Abstract

Background and Aims:

Regional anaesthesia has been used to reduce acute post-operative pain as well as opioid-related side effects in breast cancer surgery. Erector spinae plane (ESP) block is a relatively new fascial plane block being tried in various surgical procedures. Our study is a double-blind randomised trial, designed to prove the efficacy of this block in breast surgeries.

Methods:

Seventy female patients scheduled for unilateral breast surgery were enroled in this prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Patients were randomised to group A and group B. All patients received general anaesthesia while group B received additional ultrasound-guided erector spinae block given at thoracic level—T5 with 20ml of 0.25% bupivacaine. Time to first rescue analgesia was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were total intraoperative opioid consumption, pain scores over 24 h, post-operative nausea and vomiting and patient satisfaction score at discharge. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check the normality of each variable. A comparison was done using Mann–Whitney test and the level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results:

The median time to first rescue analgesia in group A versus group B was 1 h (1–12h) versus 8 h (1–26h), respectively, with a P value of 0.044. Group B patients had lower pain scores post-operatively and better satisfaction scores at discharge. There was no statistically significant difference in intraoperative fentanyl consumption.

Conclusion:

Ultrasound-guided ESP block with general anaesthesia offers superior post-operative analgesia compared to general anaesthesia alone in patients undergoing unilateral nonreconstructive breast cancer surgeries.

Keywords: Breast cancer surgery, erector spinae plane block, post-operative analgesia, ultrasound-guided block

INTRODUCTION

In India, breast cancer ranks first with an incidence rate of 25.8 per 100,000.[1] Amongst the various treatment modalities, surgery remains the mainstay of treatment. General anaesthesia with volatile agents and opioids has been traditionally used for breast surgeries. One important side effect of opioid usage is post-operative nausea and vomiting with an incidence of 80%.[2] After breast surgery, the incidence of chronic post-operative pain ranges from 25% to 50%. Major risk factors for chronic post-operative pain are uncontrolled acute post-operative pain, its intensity, and analgesic consumption in the acute post-operative period.[3]

Regional anaesthesia with its opioid-sparing effect is widely preferred these days as it dramatically reduces acute post-surgical pain and opioid-related side effects.[4]

Thoracic epidural analgesia, paravertebral block and pectoralis nerve block are established techniques to provide analgesia in breast surgery.[5,6] All these techniques have their merits and demerits.

A relatively newer fascial plane block is the erector spinae plane (ESP) block, first described by Forero et al.[7] It is simple, safe, easy to perform, and is not a time-consuming procedure.[7] Recently published case reports and very few prospective studies on ESP block as a regional technique in breast surgeries have shown better post-operative analgesia, opioid-sparing effect, possible immunomodulatory effect and superior patient satisfaction. The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of ultrasound-guided ESP block in breast oncosurgeries.

METHODS

This was a prospective interventional double-blind randomised controlled study. Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained and the study was registered with the Clinical Trial Registry of India, CTRI/2019/06/019701. Patients were enroled from July to November 2019 after taking written informed consent. Seventy female patients aged 18–65 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I and II, undergoing unilateral breast cancer surgery (modified radical mastectomy, breast conservational surgery, simple mastectomy and axillary clearance) were included. Exclusion criteria included patient refusal, history of bronchial asthma, breast surgery with port insertion or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, reconstructive surgeries, infection at the injection site, spinal deformities, coagulation disorders, allergy to local anaesthetics, history of opioid usage for chronic pain and cognitive/psychiatric disorders.

Patients were randomised by computer-generated random numbers, on the day of surgery. They were allocated to either control group— group “A”, who received only general anaesthesia, or study group— group “B” who received the ESP block with general anaesthesia. Patients in group B received ultrasound-guided ESP block at T5 level with bupivacaine (0.25%, 20ml) while those in the control group did not receive any intervention.

