the FRlncRNAs signature, the patients with HCC could be divided into low- and high-risk groups. Patients with HCC in the high-risk group displayed shorter overall survival (OS) contrasted with those in the low-risk group (P < 0.001 in TCGA cohort and P = 0.045 in GEO cohort). This signature could serve as a significantly independent predictor in Cox regression (multivariate HR > 1, P < 0.001), which was verified to a certain extent in the GEO cohort (univariate HR > 1, P < 0.05). Meanwhile, it was also a useful tool in predicting survival among each stratum of gender, age, grade, stage, and etiology,etc. This signature was connected with immune cell infiltration (i.e., Macrophage, Myeloid dendritic cell, and Neutrophil cell, etc.) and immune checkpoint blockade targets (PD-1, CTLA-4, and TIM-3).

Conclusion

The three FRlncRNAs might be potential therapeutic targets for patients, and their signature could be utilized for prognostic prediction in HCC.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Ferroptosis, Immunotherapy, lncRNA, Gene signature

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is the second frequent cause of death in human cancers throughout the world, is one of the most common malignant tumors (Llovet et al., 2016). It was estimated that approximately 841,000 new cases of HCC are diagnosed annually and approximately 781,631 patients would die of HCC in 2018 (Bray et al., 2018). For early-stage patients, radiofrequency local ablation, partial hepatectomy and liver transplantation are the major therapies and about 70% of patients will relapse within five years after operation (European Association for the Study of the Liver, 2018). Immune checkpoint inhibitors have been proven to be effective strategies for the treatment of advanced HCC, but their effectiveness still need to be further improved (Yang et al., 2019). Despite the advances in early detection, and drug development, the clinical outcomes of advanced cases remain unsatisfactory. The 5-year survival rate of local HCC is 30.5%, and that of distant metastasis was less than 5% (Oweira et al., 2017). To improve clinical outcomes and reduce the burden of cases, it is urgent to identify novel effective molecular markers and ameliorate prediction of HCC prognosis.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent modality of regulated cell death driven by the malignant accumulation of lipid peroxidation (Dixon et al., 2012; Stockwell et al., 2017). Recently, the induction of ferroptosis has been listed as a promising therapeutic strategy, especially suitable for malignant tumors that respond to resistance in traditional treatments (Hassannia, Vandenabeele & Vanden Berghe, 2019; Liang et al., 2019). A large number of experimental studies had indicated that ferroptosis-related genes played a vital role in HCC (Jennis et al., 2016; Louandre et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016a; Sun et al., 2016b; Yuan et al., 2016).

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) with a minimum length of about 200 nucleotides are autonomous transcriptional RNA which does not encode proteins (Cech & Steitz, 2014). LncRNAs have been proven to be abnormally expressed in multiple cancers, and aberrant lncRNAs have been reported to serve as prognostic indicators in various cancers including HCC (Ai et al., 2020; He et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2020; Zhao, Liu & Yu, 2017). One recent study revealed that ferroptosis-related lncRNAs signature was associated with the prognosis of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (Tang et al., 2021). However, there is little research on ferroptosis-related lncRNAs correlated with HCC patient prognosis. Therefore, this study aims to establish a novel ferroptosis-related lncRNAs (FRlncRNAs) signature in predicting the prognosis of patients with HCC, hoping to improve current diagnosis, treatment, follow-up and prevention strategies of HCC.

Materials and Methods

Data source and clinical information

The RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data together with relevant clinical data were accessed from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). An overview of the clinical information and source file of the patients with HCC can be found in Table 1 and Table S1. Notably, those patients with follow-up time greater than one month were used for the study. Totally, 374 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients were available for further analysis. The GSE14520 dataset was acquired from GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), containing 488 patients with HCC. A total of 259 ferroptosis-related genes (Marker: 111; Driver: 108; Suppressor: 69) were identified from FerrDb Database (Zhou & Bao, 2020) (FerrDb, http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb/; Table S2). The TCGA dataset was utilized for training cohort while the GSE14520 dataset was validation cohort.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the patients with HCC from the TCGA cohort in this study.

| Variables | Number of patients | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <65 | 224 | 59.42 |

| ≥65 | 152 | 40.32 |

| NA | 1 | 0.27 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 255 | 67.64 |

| Female | 122 | 32.36 |

| Grade | ||

| G1 | 55 | 14.59 |

| G2 | 180 | 47.75 |

| G3 | 124 | 32.89 |

| G4 | 13 | 3.45 |

| NA | 5 | 1.33 |

| Stage | ||

| stage I | 175 | 46.42 |

| stage II | 88 | 23.34 |

| stage III | 86 | 22.81 |

| stage IV | 6 | 1.59 |

| NA | 22 | 5.84 |

| Etiology | ||

| Alcohol Liver Disease | 118 | 31.30 |

| NAFLD | 12 | 3.18 |

| HBV/HCV | 118 | 31.30 |

| Hemochromatosis | 5 | 1.33 |

| NA | 124 | 32.89 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| YES | 8 | 2.12 |

| NO | 338 | 89.66 |

| NA | 31 | 8.22 |

| Family history | ||

| YES | 114 | 30.24 |

| NO | 212 | 56.23 |

| NA | 51 | 13.53 |

Notes.

- NAFLD

- nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- HBV

- hepatitis B virus

- HCV

- hepatitis C virus

LncRNAs and ferroptosis-related genes data processing

The “limma” package was employed to select differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes, which were visualized through the volcano and heatmaps. Then, we carried out functional enrichment analysis (Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)) to determine the major biological attributes. The “GOplot” package was utilized to visualize enrichment terms.

To calculate the correlation between candidate ferroptosis-related lncRNAs (FRlncRNAs) and differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes utilizing Pearson correlation. The coefficient P < 0.001 and —R2—> 0.3 were regarded to be FRlncRNAs. Finally, Cytoscape software was utilized to draw co-expression network of prognostic FRlncRNAs and ferroptosis-related genes.

Construction of prognostic FRlncRNAs signature

First, the FRlncRNAs associated with prognosis were assessed using univariate Cox regression in training cohort. Then, FRlncRNAs with P ≤ 0.05 were included into multivariate Cox regression for the construction of FRlncRNAs signature. The formula utilized was as follows: risk score of FRlncRNAs signature = . To stratify patients into low- or high-risk groups, the best cut-off of the FRlncRNAs signature was identified applying receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve at 1 year for overall survival (OS). Survival analysis between the two risk groups were assessed by Kaplan–Meier (KM) and compared using log-rank statistical methods.

Nomogram was utilized to predict 1, 3 years, and 5 years survival for the patients with HCC. ROC curves and Calibration curves were utilized to explore the accuracy of model based on training cohort. Then, we adjusted other clinical features in independent prognostic analysis in order to confirm whether the FRlncRNAs signature was an independent indicator to predict the prognosis of patient with HCC.

Validation of the FRlncRNAs signature

The GEO cohort was enrolled to verify the robustness of model established from training cohort. The FRlncRNAs signature was calculated based on validation cohort. Then, survival analysis and Cox regression were utilized to evaluate whether the FRlncRNAs signature was significantly connected with OS in validation cohort. The ROC curves were established to assess whether the novel model could accurately predict patient survival.

Gene set enrichment analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA, http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp) was utilized to investigate functional phenotypes differences between the two risk groups (high- and low-risk groups). In this research, we carried out functional enrichment of FRlncRNAs signature, and visualized the pathway closely related to immune and tumorigenesis development. The reference gene sets contained “c7.all.v7.2.symbols.gmt [Immunologic signatures] and h.all.v7.2.symbols.gmt [cancer hallmarks]”.

