Abstract

Background

Galectins are proteins that bind β-galactosides such as N-acetyllactosamine present in N-linked and O-linked glycoproteins and that seem to be implicated in inflammatory and immune responses as well as fibrotic mechanisms. This preliminary study investigated serum galectins as clinical biomarkers in lung transplant patients with chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD), phenotype bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS).

Materials and Methods

Nineteen lung transplant patients [median age (IQR), 55 (45–62) years; 53% males] were enrolled in the study. Peripheral blood concentrations of galectins-1, 3 and 9 were determined with commercial ELISA kits.

Results

Galectin-1 concentrations were higher in BOS than in stable LTX patients (p = 0.0394). In logistic regression analysis, testing BOS group as dependent variable with Gal-1 and 3 as independent variables, area under the receiver operating characteristics (AUROC) curve was 98.9% (NPV 90% and PPV 88.9%, p = 0.0003). With the stable LTX group as dependent variable and Gal-1, 3 and 9 as independent variables, AUROC was 92.6% (NPV 100% and PPV 90%, p = 0.0023). In stable patients were observed an inverse correlation of Gal-3 with DLCO% and KCO%, and between Gal-9 and KCO%.

Conclusion

Galectins-1, 3 and 9 are possible clinical biomarkers in lung transplant patients with diagnostic and prognostic meaning. These molecules may be directly implicated in the pathological mechanisms of BOS. The hypothesis that they could be new therapeutic targets in BOS patients is intriguing and also worth exploring.

Keywords: Galectin-1, Galectin-3, Galectin-9, Lung transplantation, Chronic lung allograft dysfunction, Biomarkers

Introduction

Lung transplant (LTX) is a lifesaving treatment option for patients with end-stage lung diseases, including emphysema, cystic fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension, unresponsive to maximal medical therapy or for whom no effective medical or other surgical alternative exists [1–4]. Long-term survival after LTX is still challenging and chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) remains a leading cause of death [5]. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) is the most common form of CLAD and appears to begin with an inflammatory stage, characterized by lymphocytic peribronchiolar infiltrates, and then progresses to a fibroproliferative stage with proliferation of fibroblasts and accumulation of collagen under the bronchiolar epithelium, leading to obliteration of the airway lumen [6]. A restrictive form of CLAD, termed restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS), has also recently been recognized [7].

Galectins (Gal) are proteins that bind β-galactosides, such as N-acetyllactosamine, present in N-linked and O-linked glycoproteins. Galectin structure features one or two carbohydrate recognition domains, on the basis of which they are classified as prototype galectins (e.g. Gal-1), chimera galectins (e.g. Gal-3) and tandem-repeat galectins (e.g. Gal-9). Galectins have numerous biological functions: they participate in cross-talk and maintenance of cell architecture, facilitating interactions between cells and components of the extracellular matrix [8]. These cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, as well as signalling pathways on the cell surface, influence and modulate cell functions, such as inflammatory and immune responses [9]. Depending on the type of inflammatory stimulus, the microenvironment and the target cells involved, these proteins may be associated with pro- or anti-inflammatory responses [10]. Galectins are also implicated in pulmonary fibrosis, where their inhibition may be useful in therapeutic management [11–14]. Some reports show that malignant transformation in human cancer patients is often associated with altered galectin expression [15]. Galectins play a crucial role in the homeostasis of inflammation through their apoptotic effect on activated leukocytes [11, 16]. Release of Gals-1 and 3 initiates an inflammatory response in several ways, including binding of neutrophils to the endothelium, trafficking of neutrophils through the extracellular matrix bound to laminins and fibronectin, and acting as chemotactic agents towards the site of inflammation [12, 13]. Once neutrophils have been trafficked to the scene, galectins-1 and 3 then contribute to the respiratory burst that enables neutrophils to destroy cell contents or invading pathogens [8, 17]. Some data in kidney and liver transplantation have been published regarding their potential role in graft tolerance [18, 19], but no data is available on the role of galectins in LTX patients. In the present study our aim was to explore the potential of serum concentrations of galectins-1, 3 and 9 as clinical biomarkers in lung transplant patients with BOS.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Nineteen lung transplant patients [median age (IQR), 55 (45–62) years; 53% males] monitored at the Siena Regional Referral Centre for Sarcoidosis and other Interstitial Lung Diseases were enrolled in the study. Nine patients [median age (IQR), 51 (49–63) years; 33% males] were considered stable (CLAD-free), whereas the other ten patients [median age (IQR), 58 (37–62) years; 70% males] had CLAD (BOS phenotype). A healthy control group (HC) was also included (n = 9; median age (IQR), 45 (35–54) years; 33% males).

