Abstract

Objective

We quantified the association between public compliance with social distancing measures and the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the first wave of the epidemic (March–May 2020) in 5 states that accounted for half of the total number of COVID-19 cases in the United States.

Methods

We used data on mobility and number of COVID-19 cases to longitudinally estimate associations between public compliance, as measured by human mobility, and the daily reproduction number and daily growth rate during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York.

Results

The 5 states mandated social distancing directives during March 19-24, 2020, and public compliance with mandates started to decrease in mid-April 2020. As of May 31, 2020, the daily reproduction number decreased from 2.41-5.21 to 0.72-1.19, and the daily growth rate decreased from 0.22-0.77 to –0.04 to 0.05 in the 5 states. The level of public compliance, as measured by the social distancing index (SDI) and daily encounter-density change, was high at the early stage of implementation but decreased in the 5 states. The SDI was negatively associated with the daily reproduction number (regression coefficients range, –0.04 to –0.01) and the daily growth rate (from –0.009 to –0.01). The daily encounter-density change was positively associated with the daily reproduction number (regression coefficients range, 0.24 to 1.02) and the daily growth rate (from 0.05 to 0.26).

Conclusions

Social distancing is an effective strategy to reduce the incidence of COVID-19 and illustrates the role of public compliance with social distancing measures to achieve public health benefits.

Keywords: public compliance, social distancing, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, impact assessment

The United States has become one of the epicenters of the COVID-19 epidemic. During the first wave of the epidemic (March–May 2020), 1 798 640 people were infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Five states—California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York—had the highest number of SARS-CoV-2 cases, accounting for 49.2% of all cases in the United States. The epidemic resurged in many states in a second wave of the epidemic starting in June 2020. 1

In response to the growing number of cases in late March 2020, all 5 state governments implemented stay-at-home directives to limit physical contact and reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission and mortality. Such measures included bans on large events and closures of schools, entertainment venues, and nonessential businesses. Social distancing is a mitigation strategy that slows the spread and intensity of the epidemic and flattens the epidemic curve. 2 As a result of these public health interventions, the number of reported people infected with SARS-CoV-2 declined. 3 During May–June 2020, the stay-at-home directives were lifted in the 5 states, and businesses gradually reopened. Despite guidance to continue social distancing, public compliance waned and may have contributed to a second wave of infections. However, few studies have quantitatively measured the role of public compliance as a key determinant of social distancing success and its effect on the COVID-19 epidemic.

Human mobility data collected by innovative methods can objectively measure public compliance with social distancing recommendations in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic. 4 To fill the research gap, we used data on the epidemic and human mobility from 5 states with high COVID-19 incidence to assess the level of public compliance with social distancing measures. We also examined longitudinal changes in human mobility patterns to determine whether compliance with social distancing guidance predicted viral transmissibility, as measured by the daily reproduction number (Rt ), and the speed of COVID-19 spread, as estimated by the daily growth rate, during the first wave of the epidemic.

Methods

Study Sample and Data

The implementation dates of the stay-at-home directives varied by state, and we collected information on these dates from state government websites. We downloaded state-level data for the number of people with SARS-CoV-2 from The New York Times. 1 We limited our analysis to the first wave of the epidemic (March–May 2020) to reduce potential confounding as a result of the lifting of the stay-at-home directives and reopening of businesses that started in May and June in the 5 states (California: May 25, 2020; Illinois: May 29, 2020; Massachusetts: May 18, 2020; New Jersey: June 9, 2020; and New York: May 29, 2020).

To proximally measure changes in compliance with social distancing measures, we measured human mobility by using 2 indices: the social distancing index (SDI) and daily encounter-density change. We downloaded data for the 2 indices from the University of Maryland COVID-19 Impact Analysis Platform 5 and the Unacast Social Distancing Scoreboard. 6

Measures

The daily encounter-density change measures the percentage change in the number of encounters compared with the pre-epidemic national baseline. A potential human encounter is defined by the space between 2 mobile phone devices (≤50 m) and time (≤60 minutes). The national average daily encounter density is calculated by the baseline measurement preceding the COVID-19 outbreak (February 10–March 8, 2020). 6 A daily encounter-density change >0 indicates that human mobility is greater than the pre-epidemic national baseline, whereas values <0 suggest that human mobility is less than the national baseline. The value of 0 indicates that human mobility is the same as the national baseline. The daily encounter-density change is normalized by encounters per km2 to account for the difference between densely populated urban areas and less-populated rural areas. 7