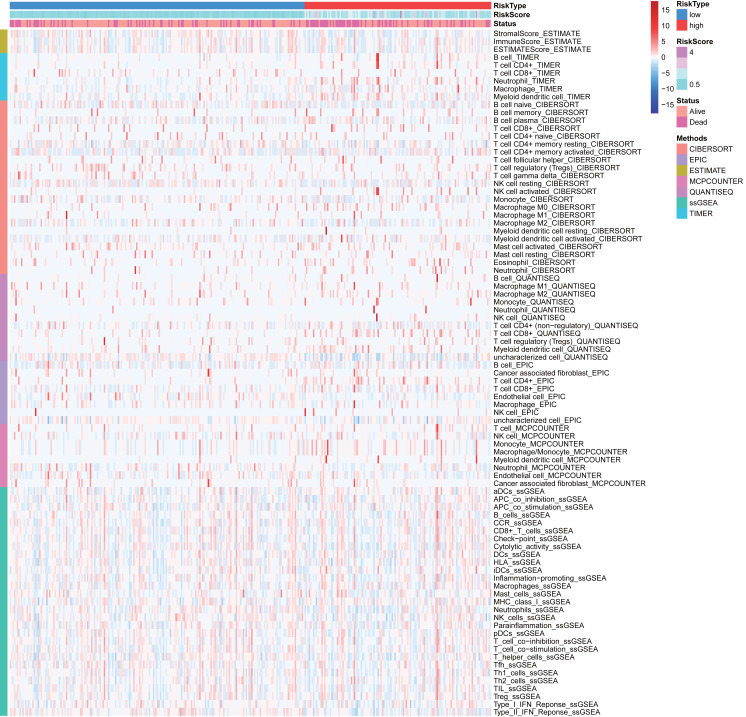

Immune correlation analysis

The CIBERSORT (Charoentong et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2015), EPIC (Racle et al., 2017), ESTIMATE (Yoshihara et al., 2013), MCP counter (Shi et al., 2020), QUANTISEQ (Finotello et al., 2019), TIMER (Li et al., 2017), and single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) (Yi et al., 2020) algorithms were used to infer the relative content of tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs) between two risk group based on FRlncRNAs signature. The heatmap was utilized to visualize the differences of TIICs abundance under different algorithms. Besides, the correlation analysis between the abundance of TIICs and FRlncRNAs signature was utilized to reveal the potential role of FRlncRNAs signature on the immunologic features based on TIMER results.

The expression of immune checkpoint gene might be related to treatment responses of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (Goodman, Patel & Kurzrock, 2017). Thus, we investigated six ICIs: programmed death 1 (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD-L1), ligand 2 (PD-L2), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), and T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein-3 (TIM-3) in HCC (Kim et al., 2017; Nishino et al., 2017; Zhai et al., 2018). We analyzed the Spearman correlation between the ICIs and the signature, which aimed to investigate the potential role of FRlncRNAs signature in immune checkpoint blockade therapy.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were conducted using R language (version 4.0). KM analysis with log-rank test from “survival” package was applied to compare the survival difference among two risk groups. In order to evaluate the prognostic value of the novel FRlncRNAs signature, univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted through Cox proportional hazards regression model. Stratification analysis was implemented based on age (≥65 and <65 years), gender (male and female), stage (stage 1–2 and stage 3–4), grade (grade 1–2 and grade 3–4), etiology (Alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; HBV/HCV and non-HBV/HCV), Radiotherapy (receive radiotherapy and no receive radiotherapy), and family history (have family history of cancer and no family history). GSEA was applied to differentiate between two risk groups of functional annotations. Statistical tests were bilateral, with P value ≤ 0.05 indicated statistically significant differences.

Results

Differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes

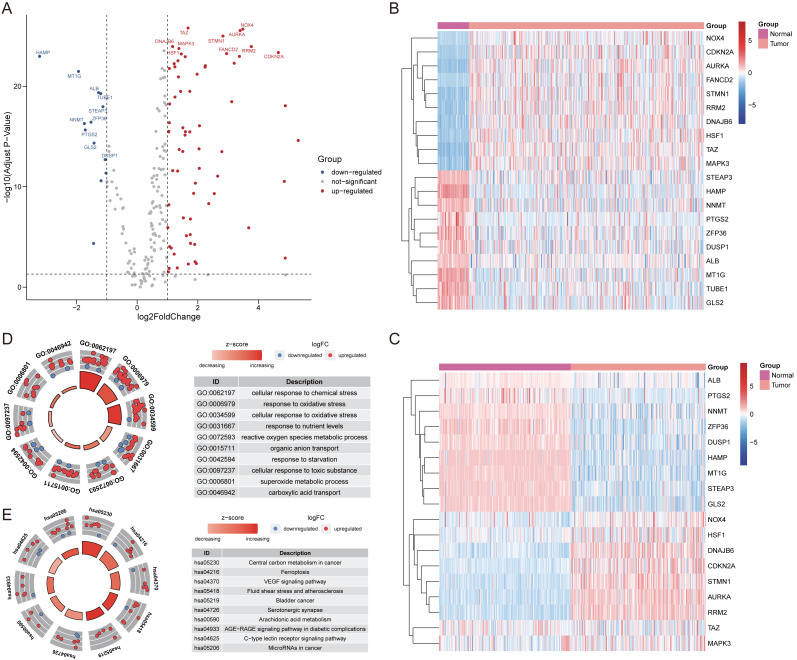

After extracting the expression values of 259 ferroptosis-related genes in the patient with HCC, 69 up-regulated genes and 13 down-regulated genes were authenticated (FDR <0.05, log2FC >1; Table S3). The differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes were visualized by volcano and heatmaps (Figs. 1A–1C). The GO enrichment revealed that these differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes mainly participated in cellular response to chemical stress, response to oxidative stress, and carboxylic acid transport among others (Fig. 1D). The major KEGG pathways included Ferroptosis, VEGF signaling pathway, Arachidonic acid metabolism and some cancer-related signaling pathways (Fig. 1E; Table S4).

Figure 1. The differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes.

(A) The Volcano plot of the differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes. The red dots indicated up-regulated and blue for down-regulated. The top 20 gene symbols with high variation were displayed in the plot. (B) The heatmap of 20 ferroptosis-related genes with high variation in training cohort. (C) The heatmap of 20 ferroptosis-related genes with high variation (except for TUBE1, and FANCD2) between tumor and normal samples in validation cohort. (D) The GO circle plot of functional enrichment. The red dots indicated up-regulation, while the blue indicated down-regulation. (E) The KEGG circle plot of enrichment analysis. The Z-score was directly proportional to the level of enrichment.

Identification of prognostic FRlncRNAs and an FRlncRNAs signature

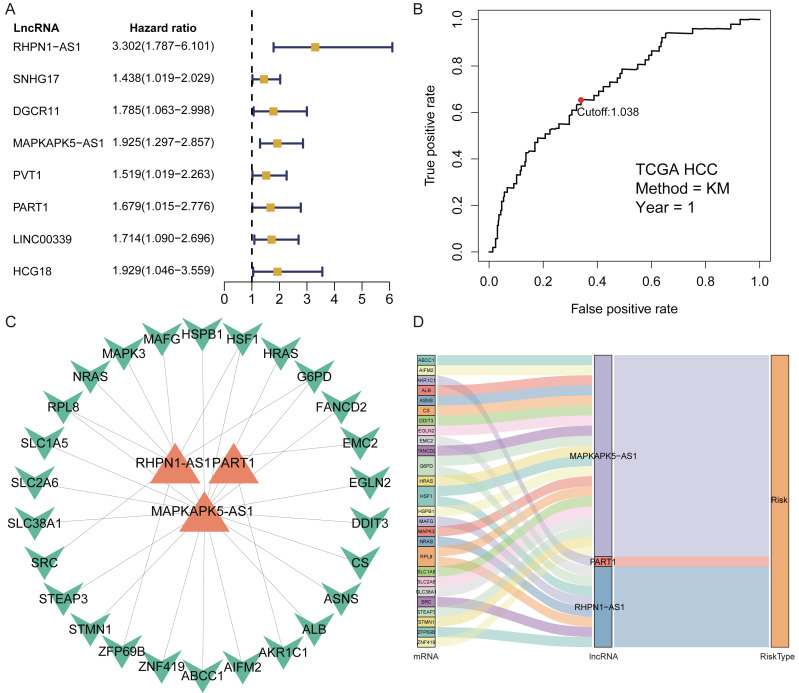

A total of 1,184 FRlncRNAs were identified in the training cohort through the correlation analysis between differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes and lncRNAs (—R2—>0.3 and P < 0.001; Table S5). Among them, 32 FRlncRNAs co-existed in training cohort and validation cohort were used for subsequent model construction and validation. The batch effects from different cohorts were corrected by combat function in “sva” package. Cox regression were applied to screen prognostic FRlncRNAs. In accordance with univariate cox results, eight FRlncRNAs had potential prognostic value for the patients with HCC (P < 0.05, Fig. 2A, Table S6). As shown in Table S6, eight FRlncRNAs (RHPN1 −AS1, SNHG17, DGCR11, MAPKAPK5 −AS1, PVT1, PART1, LINC00339 and HCG18) were discovered to be harmful prognostic indicators.

