Abstract

Objectives

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer and questioning (LGBTQ+) people and populations face myriad health disparities that are likely to be evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. The objectives of our study were to describe patterns of COVID-19 testing among LGBTQ+ people and to differentiate rates of COVID-19 testing and test results by sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

Participants residing in the United States and US territories (N = 1090) aged ≥18 completed an internet-based survey from May through July 2020 that assessed COVID-19 testing and test results and sociodemographic characteristics, including sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). We analyzed data on receipt and results of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antibody testing for SARS-CoV-2 and symptoms of COVID-19 in relation to sociodemographic characteristics.

Results

Of the 1090 participants, 182 (16.7%) received a PCR test; of these, 16 (8.8%) had a positive test result. Of the 124 (11.4%) who received an antibody test, 45 (36.3%) had antibodies. Rates of PCR testing were higher among participants who were non–US-born (25.4%) versus US-born (16.3%) and employed full-time or part-time (18.5%) versus unemployed (10.8%). Antibody testing rates were higher among gay cisgender men (17.2%) versus other SOGI groups, non–US-born (25.4%) versus US-born participants, employed (12.6%) versus unemployed participants, and participants residing in the Northeast (20.0%) versus other regions. Among SOGI groups with sufficient cell sizes (n > 10), positive PCR results were highest among cisgender gay men (16.1%).

Conclusions

The differential patterns of testing and positivity, particularly among gay men in our sample, confirm the need to create COVID-19 public health messaging and programming that attend to the LGBTQ+ population.

Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus, LGBTQ+, sexual and gender minority

By the second quarter of 2021, more than 30 million people in the United States had been infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and approximately 550 000 deaths were attributed to the disease. 1 COVID-19 morbidity and mortality vary across demographic strata, 2 and the risk of contracting COVID-19 is disproportionately high among racial/ethnic minority populations, 3,4 people living in rural areas, people who are underinsured or uninsured, 5 and people with low income. 4

In 2020, efforts to contain the disease focused primarily on behaviors, including testing for the presence of the virus, contact tracing, and isolation. 6 Of the approximately 100 million polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests by the endpoint of our study on July 31, 2020, 8% had a positive test result. 1,7,8 As of year-end 2020, the positivity rate in the United States was 7.2%. 1 Antibody testing has been less widespread than PCR testing in the United States. 9,10

A disproportionate rate of morbidity and mortality caused by COVID-19 is associated with several sociodemographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity and sex assigned at birth. 1,11 No national epidemiologic data are available on sexual or gender minority (SGM, also known as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer and questioning [LGBTQ+]) populations, despite a history of health disparities 12 -14 when compared with non-LGBTQ+ populations in such areas as HIV, 15,16 mental health problems, 17 -19 barriers to effective and competent health care, 20,21 substance use, 22,23 homelessness, 24,25 and violence. 26 These co-occurring health conditions often function synergistically 27,28 and result from social determinants of health rather than innate health deficits of SGM populations. 29 -32 Some local jurisdictions capture these epidemiologic data, but other than data from the Williams Institute, 33 none are available at the national level. In addition to social and structural factors that undermine the health of LGBTQ+ people, 13,31,34 -37 this population confronts challenges in identifying competent health care and is often subjected to discrimination from health care providers. 12,38 -40 Furthermore, many LGBTQ+ people are frontline or essential workers, have socioeconomic disadvantages, have lost jobs because of the pandemic-related economic downturn, 40 -44 and/or have been dismissed from their jobs because of their sexual and gender identities. 45,46 Taken together, these conditions could predispose SGM populations to a higher vulnerability to COVID-19 compared with the general US population.

Data on the health of LGBTQ+ people are limited because most large-scale surveys, including the US Census 47 and the American Community Survey, 48 do not collect data on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also fails to report data on SOGI as these data relate to COVID-19, and most health systems and local health departments do not include SOGI items on medical documents, despite the need to include such information for effective health care delivery. 12,49,50 In effect, no population-level data on COVID-19 among SGM people exist in the United States. Our study intends to fill this gap in knowledge by describing data on the receipt of COVID-19 tests, the results of these tests, and the presence of COVID-19 symptoms in the LGBTQ+ population according to key sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional internet-based survey from May 7 through July 31, 2020, to examine the manifestation of COVID-19 among LGBTQ+ people in the United States. Participants were eligible if they were aged ≥18, lived in the United States or in a US territory, and identified as LGBTQ+. We asked participants to self-report sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Using best practices of a 2-step approach to collect data on gender, 51 we excluded participants who were cisgender and heterosexual. Study protocol and activities were approved by the institutional review board at Rutgers University.

Data Collection and Cleaning Procedures

We built and hosted the survey on Qualtrics XM (Qualtrics), and it was available to participants in 2 waves, Wave I (May 7-8, 2020) and Wave II (June 11–July 31, 2020). We recruited participants from the listservs of 18 professional organizations (eg, American Psychological Association, Garden State Equality), via social media groups dedicated to LGBTQ+ topics, and via social media accounts (eg, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit) of the Center for Health, Identity, Behavior, and Prevention Studies and research staff members by an anonymous link to the survey. After screening, eligible participants were directed to the survey and provided informed consent. After completion, participants received a $5 electronic gift card in Wave I and an opportunity to enter a raffle to win 1 of 10 $100 electronic gift cards in Wave II.

We initially planned to conduct the survey in a single wave, but we changed to 2 waves after we detected bots attempting to claim incentive gift cards in Wave I. Upon discovery, we removed records with inconsistencies, such as a reCaptcha (Google) score <0.5 or the submission of duplicate answers for qualitative questions. We added other bot protections for Wave II, including repetition of sociodemographic questions and IP (internet protocol) address checks. We did not detect bot activity in Wave II. The final sample across the 2 waves consisted of 1090 participants, 477 in Wave I and 613 in Wave II. We found no differences in sociodemographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity, between the 2 waves.

Measures

Participants self-reported sociodemographic data. We recorded age as a continuous variable and categorized this variable into groups (18-29, 30-39, 40-49, ≥50). Participants reported their sex assigned at birth (male/female) and their gender identity (cisgender man, cisgender woman, transgender man, transgender woman, nonbinary/genderqueer/gender nonconforming, or a free-text option) and sexual orientation (heterosexual/straight, gay or lesbian, bisexual, or a free-text option). For race and ethnicity, participants were asked to choose all that apply: Hispanic/Latinx, American Indian/Alaska Native, Black/African American, Asian, Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, or “other”; responses were used to constitute the analytic groups: Hispanic/Latinx, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, multiracial, non-Hispanic White, and other.

For a nuanced understanding of the intersectionality of SOGI, we categorized participants into 15 groups for each combination of SOGI. For the analyses of SOGI, because of small cell sizes, we combined transgender people into 3 subgroups for each sexual orientation category. We also gathered data on educational attainment (≤high school diploma/general education development [GED], some college or an associate’s degree, ≥bachelor’s degree), employment (unemployed, employed full-time, employed part-time), relationship status (single; in a committed relationship; married or in a domestic partnership; separated, widowed, or divorced), and nation of birth (United States, outside United States). Participants self-reported their HIV status (positive, negative, unknown).

We recorded geographic data through the use of US Postal Service zip codes and matched zip codes to states and territories. We grouped these data into 6 categories: Northeast, Midwest, Mountain, Pacific, South, and noncontiguous US regions. 52,53

The survey asked participants to report history of PCR and antibody testing, including dates and results. To ensure accuracy of response, we provided a definition for these assays: “A PCR measures current infection with the virus (often a nasal swab) and an antibody test measures having been exposed to the virus (often a blood test).” We also asked participants if they had any of the following COVID-19 symptoms: body temperature ≥100.4 °F, dry cough, shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, loss of smell or taste, stomach issues, headache, congestion, sore throat, muscle aches, fatigue, conjunctivitis, or none. We framed all survey questions on March 13, 2020, the onset of the pandemic.

