Abstract

Dual-acting hybrid anti-oxidant/anti-inflammatory agents were developed employing the principle of pharmacophore hybridization. Hybrid agents were synthesized by combining stable anti-oxidant nitroxides with conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Several of the hybrid nitroxide-NSAID conjugates displayed promising anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects on two Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) cells (A549 and NCI-H1299) and in ameliorating oxidative stress induced in 661 W retinal cells. One ester-linked nitroxide-aspirin analogue (27) delivered better anti-inflammatory effects (cyclooxygenase inhibition) than the parent compound (aspirin), and also showed similar reactive oxygen scavenging activity to the anti-oxidant, Tempol. In addition, a nitroxide linked to the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin (39) significantly ameliorated the effects of oxidative stress on 661W retinal neurons at efficacies greater or equal to the anti-oxidant Lutein. Other examples of the hybrid conjugates displayed promising anti-cancer activity, as demonstrated by their inhibitory effects on the proliferation of A549 NSCLC cells.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Inflammation, Cyclooxygenase, Dual-action, Nitroxides, A549 non-small cell lung cancer, NSAID, Oxidative stress, Retina, Photoreceptors, Pharmacophore hybridization, Reactive oxygen species

1. Introduction

Chronic inflammation is a key contributing factor in the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of numerous inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and some cancers [1–10]. Chronic inflammation is mainly characterized by oxidative stress and prolonged and excessive inflammation that may translate into an irreparable damage to host tissues and, in severe situations, organ malfunction or death [11,12]. In general, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most common therapeutic agents used to manage inflammatory symptoms [9,13–15]. NSAIDs are a structurally diverse group of drugs with a similar mode of action. They exert their therapeutic action (as anti-pyretics, anti-inflammatories and analgesics) mainly by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme [6,14–24]. COX has two main isoforms: COX-1 is the constitutionally expressed isoform that, under physiological conditions, is involved in basic cytoprotective functions such as maintaining the gastrointestinal mucosal integrity. COX-2 is inducibly expressed, mainly in response to inflammatory stimuli from infections or injuries [6,9,13].

Most traditional NSAIDs, such as indomethacin and aspirin, inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes. The non-selectivity of conventional NSAID therapy can lead to adverse side effects, notably gastrointestinal ulceration and bleeding, platelet dysfunction and renal complications, as a result of decreased levels of cytoprotective prostaglandins [25]. Notably, oxidative stress is recognized as a major contributor to NSAID-induced gastric mucosa ulceration [26].

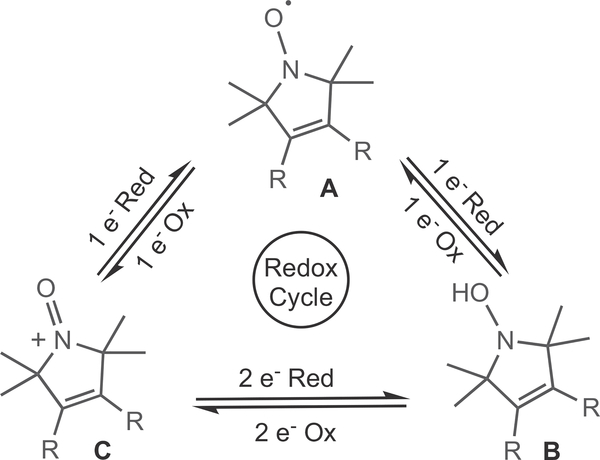

Thus, to effectively manage chronic inflammatory diseases and limit the associated NSAID-induced damage, there is a clear need for an effective anti-oxidant intervention. Our approach to this [27] was to exploit the anti-oxidant capacity of stable nitroxide compounds - which is mainly attributed to the redox cycle that involves the nitroxide (A), and its hydroxylamine (B) and oxoammonium ion (C) derivatives (Scheme 1). This redox cycle enables nitroxides to protect biological tissues against oxidative stress, potentially via superoxide dismutase-mimetic activity, via direct scavenging of radicals and reaction with reactive oxygen species (ROS), and/or via the inhibition of lipid peroxidation processes and enzymes that produce ROS such as myeloperoxidase [1,28,29].

Scheme 1.

Reversible redox cycle of nitroxides.

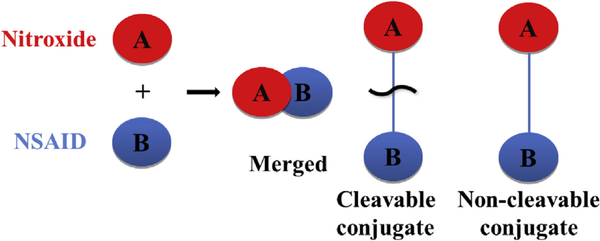

Our aim in this work was to employ the pharmacophore hybridization strategy [30,31] to synthetically combine anti-oxidant nitroxides with a series of NSAIDs to produce novel hybrid dual-acting, nitroxide-based NSAID agents. The hybrid agents were constructed by either merging the two structural subunits or via cleavable (ester and amide bonds) and non-cleavable (amine bond) linkages (Scheme 2). We anticipated that the hybrid agents would retain the anti-inflammatory therapeutic benefits of the parent templates (anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects) and at the same time, the presence of the nitroxide unit would minimize the drug-induced oxidative stress-related side effects. To this end, we report herein the synthesis and some properties of NSAID pharmacophores (32 examples including aspirin, salicylic acid, indomethacin, 5-aminosalicylic acid 5-ASA and 2-hydroxy-5-[2-(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)-ethylaminobenzoic acid) linked with various nitroxide compounds and the therapeutic evaluation of representative lead compounds on 3 well studied cell lines linked to oxidative stress.

Scheme 2.

The design of novel nitroxide-NSAID agents employing pharmacophore hybridization strategies a.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

The salicylate class of NSAIDs was first incorporated with antioxidant nitroxides by taking advantage of the structural similarities of the parent templates. Specifically, pyrroline nitroxide 2 was merged with salicylic acid 1 and acetylsalicylic acid 3 to produce new hybrid nitroxide-salicylate molecules 5-carboxy-6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2yloxyl 4 (salicylic acid-TMIO) and 5-carboxy-6-acetoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoin-2-yloxyl 5 (aspirin-TMIO) as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Parent templates and merged-hybrid nitroxide-salicylate target compounds.

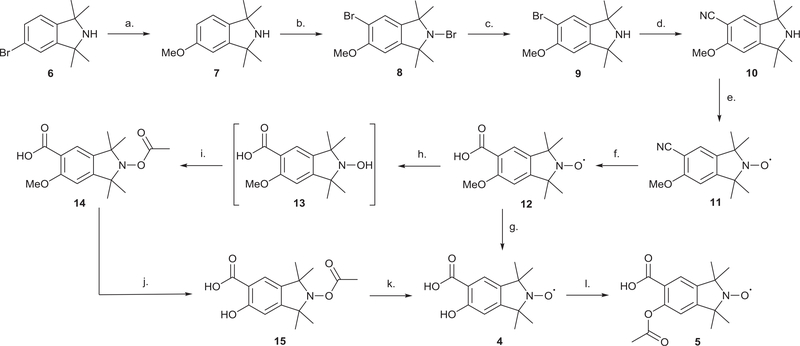

The synthesis of the merged-hybrid target compounds 4 and 5 is outlined in Scheme 3. The 5-bromo-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline precursor 6 was synthesized in three steps from commercially available phthalic anhydride by following previous established literature procedures [32].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of merged salicylic acid TMIO 4 and aspirin TMIO 5a.

When bromoamine 6 was subjected to a copper (I) catalyzed methanolysis, in the presence of dimethylformamide as co-solvent, the 5-methoxyamine derivative 7 was obtained in 88% yield. Selective ring mono-bromination of 7, achieved with bromine in the presence of anhydrous aluminium chloride, yielded the 2,5-dibromo compound 8 in good yield (78%) which was subsequently reduced to the corresponding secondary amine 9 in excellent yield (98%). The cyanation of 9 was achieved using potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) (K4[Fe(CN)6]), as the cyanide source. In this case, the aminonitrile 10 was obtained in high yield by heating a reaction mixture of 9 and K4[Fe(CN)6] at reflux in the presence of catalytic CuI with N-butylimidazole as a co-solvent. The amino nitrile 10 was oxidized to the corresponding nitroxide derivative 11 (94%) under mild oxidation conditions using m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA). Basic hydrolysis of 11 furnished the corresponding carboxylic acid 12 in 89% yield. The target salicylic acid TMIO 4 was obtained initially by direct de-methylation of compound 12 using boron tribromide. Using this reagent however only gave compound 4 in a modest yield (40%). The low yield was attributed to the potential formation of a complex between BBr3 and the nitroxide moiety. Such nitroxide-BBr3 complex formation could initiate multiple degradation pathways for both the starting material and the desired nitroxide targets. Alternatively, the nitroxide moiety of 12 was first protected with an acetyl protecting group prior to the de-methylation. This was achieved by first reducing compound 12 to its corresponding hydroxylamine 13 via palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation. The in situ generated hydroxylamine 13 was then allowed to react with acetyl chloride in the presence triethylamine to give the N-acetyl protected compound 14. Compound 14 was then de-methylated using boron tribromide to afford N-acetoxy salicylic acid 15 which was subsequently hydrolyzed to the desired salicylic acid TMIO 4 in 75% overall yield over the three steps from 12. The target aspirin-TMIO 5 was obtained almost quantitatively by acetylating salicylic acid-TMIO 4 with acetyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine.

