Abstract

We report the response process of the Laboratory Analysis Task Force (LATF) for Unknown Disease Outbreaks (UDOs) at the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) during January 2020 to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which developed as a UDO in Korea. The advanced preparedness offered by the laboratory diagnostic algorithm for UDOs related to respiratory syndromes was critical for the rapid identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and enabled us to establish and expand the diagnostic capacity for COVID-19 on a national scale in a timely manner.

Keywords: Unknown disease outbreak, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, Diagnostic algorithm, COVID-19, Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

Since the 2000s, outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases, including the 2009 H1N1, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), have increased due to population growth, increased international travel, and climate change [1]. The initial response to emerging infectious diseases often requires outbreaks of these diseases to be treated as unknown disease outbreaks (UDOs). The World Health Organization (WHO) states that the outbreak of a disease or a cluster of diseases of unknown etiology may be due to a new or modified pathogen [2]. A UDO can pose a major threat to national health, as the diagnosis and treatment of the disease are challenging, if it spreads rapidly and the causative pathogen has not been identified during the early stage of the outbreak. Therefore, in the event of a UDO, it is critical to establish an accurate laboratory diagnostic system to prevent the spread of the disease.

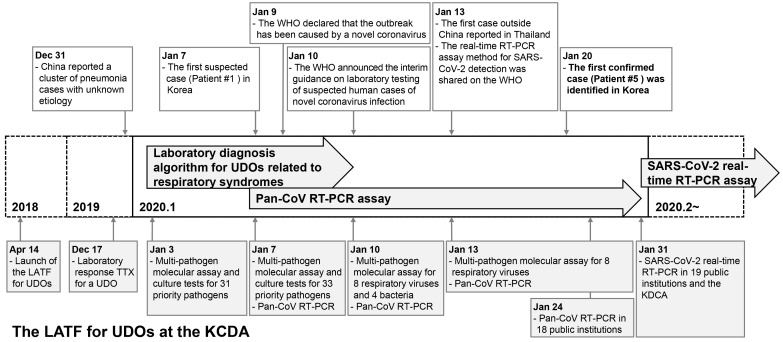

In February 2018, the WHO announced the Blueprint list of priority diseases, for which research and development efforts need to be accelerated to be prepared for a public health crisis. The list includes disease X, Ebola virus disease, Lassa fever, SARS, MERS, Nipah virus disease, and Zika. Disease X represents a serious international epidemic by a pathogen currently unknown to cause human diseases [3]. In 2018, the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) prepared a laboratory diagnostic system in response to a potential UDO. This system was successfully applied to the laboratory diagnosis of the suspected imported cases of pneumonia of unknown cause that occurred in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 [4]. This report highlights the early preparedness and response of the KDCA up to January 31, 2020, at which time the causative pathogen of COVID-19 was identified and real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR)-based diagnosis of this disease became possible (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Timeline of the response of the LATF for UDOs at the KDCA when COVID-19 was introduced as a UDO in Korea in January 2020.

Abbreviations: LATF, Laboratory Analysis Task Force; UDOs, unknown disease outbreaks; KDCA, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency; pan-CoV, pan-coronavirus; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 19; TTX, table-top exercise.

Preparedness of the KDCA for the laboratory diagnosis of a UDO

For an effective response to UDOs, countries have made efforts to rapidly detect and identify unknown pathogens in specimens collected from suspected patients. The KDCA established the “Guidelines for Unknown Respiratory Disease Outbreaks (2018)” and “Guidelines for Unknown Disease Outbreaks (2019)” in preparation for a potential UDO [5]. The KDCA also set up the Laboratory Analysis Task Force (LATF) for UDOs at the Center for Laboratory Control of Infectious Diseases, Cheongju, Korea, in 2018 to establish a laboratory diagnostic system to enable rapid action against a UDO. The LATF categorized infectious diseases into five syndromes (respiratory, hemorrhagic, rash, neurological, and diarrheal) and developed laboratory diagnostic algorithms and multi-pathogen panels for the differential diagnosis of each syndrome. In addition, the LATF planned to conduct a laboratory-response table-top exercise (TTX) on a regular basis, from 2019 onwards.