Figure 2. Identification of prognostic Ferroptosis-related lncRNAs (FRlncRNAs).

(A) Forest plots revealed prognosis-related FRlncRNAs based on the results of univariate Cox regression. (B) ROC curve for FRlncRNAs signature at 1 year in training cohort. The cut-off score was 1.038 and it was utilized to classify patients into high- or low-risk groups. (C) The relational network between signature and corresponding co-expression ferroptosis-related genes. (D) Sankey diagram indicated that the association between prognostic FRlncRNAs, ferroptosis-related genes, and risk type.

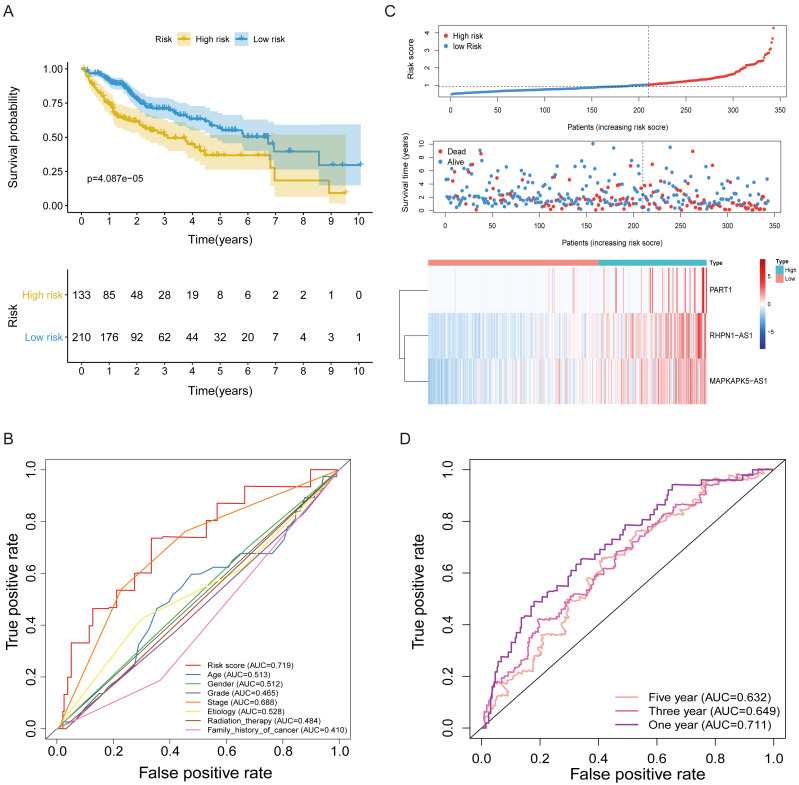

Subsequently, multivariate Cox regression found that three FRlncRNAs were associated with prognostic for the patients with HCC (Table S6). The three FRlncRNAs were utilized to establish a FRlncRNAs signature. The risk score was estimated using the following formula: risk score of FRlncRNAs signature = (0.89773*RHPN1-AS1) + (0.48558* MAPKAPK5-AS1) + (0.55674*PART1). The optimal cut-off point of risk score was considered to be 1.038 through ROC curve. Based on this cut-off point, the patients with HCC were classified into high- or low-risk group (Fig. 2B). The relationship between the three prognostic FRlncRNAs and co-expressed mRNA was shown in Fig. 2C and Fig. 2D. The risk score was significantly relevant to OS of patients, where OS in high-risk group possessed shorter than those in low-risk group (P < 0.001, Fig. 3A). Concurrently, the AUC of the FRlncRNAs signature was 0.719, showing great performance in contrast to other traditional clinical pathological features in predicting the prognosis of patients with HCC (Fig. 3B). The survival status plot showed that risk score of patients was inversely proportional to their survival rate. Besides, the risk heatmap demonstrated that the expression of three FRlncRNAs had positive correlation with the risk levels (Fig. 3C). The areas under the ROC (AUC) values corresponding to 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.711, 0.649 and 0.632, respectively (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. The FRlncRNAs signature based on training cohort.

(A) Kaplan–Meier (KM) curve for overall survival (OS) of patients with HCC in high- and low-risk group in training cohort. (B) The AUC values of the risk score and additional clinical characteristics. (C) Risk survival status plot in patients with HCC. (D) ROC curves at 1, 3, 5-year were applied to verify prognostic performance of FRlncRNAs signature established by training cohort.

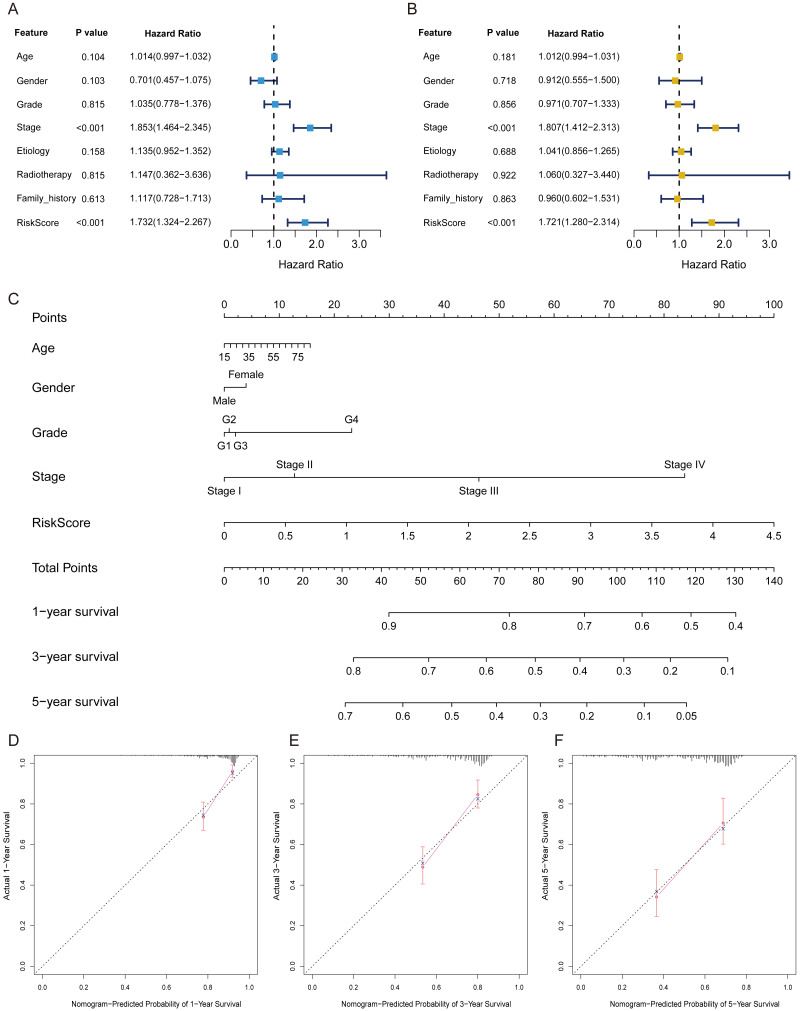

The FRlncRNAs signature was an independent prognostic indicator

Univariate independent prognostic analysis revealed that risk score was a prognostic factor and significantly associated with worse survival (HR = 1.732, 95% CI [1.324–2.267]; P < 0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 4A). Moreover, after adjusting other available clinical parameters such as age, gender, stage, grade, etiology, radiotherapy, and family history, our signature still maintained an independent prognostic factor in multivariate independent analysis (HR = 1.721, 95% CI [1.280–2.314]; P < 0.001) (Table 2, Fig. 4B). As indicated in the nomogram, three-FRlncRNA-based signature was the largest contribution to OS of each period in HCC (Fig. 4C). The calibration displayed that the FRlncRNAs signature possessed high accuracy (Figs. 4D–4F).