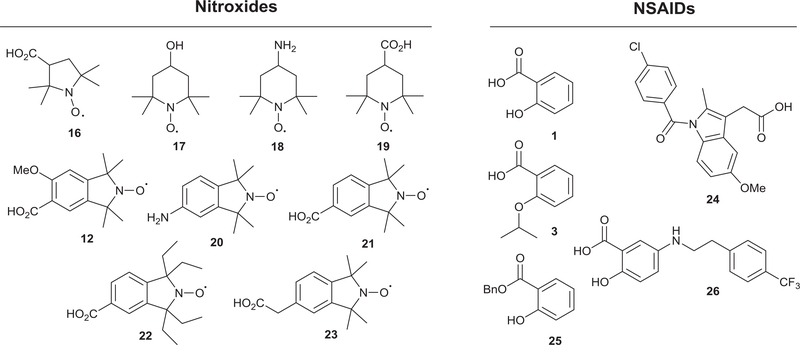

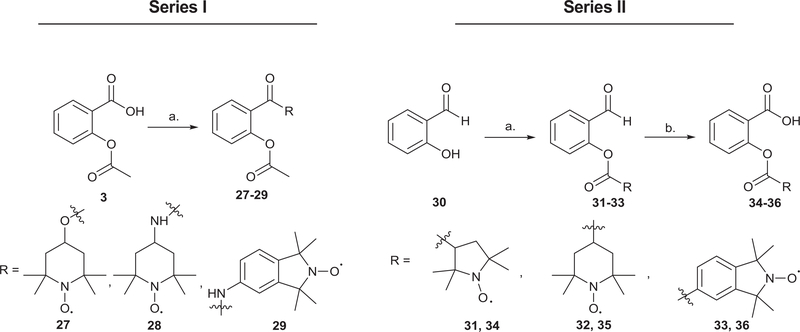

Fig. 2 shows the structures of the parent templates (stable nitroxides and NSAIDs) used for the synthesis of the cleavable and non-cleavable nitroxide-NSAID hybrid conjugates. The ester and amide-linked nitroxide-aspirin conjugates (27–29) were synthesized by reacting aspirin with the respective nitroxide precursors (17, 18 and 20) under carbodiimide coupling conditions (Scheme 4, Series I).

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of parent nitroxides and NSAIDs.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of two series of salicylate-nitroxide conjugates a,b.

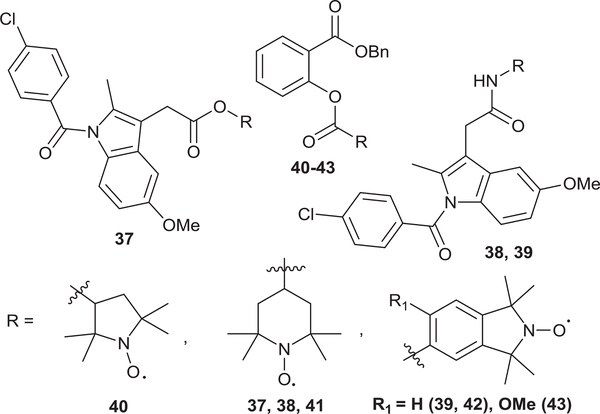

With the next set of target nitroxide-salicylate conjugates (34–36), the o-formyl phenyl ester nitroxide intermediates (31–33) were obtained following the carbodiimide coupling of carboxylic acid nitroxides (16, 19 and 21) with salicylaldehyde 30 (Scheme 4, Series II). The o-formyl derivatives (31–33) were then oxidized to the corresponding salicylates (34–36) in high yields (80−88%) under Pinnick oxidation conditions. Similar structural modifications were carried out with indomethacin 24 and benzyl 2-hydroxybenzoate 25 to give novel indomethacin and benzyl salicylate-nitroxide cleavable conjugates (37–43, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Hybrid indomethacin and benzyl salicylate-nitroxide cleavable conjugates.

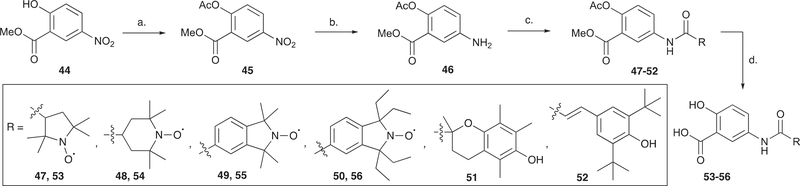

In addition to the salicylate and indomethacin hybrids, a number of stable nitroxide compounds were incorporated into the 5-ASA framework as depicted in Scheme 5. Methyl 2-hydroxy-5-nitrobenzoate 44 was first protected with an acetyl group to furnish the nitro-diester 45 which was reduced to the amine derivative 46 under Pd/C hydrogenolysis. The amino ester 46 was then coupled to various carboxylic acid nitroxides (16, 19, 21 and 22) to give the amide derivatives (47–50). A mild basic hydrolysis of the amide-diesters (47–50) afforded the amide salicylates (53–56) in high yields (83–91%). To compare the therapeutic efficacy of the novel nitroxides conjugates to known pharmacophores, the 5-ASA conjugates of known anti-oxidants Trolox and cinnamic acid were also prepared (51 and 52).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of amide-linked nitroxide-5-ASA conjugatesa.

In addition to the 5-ASA amide conjugates, the ethylaminolinked nitroxide-5-ASA non-cleavable conjugate 63 was also synthesized (Scheme 6). The bromomethoxyamine precursor 57 was generated in two steps from bromoamine 6 following literature procedures [33]. The methyl ester 58 was obtained following an oxidative decarboxylative coupling protocol that involved refluxing a degassed reaction mixture of bromomethoxyamine 57 and potassium malonate in the presence of catalytic amounts of BINAP, and DMAP [34]. Methyl ester 58 was readily converted to the nitroxide 59 using mCPBA and the carboxylic acid derivative 23 was obtained in almost quantitative yield following basic hydrolysis of methyl ester 59. EDC-mediated coupling of carboxylic acid nitroxide 23 with the amino ester 46 furnished the amide derivative 60. Subsequent hydrolysis of compound 60 afforded the amide-linked salicylic acid nitroxide conjugate 61. Selective reduction of the amide group of 60 to furnish the corresponding amine 62 was achieved using a pre-formed solution of sodium acyloxyborohydride in refluxing dioxane. Final hydrolysis of 62 afforded the amine-linked salicylic acid nitroxide 63 in 72% yield.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of amine-linked nitroxide-5-ASA conjugatea.

2.2. Biological evaluation

A range of novel nitroxide-NSAID hybrids were investigated for their in vitro anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects. The efficacy of two lead compounds (27 and 39) on ROS generation was tested on three different ROS-sensitive cell types, two Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, A549 and NIH-H1299, as well as a mouse photoreceptor cone cell line (661 W retinal photoreceptor cells). The A549 NSCLC cells are a type of epithelial lung cancer that is relatively insensitive to chemotherapy and radiation therapy, and which accounts for over 80% of lung cancers [35]. The 661 W photoreceptor cells are also highly valuable for investigating ROS injury, in this case, derived from the high flux of oxygen in the retina that is linked to dysfunction and eventual loss of vision.

2.2.1. In vitro anti-oxidant action

The anti-oxidant capacity of the nitroxide-NSAID conjugates was determined by evaluating their ability to scavenge ROS generated in A549 NSCLC cells via the addition of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Noting the limitations of the methodology, an indication of the H2O2-induced ROS produced by A549 cells was obtained through fluorescence generated from 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) [36]. Since the radical scavenging effect of the new hybrid compounds would be expected to arise primarily from the nitroxide moiety, the studies were carried out by comparing Tempol, probably the most widely studied anti-oxidant nitroxide, to the structurally-analogous hybrid compound 27 (Table 1). Both Tempol and the conjugate drug 27 lowered the increase in ROS caused by H2O2, but had no effect on basal ROS levels. Notably, only 10 μM of the hybrid compound 27 was needed to generate similar ROS scavenging delivered by Tempol used at 10-times the concentration (100 μM).

Table 1.

ROS scavenging action of nitroxide-NSAID-conjugates on NSCLC A549 cells.

| Compound | Concentration (μM) | Relative fluorescence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 100 ± 5aa | |

| H2O2 | 194 ± 13** | |

| H2O2 + 27 | 10 | 144 ± 12*a |

| H2O2 + Tempol | 100 | 155 ± 15*a |

| Tempol | 100 | 103 ± 6aa |

| 27 | 10 | 98 ± 4aa |

The mean value ± S.D. of 8 determinations is indicated

, p < 0.05

p < 0.01 relative to control

p < 0.05

p < 0.01 using the Student’s t-test (relative to H2O2). This experiment is representative of 2 others.

2.2.2. In vitro anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer effects

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) was exploited as the target protein for evaluating the anti-inflammatory capacity of the novel nitroxide-NSAID hybrids. As a common NSCLC drug target, the EGFR signaling pathway is responsible for COX-2 prostaglandin (PGs) production [37–40]. The COX-induced prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) produced by A549 cells was quantified using the enzymelinked immunosorbent assay. As shown in Table 2, the ester-linked conjugates (27, 34, 41 and 43) displayed strong inhibition of the COX-induced PGE2 production. In contrast, the amide-linked conjugates (28, 29 and 39) showed moderate inhibitory action.

Table 2.

Inhibitory effects of nitroxide-NSAID conjugates on COX-induced PGE2 in NSCLC A549 cells.

| Compound | Concentration (μM) | PGE2, pg.mL |

|---|---|---|

| None | 57 ± 4 | |

| 4 | 30 | 50 ± 5 |

| 5 | 30 | 52 ± 5 |

| 27 | 30 | 31 ± 4* |

| 28 | 30 | 54 ± 6 |

| 29 | 30 | 45 ± 9 |

| 34 | 30 | 34 ± 6* |

| 39 | 30 | 58 ± 3 |

| 41 | 30 | 23 ± 5* |

| 42 | 30 | 21 ± 6* |

The mean value ± S.D. or 3 determinations each repeated in duplicate is indicated using A549 cells

p < 0.05

p < 0.01, using the Student’s t-test

Further COX inhibition experiments were conducted at lower concentrations (4 μM) of selected conjugates (27 and 28) along with Tempol and the parent aspirin (Table 3). The ester-linked conjugate 27 significantly inhibited PGE2 productions even at the lower concentration of 4 μM. The amide-linked conjugate 28 on the other hand showed only moderate inhibition at 4 μM. The most interesting result was the inhibitory action of the conjugates in comparison to the aspirin parent. Notably, compound 27 was approximately an order of magnitude more effective at inhibiting COX-induced PGE2 production in NSCLC cells than aspirin.

Table 3.

Comparison of individual components with nitroxide-NSAID conjugates on inhibiting of COX-induced PGE2 in NSCLC A549 cells.

| Compound | Concentration (μM) | PGE2, pg.mL |

|---|---|---|

| None | 126 ± 17 | |

| Aspirin | 90 | 79 ± 11 |

| Tempol | 90 | 105 ±11 |

| Aspirin + Tempol | 90 | 75 ± 14* |

| 27 | 4 | 87 ± 9* |

| 28 | 4 | 99 + 13 |

The mean value ± S.D. or 3 determinations each repeated in duplicate is indicated using A549 cells

p < 0.05

p < 0.01, using the Student’s t-test

The nitroxide-NSAID conjugates were further tested for their inhibitory action on NSCLC proliferation using the MMT assay. The ester-linked conjugates (27, 41 and 42) inhibited A549 cell proliferation with IC50 values in the range of 118–151 μM (Table 4). In contrast, their amide-linked counterparts (28, 29 and 37) displayed moderate cell inhibitory potency with IC50 values > 300 μM).