On December 17, 2019, before the outbreak of pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan, China, had been reported in Korea, the LATF had conducted a laboratory-response TTX for a UDO at the KDCA. The TTX focused on improving the response to a UDO and to a novel coronavirus based on past experience from the MERS outbreak in 2015. A novel coronavirus attracted special interest because, when identified in both animals and humans, it is likely to appear as a new variant. Based on the TTX, the need to develop a pan-coronavirus RT-PCR assay that can detect human and animal-derived coronaviruses was recognized.

Response of the KDCA to the outbreak of pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan

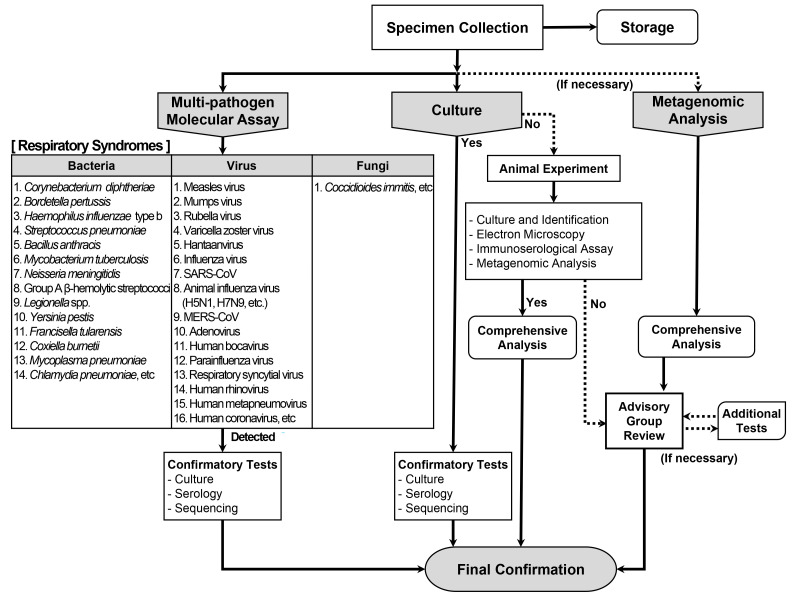

On December 31, 2019, the Hygiene Health Commission of Wuhan, China, officially announced an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology [4]. On January 3, 2020, the LATF decided to conduct laboratory diagnosis of possible cases of such pneumonia in Korea based on the laboratory diagnostic algorithm for respiratory syndromes (Fig. 2) using upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs) and lower respiratory (sputum) specimens. According to the prepared algorithm, a multi-pathogen molecular assay using real-time RT-PCR or PCR was to be performed for a total of 31 priority pathogens (16 viruses, 14 bacteria, and one fungus; Table 1). Simultaneously, culture tests were to be performed for all these pathogens. In addition to the algorithm, a pan-coronavirus RT-PCR assay was prepared and included in the multi-pathogen molecular assay, based on reports of a novel coronavirus being the suspected causative pathogen and experience from a recent TTX [6]. As there was no reported diagnostic method for the disease, the pan-coronavirus RT-PCR assay was expected to identify a new type of coronavirus. The pan-coronavirus RT-PCR assay developed by the KDCA consisted of one-step RT-PCR to amplify 251-bp and 180-bp fragments of the RNA-dependent RNA poly-merase gene located on open reading frame 1b of the coronavirus, followed by sequencing [7, 8].

Fig. 2.

Laboratory diagnostic algorithm for respiratory UDOs developed by the KDCA.

Abbreviations: UDOs, unknown disease outbreaks; KDCA, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

Table 1.