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate independent prognostic analysis of FRlncRNAs signature in predicting patient survival.

| Univariate Cox model | Multivariate Cox model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR(95% Cl) | p value | HR(95% Cl) | p value |

| Training cohort | ||||

| Age | 1.014(0.997–1.032) | 0.104 | 1.012(0.994–1.031) | 0.181 |

| Gender | 0.701(0.457–1.075) | 0.103 | 0.912(0.555–1.500) | 0.718 |

| Grade | 1.035(0.778–1.376) | 0.815 | 0.971(0.707–1.333) | 0.856 |

| Stage | 1.853(1.464–2.345) | <0.001 | 1.807(1.412–2.313) | <0.001 |

| Etiology | 1.135(0.952–1.352) | 0.158 | 1.041(0.856–1.265) | 0.688 |

| Radiotherapy | 1.147(0.362–3.636) | 0.815 | 1.060(0.327–3.440) | 0.922 |

| Family history | 1.117(0.728–1.713) | 0.613 | 0.960(0.602–1.531) | 0.863 |

| Risk Score | 1.732(1.324–2.267) | <0.001 | 1.721(1.280–2.314) | <0.001 |

| Validation cohort | ||||

| Gender | 1.689(0.816–3.497) | 0.158 | 1.381(0.659–2.891) | 0.392 |

| Age | 0.991(0.972–1.010) | 0.343 | 1.000(0.980–1.021) | 0.964 |

| TNM stage | 2.340(1.771–3.091) | <0.001 | 1.763(1.268–2.451) | <0.001 |

| CLIP stage | 1.921(1.554–2.375) | <0.001 | 1.493(1.155–1.930) | 0.002 |

| Risk Score | 1.410(1.054–1.887) | 0.021 | 1.049(0.764–1.439) | 0.769 |

Figure 4. The FRlncRNAs signature was an independent prognostic indicator and possessed potential clinical value in the training cohort.

Univariate (A) and multivariate (B) Cox regression analysis of the FRlncRNAs signature in predicting patient survival. (C) A nomogram among clinical features (including the risk score) and OS of patients. (D–F) Calibration for assessing the consistence between the predicted and the actual OS at 1, 3, 5 years.

Stratification analyses

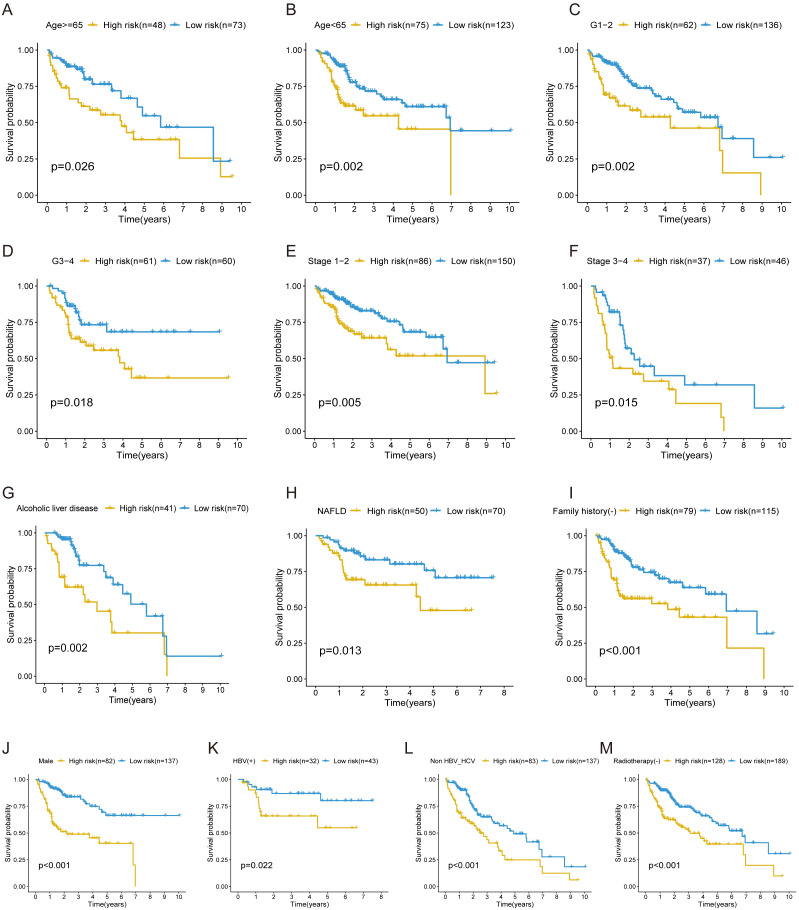

In the training cohort, stratification analysis was conducted based on the clinicopathological features of HCC (e.g., gender, age, grade, stage, etiology, radiotherapy, and family history). As a result, the FRlncRNAs signature was still closely associated with worse survival in male, older (≥65 years) or younger (<65 years), advanced grade (Grade 3–4) or early grade (Grade 1–2) and advanced stage (Stage 3–4) or early stage (Stage 1–2) patients (all P < 0.05; Figs. 5A–5F), which indicated that FRlncRNAs signature based on risk grouping could serve as a useful tool for predicting HCC survival among each stratum of gender, age, grade, and stage. Meanwhile, this signature can also be utilized as a potential prognostic tool for HCC patients with alcoholic or non-alcoholic liver disease, no family history of cancer, HBV-positive, HBV- and HCV- negative, and no radiotherapy (Figs. 5G–5M).

Figure 5. The survival curves of the FRlncRNAs signature stratified by age, grade, stage, gender, etiology, radiotherapy, and family history.

(A) ≥ 65 years, (B) <65 years, (C) grade 1–2, (D) grade 3–4, (E) stage 1–2, (F) stage 3–4, (G) Alcoholic liver disease, (H) NAFLD, (I) no family history, (J) male, (K) HBV positive, (L) HBV and HCV negative, (M) no radiotherapy patients.

Validation of the FRlncRNAs signature

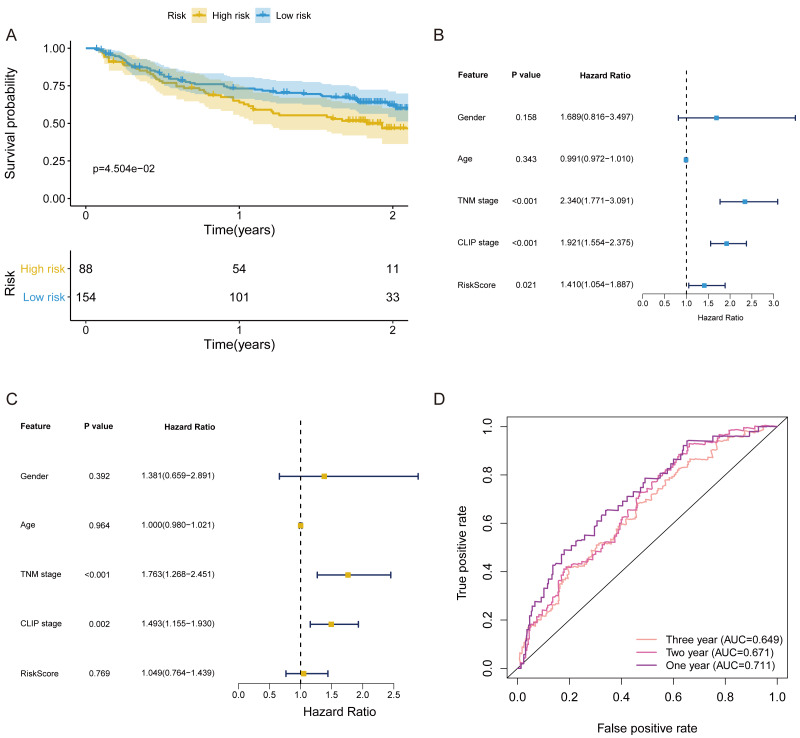

In validation cohort, the risk score of FRlncRNAs signature was estimated refer to the previous formula. The cut-off point of the risk score of the validation cohort was consistent with that of the training cohort (Cutoff = 1.038). The signature was also statistically associated with OS of patients with HCC (P = 4.504e−02, Fig. 6A). Univariate independent prognostic analysis revealed that FRlncRNAs signature acted as an independent prognostic factor (HR of risk score = 1.410, 95% CI [1.054–1.887], P < 0.05, Table 2, Fig. 6B). Notably, after controlling gender, age, TNM stage, and CLIP stage, FRlncRNAs signature was no longer a prognostic factor in multivariate analysis (HR = 1.049, 95% CI [0.764–1.439], P > 0.05), which indicated that more independent cohorts needed to be included for validation (Table 2, Fig. 6C). The AUC values were more than 0.65 at 1 year, 2 years and 3 years, which showed that the FRlncRNAs signature established from training cohort had powerful accuracy and robustness (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. The verification of prognostic FRlncRNAs signature in validation cohort.