Table 4.

Inhibitory effects of nitroxide-NSAID conjugates on NSCLC A549 cell growth.

| Compound | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| 27 | 130 + 23 |

| 28 | > 300 |

| 29 | > 300 |

| 37 | 151 + 8 |

| 41 | 121 + 12 |

| 42 | 118 + 16 |

The mean value ± S.D. of 3 experiments each repeated in duplicate is shown using NSCLC A549 cells

p < 0.05, using the Student’s t-test.

Further cell growth inhibitory studies using NCI-H1299 cells were conducted with compound 27, along with Tempol and aspirin, at different concentrations (Table 5). At a concentration of 180 μM, compound 27 displayed strong inhibitory capacity against the growth of these cells. However, no significant inhibition was observed for compound 27 at a lower concentration (18 μM). In contrast, Tempol at 90 μM or 900 μM concentrations had little effect on NCI-H1299 proliferation. Only a moderate inhibitory action was observed for aspirin. However, this was only observed at higher aspirin concentrations (900 μM).

Table 5.

Inhibitory effects of nitroxide-NSAID conjugates on NCI-H1299 cell growth.

| Compound | Concentration (μM) | % Growth |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 90 | 103 ± 4 |

| Aspirin | 900 | 49 ± 2* |

| Tempol | 90 | 100 ± 4 |

| Tempol | 900 | 98 ± 5 |

| Aspirin + Tempol | 90 | 102 ± 6 |

| Aspirin + Tempol | 900 | 53 ± 4* |

| 27 | 18 | 97 ± 3 |

| 27 | 180 | 13 ± 1* |

The mean value ± S.D. of 3 experiments each repeated in duplicate is shown using NCI-H1299 cells

p < 0.05, using the Student’s t-test.

2.2.3. Cell culture of retinal cells

The 661 W retinal photoreceptor cell line was established in T75 tissue culture flasks in Dulbecco Modified-Eagles Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM l-glutamine and 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were harvested for experimental use upon reaching 80−85% confluence.

The prospects for therapeutic intervention to reduce or prevent cellular damage induced by oxidative stress was evaluated by a fluorescence-based response for cell populations using flow cytometry and exploiting a fluorescent probe that responds to changes in the cellular redox environment under both pro- and anti-oxidant conditions [41]. Flow cytometry provides a convenient and rapid screening method to measure the biological efficacy of novel anti-oxidant compounds and we have previously exploited it to monitor the overall changes to the cellular redox environment of cells with varying metabolic activity [42].

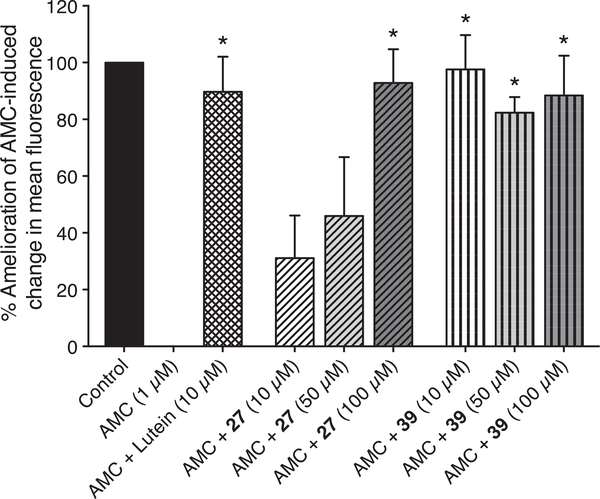

Two representative dual-acting anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant compounds, the aspirin-nitroxide hybrid 27 and the indomethacin-nitroxide 39, were tested for their efficacy for alleviating antimycin (AMC) derived fluorescence response with lutein used as a comparison. Lutein is an effective, widely adopted anti-oxidant and free radical scavenger that displays anti-inflammatory properties, and affords cellular protection, particularly to retinal neurons, from oxidative injury [43,44].

Stimulation of mitochondrial ROS production in 661 W retinal cells with AMC (1 μM) resulted in a 50% reduction in mean fluorescence intensity using a fluorescent probe that responds to cellular oxidative status [40]. Anti-oxidant data were normalized to the maximal effect of AMC and expressed as the % amelioration of the AMC-induced change in mean fluorescence i.e. (100*(AMC+antioxidant − AMC)/(Control − AMC)). Lutein significantly reduced the effects of AMC on probe fluorescence by 89.7 ± 12.4%; p = 0.0002 (NB. Larger % represents better response). The indomethacin-nitroxide hybrid 39 significantly ameliorated the effects of AMC on probe fluorescence at each concentration tested; (97.6 ± 12.1% for 10 μM; p = 0.0003; 82.3 ± 5.5% for 50 μM; p = 0.0015; 88.4 ± 14.0% for 100 μM; p = 0.0007), while compound 27 also produced a dose dependent effect, it significantly lowered the impact of AMC only at 100 μM (31.1 ± 15.0% for 10 μM; p = 0.4318; 46.0 ± 20.7% for 50 μM; p = 0.1099; 92.8 ± 11.9% for 100 μM; p = 0.0004) (Fig. 4). Notably the indomethacin-nitroxide hybrid 39 provided greater protection against AMC at 10 μM, than that provided by the same concentration of lutein, suggesting, especially at lower concentrations, this hybrid compound may provide greater protection against oxidative stress than current state-of-the-art anti-oxidants.

Fig. 4.

Hybrid indomethacin and aspirin nitroxides and their impact on antimycin-induced mitochondrial ROS productiona.

3. Conclusion

A pharmacophore hybridization strategy was successfully employed to design and synthesise a series of 30 novel potential dual-acting (anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory) nitroxide-NSAID conjugates. Selected novel hybrids were evaluated for their anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects on A549 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer cells. Several nitroxide conjugates displayed significant antioxidant effects by inhibiting ROS generated by A549 cells. While the ester-linked conjugates inhibited of the COX enzyme, the amide-linked counterparts delivered only moderate inhibition. Notably, the nitroxide conjugate 27 provides better inhibition of the COX enzyme than parent aspirin. Another nitroxide hybrid (39), a structural combination with the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin, significantly ameliorated the effects of oxidative stress on 661 W retinal neurons at efficacies greater or equal to the recognized anti-oxidant Lutein. Importantly, the hybrid conjugates also possess promising anticancer effects in inhibiting the proliferation of NIH-H1299 NSCLC cells. This work demonstrates that merged/cleavable/non-cleavable hybrid agents can deliver enhanced therapeutic efficacy with multiple modes of action over the individual parent species.

4. Experimental section

4.1. General procedures

All air-sensitive reactions were carried out under ultra-high pure argon. Diethyl ether and toluene were dried by storing with sodium wire. All other solvents were dried using the Pure Solv Micro 4 L solvent purification system (PSM-13–672). Solvents used for extractions and silica gel column chromatography were AR grade. Crystalline K4[Fe(CN)6]·3H2O was ground to a fine powder and then dried at 80 °C at 0.5 Torr for 10 h. All other reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded with Bruker Avance 600 MHz, 400 MHz or Varian 400 MHz spectrometers and referenced to the relevant solvent peak. HPLC was performed with a HP Agilent 1100 HPLC instrument. HRMS was performed with an Agilent accurate Quadrupole Time of Flight Mass Spectrometer Liquid Chromatography-Mass Chromatography (QTOF LC-MS) mass spectrometer. Formulations were calculated by elemental analysis using a Mass Lynx 4.0 or Micromass Opus 3.6 instrument. FTIR spectra were recorded with a Nicolet 870 Nexus Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer equipped with a DTGS TEC detector and an ATR objective. All melting points were measured on a Buchi Melting Point M − 565 apparatus. The EPR spectra were recorded on a Magnettech MiniScope MS400 spectrometer. Whereas the pyrrolidine and piperidines nitroxides (16−19) are commercially available, the isoindoline nitroxides (20−22) were synthesized by following previously published literature procedures [45–50]. An earlier report on the synthesis of compound 28 provided only limited characterisation data [51] and we have previously described the synthesis of 27 and 37 [52]. Others have also reported further data on these compounds [53,54].

4.2. 5-Methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 7

CuI (56.25 mg, 0.2 equiv.) was added to a solution of 5-bromo1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 6 (500 mg, 1.967 mmol, 1 equiv.) in DMF (3 mL) and NaOMe (5 M in MeOH, 12 mL) under Ar. The reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 15 h and allowed to return to RT. It was then diluted with H2O and extracted with Et2O. The combined Et2O (4 × 40 mL) extracts were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting solid residue was purified by silica column chromatography (CHCl3/EtOH, 10:0.5) to give 5-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 7 as a pale white semi-solid (343.3 mg, 85%). Mp. 57−58 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.45 (s, 6 H, CH3), 1.47 (s, 6 H, CH3), 3.87 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 6.65−7.39 (m, 3 H, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 31.9 (C-CH3), 32.0 (C-CH3), 55.4 (OCH3), 62.5 (CCH3), 62.8 (CCH3), 112.8 (Ar-C), 123.3 (Ar-C), 125.7 (Ar-C), 140.0 (Ar-C), 147.2 (Ar-C), 157.4 (Ar-C). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C13H20NO [M + H]+ 206.1539; found 206.1574. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3415 (s, N-H), 1154 (s, C-N), 1042 (C-O) cm−1.

4.3. 2,5-Dibromo-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 8

A solution of 5-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 7 (1.50 g, 731 μmol, 1 equiv.) in DCM (25 mL) under Ar was cooled to 0 °C. A solution of bromine (942 μL, 1.83 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) in DCM (10 mL) was added dropwise followed by addition of anhydrous aluminium trichloride (3.48 g, 2.56 mmol, 3.5 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at 0 °C, then poured onto ice (40 mL) and stirred vigorously for further 20 min. The solution was then basified to or above pH 12 with aqueous NaOH (10 M) solution and stirred for 10 min. The mixture was extracted with DCM (4 × 50 mL), the combined DCM extracts were washed with brine (50 mL) and the solvent removed under reduced pressure to give light yellow oil. The oil was triturated with methanol to give 2,5-dibromo-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 8 as a yellow solid (2.307 g, 87%). Mp. 97−98 °C. HPLC purity (93%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.41 (s, 6 H, CH3), 1.44 (s, 6 H, CH3), 3.91 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 6.66 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.3 (s, 1 H, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 28.1 (C-CH3), 28.3 (C-CH3), 56.5 (OCH3), 69.2 (C-CH3), 69.7 (C-CH3), 105.4 (Ar-C), 110.6 (Ar-C), 126.6 (Ar-C), 137.7 (Ar-C), 144.8 (Ar-C), 155.3 (Ar-C). ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3000 (m, Ar C-H), 1232 (s, C-N), 1034 (C-O) cm−1.