The SDI uses mobile device location data from multiple sources (ie, population census data and location data from cell phones and vehicles: road, rail, bus, and airline system data sets) to discriminate between person movement and vehicle movement. 5 The SDI score ranges from 0 to 100 and measures the extent to which area residents and visitors practice social distancing. A value of 0 indicates no social distancing, and 100 indicates perfect social distancing. SDI scores were compared with the benchmark, which was computed by using weekday data (Monday through Friday) during the first 2 weeks of February, just days before the COVID-19 outbreak. 8

Statistical Analysis

We estimated incidence risk by dividing the cumulative number of people with SARS-CoV-2 by the population in each state. The daily reproduction number (Rt ) measures the level of viral transmissibility. 9 The value of Rt represents the average number of people infected by a primary person with SARS-CoV-2 at time t. We used a serial interval of 4.17 (SD = 2.9) days and 7-day moving averages of the daily number of SARS-CoV-2 cases to estimate Rt . 10 Other investigators have also used this serial interval in their studies. 11,12 We used infection data after at least 1 serial interval (5 days from the start of the epidemic) or when ≥12 infected people had been reported to take into account any initial inaccuracies in reporting at the start of the epidemic. An Rt value >1 indicates ongoing spread of the virus, and a value <1 denotes reduced viral spread. Rt values offer a daily indication of whether an epidemic is growing or declining and have been used to monitor intervention effects in real time. 9,13

The daily growth rate measures the speed at which the epidemic is spreading. 14 We used the number of reported infections per day to estimate daily growth rates on a 7-day moving average by using an established formula: yt = y(t - 1) (1 + r). Here, yt is the number of reported infected people on the current day t; y(t - 1) denotes the number of daily infected people on the previous day (t − 1); and r is the daily growth rate. When the number of daily infected people increases, the daily growth rate is >0. For example, if r = 0.25, the number of infected people is 25% more than that reported on the previous day. When a growth rate is <0, the number of daily infected people declines.

We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to assess whether the means of the 2 mobility indices increased or decreased in an ordered time frame. We used the “proc npar1way” in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) to perform this test. We used autoregression models to analyze associations between mobility measures (independent variables) and the daily reproduction number and daily growth rate (dependent variables) using the “proc autoreg” procedure in SAS to account for the correlated nature of time-series data. 15 Regression coefficients indicate the strength of associations between dependent and independent variables, and we estimated them with maximum likelihood estimation and without other covariates because of the nature of a time-series analysis and ecological study design. Given an incubation period of 5-14 days for COVID-19, 16 we used a 10-day lag to estimate associations. Diagnostic tests determined that 6 lags were sufficient to account for the autocorrelation of errors. The total R 2 statistic computed from the autoregressive model reflects the improved fit from the use of past residuals to predict the next value of the dependent variable. It is a measure of how well the next value can be predicted using the structural part of the model and the past values of the residuals. 17

Because this study was a secondary analysis of publicly available data and no patients were involved, institutional review board review was not needed.