CLAD was defined in presence of a substantial and persistent decline (≥ 20%) in measured FEV1 value from the reference (baseline) value. The baseline value was computed as the mean of the best two postoperative FEV1 measurements (taken > 3 weeks apart). BOS phenotype was assumed in case of a fall in FEV1 ≥ 20% (compared with baseline) in presence of an obstruction pattern at spirometry (FEV1/FVC < 0.7) without persistent radiologic pulmonary opacities (parenchymal opacities and/or increasing pleural thickening consistent with a diagnosis of pulmonary and/or pleural fibrosis and likely to cause a restrictive physiology, rather than the airway-based changes consistent with bronchiectasis) [6]. All included patients met BOS diagnostic criteria, patients with RAS were excluded.

All clinical and functional data was collected retrospectively and entered in a specific database. Patients gave their written informed consent to participation in the study, which was approved by our local ethics committee (Respir1, Prot n 15,732, 16 September 2019).

Lung Function Tests

Lung function measurements were performed according to ATS/ERS standard procedure [20], using a Jaeger body plethysmograph with corrections for temperature and barometric pressure: forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), total lung capacity (TLC), residual volume (RV), diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and carbon monoxide transfer coefficient (KCO) for alveolar volume. All parameters were expressed as percentages of predicted values. They were recorded at sampling time and after LTX in order to establish CLAD stage.

Galectin Assay

Peripheral blood concentrations of galectins-1, 3 and 9 were determined with the Human Galectin quantikine ELISA kit (R&D System, Minneapolis, USA). Nine serum samples were also collected from the healthy volunteers and assayed. The serum concentrations of Gal-1 [mean (IQR), 18.1 (13.9–28.2) ng/ml], Gal-3 [mean (IQR), 6.73 (2.40–15.7) ng/ml] and Gal-9 [mean (IQR), 7 (3.1–10.4) ng/ml] of controls were in line with those indicated by the kit manufacturer [21].

Statistical Analysis

The data did not show a normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney test was used for comparison of two variables, while non-parametric one-way ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test) and the Dunn test were used for multiple comparisons. The Chi-squared test was used for categorical variables, as appropriate. According to the presence of BOS phenotype, our population were divided in CLAD-free and CLAD-BOS group.

We also performed a logistic regression with HC as dependent variable against CLAD-BOS (or CLAD-free) to assess the potential of the serum galectins for differential diagnosis between the groups. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predicted values (PPV and NPV, respectively) were calculated for cut-offs of the different variables. Correlations between variables were studied by Spearman correlation and linear regression. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis and graphic representation of the data was performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Unsupervised and supervised Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed by ClustVis (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis).

Results

The main characteristics of our population, including serum concentrations of galectins-1, 3 and 9 and lung function parameters, are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristic of population including age, gender, smoking habit, underling lung diseases and comorbidities, galectins and lung function test parameters

| Parameters | CLAD-free (n = 9) | CLAD-BOS (n = 10) | Healthy controls (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 49 (51–63) | 37 (58–62) | 25 (30–58) | |

| Gender (male/female) | 3/6 | 7/3 | 2/7 | |

| Smoking habit (never/former) | 6/3 | 4/6 | 4/5 | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 4 (44.5%) | 3 (30%) | 0.51 | |

| COPD | 2 (22.3%) | 3 (30%) | 0.70 | |

| Cystic fibrosis | 2 (22.3%) | 4 (40%) | 0.40 | |

| Other diagnosis | – | – | – | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (22.3%) | 5 (50%) | 0.21 | |

| Arterial hypertension | 1 (11.2%) | 3 (30%) | 0.31 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 2 (22.3%) | 4 (40%) | 0.40 | |

| Osteoporosis | 4 (44.5%) | 7 (70%) | 0.58 | |

| Galectins concentration | ||||

| Gal-1 (mg/dl) | 22.7 (18.7–29.4) | 29.9 (25.6–58.1) | 13.1 (11.6–16.6) | 0.0026 |

