Dear Editor,

Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration (BLL-11q) is a new provisional classification in the revised fourth edition of WHO classification of lymphomas that resembles Burkitt lymphoma (BL) morphologically and phenotypically, but has unique features, including gains in 11q23.2–23.3 and losses of 11q24.1–qter, with no MYC translocation [1]. BLL-11q predominantly occurs in young adult males, and characteristic cytogenetic features have been frequently observed in post-transplant patients [2–4]. However, the association between BLL-11q and immune deficiency remains unclear due to the limited number of cases [2, 4–6]. We report a case of BLL-11q with HIV co-infection in East Asia, and review previous cases of BLL-11q with immunodeficiency. The Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, approved this study (IRB No: SMC-2020-05-125) and waived the need for informed consent.

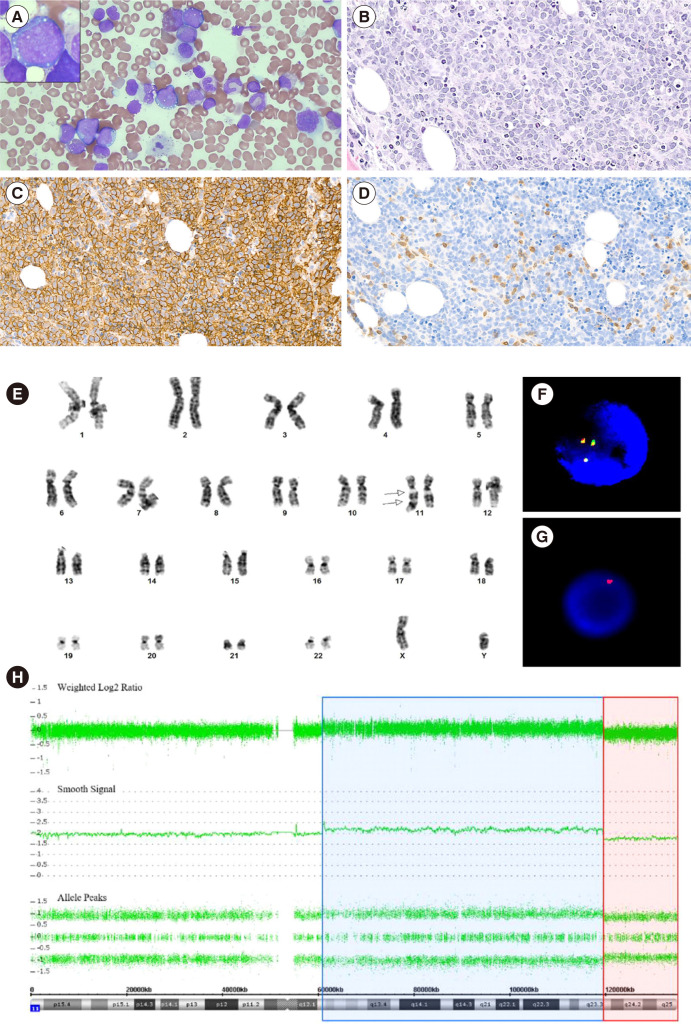

A 23-year-old male who was previously healthy was admitted to Samsung Medical Center in January 2020 for investigation of a palpable mass on the left axilla and back pain. Axillary lymph-node biopsy was positive for CD10, BCL6, and Ki-67 (>90%), and negative for BCL2, CD3, and MUM-1 (IRF-4). FISH was negative for BCL2 or BCL6 rearrangement. Bone marrow (BM) aspirate and section revealed an increase in medium- to large-sized lymphoma cells (Fig. 1A and 1B). Flow cytometry was performed on BM aspirates. After staining with monoclonal antibodies against B-cell associated antigens, data acquisition and analysis were performed using the FACSLyric flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and Kaluza flow cytometry analysis software (Beckman Coulter Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA), respectively. Lymphoma cells were positive for CD10, CD19, CD20, and cCD79a, moderately positive for cCD22, and negative for CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), CD5, and kappa/lambda surface immunoglobulins. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded BM sections using monoclonal antibodies against CD3, CD20, CD34, and TdT (DAKO, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and showed lymphoma cells diffusely positive for CD20 (Fig. 1C) and reactive T cells positive for CD3 (Fig. 1D). Epstein-Barr virus in-situ hybridization was negative. Chromosomal analysis revealed 46,XY,der(11)dup(11)(q24q13)del(q24)[18]/46,XY[2] (Fig. 1E). FISH analysis using LSI IGH/MYC/CEP8 Tri-Color Dual Fusion probe (Vysis, Abbott Park, IL, USA), LSI KMT2A (MLL) Dual-Color Break Apart probe (Vysis), and TelVysion 11q SpectrumOrange probe (Vysis) indicated the presence of 11q aberrations (Fig. 1F, 1G), with no MYC rearrangement.

Fig. 1.

