Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common and aggressive tumors in the world while the accuracy of the present tests for detecting HCC is poor. A novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for HCC is urgently needed. Overwhelming evidence has demonstrated the regulatory roles of small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) in carcinogenesis. This study is aimed at analyzing the expression of a snoRNA, SNORA52, in HCC and exploring the correlation between its expression and various clinical characteristics of HCC patients. By using quantitative real-time PCR, we found that SNORA52 was downregulated in HCC cell lines (P < 0.05) and HCC tissues (P < 0.001). Correlation analysis showed that the expression of SNORA52 was obviously associated with tumor size (P = 0.011), lesion number (P = 0.007), capsular invasion (P = 0.011), tumor differentiation degree (P = 0.046), and TNM stage (P = 0.004). The disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) analysis showed that patients with lower SNORA52 expression had a worse prognosis (P < 0.001). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that SNORA52 expression was a completely independent prognostic factor to predict DFS (P = 0.009) and OS (P = 0.012) of HCC patients. Overall, our findings showed SNORA52 expression levels were downregulated in HCC tissues and correlated with multiple clinical variables, and SNORA52 was an independent prognostic factor for HCC patients, which suggested that SNORA52 could function as a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for HCC patients.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the main type of liver cancer [1] as well as the seventh most common cancer in the world [2]. As the tumor usually progresses with a concealed onset, most HCC are diagnosed at its advanced stage, which commonly indicates limited treatments and poor prognosis for patients [3]. Even after R0 surgical resection, HCC recurrence remains up to 50%-70% in postoperative five years [4]. Among that, less than 50% of those with significant portal hypertension and abnormal bilirubin could survive five years [5], which constitutes the reason why liver cancer is still the second most lethal cancer in the world, causing more than 830,000 deaths [2]. Based on this, accurate early diagnosis and long-term prognostic prediction held an important position in the clinical management of HCC. For a long time, α-fetoprotein (AFP) has been the most common tumor marker for HCC. However, the accuracy of the AFP test is disappointing, showing only about 60% of sensitivity and 80% of specificity even in its most efficient cutoff (10–20 ng/mL). Other tumor markers, including protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II), have not provided better accuracy neither [6, 7]. Therefore, a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for HCC is urgently needed.

Recently, overwhelming evidence has demonstrated the regulatory roles of different classes of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) in a carcinogenesis process [8]. Considered one of the best-characterized classes of ncRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) typically make functions in posttranscriptional modification of ribosomal and spliceosomal RNAs [9]. However, unbiased screens for cancer genes indicated some unexpected roles for snoRNAs in cancer. Emerging evidences indicated that snoRNAs were able to directly affect HCC development by regulating several pathways, such as colony formation and cellular apoptosis [10, 11]. For example, Xu et al. demonstrated that SNORD113-1 could inhibit the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and then functionally suppress HCC growth. Meanwhile, downregulated expression of SNORD113-1 was significantly associated with poor long-term survival in HCC patients [12]. Besides, SNORD126 was proved to be overexpressed in HCC and promote HCC growth via activating the PI3K-AKT pathway [13].

Small nucleolar RNA SNORA52, a novel H/ACA box snoRNA, was newly found to perform latent regulatory functions in tumor progression. Schulten et al. revealed that dysregulation of SNORA52 could indicate severe metastasis and invasion characteristics in breast as well as brain malignant tumors through comprehensive molecular biomarker identification [14]. What is more, by reference to the biofunctional predictive analysis, SNORA52 was found to be related to cell cycle, DNA replication, and repairing. However, the research of potential relationship between SNORA52 and HCC remains blank.

In the present study, we analyzed the abnormal SNORA52 expression in HCC and explored the correlation between SNORA52 expression and various clinical characteristics of HCC patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Specimens

Surgical HCC and paired adjacent liver specimens were obtained from 145 HCC patients (from 26 to 82 years old) who had hepatectomy from January 2013 to August 2014. None of the patients had received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment before hepatectomy. All patients were diagnosed with HCC by reference of histological examination.