| Gal-3 (mg/dl) | 10.7 (4.6–17.6) | 12.1 (9.4–16.9) | 6.2 (3–8.1) | 0.0154 |

| Gal-9 (mg/dl) | 8.6 (7.3–15.6) | 12.3 (9.3–19.3) | 3.8 (2.1–6.1) | 0.0003 |

| LFTs | ||||

| FVC (ml) | 2460 (2150–3445) | 2765 (2273–2945) | > 0.999 | |

| FVC% | 90 (71–99) | 69 (61–85) | 0.0877 | |

| FEV1 (ml) | 2090 (1710–2580) | 1800 (1303–2138) | 0.2359 | |

| FEV1 (%) | 87 (66–91) | 57 (42–71) | 0.0079 | |

| FEV1/VC | 81 (73–87) | 64 (62–70) | 0.0293 | |

| DLCO (%) | 69 (55–78) | 62 (54–85) | 0.7243 | |

| KCO (%) | 82 (72–95) | 92 (71–108) | 0.6304 | |

All data were expressed as median and Interquartile range

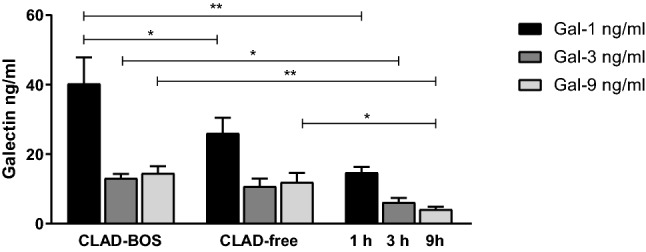

Galectin-1, 3 and 9 concentrations were significantly higher in CLAD-BOS patients than in HC (p = 0.0018, p = 0.0122 and p = 0.0003, respectively). Galectin-1 concentrations were higher in CLAD-BOS than in CLAD-free patients (p = 0.0394); Gal-9 concentrations were higher in the CLAD-free group than in the HC group (p = 0.0231) (Table 1, Fig. 1). No difference in Galectin-1, 3 and 9 concentrations accordingly underling lung disease or other basal characteristics were observed.

Fig. 1.

Galectin concentrations in LTX patients, including CLAD and stable patients and healthy controls. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005

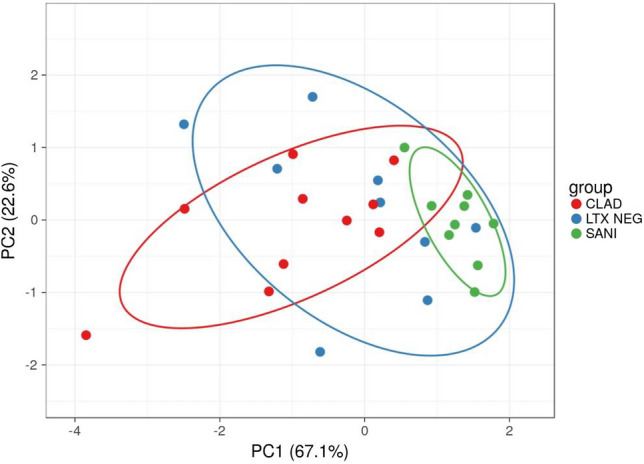

PCA analysis was performed with the results obtained for serum concentrations of galectins. The eigenvalue percentage significance of the PCs was 99.9%. Intraclass dispersion occurred mainly along the first and second PCs. The three groups separated along the first PC (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Unit variance scaling is applied to rows; SVD with imputation is used to calculate principal components. X and Y axis show principal component 1 and principal component 2 that explain 67.1% and 22.6% of the total variance, respectively. Prediction ellipses are such that with probability 0.95, a new observation from the same group will fall inside the ellipse. N = 28 data points. LTX neg stable LTX; CLAD chronic allograft lung dysfunction

