Abstract

Objectives

Although US state laws shape population health and health equity, few studies have examined how state laws affect the health of marginalized racial/ethnic groups (eg, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx populations) and racial/ethnic health inequities. A team of public health researchers and legal scholars with expertise in racial equity used systematic policy surveillance methods to develop a comprehensive database of state laws that are explicitly or implicitly related to structural racism, with the goal of evaluating their effect on health outcomes among marginalized racial/ethnic groups.

Methods

Legal scholars used primary and secondary sources to identify state laws related to structural racism pertaining to 10 legal domains and developed a coding scheme that assigned a numeric code representing a mutually exclusive category for each salient feature of each law using a subset of randomly selected states. Legal scholars systematically applied this coding scheme to laws in all 50 US states and the District of Columbia from 2010 through 2013.

Results

We identified 843 state laws linked to structural racism. Most states had in place laws that disproportionately discriminate against marginalized racial/ethnic groups and had not enacted laws that prevent the unjust treatment of individuals from marginalized racial/ethnic populations from 2010 to 2013.

Conclusions

By providing comprehensive, detailed data on structural racism–related state laws in all 50 states and the District of Columbia over time, our database will provide public health researchers, social scientists, policy makers, and advocates with rigorous evidence to assess states’ racial equity climates and evaluate and address their effect on racial/ethnic health inequities in the United States.

Keywords: structural racism, race/ethnicity, US state policy, policy surveillance, legal epidemiology, health equity

Racial/ethnic health inequities are a pervasive problem in the United States. 1 Data show that, on average, Black, Indigenous (including Native American, Native Alaskan, and Native Hawaiian), and Latinx people fare worse than their White counterparts in various health outcomes, including HIV/AIDS, infant mortality, and diabetes. 2 Racism—which operates at the interpersonal, cultural, and structural levels—is a key determinant of racial/ethnic health inequities, and these inequities are not explained by differences in socioeconomic factors. 2 -5 In particular, racism marginalizes, or systematically excludes, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people from power, status, and other social, economic, and political resources and opportunities, all of which are important social determinants of population health and health inequities. 2,6 In recent years, public health researchers have increasingly examined the role of not only interpersonal but also structural racism in shaping population health outcomes across and within racial/ethnic groups. 1,2,7 Specifically, investigators have found that structural racism—defined as the historically contingent and persistent ways in which social systems and institutions generate and reinforce inequities in access to power, privilege, and other resources among racial/ethnic groups deemed to be superior and those viewed as inferior 1,2,7 —negatively affects health outcomes, including breast cancer, premature mortality, birth outcomes, and cardiovascular disease, among Black people. 1,2,8 -11 In addition, scholars have shown that structural racism, including genocide and immigration policies, undermines the physical and mental health of Native American and Hispanic people, respectively. 1,7,12

According to critical race theory (ie, a collection of intellectual, social, and political practices aimed at studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power), structural racism—which evolves and stems from historical processes such as genocide, slavery, and immigrant exclusion—operates through and is embedded in contemporary federal and state-level laws and policies pertaining to various social systems and institutions, including housing, education, health care, employment, criminal justice, voting rights, and immigration. 13 -17 Past and present laws and policies overtly and covertly, directly and indirectly, and actively and passively (through both inaction and colorblindness) determine the inequitable allocation of social, economic, political, and environmental resources and harms across racial/ethnic groups today. 13 -17 For example, as a result of historical and contemporary housing and banking laws, policies, and practices (eg, redlining, mortgage lending, zoning) that explicitly or implicitly favor White people and disadvantage marginalized racial/ethnic groups, Black, Native American, and Hispanic people are more likely than their White counterparts to live in systematically underresourced neighborhoods that lack access to high-quality infrastructure, social and health services, and educational and employment opportunities. 1,2,7,17

Moreover, as a result of criminal justice laws, policies, and practices that disproportionately affect marginalized racial/ethnic groups (eg, stop-and-identify laws, which allow law enforcement officers to stop a person and demand identification upon “reasonable suspicion” of a crime, and drug sentencing laws), Black, Native American, and Hispanic people—who tend to be the target of over-policing, arrest, and incarceration as a result of conscious and unconscious negative racial stereotypes—are disproportionately represented in US prisons and jails. 1,17 -19 Consequently, voting rights laws that disenfranchise people with previous convictions disproportionately affect Black people and individuals from other marginalized racial/ethnic groups. 18 Furthermore, given pervasive racist stereotypes that erroneously depict Black people as dangerous criminals, stand-your-ground laws systematically threaten the rights and lives of Black people by selectively allowing a person deemed to be superior to harm or kill a Black person by claiming self-defense, even in the absence of an actual threat. 20