Bone marrow findings in Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration. (A) Bone marrow aspirate smear revealed medium- to large-sized lymphoma cells with finely clumped chromatin, variably prominent nucleoli, moderate amounts of deeply basophilic cytoplasm, with or without lipid vacuoles (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×400 and ×1,000). (B) Bone marrow biopsy section revealed diffuse infiltration of lymphoma cells composed of medium- to large-sized cells (H & E stain, ×200). On immunohistochemical staining, (C) lymphoma cells were diffusely positive for CD20, and (D) reactive T cells were positive for CD3 (×200). (E) Chromosome analysis showed an abnormal chromosome 11, including inverted duplication of the part of the long arm between 11q24 and 11q13 and terminal deletion of the long arm from 11q24 to 11ter (arrow). On interphase fluorescence in-situ hybridization, (F) KMT2A (MLL) Dual-Color Break Apart probe (Vysis) showed three green/orange (yellow) fusion signals indicating a gain of 11q23.3, and (G) Telomere 11q SpectrumOrange probe (Vysis) showed a single orange signal, indicating a loss of 11q24. (H) Chromosomal microarray analysis showed a copy-number gain of 11q12.2 q23.3 (blue) followed by an adjacent distal loss of 11q23.3 q25 (red).

Chromosomal microarray analysis was conducted using Gene-Chip System 3000Dx v.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a CytoScan Dx Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The results showed a 58.5 Mb copy number gain on 11q12.2q23.3 (chr11:60,902,421–119,465,669) and a 15.4 Mb copy number loss on 11q23.3q25 (chr11:119,465,715–134,938,470) (Fig. 1H). Targeted next-generation sequencing using a NextSeq 550Dx instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with IDT xGen pre-designed/custom probes (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) of 90 genes linked with B-cell lymphoma identified variants in GNA13, ARID1A, KMT2D, TP53, PTEN, and BRAF. Additional workups showed positive results for both screening and confirmative tests for HIV infection, with a CD4+ T-cell count of 228/μL. Finally, the patient was diagnosed as having stage IV BLL-11q with HIV and late latent syphilis co-infection. Subsequently, he was treated with dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R) for B-cell lymphoma.

After five cycles of chemotherapy over four months, together with markedly improved imaging findings and no involvement of lymphoma in the follow-up BM study, the patient achieved remission. After four months of antiretroviral therapy, HIV RNA was below the detection limit, with an increase in CD4+ T cells by 316 cells/μL.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of BLL-11q accompanied by HIV infection in East Asia. We identified the 11q aberrations by cytogenetic studies, suggesting that these technical approaches may be useful for the diagnosis of BLL-11q.

Even though flow cytometry indicated mature B-cell lymphoma in our case, there was no expression of surface immunoglobulins. Surface immunoglobulin light chain-negative B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) as well as lymphomas in HIV-infected patients tend to be clinically aggressive [6–8]. However, our patient had a good performance status with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 0, with no systemic symptoms. These features may support the favorable outcome of BLL-11q.