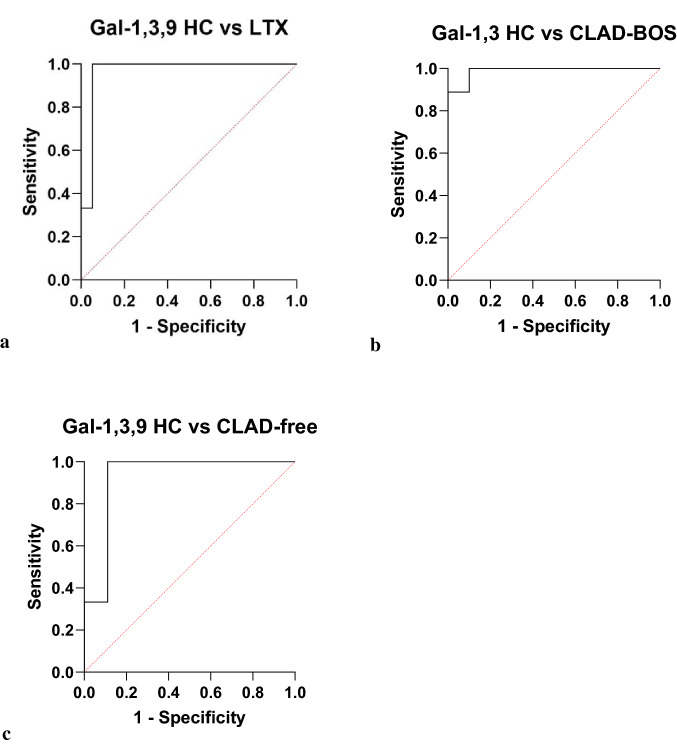

Testing the HC group as dependent variable by logistic regression, with Gal-1, 3 and 9 as independent variables, we obtained an area under the ROC (AUROC) curve of 96.5% (95% CI 89–100, NPV 100% and PPV 90%, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3a). When we tested the CLAD-BOS group as dependent variable with Gal-1 and 3 as independent variables, AUROC was 98.9% (95% CI 95–100, NPV 90% and PPV 88.9%, p = 0.0003) (Fig. 3b). With the CLAD-free group as dependent variable and Gal-1, 3 and 9 as independent variables, AUROC was 92.6% (95% CI 78–100, NPV 100% and PPV 90%, p = 0.0023) (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

a HC group as dependent variable and Gal-1,3,9 as independent variables, areas under the ROC (AUROC) curve of 96.5% (95% CI 89–100, NPV 100% and PPV 90%, p < 0.0001). b CLAD group as dependent variable with Gal-1 and 3 as independent variables, AUROC was 98.9% (95% CI 95–100, NPV 90% and PPV 88.9%, p = 0.0003). c stable LTX group as dependent variable with Gal-1,3,9 as independent variable, AUROC was 92.6% (95% CI 78–100, NPV 100% and PPV 90%, p = 0.0023)

A significant inverse correlation of Gal-3 with DLCO% and KCO% was observed among CLAD-free, while Gal-9 showed inverse correlations with KCO% among stable patients, and with measured FVC in CLAD-BOS patients (the latter with borderline significance, but with a good Rho coefficient: − 0.714, p = 0.058) (Table 2). No significant correlations were observed between Gal-1 concentrations and lung function parameters (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main correlations between Galectin concentrations and LFT parameters

| CLAD-free | Rho coefficient | P value | CLAD-BOS | Rho coefficient | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gal-1 | FVC% | 0.217 | 0.581 | Gal-1 | FVC% | − 0.275 | 0.507 |