In addition, as a result of laws, policies, and practices that undermine the intergenerational transfer of wealth among Black communities and other marginalized racial/ethnic groups, as well as both structural and interpersonal racism in the education system and employment sector, Black, Native American, and Hispanic people tend to have lower levels of wealth and income than their White counterparts. 1 -4,13,14,17 Consequently, laws pertaining to the minimum wage, income-related housing laws, and predatory lending laws disproportionately affect marginalized racial/ethnic groups. Moreover, as a result of conscious and unconscious biases inaccurately depicting Black people as threatening or violent, Black students are more likely than their White counterparts to be disciplined using force in elementary schools and high schools. 21 -23 Thus, laws that prohibit corporal punishment in public schools will particularly affect Black students and students from other marginalized racial/ethnic groups. Lastly, immigration laws disproportionately target Black and Hispanic immigrants and lead to the social exclusion of marginalized racial/ethnic groups by prohibiting entry, facilitating deportation, and limiting access to social, economic, and political opportunities and resources, as well as legal rights, among immigrants from marginalized racial/ethnic groups deemed to be undesirable. 7,12

In recent years, public health scholars and practitioners have called for greater scientific inquiry into the influence of laws and policies on population health and health inequities. 24 -28 Investigators have found that US state laws, such as state same-sex marriage laws, state Medicaid expansions, and state physical education and daily recess laws, play an important role in shaping the population distribution of various health outcomes, including mental health, cancer screening, and physical activity, within and across social groups. 29 -31 However, excluding the studies conducted by Krieger et al 8 -10 to examine the effect of historical Jim Crow laws on contemporary health inequities between Black and White people, studies assessing the effect of state laws related to structural racism on inequitable distributions of health outcomes across racial/ethnic groups are scarce. 1

Nonetheless, theory and empirical research suggest that historical and contemporary state laws that overtly or covertly privilege White people and disadvantage people from marginalized racial/ethnic groups shape racial/ethnic health inequities through various social, economic, physical, and psychological mechanisms—including economic, residential, educational, and occupational segregation of marginalized racial/ethnic groups into low-quality neighborhoods, schools, and jobs; disproportionate exposure of marginalized racial/ethnic groups to environmental toxins and occupational hazards, as well as chronic and acute psychosocial stressors; forced removal and alienation of marginalized racial/ethnic groups from traditional land resources and practices; discriminatory arrest, detention, and incarceration practices; and fewer health care providers and high-quality facilities in communities of color than in predominantly White neighborhoods. 1 -5,7,32,33 For example, research shows that racial residential segregation, which is linked to housing and banking laws, policies, and practices that disproportionately disadvantage Black people and people from other marginalized racial/ethnic groups, is negatively associated with low birth weight and preterm birth among Black women and higher rates of breast and lung cancer mortality among Black people compared with White people. 2,7,33 Furthermore, investigators found that living in a neighborhood with high levels of police stopping and frisking pedestrians, which occurs disproportionately in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods and disproportionately affects Native American people, 19,34,35 is associated with poor mental and physical health outcomes, including psychological distress, diabetes, and high blood pressure. 36

Policy surveillance, which involves the systematic tracking of laws and policies over time, is a central component of legal epidemiology, an emerging field that investigates law as a determinant of disease etiology, distribution, and prevention in populations. 24,25 Policy surveillance provides data necessary to rigorously evaluate the effect of state laws and policies on population health and health inequities. 24,25 Although databases pertaining to one or some of the issues of interest are available, 37 to our knowledge, no comprehensive database pertaining to US state laws that shape the inequitable allocation of social, economic, and political resources among various marginalized racial/ethnic groups relative to their White counterparts exists.

However, systematically collecting information on state laws related to structural racism over time and place and linking them to individual-level health outcomes is critical for rigorously evaluating their effect on the health of people from marginalized racial/ethnic groups and the magnitude of racial/ethnic health inequities. 24,25 Identifying how state laws that are explicitly or implicitly related to structural racism affect health outcomes among marginalized racial/ethnic groups—including, but not limited to, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people—may help inform evidence-based policy- and system-level initiatives that repeal unjust and harmful laws, policies, and practices and instead promote social justice and health equity.

We describe the process, undertaken collaboratively by an interdisciplinary team of public health researchers and legal scholars, of developing a comprehensive, longitudinal database of state laws that are explicitly or implicitly related to structural racism and that uniquely or disproportionately undermine the distribution of and access to social, economic, and political resources to various marginalized racial/ethnic groups (eg, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx populations). 13 -17 In addition, we characterize the distribution of state laws related to structural racism in the 50 US states and the District of Columbia from 2010 through 2013 and calculate the absolute and percentage change in the number of laws related to structural racism during that period.

Methods

Guided by critical race theory, 13 -16 using empirical studies pertaining to structural racism and health inequities, 1,2,7,12 and reviewing reports and fact sheets on racism and the law developed by legal organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union 38 and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 39 the public health researchers on our team developed a preliminary typology of contemporary legal domains pertaining to state-level structural racism in the United States. Our team’s legal scholars then reviewed and revised this initial typology based on their expertise and practical, on-the-ground experience in racial equity. Through this process, we developed a final typology of 10 legal domains related to contemporary state-level structural racism in the United States: voting rights, stand-your-ground laws, racial profiling laws, mandatory minimum prison sentencing laws, immigrant protections, fair-housing laws, minimum-wage laws, predatory lending laws, laws concerning punishment in schools, and stop-and-identify laws.