4.4. 5-Bromo-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 9

To a suspension of 2,5-dibromo-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 8 (900 mg, 2.479 mmol, 1 equiv.) and NaHCO3 (208 mg, 2.479 mmol, 1 equiv.) in MeOH/DCM (10:5 mL) was added dropwise aqueous H2O2 (30%) until the observed effervescence ceased. The reaction mixture was stirred for 5 min followed by the addition of NaOH (5 M). The resulting solution was extracted with DCM (4 × 40 mL) and the combined DCM extracts were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give 5-bromo-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 9 as a beige solid (688 mg, 98%). Mp. 59−60 °C. HPLC purity (>99%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 1.42 (s, 6 H, CH3), 1.45 (s, 6 H, CH3), 3.91 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 6.62 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.26 (s, 1 H, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 31.8 (C-CH3), 32.0 (C-CH3), 56.4 (OCH3), 62.4 (C-CH3), 62.8 (C-CH3), 105.1 (Ar-C), 110.5 (Ar-C), 126.2 (Ar-C), 142.3 (Ar-C), 149.6 (Ar-C), 155.3 (Ar-C). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C13H19BrNO [M + H]+ 284.0645; found 284.0723. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3307 (w, N-H), 2961 (m, Ar C-H), 1307 (s, C-N), 1038 (C-O) 699 (s, C-Br) cm−1.

4.5. 5-Cyano-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 10

A Schlenk vessel that contained a mixture of 5-bromo-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 9 (2.76 g, 9.72 mmol, 1 equiv.), K4[Fe(CN)6] (837 mg, 1.94 mmol, 0.2 equiv.), CuI (223 mg, 1.17 mmol, 0.12 equiv.) N-butylimidazole (2.5 mL, 19.45 mmol, 2 equiv.) in o-xylene (20 mL) was degassed and then heated at refluxed at 180 °C for 3 d. The resulting mixture was allowed to return to RT before it was diluted with water and then extracted with Et2O (4 × 60 mL). The combined Et2O extracts were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc) and recrystallized from cyclohexane to give 5-cyano-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 10 as an off-white solid (1.75 g, 78%). Mp. 138−139 °C. HPLC purity (>99%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.42 (s, 6 H, CH3), 1.45 (s, 6 H, CH3), 1.73 (s, 1 H, N-H), 3.94 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 6.66 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.27 (s, 1 H, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 31.6 (C-CH3), 31.9 (C CH3), 56.2 (OCH3), 62.4 (C-CH3), 63.2 (C-CH3), 100.8 (C N), 104.5 (Ar-C), 117.0 (Ar-C), 126.8 (Ar-C), 141.4 (Ar-C), 156.2 (Ar-C), 161.5 (Ar-C). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C14H19N2O [M + H]+ 231.1492; found 231.1560. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3326 (w, N-H), 2968 (m, Ar C-H), 2221 (m, C≡N), 1155 (s, C-N), 1042 (C-O) cm−1.

4.6. 5-Cyano-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 11

m-Chloroperoxybenzoic acid (1.78 g, 6.43 mmol, 1.3 equiv.) was added to a solution of 5-cyano-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 10 (1.14 g, 4.95 mmol, 1 equiv.) in DCM (100 mL) at 0 °C. The cooling bath was removed after 30 min and the reaction stirred at RT for a further 1.5 h. The DCM layer was washed with HCl (2 M), NaOH (5 M), and brine solutions (50 mL) and before being dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The DCM was removed under reduced pressure and the solid residue obtained was recrystallized from EtOH to give bright yellow needles of 5-cyano-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 11 (1.09 g, 90%). Mp. 200−201 °C. HPLC purity (>99%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + Na]+ 268.1182; found 268.1230. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3048 (w, Ar C-H), 2231 (m, C=N), 1472 (N-O), 1161 (s, C-N), 1041 (C-O) cm−1; EPR: g = 2.0009, aN = 1.81 mT.

4.7. 5-Carboxy-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 12

A suspension of 5-cyano-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 11 (760 mg, 3.1 mmol, 1.00 equiv.) in NaOH (5 M, 10 mL)/EtOH (5 mL) was heated at reflux for 16 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to RT, then diluted with H2O and washed with Et2O (2 × 40 mL). The Et2O layer was discarded. The aqueous layer was cooled in ice bath and acidified with HCl (2 M) before it was extracted with Et2O (50 mL x 4). The combined Et2O extracts were washed with brine (50 mL) and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was recrystallized from H2O/EtOH to give 5-carboxy-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 12 as yellow solid (729 mg, 89%). Mp. 244−245 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>99%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + Na]+ 287.1128; found 287.1714. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3400–2450 (m, br, OH), 2973 (m, Ar C-H), 1675 (s, C=O), 1360 (s, C-N), 1202 (C-O) cm−1; EPR: g = 2.0009, aN = 1.83 mT.

4.8. 5-Carboxy-6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 4 from 12

BBr3 (1.9 mL, 1.89 mmol, 1 M solution in DCM, 2.5 equiv.) was added dropwise to a solution of 5-carboxy-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 12 (200 mg, 757 μmol, 1 equiv.) in DCM (15 mL) at −78 °C under Ar atmosphere. The reaction was allowed to return to RT and left to stir for 18 h. H2O was added to the resulting mixture to quench excess any BBr3 reagent. The crude product was extracted with EtOAc (50 mL x 4) and the combined EtOAc extracts were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (DCM/MeOH, 6:0.4) and recrystallized from H2O/EtOH to give 5-carboxy6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 4 as yellow crystals (76 mg, 40%). Mp. 207−208 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>99%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + 2H]+ 252.1230; found 252.1186. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3400–2500 (m, br, OH), 2972 (m, Ar C-H), 1674 (s, C=O), 1201 (C-O) cm−1; EPR: g = 2.0017, aN = 1.80 mT.

4.9. 2-Acetoxy-5-carboxy-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 14

A reaction mixture of 5-carboxy-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 12 (660 mg, 2.5 mmol, 1 equiv.) and Pd/C (66 mg, 10%, 62.5 μmol, 0.025 equiv.) in THF (15 mL) was flushed with Ar for 10 min. Then, a balloon of H2 was connected and the reaction mixture stirred for 15 min and then cooled in ice/H2O bath. TEA (697 μL, 5 mmol, 2 equiv.) and AcCl (355 μL, 5 mmol, 2 equiv.) were added dropwise and the resulting mixture was stirred for 30 min. The cooling bath was removed and stirring was continued for a further 1 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was stirred in aqueous MeOH (10 mL, 2 mL H2O) for 1 h, then diluted with H2O, and extracted with EtOAc (4 × 50 mL). The EtOAc extracts were washed with brine (40 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to give 2-acetoxy-5-carboxy-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 14 as a clear solid (738 mg, 96%). Although compound 14 was pure enough to be used subsequent step, it was further purified by silica gel flash column chromatography (EtOAc/CHCl3, 2:1) and recrystallized from cyclohexane. Mp. 149−150 °C. HPLC purity (>99%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.42 (d, 6 H, CH3), 1.48 (d, 6 H, CH3), 2.2 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 4.1 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 6.78 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.98 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 10.81 (s, br, 1 H, CO2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 19.2 (CO-CH3) 25.0, 25.2 (C-CH3), 28.6, 28.8 (C-CH3), 57.0 (OCH3), 67.9 (C-CH3), 68.4 (C-CH3), 105.0 (Ar-C), 117.4 (Ar-C), 127.5 (Ar-C), 138.1 (Ar-C), 151.7 (Ar-C), 158.3 (Ar-C), 165.2 (CO2H), 171.2 (C=OCH3). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C16H21NNaO5 [M + Na]+ 330.1312; found 330.1401. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3267 (m, br, OH), 2973 (m, Ar C-H), 1772 (s, Ac C=O), 1709 (carboxylic acid C=O) 1194 (C-O) cm−1.

4.10. 2-Acetoxy-5-carboxy-6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 15

BBr3 (1.4 mL, 1.4 mmol, 1 M solution in DCM, 2.5 equiv.) was added dropwise to a solution of 2-acetoxy-5-carboxy-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 14 (170 mg, 559 μmol, 1 equiv.) in DCM (10 mL) at −78 °C under an Ar atmosphere. The reaction was allowed to return to RT and left to stir for 18 h. H2O was added to the resulting mixture to quench any excess BBr3 reagent. The crude product was extracted with EtOAc (4 × 20 mL) and the combined EtOAc extracts were washed with brine (20 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (DCM/MeOH, 6:0.4) and recrystallized from cyclohexane to give 2-acetoxy-5-carboxy-6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 15 as a white solid (153 mg, 85%). Mp. 168−169 °C. HPLC purity (>98%).1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.4 (s, 6 H, CH3), 1.48 (s, 6 H, CH3), 2.2 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 6.77 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.64 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 10.6 (s, br, 1 H, CO2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 19.2 (CO-CH3) 25, 25.2 (C-CH3), 28.6, 28.8 (C-CH3), 57.0 (OCH3), 67.9 (C-CH3), 68.4 (C-CH3), 105.0 (Ar-C), 117.4 (Ar-C), 127.5 (Ar-C), 138.07 (Ar-C), 151.7 (Ar-C), 158.3 (Ar-C), 165.2 (CO2H), 171.2 (C=OCH3). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C15H20NO5 [M + H]+ 294.1336; found 294.2269. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3095 (m, br, OH), 2973 (m, Ar C-H), 1737 (s, Ac C=O), 1677 (carboxylic acid C=O), 1160 (C-O) cm−1.

4.11. 5-Carboxy-6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 4 from 15

A suspension of 2-acetoxy-5-carboxy-6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 15 (136 mg, 464 μol, 1 equiv.) in H O/MeOH (2 mL/2 mL) was cooled to 0 °C. LiOH (56 mg, 2.3 mmol, 5 equiv.) was added and the reaction mixture stirred overnight while allowed to warm to RT. The resulting solution was washed with Et2O and the Et2O layer discarded. The aqueous layer was cooled in ice bath, acidified with HCl (2 M) and then extracted with Et2O (4 × 30 mL). The combined Et2O extracts were stirred over PbO2 (28 mg, 116 μmol, 0.25 equiv.) for 20 min, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was recrystallized from H2O/EtOH to give 5-carboxy-6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 4 as yellow crystals (107 mg, 92%). Mp. 207−208 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>99%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + 2H]+ 252.1230; found 252.1186. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3400–2500 (m, br, OH), 2972 (m, Ar C-H), 1674 (s, C=O), 1201 (C-O) cm−1; EPR: g = 2.0017, aN = 1.80 mT.