The perioperative data of patients were collected from a hospital medical database system, including age, gender, hepatitis B virus infection, liver cirrhosis, AFP, tumor diameter, and TNM stages. Valid survival data was obtained over a period of 60 months.

2.2. Cell Culture

The human normal hepatocyte cell line QSG-7701 and several human HCC cell lines (SK-HEP-1 and Huh-7) were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, USA) containing heat-inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA), 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

2.3. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

Total RNA from cells and tissues were extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The concentration and purity of RNA were quantified by Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, 93 USA). Then, total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using HiScript II Reverse Transcriptase SuperMix with gDNA wiper (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Real-Time PCR Analysis

According to the manufacturer's instructions of Fast Start Universal SYBR Green Master ROX (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), the expressions of SNORA52 were measured through quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Ct values of the target SNORA52 were normalized in relation to GAPDH. The comparative Ct method formula 2-ΔΔCt was used to calculate the relative gene expression. All samples were tested in triplicates. The primers were designed based on SNORA52 gene sequence obtained from the gene database of NCBI. The primer sequences were as follows (5′-3′): SNORA52—GTCCATCCTAATCCCTGCCG (forward), CTAGAAGTGCCCATGACGTGAG (reverse); GAPDH—CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT (forward), GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT (reverse).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All P values shown were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The quantitative variables were evaluated by Student's t-test, while the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were applied to analyze qualitative and categorical data. Overall survival curves were plotted with the use of the Kaplan-Meier method. Overall, the association of SNORA52 expression and prognosis survival were plotted with the use of univariate analysis and multivariate Cox regression model.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SNORA52 Expression Level Was Significantly Lower in Hepatocarcinoma Cell Lines

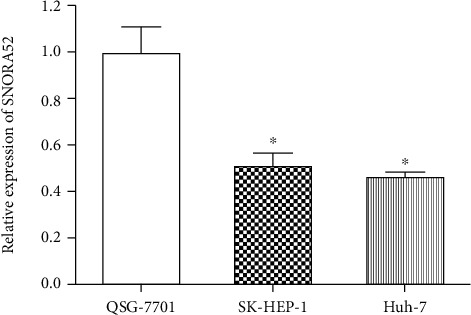

Comparing to human hepatocytes QSG-7701, significantly lower expression of SNORA52 was detected in HCC cell lines of both SK-HEP-1 and Huh-7 (P < 0.05, Figure 1), which suggested that SNORA52 might play a tumor suppressing role in HCC.

Figure 1.

Analysis of SNORA52 expression in HCC and normal liver cell lines. Compared to normal liver cell line QSG-7701, SNORA52 was notably downexpressed in several HCC cell lines: SK-HEP-1 (P = 0.013) and Hep 3B (P = 0.032). ∗P < 0.05.

3.2. SNORA52 Was Downregulated in HCC Tissues

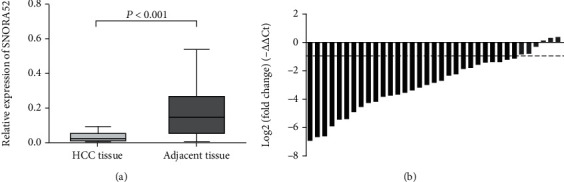

To further verify the discovery of SNORA52 downregulation in HCC, we performed the comparison of SNORA52 expression in pairs of HCC tissues and adjacent liver tissues. Consistent with cellular experiment above, we found that SNORA52 expression was significantly lower in HCC tissues than in adjacent liver tissues (P < 0.001, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative expression of SNORA52 in clinical HCC and adjacent normal tissues. (a) SNORA52 expression was significantly lower in HCC tissues than in adjacent normal tissues (P < 0.001). (b) Waterfall plot showed the fold change of SNORA52 expression. Relative expression = 2−ΔΔCt, −ΔΔCt = (CtGAPDH–CtSNORA52) of HCC tissues–(CtGAPDH–CtSNORA52) of adjacent liver tissue.