Test methods used in the multi-pathogen molecular assay for respiratory pathogens

| Pathogen | Test method | |

|---|---|---|

| Virus | Measles virus | Real-time RT-PCR |

| Mumps virus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Rubella virus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Varicella zoster virus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Hantaan virus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Influenza A and B viruses | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| SARS coronavirus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Animal influenza virus (H5N1, H7N9) | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| MERS coronavirus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Adenovirus | Real-time PCR | |

| Human bocavirus | Real-time PCR | |

| Parainfluenza virus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Human rhinovirus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Human metapneumovirus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Human coronavirus | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Enterovirus* | Real-time RT-PCR | |

| Bacteria | Corynebacterium diphtheriae | PCR |

| Bordetella pertussis | Real-time PCR | |

| Haemophilus influenzae type b | Real-time PCR | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Real-time PCR | |

| Bacillus anthracis | Real-time PCR | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Real-time PCR | |

| Neisseria meningitidis | Real-time PCR | |

| Group A β-hemolytic streptococci | Real-time PCR | |

| Legionella spp. | Real-time PCR | |

| Yersinia pestis | Real-time PCR | |

| Francisella tularensis | Real-time PCR | |

| Coxiella burnetii | Real-time PCR | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Real-time PCR | |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | Real-time PCR | |

| Chlamydia psittaci* | Real-time PCR | |

| Fungi | Coccidioides immitis | PCR |

All test methods were performed according to SOPs of the KDCA.

*The molecular assays for enterovirus and Chlamydia psittaci were added following the advice of the board members of Korean Society for Laboratory Medicine (KSLM).

Abbreviations: SOPs, standard operating procedures; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome.

On January 7, the first suspected case of COVID-19 in Korea was reported. Patient 1 was a 39-year-old woman of Chinese nationality who entered Korea from China on January 7. She showed symptoms of pneumonia with fever. Upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs in viral transport medium) and lower respiratory (sputum) specimens were collected on the same day. The specimens were inactivated at Biosafety Level (BL) 3 and subsequently transferred to a BL2 facility for a 32 multi-pathogen molecular assay, including the pan-coronavirus RT-PCR assay, at the KDCA. Two additional pathogens (enterovirus and Chlamydia psittaci) were added following the advice of the board members of Korean Society for Laboratory Medicine (KSLM; Table 1). Thus, a multi-pathogen assay was conducted for 34 pathogens in total. The results were all negative. No causative pathogen was identified in the culture tests, and the patient was discharged after recovery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Test results for suspected cases of unknown pneumonia infection in Korea up to January 21, 2020

| Case number | Specimens* received | Result reported | Sex | Age (yr) | Nationality | Symptoms | Results† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jan 7 | Jan 8 | F | 39 | Chinese | Fever, pneumonia | No results |

| 2 | Jan 13 | Jan 14 | F | 22 | Korean | Fever, cough, rhinorrhea, headache, myalgia, pneumonia | Influenza virus A/H3 |

| 3 | Jan 16 | Jan 17 | F | 21 | Korean | Fever, cough, rhinorrhea, sputum, chill, headache | Influenza virus A/H3 |

| 4 | Jan 19 | Jan 19 | M | 31 | Korean | Fever, cough, sore throat | Influenza virus B/Victoria |

| 5 | Jan 19 | Jan 20 | F | 35 | Chinese | Fever, chill, rhinorrhea, myalgia | SARS-CoV-2 |

| 6 | Jan 19 | Jan 20 | M | 28 | Chinese | Fever, cough, sputum, rhinorrhea | Influenza virus A/H3 |

| 7 | Jan 19 | Jan 20 | M | 31 | Korean | Fever, cough, sore throat, diarrhea, nausea | No results |

| 8 | Jan 20 | Jan 20 | M | 48 | Korean | Fever, cough, sputum, pneumonia | Human metapneumovirus |

| 9 | Jan 20 | Jan 21 | M | 10 | Korean | Fever, cough | Influenza virus A/H3 |

| 10 | Jan 20 | Jan 21 | F | 38 | Korean | Fever, cough | No results |

| 11 | Jan 20 | Jan 21 | M | 2 | Korean | Fever, cough | Respiratory syncytial virus B |

*Upper respiratory (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs in viral transport medium) and lower respiratory (sputum) specimens; †RT-PCR and PCR results.

Abbreviations: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR.