Results

Daily Reproduction Number and Daily Growth Rate

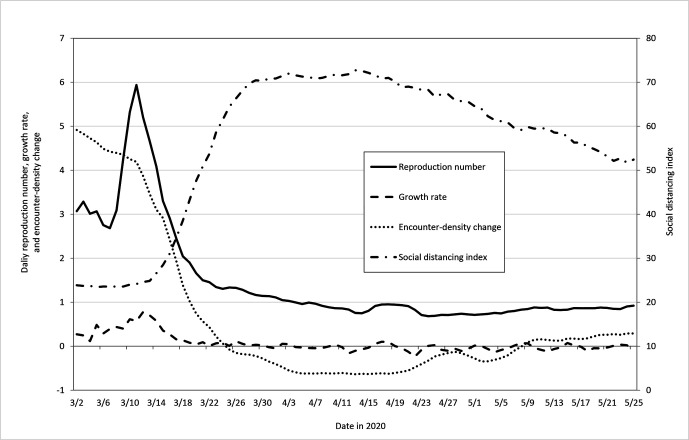

As of May 31, 2020, the incidence risk of COVID-19 was 1.9% in New York (375 575/19 453 561), 1.8% in New Jersey (160 445/8 882 190), 1.4% in Massachusetts (96 965/6 892 503), 1.0% in Illinois (120 588/12 671 821), and 0.3% in California (113 114/39 512 223). The daily reproduction number and daily growth rate declined in all 5 states during the study period (Table 1, Figure). One day before the social distancing directive was implemented, the daily reproduction number was 5.21 in New York, 4.21 in Illinois, 4.14 in New Jersey, 2.41 in Massachusetts, and 2.41 in California (Table 1). As of May 31, the daily reproduction number declined to 0.85 in New York, 0.72 in Illinois, 0.92 in New Jersey, 0.76 in Massachusetts, and 1.19 in California. Similarly, the daily growth rates declined from 0.77 to 0.01 in New York, from 0.47 to −0.01 in New Jersey, from 0.44 to −0.04 in Illinois, from 0.40 to 0.02 in Massachusetts, and from 0.22 to 0.05 in California.

Table 1.

Daily reproduction number and daily growth rate in the COVID-19 epidemic before and after the stay-at-home directive, 5 states, March–May 2020 a

| State | Date of directive | Daily reproduction number (95% credible interval) | Daily growth rate (95% confidence interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 day before directive | May 31, 2020 | 1 day before directive | May 31, 2020 | ||

| New York | March 22 | 5.21 (5.10 to 5.31) | 0.85 (0.83 to 0.86) | 0.77 (0.69 to 0.85) | 0.01 (−0.04 to 0.06) |

| New Jersey | March 21 | 4.14 (3.86 to 4.42) | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.94) | 0.47 (0.33 to 0.61) | –0.01 (−0.06 to 0.04) |

| Illinois | March 21 | 4.21 (3.86 to 4.57) | 0.72 (0.71 to 0.73) | 0.44 (0.38 to 0.50) | −0.04 (−0.09 to 0.01) |

| Massachusetts | March 24 | 2.41 (2.21 to 2.61) | 0.76 (0.74 to 0.78) | 0.40 (0.32 to 0.47) | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.06) |

| California | March 19 | 2.41 (2.24 to 2.60) | 1.19 (1.18 to 1.21) | 0.22 (0.20 to 0.24) | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.08) |

aData source: The New York Times coronavirus (COVID-19) data in the United States. 1

Figure.

Seven-day moving average trends of the daily reproduction number, daily growth rate, daily encounter-density change, and social distancing index (SDI) in New York during the COVID-19 epidemic, March–May 2020. The stay-at-home directive began on March 21, 2020. A 10-day lag was incorporated in the trend analysis of the COVID-19 spread and human mobility. The SDI uses mobile device location data from multiple sources (ie, population census data and location data from cell phones and vehicles) to discriminate between person movement and vehicle movement. The SDI score ranges from 0 to 100 and measures the extent to which area residents and visitors practice social distancing. A value of 0 indicates no social distancing, and 100 indicates perfect social distancing. The daily encounter-density change measures the percentage change in the number of encounters compared with the pre-epidemic national baseline. A potential human encounter is defined by the space between 2 mobile phones (≤50 m) and time (≤60 minutes). A daily encounter-density change >0 indicates that human mobility is greater than the pre-epidemic national baseline, whereas values <0 suggest that mobility activity is less than the national baseline. A value of 0 indicates that mobility is the same as the national baseline.

Human Mobility Before and After Social Distancing

After the stay-at-home directive was implemented in the 5 states, the SDI increased and the daily encounter-density change declined. However, starting in mid-April, public compliance declined in all 5 states: the SDI decreased and the daily encounter-density change increased (Table 2, Figure; data for other states are available from the authors). For example, the value of the SDI 1 day before the directive was implemented (March 21) in New York was 35.6. On April 14, the SDI increased to 71.1 and then declined. The daily encounter-density change was 2.56 one day before the directive. After the directive, the daily encounter-density change decreased below the national baseline but then returned to above the pre-epidemic national baseline starting on May 9.

Table 2.