Using law review articles and legal reports and in consultation with one another and additional racial equity legal experts, our team’s legal scholars determined the laws that should be included in each domain. The scholars then identified the scope and features (eg, population covered or affected, length of related sentence, exceptions, enforcement mechanisms) of each law using primary and secondary (ie, law review articles, legal reports) sources. The 2 legal scholars then characterized each law using a set of mutually exclusive categories (assigned a numeric value) and compiled the categories into a preliminary coding scheme. The legal scholars then collected information on each law using multiple legal databases (ie, Westlaw Next, LexisNexis, Hein Online) for a subset of 6 to 12 randomly selected states (depending on the complexity and variability of a given law across states) in a given year (ie, 2010). The scholars then used the scheme to assign a numerical value to each state for each law in that year. The coding scheme was then revised and finalized based on this process. To ensure that this scheme was applied consistently by the 2 legal scholars, they developed a guide defining each law and its categories and outlining key questions to consider when assigning a numerical value to each state and the District of Columbia for each law using the scheme.

From September 2017 through November 2018, the 2 legal scholars collected information on each law for all 50 states and the District of Columbia in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 using multiple legal databases (ie, Westlaw Next, LexisNexis, Hein Online). Given the time-intensive nature of legal research and funding constraints, we limited the study period to 4 years (ie, 2010-2013). The scholars then assigned a numeric value to each state and the District of Columbia for each law in each year of the study period using the coding scheme. The legal scholars carefully documented any question or issue that arose during the coding process, discussed and resolved them during regular meetings, and iteratively revised and reapplied the coding scheme as needed. In addition, each legal scholar reviewed a subset of the other legal scholar’s coded laws to ensure accuracy. Moreover, the legal scholars documented the specific language that informed the numeric value assigned to each state for a given law and catalogued relevant legal citations and each law’s statutory history during the study period.

In consultation with the legal scholars, the public health researchers on our team reviewed the compiled data and examined patterns in state laws related to structural racism across and within states and years during the study period. The public health researchers then generated descriptive statistics (counts and percentages) to characterize the distribution of all 50 states and the District of Columbia in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 with regard to each law in each legal domain. In addition, we calculated both the absolute and percentage change in the number of explicitly and implicitly racialized state laws from 2010 through 2013. Lastly, we also visualized the data for 4 of the 10 legal domains (namely, voting rights, stand-your-ground laws, mandatory minimum prison sentencing laws, and fair-housing laws) using maps generated in Matlab (Mathworks Inc).

Results

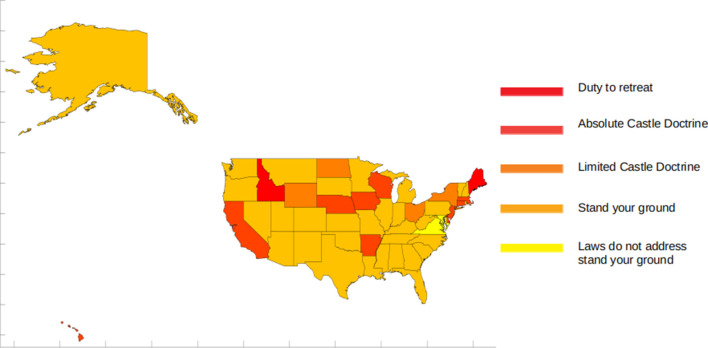

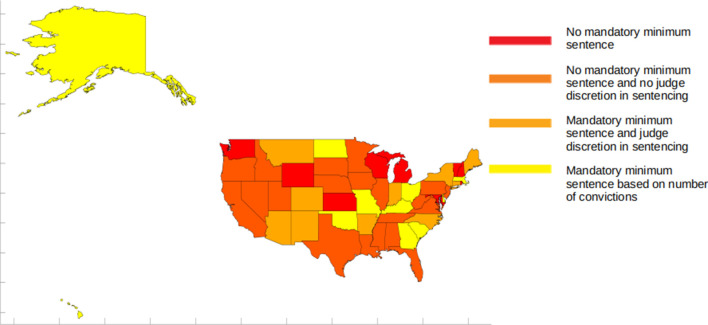

We identified 843 US state laws explicitly or implicitly related to structural racism across the 10 contemporary legal domains (ie, voting rights laws, stand-your-ground laws, racial profiling laws, mandatory minimum prison sentencing laws, immigrant protections, fair-housing laws, minimum-wage laws, predatory lending laws, laws concerning punishment in schools, and stop-and-identify laws) in all 50 states and the District of Columbia from 2010 through 2013. We found that, during the study period, laws that disproportionately discriminated against people from marginalized racial/ethnic groups, including stand-your-ground laws (Figure 1), mandatory minimum sentencing laws (Figure 2), and stop-and-identify laws (Table), were in place in most states. For example, in 2013, twenty-three states had stand-your-ground laws in place (Figure 1), and 41 had passed laws on mandatory minimum sentencing (Figure 2; Table).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of stand-your-ground laws in 50 US states and the District of Columbia, 2013.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of mandatory minimum sentencing laws in 50 US states and the District of Columbia, 2013.