On January 10, the WHO announced interim guidance on laboratory testing for suspected human cases of novel coronavirus [9]. It provided recommendations on laboratory diagnostic methods for the novel coronavirus and a list of differential diagnoses of suspected cases. The multi-pathogen panel of the KDCA for differential diagnosis comprised 12 pathogens in addition to those suggested by the WHO (Table 3). The collection of upper and lower respiratory specimens and identification of causative pathogens using the laboratory diagnostic algorithm for respiratory syndromes of the KDCA complied with the WHO guidance (Fig. 2). After the WHO announcement, specimen processing and molecular testing were performed at BL2 facility, whereas the virus was cultured at BL3 facility at the KDCA, in accordance with the WHO guidance.

Table 3.

Pathogens considered for differential diagnosis for pneumonia of unknown etiology by the WHO and KDCA

| WHO | KDCA | |

|---|---|---|

| Viruses | Influenza A, B, and C viruses | Influenza-A and -B virus |

| - | Animal influenza virus (H5N1, H7N9) | |

| Adenovirus | Adenovirus | |

| MERS coronavirus | MERS coronavirus | |

| SARS coronavirus | SARS coronavirus | |

| Human coronavirus | Human coronavirus | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Respiratory syncytial virus | |

| Parainfluenza virus 1-4 | Parainfluenza virus | |

| Human metapneumovirus | Human metapneumovirus | |

| Rhinovirus | Human rhinovirus | |

| Enterovirus | Enterovirus | |

| - | Measles virus | |

| - | Mumps virus | |

| - | Rubella virus | |

| - | Varicella zoster virus | |

| - | Hantaan virus | |

| - | Human bocavirus | |

| Bacteria | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Haemophilus influenzae type b | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Group A β-hemolytic streptococci | |

| Legionella pneumophila and Legionella non-pneumophila | Legionella spp. | |

| Bacillus anthracis | Bacillus anthracis | |

| Leptospira spp. | - | |

| - | Corynebacterium diphtheriae | |

| - | Bordetella pertussis | |

| - | Neisseria meningitidis | |

| - | Yersinia pestis | |

| - | Francisella tularensis | |

| Mycobacterium spp. | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | |

| Mycoplasma spp. | Mycoplasma pneumoniae | |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | Chlamydia pneumoniae | |

| Chlamydia psittaci | Chlamydia psittaci | |

| Coxiella burnetii | Coxiella burnetii | |

| Fungi | Pneumocystis jiroveci | - |

| Fungal infections | Coccidioides immitis |

The 12 pathogens tested in addition to those suggested by the WHO are indicated in bold.

Abbreviations: KDCA, Korean Centers for Disease Control; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Response of the KDCA after the announcement of SARS-CoV-2 as the causative pathogen of unknown pneumonia

On January 9, 2020, the WHO announced that the cases of pneumonia of an unknown cause in Wuhan, China, were related to a new type of coronavirus [10]. On January 12, China released the genome of the new coronavirus to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) [11]. Initially, the novel coronavirus was named 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Later, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses officially named it severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), while the WHO named the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [12, 13].

On January 10, the LATF decided to reduce its multi-pathogen panel from 34 to 13 pathogens, including pan-coronavirus, eight respiratory viruses (influenza virus, adenovirus, human bocavirus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, human rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, and human coronavirus), and four bacteria (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella spp., and Bordetella pertussis). Thus, molecular assays of the specimen obtained from patient 2 were performed for these 13 pathogens on January 13, and the results indicated influenza virus A/H3 infection.

As COVID-19 spread rapidly across China, the first case outside China was reported in Thailand on January 13 [14]. For a more rapid laboratory response, the LATF condensed the pathogens of the molecular assay for COVID-19 to nine pathogens, including pan-coronavirus and the above-mentioned eight respiratory viruses. This protocol was applied to specimens from patients 3 and 4, with results indicating influenza virus A/H3 infection and B/Victoria infection, respectively (Table 2).