3.3. Correlation between SNORA52 Expression and Clinical Variables

According to individual SNORA52 expression, all 145 HCC patients were classified into the low and high expression subgroups. As shown in Table 1, two SNORA52 subgroups were qualitatively compared in aspects of several clinical characteristics. Correlation analysis showed that SNORA52 expression levels in HCC tissues were significantly associated with tumor size (<5 cm vs. ≥5 cm, P = 0.011), lesion number (single vs. multiple, P = 0.007), capsular invasion (absent vs. present, P = 0.011), tumor differentiation degree (high/moderate vs. low, P = 0.046), and TNM stage (I∼II vs. III∼IV, P = 0.004). These results indicated that SNORA52 expression was remarkably associated with the malignancy of HCC lesions in patients.

Table 1.

Correlation of SNORA52 and clinical characteristics in HCC patients.

| Characteristics | Total | SNORA52 expression | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 72) | High (n = 73) | |||

| Age (ys) | 0.607 | |||

| <60 | 92 | 44 (0.611) | 48 (0.658) | |

| ≥60 | 53 | 28 (0.389) | 25 (0.342) | |

| Gender | 0.138 | |||

| Female | 19 | 6 (0.083) | 13 (0.178) | |

| Male | 126 | 66 (0.917) | 60 (0.822) | |

| Hepatitis B | 0.810 | |||

| Positive | 125 | 63 (0.875) | 62 (0.849) | |

| Negative | 20 | 9 (0.125) | 11 (0.151) | |

| Cirrhosis | 1.000 | |||

| Present | 89 | 44 (0.611) | 45 (0.616) | |

| Absent | 56 | 28 (0.389) | 28 (0.384) | |

| AFP (ng/l) | 0.230 | |||

| <400 | 92 | 42 (0.583) | 50 (0.685) | |

| ≥400 | 53 | 30 (0.417) | 23 (0.315) | |

| Tumor diameter | 0.011 | |||

| <5 cm | 43 | 14 (0.194) | 29 (0.397) | |

| ≥5 cm | 102 | 58 (0.806) | 44 (0.603) | |

| Multiple lesions | 0.007 | |||

| Absent | 24 | 18 (0.250) | 6 (0.082) | |

| Present | 121 | 54 (0.750) | 67 (0.918) | |

| Vessel carcinoma embolus | 0.127 | |||

| Absent | 109 | 50 (0.694) | 59 (0.808) | |

| Present | 36 | 22 (0.306) | 14 (0.192) | |

| Microvascular invasion | 1.000 | |||

| Absent | 136 | 68 (0.944) | 68 (0.932) | |

| Present | 9 | 4 (0.056) | 5 (0.068) | |

| Capsular invasion | 0.011 | |||

| Absent | 88 | 36 (0.500) | 52 (0.712) | |

| Present | 57 | 36 (0.500) | 21 (0.288) | |

| Differentiation | 0.046 | |||

| Low | 76 | 44 (0.377) | 32 (0.438) | |

| High/moderate | 69 | 28 (0.389) | 41 (0.562) | |

| TNM stage | 0.004 | |||

| I~II | 101 | 42 (0.583) | 59 (0.808) | |

| III~IV | 44 | 30 (0.417) | 14 (0.192) | |

AFP: α-fetoprotein; TNM: tumor-node-metastasis; ∗P < 0.05. Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

3.4. Association between SNORA52 Levels and Disease-Free Survival

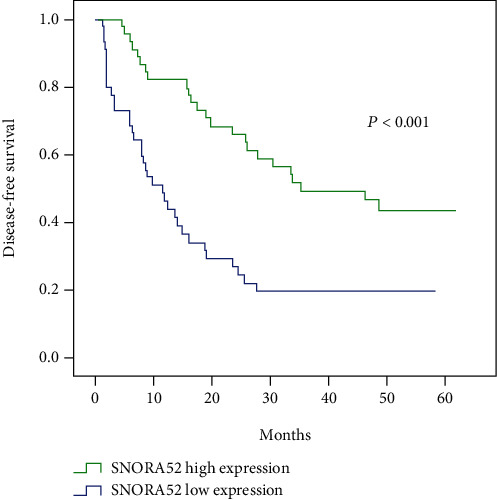

In order to explore the prognostic value of SNORA52 in HCC, we assessed the relationship between SNORA52 expression and disease-free survival (DFS) using the Kaplan-Meier method. Obviously, compared with the high SNORA52 expression group, the patients in the low SNORA52 expression group were inclined to present with higher tumor recurrence rate and shorter disease-free survival time (P < 0.001, Figure 3). This significant difference indicates that SNORA52 expression had potential capability to predict the disease-free survival of HCC patients.