Statistical Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics for all sociodemographic characteristics and COVID-19 health variables. We analyzed the relationship between COVID-19 testing and positivity and sociodemographic characteristics. After conducting bivariable analyses using nonparametric χ2 tests of independence with critical value set at P = .05, 54 we used logistic regression models to analyze data on receipt of COVID-19 testing and test results.

We matched zip codes to zip code tabulation areas from the US Census Bureau 55 to create maps of the frequencies of participants by each US region, state, and territory. We conducted all study analyses with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) and QGIS version 3.14.15 (Open Source Geospatial Foundation).

Results

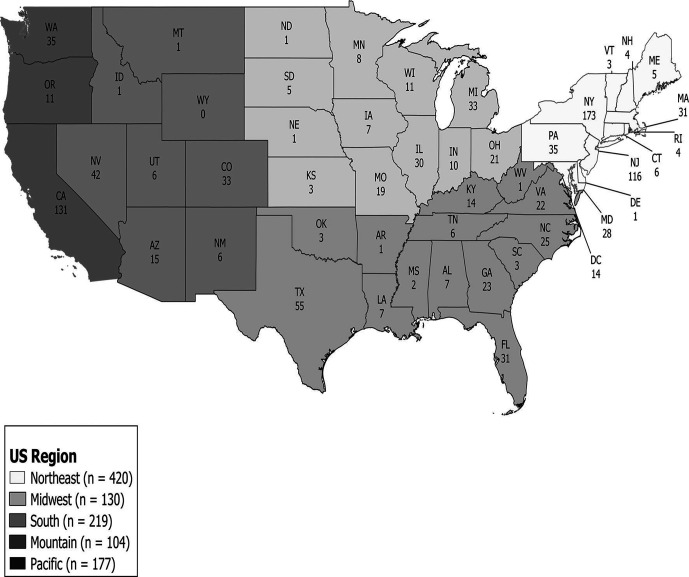

On average, survey participants were aged 33.9 (SD, 11.8; range, 18-81), and the sample (N = 1090) was racially/ethnically diverse (Table 1). Most participants were gay cisgender men (36.4%; n = 397), lesbian cisgender women (17.4%; n = 190), or bisexual cisgender women (15.4%; n = 168). Approximately 8% of participants were transgender across all groups. Most (93.3%; n = 1017) participants reported having at least some college education, and most (80.3%; n = 875) were employed part-time or full-time; 19.7% were unemployed. About two-thirds (67.0%; n = 730) of participants were married, in a domestic partnership, or in a committed relationship. Ninety-nine (9.1%) participants were HIV-positive. By US region, the greatest percentage of participants (38.5%; n = 420) resided in the Northeast (Table 1, Figure).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants in a nationwide survey of COVID-19 testing among LGBTQ+ people (N = 1090), United States, 2020a

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| 18-29 | 497 (45.6) |

| 30-39 | 347 (31.8) |

| 40-49 | 110 (10.1) |

| ≥50 | 136 (12.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 104 (9.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 121 (11.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander | 47 (4.3) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native/other b | 23 (2.1) |

| Multiracial | 43 (3.9) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 752 (69.0) |

| Sexual orientation and gender identity | |

| Gay cisgender men | 397 (36.4) |

| Bisexual cisgender men | 73 (6.7) |

| Other sexual orientation cisgender men | 9 (0.8) |

| Lesbian cisgender women | 190 (17.4) |

| Bisexual cisgender women | 168 (15.4) |

| Other sexual orientation cisgender women | 42 (3.9) |

| Gay transgender men | 16 (1.5) |

| Bisexual transgender men | 16 (1.5) |

| Other sexual orientation transgender men | 17 (1.6) |

| Lesbian transgender women | 12 (1.1) |

| Bisexual transgender women | 15 (1.4) |

| Other sexual orientation transgender women | 10 (0.9) |

| Gay/lesbian nonbinary | 32 (2.9) |

| Bisexual nonbinary | 50 (4.6) |

| Other sexual orientation nonbinary | 43 (3.9) |

| Educational attainment | |

| ≤High school diploma/GED | 73 (6.7) |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 243 (22.3) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 774 (71.0) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 215 (19.7) |

| Employed full-time | 643 (59.0) |

| Employed part-time | 232 (21.3) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 325 (29.8) |

| In a committed relationship | 434 (39.8) |

| Married or domestic partnership | 296 (27.2) |

| Separated, widowed, or divorced | 35 (3.2) |

| HIV status | |

| Positive | 99 (9.1) |

| Negative | 866 (79.4) |

| Unknown | 122 (11.2) |

| Missing | 3 (0.3) |

| Nation of birth | |

| Outside United States | 74 (6.8) |

| United States | 1012 (92.8) |

| Missing | 4 (0.4) |

| US region | |

| Northeast | 420 (38.5) |

| Midwest | 130 (11.9) |

| South | 219 (20.1) |

| Mountain | 104 (9.5) |

| Pacific | 177 (16.2) |

| Noncontiguous states and territories | 30 (2.8) |

| Missing | 10 (1.0) |

Abbreviations: GED, general education diploma; LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer and questioning.

aData source: a cross-sectional internet-based survey conducted by the authors from May 7 through July 31, 2020.

b“Other” racial/ethnic group includes participants who wrote in a response under “other” that was not a previously listed group.

Figure.

Number of participants, by region and state, in a nationwide survey of COVID-19 testing among LGBTQ+ people (N = 1090), United States, 2020. Thirty participants resided in noncontiguous states and territories: Hawaii (n = 5), Alaska (n = 1), Northern Mariana Islands (n = 5), Guam (n = 0), American Samoa (n = 2), Puerto Rico (n = 11), and US Virgin Islands (n = 6). Data source: a cross-sectional internet-based survey conducted by the authors from May 7 through July 31, 2020. Abbreviation: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer and questioning.

COVID-19 Testing and Symptoms

A small proportion of the sample received a PCR test (16.7% [95% CI, 14.5%-18.9%]; n = 182), and a small proportion received an antibody test (11.4% [95% CI, 9.5%-13.3%]; n = 124) (Table 2); 5.0% (n = 55) received both tests. Of participants who received a PCR test, 8.8% (95% CI, 4.7%-12.9%; n = 16) reported a positive PCR test result and 36.2% (95% CI, 27.8%-44.8%; n = 45) reported a positive antibody test result. All 16 PCR-positive participants reported a positive antibody test result. Of the 1090 participants, 65.3% (95% CI, 62.5%-68.1%; n = 712) reported ≥1 COVID-19 symptom and 21.7% (95% CI, 19.3%-24.2%; n = 237) reported >3 COVID-19 symptoms commencing on or about March 13, 2020.

Table 2.

Receipt of COVID-19 tests and test results of participants in a nationwide survey of COVID-19 testing among LGBTQ+ people (N = 1090), United States, 2020 a

| Variable | No. of participants | No. (%) b |

|---|---|---|

| Received a PCR test | 1090 | |

| Yes | 182 (16.7) | |

| No | 891 (81.7) | |

| Unsure | 13 (1.2) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.4) | |

| PCR test result | 182 | |

| Positive | 16 (8.8) | |

| Negative | 158 (86.8) | |

| Missing | 8 (4.4) | |

| Received an antibody test | 1090 | |

| Yes | 124 (11.4) | |

| No | 948 (87.0) | |

| Unsure | 14 (1.3) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.4) | |

| Antibody test result | 124 | |

| Had antibodies | 45 (36.3) | |

| Did not have antibodies | 74 (59.7) | |

| Missing | 5 (4.0) | |

| Reported ≥1 COVID-19 symptom | 1090 | |

| Yes | 712 (65.3) | |

| No | 374 (34.3) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.4) | |

| Reported >3 COVID-19 symptoms | 1090 | |

| Yes | 237 (21.7) | |

| No | 849 (77.9) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.4) | |

| Do you think you’ve had COVID-19? | 839 | |

| Yes | 113 (13.5) | |

| No | 721 (85.9) | |

| Missing | 5 (0.6) |

Abbreviations: LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer and questioning; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

aData source: a cross-sectional internet-based survey conducted by the authors from May 7 through July 31, 2020.

bPercentages may not total to 100 because of rounding.