4.12. 6-Acetoxy-5-carboxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 5

A solution of 5-carboxy-6-hydroxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 4 (89 mg, 354.4 mmol, 1 equiv.) in THF under Ar was cooled to 0 °C. TEA (99 μL, 709 μmol, 2 equiv.) and AcCl (50.4 mL, 709 μmol, 2 equiv.) were added dropwise and the resulting mixture stirred for 3 h while allowing to return to RT. Water was added to the reaction mixture and it was then extracted with DCM (3 × 30 mL). The DCM extracts were washed with HCl (1 M, 15 mL), brine (20 mL) and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The combined DCM was removed under reduced pressure and the crude residue obtained was recrystallized from H2O/EtOH to give 6-acetoxy-5-carboxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 5 as a yellow solid (94 mg, 91%). Mp. 206−207 °C. HPLC purity (>99%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 293.1258; found 293.1221. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3400–2600 (m, br, OH), 2972 (m, Ar C-H), 1765 (s, Ac C=O), 1695 (carboxylic acid C=O) 1184 (C-O) cm−1; EPR: g = 2.0016, aN = 1.80 mT.

4.13. Benzyl 2-hydroxybenzoate 25

NaHCO3 (1.46 g, 17.4 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) was added to a solution salicylic acid 1 (2 g, 14.5 mmol, 1 equiv.) in DMF (20 mL) and the resulting mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 10 min. The temperature was reduced to 50 °C followed by the addition of benzylbromide (1.81 mL, 15.2 mmol, 1.05 equiv.). The reaction mixture was stirred for 4 h and then allowed to cool to RT. H2O (50 mL) was added and the crude product was extracted with EtOAc (4 × 60 mL). The combined EtOAc extracts were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. Purification of the crude residue by silica gel chromatography (Hexane/EtOAc, 5:0.2) afforded compound 25 as clear oil (3.11 g, 94%). HPLC purity (>99%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 5.42 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.9 (m, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.4 (m, 6 H, Ar-H), 7.91 (q, 1 H, Ar-H), 10.78 (s, 1 H, O-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 67.0 (CH2), 112.4 (Ar-C), 117.6 (Ar-C), 119.2 (Ar-C), 128.3 (Ar-C), 128.6 (Ar-C), 128.7 (Ar-C), 130.0 (Ar-C), 135.3 (Ar-C), 135.8 (Ar-C), 161.8 (Ar-C), 170.0 (C=O). ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3188 (m, br, O-H), 3000 (m, Ar C-H), 1670 (s, C O), 1086 and 1133 (s, C-O) cm−1.

4.14. General procedure for the synthesis of salicylic acid derivatives 27–29

A solution of aspirin 3 (150 mg, 833 mmol, 1 equiv.), appropriate nitroxide 17, 18 or 20 (1 mmol, 1.2 equiv.), EDC (191.5 mg, 1 mmol, 1.2 equiv.), and DMAP (13 mg, 104 mmol, 0.125 equiv.) in DCM (10 mL) was stirred under Ar for 1 d. The resulting reaction mixture was diluted (DCM, 150 mL), washed HCl (2 M, 30 mL) and brine (30 mL) solutions, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3) and then recrystallization from cyclohexane/EtOAc (except 28) to give the corresponding salicylate-nitroxide.

4.15. 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-4-yl 2-acetoxybenzoate 27

Reddish brown solid (251 mg, 90%). Mp. 52−53 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 335.1727; found 335.1688. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 2977 (w, ArC-H), 1724 (s, C=O), 1255 (s, C-O) cm−1; EPR: g = 2.0012, aN = 1.97 mT.

4.16. 2-((2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-4-yl)carbamoyl) phenyl acetate 28

Reddish brown solid (153 mg, 55%). Mp. 50−52 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 334.1887; found 334.1850. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3314 (m, N-H), 2976 (w, ArC-H), 1640 (s, C=O), 1546 (s, C=O), 1229 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0012, aN = 1.96 mT.

4.17. 2-((1,1,3,3-Tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-yl)carbamoyl) phenyl acetate 29

Yellow solid (162 mg, 53%). Mp. 101−102 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 368.1731; found 368.1689. ATR-FTIR: υmax 3340 (m, N-H), 2971 (w, ArC-H), 1681 (s, C O), 1543 (s, C O), 1255 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0010, aN = 1.80 mT.

4.18. General procedure for the synthesis of formyl-nitroxides 31–33

Following similar procedure as for 27−29, compounds 31−33 were obtained from 30 (1.31 mmol, 1.05 equiv.) and the appropriate carboxy-nitroxide 16, 19 and 21 (1.25 mmol, 1 equiv.).

4.19. 2-Formylphenyl 2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidin-1-yloxyl-3-carboxylate 31

Yellow crystalline solid (319 mg, 88%). HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 7.19 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.47 (d, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.7 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.9 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 10.1 (s, br, HC=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 291.1465; found 291.1428. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3350–2400 (m, br, O-H), 1734 (s, C=O), 1688 (s, C=O), 1288 (s, C-N), 1196 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN = 1.84 mT.

4.20. 2-Formylphenyl 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-4-carboxylate 32

Light reddish-brown, fluffy crystals (327 mg, 86%). Mp. 94−95 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 7.18 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.47 (d, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.69 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.91 (d, br, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H), 10.1 (s, br, HC=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + Na]+ 327.1441; found 327.1442. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3079 (m, ArC-H), 1745 (s, C=O), 1699 (s, C=O), 1230 (s, C-N), 1154 (s, C-O) cm−1′ g = 2.0011, aN = 1.97 mT.

4.21. 2-Formylphenyl 1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-carboxylate 33

Yellow crystalline solid (372 mg, 88%). Mp. 151−152 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 7.34 (d, br, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.49 (t, br, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.72 (t, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.98 (d, br, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H), 10.21 (s, br, HC=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + Na]+ 361.1285; found 361.1292. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 2978 (m, ArC-H), 1749 (s, C=O), 1708 (s, C=O), 1234 (s, C-N), 1197 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0010, aN = 1.83 mT.

4.22. General procedure for the synthesis of carboxylic acids 34–36

KH2PO4 (48.3 mg, 355 mmol, 2 equiv. in 0.5 mL H2O) and H2O2 (30 μL, 355 μmol, 1.5 equiv. 30% in H2O) were added to a solution of appropriate formyl nitroxide 31−33 (177.3 μmol, 1 equiv.) in MeCN (5 mL) at 0 °C. NaClO2 (40.3 mg, 356 μmol, 2 equiv. in 0.5 mL H2O) was then added dropwise and the resulting solution stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and the aqueous layer extracted with DCM (3 × 30 mL). The DCM extract was washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc/0.01%AcOH) and then recrystallization from H2O/MeOH to give the corresponding carboxylic acid nitroxide (34−36).

4.23. 2-((2,2,5,5-Tetramethylpyrrolidin-1-yloxyl-3-carbonyl)oxy) benzoic acid 34

Yellow crystalline solid (319 mg, 88%). Mp. 161−162 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 7.18 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.7.4 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.66 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.1 (d, br, 1 H, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 307.1414; found 307.1377. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3500–2400 (m, br, O-H), 2976 (w, ArC-H), 1766 (s, C=O), 1713 (s, C=O), 1204 (s, C-N), 1126 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN = 1.84 mT.

4.24. 2-((2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-4-carbonyl)oxy) benzoic acid 35

Light reddish-brown, fluffy crystals (327 mg, 86%). Mp. 149 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 7.17 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.4 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.67 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.1 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 321.1571; found 321.1532. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3500–2400 (m, br, O-H), 1755 (s, C=O), 1716 (s, C=O), 1241 (s, C-N), 1145 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.009, aN = 1.84 mT.

4.25. 2-((1,3,3-Tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-carbonyl)oxy) benzoic acid 36

Yellow crystalline solid (372 mg, 88%). Mp. 193 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 7.27 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.41 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.68 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.12 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = (30); calcd. for [M + 2H]+ 356.1492; found 356.1409. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3350–2400 (m, br, O-H), 1734 (s, C=O), 1688 (s, C=O), 1288 (s, C-N), 1196 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN 1.80 mT.

Indomethacin-nitroxide derivatives 37−39 were obtained from benzyl indomethacin (453 μmol, 1 equiv.) and the appropriate carboxy-nitroxide 17−19 (498 μmol, 1.1 equiv.) following similar procedure as for 27−29 (silica gel column chromatography: Hexane/EtOAc, 3:1).

4.26. 2-(1-(4-Chlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)N-(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-yl)acetate 37

Pale orange solid (97%). Mp. 71−72 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 2.44 (br, s, 3 H, CH3), 3.70 (br, s, 2 H, CH2), 3.86 (br, s, 3 H, OCH3), 6.69 (br, d, 1 H, J = 7.8 Hz, Ar-H), 6.87 (br, d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.99 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.49 (br, d, 2 H, J = 6 Hz, Ar-H), 7.67 (br, d, 2 H, J = 6.6 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 21.0 (CH3), 30.9 (CH2), 52.2 (OCH3), 117.3 (Ar-C), 117.31 (Ar-C), 120.0 (Ar-C), 123.3 (Ar-C), 124.4 (Ar-C), 142.5 (Ar-C), 144.3 (Ar-C), 165.1 (Ar-C), 170.4 (C=O), 207.0 (C=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 512.2073; found 512.1929. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 2973 (m, Ar C-H), 1732 (s, C=O), 1680 (C=O), 1314 (C-N), 1141 (C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0012, aN = 1.94 mT.

4.27. 2-(1-(4-Chlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-4-yl)acetamide 38

Reddish brown crystals (87%). Mp. 199−201 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 2.46 (br, s, 3 H, CH3), 3.7 (br, s, 2 H, CH2), 3.91 (br, s, 3 H, OCH3), 5.28 (br, s, 2 H, Ar-H), 6.69 (br, d, 2 H, Ar-H), 7.28 (br, s, 2 H, Ar-), 7.6 (br, d, 2 H, Ar-). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + H]+ 511.2232; found 511.2199. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 1079 (w, N-H), 2973 (m, Ar C-H), 1636 (s, C=O), 1555 (C=O), 1350 (C-N), 1111 (C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0012, aN = 1.95 mT.