Table.

Distribution of and change in contemporary structural racism–related laws in the 50 states and the District of Columbia (N = 51), by legal domain and year, 2010-2013

| Laws | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Absolute change in no. of states with law (from 2010 to 2013) | Percentage change in no. of states with law (from 2010 to 2013) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of states (%) | No. of states (%) |

No. of states (%) |

No. of states (%) |

|||

| Stand-Your-Ground | ||||||

| Duty to retreat (required to retreat) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Absolute Castle Doctrine (not required to retreat within one’s home) | 12 (24) | 12 (24) | 11 (22) | 10 (20) | –2 | –4 |

| Limited Castle Doctrine (required to mitigate situation before using force) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Stand your ground (not required to retreat in any circumstance) | 28 (55) | 30 (59) | 31 (61) | 32 (63) | 4 | 8 |

| Self-defense (only permits self-defense in limited circumstances) | 5 (10) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | –2 | –4 |

| Mandatory Minimum Sentencing | ||||||

| State does not impose mandatory minimum sentencing | 11 (22) | 10 (20) | 10 (20) | 10 (20) | –1 | –2 |

| State imposes mandatory minimum sentencing on drug offenses and does not allow judicial discretion | 20 (39) | 20 (39) | 20 (39) | 20 (39) | 0 | 0 |

| State imposes mandatory minimum sentencing on drug offenses and allows judicial discretion | 10 (20) | 10 (20) | 10 (20) | 10 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| State imposes mandatory minimum sentencing depending on number of convictions | 10 (20) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 1 | 2 |

| Racial Profiling | ||||||

| Racial profiling data collection | ||||||

| State does not mandate racial profiling data collection from traffic stops | 35 (69) | 35 (69) | 35 (69) | 35 (69) | 0 | 0 |

| State mandates racial profiling data collection from every traffic stop | 16 (31) | 16 (31) | 16 (31) | 16 (31) | 0 | 0 |

| Laws prohibiting racial profiling law | ||||||

| State does not prohibit racial profiling | 31 (61) | 31 (61) | 31 (61) | 31 (61) | 0 | 0 |

| State explicitly prohibits racial profiling | 17 (33) | 17 (33) | 17 (33) | 18 (35) | 1 | 2 |

| State explicitly prohibits racial profiling and has a set punishment for racial profiling | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Racial profiling training | ||||||

| State does not require racial profiling training for law enforcement officers | 39 (76) | 40 (78) | 40 (78) | 40 (78) | 1 | 2 |

| State requires racial profiling training for law enforcement officers | 12 (24) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11(22) | –1 | –2 |

| Any racial profiling | ||||||

| State does not have any law related to racial profiling | 24 (47) | 24 (47) | 24 (47) | 24 (47) | 0 | 0 |

| State has a law related to racial profiling | 27 (53) | 27 (53) | 27 (53) | 27 (53) | 0 | 0 |

| Minimum Wage | ||||||

| State minimum wage in relation to federal minimum wage | ||||||

| State’s minimum wage was ≤$0.50 more than the federal minimum wage | 41 (80) | 41 (80) | 41 (80) | 41 (80) | 0 | 0 |

| State’s minimum wage was >$0.50 more than the federal minimum wage | 10 (20) | 10 (20) | 10 (20) | 10 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| Limits on minimum wage | ||||||

| State does not limit minimum wage | 38 (75) | 38 (75) | 38 (75) | 38 (75) | 0 | 0 |

| State prohibits any city or town from setting its minimum wage above the federal minimum wage or limits it from exceeding the minimum wage by more than $1.00 | 8 (16) | 8 (16) | 8 (16) | 8 (16) | 0 | 0 |

| Not applicable (state follows federal minimum wage) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 0 | 0 |

| Minimum-wage adjustments | ||||||

| State does not require minimum-wage adjustments according to the cost of living or inflation | 34 (67) | 34 (67) | 34 (67) | 34 (67) | 0 | 0 |

| State requires minimum-wage adjustments according to the cost of living or inflation | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 0 | 0 |

| Not applicable (state follows federal minimum wage) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| Minimum-wage exemptions | ||||||

| State does not include an exemption that would lead to a salary below the federal minimum wage | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 6(12) | 6 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| State permits an employer to pay some employees below the federal minimum wage based on ≥1 exemption (ie, annual gross sale numbers, productivity levels related to a disability) | 39 (76) | 40 (78) | 40 (78) | 39 (76) | 0 | 0 |

| Not applicable (state follows federal minimum wage) | 6 (12) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 6 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| Undocumented Immigrant Protection | ||||||

| Identification | ||||||

| State does not allow undocumented immigrants to obtain a driver’s license or state identification | 48 (94) | 48 (94) | 47(92) | 40 (40) | –8 | –16 |

| State allows undocumented immigrants to obtain a driver’s license or state identification | 3(6) | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | 11 (22) | 8 | 16 |

