Abstract

Using low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) to screen for lung cancer is associated with improved outcomes among eligible current and former smokers (ie, aged 55-77, at least 30-pack–year smoking history, current smoker or former smoker who quit within the past 15 years). However, the overall uptake of LDCT is low, especially in health care settings with limited personnel and financial resources. To increase access to lung cancer screening services, the American Cancer Society partnered with 2 federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in Tennessee and West Virginia to conduct a pilot project focused on developing and refining the LDCT screening referral processes and practices. Each FQHC was required to partner with an American College of Radiology–designated lung cancer screening center in its area to ensure high-quality patient care. The pilot project was conducted in 2 phases: 6 months of capacity building (January–June 2016) followed by 2 years of implementation (July 2016–June 2018). One site created a sustainable LDCT referral program, and the other site encountered numerous barriers and failed to overcome them. This case study highlights implementation barriers and factors associated with success and improved outcomes in LDCT screening.

Keywords: lung cancer, low-dose computed tomography, cancer screening, vulnerable populations, federally qualified health centers

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer diagnosed in both men and women in the United States and the leading cause of death from cancer, with survival rates significantly lower in underserved neighborhoods characterized by low socioeconomic status (SES) than in high SES neighborhoods. 1,2 After the National Lung Screening Trial, conducted from 2002 to 2009, which found that annual screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) was associated with a reduction in lung cancer mortality, 3 several organizations endorsed annual LDCT screening. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends LDCT screening with a “B” rating (indicating certainty that the benefit is moderate to substantial), which meets the standard for coverage as a preventive service under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 4,5 Screening is covered by Medicare for eligible patients (ie, aged 55-77, asymptomatic for lung cancer, smoking history of at least 30-pack–years, and current smoker or former smoker who has quit within the past 15 years). 6 Despite favorable guidelines, health insurance coverage, and evidence that current and former smokers would be willing to be screened if advised by their physician, 7 LDCT screening is still uncommon. In 2015, fewer than 3.9% of the eligible population reported receiving LDCT screening. 8

Although screening rates have likely increased since 2015, formidable patient, health care provider, and system barriers have contributed to the slow uptake of LDCT screening. 9 -11 Many eligible adults are unaware of screening or whether their health insurance will cover it, and half of eligible adults report they are uninsured or have Medicaid. 8 Likewise, many health care providers are unaware of screening guidelines or may not be prepared to deliver informed and shared decision making, refer patients to screening, or address positive screening results and incidental findings in a time-limited primary care setting. 12,13 Furthermore, electronic health records (EHRs), which could help identify eligible patients, often do not include qualifying details about smoking history and, when they do, details may be inaccurate. 14 Given time pressures and the lack of ease and readiness to implement lung cancer referrals and manage follow-up, LDCT screening has not been prioritized in most primary care settings. These and other barriers are prevalent in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). 15

Most lung cancer care in the United States is provided in a community setting, 16 and 1 in 12 people in the United States are served through community health centers, which provide a medical home to people often facing barriers to care. 17 FQHCs receive federal funding and are required to provide services on a sliding-fee scale based on ability to pay. About 1400 FQHCs with 12 000 sites serve more than 28 million people. 18 These patients tend to be uninsured or publicly insured: 49% of patients receive Medicaid, and 24% of patients do not have health insurance. 19

In 2015, the American Cancer Society (ACS) launched the Health Center Advancing Lung Cancer Early Detection (HALE) pilot program in 2 FQHCs to improve access to LDCT screening. We describe the HALE program, how it was implemented, and the key facilitators and barriers to implementation of LDCT screening. Lessons learned from this pilot can inform future LDCT screening interventions in FQHCs.

Methods

The HALE program focused on developing and refining processes for screening in 2 locations with high rates of lung cancer mortality: a rural site in West Virginia, a Medicaid expansion state (Site A), and an urban site in Tennessee, a non–Medicaid expansion state (Site B). ACS invited 1 FQHC in each location to participate in the program and required each FQHC to partner with an American College of Radiology–designated lung cancer screening center in its area to ensure high-quality patient care. ACS conducted the program in 2 phases: capacity building (January–June 2016) and implementation (July 2016–June 2018). ACS provided funding and technical support for implementation, and Site B also received funds to pay for screenings for uninsured patients.

Capacity-Building Phase

During the 6-month capacity-building phase (2016), ACS convened in-person meetings with each FQHC and screening center to provide training on lung cancer, LDCT screening, eligibility criteria, and shared decision making. ACS also provided sites with targeted education materials.