On January 19, the KDCA tested a specimen from patient 5 found in the Quarantine Station of Incheon International Airport in Korea. The patient was a 35-year-old woman of Chinese nationality from Wuhan, China, who presented with symptoms of fever, chills, rhinorrhea, and myalgia. The test results for the eight respiratory viruses were negative, but that for the pan-coronavirus was positive. Subsequent sequencing of the 251-bp and 180-bp PCR products revealed a 100% match with the SARS-CoV-2 sequence [11]. Consequently, this patient was identified as the first confirmed case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Korea on January 20 [15]. Between January 7 and 20, influenza virus A/H3 (N=4), SARS-CoV-2 (N=1), influenza virus B/Victoria (N=1), human metapneumovirus (N=1), and respiratory syncytial virus (N=1) were identified in 11 tested cases (Table 2).

Expansion of the laboratory diagnostic capacity for COVID-19 to a national scale

As COVID-19 continued to spread throughout China and cases began to emerge in countries other than China, the LATF expanded the laboratory diagnostic capacity for COVID-19 to a national scale. On January 17, the pan-coronavirus RT-PCR assay was introduced in seven out of 18 Public Institutes of Health and Environment (Seoul, Busan, Incheon, Daejeon, Gwangju, Gyeonggi, and Jeju) in Korea. For external quality assessment (EQA), four viral RNA specimens extracted from two clinical isolates of coronavirus NL63 and two clinical specimens with negative results for any respiratory virus were used. After passing the EQA program established by the KDCA, the above-mentioned institutes started conducting the pan-coronavirus RT-PCR assay on January 22. For any cases that showed positive RT-PCR results, all remaining specimens of the positive cases were transferred to the KDCA for confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection through sequencing. The remaining 11 Public Institutes of Health and Environment (Daegu, Ulsan, Sejong, Gangwon, Northern Gyeonggi, Gyeongbuk, Gyeongnam, Cheonbuk, Cheonnam, Chungbuk, and Chungnam) achieved the same level of testing ability through the process described above and started conducting the pan-coronavirus RT-PCR assay on January 24. By January 30, 500 patients were tested, and a total of seven confirmed COVID-19 cases were identified (data not shown).

On January 13, the real-time RT-PCR assay method for SARS-CoV-2 was shared on the WHO website [16]. The KDCA modified this SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR assay and provided the protocol and reagents for this assay to the 18 Public Institutes of Health and Environment. Consequently, by January 31, 19 public institutions (18 Public Institutes of Health and Environment and the Quarantine Station of Incheon International Airport) throughout Korea had acquired SARS-CoV-2 testing ability after passing the KDCA EQA. To ensure the diagnostic ability of non-governmental clinical laboratories, the KDCA and KSLM also provided the protocol and reagents for the SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR assay to the private sector in Korea [17, 18]. Through continued emergency use authorization of commercial kits by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety and the EQA program established by the KDCA and KSLM, 118 institutions, including 23 public institutions and 95 hospitals, acquired SARS-CoV-2 testing ability by March 9 and could conduct approximately 20,000 tests per day [19].

The LATF for UDO at the KDCA successfully responded to the COVID-19 outbreak in January 2020 by following the previously prepared laboratory diagnostic algorithm for UDOs related to respiratory syndromes. The laboratory diagnostic algorithm and assays, along with the experience gained from the TTX during the MERS outbreak, was essential for the rapid identification of SARS-CoV-2. Through these preparations, the LATF could effectively conduct diagnostic assays for the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 and modify them according to the rapidly changing situation, while developing and expanding the pan-coronavirus RT-PCR and SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT-PCR assays during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak.

At the time when vaccines and therapeutics against COVID-19 have not yet been developed, the KDCA has effectively suppressed the spread of COVID-19 in Korea using the 3T strategy (test, trace, and treat). We believe that the rapid and efficient identification of the causative pathogen, development of a diagnostic method, and expansion of the diagnostic capacity to a national scale are major factors contributing to disease prevention by the 3T strategy.

Through the COVID-19 response, the necessity of pathogen surveillance was recognized at the KDCA to ensure the rapid detection of UDOs. The LATF plans to establish a new pathogen surveillance system for respiratory UDOs, which will be linked to the surveillance network for SARS-CoV infection cases defined by the WHO in the near future. In addition, the LATF will strive to improve laboratory diagnostic algorithms and introduce advanced diagnostic technologies, such as metagenomic analysis, to respond to UDOs in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kim IH and Kang BH contributed to study conception and wrote the manuscript. Jang JH, Jo SK, Jeon JH, Kim JM, Jung SO, and Kim J collected the data and conducted the microbiological analyses. Seo SH and Park YE provided technical and analytical support. Kim GJ, Lee SW, Chung YS, Han MG, and Hwang KJ provided advice on methodology. Yoo CK and Rhie GE contributed to study conception and manuscript revision. Rhie GE supervised the study.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

RESEARCH FUNDING

This study was supported by the KDCA (No. 4800-4837-301).