| Health insurance coverage | ||||||

| State provides health insurance coverage to all immigrant children, regardless of immigration status | 19 (37) | 19 (37) | 19(37) | 19 (37) | 0 | 0 |

| State provides health insurance coverage to documented immigrant children only | 26 (51) | 25 (49) | 25 (49) | 25 (49) | 0 | 0 |

| State provides coverage to undocumented immigrant children | 5 (10) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| In-state tuition | ||||||

| Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for in-state tuition benefits | 41 (80) | 38 (75) | 39 (76) | 33(65) | –8 | –16 |

| Undocumented immigrants are eligible for in-state tuition benefits | 10 (20) | 13 (25) | 12 (24) | 18 (35) | 8 | 16 |

| Voting Rights | ||||||

| Identification requirement | ||||||

| State does not require identification for voting | 27 (53) | 27 (53) | 23 (45) | 21 (41) | –6 | –12 |

| State requires identification for voting but if no identification is available, a provisional ballot or affidavit is accepted | 11 (22) | 13 (25) | 14 (27) | 15 (30) | 4 | 8 |

| State requires identification for voting but identification does not need to include a photo | 6 (12) | 4 (8) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | –1 | –2 |

| State requires some type of photo identification for voting | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | 5 (10) | 2 | 4 |

| State requires a government-issued photo identification for voting | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 5 (10) | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| Voter disenfranchisement | ||||||

| State does not remove voting rights for people with criminal convictions | 2 (4) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| State automatically restores voting rights upon release from prison | 15 (29) | 15 (15) | 15 (15) | 15 (15) | 0 | 0 |

| State automatically restores voting rights upon release from prison and discharge from parole | 3 (6) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| State automatically restores voting rights upon completion of entire sentence, including prison, parole, and probation | 19 (37) | 19 (37) | 19 (37) | 19 (37) | 0 | 0 |

| State permanently removes voting rights based on court discretion, unless government approves restoration | 8 (16) | 8 (16) | 8(16) | 8 (16) | 0 | 0 |

| Stop and Identify | ||||||

| General | ||||||

| State has no law addressing law enforcement officers’ authority to stop and demand identification | 25 (49) | 24 (47) | 24 (47) | 24 (47) | –1 | –2 |

| State allows law enforcement officers to stop and demand identification upon reasonable suspicion that a crime has been or is about to be committed or the person has information about a crime | 25 (49) | 26 (51) | 26 (51) | 26 (51) | 1 | 2 |

| Response requirements | ||||||

| State does not require provision of identification upon request by a law enforcement officer | 25 (49) | 25 (49) | 25 (49) | 25 (49) | 0 | 0 |

| State does not impose a legal obligation to provide identification upon request by a law enforcement officer but “may demand” or “may require” disclosure of identifying information | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 0 | 0 |

| State requires provision of identification upon request by a law enforcement officer | 14 (27) | 14 (27) | 14 (27) | 14 (27) | 0 | 0 |

| Failure to respond penalization | ||||||

| State does not penalize people for failing to provide identification upon request by a law enforcement officer | 40 (78) | 40 (78) | 40(78) | 40 (78) | 0 | 0 |

| State penalizes people in some form (ie, as an offense or by considering it as a factor in arrest) for failing to provide identification upon request by a law enforcement officer | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 0 | 0 |

| Predatory Lending | ||||||

| State has no consumer protection law | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| State provides comprehensive consumer protection (including credit and real estate) | 29 (57) | 29 (57) | 29 (57) | 29 (57) | 0 | 0 |

| State provides consumer protection for credit but not real estate | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| State provides consumer protection for real estate but not credit | 9 (18) | 9 (18) | 9 (18) | 9 (18) | 0 | 0 |

| State does not provide consumer protection for real estate or credit | 7 (14) | 7 (14) | 7 (14) | 7 (14) | 0 | 0 |

| Corporal Punishment in Public Schools | ||||||

| State has outlawed corporal punishment in public schools | 16 (31) | 17 (33) | 17 (33) | 17 (33) | 1 | 2 |

| State permits corporal punishment in public schools in limited circumstances | 14 (27) | 14 (27) | 14 (27) | 14 (27) | 0 | 0 |

| State permits corporal punishment in public schools, regardless of circumstance | 14 (27) | 15 (29) | 15 (29) | 15 (29) | 1 | 2 |

| State has no law on corporal punishment in public schools | 7 (14) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | –1 | –2 |

| Fair Housing | ||||||

| Domestic violence | ||||||

| State allows victims of domestic violence to break a lease without penalty, provided they provide proof and/or notice | 13 (25) | 13 (25) | 14 (27) | 15 (29) | 2 | 4 |

| State imposes penalties on victims of domestic violence when breaking a lease and requires proof | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 0 | 0 |

| State has no law on whether victims of domestic violence can break a lease, but victims are protected against discrimination in housing | 7 (14) | 7 (14) | 7 (14) | 7 (14) | 0 | 0 |

| State has no law on whether victims of domestic violence can break a lease | 26 (51) | 2 (51) | 25 (49) | 24 (47) | –2 | –4 |