(A) The KM curves of validation cohort revealed that the high-risk group had statistical differences on OS period compared with the low-risk group (P < 0.05). Univariate (B) and multivariate (C) COX regression for the FRlncRNAs signature established by training cohort. (D) AUC of ROC curves validated the predicted performance of signature in the validation cohort.

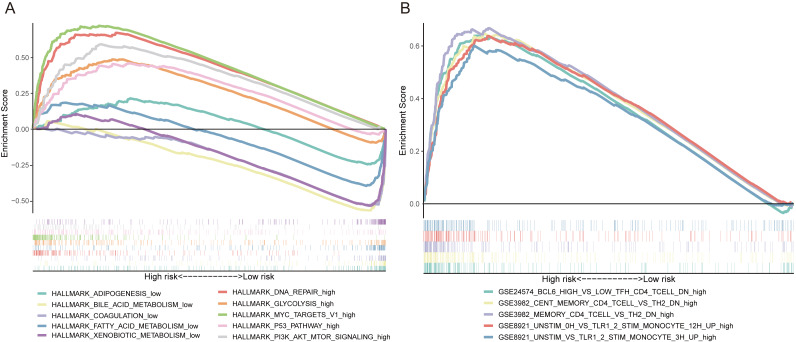

The FRlncRNAs signature mediated DNA repair, glycolysis, MYC targets, P53 pathway and PI3K AKT mTOR signaling

GSEA was utilized to explore the potential biological mechanisms of the FRlncRNAs signature involved in HCC progression. The results of cancer hallmarks indicated that DNA repair, glycolysis, MYC targets, P53 pathway and PI3K AKT mTOR signaling were activated by the high-risk group of the FRlncRNAs signature. While adipogenesis, bile acid metabolism, coagulation, fatty acid metabolism and xenobiotic metabolism were activated by the low-risk group (Fig. 7A). Moreover, the signature also regulated many immunologic features within immune system, such as BCL6 high versus low TFH CD4 T cell down, cent memory CD4 T cell versus TH2 down etc., which indicated that the FRlncRNAs signature was implicated in immunity-related regulation (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Some cancer-related hallmarks and immunologic features regulated through the FRlncRNAs signature.

(A) Cancer hallmarks. (B) Immunologic signatures.

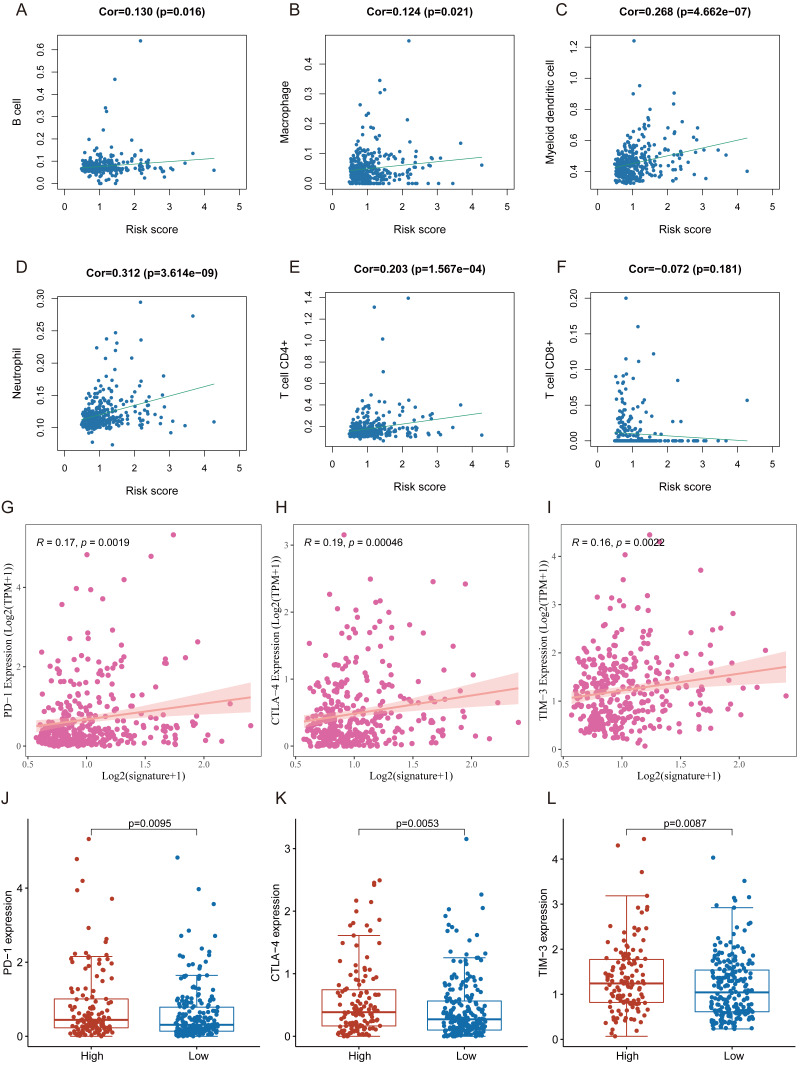

Correlation of FRlncRNAs signature with TICIs and immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) molecule

Many immunologic features were found to be regulated by FRlncRNAs signature according to the above results. Therefore, the signature was further explored whether it was associated with TIICs based on TIMER results. The results indicated that this signature was most significantly positive correlation with immune infiltration of Neutrophil cells (COR = 0.312, P < 0.001), Myeloid cells (COR = 0.268, P < 0.001), CD4+ T cells (COR = 0.203, P < 0.001), B cells (COR = 0.130, P = 0.016), and Macrophage cells (COR = 0.124, P = 0.021; Figs. 8A–8F). The heatmap of immune responses based on CIBERSORT, EPIC, ESTIMATE, MCP counter, QUANTISEQ, TIMER and ssGSEA algorithms was displayed in Fig. 9. These findings powerfully indicated that this FRlncRNAs signature was related to immune cell infiltration in HCC.

Figure 8. The relationship between FRlncRNAs signature and TIICs, ICB molecules based on TIMER results.

(A) Spearman correlation between the signature and B cell; (B) Spearman correlation between the signature and Macrophage cell. (C) Spearman correlation between the signature and Myeloid dendritic cell. (D) Spearman correlation between the signature and Neutrophil cell. (E) Spearman correlation between the signature and CD4+ T cell. (F) Spearman correlation between the signature and CD8+ T cell. (G–I) Significant positive association between our FRlncRNAs signature and ICB receptors PD-1 (R = 0.17; P = 0.0019), CTLA-4 (R = 0.19; P <0.001), and TIM-3 (R = 0.16; P < 0.001). (J–L) The comparison of the expression levels of PD-1, CTLA-4, and TIM-3 between high-risk and low- groups.

Figure 9. Based on CIBERSORT, EPIC, ESTIMATE, MCP counter, QUANTISEQ, ssGSEA and TIMER algorithms, heatmap of immune infiltration in the high- and low-risk groups.

Tumor immunotherapy utilizing ICB had gradually become a promising strategy for therapy of advanced HCC (Sangro et al., 2021; Wing-Sum Cheu & Chak-Lui Wong, 2021; Zongyi & Xiaowu, 2020). In training cohort, we carried out the association between the FRlncRNAs signature and six common ICB therapy-related targets (PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2, TIM-3, IDO1, and CTLA-4) to explore the potential role of FRlncRNAs signature in the immunotherapy of ICB in the patients with HCC. The results showed that the FRlncRNAs signature was positively related to PD −1 (R = 0.17, P = 0.0019), CTLA-4 (R = 0.19, P = <0.001), and TIM-3 (R = 0.16, P < 0.001; except for IDO1, PD-L1, and PD-L2), revealing that the FRlncRNAs signature might play vital roles in assessment of response to ICB immunotherapy in the patients with HCC (Figs. 8G–8I and Fig. S1). Meanwhile, the expression levels of PD-1, CTLA-4 and TIM-3 were significantly higher in high-risk group contrasted with those in low- group (Figs. 8J–8L).