In the induction room, the monitors (pulse oximeter, electrocardiogram and noninvasive blood pressure at 5-min interval) were attached and intravenous access was secured. In both groups, anaesthesia was induced with inj. propofol 2mg/kg, fentanyl 2 μg/kg and muscle relaxant atracurium 0.5mg/kg IV. An appropriate size supraglottic airway device (SGA) or endotracheal tube was placed. Maintenance of anaesthesia was with 50% oxygen in air, sevoflurane (0.9–1.2 minimum alveolar concentration) and intermittent positive pressure ventilation. Patients randomised to group B were given ESP block under general anaesthesia in the lateral decubitus position with the operative site facing upwards.

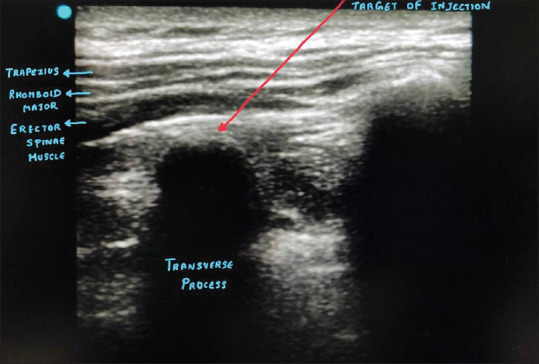

Theblock was performed using a linear probe (5–10 MHz) of ultrasound (SonoSite, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA), by investigators of the study Raghu S Thota (RST) and Prathiba Thiagarajan (PT) who had performed at least ten blocks before the study.[8] Under sterile aseptic precautions, an ESP block was performed at the T5 level [Figure 1]. The tip of the transverse process was targeted by the block needle and 20ml of 0.25% bupivacaine deposited deep to the erector spinae muscle plane. The operation theatre anaesthetist and the Acute Pain Services (APS) team, (which consisted of a senior and junior registrar) who evaluated the patient in the post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU) and ward were blinded to the study intervention.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image showing structures identified while performing erector spinae block

Patients were shifted to the operating room. Anaesthesia was maintained with 50% oxygen in air, sevoflurane (0.9–1.2 minimum alveolar concentration) and intermittent positive pressure ventilation via a Drager anaesthesia workstation. The surgical incision was made 15–20 min from the time of the block. Intraoperative fentanyl boluses of 0.5 μg/kg IV were given whenever there was a response to pain as assessed by a 20% increase in heart rate or blood pressure from baseline.

During skin incision closure, inj. paracetamol 15 mg/kg, inj. diclofenac 1mg/kg, inj. ondansetron 0.1 mg/kg and inj. dexamethasone 0.08 mg/kg were given intravenously. Neuromuscular blockade was reversed with IV neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.008 mg/kg. After tracheal extubation or removal of the SGA, patients were shifted to the PACU.

The primary outcome, time to first rescue analgesia (time point measured from the end of surgery to request of analgesic or numerical rating scale (NRS)≥ 4), was noted in both groups of patients by the APS team. Patients who did not require rescue analgesia in 24 h were followed up further for 48 h by the APS team. Inj. tramadol 1 mg/kg IV along with inj. metoclopramide 10 mgIV was given as first rescue analgesia if NRS ≥4 or when the patient requested for pain medication. IV paracetamol 15 mg/kg was given if ≥8 h had elapsed from the intraoperative paracetamol dose.

Dermatomal distribution of analgesia was checked post-operatively in the PACU by the APS team, using an ice test once the patient was wide awake.

Secondary outcomes, like pain scores, were assessed by the APS team using the NRS 0–10, (0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain) at 0, 1, 2, 6, 12 and 24h.

Intraoperative total opioid consumption and the occurrence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) were also recorded in both groups. Patient satisfaction scores were assessed at discharge by a scoring system ranging from 1to 4 (1—Not satisfied, 2—Fairly satisfied, 3—Satisfied, 4—Extremely satisfied).

In a previous study done by El-Sheikh et al.[9] on modified pectoral nerve block in breast surgeries, time to rescue analgesia was increased by 2.30 h by the block. We expected that the erector spinae block would prolong the time to rescue analgesia by a mean of 4 ± 2 h. At significance level (alpha) of 0.05 and power 80%, the sample size calculated was 25 patients in each group. To account for errors, protocol violations, failed blocks, etc., a total of 35 patients were included in each group.