| Source of income discrimination | ||||||

| State prohibits landlords from discriminating against tenants based on source of income | 12 (24) | 12 (24) | 13 (25) | 13 (25) | 1 | 2 |

| State does not prohibit landlords from discriminating against tenants based on source of income | 38 (76) | 38 (76) | 37(73) | 37 (73) | –1 | –2 |

| State has no law on discrimination in housing based on source of income | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Drug felony convictions | ||||||

| State includes people who have been convicted of a drug felony in fair-housing protections | 33 (65) | 33 (65) | 33 (65) | 33 (65) | 0 | 0 |

| State excludes people who have been convicted of a drug felony from fair-housing protections | 17 (33) | 17 (33) | 17 (33) | 17 (33) | 0 | 0 |

| State has no law on discrimination in housing based on drug felony conviction | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Eviction notice | ||||||

| State administers eviction notice after ≥15 days of not paying rent | 2 (39) | 2 (39) | 2 (39) | 2 (39) | 0 | 0 |

| State administers eviction notice after 11-14 days of not paying rent | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 0 | 0 |

| State administers eviction notice after 6-10 days of not paying rent | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 0 | 0 |

| State administers eviction notice after 3-5 days of not paying rent | 34 (67) | 34 (67) | 34 (67 | 34 (67) | 0 | 0 |

| State has no law on eviction notice | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

aPercentages may not total to 100 because of rounding. Although Jim Crow laws are included in the database, they were not included in the results for the present article, which pertains to 2010-2013, as they were abolished by the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

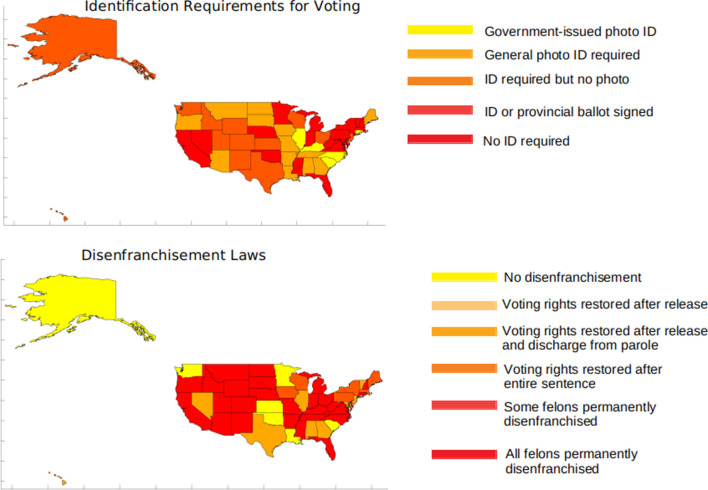

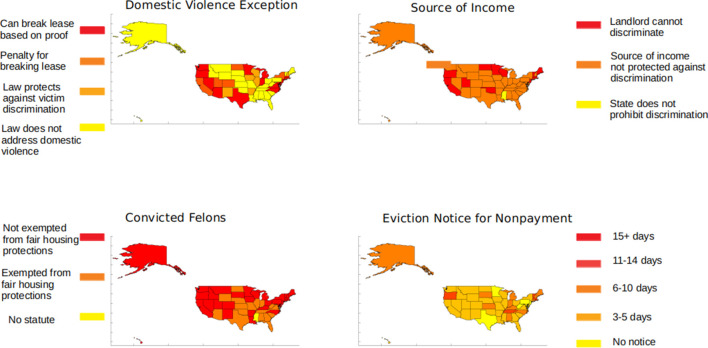

Similarly, most states had not enacted laws that prevent unjust treatment or undue burden among people from marginalized racial/ethnic groups from 2010 through 2013, including laws that prohibit racial profiling (Table), prevent voter disenfranchisement upon a criminal conviction (Figure 3), completely outlaw corporal punishment in public schools (Table), or prevent discrimination in housing based on source of income (Figure 4; Table). For example, in 2013, only 2 states had laws in place that did not remove voting rights for people with criminal convictions (Figure 3), and only 13 states had passed laws that prohibit landlords from discriminating against tenants based on source of income (Figure 4; Table).

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of voting rights laws in 50 US states and the District of Columbia, 2013. Abbreviation: ID, identification.

Figure 4.

Geographic distribution of fair-housing laws in 50 US states and the District of Columbia, 2013.

State laws linked to structural racism changed little from 2010 to 2013 across all 10 legal domains. Although some states amended their laws from year to year, in most instances, amendments did not substantially change the language or effect of the law. Of the 843 state-level laws we examined, only 82 (10%) were amended during the study period; of these amendments, fewer than half altered the law in a substantive way (Table). From 2010 through 2013, most substantive changes pertained to increases in the number of stand-your-ground laws, some undocumented immigrant protection laws, voter identification requirement laws, and some fair-housing laws.