Discussion

Due to the unique molecular features such as genomic and genetic diversities, HCC was considered as a highly heterogeneous malignant tumor (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address wbe, and Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, 2017; (Schulze, Nault & Villanueva, 2016). Studies found that lncRNAs play important roles in the prognosis of HCC, which could become potential and effective molecular targets in the treatment of HCC (DiStefano, 2017; Wei et al., 2019). It could be seen from previous studies that lncRNAs participate in many biological processes such as immune response, autophagy, inflammation, and metabolism, etc (Carpenter & Fitzgerald, 2018; Frankel, Lubas & Lund, 2017; Majidinia & Yousefi, 2016; Mathy & Chen, 2017). At present, emerging studies revealed that some lncRNAs could play significant roles in regulating occurrence and development of disease by promoting ferroptosis (Lu, Xu & Lu, 2020; Wang et al., 2021b; Yang et al., 2020b). That indicated that ferroptosis-related lncRNAs might serve as novel disease molecular biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the treatment of cancer. However, the possible role of the ferroptosis-related lncRNA signature as a potentially useful tactics of treatment have not been reported in HCC. Therefore, we developed a FRlncRNAs signature with great prognosis and predictive value. Meanwhile, we also explored its effect in the response to ICB therapy for the patients with HCC.

Currently, the ferroptosis-related lncRNA signature has only been explored in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (Tang et al., 2021). However, that study had several limitations, such as: small clinical sample sizes and lack of independent external validation datasets, which might lead to unreliable results. Furthermore, other confounding factors like comorbidities or alcohol consumption may also affect the robustness and accuracy of signature, which contained hemochromatosis, alcoholic liver disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, etc (Mao et al., 2020). Considering the above problems, the training cohort and independent validation cohort were utilized to develop a novel FRlncRNAs signature, which could predict the survival of patients with HCC. The results showed that the FRlncRNAs signature mainly involved DNA repair, glycolysis, MYC targets, and tumor-related signaling pathways. Those patients in the high-risk group were associated with worse OS. In addition, this FRlncRNAs signature was credible for predicting the prognosis of patients with HCC, with a high AUC value (average AUC >0.65), and might serve as an indicator to measure the response of patients with HCC to ICB immunotherapy.

With the development of immune checkpoint inhibitors, ICB immunotherapy, as emerging strategies, has revealed treatment effects in HCC (Llovet et al., 2018; Pitt et al., 2016). Currently, immunotherapy has provided a novel promising treatment strategy for HCC (Sim & Knox, 2018). Unfortunately, more than two-third of patients did not respond to ICB treatment (Mushtaq et al., 2018). A new research demonstrated that ferroptosis combined with ICIs could synergistically enhance anti-tumor activity, even in ICI-resistant tumors (Tang et al., 2020). Thus, a novel FRlncRNAs signature was established to investigate the relationship between ICIs and ferroptosis, and predict ICB immunotherapy responses. In our study, the FRncRNAs signature was discovered to be associated with ICIs (i.e., PD-1, CTLA-4, and TIM-3), which indicated that the FRlncRNAs signature have potential to be used to measure the response to ICB therapy. At the same time, the expression levels of these ICIs in high-risk group were higher compared with low- group. That indicated that the FRlncRNAs signature could be applied to predict the expression level of ICIs and have the potential to guide ICB immunotherapy strategies. Moreover, the FRlncRNAs signature was connected with TICIs (B cell, Macrophage, Myeloid dendritic cell, Neutrophil, and CD4+ T cell) in HCC, which implies that this signature may play an important role in immune infiltration. Notably, these findings were consistent with previous studies manifesting that several lncRNAs served as regulators in tumor immunity, for instance immune cell infiltration and antigen release (Carpenter & Fitzgerald, 2018; Denaro, Merlano & Lo Nigro, 2019).

Previous studies have revealed that lncRNAs participated in different biological processes such as immune regulation (Denaro, Merlano & Lo Nigro, 2019), DNA repair and cell cycle (Hu et al., 2018; Majidinia & Yousefi, 2016), and metabolism (Denaro, Merlano & Lo Nigro, 2019), etc. Among this FRlncRNAs signature (RHPN1-AS1, MAPKAPK5-AS1, and PART1) of our study, RHPN1-AS1 could facilitate cell proliferation, and invasion via activating PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in HCC (Song et al., 2020). Another study revealed that RHPN1-AS1 promoted the progression of HCC through regulating miR-596/IGF2BP2 axis (Fen et al., 2020). MAPKAPK5-AS1/PLAGL2/HIF-1 α signaling pathway was found to drive the progression of HCC and MAPKAPK5-AS1 might be a novel therapeutic target (Wang et al., 2021a). Furthermore, MAPKAPK5-AS1 has been discovered to promote the progression of colorectal cancer and thyroid cancer (Ji et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2020b). PART1 was involved in cell migration and invasion, and it could facilitate progression of HCC (Pu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020a). PART1 also played a vital role in the occurrence and development of other cancers. Downregulated PART1 could suppress proliferation and accelerate apoptosis in bladder cancer (Hu et al., 2019). PART1 was regarded as a novel target in the treatment of prostate cancer (Sun et al., 2018). A study found that PART1 could promote cell proliferation in non-small-cell lung cancer cells by targeting miR-17-5p (Chen et al., 2021). Above evidences revealed that these three FRlncRNAs played important roles in development and prognosis of HCC. However, there is no research on their role in the prognosis of HCC via ferroptosis-related mechanism. Our findings may provide a new perspective for the treatment of HCC through ferroptosis-induction in the future.

Additionally, our results showed that the new FRlncRNAs signature possessed a highly predictive ability for OS prediction in the patients with HCC. Stratification analysis indicated that the FRlncRNAs signature based on risk grouping still possessed great predictive ability for survival prediction in each stratum of age (<65 or ≥65 patients), stage (Stage 1–2 or Stage 3–4 patients), grade (Grade 1–2 or Grade 3–4), and male patients, etc.

Several issues remained in the current study. First, the clinical sample size was not large. Second, the prognostic model was demanded to be validated in other enormous datasets to guarantee its robustness. Third, study has shown that HCC could be resistant to conventional chemotherapeutic, which might be associated with induction of ferroptosis-resistance (Galmiche, 2019). However, due to the lack of patients of chemotherapy or radiotherapy in this study, it is impossible to confirm whether the signature can be applied to predict resistance to classical chemotherapy or radiotherapy through ferroptosis-induction. Fourth, the functional experiments should be implemented to reveal the potential biological mechanisms for predicting the influence of FRlncRNAs.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we identified a novel FRncRNAs signature related to prognosis of the patients with HCC, which could be utilized as a powerful tool in predicting the prognosis of patients with HCC. The FRlncRNAs signature could divide clinical characteristic subgroups according to survival. In addition, the signature was connected with ICB targets and TICIs. Hence, our study afforded a possible strategy for individualized risk stratification of the patients with HCC and evaluation response to ICB immunotherapy. The three FRncRNAs might be potential therapeutic targets of HCC.

Supplemental Information

Abbreviations

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- lncRNA

Long non-coding RNA

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- FRlncRNAs

ferroptosis-related lncRNAs

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- OS

overall survival

- KM

Kaplan–Meier

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analyses

- ssGSEA

single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA)

- TIICs

tumor-infiltrating immune cells

- ICB

immune checkpoint blockade

- FDR

false discovery rate

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the project of the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2018A030313632), the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students of GZUCM (S201910572049, 201910572168) and GZUCM Science Fund for Creative Research Groups (2016KYTD10) to Jin Zhang; the project of the Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau of Guangdong Province (20211118) to Fuping Ding; and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students of GZUCM (201910572193) to Jin Huang. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Fuping Ding, Email: hldfp@gzucm.edu.cn.