| FVC(ml) | 0.400 | 0.291 | FVC (ml) | − 0.190 | 0.665 | ||

| FEV1% | 0.517 | 0.162 | FEV1% | − 0.238 | 0.582 | ||

| FEV1(ml) | 0.550 | 0.133 | FEV(ml) | 0.095 | 0.840 | ||

| DLCO% | − 0.117 | 0.776 | DLCO% | 0.300 | 0.683 | ||

| KCO% | − 0.367 | 0.336 | KCO% | 0.600 | 0.350 | ||

| RV% | 0.453 | 0.882 | RV% | 0.369 | 0.332 | ||

| TLC% | 0.190 | 0.772 | TLC% | 0.309 | 0.730 | ||

| Gal-3 | FVC% | − 0.117 | 0.776 | Gal-3 | FVC% | 0.323 | 0.434 |

| FVC (ml) | − 0.083 | 0.843 | FVC(ml) | 0.262 | 0.536 | ||

| FEV1% | − 0.450 | 0.230 | FEV1% | 0.571 | 0.151 | ||

| FEV1(ml) | − 0.333 | 0.385 | FEV1(ml) | 0.619 | 0.115 | ||

| DLCO% | − 0.800 | 0.014 | DLCO% | 0.300 | 0.683 | ||

| KCO% | − 0.683 | 0.050 | KCO% | 0.100 | 0.950 | ||

| RV% | 0.112 | 0.213 | RV% | 0.192 | 0.782 | ||

| TLC% | 0.310 | 0.221 | TLC% | 0.886 | 0.033 | ||

| Gal-9 | FVC% | 0.133 | 0.744 | Gal-9 | FVC% | − 0.623 | 0.105 |

| FVC (ml) | 0.033 | 0.948 | FVC(ml) | − 0.714 | 0.058 | ||

| FEV1% | − 0.183 | 0.644 | FEV1% | − 0.643 | 0.096 | ||

| FEV1(ml) | − 0.167 | 0.678 | FEV1(ml) | − 0.595 | 0.132 | ||

| DLCO% | − 0.567 | 0.121 | DLCO% | − 0.100 | 0.950 | ||

| KCO% | − 0.800 | 0.014 | KCO% | − 0.200 | 0.783 | ||

| RV% | 0.683 | 0.05 | RV% | 0.143 | 0.867 | ||

| TLC% | 0.700 | 0.043 | TLC% | 0.324 | 0.584 | ||

Discussion

BOS is the most frequent presenting phenotype of CLAD. It is characterized by bronchiole thickening and obstruction due to injury and inflammation of epithelial cells and small airway subepithelial structures, leading to fibroproliferation and aberrant tissue repair [22]. Since pathogenesis is very complex, there are currently no biomarkers for early diagnosis of BOS or with clear clinical prognostic significance. The present exploratory study evaluated serum concentrations of galectins-1, 3 and 9 for the first time in LTX recipients, with and without BOS, and in healthy controls to assess their potential role as clinical biomarkers.

Gal-1 has been demonstrated to play a negative prognostic role in several conditions, including cancer and fibrotic processes [23, 24]. In transplantation, Gal-1 has shown to participate to hepatic graft tolerance and has been postulated it can be implicated in the inhibition of dendritic cells-mediated allogeneic T cell stimulation and survival and Th1/Th17 production [19, 25, 26]. It is also implicated in the dysregulation of the ERK/MAPK pathway [12] and plays its major function of immunomodulation determining the reduction of INF-gamma and inducing IL5 and IL10 production under inflammatory conditions [17] thus participating to neutrophil homeostasis [27]. While in a rat model of acute kidney rejection Gal-1 showed a potential protective role [28], more recently it was found increased in the glomeruli of kidney transplant patients with antibody-mediated rejection and proposed as potential therapeutic target to prevent extracellular matrix remodelling in such condition [29]. In the present study, higher serum concentrations of Gal-1 were observed in CLAD patients with BOS than in CLAD-free patients and healthy controls, which could be related to the inflammatory status of patients in the chronic rejection group. BAL neutrophilia is a common finding in BOS patients that can predict response to azithromycin therapy [30, 31]. Galectin-1 can positively or negatively modulate the effector functions of neutrophils according to cell activation stage [32] and its increased concentration might reflect the activation of neutrophils in BOS. Some earlier studies reported anti-inflammatory action of Gal-1, initially by modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine release and PMN migration through an imbalance of adhesion molecule expression, and later by promoting monocyte-macrophage recruitment [33]. Galectin-1 can also activate neutrophils through CD43, depending on the environment in which it acts [34]. Our results highlight the potential of Gal-1 as a clinical biomarker of BOS and suggest that it plays an as yet undefined part in the pathogenic mechanisms of BOS.

In the present study, higher serum concentrations of Gal-3 were observed in CLAD patients with BOS than in healthy controls, although its levels in BOS patients did not differ significantly with respect to those of CLAD-free patients. Galectin-3 concentrations were correlated with DLCO% and KCO% in CLAD-free patients. Elevated Gal-3 concentrations are known to be correlated with various inflammatory and fibrotic conditions, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune diseases, cancer and osteoarthritis, but no data is yet available on lung transplant patients [35, 36]. Galectin-3 seems to play a role in renal Ischemic-reperfusion injury involving the secretion of macrophage-related chemokine, pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS production [37].

Our limited number of patients does not allow us a safe interpretation of this result; however, the possible association with some pre-CLAD lung pathological process within the graft is interesting and need further exploration.

Galectin-9 was first identified as a chemoattractant and activation factor of eosinophils in vitro and in vivo [38]. It modulates different biological functions including cell aggregation and adhesion, as well as apoptosis of tumour cells. Few papers reported the prognostic role of Gal-9 in different organ transplantations in which Gal-9 expression after allo-hematopoietic stem cell and liver transplantation is a potential prognostic biomarker of acute rejection [39–41]. Moreover, some studies reported the association of Galectin-9 and the balance between infection/rejection in kidney transplantation [42] and it has been postulated its immunoregulatory role during the ongoing cytotoxic response [43]. In the present study, we recorded higher serum concentrations of Gal-9 in LTX patients than in healthy controls. Our findings can be traced back to fibroproliferation and aberrant tissue repair after injury and inflammation of small airway subepithelial structures in BOS patients. We also found inverse correlations between Gal-9 and KCO% in CLAD-free patients and between Gal-9 and measured FVC in CLAD-BOS, suggesting that this protein could be a negative prognostic marker in LTX recipients.