Discussion

Historical and contemporary state laws play an important role in shaping population health and health equity in the United States, 8 -10,27 -31 including the health of people from marginalized racial/ethnic groups and the magnitude of racial/ethnic health inequities. 1,7 -10,12 Our database is the first of which we are aware to provide comprehensive, detailed, and analyzable information on salient contemporary state laws pertaining to 10 legal domains in all 50 states and the District of Columbia from 2010 through 2013. This information will allow researchers to use the tools of legal epidemiology to rigorously evaluate the effect of state laws that are explicitly or implicitly linked to structural racism on the health of people from marginalized racial/ethnic groups and the magnitude of racial/ethnic health inequities in the United States. 24,25 Specifically, our team plans to evaluate the effect of these laws on health outcomes within and across racial/ethnic groups to help inform the development and implementation of evidence-based state laws, policies, and practices that help promote racial and health equity in the United States. Upon completion of these analyses, we will make our database freely available to other researchers to use in their own public health and social science research examining the effect of structural racism–related state laws (individually or in aggregate) on health and health care, economic, and social outcomes and inequities over time. Moreover, we will disseminate our database to policy makers, policy advocates, and community stakeholders at no cost to support state policy initiatives and advocacy efforts that promote racial and health equity. Our database will allow states to compare their structural racism–related state laws with the laws of other states and provide advocates and community stakeholders with the detailed information they need to advocate for laws and policies that help advance racial equity in their state.

We learned several important lessons while developing our comprehensive database of structural racism–related state laws. First, we learned that it is of the utmost importance to develop a detailed protocol to systematically collect accurate information on each legal domain and law. The protocol must then be strictly followed by each legal scholar for each domain and each law across all 50 states and the District of Columbia and in every year to maintain consistent coding. Second, we had some challenges in identifying the most relevant laws in each domain and the most salient aspects of each law, including its effect, enforcement, and remedies. We found that having an interdisciplinary team of both public health researchers with a background in the structural and social determinants of racial/ethnic health inequities and legal scholars with expertise in racial equity was essential to ensuring the relevance and accuracy of our database. In addition, in deciding which laws to include in each legal domain and what aspects of each law to consider, we found that carefully and systematically documenting our rationale, engaging in regular group discussions, and collecting the legal language that supported our decisions (which will be made publicly available along with our database to guide analytic decisions and the interpretation of research findings) were critical in not only identifying the laws that were strongly related to structural racism and capturing the most salient aspects of these laws, but also promoting interrater reliability among the legal scholars coding the laws.

Third, we found that posing and answering a set of theoretically grounded research questions for not only the process of compiling the database as a whole but also for each domain and each law across all states and years was essential for developing a comprehensive database of state laws pertaining to structural racism. Our research questions, which were informed by critical race theory, 13 -16 guided our reading of the laws’ language and provided a consistent foundation to turn to when a law went beyond the scope of interest. Fourth, through the process of compiling the database, we found that a 4-year period did not adequately capture meaningful changes in laws over time. Most states did not amend existing laws during the study period, and among the few states that did, most did not do so in a substantive way. Thus, given the slow pace of legal and policy change, we plan to extend our database to span a longer time frame (eg, 1990 to the present day) in coming years. Lastly, new legal domains relevant to racial equity have emerged since we began developing our database (eg, marijuana legalization and decriminalization laws, which disproportionately affect people from marginalized racial/ethnic groups). 40 Therefore, we will update our database so that it includes information on these more recent legal developments for each state in every year during the extended study period.

Despite modest changes in some protective laws (namely, some undocumented immigrant rights laws and fair-housing laws) from 2010 through 2013, our findings suggest that most states continued to have in place laws that are explicitly or implicitly related to structural racism—including stand-your-ground laws and voter identification requirement laws, which more states instituted during the study period. Legal epidemiology and policy surveillance provide an important framework and tools for identifying the effect of state laws on population health and health equity. 24 -26 By using policy surveillance strategies to collect data on structural racism–related state laws across all 50 states and the District of Columbia over time, our database will provide public health researchers, social scientists, policy makers, and advocates with rigorous evidence to assess states’ legal climates toward marginalized racial/ethnic groups. 25 Using legal epidemiology methods, analysts can then determine their effect on health, economic, and social outcomes within and across racial/ethnic groups. 24,26 In the future, we will link this state-level database to individual-level health outcomes, with the goal of rigorously evaluating the effect of these structural racism–related state laws on health outcomes among marginalized racial/ethnic groups. Together, these efforts will facilitate the development and implementation of evidence-based state laws, policies, and practices that promote racial and health equity and positively contribute to the lives and health of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people, among others, in the United States.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a Harvard Catalyst grant and a Boston Children’s Hospital faculty grant awarded to S.B. Austin and M. Samnaliev. S.B. Austin was supported by the Leadership Education in Adolescent Health project, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration grants T71-MC00009 and T76-MC00001.