COVID-19 Testing and Results by Sociodemographic Characteristics

Whether a survey participant received PCR testing was related to employment status (χ2 = 8.4; df = 2; P = .02); 19.3% (n = 122) of participants employed full-time received a PCR test, whereas only 10.8% (n = 23) of unemployed participants received a PCR test (Table 3). We found no significant differences in PCR test results in the sample of 174 participants by any sociodemographic characteristic, in part because of insufficient cell sizes, particularly for the SOGI groups. However, among SOGI groups with sufficient sample size (n > 10), gay cisgender men had higher rates of PCR positivity (16.1%; 10 of 62) than bisexual cisgender men (0 of 17), lesbian cisgender women (8.2%; 2 of 24), and bisexual cisgender women (0 of 31).

Table 3.

Receipt of COVID-19 tests and test results among participants in a nationwide survey of COVID-19 testing among LGBTQ+ people, by sociodemographic characteristics, United States, 2020 a

| Characteristic | Received a PCR test

b

(n = 1073) |

Received an antibody test b (n = 1072) | PCR test result (n = 174) |

Antibody test result (n = 119) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 182) |

No (n = 891) |

P value c | Yes (n = 124) |

No (n = 948) |

P value c | Positive (n = 16) | Negative (n = 158) | P value c | Positive (n = 45) | Negative (n = 74) | P value c | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 35.4 (12.3) | 33.6 (11.8) | .07 | 37.9 (12.5) | 33.4 (11.7) | <.001 | 39.2 (17.8) | 34.7 (11.5) | .15 | 35.6 (12.0) | 39.2 (12.9) | .14 |

| Age group, y | .24 | <.001 | .08 d | .16 | ||||||||

| 18-29 | 71 (14.5) | 419 (85.5) | 40 (8.2) | 449 (91.8) | 7 (10.0) | 63 (90.0) | 20 (51.3) | 19 (48.7) | ||||

| 30-39 | 62 (18.3) | 277 (81.7) | 38 (11.2) | 301 (88.8) | 2 (3.4) | 57 (96.6) | 13 (36.1) | 23 (63.9) | ||||

| 40-49 | 22 (20.2) | 87 (79.8) | 19 (17.4) | 90 (82.6) | 2 (10.0) | 18 (90.0) | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | ||||

| ≥50 | 27 (20.0) | 108 (80.0) | 27 (20.0) | 108 (80.0) | 5 (20.0) | 20 (80.0) | 7 (28.0) | 18 (72.0) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity e | .71 | .86 | .16 d | .63 d | ||||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 21 (20.4) | 82 (79.6) | 10 (9.8) | 92 (90.2) | 4 (19.0) | 17 (81.0) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 23 (19.2) | 97 (80.8) | 13 (10.9) | 106 (89.1) | 0 | 23 (100.0) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | ||||

| Multiracial | 7 (15.9) | 34 (84.1) | 6 (14.0) | 37 (86.0) | 0 | 7 (100.0) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 118 (17.1) | 624 (82.9) | 89 (12.0) | 650 (88.0) | 12 (10.9) | 98 (89.1) | 35 (41.7) | 49 (58.3) | ||||

| Other f | 13 (19.4) | 54 (80.6) | 6 (8.7) | 63 (91.3) | 0 | 13 (100.0) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | ||||

| Sexual orientation and gender identity | .21 | <.001 | — g | — g | ||||||||

| Gay cisgender men | 67 (17.2) | 322 (82.8) | 69 (17.7) | 332 (82.4) | 10 (16.1) | 52 (83.9) | 27 (41.5) | 38 (58.5) | ||||

| Bisexual cisgender men | 17 (23.9) | 54 (76.1) | 4 (5.6) | 67 (94.4) | 0 | 17 (100.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||||

| Other sexual orientation cisgender men | 0 | 9 (100.0) | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | ||||

| Lesbian cisgender women | 25 (13.5) | 160 (86.5) | 17 (9.3) | 166 (90.7) | 2 (8.3) | 22 (91.7) | 6 (35.3) | 11 (64.7) | ||||

| Bisexual cisgender women | 33 (19.6) | 135 (80.4) | 11 (6.7) | 154 (93.3) | 0 | 31 (100.0) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | ||||

| Other sexual orientation cisgender women | 3 (7.1) | 39 (92.9) | 1 (2.4) | 41 (97.6) | 0 | 3 (100.0) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | ||||

| Gay/lesbian transgender people | 2 (7.1) | 26 (92.9) | 1 (3.6) | 27 (96.4) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | ||||

| Bisexual transgender people | 7 (22.6) | 24 (77.4) | 4 (12.9) | 27 (87.1) | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.2) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||||

| Other sexual orientation transgender people | 6 (22.2) | 21 (77.8) | 2 (7.4) | 25 (92.6) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||||

| Gay/lesbian nonbinary people | 8 (25.0) | 24 (75.0) | 9 (28.1) | 23 (71.9) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | ||||

| Bisexual nonbinary people | 7 (14.3) | 42 (85.7) | 3 (6.0) | 47 (94.0) | 0 | 7 (100.0) | 0 | 3 (100.0) | ||||

| Other sexual orientation nonbinary people | 7 (16.7) | 35 (83.3) | 2 (4.7) | 41 (95.4) | 0 | 7 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (100.0) | ||||

| Educational attainment | .13 | .002 | .73 d | .42 d | ||||||||

| ≤High school diploma/GED | 13 (18.8) | 56 (81.2) | 10 (14.1) | 61 (85.9) | 1 (7.7) | 12 (92.3) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | ||||

| Some college or associate’s degree | 30 (12.7) | 207 (87.3) | 12 (5.1) | 222 (94.9) | 4 (13.3) | 26 (86.7) | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) | ||||

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 139 (18.1) | 628 (81.9) | 102 (13.3) | 665 (86.7) | 11 (8.4) | 120 (91.6) | 35 (35.4) | 64 (64.6) | ||||

| Employment | .02 | .002 | .86 d | .90 | ||||||||

| Unemployed | 23 (10.8) | 190 (89.2) | 16 (7.5) | 198 (92.5) | 1 (4.3) | 22 (95.7) | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | ||||

| Employed full-time | 122 (19.3) | 509 (80.7) | 91 (14.4) | 539 (85.6) | 12 (10.5) | 102 (89.5) | 33 (37.9) | 54 (62.1) | ||||

| Employed part-time | 37 (16.2) | 192 (83.8) | 17 (7.5) | 211 (92.5) | 3 (8.1) | 34 (91.9) | 7 (41.2) | 10 (58.8) | ||||

| Relationship status | .64 | <.001 | .09 d | .48 d | ||||||||

| Single | 59 (18.3) | 263 (81.7) | 38 (11.8) | 283 (88.2) | 4 (7.1) | 52 (92.9) | 11 (29.7) | 26 (70.3) | ||||

| In a committed relationship | 67 (15.8) | 356 (84.2) | 30 (7.1) | 394 (92.9) | 3 (4.6) | 62 (95.4) | 11 (37.9) | 18 (62.1) | ||||