Jin Zhang, Email: zhjin@gzucm.edu.cn.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Jiaying Liang, Yaofeng Zhi and Wenhui Deng conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Weige Zhou conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Xuejun Li performed the experiments, analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Zheyou Cai performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Zhijian Zhu, Jinxiang Zeng, Wanlan Wu,Ying Dong analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Jin Huang and Yuzhuo Zhang performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Shichao Xu and Yixin Feng performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, and approved the final draft.

Fuping Ding and Jin Zhang conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The data is available at NCBI GEO: GSE14520. All analyzed or generated data are included in the article and the Supplemental Files.

References

- Ai et al. (2020).Ai W, Li F, Yu HH, Liang ZH, Zhao HP. Up-regulation of long noncoding RNA LINC00858 is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Journal of Gene Medicine. 2020:e3179. doi: 10.1002/jgm.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray et al. (2018).Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address wbe, and Cancer Genome Atlas Research N (2017).Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address wbe, and Cancer Genome Atlas Research N Comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2017;169:1327–1341, e1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter & Fitzgerald (2018).Carpenter S, Fitzgerald KA. Cytokines and long noncoding RNAs. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2018;10:a028589. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech & Steitz (2014).Cech TR, Steitz JA. The noncoding RNA revolution-trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell. 2014;157:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charoentong et al. (2017).Charoentong P, Finotello F, Angelova M, Mayer C, Efremova M, Rieder D, Hackl H, Trajanoski Z. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Reports. 2017;18:248–262. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al. (2021).Chen Y, Zhou X, Huang C, Li L, Qin Y, Tian Z, He J, Liu H. LncRNA PART1 promotes cell proliferation and progression in non-small-cell lung cancer cells via sponging miR-17-5p. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2021;122:315–325. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denaro, Merlano & Lo Nigro (2019).Denaro N, Merlano MC, Lo Nigro C. Long noncoding RNAs as regulators of cancer immunity. Molecular Oncology. 2019;13:61–73. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano (2017).DiStefano JK. Long noncoding RNAs in the initiation, progression, and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Noncoding RNA Res. 2017;2:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ncrna.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon et al. (2012).Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison 3rd B, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (2018).European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fen et al. (2020).Fen H, Hongmin Z, Wei W, Chao Y, Yang Y, Bei L, Zhihua S. RHPN1-AS1 drives the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via regulating miR-596/IGF2BP2 Axis. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2020;25:4630–4640. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666191105104549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finotello et al. (2019).Finotello F, Mayer C, Plattner C, Laschober G, Rieder D, Hackl H, Krogsdam A, Loncova Z, Posch W, Wilflingseder D, Sopper S, Ijsselsteijn M, Brouwer TP, Johnson D, Xu Y, Wang Y, Sanders ME, Estrada MV, Ericsson-Gonzalez P, Charoentong P, Balko J, de Miranda N, Trajanoski Z. Molecular and pharmacological modulators of the tumor immune contexture revealed by deconvolution of RNA-seq data. Genome Medicine. 2019;11:34. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0638-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, Lubas & Lund (2017).Frankel LB, Lubas M, Lund AH. Emerging connections between RNA and autophagy. Autophagy. 2017;13:3–23. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1222992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmiche (2019).Galmiche A. Ferroptosis in liver disease. In: Tang D, editor. Ferroptosis in health and disease. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2019. pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Patel & Kurzrock (2017).Goodman A, Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-1-PD-L1 immune-checkpoint blockade in B-cell lymphomas. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2017;14:203–220. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassannia, Vandenabeele & Vanden Berghe (2019).Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T. Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:830–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He et al. (2019).He J, Zuo Q, Hu B, Jin H, Wang C, Cheng Z, Deng X, Yang C, Ruan H, Yu C, Zhao F, Yao M, Fang J, Gu J, Zhou J, Fan J, Qin W, Yang XR, Wang H. A novel, liver-specific long noncoding RNA LINC01093 suppresses HCC progression by interaction with IGF2BP1 to facilitate decay of GLI1 mRNA. Cancer Letters. 2019;450:98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al. (2019).Hu X, Feng H, Huang H, Gu W, Fang Q, Xie Y, Qin C, Hu X. Downregulated long noncoding RNA PART1 inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis in bladder cancer. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment. 2019;18:1533033819846638. doi: 10.1177/1533033819846638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al. (2018).Hu X, Sood AK, Dang CV, Zhang L. The role of long noncoding RNAs in cancer: the dark matter matters. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2018;48:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennis et al. (2016).Jennis M, Kung CP, Basu S, Budina-Kolomets A, Leu JI, Khaku S, Scott JP, Cai KQ, Campbell MR, Porter DK, Wang X, Bell DA, Li X, Garlick DS, Liu Q, Hollstein M, George DL, Murphy ME. An African-specific polymorphism in the TP53 gene impairs p53 tumor suppressor function in a mouse model. Genes and Development. 2016;30:918–930. doi: 10.1101/gad.275891.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji et al. (2019).Ji H, Hui B, Wang J, Zhu Y, Tang L, Peng P, Wang T, Wang L, Xu S, Li J, Wang K. Long noncoding RNA MAPKAPK5-AS1 promotes colorectal cancer proliferation by partly silencing p21 expression. Cancer Science. 2019;110:72–85. doi: 10.1111/cas.13838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim et al. (2017).Kim JE, Patel MA, Mangraviti A, Kim ES, Theodros D, Velarde E, Liu A, Sankey EW, Tam A, Xu H, Mathios D, Jackson CM, Harris-Bookman S, Garzon-Muvdi T, Sheu M, Martin AM, Tyler BM, Tran PT, Ye X, Olivi A, Taube JM, Burger PC, Drake CG, Brem H, Pardoll DM, Lim M. Combination therapy with Anti-PD-1, Anti-TIM-3, and focal radiation results in regression of murine gliomas. Clinical Cancer Research. 2017;23:124–136. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2019).Li CY, Zhang WW, Xiang JL, Wang XH, Wang JL, Li J. Integrated analysis highlights multiple long noncoding RNAs and their potential roles in the progression of human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncology Reports. 2019;42:2583–2599. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2017).Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu JS, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Research. 2017;77:e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang et al. (2019).Liang C, Zhang X, Yang M, Dong X. Recent progress in ferroptosis inducers for cancer therapy. Adv Mater. 2019;31:e1904197. doi: 10.1002/adma.201904197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet et al. (2018).Llovet JM, Montal R, Sia D, Finn RS. Molecular therapies and precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2018;15:599–616. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet et al. (2016).Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, Sangro B, Schwartz M, Sherman M, Gores G. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2016;2:16018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louandre et al. (2015).Louandre C, Marcq I, Bouhlal H, Lachaier E, Godin C, Saidak Z, Francois C, Chatelain D, Debuysscher V, Barbare JC, Chauffert B, Galmiche A. The retinoblastoma (Rb) protein regulates ferroptosis induced by sorafenib in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Letters. 2015;356:971–977. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Xu & Lu (2020).Lu J, Xu F, Lu H. LncRNA PVT1 regulates ferroptosis through miR-214-mediated TFR1 and p53. Life Sciences. 2020;260:118305. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majidinia & Yousefi (2016).Majidinia M, Yousefi B. Long non-coding RNAs in cancer drug resistance development. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016;45:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao et al. (2020).Mao L, Zhao T, Song Y, Lin L, Fan X, Cui B, Feng H, Wang X, Yu Q, Zhang J, Jiang K, Wang B, Sun C. The emerging role of ferroptosis in non-cancer liver diseases: hype or increasing hope? Cell Death & Disease. 2020;11:518. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2732-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathy & Chen (2017).Mathy NW, Chen XM. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and their transcriptional control of inflammatory responses. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2017;292:12375–12382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.760884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq et al. (2018).Mushtaq MU, Papadas A, Pagenkopf A, Flietner E, Morrow Z, Chaudhary SG, Asimakopoulos F. Tumor matrix remodeling and novel immunotherapies: the promise of matrix-derived immune biomarkers. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2018;6:65. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0376-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman et al. (2015).Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nature Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino et al. (2017).Nishino M, Ramaiya NH, Hatabu H, Hodi FS. Monitoring immune-checkpoint blockade: response evaluation and biomarker development. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2017;14:655–668. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oweira et al. (2017).Oweira H, Petrausch U, Helbling D, Schmidt J, Mehrabi A, Schob O, Giryes A, Abdel-Rahman O. Prognostic value of site-specific extra-hepatic disease in hepatocellular carcinoma: a SEER database analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:695–701. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1294485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt et al. (2016).Pitt JM, Vetizou M, Daillere R, Roberti MP, Yamazaki T, Routy B, Lepage P, Boneca IG, Chamaillard M, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. resistance mechanisms to immune-checkpoint blockade in cancer: tumor-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors. Immunity. 2016;44:1255–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu et al. (2020).Pu J, Tan C, Shao Z, Wu X, Zhang Y, Xu Z, Wang J, Tang Q, Wei H. Long noncoding RNA PART1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via targeting miR-590-3p/HMGB2 axis. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2020;13:9203–9211. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S259962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racle et al. (2017).Racle J, de Jonge K, Baumgaertner P, Speiser DE, Gfeller D. Simultaneous enumeration of cancer and immune cell types from bulk tumor gene expression data. Elife. 2017;6:e26476. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangro et al. (2021).Sangro B, Sarobe P, Hervas-Stubbs S, Melero I. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2021;13:1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00438-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, Nault & Villanueva (2016).Schulze K, Nault JC, Villanueva A. Genetic profiling of hepatocellular carcinoma using next-generation sequencing. Journal of Hepatology. 2016;65:1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi et al. (2020).Shi J, Jiang D, Yang S, Zhang X, Wang J, Liu Y, Sun Y, Lu Y, Yang K. LPAR1, correlated with immune infiltrates, is a potential prognostic biomarker in prostate cancer. Frontiers in Oncology. 2020;10:846. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim & Knox (2018).Sim HW, Knox J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of immunotherapy. Current Problems in Cancer. 2018;42:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song et al. (2020).Song XZ, Ren XN, Xu XJ, Ruan XX, Wang YL, Yao TT. LncRNA RHPN1-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion through targeting miR-7-5p and activating PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment. 2020;19:1533033820957023. doi: 10.1177/1533033820957023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Stockwell et al. (2017).Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascon S, Hatzios SK, Kagan VE, Noel K, Jiang X, Linkermann A, Murphy ME, Overholtzer M, Oyagi A, Pagnussat GC, Park J, Ran Q, Rosenfeld CS, Salnikow K, Tang D, Torti FM, Torti SV, Toyokuni S, Woerpel KA, Zhang DD. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171:273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. (2018).Sun M, Geng D, Li S, Chen Z, Zhao W. LncRNA PART1 modulates toll-like receptor pathways to influence cell proliferation and apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Biological Chemistry. 2018;399:387–395. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2017-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. (2016a).Sun X, Niu X, Chen R, He W, Chen D, Kang R, Tang D. Metallothionein-1G facilitates sorafenib resistance through inhibition of ferroptosis. Hepatology. 2016a;64:488–500. doi: 10.1002/hep.28574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. (2016b).Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R, Tang D. Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2016b;63:173–184. doi: 10.1002/hep.28251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang et al. (2021).Tang Y, Li C, Zhang Y-J, Wu Z-H. Ferroptosis-Related Long Non-Coding RNA signature predicts the prognosis of Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;17:702–711. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.55552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang et al. (2020).Tang R, Xu J, Zhang B, Liu J, Liang C, Hua J, Meng Q, Yu X, Shi S. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in anticancer immunity. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2020;13:110. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00946-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2021b).Wang Z, Chen X, Liu N, Shi Y, Liu Y, Ouyang L, Tam S, Xiao D, Liu S, Wen F, Tao Y. A nuclear long non-coding RNA LINC00618 accelerates ferroptosis in a manner dependent upon apoptosis. Molecular Therapy. 2021b;29:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2018).Wang H, Liang L, Dong Q, Huan L, He J, Li B, Yang C, Jin H, Wei L, Yu C, Zhao F, Li J, Yao M, Qin W, Qin L, He X. Long noncoding RNA miR503HG, a prognostic indicator, inhibits tumor metastasis by regulating the HNRNPA2B1/NF-kappaB pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 2018;8:2814–2829. doi: 10.7150/thno.23012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2021a).Wang L, Sun L, Liu R, Mo H, Niu Y, Chen T, Wang Y, Han S, Tu K, Liu Q. Long non-coding RNA MAPKAPK5-AS1/PLAGL2/HIF-1alpha signaling loop promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2021a;40:72. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01868-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei et al. (2019).Wei L, Wang X, Lv L, Liu J, Xing H, Song Y, Xie M, Lei T, Zhang N, Yang M. The emerging role of microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs in drug resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular Cancer. 2019;18:147. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1086-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing-Sum Cheu & Chak-Lui Wong (2021).Wing-Sum Cheu J, Chak-Lui Wong C. Mechanistic Rationales guiding Combination Hepatocellular Carcinoma Therapies involving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Hepatology. 2021 doi: 10.1002/hep.31840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang et al. (2020a).Yang T, Chen WC, Shi PC, Liu MR, Jiang T, Song H, Wang JQ, Fan RZ, Pei DS, Song J. Long noncoding RNA MAPKAPK5-AS1 promotes colorectal cancer progression by cis-regulating the nearby gene MK5 and acting as a let-7f-1-3p sponge. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research. 2020a;39:139. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01633-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang et al. (2019).Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019;16:589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang et al. (2020b).Yang Y, Tai W, Lu N, Li T, Liu Y, Wu W, Li Z, Pu L, Zhao X, Zhang T, Dong Z. lncRNA ZFAS1 promotes lung fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and ferroptosis via functioning as a ceRNA through miR-150-5p/SLC38A1 axis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020b;12:9085–9102. doi: 10.18632/aging.103176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye et al. (2019).Ye J, Zhang J, Lv Y, Wei J, Shen X, Huang J, Wu S, Luo X. Integrated analysis of a competing endogenous RNA network reveals key long noncoding RNAs as potential prognostic biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2019;120:13810–13825. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi et al. (2020).Yi M, Nissley DV, McCormick F, Stephens RM. ssGSEA score-based Ras dependency indexes derived from gene expression data reveal potential Ras addiction mechanisms with possible clinical implications. Scientific Reports. 2020;10:10258. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66986-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara et al. (2013).Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martinez E, Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Trevino V, Shen H, Laird PW, Levine DA, Carter SL, Getz G, Stemke-Hale K, Mills GB, Verhaak RG. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nature Communications. 2013;4:2612. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan et al. (2016).Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R, Tang D. CISD1 inhibits ferroptosis by protection against mitochondrial lipid peroxidation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2016;478:838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng et al. (2020).Zeng J, Liu Z, Zhang C, Hong T, Zeng F, Guan J, Tang S, Hu Z. Prognostic value of long non-coding RNA SNHG20 in cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e19204. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai et al. (2018).Zhai L, Ladomersky E, Lenzen A, Nguyen B, Patel R, Lauing KL, Wu M, Wainwright DA. IDO1 in cancer: a Gemini of immune checkpoints. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2018;15:447–457. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Liu & Yu (2017).Zhao X, Liu Y, Yu S. Long noncoding RNA AWPPH promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression through YBX1 and serves as a prognostic biomarker. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2017;1863:1805–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou & Bao (2020).Zhou N, Bao J. FerrDb: a manually curated resource for regulators and markers of ferroptosis and ferroptosis-disease associations. Database (Oxford) 2020;2020:baaa021. doi: 10.1093/database/baaa021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. (2020b).Zhou Y, Liu S, Luo Y, Zhang M, Jiang X, Xiong Y. IncRNA MAPKAPK5-AS1 promotes proliferation and migration of thyroid cancer cell lines by targeting miR-519e-5p/YWHAH. European Journal of Histochemistry. 2020b;64:3177. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2020.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. (2020a).Zhou C, Wang P, Tu M, Huang Y, Xiong F, Wu Y. Long non-coding RNA PART1 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via miR-149-5p/MAP2K1 axis. Cancer Management and Research. 2020a;12:3771–3782. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S246311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zongyi & Xiaowu (2020).Zongyi Y, Xiaowu L. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Letters. 2020;470:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The data is available at NCBI GEO: GSE14520. All analyzed or generated data are included in the article and the Supplemental Files.