As previously reported in BLL-11q [5], we detected variants in GNA13, ARID1A, and KMT2D, which are frequently found in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL), but not in BL. This corroborates that BLL-11q has similar clinicopathological and immunophenotypic features as BL, but different molecular features. Thus, the hypothesis that BLL-11q is a discrete entity of high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL) rather than a subdivided entity belonging to BL needs to be considered.

The relationship between BLL-11q and immunocompromised conditions has not been fully evaluated [5]. A literature review revealed seven cases of BLL-11q in immunodeficient settings (Table 1). These cases occurred strictly in males, as women are protected by estrogens against the proliferation of B-cell NHLs [9]. Interestingly, all cases with HIV infection, including our patient, showed either an advanced tumor stage or an aggressive clinical course, but had a good response to chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinicopathological features of cases of Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration with immunodeficient status

| Case number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Belgium | Belgium | Belgium | USA | Germany | Germany | Spain | Korea | |

| Reference | Ferreiro, et al. (2015) [4] | Ferreiro, et al. (2015) [4] | Ferreiro, et al. (2015) [4] | Ard, et al. (2018) [6] | Wagener, et al. (2019) [2] | Wagener, et al. (2019) [2] | Gonzalez-Farre, et al. (2019) [5] | This study | |

| Age (yr)/Sex | 54/M | 68/M | 44/M | 55/M | 52/M | 10/M | 37/M | 23/M | |

| Ann Arbor staging | IIA | IA | IVB | NR | NR | NR | IV | IV | |

| Immune status | Post-transplant (heart) | Post-transplant (liver) | Post-transplant (kidney) | HIV, Crohn’s disease, syphilis | Post-transplant (NR) | Immune defect | HIV | HIV, syphilis | |

| Tumor localization | Waldeyer ring | LN | Testis | Parotid gland | Appendix | Iliac crest | Axillary LN, Extranodal | Axillary LN, BM | |

| IHC | MYC (%) | – | Weak+ (25) | Weak+ (25) | Weak+ (60) | – | – | – | + (70) |

| BCL2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | - | |

| BCL6 | + | + | + | + | NR | NR | + | + | |

| CD10 | + | + | + | NR | + | + | + | + | |

| CD20 | + | + | + | + | + | + | NR | + | |

| TdT | – | – | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | – | |

| MUM1/IRF4 | – | – | – | – | NR | NR | – | – | |

| LMO2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | NR | |

| Ki-67 (%) | 90 | 99 | 99 | > 95 | > 90 | 100 | Very high | > 90 | |

| EBV | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Gene trans-location (FISH) | MYC | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| BCL2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | – | – | NR | – | |

| BCL6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | – | – | NR | – | |

| Karyotype | 44-47,XY,add(7)(p22) [3],der(11)dup(11) (q23.3q13)t(8;11) (q22;q23.3),+1-2mar[cp5] |

42-44,XY,-4,add(10) (p11),der(11)t(11;18) (q23.3;q12)[cp4] |

NR | Gain of 11q23-24, loss of 11q24- tel, trisomy 7, trisomy12, complex aberrations on ch.10, overall tetrasomy | NR | NR | NR | 46,XY,der(11)dup(11) (q24q13)del(q24) [18]/46,XY[2] | |

| Diagnostic method(s) | Karyotyping, FISH, aCGH | Karyotyping, FISH, aCGH | aCGH | FISH, microarray | FISH, microarray | FISH, microarray | FISH, microarray | Karyotyping, FISH, microarray | |

| Treatment | CHOP-R | CHOP-R | CHOP-R | DA-EPOCH-R | NR | NR | CHOP-R or Burkimab | DA-EPOCH-R | |

| CNS prophylaxis | NR | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | + | + | |

| Response, Follow-up | CR, 99 m | PD, 4 m | CR, 5 m | Remission, 24 m | NR | NR | CR, 112 m | Remission | |

| Outcome | Alive | Dead, disease related | Dead, disease unrelated | Alive | NR | NR | Alive | Alive | |