| Married or domestic partnership | 52 (17.7) | 241 (82.3) | 49 (16.7) | 244 (83.3) | 8 (16.3) | 41 (83.7) | 19 (41.3) | 27 (58.7) | ||||

| Separated, widowed, or divorced | 4 (11.4) | 31 (88.6) | 7 (20.6) | 27 (79.4) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | ||||

| HIV status | .10 | .04 | .68 d | .13 d | ||||||||

| Positive | 21 (21.4) | 77 (78.6) | 16 (16.2) | 83 (83.8) | 1 (4.8) | 20 (95.2) | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | ||||

| Negative | 149 (17.3) | 711 (82.7) | 102 (11.9) | 754 (88.1) | 15 (10.6) | 126 (89.4) | 38 (38.8) | 60 (61.2) | ||||

| Unknown | 12 (10.6) | 101 (89.4) | 6 (5.2) | 109 (94.8) | 0 | 12 (100.0) | 0 | 6 (100.0) | ||||

| Nation of birth h | .05 | <.001 | .99 d | .25 | ||||||||

| Outside United States | 18 (25.4) | 53 (74.6) | 18 (25.4) | 53 (74.6) | 1 (5.6) | 17 (94.4) | 9 (50.0) | 9 (50.0) | ||||

| United States | 163 (16.3) | 835 (83.7) | 106 (10.6) | 892 (89.4) | 15 (9.7) | 140 (90.3) | 36 (64.4) | 65 (35.6) | ||||

| US region h | .26 | <.001 | .16 d | .31 d | ||||||||

| Northeast | 84 (20.1) | 333 (79.9) | 83 (20.0) | 332 (80.0) | 11 (13.9) | 68 (86.1) | 29 (36.7) | 50 (63.3) | ||||

| Midwest | 24 (18.6) | 105 (81.4) | 13 (10.2) | 114 (89.8) | 0 | 23 (100.0) | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | ||||

| South | 29 (13.5) | 186 (86.5) | 11 (5.1) | 205 (94.9) | 1 (3.6) | 27 (96.4) | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | ||||

| Mountain | 16 (15.5) | 87 (84.5) | 7 (6.9) | 94 (93.1) | 3 (18.8) | 13 (81.3) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | ||||

| Pacific | 24 (14.0) | 147 (86.0) | 8 (4.6) | 166 (95.4) | 1 (4.3) | 22 (95.7) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | ||||

| Noncontiguous | 4 (13.8) | 25 (86.2) | 2 (6.9) | 27 (93.1) | 0 | 4 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 | ||||

Abbreviations: GED, general education diploma; LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer and questioning; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

aData source: a cross-sectional internet-based survey conducted by the authors from May 7 through July 31, 2020.

bExcluded participants who selected “I don’t know” and who were missing data. Thus, values in category may not add to value in column head.

cχ2 tests conducted to determine P values, unless otherwise indicated; P < .05 considered significant.

dFisher exact test or Freeman–Halton test used because expected cell size <5; P < .05 considered significant.

eNon-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and “other” racial/ethnic groups were collapsed into the “other” group because of insufficient cell size.

f“Other” racial/ethnic group includes participants who self-identified as non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, or wrote in a response under “other” that was not a previously listed group.

gAnalyses not conducted because of insufficient cell size.

hThe total number of participants who received a negative PCR test result by nation of birth and US region is 157 as a result of missing data.

By SOGI groups, we found the highest rates of receiving an antibody test among participants who identified as gay or lesbian nonbinary (28.1%; n = 9), bisexual transgender (12.9%; n = 4), and gay cisgender men (17.7%; n = 69). Participants who received an antibody test were older than participants who did not receive an antibody test; by age group, participants aged ≥50 were the largest proportion (20.0%) who received an antibody test. We also noted high proportions for antibody testing among participants who were born outside the United States (25.4%; n = 18), HIV-positive (16.2%; n = 16), and residing in the Northeast (20.0%; n = 83). Among the 119 participants who reported an antibody test result, we found no significant differences in positivity by any sociodemographic characteristic, in part because of insufficient cell sizes. However, in SOGI groups with sufficient cell size (n > 10), gay cisgender men had a higher positivity rate (41.5%; 27 of 65) than lesbian cisgender women (35.3%; 6 of 17).

The adjusted model for PCR testing was significant (χ2 = 12.5; df = 3; P = .006; classification fit = 83.1%). Participants who were unemployed had 0.50 lower odds than participants who were employed full-time of receiving a PCR test (Table 4). Participants born outside the United States had 1.78 times the odds of receiving a PCR test compared with participants born in the United States.

Table 4.

Binary logistic regression models examining COVID-19 testing and positivity among participants in a nationwide survey of COVID-19 testing among LGBTQ+ people, United States, 2020 a

| Characteristic | PCR test b (n = 1073) | Antibody test b , c (n = 1072) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) [P value] d | Adjusted OR (95% CI) [P value] d | OR (95% CI) [P value] d | Adjusted OR (95% CI) [P value] d | |

| Employment | ||||

| Unemployed | 0.51 (0.31-0.81) [.005] | 0.50 (0.31-0.81) [.005] | 0.48 (0.28-0.83) [.009] | 0.65 (0.35-1.20) [.17] |

| Employed part-time | 0.80 (0.54-1.20) [.29] | 0.80 (0.53-1.19) [.27] | 0.48 (0.28-0.83) [.007] | 0.70 (0.37-1.32) [.28] |

| Employed full-time | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Nation of birth | ||||

| Outside United States | 1.74 (0.99-3.05) [.05] | 1.78 (1.01-3.13) [.046] | 2.86 (1.61-5.06) [<.001] | 2.56 (1.33-4.94) [.005] |

| United States | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Sexual orientation and gender identity | ||||

| Bisexual cisgender men | — | — | 0.28 (0.10-0.79) [.02] | 0.50 (0.17-1.50) [.22] |

| Other sexual orientation cisgender men | — | — | 0.58 (0.07-4.74) [.61] | 0.50 (0.05-4.64) [.54] |

| Lesbian cisgender women | — | — | 0.48 (0.27-0.84) [.01] | 0.56 (0.31-1.04) [.07] |

| Bisexual cisgender women | — | — | 0.33 (0.17-0.65) [.001] | 0.35 (0.17-0.73) [.005] |

| Other sexual orientation cisgender women | — | — | 0.11 (0.02-0.84) [.03] | 0.12 (0.02-0.93) [.04] |

| Gay/lesbian transgender people | — | — | 0.17 (0.02-1.29) [.09] | 0.23 (0.03-1.79) [.16] |

| Bisexual transgender people | — | — | 0.69 (0.23-2.04) [.50] | 1.11 (0.35-3.58) [.86] |

| Other sexual orientation transgender people | — | — | 0.37 (0.09-1.61) [.19] | 0.58 (0.12-2.68) [.48] |

| Gay/lesbian nonbinary people | — | — | 1.83 (0.81-4.12) [.15] | 1.98 (0.79-4.97) [.15] |

| Other sexual orientation nonbinary people | — | — | 0.30 (0.09-0.99) [.047] | 0.31 (0.09-1.08) [.07] |

| Bisexual nonbinary people | — | — | 0.23 (0.05-0.96) [.04] | 0.23 (0.05-1.01) [.05] |

| Gay cisgender men | — | — | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 30-39 | — | — | 1.42 (0.89-2.26) [.14] | 0.92 (0.54-1.56) [.76] |

| 40-49 | — | — | 2.37 (1.31-4.28) [.004] | 1.04 (0.52-2.09) [.91] |

| ≥50 | — | — | 2.81 (1.65-4.78) [<.001] | 1.26 (0.66-2.41) [.48] |

| 18-29 | — | — | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Some college or associate’s degree | — | — | 0.33 (0.14-0.80) [.01] | 0.23 (0.09-0.61) [.003] |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | — | — | 0.94 (0.46-1.89) [.85] | 0.54 (0.24-1.23) [.14] |