Figure 3.

Cumulative disease-free survival curves of patients in high and low SNORA52 expression groups.

What is more, the following univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted to assess the independent prognostic indicators for HCC patients (Table 2). Firstly, univariate analysis showed that tumor size, lesion number, capsular invasion, vessel carcinoma embolus, TNM stage, and SNORA52 expression were strongly associated with the DFS of HCC patients. Then, multivariate analysis was performed within the above characteristics. Ultimately, it confirmed that SNORA52 expression (P = 0.009), tumor number (P = 0.007), and vessel carcinoma embolus (P = 0.014) were the completely independent prognostic factors to predict DFS of HCC patients.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of disease-free survival in HCC patients.

| Clinicopathologic parameters | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (<60 vs. ≥60) | 0.637 (0.371-1.093) | 0.102 | ||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 1.506 (0.647-3.506) | 0.342 | ||

| Hepatitis B (negative vs. positive) | 1.729 (0.785-3.810) | 0.174 | ||

| AFP (<400 vs. ≥400) | 1.355 (0.808-2.273) | 0.249 | ||

| Cirrhosis (present vs. absent) | 1.302 (0.764-2.221) | 0.332 | ||

| Microvascular invasion (present vs. absent) | 0.931 (0.337-2.573) | 0.891 | ||

| Tumor differentiation (low vs. high/moderate) | 1.018 (0.611-1.698) | 0.944 | ||

| Capsular invasion (present vs. absent) | 1.575 (0.939-2.644) | 0.085 | 1.272 (0.753-2.147) | 0.369 |

| TNM stage (I~II vs. III~IV) | 2.008 (1.190-3.386) | 0.009 | 1.094 (0.550-2.175) | 0.798 |

| Tumor diameter (<5 cm vs. ≥5 cm) | 1.875 (1.010-3.482) | 0.046 | 1.861 (0.969-3.571) | 0.062 |

| Multiple lesions (present vs. absent) | 2.481 (1.392-4.419) | 0.002 | 2.229 (1.245-3.993) | 0.007∗ |

| Vessel carcinoma embolus (present vs. absent) | 2.250 (1.260-4.019) | 0.006 | 2.195 (1.169-4.120) | 0.014∗ |

| SNORA52 expression (low vs. high) | 0.374 (0.220-0.634) | <0.001 | 0.481 (0.277-0.836) | 0.009∗ |

AFP: α-fetoprotein; TNM: tumor-node-metastasis; ∗P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3.5. Association between SNORA52 Levels and Overall Survival

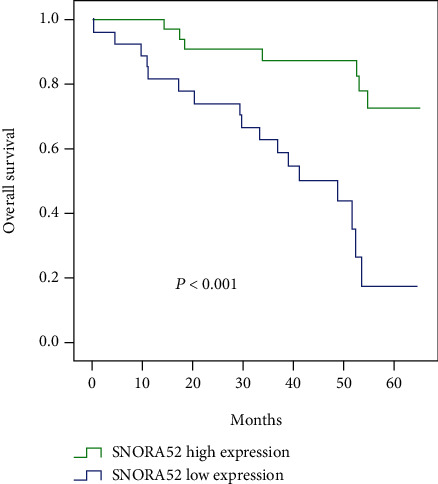

Similarly, we assessed the relationship between the SNORA52 expression and overall survival (OS) under Kaplan-Meier method. Patients from the low SNORA52 expression group were inclined to present with more severe overall survival than patients with high SNORA52 expression (P < 0.001, Figure 4), indicating that there was some potential correlation between SNORA52 expression and HCC overall survival.

Figure 4.

Cumulative overall survival curves of patients in the high and low SNORA52 expression groups.