The limits of the present study were its monocentric and retrospective nature and small statistical sample. However, as an exploratory study into the role of galectins in lung transplant patients, it could pave the way for new research into their clinical and pathogenic participation in BOS. No specific hypothesis on their mechanistic role in lung transplantation can be made at this point; however, our study shines a first spotlight on galectins in chronic lung allograft dysfunction suggesting their potentiality as marker for homeostatic mechanisms of the graft that worth to investigate.

In conclusion, this is the first study to evaluate galectins concentrations in serum of LTX recipients. Our results reveal overexpression of these molecules in CLAD patients with BOS phenotype correlated with several respiratory function parameters. Galectins-1, 3 and 9 are possible clinical diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, worthy of further study in larger populations in order to clarify their role in lung transplant. These molecules may be directly implicated in the pathological mechanisms of BOS. The hypothesis that they could be new therapeutic targets in BOS patients is intriguing and also worth exploring.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the support of the “ASSOCIAZIONE PROFONDI RESPIRI ONLUS”.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Siena within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The present study was founded by Organizzazione Toscana Trapianti (OTT) (Grant 2019 – DGRT 641).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The research was approved by the local ethics committee (Respir1, Prot n 15732, 16 September 2019).

Consent to Participate

All subjects gave their written informed consent to the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bennett D, Lanzarone N, Fossi A, Perillo F, De Vita E, Luzzi L, Paladini P, Bargagli E, Sestini P, Rottoli P. Pirfenidone in chronic lung allograft dysfunction: a single cohort study. Panminerva Med. 2020;62(3):143–149. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.19.03840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett D, De Vita E, Fossi A, Bargagli E, Paladini P, Luzzi L, Franchi F, Scolletta S, Sestini P. Outcome of ECMO bridge to lung transplantation: a single cohort study. Minerva Med. 2020 doi: 10.23736/S0026-4806.20.06744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameli P, Bargagli E, Fossi A, Bennett D, Voltolini L, Refini RM, Gotti G, Rottoli P. Exhaled nitric oxide and carbon monoxide in lung transplanted patients. Respir Med. 2015;109(9):1224–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett D, Fossi A, Bargagli E, Refini RM, Pieroni M, Luzzi L, Ghiribelli C, Paladini P, Voltolini L, Rottoli P. Mortality on the waiting list for lung transplantation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a single-centre experience. Lung. 2015;193(5):677–681. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9767-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergantini L, d’Alessandro M, De Vita E, Perillo F, Fossi A, Luzzi L, Paladini P, Perrone A, Rottoli P, Sestini P, Bargagli E, Bennett D. Regulatory and effector cell disequilibrium in patients with acute cellular rejection and chronic lung allograft dysfunction after lung transplantation: comparison of peripheral and alveolar distribution. Cells. 2021;10(4):780. doi: 10.3390/cells10040780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verleden GM, Glanville AR, Lease ED, Fisher AJ, Calabrese F, Corris PA, Ensor CR, Gottlieb J, Hachem RR, Lama V, Martinu T, Neil DAH, Singer LG, Snell G, Vos R. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: definition, diagnostic criteria, and approaches to treatment-a consensus report from the Pulmonary Council of the ISHLT. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(5):493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ofek E, Sato M, Saito T, Wagnetz U, Roberts HC, Chaparro C, Waddell TK, Singer LG, Hutcheon MA, Keshavjee S, Hwang DM. Restrictive allograft syndrome post lung transplantation is characterized by pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(3):350–356. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu FT, Patterson RJ, Wang JL. Intracellular functions of galectins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572(2–3):263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinovich GA, Liu FT, Hirashima M, Anderson A. An emerging role for galectins in tuning the immune response: lessons from experimental models of inflammatory disease, autoimmunity and cancer. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66(2–3):143–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundblad V, Morosi LG, Geffner JR, Rabinovich GA. Galectin-1: a jack-of-all-trades in the resolution of acute and chronic inflammation. J Immunol. 2017;199(11):3721–3730. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.d'Alessandro M, De Vita E, Bergantini L, Mazzei MA, di Valvasone S, Bonizzoli M, Peris A, Sestini P, Bargagli E, Bennett D. Galactin-1, 3 and 9: potential biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and other interstitial lung diseases. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2020;282:103546. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2020.103546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathiriya JJ, Nakra N, Nixon J, Patel PS, Vaghasiya V, Alhassani A, Tian Z, Allen-Gipson D, Davé V. Galectin-1 inhibition attenuates profibrotic signaling in hypoxia-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Death Discov. 2017;3:17010. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishi Y, Sano H, Kawashima T, Okada T, Kuroda T, Kikkawa K, Kawashima S, Tanabe M, Goto T, Matsuzawa Y, Matsumura R, Tomioka H, Liu FT, Shirai K. Role of galectin-3 in human pulmonary fibrosis. Allergol Int. 2007;56(1):57–65. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-06-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumoto N, Katoh S, Yanagi S, Arimura Y, Tokojima M, Ueno M, Hirashima M, Nakazato M. A possible role of galectin-9 in the pulmonary fibrosis of patients with interstitial pneumonia. Lung. 2013;191(2):191–198. doi: 10.1007/s00408-012-9446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thijssen VL, Heusschen R, Caers J, Griffioen AW. Galectin expression in cancer diagnosis and prognosis: a systematic review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1855(2):235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett D, Bargagli E, Bianchi N, Landi C, Fossi A, Fui A, Sestini P, Refini RM, Rottoli P. Elevated level of Galectin-1 in bronchoalveolar lavage of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2020;273:103323. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2019.103323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei T, Moos S, Klug J, Aslani F, Bhushan S, Wahle E, Fröhlich S, Meinhardt A, Fijak M. Galectin-1 enhances TNFα-induced inflammatory responses in Sertoli cells through activation of MAPK signalling. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3741. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22135-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan R, Liu X, Wang J, Lu P, Han Z, Tao J, Yin C, Gu M. Alternations of galectin levels after renal transplantation. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(15):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García MJ, Jurado F, San Segundo D, López-Hoyos M, Iruzubieta P, Llerena S, Casafont F, Arias M, Puente Á, Crespo J, Fábrega E. Galectin-1 in stable liver transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(1):93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Culver BH, Graham BL, Coates AL, Wanger J, Berry CE, Clarke PK, Hallstrand TS, Hankinson JL, Kaminsky DA, MacIntyre NR, McCormack MC, Rosenfeld M, Stanojevic S, Weiner DJ. ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Pulmonary Function Laboratories. Recommendations for a standardized pulmonary function report: an official American Thoracic Society Technical Statement. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2017;196(11):1463–1472. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-1981ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Human Galectin-1 ELISA Kit (ab260053) | Abcam 2020. https://www.abcam.com/human-galectin-1-elisa-kit-ab260053.html