| ≤High school diploma/GED | — | — | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Relationship status | ||||

| In a committed relationship | — | — | 0.57 (0.34-0.94) [.03] | 0.57 (0.33-0.99) [.046] |

| Married or domestic partnership | — | — | 1.5 (0.95-2.36) [.08] | 1.37 (0.81-2.33) [.24] |

| Separated, widowed, or divorced | — | — | 1.93 (0.79-4.74) [.15] | 2.45 (0.88-6.83) [.09] |

| Single | — | — | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| HIV status | ||||

| Positive | — | — | 1.43 (0.80-2.53) [.23] | 1.14 (0.58-2.25) [.70] |

| Unknown | — | — | 0.41 (0.17-0.95) [.04] | 0.59 (0.24-1.48) [.26] |

| Negative | — | — | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| US region | ||||

| Midwest | — | — | 0.46 (0.25-0.85) [.01] | 0.61 (0.31-1.21) [.16] |

| South | — | — | 0.22 (0.11-0.41) [<.001] | 0.21 (0.11-0.43) [<.001] |

| Mountain | — | — | 0.30 (0.13-0.67) [.003] | 0.26 (0.11-0.61) [.002] |

| Pacific | — | — | 0.19 (0.09-0.41) [<.001] | 0.20 (0.09-0.43) [<.001] |

| Noncontiguous | — | — | 0.30 (0.07-1.27) [.10] | 0.30 (0.06-1.45) [.13] |

| Northeast | — | — | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviations: GED, general education diploma; LGBTQ+, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer and questioning; OR, odds ratio; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

aData source: a cross-sectional internet-based survey conducted by the authors from May 7 through July 31, 2020.

bExcluded participants who selected “I don’t know” or who were missing data. Thus, values in category may not add to value in column head.

cThe antibody test multivariate model had 1057 responses because of missing data for HIV status (n = 2), nation of birth (n = 3), and US region (n = 10).

dLogistic regression conducted to determine P values; P < .05 considered significant.

For antibody testing, the adjusted model was significant (χ2 = 129.0; df = 29; P < .001; classification fit = 79.5%). Bisexual cisgender women had 0.35 lower odds than gay cisgender men of receiving an antibody test. Participants born outside the United States had 2.56 times the odds of receiving an antibody test compared with participants born in the United States. Participants with some college or an associate’s degree had 0.23 lower odds than participants with ≤high school diploma or GED of receiving an antibody test; moreover, compared with single participants, participants in a committed relationship had 0.57 lower odds of receiving an antibody test. By US region, compared with participants who lived in the Northeast, participants who lived in the South had 0.21 lower odds, participants who lived in the Mountain region had 0.26 lower odds, and participants who lived in the Pacific region had 0.20 lower odds of receiving an antibody test.

Discussion

Our survey of LGBTQ+ people living in the United States and its territories suggests that this population is especially vulnerable to COVID-19, as previously suggested. 56 Approximately 9% of our sample reported having a positive PCR test result. This positivity rate is slightly higher than the estimated 8% of the 54 million people in the United States who had a positive test result as of the end of July 2020, 8 when our survey concluded, and the 7.2% at the end of 2020. The difference between our study sample and the general population is small, but it is worth noting because even a small difference can affect community spread. The effect on community spread may apply particularly to LGBTQ+ people, who tend to socialize primarily with other SGM people as part of identity formation and homophily. 57 -62 In addition, approximately 35% of our sample reported a positive antibody test result. In comparison, 1.5% of people tested in a study conducted in April 2020 in Santa Clara, California, were seropositive, 63 and approximately 14% of health care workers in a New York City–based facility tested during approximately the same time had antibodies. 64

Among survey participants who received both types of tests, all who reported a positive PCR test result also reported a positive antibody test result. Although antibodies appear to decline over time, their presence suggests the spread of the disease. 65 We found that slightly more than 1 in 3 LGBTQ+ people in our survey who received an antibody test reported a positive antibody test result. By the end of April 2020, 7.6% of the US population had been infected. 66 Also, in New York City, a COVID-19 epicenter where widescale antibody testing took place, the rate of a positive test result was as high as 61.3% during the week of April 11, 2020, and as low as 19.4% during the week of August 15, 2020. 67 Given these positivity rates, our finding of 1 in 3 suggests a higher rate of infection among LGBTQ+ people.

Our data also indicate the differential effects of COVID-19 within LGBTQ+ populations. PCR positivity was higher in gay cisgender men than in any other sexual and/or gender identity group with a sufficient sample size. Cisgender gay men may have been infected at higher rates than other LGBTQ+ people as a result of social conditions, such as being members of the frontline workforce (eg, food servers, health care providers), 42,43 rather than as a result of behaviors such as substance use and sexual behavior; evidence on behavior change during the COVID-19 pandemic is limited and mixed. 68 -71 Given the limit in the availability of COVID-19 testing at the onset of the pandemic, 72 -74 it is likely that people who had a positive test result also had severe symptoms, making them eligible for testing. Patterns of PCR testing also provide some insight into the social dynamics of the disease. People born outside the United States have higher rates of testing, suggesting the vulnerability of immigrant groups to COVID-19, as is the case with other health conditions. 75,76 Similarly, we found that rates of testing were higher among employed survey participants than among unemployed survey participants, perhaps because some employers require COVID-19 testing to return to work 77,78 or survey participants, as members of the essential workforce, were more exposed to SARS-CoV-2 than unemployed participants. 79,80 Employment may act as a proxy for access to health insurance, which would also affect testing behaviors. Although all COVID-19 testing costs should be covered by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which was enacted by the federal government to provide financial support to businesses and individuals, 81 people without health insurance may have been hesitant to seek care because of reports of unexpected billing. 82,83

In part as a result of insufficient cell sizes, we found no differences in antibody positivity by any sociodemographic characteristic, although in SOGI groups with sufficient data, antibody positivity was higher among gay cisgender men than among lesbian cisgender women. However, we found differential patterns of antibody testing, and these patterns may provide a proxy measure for perceived susceptibility to COVID-19. By age group, survey participants aged ≥50 had the highest rate of receiving an antibody test, which is not surprising because the disease appears to lead to worse health outcomes among older people than among young adults, adolescents, or children. 84 In addition, gay and lesbian people reported higher rates of antibody testing than other LGBTQ+ groups. Lesbian women may have had higher levels of testing because of greater perceived susceptibility; a previous study found that sexual minority women were more likely than heterosexual women to report both direct and indirect COVID-19 exposure. 85 These patterns among lesbian women suggest an analogous perceived susceptibility among gay men that may lead to higher levels of test-seeking behaviors than among the general population, 86 similar to findings in the relationship between perceived HIV susceptibility and HIV testing behaviors. 87 -89 To that end, lessons learned from the HIV epidemic may influence gay men’s approach to COVID-19 prevention, including the adoption of harm reduction strategies such as social distancing and wearing face masks, behaviors echoing condom use for sexual behavior. 90 -92 Although some studies have found that sexual minority men have high levels of engagement in COVID-19 preventive behaviors, such as social distancing and fewer sex partners than before the pandemic, 68 -70 studies have also found an increased number of sexual partners, 71 reflecting the ways in which COVID-19 may be perceived as less severe than HIV. 71 The theorized relationship between testing and perceived susceptibility is complemented by the fact that a higher proportion of HIV-positive people in our study reported a higher rate of testing than did HIV-negative people, consistent with findings from other studies that sexual minority men with HIV have a high perceived susceptibility to COVID-19. 93,94 A higher proportion of COVID-19 testing may also be because most HIV-positive people in the United States are gay men, are engaged in care, and perceive greater vulnerability to COVID-19 than people who are HIV-negative. 95 Finally, the highest rates of antibody testing were reported by LGBTQ+ people living in the Northeast, one of the epicenters of the early COVID-19 epidemic in the United States. 96,97