Mean of social distancing index and daily encounter-density change before and after the stay-at-home directive during the COVID-19 epidemic in 5 states, 2020 a

| State | Social distancing index b | Daily encounter-density change d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value | P value for trend c | Mean value | P value for trend c | |

| New York (date of directive March 22) | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| March 21 | 35.6 | 2.56 | ||

| March 22–April 1 | 70.1 | −0.34 | ||

| April 2-11 | 71.2 | −0.61 | ||

| April 12-21 | 70.7 | −0.59 | ||

| April 22–May 1 | 64.6 | −0.21 | ||

| May 2-11 | 60.4 | 0.03 | ||

| May 12-21 | 53.6 | 0.22 | ||

| May 22-31 | 50.5 | 0.32 | ||

| New Jersey (date of directive March 21) | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| March 20 | 32.9 | 6.14 | ||

| March 21-31 | 70.1 | 0.66 | ||

| April 1-10 | 68.6 | 0.28 | ||

| April 11-20 | 70.2 | 0.23 | ||

| April 21-30 | 64.5 | 1.17 | ||

| May 1-10 | 58.5 | 1.68 | ||

| May 11-20 | 53.1 | 2.27 | ||

| May 21-31 | 49.6 | 2.78 | ||

| Illinois (date of directive March 21) | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| March 20 | 26.9 | 0.82 | ||

| March 21-31 | 60.6 | –0.57 | ||

| April 1-10 | 55.5 | −0.62 | ||

| April 11-20 | 58.2 | −0.62 | ||

| April 21-30 | 50.5 | −0.40 | ||

| May 1-10 | 44.6 | −0.20 | ||

| May 11-20 | 42.5 | −0.14 | ||

| May 21-31 | 36.1 | 0.04 | ||

| Massachusetts (date of directive March 24) | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| March 23 | 33.1 | 2.01 | ||

| March 24–April 2 | 64.2 | −0.29 | ||

| April 3-12 | 66.4 | −0.52 | ||

| April 13-22 | 63.4 | −0.43 | ||

| April 23−May 2 | 58.6 | –0.11 | ||

| May 3-12 | 53.7 | 0.17 | ||

| May 13-22 | 45.1 | 0.36 | ||

| May 23-31 | 43.6 | 0.47 | ||

| California (date of directive March 19) | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| March 18 | 23.6 | 0.27 | ||

| March 19-28 | 57.0 | −0.70 | ||

| March 29−April 7 | 61.8 | −0.83 | ||

| April 8-17 | 59.3 | −0.82 | ||

| April 18-27 | 57.2 | −0.70 | ||

| April 28−May 7 | 49.3 | −0.68 | ||

| May 8-17 | 46.9 | −0.56 | ||

| May 18-27 | 42.1 | −0.55 | ||

| May 28-31 | 40.8 | −0.52 | ||

aData source: The New York Times coronavirus (COVID-19) data in the United States. 1

bThe social distancing index (SDI) uses mobile device location data from multiple sources (ie, population census data and location data from cell phones and vehicles) to discriminate between person movement and vehicle movement. The SDI score ranges from 0 to 100 and measures the extent to which area residents and visitors practice social distancing. A value of 0 indicates no social distancing, and 100 indicates perfect social distancing.

c P value for time trend determined by the Kruskal–Wallis test. P < .05 was considered significant.

dThe daily encounter-density change measures the percentage change in the number of encounters compared with the pre-epidemic national baseline. A potential human encounter is defined by the space between 2 mobile phones (≤50 m) and time (≤60 minutes). A daily encounter-density change >0 indicates that human mobility is greater than the pre-epidemic national baseline, whereas values <0 suggest that mobility activity is less than the national baseline. A value of 0 indicates that mobility is the same as the national baseline.

Associations of Public Compliance Measured by Human Mobility With the Daily Reproduction Number and Daily Growth Rate

The daily encounter-density change was significantly and positively associated with the daily reproduction number (regression coefficients range, 0.24-1.02) and the daily growth rate (regression coefficients range, 0.05-0.26) in the 5 states (Table 3). The SDI was significantly and negatively associated with the daily growth rate (regression coefficients range, −0.009 to −0.01) and the daily reproduction number (regression coefficients range, −0.04 to −0.01), with the exception of 1 nonsignificant association in Massachusetts (coefficient: −0.01; P = .24).

Table 3.