ACS encouraged each site to establish a team with clinical champions and navigators, develop a work plan, and map processes. With ACS consultation on best practices, FQHCs and screening centers developed processes to identify eligible patients (ie, age 55-77, 30-pack–year smoking history, current smoker or quit within past 15 years), provide screening education, help patients make informed decisions, and refer and navigate patients through screening and follow-up. Sites also attempted to establish baseline data for current and former smokers, screening rates, and referrals to tobacco cessation programs and resources.

Implementation Phase

Implementation of the screening intervention occurred during 2 years (2016-2018). Sites modified work plans and interventions as needed, with a focus on process improvement. Throughout the implementation, ACS staff members provided technical assistance and participated in joint meetings between FQHCs and screening centers to discuss and overcome challenges and identify opportunities for quality improvement.

Monitoring and Evaluation

ACS evaluators monitored program activities throughout implementation. Sites submitted quarterly reports on the number of patients referred and screened, with narrative information on implementation barriers and accomplishments. Evaluators also conducted annual site visits and conducted in-person interviews with key personnel to further explore facilitators and barriers to implementation.

Outcomes

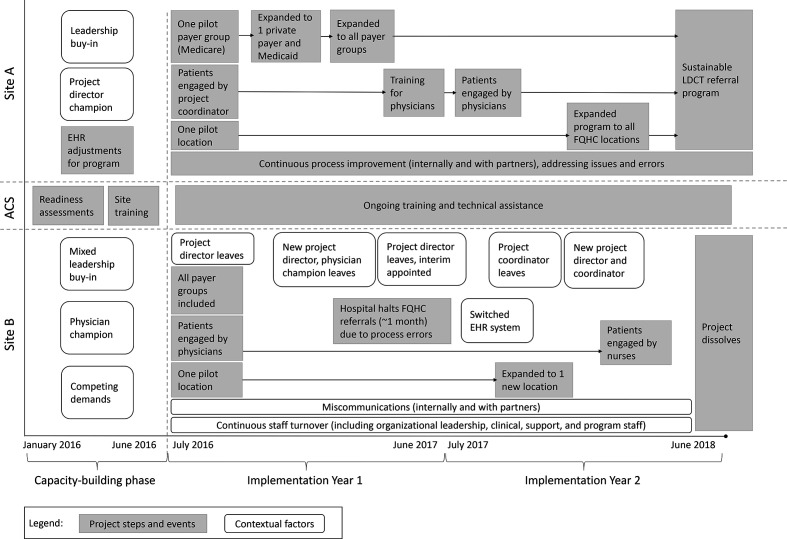

Sites had autonomy in how they implemented their program and, ultimately, both sites took different approaches and encountered different facilitators and barriers throughout the pilot (Figure). These approaches included intentional programmatic steps and contextual factors that influenced program outcomes.

Figure.

Implementation of a low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) lung cancer screening program at 2 pilot sites, each consisting of a federally qualified health center (FQHC) and an American College of Radiology–designated lung cancer screening center, West Virginia (Site A) and Tennessee (Site B), 2016-2018. Abbreviations: ACS, American Cancer Society; EHR, electronic health record.

Site A established a sustainable referral program, but Site B did not and discontinued its program. We identified key facilitators and barriers associated with program success (Table). A detailed description of each site’s implementation processes and key facilitators and barriers is provided hereinafter.

Table.

Summary of notable facilitators and barriers to implementation of a low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening program at 2 pilot sites in West Virginia (Site A) and Tennessee (Site B), 2016-2018 a

| Domain | Site A | Site B |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation process | Facilitators:

Barrier:

|

Barriers:

|

| FQHC context | Facilitators:

|

Barriers:

|

| Staff member engagement | Facilitators:

Barrier:

|

Facilitator:

Barriers:

|

| Partner relations | Facilitator:

|

Barriers:

|

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; FQHC, federally qualified health center.

aEach pilot site consisted of an FQHC and an American College of Radiology–designated lung cancer screening center.

Site A

Implementation process

Site A took a careful stepwise approach to implementation. The program began in a single clinic location where a team of 2—a project champion and coordinator—conducted all program activities. They focused on a single payer group (Medicare) and the project coordinator handled all patient engagement. They troubleshot all referral and payment issues for Medicare patients, and once the process was operating smoothly, they expanded the program to include other payer groups sequentially until all payer groups were included. This process was time-consuming, taking almost a year before processes for all payer groups were established and initial barriers were resolved. Toward the end of the first year, the initial team trained primary care providers at a single clinic location and transitioned to health care provider–initiated referrals. The project champion and coordinator addressed emerging health care provider–level barriers, and when the provider referral system was operating smoothly at that location, they expanded to other clinic sites in the middle of the second year.