REFERENCES

- 1.Petersen E, Petrosillo N, Koopmans M ESCMID Emerging Infections Task Force Expert Panel, author. Emerging infections-an increasingly important topic: review by the Emerging Infections Task Force. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, author. Disease outbreaks of unknown etiology. https://www.who.int/environmental_health_emergencies/disease_outbreaks/unknown_etiology/en/ Updated on Aug 15, 2020.

- 3.Mehand MS, Al-Shorbaji F, Millett P, Murgue B. The WHO R&D Blueprint: 2018 review of emerging infectious diseases requiring urgent research and development efforts. Antiviral Res. 2018;159:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization, author. [Updated on Jan 5, 2020];Pneumonia of unknown cause - China. https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/

- 5.Kim EK, Moon SJ, Lee SW. Procedure for responding to disease outbreaks of unexplained etiology. [updated on Nov 19];PHWR. 2019 12:755–8. http://www.kdca.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a30501000000&bid=0031&list_no=144126&act=view . [Google Scholar]

- 6.ProMED, author. [Updated on Jan 6, 2020];Undiagnosed pneumonia - China (HU) (04): Hong Kong surveillance. https://promedmail.org/promed-post/?id=6874277 .

- 7.Vijgen L, Moës E, Keyaerts E, Li S, Van Ranst M. A pancoronavirus RT-PCR assay for detection of all known coronaviruses. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;454:3–12. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-181-9_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lelli D, Papetti A, Sabelli C, Rosti E, Moreno A, Boniotti MB. Detection of coronaviruses in bats of various species in Italy. Viruses. 2013;5:2679–89. doi: 10.3390/v5112679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization, author. [Updated on Jan 10, 2020];Laboratory testing of human suspected cases of novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection Interim guidance, 10 January 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330374 .

- 10.World Health Organization, author. [Updated on Jan 9, 2020];WHO Statement regarding cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China. https://www.who.int/china/news/detail/09-01-2020-who-statement-regarding-cluster-of-pneumonia-cases-in-wuhan-china .

- 11.World Health Organization, author. [Updated on Jan 12, 2020];Novel coronavirus - China. https://www.who.int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/

- 12.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, author. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536–44. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization, author. [Updated on Feb 11, 2020];Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it .

- 14.World Health Organization, author. [Updated on Jan 13, 2020];WHO statement on novel coronavirus in Thailand. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/13-01-2020-who-statement-on-novel-coronavirus-in-thailand .

- 15.Kim JY, Choe PG, Oh Y, Oh KJ, Kim J, Park SJ, et al. The first case of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia imported into Korea from Wuhan, China: implication for infection prevention and control measures. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e61. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization, author. [Updated on Jan 2020];Diagnostic detection of Wuhan coronavirus 2019 by real-time RT-PCR. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/wuhan-virus-assay-v1991527e5122341d99287a1b17c111902.pdf .

- 17.Hong KH, Lee SW, Kim TS, Huh HJ, Lee JH, Kim SY, et al. Guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2020;40:351–60. doi: 10.3343/alm.2020.40.5.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sung H, Roh KH, Hong KH, Seong MW, Ryoo N, Kim HS, et al. COVID-19 molecular testing in Korea: practical essentials and answers from experts based on experiences of emergency use authorization assays. Ann Lab Med. 2020;40:439–47. doi: 10.3343/alm.2020.40.6.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung H, Yoo CK, Han MG, Lee SW, Lee H, Chun S, et al. Preparedness and rapid implementation of external quality assessment helped quickly increase COVID-19 testing capacity in the Republic of Korea. Clin Chem. 2020;66:979–81. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]