4.28. 2-(1-(4-Chlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-N-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-yl)acetamide 39

Light yellow crystals (92%). Mp. 164−166 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 2.49 (br, s, 3 H, CH3), 3.83 (br, s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.88 (br, s, 2 H, CH2), 6.74 (br, d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.9 (br, d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.96 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.51 (br, d, 2 H, J = 6 Hz, Ar-H), 7.7 (br, d, 2 H, J = 6 Hz, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C31H31ClN3NaO4● [M + Na]+ 567.1901; found 567.1942. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3299 (w, N-H), 2973 (m, Ar C-H), 1677 (s, C=O), 1599 (C=O), 1313 (C-N), 1223 (C-O) cm−1.; g = 2.0010, aN 1.79 mT.

Benzyl benzoate-nitroxide derivatives 40−43 were obtained from benzyl salicylate 25 (1.31 mmol, 1.05 equiv.) and the appropriate carboxy-nitroxide 12, 16, 19 and 21 (1.25 mmol, 1 equiv.) following similar procedure as for 27−29 (silica gel column chromatography: Hexane/EtOAc, 5:1).

4.29. 2-(Benzyloxy)carbonyl)phenyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidin1-yloxyl-3-carboxylate 40

Yellow oil (78%). HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 5.33 (s, br, 2 H, CH2), 6.9 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.4 (br, m, 7 H, Ar-H), 7.62 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.1 (d, br, 1 H, J = 7.6 Hz, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + Na]+ 419.1703; found 419.1699. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 2975 (w, ArC-H), 1761 (s, C=O), 1719 (s, C=O), 1251 (s, C-N), 1134 and 1075 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN = 1.84 mT.

4.30. 2-(Benzyloxycarbonyl)phenyl-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-4-carboxylate 41

Light reddish-brown fluffy solid (71%). Mp. 112−113 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 5.34 (s, br, 2 H, CH2), 7.1 (d, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.34 (br, m, 7 H, Ar-H), 7.6 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.1 (d, br, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + 2H]+ 412.2118; found 412.2126. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 2981 (w, ArC-H), 1745 (s, C=O), 1722 (s, C=O), 1257 (s, C-N), 1085 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0012, aN = 1.96 mT.

4.31. 2-(Benzyloxycarbonyl)phenyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-carboxylate 42

Yellow crystalline solid (72%). Mp. 97−98 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 5.25 (s, br, 2 H, CH2), 7.26 (s, br, 7 H, Ar-H), 7.42 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.66 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.17 (d, br, 1 H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + 2H]+ 444.1962; found 446.1980. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3038 (w, ArC-H), 1744 (s, C=O), 1705 (s, C=O), 1290 (s, C-N), 1192 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0010, aN = 1.80 mT.

4.32. 2-(Benzyloxycarbonyl)phenyl-6-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-carboxylate 43

Yellow solid (73%). Mp. 142−143 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 4.21 (br, s, 3 H, OCH3), 5.27 (s, br, 2 H, CH2), 7.27 (s, br, 2 H, Ar-H), 7.4 (br, m, 2 H, Ar-H), 7.62 (s, br, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.11 (d, br, 1 H, J = 7.8 Hz, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for [M + Na]+ 497.1809; found 497.01806. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 2979 (w, ArC-H), 1748 (s, C=O), 1718 (s, C=O), 1294 (s, C-N), 1192 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0010, aN = 1.79 mT.

4.33. Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-nitrobenzoate 45

A suspension of methyl 2-hydroxy-5-nitrobenzoate 44 (650 mg, 3.3 mmol, 1 equiv.) in THF (15 mL) under Ar was cooled to 0 °C. TEA (1.15 mL, 8.24 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) and AcCl (459 μL, 6.59 mmol, 2 equiv.) were added dropwise and the resulting mixture stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with H2O and the aqueous layer extracted with DCM (4 × 60 mL). The combined DCM extracts were washed brine (50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3/Hexane, 1:1) and then recrystallization from cyclohexane to give 45 as a white crystalline solid (91%). Mp. 75−76 °C (Lit.,47 73−74 °C). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 2.4 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 3.94 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 7.3 (d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 8.42 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.8 Hz, Ar-H), 8.9 (d, 1 H, J = 2.8 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 20.9 (C=OCH3), 52.8 (OCH3), 124.4 (Ar-C), 125.3 (Ar-C), 127.4 (Ar-C), 128.5 (Ar-C), 145.3 (Ar-C), 155.3 (Ar-C), 163.0 (C=O), 168.8 (C=O). ATR-FTIR: υmax 3102 (w, Ar C-H), 1759 (s, C O), 1727 (s, C O), 1529 (s, NO2), 1190 (s, C-O) cm−1.

4.34. Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-aminobenzoate 46

A solution of methyl 2-acetoxy-5-nitrobenzoate 45 (500 mg, 2.09 mmol, 1 equiv.) in EtOAc (20 mL) was hydrogenated at 50 psi over 10% Pd/C (50 mg) for 4 h in a Parr Hydrogenator. The resulting solution was filtered through Celite and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. Compound 46 was obtained as a light brown solid (394 mg, 90%) and was used in the next step without further purification. It could be recrystallized from cyclohexane/EtOAc. Mp. 107 °C (dec.), (Lit., [51], 103–105 °C). HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 2.31 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 3.74 (s, 2 H, NH2), 3.84 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 6.82 (dd, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz, 3 Hz, Ar-H), 6.88 (d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 7.28 (d, 1 H, J = 3 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 21.0 (C=OCH3), 52.2 (OCH3), 117.5 (Ar-C), 120.0 (Ar-C), 123.3 (Ar-C), 124.4 (Ar-C), 142.5 (Ar-C), 144.4 (Ar-C), 165.1 (C=O), 170.4 (C=O).

Methyl benzoate amide-nitroxides 47–52 were obtained from 46 (124 mg, 591 μmol, 1.1 equiv.) and the appropriate carboxylic acid 16, 19, 21, 23, cinnamic acid, and trolox (537 μmol, 1 equiv.) following similar procedure as for 27–29 (silica gel column chromatography: Hexane/EtOAc, 3:1).

4.35. Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-(2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidin-1-yloxyl-3-carboxamido)benzoate 47

Yellow solid (170 mg, 84%). Mp. 69–70 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 2.37 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 3.89 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 7.12 (br, s,1 H, Ar-H), 7.84 (br, s,1 H, Ar-H), 8.04 (br, s,1 H, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 378.1785; found 378.1744. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3330 (m, N-H), 2975 (m, ArC-H), 1768 (s, C=O), 1726 (s, C=O), 1540 (s, C=O), 1366 (s, C-N), 1183 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0008, aN = 1.83 mT.

4.36. Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-4-carboxamido)benzoate 48

Light reddish-brown solid (156 mg, 74%). Mp. 205 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 2.39 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 3.85 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 7.28 (br, dd, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.73 (br, d, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.14 (br, d, 1 H, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 414.1761; found 414.1760. ATR-FTIR: υmax = 3339 (m, N-H), 2977 (m, ArC-H), 1765, 1727 (s, C=O), 1691 (s, C=O), 1548 (s, C=O), 1176 (s, C-N), 1076 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0011, aN= 1.95 mT.

4.37. Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoinolin-2-yloxyl-5-carboxamido)benzoate 49

Yellow solid (190 mg, 83%). Mp.122–124 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 2.30 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 3.79 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 7.05 (br, s,1 H, Ar-H), 7.92 (br, s,1 H, Ar-H), 8.09 (br, s,1 H, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 21.3 (C=OCH3), 52.6 (OCH3), 123.52 (Ar-C), 124.7 (Ar-C), 135.5 (Ar-C), 147.2 (Ar-C), 164.8 (C=O), 170.1 (C=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 426.1785; found 426.1794. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3376 (m, N-H), 2980 (m, ArC-H), 1735, 1725 (s, C=O), 1664 (s, C=O), 1522 (s, C=O), 1271 (s, C-N), 1226 and 1189 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN= 1.80 mT.

4.38. Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-(1,1,3,3-tetraethylisoinolin-2-yloxyl-5-carboxamido)benzoate 50

Yellow solid (209.5 mg, 81%). Mp. 122–124 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 2.41 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 3.91 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 7.17 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.05 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 8.22 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 21.15 (C=OCH3), 52.49 (OCH3), 123.5 (Ar-C), 124 (Ar-C), 135.67 (Ar-C), 147.13 (Ar-C), 164.48 (C=O), 170.07 (C=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 482.2411; found 482.2407. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3369 (m, N-H), 2971 (m, ArC-H), 1743, 1719 (s, C=O), 1675 (s, C=O), 1534 (s, C=O), 1298 (s, C-N), 1219 and 1188 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0010, aN= 1.76 mT.

4.39. Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-(6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetraethylchromane-2-carboxamido)benzoate 51

Beige solid (206.3 mg, 87%). Mp. 123–124 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 1.58 (s, 3 H, CH3), 1.96 (m, 1 H, CH2), 2.21 (s, 3 H, CH3), 2.27 (s, 3 H, CH3), 2.33 (s, 3 H, CH3), 2.4 (s, 3 H, CH3), 2.42 (m, 1 H, CH2), 2.65 (m, 2 H, CH2), 3.86 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 4.32 (s, 1 H, NH), 7.05 (d, 1 H, J = 9 Hz, Ar-H), 7.75 (dd, 1 H, J = 9 Hz, 3 Hz, Ar-H), 8.08 (d,1 H, J = 3 Hz, Ar-H), 8.38 (s,1 H, OH).13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 11.3 (CH3), 12.1 (CH3), 12.3 (CH3), 20.4 (CH3), 20.9 (CH3), 24.2 (CH2), 29.5 (CH2), 52.4 (OCH3), 118.0 (Ar-C), 119.1 (Ar-C), 121.6 (Ar-C), 121.9 (Ar-C), 122.4 (Ar-C), 123.5 (Ar-C), 124.4 (Ar-C), 124.8 (Ar-C), 135.3 (Ar-C), 143.9 (Ar-C), 146.0 (Ar-C), 146.8 (Ar-C),164.5 (C=O),169.8 (C=O),172.9 (C=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C24H28NO7 [M + H]+ 442.1860; found 442.1799. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3478 (m, O-H), 3364 (m, N-H), 2929 (m, ArC-H), 1762, 1728 (s, C=O), 1671 (s, C=O), 1531 (s, C=O), 1184 and 1078 (s, C-O) cm−1.