FQHC context

Site A’s FQHC had considerable experience handling lung disease in its patient population and had an on-site breathing center that provided respiratory therapy. Its EHR also included useful features that could be activated at program outset, such as tracking of pack-year smoking history and flagging potentially eligible patients.

Staff member engagement

The FQHC secured endorsement from its administration, although some health care providers were initially skeptical about LDCT screening and concerned about false-positive test results. A respiratory therapist from the breathing center was an enthusiastic project champion, however, and the stepwise implementation process enabled the FQHC to resolve challenges and share data on screening results and success stories from its own patient population with health care providers before asking them to conduct referrals themselves. This process was well-received by health care providers; seeing their patients’ data improved their acceptance of the program and confidence in screening.

Partner relations

The FQHC and screening center held regular meetings to address challenges, which ensured they had opportunities to address barriers before they escalated or created stress between partners. They structured their discussions on specific patient cases to keep health care providers focused on their shared goal of improving patient care.

Outcomes

Site A screened 263 patients; 59 had abnormal screening results that warranted follow-up, 5 of whom were diagnosed with lung cancer. Site A established a sustainable program and maintained a positive working relationship with the screening center to address challenges as they emerged.

Site B

Implementation process

Although Site A took a year to implement screening referrals across all payer groups and health care providers within a single clinic location, Site B implemented rapidly from the outset and encouraged all staff members in a single clinic location to refer any eligible patients regardless of health insurance (ie, Medicare, Medicaid, private insurer, no insurance). This “all-in” approach resulted in staff members encountering multiple challenges simultaneously, which created frustration and diminished their interest in participation.

In year 2, the FQHC expanded to an additional clinic location to reach more eligible patients. The 2 clinic locations had little communication about lessons learned for successful implementation. Consequently, the second clinic experienced similar challenges to those at the initial clinic, which could have been avoided.

FQHC context

At the project outset, Site B’s FQHC was seeking accreditation as a patient-centered medical home and transitioning to a new EHR system. These are long-term, resource-intensive processes, and FQHC leadership expressed concern that participating in the HALE program, a lesser priority, would further strain their limited resources. Importantly, the EHR transition also precluded the FQHC from making systems modifications to enable the identification of eligible patients and tracking referrals and results.

Staff member engagement

The FQHC began with strong support from a physician champion but struggled to gain support from key administrative leaders who had competing demands. Soon after FQHC leadership decided to move forward with the pilot, the physician champion and other enthusiastic leaders left, resulting in a new leadership structure that was less supportive of the HALE program. Staff turnover continued at the clinical and administrative levels throughout the pilot, making it difficult for the program to achieve success through consistent support and management. Furthermore, initially enthusiastic staff members expressed frustration and diminished interest after encountering weak administrative support and numerous challenges with referrals.

Partner relations

The FQHC and screening center did not establish a consistent system for communication and referrals. Ad hoc meetings between partners allowed challenges to grow substantially before they were addressed. At one point, the screening center team became frustrated, temporarily halted the program, and refused to accept screening referrals from the FQHC until process issues were resolved. The FQHC worked with the screening facility to improve processes, and the program resumed, but partner relations were strained going forward.

Outcomes

Site B screened 57 patients, 10 of whom had abnormal screening results requiring follow-up; none were diagnosed with lung cancer at the time the pilot concluded. Based on the numerous barriers identified previously, the FQHC ultimately decided it was not the right time to implement an LDCT screening program and discontinued the effort.

Lessons Learned

Although numerous studies have examined the effectiveness of LDCT screening 20 and the literature on patient-level barriers to screening is growing, 21,22 minimal data are available on systems-level facilitators and barriers to implementing LDCT referrals across health care delivery settings and patient groups. Although our case study was limited to 2 FQHCs that were unique in both their implementation strategies and contextual factors affecting implementation, it provides insight into challenges and successes FQHCs may experience when initiating LDCT screening programs. Although the experiences of the 2 FQHCs may not be generalizable to all FQHCs, 3 best practices could be used in other settings that want to implement LDCT screenings.

First, assess conditions within the FQHC and carefully consider if it is an appropriate time to initiate LDCT referrals. Establishing an LDCT screening program is a complex process, especially in limited-resource settings. Based on the challenges experienced by Site B, we recommend that FQHCs consider the following: (1) assessing data on smoking history currently captured in the EHR, (2) assessing the extent to which the EHR is modifiable, (3) evaluating current staff capacity, (4) ensuring the availability of a dedicated project coordinator, and (5) weighing other ongoing commitments that require clinic time and resources. If circumstances are not favorable, it may be better to delay initiation than to partially execute a program, which may discourage health care provider participation in the long term or leave patients vulnerable to gaps in the care continuum.