All available data were analysed descriptively for each intervention group. Differences in baseline variables were analysed by Mann–Whitney test for comparisons between the two groups. All the data were summarised as either mean or counts for continuous or categorical variables, respectively. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check the normality of each variable. The primary endpoint was the median time to rescue analgesia between the two groups. The median was reported with 95% CI and comparison between groups was done using Mann–Whitney test. Secondary endpoints were analysed using Mann–Whitney test and Chi-square test. All the analyses were two-sided, and the level of significance was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences International Business Machines Corp. (Released 2017, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, and Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

RESULTS

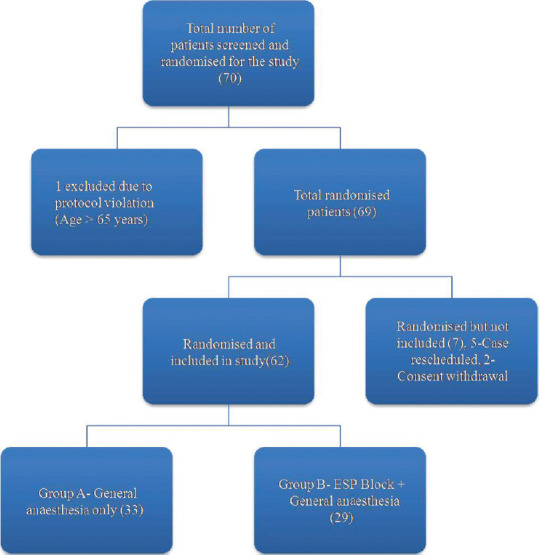

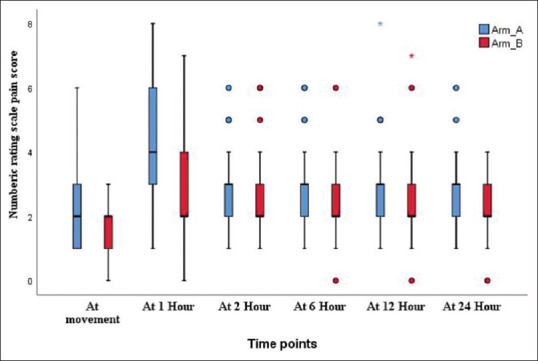

Seventy patients scheduled for breast surgery were screened and those willing to consent were recruited. Out of these, 8 patients were excluded and 62 patients were randomised into 2groups [Figure 2]. Both the groups were comparable in terms of demographic variables [Table 1]. The mean duration for the time to rescue analgesia in group A was 1 h compared to 8 h in group B [Table 2]. The mean pain score at rest was lower in group B compared to group A, and statistically significant at 2 h. The mean pain score with the movement of the arm [Figure 3] was also lower in group B compared to group A, statistically significant at 0, 1,624 h. None of the patients had complaints of nausea or vomiting in the post-operative period. In group A, 12% of the patients were not satisfied while none of those patients who received ESP block (0%) were dissatisfied [Table 3]. Out of 29 patients who received the ESP Block, 14 patients (48.3%) had a unilateral T2–T6 blockade on side of the injection and 12 patients (41.4%) had a unilateral T2–T8 blockade on side of injection. Three patients (10.3%) had a patchy blockade of dermatomes. No complications were encountered.

Figure 2.

CONSORT flowchart of the study

Table 1.

Demographic variables of two groups

| VARIABLE | Group A (Control group) (n=33) | Group B (ESP group) (n=29) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean±SD) | 48.76±9.47 | 48.59±9.15 | ||

| Type of surgery | BCT | 45.5% | 41.3% | 1.000 |

| SMAC | 27.3% | 6.8% | 0.800 | |

| MRM | 27.3% | 51.7% | 0.333 |

BCT=Breast Conserving Surgery; SMAC—Simple Mastectomy+Axillary Clearance, MRM- Modified Radical Mastectomy, SD-Standard deviation

Table 2.

Time to rescue analgesic in group A (Control) and group B (erector spinae plane block)

| Primary objective | Group A | Group B | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to rescue analgesia (in hours) Median (range) | 1 (1-12) | 8 (1-26) | 0.044 |

Figure 3.