4.40. Methyl (E)-2-acetoxy-5-(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)acrylamido)benzoate 52

Beige solid (233.5 mg, 93%). Mp. 181–182 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.48 (s, 18 H, 2× C(CH3)3), 2.36 (s, 3 H, CH3), 3.86 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 5.52 (s, 1 H, NH), 6.35 (d, 1 H, J = 15.6 Hz, CH=CH), 7.07 (d,1 H, J = 7.8 Hz, Ar-H), 7.41 (d, 3 H, Ar-H), 7.72 (d, 1 H, J = 15.6 Hz, CH=CH), 7.96 (d, 1 H, J = 7.8 Hz, Ar-H), 8.13 (s, 1 H, OH). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 21 (CH3), 30.12 (C(CH3)3), 34.36 (C(CH3)3), 52.3 (OCH3),116.83 (Ar-C), 122.65 (Ar-C), 123.2 (Ar-C), 124.3 (Ar-C), 125.16 (Ar-C), 125.41 (CH=CH), 125.8 (Ar-C), 136.28 (Ar-C), 136.38 (CH=CH), 144.02 (Ar-C), 146.5 (Ar-C), 156.07 (Ar-C), 164.5 (C=O), 164.57 (C=O), 170.23 (C=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C27H34NO6 [M + H]+ 468.2381; found 468.2379. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3623 (m, br, O-H), 3305 (m, br, N-H), 2954 (m, ArC-H), 1726 (s, C=O), 1621 (s, C=O), 1540 (s, C=O), 1185 (s, C-O) cm−1.

4.41. General procedure for the synthesis of 5-ASA nitroxides 53–56

A solution of NaOH (3 mL, 1 M) was added to a solution of appropriate amide (47–50) in THF (5 mL) and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT overnight. THF was removed under pressure and the aqueous layer washed with DCM, then cooled in ice/H2O bath and acidified (to pH 1) with HCl (2 M). The precipitate formed was isolated by filtration and purified by recrystallization from H2O/MeOH to give the corresponding salicylic acid derivative (53–56).

4.42. 2-Hydroxy-5-(2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidin-1-yloxyl-3-carboxamido)benzoic acid 53

Yellow solid (170 mg, 84%). Mp. 171 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 323.1601; found 323.1590. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3200 (m, br, O-H), 3921 (m, ArC-H), 1657 (s, C=O), 1547 (s, C=O), 1225 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0008, aN= 1.84 mT.

4.43. 2-Hydroxy-5-(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl-4-carboxamido)benzoic acid 54

Light reddish-brown solid (156 mg, 74%). HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 337.1758; found 337.1753. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3200 (m, br, O-H), 3921 (m, ArC-H), 1657 (s, C=O), 1547 (s, C=O), 1225 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0012, aN= 1.94 mT.

4.44. 2-Hydroxy-5-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-carboxamido)benzoic acid 55

Yellow solid (190 mg, 83%). Mp. 207 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 392.1343; found 392.3146. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3100 (m, br, O-H), 2954 (m, ArC-H), 1676, 1644 (s, C=O), 1565 (s, C=O), 1187 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN= 1.78 mT.

4.45. 2-Hydroxy-5-(1,1,3,3-tetraethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-carboxamido)benzoic acid 56

Yellow solid (209.5 mg, 81%). Mp. 208 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 426.2110; found 425.2109. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3295 (m, br, O-H), 2968 (m, ArC-H), 1686, 1637 (s, C=O), 1536 (s, C=O), 1167 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0010, aN= 1.75 mT.

4.46. 2-Methoxy-5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 58

A Schlenk tube containing 5-bromo-2-methoxy-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 57 (316 mg, 1.11 mmol, 1 equiv.), potassium methyl malonate (434.13 mg, 2.78 mmol, 2.5 equiv.), allylpalladium (II) chloride dimer (8.14 mg, 22 μmol, 0.02 equiv.), BINAP (41.54 mg, 67 μmol, 0.06 equiv.), and DMAP (13.6 mg, 11 μol, 0.01 equiv.) in mesitylene (10 mL) was degassed and then heated for 1 d at 140 °C. The resulting mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue obtained was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane/EtOAc, 5:0.2) to give 2-methoxy-5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 58 as a white solid (164 mg, 54%). Mp. 79–80 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 1.42 (br, s, 12 H, CH3), 3.61 (s, 2 H, CH2), 3.69 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.77 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 7.00 (s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.05 (d, 1 H, J = 8 Hz, Ar-H), 7.14 (d, 1 H, J = 8 Hz, Ar-H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz): δ = 25.3 (w, br, CH3), 29.7 (w, br, CH3), 41.2 (CH2), 52.1 (OCH3), 65.5 (OCH3), 66.9 (C-CH3), 67.1 (C-CH3), 121.7 (Ar-C), 122.4 (Ar-C), 128.2 (Ar-C), 132.9 (Ar-C), 144.1 (Ar-C), 145.6 (Ar-C), 172.2 (C=O). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for C16H24NO3 [M + H]+ 278.1715; found 278.1680. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 2975 (m, Ar C-H), 1736 (s, C=O), 1206 and 1143 (s, C-O) cm−1.

4.47. 5-Methoxycarbonylmethyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 59

m-Chloroperoxybenzoic acid (471 mg, 1.62 mmol, 1.5 equiv., 77%) was added to a solution of methyl 2-methoxy-5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindoline 58 (300 mg, 1.08 mmol, 1 equiv.) in DCM (150 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min and then at RT for further 3.5 h. The resulting solution was washed with saturated NaHCO3 (2 × 30 mL) and brine solutions and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo and the crude residue purified by flash column chromatography (Hexane/EtOAc, 4:1) to give 59 as bright yellow solid (253 mg, 89%). Mp. 96–96.5 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 263.1516; found 263.1508. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 2976 (m, Ar C-H), 1737 (s, C=O), 1155 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN= 1.84 mT.

4.48. 5-Carboxymethyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl 23

NaOH (4 mL, 2 M) was added to a solution of methyl ester 59 (250 mg, 953 μmol, 1 equiv.) in MeOH (6 mL) and the resulting reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at 60 °C. The reaction mixture was cooled to RT and diluted with H2O (30 mL). The aqueous layer was washed with Et2O (30 mL) and acidified (pH 1) with HCl (2 M). The aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (3 × 60 mL) and the combined organic extracts were washed with brine (40 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo to give the carboxylic acid 23 as yellow solid (222 mg, 94%). Mp.123–124 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 271.1179; found 271.1174. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3000 (s, br, O-H), 2977 (m, Ar C-H), 1729 (s, C=O), 1144 (s, C-O) cm−1 g = 2.0009, aN= 1.83 mT.

Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-(2-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoinolin-2-yloxyl-5-yl)acetamido) benzoate 60 was obtained from 46 (124 mg, 591 μmol, 1.1 equiv.), 59 (133.3 mg, 537 μmol, 1 equiv.), EDC (123.5 mg, 599 μmol, 1.2 equiv.), and DMAP (8.2 mg, 67 μmol, 0.125 equiv.) in DCM (10 mL) by following similar coupling conditions as described for 27–29 (silica gel column chromatography: Hexane/EtOAc, 3:1). Yellow solid (224.2 mg, 95%). Mp. 215 °C (dec.). HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 2.34 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 3.85 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 4.21 (br, s, 2 H, CH2), 7.09 (br, s,1 H, Ar-H), 7.86 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.95 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 440.1942; found 440.1939. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3273 (m, N-H), 2976 (m, ArC-H), 1760, 1729 (s, C=O), 1696 (s, C=O), 1548 (s, C=O), 1297 (s, C-N), 1191 and 1079 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN= 1.82 mT.

2-Hydroxy-5-(2-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-yl) acetamido)benzoic acid 61 was obtained from 60 by following similar conditions as described for 53–56. Yellow solid (95%). Mp. 115 C (dec.). HPLC purity (>95%). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 385.1758; found 385.1763. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3263 (m, br, O-H), 2923 (m, ArC-H), 1674, 1647 (s, C=O), 1561 (s, C=O), 1208 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN= 1.82 mT.

4.49. Methyl 2-acetoxy-5-((2-(1,1,3,3-tetramethyl isoindolin-2yloxyl-5-yl)amino)benzoate 62

Anhydrous acetic acid (42 μL, 728 μmol, 5 equiv.) was added dropwise over 10 min to a suspension of NaBH4 (28 mg, 735 μmol, 5.05 equiv.) and methyl benzoate 60 (64 mg, 146 μmol, 1 equiv.) in dry dioxane (3 mL). The resulting reaction mixture was refluxed for 30 min and then allowed to return to RT. H2O was added and the resulting aqueous solution was extracted with EtOAc (4 × 30 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine (30 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified silica gel column chromatography (Hexane/EtOAc, 3:1) to give methyl 2-acetoxy-5-((2-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2yloxyl-5-yl)amino)benzoate 62 as yellow solid (42 mg, 68%). Mp. 85–87 °C. HPLC purity (>95%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz): δ = 2.31 (s, 3 H, C=OCH3), 3.45 (br, s, 2 H, CH2), 3.85 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 6.76 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 6.92 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.08 (br, s, 1 H, Ar-H). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 426.2149; found 426.2151. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3371 (m, N-H), 2972 (w, Ar C-H), 1746 (s, C=O), 1715 (s, C=O), 1195 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN= 1.81 mT.

2-Hydroxy-5-((2-(1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl-5-yl)ethyl)amino)benzoic acid 63 was obtained from 62 by following similar conditions as described for 53–56. Brownish yellow solid (72%). Mp. 200 °C (dec.). HRMS (ES): m/z (%) = calcd. for 370.1887; found 370.1895. ATR-FTIR: υmax= 3500–2500 (m, br, O-H), 2975 (m, Ar C-H), 1681 (s, C=O), 1215 (s, C-O) cm−1; g = 2.0009, aN= 1.81 mT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Free Radical Chemistry and Biotechnology (CE 0561607) and Queensland University of Technology (KT, KEF, SEB). The research was also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Cancer and Inflammation Program (TWM, LAR, DAW).

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- AcCl

acetyl chloride

- AMC

antimycin

- ASA

amino salicylic acid

- BINAP

(±)-2,2′-Bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthalene

- br

broad

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- DCM

dichloromethane

- dd

doublet of doublet

- DMAP

4-Dimethylaminopyridine

- EDC

N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- EtOH

ethanol

- FTIR

fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- MeCN

acetonitrile

- MeOH

methanol

- MTT

[3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide]

- nBulmi

N-butylimidazole

- O/N

overnight

- PG, PGE2

Prostaglandins E2

- QTOF

LC-MS Quadrupole Time of Flight Mass Spectrometer Liquid Chromatography-Mass Chromatography

- RT

room temperature

- TEA

trimethylamine

- TEMPO

2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-yloxyl

- Tempol

4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yloxyl

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TMIO

1,1,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl

- w

weak

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.077.