As shown in Table 3, univariate Cox regression analysis showed that tumor size, tumor number, capsular invasion, vessel carcinoma embolus, TNM stage, and SNORA52 expression were significantly associated with overall survival of HCC patients. Moreover, following multivariate analysis confirmed that SNORA52 expression (P = 0.012), tumor size (P = 0.001), tumor number (P = 0.001), and vessel carcinoma embolus (P = 0.002) all could function as independent indicators in predicting overall survival of HCC patients.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival in HCC patients.

| Clinicopathologic parameters | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (<60 vs. ≥60) | 1.153 (0.572-2.322) | 0.691 | ||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.896 (0.344-2.331) | 0.822 | ||

| Hepatitis B (negative vs. positive) | 1.056 (0.406-2.746) | 0.911 | ||

| AFP (<400 vs. ≥400) | 1.614 (0.805-3.235) | 0.177 | ||

| Cirrhosis (present vs. absent) | 0.918 (0.453-1.861) | 0.812 | ||

| Microvascular invasion (present vs. absent) | 1.255 (0.382-4.126) | 0.708 | ||

| Tumor differentiation (low vs. high/moderate) | 0.724 (0.357-1.469) | 0.371 | ||

| Capsular invasion (present vs. absent) | 2.143 (1.070-4.293) | 0.032 | 1.132 (0.530-2.419) | 0.748 |

| TNM stage (I~II vs. III~IV) | 2.712 (1.348-5.455) | 0.005 | 0.803 (0.299-2.157) | 0.663 |

| Tumor diameter (<5 cm vs. ≥5 cm) | 5.113 (1.553-16.834) | 0.007 | 9.292 (2.457-35.137) | 0.001 |

| Multiple lesions (present vs. absent) | 3.607 (1.725-7.542) | 0.001 | 3.548 (1.654-7.612) | 0.001 |

| Vessel carcinoma embolus (present vs. absent) | 2.052 (0.919-4.582) | 0.079 | 4.519 (1.737-11.759) | 0.002 |

| SNORA52 expression (low vs. high) | 0.274 (0.127-0.594) | 0.001 | 0.359 (0.161-0.802) | 0.012 |

AFP: α-fetoprotein; TNM: tumor-node-metastasis; ∗P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

4. Discussion

As the second most lethal tumor in the world [15], HCC commonly progress without apparent symptom and almost 60% of HCC patients are firstly diagnosed in intermediate or advanced stages [16]. Thus, accurately detecting HCC at an early stage is helpful for improving overall survival [17]. Clinically, biomarkers are more appropriately used for a surveillance test while ultrasonography is not widely available owing to limited resources [18]. However, even as the most commonly used biomarker, AFP maintains a controversial clinical significance with the dissatisfactory sensitivity of 40–60% [19]. Besides, postoperative recurrence and prognosis prediction are also key obstacles in HCC treatment lacking relevant indicators [20]. Based on these, a novel biomarker is eagerly needed for the clinical treatment of HCC.

Along with more and more mechanisms of HCC tumorigenesis being revealed, newly discovered biomarkers are evaluated for diagnosis, assessment, or treatment of HCC patients [21, 22]. In recent years, mounting evidence has indicated the direct relationship between ncRNAs' dysfunction and tumor oncogenesis as well as the function of ncRNAs as assessment indicators for tumor progression [23]. Constituting almost 60% of transcripts in human cells, ncRNAs are not directly translated into proteins but exert regulatory functions in various cellular physiological as well as pathological processes [24].

Among that, snoRNA, as one kind of ncRNAs within 200 nucleotides length, is commonly found located in the nucleolus and make regulatory functions in the process of posttranscriptional modification [25]. Following the advances in the field of tumor regulation, it has proved that the dysfunction of specific snoRNA could directly induce and promote the development of various tumors [26], including HCC. Actually, Xu's team is the first to illustrate the relationship between snoRNA and HCC, which indicated that snoRNA SNORD113-1 in HCC could inactivate the intracellular phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and SMAD2/3, presenting its tumor-suppressing function [12]. On the contrary, the overexpressed SNORD126 in HCC was proved to function as the tumor-promoting snoRNA through increasing fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) expression and then activating the PI3K-AKT pathway [13]. What is more, according to a recent study by McMahon et al., HCC patients with low SNORA24 expression commonly tended to exhibit poor long-term survival [27]. Apparently, the dysregulation of some specific snoRNAs possesses direct influence on both HCC progression and a patient's condition.