Associations between public compliance with social distancing measured by 2 mobility indices with the daily reproductive number (R 2) and daily growth rate during the COVID-19 epidemic in 5 states, 2020 a

| State | Daily reproduction number | Daily growth rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient b (95% CI) | P value c | Total R 2 | Coefficient d (95% CI) | P value c | Total R 2 | |

| New York | ||||||

| Daily encounter-density change | 0.48 (0.24 to 0.72) | <.001 | 0.99 | 0.13 (0.11 to 0.15) | <.001 | 0.90 |

| SDI | −0.03 (−0.054 to −0.004) | .02 | 0.99 | −0.01 (−0.02 to −0.01) | <.001 | 0.88 |

| New Jersey | ||||||

| Daily encounter-density change | 0.24 (0.16 to 0.31) | <.001 | 0.98 | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.07) | <.001 | 0.71 |

| SDI | −0.04 (−0.06 to −0.03) | <.001 | 0.98 | −0.008 (−0.011 to −0.005) | <.001 | 0.71 |

| Illinois | ||||||

| Daily encounter-density change | 1.02 (0.48 to 1.55) | <.001 | 0.97 | 0.26 (0.08 to 0.43) | .003 | 0.50 |

| SDI | −0.03 (−0.05 to −0.01) | .002 | 0.97 | −0.009 (−0.015 to −0.004) | .002 | 0.51 |

| Massachusetts | ||||||

| Daily encounter-density change | 0.34 (0.03 to 0.65) | .03 | 0.97 | 0.06 (0.01 to 0.12) | .03 | 0.78 |

| SDI | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.01) | .24 | 0.96 | −0.003 (−0.012 to −0.002) | .01 | 0.79 |

| California | ||||||

| Daily encounter-density change | 0.76 (0.44 to 1.07) | <.001 | 0.98 | 0.19 (0.15 to 0.24) | <.001 | 0.60 |

| SDI | −0.02 (−0.04 to −0.01) | <.001 | 0.98 | −0.006 (−0.008 to −0.004) | <.001 | 0.57 |

Abbreviation: SDI, social distancing index.

aData source: The New York Times coronavirus (COVID-19) data in the United States. 1

bThe SDI uses mobile device location data from multiple sources (ie, population census data and location data from cell phones and vehicles) to discriminate between person movement and vehicle movement. The SDI score ranges from 0 to 100 and measures the extent to which area residents and visitors practice social distancing. A value of 0 indicates no social distancing, and 100 indicates perfect social distancing.

c P value of t statistics for regression coefficients. P < .05 was considered significant.

dThe daily encounter-density change measures the percentage change in the number of encounters compared with the pre-epidemic national baseline. A potential human encounter is defined by the space between 2 mobile phones (≤50 m) and time (≤60 minutes). A daily encounter-density change >0 indicates that human mobility is greater than the pre-epidemic national baseline, whereas values <0 suggest that mobility activity is less than the national baseline. A value of 0 indicates that mobility is the same as the national baseline.

Discussion

The findings of this study document that voluntary public compliance with social distancing measures may have determined their effect on reducing viral transmissibility and the speed at which COVID-19 spreads. Public compliance started to decline in mid-April in the 5 states, as indicated by an increase in human mobility patterns. The second wave of the epidemic in the United States starting in June 2020 may have resulted from a combination of premature reopening of businesses, lifting of the stay-at-home directive, and reduced public compliance with the governmental directives. Our study provides a timely evaluation of social distancing measures in the context of an ongoing resurgence of the epidemic after states reopened businesses and the public became less amenable to social distancing measures.

One day before implementation of the directives, the daily reproduction number ranged from 2.41 to 5.21 in the 5 states; in other words, on average, 1 person with the virus infected 2-5 other people during the infectious period. This result coupled with a daily growth rate >0 suggests the possibility for exponential spread in the absence of intervention measures. After the stay-at-home directives were implemented, both the level of viral transmissibility and the speed at which the epidemic spread declined, signifying that the scope of the epidemic had been reduced in the 5 states. This finding suggests that social distancing is an important public health measure for mitigating the spread of COVID-19. Furthermore, social distancing measures may improve other public health interventions by making testing and contact tracing more manageable. Although the reduction of infection risk may also have resulted from other prevention measures (testing, contact tracing, personal hygiene), social distancing measures likely played an important role. Other empirical studies have also reported the preventive effects documented in our study. 18,19 Without an effective vaccine, social distancing is a practical, feasible, and effective measure to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