The vulnerability of LGBTQ+ people to COVID-19 and the persistence of other health disparities experienced by the population are predicated on social inequities. 98 Social and structural factors that perpetuate minority stressors and psychosocial burdens 32,99 undermine the health of LGBTQ+ people. These are the very same factors that create vulnerability to COVID-19 and are much like the factors that create vulnerability to HIV. 95,100 Moreover, these factors are heightened by a health care system that does not address the nuanced needs of the population 12,101 -104 or the inherent biases of health care providers. 105,106 Although we did not find significant differences in COVID-19 PCR and antibody testing results by race/ethnicity or gender identity, future research is warranted to better understand the effects of COVID-19 on Black and/or transgender LGBTQ+ people, who face disparities in health conditions, health care access, and economic stability. 56,107 -109 Our null finding may be due to our convenience sampling method or because the effects of race, ethnicity, or social class are not always evident at the onset of a pandemic, as was true for the 1918 influenza pandemic 110 or the HIV epidemic in the United States. 111 However, the negative effect of COVID-19 on the Black population is evidenced in the general population, 112 and as the disease has progressed, disparities have become more evident, especially among Black men. 113,114 For LGBTQ+ people who also identify as Black, the effects of disease are compounded by intersecting minority identities. 115

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, the study used a convenience sample and was subject to self-selection bias. Rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection may be higher in our sample than in the general population if people who had the disease were also more likely than uninfected or unaffected people to complete the survey. In addition, the use of convenience sampling may have led to an overrepresentation of some sociodemographic groups, which may inhibit the generalizability of our findings. Second, the testing data were self-reported, and participants may have received PCR and antibody tests with different specificities and sensitivities. To avoid any confusion about PCR and antibody testing, our survey clearly explained these different types of tests, and we feel confident in the accuracy of responses with regard to test type. Third, despite our efforts, the survey was completed by a large proportion of White participants. We considered weighting responses, but because of the lack of population LGBTQ+ data, we could not ascertain accurate weights. We recognize that the pandemic continues to evolve and that our data reflect only one short period and are likely to change over time.

Conclusions

LGBTQ+ people appear to be at heightened risk for COVID-19 compared with the general US population, as they are for other health conditions. Public health efforts must address the vulnerability of the population to this health disparity. However, it is also critical that health care providers and public health practitioners recognize that this population is not monolithic. The differential PCR and antibody positivity rates, with heightened rates among gay men noted in our study, coupled with other recent findings suggesting the vulnerability faced by LGBTQ+ people of color, 33 suggest that messaging on COVID-19 risk and the delivery of care to the LGBTQ+ population needs to be tailored accordingly to capture the multiple intersectional identities of LGBTQ+ people.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Richard J. Martino, MPH https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0121-8864

Caleb LoSchiavo, MPH https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7631-6405

Perry N. Halkitis, PhD, MPH https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1528-4128

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID data tracker. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- 2. Brownson RC., Burke TA., Colditz GA., Samet JM. Reimagining public health in the aftermath of a pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(11):1605-1610. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Webb Hooper M., Nápoles AM., Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466-2467. 10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raifman MA., Raifman JR. Disparities in the population at risk of severe illness from COVID-19 by race/ethnicity and income. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(1):137-139. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rader B., Astley CM., Sy KTL. et al. Geographic access to United States SARS-CoV-2 testing sites highlights healthcare disparities and may bias transmission estimates. J Travel Med. 2020;27(7):taaa076. 10.1093/jtm/taaa076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bedford J., Enria D., Giesecke J. et al. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1015-1018. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Calculating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) laboratory test percent positivity: CDC methods and considerations for comparisons and interpretation. Updated September 3, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/calculating-percent-positivity.html

- 8. Lutton L. Coronavirus case numbers in the United States: July 31 update. Medical Economics. July 31, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/coronavirus-case-numbers-in-the-united-states-july-31-update

- 9. Xiang F., Wang X., He X. et al. Antibody detection and dynamic characteristics in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(8):1930-1934. 10.1093/cid/ciaa461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosenberg ES., Tesoriero JM., Rosenthal EM. et al. Cumulative incidence and diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in New York. Published online May 29, 2020. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.05.25.20113050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wortham JM., Lee JT., Althomsons S. et al. Characteristics of persons who died with COVID-19—United States, February 12–May 18, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(28):923-929. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6928e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Halkitis PN., Maiolatesi AJ., Krause KD. The health challenges of emerging adult gay men: effecting change in health care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2020;67(2):293-308. 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Institute of Medicine . The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Conron KJ., Mimiaga MJ., Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1953-1960. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Poteat T., Reisner SL., Radix A. HIV epidemics among transgender women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9(2):168-173. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (updated). HIV Surveill Rep. 2020;31:1-119. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herek GM., Garnets LD. Sexual orientation and mental health. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3(1):353-375. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roberts AL., Austin SB., Corliss HL., Vandermorris AK., Koenen KC. Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2433-2441. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Remafedi G., French S., Story M., Resnick MD., Blum R. The relationship between suicide risk and sexual orientation: results of a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(1):57-60. 10.2105/AJPH.88.1.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Badgett MVL., Durso LE., Schneebaum A. New Patterns of Poverty in the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Community. Williams Institute; 2013. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8dq9d947

- 21. Ash MA., Badgett MV. Separate and unequal: the effect of unequal access to employment-based health insurance on same-sex and unmarried different-sex couples. Contemp Econ Policy. 2006;24(4):582-599. 10.1093/cep/byl010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Medley G., Lipari RN., Bose J., Cribb DS., Kroutil LA., McHenry G. Sexual orientation and estimates of adult substance use and mental health: results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review. 2016. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-SexualOrientation-2015/NSDUH-SexualOrientation-2015/NSDUH-SexualOrientation-2015.htm

- 23. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: lesbian, gay, & bisexual (LGB) adults. January 14, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2018-nsduh-lesbian-gay-bisexual-lgb-adults

- 24. Kruks G. Gay and lesbian homeless/street youth: special issues and concerns. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(7):515-518. 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90080-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Leeuwen JM., Boyle S., Salomonsen-Sautel S. et al. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual homeless youth: an eight-city public health perspective. Child Welfare. 2006;85(2):151-170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McKay T., Misra S., Lindquist C. Violence and LGBTQ+ Communities: What Do We Know, and What Do We Need to Know? RTI International; 2017. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.rti.org/sites/default/files/rti_violence_and_lgbtq_communities.pdf

- 27. LoSchiavo C., Acuna N., Halkitis PN. Evidence for the confluence of cigarette smoking, other substance use, and psychosocial and mental health in a sample of urban sexual minority young adults: the p18 cohort study. published online July 28, 2020. Ann Behav Med. 2021;55(4):308-320. 10.1093/abm/kaaa052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Logie CH., Lacombe-Duncan A., Poteat T., Wagner AC. Syndemic factors mediate the relationship between sexual stigma and depression among sexual minority women and gender minorities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(5):592-599. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krueger EA., Upchurch DM. Are sociodemographic, lifestyle, and psychosocial characteristics associated with sexual orientation group differences in mental health disparities? Results from a national population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(6):755-770. 10.1007/s00127-018-1649-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cook SH., Wood EP., Harris J., D’Avanzo P., Halkitis PN. The health of gay and bisexual men: theoretical approaches and policy implications. In: Griffith DM., Bruce MA., Thorpe RJ., eds. Men’s Health Equity: A Handbook. Routledge; 2019:343-359. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Halkitis PN., Wolitski RJ., Millett GA. A holistic approach to addressing HIV infection disparities in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):261-273. 10.1037/a0032746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hatzenbuehler ML., Pachankis JE. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):985-997. 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sears B., Conron KJ., Flores AR. The impact of the fall 2020 COVID-19 surge on LGBT adults in the US. Williams Institute. February 2021. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/covid-surge-lgbt/