In the present study, we for the first time investigated the potential association between SNORA52 expression and HCC. With validation of both cell lines and clinical specimens, we verified that SNORA52 was notably downregulated in HCC. Furthermore, it was found that the SNORA52 expression was significantly associated with HCC malignancy classification, including tumor size, lesion number, capsular invasion, tumor differentiation, and TNM stage. In addition, combining Kaplan–Meier analysis with a Cox regression model, we certified that SNORA52 expression had independent predictive capability in aspects of postoperative tumor recurrence and long-term survival. We also notice that Yang et al. did not include SNORA52 as an analytic target in their genomic analysis of snoRNAs basing on online database [28]. Given that the snoRNA expression profiles may vary from one race, nationality, database, or analytic method to another, we are prone to rely on the data acquired from our tangible specimens. Summarizing the above results, we supposed that SNORA52 played a suppressing role in the occurrence and progression of HCC.

Typically, snoRNAs were divided into C/D box and H/ACA box subtypes for their different modifications in rRNAs [29]. Among that, the H/ACA box snoRNAs, which SNORA52 belongs to, commonly modulate rRNA-related functions by pseudouridylation, while abnormal rRNA pseudouridylation can directly promote oncogenesis [30, 31]. By reference to the study of Bellodi et al. for example, the deficiency of one pseudouridine synthase dyskerin could contribute to spontaneous pituitary tumorigenesis by blocking the transcription of tumor suppressor p27 [32]. Moreover, mutations in H/ACA box RNPs, each consisting of one unique snoRNA and 4 common core proteins, accounted for the oncogenesis of prostatic carcinoma and other cancers [33]. What is more, the downregulation of NHP2, derived from one H/ACA box RNP catalyzing rRNA pseudouridylation, could result in cyst formation [34]. Taking a concrete example, Liu et al. found SNORA23 inhibited HCC progress by impairing methylation of 28S rRNA, which regulates ribosome biogenesis [35]. Based on these, we assume that the downregulated SNORA52 in HCC could cause dysfunction of some following tumor suppressor rRNAs or ribosomes, and finally, it promoted HCC oncogenesis and development. However, to validate the exact mechanisms of SNORA52 in HCC, more related researches will be needed in the future.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we for the first time found that SNORA52 expression levels were downregulated in HCC tissues and notably correlated with multiple clinical variables. Furthermore, the survival analysis indicated that SNORA52 was an independent prognostic factor for HCC patients. These results suggested that SNORA52 could function as a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for HCC patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773096) and Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (No. 2018C03085).