Box and Whiskers chart showing mean pain scores with arm movement between control group (Arm A) and ESP group (Arm B)

Table 3.

Satisfaction scores between group A and group B

| Satisfaction scores | Group A | Group B |

|---|---|---|

| 1-NOT SATISFIED | 4 (12.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| 2-FAIRLY SATISFIED | 18 (54.5%) | 11 (37.9%) |

| 3-SATISFIED | 8 (24.2%) | 14 (48.3%) |

| 4-EXTREMELY SATISFIED | 3 (9.1%) | 4 (13.8%) |

DISCUSSION

We conducted a double-blind randomised controlled trial to assess the efficacy of the relatively new regional technique, the ESP block for breast cancer surgeries. ESP block was found to be effective in post-operative pain control by prolonging the time to rescue analgesia. It also provided lower pain scores and better satisfaction scores. Kwon et al. in a case report series[10] of three patients who underwent total mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection under ESP block found that they required their first rescue dose of fentanyl between 12–15 h after surgery, which is relatable to our study.

We found lower pain scores in group B in comparison to group A at rest, although they were statistically significant only at 0 and 1 h post-operatively. Pain scores with the movement were also lower in group B than in group A at 0, 1,624 hpost-operatively, similar to the findings of Singh et al.[11] and Oksuz et al.[12] who also found significantly lower pain scores in the ESP group compared to the control group.

In our study, we found no difference in the intraoperative opioid consumption between the two groups, similar to the findings in other studies.[13,14] After an ESP block, local anaesthetic spreads to the paravertebral region and acts like a paravertebral block. It has been found that the paravertebral block was insufficient to cover the axillary region during axillary dissection.[15] Therefore, ESP block too may be inadequate to cover the axillary region, resulting in intraoperative fentanyl requirement similar to that in patients who did not receive ESP block. Ueshima et al.[16] also found that ESP block did not cover the anterior branches of intercostal nerves and that it cannot be used as a sole regional technique for complete analgesia. This is supported by the findings of a cadaveric study by Ivanusic et al.[17]

Altiparmak et al.[18] concluded that the PECS block was superior to the ESP block, with lower tramadol intake and lower pain scores in the post-operative period. This may be because the pectoral nerve block covers medial and lateral pectoral nerves, thoracic intercostal nerves, intercostobrachial nerve and long thoracic nerves, and provides good analgesia for both breast and axillary areas.[19]

None of our patients included in the study had nausea or vomiting in the 24 h post-operative period. This may be attributable to the fact that we did not use nitrous oxide during anaesthesia, and the use of dual antiemetics (ondansetron and dexamethasone) intraoperatively for all patients. As an institution protocol, we gave metoclopramide along with tramadol when rescue analgesia was required. Gürkan et al.[20] found no significant difference in PONV scores between the general anaesthesia group and ESP group. However, they used nitrous oxide for maintenance of anaesthesia, gave ondansetron as the sole antiemetic and used patient-controlled analgesia with morphine for post-operative pain control, all of which could have contributed to PONV.

More patients in group B were extremely satisfied (score 4) and satisfied (score 3) and none of them were dissatisfied (score 1), whereas patients in group A were mostly only fairly satisfied (score2) and even some were dissatisfied (score 1). Singh et al.[11] in their study also found that satisfaction scores were better in the ESP group than in the control group.

Our study was adequately powered and randomised. Being a double-blind study, patient and investigator bias was avoided. We were able to achieve lower pain scores throughout the post-operative period. The block was given before surgery and hence it acted as pre-emptive analgesia as well. Although three patients had patchy block, they were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. We have checked the sensory dermatomes covered; thus, we were able to map the spread and coverage of this block.