- 34. Emlet CA. Social, economic, and health disparities among LGBT older adults. Generations. 2016;40(2):16-22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Knight RE., Shoveller JA., Carson AM., Contreras-Whitney JG. Examining clinicians’ experiences providing sexual health services for LGBTQ youth: considering social and structural determinants of health in clinical practice. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(4):662-670. 10.1093/her/cyt116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI., Simoni JM., Kim H-J. et al. The health equity promotion model: reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(6):653-663. 10.1037/ort0000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Halkitis PN., Kapadia F., Ompad DC., Perez-Figueroa R. Moving toward a holistic conceptual framework for understanding healthy aging among gay men. J Homosex. 2015;62(5):571-587. 10.1080/00918369.2014.987567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chance TF. “Going to pieces” over LGBT health disparities: how an amended Affordable Care Act could cure the discrimination that ails the LGBT community. J Health Care Law Policy. 2013;16(2):375. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Casey LS., Reisner SL., Findling MG. et al. Discrimination in the United States: experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(suppl 2):1454-1466. 10.1111/1475-6773.13229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aleshire ME., Ashford K., Fallin-Bennett A., Hatcher J. Primary care providers’ attitudes related to LGBTQ people: a narrative literature review. Health Promot Pract. 2019;20(2):173-187. 10.1177/1524839918778835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Movement Advancement Project . The disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on LGBTQ households in the U.S. 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.lgbtmap.org/2020-covid-lgbtq-households

- 42. Human Rights Campaign Foundation . The lives & livelihoods of many in the LGBTQ community are at risk amidst COVID-19 crisis. 2020. Accessed January 29, 2021. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/COVID19-IssueBrief-032020-FINAL.pdf

- 43. Robles G., Sauermilch D., Starks TJ. Self-efficacy, social distancing, and essential worker status dynamics among SGM people. Ann LGBTQ Public Popul Health. 2020;1(4):300-317. 10.1891/LGBTQ-2020-0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gonzales G., Loret de Mola E. Potential COVID-19 vulnerabilities in employment and healthcare access by sexual orientation. Ann LGBTQ Public Popul Health. 2021;2(2):1-21. 10.1891/LGBTQ-2020-0052 34017964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eskridge WN. Title VII’s statutory history and the sex discrimination argument for LGBT workplace protections. Yale Law J. 2017;127(2):322. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pizer JC., Sears B., Mallory C., Hunter ND. Evidence of persistent and pervasive workplace discrimination against LGBT people: the need for federal legislation prohibiting discrimination and providing for equal employment benefits. Loyola LA Law Rev. 2012;45(3):715. [Google Scholar]

- 47. US Census Bureau . QuickFacts: United States. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- 48. US Census Bureau . ACS demographic and housing estimates, 2010-2019. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?d=ACS%205-Year%20Estimates%20Data%20Profiles&tid=ACSDP5Y2018.DP05

- 49. Griffin M., Cahill S., Kapadia F., Halkitis PN. Healthcare usage and satisfaction among young adult gay men in New York City. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2020;32(4):531-551. 10.1080/10538720.2020.1799474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Griffin M., Jaiswal J., Krytusa D., Krause KD., Kapadia F., Halkitis PN. Healthcare experiences of urban young adult lesbians. Womens Health. 2020;16:174550651989982. 10.1177/1745506519899820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Badgett M., Baker KE., Conron KJ. et al. Best Practices for Asking Questions to Identify Transgender and Other Gender Minority Respondents on Population-Based Surveys (GenIUSS). Williams Institute; 2014. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/geniuss-trans-pop-based-survey/

- 52. Gottmann J. Megalopolis or the urbanization of the northeastern seaboard. Econ Geogr. 1957;33(3):189-200. 10.2307/142307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Florida R. The real powerhouses that drive the world’s economy. Bloomberg CityLab. Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-02-28/mapping-the-mega-regions-powering-the-world-s-economy

- 54. Ranganathan P., Pramesh CS., Aggarwal R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: logistic regression. Perspect Clin Res. 2017;8(3):148-151. 10.4103/picr.PICR_87_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. US Census Bureau . Zip code tabulation areas (ZCTAs). Updated August 26, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/zctas.html

- 56. Konnoth CJ. Supporting LGBT communities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Preprint. July 31, 2010. SSRN. 10.2139/ssrn.3675915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Leap W. Language, socialization, and silence in gay adolescence. In: Lovas KE., Jenkins MM., eds. Sexualities and Communication in Everyday Life: A Reader. SAGE; 2007:95-106. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Halkitis PN. Out in Time: The Public Lives of Gay Men From Stonewall to the Queer Generation. Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Coleman E. Developmental stages of the coming out process. J Homosex. 1982;7(2-3):31-43. 10.1300/J082v07n02_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Logan LS. Status homophily, sexual identity, and lesbian social ties. J Homosex. 2013;60(10):1494-1519. 10.1080/00918369.2013.819244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Galupo MP. Friendship patterns of sexual minority individuals in adulthood. J Soc Pers Relat. 2007;24(1):139-151. 10.1177/0265407506070480 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McPherson M., Smith-Lovin L., Cook JM. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):415-444. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bendavid E., Mulaney B., Sood N. et al. COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California. Published online April 30, 2020. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.14.20062463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Moscola J., Sembajwe G., Jarrett M. et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in health care personnel in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;324(9):893-895. 10.1001/jama.2020.14765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rongqing Z., Li M., Song H. et al. Early detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antibodies as a serologic marker of infection in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(16):2066-2072. 10.1093/cid/ciaa523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Almasy S., Maxouris C., Chavez N. US coronavirus cases surpass 1 million and the death toll is greater than US losses in Vietnam War. CNN. April 28, 2020. Accessed April 29, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/28/health/us-coronavirus-tuesday/index.html

- 67. New York City Department of Health . COVID-19: data. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data-testing.page

- 68. Stephenson R., Chavanduka TMD., Rosso MT. et al. Contrasting the perceived severity of COVID-19 and HIV infection in an online survey of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men during the U.S. COVID-19 epidemic. Am J Mens Health. 2020;14(5):1557988320957545. 10.1177/1557988320957545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Starks TJ., Jones SS., Sauermilch D. et al. Evaluating the impact of COVID-19: a cohort comparison study of drug use and risky sexual behavior among sexual minority men in the U.S.A. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;216(4):108260. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. McKay T., Henne J., Gonzales G., Quarles R., Gavulic KA., Garcia Gallegos S. The COVID-19 pandemic and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men in the United States. Published online May 31, 2020. SSRN. 10.2139/ssrn.3614113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Stephenson R., Chavanduka TMD., Rosso MT. et al. Sex in the time of COVID-19: results of an online survey of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men’s experience of sex and HIV prevention during the US COVID-19 epidemic. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(1):40-48. 10.1007/s10461-020-03024-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shear MD., Goodnough A., Kaplan S., Fink S., Thomas K., Weiland N. The lost month: how a failure to test blinded the U.S. to COVID-19. The New York Times. Updated April 1, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/28/us/testing-coronavirus-pandemic.html

- 73. What we know about delays in coronavirus testing . The Washington Post. Updated April 18, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/2020/04/18/timeline-coronavirus-testing/