However, community-level implementation of social distancing measures can be effective only with extensive voluntary participation. To quantitatively examine the level of public compliance with social distancing guidelines, we purposely selected 2 quantitative mobility indices as a proxy measure of public compliance from 2 independent developers. Both the SDI and daily encounter-density change appropriately predicted changes in the daily reproduction number and daily growth rate after a 10-day lag. Although the strength of associations measured by the autoregression coefficients varied in the 5 states, all but 1 association (the nonsignificant association between the SDI and Rt in Massachusetts) was in the expected direction and significant, suggesting that higher levels of public compliance with the directives, measured by human mobility, may reduce the levels of the daily reproduction number and daily growth rate. To maximize the effectiveness of social distancing measures, it is important to change the public’s attitudes toward these measures and improve their compliance. Although it is not clear what factors influence the public’s compliance with social distancing measures, possible explanations include misunderstanding the directives, 20 political beliefs, 21 mistrust in science, 22 stigma, 23 low levels of motivation, 24 and concerns about loss of household income. 25 Limited research has used cross-sectional data to investigate public compliance with preventive measures during the COVID-19 epidemic in China, 24 Israel, 25 and Tanzania. 26

In theory, social distancing measures reduce the daily reproduction number and daily growth rate by limiting physical contact and reducing transmissibility of the virus. However, social distancing does not remove the sources of infection (symptomatic, presymptomatic, and asymptomatic infectious people) from the community. 2 If social distancing measures are relaxed prematurely and daily activities that promote physical contact resume, the risk of acquiring or transmitting the virus will increase because most of the population is still susceptible to viral infection. Although the daily reproduction number declined in the 5 states, it did not decline to 0.3 as it did in Wuhan, China, 27 where the epidemic is currently under control. In fact, the daily reproduction number was still high in the 5 states (range, 0.72-1.19) and the daily growth rate was >0 in 3 states as of May 31, 2020. Human mobility declined when social distancing measures were implemented about 30 days after the directives, indicating a high level of public compliance. However, public compliance diminished in mid-April in the 5 states, and the 2 mobility indices started to rise. Given that most people are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection and that the source of infection exists in the community, the epidemic will continue when intervention measures are relaxed and people no longer cooperate with directives. Although many factors contributed to the second wave of the epidemic, this relaxation and low compliance may have helped to fuel it.

The scope of the COVID-19 epidemic (incidence risk range, 0.3%-1.9%) and the rate of decline in public compliance differed in the 5 states. For example, the value of the SDI declined faster in Illinois than in the other 4 states, and the level of the daily encounter-density change remained high in New Jersey. The 5 states differ in population composition (eg, race/ethnicity, age, sex, economic status) and population density, which may influence the spread of infection and effectiveness of containment efforts. Because of the ecological study design, we did not have individual-level data to analyze factors that may explain such differences. Future studies at the individual level are needed to investigate these factors.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had several strengths. First, we used objective measures to assess changes in public compliance and longitudinal estimation of associations between these changes with COVID-19 transmissibility and spread. Also, the use of human mobility indices to measure public compliance may be more valid than self-reported measures, because people may self-report higher compliance as a result of social desirability bias.

However, this study also had several limitations. First, we estimated the daily reproduction number and daily growth rate based on reported cases; as such, presymptomatic and asymptomatic cases, as well as cases with mild symptoms, might not have been captured. 28 Also, case ascertainment improved during the study period and might have introduced bias into the results. However, the bias was likely not substantial, because the daily reproduction number and daily growth rate depend on the rate of change rather than on the absolute number of cases. Second, the 2 quantitative measures of human mobility were measured in aggregate and might not represent mobility at the individual level, possibly leading to ecological fallacy. The global positioning system geolocation data did not include people without smartphones or people who did not carry their cell phones with them. Furthermore, the Unacast developers defined an encounter as 2 clusters observed in a spatial distance of ≤50 m. 6 The recommendation for social distancing to prevent the spread of infection is a minimum of 6 ft (about 1.8 m). Thus, compliance with social distancing may have been overestimated. Third, the estimate of the SDI included only out-of-county trips and did not specify interstate trips. The developers of the SDI computed benchmark values for the SDI using data from weekdays (Monday through Friday) during the first 2 weeks of February. The omission of weekend data may have introduced bias. Finally, in addition to social distancing, personal behaviors (handwashing, wearing face masks) and other public health interventions (eg, testing, contact tracing) might have confounded the association between social distancing and the scope of the epidemic.

Conclusion

Our study documents the effect of social distancing measures on reducing the spread of SARS-CoV-2. However, the degree of effect may be based on public compliance with government directives. State authorities have limited capacity to enforce social distancing measures; therefore, public compliance is needed to achieve public health benefits. To develop effective interventions, future research should identify the factors that either promote or reduce compliance with social distancing measures and quantify their contribution to viral spread.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the Department Research Discretionary Funds. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Maryland or the National Cancer Institute.