Our study was a comparison between ESP block with general anaesthesia, which is a standard practice in our institute. Although sensory levels were checked in PACU, it was difficult to interpret the dermatomes by the ice test when patients were sedated or drowsy in the PACU, and the surgical dressings interfered with the examination. There is a possibility that there was not enough contact time for local anaesthetic and action as surgery was initiated within 15–20 min after the performance of the block. We did not follow-up with patients after discharge; hence, we could not assess the effect of ESP block on chronic pain.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that ultrasound-guided ESP block with general anaesthesia offers superior post-operative analgesia compared to general anaesthesia alone in patients undergoing unilateral nonreconstructive breast cancer surgeries and is associated with better patient satisfaction scores at discharge. There was no significant difference in intraoperative fentanyl consumption.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malvia S, Bagadi SA, Dubey US, Saxena S. Epidemiology of breast cancer in Indian women. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:289–95. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujii Y. Prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients scheduled for breast surgery. Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26:427–37. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200626080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Guyatt GH, Kennedy SA, Romerosa B, Kwon HY, Kaushal A, et al. Predictors of persistent pain after breast cancer surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. CMAJ. 2016;188:E352–61. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tripathy S, Rath S, Agrawal S, Rao PB, Panda A, Mishra TS, et al. Opioid-free anaesthesia for breast cancer surgery: An observational study. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34:35–40. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_143_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein SM, Bergh A, Steele SM, Georgiade GS, Greengrass RA. Thoracic paravertebral block for breast surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1402–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200006000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakraborty A, Khemka R, Datta T, Mitra S. COMBIPECS, the singleinjection technique of pectoral nerve blocks 1 and 2: A case series. J Clin Anesth. 2016;35:365–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forero M, Adhikary SD, Lopez H, Tsui C, Chin KJ. The erector spinae plane block: A novel analgesic technique in thoracic neuropathic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41:621–7. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niazi AU, Haldipur N, Prasad AG, Chan VW. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia performance in the early learning period: Effect of simulation training. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37:51–4. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31823dc340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Sheikh SM, Fouad A, Bashandy GN. Efficacy of modified PECs block in control of perioperative pain in breast surgeries. Med J Cairo Univ. 2017;85:961–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon WJ, Bang SU, Sun WY. Erector spinae plane block for effective analgesia after total mastectomy with sentinel or axillary lymph node dissection: A report of three cases. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e291. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Kumar G, Akhileshwar Ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in modified radical mastectomy: A randomised control study. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63:200–4. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_758_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oksuz G, Bilgen F, Arslan M, Duman Y, Urfalıoglu A, Bilal B. Ultrasound-guided bilateral erector spinae block versus tumescent anesthesia for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing reduction mammoplasty: A randomized controlled study. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43:291–6. doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talawar P, Kumar A, Bhoi D, Singh A. Initial experience of erector spinae plane block in patients undergoing breast surgery: A case series. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13:72–4. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_560_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar S, Goel D, Sharma SK, Ahmad S, Dwivedi P, Deo N, et al. A randomised controlled study of the post-operative analgesic efficacy of ultrasound-guided pectoral nerve block in the first 24 h after modified radical mastectomy. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62:436–42. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_523_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson J, Ariyarathenam A, Dunn J, Ford P. Breast surgery using thoracic paravertebral blockade and sedation alone. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2014;2014:127467. doi: 10.1155/2014/127467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueshima H, Otake H. Limitations of the Erector Spinae Plane (ESP) block for radical mastectomy. J Clin Anesth. 2018;51:97. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivanusic J, Konishi Y, Barrington MJ. A cadaveric study investigating the mechanism of action of erector spinae blockade. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43:567–71. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altıparmak B, Toker MK, Uysal Aİ, Turan M, Demirbilek SG. Comparison of the effects of modified pectoral nerve block and erector spinae plane block on postoperative opioid consumption and pain scores of patients after radical mastectomy surgery: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2019;54:61–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Versyck B, Groen G, van Geffen GJ, Van Houwe P, Bleys RL. The pecs anesthetic blockade: A correlation between magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound imaging, reconstructed cross-sectional anatomy and cross-sectional histology. Clin Anat. 2019;32:421–9. doi: 10.1002/ca.23333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gürkan Y, Aksu C, Kuş A, Yörükoğlu UH, Kılıç CT. Ultrasound guided erector spinae plane block reduces postoperative opioid consumption following breast surgery: A randomized controlled study. J Clin Anesth. 2018;50:65–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]