- 74. Essentia Health . Limited availability of COVID-19 tests changes testing criteria. March 20, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.essentiahealth.org/about/media-article-library/2020/limited-availability-of-covid-19-tests-changes-testing-criteria/

- 75. Guillermina J., Douglas SM., Rosenszweig MR., Smith JP. Immigrant health: selectivity and acculturation. In: Anderson NB., Bulatao RA., Cohen B., eds. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. National Academies Press; 2004:48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Viruell-Fuentes EA., Miranda PY., Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2099-2106. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Rae M., Claxton G., Kurani N., McDermott D., Cox C. Potential costs of coronavirus treatment for people with employer coverage. KFF Health System. March 16, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/potential-costs-of-coronavirus-treatment-for-people-with-employer-coverage/

- 78. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . General business frequently asked questions. Updated February 11, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/general-business-faq.html#:~:text=Employees%20should%20not%20return%20to%20work%20until%20they%20meet%20the,note%20to%20return%20to%20work

- 79. van Dorn A., Cooney RE., Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243-1244. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30893-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rogers TN., Rogers CR., VanSant-Webb E., Gu LY., Yan B., Qeadan F. Racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality among essential workers in the United States. World Med Health Policy. 2020;12(3):311-327. 10.1002/wmh3.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. US Department of Health and Human Services . CARES Act provider relief fund: for patients. 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/for-patients/index.html

- 82. Rodriguez CH. COVID tests are free, except when they’re not. Kaiser Family Foundation. April 29, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://khn.org/news/bill-of-the-month-covid19-tests-are-free-except-when-theyre-not/

- 83. CBS News . Patients getting slammed by surprise costs related to COVID-19. CBS News. October 12, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/patients-getting-slammed-by-surprise-costs-related-to-covid-19/

- 84. Liu K., Chen Y., Lin R., Han K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect. 2020;80(6):e14-e18. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Potter EC., Tate DP., Patterson CJ. Perceived threat of COVID-19 among sexual minority and heterosexual women. Published online February 13, 2021. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers. 10.1037/sgd0000454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Marcus U., Gassowski M., Drewes J. HIV risk perception and testing behaviours among men having sex with men (MSM) reporting potential transmission risks in the previous 12 months from a large online sample of MSM living in Germany. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1111. 10.1186/s12889-016-3759-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. van der Snoek EM., de Wit JBF., Götz HM., Mulder PGH., Neumann MHA., van der Meijden WI. Incidence of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection in men who have sex with men related to knowledge, perceived susceptibility, and perceived severity of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection: Dutch MSM–Cohort Study. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(3):193-198. 10.1097/01.olq.0000194593.58251.8d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Drumhiller K., Murray A., Gaul Z., Aholou TM., Sutton MY., Nanin J. “We deserve better!”: perceptions of HIV testing campaigns among Black and Latino MSM in New York City. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(1):289-297. 10.1007/s10508-017-0950-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Halkitis PN., Zade DD., Shrem M., Marmor M. Beliefs about HIV non-infection and risky sexual behavior among MSM. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(5):448-458. 10.1521/aeap.16.5.448.48739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Halkitis PN. Managing the COVID-19 pandemic: biopsychosocial lessons gleaned from the AIDS epidemic. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(suppl 1):S39-S42. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Eyal N., Halkitis PN. AIDS activism and coronavirus vaccine challenge trials. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(12):3302-3305. 10.1007/s10461-020-02953-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Newman PA., Guta A. How to have sex in an epidemic redux: reinforcing HIV prevention in the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(8):2260-2264. 10.1007/s10461-020-02940-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Rhodes SD., Mann-Jackson L., Alonzo J. et al. A rapid qualitative assessment of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a racially/ethnically diverse sample of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men living with HIV in the US South. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(1):58-67. 10.1007/s10461-020-03014-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Santos G-M., Ackerman B., Rao A. et al. Economic, mental health, HIV prevention and HIV treatment impacts of COVID-19 and the COVID-19 response on a global sample of cisgender gay men and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):311-321. 10.1007/s10461-020-02969-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shiau S., Krause KD., Valera P., Swaminathan S., Halkitis PN. The burden of COVID-19 in people living with HIV: a syndemic perspective. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(8):2244-2249. 10.1007/s10461-020-02871-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Unwin HJT., Mishra S., Bradley VC. et al. State-level tracking of COVID-19 in the United States. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6189. 10.1038/s41467-020-19652-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Anand S., Montez-Rath M., Han J. et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in a large nationwide sample of patients on dialysis in the USA: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2020;396(10259):1335-1344. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32009-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Reid G. LGBTQ inequality and vulnerability in the pandemic. Human Rights Watch. June 18, 2020. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/18/lgbtq-inequality-and-vulnerability-pandemic

- 99. Stall R., Friedman M., Catania JA. Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health: a theory of syndemic production among urban gay men. In: Woliski RJ., Stall R., Vakdisseri RO., eds. Unequal Opportunity: Health Disparities Affecting Gay and Bisexual Men in the United States. Oxford University Press; 2008:251-274. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Halkitis PN. Managing the COVID-19 pandemic: biopsychosocial lessons gleaned from the AIDS epidemic. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(suppl 1):S39-S42. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Eliason MJ., Chinn PL. LGBTQ Cultures: What Health Care Professionals Need to Know About Sexual and Gender Diversity. Wolters Kluwer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Stewart K., O’Reilly P. Exploring the attitudes, knowledge and beliefs of nurses and midwives of the healthcare needs of the LGBTQ population: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;53:67-77. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Griffin M., Jaiswal J., King D., Singer SN., Halkitis PN. Sexuality disclosure, trust, and satisfaction with primary care among urban young adult sexual minority men. J Nurs Pract. 2020;16(5):378-387. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Halkitis PN., Krause KD. Public and population health perspectives of LGBTQ health. Ann LGBTQ Public Popul Health. 2020;1(1):1-5. 10.1891/LGBTQ.2019-0012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Griffin M., Krause KD., Kapadia F., Halkitis PN. A qualitative investigation of healthcare engagement among young adult gay men in New York City: a P18 cohort substudy. LGBT Health. 2018;5(6):368-374. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Sabin JA., Riskind RG., Nosek BA. Health care providers’ implicit and explicit attitudes toward lesbian women and gay men. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1831-1841. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ruprecht MM., Wang X., Johnson AK. et al. Evidence of social and structural COVID-19 disparities by sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in an urban environment. J Urban Health. 2021;98(1):27-40. 10.1007/s11524-020-00497-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Human Rights Campaign Foundation. PSB . The impact of COVID-19 on LGBTQ communities of color. 2020. Accessed January 29, 2021. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/COVID_19_EconImpact-CommunitiesColor052020d.pdf

- 109. Herman JL., O’Neill K. Vulnerabilities to COVID-19 among transgender adults in the U.S. UCLA, The Williams Institute. 2020. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55t297mc

- 110. Bengtsson T., Dribe M., Eriksson B. Social class and excess mortality in Sweden during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(12):2568-2576. 10.1093/aje/kwy151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Luger L. HIV, AIDS Prevention and Class and Socio-economic Related Factors of Risk of HIV Infection. WZB Discussion Paper, No. P 98-204. Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Holmes L., Enwere M., Williams J. et al. Black–White risk differentials in COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission, mortality and case fatality in the United States: translational epidemiologic perspective and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4322. 10.3390/ijerph17124322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Millett GA., Jones AT., Benkeser D. et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on Black communities. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:37-44. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Johnson A., Martin N. How COVID-19 hollowed out a generation of young Black men. ProPublica. December 22, 2020. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.propublica.org/article/how-covid-19-hollowed-out-a-generation-of-young-black-men

- 115. Bowleg L. We’re not all in this together: on COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):917. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]