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Yuan Ding, Zhongquan Sun and Sitong Zhang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Augusto V. Hepatocellular carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380:1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R. L., et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alejandro F., María R., Jordi B. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasegawa K., Kokudo N., Makuuchi M., et al. Comparison of resection and ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study based on a Japanese nationwide survey. Journal of Hepatology. 2013;58(4):724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishizawa T., Hasegawa K., Aoki T., et al. Neither multiple tumors nor portal hypertension are surgical contraindications for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(7):1908–1916. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrero J. A., Feng Z., Wang Y., et al. α-Fetoprotein, Des-γ carboxyprothrombin, and lectin-bound α-fetoprotein in early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):110–118. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lok A. S., Sterling R. K., Everhart J. E., et al. Des-γ-carboxy prothrombin and α-fetoprotein as biomarkers for the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):493–502. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chun-Ming W., Ho-Ching T. F., Oi-Lin N. I. Non-coding RNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular functions and pathological implications. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2018;15:137–151. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tollervey D., Kiss T. Function and synthesis of small nucleolar RNAs. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1997;9(3):337–342. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(97)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong X. Y., Guo P., Boyd J., et al. Implication of snoRNA U50 in human breast cancer. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2009;36(8):447–454. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60134-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mei Y. P., Liao J. P., Shen J., et al. Small nucleolar RNA 42 acts as an oncogene in lung tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2011;10 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu G., Yang F., Ding C. L., et al. Small nucleolar RNA 113–1 suppresses tumorigenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Molecular Cancer. 2014;13(1):p. 216. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang X., Yang D., Luo H., et al. SNORD126 promotes HCC and CRC cell growth by activating the PI3K-AKT pathway through FGFR2. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2017;9(3):243–255. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjw048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulten H. J., Bangash M., Karim S., et al. Comprehensive molecular biomarker identification in breast cancer brain metastases. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2017;15:p. 269. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1370-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemal A., Ward E. M., Johnson C. J., et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2014, featuring survival. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2017;109(9) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park J. W., Chen M., Colombo M., et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: theBRIDGEStudy. Liver International. 2015;35(9):2155–2166. doi: 10.1111/liv.12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singal A. G., Pillai A., Tiro J. Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11(4, article e1001624) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BJ M. M., Bulkow L., Harpster A., et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in Alaska natives infected with chronic hepatitis B: a 16-year population-based study. Hepatology. 2000;32(4):842–846. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang T. S., Wu Y. C., Tung S. Y., et al. Alpha-Fetoprotein measurement benefits hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;110(6):836–844. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J. D., Hainaut P., Gores G. J., Amadou A., Plymoth A., Roberts L. R. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2019;16:589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zucman-Rossi J., Villanueva A., Nault J. C., Llovet J. M. Genetic landscape and bio- markers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(5):1226–1239.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villanueva A., Hoshida Y., Battiston C., et al. Combining clinical, pathology, and gene expression data to predict recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):1501–1512.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huo X., Han S., Wu G., et al. Dysregulated long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for tumorigenesis, disease progression, and liver cancer stem cells. Molecular Cancer. 2017;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0734-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eleni A., Jacob Leni S., Slack Frank J. Non-coding RNA networks in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2018;18:5–18. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xing Y. H., Chen L. L. Processing and roles of snoRNA-ended long noncoding RNAs. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2018;53(6):596–606. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2018.1508411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sole C., Arnaiz E., Manterola L., Otaegui D., Lawrie C. H. The circulating transcriptome as a source of cancer liquid biopsy biomarkers. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2019;58:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMahon M., Contreras A., Holm M., et al. A single H/ACA small nucleolar RNA mediates tumor suppression downstream of oncogenic RAS. Elife. 2019;8, article e48847 doi: 10.7554/eLife.48847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H., Lin P., Wu H., et al. Genomic analysis of small nucleolar RNAs identifies distinct molecular and prognostic signature in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology Reports. 2018;40(6):3346–3358. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamás K. Small nucleolar RNAs: an abundant group of noncoding RNAs with diverse cellular functions. Cell. 2002;109:145–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00718-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams Gwyn T. Are snoRNAs and snoRNA host genes new players in cancer? Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12(2):84–88. doi: 10.1038/nrc3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao P., Yang A., Wang R., et al. Germline duplication of SNORA18L5 increases risk for HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma by altering localization of ribosomal proteins and decreasing levels of p53. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:542–556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellodi C., Krasnykh O., Haynes N., et al. Loss of function of the tumor suppressor DKC1 perturbs p27 translation control and contributes to pituitary tumorigenesis. Cancer research. 2010;70(14) doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu Y. T., Meier U. T. RNA-guided isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine--pseudouridylation. RNA biology. 2014;11(12) doi: 10.4161/15476286.2014.972855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morita S., Ota R., Kobayashi S. Downregulation of NHP2 promotes proper cyst formation in Drosophila ovary. Development, growth & differentiation. 2018;60(5) doi: 10.1111/dgd.12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Z., Pang Y., Jia Y., et al. SNORA23 inhibits HCC tumorigenesis by impairing the 2’-O-ribose methylation level of 28S rRNA. Cancer Biology & Medicine. 2021;18 doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2020.0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.