ORCID iD

Hongjie Liu, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5733-4309

References

- 1. GitHub . Coronavirus (COVID-19) data in the United States. The New York Times. 2021. Accessed June 15, 2020. https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data

- 2. Anderson RM., Heesterbeek H., Klinkenberg D., Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931-934. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Courtemanche C., Garuccio J., Le A., Pinkston J., Yelowitz A. Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(7):1237-1246. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sheikh A., Sheikh Z., Sheikh A. Novel approaches to estimate compliance with lockdown measures in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):010348. 10.7189/jogh.10.010348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maryland Transportation Institute . University of Maryland COVID-19 impact analysis platform. 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://data.covid.umd.edu

- 6. Unacast . Social distancing scoreboard. 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://www.unacast.com/covid19/social-distancing-scoreboard

- 7. Ngo M. Rounding out the social distancing scoreboard. 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://www.unacast.com/post/rounding-out-the-social-distancing-scoreboard

- 8. Pan Y., Darzi A., Kabiri A. et al. Quantifying human mobility behaviour changes during the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20742. 10.1038/s41598-020-77751-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cori A., Ferguson NM., Fraser C., Cauchemez S. A new framework and software to estimate time-varying reproduction numbers during epidemics. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(9):1505-1512. 10.1093/aje/kwt133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nishiura H., Linton NM., Akhmetzhanov AR. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:284-286. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao S., Cao P., Gao D. et al. Serial interval in determining the estimation of reproduction number of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27(3):taaa033. 10.1093/jtm/taaa033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gatto M., Bertuzzo E., Mari L. et al. Spread and dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy: effects of emergency containment measures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(19):10484-10491. 10.1073/pnas.2004978117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vynnycky E., White RG. An Introduction to Infectious Disease Modeling. Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu S., Clarke C., Shetterly S., Narwaney K. Estimating the growth rate and doubling time for short-term prediction and monitoring trend during the COVID-19 pandemic with a SAS macro. J Emerg Rare Dis. 2020;3(1):1-8. 10.31021/jer.20203121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yaffee RA., McGee M. Introduction to Time Series Analysis and Forecasting With Applications of SAS and SPSS. Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lauer SA., Grantz KH., Bi Q. et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):577-582. 10.7326/M20-0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. SAS Institute Inc . SAS/ETS Version 9.1 User’s Guide. SAS Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sen S., Karaca-Mandic P., Georgiou A. Association of stay-at-home orders with COVID-19 hospitalizations in 4 states. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2522-2524. 10.1001/jama.2020.9176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Siedner MJ., Harling G., Reynolds Z. et al. Social distancing to slow the US COVID-19 epidemic: longitudinal pretest–posttest comparison group study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(8):e1003244. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brzezinski A., Kecht V., Van Dijcke D., Wright A. Belief in science influences physical distancing in response to COVID-19 lockdown policies. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics working paper no. 2020-56. April 30, 2020. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3587990

- 21. Painter M., Qiu T. Political beliefs affect compliance with COVID-19 social distancing orders. 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3569098

- 22. Plohl N., Musil B. Modeling compliance with COVID-19 prevention guidelines: the critical role of trust in science. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26(1):1-12. 10.1080/13548506.2020.1772988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tomczyk S., Rahn M., Schmidt S. Social distancing and stigma: association between compliance with behavioral recommendations, risk perception, and stigmatizing attitudes during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychol. 2020;11:11. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhou Q., Lai X., Zhang X., Tan L. Compliance measurement and observed influencing factors of hand hygiene based on COVID-19 guidelines in China. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48(9):1074-1079. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.05.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bodas M., Peleg K. Self-isolation compliance in the COVID-19 era influenced by compensation: findings from a recent survey in Israel. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):936-941. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Powell-Jackson T., King JJC., Makungu C. et al. Infection prevention and control compliance in Tanzanian outpatient facilities: a cross-sectional study with implications for the control of COVID-19. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(6):e780-e789. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30222-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pan A., Liu L., Wang C. et al. Association of public health interventions with the epidemiology of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1915-1923. 10.1001/jama.2020.6130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reese H., Iuliano AD., Patel NN. et al. Estimated incidence of COVID-19 illness and hospitalization—United States, February–September, 2020 [published online November 25, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]