References

- [1].Ferencik M, Novak M, Rovensky J, Rybar I, Alzheimer’s disease, inflammation and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Bratisl. Lek. Listy 102 (2001) 123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].But PG, Murav’ev RA, Fomina VA, Rogovin VV, Antimicrobial activity of myeloperoxidase from neutrophilic peroxisome, Biol. Bull. 29 (2002) 212–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Floyd RA, Antioxidants, oxidative stress, and degenerative neurological disorders, Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 222 (1999) 236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tantry US, Mahla E, Gurbel PA, Aspirin resistance, Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 52 (2009) 141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Soule BP, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K-I, Simone NL, Cook JA, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, The chemistry and biology of nitroxide compounds, Free Radical Biol. Med. 42 (2007) 1632–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Helmersson J, Vessby B, Larsson A, Basu S, Cyclooxygenase-mediated prostaglandin F2α is decreased in an elderly population treated with low-dose aspirin, Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 72 (2005) 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ong CKS, Lirk P, Tan CH, Seymour RA, An evidence-based update on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Clin. Med. Res. 5 (2007) 19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Supinski GS, Callahan LA, Free radical-mediated skeletal muscle dysfunction in inflammatory conditions, J. Appl. Physiol. 102 (2007) 2056–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vane J, Botting R, Inflammation and the mechanism of action of anti-inflammatory drugs, FASEB J. 1 (1987) 89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mutlu LK, Woiciechowsky C, Bechmann I, Inflammatory response after neurosurgery, Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 18 (2004) 407–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Halliwell B, Hoult JR, Blake DR, Oxidants, inflammation, and anti-inflammatory drugs, FASEB J. 2 (1988) 2867–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dal-Pizzol F, Ritter C, Cassol OJ Jr., Rezin GT, Petronilho F, Zugno AI, Quevedo J, Streck EL, Oxidative mechanisms of brain dysfunction during sepsis, Neurochem. Res. 35 (2010) 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rao PPN, Kabir SN, Mohamed T, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): progress in small molecule drug development, Pharmaceuticals 3 (2010) 1530–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rainsford KD, Whitehouse MW, Paracetamol [acetaminophen]-induced gastrotoxicity: revealed by induced hyperacidity in combination with acute or chronic inflammation, Inflammopharmacology 14 (2006) 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Robak P, Smolewski P, Robak T, The role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the risk of development and treatment of hematologic malignancies, Leuk. Lymphoma 49 (2008) 1452–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Closa D, Folch-Puy E, Oxygen free radicals and the systemic inflammatory response, IUBMB Life 56 (2004) 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Arnhold J, Properties, functions, and secretion of human myeloperoxidase, Biochemistry (Moscow, Russ Fed) 69 (2004) 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Grisham MB, A radical approach to treating inflammation, Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 21 (2000) 119–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pattison DI, Davies MJ, Reactions of myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants with biological substrates: gaining chemical insight into human inflammatory diseases, Curr. Med. Chem. 13 (2006) 3271–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jaeschke H, Reactive oxygen and mechanisms of inflammatory liver injury, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15 (2000) 718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chapple ILC, Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in inflammatory diseases, J. Clin. Periodontol. 24 (1997) 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liew FY, McInnes IB, The role of innate mediators in inflammatory response, Mol. Immunol. 38 (2002) 887–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Molina DM, Wetterholm A, Kohl A, McCarthy AA, Niegowski D, Ohlson E, Hammarberg T, Eshaghi S, Haeggstroem JZ, Nordlund P, Structural basis for synthesis of inflammatory mediators by human leukotriene C4 synthase, Nature (London, U. K.) 448 (2007) 613–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Botting R, COX-1 and COX-3 inhibitors, Thromb. Res. 110 (2003) 269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Peskar BM, Role of cyclooxygenase isoforms in gastric mucosal defense and ulcer healing, Inflammopharmacology 13 (2005) 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Deguchi H, Yasukawa K, Yamasaki T, Mito F, Kinoshita Y, Naganuma T, Sato S, Yamato M, Ichikawa K, Sakai K, Utsumi H, Yamada K, Nitroxides prevent exacerbation of indomethacin-induced gastric damage in adjuvant arthritis rats, Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51 (2011) 1799–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Flores-Santana W, Moody T, Chen W, Gorczynski MJ, Shoman ME, Velázquez C, Thetford A, Mitchel JB, Cherukuril MK, King SB, Wink DA, Nitroxide derivatives of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs exert anti-inflammatory and superoxide dismutase scavenging properties in A459 cells, Br. J. Pharmacol. 165 (2012) 1058–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Trnka J, Blaikie FH, Logan A, Smith RA, Murphy MP, Antioxidant properties of MitoTEMPOL and its hydroxylamine, Free Radic. Res. 43 (2009) 4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Soule BP, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K-I, Simone NL, Cook JA, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, Therapeutic and clinical applications of nitroxide compounds, Antioxidants Redox Signal. 9 (2007) 1731–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Decker M, Design of Hybrid Molecules for Drug Development, Elsevier Publishers, 2017, ISBN 9780081010112, 352 pages. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lewandowski M, Gwozdzinski K, Nitroxides as antioxidants and anticancer drugs, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 (11) (2017) 2490–2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Micallef AS, Bott RC, Bottle SE, Smith G, White JM, Matsuda K, Iwamura H, Brominated isoindolines: precursors to functionalized nitroxides, J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 2 (1999) 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fairfull-Smith KE, Bottle SE, The synthesis and physical properties of novel polyaromatic profluorescent isoindoline nitroxide probes, Eur. J. Org Chem. 32 (2008) 5391–5400. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shang R, Ji DS, Chu L, Fu Y, Liu L, Synthesis of α-aryl nitriles through palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative coupling of cyanoacetate salts with aryl halides and triflates, Angew. Chem. 50 (19) (2011) 4470–4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Bepler G, Blum MG, Chang A, Cheney RT, Chirieac LR, D’Amico TA, Demmy TL, Ganti AKP, Non-small cell lung cancer: clinical practice guidelines in oncology, J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 8 (2010) 740–801.20679538 [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kalyanaraman B, Darley-Usmar V, Davies KJA, Dennery PA, Forman HJ, Grisham MB, Mann GE, Moore K, Roberts II LJ, Ischiropoulose H, Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: challenges and limitations, Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52 (1) (2012) 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lippman SM, Gibson N, Subbaramaiah K, Dannenberg AJ, Combined targeting of the epidermal growth factor receptor and cyclooxygenase-2 pathways, Clin. Canc. Res. 11 (2005) 6097–6099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Buchanan FG, Wang D, Bargiacchi F, DuBois RN, Prostaglandin E2 regulates cell migration via the intracellular activation of epidermal growth factor receptor, J. Biol. Chem. 278 (2003) 35451–35457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dannenberg AJ, Subbaramaiah K, Targeting cyclooxygenase-2 in human neoplasia: rationale and promise, Canc. Cell 4 (2003) 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pai R, Soreghan B, Szabo IL, Pavelka M, Baatar D, Tarnawski AS, Prostaglandin E2 transactivates EGF receptor: a novel mechanism for promoting colon cancer growth and gastrointestinal hypertrophy, Nat. Med. 8 (2002) 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rayner CL, Bottle SE, Gole GA, Ward MS, Barnett NL, Real-time quantification of oxidative stress and the protective effect of nitroxide antioxidants, Neurochem. Int. 92 (2016) 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Morrow BJ, Keddie DJ, Gueven N, Lavin MF, Bottle SE, A novel profluorescent nitroxide as a sensitive probe for the cellular redox environment, Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49 (1) (2010) 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li S-Y, Fung FKC, Fu ZJ, Wong D, Chan HHL, Lo ACY, Anti-inflammatory effects of lutein in retinal ischemic/hypoxic injury: in vivo and in vitro studies, Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53 (2012) 5976–5984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rayner CL, Gole GA, Bottle SE, Barnett NL, Dynamic, in vivo, real-time detection of retinal oxidative status in a model of elevated intraocular pressure using a novel, reversibly responsive, profluorescent nitroxide probe, Exp. Eye Res. 129 (2014) 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Griffiths PG, Moad G, Rizzardo E, Synthesis of the radical scavenger 1,1,3,3-tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl, Aust. J. Chem. 36 (1983) 397–401. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bolton R, Gillies DG, Sutcliffe LH, Wu X, An EPR and NMR study of some tetramethylisoindolin-2-yloxyl free radicals, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 (1993) 2049–2052. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Fairfull-Smith KE, Brackmann F, Bottle SE, The synthesis of novel isoindoline nitroxides bearing water-solubilising functionality, Eur. J. Org Chem. 12 (2009) 1902–1915. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Thomas K, Chalmers BA, Fairfull-Smith KE, Bottle SE, Approaches to the synthesis of a water-soluble carboxy nitroxide, Eur. J. Org Chem. 5 (2013) 853–857. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Guo W, Li J, Fan N, Wu W, Zhou P, Xia C, A simple and effective method for chemoselective esterification of phenolic acids, Synth. Commun. 35 (2005) 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Csipo I, Szabo G, Sztaricskai F, 5-Aminosalicylic acid and its glucopyranosyl derivatives, Magy. Kem. Foly. 97 (1991) 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Akdogan Y, Emrullahoglu M, Tatlidil D, Ucuncu M, Cakan-Akdogan G, EPR studies of intermolecular interactions and competitive binding of drugs in a drug-BSA binding model, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18 (32) (2016) 22531–22539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wink DA, Flores-Santana W, King SB, Cherukuri MK, Mitchell JB, Nitroxide modified non-steroidal anti-inflammatory compounds and their preparation and use for the treatment and prevention of diseases, U.S. Pat. Appl. (2012), US 20120263650 A1 20121018. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hauenschild T, Reichenwallner J, Enkelmann V, Hinderberger D, Characterizing active pharmaceutical ingredient binding to human serum albumin by spin-labeling and EPR spectroscopy, Chem. Eur J. 22 (36) (2016) 12825–12838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Wood ME, Winyard PG, Ferguson DC, Whiteman M, Combinations of a photosensitizer with a hydrogen sulfide donor, thioredoxin inhibitor or nitroxide for use in photodynamic therapy, PCT Int. Appl. (2015). WO 2015185918 A1 20151210. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.