ORCID iD

Madina Agénor, ScD, MPH https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6675-8891

References

- 1. Bailey ZD., Krieger N., Agénor M., Graves J., Linos N., Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williams DR., Lawrence JA., Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105-125. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:173-188. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams DR., Priest N., Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407-411. 10.1037/hea0000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williams DR., Yu Y., Jackson JS., Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335-351. 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baah FO., Teitelman AM., Riegel B. Marginalization: conceptualizing patient vulnerabilities in the framework of social determinants of health—an integrative review. Nurs Inq. 2019;26(1):e12268. 10.1111/nin.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gee GC., Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115-132. 10.1017/S1742058X11000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krieger N., Chen JT., Coull BA., Beckfield J., Kiang MV., Waterman PD. Jim Crow and premature mortality among the US Black and White population, 1960-2009: an age-period-cohort analysis. Epidemiology. 2014;25(4):494-504. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krieger N., Jahn JL., Waterman PD. Jim Crow and estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: US-born Black and White non-Hispanic women, 1992-2012. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(1):49-59. 10.1007/s10552-016-0834-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krieger N., Chen JT., Coull B., Waterman PD., Beckfield J. The unique impact of abolition of Jim Crow laws on reducing inequities in infant death rates and implications for choice of comparison groups in analyzing societal determinants of health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2234-2244. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lukachko A., Hatzenbuehler ML., Keyes KM. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:42-50. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Viruell-Fuentes EA., Miranda PY., Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2099-2106. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Delgado R. Critical Race Theory. 3rd ed. New York University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bell DA. Race, Racism and American Law. 6th ed. Aspen Publishers; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higginbotham AL Jr. Review of Race, Racism and American Law by Derrick A. Bell, Jr. Univ Pa Law Rev. 1974;122(4):1044-1069. 10.2307/3311421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bonilla-Silva E. Rethinking racism: toward a structural interpretation. Am Sociol Rev. 1997;62(3):465-480. 10.2307/2657316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pager D., Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34(1):181-209. 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alexander M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People . Born Suspect: Stop-and-Frisk Abuses and the Continued Fight to End Racial Profiling. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; 2014. Accessed October 26, 2020. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/naacp/Born_Suspect_Report_final_web.pdf

- 20. Light CE. Stand Your Ground: A History of America’s Love Affair With Lethal Self-Defense. Beacon Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morris MW. Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools. The New Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Riddle T., Sinclair S. Racial disparities in school-based disciplinary actions are associated with county-level rates of racial bias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(17):8255-8260. 10.1073/pnas.1808307116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gregory JF. The crime of punishment: racial and gender disparities in the use of corporal punishment in U.S. public schools. J Negro Educ. 1995;64(4):454-462. 10.2307/2967267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramanathan T., Hulkower R., Holbrook J., Penn M. Legal epidemiology: the science of law. J Law Med Ethics. 2017;45(1_suppl):69-72. 10.1177/1073110517703329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burris S., Hitchcock L., Ibrahim J., Penn M., Ramanathan T. Policy surveillance: a vital public health practice comes of age. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41(6):1151-1173. 10.1215/03616878-3665931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burris S., Ashe M., Levin D., Penn M., Larkin M. A transdisciplinary approach to public health law: the emerging practice of legal epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37(1):135-148. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burris S. Law in a social determinants strategy: a public health law research perspective. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(suppl 3):22-27. 10.1177/00333549111260S305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burris S., Wagenaar AC., Swanson J., Ibrahim JK., Wood J., Mello MM. Making the case for laws that improve health: a framework for public health law research. Milbank Q. 2010;88(2):169-210. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00595.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raifman J., Moscoe E., Austin SB., McConnell M. Difference-in-differences analysis of the association between state same-sex marriage policies and adolescent suicide attempts. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):350-356. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sabik LM., Tarazi WW., Bradley CJ. State Medicaid expansion decisions and disparities in women’s cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):98-103. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Slater SJ., Nicholson L., Chriqui J., Turner L., Chaloupka F. The impact of state laws and district policies on physical education and recess practices in a nationally representative sample of US public elementary schools. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):311-316. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Komro KA., O’Mara RJ., Wagenaar AC. Mechanisms of Legal Effect: Perspectives From Public Health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Williams DR., Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404-416. 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50068-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. New York Civil Liberties Union . Stop and frisk in the De Blasio era. Accessed August 11, 2020. https://www.nyclu.org/sites/default/files/field_documents/20190314_nyclu_stopfrisk_singles.pdf

- 35. American Civil Liberties Union–District of Columbia . Racial disparities in stops by the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department: review of five months of data. 2020. Accessed August 11, 2020. https://www.acludc.org/sites/default/files/2020_06_15_aclu_stops_report_final.pdf

- 36. Sewell AA., Jefferson KA. Collateral damage: the health effects of invasive police encounters in New York City. J Urban Health. 2016;93(suppl 1):42-67. 10.1007/s11524-015-0016-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. The Policy Surveillance Program . Topics. Accessed February 25, 2020. http://lawatlas.org/topics

- 38. American Civil Liberties Union . Racial justice. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://www.aclu.org/issues/racial-justice

- 39. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People . Issues. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://www.naacp.org/issues

- 40. American Civil Liberties Union . Marijuana legalization is a racial justice issue. Accessed February 25, 2020. https://www.aclu.org/blog/criminal-law-reform/drug-law-reform/marijuana-legalization-racial-justice-issue