Abbreviations: Age (yr), age at diagnosis in years; M, male; F, female; NR, not reported; Post-transplant, transplantation with graft site and having immunosuppression; Tumor localization, histopathologically confirmed tumor-involved sites based on analysis of biopsy specimens; LN, lymph node; BM, bone marrow; IHC, immunohistochemistry; -, negative; +, positive; TdT, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus status determined using EBV-encoded small RNAs via in-situ hybridization; ch., chromosome; aCGH, array comparative genomic hybridization; CHOP-R, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, rituximab; DA-EPOCH-R, dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, rituximab; CNS prophylaxis, central nervous system prophylaxis with intrathecal methotrexate; CR, complete remission; PD, progressive disease; m, months.

The optimal therapy for BLL-11q remains controversial. Despite the poor prognostic factors in our patient, such as advanced-stage disease, BM involvement, and low absolute lymphocyte count, low-intensity chemotherapy (DA-EPOCH-R) was effective. These outcomes strengthen the favorable prognosis of BLL-11q and suggest consideration of dose-reduced therapy for this subgroup of lymphomas [3, 10].

Our study results suggest that detailed histopathological and cytogenetic studies are especially important in young patients with underlying immunodeficiency who exhibit morphologies of BL, DLBCL, and HGBCL. The favorable prognosis of BLL-11q emphasizes the significance of accurate diagnosis in such cases. Further research will be needed to elucidate the molecular pathogenesis of and optimal therapeutic strategies for this malignancy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kim JA wrote the manuscript. Kim SJ managed the patient and provided the clinical information. Kim HY, Kim HJ, and Kim SH contributed to the interpretation of the results and revision of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

RESEARCH FUNDING

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, et al., editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. IARC Press; Lyon: 2017. p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagener R, Seufert J, Raimondi F, Bens S, Kleinheinz K, Nagel I, et al. The mutational landscape of Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration is distinct from that of Burkitt lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:962–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-864025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Au-Yeung RKH, Arias Padilla L, Zimmermann M, Oschlies I, Siebert R, Woessmann W, et al. Experience with provisional WHO-entities large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4-rearrangement and Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in paediatric patients of the NHL-BFM group. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:753–63. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreiro JF, Morscio J, Dierickx D, Marcelis L, Verhoef G, Vandenberghe P, et al. Post-transplant molecularly defined Burkitt lymphomas are frequently MYC-negative and characterized by the 11q-gain/loss pattern. Haematologica. 2015;100:e275–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.124305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez-Farre B, Ramis-Zaldivar JE, Salmeron-Villalobos J, Balagué O, Celis V, Verdu-Amoros J, et al. Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration: a germinal center-derived lymphoma genetically unrelated to Burkitt lymphoma. Haematologica. 2019;104:1822–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.207928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ard KL, Kelly HR, Gandhi RT, Louissaint A., Jr Case 9-2018: A 55-year-old man with HIV infection and a mass on the right side of the face. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1143–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1800321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coté TR, Biggar RJ, Rosenberg PS, Devesa SS, Percy C, Yellin FJ, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma among people with AIDS: incidence, presentation and public health burden. AIDS/Cancer Study Group. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:645–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971127)73:5<645::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsushita H, Nakamura N, Tanaka Y, Ohgiya D, Tanaka Y, Damdinsuren A, et al. Clinical and pathological features of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas lacking the surface expression of immunoglobulin light chains. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50:1665–70. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2011-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horesh N, Horowitz NA. Does gender matter in non-hodgkin lymphoma? Differences in epidemiology, clinical behavior, and therapy. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2014;5:e0038. doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gastwirt JP, Roschewski M. Management of adults with Burkitt lymphoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2018;16:812–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]