Second, FQHCs should consider using a stepwise implementation approach, whereby new processes are tested slowly rather than introducing many new processes simultaneously across a range of staff members, payer groups, and patients. If staff member resources and time are limited, it may still be advisable to begin implementation with a small number of enthusiastic staff members who are committed to problem solving in the early stages of the program. This approach could generate program and patient successes that could lead to clinician buy-in. Beginning with a small number of referrals and following those patients through screening completion is also likely beneficial, and any problems related to referrals, scheduling, or reimbursement can be resolved without affecting other patients.

Third, FQHCs should prioritize open communication with screening facilities. Our data suggest that partners should assume that challenges will emerge and establish open lines of communication and a culture of patient-centric constructive feedback to address them. This approach will enable partners to resolve challenges as they emerge and may promote effective and positive long-term relationships.

This project provides useful insight into barriers and facilitators FQHCs can expect to encounter when implementing lung cancer screening programs. Each FQHC is unique and faces different challenges; thus, a thorough needs and capacity assessment should be conducted before implementing a time- and resource-intensive LDCT screening intervention. Future research should explore these findings and recommendations with a larger, more diversified sample of health centers to provide further insight into factors that affect implementation in other contexts.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Michelle Chappell, Morgan Daven, Kelly Durden, Beth Dickson-Gavney, Wynett Jones, Debbie Kirkland, Mary Lough, Kara Riehman, Kevin Tephabock, and Letitia Thompson for their support of the HALE pilot and evaluation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Katherine Sharpe has served as a consultant for Genentech for work not related to the topic of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The pilot project was funded in part by a grant from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation.

ORCID iD

Lesley Watson, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0279-728X

References

- 1. Siegel RL., Miller KD., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. 10.3322/caac.21551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singh GK., Jemal A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950-2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017(138):1-19. 10.1155/2017/2819372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle DR, Adams AM. et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409. 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moyer VA. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330-338. 10.7326/M13-2771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub L No 111-148 (2010).

- 6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Decision memo for screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). Accessed August 4, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274

- 7. Delmerico J., Hyland A., Celestino P., Reid M., Cummings KM. Patient willingness and barriers to receiving a CT scan for lung cancer screening. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(3):307-309. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jemal A., Fedewa SA. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in the United States—2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):1278-1281. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wender RC., Brawley OW., Fedewa SA., Gansler T., Smith RA. A blueprint for cancer screening and early detection: advancing screening’s contribution to cancer control. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):50-79. 10.3322/caac.21550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brenner AT., Cubillos L., Birchard K. et al. Improving the implementation of lung cancer screening guidelines at an academic primary care practice. J Healthc Qual. 2018;40(1):27-35. 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang GX., Baggett TP., Pandharipande PV. et al. Barriers to lung cancer screening engagement from the patient and provider perspective. Radiology. 2019;290(2):278-287. 10.1148/radiol.2018180212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Simmons VN., Gray JE., Schabath MB., Wilson LE., Quinn GP. High-risk community and primary care providers knowledge about and barriers to low-dose computed topography lung cancer screening. Lung Cancer. 2017;106:42-49. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lewis JA., Petty WJ., Tooze JA. et al. Low-dose CT lung cancer screening practices and attitudes among primary care providers at an academic medical center. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(4):664-670. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Modin HE., Fathi JT., Gilbert CR. et al. Pack-year cigarette smoking history for determination of lung cancer screening eligibility. Comparison of the electronic medical record versus a shared decision-making conversation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(8):1320-1325. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-984OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zeliadt SB., Hoffman RM., Birkby G. et al. Challenges implementing lung cancer screening in federally qualified health centers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(4):568-575. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fischel RJ., Dillman RO. Developing an effective lung cancer program in a community hospital setting. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10(4):239-243. 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Health Resources and Services Administration . Health center program: impact and growth. Accessed October 6, 2019. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/healthcenterprogram/index.html

- 18. Health Resources and Services Administration . HRSA health center program. Accessed October 6, 2019. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bphc/about/healthcenterfactsheet.pdf

- 19. National Association of Community Health Centers . Community health center chartbook. Accessed October 6, 2019. http://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Chartbook2017.pdf

- 20. Humphrey LL., Deffebach M., Pappas M., Zakher B., Slatore CG. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):212. 10.7326/L14-5003-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carter-Harris L., Ceppa DP., Hanna N., Rawl SM. Lung cancer screening: what do long-term smokers know and believe? Health Expect. 2017;20(1):59-68. 10.1111/hex.12433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tonge JE., Atack M., Crosbie PA., Barber PV., Booton R., Colligan D. “To know or not to know…?” Push and pull in ever smokers lung screening uptake decision‐making intentions. Health Expect. 2019;22(2):162-172. 10.1111/hex.12838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]