- 22.DerHovanessian A, Wallace WD, Lynch JP, 3rd, Belperio JA, Weigt SS. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: evolving concepts and therapies. SeminRespirCrit Care Med. 2018;39(2):155–171. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1618567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mundt F, Johansson HJ, Forshed J, Arslan S, Metintas M, Dobra K, Lehtiö J, Hjerpe A. Proteome screening of pleural effusions identifies galectin 1 as a diagnostic biomarker and highlights several prognostic biomarkers for malignant mesothelioma. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(3):701–715. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.030775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Li D, Wang X, Zhang B, Zhu H, Zhao J. Galectin-1 is overexpressed in CD133+ human lung adenocarcinoma cells and promotes their growth and invasiveness. Oncotarget. 2015;6(5):3111–3122. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang ZJ, Shen QH, Chen HY, Yang Z, Shuai MQ, Zheng S. Galectin-1 restores immune tolerance to liver transplantation through activation of hepatic stellate cells. Cell PhysiolBiochem. 2018;48(3):863–879. doi: 10.1159/000491955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Galectin-1, immune regulation and liver allograft survival. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(3):535–536. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundqvist M, Welin A, Elmwall J, Osla V, Nilsson UJ, Leffler H, Bylund J, Karlsson A. Galectin-3 type-C self-association on neutrophil surfaces; the carbohydrate recognition domain regulates cell function. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;103(2):341–353. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3A0317-110R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu G, Tu W, Xu C. Immunological tolerance induced by galectin-1 in rat allogeneic renal transplantation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10(6):643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clotet-Freixas S, McEvoy CM, Batruch I, Pastrello C, Kotlyar M, Van JAD, Arambewela M, Boshart A, Farkona S, Niu Y, Li Y, Famure O, Bozovic A, Kulasingam V, Chen P, Kim SJ, Chan E, Moshkelgosha S, Rahman SA, Das J, Martinu T, Juvet S, Jurisica I, Chruscinski A, John R, Konvalinka A. Extracellular matrix injury of kidney allografts in antibody-mediated rejection: a proteomics study. J Am SocNephrol. 2020;31(11):2705–2724. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berastegui C, Gómez-Ollés S, Sánchez-Vidaurre S, Culebras M, Monforte V, López-Meseguer M, Bravo C, Ramon MA, Romero L, Sole J, Cruz MJ, Román A. BALF cytokines in different phenotypes of chronic lung allograft dysfunction in lung transplant patients. Clin Transplant. 2017 doi: 10.1111/ctr.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gan CT, Ward C, Meachery G, Lordan JL, Fisher AJ, Corris PA. Long-term effect of azithromycin in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2019;6(1):e000465. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigues LC, Kabeya LM, Azzolini AECS, Cerri DG, Stowell SR, Cummings RD, Lucisano-Valim YM, Dias-Baruffi M. Galectin-1 modulation of neutrophil reactive oxygen species production depends on the cell activation state. Mol Immunol. 2019;116:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.10.001.Erratum.In:MolImmunol.2020Mar;119:59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gil CD, Gullo CE, Oliani SM. Effect of exogenous galectin-1 on leukocyte migration: modulation of cytokine levels and adhesion molecules. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;4(1):74–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auvynet C, Moreno S, Melchy E, Coronado-Martínez I, Montiel JL, Aguilar-Delfin I, Rosenstein Y. Galectin-1 promotes human neutrophil migration. Glycobiology. 2013;23(1):32–42. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lala RI, Puschita M, Darabantiu D, Pilat L. Galectin-3 in heart failure pathology—"another brick in the wall"? Acta Cardiol. 2015;70(3):323–331. doi: 10.1080/ac.70.3.3080637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reboul P, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP. Galectin-3 in osteoarthritis: when the fountain of youth doesn't deliver its promises. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(5):595–598. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000129663.76107.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.FernandesBertocchi AP, Campanhole G, Wang PH, Gonçalves GM, Damião MJ, Cenedeze MA, Beraldo FC, de Paula Antunes Teixeira V, Dos Reis MA, Mazzali M, Pacheco-Silva A, Câmara NO. A role for galectin-3 in renal tissue damage triggered by ischemia and reperfusion injury. Transplant Int. 2008;21(10):999–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katoh S, Nobumoto A, Matsumoto N, Matsumoto K, Ehara N, Niki T, Inada H, Nishi N, Yamauchi A, Fukushima K, Hirashima M. Involvement of galectin-9 in lung eosinophilia in patients with eosinophilic pneumonia. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153(3):294–302. doi: 10.1159/000314371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin J, Li L, Wang C, Zhang Y. Increased Galectin-9 expression, a prognostic biomarker of aGVHD, regulates the immune response through the Galectin-9 induced MDSC pathway after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106929. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang AB, Peng YF, Jia JJ, Nie Y, Zhang SY, Xie HY, Zhou L, Zheng SS. Exosome-derived galectin-9 may be a novel predictor of rejection and prognosis after liver transplantation. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2019;20(7):605–612. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1900051.Erratum.In:JZhejiangUnivSciB.2020Feb.;21(2):178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Q, Munger ME, Veenstra RG, Weigel BJ, Hirashima M, Munn DH, Murphy WJ, Azuma M, Anderson AC, Kuchroo VK, Blazar BR. Coexpression of Tim-3 and PD-1 identifies a CD8+ T-cell exhaustion phenotype in mice with disseminated acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(17):4501–4510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-310425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li YM, Li Y, Yan L, Tang JT, Wu XJ, Bai YJ, An YF, Dai B, Yang CL, Wang LL, Shi YY. Assessment of serum Tim-3 and Gal-9 levels in predicting the risk of infection after kidney transplantation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;75:105803. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naka EL, Ponciano VC, Cenedeze MA, Pacheco-Silva A, Câmara NO. Detection of the Tim-3 ligand, galectin-9, inside the allograft during a rejection episode. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(6):658–662. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]